User login

Preeclampsia complicates 3% to 8% of pregnancies.1-3 The incidence of preeclampsia is influenced by the clinical characteristics of the pregnant population, including the prevalence of overweight, obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, nulliparity, advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, kidney disease, and a history of preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy.4

Magnesium treatment reduces the rate of eclampsia among patients with preeclampsia

For patients with preeclampsia, magnesium treatment reduces the risk of seizure. In the Magpie trial, 9,992 pregnant patients were treated for 24 hours with magnesium or placebo.5 The magnesium treatment regimen was either a 4-g IV bolus over 10 to 15 minutes followed by a continuous infusion of 1 g/hr or an intramuscular regimen (10-g intramuscular loading dose followed by 5 g IM every 4 hours). Eclamptic seizures occurred in 0.8% and 1.9% of patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively (relative risk [RR], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29 to 0.60). Among patients with a multiple gestation, the rate of eclampsia was 2% and 6% in the patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively. The number of patients who needed to be treated to prevent one eclamptic event was 63 and 109 for patients with preeclampsia with and without severe features, respectively. Intrapartum treatment with magnesium also reduced the risk of placental abruption from 3.2% for the patients receiving placebo to 2.0% among the patients treated with magnesium (RR, 0.67; 99% CI, 0.45- 0.89). Maternal death was reduced with magnesium treatment compared with placebo (0.2% vs 0.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

In the Magpie trial, side effects were reported by 24% and 5% of patients treated with magnesium and placebo, respectively. The most common side effects were flushing, nausea, vomiting, and muscle weakness. Of note, magnesium treatment is contraindicated in patients with myasthenia gravis because it can cause muscle weakness and hypoventilation.6 For patients with preeclampsia and myasthenia gravis, levetiracetam may be utilized to reduce the risk of seizure.6

Duration of postpartum magnesium treatment

There are no studies with a sufficient number of participants to definitively determine the optimal duration of postpartum magnesium therapy. A properly powered study would likely require more than 16,000 to 20,000 participants to identify clinically meaningful differences in the rate of postpartum eclampsia among patients treated with magnesium for 12 or 24 hours.7,8 It is unlikely that such a study will be completed. Hence, the duration of postpartum magnesium must be based on clinical judgment, balancing the risks and benefits of treatment.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends continuing magnesium treatment for 24 hours postpartum. They advise, “For patients requiring cesarean delivery (before the onset of labor), the infusion should ideally begin before surgery and continue during surgery, as well as 24 hours afterwards. For patients who deliver vaginally, the infusion should continue for 24 hours after delivery.”9

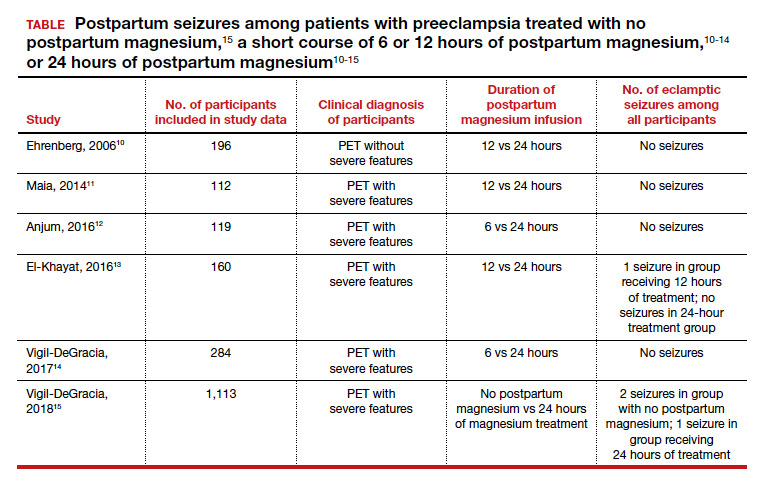

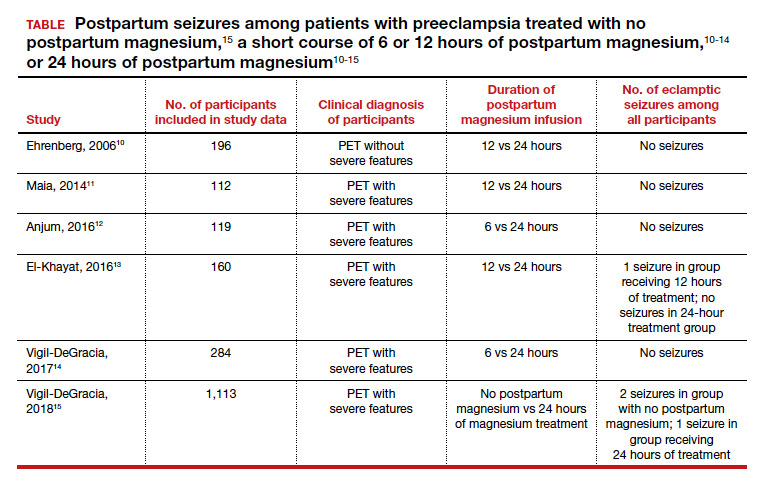

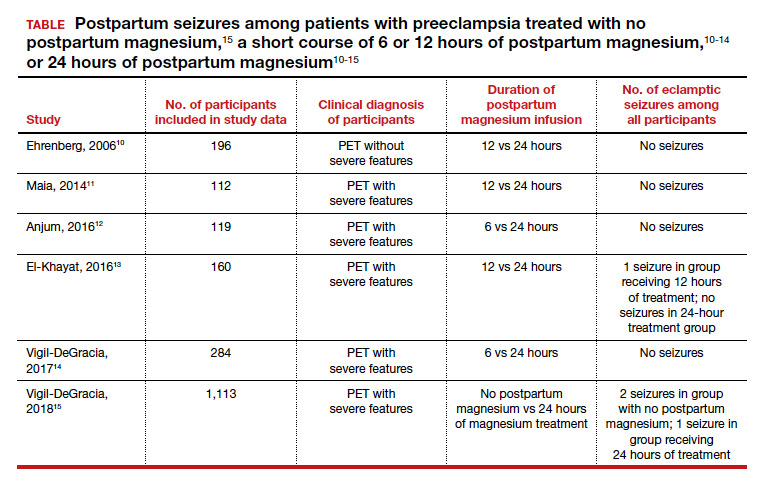

Multiple randomized trials have reported on the outcomes associated with 12 hours versus 24 hours of postpartum magnesium therapy (TABLE). Because the rate of postpartum eclamptic seizure is very low, none of the studies were sufficiently powered to provide a definitive answer to the benefits and harms of the shorter versus longer time frame of magnesium therapy.10-15

Continue to: The harms of prolonged postpartum magnesium infusion...

The harms of prolonged postpartum magnesium infusion

The harms of prolonging treatment with postpartum magnesium infusion are generally not emphasized in the medical literature. However, side effects that can occur are flushing, nausea, vomiting, and muscle weakness, delayed early ambulation, delayed return to full diet, delayed discontinuation of a bladder catheter, and delayed initiation of breastfeeding.5,15 In one large clinical trial, 1,113 patients with preeclampsia with severe features who received intrapartum magnesium for ≥8 hours were randomized after birth to immediate discontinuation of magnesium or continuation of magnesium for 24 hours.15 There was 1 seizure in the group of 555 patients who received 24 hours of postpartum magnesium and 2 seizures in the group of 558 patients who received no magnesium after birth. In this trial, continuation of magnesium postpartum resulted in delayed initiation of breastfeeding and delayed ambulation.15

Balancing the benefits and harms of postpartum magnesium infusion

An important clinical point is that magnesium treatment will not prevent all seizures associated with preeclampsia; in the Magpie trial, among the 5,055 patients with preeclampsia treated with magnesium there were 40 (0.8%) seizures.5 Magnesium treatment will reduce but not eliminate the risk of seizure. Clinicians should have a plan to treat seizures that occur while a woman is being treated with magnesium.

In the absence of high-quality data to guide the duration of postpartum magnesium therapy it is best to use clinical parameters to balance the benefits and harms of postpartum magnesium treatment.16-18 Patients may want to participate in the decision about the duration of postpartum magnesium treatment after receiving counseling about the benefits and harms.

For patients with preeclampsia without severe features, many clinicians are no longer ordering intrapartum magnesium for prevention of seizures because they believe the risk of seizure in patients without severe disease is very low. Hence, these patients will not receive postpartum magnesium treatment unless they evolve to preeclampsia with severe features or develop a “red flag” warning postpartum (see below).

For patients with preeclampsia without severe features who received intrapartum magnesium, after birth, the magnesium infusion could be stopped immediately or within 12 hours of birth. For patients with preeclampsia without severe features, early termination of the magnesium infusion best balances the benefit of seizure reduction with the harms of delayed early ambulation, return to full diet, discontinuation of the bladder catheter, and initiation of breastfeeding.

For patients with preeclampsia with severe features, 24 hours of magnesium may best balance the benefits and harms of treatment. However, if the patient continues to have “red flag” findings, continued magnesium treatment beyond 24 hours may be warranted.

Red flag findings include: an eclamptic seizure before or after birth, ongoing or recurring severe headaches, visual scotomata, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, severe hypertension, oliguria, rising creatinine, or liver transaminases and declining platelet count.

The hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, including preeclampsia often appear suddenly and may evolve rapidly, threatening the health of both mother and fetus. A high level of suspicion that a hypertensive disease might be the cause of vague symptoms such as epigastric discomfort or headache may accelerate early diagnosis. Rapid treatment of severe hypertension with intravenous labetalol and hydralazine, and intrapartum plus postpartum administration of magnesium to prevent placental abruption and eclampsia will optimize patient outcomes. No patient, patient’s family members, or clinician, wants to experience the grief of a preventable maternal, fetal, or newborn death due to hypertension.19 Obstetricians, midwives, labor nurses, obstetrical anesthesiologists and doulas play key roles in preventing maternal, fetal, and newborn morbidity and death from hypertensive diseases of pregnancy. As a team we are the last line of defense protecting the health of our patients. ●

- World Health Organization. WHO International Collaborative Study of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Geographic variation in the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:80-83.

- Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Incidence of preeclampsia: risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:544.e1-e12. doi: 10.1016 /j.ajog.2013.08.019.

- Mayrink K, Souza RT, Feitosa FE, et al. Incidence and risk factors for preeclampsia in a cohort of healthy nulliparous patients: a nested casecontrol study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9517. doi: 10.1038 /s41598-019-46011-3.

- Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL, et al. High risk of pre-eclampsia identification group. BMJ. 2016;353:i1753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1753.

- Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L; The Magpie Trial Collaborative Group. Do patients with preeclampsia, and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulfate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877- 1890. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08778-0.

- Lake AJ, Al Hkabbaz A, Keeney R. Severe preeclampsia in the setting of myasthenia gravis. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;9204930. doi: 10.1155/2017/9204930.

- Hurd WW, Ventolini G, Stolfi A. Postpartum seizure prophylaxis: using maternal clinical parameters to guide therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102: 196-197. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00471-x.

- Scott JR. Safety of eliminating postpartum magnesium sulphate: intriguing but not yet proven. BJOG. 2018;125:1312. doi: 10.1111/1471 -0528.15317.

- Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 222. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e237-e260. doi: 10.1097/AOG .0000000000003891.

- Ehrenberg H, Mercer BM. Abbreviated postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy for patients with mild preeclampsia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:833-888. doi: 10.1097 /01.AOG.0000236493.35347.d8.

- Maia SB, Katz L, Neto CN, et al. Abbreviated (12- hour) versus traditional (24-hour) postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy in severe pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126:260-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.03.024.

- Anjum S, Rajaram GP, Bano I. Short-course (6-h) magnesium sulfate therapy in severe preeclampsia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:983-986. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3903-y.

- El-Khayat W, Atef A, Abdelatty S, et al. A novel protocol for postpartum magnesium sulphate in severe pre-eclampsia: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29: 154-158. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.991915.

- Vigil-De Gracia P, Ramirez R, Duran Y, et al. Magnesium sulfate for 6 vs 24 hours post-delivery in patients who received magnesium sulfate for less than 8 hours before birth: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:241. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1424-3.

- Vigil-DeGracia P, Ludmir J, Ng J, et al. Is there benefit to continue magnesium sulphate postpartum in patients receiving magnesium sulphate before delivery? A randomized controlled study. BJOG. 2018;125:1304-1311. doi: 10.1111/1471 -0528.15320.

- Ascarelli MH, Johnson V, May WL, et al. Individually determined postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy with clinical parameters to safety and cost-effectively shorten treatment for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:952-956. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70195-4.

- Isler CM, Barrilleaux PS, Rinehart BK, et al. Postpartum seizure prophylaxis: using maternal clinical parameters to guide therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:66-69. doi: 10.1016/s0029 -7844(02)02317-7.

- Fontenot MT, Lewis DF, Frederick JB, et al. A prospective randomized trial of magnesium sulfate in severe preeclampsia: use of diuresis as a clinical parameter to determine the duration of postpartum therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1788- 1793. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.056.

- Tsigas EZ. The Preeclampsia Foundation: the voice and views of the patient and family. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Epub August 23, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.053.

Preeclampsia complicates 3% to 8% of pregnancies.1-3 The incidence of preeclampsia is influenced by the clinical characteristics of the pregnant population, including the prevalence of overweight, obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, nulliparity, advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, kidney disease, and a history of preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy.4

Magnesium treatment reduces the rate of eclampsia among patients with preeclampsia

For patients with preeclampsia, magnesium treatment reduces the risk of seizure. In the Magpie trial, 9,992 pregnant patients were treated for 24 hours with magnesium or placebo.5 The magnesium treatment regimen was either a 4-g IV bolus over 10 to 15 minutes followed by a continuous infusion of 1 g/hr or an intramuscular regimen (10-g intramuscular loading dose followed by 5 g IM every 4 hours). Eclamptic seizures occurred in 0.8% and 1.9% of patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively (relative risk [RR], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29 to 0.60). Among patients with a multiple gestation, the rate of eclampsia was 2% and 6% in the patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively. The number of patients who needed to be treated to prevent one eclamptic event was 63 and 109 for patients with preeclampsia with and without severe features, respectively. Intrapartum treatment with magnesium also reduced the risk of placental abruption from 3.2% for the patients receiving placebo to 2.0% among the patients treated with magnesium (RR, 0.67; 99% CI, 0.45- 0.89). Maternal death was reduced with magnesium treatment compared with placebo (0.2% vs 0.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

In the Magpie trial, side effects were reported by 24% and 5% of patients treated with magnesium and placebo, respectively. The most common side effects were flushing, nausea, vomiting, and muscle weakness. Of note, magnesium treatment is contraindicated in patients with myasthenia gravis because it can cause muscle weakness and hypoventilation.6 For patients with preeclampsia and myasthenia gravis, levetiracetam may be utilized to reduce the risk of seizure.6

Duration of postpartum magnesium treatment

There are no studies with a sufficient number of participants to definitively determine the optimal duration of postpartum magnesium therapy. A properly powered study would likely require more than 16,000 to 20,000 participants to identify clinically meaningful differences in the rate of postpartum eclampsia among patients treated with magnesium for 12 or 24 hours.7,8 It is unlikely that such a study will be completed. Hence, the duration of postpartum magnesium must be based on clinical judgment, balancing the risks and benefits of treatment.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends continuing magnesium treatment for 24 hours postpartum. They advise, “For patients requiring cesarean delivery (before the onset of labor), the infusion should ideally begin before surgery and continue during surgery, as well as 24 hours afterwards. For patients who deliver vaginally, the infusion should continue for 24 hours after delivery.”9

Multiple randomized trials have reported on the outcomes associated with 12 hours versus 24 hours of postpartum magnesium therapy (TABLE). Because the rate of postpartum eclamptic seizure is very low, none of the studies were sufficiently powered to provide a definitive answer to the benefits and harms of the shorter versus longer time frame of magnesium therapy.10-15

Continue to: The harms of prolonged postpartum magnesium infusion...

The harms of prolonged postpartum magnesium infusion

The harms of prolonging treatment with postpartum magnesium infusion are generally not emphasized in the medical literature. However, side effects that can occur are flushing, nausea, vomiting, and muscle weakness, delayed early ambulation, delayed return to full diet, delayed discontinuation of a bladder catheter, and delayed initiation of breastfeeding.5,15 In one large clinical trial, 1,113 patients with preeclampsia with severe features who received intrapartum magnesium for ≥8 hours were randomized after birth to immediate discontinuation of magnesium or continuation of magnesium for 24 hours.15 There was 1 seizure in the group of 555 patients who received 24 hours of postpartum magnesium and 2 seizures in the group of 558 patients who received no magnesium after birth. In this trial, continuation of magnesium postpartum resulted in delayed initiation of breastfeeding and delayed ambulation.15

Balancing the benefits and harms of postpartum magnesium infusion

An important clinical point is that magnesium treatment will not prevent all seizures associated with preeclampsia; in the Magpie trial, among the 5,055 patients with preeclampsia treated with magnesium there were 40 (0.8%) seizures.5 Magnesium treatment will reduce but not eliminate the risk of seizure. Clinicians should have a plan to treat seizures that occur while a woman is being treated with magnesium.

In the absence of high-quality data to guide the duration of postpartum magnesium therapy it is best to use clinical parameters to balance the benefits and harms of postpartum magnesium treatment.16-18 Patients may want to participate in the decision about the duration of postpartum magnesium treatment after receiving counseling about the benefits and harms.

For patients with preeclampsia without severe features, many clinicians are no longer ordering intrapartum magnesium for prevention of seizures because they believe the risk of seizure in patients without severe disease is very low. Hence, these patients will not receive postpartum magnesium treatment unless they evolve to preeclampsia with severe features or develop a “red flag” warning postpartum (see below).

For patients with preeclampsia without severe features who received intrapartum magnesium, after birth, the magnesium infusion could be stopped immediately or within 12 hours of birth. For patients with preeclampsia without severe features, early termination of the magnesium infusion best balances the benefit of seizure reduction with the harms of delayed early ambulation, return to full diet, discontinuation of the bladder catheter, and initiation of breastfeeding.

For patients with preeclampsia with severe features, 24 hours of magnesium may best balance the benefits and harms of treatment. However, if the patient continues to have “red flag” findings, continued magnesium treatment beyond 24 hours may be warranted.

Red flag findings include: an eclamptic seizure before or after birth, ongoing or recurring severe headaches, visual scotomata, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, severe hypertension, oliguria, rising creatinine, or liver transaminases and declining platelet count.

The hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, including preeclampsia often appear suddenly and may evolve rapidly, threatening the health of both mother and fetus. A high level of suspicion that a hypertensive disease might be the cause of vague symptoms such as epigastric discomfort or headache may accelerate early diagnosis. Rapid treatment of severe hypertension with intravenous labetalol and hydralazine, and intrapartum plus postpartum administration of magnesium to prevent placental abruption and eclampsia will optimize patient outcomes. No patient, patient’s family members, or clinician, wants to experience the grief of a preventable maternal, fetal, or newborn death due to hypertension.19 Obstetricians, midwives, labor nurses, obstetrical anesthesiologists and doulas play key roles in preventing maternal, fetal, and newborn morbidity and death from hypertensive diseases of pregnancy. As a team we are the last line of defense protecting the health of our patients. ●

Preeclampsia complicates 3% to 8% of pregnancies.1-3 The incidence of preeclampsia is influenced by the clinical characteristics of the pregnant population, including the prevalence of overweight, obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, nulliparity, advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, kidney disease, and a history of preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy.4

Magnesium treatment reduces the rate of eclampsia among patients with preeclampsia

For patients with preeclampsia, magnesium treatment reduces the risk of seizure. In the Magpie trial, 9,992 pregnant patients were treated for 24 hours with magnesium or placebo.5 The magnesium treatment regimen was either a 4-g IV bolus over 10 to 15 minutes followed by a continuous infusion of 1 g/hr or an intramuscular regimen (10-g intramuscular loading dose followed by 5 g IM every 4 hours). Eclamptic seizures occurred in 0.8% and 1.9% of patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively (relative risk [RR], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29 to 0.60). Among patients with a multiple gestation, the rate of eclampsia was 2% and 6% in the patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively. The number of patients who needed to be treated to prevent one eclamptic event was 63 and 109 for patients with preeclampsia with and without severe features, respectively. Intrapartum treatment with magnesium also reduced the risk of placental abruption from 3.2% for the patients receiving placebo to 2.0% among the patients treated with magnesium (RR, 0.67; 99% CI, 0.45- 0.89). Maternal death was reduced with magnesium treatment compared with placebo (0.2% vs 0.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

In the Magpie trial, side effects were reported by 24% and 5% of patients treated with magnesium and placebo, respectively. The most common side effects were flushing, nausea, vomiting, and muscle weakness. Of note, magnesium treatment is contraindicated in patients with myasthenia gravis because it can cause muscle weakness and hypoventilation.6 For patients with preeclampsia and myasthenia gravis, levetiracetam may be utilized to reduce the risk of seizure.6

Duration of postpartum magnesium treatment

There are no studies with a sufficient number of participants to definitively determine the optimal duration of postpartum magnesium therapy. A properly powered study would likely require more than 16,000 to 20,000 participants to identify clinically meaningful differences in the rate of postpartum eclampsia among patients treated with magnesium for 12 or 24 hours.7,8 It is unlikely that such a study will be completed. Hence, the duration of postpartum magnesium must be based on clinical judgment, balancing the risks and benefits of treatment.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends continuing magnesium treatment for 24 hours postpartum. They advise, “For patients requiring cesarean delivery (before the onset of labor), the infusion should ideally begin before surgery and continue during surgery, as well as 24 hours afterwards. For patients who deliver vaginally, the infusion should continue for 24 hours after delivery.”9

Multiple randomized trials have reported on the outcomes associated with 12 hours versus 24 hours of postpartum magnesium therapy (TABLE). Because the rate of postpartum eclamptic seizure is very low, none of the studies were sufficiently powered to provide a definitive answer to the benefits and harms of the shorter versus longer time frame of magnesium therapy.10-15

Continue to: The harms of prolonged postpartum magnesium infusion...

The harms of prolonged postpartum magnesium infusion

The harms of prolonging treatment with postpartum magnesium infusion are generally not emphasized in the medical literature. However, side effects that can occur are flushing, nausea, vomiting, and muscle weakness, delayed early ambulation, delayed return to full diet, delayed discontinuation of a bladder catheter, and delayed initiation of breastfeeding.5,15 In one large clinical trial, 1,113 patients with preeclampsia with severe features who received intrapartum magnesium for ≥8 hours were randomized after birth to immediate discontinuation of magnesium or continuation of magnesium for 24 hours.15 There was 1 seizure in the group of 555 patients who received 24 hours of postpartum magnesium and 2 seizures in the group of 558 patients who received no magnesium after birth. In this trial, continuation of magnesium postpartum resulted in delayed initiation of breastfeeding and delayed ambulation.15

Balancing the benefits and harms of postpartum magnesium infusion

An important clinical point is that magnesium treatment will not prevent all seizures associated with preeclampsia; in the Magpie trial, among the 5,055 patients with preeclampsia treated with magnesium there were 40 (0.8%) seizures.5 Magnesium treatment will reduce but not eliminate the risk of seizure. Clinicians should have a plan to treat seizures that occur while a woman is being treated with magnesium.

In the absence of high-quality data to guide the duration of postpartum magnesium therapy it is best to use clinical parameters to balance the benefits and harms of postpartum magnesium treatment.16-18 Patients may want to participate in the decision about the duration of postpartum magnesium treatment after receiving counseling about the benefits and harms.

For patients with preeclampsia without severe features, many clinicians are no longer ordering intrapartum magnesium for prevention of seizures because they believe the risk of seizure in patients without severe disease is very low. Hence, these patients will not receive postpartum magnesium treatment unless they evolve to preeclampsia with severe features or develop a “red flag” warning postpartum (see below).

For patients with preeclampsia without severe features who received intrapartum magnesium, after birth, the magnesium infusion could be stopped immediately or within 12 hours of birth. For patients with preeclampsia without severe features, early termination of the magnesium infusion best balances the benefit of seizure reduction with the harms of delayed early ambulation, return to full diet, discontinuation of the bladder catheter, and initiation of breastfeeding.

For patients with preeclampsia with severe features, 24 hours of magnesium may best balance the benefits and harms of treatment. However, if the patient continues to have “red flag” findings, continued magnesium treatment beyond 24 hours may be warranted.

Red flag findings include: an eclamptic seizure before or after birth, ongoing or recurring severe headaches, visual scotomata, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, severe hypertension, oliguria, rising creatinine, or liver transaminases and declining platelet count.

The hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, including preeclampsia often appear suddenly and may evolve rapidly, threatening the health of both mother and fetus. A high level of suspicion that a hypertensive disease might be the cause of vague symptoms such as epigastric discomfort or headache may accelerate early diagnosis. Rapid treatment of severe hypertension with intravenous labetalol and hydralazine, and intrapartum plus postpartum administration of magnesium to prevent placental abruption and eclampsia will optimize patient outcomes. No patient, patient’s family members, or clinician, wants to experience the grief of a preventable maternal, fetal, or newborn death due to hypertension.19 Obstetricians, midwives, labor nurses, obstetrical anesthesiologists and doulas play key roles in preventing maternal, fetal, and newborn morbidity and death from hypertensive diseases of pregnancy. As a team we are the last line of defense protecting the health of our patients. ●

- World Health Organization. WHO International Collaborative Study of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Geographic variation in the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:80-83.

- Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Incidence of preeclampsia: risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:544.e1-e12. doi: 10.1016 /j.ajog.2013.08.019.

- Mayrink K, Souza RT, Feitosa FE, et al. Incidence and risk factors for preeclampsia in a cohort of healthy nulliparous patients: a nested casecontrol study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9517. doi: 10.1038 /s41598-019-46011-3.

- Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL, et al. High risk of pre-eclampsia identification group. BMJ. 2016;353:i1753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1753.

- Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L; The Magpie Trial Collaborative Group. Do patients with preeclampsia, and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulfate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877- 1890. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08778-0.

- Lake AJ, Al Hkabbaz A, Keeney R. Severe preeclampsia in the setting of myasthenia gravis. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;9204930. doi: 10.1155/2017/9204930.

- Hurd WW, Ventolini G, Stolfi A. Postpartum seizure prophylaxis: using maternal clinical parameters to guide therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102: 196-197. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00471-x.

- Scott JR. Safety of eliminating postpartum magnesium sulphate: intriguing but not yet proven. BJOG. 2018;125:1312. doi: 10.1111/1471 -0528.15317.

- Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 222. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e237-e260. doi: 10.1097/AOG .0000000000003891.

- Ehrenberg H, Mercer BM. Abbreviated postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy for patients with mild preeclampsia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:833-888. doi: 10.1097 /01.AOG.0000236493.35347.d8.

- Maia SB, Katz L, Neto CN, et al. Abbreviated (12- hour) versus traditional (24-hour) postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy in severe pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126:260-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.03.024.

- Anjum S, Rajaram GP, Bano I. Short-course (6-h) magnesium sulfate therapy in severe preeclampsia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:983-986. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3903-y.

- El-Khayat W, Atef A, Abdelatty S, et al. A novel protocol for postpartum magnesium sulphate in severe pre-eclampsia: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29: 154-158. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.991915.

- Vigil-De Gracia P, Ramirez R, Duran Y, et al. Magnesium sulfate for 6 vs 24 hours post-delivery in patients who received magnesium sulfate for less than 8 hours before birth: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:241. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1424-3.

- Vigil-DeGracia P, Ludmir J, Ng J, et al. Is there benefit to continue magnesium sulphate postpartum in patients receiving magnesium sulphate before delivery? A randomized controlled study. BJOG. 2018;125:1304-1311. doi: 10.1111/1471 -0528.15320.

- Ascarelli MH, Johnson V, May WL, et al. Individually determined postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy with clinical parameters to safety and cost-effectively shorten treatment for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:952-956. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70195-4.

- Isler CM, Barrilleaux PS, Rinehart BK, et al. Postpartum seizure prophylaxis: using maternal clinical parameters to guide therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:66-69. doi: 10.1016/s0029 -7844(02)02317-7.

- Fontenot MT, Lewis DF, Frederick JB, et al. A prospective randomized trial of magnesium sulfate in severe preeclampsia: use of diuresis as a clinical parameter to determine the duration of postpartum therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1788- 1793. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.056.

- Tsigas EZ. The Preeclampsia Foundation: the voice and views of the patient and family. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Epub August 23, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.053.

- World Health Organization. WHO International Collaborative Study of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Geographic variation in the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:80-83.

- Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Incidence of preeclampsia: risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:544.e1-e12. doi: 10.1016 /j.ajog.2013.08.019.

- Mayrink K, Souza RT, Feitosa FE, et al. Incidence and risk factors for preeclampsia in a cohort of healthy nulliparous patients: a nested casecontrol study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9517. doi: 10.1038 /s41598-019-46011-3.

- Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL, et al. High risk of pre-eclampsia identification group. BMJ. 2016;353:i1753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1753.

- Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L; The Magpie Trial Collaborative Group. Do patients with preeclampsia, and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulfate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877- 1890. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08778-0.

- Lake AJ, Al Hkabbaz A, Keeney R. Severe preeclampsia in the setting of myasthenia gravis. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;9204930. doi: 10.1155/2017/9204930.

- Hurd WW, Ventolini G, Stolfi A. Postpartum seizure prophylaxis: using maternal clinical parameters to guide therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102: 196-197. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00471-x.

- Scott JR. Safety of eliminating postpartum magnesium sulphate: intriguing but not yet proven. BJOG. 2018;125:1312. doi: 10.1111/1471 -0528.15317.

- Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 222. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e237-e260. doi: 10.1097/AOG .0000000000003891.

- Ehrenberg H, Mercer BM. Abbreviated postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy for patients with mild preeclampsia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:833-888. doi: 10.1097 /01.AOG.0000236493.35347.d8.

- Maia SB, Katz L, Neto CN, et al. Abbreviated (12- hour) versus traditional (24-hour) postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy in severe pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126:260-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.03.024.

- Anjum S, Rajaram GP, Bano I. Short-course (6-h) magnesium sulfate therapy in severe preeclampsia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:983-986. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3903-y.

- El-Khayat W, Atef A, Abdelatty S, et al. A novel protocol for postpartum magnesium sulphate in severe pre-eclampsia: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29: 154-158. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.991915.

- Vigil-De Gracia P, Ramirez R, Duran Y, et al. Magnesium sulfate for 6 vs 24 hours post-delivery in patients who received magnesium sulfate for less than 8 hours before birth: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:241. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1424-3.

- Vigil-DeGracia P, Ludmir J, Ng J, et al. Is there benefit to continue magnesium sulphate postpartum in patients receiving magnesium sulphate before delivery? A randomized controlled study. BJOG. 2018;125:1304-1311. doi: 10.1111/1471 -0528.15320.

- Ascarelli MH, Johnson V, May WL, et al. Individually determined postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy with clinical parameters to safety and cost-effectively shorten treatment for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:952-956. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70195-4.

- Isler CM, Barrilleaux PS, Rinehart BK, et al. Postpartum seizure prophylaxis: using maternal clinical parameters to guide therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:66-69. doi: 10.1016/s0029 -7844(02)02317-7.

- Fontenot MT, Lewis DF, Frederick JB, et al. A prospective randomized trial of magnesium sulfate in severe preeclampsia: use of diuresis as a clinical parameter to determine the duration of postpartum therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1788- 1793. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.056.

- Tsigas EZ. The Preeclampsia Foundation: the voice and views of the patient and family. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Epub August 23, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.053.