User login

CASE Failure to perform cesarean delivery1–4

A 19-year-old woman (G1P0) received prenatal care at a federally funded health center. Her pregnancy was normal without complications. She presented to the hospital after spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM). The on-call ObGyn employed by the clinic was offsite when the mother was admitted.

The mother signed a standard consent form for vaginal and cesarean deliveries and any other surgical procedure required during the course of giving birth.

The ObGyn ordered low-dose oxytocin to augment labor in light of her SROM. Oxytocin was started at 9:46

Upon delivery, the infant was flaccid and not breathing. His Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 6 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively, and the cord pH was 7. The neonatal intensive care (NICU) team provided aggressive resuscitation.

At the time of trial, the 18-month-old boy was being fed through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube and had a tracheostomy that required periodic suctioning. The child was not able to stand, crawl, or support himself, and will require 24-hour nursing care for the rest of his life.

LAWSUIT. The parents filed a lawsuit in federal court for damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act (see “Notes about this case,”). The mother claimed that she had requested a cesarean delivery early in labor when FHR tracings showed fetal distress, and again prior to vacuum extraction; the ObGyn refused both times.

The ObGyn claimed that when he noted a category III tracing, he recommended cesarean delivery, but the patient refused. He recorded the refusal in the chart some time later, after he had noted the neonate’s appearance.

The parents’ expert testified that restarting oxytocin and using vacuum extraction multiple times were dangerous and gross deviations from acceptable practice. Prolonged and repetitive use of the vacuum extractor caused a large subgaleal hematoma that decreased blood flow to the fetal brain, resulting in irreversible central nervous system (CNS) damage secondary to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed at the first sign of fetal distress.

The defense expert pointed out that the ObGyn discussed the need for cesarean delivery with the patient when fetal distress occurred and that the ObGyn was bedside and monitoring the fetus and the mother. Although the mother consented to a cesarean delivery at time of admission, she refused to allow the procedure.

The labor and delivery (L&D) nurse corroborated the mother’s story that a cesarean delivery was not offered by the ObGyn, and when the patient asked for a cesarean delivery, he refused. The nurse stated that the note added to the records by the ObGyn about the mother’s refusal was a lie. If the mother had refused a cesarean, the nurse would have documented the refusal by completing a Refusal of Treatment form that would have been faxed to the risk manager. No such form was required because nothing was ever offered that the mother refused.

The nurse also testified that during the course of the latter part of labor, the ObGyn left the room several times to assist other patients, deliver another baby, and make an 8-minute phone call to his stockbroker. She reported that the ObGyn was out of the room when delivery occurred.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

Read about the verdict and medical considerations.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The medical care and the federal-court bench trial held in front of a judge (not a jury) occurred in Florida. The verdict suggests that the ObGyn breached the standard of care by not offering or proceeding with a cesarean delivery and this management resulted in the child’s injuries. The court awarded damages in the amount of $33,813,495.91, including $29,413,495.91 for the infant; $3,300,000.00 for the plaintiff; and $1,100,000.00 for her spouse.4

Medical considerations

Refusal of medical care

Although it appears that in this case the patient did not actually refuse medical care (cesarean delivery), the case does raise the question of refusal. Refusal of medical care has been addressed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) predicated upon care that supports maternal and fetal wellbeing.5 There may be a fine balance between safeguarding the pregnant woman’s autonomy and optimization of fetal wellbeing. “Forced compliance,” on the other hand, is the alternative to respecting refusal of treatment. Ethical issues come into play: patient rights; respect for autonomy; violations of bodily integrity; power differentials; and gender equality.5 The use of coercion is “not only ethically impermissible but also medically inadvisable secondary to the realities of prognostic uncertainty and the limitations of medical knowledge.”5 There is an obligation to elicit the patient’s reasoning and lived experience. Perhaps most importantly, as clinicians working to achieve a resolution, consideration of the following is appropriate5:

- reliability and validity of evidence-based medicine

- severity of the prospective outcome

- degree of risk or burden placed on the patient

- patient understanding of the gravity of the situation and risks

- degree of urgency.

Much of this boils down to the obligation to discuss “risks and benefits of treatment, alternatives and consequences of refusing treatment.”6

Complications from vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery

Ghidini and associates, in a multicenter retrospective study, evaluated complications relating to vacuum-assisted delivery. They listed major primary outcomes of subgaleal hemorrhage, skull fracture, and intracranial bleeding, and minor primary outcomes of cephalohematoma, scalp laceration, and extensive skin abrasions. Secondary outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of <7, umbilical artery pH of <7.10, shoulder dystocia, and NICU admission.7

A retrospective study from Sweden assessing all vacuum deliveries over a 2-year period compared the use of the Kiwi OmniCup (Clinical Innovations) to use of the Malmström metal cup (Medela). No statistical differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes as well as failure rates were noted. However, the duration of the procedure was longer and the requirement for fundal pressure was higher with the Malmström device.8

Subgaleal hemorrhage. Ghidini and colleagues reported a heightened incidence of head injury related to the duration of vacuum application and birth weight.7 Specifically, vacuum delivery devices increase the risk of subgaleal hemorrhage. Blood can accumulate between the scalp’s epicranial aponeurosis and the periosteum and potentially can extend forward to the orbital margins, backward to the nuchal ridge, and laterally to the temporal fascia. As much as 260 mL of blood can get into this subaponeurotic space in term babies.9 Up to one-quarter of babies who require NICU admission for this condition die.10 This injury seldom occurs with forceps.

Shoulder dystocia. In a meta-analysisfrom Italy, the vacuum extractor was associated with increased risk of shoulder dystocia compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery.11

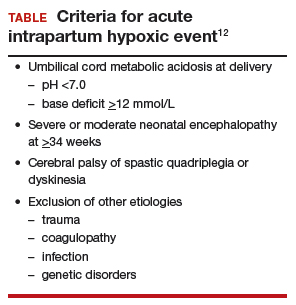

Intrapartum hypoxia. In 2003, the ACOG Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy defined an acute intrapartum hypoxic event (TABLE).12

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as “a chronic neuromuscular disability characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture appearing early in life and not the result of recognized progressive disease.”13,14

The Collaborative Perinatal Project concluded that birth trauma plays a minimal role in development of CP.15 Arrested labor, use of oxytocin, or prolonged labor did not play a role. CP can develop following significant cerebral or posterior fossa hemorrhage in term infants.16

Perinatal asphyxia is a poor and imprecise term and use of the expression should be abandoned. Overall, 90% of children with CP do not have birth asphyxia as the underlying etiology.14

Prognostic assessment can be made, in part, by using the Sarnat classification system (classification scale for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of the newborn) or an electroencephalogram to stratify the severity of neonatal encephalopathy.12 Such tests are not stand-alone but a segment of assessment. At this point “a better understanding of the processes leading to neonatal encephalopathy and associated outcomes” appear to be required to understand and associate outcomes.12 “More accurate and reliable tools (are required) for prognostic forecasting.”12

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy involves multisystem organ failure including renal, hepatic, hematologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and metabolic abnormalities. There is no correlation between the degree of CNS injury and level of other organ abnormalities.12

Differential diagnosis

When events such as those described in this case occur, develop a differential diagnosis by considering the following12:

- uterine rupture

- severe placental abruption

- umbilical cord prolapse

- amniotic fluid embolus

- maternal cardiovascular collapse

- fetal exsanguination.

Read about the legal considerations.

Legal considerations

Although ObGyns are among the specialties most likely to experience malpractice claims,17 a verdict of more than $33 million is unusual.18 Despite the failure of adequate care, and the enormous damages, the ObGyn involved probably will not be responsible for paying the verdict (see “Notes about this case”). The case presents a number of important lessons and reminders for anyone practicing obstetrics.

A procedural comment

The case in this article arose under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA).1 Most government entities have sovereign immunity, meaning that they can be sued only with their consent. In the FTCA, the federal government consented to being sued for the acts of its employees. This right has a number of limitations and some technical procedures, but at its core, it permits the United States to be sued as though it was a private individual.2 Private individuals can be sued for the acts of the agents (including employees).

Although the FTCA is a federal law, and these cases are tried in federal court, the substantive law of the state applies. This case occurred in Florida, so Florida tort law, defenses, and limitation on claims applied here also. Had the events occurred in Iowa, Iowa law would have applied.

In FTCA cases, the United States is the defendant (generally it is the government, not the employee who is the defendant).3 In this case, the ObGyn was employed by a federal government entity to provide delivery services. As a result, the United States was the primary defendant, had the obligation to defend the suit, and will almost certainly be obligated to pay the verdict.

The case facts

Although this description is based on an actual case, the facts were taken from the opinion of the trial court, legal summaries and press reports and not from the full case documents.4-7 We could not independently assess the accuracy of the facts, but for the purpose of this discussion, we have assumed the facts to be correct. The government has apparently filed an appeal in the Eleventh Circuit.

References

- Federal Tort Claims Act. Vol 28 U.S.C. Pt.VI Ch.171 and 28 U.S.C. § 1346(b).

- About the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). Health Resources & Services Administration: Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/ftca/about/index.html. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Dowell MA, Scott CD. Federally Qualified Health Center Federal Tort Claims Act Insurance Coverage. Health Law. 2015;5:31-43.

- Chang D. Miami doctor's call to broker during baby's delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17-18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

Very large verdict

The extraordinary size of this verdict ($33 million without any punitive damages) is a reminder that in obstetrics, mistakes can have catastrophic consequences and very high costs.19 This fact is reflected in malpractice insurance rates.

A substantial amount of this case’s award will provide around-the-clock care for the child. This verdict was not the result of a runaway jury—it was a judge’s decision. It is also noteworthy to report that a small percentage of physicians (1%) appear responsible for a significant number (about one-third) of paid claims.20

Although the size of the verdict is unusual, the case is a fairly straightforward negligence tort. The judge found that the ObGyn had breached the duty of care for his patient. The actions that fell below the standard of care included restarting the oxytocin, using the Kiwi vacuum device 3 times, and failing to perform a cesarean delivery in light of obvious fetal distress. That negligence caused injury to the infant (and his parents).21 The judge determined that the 4 elements of negligence were present: 1) duty of care, 2) breach of that duty, 3) injury, and 4) a causal link between the breach of duty and the injury. The failure to adhere to good practice standards practically defines breach of duty.22

Multitasking

One important lesson is that multitasking, absence, and inattention can look terrible when things go wrong. Known as “hindsight bias,” the awareness that there was a disastrous result makes it easier to attribute the outcome to small mistakes that otherwise might seem trivial. This ObGyn was in and out of the room during a difficult labor. Perhaps that was understandable if it were unavoidable because of another delivery, but being absent frequently and not present for the delivery now looks very significant.23 And, of course, the 8-minute phone call to the stockbroker shines as a heartless, self-centered act of inattention.

Manipulating the record

Another lesson of this case: Do not manipulate the record. The ObGyn recorded that the patient had refused the cesarean delivery he recommended. Had that been the truth, it would have substantially improved his case. But apparently it was not the truth. Although there was circumstantial evidence (the charting of the patient’s refusal only after the newborn’s condition was obvious, failure to complete appropriate hospital forms), the most damning evidence was the direct testimony of the L&D nurse. She reported that, contrary to what the ObGyn put in the chart, the patient requested a cesarean delivery. In truth, it was the ObGyn who had refused.

A physician who is dishonest with charting—making false statements or going back or “correcting” a chart later—loses credibility and the presumption of acting in good faith. That is disastrous for the physician.24

A hidden lesson

Another lesson, more human than legal, is that it matters how patients are treated when things go wrong. According to press reports, the parents felt that the ObGyn had not recognized that he had made any errors, did not apologize, and had even blamed the mother for the outcome. It does not require graduate work in psychology to expect that this approach would make the parents angry enough to pursue legal action. True regret, respect, and apologies are not panaceas, but they are important.25 Who gets sued and why is a key question that is part of a larger risk management plan. In this case, the magnitude of the injuries made a suit very likely, which is not the case with all bad outcomes.26 Honest communication with patients in the face of bad results remains the goal.27

Pulling it all together

Clinicians must always remain cognizant that the patient comes first and of the importance of working as a team with nursing staff and other allied health professionals. Excellent communication and support staff interaction in good times and bad can make a difference in patient outcomes and, indeed, in medical malpractice verdicts.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Chang D. Miami doctor’s call to broker during baby’s delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17−18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee Opinion No. 664: Refusal of medically recommended treatment during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;126(6):e175−e182.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Professional liability and risk management an essential guide for obstetrician-gynecologist. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Ghidini A, Stewart D, Pezzullo J, Locatelli A. Neonatal complications in vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: are they associated with number of pulls, cup detachments, and duration of vacuum application? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(1):67−73.

- Turkmen S. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in vacuum-assisted delivery with the Kiwi OmniCup and Malmstrom metal cup. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(2):207−213.

- Davis DJ. Neonatal subgaleal hemorrhage: diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2001;164(10):1452−1453.

- Chadwick LM, Pemberton PJ, Kurinczuk JJ. Neonatal subgaleal haematoma: associated risk factors, complications and outcome. J Paediatr Child Health. 1996;32(3):228−232.

- Dall’Asta A, Ghi T, Pedrazzi G, Frusca T. Does vacuum delivery carry a higher risk of shoulder dystocia? Review and metanalysis of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;201:62−68.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Outcomes. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Apgar scores as predictors of chronic neurologic disability. Pediatrics. 1981;68:36−44.

- ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 163: Fetal and neonatal neurologic injury. Int J. Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;41(1):97−101.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Antecedents of cerebral palsy. I. Univariate analysis of risks. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(10):1031−1038.

- Fenichel GM, Webster D, Wong WK. Intracranial hemorrhage in the term newborn. Arch Neurol. 1984;41(1):30−34.

- Peckham C. Medscape Malpractice Report 2015: Why Ob/Gyns Get Sued. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/malpractice-report-2015/obgyn#page=1. Published January 2016. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, Ibrahim AM, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36(4):43−53.

- Santos P, Ritter GA, Hefele JL, Hendrich A, McCoy CK. Decreasing intrapartum malpractice: Targeting the most injurious neonatal adverse events. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2015;34(4):20−27.

- Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, Singh H, Spittal MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354−362.

- Levine AS. Legal 101: Tort law and medical malpractice for physicians. Contemp OBGYN. http://www.contem poraryobgyn.net/obstetrics-gynecology-womens-health/legal-101-tort-law-and-medical-malpractice-physicians. Published July 17, 2015. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Smith SR, Sanfilippo JS. Applied Business Law. In: Sanfilippo JS, Bieber EJ, Javitch DG, Siegrist RB, eds. MBA for Healthcare. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016:91−126.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):340.e1–e6.

- Seegert L. Malpractice pitfalls: 5 strategies to reduce lawsuit threats. Medical Econ. http://www.medicaleconomics.com/medical-economics-blog/5-strategies-reduce-malpractice-lawsuit-threats. Published November 10, 2016. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Peckham C. Malpractice and medicine: who gets sued and why? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/855229. Published December 8, 2015. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- McMichael B. The failure of ‘sorry’: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3020352. Published August 16, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Carranza L, Lyerly AD, Lipira L, Prouty CD, Loren D, Gallagher TH. Delivering the truth: challenges and opportunities for error disclosure in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):656−659.

CASE Failure to perform cesarean delivery1–4

A 19-year-old woman (G1P0) received prenatal care at a federally funded health center. Her pregnancy was normal without complications. She presented to the hospital after spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM). The on-call ObGyn employed by the clinic was offsite when the mother was admitted.

The mother signed a standard consent form for vaginal and cesarean deliveries and any other surgical procedure required during the course of giving birth.

The ObGyn ordered low-dose oxytocin to augment labor in light of her SROM. Oxytocin was started at 9:46

Upon delivery, the infant was flaccid and not breathing. His Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 6 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively, and the cord pH was 7. The neonatal intensive care (NICU) team provided aggressive resuscitation.

At the time of trial, the 18-month-old boy was being fed through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube and had a tracheostomy that required periodic suctioning. The child was not able to stand, crawl, or support himself, and will require 24-hour nursing care for the rest of his life.

LAWSUIT. The parents filed a lawsuit in federal court for damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act (see “Notes about this case,”). The mother claimed that she had requested a cesarean delivery early in labor when FHR tracings showed fetal distress, and again prior to vacuum extraction; the ObGyn refused both times.

The ObGyn claimed that when he noted a category III tracing, he recommended cesarean delivery, but the patient refused. He recorded the refusal in the chart some time later, after he had noted the neonate’s appearance.

The parents’ expert testified that restarting oxytocin and using vacuum extraction multiple times were dangerous and gross deviations from acceptable practice. Prolonged and repetitive use of the vacuum extractor caused a large subgaleal hematoma that decreased blood flow to the fetal brain, resulting in irreversible central nervous system (CNS) damage secondary to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed at the first sign of fetal distress.

The defense expert pointed out that the ObGyn discussed the need for cesarean delivery with the patient when fetal distress occurred and that the ObGyn was bedside and monitoring the fetus and the mother. Although the mother consented to a cesarean delivery at time of admission, she refused to allow the procedure.

The labor and delivery (L&D) nurse corroborated the mother’s story that a cesarean delivery was not offered by the ObGyn, and when the patient asked for a cesarean delivery, he refused. The nurse stated that the note added to the records by the ObGyn about the mother’s refusal was a lie. If the mother had refused a cesarean, the nurse would have documented the refusal by completing a Refusal of Treatment form that would have been faxed to the risk manager. No such form was required because nothing was ever offered that the mother refused.

The nurse also testified that during the course of the latter part of labor, the ObGyn left the room several times to assist other patients, deliver another baby, and make an 8-minute phone call to his stockbroker. She reported that the ObGyn was out of the room when delivery occurred.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

Read about the verdict and medical considerations.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The medical care and the federal-court bench trial held in front of a judge (not a jury) occurred in Florida. The verdict suggests that the ObGyn breached the standard of care by not offering or proceeding with a cesarean delivery and this management resulted in the child’s injuries. The court awarded damages in the amount of $33,813,495.91, including $29,413,495.91 for the infant; $3,300,000.00 for the plaintiff; and $1,100,000.00 for her spouse.4

Medical considerations

Refusal of medical care

Although it appears that in this case the patient did not actually refuse medical care (cesarean delivery), the case does raise the question of refusal. Refusal of medical care has been addressed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) predicated upon care that supports maternal and fetal wellbeing.5 There may be a fine balance between safeguarding the pregnant woman’s autonomy and optimization of fetal wellbeing. “Forced compliance,” on the other hand, is the alternative to respecting refusal of treatment. Ethical issues come into play: patient rights; respect for autonomy; violations of bodily integrity; power differentials; and gender equality.5 The use of coercion is “not only ethically impermissible but also medically inadvisable secondary to the realities of prognostic uncertainty and the limitations of medical knowledge.”5 There is an obligation to elicit the patient’s reasoning and lived experience. Perhaps most importantly, as clinicians working to achieve a resolution, consideration of the following is appropriate5:

- reliability and validity of evidence-based medicine

- severity of the prospective outcome

- degree of risk or burden placed on the patient

- patient understanding of the gravity of the situation and risks

- degree of urgency.

Much of this boils down to the obligation to discuss “risks and benefits of treatment, alternatives and consequences of refusing treatment.”6

Complications from vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery

Ghidini and associates, in a multicenter retrospective study, evaluated complications relating to vacuum-assisted delivery. They listed major primary outcomes of subgaleal hemorrhage, skull fracture, and intracranial bleeding, and minor primary outcomes of cephalohematoma, scalp laceration, and extensive skin abrasions. Secondary outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of <7, umbilical artery pH of <7.10, shoulder dystocia, and NICU admission.7

A retrospective study from Sweden assessing all vacuum deliveries over a 2-year period compared the use of the Kiwi OmniCup (Clinical Innovations) to use of the Malmström metal cup (Medela). No statistical differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes as well as failure rates were noted. However, the duration of the procedure was longer and the requirement for fundal pressure was higher with the Malmström device.8

Subgaleal hemorrhage. Ghidini and colleagues reported a heightened incidence of head injury related to the duration of vacuum application and birth weight.7 Specifically, vacuum delivery devices increase the risk of subgaleal hemorrhage. Blood can accumulate between the scalp’s epicranial aponeurosis and the periosteum and potentially can extend forward to the orbital margins, backward to the nuchal ridge, and laterally to the temporal fascia. As much as 260 mL of blood can get into this subaponeurotic space in term babies.9 Up to one-quarter of babies who require NICU admission for this condition die.10 This injury seldom occurs with forceps.

Shoulder dystocia. In a meta-analysisfrom Italy, the vacuum extractor was associated with increased risk of shoulder dystocia compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery.11

Intrapartum hypoxia. In 2003, the ACOG Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy defined an acute intrapartum hypoxic event (TABLE).12

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as “a chronic neuromuscular disability characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture appearing early in life and not the result of recognized progressive disease.”13,14

The Collaborative Perinatal Project concluded that birth trauma plays a minimal role in development of CP.15 Arrested labor, use of oxytocin, or prolonged labor did not play a role. CP can develop following significant cerebral or posterior fossa hemorrhage in term infants.16

Perinatal asphyxia is a poor and imprecise term and use of the expression should be abandoned. Overall, 90% of children with CP do not have birth asphyxia as the underlying etiology.14

Prognostic assessment can be made, in part, by using the Sarnat classification system (classification scale for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of the newborn) or an electroencephalogram to stratify the severity of neonatal encephalopathy.12 Such tests are not stand-alone but a segment of assessment. At this point “a better understanding of the processes leading to neonatal encephalopathy and associated outcomes” appear to be required to understand and associate outcomes.12 “More accurate and reliable tools (are required) for prognostic forecasting.”12

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy involves multisystem organ failure including renal, hepatic, hematologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and metabolic abnormalities. There is no correlation between the degree of CNS injury and level of other organ abnormalities.12

Differential diagnosis

When events such as those described in this case occur, develop a differential diagnosis by considering the following12:

- uterine rupture

- severe placental abruption

- umbilical cord prolapse

- amniotic fluid embolus

- maternal cardiovascular collapse

- fetal exsanguination.

Read about the legal considerations.

Legal considerations

Although ObGyns are among the specialties most likely to experience malpractice claims,17 a verdict of more than $33 million is unusual.18 Despite the failure of adequate care, and the enormous damages, the ObGyn involved probably will not be responsible for paying the verdict (see “Notes about this case”). The case presents a number of important lessons and reminders for anyone practicing obstetrics.

A procedural comment

The case in this article arose under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA).1 Most government entities have sovereign immunity, meaning that they can be sued only with their consent. In the FTCA, the federal government consented to being sued for the acts of its employees. This right has a number of limitations and some technical procedures, but at its core, it permits the United States to be sued as though it was a private individual.2 Private individuals can be sued for the acts of the agents (including employees).

Although the FTCA is a federal law, and these cases are tried in federal court, the substantive law of the state applies. This case occurred in Florida, so Florida tort law, defenses, and limitation on claims applied here also. Had the events occurred in Iowa, Iowa law would have applied.

In FTCA cases, the United States is the defendant (generally it is the government, not the employee who is the defendant).3 In this case, the ObGyn was employed by a federal government entity to provide delivery services. As a result, the United States was the primary defendant, had the obligation to defend the suit, and will almost certainly be obligated to pay the verdict.

The case facts

Although this description is based on an actual case, the facts were taken from the opinion of the trial court, legal summaries and press reports and not from the full case documents.4-7 We could not independently assess the accuracy of the facts, but for the purpose of this discussion, we have assumed the facts to be correct. The government has apparently filed an appeal in the Eleventh Circuit.

References

- Federal Tort Claims Act. Vol 28 U.S.C. Pt.VI Ch.171 and 28 U.S.C. § 1346(b).

- About the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). Health Resources & Services Administration: Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/ftca/about/index.html. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Dowell MA, Scott CD. Federally Qualified Health Center Federal Tort Claims Act Insurance Coverage. Health Law. 2015;5:31-43.

- Chang D. Miami doctor's call to broker during baby's delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17-18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

Very large verdict

The extraordinary size of this verdict ($33 million without any punitive damages) is a reminder that in obstetrics, mistakes can have catastrophic consequences and very high costs.19 This fact is reflected in malpractice insurance rates.

A substantial amount of this case’s award will provide around-the-clock care for the child. This verdict was not the result of a runaway jury—it was a judge’s decision. It is also noteworthy to report that a small percentage of physicians (1%) appear responsible for a significant number (about one-third) of paid claims.20

Although the size of the verdict is unusual, the case is a fairly straightforward negligence tort. The judge found that the ObGyn had breached the duty of care for his patient. The actions that fell below the standard of care included restarting the oxytocin, using the Kiwi vacuum device 3 times, and failing to perform a cesarean delivery in light of obvious fetal distress. That negligence caused injury to the infant (and his parents).21 The judge determined that the 4 elements of negligence were present: 1) duty of care, 2) breach of that duty, 3) injury, and 4) a causal link between the breach of duty and the injury. The failure to adhere to good practice standards practically defines breach of duty.22

Multitasking

One important lesson is that multitasking, absence, and inattention can look terrible when things go wrong. Known as “hindsight bias,” the awareness that there was a disastrous result makes it easier to attribute the outcome to small mistakes that otherwise might seem trivial. This ObGyn was in and out of the room during a difficult labor. Perhaps that was understandable if it were unavoidable because of another delivery, but being absent frequently and not present for the delivery now looks very significant.23 And, of course, the 8-minute phone call to the stockbroker shines as a heartless, self-centered act of inattention.

Manipulating the record

Another lesson of this case: Do not manipulate the record. The ObGyn recorded that the patient had refused the cesarean delivery he recommended. Had that been the truth, it would have substantially improved his case. But apparently it was not the truth. Although there was circumstantial evidence (the charting of the patient’s refusal only after the newborn’s condition was obvious, failure to complete appropriate hospital forms), the most damning evidence was the direct testimony of the L&D nurse. She reported that, contrary to what the ObGyn put in the chart, the patient requested a cesarean delivery. In truth, it was the ObGyn who had refused.

A physician who is dishonest with charting—making false statements or going back or “correcting” a chart later—loses credibility and the presumption of acting in good faith. That is disastrous for the physician.24

A hidden lesson

Another lesson, more human than legal, is that it matters how patients are treated when things go wrong. According to press reports, the parents felt that the ObGyn had not recognized that he had made any errors, did not apologize, and had even blamed the mother for the outcome. It does not require graduate work in psychology to expect that this approach would make the parents angry enough to pursue legal action. True regret, respect, and apologies are not panaceas, but they are important.25 Who gets sued and why is a key question that is part of a larger risk management plan. In this case, the magnitude of the injuries made a suit very likely, which is not the case with all bad outcomes.26 Honest communication with patients in the face of bad results remains the goal.27

Pulling it all together

Clinicians must always remain cognizant that the patient comes first and of the importance of working as a team with nursing staff and other allied health professionals. Excellent communication and support staff interaction in good times and bad can make a difference in patient outcomes and, indeed, in medical malpractice verdicts.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Failure to perform cesarean delivery1–4

A 19-year-old woman (G1P0) received prenatal care at a federally funded health center. Her pregnancy was normal without complications. She presented to the hospital after spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM). The on-call ObGyn employed by the clinic was offsite when the mother was admitted.

The mother signed a standard consent form for vaginal and cesarean deliveries and any other surgical procedure required during the course of giving birth.

The ObGyn ordered low-dose oxytocin to augment labor in light of her SROM. Oxytocin was started at 9:46

Upon delivery, the infant was flaccid and not breathing. His Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 6 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively, and the cord pH was 7. The neonatal intensive care (NICU) team provided aggressive resuscitation.

At the time of trial, the 18-month-old boy was being fed through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube and had a tracheostomy that required periodic suctioning. The child was not able to stand, crawl, or support himself, and will require 24-hour nursing care for the rest of his life.

LAWSUIT. The parents filed a lawsuit in federal court for damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act (see “Notes about this case,”). The mother claimed that she had requested a cesarean delivery early in labor when FHR tracings showed fetal distress, and again prior to vacuum extraction; the ObGyn refused both times.

The ObGyn claimed that when he noted a category III tracing, he recommended cesarean delivery, but the patient refused. He recorded the refusal in the chart some time later, after he had noted the neonate’s appearance.

The parents’ expert testified that restarting oxytocin and using vacuum extraction multiple times were dangerous and gross deviations from acceptable practice. Prolonged and repetitive use of the vacuum extractor caused a large subgaleal hematoma that decreased blood flow to the fetal brain, resulting in irreversible central nervous system (CNS) damage secondary to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed at the first sign of fetal distress.

The defense expert pointed out that the ObGyn discussed the need for cesarean delivery with the patient when fetal distress occurred and that the ObGyn was bedside and monitoring the fetus and the mother. Although the mother consented to a cesarean delivery at time of admission, she refused to allow the procedure.

The labor and delivery (L&D) nurse corroborated the mother’s story that a cesarean delivery was not offered by the ObGyn, and when the patient asked for a cesarean delivery, he refused. The nurse stated that the note added to the records by the ObGyn about the mother’s refusal was a lie. If the mother had refused a cesarean, the nurse would have documented the refusal by completing a Refusal of Treatment form that would have been faxed to the risk manager. No such form was required because nothing was ever offered that the mother refused.

The nurse also testified that during the course of the latter part of labor, the ObGyn left the room several times to assist other patients, deliver another baby, and make an 8-minute phone call to his stockbroker. She reported that the ObGyn was out of the room when delivery occurred.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

Read about the verdict and medical considerations.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The medical care and the federal-court bench trial held in front of a judge (not a jury) occurred in Florida. The verdict suggests that the ObGyn breached the standard of care by not offering or proceeding with a cesarean delivery and this management resulted in the child’s injuries. The court awarded damages in the amount of $33,813,495.91, including $29,413,495.91 for the infant; $3,300,000.00 for the plaintiff; and $1,100,000.00 for her spouse.4

Medical considerations

Refusal of medical care

Although it appears that in this case the patient did not actually refuse medical care (cesarean delivery), the case does raise the question of refusal. Refusal of medical care has been addressed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) predicated upon care that supports maternal and fetal wellbeing.5 There may be a fine balance between safeguarding the pregnant woman’s autonomy and optimization of fetal wellbeing. “Forced compliance,” on the other hand, is the alternative to respecting refusal of treatment. Ethical issues come into play: patient rights; respect for autonomy; violations of bodily integrity; power differentials; and gender equality.5 The use of coercion is “not only ethically impermissible but also medically inadvisable secondary to the realities of prognostic uncertainty and the limitations of medical knowledge.”5 There is an obligation to elicit the patient’s reasoning and lived experience. Perhaps most importantly, as clinicians working to achieve a resolution, consideration of the following is appropriate5:

- reliability and validity of evidence-based medicine

- severity of the prospective outcome

- degree of risk or burden placed on the patient

- patient understanding of the gravity of the situation and risks

- degree of urgency.

Much of this boils down to the obligation to discuss “risks and benefits of treatment, alternatives and consequences of refusing treatment.”6

Complications from vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery

Ghidini and associates, in a multicenter retrospective study, evaluated complications relating to vacuum-assisted delivery. They listed major primary outcomes of subgaleal hemorrhage, skull fracture, and intracranial bleeding, and minor primary outcomes of cephalohematoma, scalp laceration, and extensive skin abrasions. Secondary outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of <7, umbilical artery pH of <7.10, shoulder dystocia, and NICU admission.7

A retrospective study from Sweden assessing all vacuum deliveries over a 2-year period compared the use of the Kiwi OmniCup (Clinical Innovations) to use of the Malmström metal cup (Medela). No statistical differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes as well as failure rates were noted. However, the duration of the procedure was longer and the requirement for fundal pressure was higher with the Malmström device.8

Subgaleal hemorrhage. Ghidini and colleagues reported a heightened incidence of head injury related to the duration of vacuum application and birth weight.7 Specifically, vacuum delivery devices increase the risk of subgaleal hemorrhage. Blood can accumulate between the scalp’s epicranial aponeurosis and the periosteum and potentially can extend forward to the orbital margins, backward to the nuchal ridge, and laterally to the temporal fascia. As much as 260 mL of blood can get into this subaponeurotic space in term babies.9 Up to one-quarter of babies who require NICU admission for this condition die.10 This injury seldom occurs with forceps.

Shoulder dystocia. In a meta-analysisfrom Italy, the vacuum extractor was associated with increased risk of shoulder dystocia compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery.11

Intrapartum hypoxia. In 2003, the ACOG Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy defined an acute intrapartum hypoxic event (TABLE).12

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as “a chronic neuromuscular disability characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture appearing early in life and not the result of recognized progressive disease.”13,14

The Collaborative Perinatal Project concluded that birth trauma plays a minimal role in development of CP.15 Arrested labor, use of oxytocin, or prolonged labor did not play a role. CP can develop following significant cerebral or posterior fossa hemorrhage in term infants.16

Perinatal asphyxia is a poor and imprecise term and use of the expression should be abandoned. Overall, 90% of children with CP do not have birth asphyxia as the underlying etiology.14

Prognostic assessment can be made, in part, by using the Sarnat classification system (classification scale for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of the newborn) or an electroencephalogram to stratify the severity of neonatal encephalopathy.12 Such tests are not stand-alone but a segment of assessment. At this point “a better understanding of the processes leading to neonatal encephalopathy and associated outcomes” appear to be required to understand and associate outcomes.12 “More accurate and reliable tools (are required) for prognostic forecasting.”12

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy involves multisystem organ failure including renal, hepatic, hematologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and metabolic abnormalities. There is no correlation between the degree of CNS injury and level of other organ abnormalities.12

Differential diagnosis

When events such as those described in this case occur, develop a differential diagnosis by considering the following12:

- uterine rupture

- severe placental abruption

- umbilical cord prolapse

- amniotic fluid embolus

- maternal cardiovascular collapse

- fetal exsanguination.

Read about the legal considerations.

Legal considerations

Although ObGyns are among the specialties most likely to experience malpractice claims,17 a verdict of more than $33 million is unusual.18 Despite the failure of adequate care, and the enormous damages, the ObGyn involved probably will not be responsible for paying the verdict (see “Notes about this case”). The case presents a number of important lessons and reminders for anyone practicing obstetrics.

A procedural comment

The case in this article arose under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA).1 Most government entities have sovereign immunity, meaning that they can be sued only with their consent. In the FTCA, the federal government consented to being sued for the acts of its employees. This right has a number of limitations and some technical procedures, but at its core, it permits the United States to be sued as though it was a private individual.2 Private individuals can be sued for the acts of the agents (including employees).

Although the FTCA is a federal law, and these cases are tried in federal court, the substantive law of the state applies. This case occurred in Florida, so Florida tort law, defenses, and limitation on claims applied here also. Had the events occurred in Iowa, Iowa law would have applied.

In FTCA cases, the United States is the defendant (generally it is the government, not the employee who is the defendant).3 In this case, the ObGyn was employed by a federal government entity to provide delivery services. As a result, the United States was the primary defendant, had the obligation to defend the suit, and will almost certainly be obligated to pay the verdict.

The case facts

Although this description is based on an actual case, the facts were taken from the opinion of the trial court, legal summaries and press reports and not from the full case documents.4-7 We could not independently assess the accuracy of the facts, but for the purpose of this discussion, we have assumed the facts to be correct. The government has apparently filed an appeal in the Eleventh Circuit.

References

- Federal Tort Claims Act. Vol 28 U.S.C. Pt.VI Ch.171 and 28 U.S.C. § 1346(b).

- About the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). Health Resources & Services Administration: Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/ftca/about/index.html. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Dowell MA, Scott CD. Federally Qualified Health Center Federal Tort Claims Act Insurance Coverage. Health Law. 2015;5:31-43.

- Chang D. Miami doctor's call to broker during baby's delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17-18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

Very large verdict

The extraordinary size of this verdict ($33 million without any punitive damages) is a reminder that in obstetrics, mistakes can have catastrophic consequences and very high costs.19 This fact is reflected in malpractice insurance rates.

A substantial amount of this case’s award will provide around-the-clock care for the child. This verdict was not the result of a runaway jury—it was a judge’s decision. It is also noteworthy to report that a small percentage of physicians (1%) appear responsible for a significant number (about one-third) of paid claims.20

Although the size of the verdict is unusual, the case is a fairly straightforward negligence tort. The judge found that the ObGyn had breached the duty of care for his patient. The actions that fell below the standard of care included restarting the oxytocin, using the Kiwi vacuum device 3 times, and failing to perform a cesarean delivery in light of obvious fetal distress. That negligence caused injury to the infant (and his parents).21 The judge determined that the 4 elements of negligence were present: 1) duty of care, 2) breach of that duty, 3) injury, and 4) a causal link between the breach of duty and the injury. The failure to adhere to good practice standards practically defines breach of duty.22

Multitasking

One important lesson is that multitasking, absence, and inattention can look terrible when things go wrong. Known as “hindsight bias,” the awareness that there was a disastrous result makes it easier to attribute the outcome to small mistakes that otherwise might seem trivial. This ObGyn was in and out of the room during a difficult labor. Perhaps that was understandable if it were unavoidable because of another delivery, but being absent frequently and not present for the delivery now looks very significant.23 And, of course, the 8-minute phone call to the stockbroker shines as a heartless, self-centered act of inattention.

Manipulating the record

Another lesson of this case: Do not manipulate the record. The ObGyn recorded that the patient had refused the cesarean delivery he recommended. Had that been the truth, it would have substantially improved his case. But apparently it was not the truth. Although there was circumstantial evidence (the charting of the patient’s refusal only after the newborn’s condition was obvious, failure to complete appropriate hospital forms), the most damning evidence was the direct testimony of the L&D nurse. She reported that, contrary to what the ObGyn put in the chart, the patient requested a cesarean delivery. In truth, it was the ObGyn who had refused.

A physician who is dishonest with charting—making false statements or going back or “correcting” a chart later—loses credibility and the presumption of acting in good faith. That is disastrous for the physician.24

A hidden lesson

Another lesson, more human than legal, is that it matters how patients are treated when things go wrong. According to press reports, the parents felt that the ObGyn had not recognized that he had made any errors, did not apologize, and had even blamed the mother for the outcome. It does not require graduate work in psychology to expect that this approach would make the parents angry enough to pursue legal action. True regret, respect, and apologies are not panaceas, but they are important.25 Who gets sued and why is a key question that is part of a larger risk management plan. In this case, the magnitude of the injuries made a suit very likely, which is not the case with all bad outcomes.26 Honest communication with patients in the face of bad results remains the goal.27

Pulling it all together

Clinicians must always remain cognizant that the patient comes first and of the importance of working as a team with nursing staff and other allied health professionals. Excellent communication and support staff interaction in good times and bad can make a difference in patient outcomes and, indeed, in medical malpractice verdicts.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Chang D. Miami doctor’s call to broker during baby’s delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17−18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee Opinion No. 664: Refusal of medically recommended treatment during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;126(6):e175−e182.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Professional liability and risk management an essential guide for obstetrician-gynecologist. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Ghidini A, Stewart D, Pezzullo J, Locatelli A. Neonatal complications in vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: are they associated with number of pulls, cup detachments, and duration of vacuum application? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(1):67−73.

- Turkmen S. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in vacuum-assisted delivery with the Kiwi OmniCup and Malmstrom metal cup. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(2):207−213.

- Davis DJ. Neonatal subgaleal hemorrhage: diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2001;164(10):1452−1453.

- Chadwick LM, Pemberton PJ, Kurinczuk JJ. Neonatal subgaleal haematoma: associated risk factors, complications and outcome. J Paediatr Child Health. 1996;32(3):228−232.

- Dall’Asta A, Ghi T, Pedrazzi G, Frusca T. Does vacuum delivery carry a higher risk of shoulder dystocia? Review and metanalysis of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;201:62−68.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Outcomes. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Apgar scores as predictors of chronic neurologic disability. Pediatrics. 1981;68:36−44.

- ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 163: Fetal and neonatal neurologic injury. Int J. Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;41(1):97−101.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Antecedents of cerebral palsy. I. Univariate analysis of risks. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(10):1031−1038.

- Fenichel GM, Webster D, Wong WK. Intracranial hemorrhage in the term newborn. Arch Neurol. 1984;41(1):30−34.

- Peckham C. Medscape Malpractice Report 2015: Why Ob/Gyns Get Sued. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/malpractice-report-2015/obgyn#page=1. Published January 2016. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, Ibrahim AM, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36(4):43−53.

- Santos P, Ritter GA, Hefele JL, Hendrich A, McCoy CK. Decreasing intrapartum malpractice: Targeting the most injurious neonatal adverse events. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2015;34(4):20−27.

- Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, Singh H, Spittal MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354−362.

- Levine AS. Legal 101: Tort law and medical malpractice for physicians. Contemp OBGYN. http://www.contem poraryobgyn.net/obstetrics-gynecology-womens-health/legal-101-tort-law-and-medical-malpractice-physicians. Published July 17, 2015. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Smith SR, Sanfilippo JS. Applied Business Law. In: Sanfilippo JS, Bieber EJ, Javitch DG, Siegrist RB, eds. MBA for Healthcare. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016:91−126.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):340.e1–e6.

- Seegert L. Malpractice pitfalls: 5 strategies to reduce lawsuit threats. Medical Econ. http://www.medicaleconomics.com/medical-economics-blog/5-strategies-reduce-malpractice-lawsuit-threats. Published November 10, 2016. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Peckham C. Malpractice and medicine: who gets sued and why? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/855229. Published December 8, 2015. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- McMichael B. The failure of ‘sorry’: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3020352. Published August 16, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Carranza L, Lyerly AD, Lipira L, Prouty CD, Loren D, Gallagher TH. Delivering the truth: challenges and opportunities for error disclosure in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):656−659.

- Chang D. Miami doctor’s call to broker during baby’s delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17−18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee Opinion No. 664: Refusal of medically recommended treatment during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;126(6):e175−e182.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Professional liability and risk management an essential guide for obstetrician-gynecologist. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Ghidini A, Stewart D, Pezzullo J, Locatelli A. Neonatal complications in vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: are they associated with number of pulls, cup detachments, and duration of vacuum application? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(1):67−73.

- Turkmen S. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in vacuum-assisted delivery with the Kiwi OmniCup and Malmstrom metal cup. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(2):207−213.

- Davis DJ. Neonatal subgaleal hemorrhage: diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2001;164(10):1452−1453.

- Chadwick LM, Pemberton PJ, Kurinczuk JJ. Neonatal subgaleal haematoma: associated risk factors, complications and outcome. J Paediatr Child Health. 1996;32(3):228−232.

- Dall’Asta A, Ghi T, Pedrazzi G, Frusca T. Does vacuum delivery carry a higher risk of shoulder dystocia? Review and metanalysis of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;201:62−68.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Outcomes. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Apgar scores as predictors of chronic neurologic disability. Pediatrics. 1981;68:36−44.

- ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 163: Fetal and neonatal neurologic injury. Int J. Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;41(1):97−101.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Antecedents of cerebral palsy. I. Univariate analysis of risks. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(10):1031−1038.

- Fenichel GM, Webster D, Wong WK. Intracranial hemorrhage in the term newborn. Arch Neurol. 1984;41(1):30−34.

- Peckham C. Medscape Malpractice Report 2015: Why Ob/Gyns Get Sued. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/malpractice-report-2015/obgyn#page=1. Published January 2016. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, Ibrahim AM, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36(4):43−53.

- Santos P, Ritter GA, Hefele JL, Hendrich A, McCoy CK. Decreasing intrapartum malpractice: Targeting the most injurious neonatal adverse events. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2015;34(4):20−27.

- Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, Singh H, Spittal MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354−362.

- Levine AS. Legal 101: Tort law and medical malpractice for physicians. Contemp OBGYN. http://www.contem poraryobgyn.net/obstetrics-gynecology-womens-health/legal-101-tort-law-and-medical-malpractice-physicians. Published July 17, 2015. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Smith SR, Sanfilippo JS. Applied Business Law. In: Sanfilippo JS, Bieber EJ, Javitch DG, Siegrist RB, eds. MBA for Healthcare. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016:91−126.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):340.e1–e6.

- Seegert L. Malpractice pitfalls: 5 strategies to reduce lawsuit threats. Medical Econ. http://www.medicaleconomics.com/medical-economics-blog/5-strategies-reduce-malpractice-lawsuit-threats. Published November 10, 2016. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Peckham C. Malpractice and medicine: who gets sued and why? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/855229. Published December 8, 2015. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- McMichael B. The failure of ‘sorry’: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3020352. Published August 16, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Carranza L, Lyerly AD, Lipira L, Prouty CD, Loren D, Gallagher TH. Delivering the truth: challenges and opportunities for error disclosure in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):656−659.