User login

Dear patients: Letters psychiatrists should and should not write

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

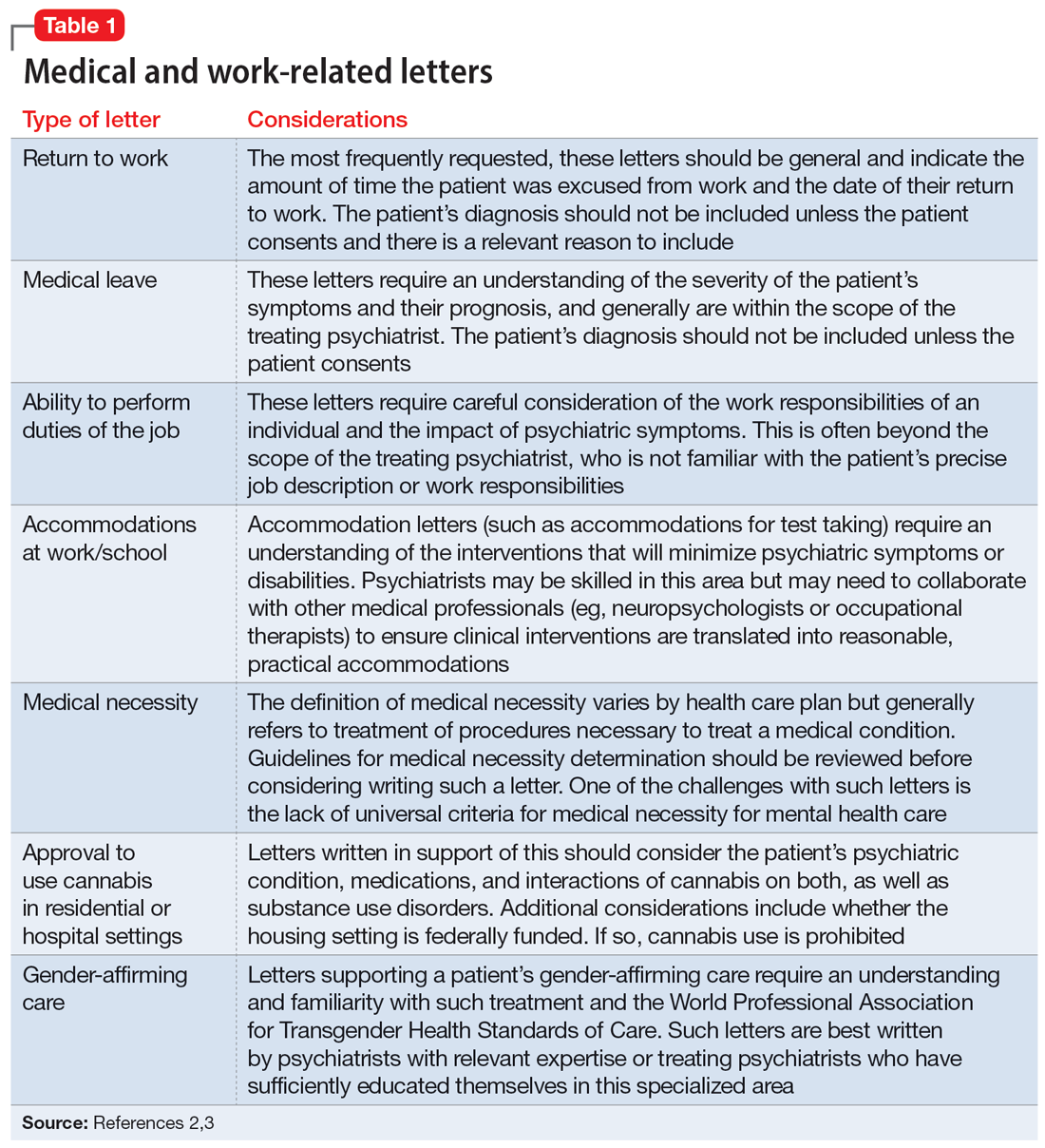

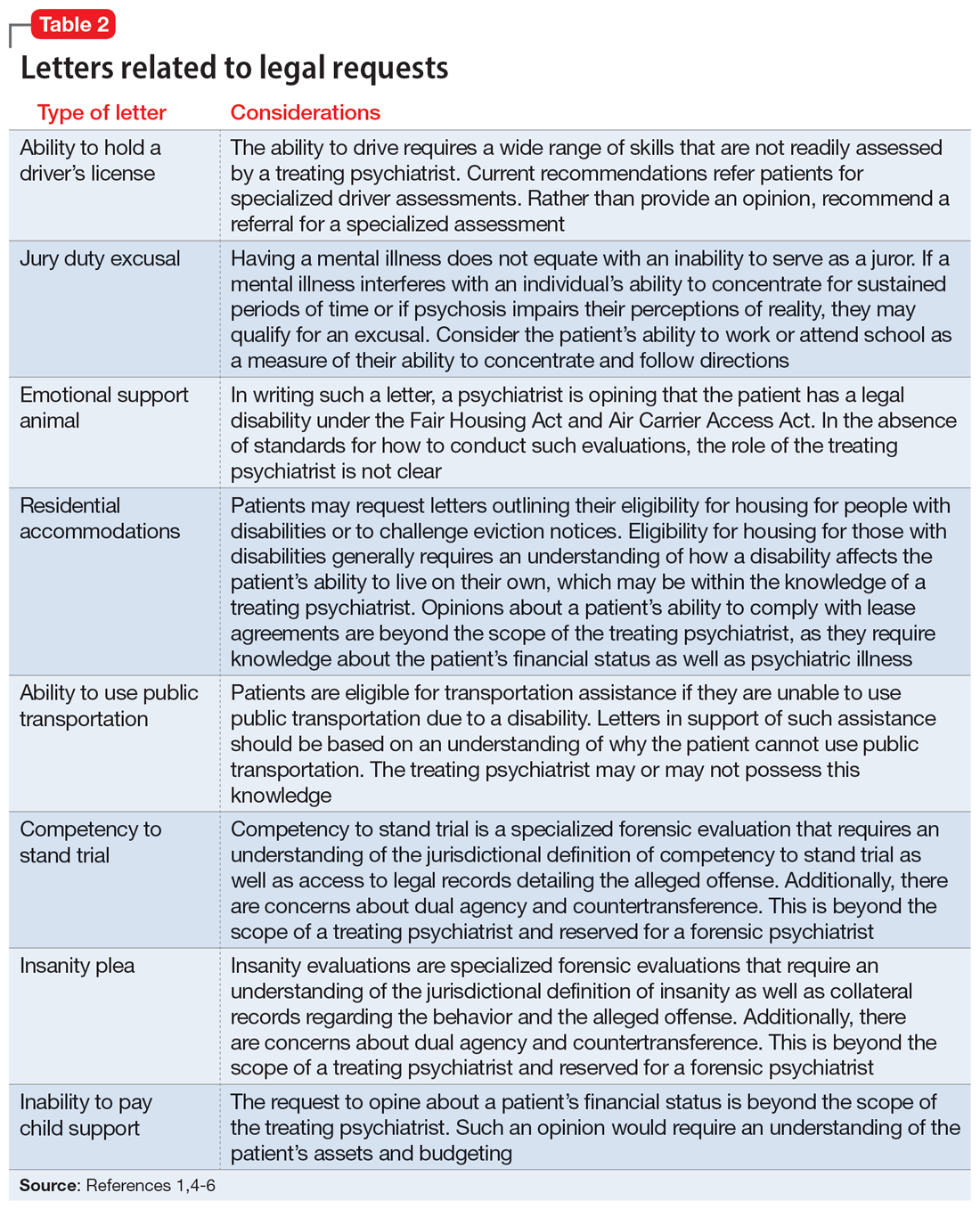

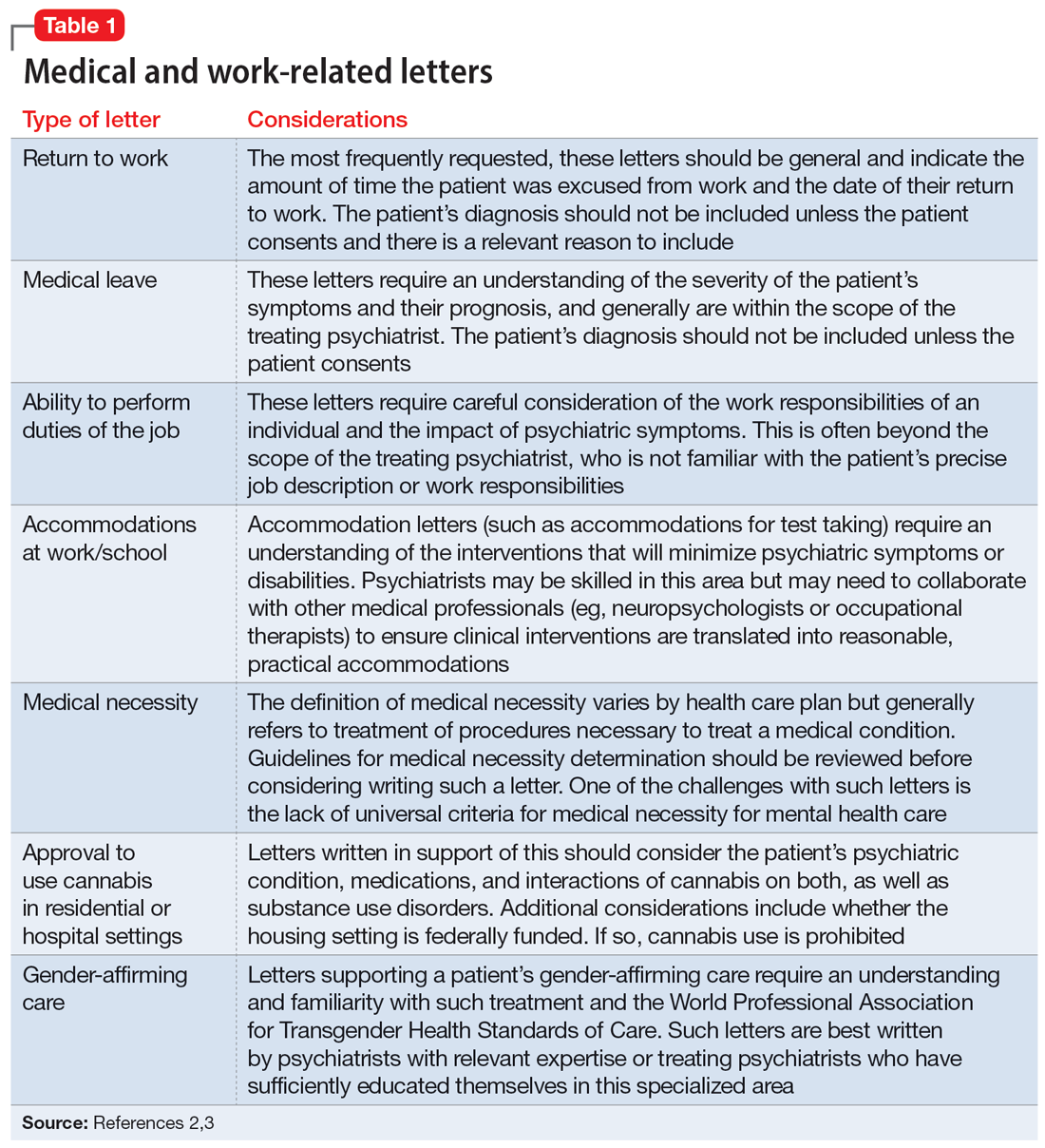

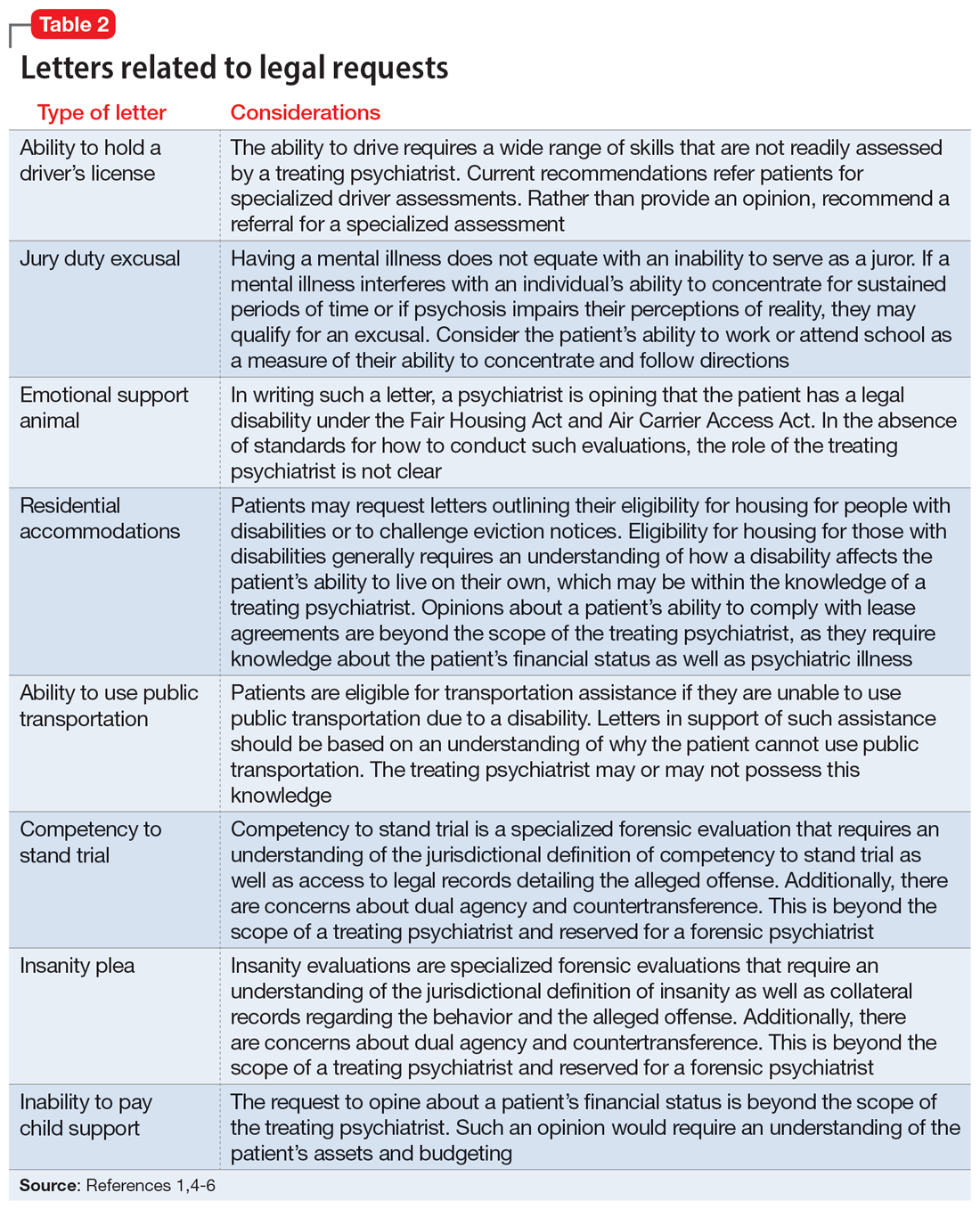

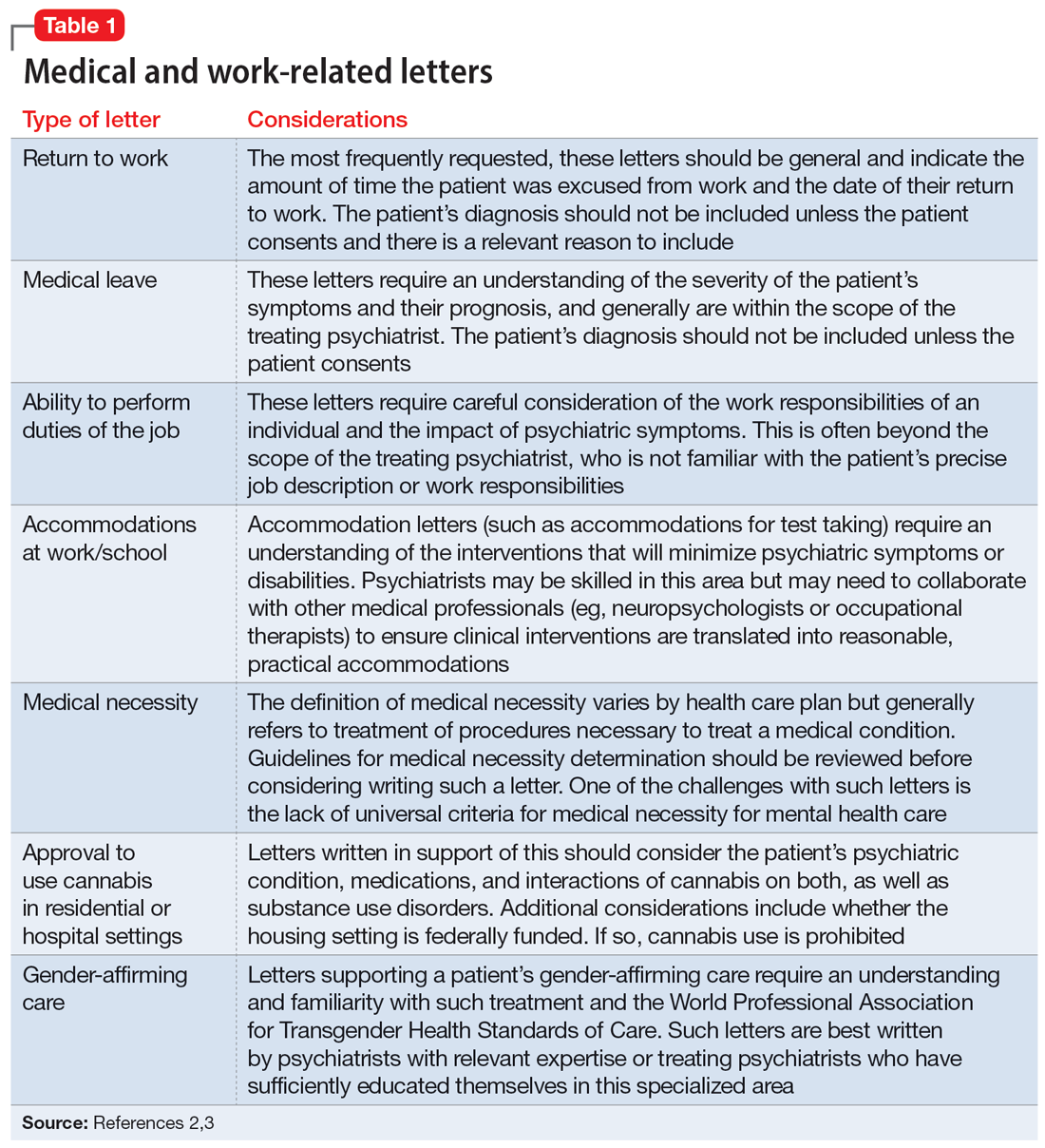

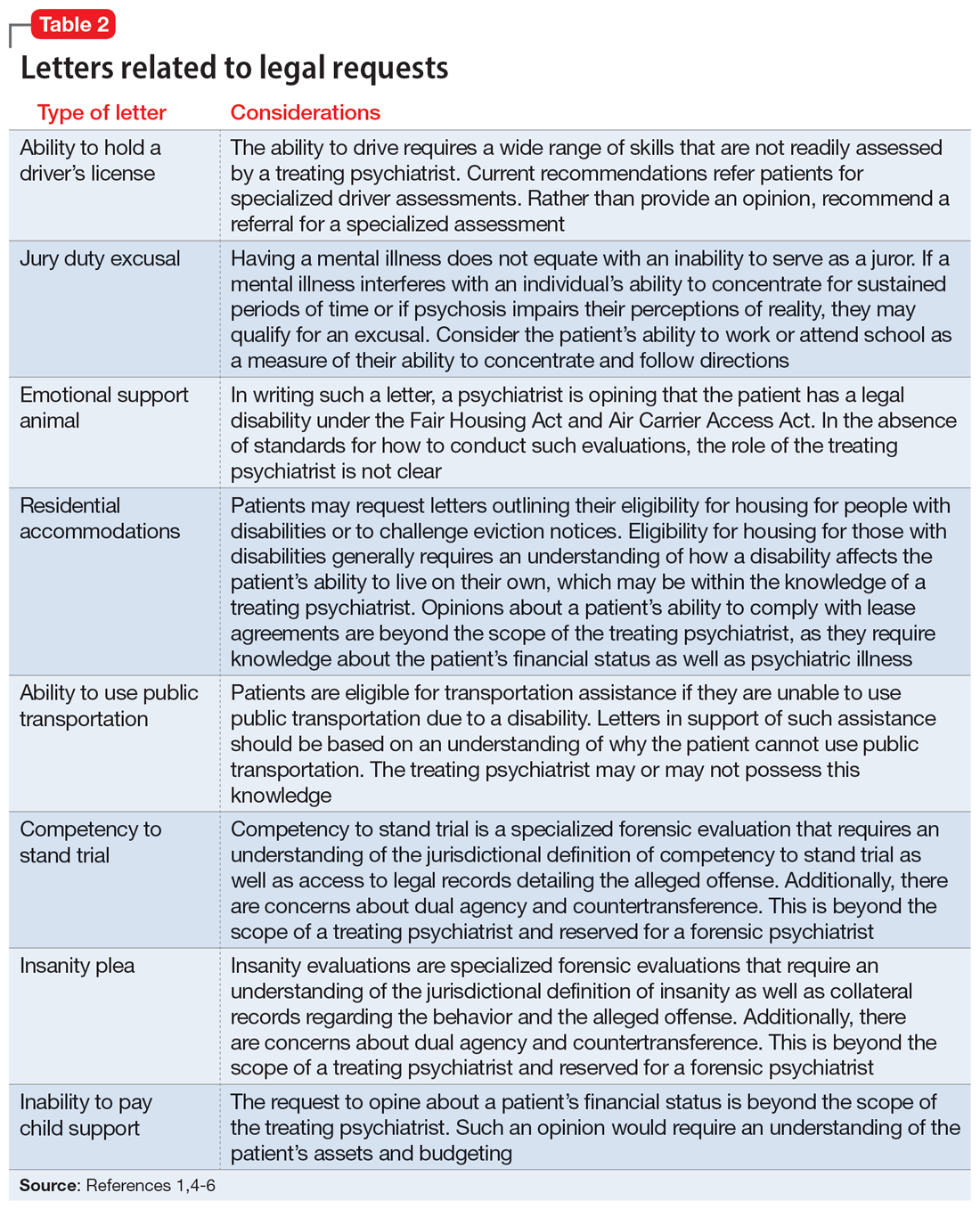

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

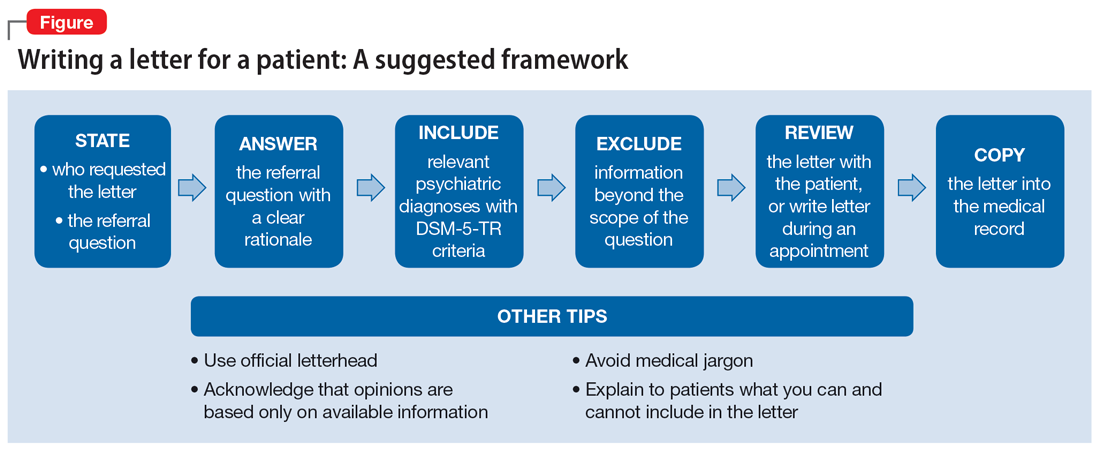

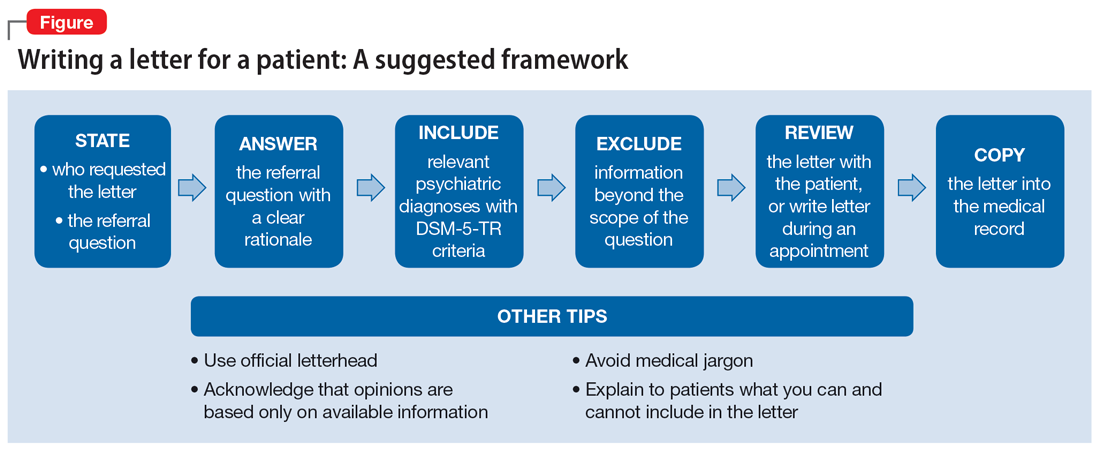

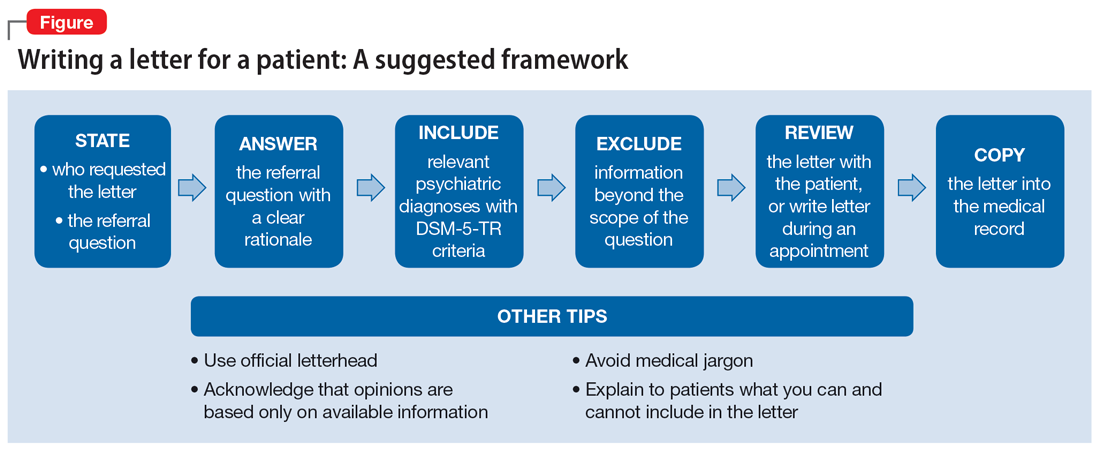

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

The medical profession and the 2022 ̶ 2023 Term of the Supreme Court

The 2022-2023 Term of the Supreme Court illustrates how important the Court has become to health-related matters, including decisions regarding the selection and training of new professionals, the daily practice of medicine, and the future availability of new drugs. The importance of several cases is reinforced by the fact that major medical organizations filed amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs in those cases.

Amicus briefs are filed by individuals or organizations with something significant to say about a case to the court—most often to present a point of view, make an argument, or provide information that the parties to the case may not have communicated. Amicus briefs are burdensome in terms of the time, energy, and cost of preparing and filing. Thus, they are not undertaken lightly. Medical organizations submitted amicus briefs in the first 3 cases we consider.

Admissions, race, and diversity

The case: Students for Fair Admissions v President and Fellows of Harvard College

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) joined an amici curiae brief in Students for Fair Admissions v President and Fellows of Harvard College (and the University of North Carolina [UNC]).1 This case challenged the use of racial preferences in college admissions. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) was the lead organization; nearly 40 other health-related organizations joined the brief.

The legal claim. Those filing the suits asserted that racial preferences by public colleges violate the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause (“no state shall deny to any person … the equal protection of the law”). That is, if a state university gives racial preferences in selective admissions, it denies some other applicant the equal protection of the law. As for private schools (in this case, Harvard), Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has the same standards as the Equal Protection Clause. Thus, the Court consolidated the cases and used the same legal standard in considering public and private colleges (with “colleges” including professional and graduate programs as well as undergraduate institutions).

Background. For nearly 50 years, the Supreme Court has allowed limited racial preferences in college admissions. Those preferences could only operate as a plus, however, and not a negative for applicants and be narrowly tailored. The measure was instituted temporarily; in a 2003 case, the Court said, “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.”2

Decision. In a 6-3 decision, the Court held (in the UNC case) that racial preferences generally violate the Constitution, and by a 6-2 decision (in the Harvard case) these preferences violate the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (Justice Jackson was recused in the Harvard case because of a conflict.) The opinion covered 237 pages in the US Reports, so any summary is incomplete.

The majority concluded, “The Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today.”3

There were 3 concurring opinions and 2 dissents in the case. The concurrences reviewed the history of the Equal Protection Clause and the Civil Rights Act, the damage racial preferences can do, and the explicit limits the Court said there must be on racial preferences in higher education. The dissents had a different view of the legal history of the 14th Amendment. They said the majority was turning a blind eye to segregation in society and the race-based gap in America.

As a practical matter, this case means that colleges, including professional schools, cannot use racial preferences. The Court said that universities may consider essays and the like in which applicants describe how their own experiences as an individual (including race) have affected their own lives. However, the Court cautioned that “universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.”3

Continue to: The amici brief...

The amici brief

ACOG joined 40 other health-related organizations in filing an amici brief (multiple “friends”) in Students for Fair Admission. The AAMC led the brief, with the others signing as amici.4 The brief made 3 essential points: diversity in medical education “markedly improves health outcomes,” and a loss of diversity “threaten[s] patients’ health; medical schools engage in an intense “holistic” review of applicants for admission; and medical schools must consider applicants’ “full background” (including race) to achieve their educational and professional goals.4

A powerful part of the brief described the medical school admissions process, particularly the very “holistic” review that is not entirely dependent on admissions scores. The brief effectively weaves the consideration of race into this process, mentioning race (on page 22) only after discussing many other admissions factors.

Child custody decisions related to the Indian Child Welfare Act

The case: Haaland v Brackeen

The American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Academy of Pediatrics filed a brief in Haaland v Brackeen5 involving the constitutionality of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). The statute followed a terrible history of Indian children being removed from their families inappropriately, as detailed in a concurring opinion by Justice Gorsuch.5 The two purposes of the act were to promote raising Native American children in their culture and stem the downward trend in tribal membership.

The legal claim. The Court consolidated several cases. Essentially, a 10-month-old child (A.L.M.) was placed in foster care with the Brackeens in Texas. After more than 1 year, the Brackeens sought adoption; the biological father, mother, and grandparents all supported it. The Navajo and Cherokee Nations objected and informed the Texas court that they had found alternative placement with (nonrelative) tribal members in New Mexico. The “court-appointed guardian and a psychological expert … described the strong emotional bond between A.L.M. and his foster parents.” The court denied the adoption petition based on ICWA’s preference for tribe custody, and the Brackeens filed a lawsuit.

Decision. The constitutional claim in the case was that Congress lacked the authority to impose these substantial rules on states in making child custody decisions. The Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, upheld the constitutionality of the ICWA.

The amici brief

The joint amici brief of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the AMA argued that tribes are “extended families” of Native American children.6 It noted the destructive history of removing Native American children from their families and suggested that kinship care improves children’s health. To its credit, the brief also honestly noted the serious mental health and suicide rates in some tribes, which suggest issues that might arise in child custody and adoption cases.

The Court did not, in this case, take up another constitutional issue that the parties raised—whether the strong preference for Native American over non ̶ Native American custody violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Court said the parties to this case did not have standing to raise the issue. Justice Kavanaugh, concurring, said it was a “serious” issue and invited it to be raised in another case.5

False Claims Act cases

The case: Costs for SuperValu prescriptions

The legal claim. One FCA case this Term involved billings SuperValu made for outpatient prescriptions in Medicare-Medicaid programs. As its “usual and customary” costs, it essentially reported a list price that did not include the substantial discounts it commonly gave.

Background. Subjective knowledge (what the defendant actually knows) may seem impossible to prove—the defendant could just say, “I did not know I was doing wrong.” Over time the law has developed several ways of demonstrating “knowing.” Justice Thomas, writing for a unanimous Court, held that whistleblowers or the government might prove “knowing” in 3 ways:

1. defendants “actually knew that their reported prices were not their ‘usual and customary’ prices when they reported them”

2. were aware of a substantial risk that their higher, retail prices were not their “usual and customary” prices and intentionally avoided learning whether their reports were accurate

3. were aware of such a substantial and unjustifiable risk but submitted the claims anyway.9

Of course, records of the company, information from the whistleblower, and circumstantial evidence may be used to prove any of these; it does not require the company’s admission.

The Court said that if the government or whistleblowers make a showing of any of these 3 things, it is enough.

Decision. The case was returned to the lower court to apply these rules.

The amici brief

The American Hospital Association and America’s Health Insurance Plans filed an amici brief.10 It reminded the Court that many reimbursement regulations are unclear. Therefore, it is inappropriate to impose FCA liability for guessing incorrectly what the regulations mean. Having to check on every possible ambiguity was unworkable. The Court declined, however, the suggestion that defendants should be able to use any one of many “objectively” reasonable interpretations of regulations.

Continue to: The case: Polansky v Executive Health Resources...

The case: Polansky v Executive Health Resources

Health care providers who dislike the FCA may find solace this Term in this second FCA case.11

The legal claim. Polansky, a physician employed by a medical billing company, became an “intervenor” in a suit claiming the company assisted hospitals in false billing (inpatient claims for outpatient services). The government sought to dismiss the case, but Polansky refused.

Decision. The case eventually reached the Supreme Court, which held that the government may enter an FCA case at any time and move to dismiss the case even over the objection of a whistleblower. The government does not seek to enter a case in order to file dismissal motions often. When it does so, whistleblowers are protected by the fact that the dismissal motion requires a hearing before the federal court.

An important part of this case has escaped much attention. Justices Thomas, Kavanaugh, and Barrett invited litigation to determine if allowing private whistleblowers to represent the government’s interest is consistent with Article II of the Constitution.11 The invitation will likely be accepted. We expect to see cases challenging the place of “intervenors” pursuing claims when the government has declined to take up the case. The private intervenor is a crucial provision of the current FCA, and if such a challenge were successful, it could substantially reduce FCA cases.

Criminal false claims

Dubin overbilled Medicaid for psychological testing by saying the testing was done by a licensed psychologist rather than an assistant. The government claimed the “identity theft” was using the patient’s (actual) Medicaid number in submitting the bill.12 The Court unanimously held the overbilling was not aggravated identity theft as defined in federal law. Dubin could be convicted of fraudulent billing but not aggravated identity theft, thereby avoiding the mandatory prison term.

Patents of “genus” targets

The case: Amgen v Sanofi

Background. “Genus” patents allow a single pharmaceutical company to patent every antibody that binds to a specific amino acid on a naturally occurring protein. In this case, the patent office had granted a “genus” patent on “all antibodies” that bind to the naturally occurring protein PCSK9 and block it from hindering the body’s mechanism for removing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol from the bloodstream,13 helping to reduce LDL cholesterol levels. These patents could involve millions of antibodies—and Amgen was claiming a patent on all of them. Amgen and Sanofi marketed their products, each with their own unique amino acid sequence.13 Amgen sued Sanofi for violating its patent rights.

Decision. The Court unanimously held that Amgen did not have a valid patent on all antibodies targeting PCSK9, only those that it had explicitly described in its patent application—a ruling based on a 150-year-old technical requirement for receiving a patent. An applicant for a patent must include “a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art…to make and use the same.”13 Amgen’s patent provided the description for only a few of the antibodies, but from the description in its application others could not “make and use” all of the antibodies targeting PCSK9.

While the decision was vital for future pharmaceuticals, the patent principle on which it was based has an interesting history. The Court noted that it affected the telegraph (Morse lost part of his patent), electric lights (Edison won his case against other inventors), and the glue for wood veneering (Perkins Glue Company lost).13

Continue to: Other notable decisions...

Other notable decisions

Student loans

The Court struck down the Biden Administration’s student loan forgiveness program, which would have cost approximately $430 billion.14 The central issue was whether the administration had the authority for such massive loan forgiveness; that is, whether Congress had authorized the broad loan forgiveness. The administration claimed authority from the post ̶ 9/11 HEROES Act, which allows the Secretary of Education to “waive or modify” loan provisions during national emergencies.

Free speech and the wedding web designer

303 Creative v Elenis involved a creative website designer who did not want to be required to create a website for a gay wedding.15 The designer had strong beliefs against same-sex marriages, but Colorado sought to force her to do so under the state “public accommodations” law. In a 6-3 decision, the Court held that the designer had a “free speech” right. That is, the state could not compel her to undertake speech expressing things she did not believe. This was because the website design was an expressive, creative activity and therefore was “speech” under the First Amendment.

Wetlands and the Clean Water Act

The essential issue in Sackett v Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was the definitions of waters of the United States and related wetlands. The broad definition the EPA used meant it had jurisdiction to regulate an extraordinary amount of territory. It had, for example, prevented the Sacketts from building a modest house claiming it was part of the “waters of the United States because they were near a ditch that fed into a creek, which fed into Priest Lake, a navigable, intrastate lake.” The Court held that the EPA exceeded its statutory authority to define “wetlands.”16

The Court held that under the Clean Water Act, for the EPA to establish jurisdiction over adjacent wetlands, it must demonstrate that16:

1. “the adjacent body of water constitutes waters of the United States (ie, a relatively permanent body of water connected to traditional interstate navigable waters)…”

2. “…the wetland has a continuous surface connection with that water, making it difficult to determine where the water ends, and the wetland begins.”

Under this definition, the Sacketts could build their house. This was a statutory interpretation case. Therefore, Congress can expand or otherwise change the EPA’s authority under the Clean Water Act and other legislation.

Conclusions: A new justice, “shadow docket,” and ethics rules

SCOTUS’ newest member. When the Marshall called the Court into session on October 3, 2022, it had a new member, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. She was sworn in on June 30, 2022, when her predecessor (Justice Breyer) officially retired. She had been a law clerk for Justice Breyer in 1999, as well as a district court judge and court of appeals judge. Those who count such things described her as the “chattiest justice.”17 She spoke more than any other justice—by one count, a total of 75,632 words (an average of 1,300 words in each of the 58 arguments).

A more balanced Court? Most commentators view the Court as more balanced or less conservative than the previous Term. For example, Justice Sotomayor was in the majority 40% last Term but 65% this Term. Justice Thomas was in the majority 75% last Term but 55% this Term. Put another way, this Term in the divided cases, the liberal justices were in the majority 64% of the time, compared with the conservative justices 73%.18 Of course, these differences may reflect a different set of cases rather than a change in the direction of the Court. There were 11 (or 12, depending on how 1 case is counted) 6-3 cases, but only 5 were considered ideological. That suggests that, in many cases, the coalitions were somewhat fluid.

“Shadow docket” controversy continues.19 Shadow docket refers to orders the Court makes that do not follow oral arguments and often do not have written opinions. The orders are all publicly available. This Term a close examination of the approximately 30 shadow docket opinions shows that the overwhelming majority were dissents or explanations about denials of certiorari. The Court ordered only a few stays or injunctions via the shadow docket. One shadow docket stay (that prevented a lower court order from going into effect) is particularly noteworthy. A federal judge had ordered the suspension of the distribution of mifepristone while courts considered claims that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had improperly approved the drug. In a shadow docket order, the Court issued the stay to allow mifepristone to be sold while the case challenging its approval was heard.20 The only opinion was a dissent from Justice Alito. But it also demonstrates the importance of the shadow docket. Without this intervention, in at least part of the country, the distribution of mifepristone would have been interrupted pending the outcome of the FDA cases.

In August, the Court delayed a settlement in the Purdue Pharma liability bankruptcy case.21 It also stayed an injunction of a lower court, thereby permitting federal “ghost guns” regulations to go into effect at least temporarily.22

More ethics rules to come? Another area in which the Court faced criticism was formal ethics rules. The justices make financial disclosures, but these are somewhat ambiguous. There is likely to be increasing pressure for a more complete disclosure of non-financial relationships and more formal ethics rules. ●

The Court had, by September 1, 2023, accepted 22 cases for hearing next Term.1 The cases include a challenge to the extraordinary funding provision for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, another racial challenge to congressional districts (South Carolina), the status of Americans with Disability Act “testers” who look for violations without ever intending to use the facilities, the level of deference courts should give to interpreting federal statutes (so-called “Chevron” deference), the opioid (OxyContin ) bankruptcy, and limitations on gun ownership. This represents less than half of the cases the Court will likely hear next Term, so the Court will add many more cases to the docket. It promises to be an appealing Term.

Reference

1. October Term 2023. SCOTUSblog website. Accessed August 29, 2023. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/terms/ot2023/

When the Court adjourned on June 30, 2023, it had considered 60 cases, plus hundreds of petitions asking it to hear cases. Most commentators count 55 cases decided after briefing and oral argument and where there was a signed opinion. The information below uses 55 cases unless otherwise noted. During the 2022-2023 Term, the Court:

- upheld liability for the involuntary administration of psychotropic drugs in nursing home1

- permitted disabled students, in some instances, both to make Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) claims for services and to file Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) lawsuits against their schools2

- upheld a statute that makes it illegal to “encourage or induce an alien to come to, enter, or reside in the United States, knowing or in reckless disregard of the fact that such coming to, entry, or residence is or will be in violation of law.” The defendant had used a scam promising noncitizens “adult adoptions” (of which there is no such thing) making it legal for them to come to and stay in the United States.3

- narrowed the “fair use” of copyrighted works. It held that Andy Warhol’s use of a copyrighted photograph in his famous Prince prints was not “transformative” in a legal sense largely because the photo and prints “share the same use”—magazine illustrations.4

- in another intellectual property case, held that Jack Daniel’s might sue a dog toy maker for a rubber dog toy that looked like a Jack Daniel’s bottle5

- further expanded the Federal Arbitration Act by holding that a federal district court must immediately stay court proceedings if one party is appealing a decision not to require arbitration6

- held that two social media companies were not responsible for terrorists using their platforms to recruit others to their cause. It did not, however, decide whether §230 of the Communication Decency Act protects companies from liability.7

- made it easier for employees to receive accommodation for their religious practices and beliefs. Employers must make religious accommodations unless the employer can show that “the burden of granting an accommodation would result in substantial increased [financial and other] costs in relation to the conduct of its particular business.”8