User login

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

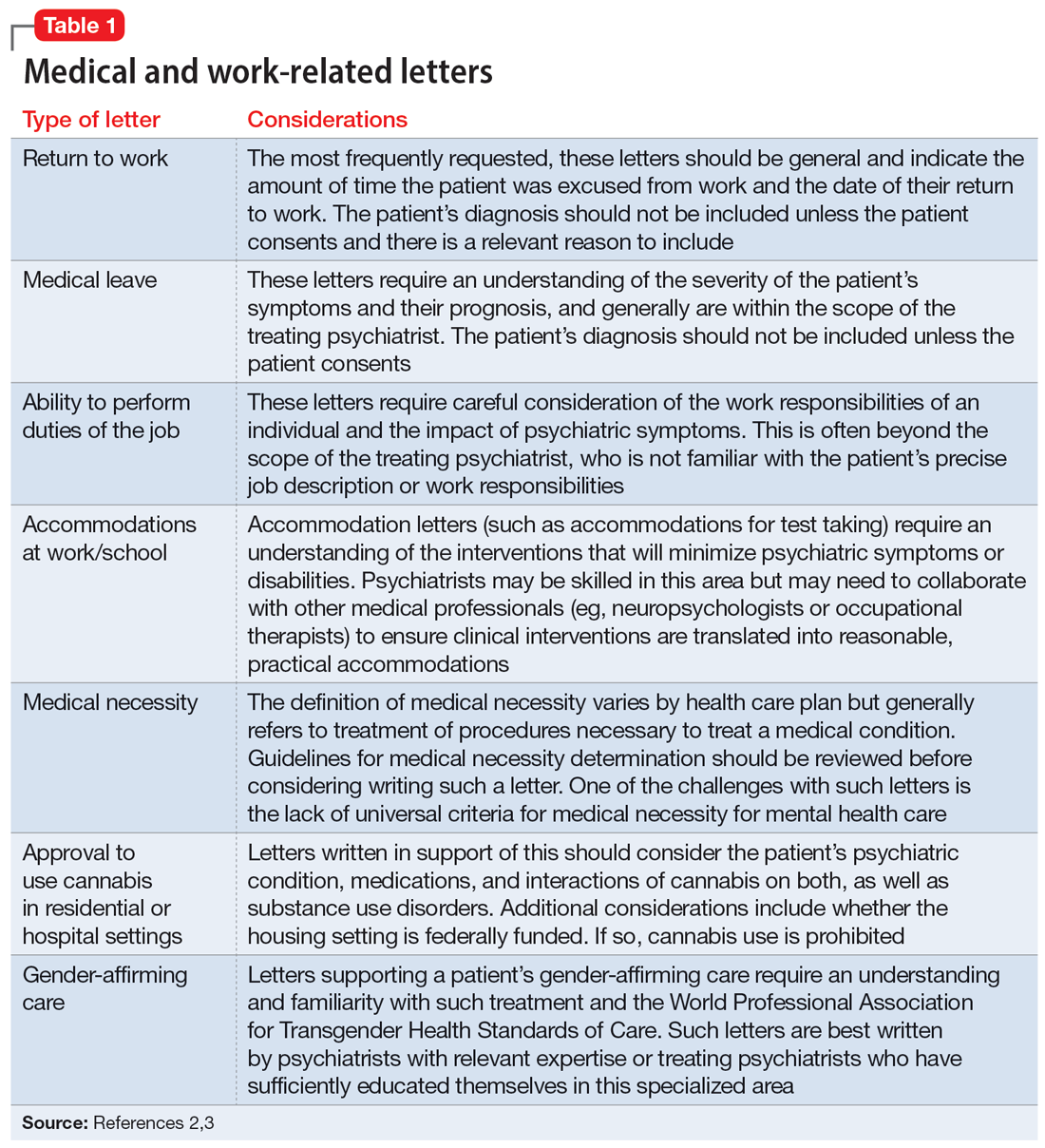

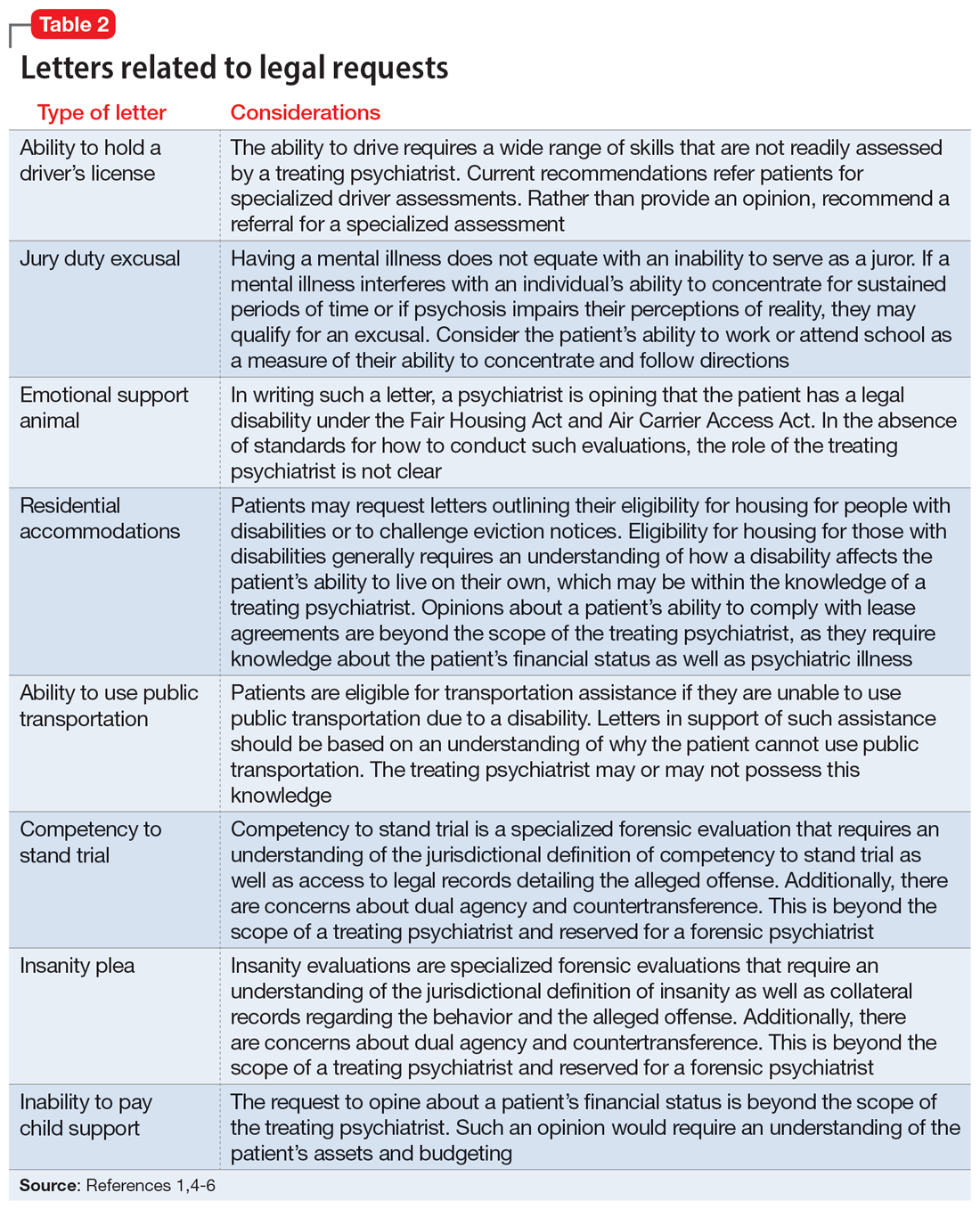

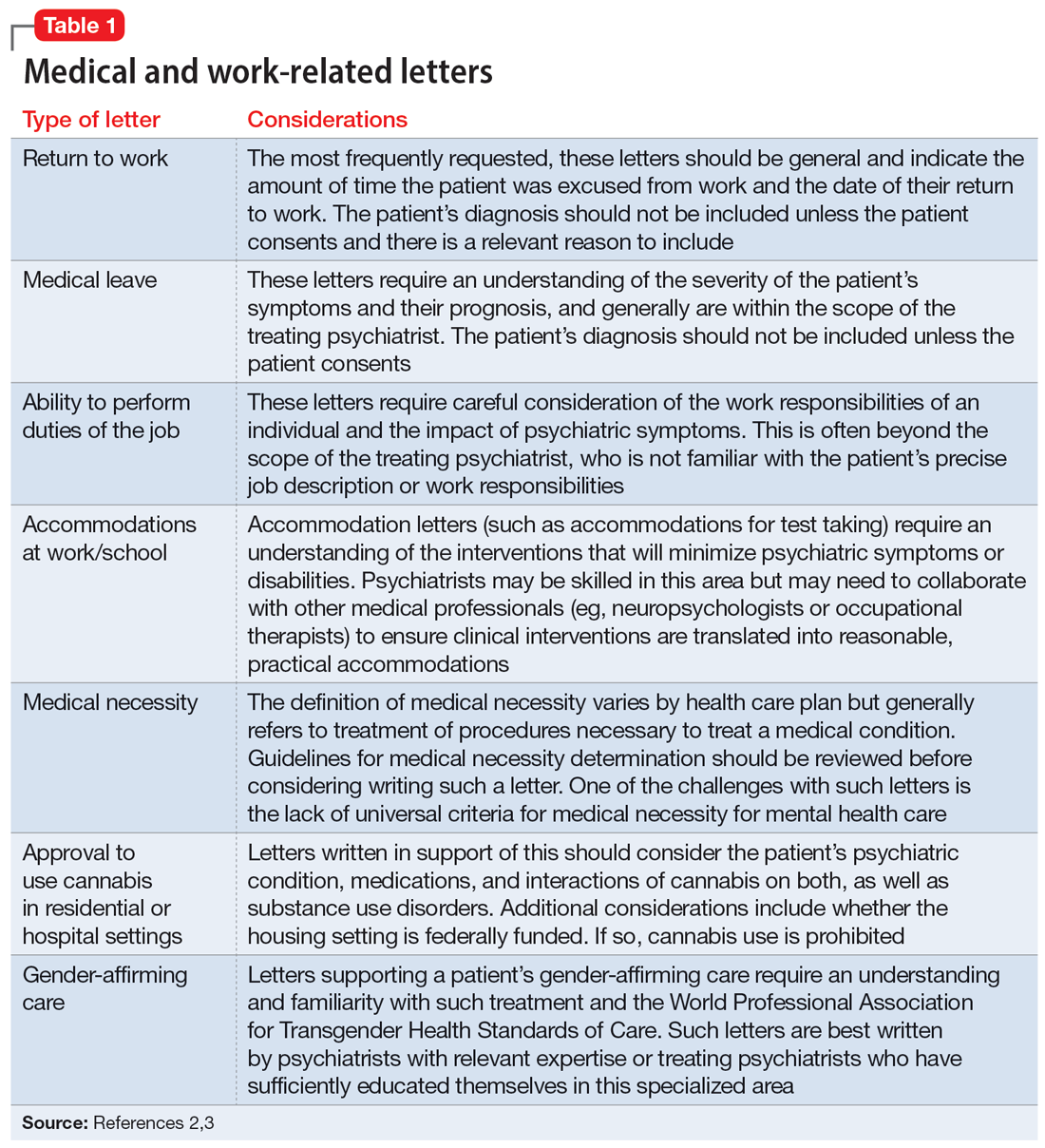

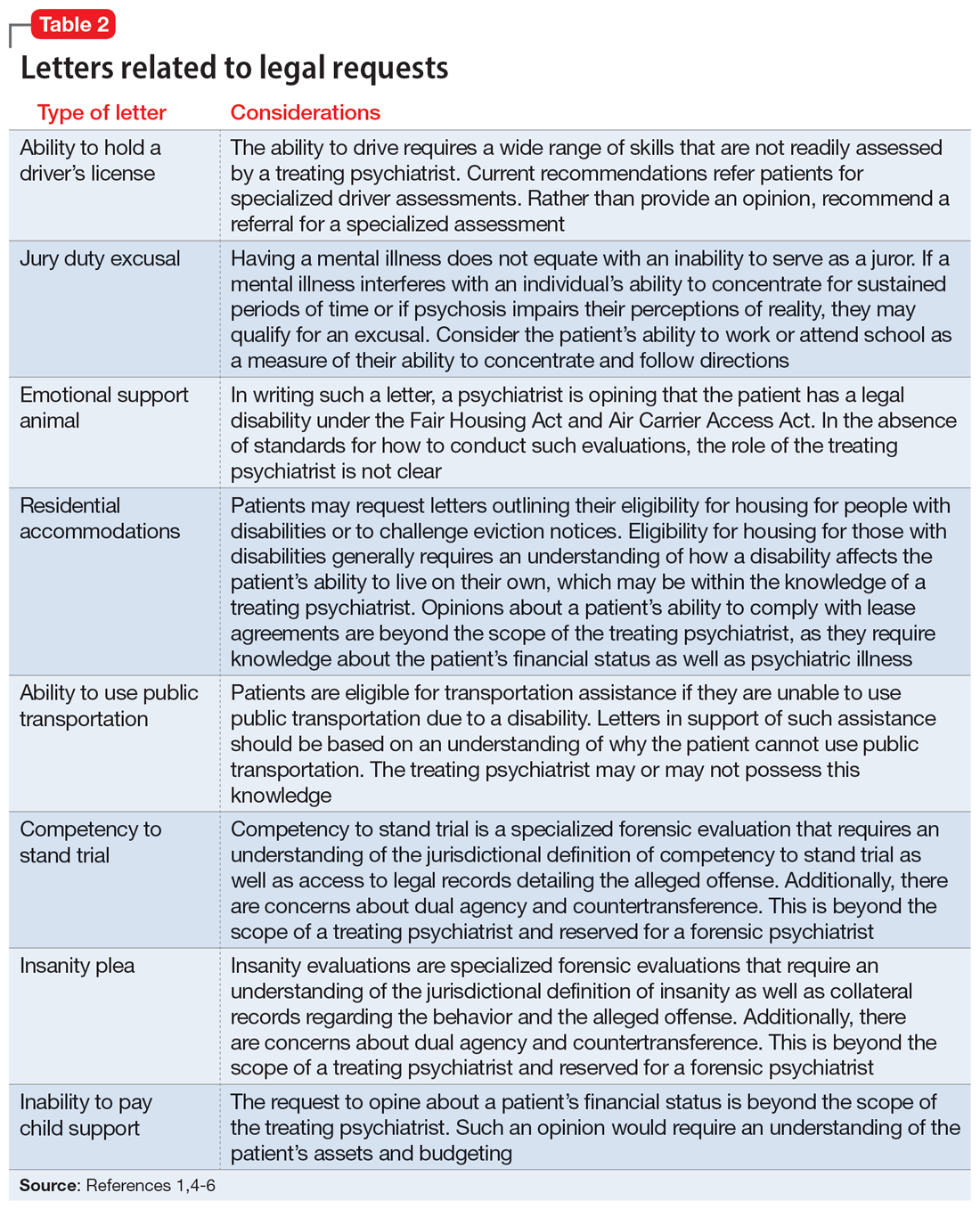

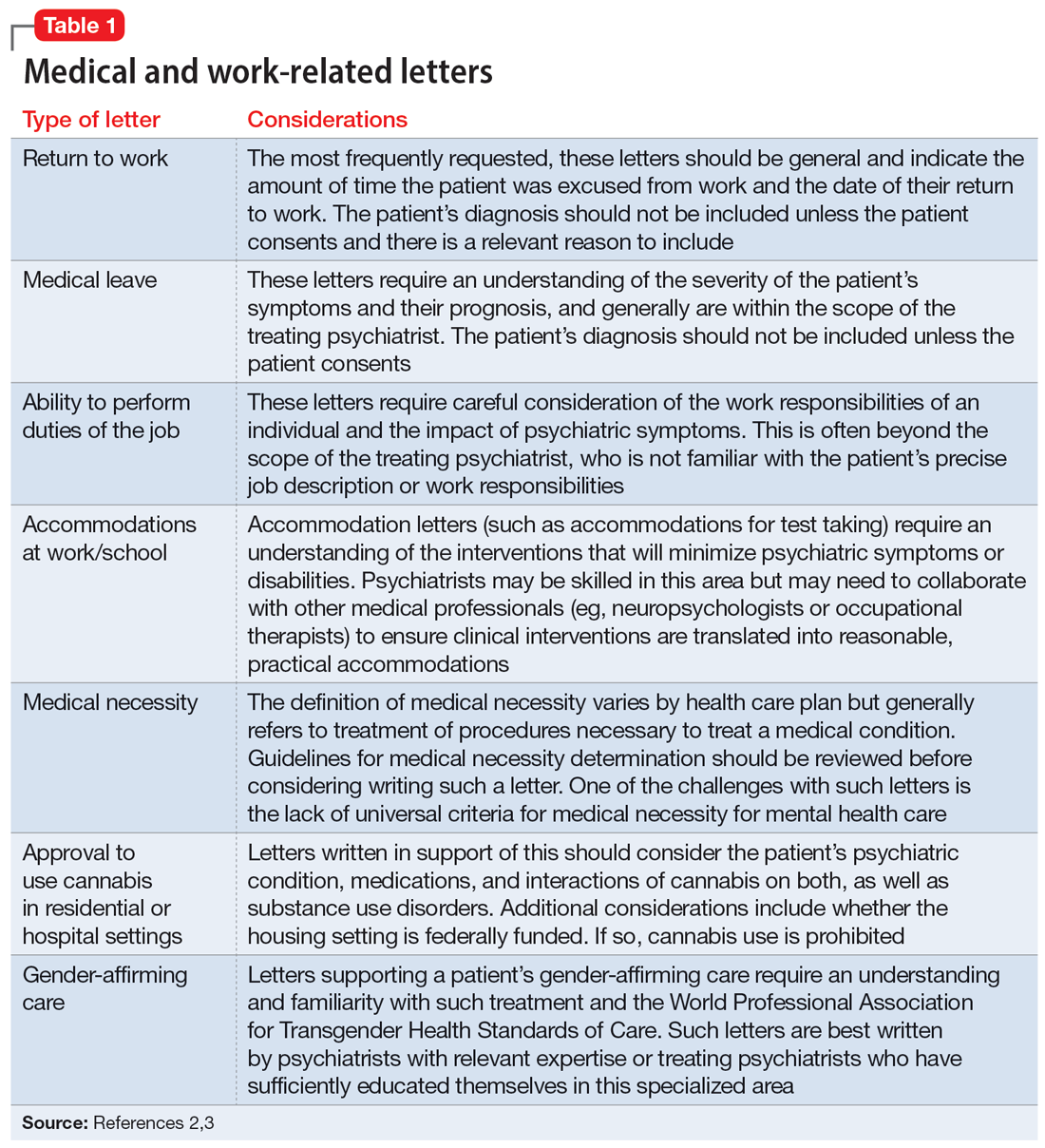

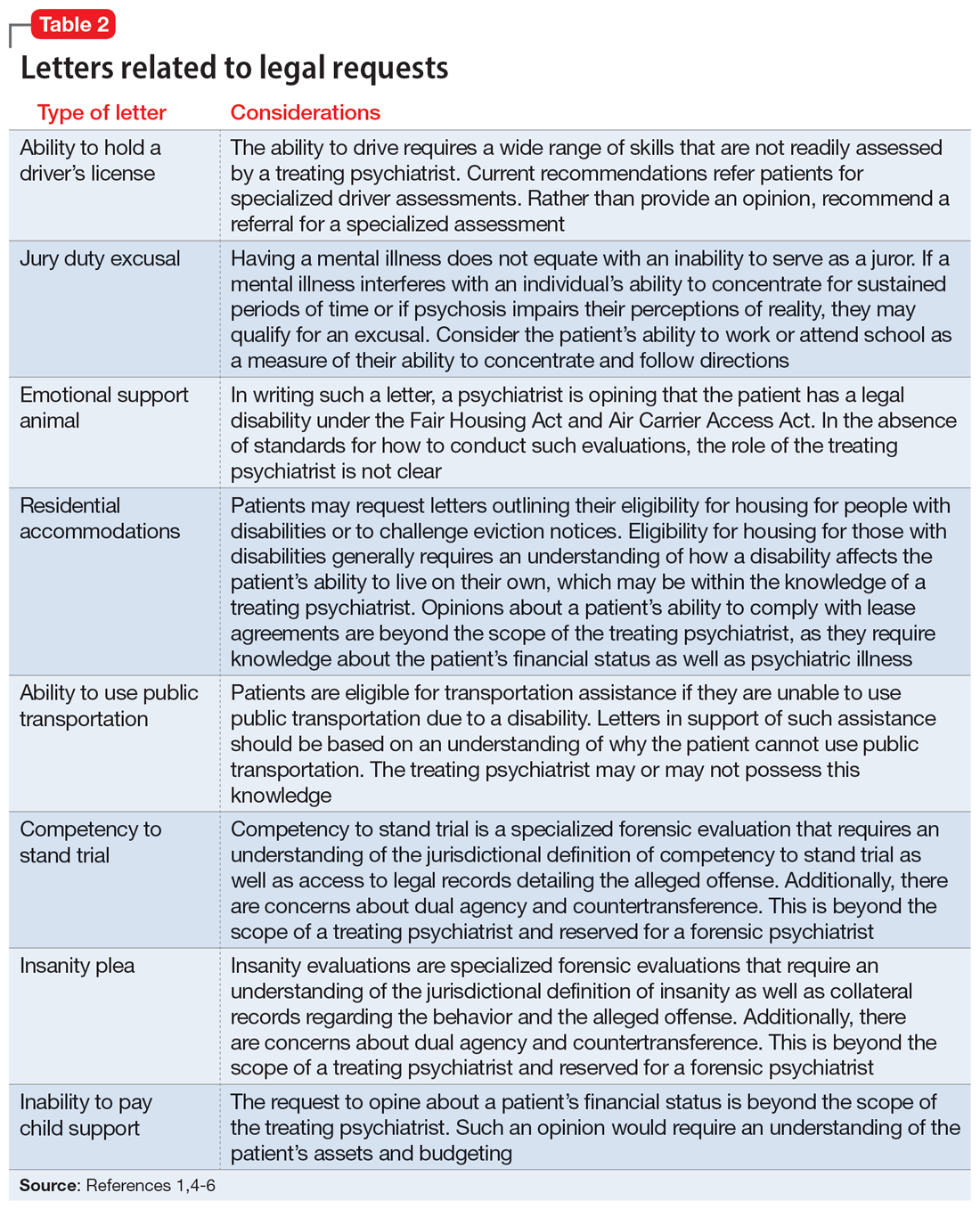

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

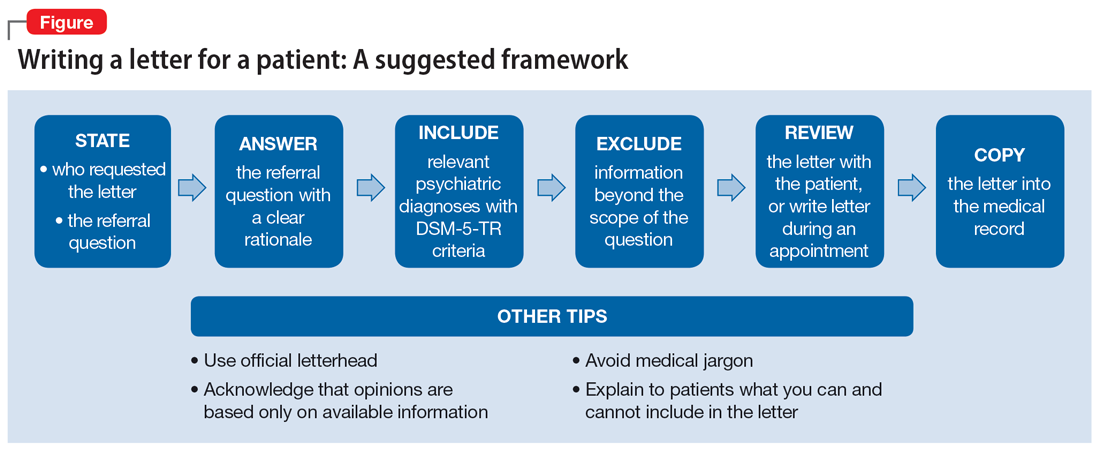

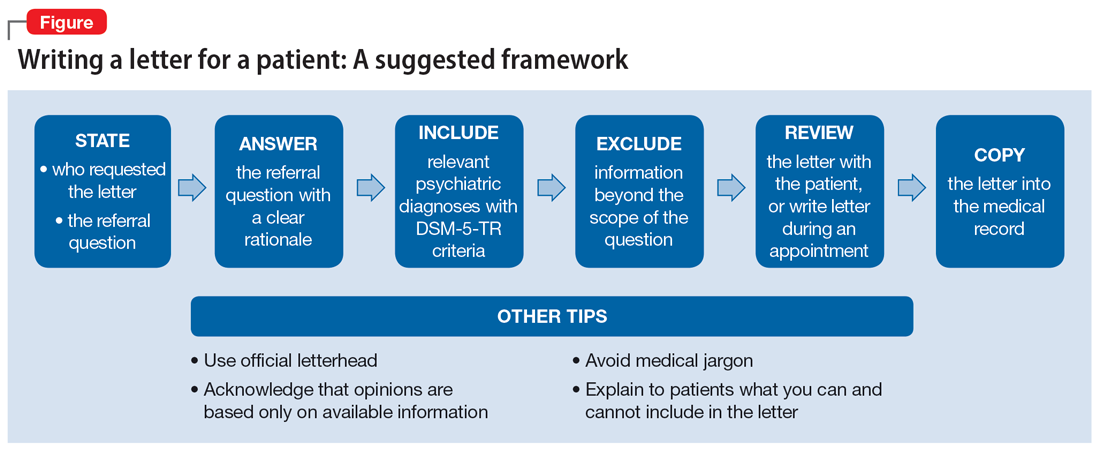

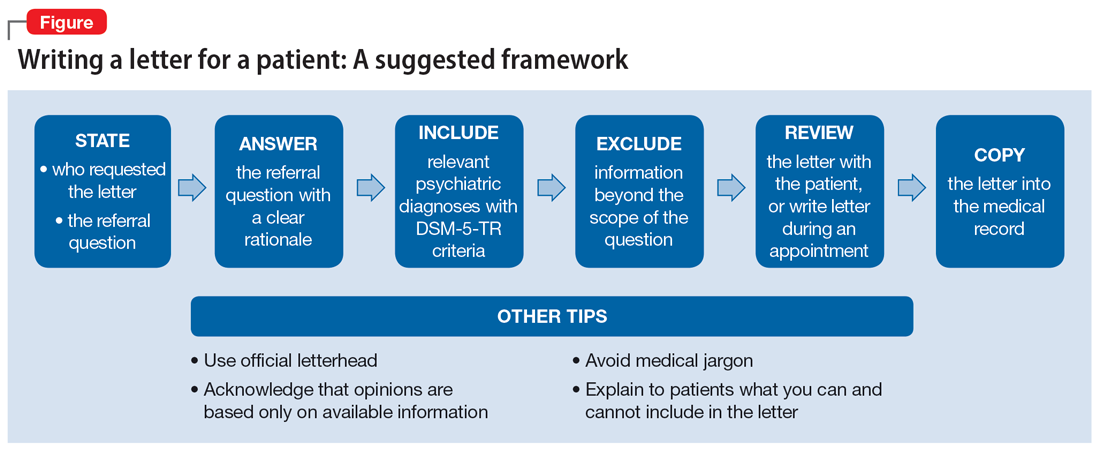

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x