User login

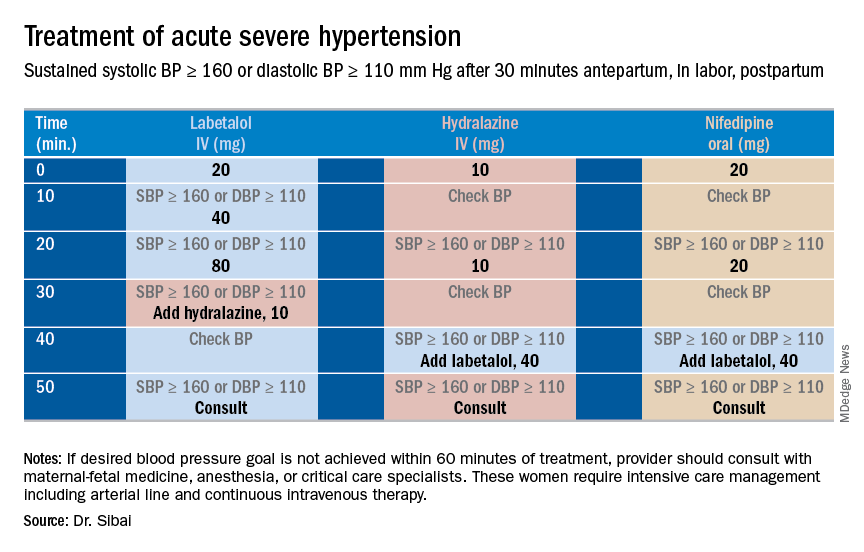

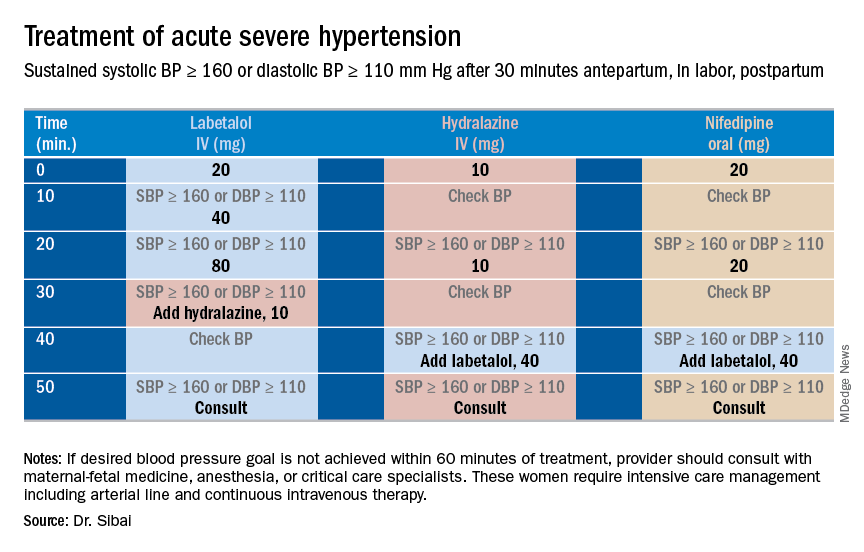

In the last installment of the Master Class, I addressed the importance of clarity in the classification of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and proposed several key diagnostic definitions. Here, I address the management of “mild” gestational hypertension (GHTN) and preeclampsia without severe features, which I believe should be managed similarly. I also address the management of preeclampsia with severe features, and I share an algorithm that I have developed and fine-tuned over the years to control acute severe hypertension with the use of intravenous labetalol, intravenous hydralazine, or oral nifedipine.

Management of “mild” gestational hypertension/Preeclampsia without severe features

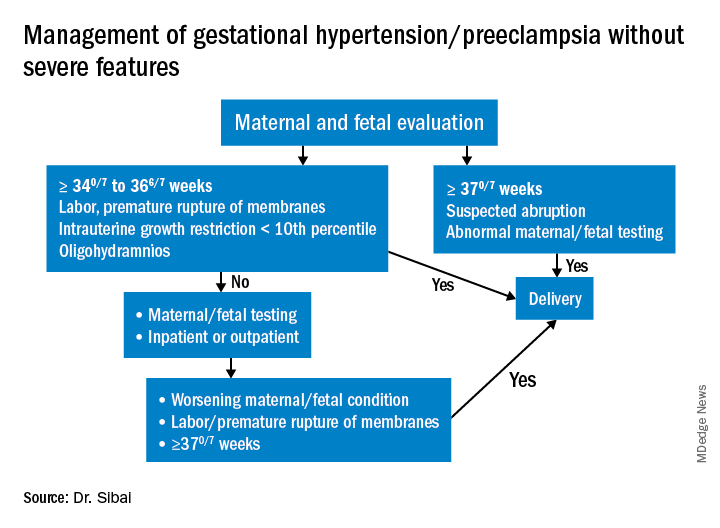

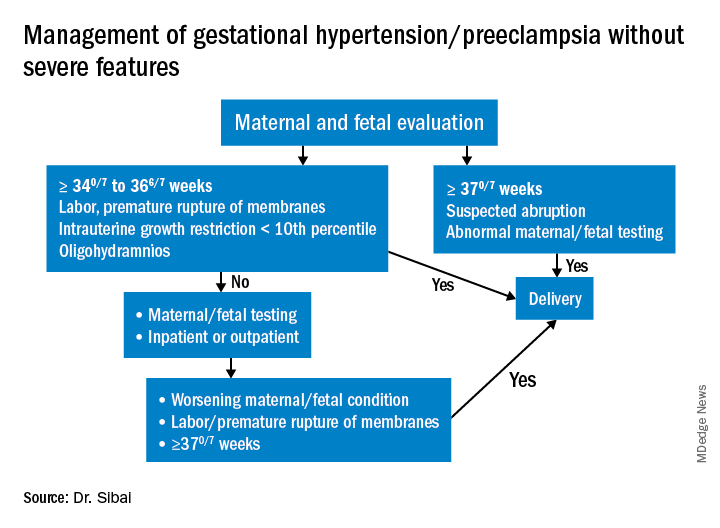

Mild gestational hypertension in and of itself has little effect on maternal or perinatal morbidity and mortality when it develops at or beyond 37 weeks’ gestation. However, approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with preterm GHTN will subsequently develop preeclampsia or progress to severe GHTN. In addition, these pregnancies may result in fetal growth restriction and placental abruption.

Antihypertensive drugs should not be used during ambulatory management of women with GHTN. Patients who receive antihypertensive therapy, including those diagnosed with severe GHTN, should be hospitalized and initially treated as having preeclampsia with or without severe features. Subsequent management will depend on initial response to therapy, blood pressure values after treatment, gestational age, and laboratory findings.

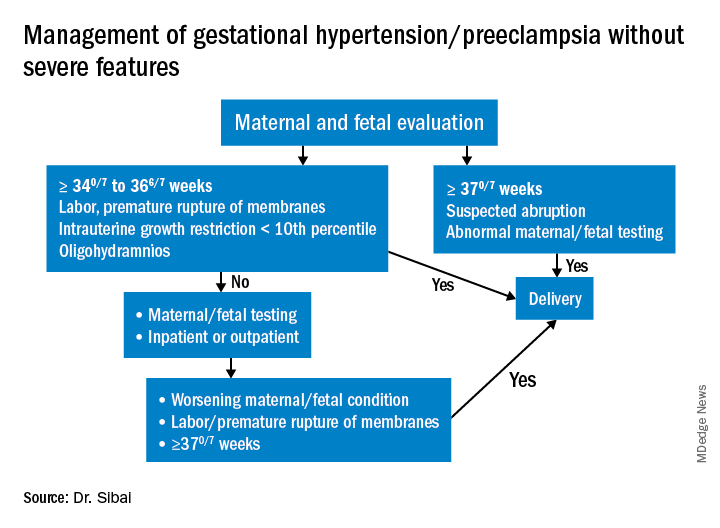

Preeclampsia without severe features is usually managed as in those with GHTN. (See related figure.)

Close surveillance is warranted, as either type may progress to fulminant disease. Maternal surveillance should include blood pressure measurements twice per week, and CBC, liver enzymes, and serum creatinine measurements once every week. Patients also should be instructed to immediately report any of these symptoms: Persistent severe headaches; right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting; scotomata, blurred vision, photophobia, or double vision; shortness of breath or orthopnea; altered mental changes; decreased fetal movement; rupture of membranes; vaginal bleeding; or regular uterine contractions.

Fetal evaluation for patients with GHTN/preeclampsia includes ultrasound at the time of diagnosis for evaluation of fetal growth and amniotic fluid value (deepest vertical pocket, or DVP) as well as fetal movement count and non-stress testing (NST). Subsequently, NST and DVP need to be checked twice per week. A decision for delivery will depend on gestational age, fetal status, and development of severe disease.

Management of preeclampsia with severe features

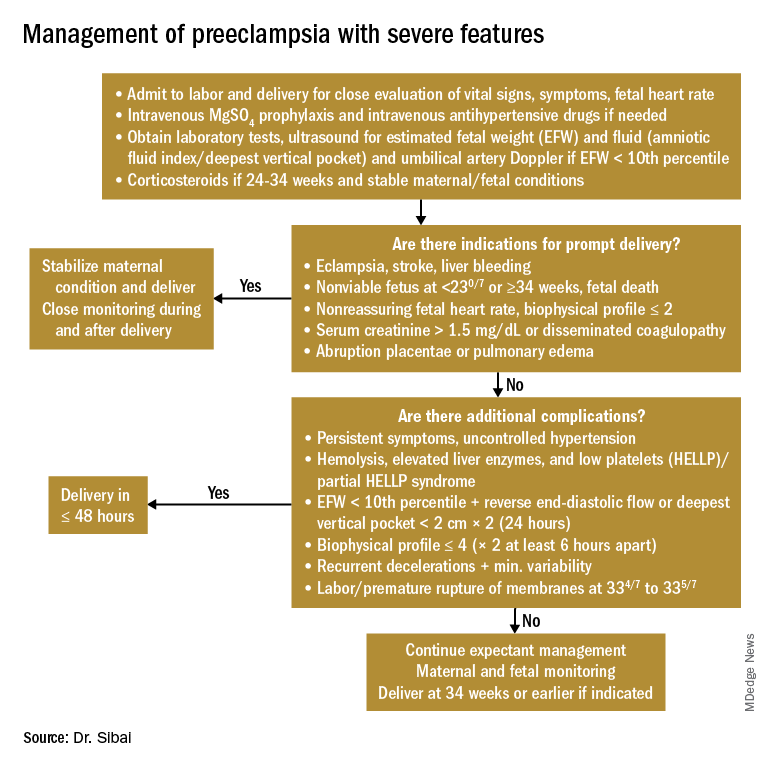

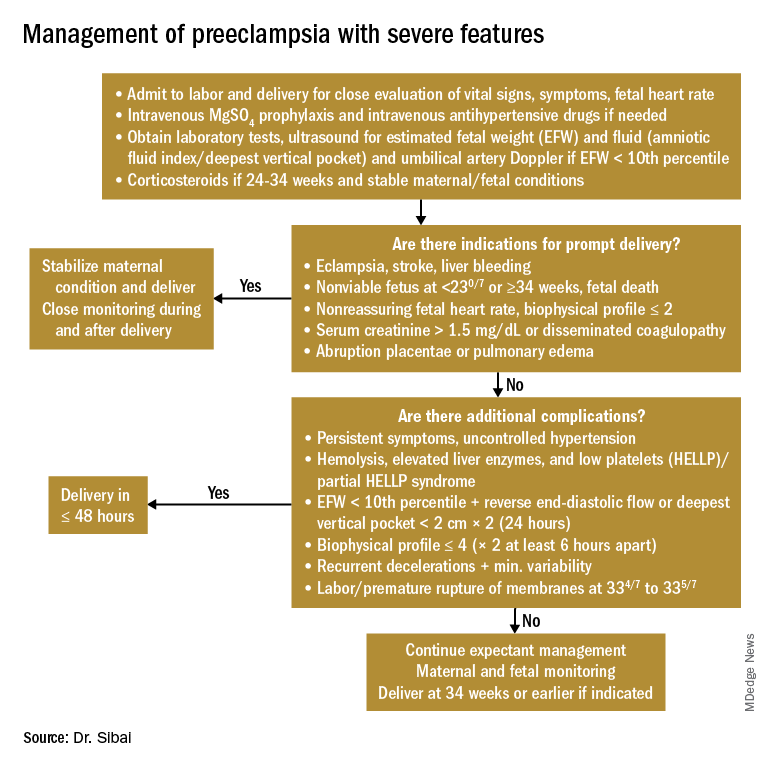

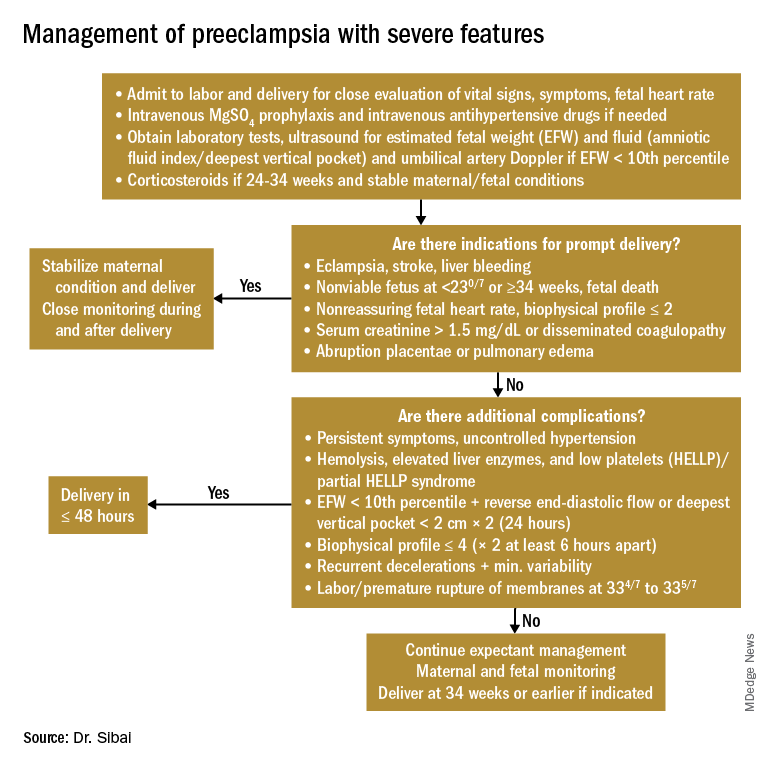

Any patient who has preeclampsia with severe features should be admitted and initially observed in a labor and delivery unit. (See related figure.)

Initial workup should include assessment for fetal well-being, monitoring of maternal blood pressure and symptomatology, and laboratory evaluation. Laboratory assessment should include hematocrit, platelet count, serum creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). An ultrasound for fetal growth and amniotic fluid index/DVP also should be obtained. Candidates for expectant management should be carefully selected, counseled regarding its risks and benefits, and managed only at tertiary care hospitals.

Fetal well-being should be assessed on a daily basis by NST and on a weekly basis with amniotic fluid/DVP determination. An ultrasound for fetal growth should be performed every 2-3 weeks. Maternal laboratory evaluation should be done daily or every other day. If the patient maintains a stable maternal and fetal course, she may be expectantly managed until 34 weeks. Worsening maternal or fetal status warrants delivery, regardless of gestational age.

Maternal blood pressure (BP) control is essential with expectant management or during delivery. Medications can be given orally or intravenously, as necessary, to maintain a systolic BP of 140-150 mm Hg and a diastolic BP of 90-100 mm Hg. The most commonly used intravenous medications for this purpose are labetalol and hydralazine. Other medications can include oral rapid-acting nifedipine. Subsequent management can include oral medications such as labetalol and long-acting nifedipine. Care should be taken not to drop the blood pressure too rapidly to avoid reduced renal and placental perfusion.

A trial of labor is indicated in patients with severe preeclampsia if gestational age is greater than 30 weeks and/or if cervical Bishop Score is greater than or equal to 6. However, an appropriate time frame should be established regarding achievement of active labor.

Patients should be closely monitored for at least 24 hours post partum. Post partum eclampsia occurs in 30% of patients; thus, women who are receiving magnesium sulfate should continue it for 24 hours after delivery. In addition, women with preeclampsia who are receiving magnesium sulfate are at risk for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and should be managed accordingly.

Some patients with severe preeclampsia also are at risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension 3-5 days post partum. Therefore, all patients should receive frequent monitoring of intake and output.

Control of acute severe hypertension antepartum, in labor, or post partum

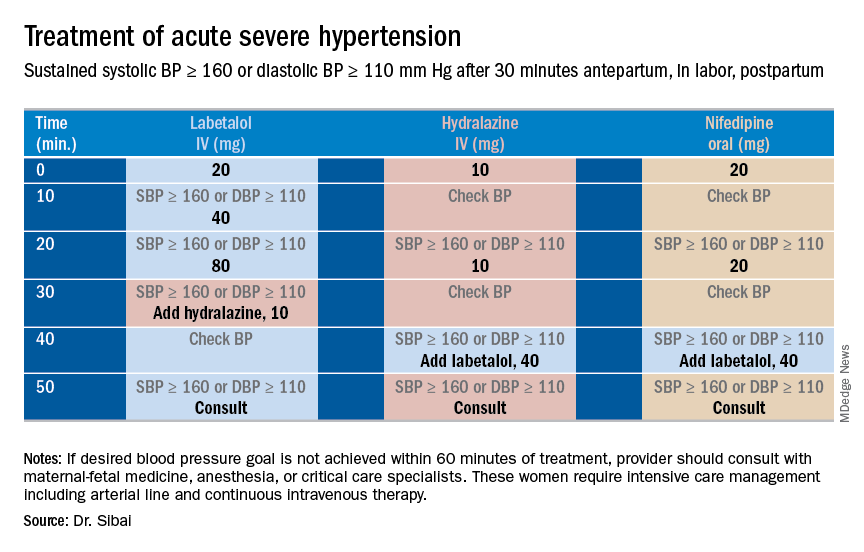

Uncontrolled severe hypertension for several hours may be associated with stroke and pulmonary edema. Therefore, several guidelines recommend initiation of antihypertensive medications for acute lowering of maternal blood pressure within 30-60 minutes. Several antihypertensive agents are available for the control of sustained severe hypertension before, during, and after delivery. It is important to be familiar with the maternal and fetal side effects, as well as mode of action of each agent, to select the best one. Antihypertensive agents can exert an effect by decreasing cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, and central blood pressure, or by inhibiting angiotensin production. Indications for therapy and commonly used drugs in pregnancy are listed in the accompanying table.

Several trials have compared the efficacy and side effects of intravenous bolus injections of hydralazine to either IV labetalol or oral rapid-acting nifedipine as well as oral nifedipine to IV labetalol. The results of these studies suggest that any of these three medications can be used to treat severe hypertension in pregnancy as long as the physician is familiar with the doses to be used, the expected onset of action, and potential side effects.

Because both hydralazine and nifedipine are associated with tachycardia, it is recommended that these agents not be used in patients with a heart rate above 105-110 beats per minute (bpm). It also is important to be attentive to patients with generalized swelling and/or hemoconcentration (hematocrit great than or equal to 40%), as these patients usually have marked reduction in plasma volume and can develop an excessive hypotensive response, with secondary reduction in tissue perfusion and uteroplacental blood flow, when treated with a combination of rapid-acting vasodilators (hydralazine or nifedipine). Such patients may require a bolus infusion of 250-500 mL of isotonic saline prior to the administration of vasodilators. In these patients, labetalol may be the appropriate drug to use.

Labetalol should be avoided in patients with bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm), in those with moderate to severe asthma, and in those with heart failure. In these patients, either hydralazine or nifedipine is the drug of choice. If an intravenous access is not available or difficult to obtain, oral nifedipine should be the drug of choice. In addition, because nifedipine is associated with improved renal blood flow with resultant increase in urine output, it is the drug of choice for treatment in those with decreased urine output, and for treatment of severe hypertension in the postpartum period.

In a third and final installment, I will elaborate on the postpartum management of women who have experienced hypertension with or without associated symptoms. Recently, postpartum hypertension has become a major cause of hospital readmission, as well as severe maternal morbidity and mortality.

Dr. Sibai is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston.

In the last installment of the Master Class, I addressed the importance of clarity in the classification of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and proposed several key diagnostic definitions. Here, I address the management of “mild” gestational hypertension (GHTN) and preeclampsia without severe features, which I believe should be managed similarly. I also address the management of preeclampsia with severe features, and I share an algorithm that I have developed and fine-tuned over the years to control acute severe hypertension with the use of intravenous labetalol, intravenous hydralazine, or oral nifedipine.

Management of “mild” gestational hypertension/Preeclampsia without severe features

Mild gestational hypertension in and of itself has little effect on maternal or perinatal morbidity and mortality when it develops at or beyond 37 weeks’ gestation. However, approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with preterm GHTN will subsequently develop preeclampsia or progress to severe GHTN. In addition, these pregnancies may result in fetal growth restriction and placental abruption.

Antihypertensive drugs should not be used during ambulatory management of women with GHTN. Patients who receive antihypertensive therapy, including those diagnosed with severe GHTN, should be hospitalized and initially treated as having preeclampsia with or without severe features. Subsequent management will depend on initial response to therapy, blood pressure values after treatment, gestational age, and laboratory findings.

Preeclampsia without severe features is usually managed as in those with GHTN. (See related figure.)

Close surveillance is warranted, as either type may progress to fulminant disease. Maternal surveillance should include blood pressure measurements twice per week, and CBC, liver enzymes, and serum creatinine measurements once every week. Patients also should be instructed to immediately report any of these symptoms: Persistent severe headaches; right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting; scotomata, blurred vision, photophobia, or double vision; shortness of breath or orthopnea; altered mental changes; decreased fetal movement; rupture of membranes; vaginal bleeding; or regular uterine contractions.

Fetal evaluation for patients with GHTN/preeclampsia includes ultrasound at the time of diagnosis for evaluation of fetal growth and amniotic fluid value (deepest vertical pocket, or DVP) as well as fetal movement count and non-stress testing (NST). Subsequently, NST and DVP need to be checked twice per week. A decision for delivery will depend on gestational age, fetal status, and development of severe disease.

Management of preeclampsia with severe features

Any patient who has preeclampsia with severe features should be admitted and initially observed in a labor and delivery unit. (See related figure.)

Initial workup should include assessment for fetal well-being, monitoring of maternal blood pressure and symptomatology, and laboratory evaluation. Laboratory assessment should include hematocrit, platelet count, serum creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). An ultrasound for fetal growth and amniotic fluid index/DVP also should be obtained. Candidates for expectant management should be carefully selected, counseled regarding its risks and benefits, and managed only at tertiary care hospitals.

Fetal well-being should be assessed on a daily basis by NST and on a weekly basis with amniotic fluid/DVP determination. An ultrasound for fetal growth should be performed every 2-3 weeks. Maternal laboratory evaluation should be done daily or every other day. If the patient maintains a stable maternal and fetal course, she may be expectantly managed until 34 weeks. Worsening maternal or fetal status warrants delivery, regardless of gestational age.

Maternal blood pressure (BP) control is essential with expectant management or during delivery. Medications can be given orally or intravenously, as necessary, to maintain a systolic BP of 140-150 mm Hg and a diastolic BP of 90-100 mm Hg. The most commonly used intravenous medications for this purpose are labetalol and hydralazine. Other medications can include oral rapid-acting nifedipine. Subsequent management can include oral medications such as labetalol and long-acting nifedipine. Care should be taken not to drop the blood pressure too rapidly to avoid reduced renal and placental perfusion.

A trial of labor is indicated in patients with severe preeclampsia if gestational age is greater than 30 weeks and/or if cervical Bishop Score is greater than or equal to 6. However, an appropriate time frame should be established regarding achievement of active labor.

Patients should be closely monitored for at least 24 hours post partum. Post partum eclampsia occurs in 30% of patients; thus, women who are receiving magnesium sulfate should continue it for 24 hours after delivery. In addition, women with preeclampsia who are receiving magnesium sulfate are at risk for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and should be managed accordingly.

Some patients with severe preeclampsia also are at risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension 3-5 days post partum. Therefore, all patients should receive frequent monitoring of intake and output.

Control of acute severe hypertension antepartum, in labor, or post partum

Uncontrolled severe hypertension for several hours may be associated with stroke and pulmonary edema. Therefore, several guidelines recommend initiation of antihypertensive medications for acute lowering of maternal blood pressure within 30-60 minutes. Several antihypertensive agents are available for the control of sustained severe hypertension before, during, and after delivery. It is important to be familiar with the maternal and fetal side effects, as well as mode of action of each agent, to select the best one. Antihypertensive agents can exert an effect by decreasing cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, and central blood pressure, or by inhibiting angiotensin production. Indications for therapy and commonly used drugs in pregnancy are listed in the accompanying table.

Several trials have compared the efficacy and side effects of intravenous bolus injections of hydralazine to either IV labetalol or oral rapid-acting nifedipine as well as oral nifedipine to IV labetalol. The results of these studies suggest that any of these three medications can be used to treat severe hypertension in pregnancy as long as the physician is familiar with the doses to be used, the expected onset of action, and potential side effects.

Because both hydralazine and nifedipine are associated with tachycardia, it is recommended that these agents not be used in patients with a heart rate above 105-110 beats per minute (bpm). It also is important to be attentive to patients with generalized swelling and/or hemoconcentration (hematocrit great than or equal to 40%), as these patients usually have marked reduction in plasma volume and can develop an excessive hypotensive response, with secondary reduction in tissue perfusion and uteroplacental blood flow, when treated with a combination of rapid-acting vasodilators (hydralazine or nifedipine). Such patients may require a bolus infusion of 250-500 mL of isotonic saline prior to the administration of vasodilators. In these patients, labetalol may be the appropriate drug to use.

Labetalol should be avoided in patients with bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm), in those with moderate to severe asthma, and in those with heart failure. In these patients, either hydralazine or nifedipine is the drug of choice. If an intravenous access is not available or difficult to obtain, oral nifedipine should be the drug of choice. In addition, because nifedipine is associated with improved renal blood flow with resultant increase in urine output, it is the drug of choice for treatment in those with decreased urine output, and for treatment of severe hypertension in the postpartum period.

In a third and final installment, I will elaborate on the postpartum management of women who have experienced hypertension with or without associated symptoms. Recently, postpartum hypertension has become a major cause of hospital readmission, as well as severe maternal morbidity and mortality.

Dr. Sibai is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston.

In the last installment of the Master Class, I addressed the importance of clarity in the classification of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and proposed several key diagnostic definitions. Here, I address the management of “mild” gestational hypertension (GHTN) and preeclampsia without severe features, which I believe should be managed similarly. I also address the management of preeclampsia with severe features, and I share an algorithm that I have developed and fine-tuned over the years to control acute severe hypertension with the use of intravenous labetalol, intravenous hydralazine, or oral nifedipine.

Management of “mild” gestational hypertension/Preeclampsia without severe features

Mild gestational hypertension in and of itself has little effect on maternal or perinatal morbidity and mortality when it develops at or beyond 37 weeks’ gestation. However, approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with preterm GHTN will subsequently develop preeclampsia or progress to severe GHTN. In addition, these pregnancies may result in fetal growth restriction and placental abruption.

Antihypertensive drugs should not be used during ambulatory management of women with GHTN. Patients who receive antihypertensive therapy, including those diagnosed with severe GHTN, should be hospitalized and initially treated as having preeclampsia with or without severe features. Subsequent management will depend on initial response to therapy, blood pressure values after treatment, gestational age, and laboratory findings.

Preeclampsia without severe features is usually managed as in those with GHTN. (See related figure.)

Close surveillance is warranted, as either type may progress to fulminant disease. Maternal surveillance should include blood pressure measurements twice per week, and CBC, liver enzymes, and serum creatinine measurements once every week. Patients also should be instructed to immediately report any of these symptoms: Persistent severe headaches; right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting; scotomata, blurred vision, photophobia, or double vision; shortness of breath or orthopnea; altered mental changes; decreased fetal movement; rupture of membranes; vaginal bleeding; or regular uterine contractions.

Fetal evaluation for patients with GHTN/preeclampsia includes ultrasound at the time of diagnosis for evaluation of fetal growth and amniotic fluid value (deepest vertical pocket, or DVP) as well as fetal movement count and non-stress testing (NST). Subsequently, NST and DVP need to be checked twice per week. A decision for delivery will depend on gestational age, fetal status, and development of severe disease.

Management of preeclampsia with severe features

Any patient who has preeclampsia with severe features should be admitted and initially observed in a labor and delivery unit. (See related figure.)

Initial workup should include assessment for fetal well-being, monitoring of maternal blood pressure and symptomatology, and laboratory evaluation. Laboratory assessment should include hematocrit, platelet count, serum creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). An ultrasound for fetal growth and amniotic fluid index/DVP also should be obtained. Candidates for expectant management should be carefully selected, counseled regarding its risks and benefits, and managed only at tertiary care hospitals.

Fetal well-being should be assessed on a daily basis by NST and on a weekly basis with amniotic fluid/DVP determination. An ultrasound for fetal growth should be performed every 2-3 weeks. Maternal laboratory evaluation should be done daily or every other day. If the patient maintains a stable maternal and fetal course, she may be expectantly managed until 34 weeks. Worsening maternal or fetal status warrants delivery, regardless of gestational age.

Maternal blood pressure (BP) control is essential with expectant management or during delivery. Medications can be given orally or intravenously, as necessary, to maintain a systolic BP of 140-150 mm Hg and a diastolic BP of 90-100 mm Hg. The most commonly used intravenous medications for this purpose are labetalol and hydralazine. Other medications can include oral rapid-acting nifedipine. Subsequent management can include oral medications such as labetalol and long-acting nifedipine. Care should be taken not to drop the blood pressure too rapidly to avoid reduced renal and placental perfusion.

A trial of labor is indicated in patients with severe preeclampsia if gestational age is greater than 30 weeks and/or if cervical Bishop Score is greater than or equal to 6. However, an appropriate time frame should be established regarding achievement of active labor.

Patients should be closely monitored for at least 24 hours post partum. Post partum eclampsia occurs in 30% of patients; thus, women who are receiving magnesium sulfate should continue it for 24 hours after delivery. In addition, women with preeclampsia who are receiving magnesium sulfate are at risk for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and should be managed accordingly.

Some patients with severe preeclampsia also are at risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension 3-5 days post partum. Therefore, all patients should receive frequent monitoring of intake and output.

Control of acute severe hypertension antepartum, in labor, or post partum

Uncontrolled severe hypertension for several hours may be associated with stroke and pulmonary edema. Therefore, several guidelines recommend initiation of antihypertensive medications for acute lowering of maternal blood pressure within 30-60 minutes. Several antihypertensive agents are available for the control of sustained severe hypertension before, during, and after delivery. It is important to be familiar with the maternal and fetal side effects, as well as mode of action of each agent, to select the best one. Antihypertensive agents can exert an effect by decreasing cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, and central blood pressure, or by inhibiting angiotensin production. Indications for therapy and commonly used drugs in pregnancy are listed in the accompanying table.

Several trials have compared the efficacy and side effects of intravenous bolus injections of hydralazine to either IV labetalol or oral rapid-acting nifedipine as well as oral nifedipine to IV labetalol. The results of these studies suggest that any of these three medications can be used to treat severe hypertension in pregnancy as long as the physician is familiar with the doses to be used, the expected onset of action, and potential side effects.

Because both hydralazine and nifedipine are associated with tachycardia, it is recommended that these agents not be used in patients with a heart rate above 105-110 beats per minute (bpm). It also is important to be attentive to patients with generalized swelling and/or hemoconcentration (hematocrit great than or equal to 40%), as these patients usually have marked reduction in plasma volume and can develop an excessive hypotensive response, with secondary reduction in tissue perfusion and uteroplacental blood flow, when treated with a combination of rapid-acting vasodilators (hydralazine or nifedipine). Such patients may require a bolus infusion of 250-500 mL of isotonic saline prior to the administration of vasodilators. In these patients, labetalol may be the appropriate drug to use.

Labetalol should be avoided in patients with bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm), in those with moderate to severe asthma, and in those with heart failure. In these patients, either hydralazine or nifedipine is the drug of choice. If an intravenous access is not available or difficult to obtain, oral nifedipine should be the drug of choice. In addition, because nifedipine is associated with improved renal blood flow with resultant increase in urine output, it is the drug of choice for treatment in those with decreased urine output, and for treatment of severe hypertension in the postpartum period.

In a third and final installment, I will elaborate on the postpartum management of women who have experienced hypertension with or without associated symptoms. Recently, postpartum hypertension has become a major cause of hospital readmission, as well as severe maternal morbidity and mortality.

Dr. Sibai is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston.