User login

First-episode psychosis (FEP) in schizophrenia is characterized by high response rates to antipsychotic therapy, followed by frequent antipsychotic discontinuation and elevated relapse rates soon after maintenance treatment begins.1,2 With subsequent episodes, time to response progressively increases and likelihood of response decreases.3,4

To address these issues, this article—the second of 2 parts5—describes the rationale and evidence for using nonstandard first-line antipsychotic therapies to manage FEP. Specifically, we discuss when clinicians might consider monotherapy exceeding FDA-approved maximum dosages, combination therapy, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIA), or clozapine.

Monotherapy beyond FDA-approved dosages

Treatment guidelines for FEP recommend oral antipsychotic dosages in the lower half of the treatment range and lower than those that are required for multi-episode schizophrenia.6-16 Ultimately, clinicians prescribe individualized dosages for their patients based on symptom improvement and tolerability. The optimal dosage at which to achieve a favorable D2 receptor occupancy likely will vary from patient to patient.17

To control symptoms, higher dosages may be needed than those used in FEP clinical trials, recommended by guidelines for FEP or multi-episode patients, or approved by the FDA. Patients seen in everyday practice may be more complicated (eg, have a comorbid condition or history of nonresponse) than study populations. Higher dosages also may be reasonable to overcome drug−drug interactions (eg, cigarette smoking-mediated cytochrome P450 1A2 induction, resulting in increased olanzapine metabolism),18 or to establish antipsychotic failure if adequate trials at lower dosages have resulted in a suboptimal response and the patient is not experiencing tolerability or safety concerns.

In a study of low-, full-, and high-dosage antipsychotic therapy in FEP, an additional 15% of patients responded to higher dosages of olanzapine and risperidone after failing to respond to a standard dosage.19 A study of data from the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode Project’s Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP) found that, of participants identified who may benefit from therapy modification, 8.8% were prescribed an antipsychotic (often, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol) at a higher-than-recommended dosage.20 Of note, only olanzapine was prescribed at higher than FDA-approved dosages.

Antipsychotic combination therapy

Prescribing combinations of antipsychotics—antipsychotic polypharmacy (APP)— has a negative connotation because of limited efficacy and safety data,21 and limited endorsement in schizophrenia treatment guidelines.9,13 Caution with APP is warranted; a complex medication regimen may increase the potential for adverse effects, poorer adherence, and adverse drug-drug interactions.9 APP has been shown to independently predict both shorter treatment duration and discontinuation before 1 year.22

Nonetheless, the clinician and patient may share the decision to implement APP and observe whether benefits outweigh risks in situations such as:

• to optimize neuroreceptor occupancy and targets (eg, attempting to achieve adequate D2 receptor blockade while minimizing side effects secondary to binding other receptors)

• to manage co-existing symptom domains (eg, mood changes, aggression, negative symptoms, disorganization, and cognitive deficits)

• to mitigate antipsychotic-induced side effects (eg, initiating aripiprazole to treat hyperprolactinemia induced by another antipsychotic to which the patient has achieved a favorable response).23

Clinicians report using APP to treat as many as 50% of patients with a history of multiple psychotic episodes.23 For FEP patients, 23% of participants in the RAISE-ETP trial who were identified as possibly benefiting from therapy modification were prescribed APP.20 Regrettably, researchers have not found evidence to support a reported rationale for using APP—that lower dosages of individual antipsychotics when used in combination may avoid high-dosage prescriptions.24

Before implementing APP, thoroughly explore and manage reasons for a patient’s suboptimal response to monotherapy.25 An adequate trial with any antipsychotic should be at the highest tolerated dosage for 12 to 16 weeks. Be mindful that response to an APP trial may be the result of additional time on the original antipsychotic.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in FEP

Guideline recommendations. Most older guidelines for schizophrenia treatment suggest LAIA after multiple relapses related to medication nonadherence or when a patient prefers injected medication (Table 1).6-13 Expert consensus guidelines also recommend considering LAIA in patients who lack insight into their illness. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines7 state LAIA can be considered for inadequate adherence at any stage, whereas the 2010 British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) guidelines9 express uncertainty about their use in FEP, because of limited evidence. Both the BAP and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines13 urge clinicians to consider LAIA when avoiding nonadherence is a treatment priority.

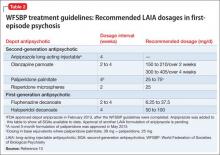

Recently, the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuro-psychopharmacology (AFPBN) created expert consensus guidelines12 on using LAIA in practice. They recommend long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) as first-line maintenance treatment for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and for individuals experiencing a first recurrent episode. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines contain LAIA dosage recommendations for FEP (Table 2).10

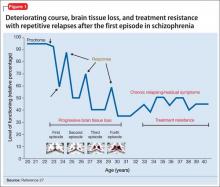

Advances have been made in understanding the serious neurobiological adverse effects of psychotic relapses, including neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, that may explain the atrophic changes observed with psychotic episodes starting with the FEP. Protecting the patient from a second episode has become a vital therapeutic management goal26 (Figure 127).

Concerns. Compared with oral antipsychotics, LAIA offers clinical advantages:

• improved pharmacokinetic profile (lower “peaks” and higher “valleys”)

• more consistent plasma concentrations (no variability related to administration timing or food effects)

• no first-pass metabolism, which can ease the process of finding the lowest effective and safe dosage

• reduced administration burden and objective tracking of adherence with typical dosing every 2 to 4 weeks

• less stigmatizing than oral medication for FEP patients, such as college students living in a dormitory.28,29

Barriers to LAIA use include:

• slow dosage titration and increased time to reach steady state drug level

• oral supplementation for some (eg, risperidone microspheres and aripiprazole long-acting injectable)

• logistical challenges for some (eg, 3-hour post-injection monitoring for delirium sedation syndrome with olanzapine pamoate)

• additional planning to coordinate care for scheduled injections

• higher expenses up front

• local injection site reactions

• dosage adjustment difficulties if adverse effects occur.28,29

Adoption rates of LAIA are low, especially for FEP.30 Most surveys indicate that (1) physicians believe LAIA treatment is ineffective for FEP31 and (2) patients do not prefer injectable to oral antipsychotics,32 despite evidence to the contrary.33,34 A survey of 198 psychiatrists identified 3 factors that influenced their decisions against using LAIA patients with FEP:

• limited availability of SGA depot formulations (4, to date, in the United States)

• frequent rejection by the patient when LAIA is offered without adequate explanation or encouragement

• skepticism of FEP patients (and their family) who lack experience with relapse.35

In reality, when SGA depots were introduced in the United Kingdom, prescribing rates of LAIA did not increase. As for patient rejection being a major reason for not prescribing LAIA, few patients (5% to 36%) are offered depot injections, particularly in FEP.29 Most patients using LAIA are chronic, multi-episode, violent people who are receiving medications involuntarily.29 Interestingly, this survey did not find 2 factors to be influential in psychiatrists’ decision not to use LAIA in FEP:

• guidelines do not explicitly recommend depot treatment in FEP

• treatment in FEP may be limited to 1 year, therefore depot administration is not worthwhile.35

Preliminary evidence. At least a dozen studies have explored LAIA treatment for FEP, with the use of fluphenazine decanoate,36 perphenazine enanthate37 (discontinued), and risperidone microspheres.37-48 The research demonstrates the efficacy and safety of LAIA in FEP as measured by these endpoints:

• improved symptom control38,40-43,46,48

• adherence43,44,48

• reduced relapse rates37,43 and rehospitalizations37,47

• lesser reductions in white matter brain volume45

• no differences in extrapyramidal side effects or prolactin-associated adverse effects.48

A few small studies demonstrate significant differences in outcomes between risperidone LAIA and oral comparator groups (Table 3).43-45 Ongoing studies of LAIA use in FEP are comparing paliperidone palmitate with risperidone microspheres and other oral antipsychotics.49-51 No studies are examining olanzapine pamoate in FEP, likely because several guidelines do not recommended its use. No studies have been published regarding aripiprazole long-acting injectable in FEP. This LAIA formulation was approved in February 2013, and robust studies of the oral formulation in FEP are limited.52

Discussion and recommendations. Psychiatrists relying on subjective measures of antipsychotic adherence may inaccurately assess whether patients meet this criterion for LAIA use.53 LAIA could combat the high relapse rate in FEP, yet depot antipsychotics are prescribed infrequently for FEP patients (eg, for only 9.5% of participants in the RAISE-ETP study).20 Most schizophrenia treatment guidelines do not discuss LAIA use specifically in FEP, although the AFPBN expert consensus guidelines published in 2013 do recommend SGA depot formulations in FEP.12 SGA LAIA may be preferable, given its neuroprotective effects, in contrast to the neurotoxicity concerns of FGA LAIA.54,55

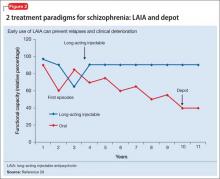

Relapses begin within a few months of illness stabilization after FEP, and >50% of patients relapse within 1 or 2 years2—the recommended minimum treatment duration for FEP.8,9,13 The use of LAIA is advisable in any patient with schizophrenia for whom long-term antipsychotic therapy is indicated.56 LAIA administration requirements objectively track medication adherence, which allows clinicians to be proactive in relapse prevention. Not using an intervention in FEP that improves adherence and decreases relapse rates contradicts our goal of instituting early, effective treatment to improve long-term functional outcomes (Figure 2).29

Considering clozapine in FEP

Guideline recommendations. Schizo-phrenia treatment guidelines and FDA labeling57 reserve clozapine for third-line treatment of refractory schizophrenia after 2 adequate antipsychotic trials have failed despite optimal dosing (Table 1).6-13 Some guidelines specify 1 of the 2 failed antipsychotic trials must include an SGA.6,7,10,11,13-16 Most say clozapine may be considered in patients with chronic aggression or hostility,7-9,14,16 or suicidal thoughts and behaviors.6-8,14,16 TMAP guidelines recommend a clozapine trial with concomitant substance abuse, persistent positive symptoms during 2 years of consistent medication treatment, and after 5 years of inadequate response (“treatment resistance”), regardless of the number of antipsychotic trials.7

Rationale and concerns. Clozapine is a superior choice for treatment-refractory delusions or hallucinations of schizophrenia, because it markedly enhances the response rate to antipsychotic therapy.58 Researchers therefore have investigated whether clozapine, compared with other antipsychotics, would yield more favorable initial and long-term outcomes when used first-line in FEP.

Preliminary evidence. Five studies have explored the use of clozapine as first-line therapy in FEP (Table 4).59-63 Interpreting the results is difficult because clozapine trials may be brief (mostly, 12 to 52 weeks); lack a comparator arm; suffer from a high attrition rate; enroll few patients; and lack potentially important outcome measures such as negative symptoms, suicidality, and functional assessment.

Overall, these studies demonstrate clozapine is as efficacious in this patient population as chlorpromazine (no difference in remission at 1-year, although clozapine-treated patients remitted faster and stayed in remission longer)60,61 or risperidone (no difference in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores).62

At present, clozapine has not been shown superior to other antipsychotics as a first-line treatment for FEP. Research does underscore the importance of a clozapine trial as third-line treatment for FEP patients who have not responded well to 2 SGA trials.63 Many of these nonresponders (77%) have demonstrated a favorable response when promptly switched to clozapine.64

Discussion and recommendations. The limited evidence argues against using clozapine earlier than as third-line treatment in FEP. Perhaps the high treatment response that characterizes FEP creates a ceiling effect that obscures differences in antipsychotic efficacy at this stage.65 Clozapine use as first-line treatment should be re-evaluated with more robust methodology. One approach could be to assess its benefit in FEP by the duration of untreated psychosis.

The odds of achieving remission have been shown to decrease by 15% for each year that psychosis has not been treated.59 Studies exploring the use of clozapine as a second-line agent for FEP also are warranted, as antipsychotic response during subsequent trials is substantially reduced. In fact, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidelines recommend this as an area for future research.11

For now, clozapine should continue to be reserved as second- or third-line treatment in a patient with FEP. The risks of clozapine’s potentially serious adverse effects (eg, agranulocytosis, seizures, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, myocarditis, pancreatitis, hypotension, sialorrhea, severe sedation, ileus) can be justified only in the treatment of severe and persistent psychotic symptoms.57

Bottom Line

Nonstandard use of antipsychotic monotherapy dosages beyond the approved FDA limit and combination antipsychotic therapy may be reasonable for select first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients. Strongly consider long-acting injectable antipsychotics in FEP to proactively combat the high relapse rate and more easily identify antipsychotic failure. Continue to use clozapine as second- or third-line therapy in FEP: Studies have not found that it is more efficacious than other antipsychotics for first-line use.

Related Resource

• Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project Early Treatment Program. National Institute of Mental Health. http://raiseetp.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify, Abilify Maintena

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluphenazine decanoate • Prolixin-D

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol decanoate • Haldol-D

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine pamoate • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone microspheres • Risperdal Consta

Disclosures

Dr. Gardner reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Nasrallah is a consultant to Acadia, Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Sunovion, and is a speaker for Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, and Sunovion.

1. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

2. Bradford DW, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. Pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia and related nonaffective psychoses. Drugs. 2003;63(21):2265-2283.

3. Lieberman JA, Koreen AR, Chakos M, et al. Factors influencing treatment response and outcome of first-episode schizophrenia: implications for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(suppl 9):5-9.

4. Agid O, Arenovich T, Sajeev G, et al. An algorithm-based approach to first-episode schizophrenia: response rates over 3 prospective antipsychotic trials with a retrospective data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1439-1444.

5. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis. An early stage of schizophrenia with distinct treatment needs. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):32-34,36-40,42.

6. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

7. Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Procedural Manual. Schizophrenia Treatment Algorithms. http://www.jpshealthnet.org/sites/default/files/ tmapalgorithmforschizophrenia.pdf. Updated April 2008. Accessed June 11, 2015.

8. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71-93.

9. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620.

10. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrok T, et al; WFSBP Task force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(1):2-44.

11. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 131: Management of schizophrenia. http://www.sign.ac.uk/ pdf/sign131.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed June 11, 2015.

12. Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serous mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE clinical guideline 178: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. https://www.nice.org. uk/guidance/cg178/resources/guidance-psychosis-and-schizophrenia-in-adults-treatment-and-management-pdf. Updated March 2014. Accessed June 16, 2015.

14. Canadian Psychiatric Association. Clinical practice guidelines. Treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(13 suppl 1):7S-57S.

15. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 11):3-80.

16. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. The Mount Sinai conference on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):5-16.

17. Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, et al. Relationship between dopamine D(2) occupancy, clinical response, and side effects: a double-blind PET study of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):514-520.

18. Fankhauser MP. Drug interactions with tobacco smoke: implications for patient care. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):12-16.

19. Agid O, Schulze L, Arenovich T, et al. Antipsychotic response in first-episode schizophrenia: efficacy of high doses and switching. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):1017-1022.

20. Robinson DG, Schooler NR, John M, et al. Prescription practices in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: data from the national RAISE-ETP study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(3):237-248.

21. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

22. Fisher MD, Reilly K, Isenberg K, et al. Antipsychotic patterns of use in patients with schizophrenia: polypharmacy versus monotherapy. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):341.

23. Barnes TR, Paton C. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia: benefits and risks. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(5):383-399.

24. John AP, Dragovic M. Antipsychotic polypharmacy is not associated with reduced dose of individual antipsychotics in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(2):193-195.

25. Nasrallah HA. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/specialty-focus/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/article/ treatment-resistant-schizophrenia/9be7bba3713d4a4cd68aa 8c92b79e5b1.html. Accessed June 16, 2015.

26. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

27. Nasrallah HA, Smeltzer DJ. Contemporary diagnosis and management of the patient with schizophrenia. 2nd ed. Newton, PA: Handbooks in Health Care Co; 2011.

28. McEvoy JP. Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 5):15-18.

29. Agid O, Foussias G, Remington G. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: their role in relapse prevention. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(14):2301-2317.

30. Kirschner M, Theodoridou A, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ attitude towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in subjects with a first episode psychosis. Ther Adv Psychophamacol. 2013;3(2):89-99.

31. Heres S, Hamann J, Mendel R, et al. Identifying the profile of optimal candidates for antipsychotic depot therapy: A cluster analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(8):1987-1993.

32. Heres S, Lambert M, Vauth R. Treatment of early episode in patents with schizophrenia: the role of long acting antipsychotics. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(suppl 2):1409-1413.

33. Heres S, Schmitz FS, Leucht S, et al. The attitude of patients towards antipsychotic depot treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(5):275-282.

34. Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, Weedon JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of long-acting injectable risperidone vs continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia patients: initial adherence outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1397-1406.

35. Heres S, Reichhart T, Hamann J, et al. Psychiatrists’ attitude to antipsychotic depot treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(5):297-301.

36. Kane JM, Rifkin A, Quitkin F, et al. Fluphenazine vs placebo in patients with remitted, acute first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(1):70-73.

37. Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K, Lönnqvist J, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of patients in a community care after first hospitalization due to schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: observational follow-up study. BMJ. 2006;333(7561):224.

38. Parellada E, Andrezina R, Milanova V, et al. Patients in the early phases of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders effectively treated with risperidone long-acting injectable. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(suppl 5):5-14.

39. Malla A, Binder C, Chue P. Comparison of long-acting injectable risperidone and oral novel antipsychotic drugs for treatment in early phase of schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Convention Society of Biological Psychiatry; Toronto, Canada; 2006.

40. Lasser RA, Bossie CA, Zhu Y, et al. Long-acting risperidone in young adults with early schizophrenia or schizoaffective illness. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):65-71.

41. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

42. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Oral versus injectable antipsychotic treatment in early psychosis: post hoc comparison of two studies. Clin Ther. 2008;30(12):2378-2386.

43. Kim B, Lee SH, Choi TK, et al. Effectiveness of risperidone long-acting injection in first-episode schizophrenia: in naturalistic setting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(5):1231-1235.

44. Weiden PJ, Schooler NJ, Weedon JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of long-acting injectable risperidone vs continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia patients: initial adherence outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1397-1406.

45. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Amar CP, et al. Long acting injection versus oral risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia: differential impact on white matter myelination trajectory. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(1):35-41.

46. Napryeyenko O, Burba B, Martinez G, et al. Risperidone long-acting injectable in recent-onset schizophrenia examined with clinician and patient self-report measures. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(2):200-202.

47. Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):603-609.

48. Dubois V, Megens J, Mertens C, et al. Long-acting risperidone in early-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Belgica. 2011;111(1):9-21.

49. ClinicalTrials.gov. Oral risperidone versus injectable paliperidone palmitate for treating first-episode schizophrenia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT01451736. Accessed June 16, 2015.

50. ClinicalTrials.gov. Brain myelination effects of paliperidone palmitate versus oral risperidone in first episode schizophrenia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/ show/NCT01458379. Accessed June 16, 2015.

51. ClinicalTrials.gov. Effects of paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics on clinical outcomes and MRI measures. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01359293. Accessed June 16, 2016.

52. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA. http:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda. Accessed January 11, 2015.

53. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46; quiz 47-48.

54. Nandra KS, Agius M. The difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics: the effects on neurogenesis. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(suppl 1):S95-S99.

55. Nasrallah HA. Haloperidol is clearly neurotoxic. Should it be banned? Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):7-8.

56. Kane JM, Garcia-Ribora C. Clinical guideline recommendations for antipsychotic long-acting injections. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;52:S63-S67.

57. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2014.

58. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):789-796.

59. Woerner MG, Robinson DG, Alvir JMJ, et al. Clozapine as a first treatment for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1514-1516.

60. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):995-1003.

61. Girgis RR, Phillips MR, Li X, et al. Clozapine v. chlorpromazine in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: 9-year outcomes of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):281-288.

62. Sanz-Fuentenebro J, Taboada D, Palomo T, et al. Randomized trial of clozapine vs. risperidone in treatment-naïve first-episode schizophrenia: results after one year. Schizophr Res. 2013;149(1-3):156-161.

63. Yang PD, Ji Z. The efficacy and related factors of clozapine on first-episode schizophrenia. Chin J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;23:155-158.

64. Agid O, Schulze L, Arenovich T, et al. Antipsychotic response in first-episode schizophrenia: efficacy of high doses and switching. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):1017-1022.

65. Remington G, Agid O, Foussias G, et al. Clozapine’s role in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):146-151.

First-episode psychosis (FEP) in schizophrenia is characterized by high response rates to antipsychotic therapy, followed by frequent antipsychotic discontinuation and elevated relapse rates soon after maintenance treatment begins.1,2 With subsequent episodes, time to response progressively increases and likelihood of response decreases.3,4

To address these issues, this article—the second of 2 parts5—describes the rationale and evidence for using nonstandard first-line antipsychotic therapies to manage FEP. Specifically, we discuss when clinicians might consider monotherapy exceeding FDA-approved maximum dosages, combination therapy, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIA), or clozapine.

Monotherapy beyond FDA-approved dosages

Treatment guidelines for FEP recommend oral antipsychotic dosages in the lower half of the treatment range and lower than those that are required for multi-episode schizophrenia.6-16 Ultimately, clinicians prescribe individualized dosages for their patients based on symptom improvement and tolerability. The optimal dosage at which to achieve a favorable D2 receptor occupancy likely will vary from patient to patient.17

To control symptoms, higher dosages may be needed than those used in FEP clinical trials, recommended by guidelines for FEP or multi-episode patients, or approved by the FDA. Patients seen in everyday practice may be more complicated (eg, have a comorbid condition or history of nonresponse) than study populations. Higher dosages also may be reasonable to overcome drug−drug interactions (eg, cigarette smoking-mediated cytochrome P450 1A2 induction, resulting in increased olanzapine metabolism),18 or to establish antipsychotic failure if adequate trials at lower dosages have resulted in a suboptimal response and the patient is not experiencing tolerability or safety concerns.

In a study of low-, full-, and high-dosage antipsychotic therapy in FEP, an additional 15% of patients responded to higher dosages of olanzapine and risperidone after failing to respond to a standard dosage.19 A study of data from the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode Project’s Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP) found that, of participants identified who may benefit from therapy modification, 8.8% were prescribed an antipsychotic (often, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol) at a higher-than-recommended dosage.20 Of note, only olanzapine was prescribed at higher than FDA-approved dosages.

Antipsychotic combination therapy

Prescribing combinations of antipsychotics—antipsychotic polypharmacy (APP)— has a negative connotation because of limited efficacy and safety data,21 and limited endorsement in schizophrenia treatment guidelines.9,13 Caution with APP is warranted; a complex medication regimen may increase the potential for adverse effects, poorer adherence, and adverse drug-drug interactions.9 APP has been shown to independently predict both shorter treatment duration and discontinuation before 1 year.22

Nonetheless, the clinician and patient may share the decision to implement APP and observe whether benefits outweigh risks in situations such as:

• to optimize neuroreceptor occupancy and targets (eg, attempting to achieve adequate D2 receptor blockade while minimizing side effects secondary to binding other receptors)

• to manage co-existing symptom domains (eg, mood changes, aggression, negative symptoms, disorganization, and cognitive deficits)

• to mitigate antipsychotic-induced side effects (eg, initiating aripiprazole to treat hyperprolactinemia induced by another antipsychotic to which the patient has achieved a favorable response).23

Clinicians report using APP to treat as many as 50% of patients with a history of multiple psychotic episodes.23 For FEP patients, 23% of participants in the RAISE-ETP trial who were identified as possibly benefiting from therapy modification were prescribed APP.20 Regrettably, researchers have not found evidence to support a reported rationale for using APP—that lower dosages of individual antipsychotics when used in combination may avoid high-dosage prescriptions.24

Before implementing APP, thoroughly explore and manage reasons for a patient’s suboptimal response to monotherapy.25 An adequate trial with any antipsychotic should be at the highest tolerated dosage for 12 to 16 weeks. Be mindful that response to an APP trial may be the result of additional time on the original antipsychotic.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in FEP

Guideline recommendations. Most older guidelines for schizophrenia treatment suggest LAIA after multiple relapses related to medication nonadherence or when a patient prefers injected medication (Table 1).6-13 Expert consensus guidelines also recommend considering LAIA in patients who lack insight into their illness. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines7 state LAIA can be considered for inadequate adherence at any stage, whereas the 2010 British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) guidelines9 express uncertainty about their use in FEP, because of limited evidence. Both the BAP and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines13 urge clinicians to consider LAIA when avoiding nonadherence is a treatment priority.

Recently, the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuro-psychopharmacology (AFPBN) created expert consensus guidelines12 on using LAIA in practice. They recommend long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) as first-line maintenance treatment for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and for individuals experiencing a first recurrent episode. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines contain LAIA dosage recommendations for FEP (Table 2).10

Advances have been made in understanding the serious neurobiological adverse effects of psychotic relapses, including neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, that may explain the atrophic changes observed with psychotic episodes starting with the FEP. Protecting the patient from a second episode has become a vital therapeutic management goal26 (Figure 127).

Concerns. Compared with oral antipsychotics, LAIA offers clinical advantages:

• improved pharmacokinetic profile (lower “peaks” and higher “valleys”)

• more consistent plasma concentrations (no variability related to administration timing or food effects)

• no first-pass metabolism, which can ease the process of finding the lowest effective and safe dosage

• reduced administration burden and objective tracking of adherence with typical dosing every 2 to 4 weeks

• less stigmatizing than oral medication for FEP patients, such as college students living in a dormitory.28,29

Barriers to LAIA use include:

• slow dosage titration and increased time to reach steady state drug level

• oral supplementation for some (eg, risperidone microspheres and aripiprazole long-acting injectable)

• logistical challenges for some (eg, 3-hour post-injection monitoring for delirium sedation syndrome with olanzapine pamoate)

• additional planning to coordinate care for scheduled injections

• higher expenses up front

• local injection site reactions

• dosage adjustment difficulties if adverse effects occur.28,29

Adoption rates of LAIA are low, especially for FEP.30 Most surveys indicate that (1) physicians believe LAIA treatment is ineffective for FEP31 and (2) patients do not prefer injectable to oral antipsychotics,32 despite evidence to the contrary.33,34 A survey of 198 psychiatrists identified 3 factors that influenced their decisions against using LAIA patients with FEP:

• limited availability of SGA depot formulations (4, to date, in the United States)

• frequent rejection by the patient when LAIA is offered without adequate explanation or encouragement

• skepticism of FEP patients (and their family) who lack experience with relapse.35

In reality, when SGA depots were introduced in the United Kingdom, prescribing rates of LAIA did not increase. As for patient rejection being a major reason for not prescribing LAIA, few patients (5% to 36%) are offered depot injections, particularly in FEP.29 Most patients using LAIA are chronic, multi-episode, violent people who are receiving medications involuntarily.29 Interestingly, this survey did not find 2 factors to be influential in psychiatrists’ decision not to use LAIA in FEP:

• guidelines do not explicitly recommend depot treatment in FEP

• treatment in FEP may be limited to 1 year, therefore depot administration is not worthwhile.35

Preliminary evidence. At least a dozen studies have explored LAIA treatment for FEP, with the use of fluphenazine decanoate,36 perphenazine enanthate37 (discontinued), and risperidone microspheres.37-48 The research demonstrates the efficacy and safety of LAIA in FEP as measured by these endpoints:

• improved symptom control38,40-43,46,48

• adherence43,44,48

• reduced relapse rates37,43 and rehospitalizations37,47

• lesser reductions in white matter brain volume45

• no differences in extrapyramidal side effects or prolactin-associated adverse effects.48

A few small studies demonstrate significant differences in outcomes between risperidone LAIA and oral comparator groups (Table 3).43-45 Ongoing studies of LAIA use in FEP are comparing paliperidone palmitate with risperidone microspheres and other oral antipsychotics.49-51 No studies are examining olanzapine pamoate in FEP, likely because several guidelines do not recommended its use. No studies have been published regarding aripiprazole long-acting injectable in FEP. This LAIA formulation was approved in February 2013, and robust studies of the oral formulation in FEP are limited.52

Discussion and recommendations. Psychiatrists relying on subjective measures of antipsychotic adherence may inaccurately assess whether patients meet this criterion for LAIA use.53 LAIA could combat the high relapse rate in FEP, yet depot antipsychotics are prescribed infrequently for FEP patients (eg, for only 9.5% of participants in the RAISE-ETP study).20 Most schizophrenia treatment guidelines do not discuss LAIA use specifically in FEP, although the AFPBN expert consensus guidelines published in 2013 do recommend SGA depot formulations in FEP.12 SGA LAIA may be preferable, given its neuroprotective effects, in contrast to the neurotoxicity concerns of FGA LAIA.54,55

Relapses begin within a few months of illness stabilization after FEP, and >50% of patients relapse within 1 or 2 years2—the recommended minimum treatment duration for FEP.8,9,13 The use of LAIA is advisable in any patient with schizophrenia for whom long-term antipsychotic therapy is indicated.56 LAIA administration requirements objectively track medication adherence, which allows clinicians to be proactive in relapse prevention. Not using an intervention in FEP that improves adherence and decreases relapse rates contradicts our goal of instituting early, effective treatment to improve long-term functional outcomes (Figure 2).29

Considering clozapine in FEP

Guideline recommendations. Schizo-phrenia treatment guidelines and FDA labeling57 reserve clozapine for third-line treatment of refractory schizophrenia after 2 adequate antipsychotic trials have failed despite optimal dosing (Table 1).6-13 Some guidelines specify 1 of the 2 failed antipsychotic trials must include an SGA.6,7,10,11,13-16 Most say clozapine may be considered in patients with chronic aggression or hostility,7-9,14,16 or suicidal thoughts and behaviors.6-8,14,16 TMAP guidelines recommend a clozapine trial with concomitant substance abuse, persistent positive symptoms during 2 years of consistent medication treatment, and after 5 years of inadequate response (“treatment resistance”), regardless of the number of antipsychotic trials.7

Rationale and concerns. Clozapine is a superior choice for treatment-refractory delusions or hallucinations of schizophrenia, because it markedly enhances the response rate to antipsychotic therapy.58 Researchers therefore have investigated whether clozapine, compared with other antipsychotics, would yield more favorable initial and long-term outcomes when used first-line in FEP.

Preliminary evidence. Five studies have explored the use of clozapine as first-line therapy in FEP (Table 4).59-63 Interpreting the results is difficult because clozapine trials may be brief (mostly, 12 to 52 weeks); lack a comparator arm; suffer from a high attrition rate; enroll few patients; and lack potentially important outcome measures such as negative symptoms, suicidality, and functional assessment.

Overall, these studies demonstrate clozapine is as efficacious in this patient population as chlorpromazine (no difference in remission at 1-year, although clozapine-treated patients remitted faster and stayed in remission longer)60,61 or risperidone (no difference in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores).62

At present, clozapine has not been shown superior to other antipsychotics as a first-line treatment for FEP. Research does underscore the importance of a clozapine trial as third-line treatment for FEP patients who have not responded well to 2 SGA trials.63 Many of these nonresponders (77%) have demonstrated a favorable response when promptly switched to clozapine.64

Discussion and recommendations. The limited evidence argues against using clozapine earlier than as third-line treatment in FEP. Perhaps the high treatment response that characterizes FEP creates a ceiling effect that obscures differences in antipsychotic efficacy at this stage.65 Clozapine use as first-line treatment should be re-evaluated with more robust methodology. One approach could be to assess its benefit in FEP by the duration of untreated psychosis.

The odds of achieving remission have been shown to decrease by 15% for each year that psychosis has not been treated.59 Studies exploring the use of clozapine as a second-line agent for FEP also are warranted, as antipsychotic response during subsequent trials is substantially reduced. In fact, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidelines recommend this as an area for future research.11

For now, clozapine should continue to be reserved as second- or third-line treatment in a patient with FEP. The risks of clozapine’s potentially serious adverse effects (eg, agranulocytosis, seizures, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, myocarditis, pancreatitis, hypotension, sialorrhea, severe sedation, ileus) can be justified only in the treatment of severe and persistent psychotic symptoms.57

Bottom Line

Nonstandard use of antipsychotic monotherapy dosages beyond the approved FDA limit and combination antipsychotic therapy may be reasonable for select first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients. Strongly consider long-acting injectable antipsychotics in FEP to proactively combat the high relapse rate and more easily identify antipsychotic failure. Continue to use clozapine as second- or third-line therapy in FEP: Studies have not found that it is more efficacious than other antipsychotics for first-line use.

Related Resource

• Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project Early Treatment Program. National Institute of Mental Health. http://raiseetp.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify, Abilify Maintena

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluphenazine decanoate • Prolixin-D

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol decanoate • Haldol-D

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine pamoate • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone microspheres • Risperdal Consta

Disclosures

Dr. Gardner reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Nasrallah is a consultant to Acadia, Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Sunovion, and is a speaker for Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, and Sunovion.

First-episode psychosis (FEP) in schizophrenia is characterized by high response rates to antipsychotic therapy, followed by frequent antipsychotic discontinuation and elevated relapse rates soon after maintenance treatment begins.1,2 With subsequent episodes, time to response progressively increases and likelihood of response decreases.3,4

To address these issues, this article—the second of 2 parts5—describes the rationale and evidence for using nonstandard first-line antipsychotic therapies to manage FEP. Specifically, we discuss when clinicians might consider monotherapy exceeding FDA-approved maximum dosages, combination therapy, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIA), or clozapine.

Monotherapy beyond FDA-approved dosages

Treatment guidelines for FEP recommend oral antipsychotic dosages in the lower half of the treatment range and lower than those that are required for multi-episode schizophrenia.6-16 Ultimately, clinicians prescribe individualized dosages for their patients based on symptom improvement and tolerability. The optimal dosage at which to achieve a favorable D2 receptor occupancy likely will vary from patient to patient.17

To control symptoms, higher dosages may be needed than those used in FEP clinical trials, recommended by guidelines for FEP or multi-episode patients, or approved by the FDA. Patients seen in everyday practice may be more complicated (eg, have a comorbid condition or history of nonresponse) than study populations. Higher dosages also may be reasonable to overcome drug−drug interactions (eg, cigarette smoking-mediated cytochrome P450 1A2 induction, resulting in increased olanzapine metabolism),18 or to establish antipsychotic failure if adequate trials at lower dosages have resulted in a suboptimal response and the patient is not experiencing tolerability or safety concerns.

In a study of low-, full-, and high-dosage antipsychotic therapy in FEP, an additional 15% of patients responded to higher dosages of olanzapine and risperidone after failing to respond to a standard dosage.19 A study of data from the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode Project’s Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP) found that, of participants identified who may benefit from therapy modification, 8.8% were prescribed an antipsychotic (often, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol) at a higher-than-recommended dosage.20 Of note, only olanzapine was prescribed at higher than FDA-approved dosages.

Antipsychotic combination therapy

Prescribing combinations of antipsychotics—antipsychotic polypharmacy (APP)— has a negative connotation because of limited efficacy and safety data,21 and limited endorsement in schizophrenia treatment guidelines.9,13 Caution with APP is warranted; a complex medication regimen may increase the potential for adverse effects, poorer adherence, and adverse drug-drug interactions.9 APP has been shown to independently predict both shorter treatment duration and discontinuation before 1 year.22

Nonetheless, the clinician and patient may share the decision to implement APP and observe whether benefits outweigh risks in situations such as:

• to optimize neuroreceptor occupancy and targets (eg, attempting to achieve adequate D2 receptor blockade while minimizing side effects secondary to binding other receptors)

• to manage co-existing symptom domains (eg, mood changes, aggression, negative symptoms, disorganization, and cognitive deficits)

• to mitigate antipsychotic-induced side effects (eg, initiating aripiprazole to treat hyperprolactinemia induced by another antipsychotic to which the patient has achieved a favorable response).23

Clinicians report using APP to treat as many as 50% of patients with a history of multiple psychotic episodes.23 For FEP patients, 23% of participants in the RAISE-ETP trial who were identified as possibly benefiting from therapy modification were prescribed APP.20 Regrettably, researchers have not found evidence to support a reported rationale for using APP—that lower dosages of individual antipsychotics when used in combination may avoid high-dosage prescriptions.24

Before implementing APP, thoroughly explore and manage reasons for a patient’s suboptimal response to monotherapy.25 An adequate trial with any antipsychotic should be at the highest tolerated dosage for 12 to 16 weeks. Be mindful that response to an APP trial may be the result of additional time on the original antipsychotic.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in FEP

Guideline recommendations. Most older guidelines for schizophrenia treatment suggest LAIA after multiple relapses related to medication nonadherence or when a patient prefers injected medication (Table 1).6-13 Expert consensus guidelines also recommend considering LAIA in patients who lack insight into their illness. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines7 state LAIA can be considered for inadequate adherence at any stage, whereas the 2010 British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) guidelines9 express uncertainty about their use in FEP, because of limited evidence. Both the BAP and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines13 urge clinicians to consider LAIA when avoiding nonadherence is a treatment priority.

Recently, the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuro-psychopharmacology (AFPBN) created expert consensus guidelines12 on using LAIA in practice. They recommend long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) as first-line maintenance treatment for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and for individuals experiencing a first recurrent episode. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines contain LAIA dosage recommendations for FEP (Table 2).10

Advances have been made in understanding the serious neurobiological adverse effects of psychotic relapses, including neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, that may explain the atrophic changes observed with psychotic episodes starting with the FEP. Protecting the patient from a second episode has become a vital therapeutic management goal26 (Figure 127).

Concerns. Compared with oral antipsychotics, LAIA offers clinical advantages:

• improved pharmacokinetic profile (lower “peaks” and higher “valleys”)

• more consistent plasma concentrations (no variability related to administration timing or food effects)

• no first-pass metabolism, which can ease the process of finding the lowest effective and safe dosage

• reduced administration burden and objective tracking of adherence with typical dosing every 2 to 4 weeks

• less stigmatizing than oral medication for FEP patients, such as college students living in a dormitory.28,29

Barriers to LAIA use include:

• slow dosage titration and increased time to reach steady state drug level

• oral supplementation for some (eg, risperidone microspheres and aripiprazole long-acting injectable)

• logistical challenges for some (eg, 3-hour post-injection monitoring for delirium sedation syndrome with olanzapine pamoate)

• additional planning to coordinate care for scheduled injections

• higher expenses up front

• local injection site reactions

• dosage adjustment difficulties if adverse effects occur.28,29

Adoption rates of LAIA are low, especially for FEP.30 Most surveys indicate that (1) physicians believe LAIA treatment is ineffective for FEP31 and (2) patients do not prefer injectable to oral antipsychotics,32 despite evidence to the contrary.33,34 A survey of 198 psychiatrists identified 3 factors that influenced their decisions against using LAIA patients with FEP:

• limited availability of SGA depot formulations (4, to date, in the United States)

• frequent rejection by the patient when LAIA is offered without adequate explanation or encouragement

• skepticism of FEP patients (and their family) who lack experience with relapse.35

In reality, when SGA depots were introduced in the United Kingdom, prescribing rates of LAIA did not increase. As for patient rejection being a major reason for not prescribing LAIA, few patients (5% to 36%) are offered depot injections, particularly in FEP.29 Most patients using LAIA are chronic, multi-episode, violent people who are receiving medications involuntarily.29 Interestingly, this survey did not find 2 factors to be influential in psychiatrists’ decision not to use LAIA in FEP:

• guidelines do not explicitly recommend depot treatment in FEP

• treatment in FEP may be limited to 1 year, therefore depot administration is not worthwhile.35

Preliminary evidence. At least a dozen studies have explored LAIA treatment for FEP, with the use of fluphenazine decanoate,36 perphenazine enanthate37 (discontinued), and risperidone microspheres.37-48 The research demonstrates the efficacy and safety of LAIA in FEP as measured by these endpoints:

• improved symptom control38,40-43,46,48

• adherence43,44,48

• reduced relapse rates37,43 and rehospitalizations37,47

• lesser reductions in white matter brain volume45

• no differences in extrapyramidal side effects or prolactin-associated adverse effects.48

A few small studies demonstrate significant differences in outcomes between risperidone LAIA and oral comparator groups (Table 3).43-45 Ongoing studies of LAIA use in FEP are comparing paliperidone palmitate with risperidone microspheres and other oral antipsychotics.49-51 No studies are examining olanzapine pamoate in FEP, likely because several guidelines do not recommended its use. No studies have been published regarding aripiprazole long-acting injectable in FEP. This LAIA formulation was approved in February 2013, and robust studies of the oral formulation in FEP are limited.52

Discussion and recommendations. Psychiatrists relying on subjective measures of antipsychotic adherence may inaccurately assess whether patients meet this criterion for LAIA use.53 LAIA could combat the high relapse rate in FEP, yet depot antipsychotics are prescribed infrequently for FEP patients (eg, for only 9.5% of participants in the RAISE-ETP study).20 Most schizophrenia treatment guidelines do not discuss LAIA use specifically in FEP, although the AFPBN expert consensus guidelines published in 2013 do recommend SGA depot formulations in FEP.12 SGA LAIA may be preferable, given its neuroprotective effects, in contrast to the neurotoxicity concerns of FGA LAIA.54,55

Relapses begin within a few months of illness stabilization after FEP, and >50% of patients relapse within 1 or 2 years2—the recommended minimum treatment duration for FEP.8,9,13 The use of LAIA is advisable in any patient with schizophrenia for whom long-term antipsychotic therapy is indicated.56 LAIA administration requirements objectively track medication adherence, which allows clinicians to be proactive in relapse prevention. Not using an intervention in FEP that improves adherence and decreases relapse rates contradicts our goal of instituting early, effective treatment to improve long-term functional outcomes (Figure 2).29

Considering clozapine in FEP

Guideline recommendations. Schizo-phrenia treatment guidelines and FDA labeling57 reserve clozapine for third-line treatment of refractory schizophrenia after 2 adequate antipsychotic trials have failed despite optimal dosing (Table 1).6-13 Some guidelines specify 1 of the 2 failed antipsychotic trials must include an SGA.6,7,10,11,13-16 Most say clozapine may be considered in patients with chronic aggression or hostility,7-9,14,16 or suicidal thoughts and behaviors.6-8,14,16 TMAP guidelines recommend a clozapine trial with concomitant substance abuse, persistent positive symptoms during 2 years of consistent medication treatment, and after 5 years of inadequate response (“treatment resistance”), regardless of the number of antipsychotic trials.7

Rationale and concerns. Clozapine is a superior choice for treatment-refractory delusions or hallucinations of schizophrenia, because it markedly enhances the response rate to antipsychotic therapy.58 Researchers therefore have investigated whether clozapine, compared with other antipsychotics, would yield more favorable initial and long-term outcomes when used first-line in FEP.

Preliminary evidence. Five studies have explored the use of clozapine as first-line therapy in FEP (Table 4).59-63 Interpreting the results is difficult because clozapine trials may be brief (mostly, 12 to 52 weeks); lack a comparator arm; suffer from a high attrition rate; enroll few patients; and lack potentially important outcome measures such as negative symptoms, suicidality, and functional assessment.

Overall, these studies demonstrate clozapine is as efficacious in this patient population as chlorpromazine (no difference in remission at 1-year, although clozapine-treated patients remitted faster and stayed in remission longer)60,61 or risperidone (no difference in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores).62

At present, clozapine has not been shown superior to other antipsychotics as a first-line treatment for FEP. Research does underscore the importance of a clozapine trial as third-line treatment for FEP patients who have not responded well to 2 SGA trials.63 Many of these nonresponders (77%) have demonstrated a favorable response when promptly switched to clozapine.64

Discussion and recommendations. The limited evidence argues against using clozapine earlier than as third-line treatment in FEP. Perhaps the high treatment response that characterizes FEP creates a ceiling effect that obscures differences in antipsychotic efficacy at this stage.65 Clozapine use as first-line treatment should be re-evaluated with more robust methodology. One approach could be to assess its benefit in FEP by the duration of untreated psychosis.

The odds of achieving remission have been shown to decrease by 15% for each year that psychosis has not been treated.59 Studies exploring the use of clozapine as a second-line agent for FEP also are warranted, as antipsychotic response during subsequent trials is substantially reduced. In fact, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidelines recommend this as an area for future research.11

For now, clozapine should continue to be reserved as second- or third-line treatment in a patient with FEP. The risks of clozapine’s potentially serious adverse effects (eg, agranulocytosis, seizures, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, myocarditis, pancreatitis, hypotension, sialorrhea, severe sedation, ileus) can be justified only in the treatment of severe and persistent psychotic symptoms.57

Bottom Line

Nonstandard use of antipsychotic monotherapy dosages beyond the approved FDA limit and combination antipsychotic therapy may be reasonable for select first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients. Strongly consider long-acting injectable antipsychotics in FEP to proactively combat the high relapse rate and more easily identify antipsychotic failure. Continue to use clozapine as second- or third-line therapy in FEP: Studies have not found that it is more efficacious than other antipsychotics for first-line use.

Related Resource

• Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project Early Treatment Program. National Institute of Mental Health. http://raiseetp.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify, Abilify Maintena

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluphenazine decanoate • Prolixin-D

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol decanoate • Haldol-D

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine pamoate • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone microspheres • Risperdal Consta

Disclosures

Dr. Gardner reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Nasrallah is a consultant to Acadia, Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Sunovion, and is a speaker for Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, and Sunovion.

1. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

2. Bradford DW, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. Pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia and related nonaffective psychoses. Drugs. 2003;63(21):2265-2283.

3. Lieberman JA, Koreen AR, Chakos M, et al. Factors influencing treatment response and outcome of first-episode schizophrenia: implications for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(suppl 9):5-9.

4. Agid O, Arenovich T, Sajeev G, et al. An algorithm-based approach to first-episode schizophrenia: response rates over 3 prospective antipsychotic trials with a retrospective data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1439-1444.

5. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis. An early stage of schizophrenia with distinct treatment needs. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):32-34,36-40,42.

6. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

7. Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Procedural Manual. Schizophrenia Treatment Algorithms. http://www.jpshealthnet.org/sites/default/files/ tmapalgorithmforschizophrenia.pdf. Updated April 2008. Accessed June 11, 2015.

8. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71-93.

9. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620.

10. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrok T, et al; WFSBP Task force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(1):2-44.

11. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 131: Management of schizophrenia. http://www.sign.ac.uk/ pdf/sign131.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed June 11, 2015.

12. Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serous mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE clinical guideline 178: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. https://www.nice.org. uk/guidance/cg178/resources/guidance-psychosis-and-schizophrenia-in-adults-treatment-and-management-pdf. Updated March 2014. Accessed June 16, 2015.

14. Canadian Psychiatric Association. Clinical practice guidelines. Treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(13 suppl 1):7S-57S.

15. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 11):3-80.

16. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. The Mount Sinai conference on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):5-16.

17. Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, et al. Relationship between dopamine D(2) occupancy, clinical response, and side effects: a double-blind PET study of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):514-520.

18. Fankhauser MP. Drug interactions with tobacco smoke: implications for patient care. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):12-16.

19. Agid O, Schulze L, Arenovich T, et al. Antipsychotic response in first-episode schizophrenia: efficacy of high doses and switching. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):1017-1022.

20. Robinson DG, Schooler NR, John M, et al. Prescription practices in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: data from the national RAISE-ETP study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(3):237-248.

21. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

22. Fisher MD, Reilly K, Isenberg K, et al. Antipsychotic patterns of use in patients with schizophrenia: polypharmacy versus monotherapy. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):341.

23. Barnes TR, Paton C. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia: benefits and risks. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(5):383-399.

24. John AP, Dragovic M. Antipsychotic polypharmacy is not associated with reduced dose of individual antipsychotics in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(2):193-195.

25. Nasrallah HA. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/specialty-focus/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/article/ treatment-resistant-schizophrenia/9be7bba3713d4a4cd68aa 8c92b79e5b1.html. Accessed June 16, 2015.

26. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

27. Nasrallah HA, Smeltzer DJ. Contemporary diagnosis and management of the patient with schizophrenia. 2nd ed. Newton, PA: Handbooks in Health Care Co; 2011.

28. McEvoy JP. Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 5):15-18.

29. Agid O, Foussias G, Remington G. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: their role in relapse prevention. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(14):2301-2317.

30. Kirschner M, Theodoridou A, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ attitude towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in subjects with a first episode psychosis. Ther Adv Psychophamacol. 2013;3(2):89-99.

31. Heres S, Hamann J, Mendel R, et al. Identifying the profile of optimal candidates for antipsychotic depot therapy: A cluster analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(8):1987-1993.

32. Heres S, Lambert M, Vauth R. Treatment of early episode in patents with schizophrenia: the role of long acting antipsychotics. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(suppl 2):1409-1413.

33. Heres S, Schmitz FS, Leucht S, et al. The attitude of patients towards antipsychotic depot treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(5):275-282.

34. Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, Weedon JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of long-acting injectable risperidone vs continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia patients: initial adherence outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1397-1406.

35. Heres S, Reichhart T, Hamann J, et al. Psychiatrists’ attitude to antipsychotic depot treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(5):297-301.

36. Kane JM, Rifkin A, Quitkin F, et al. Fluphenazine vs placebo in patients with remitted, acute first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(1):70-73.

37. Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K, Lönnqvist J, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of patients in a community care after first hospitalization due to schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: observational follow-up study. BMJ. 2006;333(7561):224.

38. Parellada E, Andrezina R, Milanova V, et al. Patients in the early phases of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders effectively treated with risperidone long-acting injectable. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(suppl 5):5-14.

39. Malla A, Binder C, Chue P. Comparison of long-acting injectable risperidone and oral novel antipsychotic drugs for treatment in early phase of schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Convention Society of Biological Psychiatry; Toronto, Canada; 2006.

40. Lasser RA, Bossie CA, Zhu Y, et al. Long-acting risperidone in young adults with early schizophrenia or schizoaffective illness. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):65-71.

41. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

42. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Oral versus injectable antipsychotic treatment in early psychosis: post hoc comparison of two studies. Clin Ther. 2008;30(12):2378-2386.

43. Kim B, Lee SH, Choi TK, et al. Effectiveness of risperidone long-acting injection in first-episode schizophrenia: in naturalistic setting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(5):1231-1235.

44. Weiden PJ, Schooler NJ, Weedon JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of long-acting injectable risperidone vs continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia patients: initial adherence outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1397-1406.

45. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Amar CP, et al. Long acting injection versus oral risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia: differential impact on white matter myelination trajectory. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(1):35-41.

46. Napryeyenko O, Burba B, Martinez G, et al. Risperidone long-acting injectable in recent-onset schizophrenia examined with clinician and patient self-report measures. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(2):200-202.

47. Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):603-609.

48. Dubois V, Megens J, Mertens C, et al. Long-acting risperidone in early-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Belgica. 2011;111(1):9-21.

49. ClinicalTrials.gov. Oral risperidone versus injectable paliperidone palmitate for treating first-episode schizophrenia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT01451736. Accessed June 16, 2015.

50. ClinicalTrials.gov. Brain myelination effects of paliperidone palmitate versus oral risperidone in first episode schizophrenia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/ show/NCT01458379. Accessed June 16, 2015.

51. ClinicalTrials.gov. Effects of paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics on clinical outcomes and MRI measures. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01359293. Accessed June 16, 2016.

52. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA. http:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda. Accessed January 11, 2015.

53. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46; quiz 47-48.

54. Nandra KS, Agius M. The difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics: the effects on neurogenesis. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(suppl 1):S95-S99.

55. Nasrallah HA. Haloperidol is clearly neurotoxic. Should it be banned? Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):7-8.

56. Kane JM, Garcia-Ribora C. Clinical guideline recommendations for antipsychotic long-acting injections. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;52:S63-S67.

57. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2014.

58. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):789-796.

59. Woerner MG, Robinson DG, Alvir JMJ, et al. Clozapine as a first treatment for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1514-1516.

60. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):995-1003.

61. Girgis RR, Phillips MR, Li X, et al. Clozapine v. chlorpromazine in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: 9-year outcomes of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):281-288.

62. Sanz-Fuentenebro J, Taboada D, Palomo T, et al. Randomized trial of clozapine vs. risperidone in treatment-naïve first-episode schizophrenia: results after one year. Schizophr Res. 2013;149(1-3):156-161.

63. Yang PD, Ji Z. The efficacy and related factors of clozapine on first-episode schizophrenia. Chin J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;23:155-158.

64. Agid O, Schulze L, Arenovich T, et al. Antipsychotic response in first-episode schizophrenia: efficacy of high doses and switching. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):1017-1022.

65. Remington G, Agid O, Foussias G, et al. Clozapine’s role in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):146-151.

1. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

2. Bradford DW, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. Pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia and related nonaffective psychoses. Drugs. 2003;63(21):2265-2283.

3. Lieberman JA, Koreen AR, Chakos M, et al. Factors influencing treatment response and outcome of first-episode schizophrenia: implications for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(suppl 9):5-9.

4. Agid O, Arenovich T, Sajeev G, et al. An algorithm-based approach to first-episode schizophrenia: response rates over 3 prospective antipsychotic trials with a retrospective data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1439-1444.

5. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis. An early stage of schizophrenia with distinct treatment needs. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):32-34,36-40,42.

6. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

7. Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Procedural Manual. Schizophrenia Treatment Algorithms. http://www.jpshealthnet.org/sites/default/files/ tmapalgorithmforschizophrenia.pdf. Updated April 2008. Accessed June 11, 2015.

8. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71-93.

9. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620.

10. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrok T, et al; WFSBP Task force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(1):2-44.

11. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 131: Management of schizophrenia. http://www.sign.ac.uk/ pdf/sign131.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed June 11, 2015.

12. Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serous mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE clinical guideline 178: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. https://www.nice.org. uk/guidance/cg178/resources/guidance-psychosis-and-schizophrenia-in-adults-treatment-and-management-pdf. Updated March 2014. Accessed June 16, 2015.

14. Canadian Psychiatric Association. Clinical practice guidelines. Treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(13 suppl 1):7S-57S.

15. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 11):3-80.

16. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. The Mount Sinai conference on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):5-16.

17. Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, et al. Relationship between dopamine D(2) occupancy, clinical response, and side effects: a double-blind PET study of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):514-520.

18. Fankhauser MP. Drug interactions with tobacco smoke: implications for patient care. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):12-16.

19. Agid O, Schulze L, Arenovich T, et al. Antipsychotic response in first-episode schizophrenia: efficacy of high doses and switching. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):1017-1022.