User login

Answer

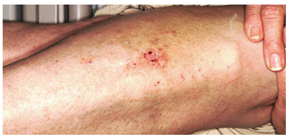

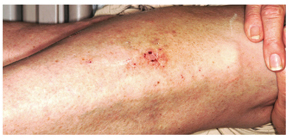

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

A 30-year-old man presents with a pruritic rash that first affected both legs and was followed two weeks later by the appearance of a different but equally pruritic rash on his volar forearms. These rashes have persisted despite the use of OTC topical steroid and antifungal creams, triple-antibiotic ointment, and frequent application of rubbing alcohol. Eczema has been a problem throughout the patient’s life, but since his 20s, it has mostly affected his lower legs. As a result, he has gotten into the habit of scratching, even fantasizing about being able to do so at home. Despite being remarkably atopic, with seasonal allergies and generally sensitive skin, he claims to be otherwise healthy. Examination of the patient’s legs shows heavily lichenified papulosquamous involvement of both legs. There are numerous focal areas of scabbing, redness, and edema, which sharply spare the skin under his socks, thin out, then disappear well below the knees. The patient is even observed scratching these areas as the history is taken, and readily admits doing so several times a day. A fairly dense, symmetrical papulovesicular rash is noted on both volar forearms, with only a few lesions remaining intact because of scratching. Elsewhere, his elbows, knees, scalp, and nail plates are free of significant changes.