User login

Story

ML was an 83-year-old woman who presented from her assisted-living facility to her local emergency room with abdominal pain.

She described acute-onset epigastric pain within minutes of her evening meal. The pain was rated 5 out of 10 and was associated with some nausea but no emesis. ML had a past medical history of irritable bowel symptoms along with diverticulosis, but she was otherwise healthy and took no regular medications except for occasional loperamide. Her CBC, amylase, lipase, and chemistry panels were normal. CT scan of the abdomen showed mildly dilated loops of small bowel.

ML was admitted to the hospital by her family physician, who consulted a gastroenterologist the following morning. The gastroenterologist concluded that ML was most likely suffering from food intolerance and recommended bowel rest and observation.

ML continued to have the pain and was unable to advance her diet. On hospital day 2, the GI consultant noted that ML’s abdomen was soft and nondistended, but he ordered an acute abdominal series and requested to be called with the results. The study was not completed until 5:30 p.m. Later that evening during a routine chart check, ML’s nurse noted that the acute abdominal series had been completed, but not read. She paged the hospitalist on call to review the film so that she could contact the GI consultant pursuant to his order.

Dr. Hospitalist reviewed the film and called the nurse back to report that the film showed no free air but the colon was dilated. The nurse subsequently called the GI consultant and relayed the information. No new orders were received.

At 7 a.m. on hospital day 3, ML developed mental status changes. Her abdomen was now noted to be distended with rigidity. ML was evaluated by her family physician and the GI consultant.

A surgical consult was obtained along with further imaging, which confirmed a small bowel obstruction (SBO) with massively dilated small bowel. Morning labs also showed acute kidney injury. Formal radiology review of the abdominal series looked at by Dr. Hospitalist established the presence of significant small bowel dilatation highly concerning for SBO. ML was transferred to a larger hospital where she eventually underwent an exploratory laparotomy for perforated bowel. Following a tumultuous postoperative course including dialysis, ML expired 1 month later.

Complaint

ML’s daughter was a pediatrician at a major teaching institution nearby. She was frustrated that the original CT showed dilated small bowel and that the conclusion of her treating doctors was that her mother was suffering from "food intolerance." Together with her father, they filed suit against the hospital, the GI consultant, and Dr. Hospitalist.

ML’s family alleged that ML had small bowel obstruction from the start and should have had surgical involvement soon enough to intervene before she ultimately perforated her bowel. Surgical repair prior to perforation would have significantly changed ML’s outcome.

They further alleged that Dr. Hospitalist was negligent in her review of the abdominal radiographs and she had a duty to see and examine ML, communicate directly with the GI consultant, and obtain a STAT surgical consult.

Scientific principles

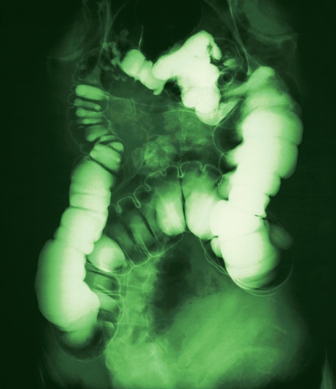

Small bowel obstruction occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted, and it is usually confirmed by plain abdominal radiography.

The most frequent causes are postoperative adhesions and hernias, which cause extrinsic compression of the intestine. Obstruction leads to dilation of the stomach and small intestine proximal to the blockage, while distal to the blockage the bowel will decompress as luminal contents are passed. Symptoms include obstipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. As the small bowel dilates, its blood flow can be compromised, leading to strangulation and sepsis.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable sign or symptom differentiating patients with strangulation or impending strangulation from those in whom surgery will not be necessary.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

For the night in question, Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she had two roles and only one of them involved ML.

First, Dr. Hospitalist was responsible for admissions and cross-coverage for her own group’s patients at night. ML was not a patient of Dr. Hospitalist or her group. ML was being cared for by her own family physician and his practice group 24/7.

Second, Dr. Hospitalist was the hospital’s overnight "house doctor" for codes, IV access, radiology "wet reads," and other emergencies. It was in this capacity that Dr. Hospitalist was contacted. Dr. Hospitalist was not a radiologist. As a house doctor, Dr. Hospitalist would be expected to look for serious and life-threatening findings and to rule out the presence of free air. Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she was never asked to see ML by the attending physician or even by the nurse.

The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist had a duty to question the nurse regarding ML’s condition and, because of the evidence for obstruction on the film, see ML for an assessment. The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist’s misinterpretation of the film (i.e., colon dilatation in the face of obvious small bowel dilatation) represented gross incompetence.

Dr. Hospitalist testified that she had no memory of ML, this case, or what she may or may not have told the nurse that night. ML’s medical record confirms that Dr. Hospitalist wrote no orders or charted any notes on her. The only documentation of Dr. Hospitalist’s "wet read" was in ML’s nursing notes.

The GI consultant testified that he had no memory of his call from the nurse with the radiograph results. The nurse testified that she wouldn’t have written "colon dilatation" if Dr. Hospitalist had told her it was small bowel.

Conclusion

The "house doc" role typically encompasses a limited scope of responsibility. But all physicians carry a professional duty to the patients that we become involved with.

By performing a "wet read" on a film of ML, Dr. Hospitalist established a doctor-patient relationship. It would have been prudent for Dr. Hospitalist to record her film interpretation herself (thus creating an opportunity for brief chart review), and to call the GI consultant with the information instead of relying on the nurse. A 1-minute conversation between Dr. Hospitalist and the GI consultant may have led to further intervention by either party.

Ultimately this case was resolved for an undisclosed amount. In the "house doc" role, Dr. Hospitalist was functioning as an employee of the hospital (despite being an independent contractor), and there were hospital care issues independent of Dr. Hospitalist. However, Dr. Hospitalist could have avoided her role in this suit with better documentation and communication.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Medicolegal Review has the opportunity to become the morbidity and mortality conference of the modern era. Each month, this column presents a case vignette that explores some aspect of medicine and the applicable standard of care.

The more we share in our collective failures, the less likely we are to repeat those same mistakes.

Medicolegal Review has the opportunity to become the morbidity and mortality conference of the modern era. Each month, this column presents a case vignette that explores some aspect of medicine and the applicable standard of care.

The more we share in our collective failures, the less likely we are to repeat those same mistakes.

Medicolegal Review has the opportunity to become the morbidity and mortality conference of the modern era. Each month, this column presents a case vignette that explores some aspect of medicine and the applicable standard of care.

The more we share in our collective failures, the less likely we are to repeat those same mistakes.

Story

ML was an 83-year-old woman who presented from her assisted-living facility to her local emergency room with abdominal pain.

She described acute-onset epigastric pain within minutes of her evening meal. The pain was rated 5 out of 10 and was associated with some nausea but no emesis. ML had a past medical history of irritable bowel symptoms along with diverticulosis, but she was otherwise healthy and took no regular medications except for occasional loperamide. Her CBC, amylase, lipase, and chemistry panels were normal. CT scan of the abdomen showed mildly dilated loops of small bowel.

ML was admitted to the hospital by her family physician, who consulted a gastroenterologist the following morning. The gastroenterologist concluded that ML was most likely suffering from food intolerance and recommended bowel rest and observation.

ML continued to have the pain and was unable to advance her diet. On hospital day 2, the GI consultant noted that ML’s abdomen was soft and nondistended, but he ordered an acute abdominal series and requested to be called with the results. The study was not completed until 5:30 p.m. Later that evening during a routine chart check, ML’s nurse noted that the acute abdominal series had been completed, but not read. She paged the hospitalist on call to review the film so that she could contact the GI consultant pursuant to his order.

Dr. Hospitalist reviewed the film and called the nurse back to report that the film showed no free air but the colon was dilated. The nurse subsequently called the GI consultant and relayed the information. No new orders were received.

At 7 a.m. on hospital day 3, ML developed mental status changes. Her abdomen was now noted to be distended with rigidity. ML was evaluated by her family physician and the GI consultant.

A surgical consult was obtained along with further imaging, which confirmed a small bowel obstruction (SBO) with massively dilated small bowel. Morning labs also showed acute kidney injury. Formal radiology review of the abdominal series looked at by Dr. Hospitalist established the presence of significant small bowel dilatation highly concerning for SBO. ML was transferred to a larger hospital where she eventually underwent an exploratory laparotomy for perforated bowel. Following a tumultuous postoperative course including dialysis, ML expired 1 month later.

Complaint

ML’s daughter was a pediatrician at a major teaching institution nearby. She was frustrated that the original CT showed dilated small bowel and that the conclusion of her treating doctors was that her mother was suffering from "food intolerance." Together with her father, they filed suit against the hospital, the GI consultant, and Dr. Hospitalist.

ML’s family alleged that ML had small bowel obstruction from the start and should have had surgical involvement soon enough to intervene before she ultimately perforated her bowel. Surgical repair prior to perforation would have significantly changed ML’s outcome.

They further alleged that Dr. Hospitalist was negligent in her review of the abdominal radiographs and she had a duty to see and examine ML, communicate directly with the GI consultant, and obtain a STAT surgical consult.

Scientific principles

Small bowel obstruction occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted, and it is usually confirmed by plain abdominal radiography.

The most frequent causes are postoperative adhesions and hernias, which cause extrinsic compression of the intestine. Obstruction leads to dilation of the stomach and small intestine proximal to the blockage, while distal to the blockage the bowel will decompress as luminal contents are passed. Symptoms include obstipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. As the small bowel dilates, its blood flow can be compromised, leading to strangulation and sepsis.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable sign or symptom differentiating patients with strangulation or impending strangulation from those in whom surgery will not be necessary.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

For the night in question, Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she had two roles and only one of them involved ML.

First, Dr. Hospitalist was responsible for admissions and cross-coverage for her own group’s patients at night. ML was not a patient of Dr. Hospitalist or her group. ML was being cared for by her own family physician and his practice group 24/7.

Second, Dr. Hospitalist was the hospital’s overnight "house doctor" for codes, IV access, radiology "wet reads," and other emergencies. It was in this capacity that Dr. Hospitalist was contacted. Dr. Hospitalist was not a radiologist. As a house doctor, Dr. Hospitalist would be expected to look for serious and life-threatening findings and to rule out the presence of free air. Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she was never asked to see ML by the attending physician or even by the nurse.

The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist had a duty to question the nurse regarding ML’s condition and, because of the evidence for obstruction on the film, see ML for an assessment. The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist’s misinterpretation of the film (i.e., colon dilatation in the face of obvious small bowel dilatation) represented gross incompetence.

Dr. Hospitalist testified that she had no memory of ML, this case, or what she may or may not have told the nurse that night. ML’s medical record confirms that Dr. Hospitalist wrote no orders or charted any notes on her. The only documentation of Dr. Hospitalist’s "wet read" was in ML’s nursing notes.

The GI consultant testified that he had no memory of his call from the nurse with the radiograph results. The nurse testified that she wouldn’t have written "colon dilatation" if Dr. Hospitalist had told her it was small bowel.

Conclusion

The "house doc" role typically encompasses a limited scope of responsibility. But all physicians carry a professional duty to the patients that we become involved with.

By performing a "wet read" on a film of ML, Dr. Hospitalist established a doctor-patient relationship. It would have been prudent for Dr. Hospitalist to record her film interpretation herself (thus creating an opportunity for brief chart review), and to call the GI consultant with the information instead of relying on the nurse. A 1-minute conversation between Dr. Hospitalist and the GI consultant may have led to further intervention by either party.

Ultimately this case was resolved for an undisclosed amount. In the "house doc" role, Dr. Hospitalist was functioning as an employee of the hospital (despite being an independent contractor), and there were hospital care issues independent of Dr. Hospitalist. However, Dr. Hospitalist could have avoided her role in this suit with better documentation and communication.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

ML was an 83-year-old woman who presented from her assisted-living facility to her local emergency room with abdominal pain.

She described acute-onset epigastric pain within minutes of her evening meal. The pain was rated 5 out of 10 and was associated with some nausea but no emesis. ML had a past medical history of irritable bowel symptoms along with diverticulosis, but she was otherwise healthy and took no regular medications except for occasional loperamide. Her CBC, amylase, lipase, and chemistry panels were normal. CT scan of the abdomen showed mildly dilated loops of small bowel.

ML was admitted to the hospital by her family physician, who consulted a gastroenterologist the following morning. The gastroenterologist concluded that ML was most likely suffering from food intolerance and recommended bowel rest and observation.

ML continued to have the pain and was unable to advance her diet. On hospital day 2, the GI consultant noted that ML’s abdomen was soft and nondistended, but he ordered an acute abdominal series and requested to be called with the results. The study was not completed until 5:30 p.m. Later that evening during a routine chart check, ML’s nurse noted that the acute abdominal series had been completed, but not read. She paged the hospitalist on call to review the film so that she could contact the GI consultant pursuant to his order.

Dr. Hospitalist reviewed the film and called the nurse back to report that the film showed no free air but the colon was dilated. The nurse subsequently called the GI consultant and relayed the information. No new orders were received.

At 7 a.m. on hospital day 3, ML developed mental status changes. Her abdomen was now noted to be distended with rigidity. ML was evaluated by her family physician and the GI consultant.

A surgical consult was obtained along with further imaging, which confirmed a small bowel obstruction (SBO) with massively dilated small bowel. Morning labs also showed acute kidney injury. Formal radiology review of the abdominal series looked at by Dr. Hospitalist established the presence of significant small bowel dilatation highly concerning for SBO. ML was transferred to a larger hospital where she eventually underwent an exploratory laparotomy for perforated bowel. Following a tumultuous postoperative course including dialysis, ML expired 1 month later.

Complaint

ML’s daughter was a pediatrician at a major teaching institution nearby. She was frustrated that the original CT showed dilated small bowel and that the conclusion of her treating doctors was that her mother was suffering from "food intolerance." Together with her father, they filed suit against the hospital, the GI consultant, and Dr. Hospitalist.

ML’s family alleged that ML had small bowel obstruction from the start and should have had surgical involvement soon enough to intervene before she ultimately perforated her bowel. Surgical repair prior to perforation would have significantly changed ML’s outcome.

They further alleged that Dr. Hospitalist was negligent in her review of the abdominal radiographs and she had a duty to see and examine ML, communicate directly with the GI consultant, and obtain a STAT surgical consult.

Scientific principles

Small bowel obstruction occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted, and it is usually confirmed by plain abdominal radiography.

The most frequent causes are postoperative adhesions and hernias, which cause extrinsic compression of the intestine. Obstruction leads to dilation of the stomach and small intestine proximal to the blockage, while distal to the blockage the bowel will decompress as luminal contents are passed. Symptoms include obstipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. As the small bowel dilates, its blood flow can be compromised, leading to strangulation and sepsis.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable sign or symptom differentiating patients with strangulation or impending strangulation from those in whom surgery will not be necessary.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

For the night in question, Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she had two roles and only one of them involved ML.

First, Dr. Hospitalist was responsible for admissions and cross-coverage for her own group’s patients at night. ML was not a patient of Dr. Hospitalist or her group. ML was being cared for by her own family physician and his practice group 24/7.

Second, Dr. Hospitalist was the hospital’s overnight "house doctor" for codes, IV access, radiology "wet reads," and other emergencies. It was in this capacity that Dr. Hospitalist was contacted. Dr. Hospitalist was not a radiologist. As a house doctor, Dr. Hospitalist would be expected to look for serious and life-threatening findings and to rule out the presence of free air. Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she was never asked to see ML by the attending physician or even by the nurse.

The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist had a duty to question the nurse regarding ML’s condition and, because of the evidence for obstruction on the film, see ML for an assessment. The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist’s misinterpretation of the film (i.e., colon dilatation in the face of obvious small bowel dilatation) represented gross incompetence.

Dr. Hospitalist testified that she had no memory of ML, this case, or what she may or may not have told the nurse that night. ML’s medical record confirms that Dr. Hospitalist wrote no orders or charted any notes on her. The only documentation of Dr. Hospitalist’s "wet read" was in ML’s nursing notes.

The GI consultant testified that he had no memory of his call from the nurse with the radiograph results. The nurse testified that she wouldn’t have written "colon dilatation" if Dr. Hospitalist had told her it was small bowel.

Conclusion

The "house doc" role typically encompasses a limited scope of responsibility. But all physicians carry a professional duty to the patients that we become involved with.

By performing a "wet read" on a film of ML, Dr. Hospitalist established a doctor-patient relationship. It would have been prudent for Dr. Hospitalist to record her film interpretation herself (thus creating an opportunity for brief chart review), and to call the GI consultant with the information instead of relying on the nurse. A 1-minute conversation between Dr. Hospitalist and the GI consultant may have led to further intervention by either party.

Ultimately this case was resolved for an undisclosed amount. In the "house doc" role, Dr. Hospitalist was functioning as an employee of the hospital (despite being an independent contractor), and there were hospital care issues independent of Dr. Hospitalist. However, Dr. Hospitalist could have avoided her role in this suit with better documentation and communication.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.