User login

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

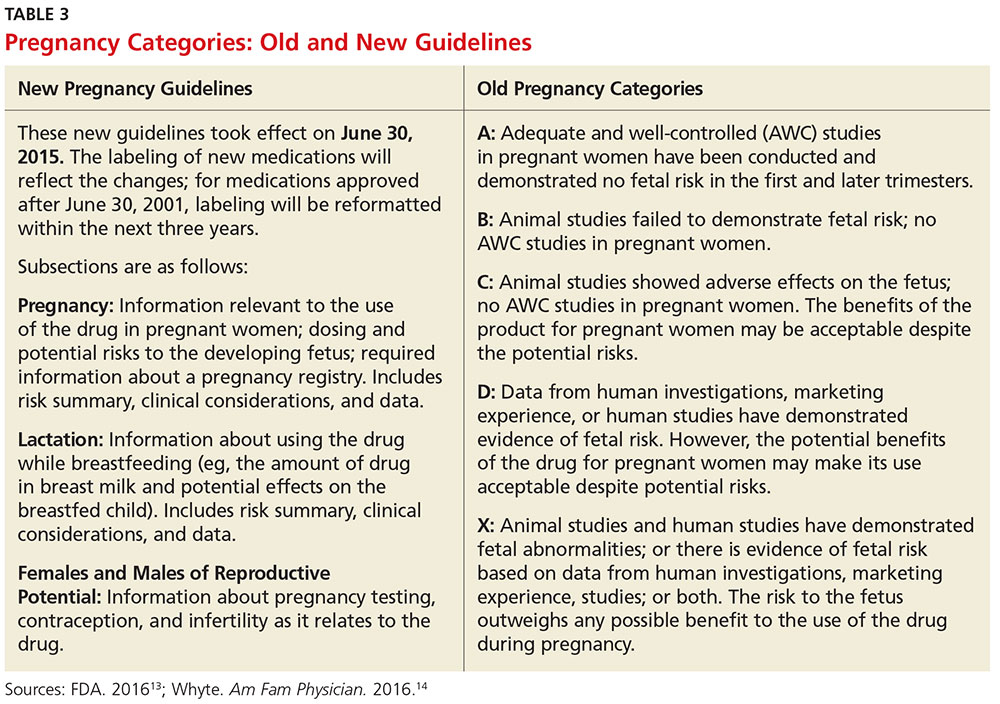

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.

14. Whyte J. FDA implements new labeling for medications used during pregnancy and lactation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(1):12-13.

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.

14. Whyte J. FDA implements new labeling for medications used during pregnancy and lactation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(1):12-13.

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.

14. Whyte J. FDA implements new labeling for medications used during pregnancy and lactation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(1):12-13.