User login

Should you treat asymptomatic bacteriuria in an older adult with altered mental status?

THE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and osteopenia was brought to the emergency department (ED) by her daughter. The woman had fallen 2 days earlier and had been experiencing a change in mental status (confusion) for the previous 4 days. Prior to her change in mental status, the patient had been independent in all activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Her daughter could not recall any symptoms of illness; new or recently changed medications; complaints of pain, constipation, diarrhea, urinary frequency, or hematuria; or changes in continence prior to the onset of her mother’s confusion.

The patient’s medications included amlodipine, atorvastatin, calcium/vitamin D, and acetaminophen (as needed). In the ED, her vital signs were normal, and her cardiopulmonary and abdominal exams were unremarkable. A limited neurologic exam showed that the patient was oriented only to person and could not answer questions about her symptoms or follow commands. She could move all of her extremities equally and could ambulate; she had no facial asymmetry or slurred speech. Her exam was negative for orthostatic hypotension.

Her complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and troponin levels were normal. Her electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with no abnormalities. X-rays of her right hip and elbow were negative for fracture. Computed tomography of her head was negative for acute findings, and a chest x-ray was normal.

Her urinalysis showed many bacteria and large leukocyte esterase, and a urine culture was sent out. She was hemodynamically stable and there were no known urinary symptoms, so no empiric antibiotics were started. She was admitted for further evaluation of her altered mental status (AMS).

On our service, she was given intravenous fluids, and oral intake was encouraged. She had normal levels of B12, folic acid, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. She was negative for HIV and syphilis. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with normal electrocardiograms and troponin levels. Her telemetry showed a normal sinus rhythm.

After 2 days, her vital signs and labs remained stable and no other abnormalities were found; however, she had not returned to her baseline mental status. Then the urine culture returned with > 105 CFU/mL of Escherichia coli, prompting a resident to curbside me (AP) and ask: “I shouldn’t treat this patient based on her urine culture—she’s just colonized, right? Or should I treat her because she’s altered?”

Continue to: THE CHALLENGE

THE CHALLENGE

Identifying and managing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in older adults often presents a challenge, further complicated if patients have AMS or cognitive impairment and are unable to confirm or deny urinary symptoms.

Consider, for instance, the definition of symptomatic UTI: significant bacteriuria (≥ 105 CFU/mL) and pyuria (> 10 WBC/hpf) with UTI-specific symptoms (fever, acute dysuria, new or worsening urgency or frequency, new urinary incontinence, gross hematuria, and suprapubic or costovertebral angle pain or tenderness).1 In older adults, these parameters require a more careful look.

For instance, while we use the cutoff of ≥ 105 CFU/mL to define “significant” bacteriuria, the truth is that we don’t know the colony count threshold that can help identify patients who are at risk of serious illness and might benefit from antibiotic treatment.2

After reviewing the culture results, clinicians then face 2 specific challenges: differentiating between acute vs chronic symptoms and related vs unrelated symptoms in the older adult population.

Challenge 1: There is a high prevalence of chronic genitourinary symptoms in older adults that can sometimes make it hard to distinguish between an acute UTI and the acute recognition of a chronic, non-UTI problem.1

Continue to: Challenge 2

Challenge 2: There is a high prevalence of multimorbidity in older adults. For instance, diuretics for heart failure can cause UTI-specific symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and even incontinence. Cognitive impairment can make it difficult to obtain the key components of the history needed to make a UTI diagnosis.1

Lastly, there are aspects of normal aging physiology that complicate the detection of infections, such as the fact that older adults may not mount a “true” fever to meet criteria for a symptomatic UTI. Therefore, fever in institutionalized or frail community-dwelling older adults has been redefined as an oral temperature ≥ 100 °F, 2 repeated oral temperatures > 99 °F, or an increase in temperature ≥ 2 °F from baseline.3

So how to proceed with our case patient? The following questions helped guide the approach to her care.

Is this patient asymptomatic?

Yes. The patient presented with nonspecific symptoms (falls and delirium) with bacteriuria suggesting asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). These symptoms are referred to as geriatric syndromes that, by definition, are “multifactorial health conditions that occur when the accumulated effects of impairments in multiple systems render an older person vulnerable to situational challenges.”4

As geriatric syndromes, falls and delirium are unlikely to be caused by one process, such as a UTI, but rather from multiple morbid processes. It is also important to note that there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

Continue to: So, while we could...

So, while we could have diagnosed a UTI in this older adult with bacteriuria and delirium, it would have been premature closure and an incomplete assessment. We would have risked potentially missing other significant causes of her delirium and unnecessarily exposing the patient to antibiotics.

Are antibiotics generally useful in older adults who you believe to be asymptomatic with a urine culture showing bacteriuria?

No. The goal of antibiotic treatment for a symptomatic UTI is to ameliorate symptoms; therefore, there is no indication for antibiotics in ASB and no evidence of survival benefit.2 And, as noted earlier, there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

The use of antibiotics in the asymptomatic setting will eradicate any bacteriuria but also increase the risk of reinfection, resistant organisms, antibiotic adverse reactions, and medication interactions.1

What is the recommendation for management of nonspecific symptoms, such as delirium and falls, in a geriatric patient such as this one with bacteriuria?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)’s 2019 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria recommends a thorough assessment (for other causes) and careful observation, rather than immediate antimicrobial treatment and cessation of evaluation for other causes.5 (IDSA made this recommendation based on low-quality evidence.) The group found a high certainty of harm and low certainty of benefit in treating older adults with antibiotics for ASB.

This recommendation highlights the key geriatric principle of “geriatric syndromes” and the multifactorial nature of findings such as delirium and falls. It encourages clinicians to continue their thorough assessment for other causes in addition to bacteriuria.5 Even in the event that antibiotics are immediately initiated, we would recommend avoiding premature closure and continuing to evaluate for other causes.

Continue to: It is reasonable to...

It is reasonable to obtain a dipstick if, after the observation period (1-7 days, with earlier follow-up for frail patients), the patient continues to have the nonspecific symptoms.1 If the dipstick is negative, there is no need for further evaluation of UTI. If it’s positive, then it’s appropriate to send for urinalysis and urine culture.1

If the urine culture is negative, continue looking for other etiologies. If it’s positive, but there is resolution of symptoms, there is no need to treat. If it’s positive and symptoms persist, consider antibiotic treatment.1

CASE RESOLUTION

The team closely monitored the patient and delayed empiric antibiotics while continuing the AMS work-up. After 2 days in the hospital, her delirium persisted, but she had no UTI-specific symptoms and she remained hemodynamically stable.

I (AP) recommended antibiotic treatment guided by the urine culture sensitivity report: initially 1 g of ceftriaxone IV q24h with transition (after symptom improvement and prior to discharge) to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg q12h, for a total of 10 days of treatment. I emphasized that we were treating bacteriuria with persisting delirium without any other etiology identified. The patient returned to her baseline mental status after a few days of treatment and was discharged home.

THE TAKEAWAY

Avoid premature closure by stopping at the diagnosis of a “UTI” in an older adult with nonspecific symptoms and bacteriuria to avoid the risk of overlooking other important and potentially life-threatening causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

L. Amanda Perry, MD, 1919 West Taylor Street, Mail Code 663, Chicago, IL 60612; Lperry74@uic.edu

1. Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:844-854. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303

2. Finucane TE. “Urinary tract infection”- requiem for a heavyweight. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1650-1655. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14907

3. Ashraf MS, Gaur S, Bushen OY, et al; Infection Advisory SubCommittee for AMDA—The Society of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of urinary tract infections in post-acute and long-term care settings: a consensus statement from AMDA’s Infection Advisory Subcommittee. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:12-24 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.004

4. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti, ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

5. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1121

THE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and osteopenia was brought to the emergency department (ED) by her daughter. The woman had fallen 2 days earlier and had been experiencing a change in mental status (confusion) for the previous 4 days. Prior to her change in mental status, the patient had been independent in all activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Her daughter could not recall any symptoms of illness; new or recently changed medications; complaints of pain, constipation, diarrhea, urinary frequency, or hematuria; or changes in continence prior to the onset of her mother’s confusion.

The patient’s medications included amlodipine, atorvastatin, calcium/vitamin D, and acetaminophen (as needed). In the ED, her vital signs were normal, and her cardiopulmonary and abdominal exams were unremarkable. A limited neurologic exam showed that the patient was oriented only to person and could not answer questions about her symptoms or follow commands. She could move all of her extremities equally and could ambulate; she had no facial asymmetry or slurred speech. Her exam was negative for orthostatic hypotension.

Her complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and troponin levels were normal. Her electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with no abnormalities. X-rays of her right hip and elbow were negative for fracture. Computed tomography of her head was negative for acute findings, and a chest x-ray was normal.

Her urinalysis showed many bacteria and large leukocyte esterase, and a urine culture was sent out. She was hemodynamically stable and there were no known urinary symptoms, so no empiric antibiotics were started. She was admitted for further evaluation of her altered mental status (AMS).

On our service, she was given intravenous fluids, and oral intake was encouraged. She had normal levels of B12, folic acid, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. She was negative for HIV and syphilis. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with normal electrocardiograms and troponin levels. Her telemetry showed a normal sinus rhythm.

After 2 days, her vital signs and labs remained stable and no other abnormalities were found; however, she had not returned to her baseline mental status. Then the urine culture returned with > 105 CFU/mL of Escherichia coli, prompting a resident to curbside me (AP) and ask: “I shouldn’t treat this patient based on her urine culture—she’s just colonized, right? Or should I treat her because she’s altered?”

Continue to: THE CHALLENGE

THE CHALLENGE

Identifying and managing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in older adults often presents a challenge, further complicated if patients have AMS or cognitive impairment and are unable to confirm or deny urinary symptoms.

Consider, for instance, the definition of symptomatic UTI: significant bacteriuria (≥ 105 CFU/mL) and pyuria (> 10 WBC/hpf) with UTI-specific symptoms (fever, acute dysuria, new or worsening urgency or frequency, new urinary incontinence, gross hematuria, and suprapubic or costovertebral angle pain or tenderness).1 In older adults, these parameters require a more careful look.

For instance, while we use the cutoff of ≥ 105 CFU/mL to define “significant” bacteriuria, the truth is that we don’t know the colony count threshold that can help identify patients who are at risk of serious illness and might benefit from antibiotic treatment.2

After reviewing the culture results, clinicians then face 2 specific challenges: differentiating between acute vs chronic symptoms and related vs unrelated symptoms in the older adult population.

Challenge 1: There is a high prevalence of chronic genitourinary symptoms in older adults that can sometimes make it hard to distinguish between an acute UTI and the acute recognition of a chronic, non-UTI problem.1

Continue to: Challenge 2

Challenge 2: There is a high prevalence of multimorbidity in older adults. For instance, diuretics for heart failure can cause UTI-specific symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and even incontinence. Cognitive impairment can make it difficult to obtain the key components of the history needed to make a UTI diagnosis.1

Lastly, there are aspects of normal aging physiology that complicate the detection of infections, such as the fact that older adults may not mount a “true” fever to meet criteria for a symptomatic UTI. Therefore, fever in institutionalized or frail community-dwelling older adults has been redefined as an oral temperature ≥ 100 °F, 2 repeated oral temperatures > 99 °F, or an increase in temperature ≥ 2 °F from baseline.3

So how to proceed with our case patient? The following questions helped guide the approach to her care.

Is this patient asymptomatic?

Yes. The patient presented with nonspecific symptoms (falls and delirium) with bacteriuria suggesting asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). These symptoms are referred to as geriatric syndromes that, by definition, are “multifactorial health conditions that occur when the accumulated effects of impairments in multiple systems render an older person vulnerable to situational challenges.”4

As geriatric syndromes, falls and delirium are unlikely to be caused by one process, such as a UTI, but rather from multiple morbid processes. It is also important to note that there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

Continue to: So, while we could...

So, while we could have diagnosed a UTI in this older adult with bacteriuria and delirium, it would have been premature closure and an incomplete assessment. We would have risked potentially missing other significant causes of her delirium and unnecessarily exposing the patient to antibiotics.

Are antibiotics generally useful in older adults who you believe to be asymptomatic with a urine culture showing bacteriuria?

No. The goal of antibiotic treatment for a symptomatic UTI is to ameliorate symptoms; therefore, there is no indication for antibiotics in ASB and no evidence of survival benefit.2 And, as noted earlier, there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

The use of antibiotics in the asymptomatic setting will eradicate any bacteriuria but also increase the risk of reinfection, resistant organisms, antibiotic adverse reactions, and medication interactions.1

What is the recommendation for management of nonspecific symptoms, such as delirium and falls, in a geriatric patient such as this one with bacteriuria?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)’s 2019 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria recommends a thorough assessment (for other causes) and careful observation, rather than immediate antimicrobial treatment and cessation of evaluation for other causes.5 (IDSA made this recommendation based on low-quality evidence.) The group found a high certainty of harm and low certainty of benefit in treating older adults with antibiotics for ASB.

This recommendation highlights the key geriatric principle of “geriatric syndromes” and the multifactorial nature of findings such as delirium and falls. It encourages clinicians to continue their thorough assessment for other causes in addition to bacteriuria.5 Even in the event that antibiotics are immediately initiated, we would recommend avoiding premature closure and continuing to evaluate for other causes.

Continue to: It is reasonable to...

It is reasonable to obtain a dipstick if, after the observation period (1-7 days, with earlier follow-up for frail patients), the patient continues to have the nonspecific symptoms.1 If the dipstick is negative, there is no need for further evaluation of UTI. If it’s positive, then it’s appropriate to send for urinalysis and urine culture.1

If the urine culture is negative, continue looking for other etiologies. If it’s positive, but there is resolution of symptoms, there is no need to treat. If it’s positive and symptoms persist, consider antibiotic treatment.1

CASE RESOLUTION

The team closely monitored the patient and delayed empiric antibiotics while continuing the AMS work-up. After 2 days in the hospital, her delirium persisted, but she had no UTI-specific symptoms and she remained hemodynamically stable.

I (AP) recommended antibiotic treatment guided by the urine culture sensitivity report: initially 1 g of ceftriaxone IV q24h with transition (after symptom improvement and prior to discharge) to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg q12h, for a total of 10 days of treatment. I emphasized that we were treating bacteriuria with persisting delirium without any other etiology identified. The patient returned to her baseline mental status after a few days of treatment and was discharged home.

THE TAKEAWAY

Avoid premature closure by stopping at the diagnosis of a “UTI” in an older adult with nonspecific symptoms and bacteriuria to avoid the risk of overlooking other important and potentially life-threatening causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

L. Amanda Perry, MD, 1919 West Taylor Street, Mail Code 663, Chicago, IL 60612; Lperry74@uic.edu

THE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and osteopenia was brought to the emergency department (ED) by her daughter. The woman had fallen 2 days earlier and had been experiencing a change in mental status (confusion) for the previous 4 days. Prior to her change in mental status, the patient had been independent in all activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Her daughter could not recall any symptoms of illness; new or recently changed medications; complaints of pain, constipation, diarrhea, urinary frequency, or hematuria; or changes in continence prior to the onset of her mother’s confusion.

The patient’s medications included amlodipine, atorvastatin, calcium/vitamin D, and acetaminophen (as needed). In the ED, her vital signs were normal, and her cardiopulmonary and abdominal exams were unremarkable. A limited neurologic exam showed that the patient was oriented only to person and could not answer questions about her symptoms or follow commands. She could move all of her extremities equally and could ambulate; she had no facial asymmetry or slurred speech. Her exam was negative for orthostatic hypotension.

Her complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and troponin levels were normal. Her electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with no abnormalities. X-rays of her right hip and elbow were negative for fracture. Computed tomography of her head was negative for acute findings, and a chest x-ray was normal.

Her urinalysis showed many bacteria and large leukocyte esterase, and a urine culture was sent out. She was hemodynamically stable and there were no known urinary symptoms, so no empiric antibiotics were started. She was admitted for further evaluation of her altered mental status (AMS).

On our service, she was given intravenous fluids, and oral intake was encouraged. She had normal levels of B12, folic acid, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. She was negative for HIV and syphilis. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with normal electrocardiograms and troponin levels. Her telemetry showed a normal sinus rhythm.

After 2 days, her vital signs and labs remained stable and no other abnormalities were found; however, she had not returned to her baseline mental status. Then the urine culture returned with > 105 CFU/mL of Escherichia coli, prompting a resident to curbside me (AP) and ask: “I shouldn’t treat this patient based on her urine culture—she’s just colonized, right? Or should I treat her because she’s altered?”

Continue to: THE CHALLENGE

THE CHALLENGE

Identifying and managing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in older adults often presents a challenge, further complicated if patients have AMS or cognitive impairment and are unable to confirm or deny urinary symptoms.

Consider, for instance, the definition of symptomatic UTI: significant bacteriuria (≥ 105 CFU/mL) and pyuria (> 10 WBC/hpf) with UTI-specific symptoms (fever, acute dysuria, new or worsening urgency or frequency, new urinary incontinence, gross hematuria, and suprapubic or costovertebral angle pain or tenderness).1 In older adults, these parameters require a more careful look.

For instance, while we use the cutoff of ≥ 105 CFU/mL to define “significant” bacteriuria, the truth is that we don’t know the colony count threshold that can help identify patients who are at risk of serious illness and might benefit from antibiotic treatment.2

After reviewing the culture results, clinicians then face 2 specific challenges: differentiating between acute vs chronic symptoms and related vs unrelated symptoms in the older adult population.

Challenge 1: There is a high prevalence of chronic genitourinary symptoms in older adults that can sometimes make it hard to distinguish between an acute UTI and the acute recognition of a chronic, non-UTI problem.1

Continue to: Challenge 2

Challenge 2: There is a high prevalence of multimorbidity in older adults. For instance, diuretics for heart failure can cause UTI-specific symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and even incontinence. Cognitive impairment can make it difficult to obtain the key components of the history needed to make a UTI diagnosis.1

Lastly, there are aspects of normal aging physiology that complicate the detection of infections, such as the fact that older adults may not mount a “true” fever to meet criteria for a symptomatic UTI. Therefore, fever in institutionalized or frail community-dwelling older adults has been redefined as an oral temperature ≥ 100 °F, 2 repeated oral temperatures > 99 °F, or an increase in temperature ≥ 2 °F from baseline.3

So how to proceed with our case patient? The following questions helped guide the approach to her care.

Is this patient asymptomatic?

Yes. The patient presented with nonspecific symptoms (falls and delirium) with bacteriuria suggesting asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). These symptoms are referred to as geriatric syndromes that, by definition, are “multifactorial health conditions that occur when the accumulated effects of impairments in multiple systems render an older person vulnerable to situational challenges.”4

As geriatric syndromes, falls and delirium are unlikely to be caused by one process, such as a UTI, but rather from multiple morbid processes. It is also important to note that there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

Continue to: So, while we could...

So, while we could have diagnosed a UTI in this older adult with bacteriuria and delirium, it would have been premature closure and an incomplete assessment. We would have risked potentially missing other significant causes of her delirium and unnecessarily exposing the patient to antibiotics.

Are antibiotics generally useful in older adults who you believe to be asymptomatic with a urine culture showing bacteriuria?

No. The goal of antibiotic treatment for a symptomatic UTI is to ameliorate symptoms; therefore, there is no indication for antibiotics in ASB and no evidence of survival benefit.2 And, as noted earlier, there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

The use of antibiotics in the asymptomatic setting will eradicate any bacteriuria but also increase the risk of reinfection, resistant organisms, antibiotic adverse reactions, and medication interactions.1

What is the recommendation for management of nonspecific symptoms, such as delirium and falls, in a geriatric patient such as this one with bacteriuria?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)’s 2019 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria recommends a thorough assessment (for other causes) and careful observation, rather than immediate antimicrobial treatment and cessation of evaluation for other causes.5 (IDSA made this recommendation based on low-quality evidence.) The group found a high certainty of harm and low certainty of benefit in treating older adults with antibiotics for ASB.

This recommendation highlights the key geriatric principle of “geriatric syndromes” and the multifactorial nature of findings such as delirium and falls. It encourages clinicians to continue their thorough assessment for other causes in addition to bacteriuria.5 Even in the event that antibiotics are immediately initiated, we would recommend avoiding premature closure and continuing to evaluate for other causes.

Continue to: It is reasonable to...

It is reasonable to obtain a dipstick if, after the observation period (1-7 days, with earlier follow-up for frail patients), the patient continues to have the nonspecific symptoms.1 If the dipstick is negative, there is no need for further evaluation of UTI. If it’s positive, then it’s appropriate to send for urinalysis and urine culture.1

If the urine culture is negative, continue looking for other etiologies. If it’s positive, but there is resolution of symptoms, there is no need to treat. If it’s positive and symptoms persist, consider antibiotic treatment.1

CASE RESOLUTION

The team closely monitored the patient and delayed empiric antibiotics while continuing the AMS work-up. After 2 days in the hospital, her delirium persisted, but she had no UTI-specific symptoms and she remained hemodynamically stable.

I (AP) recommended antibiotic treatment guided by the urine culture sensitivity report: initially 1 g of ceftriaxone IV q24h with transition (after symptom improvement and prior to discharge) to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg q12h, for a total of 10 days of treatment. I emphasized that we were treating bacteriuria with persisting delirium without any other etiology identified. The patient returned to her baseline mental status after a few days of treatment and was discharged home.

THE TAKEAWAY

Avoid premature closure by stopping at the diagnosis of a “UTI” in an older adult with nonspecific symptoms and bacteriuria to avoid the risk of overlooking other important and potentially life-threatening causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

L. Amanda Perry, MD, 1919 West Taylor Street, Mail Code 663, Chicago, IL 60612; Lperry74@uic.edu

1. Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:844-854. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303

2. Finucane TE. “Urinary tract infection”- requiem for a heavyweight. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1650-1655. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14907

3. Ashraf MS, Gaur S, Bushen OY, et al; Infection Advisory SubCommittee for AMDA—The Society of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of urinary tract infections in post-acute and long-term care settings: a consensus statement from AMDA’s Infection Advisory Subcommittee. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:12-24 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.004

4. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti, ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

5. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1121

1. Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:844-854. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303

2. Finucane TE. “Urinary tract infection”- requiem for a heavyweight. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1650-1655. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14907

3. Ashraf MS, Gaur S, Bushen OY, et al; Infection Advisory SubCommittee for AMDA—The Society of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of urinary tract infections in post-acute and long-term care settings: a consensus statement from AMDA’s Infection Advisory Subcommittee. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:12-24 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.004

4. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti, ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

5. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1121

Part 5: Screening for “Opathies” in Diabetes Patients

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

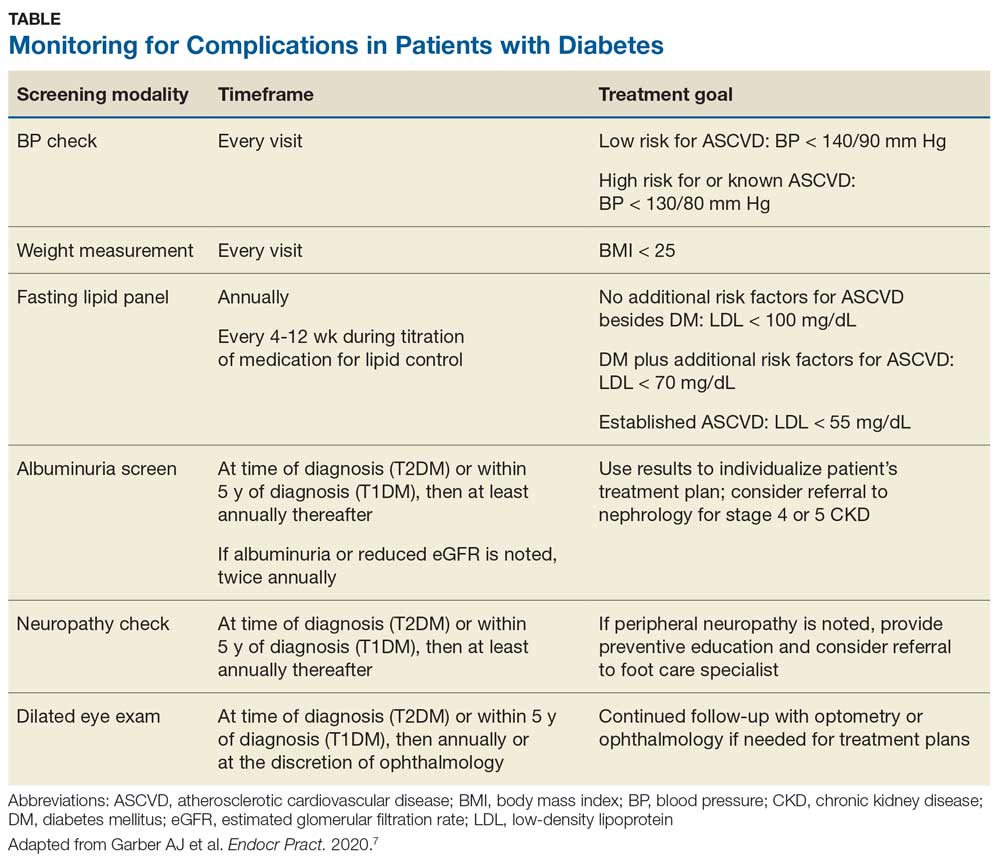

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

Part 4: Monitoring for CKD in Diabetes Patients

Previously, we discussed assessment and treatment for dyslipidemia in patients with diabetes. Now we’ll explore how to monitor for kidney disease in this population.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W’s basic metabolic panel includes an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 55 ml/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2). In the absence of any other markers of kidney disease, you obtain a spot urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). The UACR results show a ratio of 64 mg/g, confirming stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Monitoring for Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD is characterized by persistent albuminuria, low eGFR, and manifestations of kidney damage, and it increases cardiovascular risk.2 According to the ADA, clinicians should obtain a UACR and eGFR at least annually in patients who have had type 1 diabetes for at least 5 years and in all patients with type 2 diabetes.2 Monitoring is needed twice a year for those who begin to show signs of albuminuria or a reduced eGFR. This helps define the presence or stage of CKD and allows for further treatment planning.

Notably, patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2, an unclear cause of kidney disease, or signs of rapidly progressive disease (eg, decline in GFR category plus ≥ 25% decline in eGFR from baseline) should be seen by nephrology for further evaluation and treatment recommendations.2,36

Diabetes medications for kidney health. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists may be good candidates to promote kidney health in patients such as Mr. W. Recent trials show that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce the risk for progressive diabetic kidney disease, and the ADA recommends these medications for patients with CKD.2,16,36 GLP-1 receptor agonists also may be associated with a lower rate of development and progression of diabetic kidney disease, but this effect appears to be less robust.7,15,16 ADA guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for patients whose eGFR is adequate.37

ADA and AACE guidelines offer specific treatment recommendations on the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in the management of diabetes.10,37 Note that neither SGLT2 inhibitors nor GLP-1 agonists are strictly under the purview of endocrinologists. Rather, multiple guidelines state that they can be utilized safely by a variety of practitioners.6,38,39

In the concluding part of this series, we will explore how to screen for peripheral neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy—identification of which can improve the patient’s quality of life.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.