User login

When Should I Refer My CKD Patient to Nephrology?

Q) When should I refer patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to a nephrology specialist?

Nephrology specialists can be of particular assistance to primary care providers in treating patients who are at different stages of CKD.1 Nephrologists can help determine the etiology of CKD, recommend specific disease-related therapy, suggest treatments to delay disease progression in patients who have not responded to conventional therapies, recognize and treat for disease-related complications, and plan for renal replacement therapy.1

Indications for referral vary across guidelines but there is one commonality: Patients with a severely decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 require prompt referral to a nephrologist for comanaged care.1-4 Patients with CKD who have an eGFR at or below this threshold are likely at an advanced stage of disease and are therefore at greater risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis.1 Research shows that late referral to nephrology is associated with significantly higher rates of mortality within the first 90 days of dialysis.5 Furthermore, the Renal Physicians Association Clinical Practice Guideline states that patients with advanced CKD (stages 4 and 5) have a greater predisposition for quick progression to ESRD with multiple comorbid conditions and poor outcomes.6

Clinical outcomes can improve when referrals are made before patients with CKD register a low eGFR—but the appropriate threshold (or when to refer patients with a higher eGFR) is less clear.1 Based in part on practice guidelines,2,3,6,7 referral to a nephrologist or clinician with expertise in CKD should be considered for patients with CKD who meet 1 or more of the following criteria:

- Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio > 300 mg/g (34 mg/mmoL), including nephrotic syndrome

- Hematuria that is not secondary to urologic conditions

- Inability to identify a presumed cause of CKD

- eGFR decline of > 30% in less than 4 months without an obvious explanation

- Difficult-to-manage complications, such as anemia requiring erythropoietin therapy or abnormalities of bone and mineral metabolism requiring phosphorus binders or vitamin D preparations

- Serum potassium > 5.5 mEq/L

- Difficult-to-manage drug complications

- Age < 18 y

- Resistant hypertension

- Recurrent or extensive nephrolithiasis

- Confirmed or presumed hereditary kidney disease (eg, polycystic kidney disease, Alport syndrome, or autosomal dominant interstitial kidney disease).1,2,4,7

These criteria can aid clinicians in deciding when a preemptive referral is needed to prevent advanced CKD stages and ESRD in their patients. Also, because patients with CKD can be at high risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, referral to cardiology (eg, for patients with complicated cardiovascular disease) should be considered.1–YTM

Yolanda Thompson-Martin, DNP, RN, ANP-C, FNKF

University Health Physicians/Truman Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri

1. Levey AS, Inker LA. Definition and staging of chronic kidney disease in adults. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/definition-and-staging-of-chronic-kidney-disease-in-adults. Accessed January 29, 2020.

2. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J of Kidney Dis. 2002;39(suppl 1):S1-S266.

3. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(suppl 1):11-13.

4. Luxton G; Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment. The CARI Guidelines. Timing of referral of chronic kidney disease patients to nephrology services (adult). Nephrology (Carlton). 2010;15(suppl 1):S2-S11.

5. Jungers P, Massy Z, Nguyen-Khoa T, et al. Longer duration of predialysis nephrological care is associated with improved long-term survival of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(12):2357-2364.

6. WK Bolton. Renal Physicians Association Clinical Practice Guidelines: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guide line number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

7. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

Q) When should I refer patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to a nephrology specialist?

Nephrology specialists can be of particular assistance to primary care providers in treating patients who are at different stages of CKD.1 Nephrologists can help determine the etiology of CKD, recommend specific disease-related therapy, suggest treatments to delay disease progression in patients who have not responded to conventional therapies, recognize and treat for disease-related complications, and plan for renal replacement therapy.1

Indications for referral vary across guidelines but there is one commonality: Patients with a severely decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 require prompt referral to a nephrologist for comanaged care.1-4 Patients with CKD who have an eGFR at or below this threshold are likely at an advanced stage of disease and are therefore at greater risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis.1 Research shows that late referral to nephrology is associated with significantly higher rates of mortality within the first 90 days of dialysis.5 Furthermore, the Renal Physicians Association Clinical Practice Guideline states that patients with advanced CKD (stages 4 and 5) have a greater predisposition for quick progression to ESRD with multiple comorbid conditions and poor outcomes.6

Clinical outcomes can improve when referrals are made before patients with CKD register a low eGFR—but the appropriate threshold (or when to refer patients with a higher eGFR) is less clear.1 Based in part on practice guidelines,2,3,6,7 referral to a nephrologist or clinician with expertise in CKD should be considered for patients with CKD who meet 1 or more of the following criteria:

- Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio > 300 mg/g (34 mg/mmoL), including nephrotic syndrome

- Hematuria that is not secondary to urologic conditions

- Inability to identify a presumed cause of CKD

- eGFR decline of > 30% in less than 4 months without an obvious explanation

- Difficult-to-manage complications, such as anemia requiring erythropoietin therapy or abnormalities of bone and mineral metabolism requiring phosphorus binders or vitamin D preparations

- Serum potassium > 5.5 mEq/L

- Difficult-to-manage drug complications

- Age < 18 y

- Resistant hypertension

- Recurrent or extensive nephrolithiasis

- Confirmed or presumed hereditary kidney disease (eg, polycystic kidney disease, Alport syndrome, or autosomal dominant interstitial kidney disease).1,2,4,7

These criteria can aid clinicians in deciding when a preemptive referral is needed to prevent advanced CKD stages and ESRD in their patients. Also, because patients with CKD can be at high risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, referral to cardiology (eg, for patients with complicated cardiovascular disease) should be considered.1–YTM

Yolanda Thompson-Martin, DNP, RN, ANP-C, FNKF

University Health Physicians/Truman Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri

Q) When should I refer patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to a nephrology specialist?

Nephrology specialists can be of particular assistance to primary care providers in treating patients who are at different stages of CKD.1 Nephrologists can help determine the etiology of CKD, recommend specific disease-related therapy, suggest treatments to delay disease progression in patients who have not responded to conventional therapies, recognize and treat for disease-related complications, and plan for renal replacement therapy.1

Indications for referral vary across guidelines but there is one commonality: Patients with a severely decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 require prompt referral to a nephrologist for comanaged care.1-4 Patients with CKD who have an eGFR at or below this threshold are likely at an advanced stage of disease and are therefore at greater risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis.1 Research shows that late referral to nephrology is associated with significantly higher rates of mortality within the first 90 days of dialysis.5 Furthermore, the Renal Physicians Association Clinical Practice Guideline states that patients with advanced CKD (stages 4 and 5) have a greater predisposition for quick progression to ESRD with multiple comorbid conditions and poor outcomes.6

Clinical outcomes can improve when referrals are made before patients with CKD register a low eGFR—but the appropriate threshold (or when to refer patients with a higher eGFR) is less clear.1 Based in part on practice guidelines,2,3,6,7 referral to a nephrologist or clinician with expertise in CKD should be considered for patients with CKD who meet 1 or more of the following criteria:

- Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio > 300 mg/g (34 mg/mmoL), including nephrotic syndrome

- Hematuria that is not secondary to urologic conditions

- Inability to identify a presumed cause of CKD

- eGFR decline of > 30% in less than 4 months without an obvious explanation

- Difficult-to-manage complications, such as anemia requiring erythropoietin therapy or abnormalities of bone and mineral metabolism requiring phosphorus binders or vitamin D preparations

- Serum potassium > 5.5 mEq/L

- Difficult-to-manage drug complications

- Age < 18 y

- Resistant hypertension

- Recurrent or extensive nephrolithiasis

- Confirmed or presumed hereditary kidney disease (eg, polycystic kidney disease, Alport syndrome, or autosomal dominant interstitial kidney disease).1,2,4,7

These criteria can aid clinicians in deciding when a preemptive referral is needed to prevent advanced CKD stages and ESRD in their patients. Also, because patients with CKD can be at high risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, referral to cardiology (eg, for patients with complicated cardiovascular disease) should be considered.1–YTM

Yolanda Thompson-Martin, DNP, RN, ANP-C, FNKF

University Health Physicians/Truman Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri

1. Levey AS, Inker LA. Definition and staging of chronic kidney disease in adults. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/definition-and-staging-of-chronic-kidney-disease-in-adults. Accessed January 29, 2020.

2. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J of Kidney Dis. 2002;39(suppl 1):S1-S266.

3. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(suppl 1):11-13.

4. Luxton G; Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment. The CARI Guidelines. Timing of referral of chronic kidney disease patients to nephrology services (adult). Nephrology (Carlton). 2010;15(suppl 1):S2-S11.

5. Jungers P, Massy Z, Nguyen-Khoa T, et al. Longer duration of predialysis nephrological care is associated with improved long-term survival of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(12):2357-2364.

6. WK Bolton. Renal Physicians Association Clinical Practice Guidelines: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guide line number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

7. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

1. Levey AS, Inker LA. Definition and staging of chronic kidney disease in adults. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/definition-and-staging-of-chronic-kidney-disease-in-adults. Accessed January 29, 2020.

2. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J of Kidney Dis. 2002;39(suppl 1):S1-S266.

3. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(suppl 1):11-13.

4. Luxton G; Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment. The CARI Guidelines. Timing of referral of chronic kidney disease patients to nephrology services (adult). Nephrology (Carlton). 2010;15(suppl 1):S2-S11.

5. Jungers P, Massy Z, Nguyen-Khoa T, et al. Longer duration of predialysis nephrological care is associated with improved long-term survival of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(12):2357-2364.

6. WK Bolton. Renal Physicians Association Clinical Practice Guidelines: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guide line number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

7. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

Proteinuria and Albuminuria: What’s the Difference?

Q)What exactly is the difference between the protein-to-creatinine ratio and the microalbumin in the lab report? How do they compare?

For the non-nephrology provider, the options for evaluating urine protein or albumin can seem confusing. The first thing to understand is the importance of assessing for proteinuria, an established marker for chronic kidney disease (CKD). Higher protein levels are associated with more rapid progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease and increased risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in both the nondiabetic and diabetic populations. Monitoring proteinuria levels can also aid in evaluating response to treatment.1

Proteinuria and albuminuria are not the same thing. Proteinuria indicates an elevated presence of protein in the urine (normal excretion should be < 150 mg/d), while al

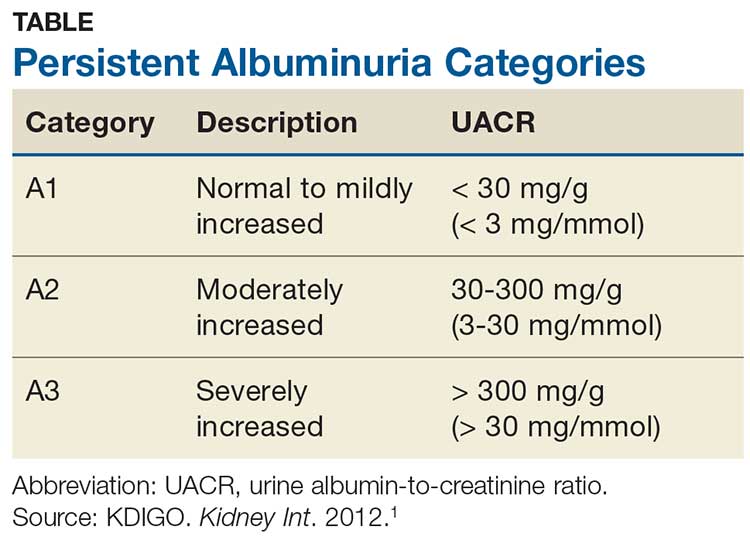

Albuminuria, without or with a reduction in estimated GFR (eGFR), lasting > 3 months is considered a marker of kidney damage. There are 3 categories of persistent albuminuria (see Table).1 Staging of CKD depends on both the eGFR and the albuminuria category; the results affect treatment considerations.

While there are several ways to assess for proteinuria, their accuracy varies. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline on the evaluation and management of CKD recommends the spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) as the preferred test for both initial and follow-up testing. While the UACR is typically reported as mg/g, it can also be reported in mg/mmol.1 Other options include the spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and a manual reading of a reagent strip (urine dipstick test) for total protein. Only if the first 2 choices are unavailable should a provider consider using a dipstick.

Reagent strip urinalysis may assess for protein or more specifically for albumin; tests for the latter are becoming more common. These tests are often used in a clinic setting, with results typically reported in the protein testing section. It is important to know which reagent strip urinalysis you are using (protein vs albumin) and how this is being reported. Additionally, test results depend on the urine concentration: Concentrated samples are more likely to indicate higher levels than may actually be present, while dilute samples may test negative (or positive for a trace amount) when in reality higher levels are present.

If a reagent strip urinalysis tests positive for protein, confirmatory testing is recommended using the UACR or the UPCR (if the former is not an option). A 24-hour urine screen for total protein excretion or an albumin excretion rate can be obtained if there are concerns about the accuracy of the previously discussed tests. A urine albumin excretion rate ≥ 30 mg/24 h corresponds to a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g (≥ 3 mg/mmol).1 Although 24-hour urine has been considered the gold standard, it is used less frequently today due to potential for improper sample collection, which can negatively affect accuracy, and inconvenience to patients.2

As a final note, if there is suspicion for nonalbumin proteinuria (eg, when increased plasma levels of low-molecular-weight proteins or immunoglobulin light chains are present), testing for specific urine proteins is recommended. This can include assessment with urine protein electrophoresis.1 —CS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN, FNKF

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

2. Ying T, Clayton P, Naresh C, Chadban S. Predictive value of spot versus 24-hour measures of proteinuria for death, end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease progression. BMC Nephrology. 2018;19:55.

Q)What exactly is the difference between the protein-to-creatinine ratio and the microalbumin in the lab report? How do they compare?

For the non-nephrology provider, the options for evaluating urine protein or albumin can seem confusing. The first thing to understand is the importance of assessing for proteinuria, an established marker for chronic kidney disease (CKD). Higher protein levels are associated with more rapid progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease and increased risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in both the nondiabetic and diabetic populations. Monitoring proteinuria levels can also aid in evaluating response to treatment.1

Proteinuria and albuminuria are not the same thing. Proteinuria indicates an elevated presence of protein in the urine (normal excretion should be < 150 mg/d), while al

Albuminuria, without or with a reduction in estimated GFR (eGFR), lasting > 3 months is considered a marker of kidney damage. There are 3 categories of persistent albuminuria (see Table).1 Staging of CKD depends on both the eGFR and the albuminuria category; the results affect treatment considerations.

While there are several ways to assess for proteinuria, their accuracy varies. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline on the evaluation and management of CKD recommends the spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) as the preferred test for both initial and follow-up testing. While the UACR is typically reported as mg/g, it can also be reported in mg/mmol.1 Other options include the spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and a manual reading of a reagent strip (urine dipstick test) for total protein. Only if the first 2 choices are unavailable should a provider consider using a dipstick.

Reagent strip urinalysis may assess for protein or more specifically for albumin; tests for the latter are becoming more common. These tests are often used in a clinic setting, with results typically reported in the protein testing section. It is important to know which reagent strip urinalysis you are using (protein vs albumin) and how this is being reported. Additionally, test results depend on the urine concentration: Concentrated samples are more likely to indicate higher levels than may actually be present, while dilute samples may test negative (or positive for a trace amount) when in reality higher levels are present.

If a reagent strip urinalysis tests positive for protein, confirmatory testing is recommended using the UACR or the UPCR (if the former is not an option). A 24-hour urine screen for total protein excretion or an albumin excretion rate can be obtained if there are concerns about the accuracy of the previously discussed tests. A urine albumin excretion rate ≥ 30 mg/24 h corresponds to a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g (≥ 3 mg/mmol).1 Although 24-hour urine has been considered the gold standard, it is used less frequently today due to potential for improper sample collection, which can negatively affect accuracy, and inconvenience to patients.2

As a final note, if there is suspicion for nonalbumin proteinuria (eg, when increased plasma levels of low-molecular-weight proteins or immunoglobulin light chains are present), testing for specific urine proteins is recommended. This can include assessment with urine protein electrophoresis.1 —CS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN, FNKF

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

Q)What exactly is the difference between the protein-to-creatinine ratio and the microalbumin in the lab report? How do they compare?

For the non-nephrology provider, the options for evaluating urine protein or albumin can seem confusing. The first thing to understand is the importance of assessing for proteinuria, an established marker for chronic kidney disease (CKD). Higher protein levels are associated with more rapid progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease and increased risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in both the nondiabetic and diabetic populations. Monitoring proteinuria levels can also aid in evaluating response to treatment.1

Proteinuria and albuminuria are not the same thing. Proteinuria indicates an elevated presence of protein in the urine (normal excretion should be < 150 mg/d), while al

Albuminuria, without or with a reduction in estimated GFR (eGFR), lasting > 3 months is considered a marker of kidney damage. There are 3 categories of persistent albuminuria (see Table).1 Staging of CKD depends on both the eGFR and the albuminuria category; the results affect treatment considerations.

While there are several ways to assess for proteinuria, their accuracy varies. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline on the evaluation and management of CKD recommends the spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) as the preferred test for both initial and follow-up testing. While the UACR is typically reported as mg/g, it can also be reported in mg/mmol.1 Other options include the spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and a manual reading of a reagent strip (urine dipstick test) for total protein. Only if the first 2 choices are unavailable should a provider consider using a dipstick.

Reagent strip urinalysis may assess for protein or more specifically for albumin; tests for the latter are becoming more common. These tests are often used in a clinic setting, with results typically reported in the protein testing section. It is important to know which reagent strip urinalysis you are using (protein vs albumin) and how this is being reported. Additionally, test results depend on the urine concentration: Concentrated samples are more likely to indicate higher levels than may actually be present, while dilute samples may test negative (or positive for a trace amount) when in reality higher levels are present.

If a reagent strip urinalysis tests positive for protein, confirmatory testing is recommended using the UACR or the UPCR (if the former is not an option). A 24-hour urine screen for total protein excretion or an albumin excretion rate can be obtained if there are concerns about the accuracy of the previously discussed tests. A urine albumin excretion rate ≥ 30 mg/24 h corresponds to a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g (≥ 3 mg/mmol).1 Although 24-hour urine has been considered the gold standard, it is used less frequently today due to potential for improper sample collection, which can negatively affect accuracy, and inconvenience to patients.2

As a final note, if there is suspicion for nonalbumin proteinuria (eg, when increased plasma levels of low-molecular-weight proteins or immunoglobulin light chains are present), testing for specific urine proteins is recommended. This can include assessment with urine protein electrophoresis.1 —CS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN, FNKF

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

2. Ying T, Clayton P, Naresh C, Chadban S. Predictive value of spot versus 24-hour measures of proteinuria for death, end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease progression. BMC Nephrology. 2018;19:55.

1. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

2. Ying T, Clayton P, Naresh C, Chadban S. Predictive value of spot versus 24-hour measures of proteinuria for death, end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease progression. BMC Nephrology. 2018;19:55.

Acute Kidney Injury: Treatment Depends on the Cause

Q)I have a patient with a discharge diagnosis of community-acquired acute kidney injury. What does this mean? What do I do now?

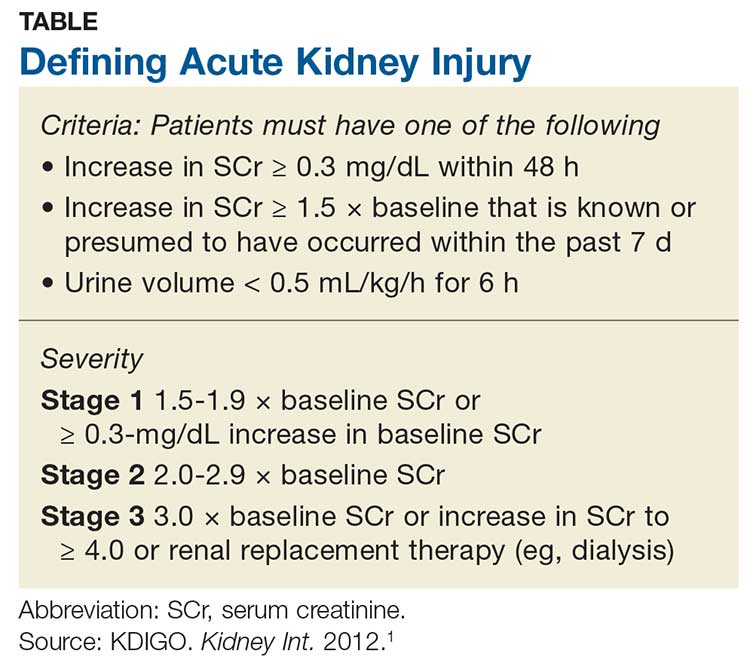

Acute kidney injury (AKI) refers to an abrupt decrease in kidney function that is possibly reversible or in which harm to the kidney can be modified.1,2 AKI encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions affecting the kidney—including acute renal failure, since even “failure” can sometimes be reversed.1 Criteria for AKI and its severity can be found in the Table.1

AKI can be either community-acquired (CA-AKI) or hospital-acquired (HA-AKI).1,2 In the United States, CA-AKI occurs less frequently than HA-AKI, although cases are likely underreported.1 Evaluation and management are similar for both.

The etiology of the AKI must be determined before treatment of the cause or precipitating factor can be attempted. Causes of AKI can be classified as prerenal (up to 70% of cases), intrinsic, or postrenal.1

Most AKI cases have a prerenal origin.3 Prerenal AKI occurs when there is inadequate blood flow to the kidneys, leading to a rise in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels. Reduced blood flow can be caused by

- Diuretic dosing

- Polypharmacy (diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs]/ angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], and/or NSAIDs are common culprits)

- Congestive heart failure exacerbation

- Volume depletion through vomiting or diarrhea

- Massive blood loss (trauma).3

Postrenal causes of AKI include any type of obstructive uropathy. Intrinsic causes involve any condition within the kidney, including interstitial nephritis or acute tubular necrosis. Use of antibiotics (eg, high-dose penicillin or vancomycin) is included in this category.

Obtaining an accurate medical history and examining the patient’s fluid status are critical. Although numerous novel biomarkers have been investigated for detection of AKI, none are yet in wide use. The primary assessment measures remain a serum panel to evaluate SCr and BUN levels; an electrolyte panel to assess for abnormalities; a complete blood count to assess for anemia caused by a less likely source; urinalysis; and imaging to assess for abnormalities or structural changes.

Urinalysis. Urine often holds the key to diagnosis of AKI. Notably in a prerenal injury, its specific gravity will be elevated, but the rest of the urine will likely be bland.3

Continue to: Urinalysis is helpful for...

Urinalysis is helpful for ruling out intrinsic causes of AKI. Patients with intrarenal AKI will have abnormal urine sediment; for example, red blood cell casts are found in glomerulonephritis; granular casts in cases of acute tubular necrosis; and white blood cell casts and eosinophils in acute interstitial nephritis.4

Imaging. The most commonly used imaging for AKI is retroperitoneal ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, which provides information on the size and shape of the kidneys and can detect stones or masses. It also detects the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, which can occur in postrenal injuries.

Currently, no definitive therapy or pharmacologic agent is approved for AKI; treatment focuses on reversing the cause of the injury. In the immediate aftermath of AKI, it is important to avoid potentially nephrotoxic medications, including NSAIDs. Minimize the use of diuretics and avoid ACEIs and ARB therapy; these can be reintroduced after lab results confirm that the AKI has resolved with a stabilized SCr.

Practice guidelines recommend prompt follow-up at 3 months in most cases of AKI.1 Providers should obtain a metabolic panel and perform a urinalysis to evaluate for chronic kidney disease (CKD), because almost one-third of patients with an AKI episode are newly classified with CKD in the following year.5 Earlier follow-up (< 3 months) is warranted if the patient has a significant comorbidity, such as congestive heart failure.1,2—CS

Christopher Sjoberg, CNN-NP

Idaho Nephrology Associates, Boise

Adjunct Faculty, Boise State University

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(suppl):1-138.

2. Palevsky PM, Liu KD, Brophy PD, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):649-672.

3. Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2012; 380(9843):756-766.

4. Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Disease. 7thed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

5. United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018.

Q)I have a patient with a discharge diagnosis of community-acquired acute kidney injury. What does this mean? What do I do now?

Acute kidney injury (AKI) refers to an abrupt decrease in kidney function that is possibly reversible or in which harm to the kidney can be modified.1,2 AKI encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions affecting the kidney—including acute renal failure, since even “failure” can sometimes be reversed.1 Criteria for AKI and its severity can be found in the Table.1

AKI can be either community-acquired (CA-AKI) or hospital-acquired (HA-AKI).1,2 In the United States, CA-AKI occurs less frequently than HA-AKI, although cases are likely underreported.1 Evaluation and management are similar for both.

The etiology of the AKI must be determined before treatment of the cause or precipitating factor can be attempted. Causes of AKI can be classified as prerenal (up to 70% of cases), intrinsic, or postrenal.1

Most AKI cases have a prerenal origin.3 Prerenal AKI occurs when there is inadequate blood flow to the kidneys, leading to a rise in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels. Reduced blood flow can be caused by

- Diuretic dosing

- Polypharmacy (diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs]/ angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], and/or NSAIDs are common culprits)

- Congestive heart failure exacerbation

- Volume depletion through vomiting or diarrhea

- Massive blood loss (trauma).3

Postrenal causes of AKI include any type of obstructive uropathy. Intrinsic causes involve any condition within the kidney, including interstitial nephritis or acute tubular necrosis. Use of antibiotics (eg, high-dose penicillin or vancomycin) is included in this category.

Obtaining an accurate medical history and examining the patient’s fluid status are critical. Although numerous novel biomarkers have been investigated for detection of AKI, none are yet in wide use. The primary assessment measures remain a serum panel to evaluate SCr and BUN levels; an electrolyte panel to assess for abnormalities; a complete blood count to assess for anemia caused by a less likely source; urinalysis; and imaging to assess for abnormalities or structural changes.

Urinalysis. Urine often holds the key to diagnosis of AKI. Notably in a prerenal injury, its specific gravity will be elevated, but the rest of the urine will likely be bland.3

Continue to: Urinalysis is helpful for...

Urinalysis is helpful for ruling out intrinsic causes of AKI. Patients with intrarenal AKI will have abnormal urine sediment; for example, red blood cell casts are found in glomerulonephritis; granular casts in cases of acute tubular necrosis; and white blood cell casts and eosinophils in acute interstitial nephritis.4

Imaging. The most commonly used imaging for AKI is retroperitoneal ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, which provides information on the size and shape of the kidneys and can detect stones or masses. It also detects the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, which can occur in postrenal injuries.

Currently, no definitive therapy or pharmacologic agent is approved for AKI; treatment focuses on reversing the cause of the injury. In the immediate aftermath of AKI, it is important to avoid potentially nephrotoxic medications, including NSAIDs. Minimize the use of diuretics and avoid ACEIs and ARB therapy; these can be reintroduced after lab results confirm that the AKI has resolved with a stabilized SCr.

Practice guidelines recommend prompt follow-up at 3 months in most cases of AKI.1 Providers should obtain a metabolic panel and perform a urinalysis to evaluate for chronic kidney disease (CKD), because almost one-third of patients with an AKI episode are newly classified with CKD in the following year.5 Earlier follow-up (< 3 months) is warranted if the patient has a significant comorbidity, such as congestive heart failure.1,2—CS

Christopher Sjoberg, CNN-NP

Idaho Nephrology Associates, Boise

Adjunct Faculty, Boise State University

Q)I have a patient with a discharge diagnosis of community-acquired acute kidney injury. What does this mean? What do I do now?

Acute kidney injury (AKI) refers to an abrupt decrease in kidney function that is possibly reversible or in which harm to the kidney can be modified.1,2 AKI encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions affecting the kidney—including acute renal failure, since even “failure” can sometimes be reversed.1 Criteria for AKI and its severity can be found in the Table.1

AKI can be either community-acquired (CA-AKI) or hospital-acquired (HA-AKI).1,2 In the United States, CA-AKI occurs less frequently than HA-AKI, although cases are likely underreported.1 Evaluation and management are similar for both.

The etiology of the AKI must be determined before treatment of the cause or precipitating factor can be attempted. Causes of AKI can be classified as prerenal (up to 70% of cases), intrinsic, or postrenal.1

Most AKI cases have a prerenal origin.3 Prerenal AKI occurs when there is inadequate blood flow to the kidneys, leading to a rise in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels. Reduced blood flow can be caused by

- Diuretic dosing

- Polypharmacy (diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs]/ angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], and/or NSAIDs are common culprits)

- Congestive heart failure exacerbation

- Volume depletion through vomiting or diarrhea

- Massive blood loss (trauma).3

Postrenal causes of AKI include any type of obstructive uropathy. Intrinsic causes involve any condition within the kidney, including interstitial nephritis or acute tubular necrosis. Use of antibiotics (eg, high-dose penicillin or vancomycin) is included in this category.

Obtaining an accurate medical history and examining the patient’s fluid status are critical. Although numerous novel biomarkers have been investigated for detection of AKI, none are yet in wide use. The primary assessment measures remain a serum panel to evaluate SCr and BUN levels; an electrolyte panel to assess for abnormalities; a complete blood count to assess for anemia caused by a less likely source; urinalysis; and imaging to assess for abnormalities or structural changes.

Urinalysis. Urine often holds the key to diagnosis of AKI. Notably in a prerenal injury, its specific gravity will be elevated, but the rest of the urine will likely be bland.3

Continue to: Urinalysis is helpful for...

Urinalysis is helpful for ruling out intrinsic causes of AKI. Patients with intrarenal AKI will have abnormal urine sediment; for example, red blood cell casts are found in glomerulonephritis; granular casts in cases of acute tubular necrosis; and white blood cell casts and eosinophils in acute interstitial nephritis.4

Imaging. The most commonly used imaging for AKI is retroperitoneal ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, which provides information on the size and shape of the kidneys and can detect stones or masses. It also detects the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, which can occur in postrenal injuries.

Currently, no definitive therapy or pharmacologic agent is approved for AKI; treatment focuses on reversing the cause of the injury. In the immediate aftermath of AKI, it is important to avoid potentially nephrotoxic medications, including NSAIDs. Minimize the use of diuretics and avoid ACEIs and ARB therapy; these can be reintroduced after lab results confirm that the AKI has resolved with a stabilized SCr.

Practice guidelines recommend prompt follow-up at 3 months in most cases of AKI.1 Providers should obtain a metabolic panel and perform a urinalysis to evaluate for chronic kidney disease (CKD), because almost one-third of patients with an AKI episode are newly classified with CKD in the following year.5 Earlier follow-up (< 3 months) is warranted if the patient has a significant comorbidity, such as congestive heart failure.1,2—CS

Christopher Sjoberg, CNN-NP

Idaho Nephrology Associates, Boise

Adjunct Faculty, Boise State University

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(suppl):1-138.

2. Palevsky PM, Liu KD, Brophy PD, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):649-672.

3. Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2012; 380(9843):756-766.

4. Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Disease. 7thed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

5. United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018.

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(suppl):1-138.

2. Palevsky PM, Liu KD, Brophy PD, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):649-672.

3. Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2012; 380(9843):756-766.

4. Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Disease. 7thed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

5. United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018.

Bone Health in Kidney Disease

Q) What are the current recommendations for the use of DXA and bisphosphonates in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease?

For patients with kidney disease, mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is a common complication, affecting the majority of those with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (CKD; see Table 1).1,2 CKD-MBD is a systemic disorder that encompasses abnormalities in mineral metabolism, skeletal health, and soft-tissue calcifications.1,2 It manifests as one or more of the following:

- Abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), or vitamin D metabolism

- Abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth, or strength

- Vascular or other soft-tissue calcification.2

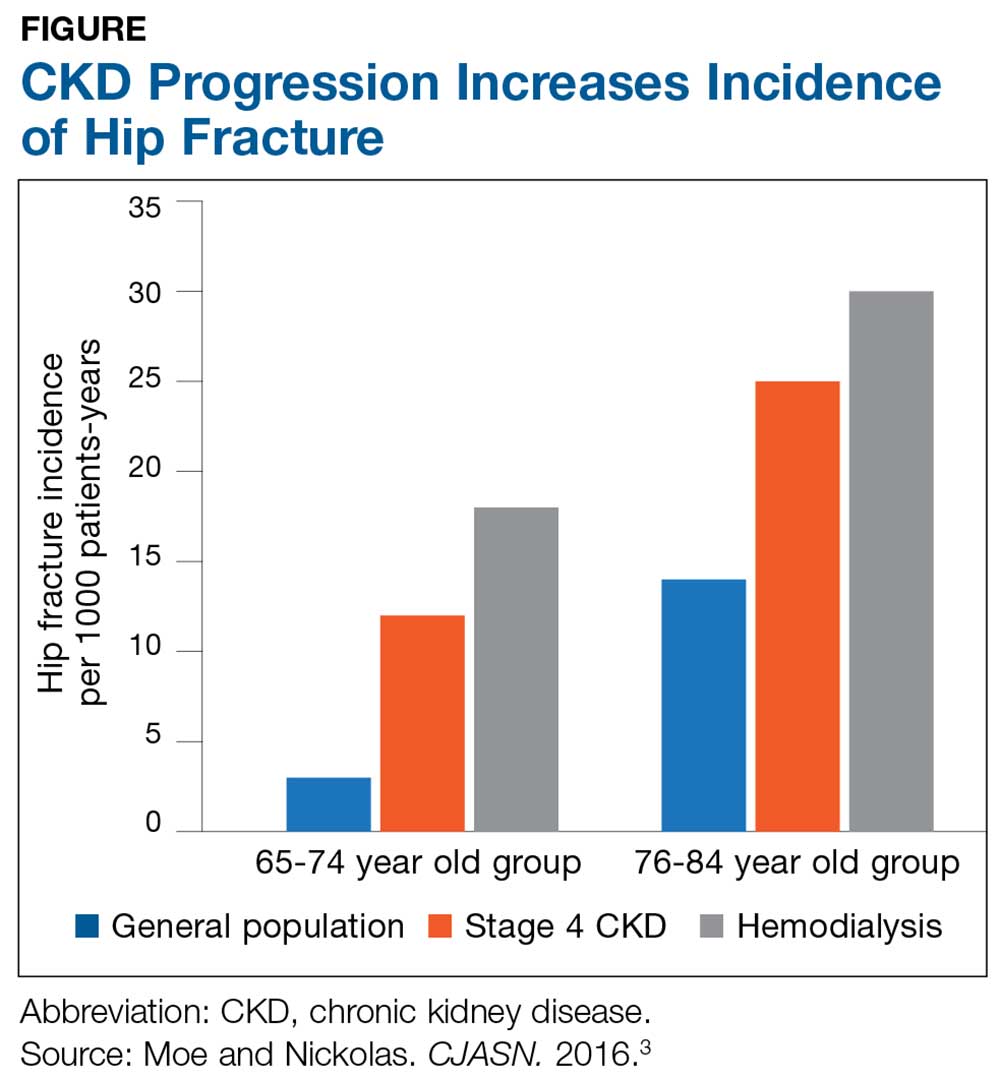

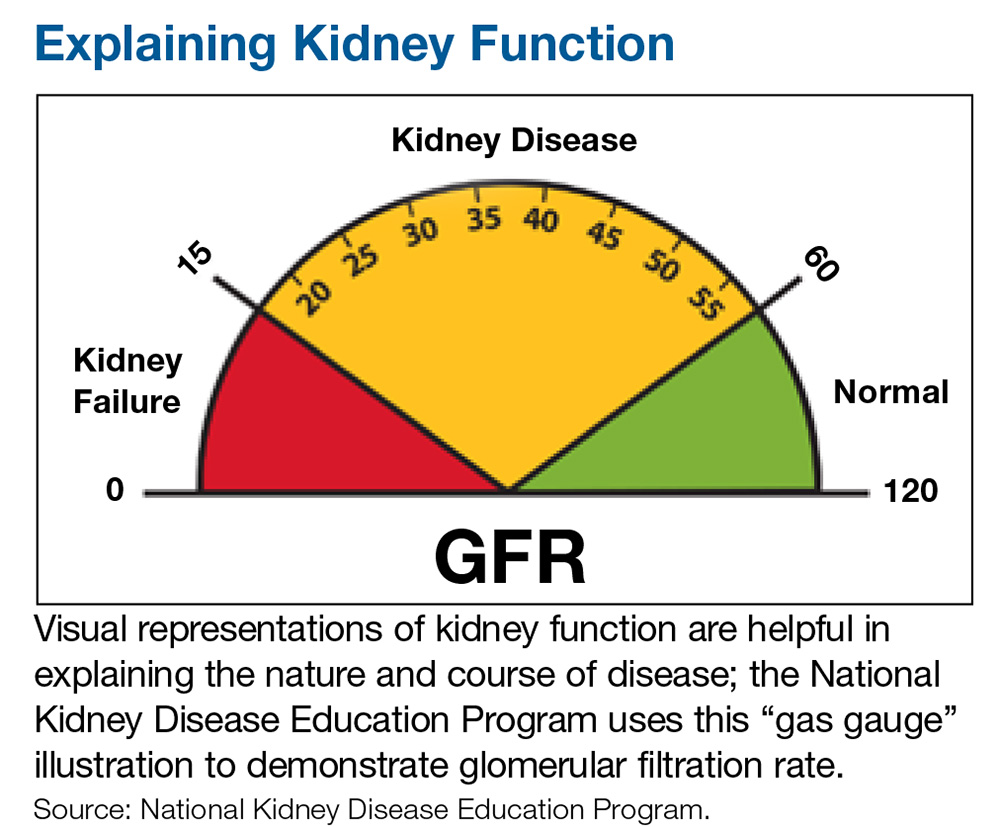

The Figure provides an illustration of the effect of CKD on bone health: In the general population, risk for hip fracture increases with age; risk is further exacerbated in those who have CKD.3

To assess for fracture risk in patients with advanced stages of CKD (3-5) who have evidence of CKD-MBD and/or risk factors for osteoporosis, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) group recommends bone mineral density testing with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).2 Bone biopsy—the gold standard for diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy, a form of osteoporosis and one type of bone abnormality seen in CKD-MBD—is “reasonable” to perform in cases in which knowing the type of renal osteodystrophy would inform treatment choices.2 KDIGO also recognizes limitations in the ability to perform a bone biopsy and therefore recommends monitoring serial PTH and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase to evaluate for bone disease.2

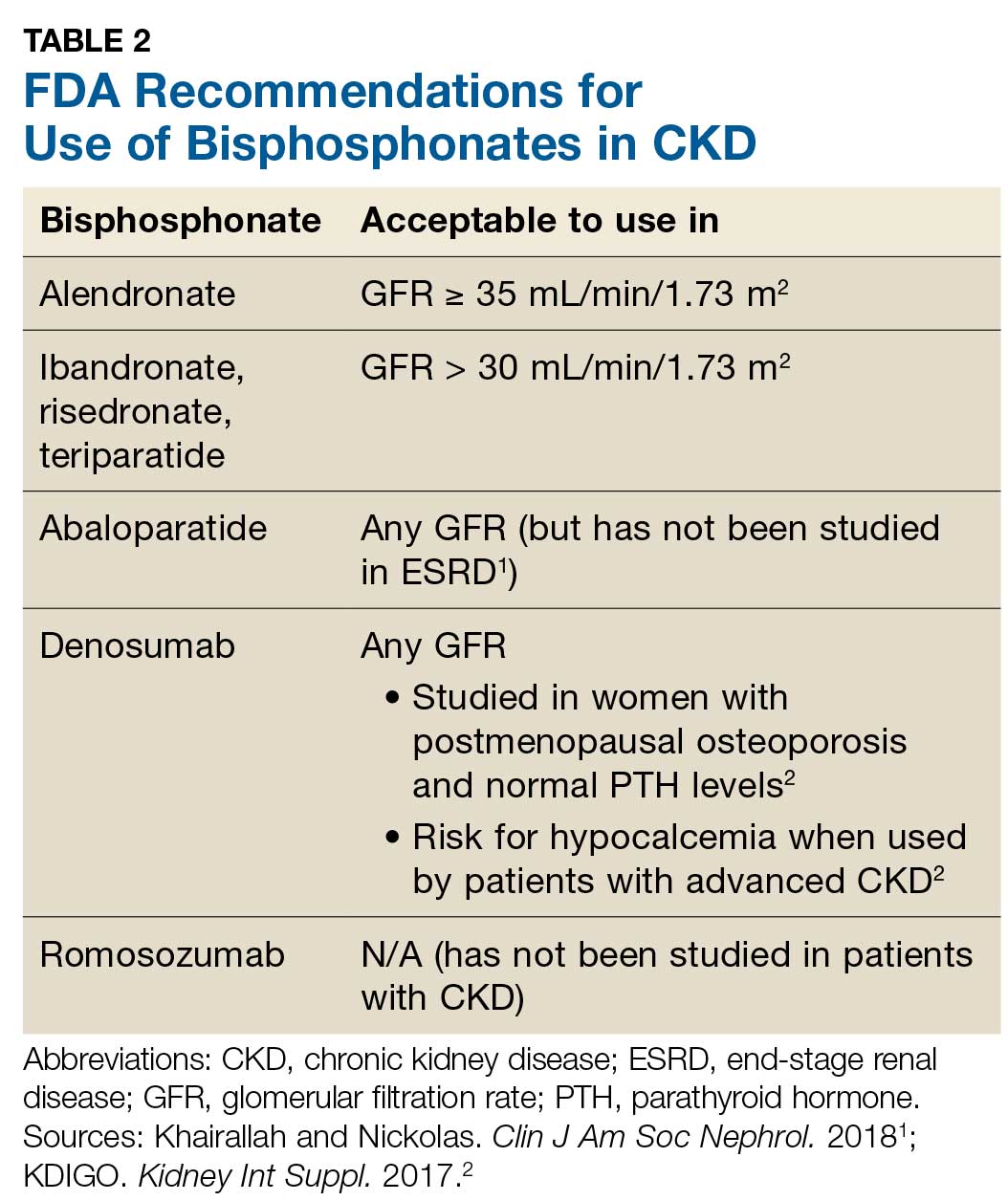

Prevention of fractures and treatment of patients with CKD-MDB has historically been challenging, since many of the available pharmacologic agents have not been developed for or studied in patients with CKD.1 According to KDIGO, it is acceptable for patients with CKD stages 1 and 2 to receive the same osteoporosis/fracture risk management as recommended for the general population.2 Patients with CKD stages 3a and 3b can also receive treatment as recommended for the general population, as long as the patient’s PTH level is in normal range.2 Table 2 outlines the FDA-approved glomerular filtration rate cutoffs for some bisphosphonates commonly used to treat osteoporosis.

Before initiating treatment for CKD-associated osteoporosis, no matter what the stage, it is important to manage vitamin D deficiency, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism.1 In CKD patients with abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and/or vitamin D, involve the nephrology team to assist in providing MBD care. Different approaches to treatment may include, but are not limited to, adjusting phosphorus binders; using vitamin D supplements or analogs; using calcimimetics; prescribing dialysis; providing dietary education; and addressing medication costs.

1. Khairallah P, Nickolas TL. Management of osteoporosis in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(6):962-969.

2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:1-59.

3. Moe SM, Nickolas TL. Fractures in patients with CKD: time for action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(11):1929-1931.

Q) What are the current recommendations for the use of DXA and bisphosphonates in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease?

For patients with kidney disease, mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is a common complication, affecting the majority of those with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (CKD; see Table 1).1,2 CKD-MBD is a systemic disorder that encompasses abnormalities in mineral metabolism, skeletal health, and soft-tissue calcifications.1,2 It manifests as one or more of the following:

- Abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), or vitamin D metabolism

- Abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth, or strength

- Vascular or other soft-tissue calcification.2

The Figure provides an illustration of the effect of CKD on bone health: In the general population, risk for hip fracture increases with age; risk is further exacerbated in those who have CKD.3

To assess for fracture risk in patients with advanced stages of CKD (3-5) who have evidence of CKD-MBD and/or risk factors for osteoporosis, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) group recommends bone mineral density testing with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).2 Bone biopsy—the gold standard for diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy, a form of osteoporosis and one type of bone abnormality seen in CKD-MBD—is “reasonable” to perform in cases in which knowing the type of renal osteodystrophy would inform treatment choices.2 KDIGO also recognizes limitations in the ability to perform a bone biopsy and therefore recommends monitoring serial PTH and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase to evaluate for bone disease.2

Prevention of fractures and treatment of patients with CKD-MDB has historically been challenging, since many of the available pharmacologic agents have not been developed for or studied in patients with CKD.1 According to KDIGO, it is acceptable for patients with CKD stages 1 and 2 to receive the same osteoporosis/fracture risk management as recommended for the general population.2 Patients with CKD stages 3a and 3b can also receive treatment as recommended for the general population, as long as the patient’s PTH level is in normal range.2 Table 2 outlines the FDA-approved glomerular filtration rate cutoffs for some bisphosphonates commonly used to treat osteoporosis.

Before initiating treatment for CKD-associated osteoporosis, no matter what the stage, it is important to manage vitamin D deficiency, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism.1 In CKD patients with abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and/or vitamin D, involve the nephrology team to assist in providing MBD care. Different approaches to treatment may include, but are not limited to, adjusting phosphorus binders; using vitamin D supplements or analogs; using calcimimetics; prescribing dialysis; providing dietary education; and addressing medication costs.

Q) What are the current recommendations for the use of DXA and bisphosphonates in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease?

For patients with kidney disease, mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is a common complication, affecting the majority of those with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (CKD; see Table 1).1,2 CKD-MBD is a systemic disorder that encompasses abnormalities in mineral metabolism, skeletal health, and soft-tissue calcifications.1,2 It manifests as one or more of the following:

- Abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), or vitamin D metabolism

- Abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth, or strength

- Vascular or other soft-tissue calcification.2

The Figure provides an illustration of the effect of CKD on bone health: In the general population, risk for hip fracture increases with age; risk is further exacerbated in those who have CKD.3

To assess for fracture risk in patients with advanced stages of CKD (3-5) who have evidence of CKD-MBD and/or risk factors for osteoporosis, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) group recommends bone mineral density testing with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).2 Bone biopsy—the gold standard for diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy, a form of osteoporosis and one type of bone abnormality seen in CKD-MBD—is “reasonable” to perform in cases in which knowing the type of renal osteodystrophy would inform treatment choices.2 KDIGO also recognizes limitations in the ability to perform a bone biopsy and therefore recommends monitoring serial PTH and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase to evaluate for bone disease.2

Prevention of fractures and treatment of patients with CKD-MDB has historically been challenging, since many of the available pharmacologic agents have not been developed for or studied in patients with CKD.1 According to KDIGO, it is acceptable for patients with CKD stages 1 and 2 to receive the same osteoporosis/fracture risk management as recommended for the general population.2 Patients with CKD stages 3a and 3b can also receive treatment as recommended for the general population, as long as the patient’s PTH level is in normal range.2 Table 2 outlines the FDA-approved glomerular filtration rate cutoffs for some bisphosphonates commonly used to treat osteoporosis.

Before initiating treatment for CKD-associated osteoporosis, no matter what the stage, it is important to manage vitamin D deficiency, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism.1 In CKD patients with abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and/or vitamin D, involve the nephrology team to assist in providing MBD care. Different approaches to treatment may include, but are not limited to, adjusting phosphorus binders; using vitamin D supplements or analogs; using calcimimetics; prescribing dialysis; providing dietary education; and addressing medication costs.

1. Khairallah P, Nickolas TL. Management of osteoporosis in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(6):962-969.

2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:1-59.

3. Moe SM, Nickolas TL. Fractures in patients with CKD: time for action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(11):1929-1931.

1. Khairallah P, Nickolas TL. Management of osteoporosis in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(6):962-969.

2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:1-59.

3. Moe SM, Nickolas TL. Fractures in patients with CKD: time for action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(11):1929-1931.

When Can You Stop Dialysis?

Q) When my patient was told that she needed dialysis, one of her first questions was, "For how long?" Which got me thinking: How often do dialysis patients regain kidney function? Are some more likely than others to be able to stop dialysis?

Diagnosis with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis, is a life-changing event. Inevitably, patients ask about their chance of recovery and the likelihood of stopping dialysis. Studies have consistently demonstrated low rates of kidney recovery, ranging from 0.9% to 2.4%.1

According to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), from 1995-2006 only 0.9% of ESRD patients regained kidney function resulting in the discontinuation of dialysis.2 In one study, Agraharkar and colleagues reviewed the medical records and lab results of patients discharged from a chronic dialysis unit and reported a 1% to 2% rate of kidney recovery. The researchers concluded that closer monitoring of residual kidney function was key to identification of patients with a greater chance of recovery.3 Chu and Folkert noted a recovery rate of 1.0% to 2.4% in a review of large observational studies, concluding that the underlying etiology of the kidney failure was the single most important predictor.4

Another study of approximately 194,000 patients who started dialysis between 2008-2009 demonstrated much higher rates of sustained recovery: up to 5%. This study showed that patients with kidney failure associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) were more likely to achieve recovery; patients with the AKI diagnosis of acute tubular necrosis had the highest rate of recovery.1

Similar studies of pediatric patients are rare. One European study followed 6,574 children who started dialysis before age 15. Within 2 years of dialysis initiation, just 2% showed kidney function recovery. This study also identified underlying etiology as an important predictor of recovery; ischemic kidney failure, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and vasculitis were associated with the greatest chance of recovery.5

Despite these recent findings, the prospect of discontinuation of dialysis with a diagnosis of ESRD remains very low. A patient's underlying etiology influences the possibility of recovery; those with AKI tend to have the greatest chance, making close monitoring of residual kidney function essential in this population.3 — MSG

Marlene Shaw-Gallagher, PA-C

Nephrology Division of Michigan Medicine

Assistant Professor at University of Detroit Mercy

1. Mohan S, Huff E, Wish J, et al. Recovery of renal function among ESRD patients in the US Medicare program. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83447.

2. United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018.

3. Agraharkar M, Nair V, Patlovany M. Recovery of renal function in dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2003;4:9.

4. Chu JK, Folkert VW. Renal function recovery in chronic dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2010;23(6):606-613.

5. Bonthius M, Harambat J, Berard E, et al. Recovery of kidney function in children treated with maintenance dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(10):1510-1516.

Q) When my patient was told that she needed dialysis, one of her first questions was, "For how long?" Which got me thinking: How often do dialysis patients regain kidney function? Are some more likely than others to be able to stop dialysis?

Diagnosis with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis, is a life-changing event. Inevitably, patients ask about their chance of recovery and the likelihood of stopping dialysis. Studies have consistently demonstrated low rates of kidney recovery, ranging from 0.9% to 2.4%.1

According to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), from 1995-2006 only 0.9% of ESRD patients regained kidney function resulting in the discontinuation of dialysis.2 In one study, Agraharkar and colleagues reviewed the medical records and lab results of patients discharged from a chronic dialysis unit and reported a 1% to 2% rate of kidney recovery. The researchers concluded that closer monitoring of residual kidney function was key to identification of patients with a greater chance of recovery.3 Chu and Folkert noted a recovery rate of 1.0% to 2.4% in a review of large observational studies, concluding that the underlying etiology of the kidney failure was the single most important predictor.4

Another study of approximately 194,000 patients who started dialysis between 2008-2009 demonstrated much higher rates of sustained recovery: up to 5%. This study showed that patients with kidney failure associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) were more likely to achieve recovery; patients with the AKI diagnosis of acute tubular necrosis had the highest rate of recovery.1

Similar studies of pediatric patients are rare. One European study followed 6,574 children who started dialysis before age 15. Within 2 years of dialysis initiation, just 2% showed kidney function recovery. This study also identified underlying etiology as an important predictor of recovery; ischemic kidney failure, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and vasculitis were associated with the greatest chance of recovery.5

Despite these recent findings, the prospect of discontinuation of dialysis with a diagnosis of ESRD remains very low. A patient's underlying etiology influences the possibility of recovery; those with AKI tend to have the greatest chance, making close monitoring of residual kidney function essential in this population.3 — MSG

Marlene Shaw-Gallagher, PA-C

Nephrology Division of Michigan Medicine

Assistant Professor at University of Detroit Mercy

Q) When my patient was told that she needed dialysis, one of her first questions was, "For how long?" Which got me thinking: How often do dialysis patients regain kidney function? Are some more likely than others to be able to stop dialysis?

Diagnosis with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis, is a life-changing event. Inevitably, patients ask about their chance of recovery and the likelihood of stopping dialysis. Studies have consistently demonstrated low rates of kidney recovery, ranging from 0.9% to 2.4%.1

According to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), from 1995-2006 only 0.9% of ESRD patients regained kidney function resulting in the discontinuation of dialysis.2 In one study, Agraharkar and colleagues reviewed the medical records and lab results of patients discharged from a chronic dialysis unit and reported a 1% to 2% rate of kidney recovery. The researchers concluded that closer monitoring of residual kidney function was key to identification of patients with a greater chance of recovery.3 Chu and Folkert noted a recovery rate of 1.0% to 2.4% in a review of large observational studies, concluding that the underlying etiology of the kidney failure was the single most important predictor.4

Another study of approximately 194,000 patients who started dialysis between 2008-2009 demonstrated much higher rates of sustained recovery: up to 5%. This study showed that patients with kidney failure associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) were more likely to achieve recovery; patients with the AKI diagnosis of acute tubular necrosis had the highest rate of recovery.1

Similar studies of pediatric patients are rare. One European study followed 6,574 children who started dialysis before age 15. Within 2 years of dialysis initiation, just 2% showed kidney function recovery. This study also identified underlying etiology as an important predictor of recovery; ischemic kidney failure, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and vasculitis were associated with the greatest chance of recovery.5

Despite these recent findings, the prospect of discontinuation of dialysis with a diagnosis of ESRD remains very low. A patient's underlying etiology influences the possibility of recovery; those with AKI tend to have the greatest chance, making close monitoring of residual kidney function essential in this population.3 — MSG

Marlene Shaw-Gallagher, PA-C

Nephrology Division of Michigan Medicine

Assistant Professor at University of Detroit Mercy

1. Mohan S, Huff E, Wish J, et al. Recovery of renal function among ESRD patients in the US Medicare program. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83447.

2. United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018.

3. Agraharkar M, Nair V, Patlovany M. Recovery of renal function in dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2003;4:9.

4. Chu JK, Folkert VW. Renal function recovery in chronic dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2010;23(6):606-613.

5. Bonthius M, Harambat J, Berard E, et al. Recovery of kidney function in children treated with maintenance dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(10):1510-1516.

1. Mohan S, Huff E, Wish J, et al. Recovery of renal function among ESRD patients in the US Medicare program. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83447.

2. United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018.

3. Agraharkar M, Nair V, Patlovany M. Recovery of renal function in dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2003;4:9.

4. Chu JK, Folkert VW. Renal function recovery in chronic dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2010;23(6):606-613.

5. Bonthius M, Harambat J, Berard E, et al. Recovery of kidney function in children treated with maintenance dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(10):1510-1516.

When to Start Dialysis

Q) I sent a patient with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15 mL/min to nephrology to start dialysis. He came back to me and said they don’t start dialysis at 15. When do you start? Why?

There is considerable variation in the timing of dialysis initiation. Research suggests that sometimes earlier is not better.

IDEAL, a randomized controlled trial conducted in Australia and New Zealand, evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of earlier versus later dialysis initiation.1 Patients were randomly assigned to start any type of dialysis when their GFR was 8 or 11 mL/min. The results indicated that starting dialysis in a patient with a higher GFR did not lower the mortality or morbidity rate but did increase costs and complications (mostly for vascular access).1

Based on these findings, most of us start dialysis in a patient who has a GFR < 10 mL/min and symptoms of kidney failure. These include a metallic taste in mouth, weight gain (usually due to edema) or loss (cachexia), feeling “poorly,” hard-to-control hypertension, shortness of breath, confusion (uremic brain), odor, skin color changes, and insomnia. Symptomatic patients can be started on dialysis at a higher GFR (usually ≤ 18 mL/min), but there are many hoops to jump through with Medicare.

However, IDEAL was conducted outside the United States and included very few elderly (age > 75) patients with chronic kidney disease. In 2018, Kurella and colleagues published a study that analyzed age and kidney function in a US veteran population.2 Their results showed that age should be included in the “when to start dialysis” calculation. For older veterans, starting dialysis earlier—at a GFR of 10 mL/min—increased survival. However, the researchers pointed out that in this age group, survival is in months (not years) and does not necessarily equate to quality of life.

In conclusion, there is no compelling evidence that initiation of dialysis based solely on measurement of kidney function leads to improvement in clinical outcomes. In otherwise asymptomatic patients, there is no reason to begin dialysis based solely on GFR; age and fragility need to be considered in the equation. Earlier is not always better, and for the elderly patient with multiple comorbidities, dialysis is not always a better choice. —TH

Tricia Howard, MHS, PA-C, DFAAPA

Georgia Regional Medical Team, Savannah

1. Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al; for the IDEAL Trial. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619.

2. Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, et al. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169-2177.

Q) I sent a patient with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15 mL/min to nephrology to start dialysis. He came back to me and said they don’t start dialysis at 15. When do you start? Why?

There is considerable variation in the timing of dialysis initiation. Research suggests that sometimes earlier is not better.

IDEAL, a randomized controlled trial conducted in Australia and New Zealand, evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of earlier versus later dialysis initiation.1 Patients were randomly assigned to start any type of dialysis when their GFR was 8 or 11 mL/min. The results indicated that starting dialysis in a patient with a higher GFR did not lower the mortality or morbidity rate but did increase costs and complications (mostly for vascular access).1

Based on these findings, most of us start dialysis in a patient who has a GFR < 10 mL/min and symptoms of kidney failure. These include a metallic taste in mouth, weight gain (usually due to edema) or loss (cachexia), feeling “poorly,” hard-to-control hypertension, shortness of breath, confusion (uremic brain), odor, skin color changes, and insomnia. Symptomatic patients can be started on dialysis at a higher GFR (usually ≤ 18 mL/min), but there are many hoops to jump through with Medicare.

However, IDEAL was conducted outside the United States and included very few elderly (age > 75) patients with chronic kidney disease. In 2018, Kurella and colleagues published a study that analyzed age and kidney function in a US veteran population.2 Their results showed that age should be included in the “when to start dialysis” calculation. For older veterans, starting dialysis earlier—at a GFR of 10 mL/min—increased survival. However, the researchers pointed out that in this age group, survival is in months (not years) and does not necessarily equate to quality of life.

In conclusion, there is no compelling evidence that initiation of dialysis based solely on measurement of kidney function leads to improvement in clinical outcomes. In otherwise asymptomatic patients, there is no reason to begin dialysis based solely on GFR; age and fragility need to be considered in the equation. Earlier is not always better, and for the elderly patient with multiple comorbidities, dialysis is not always a better choice. —TH

Tricia Howard, MHS, PA-C, DFAAPA

Georgia Regional Medical Team, Savannah

Q) I sent a patient with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15 mL/min to nephrology to start dialysis. He came back to me and said they don’t start dialysis at 15. When do you start? Why?

There is considerable variation in the timing of dialysis initiation. Research suggests that sometimes earlier is not better.

IDEAL, a randomized controlled trial conducted in Australia and New Zealand, evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of earlier versus later dialysis initiation.1 Patients were randomly assigned to start any type of dialysis when their GFR was 8 or 11 mL/min. The results indicated that starting dialysis in a patient with a higher GFR did not lower the mortality or morbidity rate but did increase costs and complications (mostly for vascular access).1

Based on these findings, most of us start dialysis in a patient who has a GFR < 10 mL/min and symptoms of kidney failure. These include a metallic taste in mouth, weight gain (usually due to edema) or loss (cachexia), feeling “poorly,” hard-to-control hypertension, shortness of breath, confusion (uremic brain), odor, skin color changes, and insomnia. Symptomatic patients can be started on dialysis at a higher GFR (usually ≤ 18 mL/min), but there are many hoops to jump through with Medicare.

However, IDEAL was conducted outside the United States and included very few elderly (age > 75) patients with chronic kidney disease. In 2018, Kurella and colleagues published a study that analyzed age and kidney function in a US veteran population.2 Their results showed that age should be included in the “when to start dialysis” calculation. For older veterans, starting dialysis earlier—at a GFR of 10 mL/min—increased survival. However, the researchers pointed out that in this age group, survival is in months (not years) and does not necessarily equate to quality of life.

In conclusion, there is no compelling evidence that initiation of dialysis based solely on measurement of kidney function leads to improvement in clinical outcomes. In otherwise asymptomatic patients, there is no reason to begin dialysis based solely on GFR; age and fragility need to be considered in the equation. Earlier is not always better, and for the elderly patient with multiple comorbidities, dialysis is not always a better choice. —TH

Tricia Howard, MHS, PA-C, DFAAPA

Georgia Regional Medical Team, Savannah

1. Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al; for the IDEAL Trial. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619.

2. Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, et al. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169-2177.

1. Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al; for the IDEAL Trial. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619.

2. Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, et al. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169-2177.

The Unsaid Dangers of NSAIDs

Q) Many total joint replacements and other orthopedic procedures are performed at the surgical center where I work. To decrease the use of narcotics, the anesthesiology department often uses IV push ketorolac postop. Our nephrology colleagues in the community are unhappy about this—but we think they’re overreacting, since these patients are often generally healthy. Is there any data on the use of ketorolac and orthopedic surgery?

All medications have associated risks. For example, while therapeutic dosages for a limited time are considered safe and effective, prolonged use of any NSAID can increase the risk for acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. We tend to associate these issues only with patients who are at higher risk for CKD: those who are older or who have diabetes or hypertension.

Thus, it was shocking to read a clinical report on four previously healthy young adults who were admitted for AKI three to four days after postoperative administration of ketorolac. None of these patients had risk factors that would predispose them to kidney disease. All had complained of gastrointestinal symptoms along with mild dehydration and flank pain; one young man even required a kidney biopsy and dialysis. All four did eventually recover kidney function. 1

Continue to: Ketorolac—like most NSAIDs...

Ketorolac—like most NSAIDs—can affect kidney function, decreasing renal plasma flow and causing a dysfunction in salt and water balance. Postoperative patients may have activity limitations (eg, the young healthy patient on crutches). Factor in kidney damage from presurgical/outpatient

With the opioid crisis at the forefront of national health news, nonnarcotic alternatives for pain control are much in demand. This puts a whole new population at risk for AKI. Educate patients and their families about preventive measures, such as controlling nausea, maintaining hydration, and monitoring urine output. Fever, flank pain, or any untoward symptoms should be reported. Remember, AKI may be more common in the older patient with diabetes—but it can occur in anyone. —EA

Ellen Apple

Dickson Schools Family Clinic, Tennessee

1. Mariano F, Cogno C, Giaretta F, et al. Urinary protein profiles in ketorolac-associated acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopedic day surgery. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:269-274.

Q) Many total joint replacements and other orthopedic procedures are performed at the surgical center where I work. To decrease the use of narcotics, the anesthesiology department often uses IV push ketorolac postop. Our nephrology colleagues in the community are unhappy about this—but we think they’re overreacting, since these patients are often generally healthy. Is there any data on the use of ketorolac and orthopedic surgery?

All medications have associated risks. For example, while therapeutic dosages for a limited time are considered safe and effective, prolonged use of any NSAID can increase the risk for acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. We tend to associate these issues only with patients who are at higher risk for CKD: those who are older or who have diabetes or hypertension.

Thus, it was shocking to read a clinical report on four previously healthy young adults who were admitted for AKI three to four days after postoperative administration of ketorolac. None of these patients had risk factors that would predispose them to kidney disease. All had complained of gastrointestinal symptoms along with mild dehydration and flank pain; one young man even required a kidney biopsy and dialysis. All four did eventually recover kidney function. 1

Continue to: Ketorolac—like most NSAIDs...

Ketorolac—like most NSAIDs—can affect kidney function, decreasing renal plasma flow and causing a dysfunction in salt and water balance. Postoperative patients may have activity limitations (eg, the young healthy patient on crutches). Factor in kidney damage from presurgical/outpatient

With the opioid crisis at the forefront of national health news, nonnarcotic alternatives for pain control are much in demand. This puts a whole new population at risk for AKI. Educate patients and their families about preventive measures, such as controlling nausea, maintaining hydration, and monitoring urine output. Fever, flank pain, or any untoward symptoms should be reported. Remember, AKI may be more common in the older patient with diabetes—but it can occur in anyone. —EA

Ellen Apple

Dickson Schools Family Clinic, Tennessee

Q) Many total joint replacements and other orthopedic procedures are performed at the surgical center where I work. To decrease the use of narcotics, the anesthesiology department often uses IV push ketorolac postop. Our nephrology colleagues in the community are unhappy about this—but we think they’re overreacting, since these patients are often generally healthy. Is there any data on the use of ketorolac and orthopedic surgery?

All medications have associated risks. For example, while therapeutic dosages for a limited time are considered safe and effective, prolonged use of any NSAID can increase the risk for acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. We tend to associate these issues only with patients who are at higher risk for CKD: those who are older or who have diabetes or hypertension.

Thus, it was shocking to read a clinical report on four previously healthy young adults who were admitted for AKI three to four days after postoperative administration of ketorolac. None of these patients had risk factors that would predispose them to kidney disease. All had complained of gastrointestinal symptoms along with mild dehydration and flank pain; one young man even required a kidney biopsy and dialysis. All four did eventually recover kidney function. 1

Continue to: Ketorolac—like most NSAIDs...

Ketorolac—like most NSAIDs—can affect kidney function, decreasing renal plasma flow and causing a dysfunction in salt and water balance. Postoperative patients may have activity limitations (eg, the young healthy patient on crutches). Factor in kidney damage from presurgical/outpatient

With the opioid crisis at the forefront of national health news, nonnarcotic alternatives for pain control are much in demand. This puts a whole new population at risk for AKI. Educate patients and their families about preventive measures, such as controlling nausea, maintaining hydration, and monitoring urine output. Fever, flank pain, or any untoward symptoms should be reported. Remember, AKI may be more common in the older patient with diabetes—but it can occur in anyone. —EA

Ellen Apple

Dickson Schools Family Clinic, Tennessee

1. Mariano F, Cogno C, Giaretta F, et al. Urinary protein profiles in ketorolac-associated acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopedic day surgery. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:269-274.

1. Mariano F, Cogno C, Giaretta F, et al. Urinary protein profiles in ketorolac-associated acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopedic day surgery. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:269-274.

How the IHS Reduced Kidney Disease in the Highest-risk Population

Alaska is a vast state—larger than Texas, Montana, and California combined. It is also home to the highest percentage of American Indian (AI) and Alaska Native (AN) persons in the United States. These two populations—collectively referred to as Native Americans—have been served by the Indian Health Services (IHS) since it was established through the Snyder Act of 1921, in response to the dismal health conditions of the indigenous tribes in this country.1 Across the US (not only in Alaska), the IHS has partnered with AI/AN peoples to decrease health disparities in a culturally acceptable manner that honors and protects their traditions and values.

The IHS—which in 2016 comprised 2,500 nurses, 750 physicians, 700 pharmacists, 200 PAs and NPs, and 280 dentists, as well as nutritionists, diabetes educators, administrators, and other professionals—has made huge advances in decreasing health disparities in their populations. Among them: decreased rates of tuberculosis and of maternal and infant deaths.

However, life expectancy among Native Americans remains four years shorter than that of the rest of the US population. This disparity can be traced to three recalcitrant factors: unintentional injuries, liver disease, and diabetes.

The IHS practitioners decided to tackle diabetes with a multipronged approach. And what they achieved is astonishing.

WHAT THEY DID

Worldwide, diabetes is the most common cause of kidney failure; identifying patients with diabetes and early-stage chronic kidney disease allows for aggressive treatment that can slow progression to kidney failure and dialysis.

The IHS providers knew when they decided to tackle the problem of diabetes in the AI/AN population that the incidence was 16%—and the rate of diabetes leading to kidney failure in this population was the highest for any ethnic group in the US.2,3 And yet …

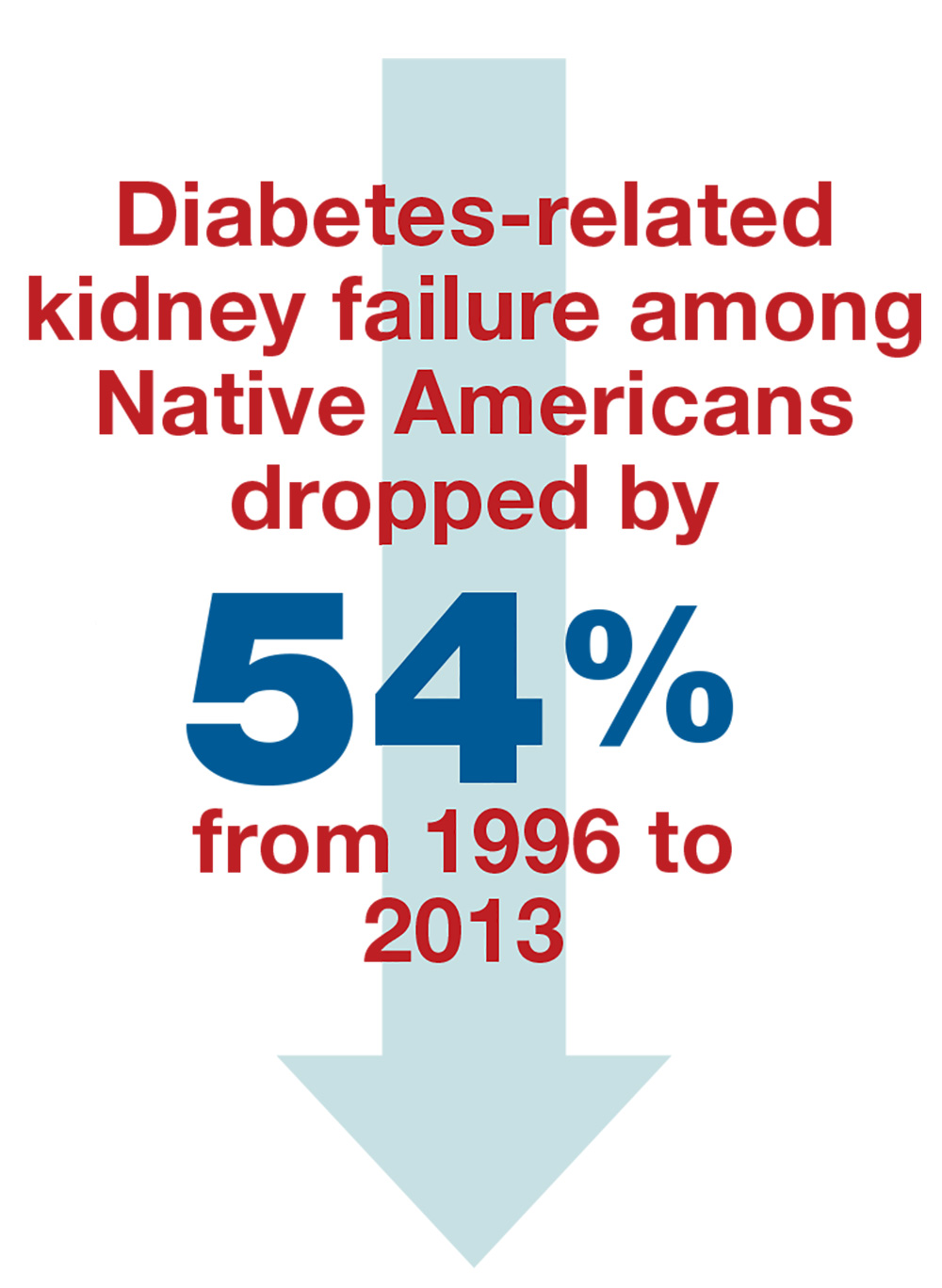

From 1996 to 2013, the rate of diabetes-related kidney failure among Native Americans dropped by 54%.3 Yes—the group of patients with the highest percentage of diabetes diagnoses has had the greatest improvement in prevention of kidney failure.4

Continue to: Some of the clinical achievements that contributed to...

Some of the clinical achievements that contributed to this significant change include

- Increased use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (from 42% to 74% over a five-year period)

- Reduced average blood pressure among hypertensive patients (to 133/76 mm Hg)

- Improved blood glucose control (by 10%)

- Increased testing for kidney disease among older patients (50% higher than the rest of the Medicare diabetes population).3

HOW THEY DID IT