User login

Bone Health in Kidney Disease

Q) What are the current recommendations for the use of DXA and bisphosphonates in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease?

For patients with kidney disease, mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is a common complication, affecting the majority of those with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (CKD; see Table 1).1,2 CKD-MBD is a systemic disorder that encompasses abnormalities in mineral metabolism, skeletal health, and soft-tissue calcifications.1,2 It manifests as one or more of the following:

- Abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), or vitamin D metabolism

- Abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth, or strength

- Vascular or other soft-tissue calcification.2

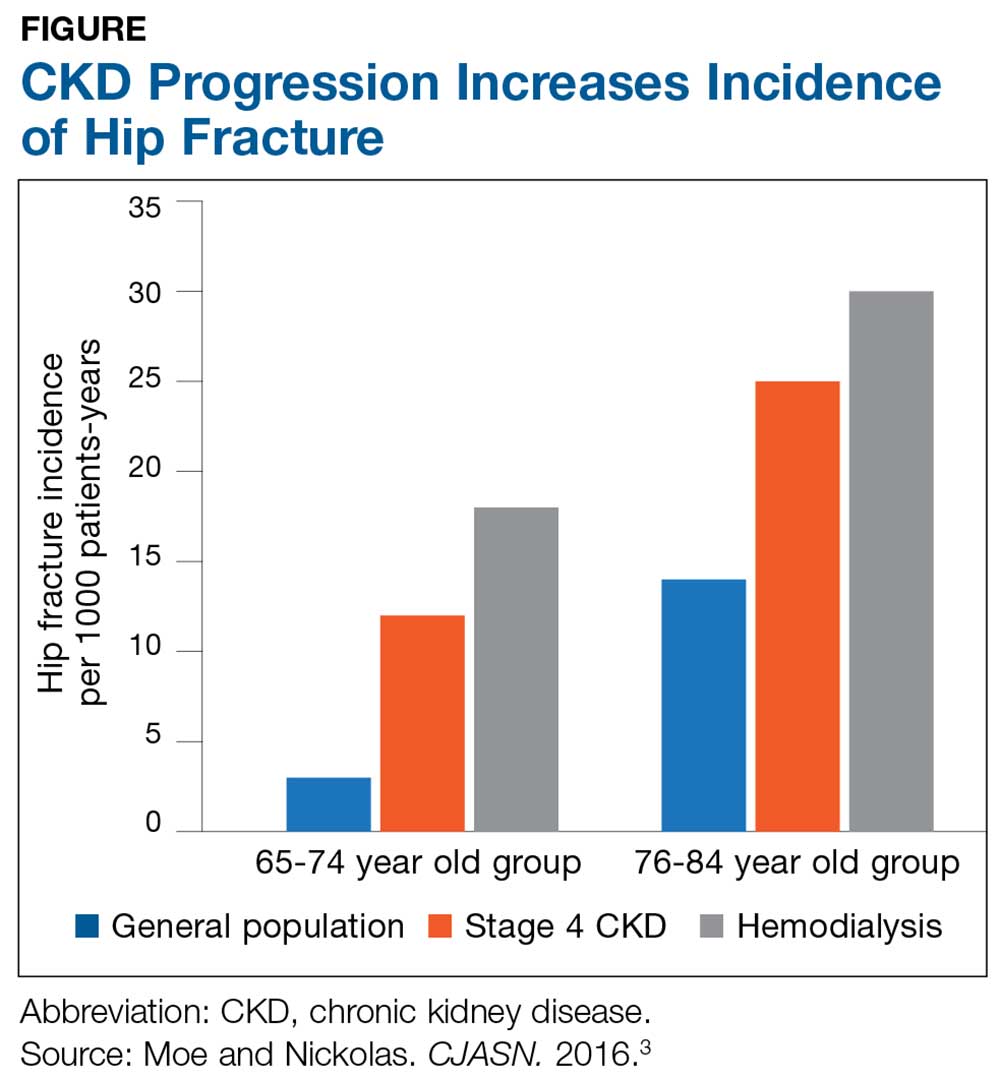

The Figure provides an illustration of the effect of CKD on bone health: In the general population, risk for hip fracture increases with age; risk is further exacerbated in those who have CKD.3

To assess for fracture risk in patients with advanced stages of CKD (3-5) who have evidence of CKD-MBD and/or risk factors for osteoporosis, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) group recommends bone mineral density testing with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).2 Bone biopsy—the gold standard for diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy, a form of osteoporosis and one type of bone abnormality seen in CKD-MBD—is “reasonable” to perform in cases in which knowing the type of renal osteodystrophy would inform treatment choices.2 KDIGO also recognizes limitations in the ability to perform a bone biopsy and therefore recommends monitoring serial PTH and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase to evaluate for bone disease.2

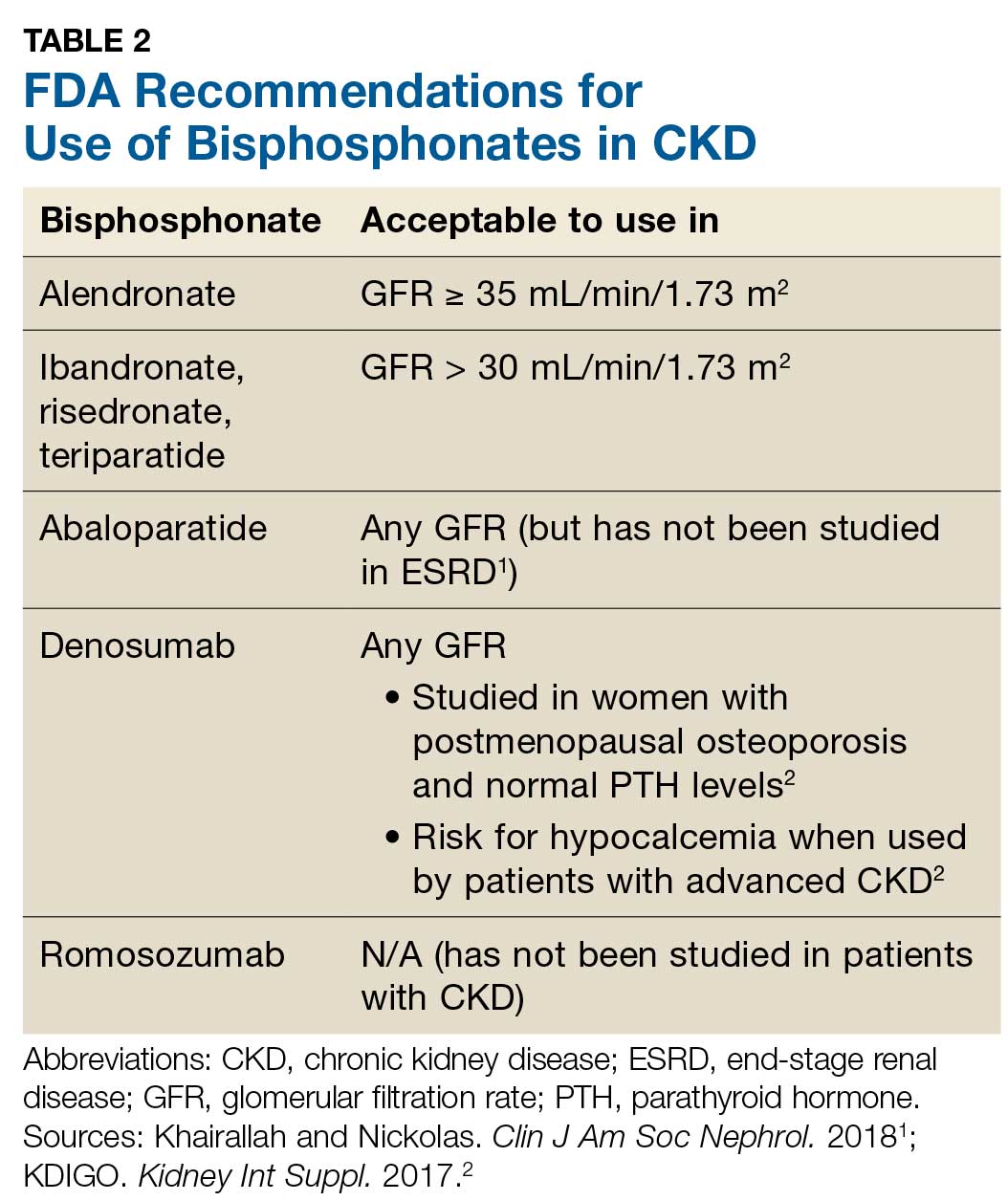

Prevention of fractures and treatment of patients with CKD-MDB has historically been challenging, since many of the available pharmacologic agents have not been developed for or studied in patients with CKD.1 According to KDIGO, it is acceptable for patients with CKD stages 1 and 2 to receive the same osteoporosis/fracture risk management as recommended for the general population.2 Patients with CKD stages 3a and 3b can also receive treatment as recommended for the general population, as long as the patient’s PTH level is in normal range.2 Table 2 outlines the FDA-approved glomerular filtration rate cutoffs for some bisphosphonates commonly used to treat osteoporosis.

Before initiating treatment for CKD-associated osteoporosis, no matter what the stage, it is important to manage vitamin D deficiency, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism.1 In CKD patients with abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and/or vitamin D, involve the nephrology team to assist in providing MBD care. Different approaches to treatment may include, but are not limited to, adjusting phosphorus binders; using vitamin D supplements or analogs; using calcimimetics; prescribing dialysis; providing dietary education; and addressing medication costs.

1. Khairallah P, Nickolas TL. Management of osteoporosis in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(6):962-969.

2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:1-59.

3. Moe SM, Nickolas TL. Fractures in patients with CKD: time for action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(11):1929-1931.

Q) What are the current recommendations for the use of DXA and bisphosphonates in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease?

For patients with kidney disease, mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is a common complication, affecting the majority of those with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (CKD; see Table 1).1,2 CKD-MBD is a systemic disorder that encompasses abnormalities in mineral metabolism, skeletal health, and soft-tissue calcifications.1,2 It manifests as one or more of the following:

- Abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), or vitamin D metabolism

- Abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth, or strength

- Vascular or other soft-tissue calcification.2

The Figure provides an illustration of the effect of CKD on bone health: In the general population, risk for hip fracture increases with age; risk is further exacerbated in those who have CKD.3

To assess for fracture risk in patients with advanced stages of CKD (3-5) who have evidence of CKD-MBD and/or risk factors for osteoporosis, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) group recommends bone mineral density testing with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).2 Bone biopsy—the gold standard for diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy, a form of osteoporosis and one type of bone abnormality seen in CKD-MBD—is “reasonable” to perform in cases in which knowing the type of renal osteodystrophy would inform treatment choices.2 KDIGO also recognizes limitations in the ability to perform a bone biopsy and therefore recommends monitoring serial PTH and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase to evaluate for bone disease.2

Prevention of fractures and treatment of patients with CKD-MDB has historically been challenging, since many of the available pharmacologic agents have not been developed for or studied in patients with CKD.1 According to KDIGO, it is acceptable for patients with CKD stages 1 and 2 to receive the same osteoporosis/fracture risk management as recommended for the general population.2 Patients with CKD stages 3a and 3b can also receive treatment as recommended for the general population, as long as the patient’s PTH level is in normal range.2 Table 2 outlines the FDA-approved glomerular filtration rate cutoffs for some bisphosphonates commonly used to treat osteoporosis.

Before initiating treatment for CKD-associated osteoporosis, no matter what the stage, it is important to manage vitamin D deficiency, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism.1 In CKD patients with abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and/or vitamin D, involve the nephrology team to assist in providing MBD care. Different approaches to treatment may include, but are not limited to, adjusting phosphorus binders; using vitamin D supplements or analogs; using calcimimetics; prescribing dialysis; providing dietary education; and addressing medication costs.

Q) What are the current recommendations for the use of DXA and bisphosphonates in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease?

For patients with kidney disease, mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is a common complication, affecting the majority of those with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (CKD; see Table 1).1,2 CKD-MBD is a systemic disorder that encompasses abnormalities in mineral metabolism, skeletal health, and soft-tissue calcifications.1,2 It manifests as one or more of the following:

- Abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), or vitamin D metabolism

- Abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth, or strength

- Vascular or other soft-tissue calcification.2

The Figure provides an illustration of the effect of CKD on bone health: In the general population, risk for hip fracture increases with age; risk is further exacerbated in those who have CKD.3

To assess for fracture risk in patients with advanced stages of CKD (3-5) who have evidence of CKD-MBD and/or risk factors for osteoporosis, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) group recommends bone mineral density testing with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).2 Bone biopsy—the gold standard for diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy, a form of osteoporosis and one type of bone abnormality seen in CKD-MBD—is “reasonable” to perform in cases in which knowing the type of renal osteodystrophy would inform treatment choices.2 KDIGO also recognizes limitations in the ability to perform a bone biopsy and therefore recommends monitoring serial PTH and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase to evaluate for bone disease.2

Prevention of fractures and treatment of patients with CKD-MDB has historically been challenging, since many of the available pharmacologic agents have not been developed for or studied in patients with CKD.1 According to KDIGO, it is acceptable for patients with CKD stages 1 and 2 to receive the same osteoporosis/fracture risk management as recommended for the general population.2 Patients with CKD stages 3a and 3b can also receive treatment as recommended for the general population, as long as the patient’s PTH level is in normal range.2 Table 2 outlines the FDA-approved glomerular filtration rate cutoffs for some bisphosphonates commonly used to treat osteoporosis.

Before initiating treatment for CKD-associated osteoporosis, no matter what the stage, it is important to manage vitamin D deficiency, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism.1 In CKD patients with abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and/or vitamin D, involve the nephrology team to assist in providing MBD care. Different approaches to treatment may include, but are not limited to, adjusting phosphorus binders; using vitamin D supplements or analogs; using calcimimetics; prescribing dialysis; providing dietary education; and addressing medication costs.

1. Khairallah P, Nickolas TL. Management of osteoporosis in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(6):962-969.

2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:1-59.

3. Moe SM, Nickolas TL. Fractures in patients with CKD: time for action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(11):1929-1931.

1. Khairallah P, Nickolas TL. Management of osteoporosis in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(6):962-969.

2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:1-59.

3. Moe SM, Nickolas TL. Fractures in patients with CKD: time for action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(11):1929-1931.