User login

Dental Health: What It Means in Kidney Disease

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

For Patients With CKD, Don’t Wait—Vaccinate!

Q) What can I tell my kidney patients to increase acceptance of the influenza and pneumonia vaccines during cold and flu season?

The CDC recommends that everyone ages 6 months and older receive an annual flu vaccination, unless contraindicated.1 Additionally, administration of either the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for all adults ages 65 and older and for younger adults (ages 19 to 64) with diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic heart disease, and/or solid organ transplant.1 Despite these recommendations, patients often decline vaccination. What they may not realize is that CKD increases their risk for infection.

In a cohort of more than 1 million Swedish patients, researchers found that any stage of CKD increased risk for community-acquired infection and that the risk for lower respiratory tract infection increased as glomerular filtration rate declined.2 Patients on hemodialysis have an increased risk for pneumonia and an incidence of pneumonia-related mortality that is up to 16 times higher than that of the general population.3 Pneumonia also increases the risk for cardiovascular events among all patients with CKD, regardless of stage.4

So, can vaccines reduce these risks in our kidney patients? McGrath and colleagues found that patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who were vaccinated against the flu had lower mortality rates than those who were not vaccinated—even when the vaccine was poorly matched to the circulating virus strain.5 Additional research has demonstrated that for patients with any stage of CKD, including those on dialysis, the flu vaccine is safe and effective, and its protection may be durable over time.6

For pneumonia vaccines, antibody response in patients with CKD may be suboptimal; however, Medicare data have demonstrated that patients with ESRD who are vaccinated against pneumonia have lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than unvaccinated patients do.5 Given their increased vulnerability to vaccine-preventable respiratory illnesses, it is imperative that our kidney patients receive both the flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Nicole DeFeo McCormick, DNP, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

Assistant Professor

School of Medicine at the University of Colorado

1. CDC. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Xu H, Gasparini A, Ishigami J, et al. eGFR and the risk of community-acquired infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(9):1399-1408.

3. Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL. Pulmonary infectious mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest. 2001;120(6): 1883-1887.

4. Mathew R, Mason D, Kennedy JS. Vaccination issues in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):285-298.

5. McGrath LJ, Kshirsagar AV, Cole SR, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccine effectiveness among hemodialysis patients using a natural experiment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7): 548-554.

6. Janus N, Vacher L, Karie S, et al. Vaccination and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):800-807.

Q) What can I tell my kidney patients to increase acceptance of the influenza and pneumonia vaccines during cold and flu season?

The CDC recommends that everyone ages 6 months and older receive an annual flu vaccination, unless contraindicated.1 Additionally, administration of either the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for all adults ages 65 and older and for younger adults (ages 19 to 64) with diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic heart disease, and/or solid organ transplant.1 Despite these recommendations, patients often decline vaccination. What they may not realize is that CKD increases their risk for infection.

In a cohort of more than 1 million Swedish patients, researchers found that any stage of CKD increased risk for community-acquired infection and that the risk for lower respiratory tract infection increased as glomerular filtration rate declined.2 Patients on hemodialysis have an increased risk for pneumonia and an incidence of pneumonia-related mortality that is up to 16 times higher than that of the general population.3 Pneumonia also increases the risk for cardiovascular events among all patients with CKD, regardless of stage.4

So, can vaccines reduce these risks in our kidney patients? McGrath and colleagues found that patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who were vaccinated against the flu had lower mortality rates than those who were not vaccinated—even when the vaccine was poorly matched to the circulating virus strain.5 Additional research has demonstrated that for patients with any stage of CKD, including those on dialysis, the flu vaccine is safe and effective, and its protection may be durable over time.6

For pneumonia vaccines, antibody response in patients with CKD may be suboptimal; however, Medicare data have demonstrated that patients with ESRD who are vaccinated against pneumonia have lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than unvaccinated patients do.5 Given their increased vulnerability to vaccine-preventable respiratory illnesses, it is imperative that our kidney patients receive both the flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Nicole DeFeo McCormick, DNP, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

Assistant Professor

School of Medicine at the University of Colorado

Q) What can I tell my kidney patients to increase acceptance of the influenza and pneumonia vaccines during cold and flu season?

The CDC recommends that everyone ages 6 months and older receive an annual flu vaccination, unless contraindicated.1 Additionally, administration of either the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for all adults ages 65 and older and for younger adults (ages 19 to 64) with diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic heart disease, and/or solid organ transplant.1 Despite these recommendations, patients often decline vaccination. What they may not realize is that CKD increases their risk for infection.

In a cohort of more than 1 million Swedish patients, researchers found that any stage of CKD increased risk for community-acquired infection and that the risk for lower respiratory tract infection increased as glomerular filtration rate declined.2 Patients on hemodialysis have an increased risk for pneumonia and an incidence of pneumonia-related mortality that is up to 16 times higher than that of the general population.3 Pneumonia also increases the risk for cardiovascular events among all patients with CKD, regardless of stage.4

So, can vaccines reduce these risks in our kidney patients? McGrath and colleagues found that patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who were vaccinated against the flu had lower mortality rates than those who were not vaccinated—even when the vaccine was poorly matched to the circulating virus strain.5 Additional research has demonstrated that for patients with any stage of CKD, including those on dialysis, the flu vaccine is safe and effective, and its protection may be durable over time.6

For pneumonia vaccines, antibody response in patients with CKD may be suboptimal; however, Medicare data have demonstrated that patients with ESRD who are vaccinated against pneumonia have lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than unvaccinated patients do.5 Given their increased vulnerability to vaccine-preventable respiratory illnesses, it is imperative that our kidney patients receive both the flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Nicole DeFeo McCormick, DNP, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

Assistant Professor

School of Medicine at the University of Colorado

1. CDC. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Xu H, Gasparini A, Ishigami J, et al. eGFR and the risk of community-acquired infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(9):1399-1408.

3. Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL. Pulmonary infectious mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest. 2001;120(6): 1883-1887.

4. Mathew R, Mason D, Kennedy JS. Vaccination issues in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):285-298.

5. McGrath LJ, Kshirsagar AV, Cole SR, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccine effectiveness among hemodialysis patients using a natural experiment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7): 548-554.

6. Janus N, Vacher L, Karie S, et al. Vaccination and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):800-807.

1. CDC. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Xu H, Gasparini A, Ishigami J, et al. eGFR and the risk of community-acquired infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(9):1399-1408.

3. Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL. Pulmonary infectious mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest. 2001;120(6): 1883-1887.

4. Mathew R, Mason D, Kennedy JS. Vaccination issues in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):285-298.

5. McGrath LJ, Kshirsagar AV, Cole SR, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccine effectiveness among hemodialysis patients using a natural experiment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7): 548-554.

6. Janus N, Vacher L, Karie S, et al. Vaccination and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):800-807.

How to Interpret Positive Troponin Tests in CKD

Q) Recently, when I have sent my patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to the emergency department (ED) for complaints of chest pain or shortness of breath, their troponin levels are high. I know CKD increases risk for cardiovascular disease, but I find it hard to believe that every CKD patient is having an MI. What gives?

Cardiovascular disease remains the most common cause of death in patients with CKD, accounting for 45% to 50% of all deaths. Therefore, accurate diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in this patient population is vital to assure prompt identification and treatment.1,2

Cardiac troponins are the gold standard for detecting myocardial injury in patients presenting to the ED with suggestive symptoms.1 But the chronic baseline elevation in serum troponin levels among patients with CKD often results in a false-positive reading, making the detection of AMI difficult.1

With the recent introduction of high-sensitivity troponin assays, as many as 97% of patients on hemodialysis exhibit elevated troponin levels; this is also true for patients with CKD, on a sliding scale (lower kidney function = higher baseline troponins).2 The use of high-sensitivity testing has increased substantially in the past 15 years, and it is expected to become the benchmark for troponin evaluation. While older troponin tests had a false-positive rate of 30% to 85% in patients with stage 5 CKD, the newer troponin tests display elevated troponins in almost 100% of these patients.1,2

Numerous studies have been conducted to determine the best way to interpret positive troponin tests in patients with CKD to ensure an accurate diagnosis of AMI.2 One study determined that a 20% increase in troponin levels was a more accurate determinant of AMI in patients with CKD than one isolated positive level.3 Another study demonstrated that serial troponin measurements conducted over time yielded higher diagnostic accuracy than one measurement above the 99th percentile.4

The American College of Cardiology Foundation task force found that monitoring changes in troponin concentration over time (3-6 h) is more accurate than a single elevated troponin when diagnosing AMI in symptomatic patients.3 Correlation between elevated troponin levels and clinical suspicion proved helpful in determining the significance of troponin results and the probability of AMI in patients with CKD.2

The significance and interpretation of elevated troponin levels in patients with CKD remains an important topic for further study, as cardiovascular disease continues to be the leading cause of mortality in patients with kidney dysfunction.1,2 More definitive studies need to be conducted on patients with CKD as high-sensitivity troponin assay testing becomes standard for diagnosing AMI.

So, the reason you see more positive troponin results in your CKD population is due to both the increased accuracy of the newer tests and the fact that CKD often causes a false-positive result. Monitoring your patients with serial troponins for at least three hours is essential to confirm or rule out an AMI. —MS-G

Marlene Shaw-Gallagher, MS, PA-C

University of Detroit Mercy, Michigan

Division of Nephrology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

1. Robitaille R, Lafrance JP, Leblanc M. Altered laboratory findings associated with end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2006;19(5):373.

2. Howard CE, McCullough PA. Decoding acute myocardial infarction among patients on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(5):1337-1339.

3. Newby LK, Jesse RL, Babb JD, et al. ACCF 2012 expert consensus document on practical clinical considerations in the interpretation of troponin elevations: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation task force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60(23):2427-2463.

4. Mahajan VS, Petr Jarolim P. How to interpret elevated cardiac troponin levels. Circulation. 2011;124:2350-2354.

Q) Recently, when I have sent my patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to the emergency department (ED) for complaints of chest pain or shortness of breath, their troponin levels are high. I know CKD increases risk for cardiovascular disease, but I find it hard to believe that every CKD patient is having an MI. What gives?

Cardiovascular disease remains the most common cause of death in patients with CKD, accounting for 45% to 50% of all deaths. Therefore, accurate diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in this patient population is vital to assure prompt identification and treatment.1,2

Cardiac troponins are the gold standard for detecting myocardial injury in patients presenting to the ED with suggestive symptoms.1 But the chronic baseline elevation in serum troponin levels among patients with CKD often results in a false-positive reading, making the detection of AMI difficult.1

With the recent introduction of high-sensitivity troponin assays, as many as 97% of patients on hemodialysis exhibit elevated troponin levels; this is also true for patients with CKD, on a sliding scale (lower kidney function = higher baseline troponins).2 The use of high-sensitivity testing has increased substantially in the past 15 years, and it is expected to become the benchmark for troponin evaluation. While older troponin tests had a false-positive rate of 30% to 85% in patients with stage 5 CKD, the newer troponin tests display elevated troponins in almost 100% of these patients.1,2

Numerous studies have been conducted to determine the best way to interpret positive troponin tests in patients with CKD to ensure an accurate diagnosis of AMI.2 One study determined that a 20% increase in troponin levels was a more accurate determinant of AMI in patients with CKD than one isolated positive level.3 Another study demonstrated that serial troponin measurements conducted over time yielded higher diagnostic accuracy than one measurement above the 99th percentile.4

The American College of Cardiology Foundation task force found that monitoring changes in troponin concentration over time (3-6 h) is more accurate than a single elevated troponin when diagnosing AMI in symptomatic patients.3 Correlation between elevated troponin levels and clinical suspicion proved helpful in determining the significance of troponin results and the probability of AMI in patients with CKD.2

The significance and interpretation of elevated troponin levels in patients with CKD remains an important topic for further study, as cardiovascular disease continues to be the leading cause of mortality in patients with kidney dysfunction.1,2 More definitive studies need to be conducted on patients with CKD as high-sensitivity troponin assay testing becomes standard for diagnosing AMI.

So, the reason you see more positive troponin results in your CKD population is due to both the increased accuracy of the newer tests and the fact that CKD often causes a false-positive result. Monitoring your patients with serial troponins for at least three hours is essential to confirm or rule out an AMI. —MS-G

Marlene Shaw-Gallagher, MS, PA-C

University of Detroit Mercy, Michigan

Division of Nephrology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Q) Recently, when I have sent my patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to the emergency department (ED) for complaints of chest pain or shortness of breath, their troponin levels are high. I know CKD increases risk for cardiovascular disease, but I find it hard to believe that every CKD patient is having an MI. What gives?

Cardiovascular disease remains the most common cause of death in patients with CKD, accounting for 45% to 50% of all deaths. Therefore, accurate diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in this patient population is vital to assure prompt identification and treatment.1,2

Cardiac troponins are the gold standard for detecting myocardial injury in patients presenting to the ED with suggestive symptoms.1 But the chronic baseline elevation in serum troponin levels among patients with CKD often results in a false-positive reading, making the detection of AMI difficult.1

With the recent introduction of high-sensitivity troponin assays, as many as 97% of patients on hemodialysis exhibit elevated troponin levels; this is also true for patients with CKD, on a sliding scale (lower kidney function = higher baseline troponins).2 The use of high-sensitivity testing has increased substantially in the past 15 years, and it is expected to become the benchmark for troponin evaluation. While older troponin tests had a false-positive rate of 30% to 85% in patients with stage 5 CKD, the newer troponin tests display elevated troponins in almost 100% of these patients.1,2

Numerous studies have been conducted to determine the best way to interpret positive troponin tests in patients with CKD to ensure an accurate diagnosis of AMI.2 One study determined that a 20% increase in troponin levels was a more accurate determinant of AMI in patients with CKD than one isolated positive level.3 Another study demonstrated that serial troponin measurements conducted over time yielded higher diagnostic accuracy than one measurement above the 99th percentile.4

The American College of Cardiology Foundation task force found that monitoring changes in troponin concentration over time (3-6 h) is more accurate than a single elevated troponin when diagnosing AMI in symptomatic patients.3 Correlation between elevated troponin levels and clinical suspicion proved helpful in determining the significance of troponin results and the probability of AMI in patients with CKD.2

The significance and interpretation of elevated troponin levels in patients with CKD remains an important topic for further study, as cardiovascular disease continues to be the leading cause of mortality in patients with kidney dysfunction.1,2 More definitive studies need to be conducted on patients with CKD as high-sensitivity troponin assay testing becomes standard for diagnosing AMI.

So, the reason you see more positive troponin results in your CKD population is due to both the increased accuracy of the newer tests and the fact that CKD often causes a false-positive result. Monitoring your patients with serial troponins for at least three hours is essential to confirm or rule out an AMI. —MS-G

Marlene Shaw-Gallagher, MS, PA-C

University of Detroit Mercy, Michigan

Division of Nephrology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

1. Robitaille R, Lafrance JP, Leblanc M. Altered laboratory findings associated with end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2006;19(5):373.

2. Howard CE, McCullough PA. Decoding acute myocardial infarction among patients on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(5):1337-1339.

3. Newby LK, Jesse RL, Babb JD, et al. ACCF 2012 expert consensus document on practical clinical considerations in the interpretation of troponin elevations: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation task force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60(23):2427-2463.

4. Mahajan VS, Petr Jarolim P. How to interpret elevated cardiac troponin levels. Circulation. 2011;124:2350-2354.

1. Robitaille R, Lafrance JP, Leblanc M. Altered laboratory findings associated with end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2006;19(5):373.

2. Howard CE, McCullough PA. Decoding acute myocardial infarction among patients on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(5):1337-1339.

3. Newby LK, Jesse RL, Babb JD, et al. ACCF 2012 expert consensus document on practical clinical considerations in the interpretation of troponin elevations: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation task force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60(23):2427-2463.

4. Mahajan VS, Petr Jarolim P. How to interpret elevated cardiac troponin levels. Circulation. 2011;124:2350-2354.

Do PPIs Pose a Danger to Kidneys?

Q) Is it true that PPI use can cause kidney disease?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been available in the United States since 1990, with OTC options available since 2009. While these medications play a vital role in the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, observational studies have linked PPI use to serious adverse events, including dementia, community-acquired pneumonia, hip fracture, and Clostridium difficile infection.1-4

Studies have also found an association between PPI use and kidney problems such as acute kidney injury (AKI), acute interstitial nephritis, and incident chronic kidney disease (CKD).5-7 One observational study used the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national databases to track the renal outcomes of 173,321 new PPI users and 20,270 new histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users over the course of five years. Those who used PPIs demonstrated a significant risk for decreased renal function, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), doubled serum creatinine levels, and progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).8

Another study of 10,482 patients (322 PPI; 956 H2RA; 9,204 nonusers) and a replicate study of 248,751 patients (16,900 PPI; 6,640 H2RA; 225,211 nonusers) with an initial eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 also found an association between PPI use and incident CKD, which persisted when compared to the other groups. Additionally, twice-daily PPI use was associated with a higher CKD risk than once-daily use.9

The pathophysiology of PPI use and kidney deterioration is poorly understood at this point. It is known that AKI can increase the risk for CKD, and AKI has been an assumed precursor to PPI-associated CKD. However, a study by Xie and colleagues reported an association between PPI use and increased risk for CKD, progression of CKD, and ESRD in the absence of preceding AKI. Using the VA databases, the researchers identified 144,032 new users of acid-suppressing medications (125,596 PPI; 18,436 H2RA) who had no history of kidney disease and followed them for five years. PPI users were found to be at increased risk for CKD, and a graded association was discovered between length of PPI use and risk for CKD.10

While these studies are observational and therefore do not prove causation, they do suggest a need for attentive monitoring of kidney function in patients using PPIs. Evaluating the need for PPIs and inquiring about OTC use of these medications is highly recommended, as research has found 25% to 70% of PPI prescriptions are not prescribed for an appropriate indication.11 Considerations regarding PPI use should include dosage, length of use, and whether alternate use of an H2RA is appropriate. —CAS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410-416.

2. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0128004.

3. Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006; 296(24):2947-2953.

4. Dial S, Alrasadi K, Manoukian C, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case-control studies. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):33-38.

5. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:150.

6. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, et al. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86:837-844.

7. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E166-171.

8. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):3153-3163.

9. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238-246.

10. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Long-term kidney outcomes among users of proton pump inhibitors without intervening acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1482-1494.

11. Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336(7634):2-3.

Q) Is it true that PPI use can cause kidney disease?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been available in the United States since 1990, with OTC options available since 2009. While these medications play a vital role in the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, observational studies have linked PPI use to serious adverse events, including dementia, community-acquired pneumonia, hip fracture, and Clostridium difficile infection.1-4

Studies have also found an association between PPI use and kidney problems such as acute kidney injury (AKI), acute interstitial nephritis, and incident chronic kidney disease (CKD).5-7 One observational study used the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national databases to track the renal outcomes of 173,321 new PPI users and 20,270 new histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users over the course of five years. Those who used PPIs demonstrated a significant risk for decreased renal function, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), doubled serum creatinine levels, and progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).8

Another study of 10,482 patients (322 PPI; 956 H2RA; 9,204 nonusers) and a replicate study of 248,751 patients (16,900 PPI; 6,640 H2RA; 225,211 nonusers) with an initial eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 also found an association between PPI use and incident CKD, which persisted when compared to the other groups. Additionally, twice-daily PPI use was associated with a higher CKD risk than once-daily use.9

The pathophysiology of PPI use and kidney deterioration is poorly understood at this point. It is known that AKI can increase the risk for CKD, and AKI has been an assumed precursor to PPI-associated CKD. However, a study by Xie and colleagues reported an association between PPI use and increased risk for CKD, progression of CKD, and ESRD in the absence of preceding AKI. Using the VA databases, the researchers identified 144,032 new users of acid-suppressing medications (125,596 PPI; 18,436 H2RA) who had no history of kidney disease and followed them for five years. PPI users were found to be at increased risk for CKD, and a graded association was discovered between length of PPI use and risk for CKD.10

While these studies are observational and therefore do not prove causation, they do suggest a need for attentive monitoring of kidney function in patients using PPIs. Evaluating the need for PPIs and inquiring about OTC use of these medications is highly recommended, as research has found 25% to 70% of PPI prescriptions are not prescribed for an appropriate indication.11 Considerations regarding PPI use should include dosage, length of use, and whether alternate use of an H2RA is appropriate. —CAS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

Q) Is it true that PPI use can cause kidney disease?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been available in the United States since 1990, with OTC options available since 2009. While these medications play a vital role in the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, observational studies have linked PPI use to serious adverse events, including dementia, community-acquired pneumonia, hip fracture, and Clostridium difficile infection.1-4

Studies have also found an association between PPI use and kidney problems such as acute kidney injury (AKI), acute interstitial nephritis, and incident chronic kidney disease (CKD).5-7 One observational study used the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national databases to track the renal outcomes of 173,321 new PPI users and 20,270 new histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users over the course of five years. Those who used PPIs demonstrated a significant risk for decreased renal function, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), doubled serum creatinine levels, and progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).8

Another study of 10,482 patients (322 PPI; 956 H2RA; 9,204 nonusers) and a replicate study of 248,751 patients (16,900 PPI; 6,640 H2RA; 225,211 nonusers) with an initial eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 also found an association between PPI use and incident CKD, which persisted when compared to the other groups. Additionally, twice-daily PPI use was associated with a higher CKD risk than once-daily use.9

The pathophysiology of PPI use and kidney deterioration is poorly understood at this point. It is known that AKI can increase the risk for CKD, and AKI has been an assumed precursor to PPI-associated CKD. However, a study by Xie and colleagues reported an association between PPI use and increased risk for CKD, progression of CKD, and ESRD in the absence of preceding AKI. Using the VA databases, the researchers identified 144,032 new users of acid-suppressing medications (125,596 PPI; 18,436 H2RA) who had no history of kidney disease and followed them for five years. PPI users were found to be at increased risk for CKD, and a graded association was discovered between length of PPI use and risk for CKD.10

While these studies are observational and therefore do not prove causation, they do suggest a need for attentive monitoring of kidney function in patients using PPIs. Evaluating the need for PPIs and inquiring about OTC use of these medications is highly recommended, as research has found 25% to 70% of PPI prescriptions are not prescribed for an appropriate indication.11 Considerations regarding PPI use should include dosage, length of use, and whether alternate use of an H2RA is appropriate. —CAS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410-416.

2. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0128004.

3. Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006; 296(24):2947-2953.

4. Dial S, Alrasadi K, Manoukian C, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case-control studies. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):33-38.

5. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:150.

6. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, et al. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86:837-844.

7. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E166-171.

8. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):3153-3163.

9. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238-246.

10. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Long-term kidney outcomes among users of proton pump inhibitors without intervening acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1482-1494.

11. Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336(7634):2-3.

1. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410-416.

2. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0128004.

3. Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006; 296(24):2947-2953.

4. Dial S, Alrasadi K, Manoukian C, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case-control studies. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):33-38.

5. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:150.

6. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, et al. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86:837-844.

7. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E166-171.

8. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):3153-3163.

9. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238-246.

10. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Long-term kidney outcomes among users of proton pump inhibitors without intervening acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1482-1494.

11. Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336(7634):2-3.

Bariatric Surgery for CKD

Q) I know that diabetes can be controlled with bariatric surgery. Is there any proof that it also helps with kidney disease?

With obesity reaching epidemic proportions in the United States, the number of patients undergoing bariatric surgery has increased in recent years. The procedure has been identified as the most effective intervention for the morbidly obese (BMI > 35).1, 2

Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD).3 It causes changes in the kidney, including hyperfiltration, proteinuria, albuminuria, and reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR); however, the underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood.4 Research has demonstrated bariatric surgery’s positive effect on morbidly obese patients with CKD, as well as its benefit for patients with diabetes and hypertension—the two major causes of CKD.1,2

Several studies have found that weight loss resulting from bariatric surgery improves proteinuria, albuminuria, and GFR.2,3,5-9 Findings related to serum creatinine (SCr) have been somewhat conflicting. In severely obese patients, the surgery was associated with a reduction in SCr. This association persisted in those with and without baseline CKD, hypertension, and/or diabetes.5 However, other studies found that the procedure lowered SCr in patients with mild renal impairment (SCr 1.3-1.6 mg/dL) but increased levels in those with moderate renal impairment (SCr > 1.6 mg/dL).10 Because the effects of bariatric surgery on kidney function appear to differ based on CKD stage, further research is needed.

Overall, we can conclude that bariatric surgery has merit as an option to prevent and/or slow progression of early-stage CKD in severely obese patients. Larger, long-term studies are needed to analyze the duration of these effects on kidney outcomes, including the development of end-stage kidney disease. And additional research is needed to determine the risks and benefits associated with bariatric surgery in this population. —ZK-K

Zorica Kauric-Klein, APRN-BC, PhD

Assistant Clinical Professor, College of Nursing, Wayne State University, Detroit

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641-651.

2. Ricci C, Gaeta M, Rausa E, et al. Early impact of bariatric surgery on type II diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression on 6,587 patients. Obes Surg. 2014;24(4):522-528.

3. Bolignano D, Zoccali C. Effects of weight loss on renal function in obese CKD patients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(suppl 4):82-98.

4. Hall ME, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, et al. Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:75-88.

5. Chang AR, Chen Y, Still C, et al. Bariatric surgery is associated with improvement in kidney outcomes. Kidney Int. 2016;90(1):164-171.

6. Ruiz-Tovar J, Giner L, Sarro-Sobrin F, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy prevents the deterioration of renal function in morbidly obese patients over 40 years. Obes Surg. 2015;25(5):796-799.

7. Neff KJ, Baud G, Raverdy V, et al. Renal function and remission of hypertension after bariatric surgery: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):613-619.

8. Nehus EJ, Khoury JC, Inge TH, et al. Kidney outcomes three years after bariatric surgery in severely obese adolescents. Kidney Int. 2017;91(2):451-458.

9. Carlsson LMS, Romeo S, Jacobson P, et al. The incidence of albuminuria after bariatric surgery and usual care in Swedish obese subjects (SOS): a prospective controlled intervention trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(1):169-175.

10. Schuster DP, Teodorescu M, Mikami D, et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on normal and abnormal renal function. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(4):459-464.

Q) I know that diabetes can be controlled with bariatric surgery. Is there any proof that it also helps with kidney disease?

With obesity reaching epidemic proportions in the United States, the number of patients undergoing bariatric surgery has increased in recent years. The procedure has been identified as the most effective intervention for the morbidly obese (BMI > 35).1, 2

Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD).3 It causes changes in the kidney, including hyperfiltration, proteinuria, albuminuria, and reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR); however, the underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood.4 Research has demonstrated bariatric surgery’s positive effect on morbidly obese patients with CKD, as well as its benefit for patients with diabetes and hypertension—the two major causes of CKD.1,2

Several studies have found that weight loss resulting from bariatric surgery improves proteinuria, albuminuria, and GFR.2,3,5-9 Findings related to serum creatinine (SCr) have been somewhat conflicting. In severely obese patients, the surgery was associated with a reduction in SCr. This association persisted in those with and without baseline CKD, hypertension, and/or diabetes.5 However, other studies found that the procedure lowered SCr in patients with mild renal impairment (SCr 1.3-1.6 mg/dL) but increased levels in those with moderate renal impairment (SCr > 1.6 mg/dL).10 Because the effects of bariatric surgery on kidney function appear to differ based on CKD stage, further research is needed.

Overall, we can conclude that bariatric surgery has merit as an option to prevent and/or slow progression of early-stage CKD in severely obese patients. Larger, long-term studies are needed to analyze the duration of these effects on kidney outcomes, including the development of end-stage kidney disease. And additional research is needed to determine the risks and benefits associated with bariatric surgery in this population. —ZK-K

Zorica Kauric-Klein, APRN-BC, PhD

Assistant Clinical Professor, College of Nursing, Wayne State University, Detroit

Q) I know that diabetes can be controlled with bariatric surgery. Is there any proof that it also helps with kidney disease?

With obesity reaching epidemic proportions in the United States, the number of patients undergoing bariatric surgery has increased in recent years. The procedure has been identified as the most effective intervention for the morbidly obese (BMI > 35).1, 2

Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD).3 It causes changes in the kidney, including hyperfiltration, proteinuria, albuminuria, and reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR); however, the underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood.4 Research has demonstrated bariatric surgery’s positive effect on morbidly obese patients with CKD, as well as its benefit for patients with diabetes and hypertension—the two major causes of CKD.1,2

Several studies have found that weight loss resulting from bariatric surgery improves proteinuria, albuminuria, and GFR.2,3,5-9 Findings related to serum creatinine (SCr) have been somewhat conflicting. In severely obese patients, the surgery was associated with a reduction in SCr. This association persisted in those with and without baseline CKD, hypertension, and/or diabetes.5 However, other studies found that the procedure lowered SCr in patients with mild renal impairment (SCr 1.3-1.6 mg/dL) but increased levels in those with moderate renal impairment (SCr > 1.6 mg/dL).10 Because the effects of bariatric surgery on kidney function appear to differ based on CKD stage, further research is needed.

Overall, we can conclude that bariatric surgery has merit as an option to prevent and/or slow progression of early-stage CKD in severely obese patients. Larger, long-term studies are needed to analyze the duration of these effects on kidney outcomes, including the development of end-stage kidney disease. And additional research is needed to determine the risks and benefits associated with bariatric surgery in this population. —ZK-K

Zorica Kauric-Klein, APRN-BC, PhD

Assistant Clinical Professor, College of Nursing, Wayne State University, Detroit

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641-651.

2. Ricci C, Gaeta M, Rausa E, et al. Early impact of bariatric surgery on type II diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression on 6,587 patients. Obes Surg. 2014;24(4):522-528.

3. Bolignano D, Zoccali C. Effects of weight loss on renal function in obese CKD patients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(suppl 4):82-98.

4. Hall ME, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, et al. Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:75-88.

5. Chang AR, Chen Y, Still C, et al. Bariatric surgery is associated with improvement in kidney outcomes. Kidney Int. 2016;90(1):164-171.

6. Ruiz-Tovar J, Giner L, Sarro-Sobrin F, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy prevents the deterioration of renal function in morbidly obese patients over 40 years. Obes Surg. 2015;25(5):796-799.

7. Neff KJ, Baud G, Raverdy V, et al. Renal function and remission of hypertension after bariatric surgery: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):613-619.

8. Nehus EJ, Khoury JC, Inge TH, et al. Kidney outcomes three years after bariatric surgery in severely obese adolescents. Kidney Int. 2017;91(2):451-458.

9. Carlsson LMS, Romeo S, Jacobson P, et al. The incidence of albuminuria after bariatric surgery and usual care in Swedish obese subjects (SOS): a prospective controlled intervention trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(1):169-175.

10. Schuster DP, Teodorescu M, Mikami D, et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on normal and abnormal renal function. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(4):459-464.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641-651.

2. Ricci C, Gaeta M, Rausa E, et al. Early impact of bariatric surgery on type II diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression on 6,587 patients. Obes Surg. 2014;24(4):522-528.

3. Bolignano D, Zoccali C. Effects of weight loss on renal function in obese CKD patients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(suppl 4):82-98.

4. Hall ME, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, et al. Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:75-88.

5. Chang AR, Chen Y, Still C, et al. Bariatric surgery is associated with improvement in kidney outcomes. Kidney Int. 2016;90(1):164-171.

6. Ruiz-Tovar J, Giner L, Sarro-Sobrin F, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy prevents the deterioration of renal function in morbidly obese patients over 40 years. Obes Surg. 2015;25(5):796-799.

7. Neff KJ, Baud G, Raverdy V, et al. Renal function and remission of hypertension after bariatric surgery: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):613-619.

8. Nehus EJ, Khoury JC, Inge TH, et al. Kidney outcomes three years after bariatric surgery in severely obese adolescents. Kidney Int. 2017;91(2):451-458.

9. Carlsson LMS, Romeo S, Jacobson P, et al. The incidence of albuminuria after bariatric surgery and usual care in Swedish obese subjects (SOS): a prospective controlled intervention trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(1):169-175.

10. Schuster DP, Teodorescu M, Mikami D, et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on normal and abnormal renal function. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(4):459-464.

How Low Should You Go? Optimizing BP in CKD

Q) I hear providers quote different numbers for target blood pressure in kidney patients. Which are correct?

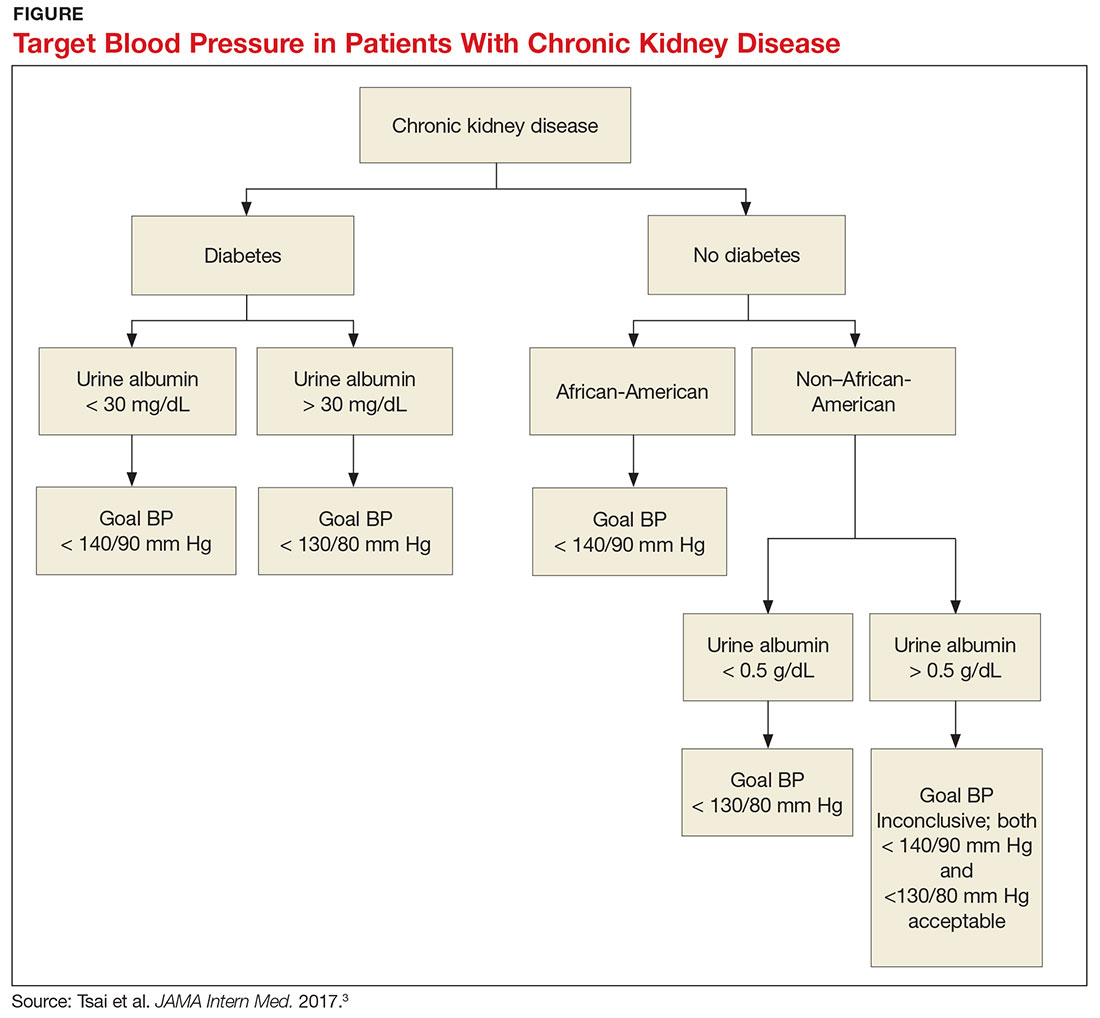

The answer to this question starts with the word “meta-analysis”—but don’t stop reading! We’ll get down to the basics quickly. Determining the goal blood pressure (BP) for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) comes down to three questions.

1. Does the patient have diabetes? The National Kidney Foundation states that the goal BP for a patient with type 2 diabetes, CKD, and urine albumin > 30 mg/dL is < 140/90 mm Hg.1 This is in line with the JNC-8 recommendations for patients with hypertension and CKD, which do not take urine albumin level into consideration.2 It is important to recognize that while many patients with CKD do not have diabetes, those who do have a worse prognosis.3

2. Is the patient African-American? A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials found that lowering BP to < 130/80 mm Hg was linked to a slower decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in non-African-American patients.3 But this BP was not beneficial for African-American patients; in fact, it actually caused a faster decline in GFR.3 Therefore, target BP for African-American patients should be < 140/90 mm Hg.

3. Does the patient have significant albuminuria? An additional subgroup analysis for patients with high levels of proteinuria (defined as > 1 g/d) yielded inconclusive results.3 Patients with proteinuria > 1 g/d tended to have a slower decline in GFR with intensive BP control.3 Proteinuria > 0.5 g/d was correlated with a slowed progression to end-stage renal disease with intensive BP control.3 Again, these were trends and not statistically significant. So, for patients with high levels of proteinuria, it will not hurt to achieve a BP < 130/80 mm Hg, but there is no statistically significant difference between BP < 130/80 mm Hg and BP < 140/90 mm Hg.

What, then, are the recommendations for an African-American patient with significant proteinuria? While not addressed directly in the analysis, the study results suggest that the goal should still be < 140/90 mm Hg, since the link between race and changes in GFR is statistically significant and the effects of proteinuria are not. Although the recommendations from this review are many, the main points are summarized in the Figure.—RC

Rebecca Clawson, MAT, PA-C

Instructor, PA Program, LSU Health Shreveport, Louisiana

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter Suppl. 2013;3(1):1-150.

2. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

3. Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Association of intensive blood pressure control and kidney disease progression in nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:792-799.

Q) I hear providers quote different numbers for target blood pressure in kidney patients. Which are correct?

The answer to this question starts with the word “meta-analysis”—but don’t stop reading! We’ll get down to the basics quickly. Determining the goal blood pressure (BP) for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) comes down to three questions.

1. Does the patient have diabetes? The National Kidney Foundation states that the goal BP for a patient with type 2 diabetes, CKD, and urine albumin > 30 mg/dL is < 140/90 mm Hg.1 This is in line with the JNC-8 recommendations for patients with hypertension and CKD, which do not take urine albumin level into consideration.2 It is important to recognize that while many patients with CKD do not have diabetes, those who do have a worse prognosis.3

2. Is the patient African-American? A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials found that lowering BP to < 130/80 mm Hg was linked to a slower decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in non-African-American patients.3 But this BP was not beneficial for African-American patients; in fact, it actually caused a faster decline in GFR.3 Therefore, target BP for African-American patients should be < 140/90 mm Hg.

3. Does the patient have significant albuminuria? An additional subgroup analysis for patients with high levels of proteinuria (defined as > 1 g/d) yielded inconclusive results.3 Patients with proteinuria > 1 g/d tended to have a slower decline in GFR with intensive BP control.3 Proteinuria > 0.5 g/d was correlated with a slowed progression to end-stage renal disease with intensive BP control.3 Again, these were trends and not statistically significant. So, for patients with high levels of proteinuria, it will not hurt to achieve a BP < 130/80 mm Hg, but there is no statistically significant difference between BP < 130/80 mm Hg and BP < 140/90 mm Hg.

What, then, are the recommendations for an African-American patient with significant proteinuria? While not addressed directly in the analysis, the study results suggest that the goal should still be < 140/90 mm Hg, since the link between race and changes in GFR is statistically significant and the effects of proteinuria are not. Although the recommendations from this review are many, the main points are summarized in the Figure.—RC

Rebecca Clawson, MAT, PA-C

Instructor, PA Program, LSU Health Shreveport, Louisiana

Q) I hear providers quote different numbers for target blood pressure in kidney patients. Which are correct?

The answer to this question starts with the word “meta-analysis”—but don’t stop reading! We’ll get down to the basics quickly. Determining the goal blood pressure (BP) for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) comes down to three questions.

1. Does the patient have diabetes? The National Kidney Foundation states that the goal BP for a patient with type 2 diabetes, CKD, and urine albumin > 30 mg/dL is < 140/90 mm Hg.1 This is in line with the JNC-8 recommendations for patients with hypertension and CKD, which do not take urine albumin level into consideration.2 It is important to recognize that while many patients with CKD do not have diabetes, those who do have a worse prognosis.3

2. Is the patient African-American? A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials found that lowering BP to < 130/80 mm Hg was linked to a slower decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in non-African-American patients.3 But this BP was not beneficial for African-American patients; in fact, it actually caused a faster decline in GFR.3 Therefore, target BP for African-American patients should be < 140/90 mm Hg.

3. Does the patient have significant albuminuria? An additional subgroup analysis for patients with high levels of proteinuria (defined as > 1 g/d) yielded inconclusive results.3 Patients with proteinuria > 1 g/d tended to have a slower decline in GFR with intensive BP control.3 Proteinuria > 0.5 g/d was correlated with a slowed progression to end-stage renal disease with intensive BP control.3 Again, these were trends and not statistically significant. So, for patients with high levels of proteinuria, it will not hurt to achieve a BP < 130/80 mm Hg, but there is no statistically significant difference between BP < 130/80 mm Hg and BP < 140/90 mm Hg.

What, then, are the recommendations for an African-American patient with significant proteinuria? While not addressed directly in the analysis, the study results suggest that the goal should still be < 140/90 mm Hg, since the link between race and changes in GFR is statistically significant and the effects of proteinuria are not. Although the recommendations from this review are many, the main points are summarized in the Figure.—RC

Rebecca Clawson, MAT, PA-C

Instructor, PA Program, LSU Health Shreveport, Louisiana

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter Suppl. 2013;3(1):1-150.

2. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

3. Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Association of intensive blood pressure control and kidney disease progression in nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:792-799.

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter Suppl. 2013;3(1):1-150.

2. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

3. Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Association of intensive blood pressure control and kidney disease progression in nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:792-799.

When to Discontinue RAAS Therapy in CKD Patients

Q) A speaker at a meeting I attended said that ACEis/ARBs can be used in all stages of CKD. But locally, our nephrologists discontinue use when the GFR falls below 20 mL/min. Who is correct?

Definitive data on whether to continue use of ACE inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is lacking.¹ At this time, it is difficult to prove that the renoprotective effects of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors are separate from their antihypertensive effects. Few studies have investigated the effects of RAAS therapy on patients with advanced CKD at baseline (CKD stage 4 or 5; glomerular filtration rate [GFR], < 30 mL/min).2

ACEis and ARBs are indicated for use in CKD patients with hypertension, proteinuria/albuminuria, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and left ventricle dysfunction post–myocardial infarction.3 While these medications are the main pharmacologic therapy for reducing albuminuria in CKD patients, they increase serum creatinine by 20% to 30% and thereby decrease GFR.2,4

The decision to continue or discontinue ACEi/ARB use when patients reach CKD stage 4 or 5 is controversial. On one hand, risks associated with continuation include hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and possible reduction in GFR. The decision to discontinue these medications may result in increased GFR, improved kidney function, and delayed onset of kidney failure or need for dialysis.3,4 In a 2011 study examining outcomes in patients with stage 4 CKD two years after stopping their ACEis/ARBs, the researchers found that patients who were alive without renal replacement therapy were hypertensive but had the highest GFRs.3

On the other hand, ACEis/ARBs have been shown to reduce incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients without CKD. It is widely known that patients with CKD have increased risk for CVD, though there is little data examining the effects of RAAS inhibitors on CVD in this population.¹ A recent study found a reduced risk for fatal CVD in peritoneal dialysis patients treated with ACEis.5 Another study reported improved renal outcomes in nondiabetic patients with advanced CKD who were treated with ACEis.6 The National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guidelines on Hypertension currently state that with careful monitoring, most patients with advanced CKD can continue taking ACEis/ARBs.7

More studies are needed to confidently close this controversial debate. Fortunately, the STOP-ACEi study, a three-year trial that began in 2014 in the UK, is examining the effects of ACEi/ARB use in patients with advanced CKD. It aims to determine whether discontinuation of ACEis/ARBs in these patients can help to stabilize or improve renal function, compared to continued use. By maintaining good blood pressure control in these patients, the researchers hope to distinguish the antihypertensive effects from other potential benefits of the RAAS inhibitors.2 The results of this trial may provide additional clarity for making decisions about ACEi/ARB treatment in our patients with advanced CKD. —RVR, SMR

Rebecca V. Rokosky, MSN, APRN, FNP-BC

Sub Investigator in the Clinical Advancement Center, PPLC, San Antonio, Texas

Shannon M. Rice, MS, PA-C

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego

1. Ahmed A, Jorna T, Bhandari S. Should we STOP angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers in advanced kidney disease? Nephron. 2016; 133(3):147-158.

2. Bhandari S, Ives N, Brettell EA, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker withdrawal in advanced renal disease: the STOP-ACEi trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016; 31(2):255-261.

3. Gonclaves A, Khwaja A, Ahmed A, et al. Stopping renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in chronic kidney disease: predictors of response. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119(4):348-354.

4. Zuber K, Gilmartin C, Davis J. Managing hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAAPA. 2014;27(9):37-46.

5. Shen JI, Saxena AB, Montez-Rath ME, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use and cardiovascular outcomes in patients initiating peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 Apr 13. [Epub ahead of print]

6. Hou F, Zhang X, Zhang GH, et al. Efficacy and safety of benazepril for advanced chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):131-140.

7. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5 suppl 1):S1-S290.

Q) A speaker at a meeting I attended said that ACEis/ARBs can be used in all stages of CKD. But locally, our nephrologists discontinue use when the GFR falls below 20 mL/min. Who is correct?

Definitive data on whether to continue use of ACE inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is lacking.¹ At this time, it is difficult to prove that the renoprotective effects of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors are separate from their antihypertensive effects. Few studies have investigated the effects of RAAS therapy on patients with advanced CKD at baseline (CKD stage 4 or 5; glomerular filtration rate [GFR], < 30 mL/min).2

ACEis and ARBs are indicated for use in CKD patients with hypertension, proteinuria/albuminuria, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and left ventricle dysfunction post–myocardial infarction.3 While these medications are the main pharmacologic therapy for reducing albuminuria in CKD patients, they increase serum creatinine by 20% to 30% and thereby decrease GFR.2,4

The decision to continue or discontinue ACEi/ARB use when patients reach CKD stage 4 or 5 is controversial. On one hand, risks associated with continuation include hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and possible reduction in GFR. The decision to discontinue these medications may result in increased GFR, improved kidney function, and delayed onset of kidney failure or need for dialysis.3,4 In a 2011 study examining outcomes in patients with stage 4 CKD two years after stopping their ACEis/ARBs, the researchers found that patients who were alive without renal replacement therapy were hypertensive but had the highest GFRs.3

On the other hand, ACEis/ARBs have been shown to reduce incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients without CKD. It is widely known that patients with CKD have increased risk for CVD, though there is little data examining the effects of RAAS inhibitors on CVD in this population.¹ A recent study found a reduced risk for fatal CVD in peritoneal dialysis patients treated with ACEis.5 Another study reported improved renal outcomes in nondiabetic patients with advanced CKD who were treated with ACEis.6 The National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guidelines on Hypertension currently state that with careful monitoring, most patients with advanced CKD can continue taking ACEis/ARBs.7

More studies are needed to confidently close this controversial debate. Fortunately, the STOP-ACEi study, a three-year trial that began in 2014 in the UK, is examining the effects of ACEi/ARB use in patients with advanced CKD. It aims to determine whether discontinuation of ACEis/ARBs in these patients can help to stabilize or improve renal function, compared to continued use. By maintaining good blood pressure control in these patients, the researchers hope to distinguish the antihypertensive effects from other potential benefits of the RAAS inhibitors.2 The results of this trial may provide additional clarity for making decisions about ACEi/ARB treatment in our patients with advanced CKD. —RVR, SMR

Rebecca V. Rokosky, MSN, APRN, FNP-BC

Sub Investigator in the Clinical Advancement Center, PPLC, San Antonio, Texas

Shannon M. Rice, MS, PA-C

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego

Q) A speaker at a meeting I attended said that ACEis/ARBs can be used in all stages of CKD. But locally, our nephrologists discontinue use when the GFR falls below 20 mL/min. Who is correct?

Definitive data on whether to continue use of ACE inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is lacking.¹ At this time, it is difficult to prove that the renoprotective effects of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors are separate from their antihypertensive effects. Few studies have investigated the effects of RAAS therapy on patients with advanced CKD at baseline (CKD stage 4 or 5; glomerular filtration rate [GFR], < 30 mL/min).2

ACEis and ARBs are indicated for use in CKD patients with hypertension, proteinuria/albuminuria, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and left ventricle dysfunction post–myocardial infarction.3 While these medications are the main pharmacologic therapy for reducing albuminuria in CKD patients, they increase serum creatinine by 20% to 30% and thereby decrease GFR.2,4

The decision to continue or discontinue ACEi/ARB use when patients reach CKD stage 4 or 5 is controversial. On one hand, risks associated with continuation include hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and possible reduction in GFR. The decision to discontinue these medications may result in increased GFR, improved kidney function, and delayed onset of kidney failure or need for dialysis.3,4 In a 2011 study examining outcomes in patients with stage 4 CKD two years after stopping their ACEis/ARBs, the researchers found that patients who were alive without renal replacement therapy were hypertensive but had the highest GFRs.3

On the other hand, ACEis/ARBs have been shown to reduce incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients without CKD. It is widely known that patients with CKD have increased risk for CVD, though there is little data examining the effects of RAAS inhibitors on CVD in this population.¹ A recent study found a reduced risk for fatal CVD in peritoneal dialysis patients treated with ACEis.5 Another study reported improved renal outcomes in nondiabetic patients with advanced CKD who were treated with ACEis.6 The National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guidelines on Hypertension currently state that with careful monitoring, most patients with advanced CKD can continue taking ACEis/ARBs.7

More studies are needed to confidently close this controversial debate. Fortunately, the STOP-ACEi study, a three-year trial that began in 2014 in the UK, is examining the effects of ACEi/ARB use in patients with advanced CKD. It aims to determine whether discontinuation of ACEis/ARBs in these patients can help to stabilize or improve renal function, compared to continued use. By maintaining good blood pressure control in these patients, the researchers hope to distinguish the antihypertensive effects from other potential benefits of the RAAS inhibitors.2 The results of this trial may provide additional clarity for making decisions about ACEi/ARB treatment in our patients with advanced CKD. —RVR, SMR

Rebecca V. Rokosky, MSN, APRN, FNP-BC

Sub Investigator in the Clinical Advancement Center, PPLC, San Antonio, Texas

Shannon M. Rice, MS, PA-C

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego

1. Ahmed A, Jorna T, Bhandari S. Should we STOP angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers in advanced kidney disease? Nephron. 2016; 133(3):147-158.

2. Bhandari S, Ives N, Brettell EA, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker withdrawal in advanced renal disease: the STOP-ACEi trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016; 31(2):255-261.

3. Gonclaves A, Khwaja A, Ahmed A, et al. Stopping renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in chronic kidney disease: predictors of response. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119(4):348-354.

4. Zuber K, Gilmartin C, Davis J. Managing hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAAPA. 2014;27(9):37-46.

5. Shen JI, Saxena AB, Montez-Rath ME, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use and cardiovascular outcomes in patients initiating peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 Apr 13. [Epub ahead of print]

6. Hou F, Zhang X, Zhang GH, et al. Efficacy and safety of benazepril for advanced chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):131-140.

7. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5 suppl 1):S1-S290.

1. Ahmed A, Jorna T, Bhandari S. Should we STOP angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers in advanced kidney disease? Nephron. 2016; 133(3):147-158.

2. Bhandari S, Ives N, Brettell EA, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker withdrawal in advanced renal disease: the STOP-ACEi trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016; 31(2):255-261.

3. Gonclaves A, Khwaja A, Ahmed A, et al. Stopping renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in chronic kidney disease: predictors of response. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119(4):348-354.

4. Zuber K, Gilmartin C, Davis J. Managing hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAAPA. 2014;27(9):37-46.

5. Shen JI, Saxena AB, Montez-Rath ME, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use and cardiovascular outcomes in patients initiating peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 Apr 13. [Epub ahead of print]

6. Hou F, Zhang X, Zhang GH, et al. Efficacy and safety of benazepril for advanced chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):131-140.

7. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5 suppl 1):S1-S290.

New Drugs to Treat Hyperkalemia

Q)I have heard talk about the development of new drugs to treat hyperkalemia. What is the status of these?