User login

Narrative medicine (NM) centers on understanding patients’ lives, caring for the caregivers (including the clinicians), and giving voice to the suffering.1 It is an antidote for medical “progress,” which often stresses technology and pharmacologic interventions, leaving the patient out of his/her own medical story—with negative consequences.

This missing patient narrative goes beyond the template information solicited and recorded in the history of present illness (HPI) and review of systems (ROS). It is well expressed by Francis W. Peabody, MD, (1881-1927) in a published lecture for Harvard Medical School students: “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is an interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”2

This article serves as an introduction to NM, its evolution, and its power to improve medical diagnoses and reduce clinician burnout. While its roots are in palliative and chronic care, NM has a place in the day-to-day care of patients in acute settings as well.

VIGNETTE

It’s been a busy day in clinic; the clock ticks toward closing. Scanning the monitor, you permit a brief moment of relief as you spy the perfect end-of-shift, quickie patient case: “Sore throat x 2 days,” with a rapid strep test under way. You quickly check lab coat pockets for examination tools and hasten down the hall noting age 22, white female, self-pay. Vitals reveal a low-grade fever. Maybe this sore throat will be bacterial; all the easier as there will be no need to do the “antibiotics don’t work for viruses” sermon.

You knock briefly, enter the exam room, place the laptop on the counter, and immediately recognize the patient from multiple visits over the past 2 years, mostly for gynecologic issues. You recall treating her for gonorrhea and discussing her worry about HIV. She told you that she’s a graduate student, although she is overdressed for a week night, wearing a silk blouse, short skirt, and high heels. She offers a winning smile and tells you with her pleasant accent that she is running late for an appointment.

The patient describes her symptoms: unrelenting sore throat for 2 days and pain with swallowing. She complains of feeling feverish and fatigued, with no appetite and “swollen glands.” She denies cough and runny nose; she looks and sounds exhausted. She denies smoking and excessive alcohol intake. You vaguely hone in on the accent, thinking it might be South African. Her HPI and ROS completed, you record her physical findings of pharyngeal erythema, no exudates, and moderate anterior lymphadenopathy.

You have a nagging thought about her “story.” As an urgent care clinician, you know you are likely her only health care provider and you feel some connection. It is late, and the patient is in a rush, so you promise yourself to delve deeper the next time she presents.

Continue to: You confirm the negative strep test results...

You confirm the negative strep test results and deliver the well-rehearsed sermon. She appears surprised, asking if you are sure. You suggest that she schedule a full physical in the near future. She hops off the table, heels clicking on the tile floor, as you complete your note. You do not suspect she is off to meet her scheduled man of the evening as assigned by her escort service.

Before you clock out, you check the extended patient appointment schedule and do not see her name. You vow to call her the next day and discover that she has no listed phone number. An uncomfortable feeling settles in: Are you missing something?

IN URGENT CARE

NM is an interactive patient approach more often applied to seriously ill or chronic disease patients, for whom it meaningfully supports a patient’s existence as central to the diagnostic testing and treatment of health care concerns. One can professionally debate that NM has no place in urgent care; however, this is where many patients’ acute and chronic conditions are discovered. It is where elevated blood glucose becomes type 2 diabetes and abnormal complete blood counts become blood cancer. With deeper application of NM’s principles, our simple-appearing acute pharyngitis case might have received a different workup.

NM practitioners subscribe to careful listening. Rita Charon, MD, a leading proponent of NM, describes this approach to patient care as a “rigorous intellectual and clinical discipline to fortify health care with its capacity to skillfully receive the accounts persons give of themselves—to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved to action by the stories of others.”3 It is a patient care revival that helps clinicians recognize and shield themselves from the powerful stampede of technology, templated patient interviews, digital documentation, and diminution of clinician and patient bonding.

The clinician in this patient encounter has functionally intact radar, sensing something awry, but communication falls short. NM’s strength is to bond the clinician to the patient, enhancing subtle, and at times pivotal, information exchange. It generates patient trust even in brief encounters, fostering improved clinical decision-making. A stronger NM focus might have encouraged this clinician to investigate more deeply the patient’s fancy clothing and surprised response to the negative strep test results by posing a simple query, such as ”What do you think might be going on?”

Continue to: MEDICAL ERROR

MEDICAL ERROR

Pharyngitis is common, making it prime territory for medical error—even for experienced clinicians—because of 3 human tendencies that NM recognizes and seeks to avoid.4 These human tendencies, insightfully delineated decades ago by experimental psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, authors of Anchoring, Availability and Attribution, appear most commonly under uncertain conditions and time pressures, such as in urgent care. How does this patient encounter reflect these tendencies?5

Anchoring refers to the tendency to grasp the first symptom, physical finding, or laboratory abnormality, and hold onto it tightly.5 Such initial diagnostic impressions/information may prove true; however, other unconsidered diagnoses may include the correct one. In this encounter, the clinician entered the exam room with an early fixed diagnosis and applied the rapid strep results to diagnose viral pharyngitis. Other, conflicting hints were fleetingly noted and not addressed.

Availability refers to the tendency to assume that a quickly recalled experience explains a novel situation.5 Clinicians regularly diagnose viral pharyngitis, leading to familiarity and availability. This is contrary to NM’s view of every patient having a unique and noteworthy story.

Attribution refers to the tendency to invoke stereotypical images and assign symptoms and findings to the stereotype, which is often negative (eg, hypochondriac, drinker).5

In this encounter, the clinician would have benefited from considering other categories of diagnoses that could occur in this patient, expanding the differential diagnosis list, by soliciting a deeper patient story, fostering trust, and following clinical intuition. Had this bond been cultivated over prior visits, even in an urgent care setting, the graduate student ruse would have been discovered and the patient’s true occupation—female sex worker—revealed. The clinician would have modified the laboratory testing, discovering human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8) as the pharyngitis etiology, which is disproportionately linked to HIV co-infection and increases the risk for Kaposi sarcoma (KS) 20,000-fold. The prevalence of HHV-8 is 17% in the United States and is much higher (50%) in South Africa, the origin of the patient’s accent.6 Deeper patient relationships enable uncomfortable history-taking questions, with improved reliability. This missed diagnosis has wide-ranging negative consequences for the patient and her escort encounters.6

Continue to: THE FLEXNER REPORT

THE FLEXNER REPORT: NARRATIVE MEDICINE'S EXCISION

It is clear that the scientific revolution prompted the removal of NM from clinical practice. The 1910 Flexner Report, funded by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Science and authored by research scholar and physician Abraham Flexner, analyzed the functioning of 155 US and Canadian medical schools.7 His report supported the socially desirable goal of reforming medical education by exposing mediocre quality, unsavory profit motives, inadequate facilities, and nonscientific approaches, and publishing a list of those falling below the gold standard (which was the German medical education system). Harvard and Johns Hopkins received a gold seal, many other medical schools closed, and several responded to the challenge and excelled.8

Medical school curricula transitioned to exclusively theoretical and scientific teaching, objectifying values and rewarding research and efficiency. The subjective patient story was surgically excised and replaced with objective science. Not all change is good, however, and years later, Flexner reflected that scientific medicine was “sadly deficient in cultural and philosophic background.”8 His report also dramatically suppressed the use of complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry, another medical boomerang.9 Scientific rigor is desirable—but not to the exclusion of the central patient role and other potential health care modalities.

THE PROBLEM-ORIENTED MEDICAL RECORD AND EHR

Decades after Flexner’s report on medical education curricula, another reformer, Lawrence Weed, MD, trained his eye on medical documentation’s organization and structure. He published a seminal article, “Medical Records that Guide and Teach” in the New England Journal of Medicine.10 Truly a pioneer, he demonstrated how typical medical record case documentation circa 1967 could be more efficient and espoused the problem-oriented medical record. He conceptualized designs for reorganizing medical records, prophetically promoted use of “paramedical” personnel, and encouraged computer integration.10

Coinciding with the birth of the PA profession and the recent inception of the NP profession, Weed endorsed the use of trained interviewers who would apply a “branching” question algorithm with associated computer data entry designed to protect expensive physician time. The patient story would be a jigsaw puzzle, as physicians could fill in missing information.10

Weed’s goals had merit by stressing structure for the disorganized, then-handwritten medical record, benefitting the growth of team-based patient care. However, efficiency and precision continued to marginalize a key component of the patient’s illness narrative in favor of speed, objectivity, and achievable billing essentials.11 His recommendations have eradicated the free-text box, replacing it with a selection of pull-down choices or prewritten templates. With a series of clicks, the subjective patient’s own narrative is sterilized, removing valuable details from the team’s view.11 The “s” of the Subjective Objective Assessment and Plan note is washed away (Table 1).

Continue to: Weed's clinical documentation...

Weed’s clinical documentation efficiency system caught fire. However, similar to Flexner’s later second thoughts, Weed also cast doubt on the full effect of his recommendations. In a 2009 interview conducted by a former medical student of his, Weed revealed views that more closely resemble our current competency-based medical education and stress the value of interpersonal skills in patient care12:

- Computerization of the medical record—with its vast amount of information and physician-processing capacity—“inevitably” leads to dangerous cognitive shortcuts. Medical education seeks to instill “medical knowledge and clinical judgment,” giving students “misplaced faith in the completeness and accuracy of their own intellects and is the antithesis of a truly scientific education.”12

- Medical student recruitment and instruction have long emphasized memory and regurgitation of facts, while students should be selected for their hands-on and interpersonal skills. Medical school should be “teaching a core of behavior instead of a core of knowledge.”12 These are areas in which NM helps.

FLEXNER, WEED, AND NOW, CHARON

Medicine’s history is blemished by errors, some significant. Flexner neatly compartmentalized medical education, Weed digitized the clinician/patient interaction, and Charon revitalizes the reason clinicians chose a health care profession. Charon—as a practicing internist, as well as a professor in the Department of Medicine and Executive Director of the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City—is fully qualified to speak to the importance of NM in medical education and medical practice. Her 2006 book reminds us that sore throats are not always simple, boring, and routine; each one is as unique as the person housing that particular pharynx.13

How does NM drive clinicians to be better, countering cognitive errors while incorporating the patient’s cultural and philosophic background? According to Charon, the NM concept results from conversation among scholars and clinicians teaching and practicing at Columbia University in early 2000, fueled by decades of insight from literature, medical (health care) humanities, ethics, health care communication, and primary care medicine.3 NM supports patient-centric teaching and care, reminding us that it combines the historical doctor-at-bedside, who exhibited careful, empathetic questioning and listening, with the benefits of modern medical science.

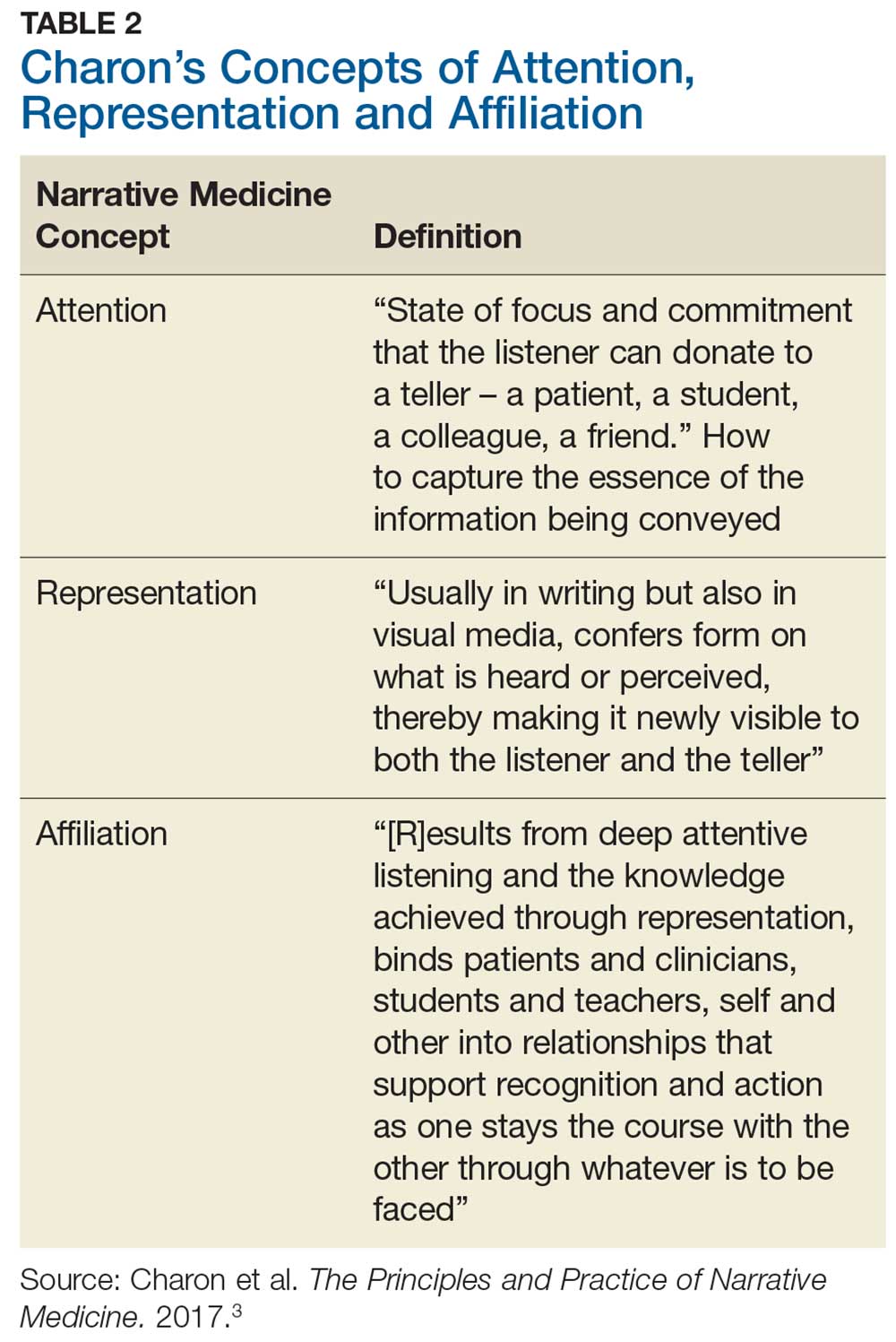

Charon describes 3 main clinician-to-patient interactions, allowing us to regain some of what we have lost: attention, representation, and affiliation (Table 2). In addition to medical error reduction, these 3 interactive behaviors counter the aforementioned 3As (anchoring, availability, and attribution) of cognitive error.5Attention initiates the clinician’s heightened and committed listening to the patient.3 In our patient encounter, essential information is undisclosed, leading to a missed diagnosis and an incomplete representation in the written note. The clinician, due to insufficient attention, missed important clues such as the patient’s dress, accent, and profession, which limited the representation. This almost seems nonsensical; who would care about a patient’s dress or accent and, of practical concern today, where would one record it? And could another urgent care clinician or specialist find these notes? How might a more serious future medical outcome be averted? Affiliation results in a connection of careful listening and full documentation as the clinician becomes invested in the whole patient, not just the sore throat.3

PREPROFESSIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

Preprofessional humanities education may result in stronger NM conceptualization. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recognizes the value of arts and humanities in medical education in developing qualities of professionalism, communication skills, and emotional intelligence in physicians. The AAMC Curriculum Inventory and Reports (2015-2016) shows that 119 medical schools require humanities education, including

- Visual arts to improve observational skills

- History education to frame modern-day Ebola outbreaks (eg, using the framework of the Black Death),

- Literature and poetry to enhance insight into different ways of living and thinking, fostering critical thinking.14

Continue to: NM has been offered in...

NM has been offered in medical schools with positive outcomes. Published results of a 2010 qualitative study of 130 Columbia University medical students who completed a required intensive half-semester of NM seminars testify to its salience.15 Students articulated NM’s importance to critical thinking and reflection, through improved attention and affiliation with their patients, improved ability to examine assumptions and develop new skills, and improved clarity of communication.15

A small number of PA programs, far fewer than medical schools, are incorporating NM coursework, through application of literature, visual media, creative writing, and other approaches based on the humanities.16 The nursing profession, which prefers the term narrative health care to narrative medicine, endorses its inclusion in nursing education. A 2018 article in Nursing Education Perspectives supports the study of humanities to complement technical competencies such as the ability to “absorb, analyze, and interpret complex artifacts” and to “participate effectively in deliberative conversations.”17

THE PRACTICING CLINICIAN: MENTAL HEALTH AND NARRATIVE MEDICINE

The value of NM extends beyond the patient to embrace caregivers as well; this is important, in light of increased attention to mental health status among clinicians. Although the term used most frequently is physician burnout, data indicate that patient management by MDs, NPs, and PAs is becoming indistinguishable—and thus risk for associated negative mental health consequences may be shared

The National Academy of Medicine is also addressing the issues of clinician well-being (see https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/). Former US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, has spoken about the epidemic of loneliness that affects clinicians. This can result from playing the physician role, lack of family support, and increased dependency on technology—yet, on a basic level, lack of interpersonal communication and connection are at the core.21 Communication between clinicians can lead to greater social cohesion and compassion, and effective uninterrupted listening and expression of their feelings helps. This begs the question: If physicians need to communicate better and practice active listening among themselves, how does this translate to the physician-to-patient bond?

THE CLINICIANS' PERSONAL BALM

Caruso Brown and Garden describe how the illness experiences of physicians, through their own reflective writing, create an empathy bridge between the professional healer and a sick patient, allowing them to be better and healthier clinicians.22 Recent best-selling physician narratives such as those by Atul Gawande,23 Siddhartha Mukherjee,24 and Paul Kalanithi25 support the similarities between the sick physician and the sick patient. Illness narratives written by physicians-turned-patients are not dissimilar to illness narratives written by patients. Reflective writing by clinicians fosters a deeper understanding not only of how patients feel, but also of the relationship they desire and deserve.22

Continue to: Writing a novel...

Writing a novel is beyond the time and ability of many clinicians. However, they can closely read literature (another NM tool), discuss books and other types of writing, participate in a book club, establish a hospital or office support group, and find a buddy or trustworthy confidant with whom to decompress and vent.3 Active journal clubs can alternate clinical guidelines with literature to expand their perspectives. An international voice, Maria Giulia Marini, Research and Health Director of the Fondazione ISTUD in Milan, Italy, and European proponent of NM, offers similar suggestions, indicating that making nonmedical works parts of a clinician’s life encourages empathy and promotes understanding between clinician and patient, as well as a holistic management approach, encourages personal and collegial reflection (eg, sharing tough experiences), sets a patient-centered agenda, and challenges the norm.26

NARRATIVE MEDICINE'S FUTURE ROLE

The field of medical humanities has experienced growth through publications, national and international conferences, and formal discussion between executives of the AAMC and the National Endowment for the Humanities to design and incorporate joint programs teaching humanities in medical schools.27 As of March 2019, there were 85 established baccalaureate health humanities programs in the US, with additional programs in development.28

Clinicians and professional organizations cannot help but see the suffering of patients, with its concomitant provider burden. The urgent care patient encounter in our example met the standard of care of the typical interaction that achieves billing protocols; the HPI, ROS, and physical exam would not raise an eyebrow. Yet, an NM approach provides more. Asking the atypical questions about accents, out-of-the-ordinary dress and behavior, and wondering about the mentioned late-night appointment attends to NM’s focused active listening, with resultant quality documentation and a whole patient encounter, even in an acute care case.

Don’t be afraid. Consider that as in novels and movies, strange things happen. The iconic book The House of God reminds clinicians that, upon hearing hoof beats, we should first think of horses—however, sometimes a zebra is correct.29 When an urgent care clinician interprets the hoof beats, a zebra may be in the differential diagnosis; in the case presented, the patient might fortunately be spared a future KS diagnosis. And the clinician may avoid personal anguish at what could have been a better outcome. NM can help clinicians remember that sore throats are as unique as people.

1. Krisberg K. Narrative medicine: Every patient has a story. AAMC News. March 28, 2018. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/narrative-medicine-every-patient-has-story. Accessed October 10, 2018.

2. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;80(12):877-882.

3. Charon R, DasGupta S, Hermann N, et al. The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017:1, 3.

4. Murphy JG , Stee LA, McAvoy MT, Oshiro J. Journal reporting of medical errors: the wisdom of Solomon, the bravery of Achilles, and the foolishness of Pan. Chest. 2007;131(3):890-896.

5. Groopman J, Hartzband P. Mindful medicine: Critical thinking leads to right diagnosis. ACP Internist. January 2008. https://acpinternist.org/archives/2008/01/groopman.htm. Accessed May 11, 2018.

6. Nzivo MM, Lwembe RM, Odari EO, Budambula NLM. Human herpes virus type 8 among female-sex workers. J Hum Virol Retrovirol 2017;5(6):00176.

7. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada—a report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin No. 4. Boston, MA: DB Updike, Merrymount Press; 1910.

8. Cooke M, Irby DM, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner Report. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1339-1344.

9. Stahnisch FW, Verhoef M. The Flexner Report of 1910 and its impact on complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry in North America in the 20th Century. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:647896.

10. Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. NEJM. 1968;278(12):652-657.

11. Ommaya AK, Cipriano PF, Hoyt DB, et al. Care-centered clinical documentation in the digital environment: solutions to alleviate burnout. NAM.edu/Perspectives. January 29, 2018. Accessed June 19, 2018.

12. Jacobs L. Interview with Lawrence Weed, MD - The father of the problem-oriented medical record looks ahead. The Permanente Journal. Summer 2009;13(3):84-89. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/09-068. Accessed August 2, 2019.

13. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

14. Mann S. Focusing on arts, humanities to develop well-rounded physicians. AAMC News. August 15, 2017. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/focusing-arts-humanities-well-rounded-physicians/. Accessed Oct 10, 2018.

15. Miller E, Balmer D, Hermann N, et al. Sounding narrative medicine: studying students’ professional identity development at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):335-342.

16. Grant JP, Gregory T. The Sacred Seven elective: integrating the health humanities into physician assistant education. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28(4):220-222.

17. Lim F, Marsaglia MJ. Nursing humanities: teaching for a sense of salience. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2018;39(2):121-122.

18. Hooker RS. PAs, NPs, PAs, physicians and regression to the mean. JAAPA. 2018;31(7):13-14.

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;338:2272-2281.

20. Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, et al. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “Being connected … a key to my survival.” JAMA. 2009;301(11):1155–1164, E1.

21. Firth S. Former Surgeon General talks love, loneliness, and burnout: NAM panel addresses growing crisis in medicine. Medpage Today. May 4, 2018. www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/generalprofessionalissues/72720. Accessed June 15, 2018.

22. Caruso Brown AE, Garden R. Images of healing and learning: from silence into language: Questioning the power of physician illness narratives. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(5):501-507.

23. Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. 1st ed. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2014.

24. Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2010.

25. Kalanithi P. When Breath Becomes Air. New York, NY: Penguin Random House; 2016.

26. Marini MG. Narrative Medicine: Bridging the Gap Between Evidence-Based Care and Medical Humanities. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

27. Charon R. To see the suffering. Acad Med. 2017;92(12):1668-1670.

28. Lamb EG, Berry SL, Jones T. Health Humanities Baccalaureate Programs in the United States. Hiram, OH: Center for Literature and Medicine, Hiram College; March 2019.

29. Shem S. The House of God. New York, NY: Berkley Random House; 1978.

Narrative medicine (NM) centers on understanding patients’ lives, caring for the caregivers (including the clinicians), and giving voice to the suffering.1 It is an antidote for medical “progress,” which often stresses technology and pharmacologic interventions, leaving the patient out of his/her own medical story—with negative consequences.

This missing patient narrative goes beyond the template information solicited and recorded in the history of present illness (HPI) and review of systems (ROS). It is well expressed by Francis W. Peabody, MD, (1881-1927) in a published lecture for Harvard Medical School students: “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is an interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”2

This article serves as an introduction to NM, its evolution, and its power to improve medical diagnoses and reduce clinician burnout. While its roots are in palliative and chronic care, NM has a place in the day-to-day care of patients in acute settings as well.

VIGNETTE

It’s been a busy day in clinic; the clock ticks toward closing. Scanning the monitor, you permit a brief moment of relief as you spy the perfect end-of-shift, quickie patient case: “Sore throat x 2 days,” with a rapid strep test under way. You quickly check lab coat pockets for examination tools and hasten down the hall noting age 22, white female, self-pay. Vitals reveal a low-grade fever. Maybe this sore throat will be bacterial; all the easier as there will be no need to do the “antibiotics don’t work for viruses” sermon.

You knock briefly, enter the exam room, place the laptop on the counter, and immediately recognize the patient from multiple visits over the past 2 years, mostly for gynecologic issues. You recall treating her for gonorrhea and discussing her worry about HIV. She told you that she’s a graduate student, although she is overdressed for a week night, wearing a silk blouse, short skirt, and high heels. She offers a winning smile and tells you with her pleasant accent that she is running late for an appointment.

The patient describes her symptoms: unrelenting sore throat for 2 days and pain with swallowing. She complains of feeling feverish and fatigued, with no appetite and “swollen glands.” She denies cough and runny nose; she looks and sounds exhausted. She denies smoking and excessive alcohol intake. You vaguely hone in on the accent, thinking it might be South African. Her HPI and ROS completed, you record her physical findings of pharyngeal erythema, no exudates, and moderate anterior lymphadenopathy.

You have a nagging thought about her “story.” As an urgent care clinician, you know you are likely her only health care provider and you feel some connection. It is late, and the patient is in a rush, so you promise yourself to delve deeper the next time she presents.

Continue to: You confirm the negative strep test results...

You confirm the negative strep test results and deliver the well-rehearsed sermon. She appears surprised, asking if you are sure. You suggest that she schedule a full physical in the near future. She hops off the table, heels clicking on the tile floor, as you complete your note. You do not suspect she is off to meet her scheduled man of the evening as assigned by her escort service.

Before you clock out, you check the extended patient appointment schedule and do not see her name. You vow to call her the next day and discover that she has no listed phone number. An uncomfortable feeling settles in: Are you missing something?

IN URGENT CARE

NM is an interactive patient approach more often applied to seriously ill or chronic disease patients, for whom it meaningfully supports a patient’s existence as central to the diagnostic testing and treatment of health care concerns. One can professionally debate that NM has no place in urgent care; however, this is where many patients’ acute and chronic conditions are discovered. It is where elevated blood glucose becomes type 2 diabetes and abnormal complete blood counts become blood cancer. With deeper application of NM’s principles, our simple-appearing acute pharyngitis case might have received a different workup.

NM practitioners subscribe to careful listening. Rita Charon, MD, a leading proponent of NM, describes this approach to patient care as a “rigorous intellectual and clinical discipline to fortify health care with its capacity to skillfully receive the accounts persons give of themselves—to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved to action by the stories of others.”3 It is a patient care revival that helps clinicians recognize and shield themselves from the powerful stampede of technology, templated patient interviews, digital documentation, and diminution of clinician and patient bonding.

The clinician in this patient encounter has functionally intact radar, sensing something awry, but communication falls short. NM’s strength is to bond the clinician to the patient, enhancing subtle, and at times pivotal, information exchange. It generates patient trust even in brief encounters, fostering improved clinical decision-making. A stronger NM focus might have encouraged this clinician to investigate more deeply the patient’s fancy clothing and surprised response to the negative strep test results by posing a simple query, such as ”What do you think might be going on?”

Continue to: MEDICAL ERROR

MEDICAL ERROR

Pharyngitis is common, making it prime territory for medical error—even for experienced clinicians—because of 3 human tendencies that NM recognizes and seeks to avoid.4 These human tendencies, insightfully delineated decades ago by experimental psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, authors of Anchoring, Availability and Attribution, appear most commonly under uncertain conditions and time pressures, such as in urgent care. How does this patient encounter reflect these tendencies?5

Anchoring refers to the tendency to grasp the first symptom, physical finding, or laboratory abnormality, and hold onto it tightly.5 Such initial diagnostic impressions/information may prove true; however, other unconsidered diagnoses may include the correct one. In this encounter, the clinician entered the exam room with an early fixed diagnosis and applied the rapid strep results to diagnose viral pharyngitis. Other, conflicting hints were fleetingly noted and not addressed.

Availability refers to the tendency to assume that a quickly recalled experience explains a novel situation.5 Clinicians regularly diagnose viral pharyngitis, leading to familiarity and availability. This is contrary to NM’s view of every patient having a unique and noteworthy story.

Attribution refers to the tendency to invoke stereotypical images and assign symptoms and findings to the stereotype, which is often negative (eg, hypochondriac, drinker).5

In this encounter, the clinician would have benefited from considering other categories of diagnoses that could occur in this patient, expanding the differential diagnosis list, by soliciting a deeper patient story, fostering trust, and following clinical intuition. Had this bond been cultivated over prior visits, even in an urgent care setting, the graduate student ruse would have been discovered and the patient’s true occupation—female sex worker—revealed. The clinician would have modified the laboratory testing, discovering human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8) as the pharyngitis etiology, which is disproportionately linked to HIV co-infection and increases the risk for Kaposi sarcoma (KS) 20,000-fold. The prevalence of HHV-8 is 17% in the United States and is much higher (50%) in South Africa, the origin of the patient’s accent.6 Deeper patient relationships enable uncomfortable history-taking questions, with improved reliability. This missed diagnosis has wide-ranging negative consequences for the patient and her escort encounters.6

Continue to: THE FLEXNER REPORT

THE FLEXNER REPORT: NARRATIVE MEDICINE'S EXCISION

It is clear that the scientific revolution prompted the removal of NM from clinical practice. The 1910 Flexner Report, funded by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Science and authored by research scholar and physician Abraham Flexner, analyzed the functioning of 155 US and Canadian medical schools.7 His report supported the socially desirable goal of reforming medical education by exposing mediocre quality, unsavory profit motives, inadequate facilities, and nonscientific approaches, and publishing a list of those falling below the gold standard (which was the German medical education system). Harvard and Johns Hopkins received a gold seal, many other medical schools closed, and several responded to the challenge and excelled.8

Medical school curricula transitioned to exclusively theoretical and scientific teaching, objectifying values and rewarding research and efficiency. The subjective patient story was surgically excised and replaced with objective science. Not all change is good, however, and years later, Flexner reflected that scientific medicine was “sadly deficient in cultural and philosophic background.”8 His report also dramatically suppressed the use of complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry, another medical boomerang.9 Scientific rigor is desirable—but not to the exclusion of the central patient role and other potential health care modalities.

THE PROBLEM-ORIENTED MEDICAL RECORD AND EHR

Decades after Flexner’s report on medical education curricula, another reformer, Lawrence Weed, MD, trained his eye on medical documentation’s organization and structure. He published a seminal article, “Medical Records that Guide and Teach” in the New England Journal of Medicine.10 Truly a pioneer, he demonstrated how typical medical record case documentation circa 1967 could be more efficient and espoused the problem-oriented medical record. He conceptualized designs for reorganizing medical records, prophetically promoted use of “paramedical” personnel, and encouraged computer integration.10

Coinciding with the birth of the PA profession and the recent inception of the NP profession, Weed endorsed the use of trained interviewers who would apply a “branching” question algorithm with associated computer data entry designed to protect expensive physician time. The patient story would be a jigsaw puzzle, as physicians could fill in missing information.10

Weed’s goals had merit by stressing structure for the disorganized, then-handwritten medical record, benefitting the growth of team-based patient care. However, efficiency and precision continued to marginalize a key component of the patient’s illness narrative in favor of speed, objectivity, and achievable billing essentials.11 His recommendations have eradicated the free-text box, replacing it with a selection of pull-down choices or prewritten templates. With a series of clicks, the subjective patient’s own narrative is sterilized, removing valuable details from the team’s view.11 The “s” of the Subjective Objective Assessment and Plan note is washed away (Table 1).

Continue to: Weed's clinical documentation...

Weed’s clinical documentation efficiency system caught fire. However, similar to Flexner’s later second thoughts, Weed also cast doubt on the full effect of his recommendations. In a 2009 interview conducted by a former medical student of his, Weed revealed views that more closely resemble our current competency-based medical education and stress the value of interpersonal skills in patient care12:

- Computerization of the medical record—with its vast amount of information and physician-processing capacity—“inevitably” leads to dangerous cognitive shortcuts. Medical education seeks to instill “medical knowledge and clinical judgment,” giving students “misplaced faith in the completeness and accuracy of their own intellects and is the antithesis of a truly scientific education.”12

- Medical student recruitment and instruction have long emphasized memory and regurgitation of facts, while students should be selected for their hands-on and interpersonal skills. Medical school should be “teaching a core of behavior instead of a core of knowledge.”12 These are areas in which NM helps.

FLEXNER, WEED, AND NOW, CHARON

Medicine’s history is blemished by errors, some significant. Flexner neatly compartmentalized medical education, Weed digitized the clinician/patient interaction, and Charon revitalizes the reason clinicians chose a health care profession. Charon—as a practicing internist, as well as a professor in the Department of Medicine and Executive Director of the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City—is fully qualified to speak to the importance of NM in medical education and medical practice. Her 2006 book reminds us that sore throats are not always simple, boring, and routine; each one is as unique as the person housing that particular pharynx.13

How does NM drive clinicians to be better, countering cognitive errors while incorporating the patient’s cultural and philosophic background? According to Charon, the NM concept results from conversation among scholars and clinicians teaching and practicing at Columbia University in early 2000, fueled by decades of insight from literature, medical (health care) humanities, ethics, health care communication, and primary care medicine.3 NM supports patient-centric teaching and care, reminding us that it combines the historical doctor-at-bedside, who exhibited careful, empathetic questioning and listening, with the benefits of modern medical science.

Charon describes 3 main clinician-to-patient interactions, allowing us to regain some of what we have lost: attention, representation, and affiliation (Table 2). In addition to medical error reduction, these 3 interactive behaviors counter the aforementioned 3As (anchoring, availability, and attribution) of cognitive error.5Attention initiates the clinician’s heightened and committed listening to the patient.3 In our patient encounter, essential information is undisclosed, leading to a missed diagnosis and an incomplete representation in the written note. The clinician, due to insufficient attention, missed important clues such as the patient’s dress, accent, and profession, which limited the representation. This almost seems nonsensical; who would care about a patient’s dress or accent and, of practical concern today, where would one record it? And could another urgent care clinician or specialist find these notes? How might a more serious future medical outcome be averted? Affiliation results in a connection of careful listening and full documentation as the clinician becomes invested in the whole patient, not just the sore throat.3

PREPROFESSIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

Preprofessional humanities education may result in stronger NM conceptualization. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recognizes the value of arts and humanities in medical education in developing qualities of professionalism, communication skills, and emotional intelligence in physicians. The AAMC Curriculum Inventory and Reports (2015-2016) shows that 119 medical schools require humanities education, including

- Visual arts to improve observational skills

- History education to frame modern-day Ebola outbreaks (eg, using the framework of the Black Death),

- Literature and poetry to enhance insight into different ways of living and thinking, fostering critical thinking.14

Continue to: NM has been offered in...

NM has been offered in medical schools with positive outcomes. Published results of a 2010 qualitative study of 130 Columbia University medical students who completed a required intensive half-semester of NM seminars testify to its salience.15 Students articulated NM’s importance to critical thinking and reflection, through improved attention and affiliation with their patients, improved ability to examine assumptions and develop new skills, and improved clarity of communication.15

A small number of PA programs, far fewer than medical schools, are incorporating NM coursework, through application of literature, visual media, creative writing, and other approaches based on the humanities.16 The nursing profession, which prefers the term narrative health care to narrative medicine, endorses its inclusion in nursing education. A 2018 article in Nursing Education Perspectives supports the study of humanities to complement technical competencies such as the ability to “absorb, analyze, and interpret complex artifacts” and to “participate effectively in deliberative conversations.”17

THE PRACTICING CLINICIAN: MENTAL HEALTH AND NARRATIVE MEDICINE

The value of NM extends beyond the patient to embrace caregivers as well; this is important, in light of increased attention to mental health status among clinicians. Although the term used most frequently is physician burnout, data indicate that patient management by MDs, NPs, and PAs is becoming indistinguishable—and thus risk for associated negative mental health consequences may be shared

The National Academy of Medicine is also addressing the issues of clinician well-being (see https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/). Former US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, has spoken about the epidemic of loneliness that affects clinicians. This can result from playing the physician role, lack of family support, and increased dependency on technology—yet, on a basic level, lack of interpersonal communication and connection are at the core.21 Communication between clinicians can lead to greater social cohesion and compassion, and effective uninterrupted listening and expression of their feelings helps. This begs the question: If physicians need to communicate better and practice active listening among themselves, how does this translate to the physician-to-patient bond?

THE CLINICIANS' PERSONAL BALM

Caruso Brown and Garden describe how the illness experiences of physicians, through their own reflective writing, create an empathy bridge between the professional healer and a sick patient, allowing them to be better and healthier clinicians.22 Recent best-selling physician narratives such as those by Atul Gawande,23 Siddhartha Mukherjee,24 and Paul Kalanithi25 support the similarities between the sick physician and the sick patient. Illness narratives written by physicians-turned-patients are not dissimilar to illness narratives written by patients. Reflective writing by clinicians fosters a deeper understanding not only of how patients feel, but also of the relationship they desire and deserve.22

Continue to: Writing a novel...

Writing a novel is beyond the time and ability of many clinicians. However, they can closely read literature (another NM tool), discuss books and other types of writing, participate in a book club, establish a hospital or office support group, and find a buddy or trustworthy confidant with whom to decompress and vent.3 Active journal clubs can alternate clinical guidelines with literature to expand their perspectives. An international voice, Maria Giulia Marini, Research and Health Director of the Fondazione ISTUD in Milan, Italy, and European proponent of NM, offers similar suggestions, indicating that making nonmedical works parts of a clinician’s life encourages empathy and promotes understanding between clinician and patient, as well as a holistic management approach, encourages personal and collegial reflection (eg, sharing tough experiences), sets a patient-centered agenda, and challenges the norm.26

NARRATIVE MEDICINE'S FUTURE ROLE

The field of medical humanities has experienced growth through publications, national and international conferences, and formal discussion between executives of the AAMC and the National Endowment for the Humanities to design and incorporate joint programs teaching humanities in medical schools.27 As of March 2019, there were 85 established baccalaureate health humanities programs in the US, with additional programs in development.28

Clinicians and professional organizations cannot help but see the suffering of patients, with its concomitant provider burden. The urgent care patient encounter in our example met the standard of care of the typical interaction that achieves billing protocols; the HPI, ROS, and physical exam would not raise an eyebrow. Yet, an NM approach provides more. Asking the atypical questions about accents, out-of-the-ordinary dress and behavior, and wondering about the mentioned late-night appointment attends to NM’s focused active listening, with resultant quality documentation and a whole patient encounter, even in an acute care case.

Don’t be afraid. Consider that as in novels and movies, strange things happen. The iconic book The House of God reminds clinicians that, upon hearing hoof beats, we should first think of horses—however, sometimes a zebra is correct.29 When an urgent care clinician interprets the hoof beats, a zebra may be in the differential diagnosis; in the case presented, the patient might fortunately be spared a future KS diagnosis. And the clinician may avoid personal anguish at what could have been a better outcome. NM can help clinicians remember that sore throats are as unique as people.

Narrative medicine (NM) centers on understanding patients’ lives, caring for the caregivers (including the clinicians), and giving voice to the suffering.1 It is an antidote for medical “progress,” which often stresses technology and pharmacologic interventions, leaving the patient out of his/her own medical story—with negative consequences.

This missing patient narrative goes beyond the template information solicited and recorded in the history of present illness (HPI) and review of systems (ROS). It is well expressed by Francis W. Peabody, MD, (1881-1927) in a published lecture for Harvard Medical School students: “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is an interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”2

This article serves as an introduction to NM, its evolution, and its power to improve medical diagnoses and reduce clinician burnout. While its roots are in palliative and chronic care, NM has a place in the day-to-day care of patients in acute settings as well.

VIGNETTE

It’s been a busy day in clinic; the clock ticks toward closing. Scanning the monitor, you permit a brief moment of relief as you spy the perfect end-of-shift, quickie patient case: “Sore throat x 2 days,” with a rapid strep test under way. You quickly check lab coat pockets for examination tools and hasten down the hall noting age 22, white female, self-pay. Vitals reveal a low-grade fever. Maybe this sore throat will be bacterial; all the easier as there will be no need to do the “antibiotics don’t work for viruses” sermon.

You knock briefly, enter the exam room, place the laptop on the counter, and immediately recognize the patient from multiple visits over the past 2 years, mostly for gynecologic issues. You recall treating her for gonorrhea and discussing her worry about HIV. She told you that she’s a graduate student, although she is overdressed for a week night, wearing a silk blouse, short skirt, and high heels. She offers a winning smile and tells you with her pleasant accent that she is running late for an appointment.

The patient describes her symptoms: unrelenting sore throat for 2 days and pain with swallowing. She complains of feeling feverish and fatigued, with no appetite and “swollen glands.” She denies cough and runny nose; she looks and sounds exhausted. She denies smoking and excessive alcohol intake. You vaguely hone in on the accent, thinking it might be South African. Her HPI and ROS completed, you record her physical findings of pharyngeal erythema, no exudates, and moderate anterior lymphadenopathy.

You have a nagging thought about her “story.” As an urgent care clinician, you know you are likely her only health care provider and you feel some connection. It is late, and the patient is in a rush, so you promise yourself to delve deeper the next time she presents.

Continue to: You confirm the negative strep test results...

You confirm the negative strep test results and deliver the well-rehearsed sermon. She appears surprised, asking if you are sure. You suggest that she schedule a full physical in the near future. She hops off the table, heels clicking on the tile floor, as you complete your note. You do not suspect she is off to meet her scheduled man of the evening as assigned by her escort service.

Before you clock out, you check the extended patient appointment schedule and do not see her name. You vow to call her the next day and discover that she has no listed phone number. An uncomfortable feeling settles in: Are you missing something?

IN URGENT CARE

NM is an interactive patient approach more often applied to seriously ill or chronic disease patients, for whom it meaningfully supports a patient’s existence as central to the diagnostic testing and treatment of health care concerns. One can professionally debate that NM has no place in urgent care; however, this is where many patients’ acute and chronic conditions are discovered. It is where elevated blood glucose becomes type 2 diabetes and abnormal complete blood counts become blood cancer. With deeper application of NM’s principles, our simple-appearing acute pharyngitis case might have received a different workup.

NM practitioners subscribe to careful listening. Rita Charon, MD, a leading proponent of NM, describes this approach to patient care as a “rigorous intellectual and clinical discipline to fortify health care with its capacity to skillfully receive the accounts persons give of themselves—to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved to action by the stories of others.”3 It is a patient care revival that helps clinicians recognize and shield themselves from the powerful stampede of technology, templated patient interviews, digital documentation, and diminution of clinician and patient bonding.

The clinician in this patient encounter has functionally intact radar, sensing something awry, but communication falls short. NM’s strength is to bond the clinician to the patient, enhancing subtle, and at times pivotal, information exchange. It generates patient trust even in brief encounters, fostering improved clinical decision-making. A stronger NM focus might have encouraged this clinician to investigate more deeply the patient’s fancy clothing and surprised response to the negative strep test results by posing a simple query, such as ”What do you think might be going on?”

Continue to: MEDICAL ERROR

MEDICAL ERROR

Pharyngitis is common, making it prime territory for medical error—even for experienced clinicians—because of 3 human tendencies that NM recognizes and seeks to avoid.4 These human tendencies, insightfully delineated decades ago by experimental psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, authors of Anchoring, Availability and Attribution, appear most commonly under uncertain conditions and time pressures, such as in urgent care. How does this patient encounter reflect these tendencies?5

Anchoring refers to the tendency to grasp the first symptom, physical finding, or laboratory abnormality, and hold onto it tightly.5 Such initial diagnostic impressions/information may prove true; however, other unconsidered diagnoses may include the correct one. In this encounter, the clinician entered the exam room with an early fixed diagnosis and applied the rapid strep results to diagnose viral pharyngitis. Other, conflicting hints were fleetingly noted and not addressed.

Availability refers to the tendency to assume that a quickly recalled experience explains a novel situation.5 Clinicians regularly diagnose viral pharyngitis, leading to familiarity and availability. This is contrary to NM’s view of every patient having a unique and noteworthy story.

Attribution refers to the tendency to invoke stereotypical images and assign symptoms and findings to the stereotype, which is often negative (eg, hypochondriac, drinker).5

In this encounter, the clinician would have benefited from considering other categories of diagnoses that could occur in this patient, expanding the differential diagnosis list, by soliciting a deeper patient story, fostering trust, and following clinical intuition. Had this bond been cultivated over prior visits, even in an urgent care setting, the graduate student ruse would have been discovered and the patient’s true occupation—female sex worker—revealed. The clinician would have modified the laboratory testing, discovering human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8) as the pharyngitis etiology, which is disproportionately linked to HIV co-infection and increases the risk for Kaposi sarcoma (KS) 20,000-fold. The prevalence of HHV-8 is 17% in the United States and is much higher (50%) in South Africa, the origin of the patient’s accent.6 Deeper patient relationships enable uncomfortable history-taking questions, with improved reliability. This missed diagnosis has wide-ranging negative consequences for the patient and her escort encounters.6

Continue to: THE FLEXNER REPORT

THE FLEXNER REPORT: NARRATIVE MEDICINE'S EXCISION

It is clear that the scientific revolution prompted the removal of NM from clinical practice. The 1910 Flexner Report, funded by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Science and authored by research scholar and physician Abraham Flexner, analyzed the functioning of 155 US and Canadian medical schools.7 His report supported the socially desirable goal of reforming medical education by exposing mediocre quality, unsavory profit motives, inadequate facilities, and nonscientific approaches, and publishing a list of those falling below the gold standard (which was the German medical education system). Harvard and Johns Hopkins received a gold seal, many other medical schools closed, and several responded to the challenge and excelled.8

Medical school curricula transitioned to exclusively theoretical and scientific teaching, objectifying values and rewarding research and efficiency. The subjective patient story was surgically excised and replaced with objective science. Not all change is good, however, and years later, Flexner reflected that scientific medicine was “sadly deficient in cultural and philosophic background.”8 His report also dramatically suppressed the use of complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry, another medical boomerang.9 Scientific rigor is desirable—but not to the exclusion of the central patient role and other potential health care modalities.

THE PROBLEM-ORIENTED MEDICAL RECORD AND EHR

Decades after Flexner’s report on medical education curricula, another reformer, Lawrence Weed, MD, trained his eye on medical documentation’s organization and structure. He published a seminal article, “Medical Records that Guide and Teach” in the New England Journal of Medicine.10 Truly a pioneer, he demonstrated how typical medical record case documentation circa 1967 could be more efficient and espoused the problem-oriented medical record. He conceptualized designs for reorganizing medical records, prophetically promoted use of “paramedical” personnel, and encouraged computer integration.10

Coinciding with the birth of the PA profession and the recent inception of the NP profession, Weed endorsed the use of trained interviewers who would apply a “branching” question algorithm with associated computer data entry designed to protect expensive physician time. The patient story would be a jigsaw puzzle, as physicians could fill in missing information.10

Weed’s goals had merit by stressing structure for the disorganized, then-handwritten medical record, benefitting the growth of team-based patient care. However, efficiency and precision continued to marginalize a key component of the patient’s illness narrative in favor of speed, objectivity, and achievable billing essentials.11 His recommendations have eradicated the free-text box, replacing it with a selection of pull-down choices or prewritten templates. With a series of clicks, the subjective patient’s own narrative is sterilized, removing valuable details from the team’s view.11 The “s” of the Subjective Objective Assessment and Plan note is washed away (Table 1).

Continue to: Weed's clinical documentation...

Weed’s clinical documentation efficiency system caught fire. However, similar to Flexner’s later second thoughts, Weed also cast doubt on the full effect of his recommendations. In a 2009 interview conducted by a former medical student of his, Weed revealed views that more closely resemble our current competency-based medical education and stress the value of interpersonal skills in patient care12:

- Computerization of the medical record—with its vast amount of information and physician-processing capacity—“inevitably” leads to dangerous cognitive shortcuts. Medical education seeks to instill “medical knowledge and clinical judgment,” giving students “misplaced faith in the completeness and accuracy of their own intellects and is the antithesis of a truly scientific education.”12

- Medical student recruitment and instruction have long emphasized memory and regurgitation of facts, while students should be selected for their hands-on and interpersonal skills. Medical school should be “teaching a core of behavior instead of a core of knowledge.”12 These are areas in which NM helps.

FLEXNER, WEED, AND NOW, CHARON

Medicine’s history is blemished by errors, some significant. Flexner neatly compartmentalized medical education, Weed digitized the clinician/patient interaction, and Charon revitalizes the reason clinicians chose a health care profession. Charon—as a practicing internist, as well as a professor in the Department of Medicine and Executive Director of the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City—is fully qualified to speak to the importance of NM in medical education and medical practice. Her 2006 book reminds us that sore throats are not always simple, boring, and routine; each one is as unique as the person housing that particular pharynx.13

How does NM drive clinicians to be better, countering cognitive errors while incorporating the patient’s cultural and philosophic background? According to Charon, the NM concept results from conversation among scholars and clinicians teaching and practicing at Columbia University in early 2000, fueled by decades of insight from literature, medical (health care) humanities, ethics, health care communication, and primary care medicine.3 NM supports patient-centric teaching and care, reminding us that it combines the historical doctor-at-bedside, who exhibited careful, empathetic questioning and listening, with the benefits of modern medical science.

Charon describes 3 main clinician-to-patient interactions, allowing us to regain some of what we have lost: attention, representation, and affiliation (Table 2). In addition to medical error reduction, these 3 interactive behaviors counter the aforementioned 3As (anchoring, availability, and attribution) of cognitive error.5Attention initiates the clinician’s heightened and committed listening to the patient.3 In our patient encounter, essential information is undisclosed, leading to a missed diagnosis and an incomplete representation in the written note. The clinician, due to insufficient attention, missed important clues such as the patient’s dress, accent, and profession, which limited the representation. This almost seems nonsensical; who would care about a patient’s dress or accent and, of practical concern today, where would one record it? And could another urgent care clinician or specialist find these notes? How might a more serious future medical outcome be averted? Affiliation results in a connection of careful listening and full documentation as the clinician becomes invested in the whole patient, not just the sore throat.3

PREPROFESSIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

Preprofessional humanities education may result in stronger NM conceptualization. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recognizes the value of arts and humanities in medical education in developing qualities of professionalism, communication skills, and emotional intelligence in physicians. The AAMC Curriculum Inventory and Reports (2015-2016) shows that 119 medical schools require humanities education, including

- Visual arts to improve observational skills

- History education to frame modern-day Ebola outbreaks (eg, using the framework of the Black Death),

- Literature and poetry to enhance insight into different ways of living and thinking, fostering critical thinking.14

Continue to: NM has been offered in...

NM has been offered in medical schools with positive outcomes. Published results of a 2010 qualitative study of 130 Columbia University medical students who completed a required intensive half-semester of NM seminars testify to its salience.15 Students articulated NM’s importance to critical thinking and reflection, through improved attention and affiliation with their patients, improved ability to examine assumptions and develop new skills, and improved clarity of communication.15

A small number of PA programs, far fewer than medical schools, are incorporating NM coursework, through application of literature, visual media, creative writing, and other approaches based on the humanities.16 The nursing profession, which prefers the term narrative health care to narrative medicine, endorses its inclusion in nursing education. A 2018 article in Nursing Education Perspectives supports the study of humanities to complement technical competencies such as the ability to “absorb, analyze, and interpret complex artifacts” and to “participate effectively in deliberative conversations.”17

THE PRACTICING CLINICIAN: MENTAL HEALTH AND NARRATIVE MEDICINE

The value of NM extends beyond the patient to embrace caregivers as well; this is important, in light of increased attention to mental health status among clinicians. Although the term used most frequently is physician burnout, data indicate that patient management by MDs, NPs, and PAs is becoming indistinguishable—and thus risk for associated negative mental health consequences may be shared

The National Academy of Medicine is also addressing the issues of clinician well-being (see https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/). Former US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, has spoken about the epidemic of loneliness that affects clinicians. This can result from playing the physician role, lack of family support, and increased dependency on technology—yet, on a basic level, lack of interpersonal communication and connection are at the core.21 Communication between clinicians can lead to greater social cohesion and compassion, and effective uninterrupted listening and expression of their feelings helps. This begs the question: If physicians need to communicate better and practice active listening among themselves, how does this translate to the physician-to-patient bond?

THE CLINICIANS' PERSONAL BALM

Caruso Brown and Garden describe how the illness experiences of physicians, through their own reflective writing, create an empathy bridge between the professional healer and a sick patient, allowing them to be better and healthier clinicians.22 Recent best-selling physician narratives such as those by Atul Gawande,23 Siddhartha Mukherjee,24 and Paul Kalanithi25 support the similarities between the sick physician and the sick patient. Illness narratives written by physicians-turned-patients are not dissimilar to illness narratives written by patients. Reflective writing by clinicians fosters a deeper understanding not only of how patients feel, but also of the relationship they desire and deserve.22

Continue to: Writing a novel...

Writing a novel is beyond the time and ability of many clinicians. However, they can closely read literature (another NM tool), discuss books and other types of writing, participate in a book club, establish a hospital or office support group, and find a buddy or trustworthy confidant with whom to decompress and vent.3 Active journal clubs can alternate clinical guidelines with literature to expand their perspectives. An international voice, Maria Giulia Marini, Research and Health Director of the Fondazione ISTUD in Milan, Italy, and European proponent of NM, offers similar suggestions, indicating that making nonmedical works parts of a clinician’s life encourages empathy and promotes understanding between clinician and patient, as well as a holistic management approach, encourages personal and collegial reflection (eg, sharing tough experiences), sets a patient-centered agenda, and challenges the norm.26

NARRATIVE MEDICINE'S FUTURE ROLE

The field of medical humanities has experienced growth through publications, national and international conferences, and formal discussion between executives of the AAMC and the National Endowment for the Humanities to design and incorporate joint programs teaching humanities in medical schools.27 As of March 2019, there were 85 established baccalaureate health humanities programs in the US, with additional programs in development.28

Clinicians and professional organizations cannot help but see the suffering of patients, with its concomitant provider burden. The urgent care patient encounter in our example met the standard of care of the typical interaction that achieves billing protocols; the HPI, ROS, and physical exam would not raise an eyebrow. Yet, an NM approach provides more. Asking the atypical questions about accents, out-of-the-ordinary dress and behavior, and wondering about the mentioned late-night appointment attends to NM’s focused active listening, with resultant quality documentation and a whole patient encounter, even in an acute care case.

Don’t be afraid. Consider that as in novels and movies, strange things happen. The iconic book The House of God reminds clinicians that, upon hearing hoof beats, we should first think of horses—however, sometimes a zebra is correct.29 When an urgent care clinician interprets the hoof beats, a zebra may be in the differential diagnosis; in the case presented, the patient might fortunately be spared a future KS diagnosis. And the clinician may avoid personal anguish at what could have been a better outcome. NM can help clinicians remember that sore throats are as unique as people.

1. Krisberg K. Narrative medicine: Every patient has a story. AAMC News. March 28, 2018. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/narrative-medicine-every-patient-has-story. Accessed October 10, 2018.

2. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;80(12):877-882.

3. Charon R, DasGupta S, Hermann N, et al. The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017:1, 3.

4. Murphy JG , Stee LA, McAvoy MT, Oshiro J. Journal reporting of medical errors: the wisdom of Solomon, the bravery of Achilles, and the foolishness of Pan. Chest. 2007;131(3):890-896.

5. Groopman J, Hartzband P. Mindful medicine: Critical thinking leads to right diagnosis. ACP Internist. January 2008. https://acpinternist.org/archives/2008/01/groopman.htm. Accessed May 11, 2018.

6. Nzivo MM, Lwembe RM, Odari EO, Budambula NLM. Human herpes virus type 8 among female-sex workers. J Hum Virol Retrovirol 2017;5(6):00176.

7. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada—a report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin No. 4. Boston, MA: DB Updike, Merrymount Press; 1910.

8. Cooke M, Irby DM, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner Report. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1339-1344.

9. Stahnisch FW, Verhoef M. The Flexner Report of 1910 and its impact on complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry in North America in the 20th Century. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:647896.

10. Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. NEJM. 1968;278(12):652-657.

11. Ommaya AK, Cipriano PF, Hoyt DB, et al. Care-centered clinical documentation in the digital environment: solutions to alleviate burnout. NAM.edu/Perspectives. January 29, 2018. Accessed June 19, 2018.

12. Jacobs L. Interview with Lawrence Weed, MD - The father of the problem-oriented medical record looks ahead. The Permanente Journal. Summer 2009;13(3):84-89. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/09-068. Accessed August 2, 2019.

13. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

14. Mann S. Focusing on arts, humanities to develop well-rounded physicians. AAMC News. August 15, 2017. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/focusing-arts-humanities-well-rounded-physicians/. Accessed Oct 10, 2018.

15. Miller E, Balmer D, Hermann N, et al. Sounding narrative medicine: studying students’ professional identity development at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):335-342.

16. Grant JP, Gregory T. The Sacred Seven elective: integrating the health humanities into physician assistant education. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28(4):220-222.

17. Lim F, Marsaglia MJ. Nursing humanities: teaching for a sense of salience. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2018;39(2):121-122.

18. Hooker RS. PAs, NPs, PAs, physicians and regression to the mean. JAAPA. 2018;31(7):13-14.

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;338:2272-2281.

20. Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, et al. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “Being connected … a key to my survival.” JAMA. 2009;301(11):1155–1164, E1.

21. Firth S. Former Surgeon General talks love, loneliness, and burnout: NAM panel addresses growing crisis in medicine. Medpage Today. May 4, 2018. www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/generalprofessionalissues/72720. Accessed June 15, 2018.

22. Caruso Brown AE, Garden R. Images of healing and learning: from silence into language: Questioning the power of physician illness narratives. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(5):501-507.

23. Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. 1st ed. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2014.

24. Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2010.

25. Kalanithi P. When Breath Becomes Air. New York, NY: Penguin Random House; 2016.

26. Marini MG. Narrative Medicine: Bridging the Gap Between Evidence-Based Care and Medical Humanities. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

27. Charon R. To see the suffering. Acad Med. 2017;92(12):1668-1670.

28. Lamb EG, Berry SL, Jones T. Health Humanities Baccalaureate Programs in the United States. Hiram, OH: Center for Literature and Medicine, Hiram College; March 2019.

29. Shem S. The House of God. New York, NY: Berkley Random House; 1978.

1. Krisberg K. Narrative medicine: Every patient has a story. AAMC News. March 28, 2018. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/narrative-medicine-every-patient-has-story. Accessed October 10, 2018.

2. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;80(12):877-882.

3. Charon R, DasGupta S, Hermann N, et al. The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017:1, 3.

4. Murphy JG , Stee LA, McAvoy MT, Oshiro J. Journal reporting of medical errors: the wisdom of Solomon, the bravery of Achilles, and the foolishness of Pan. Chest. 2007;131(3):890-896.

5. Groopman J, Hartzband P. Mindful medicine: Critical thinking leads to right diagnosis. ACP Internist. January 2008. https://acpinternist.org/archives/2008/01/groopman.htm. Accessed May 11, 2018.

6. Nzivo MM, Lwembe RM, Odari EO, Budambula NLM. Human herpes virus type 8 among female-sex workers. J Hum Virol Retrovirol 2017;5(6):00176.

7. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada—a report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin No. 4. Boston, MA: DB Updike, Merrymount Press; 1910.

8. Cooke M, Irby DM, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner Report. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1339-1344.

9. Stahnisch FW, Verhoef M. The Flexner Report of 1910 and its impact on complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry in North America in the 20th Century. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:647896.

10. Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. NEJM. 1968;278(12):652-657.

11. Ommaya AK, Cipriano PF, Hoyt DB, et al. Care-centered clinical documentation in the digital environment: solutions to alleviate burnout. NAM.edu/Perspectives. January 29, 2018. Accessed June 19, 2018.

12. Jacobs L. Interview with Lawrence Weed, MD - The father of the problem-oriented medical record looks ahead. The Permanente Journal. Summer 2009;13(3):84-89. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/09-068. Accessed August 2, 2019.

13. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

14. Mann S. Focusing on arts, humanities to develop well-rounded physicians. AAMC News. August 15, 2017. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/focusing-arts-humanities-well-rounded-physicians/. Accessed Oct 10, 2018.

15. Miller E, Balmer D, Hermann N, et al. Sounding narrative medicine: studying students’ professional identity development at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):335-342.

16. Grant JP, Gregory T. The Sacred Seven elective: integrating the health humanities into physician assistant education. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28(4):220-222.

17. Lim F, Marsaglia MJ. Nursing humanities: teaching for a sense of salience. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2018;39(2):121-122.

18. Hooker RS. PAs, NPs, PAs, physicians and regression to the mean. JAAPA. 2018;31(7):13-14.

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;338:2272-2281.

20. Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, et al. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “Being connected … a key to my survival.” JAMA. 2009;301(11):1155–1164, E1.

21. Firth S. Former Surgeon General talks love, loneliness, and burnout: NAM panel addresses growing crisis in medicine. Medpage Today. May 4, 2018. www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/generalprofessionalissues/72720. Accessed June 15, 2018.

22. Caruso Brown AE, Garden R. Images of healing and learning: from silence into language: Questioning the power of physician illness narratives. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(5):501-507.

23. Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. 1st ed. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2014.

24. Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2010.

25. Kalanithi P. When Breath Becomes Air. New York, NY: Penguin Random House; 2016.

26. Marini MG. Narrative Medicine: Bridging the Gap Between Evidence-Based Care and Medical Humanities. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

27. Charon R. To see the suffering. Acad Med. 2017;92(12):1668-1670.

28. Lamb EG, Berry SL, Jones T. Health Humanities Baccalaureate Programs in the United States. Hiram, OH: Center for Literature and Medicine, Hiram College; March 2019.

29. Shem S. The House of God. New York, NY: Berkley Random House; 1978.