User login

Estimates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among veterans range between 34% and 47% higher than in the general population.1 As patients progress to end-stage kidney disease and begin chronic dialysis, they often experience further functional and cognitive decline and a high symptom burden, leading to poor quality of life.2 Clinicians should initiate goals of care conversations (GOCCs) to support high-risk patients on dialysis to ensure that the interventions they receive align with their goals and preferences, since many patients on dialysis prefer measures focused on pain relief and discomfort.3,4 While proactive GOCCs are supported among nephrology associations, few such conversations take place.5,6 In one study, more than half of patients on dialysis stated they had not discussed end-of-life preferences in the past 12 months.4 As a result, patients may not consider the larger implications of receiving dialysis indefinitely as a life-sustaining treatment (LST).

In May 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for Ethics in Health Care rolled out the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative to proactively engage patients with serious illnesses, such as those with end-stage kidney disease, in GOCCs to clarify their preferences for LSTs.7 After comprehensive training, a preliminary audit at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois, revealed that only 27% of patients on dialysis had LST preferences documented in a standardized LST note.

Nephrologists cite multiple barriers to proactively addressing goals of care with patients with advanced CKD, including clinician discomfort, perceived lack of time, infrastructure, and training.8,9 Similarly, the absence of a multidisciplinary advance care planning approach—specifically bringing together palliative care (PC) clinicians with nephrologists—has been highlighted but not as well studied.10,11

In this quality improvement (QI) project, we aimed to establish a workflow to enhance collaboration between nephrology and PC and to increase the percentage of VA patients on outpatient hemodialysis who engaged in GOCCs, as documented by completion of an LST progress note in the VA’s electronic health record (EHR). We developed a collaboration among PC, nephrology, and social work to improve the rates of documented GOCCs and LST patients on dialysis.

Implementation

EHJVAH is a 1A facility with > 80 patients who receive outpatient hemodialysis on campus. At the time of this collaboration in the fall of 2019, the collaborative dialysis team comprised 2 social workers and a nephrologist. The PC team included a coordinator, 2 nurse practitioners, and 3 physicians. A QI nurse was involved in the initial data gathering for this project.

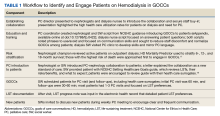

The PC and nephrology medical directors developed a workflow process that reflected organizational and clinical steps in planning, initiating, and completing GOCCs with patients on outpatient dialysis (Table 1). The proposed process engaged an interdisciplinary PC and nephrology group and was revised to incorporate staff suggestions.

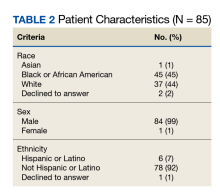

A prospective review of 85 EHJVAH hemodialysis unit patient records was conducted between September 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020 (Table 2). We reviewed LST completion rates for all patients receiving dialysis within this timeframe. During the intervention period, the PC team approached 40 patients without LST notes to engage in GOCCs.

Discussion

Over the 13-month collaboration, LST note completion rates increased from 27% to 81%, with 69 of 85 patients having a documented LST progress note in the EHR. PC approached nearly half of all patients on dialysis. Most patients agreed to be seen by the PC team, with 72% of those approached agreeing to a PC consultation. Previous research has suggested that having a trusted dialysis staff member included in GOCCs contributes to high acceptance rates.12

PC is a relatively uncommon partnership for nephrologists, and PC and hospice services are underutilized in patients on dialysis both nationally and within the VA.13-15 Our outcomes could be replicated, as PC is required at all VA sites.

Conclusions

The innovation of an interdisciplinary nephrology–PC collaboration was an important step in increasing high-quality GOCCs and eliciting patient preferences for LSTs among patients on dialysis. PC integration for patients on dialysis is associated with improved symptom management, fewer aggressive health care measures, and a higher likelihood of dying in one’s preferred setting.16 While this partnership focused on patients already receiving dialysis, successful PC interventions are felt most keenly upstream, before dialysis initiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their colleague, Mary McCabe, DNP, Quality Systems Improvement, Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital. The authors also acknowledge the clinical dedication of the dialysis social workers, Sarah Adam, LCSW, and Sarah Kraner, LCSW, without which this collaboration would not have been possible.

1. Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

2. Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1345-1352. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg105

3. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1206-1214. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036

4. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960809

5. Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force. Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1664-1672. doi:10.2215/CJN.04970512

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2nd ed. Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Goals of care conversations training for nurses, social workers, psychologists, and chaplains. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/team.asp

8. Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, et al. Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: an implementation study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):64. Published 2019 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0437-2

9. O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):855-866. doi:10.2215/CJN.11351015

10. Koncicki HM, Schell JO. Communication skills and decision making for elderly patients with advanced kidney disease: a guide for nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):688-695. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.032

11. Holley JL, Davison SN. Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: a need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):344-346. doi:10.2215/CJN.00290115

12. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1023-1028. doi:10.2215/CJN.01050306

13. Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1248-1255. doi:10.2215/CJN.00970306

14. Williams ME, Sandeep J, Catic A. Aging and ESRD demographics: consequences for the practice of dialysis. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):617-622. doi:10.1111/sdi.12029

15. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. FY 2020 annual report. Palliative and hospice care.

16. Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608-1614. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq630

17. Fadem SZ, Fadem J. HD mortality predictor. Accessed August 31, 2023. http://touchcalc.com/calculators/sq

18. National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Setting health care goals: a guide for people with hearth problems. Updated June 2016. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/GoCC/lst_booklet_for_patients_setting_health_care_goals_final.pdf

Estimates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among veterans range between 34% and 47% higher than in the general population.1 As patients progress to end-stage kidney disease and begin chronic dialysis, they often experience further functional and cognitive decline and a high symptom burden, leading to poor quality of life.2 Clinicians should initiate goals of care conversations (GOCCs) to support high-risk patients on dialysis to ensure that the interventions they receive align with their goals and preferences, since many patients on dialysis prefer measures focused on pain relief and discomfort.3,4 While proactive GOCCs are supported among nephrology associations, few such conversations take place.5,6 In one study, more than half of patients on dialysis stated they had not discussed end-of-life preferences in the past 12 months.4 As a result, patients may not consider the larger implications of receiving dialysis indefinitely as a life-sustaining treatment (LST).

In May 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for Ethics in Health Care rolled out the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative to proactively engage patients with serious illnesses, such as those with end-stage kidney disease, in GOCCs to clarify their preferences for LSTs.7 After comprehensive training, a preliminary audit at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois, revealed that only 27% of patients on dialysis had LST preferences documented in a standardized LST note.

Nephrologists cite multiple barriers to proactively addressing goals of care with patients with advanced CKD, including clinician discomfort, perceived lack of time, infrastructure, and training.8,9 Similarly, the absence of a multidisciplinary advance care planning approach—specifically bringing together palliative care (PC) clinicians with nephrologists—has been highlighted but not as well studied.10,11

In this quality improvement (QI) project, we aimed to establish a workflow to enhance collaboration between nephrology and PC and to increase the percentage of VA patients on outpatient hemodialysis who engaged in GOCCs, as documented by completion of an LST progress note in the VA’s electronic health record (EHR). We developed a collaboration among PC, nephrology, and social work to improve the rates of documented GOCCs and LST patients on dialysis.

Implementation

EHJVAH is a 1A facility with > 80 patients who receive outpatient hemodialysis on campus. At the time of this collaboration in the fall of 2019, the collaborative dialysis team comprised 2 social workers and a nephrologist. The PC team included a coordinator, 2 nurse practitioners, and 3 physicians. A QI nurse was involved in the initial data gathering for this project.

The PC and nephrology medical directors developed a workflow process that reflected organizational and clinical steps in planning, initiating, and completing GOCCs with patients on outpatient dialysis (Table 1). The proposed process engaged an interdisciplinary PC and nephrology group and was revised to incorporate staff suggestions.

A prospective review of 85 EHJVAH hemodialysis unit patient records was conducted between September 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020 (Table 2). We reviewed LST completion rates for all patients receiving dialysis within this timeframe. During the intervention period, the PC team approached 40 patients without LST notes to engage in GOCCs.

Discussion

Over the 13-month collaboration, LST note completion rates increased from 27% to 81%, with 69 of 85 patients having a documented LST progress note in the EHR. PC approached nearly half of all patients on dialysis. Most patients agreed to be seen by the PC team, with 72% of those approached agreeing to a PC consultation. Previous research has suggested that having a trusted dialysis staff member included in GOCCs contributes to high acceptance rates.12

PC is a relatively uncommon partnership for nephrologists, and PC and hospice services are underutilized in patients on dialysis both nationally and within the VA.13-15 Our outcomes could be replicated, as PC is required at all VA sites.

Conclusions

The innovation of an interdisciplinary nephrology–PC collaboration was an important step in increasing high-quality GOCCs and eliciting patient preferences for LSTs among patients on dialysis. PC integration for patients on dialysis is associated with improved symptom management, fewer aggressive health care measures, and a higher likelihood of dying in one’s preferred setting.16 While this partnership focused on patients already receiving dialysis, successful PC interventions are felt most keenly upstream, before dialysis initiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their colleague, Mary McCabe, DNP, Quality Systems Improvement, Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital. The authors also acknowledge the clinical dedication of the dialysis social workers, Sarah Adam, LCSW, and Sarah Kraner, LCSW, without which this collaboration would not have been possible.

Estimates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among veterans range between 34% and 47% higher than in the general population.1 As patients progress to end-stage kidney disease and begin chronic dialysis, they often experience further functional and cognitive decline and a high symptom burden, leading to poor quality of life.2 Clinicians should initiate goals of care conversations (GOCCs) to support high-risk patients on dialysis to ensure that the interventions they receive align with their goals and preferences, since many patients on dialysis prefer measures focused on pain relief and discomfort.3,4 While proactive GOCCs are supported among nephrology associations, few such conversations take place.5,6 In one study, more than half of patients on dialysis stated they had not discussed end-of-life preferences in the past 12 months.4 As a result, patients may not consider the larger implications of receiving dialysis indefinitely as a life-sustaining treatment (LST).

In May 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for Ethics in Health Care rolled out the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative to proactively engage patients with serious illnesses, such as those with end-stage kidney disease, in GOCCs to clarify their preferences for LSTs.7 After comprehensive training, a preliminary audit at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois, revealed that only 27% of patients on dialysis had LST preferences documented in a standardized LST note.

Nephrologists cite multiple barriers to proactively addressing goals of care with patients with advanced CKD, including clinician discomfort, perceived lack of time, infrastructure, and training.8,9 Similarly, the absence of a multidisciplinary advance care planning approach—specifically bringing together palliative care (PC) clinicians with nephrologists—has been highlighted but not as well studied.10,11

In this quality improvement (QI) project, we aimed to establish a workflow to enhance collaboration between nephrology and PC and to increase the percentage of VA patients on outpatient hemodialysis who engaged in GOCCs, as documented by completion of an LST progress note in the VA’s electronic health record (EHR). We developed a collaboration among PC, nephrology, and social work to improve the rates of documented GOCCs and LST patients on dialysis.

Implementation

EHJVAH is a 1A facility with > 80 patients who receive outpatient hemodialysis on campus. At the time of this collaboration in the fall of 2019, the collaborative dialysis team comprised 2 social workers and a nephrologist. The PC team included a coordinator, 2 nurse practitioners, and 3 physicians. A QI nurse was involved in the initial data gathering for this project.

The PC and nephrology medical directors developed a workflow process that reflected organizational and clinical steps in planning, initiating, and completing GOCCs with patients on outpatient dialysis (Table 1). The proposed process engaged an interdisciplinary PC and nephrology group and was revised to incorporate staff suggestions.

A prospective review of 85 EHJVAH hemodialysis unit patient records was conducted between September 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020 (Table 2). We reviewed LST completion rates for all patients receiving dialysis within this timeframe. During the intervention period, the PC team approached 40 patients without LST notes to engage in GOCCs.

Discussion

Over the 13-month collaboration, LST note completion rates increased from 27% to 81%, with 69 of 85 patients having a documented LST progress note in the EHR. PC approached nearly half of all patients on dialysis. Most patients agreed to be seen by the PC team, with 72% of those approached agreeing to a PC consultation. Previous research has suggested that having a trusted dialysis staff member included in GOCCs contributes to high acceptance rates.12

PC is a relatively uncommon partnership for nephrologists, and PC and hospice services are underutilized in patients on dialysis both nationally and within the VA.13-15 Our outcomes could be replicated, as PC is required at all VA sites.

Conclusions

The innovation of an interdisciplinary nephrology–PC collaboration was an important step in increasing high-quality GOCCs and eliciting patient preferences for LSTs among patients on dialysis. PC integration for patients on dialysis is associated with improved symptom management, fewer aggressive health care measures, and a higher likelihood of dying in one’s preferred setting.16 While this partnership focused on patients already receiving dialysis, successful PC interventions are felt most keenly upstream, before dialysis initiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their colleague, Mary McCabe, DNP, Quality Systems Improvement, Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital. The authors also acknowledge the clinical dedication of the dialysis social workers, Sarah Adam, LCSW, and Sarah Kraner, LCSW, without which this collaboration would not have been possible.

1. Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

2. Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1345-1352. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg105

3. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1206-1214. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036

4. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960809

5. Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force. Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1664-1672. doi:10.2215/CJN.04970512

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2nd ed. Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Goals of care conversations training for nurses, social workers, psychologists, and chaplains. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/team.asp

8. Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, et al. Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: an implementation study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):64. Published 2019 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0437-2

9. O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):855-866. doi:10.2215/CJN.11351015

10. Koncicki HM, Schell JO. Communication skills and decision making for elderly patients with advanced kidney disease: a guide for nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):688-695. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.032

11. Holley JL, Davison SN. Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: a need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):344-346. doi:10.2215/CJN.00290115

12. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1023-1028. doi:10.2215/CJN.01050306

13. Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1248-1255. doi:10.2215/CJN.00970306

14. Williams ME, Sandeep J, Catic A. Aging and ESRD demographics: consequences for the practice of dialysis. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):617-622. doi:10.1111/sdi.12029

15. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. FY 2020 annual report. Palliative and hospice care.

16. Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608-1614. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq630

17. Fadem SZ, Fadem J. HD mortality predictor. Accessed August 31, 2023. http://touchcalc.com/calculators/sq

18. National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Setting health care goals: a guide for people with hearth problems. Updated June 2016. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/GoCC/lst_booklet_for_patients_setting_health_care_goals_final.pdf

1. Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

2. Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1345-1352. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg105

3. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1206-1214. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036

4. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960809

5. Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force. Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1664-1672. doi:10.2215/CJN.04970512

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2nd ed. Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Goals of care conversations training for nurses, social workers, psychologists, and chaplains. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/team.asp

8. Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, et al. Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: an implementation study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):64. Published 2019 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0437-2

9. O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):855-866. doi:10.2215/CJN.11351015

10. Koncicki HM, Schell JO. Communication skills and decision making for elderly patients with advanced kidney disease: a guide for nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):688-695. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.032

11. Holley JL, Davison SN. Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: a need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):344-346. doi:10.2215/CJN.00290115

12. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1023-1028. doi:10.2215/CJN.01050306

13. Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1248-1255. doi:10.2215/CJN.00970306

14. Williams ME, Sandeep J, Catic A. Aging and ESRD demographics: consequences for the practice of dialysis. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):617-622. doi:10.1111/sdi.12029

15. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. FY 2020 annual report. Palliative and hospice care.

16. Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608-1614. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq630

17. Fadem SZ, Fadem J. HD mortality predictor. Accessed August 31, 2023. http://touchcalc.com/calculators/sq

18. National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Setting health care goals: a guide for people with hearth problems. Updated June 2016. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/GoCC/lst_booklet_for_patients_setting_health_care_goals_final.pdf