User login

Whole Health Oncology—Just Do It: Making Whole Person Cancer Care Routine and Regular at the Dayton VA Medical Center (DVAMC)

Background

VA Whole Health (WH) is an approach that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being. In 2020, 18 WH Flagship sites demonstrated reduced opiate use and smaller increases in pharmacy costs as well as favorable veteran self-reported measures. VA mandated WH integration into mental health and primary care. Purose: To incorporate WH within Dayton VA cancer care, using the Personal Health Inventory (PHI) as an intake tool, a tumor-agnostic WH oncology clinic was established.

Methods

Led by an oncologist, a referral-based clinic opened in 2021. Pre-work included EHR items (stop codes/templates), staff training and leverage of mental health integration. VA’s generic PHI was utilized until an oncology-specific PHI was developed by leaders in the field.(3-5) Clinic data was tracked.

Results

170 visits offered (June 2021-May 2024). 32 referrals received (one without cancer; deaths: two pre-intake/five post-intake); 70 appointments occurred among 30 veterans (30 intake/40 follow-up) for 41% fill rate (up 5% from 1st six months). 96% PHI completion rate. Referral sources: fellows (43%), attendings (17%), PCP (3%), Survivorship Clinic (3%), self-referral (33%)--40% of these from cancer support group members. Cancer types (one dual-diagnosis; total >100%): 24% breast, 17% prostate, 17% NSCLC, 10% NHL, 10% pancreatic, 7% Head/Neck, 7% SCLC, 3% each colon/esophageal/kidney. Cancer Stages represented: I (10%), II (20%), III (23%) and IV (47%). Participant info: Age range (36-85); 69% male and 31% female with 86% on active cancer therapy (hormonal, immune-, chemo- or chemoradiation). Supplements were discussed at 26% of visits and referrals ordered at 27% (4-massage therapy, 1-acupuncture, 1-chiropractic, 2-health coaching, 1-cardiology, 1-lymphedema therapy, 1-social work, 1-survivorship clinic, 1-yoga, 1-diabetes education, 1-ENT, 1-nutrition, 1-pathology, 1-pulmonary, 1-prosthetics).

Conclusions

WH within cancer care is feasible for veterans on active treatment (all types/stages) and at a non-Flagship/unfunded site. Veterans gain introduction to WH through the PHI and Complementary-Integrative Health referrals (VA Directive 1137). Cancer support group attendance prompts WH clinic self-referrals. Next steps at DVAMC are to offer mind-body approaches such as virtual reality experiences in the infusion room and VA CALM sessions via asynchronous online delivery; funding would support WH evolution in oncology.

Background

VA Whole Health (WH) is an approach that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being. In 2020, 18 WH Flagship sites demonstrated reduced opiate use and smaller increases in pharmacy costs as well as favorable veteran self-reported measures. VA mandated WH integration into mental health and primary care. Purose: To incorporate WH within Dayton VA cancer care, using the Personal Health Inventory (PHI) as an intake tool, a tumor-agnostic WH oncology clinic was established.

Methods

Led by an oncologist, a referral-based clinic opened in 2021. Pre-work included EHR items (stop codes/templates), staff training and leverage of mental health integration. VA’s generic PHI was utilized until an oncology-specific PHI was developed by leaders in the field.(3-5) Clinic data was tracked.

Results

170 visits offered (June 2021-May 2024). 32 referrals received (one without cancer; deaths: two pre-intake/five post-intake); 70 appointments occurred among 30 veterans (30 intake/40 follow-up) for 41% fill rate (up 5% from 1st six months). 96% PHI completion rate. Referral sources: fellows (43%), attendings (17%), PCP (3%), Survivorship Clinic (3%), self-referral (33%)--40% of these from cancer support group members. Cancer types (one dual-diagnosis; total >100%): 24% breast, 17% prostate, 17% NSCLC, 10% NHL, 10% pancreatic, 7% Head/Neck, 7% SCLC, 3% each colon/esophageal/kidney. Cancer Stages represented: I (10%), II (20%), III (23%) and IV (47%). Participant info: Age range (36-85); 69% male and 31% female with 86% on active cancer therapy (hormonal, immune-, chemo- or chemoradiation). Supplements were discussed at 26% of visits and referrals ordered at 27% (4-massage therapy, 1-acupuncture, 1-chiropractic, 2-health coaching, 1-cardiology, 1-lymphedema therapy, 1-social work, 1-survivorship clinic, 1-yoga, 1-diabetes education, 1-ENT, 1-nutrition, 1-pathology, 1-pulmonary, 1-prosthetics).

Conclusions

WH within cancer care is feasible for veterans on active treatment (all types/stages) and at a non-Flagship/unfunded site. Veterans gain introduction to WH through the PHI and Complementary-Integrative Health referrals (VA Directive 1137). Cancer support group attendance prompts WH clinic self-referrals. Next steps at DVAMC are to offer mind-body approaches such as virtual reality experiences in the infusion room and VA CALM sessions via asynchronous online delivery; funding would support WH evolution in oncology.

Background

VA Whole Health (WH) is an approach that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being. In 2020, 18 WH Flagship sites demonstrated reduced opiate use and smaller increases in pharmacy costs as well as favorable veteran self-reported measures. VA mandated WH integration into mental health and primary care. Purose: To incorporate WH within Dayton VA cancer care, using the Personal Health Inventory (PHI) as an intake tool, a tumor-agnostic WH oncology clinic was established.

Methods

Led by an oncologist, a referral-based clinic opened in 2021. Pre-work included EHR items (stop codes/templates), staff training and leverage of mental health integration. VA’s generic PHI was utilized until an oncology-specific PHI was developed by leaders in the field.(3-5) Clinic data was tracked.

Results

170 visits offered (June 2021-May 2024). 32 referrals received (one without cancer; deaths: two pre-intake/five post-intake); 70 appointments occurred among 30 veterans (30 intake/40 follow-up) for 41% fill rate (up 5% from 1st six months). 96% PHI completion rate. Referral sources: fellows (43%), attendings (17%), PCP (3%), Survivorship Clinic (3%), self-referral (33%)--40% of these from cancer support group members. Cancer types (one dual-diagnosis; total >100%): 24% breast, 17% prostate, 17% NSCLC, 10% NHL, 10% pancreatic, 7% Head/Neck, 7% SCLC, 3% each colon/esophageal/kidney. Cancer Stages represented: I (10%), II (20%), III (23%) and IV (47%). Participant info: Age range (36-85); 69% male and 31% female with 86% on active cancer therapy (hormonal, immune-, chemo- or chemoradiation). Supplements were discussed at 26% of visits and referrals ordered at 27% (4-massage therapy, 1-acupuncture, 1-chiropractic, 2-health coaching, 1-cardiology, 1-lymphedema therapy, 1-social work, 1-survivorship clinic, 1-yoga, 1-diabetes education, 1-ENT, 1-nutrition, 1-pathology, 1-pulmonary, 1-prosthetics).

Conclusions

WH within cancer care is feasible for veterans on active treatment (all types/stages) and at a non-Flagship/unfunded site. Veterans gain introduction to WH through the PHI and Complementary-Integrative Health referrals (VA Directive 1137). Cancer support group attendance prompts WH clinic self-referrals. Next steps at DVAMC are to offer mind-body approaches such as virtual reality experiences in the infusion room and VA CALM sessions via asynchronous online delivery; funding would support WH evolution in oncology.

Nephrology–Palliative Care Collaboration to Promote Outpatient Hemodialysis Goals of Care Conversations

Estimates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among veterans range between 34% and 47% higher than in the general population.1 As patients progress to end-stage kidney disease and begin chronic dialysis, they often experience further functional and cognitive decline and a high symptom burden, leading to poor quality of life.2 Clinicians should initiate goals of care conversations (GOCCs) to support high-risk patients on dialysis to ensure that the interventions they receive align with their goals and preferences, since many patients on dialysis prefer measures focused on pain relief and discomfort.3,4 While proactive GOCCs are supported among nephrology associations, few such conversations take place.5,6 In one study, more than half of patients on dialysis stated they had not discussed end-of-life preferences in the past 12 months.4 As a result, patients may not consider the larger implications of receiving dialysis indefinitely as a life-sustaining treatment (LST).

In May 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for Ethics in Health Care rolled out the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative to proactively engage patients with serious illnesses, such as those with end-stage kidney disease, in GOCCs to clarify their preferences for LSTs.7 After comprehensive training, a preliminary audit at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois, revealed that only 27% of patients on dialysis had LST preferences documented in a standardized LST note.

Nephrologists cite multiple barriers to proactively addressing goals of care with patients with advanced CKD, including clinician discomfort, perceived lack of time, infrastructure, and training.8,9 Similarly, the absence of a multidisciplinary advance care planning approach—specifically bringing together palliative care (PC) clinicians with nephrologists—has been highlighted but not as well studied.10,11

In this quality improvement (QI) project, we aimed to establish a workflow to enhance collaboration between nephrology and PC and to increase the percentage of VA patients on outpatient hemodialysis who engaged in GOCCs, as documented by completion of an LST progress note in the VA’s electronic health record (EHR). We developed a collaboration among PC, nephrology, and social work to improve the rates of documented GOCCs and LST patients on dialysis.

Implementation

EHJVAH is a 1A facility with > 80 patients who receive outpatient hemodialysis on campus. At the time of this collaboration in the fall of 2019, the collaborative dialysis team comprised 2 social workers and a nephrologist. The PC team included a coordinator, 2 nurse practitioners, and 3 physicians. A QI nurse was involved in the initial data gathering for this project.

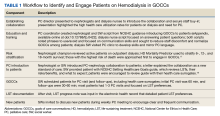

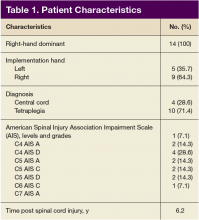

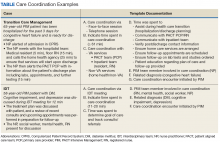

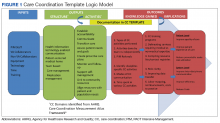

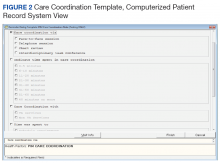

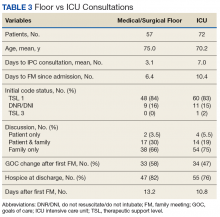

The PC and nephrology medical directors developed a workflow process that reflected organizational and clinical steps in planning, initiating, and completing GOCCs with patients on outpatient dialysis (Table 1). The proposed process engaged an interdisciplinary PC and nephrology group and was revised to incorporate staff suggestions.

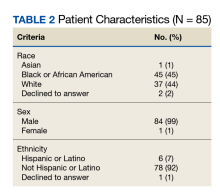

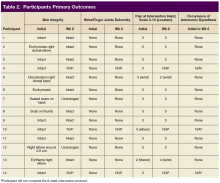

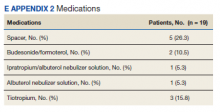

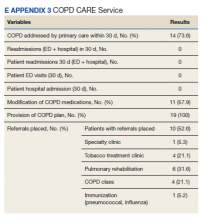

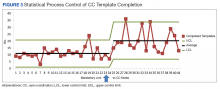

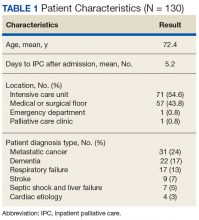

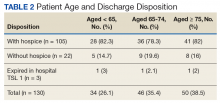

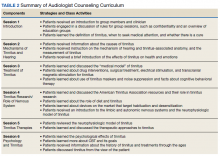

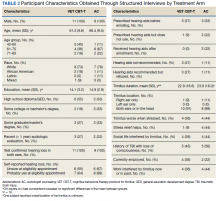

A prospective review of 85 EHJVAH hemodialysis unit patient records was conducted between September 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020 (Table 2). We reviewed LST completion rates for all patients receiving dialysis within this timeframe. During the intervention period, the PC team approached 40 patients without LST notes to engage in GOCCs.

Discussion

Over the 13-month collaboration, LST note completion rates increased from 27% to 81%, with 69 of 85 patients having a documented LST progress note in the EHR. PC approached nearly half of all patients on dialysis. Most patients agreed to be seen by the PC team, with 72% of those approached agreeing to a PC consultation. Previous research has suggested that having a trusted dialysis staff member included in GOCCs contributes to high acceptance rates.12

PC is a relatively uncommon partnership for nephrologists, and PC and hospice services are underutilized in patients on dialysis both nationally and within the VA.13-15 Our outcomes could be replicated, as PC is required at all VA sites.

Conclusions

The innovation of an interdisciplinary nephrology–PC collaboration was an important step in increasing high-quality GOCCs and eliciting patient preferences for LSTs among patients on dialysis. PC integration for patients on dialysis is associated with improved symptom management, fewer aggressive health care measures, and a higher likelihood of dying in one’s preferred setting.16 While this partnership focused on patients already receiving dialysis, successful PC interventions are felt most keenly upstream, before dialysis initiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their colleague, Mary McCabe, DNP, Quality Systems Improvement, Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital. The authors also acknowledge the clinical dedication of the dialysis social workers, Sarah Adam, LCSW, and Sarah Kraner, LCSW, without which this collaboration would not have been possible.

1. Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

2. Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1345-1352. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg105

3. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1206-1214. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036

4. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960809

5. Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force. Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1664-1672. doi:10.2215/CJN.04970512

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2nd ed. Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Goals of care conversations training for nurses, social workers, psychologists, and chaplains. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/team.asp

8. Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, et al. Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: an implementation study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):64. Published 2019 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0437-2

9. O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):855-866. doi:10.2215/CJN.11351015

10. Koncicki HM, Schell JO. Communication skills and decision making for elderly patients with advanced kidney disease: a guide for nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):688-695. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.032

11. Holley JL, Davison SN. Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: a need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):344-346. doi:10.2215/CJN.00290115

12. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1023-1028. doi:10.2215/CJN.01050306

13. Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1248-1255. doi:10.2215/CJN.00970306

14. Williams ME, Sandeep J, Catic A. Aging and ESRD demographics: consequences for the practice of dialysis. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):617-622. doi:10.1111/sdi.12029

15. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. FY 2020 annual report. Palliative and hospice care.

16. Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608-1614. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq630

17. Fadem SZ, Fadem J. HD mortality predictor. Accessed August 31, 2023. http://touchcalc.com/calculators/sq

18. National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Setting health care goals: a guide for people with hearth problems. Updated June 2016. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/GoCC/lst_booklet_for_patients_setting_health_care_goals_final.pdf

Estimates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among veterans range between 34% and 47% higher than in the general population.1 As patients progress to end-stage kidney disease and begin chronic dialysis, they often experience further functional and cognitive decline and a high symptom burden, leading to poor quality of life.2 Clinicians should initiate goals of care conversations (GOCCs) to support high-risk patients on dialysis to ensure that the interventions they receive align with their goals and preferences, since many patients on dialysis prefer measures focused on pain relief and discomfort.3,4 While proactive GOCCs are supported among nephrology associations, few such conversations take place.5,6 In one study, more than half of patients on dialysis stated they had not discussed end-of-life preferences in the past 12 months.4 As a result, patients may not consider the larger implications of receiving dialysis indefinitely as a life-sustaining treatment (LST).

In May 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for Ethics in Health Care rolled out the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative to proactively engage patients with serious illnesses, such as those with end-stage kidney disease, in GOCCs to clarify their preferences for LSTs.7 After comprehensive training, a preliminary audit at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois, revealed that only 27% of patients on dialysis had LST preferences documented in a standardized LST note.

Nephrologists cite multiple barriers to proactively addressing goals of care with patients with advanced CKD, including clinician discomfort, perceived lack of time, infrastructure, and training.8,9 Similarly, the absence of a multidisciplinary advance care planning approach—specifically bringing together palliative care (PC) clinicians with nephrologists—has been highlighted but not as well studied.10,11

In this quality improvement (QI) project, we aimed to establish a workflow to enhance collaboration between nephrology and PC and to increase the percentage of VA patients on outpatient hemodialysis who engaged in GOCCs, as documented by completion of an LST progress note in the VA’s electronic health record (EHR). We developed a collaboration among PC, nephrology, and social work to improve the rates of documented GOCCs and LST patients on dialysis.

Implementation

EHJVAH is a 1A facility with > 80 patients who receive outpatient hemodialysis on campus. At the time of this collaboration in the fall of 2019, the collaborative dialysis team comprised 2 social workers and a nephrologist. The PC team included a coordinator, 2 nurse practitioners, and 3 physicians. A QI nurse was involved in the initial data gathering for this project.

The PC and nephrology medical directors developed a workflow process that reflected organizational and clinical steps in planning, initiating, and completing GOCCs with patients on outpatient dialysis (Table 1). The proposed process engaged an interdisciplinary PC and nephrology group and was revised to incorporate staff suggestions.

A prospective review of 85 EHJVAH hemodialysis unit patient records was conducted between September 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020 (Table 2). We reviewed LST completion rates for all patients receiving dialysis within this timeframe. During the intervention period, the PC team approached 40 patients without LST notes to engage in GOCCs.

Discussion

Over the 13-month collaboration, LST note completion rates increased from 27% to 81%, with 69 of 85 patients having a documented LST progress note in the EHR. PC approached nearly half of all patients on dialysis. Most patients agreed to be seen by the PC team, with 72% of those approached agreeing to a PC consultation. Previous research has suggested that having a trusted dialysis staff member included in GOCCs contributes to high acceptance rates.12

PC is a relatively uncommon partnership for nephrologists, and PC and hospice services are underutilized in patients on dialysis both nationally and within the VA.13-15 Our outcomes could be replicated, as PC is required at all VA sites.

Conclusions

The innovation of an interdisciplinary nephrology–PC collaboration was an important step in increasing high-quality GOCCs and eliciting patient preferences for LSTs among patients on dialysis. PC integration for patients on dialysis is associated with improved symptom management, fewer aggressive health care measures, and a higher likelihood of dying in one’s preferred setting.16 While this partnership focused on patients already receiving dialysis, successful PC interventions are felt most keenly upstream, before dialysis initiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their colleague, Mary McCabe, DNP, Quality Systems Improvement, Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital. The authors also acknowledge the clinical dedication of the dialysis social workers, Sarah Adam, LCSW, and Sarah Kraner, LCSW, without which this collaboration would not have been possible.

Estimates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among veterans range between 34% and 47% higher than in the general population.1 As patients progress to end-stage kidney disease and begin chronic dialysis, they often experience further functional and cognitive decline and a high symptom burden, leading to poor quality of life.2 Clinicians should initiate goals of care conversations (GOCCs) to support high-risk patients on dialysis to ensure that the interventions they receive align with their goals and preferences, since many patients on dialysis prefer measures focused on pain relief and discomfort.3,4 While proactive GOCCs are supported among nephrology associations, few such conversations take place.5,6 In one study, more than half of patients on dialysis stated they had not discussed end-of-life preferences in the past 12 months.4 As a result, patients may not consider the larger implications of receiving dialysis indefinitely as a life-sustaining treatment (LST).

In May 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for Ethics in Health Care rolled out the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative to proactively engage patients with serious illnesses, such as those with end-stage kidney disease, in GOCCs to clarify their preferences for LSTs.7 After comprehensive training, a preliminary audit at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois, revealed that only 27% of patients on dialysis had LST preferences documented in a standardized LST note.

Nephrologists cite multiple barriers to proactively addressing goals of care with patients with advanced CKD, including clinician discomfort, perceived lack of time, infrastructure, and training.8,9 Similarly, the absence of a multidisciplinary advance care planning approach—specifically bringing together palliative care (PC) clinicians with nephrologists—has been highlighted but not as well studied.10,11

In this quality improvement (QI) project, we aimed to establish a workflow to enhance collaboration between nephrology and PC and to increase the percentage of VA patients on outpatient hemodialysis who engaged in GOCCs, as documented by completion of an LST progress note in the VA’s electronic health record (EHR). We developed a collaboration among PC, nephrology, and social work to improve the rates of documented GOCCs and LST patients on dialysis.

Implementation

EHJVAH is a 1A facility with > 80 patients who receive outpatient hemodialysis on campus. At the time of this collaboration in the fall of 2019, the collaborative dialysis team comprised 2 social workers and a nephrologist. The PC team included a coordinator, 2 nurse practitioners, and 3 physicians. A QI nurse was involved in the initial data gathering for this project.

The PC and nephrology medical directors developed a workflow process that reflected organizational and clinical steps in planning, initiating, and completing GOCCs with patients on outpatient dialysis (Table 1). The proposed process engaged an interdisciplinary PC and nephrology group and was revised to incorporate staff suggestions.

A prospective review of 85 EHJVAH hemodialysis unit patient records was conducted between September 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020 (Table 2). We reviewed LST completion rates for all patients receiving dialysis within this timeframe. During the intervention period, the PC team approached 40 patients without LST notes to engage in GOCCs.

Discussion

Over the 13-month collaboration, LST note completion rates increased from 27% to 81%, with 69 of 85 patients having a documented LST progress note in the EHR. PC approached nearly half of all patients on dialysis. Most patients agreed to be seen by the PC team, with 72% of those approached agreeing to a PC consultation. Previous research has suggested that having a trusted dialysis staff member included in GOCCs contributes to high acceptance rates.12

PC is a relatively uncommon partnership for nephrologists, and PC and hospice services are underutilized in patients on dialysis both nationally and within the VA.13-15 Our outcomes could be replicated, as PC is required at all VA sites.

Conclusions

The innovation of an interdisciplinary nephrology–PC collaboration was an important step in increasing high-quality GOCCs and eliciting patient preferences for LSTs among patients on dialysis. PC integration for patients on dialysis is associated with improved symptom management, fewer aggressive health care measures, and a higher likelihood of dying in one’s preferred setting.16 While this partnership focused on patients already receiving dialysis, successful PC interventions are felt most keenly upstream, before dialysis initiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their colleague, Mary McCabe, DNP, Quality Systems Improvement, Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital. The authors also acknowledge the clinical dedication of the dialysis social workers, Sarah Adam, LCSW, and Sarah Kraner, LCSW, without which this collaboration would not have been possible.

1. Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

2. Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1345-1352. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg105

3. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1206-1214. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036

4. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960809

5. Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force. Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1664-1672. doi:10.2215/CJN.04970512

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2nd ed. Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Goals of care conversations training for nurses, social workers, psychologists, and chaplains. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/team.asp

8. Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, et al. Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: an implementation study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):64. Published 2019 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0437-2

9. O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):855-866. doi:10.2215/CJN.11351015

10. Koncicki HM, Schell JO. Communication skills and decision making for elderly patients with advanced kidney disease: a guide for nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):688-695. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.032

11. Holley JL, Davison SN. Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: a need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):344-346. doi:10.2215/CJN.00290115

12. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1023-1028. doi:10.2215/CJN.01050306

13. Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1248-1255. doi:10.2215/CJN.00970306

14. Williams ME, Sandeep J, Catic A. Aging and ESRD demographics: consequences for the practice of dialysis. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):617-622. doi:10.1111/sdi.12029

15. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. FY 2020 annual report. Palliative and hospice care.

16. Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608-1614. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq630

17. Fadem SZ, Fadem J. HD mortality predictor. Accessed August 31, 2023. http://touchcalc.com/calculators/sq

18. National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Setting health care goals: a guide for people with hearth problems. Updated June 2016. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/GoCC/lst_booklet_for_patients_setting_health_care_goals_final.pdf

1. Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

2. Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1345-1352. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg105

3. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1206-1214. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036

4. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960809

5. Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force. Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1664-1672. doi:10.2215/CJN.04970512

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2nd ed. Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Goals of care conversations training for nurses, social workers, psychologists, and chaplains. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/team.asp

8. Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, et al. Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: an implementation study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):64. Published 2019 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0437-2

9. O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):855-866. doi:10.2215/CJN.11351015

10. Koncicki HM, Schell JO. Communication skills and decision making for elderly patients with advanced kidney disease: a guide for nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):688-695. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.032

11. Holley JL, Davison SN. Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: a need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):344-346. doi:10.2215/CJN.00290115

12. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1023-1028. doi:10.2215/CJN.01050306

13. Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1248-1255. doi:10.2215/CJN.00970306

14. Williams ME, Sandeep J, Catic A. Aging and ESRD demographics: consequences for the practice of dialysis. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):617-622. doi:10.1111/sdi.12029

15. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. FY 2020 annual report. Palliative and hospice care.

16. Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608-1614. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq630

17. Fadem SZ, Fadem J. HD mortality predictor. Accessed August 31, 2023. http://touchcalc.com/calculators/sq

18. National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Setting health care goals: a guide for people with hearth problems. Updated June 2016. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/GoCC/lst_booklet_for_patients_setting_health_care_goals_final.pdf

Use of Mobile Messaging System for Self-Management of Chemotherapy Symptoms in Patients with Advanced Cancer (FULL)

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

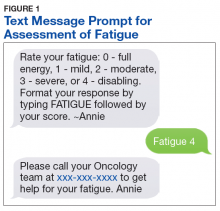

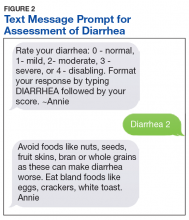

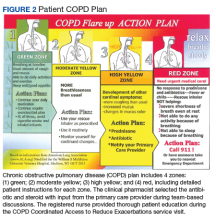

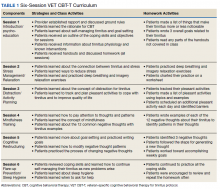

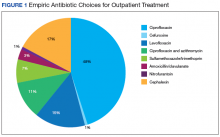

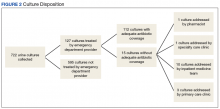

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.

18. Kataria L, Sundahl, C, Skalina L, et al. Text message reminders and intensive education improves positive airway pressure compliance and cognition in veterans with traumatic brain injury and obstructive sleep apnea: ANNIE pilot study (P1.097). Neurology, 2018; 90(suppl 15):P1.097.

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.

18. Kataria L, Sundahl, C, Skalina L, et al. Text message reminders and intensive education improves positive airway pressure compliance and cognition in veterans with traumatic brain injury and obstructive sleep apnea: ANNIE pilot study (P1.097). Neurology, 2018; 90(suppl 15):P1.097.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.

18. Kataria L, Sundahl, C, Skalina L, et al. Text message reminders and intensive education improves positive airway pressure compliance and cognition in veterans with traumatic brain injury and obstructive sleep apnea: ANNIE pilot study (P1.097). Neurology, 2018; 90(suppl 15):P1.097.

A Novel Pharmaceutical Care Model for High-Risk Patients

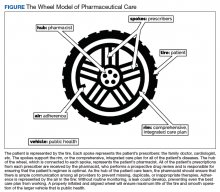

Nonadherence is a significant problem that has a negative impact on both patients and public health. Patients with multiple diseases often have complicated medication regimens, which can be difficult for them to manage. Unfortunately, nonadherence in these high-risk patients can have drastic consequences, including disease progression, hospitalization, and death, resulting in billions of dollars in unnecessary costs nationwide.1,2 The Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care (Figure) is a novel care model developed at the Gallup Indian Medical Center (GIMC) in New Mexico to address these problems by positioning pharmacy as a proactive service. The Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care was designed to improve adherence and patient outcomes and to encourage communication among the patient, pharmacists, prescribers, and other health care team members.

Pharmacists are central to managing patients’ medication therapies and coordinating communication among the health care providers (HCPs).1,3 Medication therapy management (MTM), a required component of Medicare Part D plans, helps ensure appropriate drug use and reduce the risk of adverse events.3 Since pharmacists receive prescriptions from all of the patient’s HCPs, patients may see pharmacists more often than they see any other HCP. GIMC is currently piloting a new clinic, the Medication Optimization, Synchronization, and Adherence Improvement Clinic (MOSAIC), that was created to implement the Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care. MOSAIC aims to provide proactive pharmacy services and continuous MTM to high-risk patients and will enable the effectiveness of this new pharmaceutical care model to be assessed.

Methods

Studies have identified certain populations who are at an increased risk for nonadherence: the elderly, patients with complex or extensive medication regimens, patients with multiple chronic medical conditions, substance misusers, certain ethnicities, patients of lower socioeconomic status, patients with limited literacy, and the homeless.2,4 Federal regulations require that Medicare Part D plans target beneficiaries who meet specific criteria for MTM programs. Under these rules, plans must target beneficiaries with ≥ 3 chronic diseases and ≥ 8 chronic medications, although plans also may include patients with fewer medications and diseases.3 Although the Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care is postulated to be an accurate model for the ideal care of all patients, initial implementation should be targeted toward populations who are likely to benefit the most from intervention. For these reasons, elderly Native American patients who have ≥ 2 chronic diseases and who take ≥ 5 chronic medications were targeted for initial enrollment in MOSAIC at GIMC.

Overview

In MOSAIC, pharmacists act as the hub of the pharmaceutical care wheel. Pharmacists work to ensure optimization of the patient’s comprehensive, integrated care plan—the rim of the wheel. As a part of this optimization process, MOSAIC pharmacists facilitate synchronization of the patient’s prescriptions to a monthly or quarterly target fill date. The patient’s current medication therapy is organized, and pharmacists track which medications are due to be filled instead of depending on the patient to request each prescription refill. This process effectively changes pharmacy from a requested service to a provided service.