User login

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Veterans With Tinnitus

Chronic tinnitus is defined as nonsensical, persistent sound in the head or ears with no external sound source that persists for more than 6 months.1 It is most commonly associated with sound trauma, aging, head injury, and damage to the ear structures.2 Tinnitus affects up to 30% of military veterans, a prevalence rate that is twice that of the nonveteran population.3 It also is the most common service-connected disability for veterans.4 In 2016, more than 1.6 million veterans had service-connected tinnitus.

Clinical management of tinnitus is the purview of audiologists, although their role in providing this service is not well defined.5 Following an audiologic evaluation for hearing loss, devices such as hearing aids, ear-level sound generators, or sounds played through speakers may be prescribed. However, effectiveness of these devices has been shown only when coupled with counseling.6 Counseling provided by audiologists often includes education about tinnitus etiology, maintaining hearing health, and use of sound to manage tinnitus. Length, content of care, and follow-up services vary among audiologists.

Given the importance of counseling and the added complexities of mental health and behavioral health comorbidities (eg, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders), various psychological therapies delivered by mental health specialists for tinnitus management have been explored.7-11 In fact, only psychological therapies have been documented to be efficacious for mitigating the negative effects of tinnitus on sleep, concentration, communication, and emotions.12 Among these approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has the strongest empirical support, particularly in terms of improving quality of life (QOL) and reducing depressive symptoms.11,12 Cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus is derived from social cognitive theory (SCT) and modeled after CBT for depression, anxiety, pain, and insomnia.11,13-15

Cognitive behavioral therapy helps patients with tinnitus reconceptualize the auditory problem as manageable and encourages acquisition, practice, and use of a range of specific tinnitus coping strategies to enhance perceptions of self-control and self-efficacy. Cognitive behavioral therapy involves a number of distinct therapeutic components, and there is no consensus about the efficacious components of CBT for tinnitus. For example, use of sound and purposeful exposure to tinnitus varies among providers.16 Additional questions about CBT pertain to its clinical implementation (eg, group vs individual sessions, frequency and length of sessions, in-person sessions vs delivery via telephone or Internet).

Programs offered at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities take veteran-specific factors into account to promote optimal engagement and outcomes. Factors that differentiate veterans from civilians include (1) increased probability of low health literacy and low socioeconomic status among seniors17; (2) increased likelihood of acoustic and/or psychological trauma3,18; (3) overrepresentation of males; and (4) increased probability of mental health diagnoses.19,20 At the same time, veterans are highly diverse with respect to age, academic achievement, cultural background, medical and mental health comorbidities, and economic resources.17 In spite of this diversity, most veterans are unified by their sense of camaraderie, loyalty to country, and adherence to discipline and order.21 Peer support and other variables such as compassionate understanding of their military experiences may be especially important to consider when designing behavioral interventions for veterans.

The present phenomenologic study was motivated by the need to develop and test a veteran-specific CBT for tinnitus protocol (VET CBT-T). To examine veterans’ experiences with VET CBT-T, we designed a small pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of VET CBT-T comparing it to structured audiologist counseling (AC). A mixed quantitative and qualitative approach was employed, including assessing veterans’ acceptance of care, identifying aspects that can be modified to improve outcomes, and obtaining feasibility data to guide refinements to VET CBT-T to inform a larger RCT.

Methods

The study used a single-blind, randomized, parallel treatment (VET CBT-T vs AC) concurrent design complemented by collection of qualitative data. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00724152).

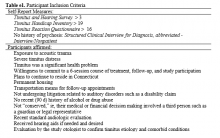

Measures

Four standardized measures were administered to potential participants. Callers were screened for eligibility by the research coordinator using Section A of the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS), which had been developed to screen candidates for tinnitus studies by phone.22 The THS contains 3 sections to identify problems related to tinnitus (Section A), hearing (Section B), and sound tolerance (Section C). Section A contains 4 items, each with a possible score of 0 to 4, which identifies tinnitus problems. Callers who were veterans and who met the necessary cutoff of 4 out of 16 possible points on Section A were invited to meet in-person with the research coordinator to obtain written informed consent and conduct a thorough assessment of eligibility.23

Three additional assessment measures were then administered sequentially to determine eligibility. The first 2 of these measures were readministered to eligible candidates who agreed to participate in the study and were used to examine outcomes:

(1) Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI): The 25-item THI provides an index score (0-100), with higher scores reflecting poorer QOL and more perceived functional limitations due to tinnitus.24 Candidates with scores of ≤ 19 were excluded.

(2) Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ): The TRQ measures perceived impact of tinnitus on QOL with emphasis on emotional consequences of tinnitus.25 Higher scores indicate more severe impact. Scores of ≥ 17 points purportedly indicate significant tinnitus disturbance. Candidates scoring < 17 were excluded.

(3) Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis, Abbreviated-Interview/Nonpatient (SCIDa-I/NP): The SCIDa-I/NP is a measure used to assess symptoms of psychopathology.26 Candidates with a lifetime history of psychosis were excluded.

Interventions

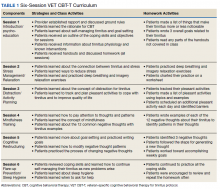

Each of the interventions was offered using 6 group sessions, with 2 or more participants, on an approximate weekly schedule.

VET CBT-T. Two primary texts served as resources for developing the VET CBT-T protocol: (1) the Psychological Management of Chronic Tinnitus: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach14; and (2) a manual for providing CBT for the treatment of chronic pain.27,28 Draft materials were developed by the clinical psychologist, including a clinician’s manual for providing VET CBT-T. Handouts were provided to each veteran. Components were compared to another unpublished CBT for tinnitus workbook.10

Key components targeted psychological difficulties including sleep disturbance, reduced functioning, low mood, nervousness, reduced pleasure from activities, and negative changes in relationships. The protocol emphasized basic information about tinnitus; relationships among tinnitus, acoustic trauma, and mental health symptoms; veterans’ sense of camaraderie and loyalty; and goal setting, making use of discipline and order veterans may desire.

To build rapport, the psychologist used reflective listening, encouraged interactive dialogue, and promoted participant understanding. Since tinnitus is thought to be exacerbated by stress, participants learned ways to manage stress and practiced relaxation exercises. Participants learned to create individualized, intersession goals that were realistic, specific, and measurable to promote self-efficacy. They also learned to list and increase pleasant activities to distract from tinnitus, improve QOL, and enable behavioral activation. Motivational interviewing addressed readiness, ambivalence, and resistance to achieving these specific goals. Participants also learned to identify and modify unhelpful thoughts about tinnitus (ie, cognitive restructuring).

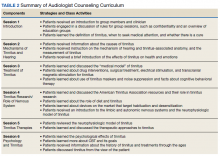

Audiologist Counseling (AC). To control for patient contact in VET CBT-T, the study audiologist created a 6-session counseling protocol. The AC emphasized education about tinnitus and available tinnitus interventions. Participants were encouraged to ask questions, share their tinnitus experiences, and cope with tinnitus by avoiding silence.

Quantitative Analysis

To assess baseline between-group differences, pretreatment (t1;immediately prior to attending the first group session) administrations of the THI and TRQ were compared using t tests. Demographics between groups were compared using the chi-square test.

The THI and TRQ were readministered following completion of the last group session (t2) and about 8 weeks after the last group session (t3). Because of the small sample size, required assumptions for analyzing parametric tests of linear effects were not met. Thus, only descriptive results and mean differences in scores on the THI and TRQ between these 3 assessment periods are presented. SPSS PASW Statistics 18.0 (Hong Kong, China) was used for analyses.

Qualitative Analysis

VET CBT-T. After each VET CBT-T session, veterans’ acceptance of the protocol was assessed using 4 questions: (1) Was the information presented to you today easy to understand? Yes/No. If no, why not? (2) Were the examples (if there were any) useful? Yes/No. If no, why not? (3) Was the way the information was presented by the group leader helpful? Yes/No. If no, why not? and (4) Please tell us what you thought about today’s group. Participants were encouraged to be honest and provide detailed feedback. To facilitate unbiased responding, the group leader left the room while a research assistant collected the comments.

Participants’ experiences and acceptance of the interventions were explored using a stepwise content analysis approach.29,30First, the feedback data were prepared for analysis by entering verbatim responses into a spreadsheet. Next, these responses were reviewed by the clinical psychologist who identified themes. Examination of data involved qualitative analyses in which the phenomenon of interest was veterans’ acceptance of the interventions. This process presumed that most veterans would respond favorably to the intervention and, thus, acknowledged that the clinical psychologist designed and delivered the intervention.

Any contrary or negative comments were flagged. However, neutral and positive comments also were analyzed and tallied. Notations within each comment were used to calculate the number of occurrences of themes. Similar themes with few responses were collapsed into a single theme when appropriate. Final themes and tallies were shared with an auditor familiar with tinnitus, psychology, and qualitative methods who made comments and checked tallies within each theme. The themes were revised based on this audit and retallied. The clinical psychologist then summarized the themes in text, which was reviewed by the auditor for accuracy in capturing the important emergent themes.

Next, themes were used to examine typed verbatim transcripts from the second and fifth sessions of the intervention. Thematic content derived from the above feedback was extracted from the transcripts by the clinical psychologist. Then the study audiologist read the transcripts to confirm or reject these comments as relevant to the themes. Additional comments were nominated by the study audiologist and reviewed by the clinical psychologist who finalized feedback thought to best represent the themes.

Results

One hundred ninety-six persons inquired about the study (Figure 1).

After being deemed eligible by the otologist as having tinnitus associated with sound trauma, the remaining 25 eligible and interested candidates were randomized into the 2 treatment arms. To reduce attrition, formation of groups took into account participants’ preferred appointment days and times. When 3 or more participants were allocated to a treatment arm, group sessions were scheduled. Five (20%) participants were lost to attrition, including 1 randomized to VET CBT-T and 2 to AC who dropped out prior to receiving any intervention, and 2 randomized to VET CBT-T who dropped out after attending 1 session. Reasons stated for dropping out included concerns they would not learn new information, inability to tolerate sound in a group, unexpected moves out of the area, lack of time, loss of interest, and family emergencies.

Quantitative Analysis

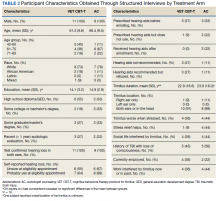

Participants in the 2 treatment arms did not differ significantly on the pretreatment (t1) THI (t = 1.39, df = 18, P = .18) or TRQ (t = 0.99, df = 18, P = .33) scores. Differences in THI scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 6.2; ACt1−t2 = 10.0) and from pretreatment to 8-week follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 4.4; ACt1−t3 = 9.1). Similarly, differences in mean TRQ index scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 5.3; ACt1−t2 = 7.6) and from pretreatment to 8 weeks follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 1.5; ACt1−t3 = 5.6). These mean differences reveal consistent reductions in mean index scores (improved tinnitus-related QOL) between time points for each treatment arm, but do not indicate statistically or clinically significant reductions of distress.

Qualitative Analysis

The 89 comments that participants provided after the 18 VET CBT-T sessions (3 series of 6 sessions each) were mostly positive (67 responses, 75%) (eTable 2).

Components of VET CBT-T and Number of Sessions (n = 53)

Psychoeducation and Sound Enrichment. Participants generally appreciated the psychoeducation component of VET CBT-T, including basic information about the prevalence of tinnitus, mechanics of the ear and hearing, and how an enriched sound environment may assist with coping (5 comments).

Stress Reduction. Two of the 14 participants who commented on the stress reduction session (via relaxation exercises) noted that it was helpful in their lives overall but “had no effect on tinnitus.”

Goal Setting. Nine participants noted that they valued the goal-setting strategies and long-term relapse planning, one writing that he was “…glad to be encouraged to document and set specific, documented goals each week.”

Cognitive Restructuring and Acceptance. Participants reported that the cognitive restructuring session was important for “accepting” their tinnitus (9 comments). Overall cognitive restructuring appeared to be well received by participants as a concept when learning ways to cope with tinnitus.

Distraction. Of the 8 comments that regarded the increasing-pleasant-activities session, 1 participant reported that the pleasant activities worksheet had a female bias and that activities on one of the worksheets “were not helpful and overlapped too much.” A participant suggested that group leaders allow participants to brainstorm pleasant activities using an open-ended format instead of using categories of pleasant activities. Participants generally found the increasing-pleasant-activities component very beneficial for managing tinnitus.

Self-Hypnosis and Exposure Therapy. Two components not presented during VET CBT-T were identified by participants as potentially desirable. One participant suggested providing information on self-hypnosis and another stated that he focuses on his tinnitus to cope, much like exposure therapy for tinnitus.

Number of Sessions. One participant wrote after the last (sixth) session that he was “glad it’s over” possibly suggesting the intervention was too long. Another participant stated at the fifth session, “I basically want to get out of here—out of this, out of these meetings.” Conversely a participant stated, “I was kind of hoping there was one more after next week.” Another participant explained the intervention itself can be in conflict with its own stated goals of attending less to tinnitus.

Leader, Materials, and Presentations (n = 16).

Overall, the participants had positive experiences (15 comments) with their study therapist. They noted that the group leader was “flexible” and “did a great job of facilitating discussion.” One participant commented on the need for better visual presentations of the information and the need for the group leader to “use her own words” rather than reading the content.

Previous Use of CBT Skills (n = 5).

Five participants noted that information presented was “not new” and that they had acquired the coping skills spontaneously years earlier. Two expressed relief that some of the ways they had been dealing with their tinnitus prior to the intervention were actually recommended. One discussed that reviewing skills that he had already implemented was helpful.

Hope, Anger, and Mental Health (n = 8).

Three participants indicated the intervention gave them “hope” that they will learn ways to cope with tinnitus. One noted that the discussion regarding depression as a commonly co-occurring condition with tinnitus should include a better description of depressive symptoms. Two expressed relief to receive help for their frustration and anger resulting from tinnitus, and 1 participant discussed the added frustration of hearing loss with tinnitus. Excessive alcohol use to cope with tinnitus and the comorbidity of tinnitus and PTSD also were discussed.

Group Cohesiveness (n = 8)/Discord (n = 2).

Many group members commented that they enjoyed listening to information about tinnitus and sharing their experiences. There was friendly interaction and discussion among most of the participants. They commented that it was informative to see that others were coming forward for help and were interested to hear others’ experiences. The group format was mostly welcomed and appreciated. However, group discord occurred when topics other than tinnitus were shared, such as recovery from substance abuse. Two feedback comments indicated that this discussion was unwelcomed.

Discussion

This pilot study provides evidence that at least some of the veterans who were eligible and participated accrued benefit from either AC or VET CBT-T. There also is evidence that a structured and intensive counseling approach by an audiologist that does not include sound therapy is beneficial. Participants generally found that the interventions were acceptable for understanding basic information about tinnitus, and those in the VET CBT-T treatment arm reported improvements in problem solving and coping.

The planned qualitative analyses enabled in-depth examination of intervention feedback from participants and revealed important themes for modifying the VET CBT-T intervention, which occurred following completion of this pilot study. Further, these themes echo the success in creating a unique, veteran-centric, CBT intervention for tinnitus management.

Primarily, participants indicated that education about tinnitus prevalence, etiology, and sound enrichment assisted in coping with tinnitus. This theme also reflects the protocol’s emphasis on health literacy. The wide availability of misinformation on tinnitus, along with the potential for monetary scams, underlies the need for well-designed and research-informed tinnitus education programs. Helping veterans distinguish facts and myths is a potentially important element of tinnitus management. Experiences coping with trauma were salient as participants diverged in their opinions regarding the appropriateness of discussing these issues during a tinnitus management group.

Specific themes emerged regarding the relevance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and substance use to cope with tinnitus. Comfort levels when hearing and discussing these symptoms varied among participants. Due to the high comorbidities of mental health disorders and tinnitus, this theme is important to consider when designing tinnitus management programs. Other qualitative themes served to validate peer support and that the veteran-centric protocol was acceptable, including positive regard for goal setting, indicating that adherence to discipline and order had been addressed.

Identified VET CBT-T Modifications

There were multiple indicators that the rationale for sessions needed to be clarified. Participants highlighted the need to hear clear expectations about what the coping skills would address and multiple reminders regarding the goals of relaxation exercises for tinnitus. Some expressed concern about their lack of concentration during the relaxation exercises. A concern that was discussed with participants only during the informed consent process was the possibility that the intervention could increase focus on tinnitus and, thus, temporarily increase tinnitus distress while receiving the intervention.

Need for Interdisciplinary Care

Perhaps the fact that both interventions were beneficial is not surprising since AC as delivered in this study was designed to be an active intervention that incorporated education and support, including some components similar to those included in VET CBT-T. It appears that AC designed to match the CBT intervention in terms of number of sessions among other enhancements suggests that this intervention may be efficacious. The AC intervention offered support and education about tinnitus; however, sound therapy was not provided despite some empirical support for its use.31 Future research should examine whether sound therapy adds benefit to an intensive and structured AC approach.

It has been proposed that a combination of CBT delivered by a mental health provider and AC should be implemented as an optimal tinnitus management protocol.31,32 Results of this and a number of other recent studies 16,32,33 encourage an integrated, interdisciplinary approach.

Findings of the present study were applied toward development of a hierarchical and interdisciplinary tinnitus management protocol, Progressive Tinnitus Management (PTM).22,34 Components of VET CBT-T were selected for the intervention provided with PTM, modified as per the feedback from participants in this study. This approach was combined with components of the AC intervention, further complemented by sound therapy. The new combined protocol was tested in a pilot telephone study of PTM for veterans and military members with positive results.32 Two VA-supported RCTs of PTM have since been completed.35,36 Results indicate that relative to wait list control, PTM is effective in mitigating negative effects of tinnitus.

Last, after this pilot study, the protocol was modified to address participants’ concerns that their primary care and other providers were unaware that interventions for tinnitus exist. Providers offering tinnitus care are now encouraged to share its availability with veterans and other clinicians. This study provides compelling evidence that veterans respond to messages of hope from providers that they do not needlessly have to suffer alone. Rather than telling veterans to “just live with it,” primary care providers should be able to offer ideas and services for learning how to live with tinnitus.

Future Directions

Future revisions of VET CBT-T could incorporate “acceptance” as a concept for coping with tinnitus, components such as self-hypnosis and exposure therapy, and strategies for coping with hearing loss and communication difficulties. Reexamination of the number and length of sessions also is encouraged, as well as integration of evidence-based interventions for comorbid conditions such as PTSD, substance use disorders, and insomnia. Perhaps increasing the use of peer support services would help reach veterans concerned by the stigma of receiving mental health care. Some veterans were dissatisfied with hearing about others’ mental health concerns. It may be beneficial to offer tinnitus interventions to cohorts of veterans identified with specific comorbid mental health or substance use disorders. However, peer support may be more important than protecting veterans from hearing about others’ mental health concerns as social cognitive theory suggests.

Limitations

This feasibility study’s strict inclusion criteria resulted in a small but well-defined sample that may not be representative of the larger population of veterans who could potentially benefit from these interventions. The extensive evaluation requirements and eligibility requirements likely enhanced the internal validity of the trial but may have compromised the external validity and generalizability of the study findings.

While a few women were assessed during the eligibility process, unfortunately, only men were deemed eligible. It is therefore unknown how women veterans would receive this protocol. Currently there is a bias in selecting male participants for tinnitus research. It is hoped that in the future a sample of women veterans could also provide feedback on this tinnitus management protocol developed by the VHA.

The fact that a large proportion of those who made initial contact about the study decided not to follow up is not inconsistent with studies of similar psychological interventions.37 Challenges related to engaging otherwise appropriate candidates in psychological interventions for a range of chronic health concerns have been well described and may apply to tinnitus management.

Conclusion

The qualitative feedback from participants was generally positive for both protocols. Emergent themes confirmed the need for a veteran-specific intervention while highlighting individual veterans’ needs. Transcripts from sessions provided additional descriptive information that identified changes to the protocols that would improve veterans’ receipt of care. Due to the abundance of veterans with tinnitus and the needs of veterans in terms of health care delivery and receipt, an interdisciplinary CBT-plus-AC protocol was created that is specific to and accepted by veterans with tinnitus.

Refinements to the VET CBT-T protocol were identified that led to development of PTM that was the subject of another small study, which then led to the authors’ 2 larger RCTs. Attempts were made to include greater attention to the mental health concerns of veterans both in terms of education and in offering sensitive delivery of the protocol. Session content was used to create an organized, visual presentation that follows an organized workbook.22,35 Refinements to the protocol are ongoing.

Acknowledgments

This material was based on work supported by US Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D): (1) R.D. Kerns’ Pilot Merit Grant #C6324P and (2) C.J. (Kendall) Schmidt’s Career Development Award-1 #D6848M. The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance from Rebecca Czlapinski, MA; Kathryn LaChappelle, MPH; and Emily Thielman, MS, for the conduct of the study, data collection and management, and preparation of this manuscript.

1. Henry JA. “Measurement” of tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(8):e276-e285.

2. Hoffman HJ, Reed GW. Epidemiology of tinnitus. In Snow JB, ed. Tinnitus: Theory and Management. Hamilton, Canada: BC Becker; 2004:16-41.

3. Folmer RL, Theodoroff SM, Martin WH, Shi Y. Experimental, controversial, and futuristic treatments for chronic tinnitus. J Am Acad Audiol. 2014;25(1):106-125.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Benefits Administration annual benefits report fiscal year 2016. https://www.benefits.va.gov/REPORTS/abr/ABR-All_Sec tions_FY16_06292017.pdf . Accessed June 19, 2018.

5. Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Myers PJ, Schechter MA. The role of audiologic evaluation in progressive audiologic tinnitus management. Trends Amplif. 2008;12(3):170-187.

6. Hoare DJ, Searchfield GD, El Refaie A, Henry JA. Sound therapy for tinnitus management: practicable options. J Am Acad Audiol. 2014;25(1):62-75.

7. Andersson G, Porsaeus D, Wiklund M, Kaldo V, Larsen HC. Treatment of tinnitus in the elderly: a controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy. Int J Audiol. 2005;44(11):671-675.

8. Henry JL, Wilson PH. Coping with tinnitus: two studies of psychological and audiological characteristics of patients with high and low tinnitus-related distress. Int Tinnitus J. 1995;1(2):85-92.

9. Henry JL, Wilson PH. The psychological management of tinnitus: comparison of a combined cognitive educational program, education alone and a waiting-list control. Int Tinnitus J. 1996;2:9-20.

10. Robinson SK, Viirre ES, Bailey KA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for tinnitus. Int Tinnitus J. 2008;14(2):119-126.

11. Martinez-Devesa P, Perera R, Theodoulou M, Waddell A. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(9):CD005233.

12. Tunkel DE, Bauer CA, Sun GH, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(Suppl)(2):S1-S40.

13. Beck JS. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

14. Henry JL, Wilson PH. The Psychological Management of Chronic Tinnitus : A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001.

15. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143-164.

16. Cima RF, Andersson G, Schmidt CJ, Henry JA. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for tinnitus: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Audiol. 2014;25(1):29-61.

17. Rodriguez V, Andrade AD, García-Retamero R, et al. Health literacy, numeracy, and graphical literacy among veterans in primary care and their effect on shared decision making and trust in physicians. J Health Commun. 2013;18(suppl 1):273-289.

18. Seal KH, Metzler TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Marmar CR. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs health care, 2002-2008. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1651-1658.

19. Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):614-623.

20. Zivin K, McCarthy JF, McCammon RJ, et al. Health-related quality of life and utilities among patients with depression in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(11):1331-1334.

21. Costa DL, Kahn ME. Health, wartime stress, and unit cohesion: evidence from Union Army veterans. Demography. 2010;47(1):45-66.

22. Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Myers PJ, Kendall (Schmidt) CJ. Progressive Tinnitus Management: Clinical Handbook for Audiologists. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing; 2010.

23. Henry JA, Schechter MA, Loovis CL, et al. Clinical management of tinnitus using a “progressive intervention” approach. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(4 suppl 2):95-116.

24. Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122(2):143-148.

25. Wilson PH, Henry JL, Bowen M, Haralambous G. Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire: psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. J Speech Hear Res. 1991;34(1):197-201.

26. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Clinical Version, Administration Booklet. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2012.

27. Kerns RD, Thorn BE, Dixon KE. Psychological treatments for persistent pain: an introduction. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(11):1327-1331.

28. Otis JD. Managing Chronic Pain: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach. New York, NY: Oxford; 2007.

29. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340.

30. Mertens DM. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity With Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009 .

31. Hobson J, Chisholm E, El Refaie A. Sound therapy (masking) in the management of tinnitus in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD006371.

32. Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Myers PJ, et al. Pilot study to develop telehealth tinnitus management for persons with and without traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(7):1025-1042.

33. Weise C, Heinecke K, Rief W. Biofeedback-based behavioral treatment for chronic tinnitus: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(6):1046-1057.

34. Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Myers PJ, Kendall (Schmidt) CJ. How to Manage Your Tinnitus: A Step-by-Step Workbook, 3rd ed. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing; 2010.

35. Henry JA, Thielman EJ, Zaugg TL, et al. Randomized controlled trial in clinical settings to evaluate effectiveness of coping skills education used with Progressive Tinnitus Management. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2017;60(5):1378-1397.

36. Henry, JA, Thielman, E, Zaugg, et al. Telephone-based progressive tinnitus management for persons with and without traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Ear Hear. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

37. Chang MW, Nitzke S, Brown R, et al. Recruitment challenges and enrollment observations from a community based intervention (Mothers In Motion) for low-income overweight and obese women. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;5:26-33.

Chronic tinnitus is defined as nonsensical, persistent sound in the head or ears with no external sound source that persists for more than 6 months.1 It is most commonly associated with sound trauma, aging, head injury, and damage to the ear structures.2 Tinnitus affects up to 30% of military veterans, a prevalence rate that is twice that of the nonveteran population.3 It also is the most common service-connected disability for veterans.4 In 2016, more than 1.6 million veterans had service-connected tinnitus.

Clinical management of tinnitus is the purview of audiologists, although their role in providing this service is not well defined.5 Following an audiologic evaluation for hearing loss, devices such as hearing aids, ear-level sound generators, or sounds played through speakers may be prescribed. However, effectiveness of these devices has been shown only when coupled with counseling.6 Counseling provided by audiologists often includes education about tinnitus etiology, maintaining hearing health, and use of sound to manage tinnitus. Length, content of care, and follow-up services vary among audiologists.

Given the importance of counseling and the added complexities of mental health and behavioral health comorbidities (eg, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders), various psychological therapies delivered by mental health specialists for tinnitus management have been explored.7-11 In fact, only psychological therapies have been documented to be efficacious for mitigating the negative effects of tinnitus on sleep, concentration, communication, and emotions.12 Among these approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has the strongest empirical support, particularly in terms of improving quality of life (QOL) and reducing depressive symptoms.11,12 Cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus is derived from social cognitive theory (SCT) and modeled after CBT for depression, anxiety, pain, and insomnia.11,13-15

Cognitive behavioral therapy helps patients with tinnitus reconceptualize the auditory problem as manageable and encourages acquisition, practice, and use of a range of specific tinnitus coping strategies to enhance perceptions of self-control and self-efficacy. Cognitive behavioral therapy involves a number of distinct therapeutic components, and there is no consensus about the efficacious components of CBT for tinnitus. For example, use of sound and purposeful exposure to tinnitus varies among providers.16 Additional questions about CBT pertain to its clinical implementation (eg, group vs individual sessions, frequency and length of sessions, in-person sessions vs delivery via telephone or Internet).

Programs offered at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities take veteran-specific factors into account to promote optimal engagement and outcomes. Factors that differentiate veterans from civilians include (1) increased probability of low health literacy and low socioeconomic status among seniors17; (2) increased likelihood of acoustic and/or psychological trauma3,18; (3) overrepresentation of males; and (4) increased probability of mental health diagnoses.19,20 At the same time, veterans are highly diverse with respect to age, academic achievement, cultural background, medical and mental health comorbidities, and economic resources.17 In spite of this diversity, most veterans are unified by their sense of camaraderie, loyalty to country, and adherence to discipline and order.21 Peer support and other variables such as compassionate understanding of their military experiences may be especially important to consider when designing behavioral interventions for veterans.

The present phenomenologic study was motivated by the need to develop and test a veteran-specific CBT for tinnitus protocol (VET CBT-T). To examine veterans’ experiences with VET CBT-T, we designed a small pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of VET CBT-T comparing it to structured audiologist counseling (AC). A mixed quantitative and qualitative approach was employed, including assessing veterans’ acceptance of care, identifying aspects that can be modified to improve outcomes, and obtaining feasibility data to guide refinements to VET CBT-T to inform a larger RCT.

Methods

The study used a single-blind, randomized, parallel treatment (VET CBT-T vs AC) concurrent design complemented by collection of qualitative data. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00724152).

Measures

Four standardized measures were administered to potential participants. Callers were screened for eligibility by the research coordinator using Section A of the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS), which had been developed to screen candidates for tinnitus studies by phone.22 The THS contains 3 sections to identify problems related to tinnitus (Section A), hearing (Section B), and sound tolerance (Section C). Section A contains 4 items, each with a possible score of 0 to 4, which identifies tinnitus problems. Callers who were veterans and who met the necessary cutoff of 4 out of 16 possible points on Section A were invited to meet in-person with the research coordinator to obtain written informed consent and conduct a thorough assessment of eligibility.23

Three additional assessment measures were then administered sequentially to determine eligibility. The first 2 of these measures were readministered to eligible candidates who agreed to participate in the study and were used to examine outcomes:

(1) Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI): The 25-item THI provides an index score (0-100), with higher scores reflecting poorer QOL and more perceived functional limitations due to tinnitus.24 Candidates with scores of ≤ 19 were excluded.

(2) Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ): The TRQ measures perceived impact of tinnitus on QOL with emphasis on emotional consequences of tinnitus.25 Higher scores indicate more severe impact. Scores of ≥ 17 points purportedly indicate significant tinnitus disturbance. Candidates scoring < 17 were excluded.

(3) Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis, Abbreviated-Interview/Nonpatient (SCIDa-I/NP): The SCIDa-I/NP is a measure used to assess symptoms of psychopathology.26 Candidates with a lifetime history of psychosis were excluded.

Interventions

Each of the interventions was offered using 6 group sessions, with 2 or more participants, on an approximate weekly schedule.

VET CBT-T. Two primary texts served as resources for developing the VET CBT-T protocol: (1) the Psychological Management of Chronic Tinnitus: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach14; and (2) a manual for providing CBT for the treatment of chronic pain.27,28 Draft materials were developed by the clinical psychologist, including a clinician’s manual for providing VET CBT-T. Handouts were provided to each veteran. Components were compared to another unpublished CBT for tinnitus workbook.10

Key components targeted psychological difficulties including sleep disturbance, reduced functioning, low mood, nervousness, reduced pleasure from activities, and negative changes in relationships. The protocol emphasized basic information about tinnitus; relationships among tinnitus, acoustic trauma, and mental health symptoms; veterans’ sense of camaraderie and loyalty; and goal setting, making use of discipline and order veterans may desire.

To build rapport, the psychologist used reflective listening, encouraged interactive dialogue, and promoted participant understanding. Since tinnitus is thought to be exacerbated by stress, participants learned ways to manage stress and practiced relaxation exercises. Participants learned to create individualized, intersession goals that were realistic, specific, and measurable to promote self-efficacy. They also learned to list and increase pleasant activities to distract from tinnitus, improve QOL, and enable behavioral activation. Motivational interviewing addressed readiness, ambivalence, and resistance to achieving these specific goals. Participants also learned to identify and modify unhelpful thoughts about tinnitus (ie, cognitive restructuring).

Audiologist Counseling (AC). To control for patient contact in VET CBT-T, the study audiologist created a 6-session counseling protocol. The AC emphasized education about tinnitus and available tinnitus interventions. Participants were encouraged to ask questions, share their tinnitus experiences, and cope with tinnitus by avoiding silence.

Quantitative Analysis

To assess baseline between-group differences, pretreatment (t1;immediately prior to attending the first group session) administrations of the THI and TRQ were compared using t tests. Demographics between groups were compared using the chi-square test.

The THI and TRQ were readministered following completion of the last group session (t2) and about 8 weeks after the last group session (t3). Because of the small sample size, required assumptions for analyzing parametric tests of linear effects were not met. Thus, only descriptive results and mean differences in scores on the THI and TRQ between these 3 assessment periods are presented. SPSS PASW Statistics 18.0 (Hong Kong, China) was used for analyses.

Qualitative Analysis

VET CBT-T. After each VET CBT-T session, veterans’ acceptance of the protocol was assessed using 4 questions: (1) Was the information presented to you today easy to understand? Yes/No. If no, why not? (2) Were the examples (if there were any) useful? Yes/No. If no, why not? (3) Was the way the information was presented by the group leader helpful? Yes/No. If no, why not? and (4) Please tell us what you thought about today’s group. Participants were encouraged to be honest and provide detailed feedback. To facilitate unbiased responding, the group leader left the room while a research assistant collected the comments.

Participants’ experiences and acceptance of the interventions were explored using a stepwise content analysis approach.29,30First, the feedback data were prepared for analysis by entering verbatim responses into a spreadsheet. Next, these responses were reviewed by the clinical psychologist who identified themes. Examination of data involved qualitative analyses in which the phenomenon of interest was veterans’ acceptance of the interventions. This process presumed that most veterans would respond favorably to the intervention and, thus, acknowledged that the clinical psychologist designed and delivered the intervention.

Any contrary or negative comments were flagged. However, neutral and positive comments also were analyzed and tallied. Notations within each comment were used to calculate the number of occurrences of themes. Similar themes with few responses were collapsed into a single theme when appropriate. Final themes and tallies were shared with an auditor familiar with tinnitus, psychology, and qualitative methods who made comments and checked tallies within each theme. The themes were revised based on this audit and retallied. The clinical psychologist then summarized the themes in text, which was reviewed by the auditor for accuracy in capturing the important emergent themes.

Next, themes were used to examine typed verbatim transcripts from the second and fifth sessions of the intervention. Thematic content derived from the above feedback was extracted from the transcripts by the clinical psychologist. Then the study audiologist read the transcripts to confirm or reject these comments as relevant to the themes. Additional comments were nominated by the study audiologist and reviewed by the clinical psychologist who finalized feedback thought to best represent the themes.

Results

One hundred ninety-six persons inquired about the study (Figure 1).

After being deemed eligible by the otologist as having tinnitus associated with sound trauma, the remaining 25 eligible and interested candidates were randomized into the 2 treatment arms. To reduce attrition, formation of groups took into account participants’ preferred appointment days and times. When 3 or more participants were allocated to a treatment arm, group sessions were scheduled. Five (20%) participants were lost to attrition, including 1 randomized to VET CBT-T and 2 to AC who dropped out prior to receiving any intervention, and 2 randomized to VET CBT-T who dropped out after attending 1 session. Reasons stated for dropping out included concerns they would not learn new information, inability to tolerate sound in a group, unexpected moves out of the area, lack of time, loss of interest, and family emergencies.

Quantitative Analysis

Participants in the 2 treatment arms did not differ significantly on the pretreatment (t1) THI (t = 1.39, df = 18, P = .18) or TRQ (t = 0.99, df = 18, P = .33) scores. Differences in THI scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 6.2; ACt1−t2 = 10.0) and from pretreatment to 8-week follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 4.4; ACt1−t3 = 9.1). Similarly, differences in mean TRQ index scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 5.3; ACt1−t2 = 7.6) and from pretreatment to 8 weeks follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 1.5; ACt1−t3 = 5.6). These mean differences reveal consistent reductions in mean index scores (improved tinnitus-related QOL) between time points for each treatment arm, but do not indicate statistically or clinically significant reductions of distress.

Qualitative Analysis

The 89 comments that participants provided after the 18 VET CBT-T sessions (3 series of 6 sessions each) were mostly positive (67 responses, 75%) (eTable 2).

Components of VET CBT-T and Number of Sessions (n = 53)

Psychoeducation and Sound Enrichment. Participants generally appreciated the psychoeducation component of VET CBT-T, including basic information about the prevalence of tinnitus, mechanics of the ear and hearing, and how an enriched sound environment may assist with coping (5 comments).

Stress Reduction. Two of the 14 participants who commented on the stress reduction session (via relaxation exercises) noted that it was helpful in their lives overall but “had no effect on tinnitus.”

Goal Setting. Nine participants noted that they valued the goal-setting strategies and long-term relapse planning, one writing that he was “…glad to be encouraged to document and set specific, documented goals each week.”

Cognitive Restructuring and Acceptance. Participants reported that the cognitive restructuring session was important for “accepting” their tinnitus (9 comments). Overall cognitive restructuring appeared to be well received by participants as a concept when learning ways to cope with tinnitus.

Distraction. Of the 8 comments that regarded the increasing-pleasant-activities session, 1 participant reported that the pleasant activities worksheet had a female bias and that activities on one of the worksheets “were not helpful and overlapped too much.” A participant suggested that group leaders allow participants to brainstorm pleasant activities using an open-ended format instead of using categories of pleasant activities. Participants generally found the increasing-pleasant-activities component very beneficial for managing tinnitus.

Self-Hypnosis and Exposure Therapy. Two components not presented during VET CBT-T were identified by participants as potentially desirable. One participant suggested providing information on self-hypnosis and another stated that he focuses on his tinnitus to cope, much like exposure therapy for tinnitus.

Number of Sessions. One participant wrote after the last (sixth) session that he was “glad it’s over” possibly suggesting the intervention was too long. Another participant stated at the fifth session, “I basically want to get out of here—out of this, out of these meetings.” Conversely a participant stated, “I was kind of hoping there was one more after next week.” Another participant explained the intervention itself can be in conflict with its own stated goals of attending less to tinnitus.

Leader, Materials, and Presentations (n = 16).

Overall, the participants had positive experiences (15 comments) with their study therapist. They noted that the group leader was “flexible” and “did a great job of facilitating discussion.” One participant commented on the need for better visual presentations of the information and the need for the group leader to “use her own words” rather than reading the content.

Previous Use of CBT Skills (n = 5).

Five participants noted that information presented was “not new” and that they had acquired the coping skills spontaneously years earlier. Two expressed relief that some of the ways they had been dealing with their tinnitus prior to the intervention were actually recommended. One discussed that reviewing skills that he had already implemented was helpful.

Hope, Anger, and Mental Health (n = 8).

Three participants indicated the intervention gave them “hope” that they will learn ways to cope with tinnitus. One noted that the discussion regarding depression as a commonly co-occurring condition with tinnitus should include a better description of depressive symptoms. Two expressed relief to receive help for their frustration and anger resulting from tinnitus, and 1 participant discussed the added frustration of hearing loss with tinnitus. Excessive alcohol use to cope with tinnitus and the comorbidity of tinnitus and PTSD also were discussed.

Group Cohesiveness (n = 8)/Discord (n = 2).

Many group members commented that they enjoyed listening to information about tinnitus and sharing their experiences. There was friendly interaction and discussion among most of the participants. They commented that it was informative to see that others were coming forward for help and were interested to hear others’ experiences. The group format was mostly welcomed and appreciated. However, group discord occurred when topics other than tinnitus were shared, such as recovery from substance abuse. Two feedback comments indicated that this discussion was unwelcomed.

Discussion

This pilot study provides evidence that at least some of the veterans who were eligible and participated accrued benefit from either AC or VET CBT-T. There also is evidence that a structured and intensive counseling approach by an audiologist that does not include sound therapy is beneficial. Participants generally found that the interventions were acceptable for understanding basic information about tinnitus, and those in the VET CBT-T treatment arm reported improvements in problem solving and coping.

The planned qualitative analyses enabled in-depth examination of intervention feedback from participants and revealed important themes for modifying the VET CBT-T intervention, which occurred following completion of this pilot study. Further, these themes echo the success in creating a unique, veteran-centric, CBT intervention for tinnitus management.

Primarily, participants indicated that education about tinnitus prevalence, etiology, and sound enrichment assisted in coping with tinnitus. This theme also reflects the protocol’s emphasis on health literacy. The wide availability of misinformation on tinnitus, along with the potential for monetary scams, underlies the need for well-designed and research-informed tinnitus education programs. Helping veterans distinguish facts and myths is a potentially important element of tinnitus management. Experiences coping with trauma were salient as participants diverged in their opinions regarding the appropriateness of discussing these issues during a tinnitus management group.

Specific themes emerged regarding the relevance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and substance use to cope with tinnitus. Comfort levels when hearing and discussing these symptoms varied among participants. Due to the high comorbidities of mental health disorders and tinnitus, this theme is important to consider when designing tinnitus management programs. Other qualitative themes served to validate peer support and that the veteran-centric protocol was acceptable, including positive regard for goal setting, indicating that adherence to discipline and order had been addressed.

Identified VET CBT-T Modifications

There were multiple indicators that the rationale for sessions needed to be clarified. Participants highlighted the need to hear clear expectations about what the coping skills would address and multiple reminders regarding the goals of relaxation exercises for tinnitus. Some expressed concern about their lack of concentration during the relaxation exercises. A concern that was discussed with participants only during the informed consent process was the possibility that the intervention could increase focus on tinnitus and, thus, temporarily increase tinnitus distress while receiving the intervention.

Need for Interdisciplinary Care

Perhaps the fact that both interventions were beneficial is not surprising since AC as delivered in this study was designed to be an active intervention that incorporated education and support, including some components similar to those included in VET CBT-T. It appears that AC designed to match the CBT intervention in terms of number of sessions among other enhancements suggests that this intervention may be efficacious. The AC intervention offered support and education about tinnitus; however, sound therapy was not provided despite some empirical support for its use.31 Future research should examine whether sound therapy adds benefit to an intensive and structured AC approach.

It has been proposed that a combination of CBT delivered by a mental health provider and AC should be implemented as an optimal tinnitus management protocol.31,32 Results of this and a number of other recent studies 16,32,33 encourage an integrated, interdisciplinary approach.

Findings of the present study were applied toward development of a hierarchical and interdisciplinary tinnitus management protocol, Progressive Tinnitus Management (PTM).22,34 Components of VET CBT-T were selected for the intervention provided with PTM, modified as per the feedback from participants in this study. This approach was combined with components of the AC intervention, further complemented by sound therapy. The new combined protocol was tested in a pilot telephone study of PTM for veterans and military members with positive results.32 Two VA-supported RCTs of PTM have since been completed.35,36 Results indicate that relative to wait list control, PTM is effective in mitigating negative effects of tinnitus.

Last, after this pilot study, the protocol was modified to address participants’ concerns that their primary care and other providers were unaware that interventions for tinnitus exist. Providers offering tinnitus care are now encouraged to share its availability with veterans and other clinicians. This study provides compelling evidence that veterans respond to messages of hope from providers that they do not needlessly have to suffer alone. Rather than telling veterans to “just live with it,” primary care providers should be able to offer ideas and services for learning how to live with tinnitus.

Future Directions

Future revisions of VET CBT-T could incorporate “acceptance” as a concept for coping with tinnitus, components such as self-hypnosis and exposure therapy, and strategies for coping with hearing loss and communication difficulties. Reexamination of the number and length of sessions also is encouraged, as well as integration of evidence-based interventions for comorbid conditions such as PTSD, substance use disorders, and insomnia. Perhaps increasing the use of peer support services would help reach veterans concerned by the stigma of receiving mental health care. Some veterans were dissatisfied with hearing about others’ mental health concerns. It may be beneficial to offer tinnitus interventions to cohorts of veterans identified with specific comorbid mental health or substance use disorders. However, peer support may be more important than protecting veterans from hearing about others’ mental health concerns as social cognitive theory suggests.

Limitations

This feasibility study’s strict inclusion criteria resulted in a small but well-defined sample that may not be representative of the larger population of veterans who could potentially benefit from these interventions. The extensive evaluation requirements and eligibility requirements likely enhanced the internal validity of the trial but may have compromised the external validity and generalizability of the study findings.

While a few women were assessed during the eligibility process, unfortunately, only men were deemed eligible. It is therefore unknown how women veterans would receive this protocol. Currently there is a bias in selecting male participants for tinnitus research. It is hoped that in the future a sample of women veterans could also provide feedback on this tinnitus management protocol developed by the VHA.

The fact that a large proportion of those who made initial contact about the study decided not to follow up is not inconsistent with studies of similar psychological interventions.37 Challenges related to engaging otherwise appropriate candidates in psychological interventions for a range of chronic health concerns have been well described and may apply to tinnitus management.

Conclusion

The qualitative feedback from participants was generally positive for both protocols. Emergent themes confirmed the need for a veteran-specific intervention while highlighting individual veterans’ needs. Transcripts from sessions provided additional descriptive information that identified changes to the protocols that would improve veterans’ receipt of care. Due to the abundance of veterans with tinnitus and the needs of veterans in terms of health care delivery and receipt, an interdisciplinary CBT-plus-AC protocol was created that is specific to and accepted by veterans with tinnitus.

Refinements to the VET CBT-T protocol were identified that led to development of PTM that was the subject of another small study, which then led to the authors’ 2 larger RCTs. Attempts were made to include greater attention to the mental health concerns of veterans both in terms of education and in offering sensitive delivery of the protocol. Session content was used to create an organized, visual presentation that follows an organized workbook.22,35 Refinements to the protocol are ongoing.

Acknowledgments

This material was based on work supported by US Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D): (1) R.D. Kerns’ Pilot Merit Grant #C6324P and (2) C.J. (Kendall) Schmidt’s Career Development Award-1 #D6848M. The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance from Rebecca Czlapinski, MA; Kathryn LaChappelle, MPH; and Emily Thielman, MS, for the conduct of the study, data collection and management, and preparation of this manuscript.

Chronic tinnitus is defined as nonsensical, persistent sound in the head or ears with no external sound source that persists for more than 6 months.1 It is most commonly associated with sound trauma, aging, head injury, and damage to the ear structures.2 Tinnitus affects up to 30% of military veterans, a prevalence rate that is twice that of the nonveteran population.3 It also is the most common service-connected disability for veterans.4 In 2016, more than 1.6 million veterans had service-connected tinnitus.

Clinical management of tinnitus is the purview of audiologists, although their role in providing this service is not well defined.5 Following an audiologic evaluation for hearing loss, devices such as hearing aids, ear-level sound generators, or sounds played through speakers may be prescribed. However, effectiveness of these devices has been shown only when coupled with counseling.6 Counseling provided by audiologists often includes education about tinnitus etiology, maintaining hearing health, and use of sound to manage tinnitus. Length, content of care, and follow-up services vary among audiologists.

Given the importance of counseling and the added complexities of mental health and behavioral health comorbidities (eg, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders), various psychological therapies delivered by mental health specialists for tinnitus management have been explored.7-11 In fact, only psychological therapies have been documented to be efficacious for mitigating the negative effects of tinnitus on sleep, concentration, communication, and emotions.12 Among these approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has the strongest empirical support, particularly in terms of improving quality of life (QOL) and reducing depressive symptoms.11,12 Cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus is derived from social cognitive theory (SCT) and modeled after CBT for depression, anxiety, pain, and insomnia.11,13-15

Cognitive behavioral therapy helps patients with tinnitus reconceptualize the auditory problem as manageable and encourages acquisition, practice, and use of a range of specific tinnitus coping strategies to enhance perceptions of self-control and self-efficacy. Cognitive behavioral therapy involves a number of distinct therapeutic components, and there is no consensus about the efficacious components of CBT for tinnitus. For example, use of sound and purposeful exposure to tinnitus varies among providers.16 Additional questions about CBT pertain to its clinical implementation (eg, group vs individual sessions, frequency and length of sessions, in-person sessions vs delivery via telephone or Internet).

Programs offered at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities take veteran-specific factors into account to promote optimal engagement and outcomes. Factors that differentiate veterans from civilians include (1) increased probability of low health literacy and low socioeconomic status among seniors17; (2) increased likelihood of acoustic and/or psychological trauma3,18; (3) overrepresentation of males; and (4) increased probability of mental health diagnoses.19,20 At the same time, veterans are highly diverse with respect to age, academic achievement, cultural background, medical and mental health comorbidities, and economic resources.17 In spite of this diversity, most veterans are unified by their sense of camaraderie, loyalty to country, and adherence to discipline and order.21 Peer support and other variables such as compassionate understanding of their military experiences may be especially important to consider when designing behavioral interventions for veterans.

The present phenomenologic study was motivated by the need to develop and test a veteran-specific CBT for tinnitus protocol (VET CBT-T). To examine veterans’ experiences with VET CBT-T, we designed a small pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of VET CBT-T comparing it to structured audiologist counseling (AC). A mixed quantitative and qualitative approach was employed, including assessing veterans’ acceptance of care, identifying aspects that can be modified to improve outcomes, and obtaining feasibility data to guide refinements to VET CBT-T to inform a larger RCT.

Methods

The study used a single-blind, randomized, parallel treatment (VET CBT-T vs AC) concurrent design complemented by collection of qualitative data. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00724152).

Measures

Four standardized measures were administered to potential participants. Callers were screened for eligibility by the research coordinator using Section A of the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS), which had been developed to screen candidates for tinnitus studies by phone.22 The THS contains 3 sections to identify problems related to tinnitus (Section A), hearing (Section B), and sound tolerance (Section C). Section A contains 4 items, each with a possible score of 0 to 4, which identifies tinnitus problems. Callers who were veterans and who met the necessary cutoff of 4 out of 16 possible points on Section A were invited to meet in-person with the research coordinator to obtain written informed consent and conduct a thorough assessment of eligibility.23

Three additional assessment measures were then administered sequentially to determine eligibility. The first 2 of these measures were readministered to eligible candidates who agreed to participate in the study and were used to examine outcomes:

(1) Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI): The 25-item THI provides an index score (0-100), with higher scores reflecting poorer QOL and more perceived functional limitations due to tinnitus.24 Candidates with scores of ≤ 19 were excluded.

(2) Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ): The TRQ measures perceived impact of tinnitus on QOL with emphasis on emotional consequences of tinnitus.25 Higher scores indicate more severe impact. Scores of ≥ 17 points purportedly indicate significant tinnitus disturbance. Candidates scoring < 17 were excluded.

(3) Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis, Abbreviated-Interview/Nonpatient (SCIDa-I/NP): The SCIDa-I/NP is a measure used to assess symptoms of psychopathology.26 Candidates with a lifetime history of psychosis were excluded.

Interventions

Each of the interventions was offered using 6 group sessions, with 2 or more participants, on an approximate weekly schedule.

VET CBT-T. Two primary texts served as resources for developing the VET CBT-T protocol: (1) the Psychological Management of Chronic Tinnitus: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach14; and (2) a manual for providing CBT for the treatment of chronic pain.27,28 Draft materials were developed by the clinical psychologist, including a clinician’s manual for providing VET CBT-T. Handouts were provided to each veteran. Components were compared to another unpublished CBT for tinnitus workbook.10

Key components targeted psychological difficulties including sleep disturbance, reduced functioning, low mood, nervousness, reduced pleasure from activities, and negative changes in relationships. The protocol emphasized basic information about tinnitus; relationships among tinnitus, acoustic trauma, and mental health symptoms; veterans’ sense of camaraderie and loyalty; and goal setting, making use of discipline and order veterans may desire.

To build rapport, the psychologist used reflective listening, encouraged interactive dialogue, and promoted participant understanding. Since tinnitus is thought to be exacerbated by stress, participants learned ways to manage stress and practiced relaxation exercises. Participants learned to create individualized, intersession goals that were realistic, specific, and measurable to promote self-efficacy. They also learned to list and increase pleasant activities to distract from tinnitus, improve QOL, and enable behavioral activation. Motivational interviewing addressed readiness, ambivalence, and resistance to achieving these specific goals. Participants also learned to identify and modify unhelpful thoughts about tinnitus (ie, cognitive restructuring).

Audiologist Counseling (AC). To control for patient contact in VET CBT-T, the study audiologist created a 6-session counseling protocol. The AC emphasized education about tinnitus and available tinnitus interventions. Participants were encouraged to ask questions, share their tinnitus experiences, and cope with tinnitus by avoiding silence.

Quantitative Analysis

To assess baseline between-group differences, pretreatment (t1;immediately prior to attending the first group session) administrations of the THI and TRQ were compared using t tests. Demographics between groups were compared using the chi-square test.

The THI and TRQ were readministered following completion of the last group session (t2) and about 8 weeks after the last group session (t3). Because of the small sample size, required assumptions for analyzing parametric tests of linear effects were not met. Thus, only descriptive results and mean differences in scores on the THI and TRQ between these 3 assessment periods are presented. SPSS PASW Statistics 18.0 (Hong Kong, China) was used for analyses.

Qualitative Analysis

VET CBT-T. After each VET CBT-T session, veterans’ acceptance of the protocol was assessed using 4 questions: (1) Was the information presented to you today easy to understand? Yes/No. If no, why not? (2) Were the examples (if there were any) useful? Yes/No. If no, why not? (3) Was the way the information was presented by the group leader helpful? Yes/No. If no, why not? and (4) Please tell us what you thought about today’s group. Participants were encouraged to be honest and provide detailed feedback. To facilitate unbiased responding, the group leader left the room while a research assistant collected the comments.

Participants’ experiences and acceptance of the interventions were explored using a stepwise content analysis approach.29,30First, the feedback data were prepared for analysis by entering verbatim responses into a spreadsheet. Next, these responses were reviewed by the clinical psychologist who identified themes. Examination of data involved qualitative analyses in which the phenomenon of interest was veterans’ acceptance of the interventions. This process presumed that most veterans would respond favorably to the intervention and, thus, acknowledged that the clinical psychologist designed and delivered the intervention.

Any contrary or negative comments were flagged. However, neutral and positive comments also were analyzed and tallied. Notations within each comment were used to calculate the number of occurrences of themes. Similar themes with few responses were collapsed into a single theme when appropriate. Final themes and tallies were shared with an auditor familiar with tinnitus, psychology, and qualitative methods who made comments and checked tallies within each theme. The themes were revised based on this audit and retallied. The clinical psychologist then summarized the themes in text, which was reviewed by the auditor for accuracy in capturing the important emergent themes.

Next, themes were used to examine typed verbatim transcripts from the second and fifth sessions of the intervention. Thematic content derived from the above feedback was extracted from the transcripts by the clinical psychologist. Then the study audiologist read the transcripts to confirm or reject these comments as relevant to the themes. Additional comments were nominated by the study audiologist and reviewed by the clinical psychologist who finalized feedback thought to best represent the themes.

Results

One hundred ninety-six persons inquired about the study (Figure 1).

After being deemed eligible by the otologist as having tinnitus associated with sound trauma, the remaining 25 eligible and interested candidates were randomized into the 2 treatment arms. To reduce attrition, formation of groups took into account participants’ preferred appointment days and times. When 3 or more participants were allocated to a treatment arm, group sessions were scheduled. Five (20%) participants were lost to attrition, including 1 randomized to VET CBT-T and 2 to AC who dropped out prior to receiving any intervention, and 2 randomized to VET CBT-T who dropped out after attending 1 session. Reasons stated for dropping out included concerns they would not learn new information, inability to tolerate sound in a group, unexpected moves out of the area, lack of time, loss of interest, and family emergencies.

Quantitative Analysis

Participants in the 2 treatment arms did not differ significantly on the pretreatment (t1) THI (t = 1.39, df = 18, P = .18) or TRQ (t = 0.99, df = 18, P = .33) scores. Differences in THI scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 6.2; ACt1−t2 = 10.0) and from pretreatment to 8-week follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 4.4; ACt1−t3 = 9.1). Similarly, differences in mean TRQ index scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 5.3; ACt1−t2 = 7.6) and from pretreatment to 8 weeks follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 1.5; ACt1−t3 = 5.6). These mean differences reveal consistent reductions in mean index scores (improved tinnitus-related QOL) between time points for each treatment arm, but do not indicate statistically or clinically significant reductions of distress.

Qualitative Analysis

The 89 comments that participants provided after the 18 VET CBT-T sessions (3 series of 6 sessions each) were mostly positive (67 responses, 75%) (eTable 2).

Components of VET CBT-T and Number of Sessions (n = 53)

Psychoeducation and Sound Enrichment. Participants generally appreciated the psychoeducation component of VET CBT-T, including basic information about the prevalence of tinnitus, mechanics of the ear and hearing, and how an enriched sound environment may assist with coping (5 comments).

Stress Reduction. Two of the 14 participants who commented on the stress reduction session (via relaxation exercises) noted that it was helpful in their lives overall but “had no effect on tinnitus.”

Goal Setting. Nine participants noted that they valued the goal-setting strategies and long-term relapse planning, one writing that he was “…glad to be encouraged to document and set specific, documented goals each week.”

Cognitive Restructuring and Acceptance. Participants reported that the cognitive restructuring session was important for “accepting” their tinnitus (9 comments). Overall cognitive restructuring appeared to be well received by participants as a concept when learning ways to cope with tinnitus.

Distraction. Of the 8 comments that regarded the increasing-pleasant-activities session, 1 participant reported that the pleasant activities worksheet had a female bias and that activities on one of the worksheets “were not helpful and overlapped too much.” A participant suggested that group leaders allow participants to brainstorm pleasant activities using an open-ended format instead of using categories of pleasant activities. Participants generally found the increasing-pleasant-activities component very beneficial for managing tinnitus.

Self-Hypnosis and Exposure Therapy. Two components not presented during VET CBT-T were identified by participants as potentially desirable. One participant suggested providing information on self-hypnosis and another stated that he focuses on his tinnitus to cope, much like exposure therapy for tinnitus.

Number of Sessions. One participant wrote after the last (sixth) session that he was “glad it’s over” possibly suggesting the intervention was too long. Another participant stated at the fifth session, “I basically want to get out of here—out of this, out of these meetings.” Conversely a participant stated, “I was kind of hoping there was one more after next week.” Another participant explained the intervention itself can be in conflict with its own stated goals of attending less to tinnitus.

Leader, Materials, and Presentations (n = 16).

Overall, the participants had positive experiences (15 comments) with their study therapist. They noted that the group leader was “flexible” and “did a great job of facilitating discussion.” One participant commented on the need for better visual presentations of the information and the need for the group leader to “use her own words” rather than reading the content.

Previous Use of CBT Skills (n = 5).

Five participants noted that information presented was “not new” and that they had acquired the coping skills spontaneously years earlier. Two expressed relief that some of the ways they had been dealing with their tinnitus prior to the intervention were actually recommended. One discussed that reviewing skills that he had already implemented was helpful.

Hope, Anger, and Mental Health (n = 8).

Three participants indicated the intervention gave them “hope” that they will learn ways to cope with tinnitus. One noted that the discussion regarding depression as a commonly co-occurring condition with tinnitus should include a better description of depressive symptoms. Two expressed relief to receive help for their frustration and anger resulting from tinnitus, and 1 participant discussed the added frustration of hearing loss with tinnitus. Excessive alcohol use to cope with tinnitus and the comorbidity of tinnitus and PTSD also were discussed.

Group Cohesiveness (n = 8)/Discord (n = 2).

Many group members commented that they enjoyed listening to information about tinnitus and sharing their experiences. There was friendly interaction and discussion among most of the participants. They commented that it was informative to see that others were coming forward for help and were interested to hear others’ experiences. The group format was mostly welcomed and appreciated. However, group discord occurred when topics other than tinnitus were shared, such as recovery from substance abuse. Two feedback comments indicated that this discussion was unwelcomed.

Discussion