User login

A 25-year-old male was found wandering naked in his room with the shower running after failing to come to work on a Monday morning. When found, he was able to talk and follow some commands but was confused about what was happening. He had experienced a right periorbital headache with nausea and vomiting for several days before admission. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head at an outside hospital was negative.

Related: Pain, Anxiety, and Dementia: A Catastrophic Outcome

The patient had no history of tick or insect bites, skin rash, chest pain, shortness of breath, trauma, or illicit drug or alcohol use. He smoked a half pack of cigarettes per day. The patient had spent time in the military in the Middle East and North Africa 3 years earlier and had 3 tattoos. Over the past few months, he had been noted to be more aggressive, including having gotten into a bar fight. His past medical history was significant only for documented hearing loss in the right ear per reports from the air base.

On examination, the patient’s temperature was 97.3°F, heart rate 47 bpm, respirations 20 breathes/min, and blood pressure 97/60 mm Hg. His neck was supple, and the remainder of the general examination was normal. The neurologic examination revealed the patient to be awake and alert but apathetic, irritable, and refusing to talk after a few minutes. He was slow to respond, spoke loudly, and had a poor attention span. The patient was disoriented to time and place and remembered 0/5 objects at 5 minutes.

Blood tests revealed 12,500/μL white blood cell (WBC) count (increased mononuclear cells, 13.7%); hemoglobin, 14.6 g/dL; platelet count 194,000/μL; and hematocrit, 43.6%. Electrolytes, general chemistries, vitamin B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, copper, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and urinalysis were all normal. The CT head scan was normal, and the urine drug screen and alcohol levels were negative.

The initial audiologic evaluation revealed absent acoustic reflexes bilaterally at 500 Hz, 1 KHz, 2 KHz, and 4 KHz. The brain stem auditory evoked potentials showed no replicable waveforms from the right ear and a wave I present in the left ear with no other replicable waveforms.

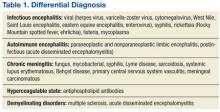

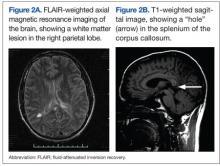

A very broad differential diagnosis was considered at this point (Table 1). Lumbar puncture was performed with an opening pressure of 17.5 cm H2O. There were 10 WBC/μL with 12% segmented polymorphonuclear cells and 83% lymphocytes, 30 red blood cells/μL, glucose of 71 mg/dL, and protein of 221 mg/dL. The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory Test was nonreactive; cryptococcal antigen, acid-fast stain, and bacterial and fungal cultures were negative. The electroencephalogram (EEG) showed mild diffuse slowing with frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was significant for leptomeningeal and pachymeningeal enhancement with a small area of restricted diffusion in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Figure 1). Other cerebral spinal fluid and serum studies were negative or nonreactive (Table 2).

The patient completed a 2-week course of ceftriaxone 1 gram q 12 hours, vancomycin 1,000 mg q 12 hours, acyclovir 700 mg q 8 hours, and doxycycline 100 mg bid without any notable clinical change. A repeat lumbar puncture was acellular and had a protein of 254 mg/dL.

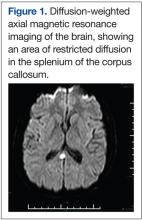

Two days later he worsened, becoming more withdrawn, unable to speak, irritable, and unwilling to be examined. He refused to get out of bed even with his family members present. A repeat MRI at this time showed continued meningeal enhancement, enlargement of the previously seen corpus callosal lesion, a new white matter lesion in the right parietal region, and a dark hole in the corpus callosum on the sagittal T1 image (Figures 2A and 2B). Audiometric testing showed profound hearing loss at low and high frequencies, with severe loss at middle frequencies in both ears.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Diagnosis

At this point, a diagnosis must explain encephalitis/encephalopathy, hearing loss, and MRI findings of meningeal enhancement and lesions in the corpus callosum and right parietal white matter. The main differential at this point included acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), multiple sclerosis (MS), infection, and vasculitis/vasculopathy (especially primary central nervous system vasculitis). Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis usually has large, asymmetric lesions in the subcortical white matter and gray white junction, with corpus callosal lesions being unusual. Meningeal enhancement is very rare, and hearing loss would be unusual as well.1

Encephalopathy would be unusual in MS and if seen is usually associated with large confluent lesions (the Marburg variant). Meningeal enhancement would be rare on MRI, and the location of the corpus callosal lesion as shown on the T1- sagittal MRI would be atypical for both MS and ADEM (Figure 2B). Hearing loss has been described in MS, with a 4% to 5% incidence, often as the first manifestation and usually with full recovery.2 With the extensive evaluation and treatment in this case, infection was unlikely at this point. Primary central nervous system vasculitis remained a definite possibility and could explain most of the findings. However, there have been no reports of hearing loss or corpus callosal lesions in the literature with this latter condition.

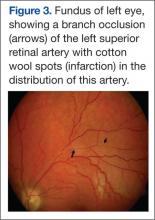

The presence of encephalopathy and hearing loss, in addition to the location of the corpus callosal lesion as demonstrated on the sagittal T1-weighted MRI (Figure 2B) suggested the need for an ophthalmologic consult with dilated retinoscopy and fluorescein angiography (Figure 3). A retinal examination showed branch retinal artery occlusions with cotton wool spots (infarctions). Fluorescein angiography showed branch retinal artery occlusions and arteriolar wall hyperfluoresence in one area. This demonstrated the final feature of the triad of encephalopathy, hearing loss, and branch retinal artery occlusions, confirming the diagnosis of Susac syndrome (SS).

Discussion and Literature Review

The patient was treated with a 3-day course of IV methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days, followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily for 1 week, followed by a slow taper thereafter. Both his cognition and behavior improved by the second day of treatment, and this continued during his hospital stay. After a short stay in the rehabilitation unit, he was transferred to a facility closer to his home. Mental status improved almost to baseline, but he got minimal if any improvement in his hearing function. Despite the branch retinal occlusions, he had no noticeable deficit in his visual function.

John O. Susac, MD, first described 2 women with a triad of encephalopathy, hearing loss, and branch retinal artery occlusions as a syndrome that subsequently was named after him.3 The syndrome most frequently affects women aged 20 to 40 years. Headaches consistent with migraines occur at onset in a majority of patients.4 Encephalopathy may be acute or subacute and mild to severe. Symptoms can include mood changes, personality change, bizarre behavior, hallucinations, memory and cognitive difficulties, ataxia, seizures, corticospinal tract signs, and myoclonus.5,6 The retinopathy may cause scintillating scotomata or segmental loss of vision but may also be asymptomatic due to occlusions in very distal, branch arteries. Hearing loss may be acute and severe or insidious and mild. Audiometry shows low-to-mid frequency hearing loss.

Related: Infliximab-Induced Complications

Hearing loss is usually permanent and, if severe, may require a cochlear implant.7 The disease course is variable and unpredictable. It may be monophasic, lasting under 2 years. This is often the case if encephalopathy occurs in the first 2 years. Susac syndrome can also have a polycyclic course, with remissions lasting up to 18 years. A chronic continuous course has also been described.8 All 3 components of the triad are not always present, and those without encephalopathy are more likely to have a polycyclic or chronic continuous course. The differential diagnosis is broad, as in the present case.

A cerebral spinal fluid evaluation often shows an elevated protein of 100 to 3,000 mg/dL, a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (5-30 cells/mm), and oligoclonal bands may be present. Antiendothelial antibodies are present in the serum but not specific (also seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and juvenile dermatomyositis).8 The EEG usually shows diffuse slowing. The MRI is almost always abnormal, and studies have shown virtually 100% have corpus callosal lesions. These occur in the central region of the corpus callosum, consistent with infarction. Demyelinating lesions, with MS or ADEM, on the other hand, tend to occur on the inferior surface of the corpus callosum. If SS is suspected, a sagittal fluid- attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI should be obtained to look for these changes. About one-third or more of MRIs show leptomeningeal enhancement, and other lesions can be found scattered throughout the white matter, cerebellum, brain stem, and gray matter.9

Because relatively few cases have been described, SS etiology remains obscure at this time. The disease has an affinity for small precapillary arterioles, of > 100 μm in diameter. The pathology shows necrosis and inflammatory changes of the endothelial cells, making them the primary site of the immune attack. This immune-mediated injury leads to narrowing and occlusion of the microvasculature, with resulting ischemia of the brain, retina, and cochlea. This pathology is very similar to that of juvenile dermatomyositis, which involves muscle, skin, and the gastrointestinal tract.10

Treatment approaches are based on treatments for juvenile dermatomyositis. It is suggested that the patient be given pulse methylprednisolone therapy of 1 g per day for 3 days followed by prednisone 60 mg to 80 mg per day for 4 weeks. Newer recommendations suggest giving IV immunoglobulin in the first week as well, followed by additional courses every month for 6 months. Cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil should be considered for long-term treatment with consideration of etanercept, cyclosporine, or rituximab in those who fail to respond.10 Aggressive treatment is suggested, because this is a self-limiting disorder, but the deficits tend to be permanent.

Related: Rituximab and Primary Sjögren Syndrome

This patient was atypical, because SS primarily affects young females. Review of the literature indicates that men account for about 25% of patients.8 The presentation, however, was not unusual and demonstrated the difficulty in making this diagnosis. In this patient with encephalopathy, the unusual feature was hearing loss, but it must be kept in mind that both hearing loss and visual changes can be difficult to identify in a confused patient. Brain stem auditory evoked potentials may be helpful in investigating hearing loss in noncooperative patients. An MRI may show centrally located corpus callosal lesions. If SS is suspected, sagittal FLAIR images, which often are not routinely done, should be obtained.

The most helpful evaluation is a dilated direct retinoscopy, which will usually show the branch retinal artery occlusions, and if not, fluorescein angiography will usually show a change. The presence of Gass plaques, yellow-white retinal arterial wall plaques from lipid deposition into the damaged arterial wall, with hyperfluoresence on fluorescein angiography is considered pathognomonic of SS.8 Establishing the diagnosis of SS as soon as possible is critical, because early treatment may lessen the degree of permanent disability.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Eckstein C, Saidha S, Levy M. A differential diagnosis of central nervous system demyelination: beyond multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2012;259(5):801-816.

2. Hellmann MA, Steiner I, Mosberg-Galili R. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss in multiple sclerosis: clinical course and possible pathogenesis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(4):245-249.

3. Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979;29(3):313-316.

4. Papo T, Biousse V, Lehoang P, et al. Susac syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77(1):3-11.

5. Susac JO. Susac’s syndrome: the triad of microangiopathy of the brain and retina with hearing loss in young women. Neurology. 1994;44(4):591-593.

6. Hahn JS, Lannin WC, Sarwal MM. Microangiopathy of brain, retina, and inner ear (Susac’s syndrome) in an adolescent female presenting as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):276-281.

7. Roeser MM, Driscoll CL, Shallop JK, Gifford RH, Kasperbauer JL, Gluth MB. Susac syndrome—a report of cochlear implantation and review of otologic manifestations in twenty-three patients. Otol Neurotol. 2009;30(1):34-40.

8. Bitra RK, Eggenberger E. Review of Susac syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(6):472-476.

9. Susac JO, Murtagh FR, Egan RA, et al. MRI findings in Susac’s syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61(12): 1783-1787.

10. Rennebohm RM, Susac JO. Treatment of Susac’s syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257(1-2):215-220.

A 25-year-old male was found wandering naked in his room with the shower running after failing to come to work on a Monday morning. When found, he was able to talk and follow some commands but was confused about what was happening. He had experienced a right periorbital headache with nausea and vomiting for several days before admission. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head at an outside hospital was negative.

Related: Pain, Anxiety, and Dementia: A Catastrophic Outcome

The patient had no history of tick or insect bites, skin rash, chest pain, shortness of breath, trauma, or illicit drug or alcohol use. He smoked a half pack of cigarettes per day. The patient had spent time in the military in the Middle East and North Africa 3 years earlier and had 3 tattoos. Over the past few months, he had been noted to be more aggressive, including having gotten into a bar fight. His past medical history was significant only for documented hearing loss in the right ear per reports from the air base.

On examination, the patient’s temperature was 97.3°F, heart rate 47 bpm, respirations 20 breathes/min, and blood pressure 97/60 mm Hg. His neck was supple, and the remainder of the general examination was normal. The neurologic examination revealed the patient to be awake and alert but apathetic, irritable, and refusing to talk after a few minutes. He was slow to respond, spoke loudly, and had a poor attention span. The patient was disoriented to time and place and remembered 0/5 objects at 5 minutes.

Blood tests revealed 12,500/μL white blood cell (WBC) count (increased mononuclear cells, 13.7%); hemoglobin, 14.6 g/dL; platelet count 194,000/μL; and hematocrit, 43.6%. Electrolytes, general chemistries, vitamin B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, copper, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and urinalysis were all normal. The CT head scan was normal, and the urine drug screen and alcohol levels were negative.

The initial audiologic evaluation revealed absent acoustic reflexes bilaterally at 500 Hz, 1 KHz, 2 KHz, and 4 KHz. The brain stem auditory evoked potentials showed no replicable waveforms from the right ear and a wave I present in the left ear with no other replicable waveforms.

A very broad differential diagnosis was considered at this point (Table 1). Lumbar puncture was performed with an opening pressure of 17.5 cm H2O. There were 10 WBC/μL with 12% segmented polymorphonuclear cells and 83% lymphocytes, 30 red blood cells/μL, glucose of 71 mg/dL, and protein of 221 mg/dL. The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory Test was nonreactive; cryptococcal antigen, acid-fast stain, and bacterial and fungal cultures were negative. The electroencephalogram (EEG) showed mild diffuse slowing with frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was significant for leptomeningeal and pachymeningeal enhancement with a small area of restricted diffusion in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Figure 1). Other cerebral spinal fluid and serum studies were negative or nonreactive (Table 2).

The patient completed a 2-week course of ceftriaxone 1 gram q 12 hours, vancomycin 1,000 mg q 12 hours, acyclovir 700 mg q 8 hours, and doxycycline 100 mg bid without any notable clinical change. A repeat lumbar puncture was acellular and had a protein of 254 mg/dL.

Two days later he worsened, becoming more withdrawn, unable to speak, irritable, and unwilling to be examined. He refused to get out of bed even with his family members present. A repeat MRI at this time showed continued meningeal enhancement, enlargement of the previously seen corpus callosal lesion, a new white matter lesion in the right parietal region, and a dark hole in the corpus callosum on the sagittal T1 image (Figures 2A and 2B). Audiometric testing showed profound hearing loss at low and high frequencies, with severe loss at middle frequencies in both ears.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Diagnosis

At this point, a diagnosis must explain encephalitis/encephalopathy, hearing loss, and MRI findings of meningeal enhancement and lesions in the corpus callosum and right parietal white matter. The main differential at this point included acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), multiple sclerosis (MS), infection, and vasculitis/vasculopathy (especially primary central nervous system vasculitis). Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis usually has large, asymmetric lesions in the subcortical white matter and gray white junction, with corpus callosal lesions being unusual. Meningeal enhancement is very rare, and hearing loss would be unusual as well.1

Encephalopathy would be unusual in MS and if seen is usually associated with large confluent lesions (the Marburg variant). Meningeal enhancement would be rare on MRI, and the location of the corpus callosal lesion as shown on the T1- sagittal MRI would be atypical for both MS and ADEM (Figure 2B). Hearing loss has been described in MS, with a 4% to 5% incidence, often as the first manifestation and usually with full recovery.2 With the extensive evaluation and treatment in this case, infection was unlikely at this point. Primary central nervous system vasculitis remained a definite possibility and could explain most of the findings. However, there have been no reports of hearing loss or corpus callosal lesions in the literature with this latter condition.

The presence of encephalopathy and hearing loss, in addition to the location of the corpus callosal lesion as demonstrated on the sagittal T1-weighted MRI (Figure 2B) suggested the need for an ophthalmologic consult with dilated retinoscopy and fluorescein angiography (Figure 3). A retinal examination showed branch retinal artery occlusions with cotton wool spots (infarctions). Fluorescein angiography showed branch retinal artery occlusions and arteriolar wall hyperfluoresence in one area. This demonstrated the final feature of the triad of encephalopathy, hearing loss, and branch retinal artery occlusions, confirming the diagnosis of Susac syndrome (SS).

Discussion and Literature Review

The patient was treated with a 3-day course of IV methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days, followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily for 1 week, followed by a slow taper thereafter. Both his cognition and behavior improved by the second day of treatment, and this continued during his hospital stay. After a short stay in the rehabilitation unit, he was transferred to a facility closer to his home. Mental status improved almost to baseline, but he got minimal if any improvement in his hearing function. Despite the branch retinal occlusions, he had no noticeable deficit in his visual function.

John O. Susac, MD, first described 2 women with a triad of encephalopathy, hearing loss, and branch retinal artery occlusions as a syndrome that subsequently was named after him.3 The syndrome most frequently affects women aged 20 to 40 years. Headaches consistent with migraines occur at onset in a majority of patients.4 Encephalopathy may be acute or subacute and mild to severe. Symptoms can include mood changes, personality change, bizarre behavior, hallucinations, memory and cognitive difficulties, ataxia, seizures, corticospinal tract signs, and myoclonus.5,6 The retinopathy may cause scintillating scotomata or segmental loss of vision but may also be asymptomatic due to occlusions in very distal, branch arteries. Hearing loss may be acute and severe or insidious and mild. Audiometry shows low-to-mid frequency hearing loss.

Related: Infliximab-Induced Complications

Hearing loss is usually permanent and, if severe, may require a cochlear implant.7 The disease course is variable and unpredictable. It may be monophasic, lasting under 2 years. This is often the case if encephalopathy occurs in the first 2 years. Susac syndrome can also have a polycyclic course, with remissions lasting up to 18 years. A chronic continuous course has also been described.8 All 3 components of the triad are not always present, and those without encephalopathy are more likely to have a polycyclic or chronic continuous course. The differential diagnosis is broad, as in the present case.

A cerebral spinal fluid evaluation often shows an elevated protein of 100 to 3,000 mg/dL, a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (5-30 cells/mm), and oligoclonal bands may be present. Antiendothelial antibodies are present in the serum but not specific (also seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and juvenile dermatomyositis).8 The EEG usually shows diffuse slowing. The MRI is almost always abnormal, and studies have shown virtually 100% have corpus callosal lesions. These occur in the central region of the corpus callosum, consistent with infarction. Demyelinating lesions, with MS or ADEM, on the other hand, tend to occur on the inferior surface of the corpus callosum. If SS is suspected, a sagittal fluid- attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI should be obtained to look for these changes. About one-third or more of MRIs show leptomeningeal enhancement, and other lesions can be found scattered throughout the white matter, cerebellum, brain stem, and gray matter.9

Because relatively few cases have been described, SS etiology remains obscure at this time. The disease has an affinity for small precapillary arterioles, of > 100 μm in diameter. The pathology shows necrosis and inflammatory changes of the endothelial cells, making them the primary site of the immune attack. This immune-mediated injury leads to narrowing and occlusion of the microvasculature, with resulting ischemia of the brain, retina, and cochlea. This pathology is very similar to that of juvenile dermatomyositis, which involves muscle, skin, and the gastrointestinal tract.10

Treatment approaches are based on treatments for juvenile dermatomyositis. It is suggested that the patient be given pulse methylprednisolone therapy of 1 g per day for 3 days followed by prednisone 60 mg to 80 mg per day for 4 weeks. Newer recommendations suggest giving IV immunoglobulin in the first week as well, followed by additional courses every month for 6 months. Cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil should be considered for long-term treatment with consideration of etanercept, cyclosporine, or rituximab in those who fail to respond.10 Aggressive treatment is suggested, because this is a self-limiting disorder, but the deficits tend to be permanent.

Related: Rituximab and Primary Sjögren Syndrome

This patient was atypical, because SS primarily affects young females. Review of the literature indicates that men account for about 25% of patients.8 The presentation, however, was not unusual and demonstrated the difficulty in making this diagnosis. In this patient with encephalopathy, the unusual feature was hearing loss, but it must be kept in mind that both hearing loss and visual changes can be difficult to identify in a confused patient. Brain stem auditory evoked potentials may be helpful in investigating hearing loss in noncooperative patients. An MRI may show centrally located corpus callosal lesions. If SS is suspected, sagittal FLAIR images, which often are not routinely done, should be obtained.

The most helpful evaluation is a dilated direct retinoscopy, which will usually show the branch retinal artery occlusions, and if not, fluorescein angiography will usually show a change. The presence of Gass plaques, yellow-white retinal arterial wall plaques from lipid deposition into the damaged arterial wall, with hyperfluoresence on fluorescein angiography is considered pathognomonic of SS.8 Establishing the diagnosis of SS as soon as possible is critical, because early treatment may lessen the degree of permanent disability.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

A 25-year-old male was found wandering naked in his room with the shower running after failing to come to work on a Monday morning. When found, he was able to talk and follow some commands but was confused about what was happening. He had experienced a right periorbital headache with nausea and vomiting for several days before admission. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head at an outside hospital was negative.

Related: Pain, Anxiety, and Dementia: A Catastrophic Outcome

The patient had no history of tick or insect bites, skin rash, chest pain, shortness of breath, trauma, or illicit drug or alcohol use. He smoked a half pack of cigarettes per day. The patient had spent time in the military in the Middle East and North Africa 3 years earlier and had 3 tattoos. Over the past few months, he had been noted to be more aggressive, including having gotten into a bar fight. His past medical history was significant only for documented hearing loss in the right ear per reports from the air base.

On examination, the patient’s temperature was 97.3°F, heart rate 47 bpm, respirations 20 breathes/min, and blood pressure 97/60 mm Hg. His neck was supple, and the remainder of the general examination was normal. The neurologic examination revealed the patient to be awake and alert but apathetic, irritable, and refusing to talk after a few minutes. He was slow to respond, spoke loudly, and had a poor attention span. The patient was disoriented to time and place and remembered 0/5 objects at 5 minutes.

Blood tests revealed 12,500/μL white blood cell (WBC) count (increased mononuclear cells, 13.7%); hemoglobin, 14.6 g/dL; platelet count 194,000/μL; and hematocrit, 43.6%. Electrolytes, general chemistries, vitamin B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, copper, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and urinalysis were all normal. The CT head scan was normal, and the urine drug screen and alcohol levels were negative.

The initial audiologic evaluation revealed absent acoustic reflexes bilaterally at 500 Hz, 1 KHz, 2 KHz, and 4 KHz. The brain stem auditory evoked potentials showed no replicable waveforms from the right ear and a wave I present in the left ear with no other replicable waveforms.

A very broad differential diagnosis was considered at this point (Table 1). Lumbar puncture was performed with an opening pressure of 17.5 cm H2O. There were 10 WBC/μL with 12% segmented polymorphonuclear cells and 83% lymphocytes, 30 red blood cells/μL, glucose of 71 mg/dL, and protein of 221 mg/dL. The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory Test was nonreactive; cryptococcal antigen, acid-fast stain, and bacterial and fungal cultures were negative. The electroencephalogram (EEG) showed mild diffuse slowing with frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was significant for leptomeningeal and pachymeningeal enhancement with a small area of restricted diffusion in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Figure 1). Other cerebral spinal fluid and serum studies were negative or nonreactive (Table 2).

The patient completed a 2-week course of ceftriaxone 1 gram q 12 hours, vancomycin 1,000 mg q 12 hours, acyclovir 700 mg q 8 hours, and doxycycline 100 mg bid without any notable clinical change. A repeat lumbar puncture was acellular and had a protein of 254 mg/dL.

Two days later he worsened, becoming more withdrawn, unable to speak, irritable, and unwilling to be examined. He refused to get out of bed even with his family members present. A repeat MRI at this time showed continued meningeal enhancement, enlargement of the previously seen corpus callosal lesion, a new white matter lesion in the right parietal region, and a dark hole in the corpus callosum on the sagittal T1 image (Figures 2A and 2B). Audiometric testing showed profound hearing loss at low and high frequencies, with severe loss at middle frequencies in both ears.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Diagnosis

At this point, a diagnosis must explain encephalitis/encephalopathy, hearing loss, and MRI findings of meningeal enhancement and lesions in the corpus callosum and right parietal white matter. The main differential at this point included acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), multiple sclerosis (MS), infection, and vasculitis/vasculopathy (especially primary central nervous system vasculitis). Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis usually has large, asymmetric lesions in the subcortical white matter and gray white junction, with corpus callosal lesions being unusual. Meningeal enhancement is very rare, and hearing loss would be unusual as well.1

Encephalopathy would be unusual in MS and if seen is usually associated with large confluent lesions (the Marburg variant). Meningeal enhancement would be rare on MRI, and the location of the corpus callosal lesion as shown on the T1- sagittal MRI would be atypical for both MS and ADEM (Figure 2B). Hearing loss has been described in MS, with a 4% to 5% incidence, often as the first manifestation and usually with full recovery.2 With the extensive evaluation and treatment in this case, infection was unlikely at this point. Primary central nervous system vasculitis remained a definite possibility and could explain most of the findings. However, there have been no reports of hearing loss or corpus callosal lesions in the literature with this latter condition.

The presence of encephalopathy and hearing loss, in addition to the location of the corpus callosal lesion as demonstrated on the sagittal T1-weighted MRI (Figure 2B) suggested the need for an ophthalmologic consult with dilated retinoscopy and fluorescein angiography (Figure 3). A retinal examination showed branch retinal artery occlusions with cotton wool spots (infarctions). Fluorescein angiography showed branch retinal artery occlusions and arteriolar wall hyperfluoresence in one area. This demonstrated the final feature of the triad of encephalopathy, hearing loss, and branch retinal artery occlusions, confirming the diagnosis of Susac syndrome (SS).

Discussion and Literature Review

The patient was treated with a 3-day course of IV methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days, followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily for 1 week, followed by a slow taper thereafter. Both his cognition and behavior improved by the second day of treatment, and this continued during his hospital stay. After a short stay in the rehabilitation unit, he was transferred to a facility closer to his home. Mental status improved almost to baseline, but he got minimal if any improvement in his hearing function. Despite the branch retinal occlusions, he had no noticeable deficit in his visual function.

John O. Susac, MD, first described 2 women with a triad of encephalopathy, hearing loss, and branch retinal artery occlusions as a syndrome that subsequently was named after him.3 The syndrome most frequently affects women aged 20 to 40 years. Headaches consistent with migraines occur at onset in a majority of patients.4 Encephalopathy may be acute or subacute and mild to severe. Symptoms can include mood changes, personality change, bizarre behavior, hallucinations, memory and cognitive difficulties, ataxia, seizures, corticospinal tract signs, and myoclonus.5,6 The retinopathy may cause scintillating scotomata or segmental loss of vision but may also be asymptomatic due to occlusions in very distal, branch arteries. Hearing loss may be acute and severe or insidious and mild. Audiometry shows low-to-mid frequency hearing loss.

Related: Infliximab-Induced Complications

Hearing loss is usually permanent and, if severe, may require a cochlear implant.7 The disease course is variable and unpredictable. It may be monophasic, lasting under 2 years. This is often the case if encephalopathy occurs in the first 2 years. Susac syndrome can also have a polycyclic course, with remissions lasting up to 18 years. A chronic continuous course has also been described.8 All 3 components of the triad are not always present, and those without encephalopathy are more likely to have a polycyclic or chronic continuous course. The differential diagnosis is broad, as in the present case.

A cerebral spinal fluid evaluation often shows an elevated protein of 100 to 3,000 mg/dL, a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (5-30 cells/mm), and oligoclonal bands may be present. Antiendothelial antibodies are present in the serum but not specific (also seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and juvenile dermatomyositis).8 The EEG usually shows diffuse slowing. The MRI is almost always abnormal, and studies have shown virtually 100% have corpus callosal lesions. These occur in the central region of the corpus callosum, consistent with infarction. Demyelinating lesions, with MS or ADEM, on the other hand, tend to occur on the inferior surface of the corpus callosum. If SS is suspected, a sagittal fluid- attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI should be obtained to look for these changes. About one-third or more of MRIs show leptomeningeal enhancement, and other lesions can be found scattered throughout the white matter, cerebellum, brain stem, and gray matter.9

Because relatively few cases have been described, SS etiology remains obscure at this time. The disease has an affinity for small precapillary arterioles, of > 100 μm in diameter. The pathology shows necrosis and inflammatory changes of the endothelial cells, making them the primary site of the immune attack. This immune-mediated injury leads to narrowing and occlusion of the microvasculature, with resulting ischemia of the brain, retina, and cochlea. This pathology is very similar to that of juvenile dermatomyositis, which involves muscle, skin, and the gastrointestinal tract.10

Treatment approaches are based on treatments for juvenile dermatomyositis. It is suggested that the patient be given pulse methylprednisolone therapy of 1 g per day for 3 days followed by prednisone 60 mg to 80 mg per day for 4 weeks. Newer recommendations suggest giving IV immunoglobulin in the first week as well, followed by additional courses every month for 6 months. Cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil should be considered for long-term treatment with consideration of etanercept, cyclosporine, or rituximab in those who fail to respond.10 Aggressive treatment is suggested, because this is a self-limiting disorder, but the deficits tend to be permanent.

Related: Rituximab and Primary Sjögren Syndrome

This patient was atypical, because SS primarily affects young females. Review of the literature indicates that men account for about 25% of patients.8 The presentation, however, was not unusual and demonstrated the difficulty in making this diagnosis. In this patient with encephalopathy, the unusual feature was hearing loss, but it must be kept in mind that both hearing loss and visual changes can be difficult to identify in a confused patient. Brain stem auditory evoked potentials may be helpful in investigating hearing loss in noncooperative patients. An MRI may show centrally located corpus callosal lesions. If SS is suspected, sagittal FLAIR images, which often are not routinely done, should be obtained.

The most helpful evaluation is a dilated direct retinoscopy, which will usually show the branch retinal artery occlusions, and if not, fluorescein angiography will usually show a change. The presence of Gass plaques, yellow-white retinal arterial wall plaques from lipid deposition into the damaged arterial wall, with hyperfluoresence on fluorescein angiography is considered pathognomonic of SS.8 Establishing the diagnosis of SS as soon as possible is critical, because early treatment may lessen the degree of permanent disability.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Eckstein C, Saidha S, Levy M. A differential diagnosis of central nervous system demyelination: beyond multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2012;259(5):801-816.

2. Hellmann MA, Steiner I, Mosberg-Galili R. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss in multiple sclerosis: clinical course and possible pathogenesis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(4):245-249.

3. Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979;29(3):313-316.

4. Papo T, Biousse V, Lehoang P, et al. Susac syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77(1):3-11.

5. Susac JO. Susac’s syndrome: the triad of microangiopathy of the brain and retina with hearing loss in young women. Neurology. 1994;44(4):591-593.

6. Hahn JS, Lannin WC, Sarwal MM. Microangiopathy of brain, retina, and inner ear (Susac’s syndrome) in an adolescent female presenting as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):276-281.

7. Roeser MM, Driscoll CL, Shallop JK, Gifford RH, Kasperbauer JL, Gluth MB. Susac syndrome—a report of cochlear implantation and review of otologic manifestations in twenty-three patients. Otol Neurotol. 2009;30(1):34-40.

8. Bitra RK, Eggenberger E. Review of Susac syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(6):472-476.

9. Susac JO, Murtagh FR, Egan RA, et al. MRI findings in Susac’s syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61(12): 1783-1787.

10. Rennebohm RM, Susac JO. Treatment of Susac’s syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257(1-2):215-220.

1. Eckstein C, Saidha S, Levy M. A differential diagnosis of central nervous system demyelination: beyond multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2012;259(5):801-816.

2. Hellmann MA, Steiner I, Mosberg-Galili R. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss in multiple sclerosis: clinical course and possible pathogenesis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(4):245-249.

3. Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979;29(3):313-316.

4. Papo T, Biousse V, Lehoang P, et al. Susac syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77(1):3-11.

5. Susac JO. Susac’s syndrome: the triad of microangiopathy of the brain and retina with hearing loss in young women. Neurology. 1994;44(4):591-593.

6. Hahn JS, Lannin WC, Sarwal MM. Microangiopathy of brain, retina, and inner ear (Susac’s syndrome) in an adolescent female presenting as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):276-281.

7. Roeser MM, Driscoll CL, Shallop JK, Gifford RH, Kasperbauer JL, Gluth MB. Susac syndrome—a report of cochlear implantation and review of otologic manifestations in twenty-three patients. Otol Neurotol. 2009;30(1):34-40.

8. Bitra RK, Eggenberger E. Review of Susac syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(6):472-476.

9. Susac JO, Murtagh FR, Egan RA, et al. MRI findings in Susac’s syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61(12): 1783-1787.

10. Rennebohm RM, Susac JO. Treatment of Susac’s syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257(1-2):215-220.