User login

Addressing the Needs of Patients With Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is a common health care problem that remains a significant burden for the VHA.1,2 Some reports indicate that nearly 50% of VA patients report chronic pain.3,4 Both within and outside the VHA, primary care providers (PCPs) generally manage patients with chronic pain.5,6 Historically, a biomedical approach to chronic pain also included the use of opioid medications, which may have contributed to increased opioid-related morbidity and mortality especially among the veteran patient population.7-9 The use of opioids also is controversial due to concerns about adverse effects (AEs), long-term efficacy, functional outcomes, and the potential for drug abuse and addiction.10 Consequently, alternative treatment options that incorporate an interdisciplinary approach have gained significant interest among pain care providers.11 Interdisciplinary programs have been shown to improve functional status and psychological well-being and to reduce pain severity and opioid use.12-14 These benefits may persist for a decade or longer.15

Background

The Stepped Care Model for Pain Management (SCM-PM) is a specific pain treatment approach promoted by the VA National Pain Management Directive.16 This systematically adjusted approach is associated with improved patient satisfaction and health outcomes for pain and depression.17,18 At its core, the model promotes engaging patients as active participants in their care along with a team of doctors who can offer an integrated, evidence-based, multimodal, interdisciplinary treatment plan.

To successfully implement this strategy at the VA, patient aligned care teams (PACT) assess and manage patients with common pain conditions through collaboration with mental health, complementary and integrative health services, physical therapy, and other programs, such as opioid renewal clinics and pain schools.19 This collaborative care approach, which the PCP initiates, is step 1 of the SCM-PM. If initial treatment is not successful and patients are not improving as expected, specialty care consultation and collaborative comanagement through interdisciplinary pain specialty teams are sought (step 2). Finally, step 3 involves tertiary, interdisciplinary care, including access to advanced diagnostic and pain rehabilitation programs accredited by the Commission for Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF).

Although the advantages of interdisciplinary pain programs are clear, resource limitations as well as challenges related to competencies of the PCPs, nurses, and associated health care professionals in pain assessment and management can make implementation of these programs, including the SCM-PM, difficult for many clinics and facilities. Thus, identifying effective chronic pain models and strategies, incorporating the philosophy and key elements of interdisciplinary programs, and accounting for facility resources and capacity are all important.

At the Ann Arbor VAMC, development of a comprehensive interdisciplinary team started with the implementation of joint sessions with a clinical pharmacist and health psychologist embedded in primary care to enhance access to behavioral pain management interventions.20 This program was subsequently expanded to include a pain physician, 2 pain-focused physical therapists (PTs) and a pain nurse.

This article describes a novel team approach for providing more comprehensive, interdisciplinary care for patients with chronic pain along with the initial results for the patients who were part of an outpatient pain group program (OPGP).

Methods

Developing a more interdisciplinary pain management program included integrating different services and creating a strategy for comprehensive evaluation and management of patients with chronic pain. After patients were referred to the interdisciplinary pain clinic by their PCP, they received a systematically structured multidimensional assessment. The primary focus of this assessment was to create an individually directed treatment approach based on the patient’s responses to previous treatments and information collected from several questionnaires administered prior to evaluation. This information helped guide individual patient decision making and actively engaged patients in their care, thus following one of the central tenants of the SCM-PM model. Moreover, functional restoration was at the core of each patient’s evaluation and management. The primary focus was on nonpharmacologic treatment options that included psychological, physical, and occupational therapy; self-management; education; and complementary and alternative therapies. These modalities were offered either individually or in a group setting.

The first step after referral was an evaluation that followed the main core principles for complex disease management described by Tauben and Theodore.21 All new patients were asked to complete a 2-question pain intensity and pain interference measure, the 4-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4), 4-question Primary Care-PTSD screening tool (PC-PTSD), and the STOP-BANG questionnaire to assess the risk for obstructive sleep apnea.22-24 Each measure allowed the physician to identify specific problem areas and formulate a treatment plan that would incorporate PTs or occupational therapists, psychologists and/or clinical specialists, and pharmacists if needed.

Patients who were found to have or expressed significant disability because of pain and who wished to learn pain self-management strategies could participate in an 8-week OPGP. This program included the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) strategies along with group physical therapy classes. Some patients also received individual therapies concurrently with the 8-week OPGP. Patients were excluded from participating in the OPGP only if their current medical or psychiatric status precluded them from full engagement and maximum benefit as determined by the pain physician and psychologist.

Participants and Intervention

Program participants were patients with a chronic pain diagnosis who enrolled in the interdisciplinary pain team OPGP between April 2016 and April 2017. Most patients were referred by their PCPs due to chronic low back, neck, joint or neuropathic pain, although many presented with multiple pain areas. The onset of pain often was a result of a service-related injury or overuse, or the etiology was unknown.

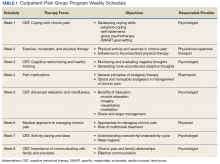

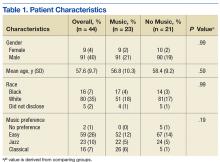

A board-certified pain physician, licensed clinical psychologist, 2 licensed PTs, and a clinical pharmacist led the OPGP sessions. The program was composed of 3-hour-long sessions held weekly for 8 consecutive weeks. Each week, a member of the team covered a specific topic (Table 1).

These sessions focused on the importance of exercise, movement, and physical therapy; appropriate use of medications for managing chronic pain; pacing activities and body mechanics; and the medical approach to managing chronic pain. In addition to didactic presentations, interaction and therapeutic dialogue was encouraged among patients. The education portion of each weekly session lasted about 90 minutes, including a short break. Then, following another short break, patients proceeded to the physical therapy area and engaged in an individualized, monitored exercise program, conducted by the team PTs. Patients also were issued pedometers and encouraged to track their steps each day. Education in improving posture and body mechanics was a key component of the exercise portion of the program so patients could resume their normal daily activities and regain enjoyment in their life. Pain outcomemeasures were collected at admission and immediately before discharge.

Medication management also was an important part of the program for some patients and included tapering off opioids and other drugs and implementing trials of adjuvant pain medications shown to help chronic pain. For some patients, this medication management continued after the patient completed the program.

Measures

The Pain Outcome Questionnaire (POQ) is a 19-item, self-report measure of pain treatment outcomes. Pain rating, mobility, activities of daily living, vitality, negative effect, and fear are the functioning domains evaluated, and the subscale scores are added to produce a total score. The POQ was developed from samples of veterans undergoing inpatient or outpatient pain treatment at VA facilities. For each of the subscales and the total score, higher values indicate poorer outcomes. In normative outpatient VA samples, a total score of 71 is at the 25th percentile, and 120 is at the 75th percentile. The POQ has been shown to have good reliability and validity among veterans in an outpatient setting.25

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) is a 13-item scale designed to measure various levels of pain catastrophizing.26 Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). The PCS consists of 3 subscale domains: rumination, 4 items; magnification, 3 items; and helplessness, 6 items. Responses to all items also can be added to produce a total score from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating a higher level of catastrophic thinking related to pain. This project evaluated both the total score and the 3 subscale scores.

The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses confidence in an individual’s ability to cope or to perform activities despite the pain.27 The PSEQ covers a range of functions, including household chores, socializing, work, as well as coping with pain without medications. Each question has a 7-point Likert scale response: 0 = not at all confident, and 7 = completely confident, to produce a total score from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate stronger pain self-efficacy, which has been shown to be associated with return to work and maintenance of functional gains.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) is a 4-item instrument used to screen for depression and anxiety in outpatient medical settings.22 Patients indicate how often they have been bothered by certain problems on a 4-point Likert scale, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The PHQ-4 provides a total score (0-12) with scores of 6 to 8 indicating moderate and 9 to 12 indicating severe psychological distress; 2 subscale scores, 1 for anxiety (2 questions) and 1 for depression (2 questions). For this analysis, the total PHQ-4 score has been dichotomized with 1 indicating a score in the moderate or severe range vs 0 for a score of mild or no psychological distress. Likewise, each of the subscale scores have been dichotomized with 1 indicating a score of 3 or greater, which is considered a positive screen.

The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) measures the distance (in feet) an individual can walk over a total of 6 minutes on a hard, flat surface.28 Even though the individual can walk at a self-selected pace and rest if needed during the test, the goal is for the patient to walk as far as possible over the course of 6 minutes. The 6MWT provides information regarding functional capacity, response to therapy, and prognosis across a range of chronic conditions, including pain.

Data Analysis

Data analysis included the use of both descriptive and comparative statistics. A descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the characteristics of patients who did and did not complete the OPGP. Specific outcomes for those individuals who completed the program, and thus had complete pre- and post-OPGP information, then were compared. Paired t tests were used to compare differences in continuous measures between baseline (pre-OPGP) and the 8-week follow-up (post-OPGP). Comparisons involving dichotomous measures were made using the Fisher exact test. A 2-sided α with a P value .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

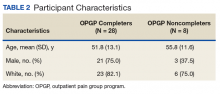

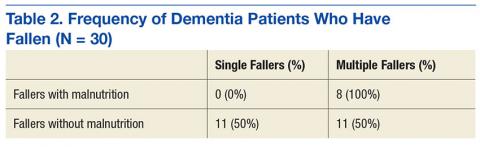

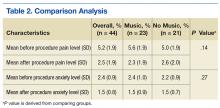

A total of 36 patients enrolled, and 28 (77%) completed the OPGP. Patients who did not complete the program (n = 8) either self-discharged due to lack of interest or had difficulty in consistently making their appointments and decided not to continue (Table 2).

Outcomes for OPGP Completers

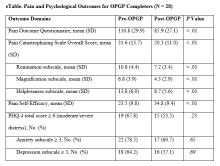

Improvements were observed for all outcome domains among patients who completed the program (eTable).

Discussion

This report describes the novel model for improving delivery of chronic pain management services implemented at the Ann Arbor VAMC through the development of a multidisciplinary pain PACT. The program included using a systematically structured multidimensional approach to identify appropriate treatments and delivery of interdisciplinary care for patients with chronic pain through an OPGP. The authors’ findings establish the feasibility and acceptability of the OPGP. More than 75% of those enrolled completed the program, indicating the promising potential of this approach with significant improvements observed for several pain-related outcomes among those who completed the 8-week program.

Stepped care is a well-established approach to managing complex chronic pain conditions. The approach adds increased levels of treatment intensity when there is no improvement after initial, simple measures are instituted (eg, over-the-counter pain medications, physical therapy, life style changes). Understanding the complexity of the pain experience while treating the patient and not simply the pain has the highest likelihood of helping patients with chronic pain. Given the prevalence of chronic pain among patients in primary care nationally, measurement-based pain care potentially could result in an earlier referral to appropriate care well before pain becomes intractable and chronic.

Growing evidence shows that multidisciplinary treatments reduce pain symptoms and intensity, medication, health care provider use, and improve quality of life.11-15,29,30 A systematic review by van Tulder and colleagues, for example, noted improvements in physical parameters, such as range of motion and flexibility and behavioral health parameters, including anxiety, depression, and cognition.29 Similarly, the cohort of patients who participated in the OPGP showed statistically significant improvements in several domains of pain-related distress and functioning following treatment, including pain catastrophizing, pain self-efficacy, and the multicomponent pain outcomes questionnaires. Functional improvement also was observed by comparing the distance walked in 6 minutes before and after program completion.

There is significant variation in duration of rehabilitation programs lasting from 2 weeks to 12 weeks or longer. These sessions consist of half days, daily sessions, weekly sessions, and monthly sessions. Inconsistencies also exist among programs that use 3 to 280 professional contact hours. Although it has been shown that programs with more than 100 hours of professional contact tended to have better outcomes than did those with less than 30 hours of contact, Stratton and colleagues reported that a 6-week group program was equivalent or better than a 12- and 10-week group program among veterans.11,31 These findings along with staffing and resource constraints led to the implementation of the 8-week OPGP with fewer than 30 hours of contact time per group. These results have important practical implications, as shorter treatments may offer comparable therapeutic impact than do longer, more time-intensive protocols.

Limitations

These findings were derived from a quality improvement project within one institution, and several limitations exist. Although the broader purpose of the article was to show how the fundamentals of creating a cohesive multidisciplinary chronic pain team can be implemented within the VA setting, the highlighted outcomes were primarily from participants in the OPGP Since this was not a controlled or experimental study and given potential sample size and selections issues as well as the lack of longer-term follow-up information, further study is needed to draw definitive conclusions about program effectiveness, despite promising preliminary results. In addition, medication use, such as opioids either before or after completion of the program, was not included as part of this evaluation. As previously discussed, medication management for some patients continued beyond the 8-week time frame of the OPGP. Nonetheless, understanding the impact of this team approach on opioid use also is an important topic for future research.

Despite these limitations, the described model could be a feasible option for improving pain management in outpatient practices not only within the VA but in community settings.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the use of short-term, structured therapeutic protocols could be a potentially effective strategy for the behavioral treatment of chronic pain conditions among veterans. The development and implementation of effective, innovative, evidence-based practice to address the needs of patients with chronic pain is an important priority for maximizing clinical service delivery and meeting the needs of the nation’s veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the previous Associate Chief of Staff, Ambulatory Care, Clinton Greenstone, MD, and Director of Primary Care Adam Tremblay, MD, for their vision, leadership, and support of the team and its efforts.

This work was supported in part through a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 11-222) awarded to Sarah Krein, PhD.

1. Kerns RD, Otis J, Rosenberg R, Reid MC. Veterans’ reports of pain and associations with ratings of health, health-risk behaviors, affective distress, and use of the healthcare system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5):371-379.

2. Yu W, Ravelo A, Wagner TH, et al. Prevalence and cost of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(suppl 3):146S-167S.

3. Gironda RJ, Clark ME, Massengale JP, Walker RL. Pain among veterans of operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Pain Med. 2006;7(4):339-343.

4. Cifu DX, Taylor BC, Carne WF, et al. Traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pain diagnoses in OIF/OEF/OND veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1169-1176.

5. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

6. Bergman AA, Matthias MS, Coffing JM, Krebs EE. Contrasting tensions between patients and PCPs in chronic pain management: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2013;14(11):1689-1697.

7. Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514-519.

8. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-related toxicity or overdose among Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1911-1929.

9. Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321.

10. Chou R, Clark E, Helfand M. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting oral opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(5):1026-1048.

11. Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;322(7301):1511-1516.

12. Gatchel RJ, Okifuji A. Evidence-based scientific data documenting the treatment and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive pain programs for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2006;7(11):779-793.

13. Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49(2):221-230.

14. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670-678.

15. Patrick LE, Altmaier EM, Found EM. Long-term outcomes in multidisciplinary treatment of chronic low back pain: results of a 13-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(8):850-855.

16. Moore BA, Anderson D, Dorflinger L, et al. Stepped care model for pain management and quality of pain care in long-term opioid therapy. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):137-146.

17. Anderson DR, Zlateva I, Coman EN, Khatri K, Tian T, Kerns RD. Improving pain care through implementation of the stepped care model at a multisite community health center. J Pain Res. 2016;9:1021-1029.

18. Scott EL, Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z. Beneficial effects of improvement in depression, pain catastrophizing, and anxiety on pain outcomes: a 12-month longitudinal analysis. J Pain. 2016;17(2):215-222.

19. Kerns RD, Philip EJ, Lee AW, Rosenberger PH. Implementation of the Veterans Health Administration national pain management strategy. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):635-643.

20. Bloor LE, Fisher C, Grix B, Zaleon CR, Wice S. Conjoint sessions with clinical pharmacy and health psychology for chronic pain. Fed Pract. 2017;34(4):35-41.

21. Tauben D, Theodore BR. Measurement-based stepped care approach to interdisciplinary chronic pain management. In: Benzon HT, Rathmell JP, Wu CL, et al, eds. Practical Management of Pain. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2013:37-46.

22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621.

23. Ouimette P, Wade M, Prins A, Schohn M. Identifying PTSD in primary care: comparison of the primary care-PTSD screen (PC-PTSD) and the general health questionnaire-12 (GHQ). J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(2):337-343.

24. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

25. Clark ME, Gironda RJ, Young RW. Development and validation of the pain outcomes questionnaire-VA. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5):381-395.

26. Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524-532.

27. Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):153-163.

28. Peppin JF, Marcum S, Kirsh KL. The chronic pain patient and functional assessment: use of the 6-minute walk test in a multidisciplinary pain clinic. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(3):361-365.

29. van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJ. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane back review group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(20):2688-2699.

30. Sanders SH, Harden RN, Vicente PJ. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for interdisciplinary rehabilitation of chronic nonmalignant pain syndrome patients. Pain Pract. 2005;5(4):303-315.

31. Stratton KJ, Bender MC, Cameron JJ, Pickett TC. Development and evaluation of a behavioral pain management treatment program in a veterans affairs medical center. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):263-268.

Chronic pain is a common health care problem that remains a significant burden for the VHA.1,2 Some reports indicate that nearly 50% of VA patients report chronic pain.3,4 Both within and outside the VHA, primary care providers (PCPs) generally manage patients with chronic pain.5,6 Historically, a biomedical approach to chronic pain also included the use of opioid medications, which may have contributed to increased opioid-related morbidity and mortality especially among the veteran patient population.7-9 The use of opioids also is controversial due to concerns about adverse effects (AEs), long-term efficacy, functional outcomes, and the potential for drug abuse and addiction.10 Consequently, alternative treatment options that incorporate an interdisciplinary approach have gained significant interest among pain care providers.11 Interdisciplinary programs have been shown to improve functional status and psychological well-being and to reduce pain severity and opioid use.12-14 These benefits may persist for a decade or longer.15

Background

The Stepped Care Model for Pain Management (SCM-PM) is a specific pain treatment approach promoted by the VA National Pain Management Directive.16 This systematically adjusted approach is associated with improved patient satisfaction and health outcomes for pain and depression.17,18 At its core, the model promotes engaging patients as active participants in their care along with a team of doctors who can offer an integrated, evidence-based, multimodal, interdisciplinary treatment plan.

To successfully implement this strategy at the VA, patient aligned care teams (PACT) assess and manage patients with common pain conditions through collaboration with mental health, complementary and integrative health services, physical therapy, and other programs, such as opioid renewal clinics and pain schools.19 This collaborative care approach, which the PCP initiates, is step 1 of the SCM-PM. If initial treatment is not successful and patients are not improving as expected, specialty care consultation and collaborative comanagement through interdisciplinary pain specialty teams are sought (step 2). Finally, step 3 involves tertiary, interdisciplinary care, including access to advanced diagnostic and pain rehabilitation programs accredited by the Commission for Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF).

Although the advantages of interdisciplinary pain programs are clear, resource limitations as well as challenges related to competencies of the PCPs, nurses, and associated health care professionals in pain assessment and management can make implementation of these programs, including the SCM-PM, difficult for many clinics and facilities. Thus, identifying effective chronic pain models and strategies, incorporating the philosophy and key elements of interdisciplinary programs, and accounting for facility resources and capacity are all important.

At the Ann Arbor VAMC, development of a comprehensive interdisciplinary team started with the implementation of joint sessions with a clinical pharmacist and health psychologist embedded in primary care to enhance access to behavioral pain management interventions.20 This program was subsequently expanded to include a pain physician, 2 pain-focused physical therapists (PTs) and a pain nurse.

This article describes a novel team approach for providing more comprehensive, interdisciplinary care for patients with chronic pain along with the initial results for the patients who were part of an outpatient pain group program (OPGP).

Methods

Developing a more interdisciplinary pain management program included integrating different services and creating a strategy for comprehensive evaluation and management of patients with chronic pain. After patients were referred to the interdisciplinary pain clinic by their PCP, they received a systematically structured multidimensional assessment. The primary focus of this assessment was to create an individually directed treatment approach based on the patient’s responses to previous treatments and information collected from several questionnaires administered prior to evaluation. This information helped guide individual patient decision making and actively engaged patients in their care, thus following one of the central tenants of the SCM-PM model. Moreover, functional restoration was at the core of each patient’s evaluation and management. The primary focus was on nonpharmacologic treatment options that included psychological, physical, and occupational therapy; self-management; education; and complementary and alternative therapies. These modalities were offered either individually or in a group setting.

The first step after referral was an evaluation that followed the main core principles for complex disease management described by Tauben and Theodore.21 All new patients were asked to complete a 2-question pain intensity and pain interference measure, the 4-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4), 4-question Primary Care-PTSD screening tool (PC-PTSD), and the STOP-BANG questionnaire to assess the risk for obstructive sleep apnea.22-24 Each measure allowed the physician to identify specific problem areas and formulate a treatment plan that would incorporate PTs or occupational therapists, psychologists and/or clinical specialists, and pharmacists if needed.

Patients who were found to have or expressed significant disability because of pain and who wished to learn pain self-management strategies could participate in an 8-week OPGP. This program included the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) strategies along with group physical therapy classes. Some patients also received individual therapies concurrently with the 8-week OPGP. Patients were excluded from participating in the OPGP only if their current medical or psychiatric status precluded them from full engagement and maximum benefit as determined by the pain physician and psychologist.

Participants and Intervention

Program participants were patients with a chronic pain diagnosis who enrolled in the interdisciplinary pain team OPGP between April 2016 and April 2017. Most patients were referred by their PCPs due to chronic low back, neck, joint or neuropathic pain, although many presented with multiple pain areas. The onset of pain often was a result of a service-related injury or overuse, or the etiology was unknown.

A board-certified pain physician, licensed clinical psychologist, 2 licensed PTs, and a clinical pharmacist led the OPGP sessions. The program was composed of 3-hour-long sessions held weekly for 8 consecutive weeks. Each week, a member of the team covered a specific topic (Table 1).

These sessions focused on the importance of exercise, movement, and physical therapy; appropriate use of medications for managing chronic pain; pacing activities and body mechanics; and the medical approach to managing chronic pain. In addition to didactic presentations, interaction and therapeutic dialogue was encouraged among patients. The education portion of each weekly session lasted about 90 minutes, including a short break. Then, following another short break, patients proceeded to the physical therapy area and engaged in an individualized, monitored exercise program, conducted by the team PTs. Patients also were issued pedometers and encouraged to track their steps each day. Education in improving posture and body mechanics was a key component of the exercise portion of the program so patients could resume their normal daily activities and regain enjoyment in their life. Pain outcomemeasures were collected at admission and immediately before discharge.

Medication management also was an important part of the program for some patients and included tapering off opioids and other drugs and implementing trials of adjuvant pain medications shown to help chronic pain. For some patients, this medication management continued after the patient completed the program.

Measures

The Pain Outcome Questionnaire (POQ) is a 19-item, self-report measure of pain treatment outcomes. Pain rating, mobility, activities of daily living, vitality, negative effect, and fear are the functioning domains evaluated, and the subscale scores are added to produce a total score. The POQ was developed from samples of veterans undergoing inpatient or outpatient pain treatment at VA facilities. For each of the subscales and the total score, higher values indicate poorer outcomes. In normative outpatient VA samples, a total score of 71 is at the 25th percentile, and 120 is at the 75th percentile. The POQ has been shown to have good reliability and validity among veterans in an outpatient setting.25

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) is a 13-item scale designed to measure various levels of pain catastrophizing.26 Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). The PCS consists of 3 subscale domains: rumination, 4 items; magnification, 3 items; and helplessness, 6 items. Responses to all items also can be added to produce a total score from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating a higher level of catastrophic thinking related to pain. This project evaluated both the total score and the 3 subscale scores.

The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses confidence in an individual’s ability to cope or to perform activities despite the pain.27 The PSEQ covers a range of functions, including household chores, socializing, work, as well as coping with pain without medications. Each question has a 7-point Likert scale response: 0 = not at all confident, and 7 = completely confident, to produce a total score from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate stronger pain self-efficacy, which has been shown to be associated with return to work and maintenance of functional gains.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) is a 4-item instrument used to screen for depression and anxiety in outpatient medical settings.22 Patients indicate how often they have been bothered by certain problems on a 4-point Likert scale, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The PHQ-4 provides a total score (0-12) with scores of 6 to 8 indicating moderate and 9 to 12 indicating severe psychological distress; 2 subscale scores, 1 for anxiety (2 questions) and 1 for depression (2 questions). For this analysis, the total PHQ-4 score has been dichotomized with 1 indicating a score in the moderate or severe range vs 0 for a score of mild or no psychological distress. Likewise, each of the subscale scores have been dichotomized with 1 indicating a score of 3 or greater, which is considered a positive screen.

The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) measures the distance (in feet) an individual can walk over a total of 6 minutes on a hard, flat surface.28 Even though the individual can walk at a self-selected pace and rest if needed during the test, the goal is for the patient to walk as far as possible over the course of 6 minutes. The 6MWT provides information regarding functional capacity, response to therapy, and prognosis across a range of chronic conditions, including pain.

Data Analysis

Data analysis included the use of both descriptive and comparative statistics. A descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the characteristics of patients who did and did not complete the OPGP. Specific outcomes for those individuals who completed the program, and thus had complete pre- and post-OPGP information, then were compared. Paired t tests were used to compare differences in continuous measures between baseline (pre-OPGP) and the 8-week follow-up (post-OPGP). Comparisons involving dichotomous measures were made using the Fisher exact test. A 2-sided α with a P value .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 36 patients enrolled, and 28 (77%) completed the OPGP. Patients who did not complete the program (n = 8) either self-discharged due to lack of interest or had difficulty in consistently making their appointments and decided not to continue (Table 2).

Outcomes for OPGP Completers

Improvements were observed for all outcome domains among patients who completed the program (eTable).

Discussion

This report describes the novel model for improving delivery of chronic pain management services implemented at the Ann Arbor VAMC through the development of a multidisciplinary pain PACT. The program included using a systematically structured multidimensional approach to identify appropriate treatments and delivery of interdisciplinary care for patients with chronic pain through an OPGP. The authors’ findings establish the feasibility and acceptability of the OPGP. More than 75% of those enrolled completed the program, indicating the promising potential of this approach with significant improvements observed for several pain-related outcomes among those who completed the 8-week program.

Stepped care is a well-established approach to managing complex chronic pain conditions. The approach adds increased levels of treatment intensity when there is no improvement after initial, simple measures are instituted (eg, over-the-counter pain medications, physical therapy, life style changes). Understanding the complexity of the pain experience while treating the patient and not simply the pain has the highest likelihood of helping patients with chronic pain. Given the prevalence of chronic pain among patients in primary care nationally, measurement-based pain care potentially could result in an earlier referral to appropriate care well before pain becomes intractable and chronic.

Growing evidence shows that multidisciplinary treatments reduce pain symptoms and intensity, medication, health care provider use, and improve quality of life.11-15,29,30 A systematic review by van Tulder and colleagues, for example, noted improvements in physical parameters, such as range of motion and flexibility and behavioral health parameters, including anxiety, depression, and cognition.29 Similarly, the cohort of patients who participated in the OPGP showed statistically significant improvements in several domains of pain-related distress and functioning following treatment, including pain catastrophizing, pain self-efficacy, and the multicomponent pain outcomes questionnaires. Functional improvement also was observed by comparing the distance walked in 6 minutes before and after program completion.

There is significant variation in duration of rehabilitation programs lasting from 2 weeks to 12 weeks or longer. These sessions consist of half days, daily sessions, weekly sessions, and monthly sessions. Inconsistencies also exist among programs that use 3 to 280 professional contact hours. Although it has been shown that programs with more than 100 hours of professional contact tended to have better outcomes than did those with less than 30 hours of contact, Stratton and colleagues reported that a 6-week group program was equivalent or better than a 12- and 10-week group program among veterans.11,31 These findings along with staffing and resource constraints led to the implementation of the 8-week OPGP with fewer than 30 hours of contact time per group. These results have important practical implications, as shorter treatments may offer comparable therapeutic impact than do longer, more time-intensive protocols.

Limitations

These findings were derived from a quality improvement project within one institution, and several limitations exist. Although the broader purpose of the article was to show how the fundamentals of creating a cohesive multidisciplinary chronic pain team can be implemented within the VA setting, the highlighted outcomes were primarily from participants in the OPGP Since this was not a controlled or experimental study and given potential sample size and selections issues as well as the lack of longer-term follow-up information, further study is needed to draw definitive conclusions about program effectiveness, despite promising preliminary results. In addition, medication use, such as opioids either before or after completion of the program, was not included as part of this evaluation. As previously discussed, medication management for some patients continued beyond the 8-week time frame of the OPGP. Nonetheless, understanding the impact of this team approach on opioid use also is an important topic for future research.

Despite these limitations, the described model could be a feasible option for improving pain management in outpatient practices not only within the VA but in community settings.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the use of short-term, structured therapeutic protocols could be a potentially effective strategy for the behavioral treatment of chronic pain conditions among veterans. The development and implementation of effective, innovative, evidence-based practice to address the needs of patients with chronic pain is an important priority for maximizing clinical service delivery and meeting the needs of the nation’s veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the previous Associate Chief of Staff, Ambulatory Care, Clinton Greenstone, MD, and Director of Primary Care Adam Tremblay, MD, for their vision, leadership, and support of the team and its efforts.

This work was supported in part through a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 11-222) awarded to Sarah Krein, PhD.

Chronic pain is a common health care problem that remains a significant burden for the VHA.1,2 Some reports indicate that nearly 50% of VA patients report chronic pain.3,4 Both within and outside the VHA, primary care providers (PCPs) generally manage patients with chronic pain.5,6 Historically, a biomedical approach to chronic pain also included the use of opioid medications, which may have contributed to increased opioid-related morbidity and mortality especially among the veteran patient population.7-9 The use of opioids also is controversial due to concerns about adverse effects (AEs), long-term efficacy, functional outcomes, and the potential for drug abuse and addiction.10 Consequently, alternative treatment options that incorporate an interdisciplinary approach have gained significant interest among pain care providers.11 Interdisciplinary programs have been shown to improve functional status and psychological well-being and to reduce pain severity and opioid use.12-14 These benefits may persist for a decade or longer.15

Background

The Stepped Care Model for Pain Management (SCM-PM) is a specific pain treatment approach promoted by the VA National Pain Management Directive.16 This systematically adjusted approach is associated with improved patient satisfaction and health outcomes for pain and depression.17,18 At its core, the model promotes engaging patients as active participants in their care along with a team of doctors who can offer an integrated, evidence-based, multimodal, interdisciplinary treatment plan.

To successfully implement this strategy at the VA, patient aligned care teams (PACT) assess and manage patients with common pain conditions through collaboration with mental health, complementary and integrative health services, physical therapy, and other programs, such as opioid renewal clinics and pain schools.19 This collaborative care approach, which the PCP initiates, is step 1 of the SCM-PM. If initial treatment is not successful and patients are not improving as expected, specialty care consultation and collaborative comanagement through interdisciplinary pain specialty teams are sought (step 2). Finally, step 3 involves tertiary, interdisciplinary care, including access to advanced diagnostic and pain rehabilitation programs accredited by the Commission for Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF).

Although the advantages of interdisciplinary pain programs are clear, resource limitations as well as challenges related to competencies of the PCPs, nurses, and associated health care professionals in pain assessment and management can make implementation of these programs, including the SCM-PM, difficult for many clinics and facilities. Thus, identifying effective chronic pain models and strategies, incorporating the philosophy and key elements of interdisciplinary programs, and accounting for facility resources and capacity are all important.

At the Ann Arbor VAMC, development of a comprehensive interdisciplinary team started with the implementation of joint sessions with a clinical pharmacist and health psychologist embedded in primary care to enhance access to behavioral pain management interventions.20 This program was subsequently expanded to include a pain physician, 2 pain-focused physical therapists (PTs) and a pain nurse.

This article describes a novel team approach for providing more comprehensive, interdisciplinary care for patients with chronic pain along with the initial results for the patients who were part of an outpatient pain group program (OPGP).

Methods

Developing a more interdisciplinary pain management program included integrating different services and creating a strategy for comprehensive evaluation and management of patients with chronic pain. After patients were referred to the interdisciplinary pain clinic by their PCP, they received a systematically structured multidimensional assessment. The primary focus of this assessment was to create an individually directed treatment approach based on the patient’s responses to previous treatments and information collected from several questionnaires administered prior to evaluation. This information helped guide individual patient decision making and actively engaged patients in their care, thus following one of the central tenants of the SCM-PM model. Moreover, functional restoration was at the core of each patient’s evaluation and management. The primary focus was on nonpharmacologic treatment options that included psychological, physical, and occupational therapy; self-management; education; and complementary and alternative therapies. These modalities were offered either individually or in a group setting.

The first step after referral was an evaluation that followed the main core principles for complex disease management described by Tauben and Theodore.21 All new patients were asked to complete a 2-question pain intensity and pain interference measure, the 4-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4), 4-question Primary Care-PTSD screening tool (PC-PTSD), and the STOP-BANG questionnaire to assess the risk for obstructive sleep apnea.22-24 Each measure allowed the physician to identify specific problem areas and formulate a treatment plan that would incorporate PTs or occupational therapists, psychologists and/or clinical specialists, and pharmacists if needed.

Patients who were found to have or expressed significant disability because of pain and who wished to learn pain self-management strategies could participate in an 8-week OPGP. This program included the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) strategies along with group physical therapy classes. Some patients also received individual therapies concurrently with the 8-week OPGP. Patients were excluded from participating in the OPGP only if their current medical or psychiatric status precluded them from full engagement and maximum benefit as determined by the pain physician and psychologist.

Participants and Intervention

Program participants were patients with a chronic pain diagnosis who enrolled in the interdisciplinary pain team OPGP between April 2016 and April 2017. Most patients were referred by their PCPs due to chronic low back, neck, joint or neuropathic pain, although many presented with multiple pain areas. The onset of pain often was a result of a service-related injury or overuse, or the etiology was unknown.

A board-certified pain physician, licensed clinical psychologist, 2 licensed PTs, and a clinical pharmacist led the OPGP sessions. The program was composed of 3-hour-long sessions held weekly for 8 consecutive weeks. Each week, a member of the team covered a specific topic (Table 1).

These sessions focused on the importance of exercise, movement, and physical therapy; appropriate use of medications for managing chronic pain; pacing activities and body mechanics; and the medical approach to managing chronic pain. In addition to didactic presentations, interaction and therapeutic dialogue was encouraged among patients. The education portion of each weekly session lasted about 90 minutes, including a short break. Then, following another short break, patients proceeded to the physical therapy area and engaged in an individualized, monitored exercise program, conducted by the team PTs. Patients also were issued pedometers and encouraged to track their steps each day. Education in improving posture and body mechanics was a key component of the exercise portion of the program so patients could resume their normal daily activities and regain enjoyment in their life. Pain outcomemeasures were collected at admission and immediately before discharge.

Medication management also was an important part of the program for some patients and included tapering off opioids and other drugs and implementing trials of adjuvant pain medications shown to help chronic pain. For some patients, this medication management continued after the patient completed the program.

Measures

The Pain Outcome Questionnaire (POQ) is a 19-item, self-report measure of pain treatment outcomes. Pain rating, mobility, activities of daily living, vitality, negative effect, and fear are the functioning domains evaluated, and the subscale scores are added to produce a total score. The POQ was developed from samples of veterans undergoing inpatient or outpatient pain treatment at VA facilities. For each of the subscales and the total score, higher values indicate poorer outcomes. In normative outpatient VA samples, a total score of 71 is at the 25th percentile, and 120 is at the 75th percentile. The POQ has been shown to have good reliability and validity among veterans in an outpatient setting.25

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) is a 13-item scale designed to measure various levels of pain catastrophizing.26 Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). The PCS consists of 3 subscale domains: rumination, 4 items; magnification, 3 items; and helplessness, 6 items. Responses to all items also can be added to produce a total score from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating a higher level of catastrophic thinking related to pain. This project evaluated both the total score and the 3 subscale scores.

The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses confidence in an individual’s ability to cope or to perform activities despite the pain.27 The PSEQ covers a range of functions, including household chores, socializing, work, as well as coping with pain without medications. Each question has a 7-point Likert scale response: 0 = not at all confident, and 7 = completely confident, to produce a total score from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate stronger pain self-efficacy, which has been shown to be associated with return to work and maintenance of functional gains.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) is a 4-item instrument used to screen for depression and anxiety in outpatient medical settings.22 Patients indicate how often they have been bothered by certain problems on a 4-point Likert scale, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The PHQ-4 provides a total score (0-12) with scores of 6 to 8 indicating moderate and 9 to 12 indicating severe psychological distress; 2 subscale scores, 1 for anxiety (2 questions) and 1 for depression (2 questions). For this analysis, the total PHQ-4 score has been dichotomized with 1 indicating a score in the moderate or severe range vs 0 for a score of mild or no psychological distress. Likewise, each of the subscale scores have been dichotomized with 1 indicating a score of 3 or greater, which is considered a positive screen.

The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) measures the distance (in feet) an individual can walk over a total of 6 minutes on a hard, flat surface.28 Even though the individual can walk at a self-selected pace and rest if needed during the test, the goal is for the patient to walk as far as possible over the course of 6 minutes. The 6MWT provides information regarding functional capacity, response to therapy, and prognosis across a range of chronic conditions, including pain.

Data Analysis

Data analysis included the use of both descriptive and comparative statistics. A descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the characteristics of patients who did and did not complete the OPGP. Specific outcomes for those individuals who completed the program, and thus had complete pre- and post-OPGP information, then were compared. Paired t tests were used to compare differences in continuous measures between baseline (pre-OPGP) and the 8-week follow-up (post-OPGP). Comparisons involving dichotomous measures were made using the Fisher exact test. A 2-sided α with a P value .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 36 patients enrolled, and 28 (77%) completed the OPGP. Patients who did not complete the program (n = 8) either self-discharged due to lack of interest or had difficulty in consistently making their appointments and decided not to continue (Table 2).

Outcomes for OPGP Completers

Improvements were observed for all outcome domains among patients who completed the program (eTable).

Discussion

This report describes the novel model for improving delivery of chronic pain management services implemented at the Ann Arbor VAMC through the development of a multidisciplinary pain PACT. The program included using a systematically structured multidimensional approach to identify appropriate treatments and delivery of interdisciplinary care for patients with chronic pain through an OPGP. The authors’ findings establish the feasibility and acceptability of the OPGP. More than 75% of those enrolled completed the program, indicating the promising potential of this approach with significant improvements observed for several pain-related outcomes among those who completed the 8-week program.

Stepped care is a well-established approach to managing complex chronic pain conditions. The approach adds increased levels of treatment intensity when there is no improvement after initial, simple measures are instituted (eg, over-the-counter pain medications, physical therapy, life style changes). Understanding the complexity of the pain experience while treating the patient and not simply the pain has the highest likelihood of helping patients with chronic pain. Given the prevalence of chronic pain among patients in primary care nationally, measurement-based pain care potentially could result in an earlier referral to appropriate care well before pain becomes intractable and chronic.

Growing evidence shows that multidisciplinary treatments reduce pain symptoms and intensity, medication, health care provider use, and improve quality of life.11-15,29,30 A systematic review by van Tulder and colleagues, for example, noted improvements in physical parameters, such as range of motion and flexibility and behavioral health parameters, including anxiety, depression, and cognition.29 Similarly, the cohort of patients who participated in the OPGP showed statistically significant improvements in several domains of pain-related distress and functioning following treatment, including pain catastrophizing, pain self-efficacy, and the multicomponent pain outcomes questionnaires. Functional improvement also was observed by comparing the distance walked in 6 minutes before and after program completion.

There is significant variation in duration of rehabilitation programs lasting from 2 weeks to 12 weeks or longer. These sessions consist of half days, daily sessions, weekly sessions, and monthly sessions. Inconsistencies also exist among programs that use 3 to 280 professional contact hours. Although it has been shown that programs with more than 100 hours of professional contact tended to have better outcomes than did those with less than 30 hours of contact, Stratton and colleagues reported that a 6-week group program was equivalent or better than a 12- and 10-week group program among veterans.11,31 These findings along with staffing and resource constraints led to the implementation of the 8-week OPGP with fewer than 30 hours of contact time per group. These results have important practical implications, as shorter treatments may offer comparable therapeutic impact than do longer, more time-intensive protocols.

Limitations

These findings were derived from a quality improvement project within one institution, and several limitations exist. Although the broader purpose of the article was to show how the fundamentals of creating a cohesive multidisciplinary chronic pain team can be implemented within the VA setting, the highlighted outcomes were primarily from participants in the OPGP Since this was not a controlled or experimental study and given potential sample size and selections issues as well as the lack of longer-term follow-up information, further study is needed to draw definitive conclusions about program effectiveness, despite promising preliminary results. In addition, medication use, such as opioids either before or after completion of the program, was not included as part of this evaluation. As previously discussed, medication management for some patients continued beyond the 8-week time frame of the OPGP. Nonetheless, understanding the impact of this team approach on opioid use also is an important topic for future research.

Despite these limitations, the described model could be a feasible option for improving pain management in outpatient practices not only within the VA but in community settings.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the use of short-term, structured therapeutic protocols could be a potentially effective strategy for the behavioral treatment of chronic pain conditions among veterans. The development and implementation of effective, innovative, evidence-based practice to address the needs of patients with chronic pain is an important priority for maximizing clinical service delivery and meeting the needs of the nation’s veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the previous Associate Chief of Staff, Ambulatory Care, Clinton Greenstone, MD, and Director of Primary Care Adam Tremblay, MD, for their vision, leadership, and support of the team and its efforts.

This work was supported in part through a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 11-222) awarded to Sarah Krein, PhD.

1. Kerns RD, Otis J, Rosenberg R, Reid MC. Veterans’ reports of pain and associations with ratings of health, health-risk behaviors, affective distress, and use of the healthcare system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5):371-379.

2. Yu W, Ravelo A, Wagner TH, et al. Prevalence and cost of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(suppl 3):146S-167S.

3. Gironda RJ, Clark ME, Massengale JP, Walker RL. Pain among veterans of operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Pain Med. 2006;7(4):339-343.

4. Cifu DX, Taylor BC, Carne WF, et al. Traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pain diagnoses in OIF/OEF/OND veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1169-1176.

5. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

6. Bergman AA, Matthias MS, Coffing JM, Krebs EE. Contrasting tensions between patients and PCPs in chronic pain management: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2013;14(11):1689-1697.

7. Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514-519.

8. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-related toxicity or overdose among Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1911-1929.

9. Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321.

10. Chou R, Clark E, Helfand M. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting oral opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(5):1026-1048.

11. Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;322(7301):1511-1516.

12. Gatchel RJ, Okifuji A. Evidence-based scientific data documenting the treatment and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive pain programs for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2006;7(11):779-793.

13. Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49(2):221-230.

14. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670-678.

15. Patrick LE, Altmaier EM, Found EM. Long-term outcomes in multidisciplinary treatment of chronic low back pain: results of a 13-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(8):850-855.

16. Moore BA, Anderson D, Dorflinger L, et al. Stepped care model for pain management and quality of pain care in long-term opioid therapy. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):137-146.

17. Anderson DR, Zlateva I, Coman EN, Khatri K, Tian T, Kerns RD. Improving pain care through implementation of the stepped care model at a multisite community health center. J Pain Res. 2016;9:1021-1029.

18. Scott EL, Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z. Beneficial effects of improvement in depression, pain catastrophizing, and anxiety on pain outcomes: a 12-month longitudinal analysis. J Pain. 2016;17(2):215-222.

19. Kerns RD, Philip EJ, Lee AW, Rosenberger PH. Implementation of the Veterans Health Administration national pain management strategy. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):635-643.

20. Bloor LE, Fisher C, Grix B, Zaleon CR, Wice S. Conjoint sessions with clinical pharmacy and health psychology for chronic pain. Fed Pract. 2017;34(4):35-41.

21. Tauben D, Theodore BR. Measurement-based stepped care approach to interdisciplinary chronic pain management. In: Benzon HT, Rathmell JP, Wu CL, et al, eds. Practical Management of Pain. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2013:37-46.

22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621.

23. Ouimette P, Wade M, Prins A, Schohn M. Identifying PTSD in primary care: comparison of the primary care-PTSD screen (PC-PTSD) and the general health questionnaire-12 (GHQ). J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(2):337-343.

24. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

25. Clark ME, Gironda RJ, Young RW. Development and validation of the pain outcomes questionnaire-VA. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5):381-395.

26. Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524-532.

27. Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):153-163.

28. Peppin JF, Marcum S, Kirsh KL. The chronic pain patient and functional assessment: use of the 6-minute walk test in a multidisciplinary pain clinic. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(3):361-365.

29. van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJ. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane back review group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(20):2688-2699.

30. Sanders SH, Harden RN, Vicente PJ. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for interdisciplinary rehabilitation of chronic nonmalignant pain syndrome patients. Pain Pract. 2005;5(4):303-315.

31. Stratton KJ, Bender MC, Cameron JJ, Pickett TC. Development and evaluation of a behavioral pain management treatment program in a veterans affairs medical center. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):263-268.

1. Kerns RD, Otis J, Rosenberg R, Reid MC. Veterans’ reports of pain and associations with ratings of health, health-risk behaviors, affective distress, and use of the healthcare system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5):371-379.

2. Yu W, Ravelo A, Wagner TH, et al. Prevalence and cost of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(suppl 3):146S-167S.

3. Gironda RJ, Clark ME, Massengale JP, Walker RL. Pain among veterans of operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Pain Med. 2006;7(4):339-343.

4. Cifu DX, Taylor BC, Carne WF, et al. Traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pain diagnoses in OIF/OEF/OND veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1169-1176.

5. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

6. Bergman AA, Matthias MS, Coffing JM, Krebs EE. Contrasting tensions between patients and PCPs in chronic pain management: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2013;14(11):1689-1697.

7. Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514-519.

8. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-related toxicity or overdose among Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1911-1929.

9. Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321.

10. Chou R, Clark E, Helfand M. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting oral opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(5):1026-1048.

11. Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;322(7301):1511-1516.

12. Gatchel RJ, Okifuji A. Evidence-based scientific data documenting the treatment and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive pain programs for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2006;7(11):779-793.

13. Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49(2):221-230.

14. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670-678.

15. Patrick LE, Altmaier EM, Found EM. Long-term outcomes in multidisciplinary treatment of chronic low back pain: results of a 13-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(8):850-855.

16. Moore BA, Anderson D, Dorflinger L, et al. Stepped care model for pain management and quality of pain care in long-term opioid therapy. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):137-146.

17. Anderson DR, Zlateva I, Coman EN, Khatri K, Tian T, Kerns RD. Improving pain care through implementation of the stepped care model at a multisite community health center. J Pain Res. 2016;9:1021-1029.

18. Scott EL, Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z. Beneficial effects of improvement in depression, pain catastrophizing, and anxiety on pain outcomes: a 12-month longitudinal analysis. J Pain. 2016;17(2):215-222.

19. Kerns RD, Philip EJ, Lee AW, Rosenberger PH. Implementation of the Veterans Health Administration national pain management strategy. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):635-643.

20. Bloor LE, Fisher C, Grix B, Zaleon CR, Wice S. Conjoint sessions with clinical pharmacy and health psychology for chronic pain. Fed Pract. 2017;34(4):35-41.

21. Tauben D, Theodore BR. Measurement-based stepped care approach to interdisciplinary chronic pain management. In: Benzon HT, Rathmell JP, Wu CL, et al, eds. Practical Management of Pain. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2013:37-46.

22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621.

23. Ouimette P, Wade M, Prins A, Schohn M. Identifying PTSD in primary care: comparison of the primary care-PTSD screen (PC-PTSD) and the general health questionnaire-12 (GHQ). J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(2):337-343.

24. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

25. Clark ME, Gironda RJ, Young RW. Development and validation of the pain outcomes questionnaire-VA. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5):381-395.

26. Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524-532.

27. Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):153-163.

28. Peppin JF, Marcum S, Kirsh KL. The chronic pain patient and functional assessment: use of the 6-minute walk test in a multidisciplinary pain clinic. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(3):361-365.

29. van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJ. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane back review group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(20):2688-2699.

30. Sanders SH, Harden RN, Vicente PJ. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for interdisciplinary rehabilitation of chronic nonmalignant pain syndrome patients. Pain Pract. 2005;5(4):303-315.

31. Stratton KJ, Bender MC, Cameron JJ, Pickett TC. Development and evaluation of a behavioral pain management treatment program in a veterans affairs medical center. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):263-268.

Psychotherapy Telemental Health Center and Regional Pilot

Within VHA, telemental health (TMH) refers to behavioral health services that are provided remotely, using secure communication technologies, to veterans who are separated by distance from their mental health providers.1 Telemental health sometimes involves video teleconferencing (VTC) technology, where a veteran (or group of veterans) in one location and a provider in a different location are able to communicate in real time through a computer monitor or television screen.2 In the VHA, TMH visits are typically conducted from a central location (such as a medical center hospital) to a community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC), but pilot projects have also tested VTC in homes as well.1,3,4

In addition to providing timely access to behavioral health services in rural or underserved locations, TMH eliminates travel that may be disruptive or costly and allows mental health providers to consult with or provide supervision to one another. Telemental health can be used to make diagnoses, manage care, perform checkups, and provide long-term, follow-up care. Other uses for TMH include clinical assessment, individual and group psychotherapy, psycho-educational interventions, cognitive testing, and general psychiatric care.1,5,6 More recently, TMH has been used to provide evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) to individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health diagnoses.6,7 Such care may be particularly advantageous for veterans with PTSD, because traveling can be a burden for them or a trigger for PTSD symptoms.

Although interactive video technology is becoming widely available, its use is limited in health care systems due to lack of knowledge, education, logistical guidance, and technical training. The authors have conducted EBPs using VTC across VISN 22 in both office-to-office and office-to-home modalities and are providing EBPs using VTC to CBOCs in other VISNs across the western U.S. This article addresses these issues, outlining the necessary steps required to establish a TMH clinic and to share the successes of the EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot used at VISN 22.

Telemental Health

Telemental health is an effective alternative to in-person treatment and is well regarded by both mental health providers and veterans. Overall, mental health providers believe it can help reduce the stigma associated with traditional mental health care and ease transportation-related issues for veterans. Telemental health allows access to care for veterans living in rural or remote areas in addition to those who are incarcerated or are otherwise unable to attend visits at primary VA facilities.2,8-10 In an assessment of TMH services in 40 CBOCs across VISN 16, most CBOC mental health providers found it to be an acceptable alternative to face-to-face care, recognize the value of TMH, and endorse a willingness to use and expand TMH programs within their clinics.11

Veterans who participated in TMH via VTC have expressed satisfaction with the decreased travel time and expenses, fewer interactions with crowds, and fewer parking problems.12 Several studies suggested that veterans preferred TMH to in-person contact due to more rapid access to care and specialists who would otherwise be unavailable at remote locations.5,10 Similarly, veterans who avoid in-person mental health care were more open to remote therapy for many of the reasons listed earlier. Studies suggest that veterans from both rural and urban locations are generally receptive to receiving mental health services via TMH.5,10

Several studies have found that TMH services may have advantages over standard in-person care. These advantages include decreasing transportation costs, travel time, and time missed at work and increasing system coverage area.13 Overall, both veterans and providers reported similar satisfaction between VTC and in-person sessions and, in some cases, prefer VTC interactions due to a sense of “easing into” intense therapies or having a “therapeutic distance” as treatment begins.12

Utility

Previous studies have shown that TMH can be used successfully to provide psychopharmacologic treatment to veterans who have major depressive disorder or schizophrenia, among other psychiatric disorders.5,8,14 Recent studies have focused on the feasibility of providing EBPs via TMH, particularly for the treatment of PTSD.12,15 Studies have shown that TMH services via VTC can be used successfully to provide cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and prolonged exposure therapy (PE).16-21 In these studies, both PE and CPT delivered via TMH were found to be as efficacious as in-person formats. Furthermore, TMH services were successfully used in individual and group sessions.

Research has emphasized the benefits of TMH for veterans who are uncomfortable in crowds, waiting rooms, or hospital lobbies.7,12,18 For patients with PTSD who are initially limited by fears related to driving, TMH can facilitate access to care. Veterans with PTSD often avoid reminders of trauma (ie, uniforms, evidence of physical injury, artwork, photographs related to war), which can often be found at the larger VAMCs. These veterans may find mental health care services in their homes or at local CBOCs more appealing.7,12,18

Implementation

Prior to the implementation of telehealth services, many CBOC providers would refer veterans in need of specialty care to the nearest VAMC, which were sometimes many hours away.1 In response to travel and access concerns, the VA has implemented various telehealth modalities, including TMH.

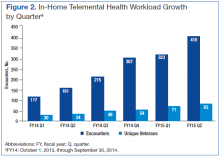

In 2008, about 230,000 veterans received mental health services via real-time clinical VTC at 300 VA CBOCs, and about 40,000 veterans enrolled in the In-Home Telehealth program.22 By 2011, > 380,000 veterans used clinic-based telehealth services and about 100,000 veterans used the in-home program.1 Between 2006 and 2008, the 98,000 veterans who used TMH modalities had fewer hospital admissions compared with those who did not; overall, the need for hospital services decreased by about 25% for those using TMH services.23

Although research suggests that TMH is an effective treatment modality, it does have limitations. A recent study noted several visual and audio difficulties that can emerge, including pixilation, “tracer” images with movement, low resolution, “frozen” or “choppy” images, delays in sound, echoes, or “mechanical sounding” voices.12 In some cases, physical details, such as crying, sniffling, or fidgeting, could not be clearly observed.12 Overall, these unforeseen issues can impact the ability to give and receive care through TMH modalities. Proper procedures need to be developed and implemented for each site.

Getting Started

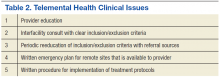

Using TMH to provide mental health care at other VHA facilities requires planning and preparation. Logistics, such as preparation of the room and equipment, should be considered. Similarly, veteran and provider convenience must be considered.2,11 Before starting TMH at any VA facility, professionals working with the audiovisual technology and providing TMH care must complete necessary VA Talent Management System courses and obtain copies of certificates to assure they have met the appropriate training criteria. Providers must be credentialed to provide TMH services, including the telehealth curriculum offered by VA Employee Educational Services.2,24 An appropriate memorandum of understanding (MOU) must be created, and credentialing and privileging must also be acquired.

In addition to provider training, an information technology representative who can administer technical support as needed must be selected for both the provider and remote locations. Technologic complications can make TMH implementation much more challenging.12 As such, it is important to assure that both the veteran and the provider have the necessary TMH equipment. The selected communication device must be compatible with the technology requirements at the provider and remote facilities.12

In addition to designated technical support, the VISN TMH coordinator needs to have point-of-contact information for those who can assist with each site’s telehealth services and address the demand for EBP for PTSD or other desired services. After this information has been obtained, relationships must be developed and maintained with local leadership at each site, associated telehealth coordinators, and evidence-based therapy coordinators.

After contact has been established with remote facilities and the demand for services has been determined, there are several agreements and procedures to put in place before starting TMH services. An initial step is to develop a MOU agreement between the VISN TMH center and remote