User login

The term pain refers to unpleasant sensory, emotional experiences associated with actual or potential tissue damage and is described in terms of such damage.1 Acute pain from neurophysiologic responses to noxious stimuli resolves upon tissue healing or stimuli removal (eg, 3-6 months); however, chronic pain lingers beyond the expected time course of the acute injury and repair process.1,2 Despite pain management advances, the under- or overtreatment of pain for different patient populations (eg, cancer and noncancer) remains an important concern.3,4

Hospitals have focused on optimizing inpatient pain management, because uncontrolled pain remains the most common reason for readmissions the first week postsurgery.5 The safe use of opioids (prescription, illicit synthetic, or heroin) poses major challenges and raises significant concerns. Rates of opioid-related hospital admissions have increased by 42% since 2009, and total overdose deaths reached a new high of 47,055 in 2014, including 28,647 (61%) from opioids.6

Opioids rank among the medications most often associated with serious adverse events (AEs), including respiratory depression and death.7 In response, the Joint Commission recommends patient assessments for opioid-related AEs, technology to monitor opioid prescribing, pharmacist consultation for opioid conversions and route of administration changes, provider education about risks of opioids, and risk screening tools for opioid-related oversedation and respiratory depression.7 Treatment guidelines strive to minimize the impact of acute pain by offering a scientific basis for practice, but evidence suggests a lack of suitable pain programs.7 Increases in opioid prescribing along with clinical guidelines and state laws recommending specialty pain service referrals for patients on high-dose opioids, have increased demand for competent pain clinicians.8

The expertise of a clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS) can help refine ineffective and potentially harmful pain medication therapy in complex patient cases. Existing literature outlines the various benefits of pharmacist participation in collaborative pain services for cancer and noncancer pain, as well as cases involving substance abuse.9-13 Various articles support pharmacists’ role as an educator and team member who can add valuable, trustworthy clinical knowledge that enhances clinical encounters and guides protocol/policy development.12,13 These efforts have improved patient satisfaction and encouraged physicians and nurses to proactively seek pharmacists’ advice for difficult cases.9

Frequent communication with interdisciplinary teams have helped considerably in establishing clinical pharmacy services that benefit patient care and offer sources of professional accomplishment.10,11 For example, pharmacists at Kaweah Delta Medical Center in Visalia, CA launched an innovative pain program that encompassed consultations and opioid stewardship, which demonstrated that pharmacists can improve patient outcomes in the front lines of pain management.14 Pain CPSs have advanced knowledge of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and therapeutics to promote safe and effective analgesic use, as well as to identify opioid use disorders. Evidence suggests that pharmacists’ presence on interdisciplinary pain teams improves outcomes by optimizing medication selection, improving adherence, and preventing AEs.8

Following the plan-do-study-act model for quality improvement (QI), this project hoped to expand current pain programs at the West Palm Beach VAMC (WPBVAMC) by evaluating the feasibility of an inpatient pain pharmacist consult service (IPPCS) at the 301-bed teaching facility, which includes 130 acute/intensive care and 120 nursing/domiciliary beds.15 Staff provide primary- and secondary-level care to veterans in 7 counties along Florida’s southeastern coast.

In 2009, the WPBVAMC PGY-2 Pain Management and Palliative Care Program became the VA’s first accredited pain pharmacy residency. Residents train with the Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation (PMR) and Chronic Pain Management departments, which provide outpatient services from 7 pain physicians, a pain psychologist, registered nurse, chiropractor, acupuncturist, physical/occupational therapy (PT/OT), and 3 pain/palliative care CPSs.

The WPBVAMC had established interdisciplinary outpatient chronic pain clinic (OCPC) physician- and pharmacist-run services along with a pain CPS electronic consult (e-consult) program. However, no formal mechanisms for inpatient pain consultations existed. Prior to the IPPCS outlined in this study, OCPC practitioners, including 2 pain CPSs, managed impromptu inpatient pain issues as “curbside consultations” along with usual day-to-day clinic duties.

The OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy administration recognized the need for more clinical support to manage complex analgesic issues in inpatient veterans, as these patients often have acute pain with underlying chronic pain syndromes. In a national survey, veterans were significantly more likely than were nonveterans to report painful health conditions (65.5% vs 56.4%) and to classify their pain as severe (9.1% vs 6.3%).16 The WPBVAMC administration concluded that an IPPCS would offer a more efficient means of handling such cases. The IPPCS would formally streamline inpatient pain consults, enabling CPSs to thoroughly evaluate pain-related issues to propose evidence-based recommendations.

The primary objective of this QI project was to assess the IPPCS implementation as part of multimodal care to satisfy unmet patient care needs at the WPBVAMC. Secondary objectives for program feasibility included identifying the volume and type of pain consults, categorizing pharmacist interventions, classifying providers’ satisfaction, and determining types of responses to pharmacists’ medication recommendations.

Methods

This QI project ascertained the feasibility of the IPPCS by evaluating all consults obtained during the pilot period from November 2, 2015 through May 6, 2016. The IPPCS was accessible Monday through Friday during normal business hours. Goal turnaround time for consult completion was 24 to 72 hours, given the lack of coverage on holidays and weekends. The target population included veterans hospitalized at the WPBVAMC inpatient ward or nursing home with uncontrolled pain on IV and/or oral analgesic medications. All IPPCS consults submitted during the pilot period were included in the sample.

The WPBVAMC Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) approved this QI program prior to initiation. Following supervisory support from the OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy departments, hospital technologists assisted in creating a consult link in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which allowed providers to submit IPPCS requests for specific patients efficiently. Consults were categorized as postoperative pain, acute or chronic pain, malignant pain, or end-of-life pain. Inpatient providers could enter requests for assistance with 1 or more of the following: opioid dose conversions, opioid taper/titration schedules, general opioid treatment recommendations, or nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations.

The Medical Records Committee approved a customized CPRS subjective-objective-assessment-recommendations (SOAR) note template, which helped standardize the pain CPS documentation. To promote consult requests and interdisciplinary collaboration, inpatient clinicians received education about the IPPCS at respective meetings (eg, General Medicine staff and Clinical Pharmacy meetings).

All CPSs involved in this project were residency-trained in direct patient care, including pain and palliative care, and maintained national board certification as pharmacotherapy specialists. Their role included reviewing patients’ electronic medical records, conducting face-to-face pain assessments, completing opioid risk assessments, evaluating analgesic regimen appropriateness, reviewing medication adherence, completing pain medication reconciliation, querying the Florida Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), interpreting urine drug testing (UDT), and delivering provider/patient/caregiver education. Parameters used to determine the appropriateness of analgesic regimens included, but were not limited to:

- Use of oral instead of IV medications if oral dosing was feasible/possible/appropriate;

- Dose and adjustments per renal/hepatic function;

- Adequate treatment duration and titration;

- No therapeutic drug class duplications;

- Medication tolerability (eg, allergies, AEs, drug interactions); and

- Opioid risk assessment per Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) score and medical history.

Consulting providers clarified patients’ pain diagnoses prior to pharmacy consultations.

After face-to-face patient interviews, the inpatient pain CPS prepared pain management recommendations, including nonopioid/adjuvant pain medications and/or opioid dose adjustments. The IPPCS also collaborated with pain physicians for intervention procedures, nonpharmacologic recommendations, and for more complex patients who may have required additional imaging or detailed physical evaluations. Pain CPSs documented CPRS notes with the SOAR template and discussed all recommendations with appropriate inpatient teams.

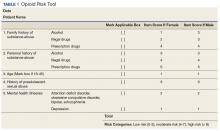

Respective providers received questionnaires hosted on SurveyMonkey.com (San Mateo, CA) to gauge their satisfaction with the IPPCS at the end of the pilot period, which helped determine program utility. Data collected for the pilot included patient demographics; patient admission diagnosis; consulting inpatient service; type of pain and reason for IPPCS request; total morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD); pertinent past medical history (ie, sleep apnea, psychiatric comorbidities, or substance use disorder [SUD]); ORT score; patients’ reported average pain severity on the 10-point Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS); number of requests submitted; medications discontinued, initiated, or dose increased/decreased; and number of pharmacist recommendations, including number accepted by providers. The ORT is a 5-item questionnaire used to determine risk of opioid-related aberrant behaviors in adults to help discriminate between low-risk and high-risk individuals (Table 1).17

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the results, and a Likert scale was used to evaluate responses the from provider satisfaction questionnaires. The IPPCS collected and organized the data using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Results

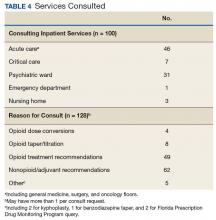

By the end of the pilot period in May 2016, the IPPCS had received 100 consult requests and completed 81% (Figure). The remaining consults included 11% forwarded to other disciplines. The service discontinued 8% of the requests, given patients’ hospital discharge prior to IPPCS review.

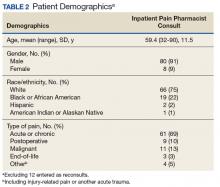

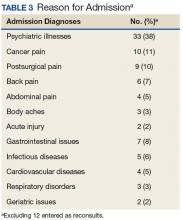

Baseline patient data are outlined in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. For each of the 100 consults, providers could select more than 1 reason for the request. The nonopioid/adjuvant treatment recommendations were the most common at 49% (62/128). Patients could have more than 1 pertinent medical comorbidity, with psychiatric illnesses the most prevalent at 68% (133/197). A mean ORT score of 8.1 indicated a high risk for opioid-related aberrant behavior. Overall, half the patients (37/73) were high risk, 25% (18/73) were medium risk (ORT 4-7), and 25% (18/73) were low risk (ORT 0-3). Patients’ reported average pain was often severe (NPRS 7-10) at 54% (40/74) or moderate (NPRS 4-6) at 39% (29/74).

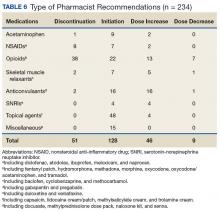

The IPPCS recommended various medications for initiation, discontinuation, or dosage changes (Table 6). For example, the IPPCS recommended initiation of topical agents in 38% (48/128) of cases. The inpatient pain CPS offered opioid initiation in 17% (22/128) of cases, with immediate-release oral morphine as the most predominant. Notably, opioids remained the most common medications suggested for discontinuation at 74% (38/51), including 47% (18/38) for IV hydromorphone. Dose titration recommendations mainly included anticonvulsants at 33% (16/48), and most dose reductions involved opioids at 78% (7/9), namely, oxycodone/acetaminophen and IV hydromorphone.

Providers accepted 76% (179/234) of IPPCS pharmacist medication recommendations. The most common included initiation/optimization of adjuvant therapy (eg, anticonvulsants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], and topical agents) at 46% (83/179), followed by opioid discontinuation (eg, IV hydromorphone) at 22% (40/179). Although this project primarily tracked medication interventions, examples of accepted nonpharmacologic recommendations included UDT and referrals to other programs (eg, pain psychology, substance abuse, mental health, acupuncture, chiropractor, PT/OT/PMR, and interventional pain management), which received support from each respective discipline. Declined pharmacologic recommendations mostly included topicals (eg, lidocaine, trolamine, and capsaicin cream) at 35% (19/55). However, findings also show that providers implemented 100% of medication recommendations in whole for 58% (47/81) of consults.

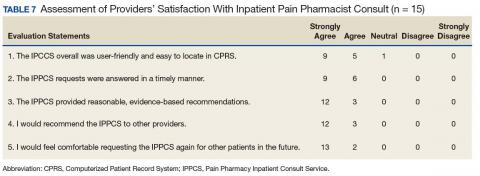

Likert scale satisfaction questionnaires offered insight into providers’ perception of the IPPCS (Table 7). One provider felt “neutral” about the consult submission process, given the time needed to complete the CPRS requests, but all other providers “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the IPPCS was user-friendly. More importantly, 100% (15/15) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the inpatient pain CPS answered consults promptly with reasonable, evidence-based recommendations. All respondents declared that they would recommend the IPPCS to other practitioners and felt comfortable entering requests for future patients.

Discussion

The IPPCS achieved a total of 100 consults, which served as the sample for the pilot program. With support from the OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy Department Administration, the IPPCS operated from November 2, 2015 through May 6, 2016. Results suggested that this new service could assist in managing inpatient pain issues in collaboration with inpatient multidisciplinary teams.

The most popular reason for IPPCS consults was acute on chronic pain. Given national efforts to improve opioid prescribing through the VA Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) and the 2016 CDC Guideline for Opioid Prescribing, most pain consults requested nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations.18,19 Despite the wide MEDD range in this sample, the median/mean generally remained below recommended limits per current guidelines.18,19 However, the small sample size and lack of patient diversity (mostly white male veterans) limited the generalizability to non-VA medical facilities. Veterans often experienced both chronic pain and psychiatric disturbances, which explained the significant number of underlying mental health comorbidities observed. This affirmed the close interrelationship between pain and psychiatric issues described in the literature.20

Providers’ acceptance of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment modalities supported a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and biopsychosocial approach to effective analgesic management. During this pilot, the most common pharmacy medication recommendations, namely, discontinuation of inappropriate opioids (eg, IV hydromorphone in patients who are controlled on and/or able to tolerate oral medications) and dose titration of adjuvant medications (eg, anticonvulsants for neuropathic pain), revealed that the IPPCS provided needed expertise and alternatives for complex pain patients. The IPPCS was well received, as inpatient providers accepted and implemented a large proportion of pharmacist recommendations. Despite risks of bias with a nonvalidated questionnaire, providers offered positive feedback. In the future, distributing satisfaction evaluations to patients also would provide more insight into how others perceived the IPPCS.

Limitations

Reasons for unaccepted recommendations included perceived limited effectiveness and/or feasibility of topical agents for acute pain, as providers seemed to favor systemic therapy for supposedly more immediate analgesia. Prescriber preference may explain why inpatient teams sometimes declined adjuvant therapy recommendations. However, the 2016 American Pain Society Guidelines on the Management of Postoperative Pain support a multimodal approach and confirm that adjuvants can reduce patients’ opioid requirements.21

Consulting teams did not execute some opioid recommendations, which may be due to various factors, including patient-related or provider-related factors in the inpatient vs outpatient setting. Lack of retrospective analysis for comparison of results pre- and post-IPPCS implementation also limited the outcomes. However, this project was piloted as a QI initiative after providers identified significant needs for inpatient pain management at the WPBVAMC. No retrospective analysis was undertaken, as this project analyzed only responses during the pilot program.

Other obstacles of the IPPCS included request appropriateness and triaging. The inpatient pain CPS deferred management of some consults to other disciplines (eg, gastroenterology) for more appropriate care. The IPPCS deferred certain cases of acute pancreatic pain or generalized abdominal pain for further workup to address patients’ underlying issues. The inpatient pain CPS relayed pertinent information regarding appropriate consults to inpatient teams. In the future, developing more specific inclusion/exclusion criteria and delivering provider education about proper IPPCS requests may resolve this issue.

Challenges with pain consults from inpatient psychiatry stemmed from patients’ skepticism and unwillingness to accept nonopioid/adjuvant therapies. Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders are often associated with SUDs and potentially opioid-related aberrant behavior. More than 40% of opioid-dependent individuals have comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.22 Poorly-managed pain also drives SUD, as 80% of these patients illegally obtain prescription opioids. Thus, undertreatment of pain may push individuals to secure pain medications from illegal/illicit sources to achieve analgesia.23 Following pain physician consultation, the IPPCS continued inpatient opioids for 12% (10/81) of patients with a SUD history, including 5 with postoperative pain or other acute processes, since patients were kept in a monitored health care environment. The remaining included 4 with malignant pain and 1 with end-of-life pain. Overall, the IPPCS recommended that inpatient teams discharge these patients on as little opioids as possible, as well as to make referrals to substance abuse programs when necessary. Effective pain management of patients with aberrant behavior requires a comprehensive interdisciplinary team approach. To mitigate risk, effectively treat pain, and maintain patient safety, clinicians must recognize biologic, chemical, social, and psychiatric aspects of substance abuse.21

Another limitation during this pilot was an inability to promptly assess the impact of recommendations, given limited opportunities to reevaluate patients. In the future, more dedicated time for the inpatient pain CPSs to respond to consults may allow for better follow-up rather than initial consults only. Providers sometimes discharged patients within 24 hours of submitting consults as well, which left no time for the inpatient pain CPS consultation. However, the IPPCS forwarded appropriate requests to pain CPS e-consult services for chart review recommendations. Encouraging providers to submit consults earlier in patients’ hospital admissions may help reduce the number of incomplete IPPCS requests. Although expanding service hours would require more dedicated CPS staffing resources, it is another option for quicker consult completion and prompt follow-up.

Future Directions

Future efforts to expand this project include ensuring patient safety through judicious opioid use. Smooth transitions of care will particularly help to improve the quality of pain management. Current WPBVAMC policies stated that the primary care provider (PCP) alone must agree to continue prescribing outpatient analgesic medications, including opioids, prescribed from the OCPC once patients return to Primary Care. Continued provider education would ideally promote efficient utilization of the IPPCS and OCPC.

The pain pharmacy SOAR note template also could undergo additional edits/revisions, including the addition of opioid overdose risk assessments. For improved documentation and standardization, the template could autopopulate patient-specific information when the inpatient pain CPS chooses the designated note title. The IPPCS also hoped to streamline the CPRS consult link for more convenience and ease of use. Ultimately, the IPPCS wished to provide ongoing provider education, inpatient opioid therapy, and other topics upon request.

Conclusion

The IPPCS received positive provider feedback and collected 100 consults (averaging 4 per week) during the 6-month pilot QI project. Most consults were for acute or chronic pain and requested nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations. The new service intended to fulfill unmet needs at the WPBVAMC by expanding the facility’s current pain programs. Prescribers reported a high level of satisfaction and a willingness to not only refer other clinicians to the program, but also continue using the consult. Providers unanimously agreed that the pain CPS provided reasonable, evidence-based recommendations. This project demonstrated that the IPPCS can aid in meeting new demands amid the challenging landscape of pain practice.

1. D’Arcy Y. Treating acute pain in the hospitalized patient. Nurse Pract. 2012;37(8):22-30.

2. Marks AD, Rodgers PE. Diagnosis and management of acute pain in the hospitalized patient. Am J Med. 2014;3(3):e396-e408.

3. Paice JA, Von Roenn JH. Under- or overtreatment of pain in the patient with cancer: how to achieve proper balance. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1721-1726.

4. Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573-1581.

5. Palomano RC, Rathmell JP, Krenzischek DA, Dunwoody CJ. Emerging trends and new approaches to acute pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(suppl 1):S43-S53.

6. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Facing addiction in America: the surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health, executive summary. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/executive-summary.pdf. Published November 2016. Accessed November 1, 2017.

7. Bagian JP, Cohen M, Barnsteiner JH, et al. Safe use of opioids in hospitals. Sentinel Event Alert. 2012;49:1-5.

8. Atkinson TJ, Gulum AH, Forkum WG. The future of pain pharmacy: directed by need. Integrated Pharm Res Pract. 2016;2016(5):33-42.

9. Lothian ST, Fotis MA, Von Gutten CF, et al. Cancer pain management through a pharmacist-based analgesic dosing service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1119-1125.

10. Lynn MA. Pharmacist interventions in pain management. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(14):1487-1489.

11. Strickland JM, Huskey A, Brushwood DB. Pharmacist-physician collaboration in pain management practice. J Opioid Manag. 2007;3(6):295-301.

12. Fan T and Elgourt T. Pain management pharmacy service in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(16):1560-1565.

13. Andrews LB, Bridgeman MB, Dalal KS, et al. Implementation of a pharmacist-directed pain management consultation service for hospitalised adults with a history of substance abuse. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(12):1342-1349.

14. Poirier RH, Brown CS, Garcia YT, Gann NY, Sandoval RA, McNulty JR. Implementation of a pharmacist directed pain management service in the inpatient setting. http://www.ashpadvantage.com/bestpractices/2014_papers/Kaweah-Delta.htm. Published 2014. Accessed November 1, 2017.

15. Langley GL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nded. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

16. Nahin, RL. Severe pain in veterans: the effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. J Pain. 2017;18(3):247-254.

17. Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432-442.

18. Nazario M. Opioid therapy risk management: the VA opioid safety and naloxone distribution initiatives. http://jfpsmeeting.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/slides/Opioid%20Therapy%20Risk%20Management.pdf. Published October 15, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2017.

19. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. MMWR Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49.

20. Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, et al. Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. J Behav Med. 2015;38:535.

21. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157.

22. NIDA/SAMHSA Blending Initiative. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidasamhsa-blending-initiative. Updated November 2015. Accessed November 1, 2017.

23. Alford DP, German JS, Samet JH, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini CA, Saitz R. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):486-491.

The term pain refers to unpleasant sensory, emotional experiences associated with actual or potential tissue damage and is described in terms of such damage.1 Acute pain from neurophysiologic responses to noxious stimuli resolves upon tissue healing or stimuli removal (eg, 3-6 months); however, chronic pain lingers beyond the expected time course of the acute injury and repair process.1,2 Despite pain management advances, the under- or overtreatment of pain for different patient populations (eg, cancer and noncancer) remains an important concern.3,4

Hospitals have focused on optimizing inpatient pain management, because uncontrolled pain remains the most common reason for readmissions the first week postsurgery.5 The safe use of opioids (prescription, illicit synthetic, or heroin) poses major challenges and raises significant concerns. Rates of opioid-related hospital admissions have increased by 42% since 2009, and total overdose deaths reached a new high of 47,055 in 2014, including 28,647 (61%) from opioids.6

Opioids rank among the medications most often associated with serious adverse events (AEs), including respiratory depression and death.7 In response, the Joint Commission recommends patient assessments for opioid-related AEs, technology to monitor opioid prescribing, pharmacist consultation for opioid conversions and route of administration changes, provider education about risks of opioids, and risk screening tools for opioid-related oversedation and respiratory depression.7 Treatment guidelines strive to minimize the impact of acute pain by offering a scientific basis for practice, but evidence suggests a lack of suitable pain programs.7 Increases in opioid prescribing along with clinical guidelines and state laws recommending specialty pain service referrals for patients on high-dose opioids, have increased demand for competent pain clinicians.8

The expertise of a clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS) can help refine ineffective and potentially harmful pain medication therapy in complex patient cases. Existing literature outlines the various benefits of pharmacist participation in collaborative pain services for cancer and noncancer pain, as well as cases involving substance abuse.9-13 Various articles support pharmacists’ role as an educator and team member who can add valuable, trustworthy clinical knowledge that enhances clinical encounters and guides protocol/policy development.12,13 These efforts have improved patient satisfaction and encouraged physicians and nurses to proactively seek pharmacists’ advice for difficult cases.9

Frequent communication with interdisciplinary teams have helped considerably in establishing clinical pharmacy services that benefit patient care and offer sources of professional accomplishment.10,11 For example, pharmacists at Kaweah Delta Medical Center in Visalia, CA launched an innovative pain program that encompassed consultations and opioid stewardship, which demonstrated that pharmacists can improve patient outcomes in the front lines of pain management.14 Pain CPSs have advanced knowledge of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and therapeutics to promote safe and effective analgesic use, as well as to identify opioid use disorders. Evidence suggests that pharmacists’ presence on interdisciplinary pain teams improves outcomes by optimizing medication selection, improving adherence, and preventing AEs.8

Following the plan-do-study-act model for quality improvement (QI), this project hoped to expand current pain programs at the West Palm Beach VAMC (WPBVAMC) by evaluating the feasibility of an inpatient pain pharmacist consult service (IPPCS) at the 301-bed teaching facility, which includes 130 acute/intensive care and 120 nursing/domiciliary beds.15 Staff provide primary- and secondary-level care to veterans in 7 counties along Florida’s southeastern coast.

In 2009, the WPBVAMC PGY-2 Pain Management and Palliative Care Program became the VA’s first accredited pain pharmacy residency. Residents train with the Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation (PMR) and Chronic Pain Management departments, which provide outpatient services from 7 pain physicians, a pain psychologist, registered nurse, chiropractor, acupuncturist, physical/occupational therapy (PT/OT), and 3 pain/palliative care CPSs.

The WPBVAMC had established interdisciplinary outpatient chronic pain clinic (OCPC) physician- and pharmacist-run services along with a pain CPS electronic consult (e-consult) program. However, no formal mechanisms for inpatient pain consultations existed. Prior to the IPPCS outlined in this study, OCPC practitioners, including 2 pain CPSs, managed impromptu inpatient pain issues as “curbside consultations” along with usual day-to-day clinic duties.

The OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy administration recognized the need for more clinical support to manage complex analgesic issues in inpatient veterans, as these patients often have acute pain with underlying chronic pain syndromes. In a national survey, veterans were significantly more likely than were nonveterans to report painful health conditions (65.5% vs 56.4%) and to classify their pain as severe (9.1% vs 6.3%).16 The WPBVAMC administration concluded that an IPPCS would offer a more efficient means of handling such cases. The IPPCS would formally streamline inpatient pain consults, enabling CPSs to thoroughly evaluate pain-related issues to propose evidence-based recommendations.

The primary objective of this QI project was to assess the IPPCS implementation as part of multimodal care to satisfy unmet patient care needs at the WPBVAMC. Secondary objectives for program feasibility included identifying the volume and type of pain consults, categorizing pharmacist interventions, classifying providers’ satisfaction, and determining types of responses to pharmacists’ medication recommendations.

Methods

This QI project ascertained the feasibility of the IPPCS by evaluating all consults obtained during the pilot period from November 2, 2015 through May 6, 2016. The IPPCS was accessible Monday through Friday during normal business hours. Goal turnaround time for consult completion was 24 to 72 hours, given the lack of coverage on holidays and weekends. The target population included veterans hospitalized at the WPBVAMC inpatient ward or nursing home with uncontrolled pain on IV and/or oral analgesic medications. All IPPCS consults submitted during the pilot period were included in the sample.

The WPBVAMC Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) approved this QI program prior to initiation. Following supervisory support from the OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy departments, hospital technologists assisted in creating a consult link in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which allowed providers to submit IPPCS requests for specific patients efficiently. Consults were categorized as postoperative pain, acute or chronic pain, malignant pain, or end-of-life pain. Inpatient providers could enter requests for assistance with 1 or more of the following: opioid dose conversions, opioid taper/titration schedules, general opioid treatment recommendations, or nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations.

The Medical Records Committee approved a customized CPRS subjective-objective-assessment-recommendations (SOAR) note template, which helped standardize the pain CPS documentation. To promote consult requests and interdisciplinary collaboration, inpatient clinicians received education about the IPPCS at respective meetings (eg, General Medicine staff and Clinical Pharmacy meetings).

All CPSs involved in this project were residency-trained in direct patient care, including pain and palliative care, and maintained national board certification as pharmacotherapy specialists. Their role included reviewing patients’ electronic medical records, conducting face-to-face pain assessments, completing opioid risk assessments, evaluating analgesic regimen appropriateness, reviewing medication adherence, completing pain medication reconciliation, querying the Florida Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), interpreting urine drug testing (UDT), and delivering provider/patient/caregiver education. Parameters used to determine the appropriateness of analgesic regimens included, but were not limited to:

- Use of oral instead of IV medications if oral dosing was feasible/possible/appropriate;

- Dose and adjustments per renal/hepatic function;

- Adequate treatment duration and titration;

- No therapeutic drug class duplications;

- Medication tolerability (eg, allergies, AEs, drug interactions); and

- Opioid risk assessment per Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) score and medical history.

Consulting providers clarified patients’ pain diagnoses prior to pharmacy consultations.

After face-to-face patient interviews, the inpatient pain CPS prepared pain management recommendations, including nonopioid/adjuvant pain medications and/or opioid dose adjustments. The IPPCS also collaborated with pain physicians for intervention procedures, nonpharmacologic recommendations, and for more complex patients who may have required additional imaging or detailed physical evaluations. Pain CPSs documented CPRS notes with the SOAR template and discussed all recommendations with appropriate inpatient teams.

Respective providers received questionnaires hosted on SurveyMonkey.com (San Mateo, CA) to gauge their satisfaction with the IPPCS at the end of the pilot period, which helped determine program utility. Data collected for the pilot included patient demographics; patient admission diagnosis; consulting inpatient service; type of pain and reason for IPPCS request; total morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD); pertinent past medical history (ie, sleep apnea, psychiatric comorbidities, or substance use disorder [SUD]); ORT score; patients’ reported average pain severity on the 10-point Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS); number of requests submitted; medications discontinued, initiated, or dose increased/decreased; and number of pharmacist recommendations, including number accepted by providers. The ORT is a 5-item questionnaire used to determine risk of opioid-related aberrant behaviors in adults to help discriminate between low-risk and high-risk individuals (Table 1).17

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the results, and a Likert scale was used to evaluate responses the from provider satisfaction questionnaires. The IPPCS collected and organized the data using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Results

By the end of the pilot period in May 2016, the IPPCS had received 100 consult requests and completed 81% (Figure). The remaining consults included 11% forwarded to other disciplines. The service discontinued 8% of the requests, given patients’ hospital discharge prior to IPPCS review.

Baseline patient data are outlined in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. For each of the 100 consults, providers could select more than 1 reason for the request. The nonopioid/adjuvant treatment recommendations were the most common at 49% (62/128). Patients could have more than 1 pertinent medical comorbidity, with psychiatric illnesses the most prevalent at 68% (133/197). A mean ORT score of 8.1 indicated a high risk for opioid-related aberrant behavior. Overall, half the patients (37/73) were high risk, 25% (18/73) were medium risk (ORT 4-7), and 25% (18/73) were low risk (ORT 0-3). Patients’ reported average pain was often severe (NPRS 7-10) at 54% (40/74) or moderate (NPRS 4-6) at 39% (29/74).

The IPPCS recommended various medications for initiation, discontinuation, or dosage changes (Table 6). For example, the IPPCS recommended initiation of topical agents in 38% (48/128) of cases. The inpatient pain CPS offered opioid initiation in 17% (22/128) of cases, with immediate-release oral morphine as the most predominant. Notably, opioids remained the most common medications suggested for discontinuation at 74% (38/51), including 47% (18/38) for IV hydromorphone. Dose titration recommendations mainly included anticonvulsants at 33% (16/48), and most dose reductions involved opioids at 78% (7/9), namely, oxycodone/acetaminophen and IV hydromorphone.

Providers accepted 76% (179/234) of IPPCS pharmacist medication recommendations. The most common included initiation/optimization of adjuvant therapy (eg, anticonvulsants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], and topical agents) at 46% (83/179), followed by opioid discontinuation (eg, IV hydromorphone) at 22% (40/179). Although this project primarily tracked medication interventions, examples of accepted nonpharmacologic recommendations included UDT and referrals to other programs (eg, pain psychology, substance abuse, mental health, acupuncture, chiropractor, PT/OT/PMR, and interventional pain management), which received support from each respective discipline. Declined pharmacologic recommendations mostly included topicals (eg, lidocaine, trolamine, and capsaicin cream) at 35% (19/55). However, findings also show that providers implemented 100% of medication recommendations in whole for 58% (47/81) of consults.

Likert scale satisfaction questionnaires offered insight into providers’ perception of the IPPCS (Table 7). One provider felt “neutral” about the consult submission process, given the time needed to complete the CPRS requests, but all other providers “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the IPPCS was user-friendly. More importantly, 100% (15/15) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the inpatient pain CPS answered consults promptly with reasonable, evidence-based recommendations. All respondents declared that they would recommend the IPPCS to other practitioners and felt comfortable entering requests for future patients.

Discussion

The IPPCS achieved a total of 100 consults, which served as the sample for the pilot program. With support from the OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy Department Administration, the IPPCS operated from November 2, 2015 through May 6, 2016. Results suggested that this new service could assist in managing inpatient pain issues in collaboration with inpatient multidisciplinary teams.

The most popular reason for IPPCS consults was acute on chronic pain. Given national efforts to improve opioid prescribing through the VA Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) and the 2016 CDC Guideline for Opioid Prescribing, most pain consults requested nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations.18,19 Despite the wide MEDD range in this sample, the median/mean generally remained below recommended limits per current guidelines.18,19 However, the small sample size and lack of patient diversity (mostly white male veterans) limited the generalizability to non-VA medical facilities. Veterans often experienced both chronic pain and psychiatric disturbances, which explained the significant number of underlying mental health comorbidities observed. This affirmed the close interrelationship between pain and psychiatric issues described in the literature.20

Providers’ acceptance of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment modalities supported a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and biopsychosocial approach to effective analgesic management. During this pilot, the most common pharmacy medication recommendations, namely, discontinuation of inappropriate opioids (eg, IV hydromorphone in patients who are controlled on and/or able to tolerate oral medications) and dose titration of adjuvant medications (eg, anticonvulsants for neuropathic pain), revealed that the IPPCS provided needed expertise and alternatives for complex pain patients. The IPPCS was well received, as inpatient providers accepted and implemented a large proportion of pharmacist recommendations. Despite risks of bias with a nonvalidated questionnaire, providers offered positive feedback. In the future, distributing satisfaction evaluations to patients also would provide more insight into how others perceived the IPPCS.

Limitations

Reasons for unaccepted recommendations included perceived limited effectiveness and/or feasibility of topical agents for acute pain, as providers seemed to favor systemic therapy for supposedly more immediate analgesia. Prescriber preference may explain why inpatient teams sometimes declined adjuvant therapy recommendations. However, the 2016 American Pain Society Guidelines on the Management of Postoperative Pain support a multimodal approach and confirm that adjuvants can reduce patients’ opioid requirements.21

Consulting teams did not execute some opioid recommendations, which may be due to various factors, including patient-related or provider-related factors in the inpatient vs outpatient setting. Lack of retrospective analysis for comparison of results pre- and post-IPPCS implementation also limited the outcomes. However, this project was piloted as a QI initiative after providers identified significant needs for inpatient pain management at the WPBVAMC. No retrospective analysis was undertaken, as this project analyzed only responses during the pilot program.

Other obstacles of the IPPCS included request appropriateness and triaging. The inpatient pain CPS deferred management of some consults to other disciplines (eg, gastroenterology) for more appropriate care. The IPPCS deferred certain cases of acute pancreatic pain or generalized abdominal pain for further workup to address patients’ underlying issues. The inpatient pain CPS relayed pertinent information regarding appropriate consults to inpatient teams. In the future, developing more specific inclusion/exclusion criteria and delivering provider education about proper IPPCS requests may resolve this issue.

Challenges with pain consults from inpatient psychiatry stemmed from patients’ skepticism and unwillingness to accept nonopioid/adjuvant therapies. Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders are often associated with SUDs and potentially opioid-related aberrant behavior. More than 40% of opioid-dependent individuals have comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.22 Poorly-managed pain also drives SUD, as 80% of these patients illegally obtain prescription opioids. Thus, undertreatment of pain may push individuals to secure pain medications from illegal/illicit sources to achieve analgesia.23 Following pain physician consultation, the IPPCS continued inpatient opioids for 12% (10/81) of patients with a SUD history, including 5 with postoperative pain or other acute processes, since patients were kept in a monitored health care environment. The remaining included 4 with malignant pain and 1 with end-of-life pain. Overall, the IPPCS recommended that inpatient teams discharge these patients on as little opioids as possible, as well as to make referrals to substance abuse programs when necessary. Effective pain management of patients with aberrant behavior requires a comprehensive interdisciplinary team approach. To mitigate risk, effectively treat pain, and maintain patient safety, clinicians must recognize biologic, chemical, social, and psychiatric aspects of substance abuse.21

Another limitation during this pilot was an inability to promptly assess the impact of recommendations, given limited opportunities to reevaluate patients. In the future, more dedicated time for the inpatient pain CPSs to respond to consults may allow for better follow-up rather than initial consults only. Providers sometimes discharged patients within 24 hours of submitting consults as well, which left no time for the inpatient pain CPS consultation. However, the IPPCS forwarded appropriate requests to pain CPS e-consult services for chart review recommendations. Encouraging providers to submit consults earlier in patients’ hospital admissions may help reduce the number of incomplete IPPCS requests. Although expanding service hours would require more dedicated CPS staffing resources, it is another option for quicker consult completion and prompt follow-up.

Future Directions

Future efforts to expand this project include ensuring patient safety through judicious opioid use. Smooth transitions of care will particularly help to improve the quality of pain management. Current WPBVAMC policies stated that the primary care provider (PCP) alone must agree to continue prescribing outpatient analgesic medications, including opioids, prescribed from the OCPC once patients return to Primary Care. Continued provider education would ideally promote efficient utilization of the IPPCS and OCPC.

The pain pharmacy SOAR note template also could undergo additional edits/revisions, including the addition of opioid overdose risk assessments. For improved documentation and standardization, the template could autopopulate patient-specific information when the inpatient pain CPS chooses the designated note title. The IPPCS also hoped to streamline the CPRS consult link for more convenience and ease of use. Ultimately, the IPPCS wished to provide ongoing provider education, inpatient opioid therapy, and other topics upon request.

Conclusion

The IPPCS received positive provider feedback and collected 100 consults (averaging 4 per week) during the 6-month pilot QI project. Most consults were for acute or chronic pain and requested nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations. The new service intended to fulfill unmet needs at the WPBVAMC by expanding the facility’s current pain programs. Prescribers reported a high level of satisfaction and a willingness to not only refer other clinicians to the program, but also continue using the consult. Providers unanimously agreed that the pain CPS provided reasonable, evidence-based recommendations. This project demonstrated that the IPPCS can aid in meeting new demands amid the challenging landscape of pain practice.

The term pain refers to unpleasant sensory, emotional experiences associated with actual or potential tissue damage and is described in terms of such damage.1 Acute pain from neurophysiologic responses to noxious stimuli resolves upon tissue healing or stimuli removal (eg, 3-6 months); however, chronic pain lingers beyond the expected time course of the acute injury and repair process.1,2 Despite pain management advances, the under- or overtreatment of pain for different patient populations (eg, cancer and noncancer) remains an important concern.3,4

Hospitals have focused on optimizing inpatient pain management, because uncontrolled pain remains the most common reason for readmissions the first week postsurgery.5 The safe use of opioids (prescription, illicit synthetic, or heroin) poses major challenges and raises significant concerns. Rates of opioid-related hospital admissions have increased by 42% since 2009, and total overdose deaths reached a new high of 47,055 in 2014, including 28,647 (61%) from opioids.6

Opioids rank among the medications most often associated with serious adverse events (AEs), including respiratory depression and death.7 In response, the Joint Commission recommends patient assessments for opioid-related AEs, technology to monitor opioid prescribing, pharmacist consultation for opioid conversions and route of administration changes, provider education about risks of opioids, and risk screening tools for opioid-related oversedation and respiratory depression.7 Treatment guidelines strive to minimize the impact of acute pain by offering a scientific basis for practice, but evidence suggests a lack of suitable pain programs.7 Increases in opioid prescribing along with clinical guidelines and state laws recommending specialty pain service referrals for patients on high-dose opioids, have increased demand for competent pain clinicians.8

The expertise of a clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS) can help refine ineffective and potentially harmful pain medication therapy in complex patient cases. Existing literature outlines the various benefits of pharmacist participation in collaborative pain services for cancer and noncancer pain, as well as cases involving substance abuse.9-13 Various articles support pharmacists’ role as an educator and team member who can add valuable, trustworthy clinical knowledge that enhances clinical encounters and guides protocol/policy development.12,13 These efforts have improved patient satisfaction and encouraged physicians and nurses to proactively seek pharmacists’ advice for difficult cases.9

Frequent communication with interdisciplinary teams have helped considerably in establishing clinical pharmacy services that benefit patient care and offer sources of professional accomplishment.10,11 For example, pharmacists at Kaweah Delta Medical Center in Visalia, CA launched an innovative pain program that encompassed consultations and opioid stewardship, which demonstrated that pharmacists can improve patient outcomes in the front lines of pain management.14 Pain CPSs have advanced knowledge of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and therapeutics to promote safe and effective analgesic use, as well as to identify opioid use disorders. Evidence suggests that pharmacists’ presence on interdisciplinary pain teams improves outcomes by optimizing medication selection, improving adherence, and preventing AEs.8

Following the plan-do-study-act model for quality improvement (QI), this project hoped to expand current pain programs at the West Palm Beach VAMC (WPBVAMC) by evaluating the feasibility of an inpatient pain pharmacist consult service (IPPCS) at the 301-bed teaching facility, which includes 130 acute/intensive care and 120 nursing/domiciliary beds.15 Staff provide primary- and secondary-level care to veterans in 7 counties along Florida’s southeastern coast.

In 2009, the WPBVAMC PGY-2 Pain Management and Palliative Care Program became the VA’s first accredited pain pharmacy residency. Residents train with the Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation (PMR) and Chronic Pain Management departments, which provide outpatient services from 7 pain physicians, a pain psychologist, registered nurse, chiropractor, acupuncturist, physical/occupational therapy (PT/OT), and 3 pain/palliative care CPSs.

The WPBVAMC had established interdisciplinary outpatient chronic pain clinic (OCPC) physician- and pharmacist-run services along with a pain CPS electronic consult (e-consult) program. However, no formal mechanisms for inpatient pain consultations existed. Prior to the IPPCS outlined in this study, OCPC practitioners, including 2 pain CPSs, managed impromptu inpatient pain issues as “curbside consultations” along with usual day-to-day clinic duties.

The OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy administration recognized the need for more clinical support to manage complex analgesic issues in inpatient veterans, as these patients often have acute pain with underlying chronic pain syndromes. In a national survey, veterans were significantly more likely than were nonveterans to report painful health conditions (65.5% vs 56.4%) and to classify their pain as severe (9.1% vs 6.3%).16 The WPBVAMC administration concluded that an IPPCS would offer a more efficient means of handling such cases. The IPPCS would formally streamline inpatient pain consults, enabling CPSs to thoroughly evaluate pain-related issues to propose evidence-based recommendations.

The primary objective of this QI project was to assess the IPPCS implementation as part of multimodal care to satisfy unmet patient care needs at the WPBVAMC. Secondary objectives for program feasibility included identifying the volume and type of pain consults, categorizing pharmacist interventions, classifying providers’ satisfaction, and determining types of responses to pharmacists’ medication recommendations.

Methods

This QI project ascertained the feasibility of the IPPCS by evaluating all consults obtained during the pilot period from November 2, 2015 through May 6, 2016. The IPPCS was accessible Monday through Friday during normal business hours. Goal turnaround time for consult completion was 24 to 72 hours, given the lack of coverage on holidays and weekends. The target population included veterans hospitalized at the WPBVAMC inpatient ward or nursing home with uncontrolled pain on IV and/or oral analgesic medications. All IPPCS consults submitted during the pilot period were included in the sample.

The WPBVAMC Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) approved this QI program prior to initiation. Following supervisory support from the OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy departments, hospital technologists assisted in creating a consult link in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which allowed providers to submit IPPCS requests for specific patients efficiently. Consults were categorized as postoperative pain, acute or chronic pain, malignant pain, or end-of-life pain. Inpatient providers could enter requests for assistance with 1 or more of the following: opioid dose conversions, opioid taper/titration schedules, general opioid treatment recommendations, or nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations.

The Medical Records Committee approved a customized CPRS subjective-objective-assessment-recommendations (SOAR) note template, which helped standardize the pain CPS documentation. To promote consult requests and interdisciplinary collaboration, inpatient clinicians received education about the IPPCS at respective meetings (eg, General Medicine staff and Clinical Pharmacy meetings).

All CPSs involved in this project were residency-trained in direct patient care, including pain and palliative care, and maintained national board certification as pharmacotherapy specialists. Their role included reviewing patients’ electronic medical records, conducting face-to-face pain assessments, completing opioid risk assessments, evaluating analgesic regimen appropriateness, reviewing medication adherence, completing pain medication reconciliation, querying the Florida Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), interpreting urine drug testing (UDT), and delivering provider/patient/caregiver education. Parameters used to determine the appropriateness of analgesic regimens included, but were not limited to:

- Use of oral instead of IV medications if oral dosing was feasible/possible/appropriate;

- Dose and adjustments per renal/hepatic function;

- Adequate treatment duration and titration;

- No therapeutic drug class duplications;

- Medication tolerability (eg, allergies, AEs, drug interactions); and

- Opioid risk assessment per Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) score and medical history.

Consulting providers clarified patients’ pain diagnoses prior to pharmacy consultations.

After face-to-face patient interviews, the inpatient pain CPS prepared pain management recommendations, including nonopioid/adjuvant pain medications and/or opioid dose adjustments. The IPPCS also collaborated with pain physicians for intervention procedures, nonpharmacologic recommendations, and for more complex patients who may have required additional imaging or detailed physical evaluations. Pain CPSs documented CPRS notes with the SOAR template and discussed all recommendations with appropriate inpatient teams.

Respective providers received questionnaires hosted on SurveyMonkey.com (San Mateo, CA) to gauge their satisfaction with the IPPCS at the end of the pilot period, which helped determine program utility. Data collected for the pilot included patient demographics; patient admission diagnosis; consulting inpatient service; type of pain and reason for IPPCS request; total morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD); pertinent past medical history (ie, sleep apnea, psychiatric comorbidities, or substance use disorder [SUD]); ORT score; patients’ reported average pain severity on the 10-point Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS); number of requests submitted; medications discontinued, initiated, or dose increased/decreased; and number of pharmacist recommendations, including number accepted by providers. The ORT is a 5-item questionnaire used to determine risk of opioid-related aberrant behaviors in adults to help discriminate between low-risk and high-risk individuals (Table 1).17

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the results, and a Likert scale was used to evaluate responses the from provider satisfaction questionnaires. The IPPCS collected and organized the data using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Results

By the end of the pilot period in May 2016, the IPPCS had received 100 consult requests and completed 81% (Figure). The remaining consults included 11% forwarded to other disciplines. The service discontinued 8% of the requests, given patients’ hospital discharge prior to IPPCS review.

Baseline patient data are outlined in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. For each of the 100 consults, providers could select more than 1 reason for the request. The nonopioid/adjuvant treatment recommendations were the most common at 49% (62/128). Patients could have more than 1 pertinent medical comorbidity, with psychiatric illnesses the most prevalent at 68% (133/197). A mean ORT score of 8.1 indicated a high risk for opioid-related aberrant behavior. Overall, half the patients (37/73) were high risk, 25% (18/73) were medium risk (ORT 4-7), and 25% (18/73) were low risk (ORT 0-3). Patients’ reported average pain was often severe (NPRS 7-10) at 54% (40/74) or moderate (NPRS 4-6) at 39% (29/74).

The IPPCS recommended various medications for initiation, discontinuation, or dosage changes (Table 6). For example, the IPPCS recommended initiation of topical agents in 38% (48/128) of cases. The inpatient pain CPS offered opioid initiation in 17% (22/128) of cases, with immediate-release oral morphine as the most predominant. Notably, opioids remained the most common medications suggested for discontinuation at 74% (38/51), including 47% (18/38) for IV hydromorphone. Dose titration recommendations mainly included anticonvulsants at 33% (16/48), and most dose reductions involved opioids at 78% (7/9), namely, oxycodone/acetaminophen and IV hydromorphone.

Providers accepted 76% (179/234) of IPPCS pharmacist medication recommendations. The most common included initiation/optimization of adjuvant therapy (eg, anticonvulsants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], and topical agents) at 46% (83/179), followed by opioid discontinuation (eg, IV hydromorphone) at 22% (40/179). Although this project primarily tracked medication interventions, examples of accepted nonpharmacologic recommendations included UDT and referrals to other programs (eg, pain psychology, substance abuse, mental health, acupuncture, chiropractor, PT/OT/PMR, and interventional pain management), which received support from each respective discipline. Declined pharmacologic recommendations mostly included topicals (eg, lidocaine, trolamine, and capsaicin cream) at 35% (19/55). However, findings also show that providers implemented 100% of medication recommendations in whole for 58% (47/81) of consults.

Likert scale satisfaction questionnaires offered insight into providers’ perception of the IPPCS (Table 7). One provider felt “neutral” about the consult submission process, given the time needed to complete the CPRS requests, but all other providers “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the IPPCS was user-friendly. More importantly, 100% (15/15) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the inpatient pain CPS answered consults promptly with reasonable, evidence-based recommendations. All respondents declared that they would recommend the IPPCS to other practitioners and felt comfortable entering requests for future patients.

Discussion

The IPPCS achieved a total of 100 consults, which served as the sample for the pilot program. With support from the OCPC, PMR, and Clinical Pharmacy Department Administration, the IPPCS operated from November 2, 2015 through May 6, 2016. Results suggested that this new service could assist in managing inpatient pain issues in collaboration with inpatient multidisciplinary teams.

The most popular reason for IPPCS consults was acute on chronic pain. Given national efforts to improve opioid prescribing through the VA Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) and the 2016 CDC Guideline for Opioid Prescribing, most pain consults requested nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations.18,19 Despite the wide MEDD range in this sample, the median/mean generally remained below recommended limits per current guidelines.18,19 However, the small sample size and lack of patient diversity (mostly white male veterans) limited the generalizability to non-VA medical facilities. Veterans often experienced both chronic pain and psychiatric disturbances, which explained the significant number of underlying mental health comorbidities observed. This affirmed the close interrelationship between pain and psychiatric issues described in the literature.20

Providers’ acceptance of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment modalities supported a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and biopsychosocial approach to effective analgesic management. During this pilot, the most common pharmacy medication recommendations, namely, discontinuation of inappropriate opioids (eg, IV hydromorphone in patients who are controlled on and/or able to tolerate oral medications) and dose titration of adjuvant medications (eg, anticonvulsants for neuropathic pain), revealed that the IPPCS provided needed expertise and alternatives for complex pain patients. The IPPCS was well received, as inpatient providers accepted and implemented a large proportion of pharmacist recommendations. Despite risks of bias with a nonvalidated questionnaire, providers offered positive feedback. In the future, distributing satisfaction evaluations to patients also would provide more insight into how others perceived the IPPCS.

Limitations

Reasons for unaccepted recommendations included perceived limited effectiveness and/or feasibility of topical agents for acute pain, as providers seemed to favor systemic therapy for supposedly more immediate analgesia. Prescriber preference may explain why inpatient teams sometimes declined adjuvant therapy recommendations. However, the 2016 American Pain Society Guidelines on the Management of Postoperative Pain support a multimodal approach and confirm that adjuvants can reduce patients’ opioid requirements.21

Consulting teams did not execute some opioid recommendations, which may be due to various factors, including patient-related or provider-related factors in the inpatient vs outpatient setting. Lack of retrospective analysis for comparison of results pre- and post-IPPCS implementation also limited the outcomes. However, this project was piloted as a QI initiative after providers identified significant needs for inpatient pain management at the WPBVAMC. No retrospective analysis was undertaken, as this project analyzed only responses during the pilot program.

Other obstacles of the IPPCS included request appropriateness and triaging. The inpatient pain CPS deferred management of some consults to other disciplines (eg, gastroenterology) for more appropriate care. The IPPCS deferred certain cases of acute pancreatic pain or generalized abdominal pain for further workup to address patients’ underlying issues. The inpatient pain CPS relayed pertinent information regarding appropriate consults to inpatient teams. In the future, developing more specific inclusion/exclusion criteria and delivering provider education about proper IPPCS requests may resolve this issue.

Challenges with pain consults from inpatient psychiatry stemmed from patients’ skepticism and unwillingness to accept nonopioid/adjuvant therapies. Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders are often associated with SUDs and potentially opioid-related aberrant behavior. More than 40% of opioid-dependent individuals have comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.22 Poorly-managed pain also drives SUD, as 80% of these patients illegally obtain prescription opioids. Thus, undertreatment of pain may push individuals to secure pain medications from illegal/illicit sources to achieve analgesia.23 Following pain physician consultation, the IPPCS continued inpatient opioids for 12% (10/81) of patients with a SUD history, including 5 with postoperative pain or other acute processes, since patients were kept in a monitored health care environment. The remaining included 4 with malignant pain and 1 with end-of-life pain. Overall, the IPPCS recommended that inpatient teams discharge these patients on as little opioids as possible, as well as to make referrals to substance abuse programs when necessary. Effective pain management of patients with aberrant behavior requires a comprehensive interdisciplinary team approach. To mitigate risk, effectively treat pain, and maintain patient safety, clinicians must recognize biologic, chemical, social, and psychiatric aspects of substance abuse.21

Another limitation during this pilot was an inability to promptly assess the impact of recommendations, given limited opportunities to reevaluate patients. In the future, more dedicated time for the inpatient pain CPSs to respond to consults may allow for better follow-up rather than initial consults only. Providers sometimes discharged patients within 24 hours of submitting consults as well, which left no time for the inpatient pain CPS consultation. However, the IPPCS forwarded appropriate requests to pain CPS e-consult services for chart review recommendations. Encouraging providers to submit consults earlier in patients’ hospital admissions may help reduce the number of incomplete IPPCS requests. Although expanding service hours would require more dedicated CPS staffing resources, it is another option for quicker consult completion and prompt follow-up.

Future Directions

Future efforts to expand this project include ensuring patient safety through judicious opioid use. Smooth transitions of care will particularly help to improve the quality of pain management. Current WPBVAMC policies stated that the primary care provider (PCP) alone must agree to continue prescribing outpatient analgesic medications, including opioids, prescribed from the OCPC once patients return to Primary Care. Continued provider education would ideally promote efficient utilization of the IPPCS and OCPC.

The pain pharmacy SOAR note template also could undergo additional edits/revisions, including the addition of opioid overdose risk assessments. For improved documentation and standardization, the template could autopopulate patient-specific information when the inpatient pain CPS chooses the designated note title. The IPPCS also hoped to streamline the CPRS consult link for more convenience and ease of use. Ultimately, the IPPCS wished to provide ongoing provider education, inpatient opioid therapy, and other topics upon request.

Conclusion

The IPPCS received positive provider feedback and collected 100 consults (averaging 4 per week) during the 6-month pilot QI project. Most consults were for acute or chronic pain and requested nonopioid/adjuvant recommendations. The new service intended to fulfill unmet needs at the WPBVAMC by expanding the facility’s current pain programs. Prescribers reported a high level of satisfaction and a willingness to not only refer other clinicians to the program, but also continue using the consult. Providers unanimously agreed that the pain CPS provided reasonable, evidence-based recommendations. This project demonstrated that the IPPCS can aid in meeting new demands amid the challenging landscape of pain practice.

1. D’Arcy Y. Treating acute pain in the hospitalized patient. Nurse Pract. 2012;37(8):22-30.

2. Marks AD, Rodgers PE. Diagnosis and management of acute pain in the hospitalized patient. Am J Med. 2014;3(3):e396-e408.

3. Paice JA, Von Roenn JH. Under- or overtreatment of pain in the patient with cancer: how to achieve proper balance. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1721-1726.

4. Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573-1581.

5. Palomano RC, Rathmell JP, Krenzischek DA, Dunwoody CJ. Emerging trends and new approaches to acute pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(suppl 1):S43-S53.

6. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Facing addiction in America: the surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health, executive summary. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/executive-summary.pdf. Published November 2016. Accessed November 1, 2017.

7. Bagian JP, Cohen M, Barnsteiner JH, et al. Safe use of opioids in hospitals. Sentinel Event Alert. 2012;49:1-5.

8. Atkinson TJ, Gulum AH, Forkum WG. The future of pain pharmacy: directed by need. Integrated Pharm Res Pract. 2016;2016(5):33-42.

9. Lothian ST, Fotis MA, Von Gutten CF, et al. Cancer pain management through a pharmacist-based analgesic dosing service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1119-1125.

10. Lynn MA. Pharmacist interventions in pain management. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(14):1487-1489.

11. Strickland JM, Huskey A, Brushwood DB. Pharmacist-physician collaboration in pain management practice. J Opioid Manag. 2007;3(6):295-301.

12. Fan T and Elgourt T. Pain management pharmacy service in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(16):1560-1565.

13. Andrews LB, Bridgeman MB, Dalal KS, et al. Implementation of a pharmacist-directed pain management consultation service for hospitalised adults with a history of substance abuse. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(12):1342-1349.

14. Poirier RH, Brown CS, Garcia YT, Gann NY, Sandoval RA, McNulty JR. Implementation of a pharmacist directed pain management service in the inpatient setting. http://www.ashpadvantage.com/bestpractices/2014_papers/Kaweah-Delta.htm. Published 2014. Accessed November 1, 2017.

15. Langley GL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nded. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

16. Nahin, RL. Severe pain in veterans: the effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. J Pain. 2017;18(3):247-254.

17. Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432-442.

18. Nazario M. Opioid therapy risk management: the VA opioid safety and naloxone distribution initiatives. http://jfpsmeeting.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/slides/Opioid%20Therapy%20Risk%20Management.pdf. Published October 15, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2017.

19. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. MMWR Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49.

20. Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, et al. Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. J Behav Med. 2015;38:535.

21. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157.

22. NIDA/SAMHSA Blending Initiative. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidasamhsa-blending-initiative. Updated November 2015. Accessed November 1, 2017.

23. Alford DP, German JS, Samet JH, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini CA, Saitz R. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):486-491.

1. D’Arcy Y. Treating acute pain in the hospitalized patient. Nurse Pract. 2012;37(8):22-30.

2. Marks AD, Rodgers PE. Diagnosis and management of acute pain in the hospitalized patient. Am J Med. 2014;3(3):e396-e408.

3. Paice JA, Von Roenn JH. Under- or overtreatment of pain in the patient with cancer: how to achieve proper balance. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1721-1726.

4. Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573-1581.

5. Palomano RC, Rathmell JP, Krenzischek DA, Dunwoody CJ. Emerging trends and new approaches to acute pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(suppl 1):S43-S53.

6. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Facing addiction in America: the surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health, executive summary. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/executive-summary.pdf. Published November 2016. Accessed November 1, 2017.

7. Bagian JP, Cohen M, Barnsteiner JH, et al. Safe use of opioids in hospitals. Sentinel Event Alert. 2012;49:1-5.

8. Atkinson TJ, Gulum AH, Forkum WG. The future of pain pharmacy: directed by need. Integrated Pharm Res Pract. 2016;2016(5):33-42.

9. Lothian ST, Fotis MA, Von Gutten CF, et al. Cancer pain management through a pharmacist-based analgesic dosing service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1119-1125.

10. Lynn MA. Pharmacist interventions in pain management. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(14):1487-1489.

11. Strickland JM, Huskey A, Brushwood DB. Pharmacist-physician collaboration in pain management practice. J Opioid Manag. 2007;3(6):295-301.

12. Fan T and Elgourt T. Pain management pharmacy service in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(16):1560-1565.

13. Andrews LB, Bridgeman MB, Dalal KS, et al. Implementation of a pharmacist-directed pain management consultation service for hospitalised adults with a history of substance abuse. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(12):1342-1349.

14. Poirier RH, Brown CS, Garcia YT, Gann NY, Sandoval RA, McNulty JR. Implementation of a pharmacist directed pain management service in the inpatient setting. http://www.ashpadvantage.com/bestpractices/2014_papers/Kaweah-Delta.htm. Published 2014. Accessed November 1, 2017.

15. Langley GL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nded. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

16. Nahin, RL. Severe pain in veterans: the effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. J Pain. 2017;18(3):247-254.

17. Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432-442.

18. Nazario M. Opioid therapy risk management: the VA opioid safety and naloxone distribution initiatives. http://jfpsmeeting.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/slides/Opioid%20Therapy%20Risk%20Management.pdf. Published October 15, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2017.

19. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. MMWR Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49.

20. Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, et al. Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. J Behav Med. 2015;38:535.

21. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157.

22. NIDA/SAMHSA Blending Initiative. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidasamhsa-blending-initiative. Updated November 2015. Accessed November 1, 2017.

23. Alford DP, German JS, Samet JH, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini CA, Saitz R. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):486-491.