User login

Transplantation palliative care: The time is ripe

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Who Gets to Determine Whether Home Is “Unsafe” at the End of Life?

Sometimes a patient at the end of life (EOL) just wants to go home. We recently treated such a patient, “Joe,” a 66-year-old veteran with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), severe hearing loss, and heavy alcohol use. A neighbor brought Joe to the hospital when he developed a urinary tract infection. Before hospitalization, Joe spent his days in bed. His neighbor was his designated health care agent (HCA) and caregiver, dropping off meals and bringing Joe to medical appointments. Joe had no other social support. In the hospital, Joe could not participate in physical therapy (PT) evaluations due to severe dyspnea on exertion. He was recommended for home PT, a home health aide, and home nursing, but Joe declined these services out of concern for encroachment on his independence. Given his heavy alcohol use, limited support, and functional limitations, the hospitalist team felt that Joe would be best served in a skilled nursing facility. As the palliative care team, we were consulted and felt that he was eligible for hospice. Joe simply wanted to go home.

Many patients like Joe experience functional decline at EOL, leading to increased care needs and transitions between sites of care.1 Some hospitalized patients at EOL want to transition directly to home, but due to their limited functioning and social support, discharge home may be deemed unsafe by health care professionals (HCPs). Clinicians then face the difficult balancing act of honoring patient wishes and avoiding a bad outcome. For patients at EOL, issues of capacity and risk become particularly salient. Furthermore, the unique structure of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system and the psychosocial needs of some veterans add additional considerations for complex EOL discharges.2

End-of-life Decision Making

While patients may express strong preferences regarding their health care, their decision-making ability may worsen as they approach EOL. Contributing factors include older age, effects of hospitalization, treatment adverse effects, and comorbidities, including cognitive impairment. Studies of terminally ill patients show high rates of impaired decisional capacity.3,4 It is critical to assess capacity as part of discharge planning. Even when patients have the capacity, families and caregivers have an important voice, since they are often instrumental in maintaining patients at home.

Defining Risk

Determining whether a discharge is risky or unsafe is highly subjective, with differing opinions among clinicians and between patients and clinicians.5-7 In a qualitative study by Coombs and colleagues, HCPs tended toward a risk-averse approach to discharge decisions, sometimes favoring discharge to care facilities despite patient preferences.6 This approach also reflects pressures from the health care system to decrease the length of stay and reduce readmissions, important metrics for patient care and cost containment. However, keeping patients hospitalized or in nursing facilities does not completely mitigate risks (eg, falls) and carries other hazards (eg, nosocomial infections), as highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic.7,8 The prospect of malpractice lawsuits and HCP moral distress about perceived risky home situations can also understandably affect decision making.

At the same time, risk calculation changes depending on the patient’s clinical status and priorities. Coombs and colleagues found that in contrast to clinicians, patients nearing EOL are willing to accept increasing risks and suboptimal living conditions to remain at home.6 What may be intolerable for a younger, healthier patient with a long life expectancy may be acceptable for someone who is approaching EOL. In our framework, a risky home discharge at EOL is considered one in which other adverse events, such as falls or inadequate symptom management, are likely.

Ethical Considerations

Unsafe discharges are challenging in part because some of the pillars of medical ethics can conflict. Prior articles have analyzed the ethical concerns of unsafe discharges in detail.9-11 Briefly, when patients wish to return home against initial medical recommendations, treatment teams may focus on the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, as exemplified by the desire to minimize harm, and justice, in which clinicians consider resource allocation and risks that a home discharge poses to family members, caregivers, and home health professionals. However, autonomy is important to consider as well. The concept of dignity of risk highlights the imperative to respect others’ decisions even when they increase the chance of harm, particularly given the overall shift in medicine from paternalism to shared decision making.12 Accommodating patient choice in how and where health care is received allows patients to regain some control over their lives, thereby enhancing their quality of life and promoting patient dignity, especially in their remaining days.13

Discharge Risk Framework

Our risk assessment framework helps clinicians more objectively identify factors that increase or decrease risk, inform discharge planning, partner with patients and families, give patients a prominent role in EOL decisions, and mitigate the risk of a bad outcome. This concept has been used in psychiatry, in which formal suicide assessment includes identifying risk factors and protective factors to estimate suicide risk and determine interventions.14 Similar to suicide risk estimation, this framework is based on clinical judgment rather than a specific calculation.

While this framework serves as a guide for determining and mitigating risk, we encourage teams to consider legal or ethical consultations in challenging cases, such as those in which patients lack both capacity and an involved HCA.

Step 1: Determine the patient’s capacity regarding disposition planning. Patients at EOL are at a higher risk of impaired decision-making capabilities; therefore, capacity evaluation is a critical step.

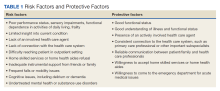

Step 2: Identify risk factors and protective factors for discharge home. Risk factors are intrinsic and extrinsic factors that increase risk such as functional or sensory impairments. Protective factors are intrinsic and extrinsic factors that decrease risk, including a good understanding of illness and consistent connection with the health care system (Table 1).

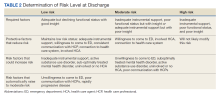

Step 3: Determine discharge to home risk level based on identified risk factors and protective factors. Patients may be at low, moderate, or high risk of having an adverse event, such as a fall or inadequate symptom control (Table 2).

Step 4: Identify risk mitigation strategies. These should be tailored to the patient based on the factors identified in Step 2. Examples include home nursing and therapy, mental health treatment, a medical alert system, and frequent contact between the patient and health care team.

Step 5: Meet with inpatient and outpatient HCP teams. Meetings should include the primary care professional (PCP) or relevant subspecialist, such as an oncologist for patients with cancer. For veterans receiving care solely at a local VA medical center, this can be easier to facilitate, but for veterans who receive care through both VA and non-VA systems, this step may require additional coordination. We also recommend including interdisciplinary team members, such as social workers, case managers, and the relevant home care or hospice agency. Certain agencies may decline admission if they perceive increased risk, such as no 24-hour care, perceived self-neglect, and limited instrumental support. During this meeting, HCPs discuss risk mitigation strategies identified in Step 4 and create a plan to propose to patients and families.

Step 6: Meet with patient, HCA, and family members. In addition to sharing information about prognosis, assessing caregiver capabilities and burden can guide conversations about discharge. The discharge plan should be determined through shared decision making.11 If the patient lacks capacity regarding disposition planning, this should be shared with the HCA. However, even when patients lack capacity, it is important to continue to engage them to understand their goals and preferences.

Step 7: Maximize risk mitigation strategies. If a moderate- or high-risk discharge is requested, the health care team should maximize risk mitigation strategies. For low-risk discharges, risk mitigation strategies can still promote safety, especially since risk increases as patients progress toward EOL. In some instances, patients, their HCAs, or caregivers may decline all risk mitigation strategies despite best efforts to communicate and negotiate options. In such circumstances, we recommend discussing the case with the outpatient team for a warm handoff. HCPs should also document all efforts (helpful from a legal standpoint as well as for the patient’s future treatment teams) and respect the decision to discharge home.

Applying the Framework

Our patient Joe provides a good illustration of how to implement this EOL framework. He was deemed to have the capacity to make decisions regarding discharge (Step 1). We determined his risk factors and protective factors for discharge (Step 2). His poor functional status, limited instrumental support, heavy alcohol use, rejection of home services, and communication barriers due to severe hearing impairment all increased his risk. Protective factors included an appreciation of functional limitations, intact cognition, and an involved HCA. Based on his limited instrumental support and poor function but good insight into limitations, discharge home was deemed to be of moderate risk (Step 3). Although risk factors such as alcohol use and severe hearing impairment could have raised his level to high risk, we felt that his involved HCA maintained him in the moderate-risk category.

We worked with the hospitalist team, PT, and audiology to identify multiple risk mitigation strategies: frequent phone calls between the HCA and outpatient palliative care team, home PT to improve transfers from bed to bedside commode, home nursing services either through a routine agency or hospice, and hearing aids for better communication (Steps 4 and 5). We then proposed these strategies to Joe and his HCA (Step 6). Due to concerns about infringement on his independence, Joe declined all home services but agreed to twice-daily check-ins by his HCA, frequent communication between his HCA and our team, and new hearing aids.

Joe returned home with the agreed-upon risk mitigation strategies in place (Step 7). Despite clinicians’ original reservations about sending Joe home without formal services, his HCA maintained close contact with our team, noting that Joe remained stable and happy to be at home in the months following discharge.

Conclusions

Fortunately, VA HCPs operate in an integrated health care system with access to psychological, social, and at-home medical support that can help mitigate risks. Still, we have benefitted from having a tool to help us evaluate risk systematically. Even if patients, families, and HCPs disagree on ideal discharge plans, this tool helps clinicians approach discharges methodically while maintaining open communication and partnership with patients. In doing so, our framework reflects the shift in medical culture from a patriarchal approach to shared decision-making practices regarding all aspects of medical care. Furthermore, we hope that this can help reduce clinician moral distress stemming from these challenging cases.

Future research on best practices for discharge risk assessment and optimizing home safety are needed. We also hope to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of our framework through interviews with key stakeholders. For Joe and other veterans like him, where to spend their final days may be the last important decision they make in life, and our framework allows for their voices to be better heard throughout the decision-making process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brooke Lifland, MD, for her theoretical contributions to the concept behind this paper.

1. Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); March 19, 2015.

2. Casarett D, Pickard A, Amos Bailey F, et al. Important aspects of end-of-life care among veterans: implications for measurement and quality improvement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(2):115-125. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.03.008

3. Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Brescia R, Comfort C. Assessing decision-making capacity at end of life. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(4):392-397. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.02.013

4. Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Saracino R. Assessing the decision-making capacity of terminally ill patients with cancer. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(5):523-531. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.012

5. Macmillan MS. Hospital staff’s perceptions of risk associated with the discharge of elderly people from acute hospital care. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(2):249-256. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01078.x

6. Coombs MA, Parker R, de Vries K. Managing risk during care transitions when approaching end of life: A qualitative study of patients’ and health care professionals’ decision making. Palliat Med. 2017;31(7):617-624. doi:10.1177/0269216316673476

7. Hyslop B. ‘Not safe for discharge’? Words, values, and person-centred care. Age Ageing. 2020;49(3):334-336. doi:10.1093/ageing/afz170

8. Goodacre S. Safe discharge: an irrational, unhelpful and unachievable concept. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):753-755. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.037903

9. Swidler RN, Seastrum T, Shelton W. Difficult hospital inpatient discharge decisions: ethical, legal and clinical practice issues. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(3):23-28. doi:10.1080/15265160601171739

10. Hill J, Filer W. Safety and ethical considerations in discharging patients to suboptimal living situations. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(6):506-510. Published 2015 Jun 1. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.6.ecas2-1506

11. West JC. What is an ethically informed approach to managing patient safety risk during discharge planning?. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(11):E919-E923. Published 2020 Nov 1. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2020.919

12. Mukherjee D. Discharge decisions and the dignity of risk. Hastings Cent Rep. 2015;45(3):7-8. doi:10.1002/hast.441

13. Wheatley VJ, Baker JI. “Please, I want to go home”: ethical issues raised when considering choice of place of care in palliative care. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(984):643-648. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2007.058487

14. Work Group on Suicidal Behaviors. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(suppl 11):1-60.

Sometimes a patient at the end of life (EOL) just wants to go home. We recently treated such a patient, “Joe,” a 66-year-old veteran with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), severe hearing loss, and heavy alcohol use. A neighbor brought Joe to the hospital when he developed a urinary tract infection. Before hospitalization, Joe spent his days in bed. His neighbor was his designated health care agent (HCA) and caregiver, dropping off meals and bringing Joe to medical appointments. Joe had no other social support. In the hospital, Joe could not participate in physical therapy (PT) evaluations due to severe dyspnea on exertion. He was recommended for home PT, a home health aide, and home nursing, but Joe declined these services out of concern for encroachment on his independence. Given his heavy alcohol use, limited support, and functional limitations, the hospitalist team felt that Joe would be best served in a skilled nursing facility. As the palliative care team, we were consulted and felt that he was eligible for hospice. Joe simply wanted to go home.

Many patients like Joe experience functional decline at EOL, leading to increased care needs and transitions between sites of care.1 Some hospitalized patients at EOL want to transition directly to home, but due to their limited functioning and social support, discharge home may be deemed unsafe by health care professionals (HCPs). Clinicians then face the difficult balancing act of honoring patient wishes and avoiding a bad outcome. For patients at EOL, issues of capacity and risk become particularly salient. Furthermore, the unique structure of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system and the psychosocial needs of some veterans add additional considerations for complex EOL discharges.2

End-of-life Decision Making

While patients may express strong preferences regarding their health care, their decision-making ability may worsen as they approach EOL. Contributing factors include older age, effects of hospitalization, treatment adverse effects, and comorbidities, including cognitive impairment. Studies of terminally ill patients show high rates of impaired decisional capacity.3,4 It is critical to assess capacity as part of discharge planning. Even when patients have the capacity, families and caregivers have an important voice, since they are often instrumental in maintaining patients at home.

Defining Risk

Determining whether a discharge is risky or unsafe is highly subjective, with differing opinions among clinicians and between patients and clinicians.5-7 In a qualitative study by Coombs and colleagues, HCPs tended toward a risk-averse approach to discharge decisions, sometimes favoring discharge to care facilities despite patient preferences.6 This approach also reflects pressures from the health care system to decrease the length of stay and reduce readmissions, important metrics for patient care and cost containment. However, keeping patients hospitalized or in nursing facilities does not completely mitigate risks (eg, falls) and carries other hazards (eg, nosocomial infections), as highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic.7,8 The prospect of malpractice lawsuits and HCP moral distress about perceived risky home situations can also understandably affect decision making.

At the same time, risk calculation changes depending on the patient’s clinical status and priorities. Coombs and colleagues found that in contrast to clinicians, patients nearing EOL are willing to accept increasing risks and suboptimal living conditions to remain at home.6 What may be intolerable for a younger, healthier patient with a long life expectancy may be acceptable for someone who is approaching EOL. In our framework, a risky home discharge at EOL is considered one in which other adverse events, such as falls or inadequate symptom management, are likely.

Ethical Considerations

Unsafe discharges are challenging in part because some of the pillars of medical ethics can conflict. Prior articles have analyzed the ethical concerns of unsafe discharges in detail.9-11 Briefly, when patients wish to return home against initial medical recommendations, treatment teams may focus on the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, as exemplified by the desire to minimize harm, and justice, in which clinicians consider resource allocation and risks that a home discharge poses to family members, caregivers, and home health professionals. However, autonomy is important to consider as well. The concept of dignity of risk highlights the imperative to respect others’ decisions even when they increase the chance of harm, particularly given the overall shift in medicine from paternalism to shared decision making.12 Accommodating patient choice in how and where health care is received allows patients to regain some control over their lives, thereby enhancing their quality of life and promoting patient dignity, especially in their remaining days.13

Discharge Risk Framework

Our risk assessment framework helps clinicians more objectively identify factors that increase or decrease risk, inform discharge planning, partner with patients and families, give patients a prominent role in EOL decisions, and mitigate the risk of a bad outcome. This concept has been used in psychiatry, in which formal suicide assessment includes identifying risk factors and protective factors to estimate suicide risk and determine interventions.14 Similar to suicide risk estimation, this framework is based on clinical judgment rather than a specific calculation.

While this framework serves as a guide for determining and mitigating risk, we encourage teams to consider legal or ethical consultations in challenging cases, such as those in which patients lack both capacity and an involved HCA.

Step 1: Determine the patient’s capacity regarding disposition planning. Patients at EOL are at a higher risk of impaired decision-making capabilities; therefore, capacity evaluation is a critical step.

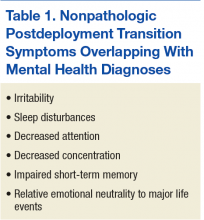

Step 2: Identify risk factors and protective factors for discharge home. Risk factors are intrinsic and extrinsic factors that increase risk such as functional or sensory impairments. Protective factors are intrinsic and extrinsic factors that decrease risk, including a good understanding of illness and consistent connection with the health care system (Table 1).

Step 3: Determine discharge to home risk level based on identified risk factors and protective factors. Patients may be at low, moderate, or high risk of having an adverse event, such as a fall or inadequate symptom control (Table 2).

Step 4: Identify risk mitigation strategies. These should be tailored to the patient based on the factors identified in Step 2. Examples include home nursing and therapy, mental health treatment, a medical alert system, and frequent contact between the patient and health care team.

Step 5: Meet with inpatient and outpatient HCP teams. Meetings should include the primary care professional (PCP) or relevant subspecialist, such as an oncologist for patients with cancer. For veterans receiving care solely at a local VA medical center, this can be easier to facilitate, but for veterans who receive care through both VA and non-VA systems, this step may require additional coordination. We also recommend including interdisciplinary team members, such as social workers, case managers, and the relevant home care or hospice agency. Certain agencies may decline admission if they perceive increased risk, such as no 24-hour care, perceived self-neglect, and limited instrumental support. During this meeting, HCPs discuss risk mitigation strategies identified in Step 4 and create a plan to propose to patients and families.

Step 6: Meet with patient, HCA, and family members. In addition to sharing information about prognosis, assessing caregiver capabilities and burden can guide conversations about discharge. The discharge plan should be determined through shared decision making.11 If the patient lacks capacity regarding disposition planning, this should be shared with the HCA. However, even when patients lack capacity, it is important to continue to engage them to understand their goals and preferences.

Step 7: Maximize risk mitigation strategies. If a moderate- or high-risk discharge is requested, the health care team should maximize risk mitigation strategies. For low-risk discharges, risk mitigation strategies can still promote safety, especially since risk increases as patients progress toward EOL. In some instances, patients, their HCAs, or caregivers may decline all risk mitigation strategies despite best efforts to communicate and negotiate options. In such circumstances, we recommend discussing the case with the outpatient team for a warm handoff. HCPs should also document all efforts (helpful from a legal standpoint as well as for the patient’s future treatment teams) and respect the decision to discharge home.

Applying the Framework

Our patient Joe provides a good illustration of how to implement this EOL framework. He was deemed to have the capacity to make decisions regarding discharge (Step 1). We determined his risk factors and protective factors for discharge (Step 2). His poor functional status, limited instrumental support, heavy alcohol use, rejection of home services, and communication barriers due to severe hearing impairment all increased his risk. Protective factors included an appreciation of functional limitations, intact cognition, and an involved HCA. Based on his limited instrumental support and poor function but good insight into limitations, discharge home was deemed to be of moderate risk (Step 3). Although risk factors such as alcohol use and severe hearing impairment could have raised his level to high risk, we felt that his involved HCA maintained him in the moderate-risk category.

We worked with the hospitalist team, PT, and audiology to identify multiple risk mitigation strategies: frequent phone calls between the HCA and outpatient palliative care team, home PT to improve transfers from bed to bedside commode, home nursing services either through a routine agency or hospice, and hearing aids for better communication (Steps 4 and 5). We then proposed these strategies to Joe and his HCA (Step 6). Due to concerns about infringement on his independence, Joe declined all home services but agreed to twice-daily check-ins by his HCA, frequent communication between his HCA and our team, and new hearing aids.

Joe returned home with the agreed-upon risk mitigation strategies in place (Step 7). Despite clinicians’ original reservations about sending Joe home without formal services, his HCA maintained close contact with our team, noting that Joe remained stable and happy to be at home in the months following discharge.

Conclusions

Fortunately, VA HCPs operate in an integrated health care system with access to psychological, social, and at-home medical support that can help mitigate risks. Still, we have benefitted from having a tool to help us evaluate risk systematically. Even if patients, families, and HCPs disagree on ideal discharge plans, this tool helps clinicians approach discharges methodically while maintaining open communication and partnership with patients. In doing so, our framework reflects the shift in medical culture from a patriarchal approach to shared decision-making practices regarding all aspects of medical care. Furthermore, we hope that this can help reduce clinician moral distress stemming from these challenging cases.

Future research on best practices for discharge risk assessment and optimizing home safety are needed. We also hope to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of our framework through interviews with key stakeholders. For Joe and other veterans like him, where to spend their final days may be the last important decision they make in life, and our framework allows for their voices to be better heard throughout the decision-making process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brooke Lifland, MD, for her theoretical contributions to the concept behind this paper.

Sometimes a patient at the end of life (EOL) just wants to go home. We recently treated such a patient, “Joe,” a 66-year-old veteran with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), severe hearing loss, and heavy alcohol use. A neighbor brought Joe to the hospital when he developed a urinary tract infection. Before hospitalization, Joe spent his days in bed. His neighbor was his designated health care agent (HCA) and caregiver, dropping off meals and bringing Joe to medical appointments. Joe had no other social support. In the hospital, Joe could not participate in physical therapy (PT) evaluations due to severe dyspnea on exertion. He was recommended for home PT, a home health aide, and home nursing, but Joe declined these services out of concern for encroachment on his independence. Given his heavy alcohol use, limited support, and functional limitations, the hospitalist team felt that Joe would be best served in a skilled nursing facility. As the palliative care team, we were consulted and felt that he was eligible for hospice. Joe simply wanted to go home.

Many patients like Joe experience functional decline at EOL, leading to increased care needs and transitions between sites of care.1 Some hospitalized patients at EOL want to transition directly to home, but due to their limited functioning and social support, discharge home may be deemed unsafe by health care professionals (HCPs). Clinicians then face the difficult balancing act of honoring patient wishes and avoiding a bad outcome. For patients at EOL, issues of capacity and risk become particularly salient. Furthermore, the unique structure of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system and the psychosocial needs of some veterans add additional considerations for complex EOL discharges.2

End-of-life Decision Making

While patients may express strong preferences regarding their health care, their decision-making ability may worsen as they approach EOL. Contributing factors include older age, effects of hospitalization, treatment adverse effects, and comorbidities, including cognitive impairment. Studies of terminally ill patients show high rates of impaired decisional capacity.3,4 It is critical to assess capacity as part of discharge planning. Even when patients have the capacity, families and caregivers have an important voice, since they are often instrumental in maintaining patients at home.

Defining Risk

Determining whether a discharge is risky or unsafe is highly subjective, with differing opinions among clinicians and between patients and clinicians.5-7 In a qualitative study by Coombs and colleagues, HCPs tended toward a risk-averse approach to discharge decisions, sometimes favoring discharge to care facilities despite patient preferences.6 This approach also reflects pressures from the health care system to decrease the length of stay and reduce readmissions, important metrics for patient care and cost containment. However, keeping patients hospitalized or in nursing facilities does not completely mitigate risks (eg, falls) and carries other hazards (eg, nosocomial infections), as highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic.7,8 The prospect of malpractice lawsuits and HCP moral distress about perceived risky home situations can also understandably affect decision making.

At the same time, risk calculation changes depending on the patient’s clinical status and priorities. Coombs and colleagues found that in contrast to clinicians, patients nearing EOL are willing to accept increasing risks and suboptimal living conditions to remain at home.6 What may be intolerable for a younger, healthier patient with a long life expectancy may be acceptable for someone who is approaching EOL. In our framework, a risky home discharge at EOL is considered one in which other adverse events, such as falls or inadequate symptom management, are likely.

Ethical Considerations

Unsafe discharges are challenging in part because some of the pillars of medical ethics can conflict. Prior articles have analyzed the ethical concerns of unsafe discharges in detail.9-11 Briefly, when patients wish to return home against initial medical recommendations, treatment teams may focus on the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, as exemplified by the desire to minimize harm, and justice, in which clinicians consider resource allocation and risks that a home discharge poses to family members, caregivers, and home health professionals. However, autonomy is important to consider as well. The concept of dignity of risk highlights the imperative to respect others’ decisions even when they increase the chance of harm, particularly given the overall shift in medicine from paternalism to shared decision making.12 Accommodating patient choice in how and where health care is received allows patients to regain some control over their lives, thereby enhancing their quality of life and promoting patient dignity, especially in their remaining days.13

Discharge Risk Framework

Our risk assessment framework helps clinicians more objectively identify factors that increase or decrease risk, inform discharge planning, partner with patients and families, give patients a prominent role in EOL decisions, and mitigate the risk of a bad outcome. This concept has been used in psychiatry, in which formal suicide assessment includes identifying risk factors and protective factors to estimate suicide risk and determine interventions.14 Similar to suicide risk estimation, this framework is based on clinical judgment rather than a specific calculation.

While this framework serves as a guide for determining and mitigating risk, we encourage teams to consider legal or ethical consultations in challenging cases, such as those in which patients lack both capacity and an involved HCA.

Step 1: Determine the patient’s capacity regarding disposition planning. Patients at EOL are at a higher risk of impaired decision-making capabilities; therefore, capacity evaluation is a critical step.

Step 2: Identify risk factors and protective factors for discharge home. Risk factors are intrinsic and extrinsic factors that increase risk such as functional or sensory impairments. Protective factors are intrinsic and extrinsic factors that decrease risk, including a good understanding of illness and consistent connection with the health care system (Table 1).

Step 3: Determine discharge to home risk level based on identified risk factors and protective factors. Patients may be at low, moderate, or high risk of having an adverse event, such as a fall or inadequate symptom control (Table 2).

Step 4: Identify risk mitigation strategies. These should be tailored to the patient based on the factors identified in Step 2. Examples include home nursing and therapy, mental health treatment, a medical alert system, and frequent contact between the patient and health care team.

Step 5: Meet with inpatient and outpatient HCP teams. Meetings should include the primary care professional (PCP) or relevant subspecialist, such as an oncologist for patients with cancer. For veterans receiving care solely at a local VA medical center, this can be easier to facilitate, but for veterans who receive care through both VA and non-VA systems, this step may require additional coordination. We also recommend including interdisciplinary team members, such as social workers, case managers, and the relevant home care or hospice agency. Certain agencies may decline admission if they perceive increased risk, such as no 24-hour care, perceived self-neglect, and limited instrumental support. During this meeting, HCPs discuss risk mitigation strategies identified in Step 4 and create a plan to propose to patients and families.

Step 6: Meet with patient, HCA, and family members. In addition to sharing information about prognosis, assessing caregiver capabilities and burden can guide conversations about discharge. The discharge plan should be determined through shared decision making.11 If the patient lacks capacity regarding disposition planning, this should be shared with the HCA. However, even when patients lack capacity, it is important to continue to engage them to understand their goals and preferences.

Step 7: Maximize risk mitigation strategies. If a moderate- or high-risk discharge is requested, the health care team should maximize risk mitigation strategies. For low-risk discharges, risk mitigation strategies can still promote safety, especially since risk increases as patients progress toward EOL. In some instances, patients, their HCAs, or caregivers may decline all risk mitigation strategies despite best efforts to communicate and negotiate options. In such circumstances, we recommend discussing the case with the outpatient team for a warm handoff. HCPs should also document all efforts (helpful from a legal standpoint as well as for the patient’s future treatment teams) and respect the decision to discharge home.

Applying the Framework

Our patient Joe provides a good illustration of how to implement this EOL framework. He was deemed to have the capacity to make decisions regarding discharge (Step 1). We determined his risk factors and protective factors for discharge (Step 2). His poor functional status, limited instrumental support, heavy alcohol use, rejection of home services, and communication barriers due to severe hearing impairment all increased his risk. Protective factors included an appreciation of functional limitations, intact cognition, and an involved HCA. Based on his limited instrumental support and poor function but good insight into limitations, discharge home was deemed to be of moderate risk (Step 3). Although risk factors such as alcohol use and severe hearing impairment could have raised his level to high risk, we felt that his involved HCA maintained him in the moderate-risk category.

We worked with the hospitalist team, PT, and audiology to identify multiple risk mitigation strategies: frequent phone calls between the HCA and outpatient palliative care team, home PT to improve transfers from bed to bedside commode, home nursing services either through a routine agency or hospice, and hearing aids for better communication (Steps 4 and 5). We then proposed these strategies to Joe and his HCA (Step 6). Due to concerns about infringement on his independence, Joe declined all home services but agreed to twice-daily check-ins by his HCA, frequent communication between his HCA and our team, and new hearing aids.

Joe returned home with the agreed-upon risk mitigation strategies in place (Step 7). Despite clinicians’ original reservations about sending Joe home without formal services, his HCA maintained close contact with our team, noting that Joe remained stable and happy to be at home in the months following discharge.

Conclusions

Fortunately, VA HCPs operate in an integrated health care system with access to psychological, social, and at-home medical support that can help mitigate risks. Still, we have benefitted from having a tool to help us evaluate risk systematically. Even if patients, families, and HCPs disagree on ideal discharge plans, this tool helps clinicians approach discharges methodically while maintaining open communication and partnership with patients. In doing so, our framework reflects the shift in medical culture from a patriarchal approach to shared decision-making practices regarding all aspects of medical care. Furthermore, we hope that this can help reduce clinician moral distress stemming from these challenging cases.

Future research on best practices for discharge risk assessment and optimizing home safety are needed. We also hope to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of our framework through interviews with key stakeholders. For Joe and other veterans like him, where to spend their final days may be the last important decision they make in life, and our framework allows for their voices to be better heard throughout the decision-making process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brooke Lifland, MD, for her theoretical contributions to the concept behind this paper.

1. Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); March 19, 2015.

2. Casarett D, Pickard A, Amos Bailey F, et al. Important aspects of end-of-life care among veterans: implications for measurement and quality improvement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(2):115-125. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.03.008

3. Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Brescia R, Comfort C. Assessing decision-making capacity at end of life. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(4):392-397. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.02.013

4. Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Saracino R. Assessing the decision-making capacity of terminally ill patients with cancer. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(5):523-531. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.012

5. Macmillan MS. Hospital staff’s perceptions of risk associated with the discharge of elderly people from acute hospital care. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(2):249-256. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01078.x

6. Coombs MA, Parker R, de Vries K. Managing risk during care transitions when approaching end of life: A qualitative study of patients’ and health care professionals’ decision making. Palliat Med. 2017;31(7):617-624. doi:10.1177/0269216316673476

7. Hyslop B. ‘Not safe for discharge’? Words, values, and person-centred care. Age Ageing. 2020;49(3):334-336. doi:10.1093/ageing/afz170

8. Goodacre S. Safe discharge: an irrational, unhelpful and unachievable concept. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):753-755. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.037903

9. Swidler RN, Seastrum T, Shelton W. Difficult hospital inpatient discharge decisions: ethical, legal and clinical practice issues. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(3):23-28. doi:10.1080/15265160601171739

10. Hill J, Filer W. Safety and ethical considerations in discharging patients to suboptimal living situations. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(6):506-510. Published 2015 Jun 1. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.6.ecas2-1506

11. West JC. What is an ethically informed approach to managing patient safety risk during discharge planning?. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(11):E919-E923. Published 2020 Nov 1. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2020.919

12. Mukherjee D. Discharge decisions and the dignity of risk. Hastings Cent Rep. 2015;45(3):7-8. doi:10.1002/hast.441

13. Wheatley VJ, Baker JI. “Please, I want to go home”: ethical issues raised when considering choice of place of care in palliative care. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(984):643-648. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2007.058487

14. Work Group on Suicidal Behaviors. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(suppl 11):1-60.

1. Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); March 19, 2015.

2. Casarett D, Pickard A, Amos Bailey F, et al. Important aspects of end-of-life care among veterans: implications for measurement and quality improvement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(2):115-125. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.03.008

3. Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Brescia R, Comfort C. Assessing decision-making capacity at end of life. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(4):392-397. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.02.013

4. Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Saracino R. Assessing the decision-making capacity of terminally ill patients with cancer. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(5):523-531. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.012

5. Macmillan MS. Hospital staff’s perceptions of risk associated with the discharge of elderly people from acute hospital care. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(2):249-256. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01078.x

6. Coombs MA, Parker R, de Vries K. Managing risk during care transitions when approaching end of life: A qualitative study of patients’ and health care professionals’ decision making. Palliat Med. 2017;31(7):617-624. doi:10.1177/0269216316673476

7. Hyslop B. ‘Not safe for discharge’? Words, values, and person-centred care. Age Ageing. 2020;49(3):334-336. doi:10.1093/ageing/afz170

8. Goodacre S. Safe discharge: an irrational, unhelpful and unachievable concept. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):753-755. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.037903

9. Swidler RN, Seastrum T, Shelton W. Difficult hospital inpatient discharge decisions: ethical, legal and clinical practice issues. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(3):23-28. doi:10.1080/15265160601171739

10. Hill J, Filer W. Safety and ethical considerations in discharging patients to suboptimal living situations. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(6):506-510. Published 2015 Jun 1. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.6.ecas2-1506

11. West JC. What is an ethically informed approach to managing patient safety risk during discharge planning?. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(11):E919-E923. Published 2020 Nov 1. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2020.919

12. Mukherjee D. Discharge decisions and the dignity of risk. Hastings Cent Rep. 2015;45(3):7-8. doi:10.1002/hast.441

13. Wheatley VJ, Baker JI. “Please, I want to go home”: ethical issues raised when considering choice of place of care in palliative care. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(984):643-648. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2007.058487

14. Work Group on Suicidal Behaviors. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(suppl 11):1-60.

Comprehensive and Equitable Care for Vulnerable Veterans With Integrated Palliative, Psychology, and Oncology Care

Veterans living with cancer need comprehensive assessment that includes supportive psychosocial care. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer require accredited cancer centers to evaluate psychosocial distress and provide appropriate triage and treatment for all patients.1-3 Implementing psychosocial distress screening can be difficult because of procedural barriers and time constraints, clinic and supportive care resources, and lack of knowledge about how to access supportive services.

Distress screening protocols must be designed to address the specific needs of each population. To improve screening for cancer-related distress, deliver effective supportive services, and gain agreement on distress screening standards of care, the Coleman Foundation supported development of the Coleman Supportive Oncology Collaborative (CSOC), a project of 135 interdisciplinary health care professionals from 25 Chicago-area cancer care institutions.4

The Jesse Brown US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center (JBVAMC) was chosen to assess cancer-related concerns among veterans using the CSOC screening tool and to improve access to supportive oncology. JBVAMC provides care to approximately 49,000 veterans in Chicago, Illinois, and northwestern Indiana. The JBVAMC patient population includes a large number of veterans with dual diagnoses (co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders) and veterans experiencing homelessness.

Delivering integrated screening and oncologic care that is culture and age appropriate is particularly important for veterans given their unique risk factors. The veteran population is considered vulnerable in terms of health status, psychological functioning, and social context. Veterans who use the VA health system as a principal source of care have poorer health, greater comorbid medical conditions, and an increased risk of mortality and suicide compared with the general population.5,6 Poorer health status in veterans also may relate to old age, low income, poor education, psychological health, and minority race.7-9

Past studies point to unique risk factors for cancer and poor cancer adjustment among veterans, which may complicate cancer treatment and end-of-life/survivorship care. Veteran-specific risk factors include military-related exposures, particularly Agent Orange and morbidity/mortality secondary to comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]).10-12 Moreover, the geriatric veteran population continues to grow,with increasing rates of cancer that require unique considerations for effective cancer care.13,14 Despite this, there are minimal data to inform best practices and supportive care approaches for veterans with cancer. Lack of guidelines specific to veterans and other populations with increased psychosocial challenges may impede successful cancer care, making distress screening procedures particularly important. This is especially the case for the JBVAMC, which serves primarily African American urban-dwelling veterans who experience high rates of cancer disparities, including increased rates of mortality and increased levels of psychosocial distress.15,16

The goals of this program were to (1) examine levels of psychological, physical, financial, and treatment-related distress in a large sample of urban-dwelling veterans; (2) create a streamlined, sustainable process to screen a large number of veterans receiving cancer care in the outpatient setting and connect them with available supportive services; and (3) educate oncology physicians, nurses, and other staff about cancer-related distress and concerns using in-service trainings and interpersonal interactions to improve patient care. Our program was based on a Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PCMHI) model that embeds health psychologists in general medical clinics to better reach veterans dealing with mental health issues. We tailored for palliative care involvement.

Studies of this model have shown that mental health integration improves access to mental health services and mental health treatment outcomes and has higher patient and provider satisfaction.17 We were also influenced by the construct of the patient aligned care team (PACT) social worker who, in this veteran-centered approach, often functions as a care coordinator. Social work responsibilities include assessment of patients’ stressors including adjusting to the medical conditions, identifying untreated or undertreated mental health or substance abuse issues, economic instability, legal problems, and inadequate housing and transportation, which can often be exacerbated during cancer treatment.18

We screened for distress-related needs that included mental health concerns, physical needs including uncontrolled symptoms or adverse effects of cancer treatment, physical function complaints (eg, pain and fatigue), nutrition concerns, treatment or care related concerns, family and caregiver needs, along with financial challenges (housing and food) and insurance-related support. The goal of this article is to describe the development and implementation of this VA-specific distress screening program and reflect on the lessons learned for the application of streamlined distress screening and triage in similar settings throughout the VA health system and other similar settings.

Methods

This institutional review board at JBVAMC reviewed and exempted this quality improvement program using the SQUIRE framework.19 It was led by a group of palliative care clinicians, psychologists, and administrators who have worked with the oncology service for many years, primarily in the care of hospitalized patients. Common palliative care services include providing care for patients with serious illness diagnosis through the illness trajectory.

Setting

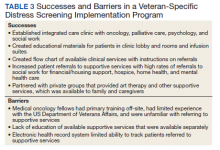

At the start of this program, we assessed the current clinic workflow to determine how to best screen and assist veterans experiencing distress. We met with team members individually to identify the best method of clinic integration, including attending medical oncologists, medical oncology fellows, psychology interns, oncology nursing staff, the oncology nurse coordinator, and clinic clerks.

The JBVAMC provides cancer care through 4 half-day medical hematology-oncology clinics that serve about 50 patients per half-day clinic. The clinics are staffed by hematology-oncology fellows supervised by hematology-oncology attending physicians, who are affiliated with 2 academic medical centers. These clinics are staffed by 3 registered nurses (RNs) and a licensed practical nurse (LPN) and are adjacent to a chemotherapy infusion clinic with unique nursing staff. The JBVAMC also provides a variety of supportive care services, including extensive mental health and substance use treatment, physical and occupational therapy, acupuncture, nutrition, social work, and housing services. Following our assessment, it was evident that there were a low number of referrals from oncology clinics to supportive care services, mostly due to lack of knowledge of resources and unclear referral procedures.

Based on clinical volume, we determined that our screening program could best be implemented through a stepped approach beginning in one clinic and expanding thereafter. We began by having a palliative care physician and health psychology intern embedded in 1 weekly half-day clinic and a health psychology intern embedded in a second weekly half-day clinic. Our program included 2 health psychology interns (for each academic year of the program) who were supervised by a JBVA health psychologist.

About 15 months after successful integration within the first 2 half-day clinics, we expanded the screening program to staff an additional half-day medical oncology clinic with a palliative care APRN. This allowed us to expand the screening tool distribution and collection to 3 of 4 of the weekly half-day oncology clinics as well as to meet individually with veterans experiencing high levels of distress. Veterans were flagged as having high distress levels by either the results of their completed screening tool or by referral from a medical oncology physician. We initially established screening in clinics that were sufficiently staffed to ensure that screens were appropriately distributed and reviewed. Patients seen in nonparticipating clinics were referred to outpatient social work, mental health and/or outpatient palliative care according to oncology fellows’ clinical assessments of the patient. All oncology fellows received education about distress screening and methods for referring to supportive care. Our clinic screening program extended from February 2017 through January 2020.

Screening

Program staff screened patients with new cancer diagnoses, then identified patients for follow-up screens. This tracking allowed staff to identify patients with oncology appointments that day and cross-reference patients needing a follow-up screen.

Following feedback from the clinic nurses, we determined that nurses would provide the distress tool to patients in paper form after they completed their assessment of vitals and waited to be seen by their medical oncologist. The patient would then deliver their completed form to the nurse who would combine it with the patient’s clinic notes for the oncologist to review.

Veterans referred for supportive care services were contacted by the relevant clinical administrator by phone to schedule an intake; for social work referrals, patients were either seen in a walk-in office located in a colocated building or contacted by a social worker by phone.

Our screening tool was the Coleman Foundation Supportive Oncology Collaborative Screening Tool, compiled from validated instruments. Patients completed this screening tool, which includes the PHQ-4, NCCN problem list concerns, adapted Mini Nutrition Assessment and PROMIS Pain and Fatigue measure (eAppendix B available at doi:10.12788/fp.0158).20-22

We also worked with the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) to create an electronic template for the screening tool. Completed screening tools were manually entered by the physician, psychologists, or APRN into the CPRS chart.

We analyzed the different supportive care services available at the JBVAMC and noticed that many supportive services were available, yet these services were often separated. Therefore, we created a consult flowsheet to assist oncologists in placing referrals. These supportive care services include mental health services, a cancer support group, home health care, social services, nutrition, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and other specialty services.

Patient Education

The psychology and nursing staff created a patient information bulletin board where patients could access information about supportive services available at JBVAMC. This board required frequent replenishment of handouts because patients consulted the board regularly. Handouts and folders about common clinical issues also were placed in the clinic treatment rooms. We partnered with 2 local cancer support centers, Gilda’s Club and the Cancer Support Center, to make referrals for family members and/or caregivers who would benefit from additional support.

We provided in-service trainings for oncology fellows, including trainings on PTSD and substance abuse and their relationship to cancer care at the VA. These topics were chosen based on the feedback program staff received about perceived knowledge gaps from the oncology fellows. This program allowed for multiple informal conversations between that program staff and oncology fellows about overall patient care. We held trainings with the cancer coordinator and clinical nursing staff on strategies to identify and follow-up on cancer-related distress, and with oncology fellows to review the importance of distress screening and to instruct fellows on instructions for the consult flowsheet.

Funding

This program was funded by the Chicago-based Coleman Foundation as part of the CSOC. Funding was used to support a portion of time for administrative and clinical work of program staff, as well as data collection and analysis.

Results

We established 3 half-day integrated clinics where patients were screened and referred for services based on supportive oncology needs. In addition to our primary activities to screen and refer veterans, we held multiple educational sessions for colleagues, developed a workflow template, and integrated patient education materials into the clinics.

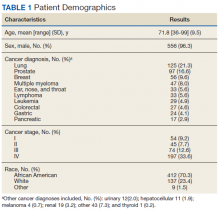

Screening