User login

Ready for post-acute care?

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

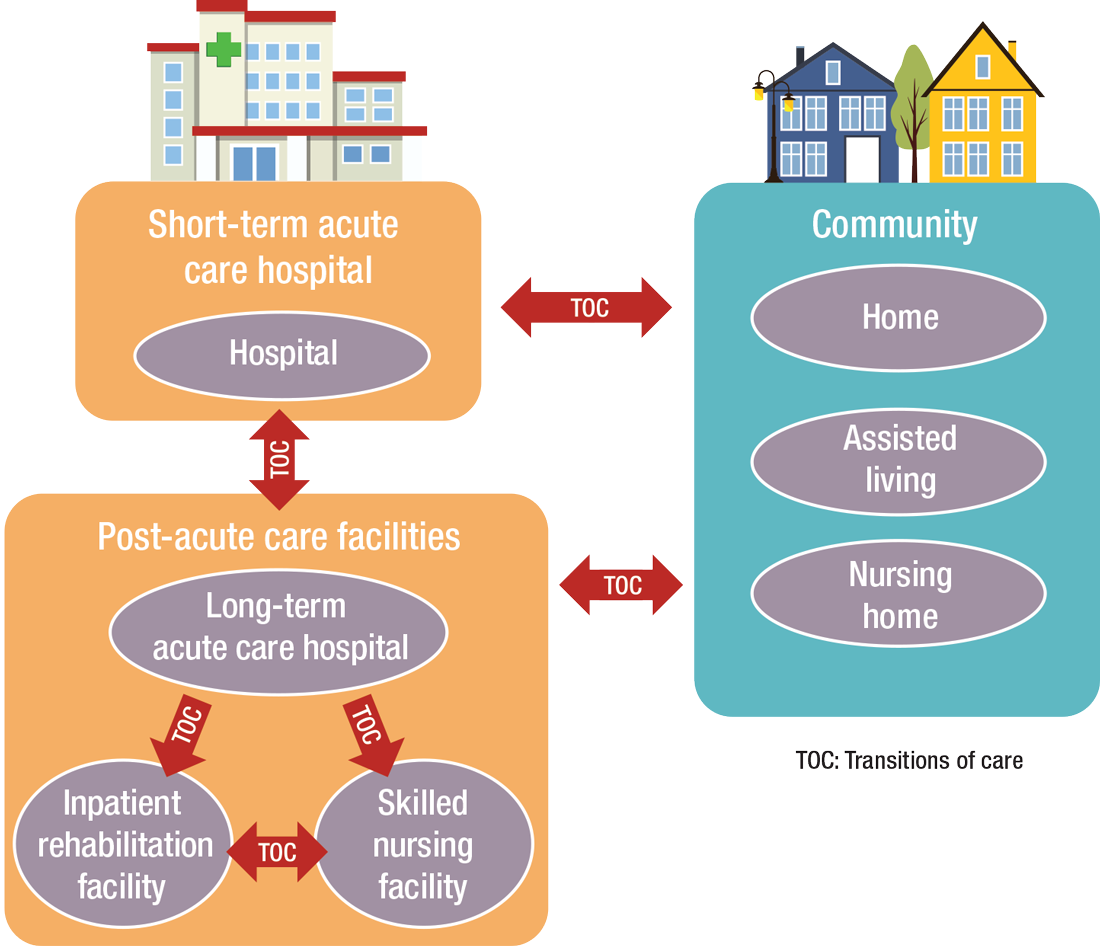

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

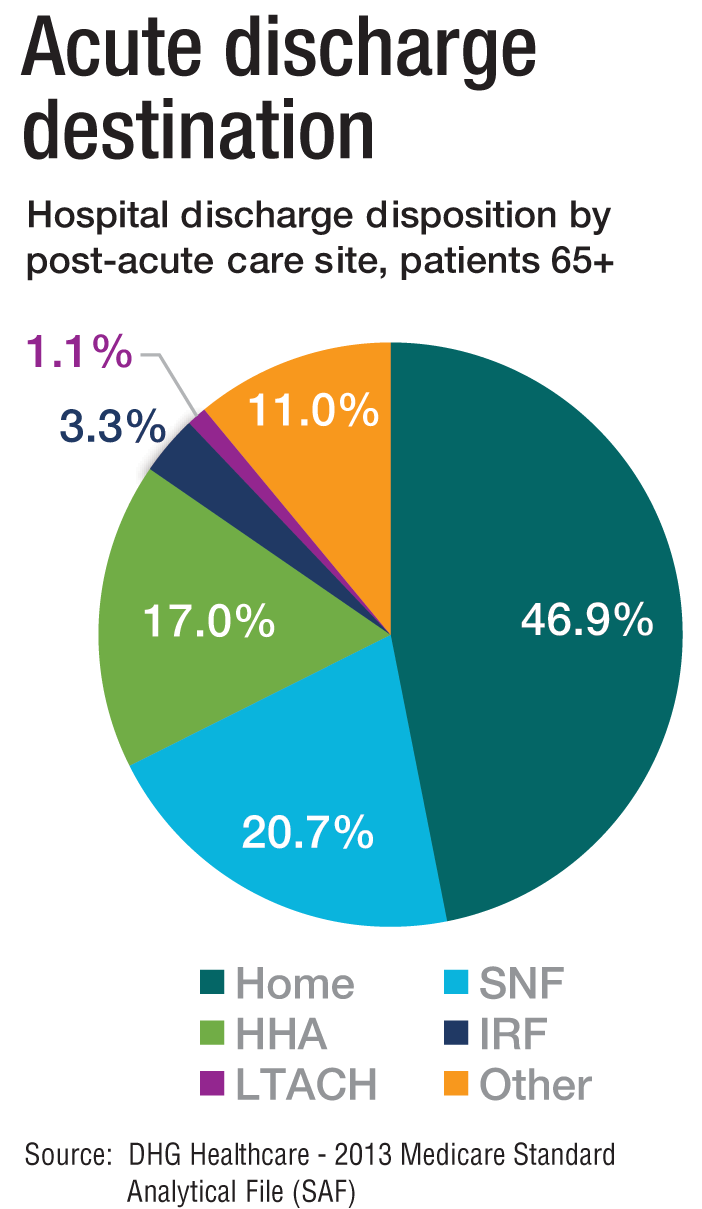

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

Registered Dieticians Sparse in VA Cancer Care

Veterans Health Administration cancer centers are lacking registered dieticians (RDs), and patients are more likely to be diagnosed with malnutrition when they are on staff, according to a new study.

The average number of full-time RDs across 13 cancer centers was just 1 per 1,065 patients, advanced practice oncology dietitian Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO, of the Phoenix VA Health Care System, reported at the AVAHO annual meeting.

However, patients treated by RDs were more likely to be diagnosed with malnutrition (odds ratio [OR], 2.9, 95% CI, 1.6-5.1). And patients were more likely to maintain weight if their clinic had a higher ratio of RDs to oncologists (OR, 1.6 for each 10% increase in ratio, 95% CI, 2.0-127.5).

Petersen told Federal Practitioner that dieticians came up with the idea for the study after attending AVAHO meetings. “A lot of the questions we were getting from physicians and other providers were: How do we get dietitians in our clinic?”

There is currently no standard staffing model for dieticians in oncology centers, Petersen said, and they are not reimbursed through Medicare or Medicaid. “We thought, ‘What do we add to the cancer center by having adequate staffing levels and seeing cancer patients?’ We designed a study to try and get to the heart of that.”

Petersen and her team focused on malnutrition. Nutrition impairment impacts an estimated 40% to 80% of patients with gastrointestinal, head and neck, pancreas, and colorectal cancer at diagnosis, she said.

Petersen discussed the published evidence that outlines how physicians recognize malnutrition at a lower rate than RDs. Dietary counseling from an RD is linked to better nutritional outcomes, physical function, and quality of life.

The study authors examined 2016 and 2017 VA registry data and reviewed charts of 681 veterans treated by 207 oncologists. Oncology clinics had a mean of 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE) RD. The mean ratio of full-time RDs to oncologists was 1 per 48.5 and ranged from 1 per 4 to 1 per 850.

“It's almost like somebody randomly assigned [RDs] to cancer centers, and it has nothing to do with how many patients are seen in that particular center,” Petersen said. “Some clinics only have .1 or .2 FTEs assigned, and that may be a larger cancer center where they have maybe 85 cancer oncology providers, which includes surgical, medical, and radiation oncology and trainees.”

Why would a clinic have a .1 FTE RD, which suggests someone may be working 4 hours a week? In this kind of situation, an RD may cover a variety of areas and only work in cancer care when they receive a referral, Petersen said.

“That is just vastly underserving veterans,” she said. “You're missing so many veterans whom you could help with preventative care if you're only getting patients referred based on consults.”

As for the findings regarding higher RD staffing and higher detection of malnutrition, the study text notes “there was not a ‘high enough’ level of RD staffing at which we stopped seeing this trend. This is probably because – at least at the time of this study – no VA cancer center was adequately staffed for nutrition.”

Petersen hopes the findings will convince VA cancer center leadership to boost better patient outcomes by prioritizing the hiring of RDs.

Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO has no disclosures.

Veterans Health Administration cancer centers are lacking registered dieticians (RDs), and patients are more likely to be diagnosed with malnutrition when they are on staff, according to a new study.

The average number of full-time RDs across 13 cancer centers was just 1 per 1,065 patients, advanced practice oncology dietitian Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO, of the Phoenix VA Health Care System, reported at the AVAHO annual meeting.

However, patients treated by RDs were more likely to be diagnosed with malnutrition (odds ratio [OR], 2.9, 95% CI, 1.6-5.1). And patients were more likely to maintain weight if their clinic had a higher ratio of RDs to oncologists (OR, 1.6 for each 10% increase in ratio, 95% CI, 2.0-127.5).

Petersen told Federal Practitioner that dieticians came up with the idea for the study after attending AVAHO meetings. “A lot of the questions we were getting from physicians and other providers were: How do we get dietitians in our clinic?”

There is currently no standard staffing model for dieticians in oncology centers, Petersen said, and they are not reimbursed through Medicare or Medicaid. “We thought, ‘What do we add to the cancer center by having adequate staffing levels and seeing cancer patients?’ We designed a study to try and get to the heart of that.”

Petersen and her team focused on malnutrition. Nutrition impairment impacts an estimated 40% to 80% of patients with gastrointestinal, head and neck, pancreas, and colorectal cancer at diagnosis, she said.

Petersen discussed the published evidence that outlines how physicians recognize malnutrition at a lower rate than RDs. Dietary counseling from an RD is linked to better nutritional outcomes, physical function, and quality of life.

The study authors examined 2016 and 2017 VA registry data and reviewed charts of 681 veterans treated by 207 oncologists. Oncology clinics had a mean of 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE) RD. The mean ratio of full-time RDs to oncologists was 1 per 48.5 and ranged from 1 per 4 to 1 per 850.

“It's almost like somebody randomly assigned [RDs] to cancer centers, and it has nothing to do with how many patients are seen in that particular center,” Petersen said. “Some clinics only have .1 or .2 FTEs assigned, and that may be a larger cancer center where they have maybe 85 cancer oncology providers, which includes surgical, medical, and radiation oncology and trainees.”

Why would a clinic have a .1 FTE RD, which suggests someone may be working 4 hours a week? In this kind of situation, an RD may cover a variety of areas and only work in cancer care when they receive a referral, Petersen said.

“That is just vastly underserving veterans,” she said. “You're missing so many veterans whom you could help with preventative care if you're only getting patients referred based on consults.”

As for the findings regarding higher RD staffing and higher detection of malnutrition, the study text notes “there was not a ‘high enough’ level of RD staffing at which we stopped seeing this trend. This is probably because – at least at the time of this study – no VA cancer center was adequately staffed for nutrition.”

Petersen hopes the findings will convince VA cancer center leadership to boost better patient outcomes by prioritizing the hiring of RDs.

Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO has no disclosures.

Veterans Health Administration cancer centers are lacking registered dieticians (RDs), and patients are more likely to be diagnosed with malnutrition when they are on staff, according to a new study.

The average number of full-time RDs across 13 cancer centers was just 1 per 1,065 patients, advanced practice oncology dietitian Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO, of the Phoenix VA Health Care System, reported at the AVAHO annual meeting.

However, patients treated by RDs were more likely to be diagnosed with malnutrition (odds ratio [OR], 2.9, 95% CI, 1.6-5.1). And patients were more likely to maintain weight if their clinic had a higher ratio of RDs to oncologists (OR, 1.6 for each 10% increase in ratio, 95% CI, 2.0-127.5).

Petersen told Federal Practitioner that dieticians came up with the idea for the study after attending AVAHO meetings. “A lot of the questions we were getting from physicians and other providers were: How do we get dietitians in our clinic?”

There is currently no standard staffing model for dieticians in oncology centers, Petersen said, and they are not reimbursed through Medicare or Medicaid. “We thought, ‘What do we add to the cancer center by having adequate staffing levels and seeing cancer patients?’ We designed a study to try and get to the heart of that.”

Petersen and her team focused on malnutrition. Nutrition impairment impacts an estimated 40% to 80% of patients with gastrointestinal, head and neck, pancreas, and colorectal cancer at diagnosis, she said.

Petersen discussed the published evidence that outlines how physicians recognize malnutrition at a lower rate than RDs. Dietary counseling from an RD is linked to better nutritional outcomes, physical function, and quality of life.

The study authors examined 2016 and 2017 VA registry data and reviewed charts of 681 veterans treated by 207 oncologists. Oncology clinics had a mean of 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE) RD. The mean ratio of full-time RDs to oncologists was 1 per 48.5 and ranged from 1 per 4 to 1 per 850.

“It's almost like somebody randomly assigned [RDs] to cancer centers, and it has nothing to do with how many patients are seen in that particular center,” Petersen said. “Some clinics only have .1 or .2 FTEs assigned, and that may be a larger cancer center where they have maybe 85 cancer oncology providers, which includes surgical, medical, and radiation oncology and trainees.”

Why would a clinic have a .1 FTE RD, which suggests someone may be working 4 hours a week? In this kind of situation, an RD may cover a variety of areas and only work in cancer care when they receive a referral, Petersen said.

“That is just vastly underserving veterans,” she said. “You're missing so many veterans whom you could help with preventative care if you're only getting patients referred based on consults.”

As for the findings regarding higher RD staffing and higher detection of malnutrition, the study text notes “there was not a ‘high enough’ level of RD staffing at which we stopped seeing this trend. This is probably because – at least at the time of this study – no VA cancer center was adequately staffed for nutrition.”

Petersen hopes the findings will convince VA cancer center leadership to boost better patient outcomes by prioritizing the hiring of RDs.

Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO has no disclosures.

Age-Friendly Health Systems Transformation: A Whole Person Approach to Support the Well-Being of Older AdultsAge-Friendly Health Systems Transformation: A Whole Person Approach to Support the Well-Being of Older Adults

The COVID-19 pandemic established a new normal for health care delivery, with leaders rethinking core practices to survive and thrive in a changing environment and improve the health and well-being of patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is embracing a shift in focus from “what is the matter” to “what really matters” to address pre- and postpandemic challenges through a whole health approach.1 Initially conceptualized by the VHA in 2011, whole health “is an approach to health care that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being so that they can live their life to the fullest.”1 Whole health integrates evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage pain; this includes acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, yoga, massage therapy, guided imagery, biofeedback, and clinical hypnosis.1 The VHA now recognizes well-being as a core value, helping clinicians respond to emerging challenges related to the social determinants of health (eg, access to health care, physical activity, and healthy foods) and guiding health care decision making.1,2

Well-being through empowerment—elements of whole health and Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS)—encourages health care institutions to work with employees, patients, and other stakeholders to address global challenges, clinician burnout, and social issues faced by their communities. This approach focuses on life’s purpose and meaning for individuals and inspires leaders to engage with patients, staff, and communities in new, impactful ways by focusing on wellbeing and wholeness rather than illness and disease. Having a higher sense of purpose is associated with lower all-cause mortality, reduced risk of specific diseases, better health behaviors, greater use of preventive services, and fewer hospital days of care.3

This article describes how AFHS supports the well-being of older adults and aligns with the whole health model of care. It also outlines the VHA investment to transform health care to be more person-centered by documenting what matters in the electronic health record (EHR).

AGE-FRIENDLY CARE

Given that nearly half of veterans enrolled in the VHA are aged ≥ 65 years, there is an increased need to identify models of care to support this aging population.4 This is especially critical because older veterans often have multiple chronic conditions and complex care needs that benefit from a whole person approach. The AFHS movement aims to provide evidence-based care aligned with what matters to older adults and provides a mechanism for transforming care to meet the needs of older veterans. This includes addressing age-related health concerns while promoting optimal health outcomes and quality of life. AFHS follows the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.5 The 4Ms serve as a guide for the health care of older adults in any setting, where each “M” is assessed and acted on to support what matters.5 Since 2020, > 390 teams have developed a plan to implement the 4Ms at 156 VHA facilities, demonstrating the VHA commitment to transforming health care for veterans.6

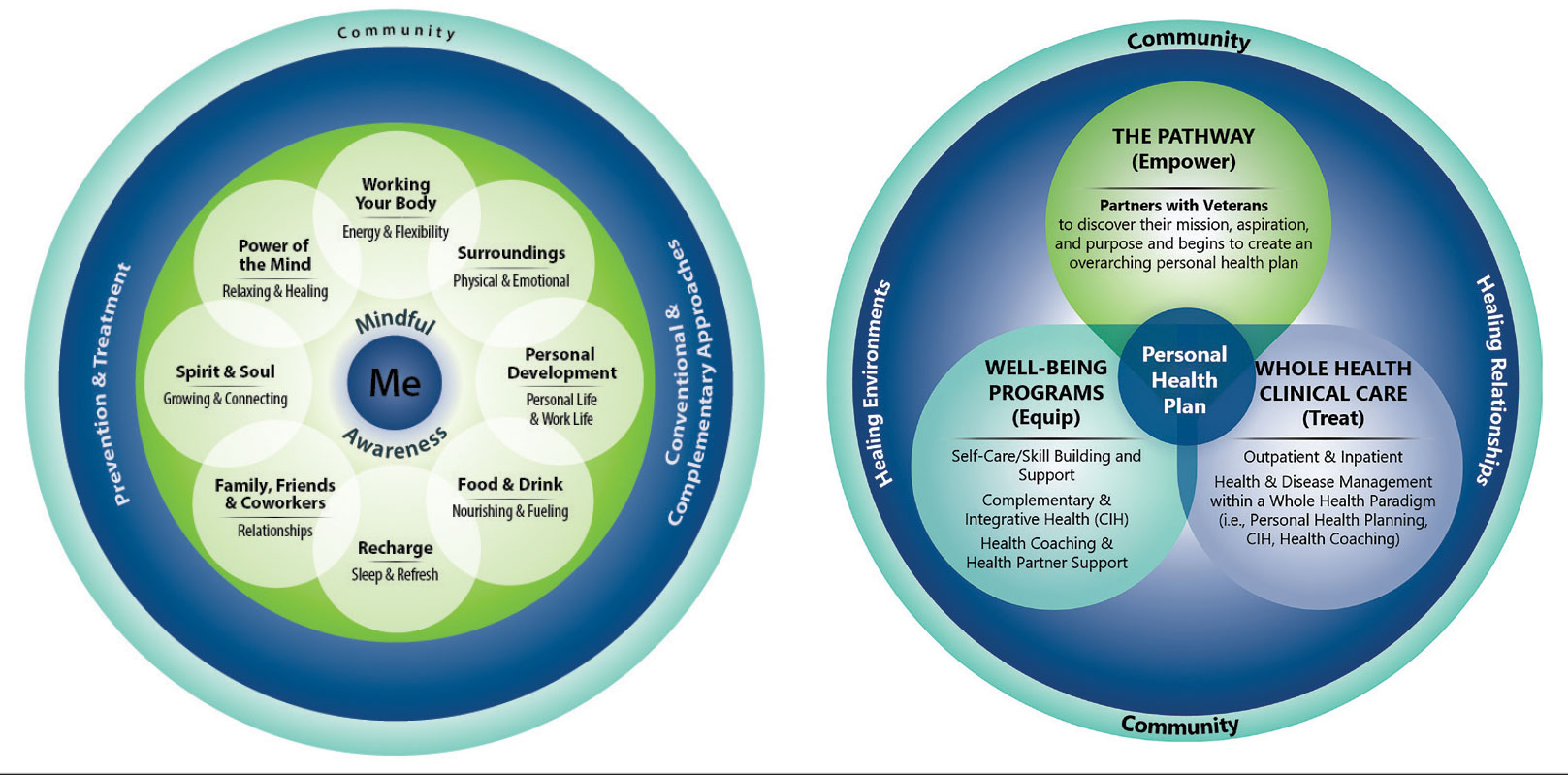

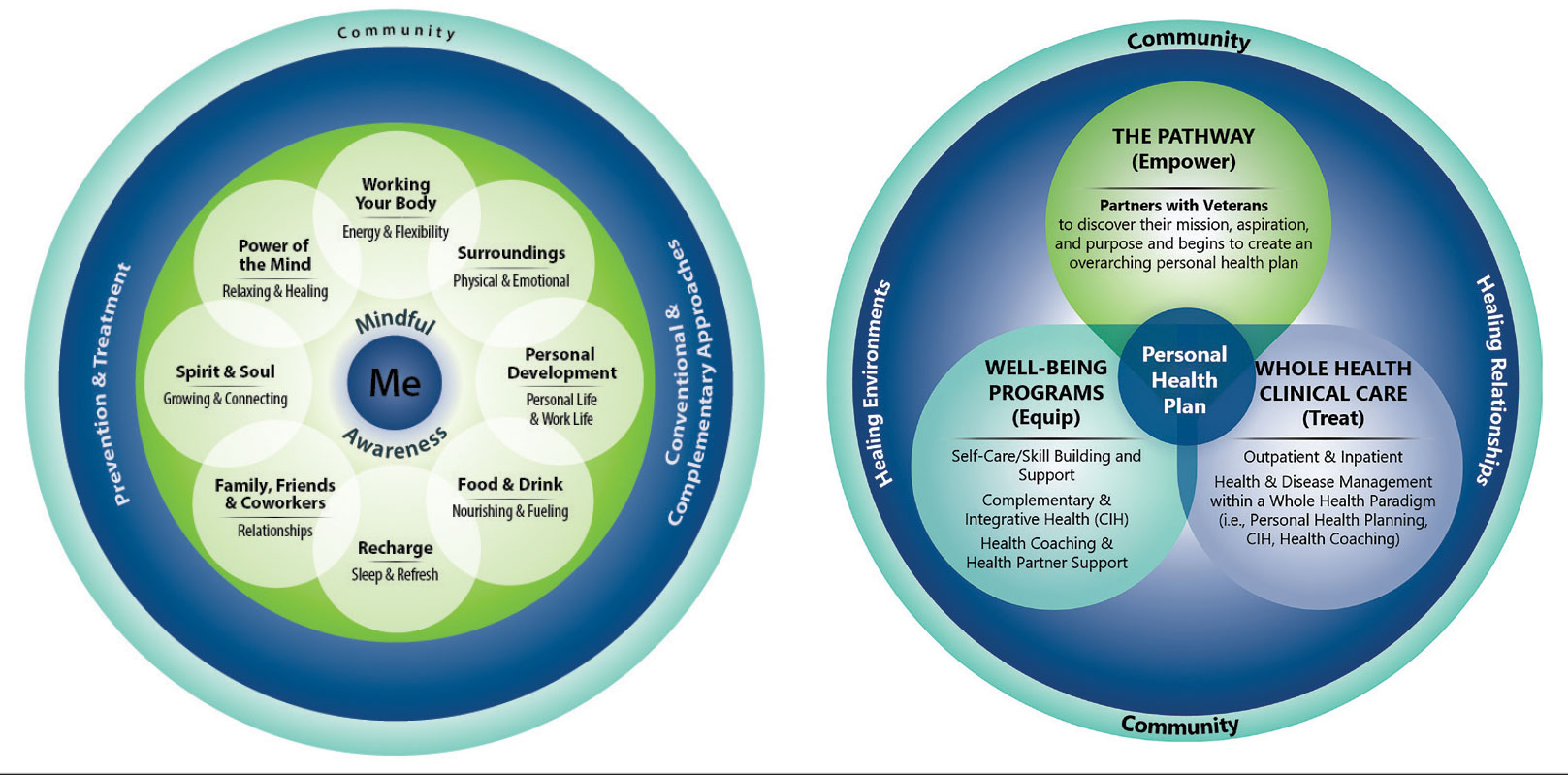

When VHA teams join the AFHS movement, they may also engage older veterans in a whole health system (WHS) (Figure). While AFHS is designed to improve care for patients aged ≥ 65 years, it also complements whole health, a person-centered approach available to all veterans enrolled in the VHA. Through the WHS and AFHS, veterans are empowered and equipped to take charge of their health and well-being through conversations about their unique goals, preferences, and health priorities.4 Clinicians are challenged to assess what matters by asking questions like, “What brings you joy?” and, “How can we help you meet your health goals?”1,5 These questions shift the conversation from disease-based treatment and enable clinicians to better understand the veteran as a person.1,5

For whole health and AFHS, conversations about what matters are anchored in the veteran’s goals and preferences, especially those facing a significant health change (ie, a new diagnosis or treatment decision).5,7 Together, the veteran’s goals and priorities serve as the foundation for developing person-centered care plans that often go beyond conventional medical treatments to address the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of health.

SYSTEM-WIDE DIRECTIVE

The WHS enhances AFHS discussions about what matters to veterans by adding a system-level lens for conceptualizing health care delivery by leveraging the 3 components of WHS: the “pathway,” well-being programs, and whole health clinical care.

The Pathway

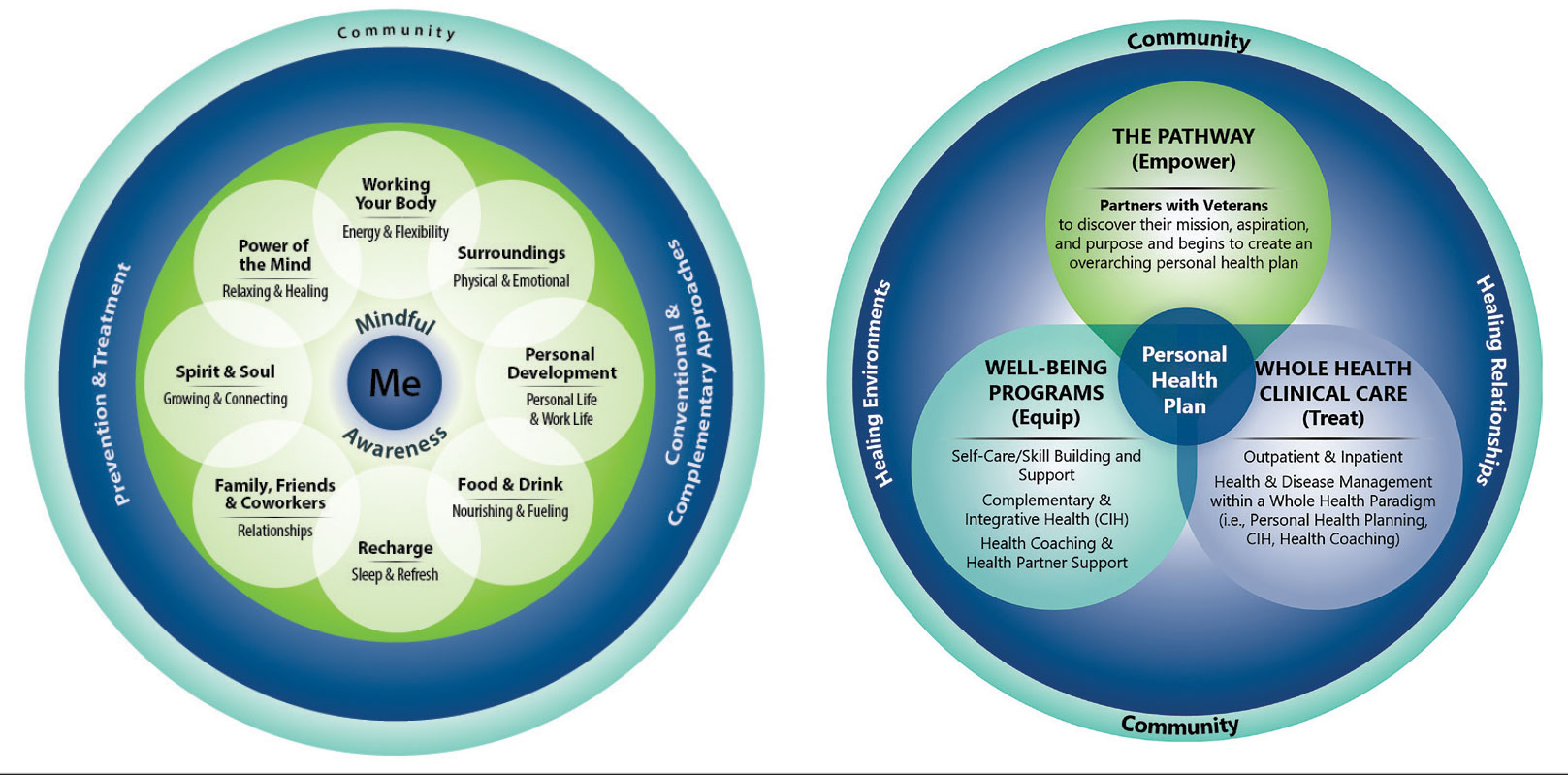

Discovering what matters, or the veteran’s “mission, aspiration, and purpose,” begins with the WHS pathway. When stepping into the pathway, veterans begin completing a personal health inventory, or “walking the circle of health,” which encourages self-reflection that focuses on components of their life that can influence health and well-being.1,8 The circle of health offers a visual representation of the 4 most important aspects of health and well-being: First, “Me” at the center as an individual who is the expert on their life, values, goals, and priorities. Only the individual can know what really matters through mindful awareness and what works for their life. Second, self-care consists of 8 areas that impact health and wellbeing: working your body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind. Third, professional care consists of prevention, conventional care, and complementary care. Finally, the community that supports the individual.

Well-Being Programs

VHA provides WHS programs that support veterans in building self-care skills and improving their quality of life, often through integrative care clinics that offer coaching and CIH therapies. For example, a veteran who prioritizes mobility when seeking care at an integrative care clinic will not only receive conventional medical treatment for their physical symptoms but may also be offered CIH therapies depending on their goals. The veteran may set a daily mobility goal with their care team that supports what matters, incorporating CIH approaches, such as yoga and tai chi into the care plan.5 These holistic approaches for moving the body can help alleviate physical symptoms, reduce stress, improve mindful awareness, and provide opportunities for self-discovery and growth, thus promote overall well-being

Whole Health Clinical Care

AFHS and the 4Ms embody the clinical care component of the WHS. Because what matters is the driver of the 4Ms, every action taken by the care team supports wellbeing and quality of life by promoting independence, connection, and support, and addressing external factors, such as social determinants of health. At a minimum, well-being includes “functioning well: the experience of positive emotions such as happiness and contentment as well as the development of one’s potential, having some control over one’s life, having a sense of purpose, and experiencing positive relationships.”9 From a system perspective, the VHA has begun to normalize focusing on what matters to veterans, using an interprofessional approach, one of the first steps to implementing AFHS.

As the programs expand, AFHS teams can learn from whole health well-being programs and increase the capacity for self-care in older veterans. Learning about the key elements included in the circle of health helps clinicians understand each veteran’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to support their self-care. From there, teams can act on the 4Ms and connect older veterans with the most appropriate programs and services at their facility, ensuring continuum of care.

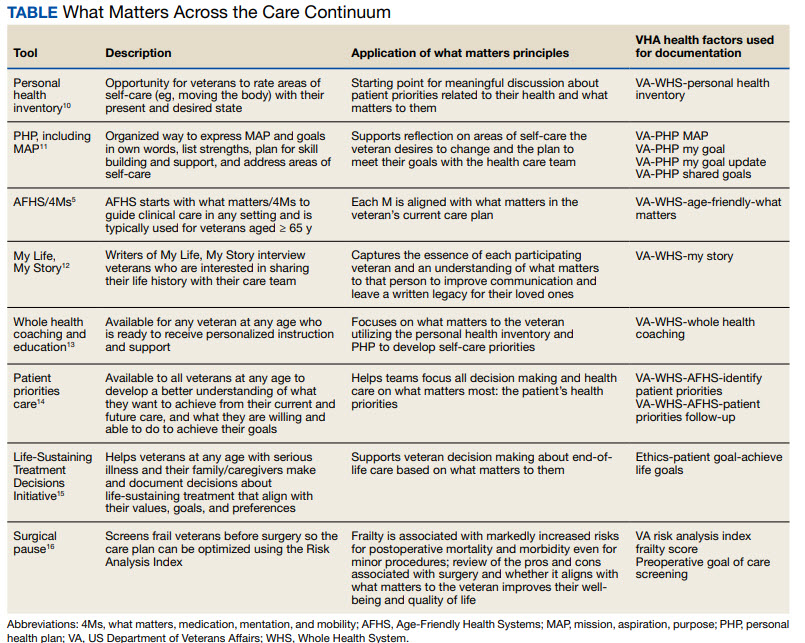

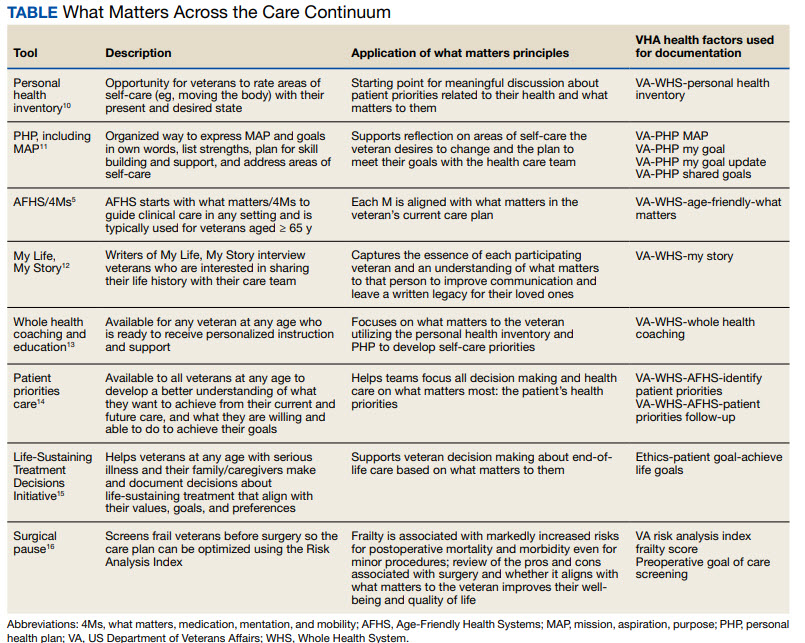

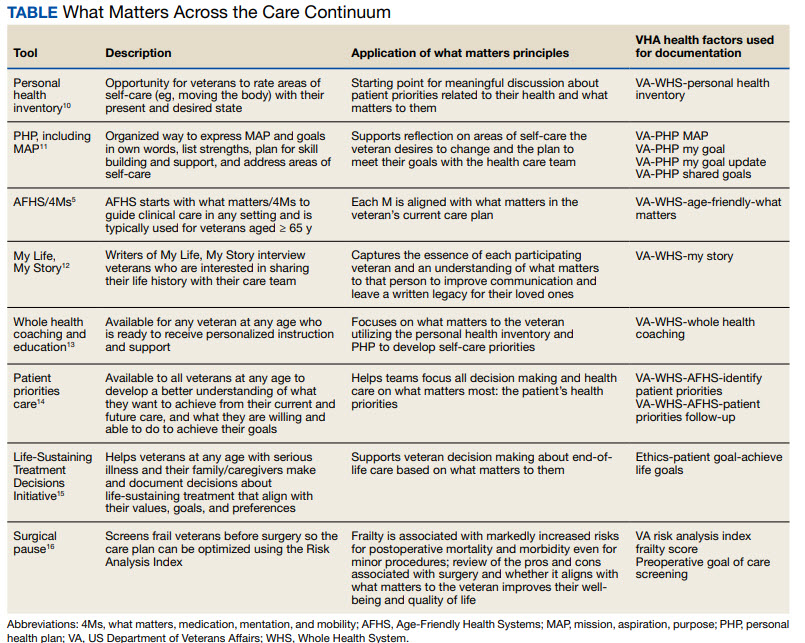

DOCUMENTATION

The VHA leverages several tools and evidence-based practices to assess and act on what matters for veterans of all ages (Table).5,10-16 The VHA EHR and associated dashboards contain a wealth of information about whole health and AFHS implementation, scale up, and spread. A national AFHS 4Ms note template contains standardized data elements called health factors, which provide a mechanism for monitoring 4Ms care via its related dashboard. This template was developed by an interprofessional workgroup of VHA staff and underwent a thorough human factors engineering review and testing process prior to its release. Although teams continue to personalize care based on what matters to the veteran, data from the standardized 4Ms note template and dashboard provide a way to establish consistent, equitable care across multiple care settings.17

Between January 2022 and December 2023, > 612,000 participants aged ≥ 65 years identified what matters to them through 1.35 million assessments. During that period, > 36,000 veterans aged ≥ 65 years participated in AFHS and had what matters conversations documented. A personalized health plan was completed by 585,270 veterans for a total of 1.1 million assessments.11 Whole health coaching has been documented for > 57,000 veterans with > 200,000 assessments completed.13 In fiscal year 2023, a total of 1,802,131 veterans participated in whole health.

When teams share information about what matters to the veteran in a clinicianfacing format in the EHR, this helps ensure that the VHA honors veteran preferences throughout transitions of care and across all phases of health care. Although the EHR captures data on what matters, measurement of the overall impact on veteran and health system outcomes is essential. Further evaluation and ongoing education are needed to ensure clinicians are accurately and efficiently capturing the care provided by completing the appropriate EHR. Additional challenges include identifying ways to balance the documentation burden, while ensuring notes include valuable patient-centered information to guide care. EHR tools and templates have helped to unlock important insights on health care delivery in the VHA; however, health systems must consider how these clinical practices support the overall well-being of patients. How leaders empower frontline clinicians in any care setting to use these data to drive meaningful change is also important.

TRANSFORMING VHA CARE DELIVERY

In Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation, the National Academy of Science proposes a framework for the transformation of health care institutions to provide better whole health to veterans.3 Transformation requires change in entire systems and leaders who mobilize people “for participation in the process of change, encouraging a sense of collective identity and collective efficacy, which in turn brings stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy,” and an enhanced sense of meaningfulness in their work and lives.18

Shifting health care approaches to equipping and empowering veterans and employees with whole health and AFHS resources is transformational and requires radically different assumptions and approaches that cannot be realized through traditional approaches. This change requires robust and multifaceted cultural transformation spanning all levels of the organization. Whole health and AFHS are facilitating this transformation by supporting documentation and data needs, tracking outcomes across settings, and accelerating spread to new facilities and care settings nationwide to support older veterans in improving their health and well-being.

Whole health and AFHS are complementary approaches to care that can work to empower veterans (as well as caregivers and clinicians) to align services with what matters most to veterans. Lessons such as standardizing person-centered assessments of what matters, creating supportive structures to better align care with veterans’ priorities, and identifying meaningful veteran and system-level outcomes to help sustain transformational change can be applied from whole health to AFHS. Together these programs have the potential to enhance overall health outcomes and quality of life for veterans.

- Kligler B, Hyde J, Gantt C, Bokhour B. The Whole Health transformation at the Veterans Health Administration: moving from “what’s the matter with you?” to “what matters to you?” Med Care. 2022;60(5):387-391. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001706

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH) at CDC. January 17, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/social-determinants-of-health.html

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. The National Academies Press; 2023. Accessed September 9, 2024. doi:10.17226/26854

- Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-friendly health systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

- Laderman M, Jackson C, Little K, Duong T, Pelton L. “What Matters” to older adults? A toolkit for health systems to design better care with older adults. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHI_Age_Friendly_What_Matters_to_Older_Adults_Toolkit.pdf

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Age-Friendly Health Systems. Updated September 4, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/age-friendly-health-systems

- Brown TT, Hurley VB, Rodriguez HP, et al. Shared dec i s i o n - m a k i n g l o w e r s m e d i c a l e x p e n d i t u re s a n d the effect is amplified in racially-ethnically concordant relationships. Med Care. 2023;61(8):528-535. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001881

- Kligler B. Whole Health in the Veterans Health Administration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:2164957X221077214.

- Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):192. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal Health Inventory. Updated May 2022. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PHI-long-May22-fillable-508.pdf doi:10.1177/2164957X221077214

- Veterans Health Administration. Personal Health Plan. Updated March 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https:// www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PersonalHealthPlan_508_03-2019.pdf

- Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: My Life, My Story. Updated March 20, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/mylifemystory/index.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole Health Library: Whole Health for Skill Building. Updated April 17, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/courses/whole-health-skill-building.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Making Decisions: Current Care Planning. Updated May 21, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/making_decisions.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI). Updated March 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/life-sustaining-treatment-decisions-initiative

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion: Surgical Pause Saving Veterans Lives. Updated September 22, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.cherp.research.va.gov/features/Surgical_Pause_Saving_Veterans_Lives.asp

- Munro S, Church K, Berner C, et al. Implementation of an agefriendly template in the Veterans Health Administration electronic health record. J Inform Nurs. 2023;8(3):6-11.

- Burns JM. Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. Grove Press; 2003.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: Circle of Health Overview. Updated May 20, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/index.asp

The COVID-19 pandemic established a new normal for health care delivery, with leaders rethinking core practices to survive and thrive in a changing environment and improve the health and well-being of patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is embracing a shift in focus from “what is the matter” to “what really matters” to address pre- and postpandemic challenges through a whole health approach.1 Initially conceptualized by the VHA in 2011, whole health “is an approach to health care that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being so that they can live their life to the fullest.”1 Whole health integrates evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage pain; this includes acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, yoga, massage therapy, guided imagery, biofeedback, and clinical hypnosis.1 The VHA now recognizes well-being as a core value, helping clinicians respond to emerging challenges related to the social determinants of health (eg, access to health care, physical activity, and healthy foods) and guiding health care decision making.1,2

Well-being through empowerment—elements of whole health and Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS)—encourages health care institutions to work with employees, patients, and other stakeholders to address global challenges, clinician burnout, and social issues faced by their communities. This approach focuses on life’s purpose and meaning for individuals and inspires leaders to engage with patients, staff, and communities in new, impactful ways by focusing on wellbeing and wholeness rather than illness and disease. Having a higher sense of purpose is associated with lower all-cause mortality, reduced risk of specific diseases, better health behaviors, greater use of preventive services, and fewer hospital days of care.3

This article describes how AFHS supports the well-being of older adults and aligns with the whole health model of care. It also outlines the VHA investment to transform health care to be more person-centered by documenting what matters in the electronic health record (EHR).

AGE-FRIENDLY CARE

Given that nearly half of veterans enrolled in the VHA are aged ≥ 65 years, there is an increased need to identify models of care to support this aging population.4 This is especially critical because older veterans often have multiple chronic conditions and complex care needs that benefit from a whole person approach. The AFHS movement aims to provide evidence-based care aligned with what matters to older adults and provides a mechanism for transforming care to meet the needs of older veterans. This includes addressing age-related health concerns while promoting optimal health outcomes and quality of life. AFHS follows the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.5 The 4Ms serve as a guide for the health care of older adults in any setting, where each “M” is assessed and acted on to support what matters.5 Since 2020, > 390 teams have developed a plan to implement the 4Ms at 156 VHA facilities, demonstrating the VHA commitment to transforming health care for veterans.6

When VHA teams join the AFHS movement, they may also engage older veterans in a whole health system (WHS) (Figure). While AFHS is designed to improve care for patients aged ≥ 65 years, it also complements whole health, a person-centered approach available to all veterans enrolled in the VHA. Through the WHS and AFHS, veterans are empowered and equipped to take charge of their health and well-being through conversations about their unique goals, preferences, and health priorities.4 Clinicians are challenged to assess what matters by asking questions like, “What brings you joy?” and, “How can we help you meet your health goals?”1,5 These questions shift the conversation from disease-based treatment and enable clinicians to better understand the veteran as a person.1,5

For whole health and AFHS, conversations about what matters are anchored in the veteran’s goals and preferences, especially those facing a significant health change (ie, a new diagnosis or treatment decision).5,7 Together, the veteran’s goals and priorities serve as the foundation for developing person-centered care plans that often go beyond conventional medical treatments to address the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of health.

SYSTEM-WIDE DIRECTIVE

The WHS enhances AFHS discussions about what matters to veterans by adding a system-level lens for conceptualizing health care delivery by leveraging the 3 components of WHS: the “pathway,” well-being programs, and whole health clinical care.

The Pathway

Discovering what matters, or the veteran’s “mission, aspiration, and purpose,” begins with the WHS pathway. When stepping into the pathway, veterans begin completing a personal health inventory, or “walking the circle of health,” which encourages self-reflection that focuses on components of their life that can influence health and well-being.1,8 The circle of health offers a visual representation of the 4 most important aspects of health and well-being: First, “Me” at the center as an individual who is the expert on their life, values, goals, and priorities. Only the individual can know what really matters through mindful awareness and what works for their life. Second, self-care consists of 8 areas that impact health and wellbeing: working your body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind. Third, professional care consists of prevention, conventional care, and complementary care. Finally, the community that supports the individual.

Well-Being Programs

VHA provides WHS programs that support veterans in building self-care skills and improving their quality of life, often through integrative care clinics that offer coaching and CIH therapies. For example, a veteran who prioritizes mobility when seeking care at an integrative care clinic will not only receive conventional medical treatment for their physical symptoms but may also be offered CIH therapies depending on their goals. The veteran may set a daily mobility goal with their care team that supports what matters, incorporating CIH approaches, such as yoga and tai chi into the care plan.5 These holistic approaches for moving the body can help alleviate physical symptoms, reduce stress, improve mindful awareness, and provide opportunities for self-discovery and growth, thus promote overall well-being

Whole Health Clinical Care

AFHS and the 4Ms embody the clinical care component of the WHS. Because what matters is the driver of the 4Ms, every action taken by the care team supports wellbeing and quality of life by promoting independence, connection, and support, and addressing external factors, such as social determinants of health. At a minimum, well-being includes “functioning well: the experience of positive emotions such as happiness and contentment as well as the development of one’s potential, having some control over one’s life, having a sense of purpose, and experiencing positive relationships.”9 From a system perspective, the VHA has begun to normalize focusing on what matters to veterans, using an interprofessional approach, one of the first steps to implementing AFHS.

As the programs expand, AFHS teams can learn from whole health well-being programs and increase the capacity for self-care in older veterans. Learning about the key elements included in the circle of health helps clinicians understand each veteran’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to support their self-care. From there, teams can act on the 4Ms and connect older veterans with the most appropriate programs and services at their facility, ensuring continuum of care.

DOCUMENTATION

The VHA leverages several tools and evidence-based practices to assess and act on what matters for veterans of all ages (Table).5,10-16 The VHA EHR and associated dashboards contain a wealth of information about whole health and AFHS implementation, scale up, and spread. A national AFHS 4Ms note template contains standardized data elements called health factors, which provide a mechanism for monitoring 4Ms care via its related dashboard. This template was developed by an interprofessional workgroup of VHA staff and underwent a thorough human factors engineering review and testing process prior to its release. Although teams continue to personalize care based on what matters to the veteran, data from the standardized 4Ms note template and dashboard provide a way to establish consistent, equitable care across multiple care settings.17

Between January 2022 and December 2023, > 612,000 participants aged ≥ 65 years identified what matters to them through 1.35 million assessments. During that period, > 36,000 veterans aged ≥ 65 years participated in AFHS and had what matters conversations documented. A personalized health plan was completed by 585,270 veterans for a total of 1.1 million assessments.11 Whole health coaching has been documented for > 57,000 veterans with > 200,000 assessments completed.13 In fiscal year 2023, a total of 1,802,131 veterans participated in whole health.

When teams share information about what matters to the veteran in a clinicianfacing format in the EHR, this helps ensure that the VHA honors veteran preferences throughout transitions of care and across all phases of health care. Although the EHR captures data on what matters, measurement of the overall impact on veteran and health system outcomes is essential. Further evaluation and ongoing education are needed to ensure clinicians are accurately and efficiently capturing the care provided by completing the appropriate EHR. Additional challenges include identifying ways to balance the documentation burden, while ensuring notes include valuable patient-centered information to guide care. EHR tools and templates have helped to unlock important insights on health care delivery in the VHA; however, health systems must consider how these clinical practices support the overall well-being of patients. How leaders empower frontline clinicians in any care setting to use these data to drive meaningful change is also important.

TRANSFORMING VHA CARE DELIVERY

In Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation, the National Academy of Science proposes a framework for the transformation of health care institutions to provide better whole health to veterans.3 Transformation requires change in entire systems and leaders who mobilize people “for participation in the process of change, encouraging a sense of collective identity and collective efficacy, which in turn brings stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy,” and an enhanced sense of meaningfulness in their work and lives.18

Shifting health care approaches to equipping and empowering veterans and employees with whole health and AFHS resources is transformational and requires radically different assumptions and approaches that cannot be realized through traditional approaches. This change requires robust and multifaceted cultural transformation spanning all levels of the organization. Whole health and AFHS are facilitating this transformation by supporting documentation and data needs, tracking outcomes across settings, and accelerating spread to new facilities and care settings nationwide to support older veterans in improving their health and well-being.

Whole health and AFHS are complementary approaches to care that can work to empower veterans (as well as caregivers and clinicians) to align services with what matters most to veterans. Lessons such as standardizing person-centered assessments of what matters, creating supportive structures to better align care with veterans’ priorities, and identifying meaningful veteran and system-level outcomes to help sustain transformational change can be applied from whole health to AFHS. Together these programs have the potential to enhance overall health outcomes and quality of life for veterans.

The COVID-19 pandemic established a new normal for health care delivery, with leaders rethinking core practices to survive and thrive in a changing environment and improve the health and well-being of patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is embracing a shift in focus from “what is the matter” to “what really matters” to address pre- and postpandemic challenges through a whole health approach.1 Initially conceptualized by the VHA in 2011, whole health “is an approach to health care that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being so that they can live their life to the fullest.”1 Whole health integrates evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage pain; this includes acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, yoga, massage therapy, guided imagery, biofeedback, and clinical hypnosis.1 The VHA now recognizes well-being as a core value, helping clinicians respond to emerging challenges related to the social determinants of health (eg, access to health care, physical activity, and healthy foods) and guiding health care decision making.1,2

Well-being through empowerment—elements of whole health and Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS)—encourages health care institutions to work with employees, patients, and other stakeholders to address global challenges, clinician burnout, and social issues faced by their communities. This approach focuses on life’s purpose and meaning for individuals and inspires leaders to engage with patients, staff, and communities in new, impactful ways by focusing on wellbeing and wholeness rather than illness and disease. Having a higher sense of purpose is associated with lower all-cause mortality, reduced risk of specific diseases, better health behaviors, greater use of preventive services, and fewer hospital days of care.3

This article describes how AFHS supports the well-being of older adults and aligns with the whole health model of care. It also outlines the VHA investment to transform health care to be more person-centered by documenting what matters in the electronic health record (EHR).

AGE-FRIENDLY CARE

Given that nearly half of veterans enrolled in the VHA are aged ≥ 65 years, there is an increased need to identify models of care to support this aging population.4 This is especially critical because older veterans often have multiple chronic conditions and complex care needs that benefit from a whole person approach. The AFHS movement aims to provide evidence-based care aligned with what matters to older adults and provides a mechanism for transforming care to meet the needs of older veterans. This includes addressing age-related health concerns while promoting optimal health outcomes and quality of life. AFHS follows the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.5 The 4Ms serve as a guide for the health care of older adults in any setting, where each “M” is assessed and acted on to support what matters.5 Since 2020, > 390 teams have developed a plan to implement the 4Ms at 156 VHA facilities, demonstrating the VHA commitment to transforming health care for veterans.6

When VHA teams join the AFHS movement, they may also engage older veterans in a whole health system (WHS) (Figure). While AFHS is designed to improve care for patients aged ≥ 65 years, it also complements whole health, a person-centered approach available to all veterans enrolled in the VHA. Through the WHS and AFHS, veterans are empowered and equipped to take charge of their health and well-being through conversations about their unique goals, preferences, and health priorities.4 Clinicians are challenged to assess what matters by asking questions like, “What brings you joy?” and, “How can we help you meet your health goals?”1,5 These questions shift the conversation from disease-based treatment and enable clinicians to better understand the veteran as a person.1,5

For whole health and AFHS, conversations about what matters are anchored in the veteran’s goals and preferences, especially those facing a significant health change (ie, a new diagnosis or treatment decision).5,7 Together, the veteran’s goals and priorities serve as the foundation for developing person-centered care plans that often go beyond conventional medical treatments to address the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of health.

SYSTEM-WIDE DIRECTIVE

The WHS enhances AFHS discussions about what matters to veterans by adding a system-level lens for conceptualizing health care delivery by leveraging the 3 components of WHS: the “pathway,” well-being programs, and whole health clinical care.

The Pathway

Discovering what matters, or the veteran’s “mission, aspiration, and purpose,” begins with the WHS pathway. When stepping into the pathway, veterans begin completing a personal health inventory, or “walking the circle of health,” which encourages self-reflection that focuses on components of their life that can influence health and well-being.1,8 The circle of health offers a visual representation of the 4 most important aspects of health and well-being: First, “Me” at the center as an individual who is the expert on their life, values, goals, and priorities. Only the individual can know what really matters through mindful awareness and what works for their life. Second, self-care consists of 8 areas that impact health and wellbeing: working your body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind. Third, professional care consists of prevention, conventional care, and complementary care. Finally, the community that supports the individual.

Well-Being Programs