User login

Ready for post-acute care?

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

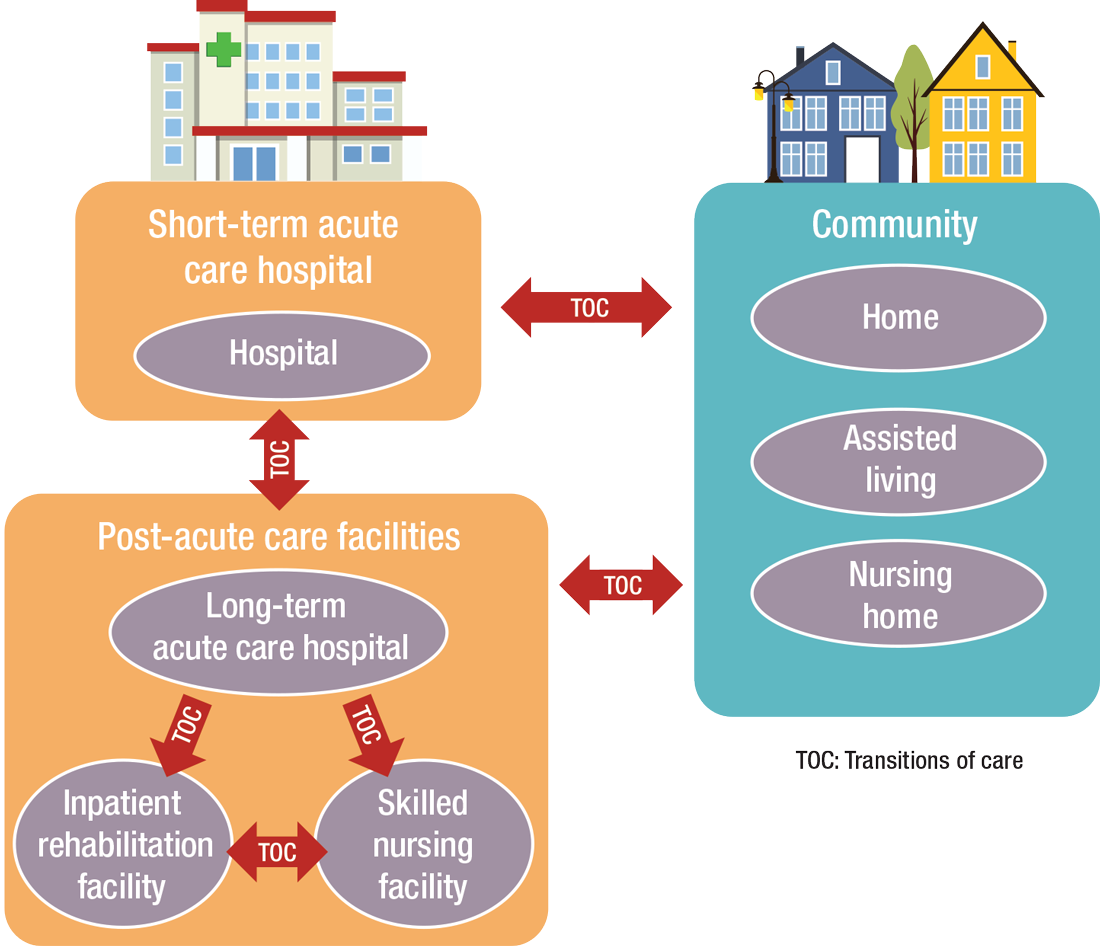

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

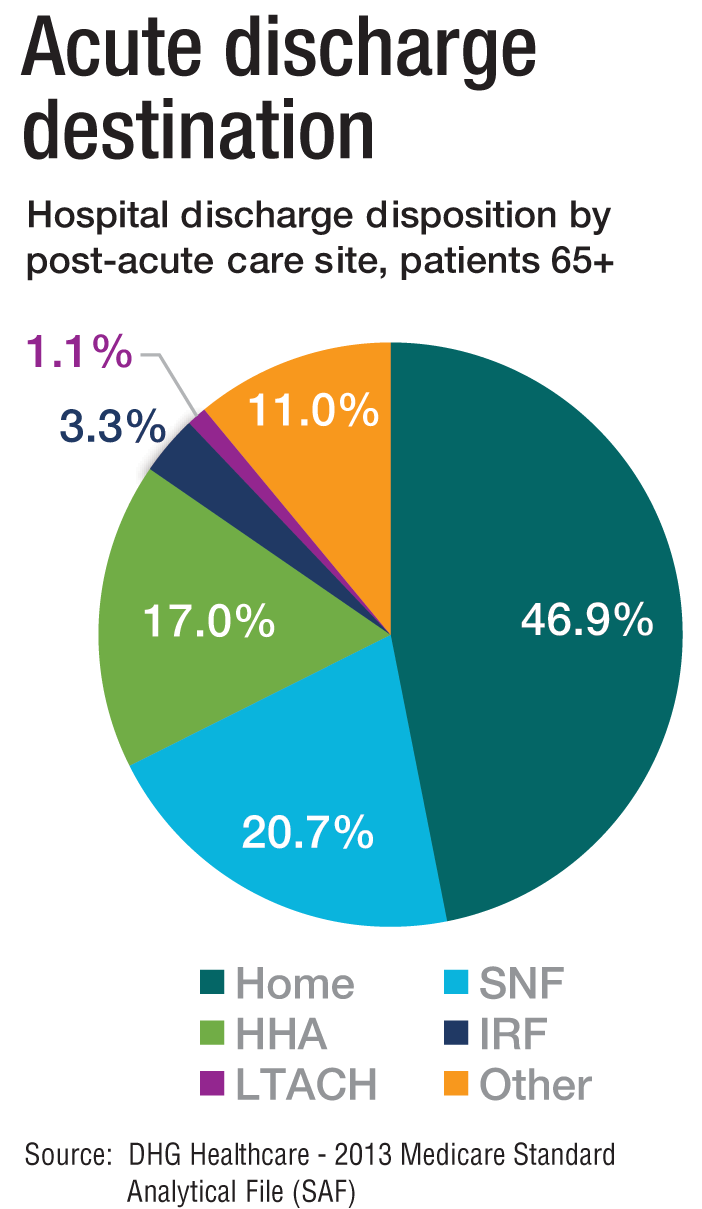

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

Seeing the Future of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalists touch the lives of patients and shape health systems’ practices and health policy on a national and international scale according to an editorial titled “The Next 20 Years of Hospital Medicine: Continuing to Foster the Mind, Heart, and Soul of Our Field.”1

“This editorial was my reflection on the ‘Year of the Hospitalist’ and where I think the field needs to go in terms of its professionalism, patient-centeredness, and science,” says author Andrew D. Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, who has worked as a hospitalist for more than 20 years. “We’ve grown extraordinarily fast, but some important aspects of our work need to be fleshed out.”

One example: Hospital medicine has been growing research capacity at a rate that is slower than the field overall, a problem due in part to funding limitations for fellowships and early-career awards, which has restricted the pipeline of young researchers. “Slow growth may also be a result of an emphasis on health systems rather than diseases,” Dr. Auerbach says.

Dr. Auerbach also is concerned about making sure the field of hospital medicine is attractive and sustainable as a career.

“A large amount of burnout can be attributed to things like EHRs, billing, etc., that are real dissatisfiers, but another broad area is in reconnecting with our professional/personal reasons for becoming physicians,” he says. “That needs to be reinvigorated. I also feel very strongly that we need to develop our own research agenda and grow research networks, but even those will need to be reconnected to patient needs more directly.”

Reference

- Auerbach AD. The next 20 years of hospital medicine: continuing to foster the mind, heart, and soul of our field [published online ahead of print July 4, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2631.

Hospitalists touch the lives of patients and shape health systems’ practices and health policy on a national and international scale according to an editorial titled “The Next 20 Years of Hospital Medicine: Continuing to Foster the Mind, Heart, and Soul of Our Field.”1

“This editorial was my reflection on the ‘Year of the Hospitalist’ and where I think the field needs to go in terms of its professionalism, patient-centeredness, and science,” says author Andrew D. Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, who has worked as a hospitalist for more than 20 years. “We’ve grown extraordinarily fast, but some important aspects of our work need to be fleshed out.”

One example: Hospital medicine has been growing research capacity at a rate that is slower than the field overall, a problem due in part to funding limitations for fellowships and early-career awards, which has restricted the pipeline of young researchers. “Slow growth may also be a result of an emphasis on health systems rather than diseases,” Dr. Auerbach says.

Dr. Auerbach also is concerned about making sure the field of hospital medicine is attractive and sustainable as a career.

“A large amount of burnout can be attributed to things like EHRs, billing, etc., that are real dissatisfiers, but another broad area is in reconnecting with our professional/personal reasons for becoming physicians,” he says. “That needs to be reinvigorated. I also feel very strongly that we need to develop our own research agenda and grow research networks, but even those will need to be reconnected to patient needs more directly.”

Reference

- Auerbach AD. The next 20 years of hospital medicine: continuing to foster the mind, heart, and soul of our field [published online ahead of print July 4, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2631.

Hospitalists touch the lives of patients and shape health systems’ practices and health policy on a national and international scale according to an editorial titled “The Next 20 Years of Hospital Medicine: Continuing to Foster the Mind, Heart, and Soul of Our Field.”1

“This editorial was my reflection on the ‘Year of the Hospitalist’ and where I think the field needs to go in terms of its professionalism, patient-centeredness, and science,” says author Andrew D. Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, who has worked as a hospitalist for more than 20 years. “We’ve grown extraordinarily fast, but some important aspects of our work need to be fleshed out.”

One example: Hospital medicine has been growing research capacity at a rate that is slower than the field overall, a problem due in part to funding limitations for fellowships and early-career awards, which has restricted the pipeline of young researchers. “Slow growth may also be a result of an emphasis on health systems rather than diseases,” Dr. Auerbach says.

Dr. Auerbach also is concerned about making sure the field of hospital medicine is attractive and sustainable as a career.

“A large amount of burnout can be attributed to things like EHRs, billing, etc., that are real dissatisfiers, but another broad area is in reconnecting with our professional/personal reasons for becoming physicians,” he says. “That needs to be reinvigorated. I also feel very strongly that we need to develop our own research agenda and grow research networks, but even those will need to be reconnected to patient needs more directly.”

Reference

- Auerbach AD. The next 20 years of hospital medicine: continuing to foster the mind, heart, and soul of our field [published online ahead of print July 4, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2631.

Promoting the Health of Healthcare Employees

Provisions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) encourage hospitals to work with their communities to improve population health. Like so many things, these efforts can and should begin at home—in this case, the hospital itself. Health and wellness programs for healthcare workers need to be emphasized, according to “Health and Wellness Programs for Hospital Employees: Results from a 2015 American Hospital Association Survey.”1

Such efforts allow healthcare workers to lead by example.

“To help create a culture of health, hospitals and health systems can provide leadership, and hospital employees can be role models, for health and wellness in their communities,” according to the report. “Developing health and wellness strategies and programs at hospitals will help establish an environment that provides the support, resources, and incentives for hospital employees to serve as such role models.”

Developing health and wellness programs can also help hospitals achieve the public health goals of the Healthy People 2020 initiative from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

To find out how hospitals are doing in this work, the 26-question survey was done in 2010 and again in 2015 and sent to approximately 6,000 hospitals in the United States. Response rate was 15% in 2010 and 18% in 2015. Some of the findings include:

- About the same number of hospitals have a health and wellness program or other initiative(s) for employees (86% in 2010 and 87% in 2015); however, the types of health and wellness programs and benefits that hospitals offer to their employees increased.

- The number of hospitals with 70% to 90% or more of employees participating in health and wellness programs increased from 19% in 2010 to 31% in 2015.

- The number of hospitals offering health and wellness programs to people in the community increased from 19% in 2010 to 66% in 2015.

- The number of hospitals offering incentives for participating in health and wellness programs increased as did the value of incentives, with more hospitals giving $500 or more to employees (7% in 2010 and 29% in 2015).

Reference

- Health Research & Educational Trust. Health and wellness programs for hospital employees: results from a 2015 American Hospital Association survey. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Provisions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) encourage hospitals to work with their communities to improve population health. Like so many things, these efforts can and should begin at home—in this case, the hospital itself. Health and wellness programs for healthcare workers need to be emphasized, according to “Health and Wellness Programs for Hospital Employees: Results from a 2015 American Hospital Association Survey.”1

Such efforts allow healthcare workers to lead by example.

“To help create a culture of health, hospitals and health systems can provide leadership, and hospital employees can be role models, for health and wellness in their communities,” according to the report. “Developing health and wellness strategies and programs at hospitals will help establish an environment that provides the support, resources, and incentives for hospital employees to serve as such role models.”

Developing health and wellness programs can also help hospitals achieve the public health goals of the Healthy People 2020 initiative from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

To find out how hospitals are doing in this work, the 26-question survey was done in 2010 and again in 2015 and sent to approximately 6,000 hospitals in the United States. Response rate was 15% in 2010 and 18% in 2015. Some of the findings include:

- About the same number of hospitals have a health and wellness program or other initiative(s) for employees (86% in 2010 and 87% in 2015); however, the types of health and wellness programs and benefits that hospitals offer to their employees increased.

- The number of hospitals with 70% to 90% or more of employees participating in health and wellness programs increased from 19% in 2010 to 31% in 2015.

- The number of hospitals offering health and wellness programs to people in the community increased from 19% in 2010 to 66% in 2015.

- The number of hospitals offering incentives for participating in health and wellness programs increased as did the value of incentives, with more hospitals giving $500 or more to employees (7% in 2010 and 29% in 2015).

Reference

- Health Research & Educational Trust. Health and wellness programs for hospital employees: results from a 2015 American Hospital Association survey. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Provisions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) encourage hospitals to work with their communities to improve population health. Like so many things, these efforts can and should begin at home—in this case, the hospital itself. Health and wellness programs for healthcare workers need to be emphasized, according to “Health and Wellness Programs for Hospital Employees: Results from a 2015 American Hospital Association Survey.”1

Such efforts allow healthcare workers to lead by example.

“To help create a culture of health, hospitals and health systems can provide leadership, and hospital employees can be role models, for health and wellness in their communities,” according to the report. “Developing health and wellness strategies and programs at hospitals will help establish an environment that provides the support, resources, and incentives for hospital employees to serve as such role models.”

Developing health and wellness programs can also help hospitals achieve the public health goals of the Healthy People 2020 initiative from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

To find out how hospitals are doing in this work, the 26-question survey was done in 2010 and again in 2015 and sent to approximately 6,000 hospitals in the United States. Response rate was 15% in 2010 and 18% in 2015. Some of the findings include:

- About the same number of hospitals have a health and wellness program or other initiative(s) for employees (86% in 2010 and 87% in 2015); however, the types of health and wellness programs and benefits that hospitals offer to their employees increased.

- The number of hospitals with 70% to 90% or more of employees participating in health and wellness programs increased from 19% in 2010 to 31% in 2015.

- The number of hospitals offering health and wellness programs to people in the community increased from 19% in 2010 to 66% in 2015.

- The number of hospitals offering incentives for participating in health and wellness programs increased as did the value of incentives, with more hospitals giving $500 or more to employees (7% in 2010 and 29% in 2015).

Reference

- Health Research & Educational Trust. Health and wellness programs for hospital employees: results from a 2015 American Hospital Association survey. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Strategies for Preventing Patient Falls

Between 700,000 and 1 million people fall each year in U.S. hospitals, and about a third of those result in injuries that add an additional 6.3 days to hospital stays, according to a report from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Some 11,000 falls are fatal. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare has now issued a report on the subject called “Preventing Patient Falls: A Systematic Approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare Project.”1

“We try to pick those topics that healthcare organizations just haven’t been able to fully tackle even though they’ve put a lot of time and resources into trying to fix them,” says Kelly Barnes, MS, a center project lead in the Center for Transforming Healthcare at The Joint Commission.

The Joint Commission project involved seven hospitals that used Robust Process Improvement, which incorporates tools from Lean Six Sigma and change management methodologies, to reduce falls with injury on inpatient pilot units within their organizations.

During the project, each organization identified the specific factors that led to falls with injury in their environment and developed solutions targeted to those factors. The organizations identified 30 root causes and developed 21 targeted solutions. Because the contributing factors were different at each organization, solution sets were unique to each. Afterward, the organizations saw an aggregate 35% reduction in falls and a 62% reduction in falls with injury.

“One of the takeaways is that you really need support across an organization to have success,” Barnes says. “The more engaged the entire organization is from top down all the way to the bottom, the more successful people are in solving the problems.”

The study resulted in a Targeted Solutions Tool (TST), free to all Joint Commission–accredited customers, to help hospitals.

“You can put your data right into the tool,” Barnes says. “It tells you what your top contributing factors are, and it gives you the solutions that have worked for those contributing factors at other organizations.”

Reference

Health Research & Educational Trust. Preventing patient falls: a systematic approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare project. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Between 700,000 and 1 million people fall each year in U.S. hospitals, and about a third of those result in injuries that add an additional 6.3 days to hospital stays, according to a report from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Some 11,000 falls are fatal. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare has now issued a report on the subject called “Preventing Patient Falls: A Systematic Approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare Project.”1

“We try to pick those topics that healthcare organizations just haven’t been able to fully tackle even though they’ve put a lot of time and resources into trying to fix them,” says Kelly Barnes, MS, a center project lead in the Center for Transforming Healthcare at The Joint Commission.

The Joint Commission project involved seven hospitals that used Robust Process Improvement, which incorporates tools from Lean Six Sigma and change management methodologies, to reduce falls with injury on inpatient pilot units within their organizations.

During the project, each organization identified the specific factors that led to falls with injury in their environment and developed solutions targeted to those factors. The organizations identified 30 root causes and developed 21 targeted solutions. Because the contributing factors were different at each organization, solution sets were unique to each. Afterward, the organizations saw an aggregate 35% reduction in falls and a 62% reduction in falls with injury.

“One of the takeaways is that you really need support across an organization to have success,” Barnes says. “The more engaged the entire organization is from top down all the way to the bottom, the more successful people are in solving the problems.”

The study resulted in a Targeted Solutions Tool (TST), free to all Joint Commission–accredited customers, to help hospitals.

“You can put your data right into the tool,” Barnes says. “It tells you what your top contributing factors are, and it gives you the solutions that have worked for those contributing factors at other organizations.”

Reference

Health Research & Educational Trust. Preventing patient falls: a systematic approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare project. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Between 700,000 and 1 million people fall each year in U.S. hospitals, and about a third of those result in injuries that add an additional 6.3 days to hospital stays, according to a report from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Some 11,000 falls are fatal. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare has now issued a report on the subject called “Preventing Patient Falls: A Systematic Approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare Project.”1

“We try to pick those topics that healthcare organizations just haven’t been able to fully tackle even though they’ve put a lot of time and resources into trying to fix them,” says Kelly Barnes, MS, a center project lead in the Center for Transforming Healthcare at The Joint Commission.

The Joint Commission project involved seven hospitals that used Robust Process Improvement, which incorporates tools from Lean Six Sigma and change management methodologies, to reduce falls with injury on inpatient pilot units within their organizations.

During the project, each organization identified the specific factors that led to falls with injury in their environment and developed solutions targeted to those factors. The organizations identified 30 root causes and developed 21 targeted solutions. Because the contributing factors were different at each organization, solution sets were unique to each. Afterward, the organizations saw an aggregate 35% reduction in falls and a 62% reduction in falls with injury.

“One of the takeaways is that you really need support across an organization to have success,” Barnes says. “The more engaged the entire organization is from top down all the way to the bottom, the more successful people are in solving the problems.”

The study resulted in a Targeted Solutions Tool (TST), free to all Joint Commission–accredited customers, to help hospitals.

“You can put your data right into the tool,” Barnes says. “It tells you what your top contributing factors are, and it gives you the solutions that have worked for those contributing factors at other organizations.”

Reference

Health Research & Educational Trust. Preventing patient falls: a systematic approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare project. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Helping Patients Quit Smoking

Inpatient hospitalization can be a key time for patients to quit smoking, according to an abstract called “No More Butts: An Automated System for Inpatient Smoking Cessation Team Consults.”1

“Tobacco smoking continues to be one of the most important public health threats that we face,” says lead author Sujatha Sankaran, MD, assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director of smoking cessation at the University of California, San Francisco. “Hospitalization is an extremely important moment and provides an excellent opportunity to counsel and provide cessation resources for people who are concerned about their health.”

Inpatients who receive smoking cessation counseling, nicotine replacement, and referral to outpatient resources have increased quit rates six weeks after hospital discharge, their research showed.

However, according to the abstract, in 2014:

- 34.5% of tobacco users admitted to one 600-bed academic hospital were documented as having received and accepted tobacco cessation counseling

- 45.7% of tobacco users received nicotine replacement therapy

- 1.35% of tobacco users received after-discharge consultations to outpatient smoking cessation resources

Researchers piloted a system in which a dedicated respiratory therapist–staffed smoking cessation consult service was trained to provide targeted tobacco cessation services to all inpatients who use tobacco. Of 1944 patients identified as using tobacco, 1545 received and accepted cessation counseling from a trained member of the Smoking Cessation Team, 1526 received nicotine replacement therapy, and 464 received an electronic referral to either a telephone or in-person quit line

“Hospitalists know firsthand the serious harm that tobacco use causes to patients but often are overwhelmed by the acute issues of patients and are unable to fully address tobacco use with hospitalized patients,” Dr. Sankaran says. “An automated cessation service can help lessen this burden by providing automatic cessation resources to all tobacco users.”

Reference

- Sankaran S, Burke R, O’Keefe S. No more butts: an automated system for inpatient smoking cessation team consults [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed November 9, 2016.

Inpatient hospitalization can be a key time for patients to quit smoking, according to an abstract called “No More Butts: An Automated System for Inpatient Smoking Cessation Team Consults.”1

“Tobacco smoking continues to be one of the most important public health threats that we face,” says lead author Sujatha Sankaran, MD, assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director of smoking cessation at the University of California, San Francisco. “Hospitalization is an extremely important moment and provides an excellent opportunity to counsel and provide cessation resources for people who are concerned about their health.”

Inpatients who receive smoking cessation counseling, nicotine replacement, and referral to outpatient resources have increased quit rates six weeks after hospital discharge, their research showed.

However, according to the abstract, in 2014:

- 34.5% of tobacco users admitted to one 600-bed academic hospital were documented as having received and accepted tobacco cessation counseling

- 45.7% of tobacco users received nicotine replacement therapy

- 1.35% of tobacco users received after-discharge consultations to outpatient smoking cessation resources

Researchers piloted a system in which a dedicated respiratory therapist–staffed smoking cessation consult service was trained to provide targeted tobacco cessation services to all inpatients who use tobacco. Of 1944 patients identified as using tobacco, 1545 received and accepted cessation counseling from a trained member of the Smoking Cessation Team, 1526 received nicotine replacement therapy, and 464 received an electronic referral to either a telephone or in-person quit line

“Hospitalists know firsthand the serious harm that tobacco use causes to patients but often are overwhelmed by the acute issues of patients and are unable to fully address tobacco use with hospitalized patients,” Dr. Sankaran says. “An automated cessation service can help lessen this burden by providing automatic cessation resources to all tobacco users.”

Reference

- Sankaran S, Burke R, O’Keefe S. No more butts: an automated system for inpatient smoking cessation team consults [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed November 9, 2016.

Inpatient hospitalization can be a key time for patients to quit smoking, according to an abstract called “No More Butts: An Automated System for Inpatient Smoking Cessation Team Consults.”1

“Tobacco smoking continues to be one of the most important public health threats that we face,” says lead author Sujatha Sankaran, MD, assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director of smoking cessation at the University of California, San Francisco. “Hospitalization is an extremely important moment and provides an excellent opportunity to counsel and provide cessation resources for people who are concerned about their health.”

Inpatients who receive smoking cessation counseling, nicotine replacement, and referral to outpatient resources have increased quit rates six weeks after hospital discharge, their research showed.

However, according to the abstract, in 2014:

- 34.5% of tobacco users admitted to one 600-bed academic hospital were documented as having received and accepted tobacco cessation counseling

- 45.7% of tobacco users received nicotine replacement therapy

- 1.35% of tobacco users received after-discharge consultations to outpatient smoking cessation resources

Researchers piloted a system in which a dedicated respiratory therapist–staffed smoking cessation consult service was trained to provide targeted tobacco cessation services to all inpatients who use tobacco. Of 1944 patients identified as using tobacco, 1545 received and accepted cessation counseling from a trained member of the Smoking Cessation Team, 1526 received nicotine replacement therapy, and 464 received an electronic referral to either a telephone or in-person quit line

“Hospitalists know firsthand the serious harm that tobacco use causes to patients but often are overwhelmed by the acute issues of patients and are unable to fully address tobacco use with hospitalized patients,” Dr. Sankaran says. “An automated cessation service can help lessen this burden by providing automatic cessation resources to all tobacco users.”

Reference

- Sankaran S, Burke R, O’Keefe S. No more butts: an automated system for inpatient smoking cessation team consults [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed November 9, 2016.

Predicting 30-Day Readmissions

Rates of 30-day readmissions, which are both common and difficult to predict, are of major concern to hospitalists.

“Unfortunately, interventions developed to date have not been universally successful in preventing hospital readmissions for various medical conditions and patient types,” according to a recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. “One potential explanation for this is the inability to reliably predict which patients are at risk for readmission to better target preventative interventions.”

This fact led the authors to perform a study to determine whether the occurrence of automated clinical deterioration alerts (CDAs) could predict 30-day hospital readmission. The 36 variables in the CDA algorithm included age, radiologic agents, and temperature. The retrospective study assessed 3,015 patients admitted to eight general medicine units for all-cause 30-day readmission. Of these, 1,141 patients triggered a CDA, and they were significantly more likely to have a 30-day readmission compared to those who did not trigger a CDA (23.6% versus 15.9%).

The researchers concluded that readily identifiable clinical variables can be identified that predict 30-day readmission.

“It may be important to include these variables in existing prediction tools if pay for performance and across-institution comparisons are to be ‘fair’ to institutions that care for more seriously ill patients,” they write. “The development of an accurate real-time early warning system has the potential to identify patients at risk for various adverse outcomes including clinical deterioration, hospital death and post-discharge readmission. By identifying patients at greatest risk for readmission, valuable healthcare resources can be better targeted to such populations.”

Reference

- Micek ST, Samant M, Bailey T, et al. Real-time automated clinical deterioration alerts predict thirty-day hospital readmission [published online ahead of print June 3, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2617.

Quick Byte

The Cost of Vaccine Avoidance

Many Americans avoid their recommended vaccines: For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that only 42% of U.S. adults age 18 or older received the flu vaccine during the 2015–2016 flu season. A study recently released online by Health Affairs calculated the annual cost of the diseases associated with 10 vaccines the CDC recommends for adults. In 2015, that economic burden was $8.95 billion. A full 80% of that—$7.1 billion—was attributed to unvaccinated people.

Reference

- The cost of US adult vaccine avoidance: $8.95 billion in 2015. Health Affairs website. Accessed October 17, 2016

Rates of 30-day readmissions, which are both common and difficult to predict, are of major concern to hospitalists.

“Unfortunately, interventions developed to date have not been universally successful in preventing hospital readmissions for various medical conditions and patient types,” according to a recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. “One potential explanation for this is the inability to reliably predict which patients are at risk for readmission to better target preventative interventions.”

This fact led the authors to perform a study to determine whether the occurrence of automated clinical deterioration alerts (CDAs) could predict 30-day hospital readmission. The 36 variables in the CDA algorithm included age, radiologic agents, and temperature. The retrospective study assessed 3,015 patients admitted to eight general medicine units for all-cause 30-day readmission. Of these, 1,141 patients triggered a CDA, and they were significantly more likely to have a 30-day readmission compared to those who did not trigger a CDA (23.6% versus 15.9%).

The researchers concluded that readily identifiable clinical variables can be identified that predict 30-day readmission.

“It may be important to include these variables in existing prediction tools if pay for performance and across-institution comparisons are to be ‘fair’ to institutions that care for more seriously ill patients,” they write. “The development of an accurate real-time early warning system has the potential to identify patients at risk for various adverse outcomes including clinical deterioration, hospital death and post-discharge readmission. By identifying patients at greatest risk for readmission, valuable healthcare resources can be better targeted to such populations.”

Reference

- Micek ST, Samant M, Bailey T, et al. Real-time automated clinical deterioration alerts predict thirty-day hospital readmission [published online ahead of print June 3, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2617.

Quick Byte

The Cost of Vaccine Avoidance

Many Americans avoid their recommended vaccines: For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that only 42% of U.S. adults age 18 or older received the flu vaccine during the 2015–2016 flu season. A study recently released online by Health Affairs calculated the annual cost of the diseases associated with 10 vaccines the CDC recommends for adults. In 2015, that economic burden was $8.95 billion. A full 80% of that—$7.1 billion—was attributed to unvaccinated people.

Reference

- The cost of US adult vaccine avoidance: $8.95 billion in 2015. Health Affairs website. Accessed October 17, 2016

Rates of 30-day readmissions, which are both common and difficult to predict, are of major concern to hospitalists.

“Unfortunately, interventions developed to date have not been universally successful in preventing hospital readmissions for various medical conditions and patient types,” according to a recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. “One potential explanation for this is the inability to reliably predict which patients are at risk for readmission to better target preventative interventions.”

This fact led the authors to perform a study to determine whether the occurrence of automated clinical deterioration alerts (CDAs) could predict 30-day hospital readmission. The 36 variables in the CDA algorithm included age, radiologic agents, and temperature. The retrospective study assessed 3,015 patients admitted to eight general medicine units for all-cause 30-day readmission. Of these, 1,141 patients triggered a CDA, and they were significantly more likely to have a 30-day readmission compared to those who did not trigger a CDA (23.6% versus 15.9%).

The researchers concluded that readily identifiable clinical variables can be identified that predict 30-day readmission.

“It may be important to include these variables in existing prediction tools if pay for performance and across-institution comparisons are to be ‘fair’ to institutions that care for more seriously ill patients,” they write. “The development of an accurate real-time early warning system has the potential to identify patients at risk for various adverse outcomes including clinical deterioration, hospital death and post-discharge readmission. By identifying patients at greatest risk for readmission, valuable healthcare resources can be better targeted to such populations.”

Reference

- Micek ST, Samant M, Bailey T, et al. Real-time automated clinical deterioration alerts predict thirty-day hospital readmission [published online ahead of print June 3, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2617.

Quick Byte

The Cost of Vaccine Avoidance

Many Americans avoid their recommended vaccines: For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that only 42% of U.S. adults age 18 or older received the flu vaccine during the 2015–2016 flu season. A study recently released online by Health Affairs calculated the annual cost of the diseases associated with 10 vaccines the CDC recommends for adults. In 2015, that economic burden was $8.95 billion. A full 80% of that—$7.1 billion—was attributed to unvaccinated people.

Reference

- The cost of US adult vaccine avoidance: $8.95 billion in 2015. Health Affairs website. Accessed October 17, 2016

Ramping Up Telehealth’s Possibilities

Twenty percent of Americans live in areas where there are shortages of physicians, according to a policy brief in Health Affairs. Some analysts believe the answer to this problem is telehealth, which they say could also save the healthcare industry some $4.28 billion annually.

While the Affordable Care Act signaled a move toward telehealth development at the federal level (through Medicare), states still largely govern coverage of telehealth services by Medicaid or private insurers.

“Currently there is no uniform legal approach to telehealth, and this continues to be a major challenge in its provision. In particular, concerns about reimbursements, for both private insurers and public programs such as Medicaid, continue to limit the implementation and use of telehealth services,” according to the brief.

Now, Congress is considering the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act, intended to modernize the way Medicare reimburses telehealth services and to expand locations and coverage. To enjoy the benefits of telehealth services, states are likely to move toward full-parity laws for the services, the brief notes.

“Without parity, there are limited incentives for the development of telehealth or for providers to move toward telehealth services,” according to the brief. “If there are no incentives to use telehealth, then providers will continue to focus on in-person care, which will keep healthcare costs high, continue to create access issues, and possibly provide lesser standards of care for chronic disease patients who benefit from remote monitoring.”

Reference

1. Yang T. Telehealth parity laws. Health Affairs Website. Accessed October 17, 2016.

Twenty percent of Americans live in areas where there are shortages of physicians, according to a policy brief in Health Affairs. Some analysts believe the answer to this problem is telehealth, which they say could also save the healthcare industry some $4.28 billion annually.

While the Affordable Care Act signaled a move toward telehealth development at the federal level (through Medicare), states still largely govern coverage of telehealth services by Medicaid or private insurers.

“Currently there is no uniform legal approach to telehealth, and this continues to be a major challenge in its provision. In particular, concerns about reimbursements, for both private insurers and public programs such as Medicaid, continue to limit the implementation and use of telehealth services,” according to the brief.

Now, Congress is considering the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act, intended to modernize the way Medicare reimburses telehealth services and to expand locations and coverage. To enjoy the benefits of telehealth services, states are likely to move toward full-parity laws for the services, the brief notes.

“Without parity, there are limited incentives for the development of telehealth or for providers to move toward telehealth services,” according to the brief. “If there are no incentives to use telehealth, then providers will continue to focus on in-person care, which will keep healthcare costs high, continue to create access issues, and possibly provide lesser standards of care for chronic disease patients who benefit from remote monitoring.”

Reference

1. Yang T. Telehealth parity laws. Health Affairs Website. Accessed October 17, 2016.

Twenty percent of Americans live in areas where there are shortages of physicians, according to a policy brief in Health Affairs. Some analysts believe the answer to this problem is telehealth, which they say could also save the healthcare industry some $4.28 billion annually.

While the Affordable Care Act signaled a move toward telehealth development at the federal level (through Medicare), states still largely govern coverage of telehealth services by Medicaid or private insurers.

“Currently there is no uniform legal approach to telehealth, and this continues to be a major challenge in its provision. In particular, concerns about reimbursements, for both private insurers and public programs such as Medicaid, continue to limit the implementation and use of telehealth services,” according to the brief.

Now, Congress is considering the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act, intended to modernize the way Medicare reimburses telehealth services and to expand locations and coverage. To enjoy the benefits of telehealth services, states are likely to move toward full-parity laws for the services, the brief notes.

“Without parity, there are limited incentives for the development of telehealth or for providers to move toward telehealth services,” according to the brief. “If there are no incentives to use telehealth, then providers will continue to focus on in-person care, which will keep healthcare costs high, continue to create access issues, and possibly provide lesser standards of care for chronic disease patients who benefit from remote monitoring.”

Reference

1. Yang T. Telehealth parity laws. Health Affairs Website. Accessed October 17, 2016.

Improving Hospital Telemetry Usage

Hospitalists often rely on inpatient telemetry monitoring to identify arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation, but research has shown that its inappropriate usage increases costs to the healthcare system. An abstract presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine looked at one hospital’s telemetry usage and how it might be improved.

The study revolved around a progress note template the authors developed, which incorporated documentation for telemetry use indications and need for telemetry continuation on non-ICU internal medicine services. The authors also provided an educational session describing American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) telemetry use guidelines for internal medicine residents with a pretest and posttest.

Application of ACA/AHA guidelines was assessed with five scenarios before and after instruction on the guidelines. On pretest, only 29% of trainees answered all five questions correctly; on posttest, 63% did. A comparison between charts of admitted patients with telemetry orders from 2015 with charts from 2013 indicated that the appropriate initiation of telemetry improved significantly as did telemetry documentation. Inappropriate continuation rates were cut in half.

The success of the study suggests further work.

“We plan expansion of telemetry utilization education to internal medicine faculty and nursing to encourage daily review of telemetry usage,” the authors write. “We are also working to develop telemetry orders that end during standard work hours to prevent inadvertent continuation by overnight providers.”

Reference

1. Kuehn C, Steyers CM III, Glenn K, Fang M. Resident-based telemetry utilization innovations lead to improved outcomes [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed October 17, 2016.

Hospitalists often rely on inpatient telemetry monitoring to identify arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation, but research has shown that its inappropriate usage increases costs to the healthcare system. An abstract presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine looked at one hospital’s telemetry usage and how it might be improved.

The study revolved around a progress note template the authors developed, which incorporated documentation for telemetry use indications and need for telemetry continuation on non-ICU internal medicine services. The authors also provided an educational session describing American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) telemetry use guidelines for internal medicine residents with a pretest and posttest.

Application of ACA/AHA guidelines was assessed with five scenarios before and after instruction on the guidelines. On pretest, only 29% of trainees answered all five questions correctly; on posttest, 63% did. A comparison between charts of admitted patients with telemetry orders from 2015 with charts from 2013 indicated that the appropriate initiation of telemetry improved significantly as did telemetry documentation. Inappropriate continuation rates were cut in half.

The success of the study suggests further work.

“We plan expansion of telemetry utilization education to internal medicine faculty and nursing to encourage daily review of telemetry usage,” the authors write. “We are also working to develop telemetry orders that end during standard work hours to prevent inadvertent continuation by overnight providers.”

Reference

1. Kuehn C, Steyers CM III, Glenn K, Fang M. Resident-based telemetry utilization innovations lead to improved outcomes [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed October 17, 2016.

Hospitalists often rely on inpatient telemetry monitoring to identify arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation, but research has shown that its inappropriate usage increases costs to the healthcare system. An abstract presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine looked at one hospital’s telemetry usage and how it might be improved.

The study revolved around a progress note template the authors developed, which incorporated documentation for telemetry use indications and need for telemetry continuation on non-ICU internal medicine services. The authors also provided an educational session describing American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) telemetry use guidelines for internal medicine residents with a pretest and posttest.

Application of ACA/AHA guidelines was assessed with five scenarios before and after instruction on the guidelines. On pretest, only 29% of trainees answered all five questions correctly; on posttest, 63% did. A comparison between charts of admitted patients with telemetry orders from 2015 with charts from 2013 indicated that the appropriate initiation of telemetry improved significantly as did telemetry documentation. Inappropriate continuation rates were cut in half.

The success of the study suggests further work.