User login

Special Report II: Tackling Burnout

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Revolutionizing Headache Medicine: The Role of Artificial Intelligence

As we move further into the 21st century, technology continues to revolutionize various facets of our lives. Healthcare is a prime example. Advances in technology have dramatically reshaped the way we develop medications, diagnose diseases, and enhance patient care. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and the widespread adoption of digital health technologies have marked a significant milestone in improving the quality of care. AI, with its ability to leverage algorithms, deep learning, and machine learning to process data, make decisions, and perform tasks autonomously, is becoming an integral part of modern society. It is embedded in various technologies that we rely on daily, from smartphones and smart home devices to content recommendations on streaming services and social media platforms.

In healthcare, AI has applications in numerous fields, such as radiology. AI streamlines processes such as organizing patient appointments, optimizing radiation protocols for safety and efficiency, and enhancing the documentation process through advanced image analysis. AI technology plays an integral role in imaging tasks like image enhancement, lesion detection, and precise measurement. In difficult-to-interpret radiologic studies, such as some mammography images, it can be a crucial aid to the radiologist. Additionally, the use of AI has significantly improved remote patient monitoring that enables healthcare professionals to monitor and assess patient conditions without needing in-person visits. Remote patient monitoring gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to be a valuable tool in post pandemic care. Study results have highlighted that AI-driven ambient dictation tools have increased provider engagement with patients during consultations while reducing the time spent documenting in electronic health records.

Like many other medical specialties, headache medicine also uses AI. Most prominently, AI has been used in models and engines in assisting with headache diagnoses. A noteworthy example of AI in headache medicine is the development of an online, computer-based diagnostic engine (CDE) by Rapoport et al, called BonTriage. This tool is designed to diagnose headaches by employing a rule set based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3) criteria for primary headache disorders while also evaluating secondary headaches and medication overuse headaches. By leveraging machine learning, the CDE has the potential to streamline the diagnostic process, reducing the number of questions needed to reach a diagnosis and making the experience more efficient. This information can then be printed as a PDF file and taken by the patient to a healthcare professional for further discussion, fostering a more accurate, fluid, and conversational consultation.

A study was conducted to evaluate the accuracy of the CDE. Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 sequences: (1) using the CDE followed by a structured standard interview with a headache specialist using the same ICHD-3 criteria or (2) starting with the structured standard interview followed by the CDE. The results demonstrated nearly perfect agreement in diagnosing migraine and probable migraine between the CDE and structured standard interview (κ = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74, 0.90). The CDE demonstrated a diagnostic accuracy of 91.6% (95% CI: 86.9%, 95.0%), a sensitivity rate of 89.0% (95% CI: 82.5%, 93.7%), and a specificity rate of 97.0% (95% CI: 89.5%, 99.6%).

A diagnostic engine such as this can save time that clinicians spend on documentation and allow more time for discussion with the patient. For instance, a patient can take the printout received from the CDE to an appointment; the printout gives a detailed history plus information about social and psychological issues, a list of medications taken, and results of previous testing. The CDE system was originally designed to help patients see a specialist in the environment of a nationwide lack of headache specialists. There are currently 45 million patients with headaches who are seeking treatment with only around 550 certified headache specialists in the United States. The CDE printed information can help a patient obtain a consultation from a clinician quickly and start evaluation and treatment earlier. This expert online consultation is currently free of charge.

Kwon et al developed a machine learning–based model designed to automatically classify headache disorders using data from a questionnaire. Their model was able to predict diagnoses for conditions such as migraine, tension-type headaches, trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia, epicranial headache, and thunderclap headaches. The model was trained on data from 2162 patients, all diagnosed by headache specialists, and achieved an overall accuracy of 81%, with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 95% for diagnosing migraines. However, the model’s performance was less robust when applied to other headache disorders.

Katsuki et al developed an AI model to help non specialists accurately diagnose headaches. This model analyzed 17 variables and was trained on data from 2800 patients, with additional testing and refinement using data from another 200 patients. To evaluate its effectiveness, 2 groups of non-headache specialists each assessed 50 patients: 1 group relied solely on their expertise, while the other used the AI model. The group without AI assistance achieved an overall accuracy of 46% (κ = 0.21), while the group using the AI model significantly improved, reaching an overall accuracy of 83.2% (κ = 0.68).

Building on their work with AI for diagnosing headaches, Katsuki et al conducted a study using a smartphone application that tracked user-reported headache events alongside local weather data. The AI model revealed that lower barometric pressure, higher humidity, and increased rainfall were linked to the onset of headache attacks. The application also identified triggers for headaches in specific weather patterns, such as a drop in barometric pressure noted 6 hours before headache onset. The application of AI in monitoring weather changes could be crucial, especially given concerns that the rising frequency of severe weather events due to climate change may be exacerbating the severity and burden of migraine. Additionally, recent post hoc analyses of fremanezumab clinical trials have provided further evidence that weather changes can trigger headaches.

Rapoport and colleagues have also developed an application called Migraine Mentor, which accurately tracks headaches, triggers, health data, and response to medication on a smartphone. The patient spends 3 minutes a day answering a few questions about their day and whether they had a headache or took any medication. At 1 or 2 months, Migraine Mentor can generate a detailed report with data and current trends that is sent to the patient, which the patient can then share with the clinician. The application also reminds patients when to document data and take medication.

However, although the use of AI in headache medicine appears promising, caution must be exercised to ensure proper results and information are disseminated. One rapidly expanding application of AI is the widely popular ChatGPT. ChatGPT, which stands for generative pretraining transformer, is a type of large language model (LLM). An LLM is a deep learning algorithm designed to recognize, translate, predict, summarize, and generate text responses based on a given prompt. This model is trained on an extensive dataset that includes a diverse array of books, articles, and websites, exposing it to various language structures and styles. This training enables ChatGPT to generate responses that closely mimic human communication. LLMs are being used more and more in medicine to assist with generating patient documentation and educational materials.

However, Dr Fred Cohen published a perspective piece detailing how LLMs (such as ChatGPT) can produce misleading and inaccurate answers. In his example, he tasked ChatGPT to describe the epidemiology of migraines in penguins; the AI model generated a well-written and highly believable manuscript titled, “Migraine Under the Ice: Understanding Headaches in Antarctica's Feathered Friends.” The manuscript highlights that migraines are more prevalent in male penguins compared to females, with the peak age of onset occurring between 4 and 5 years. Additionally, emperor and king penguins are identified as being more susceptible to developing migraines compared to other penguin species. The paper was fictitious (as no studies on migraine in penguins have been written to date), exemplifying that these models can produce nonfactual materials.

For years, technological advancements have been reshaping many aspects of life, and medicine is no exception. AI has been successfully applied to streamline medical documentation, develop new drug targets, and deepen our understanding of various diseases. The field of headache medicine now also uses AI. Recent developments show significant promise, with AI aiding in the diagnosis of migraine and other headache disorders. AI models have even been used in the identification of potential drug targets for migraine treatment. Although there are still limitations to overcome, the future of AI in headache medicine appears bright.

If you would like to read more about Dr. Cohen’s work on AI and migraine, please visit fredcohenmd.com or TikTok @fredcohenmd.

As we move further into the 21st century, technology continues to revolutionize various facets of our lives. Healthcare is a prime example. Advances in technology have dramatically reshaped the way we develop medications, diagnose diseases, and enhance patient care. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and the widespread adoption of digital health technologies have marked a significant milestone in improving the quality of care. AI, with its ability to leverage algorithms, deep learning, and machine learning to process data, make decisions, and perform tasks autonomously, is becoming an integral part of modern society. It is embedded in various technologies that we rely on daily, from smartphones and smart home devices to content recommendations on streaming services and social media platforms.

In healthcare, AI has applications in numerous fields, such as radiology. AI streamlines processes such as organizing patient appointments, optimizing radiation protocols for safety and efficiency, and enhancing the documentation process through advanced image analysis. AI technology plays an integral role in imaging tasks like image enhancement, lesion detection, and precise measurement. In difficult-to-interpret radiologic studies, such as some mammography images, it can be a crucial aid to the radiologist. Additionally, the use of AI has significantly improved remote patient monitoring that enables healthcare professionals to monitor and assess patient conditions without needing in-person visits. Remote patient monitoring gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to be a valuable tool in post pandemic care. Study results have highlighted that AI-driven ambient dictation tools have increased provider engagement with patients during consultations while reducing the time spent documenting in electronic health records.

Like many other medical specialties, headache medicine also uses AI. Most prominently, AI has been used in models and engines in assisting with headache diagnoses. A noteworthy example of AI in headache medicine is the development of an online, computer-based diagnostic engine (CDE) by Rapoport et al, called BonTriage. This tool is designed to diagnose headaches by employing a rule set based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3) criteria for primary headache disorders while also evaluating secondary headaches and medication overuse headaches. By leveraging machine learning, the CDE has the potential to streamline the diagnostic process, reducing the number of questions needed to reach a diagnosis and making the experience more efficient. This information can then be printed as a PDF file and taken by the patient to a healthcare professional for further discussion, fostering a more accurate, fluid, and conversational consultation.

A study was conducted to evaluate the accuracy of the CDE. Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 sequences: (1) using the CDE followed by a structured standard interview with a headache specialist using the same ICHD-3 criteria or (2) starting with the structured standard interview followed by the CDE. The results demonstrated nearly perfect agreement in diagnosing migraine and probable migraine between the CDE and structured standard interview (κ = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74, 0.90). The CDE demonstrated a diagnostic accuracy of 91.6% (95% CI: 86.9%, 95.0%), a sensitivity rate of 89.0% (95% CI: 82.5%, 93.7%), and a specificity rate of 97.0% (95% CI: 89.5%, 99.6%).

A diagnostic engine such as this can save time that clinicians spend on documentation and allow more time for discussion with the patient. For instance, a patient can take the printout received from the CDE to an appointment; the printout gives a detailed history plus information about social and psychological issues, a list of medications taken, and results of previous testing. The CDE system was originally designed to help patients see a specialist in the environment of a nationwide lack of headache specialists. There are currently 45 million patients with headaches who are seeking treatment with only around 550 certified headache specialists in the United States. The CDE printed information can help a patient obtain a consultation from a clinician quickly and start evaluation and treatment earlier. This expert online consultation is currently free of charge.

Kwon et al developed a machine learning–based model designed to automatically classify headache disorders using data from a questionnaire. Their model was able to predict diagnoses for conditions such as migraine, tension-type headaches, trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia, epicranial headache, and thunderclap headaches. The model was trained on data from 2162 patients, all diagnosed by headache specialists, and achieved an overall accuracy of 81%, with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 95% for diagnosing migraines. However, the model’s performance was less robust when applied to other headache disorders.

Katsuki et al developed an AI model to help non specialists accurately diagnose headaches. This model analyzed 17 variables and was trained on data from 2800 patients, with additional testing and refinement using data from another 200 patients. To evaluate its effectiveness, 2 groups of non-headache specialists each assessed 50 patients: 1 group relied solely on their expertise, while the other used the AI model. The group without AI assistance achieved an overall accuracy of 46% (κ = 0.21), while the group using the AI model significantly improved, reaching an overall accuracy of 83.2% (κ = 0.68).

Building on their work with AI for diagnosing headaches, Katsuki et al conducted a study using a smartphone application that tracked user-reported headache events alongside local weather data. The AI model revealed that lower barometric pressure, higher humidity, and increased rainfall were linked to the onset of headache attacks. The application also identified triggers for headaches in specific weather patterns, such as a drop in barometric pressure noted 6 hours before headache onset. The application of AI in monitoring weather changes could be crucial, especially given concerns that the rising frequency of severe weather events due to climate change may be exacerbating the severity and burden of migraine. Additionally, recent post hoc analyses of fremanezumab clinical trials have provided further evidence that weather changes can trigger headaches.

Rapoport and colleagues have also developed an application called Migraine Mentor, which accurately tracks headaches, triggers, health data, and response to medication on a smartphone. The patient spends 3 minutes a day answering a few questions about their day and whether they had a headache or took any medication. At 1 or 2 months, Migraine Mentor can generate a detailed report with data and current trends that is sent to the patient, which the patient can then share with the clinician. The application also reminds patients when to document data and take medication.

However, although the use of AI in headache medicine appears promising, caution must be exercised to ensure proper results and information are disseminated. One rapidly expanding application of AI is the widely popular ChatGPT. ChatGPT, which stands for generative pretraining transformer, is a type of large language model (LLM). An LLM is a deep learning algorithm designed to recognize, translate, predict, summarize, and generate text responses based on a given prompt. This model is trained on an extensive dataset that includes a diverse array of books, articles, and websites, exposing it to various language structures and styles. This training enables ChatGPT to generate responses that closely mimic human communication. LLMs are being used more and more in medicine to assist with generating patient documentation and educational materials.

However, Dr Fred Cohen published a perspective piece detailing how LLMs (such as ChatGPT) can produce misleading and inaccurate answers. In his example, he tasked ChatGPT to describe the epidemiology of migraines in penguins; the AI model generated a well-written and highly believable manuscript titled, “Migraine Under the Ice: Understanding Headaches in Antarctica's Feathered Friends.” The manuscript highlights that migraines are more prevalent in male penguins compared to females, with the peak age of onset occurring between 4 and 5 years. Additionally, emperor and king penguins are identified as being more susceptible to developing migraines compared to other penguin species. The paper was fictitious (as no studies on migraine in penguins have been written to date), exemplifying that these models can produce nonfactual materials.

For years, technological advancements have been reshaping many aspects of life, and medicine is no exception. AI has been successfully applied to streamline medical documentation, develop new drug targets, and deepen our understanding of various diseases. The field of headache medicine now also uses AI. Recent developments show significant promise, with AI aiding in the diagnosis of migraine and other headache disorders. AI models have even been used in the identification of potential drug targets for migraine treatment. Although there are still limitations to overcome, the future of AI in headache medicine appears bright.

If you would like to read more about Dr. Cohen’s work on AI and migraine, please visit fredcohenmd.com or TikTok @fredcohenmd.

As we move further into the 21st century, technology continues to revolutionize various facets of our lives. Healthcare is a prime example. Advances in technology have dramatically reshaped the way we develop medications, diagnose diseases, and enhance patient care. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and the widespread adoption of digital health technologies have marked a significant milestone in improving the quality of care. AI, with its ability to leverage algorithms, deep learning, and machine learning to process data, make decisions, and perform tasks autonomously, is becoming an integral part of modern society. It is embedded in various technologies that we rely on daily, from smartphones and smart home devices to content recommendations on streaming services and social media platforms.

In healthcare, AI has applications in numerous fields, such as radiology. AI streamlines processes such as organizing patient appointments, optimizing radiation protocols for safety and efficiency, and enhancing the documentation process through advanced image analysis. AI technology plays an integral role in imaging tasks like image enhancement, lesion detection, and precise measurement. In difficult-to-interpret radiologic studies, such as some mammography images, it can be a crucial aid to the radiologist. Additionally, the use of AI has significantly improved remote patient monitoring that enables healthcare professionals to monitor and assess patient conditions without needing in-person visits. Remote patient monitoring gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to be a valuable tool in post pandemic care. Study results have highlighted that AI-driven ambient dictation tools have increased provider engagement with patients during consultations while reducing the time spent documenting in electronic health records.

Like many other medical specialties, headache medicine also uses AI. Most prominently, AI has been used in models and engines in assisting with headache diagnoses. A noteworthy example of AI in headache medicine is the development of an online, computer-based diagnostic engine (CDE) by Rapoport et al, called BonTriage. This tool is designed to diagnose headaches by employing a rule set based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3) criteria for primary headache disorders while also evaluating secondary headaches and medication overuse headaches. By leveraging machine learning, the CDE has the potential to streamline the diagnostic process, reducing the number of questions needed to reach a diagnosis and making the experience more efficient. This information can then be printed as a PDF file and taken by the patient to a healthcare professional for further discussion, fostering a more accurate, fluid, and conversational consultation.

A study was conducted to evaluate the accuracy of the CDE. Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 sequences: (1) using the CDE followed by a structured standard interview with a headache specialist using the same ICHD-3 criteria or (2) starting with the structured standard interview followed by the CDE. The results demonstrated nearly perfect agreement in diagnosing migraine and probable migraine between the CDE and structured standard interview (κ = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74, 0.90). The CDE demonstrated a diagnostic accuracy of 91.6% (95% CI: 86.9%, 95.0%), a sensitivity rate of 89.0% (95% CI: 82.5%, 93.7%), and a specificity rate of 97.0% (95% CI: 89.5%, 99.6%).

A diagnostic engine such as this can save time that clinicians spend on documentation and allow more time for discussion with the patient. For instance, a patient can take the printout received from the CDE to an appointment; the printout gives a detailed history plus information about social and psychological issues, a list of medications taken, and results of previous testing. The CDE system was originally designed to help patients see a specialist in the environment of a nationwide lack of headache specialists. There are currently 45 million patients with headaches who are seeking treatment with only around 550 certified headache specialists in the United States. The CDE printed information can help a patient obtain a consultation from a clinician quickly and start evaluation and treatment earlier. This expert online consultation is currently free of charge.

Kwon et al developed a machine learning–based model designed to automatically classify headache disorders using data from a questionnaire. Their model was able to predict diagnoses for conditions such as migraine, tension-type headaches, trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia, epicranial headache, and thunderclap headaches. The model was trained on data from 2162 patients, all diagnosed by headache specialists, and achieved an overall accuracy of 81%, with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 95% for diagnosing migraines. However, the model’s performance was less robust when applied to other headache disorders.

Katsuki et al developed an AI model to help non specialists accurately diagnose headaches. This model analyzed 17 variables and was trained on data from 2800 patients, with additional testing and refinement using data from another 200 patients. To evaluate its effectiveness, 2 groups of non-headache specialists each assessed 50 patients: 1 group relied solely on their expertise, while the other used the AI model. The group without AI assistance achieved an overall accuracy of 46% (κ = 0.21), while the group using the AI model significantly improved, reaching an overall accuracy of 83.2% (κ = 0.68).

Building on their work with AI for diagnosing headaches, Katsuki et al conducted a study using a smartphone application that tracked user-reported headache events alongside local weather data. The AI model revealed that lower barometric pressure, higher humidity, and increased rainfall were linked to the onset of headache attacks. The application also identified triggers for headaches in specific weather patterns, such as a drop in barometric pressure noted 6 hours before headache onset. The application of AI in monitoring weather changes could be crucial, especially given concerns that the rising frequency of severe weather events due to climate change may be exacerbating the severity and burden of migraine. Additionally, recent post hoc analyses of fremanezumab clinical trials have provided further evidence that weather changes can trigger headaches.

Rapoport and colleagues have also developed an application called Migraine Mentor, which accurately tracks headaches, triggers, health data, and response to medication on a smartphone. The patient spends 3 minutes a day answering a few questions about their day and whether they had a headache or took any medication. At 1 or 2 months, Migraine Mentor can generate a detailed report with data and current trends that is sent to the patient, which the patient can then share with the clinician. The application also reminds patients when to document data and take medication.

However, although the use of AI in headache medicine appears promising, caution must be exercised to ensure proper results and information are disseminated. One rapidly expanding application of AI is the widely popular ChatGPT. ChatGPT, which stands for generative pretraining transformer, is a type of large language model (LLM). An LLM is a deep learning algorithm designed to recognize, translate, predict, summarize, and generate text responses based on a given prompt. This model is trained on an extensive dataset that includes a diverse array of books, articles, and websites, exposing it to various language structures and styles. This training enables ChatGPT to generate responses that closely mimic human communication. LLMs are being used more and more in medicine to assist with generating patient documentation and educational materials.

However, Dr Fred Cohen published a perspective piece detailing how LLMs (such as ChatGPT) can produce misleading and inaccurate answers. In his example, he tasked ChatGPT to describe the epidemiology of migraines in penguins; the AI model generated a well-written and highly believable manuscript titled, “Migraine Under the Ice: Understanding Headaches in Antarctica's Feathered Friends.” The manuscript highlights that migraines are more prevalent in male penguins compared to females, with the peak age of onset occurring between 4 and 5 years. Additionally, emperor and king penguins are identified as being more susceptible to developing migraines compared to other penguin species. The paper was fictitious (as no studies on migraine in penguins have been written to date), exemplifying that these models can produce nonfactual materials.

For years, technological advancements have been reshaping many aspects of life, and medicine is no exception. AI has been successfully applied to streamline medical documentation, develop new drug targets, and deepen our understanding of various diseases. The field of headache medicine now also uses AI. Recent developments show significant promise, with AI aiding in the diagnosis of migraine and other headache disorders. AI models have even been used in the identification of potential drug targets for migraine treatment. Although there are still limitations to overcome, the future of AI in headache medicine appears bright.

If you would like to read more about Dr. Cohen’s work on AI and migraine, please visit fredcohenmd.com or TikTok @fredcohenmd.

A Clonal Complete Remission Induced by IDH1 Inhibitor Ivosidenib in a Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) With Co-Mutations of IDH1 and the ZRSR2 RNA Splicing Gene

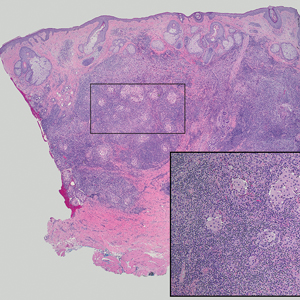

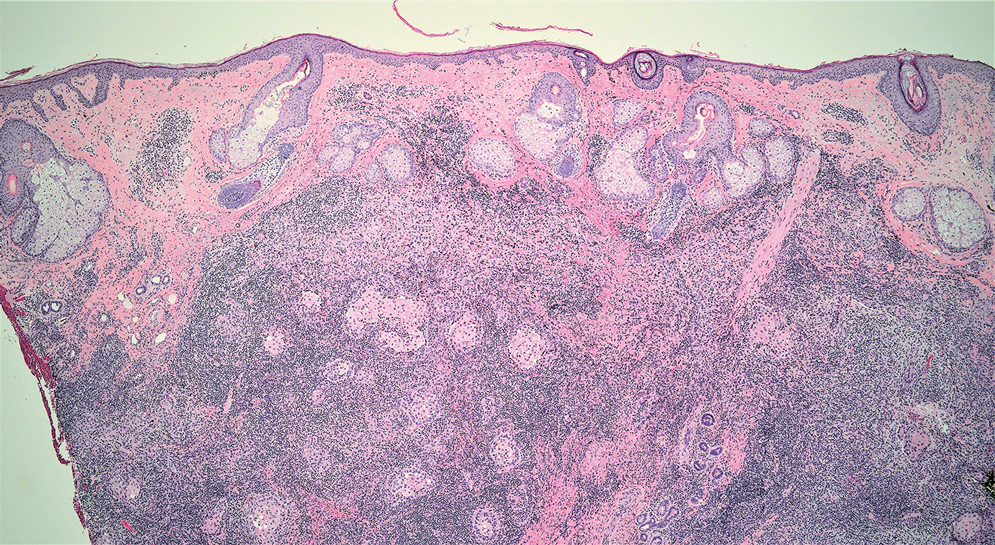

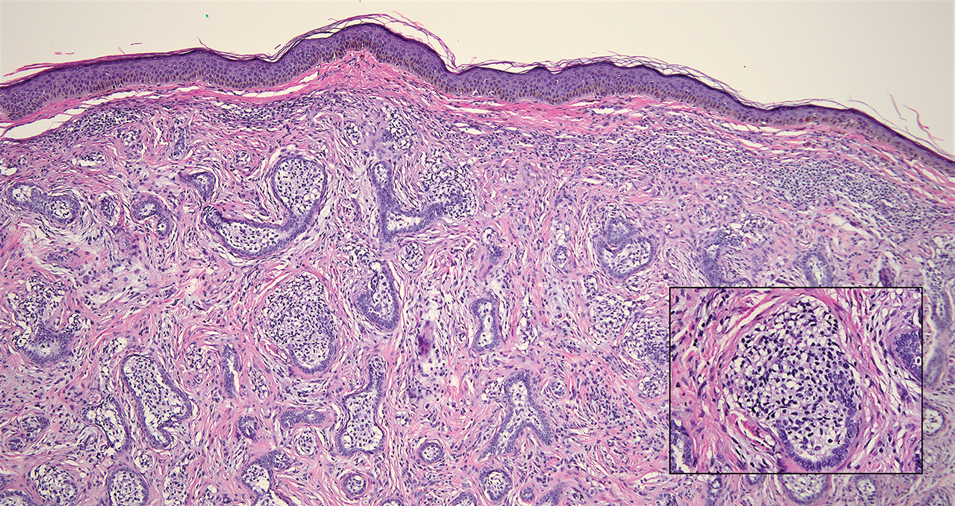

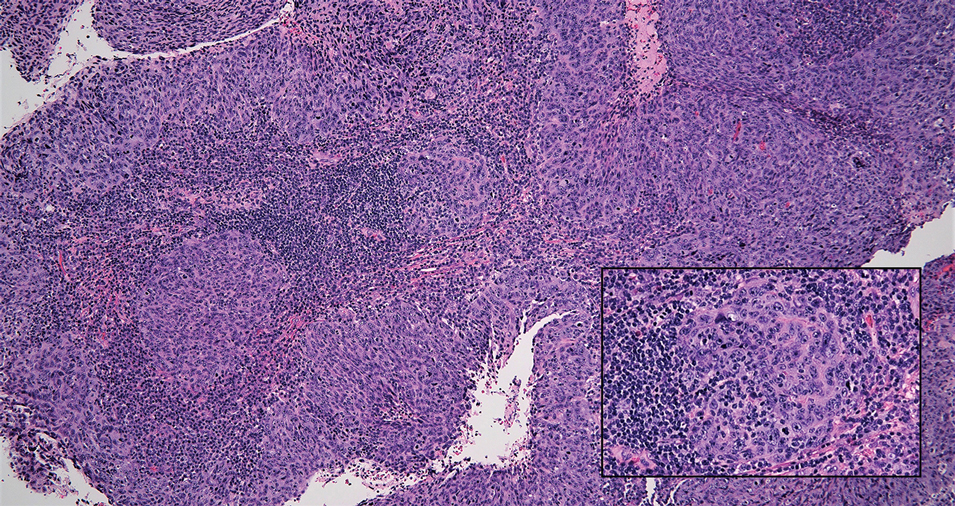

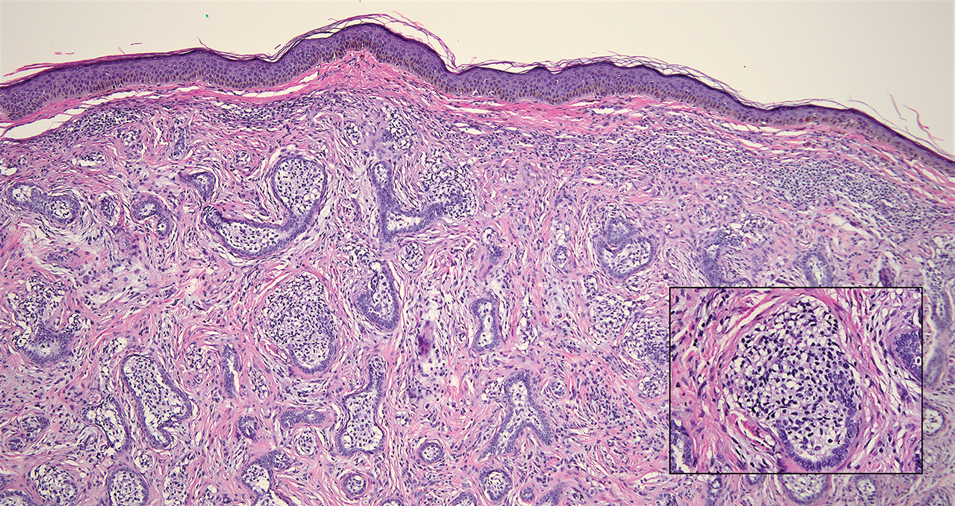

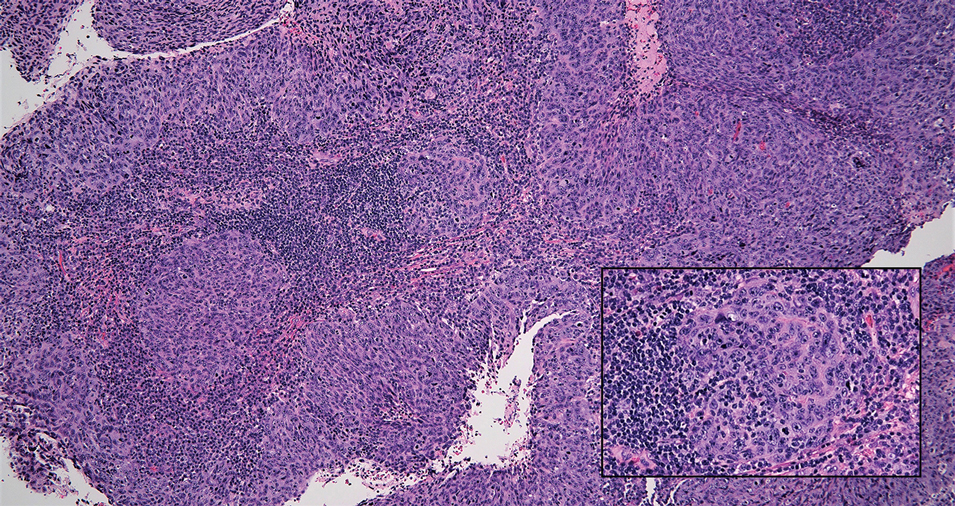

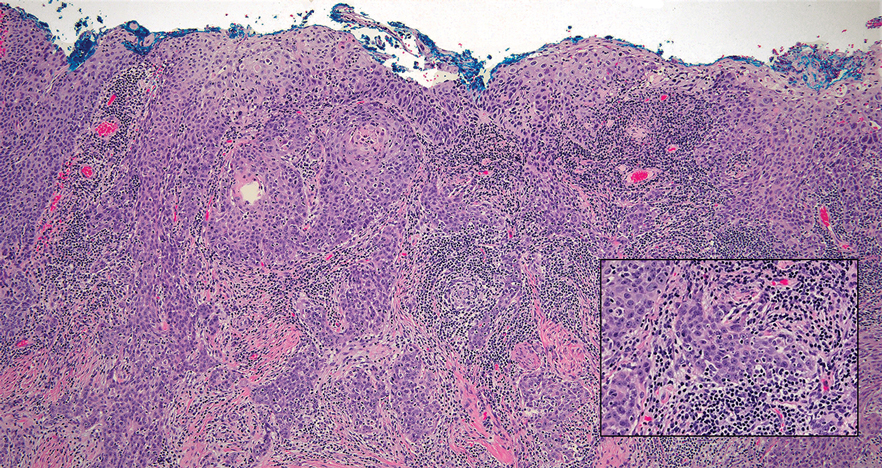

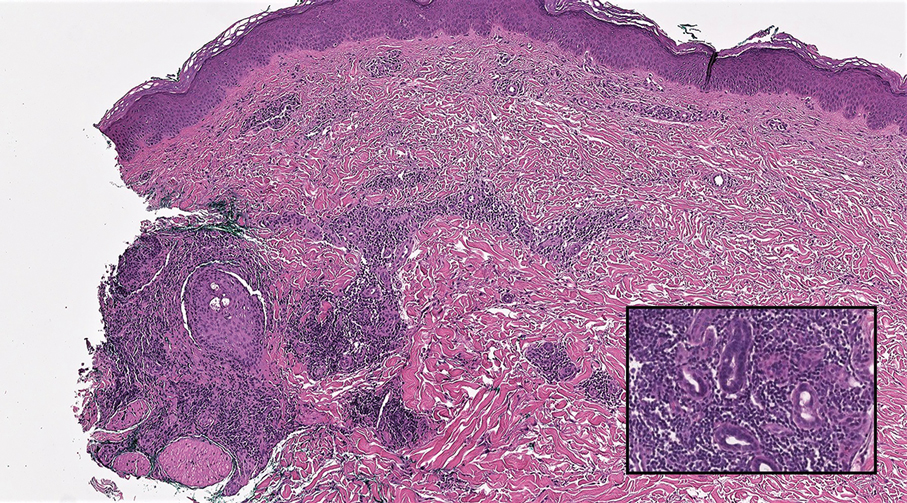

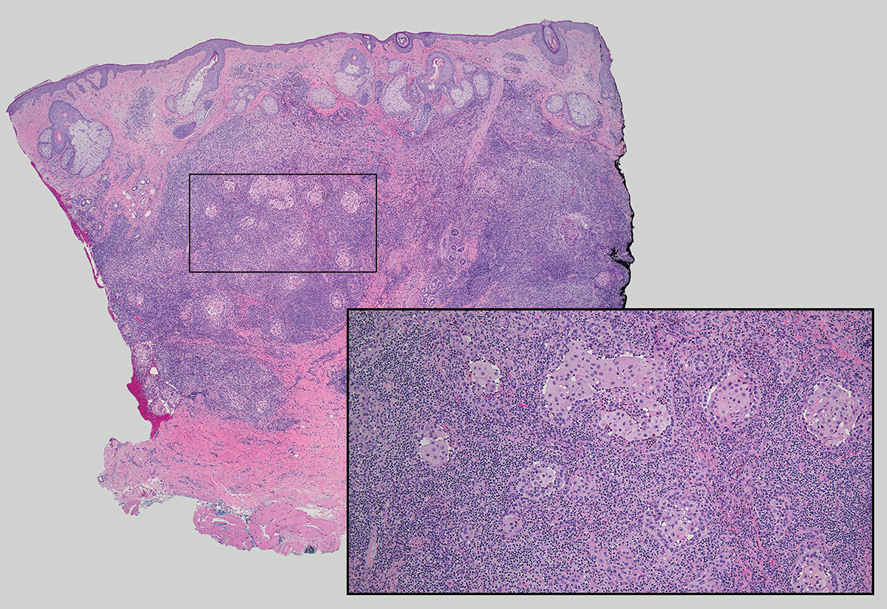

Background

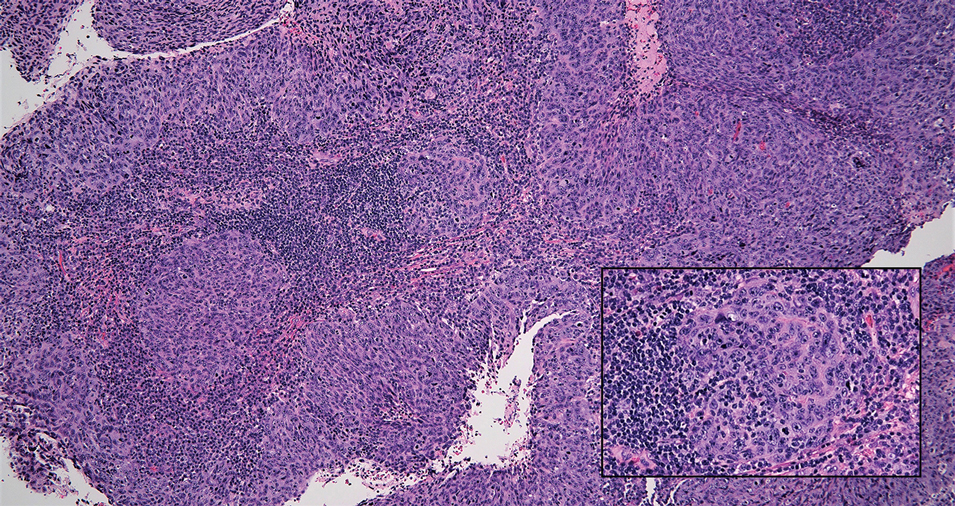

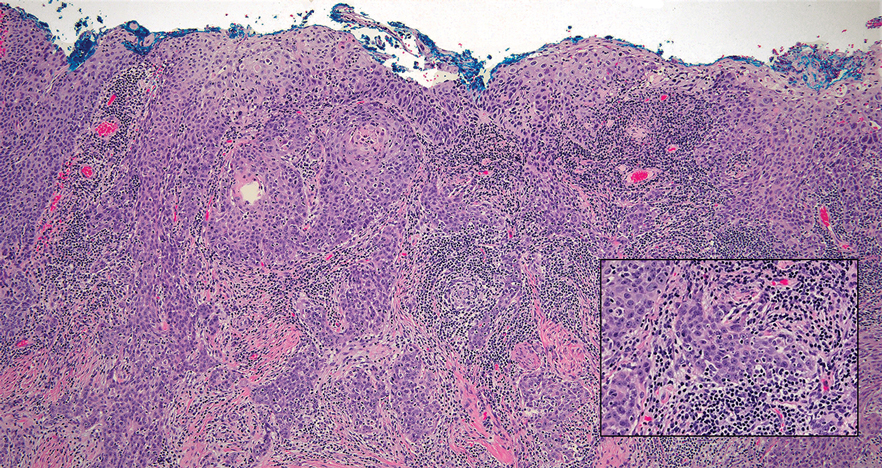

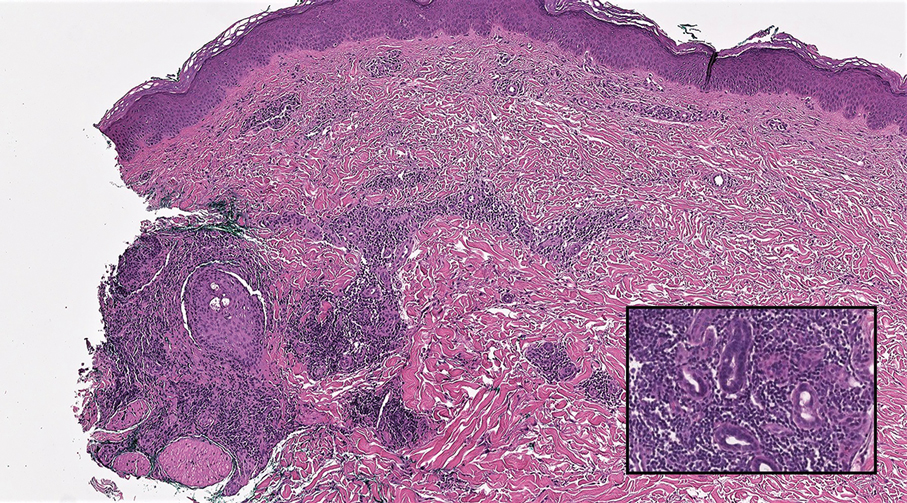

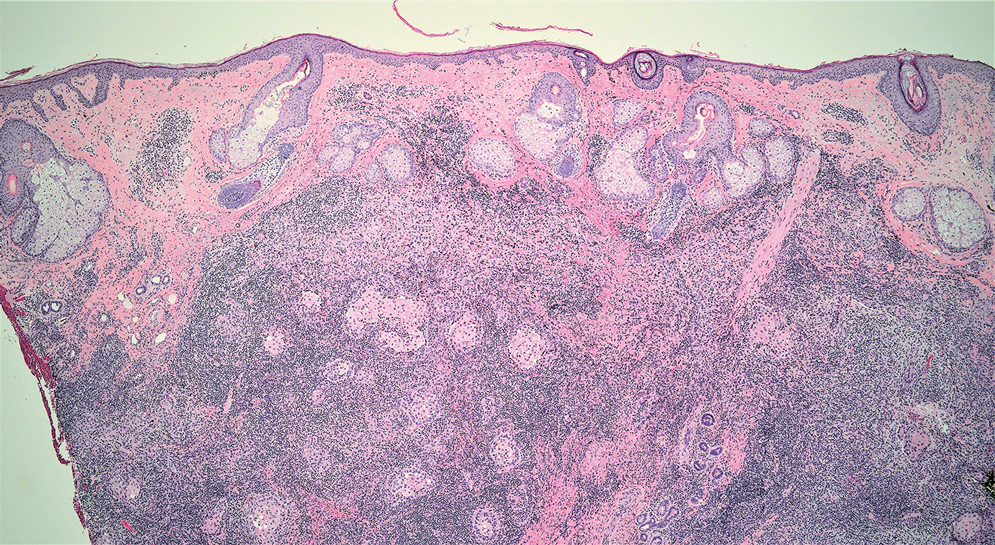

IDH1 mutations are detected in 3-4% of MDS, nearly always with one or more co-mutations. Treatment with IDH1 inhibitor ivosidenib typically resulted in regression of the abnormal clone in 15 reported responders. However, in a few cases differentiation was restored from the abnormal clone. Here we report a durable MDS remission despite sustained proliferation of a clone with IDH1 and ZRSR2 mutations.

Case Presentation

A 49-year-old man developed severe neutropenia and macrocytic anemia in January 2019. Mild marrow dysplasia developed by March 2020 with IDH1 (31.1%) and splicing gene ZRSR2 (55.7%) mutations. In October 2022 biopsy showed MDS with 4% blasts, megakaryocytic/granulocytic hypoplasia, normal cytogenetics and 43% IDH1/89% ZRSR2. After azacytidine failure, ivosidenib was started in November 2023 following FDA approval. Within weeks ANCs increased from 170 to 1580 and hemoglobin from 7.9 to 11.6 with MCV 115, reticulocytes 1.72%. At 3 months a CBC was normal except for MCV 111. IDH1 and ZRSR2 were 36.4% and 71%. After 6 months, ANC was 2380, hemoglobin 14.7, MCV 108.6, reticulo-cytes 1.77%. IDH1 PCR showed a 33.1% allele frequency consistent with a clonal remission.

Discussion

IDH1 mutations in MDS/AML frequently co-occur with mutations in RNA splicing genes SRSF2 or ZRSR2. For ZRSR2, we previously reported that isolated mutations of this gene cause refractory macrocytic anemias without dysplasia, thus presenting as clonal cytopenias of undetermined significance (Fleischman et al., Leuk Res, 2017). In this MDS case, after ivosidenib treatment the ZRSR2 splicing defect sustained clonal dominance over polyclonal hematopoiesis while accounting for macrocytosis. Longitudinal data for two ivosidenib-treated IDH1/SRSF2 MDS cases are incomplete, but one case of IDH2/SRSF2 MDS treated with the inhibitor enasidenib similarly achieved complete remission without regression of the mutated clone for 12 months.

Conclusions

Following the FDA approval of ivosidenib, all cases of MDS should have DNA sequencing performed at diagnosis to identify IDH1 mutations. Treatment induces high rates of remission even when polyclonal hematopoiesis does not recover. Moreover, the restoration of hematopoietic differentiation by the abnormal clone provides unique insights into the clinical phenotype and fitness advantage conferred by the co-existing driver mutations.

Background

IDH1 mutations are detected in 3-4% of MDS, nearly always with one or more co-mutations. Treatment with IDH1 inhibitor ivosidenib typically resulted in regression of the abnormal clone in 15 reported responders. However, in a few cases differentiation was restored from the abnormal clone. Here we report a durable MDS remission despite sustained proliferation of a clone with IDH1 and ZRSR2 mutations.

Case Presentation

A 49-year-old man developed severe neutropenia and macrocytic anemia in January 2019. Mild marrow dysplasia developed by March 2020 with IDH1 (31.1%) and splicing gene ZRSR2 (55.7%) mutations. In October 2022 biopsy showed MDS with 4% blasts, megakaryocytic/granulocytic hypoplasia, normal cytogenetics and 43% IDH1/89% ZRSR2. After azacytidine failure, ivosidenib was started in November 2023 following FDA approval. Within weeks ANCs increased from 170 to 1580 and hemoglobin from 7.9 to 11.6 with MCV 115, reticulocytes 1.72%. At 3 months a CBC was normal except for MCV 111. IDH1 and ZRSR2 were 36.4% and 71%. After 6 months, ANC was 2380, hemoglobin 14.7, MCV 108.6, reticulo-cytes 1.77%. IDH1 PCR showed a 33.1% allele frequency consistent with a clonal remission.

Discussion

IDH1 mutations in MDS/AML frequently co-occur with mutations in RNA splicing genes SRSF2 or ZRSR2. For ZRSR2, we previously reported that isolated mutations of this gene cause refractory macrocytic anemias without dysplasia, thus presenting as clonal cytopenias of undetermined significance (Fleischman et al., Leuk Res, 2017). In this MDS case, after ivosidenib treatment the ZRSR2 splicing defect sustained clonal dominance over polyclonal hematopoiesis while accounting for macrocytosis. Longitudinal data for two ivosidenib-treated IDH1/SRSF2 MDS cases are incomplete, but one case of IDH2/SRSF2 MDS treated with the inhibitor enasidenib similarly achieved complete remission without regression of the mutated clone for 12 months.

Conclusions

Following the FDA approval of ivosidenib, all cases of MDS should have DNA sequencing performed at diagnosis to identify IDH1 mutations. Treatment induces high rates of remission even when polyclonal hematopoiesis does not recover. Moreover, the restoration of hematopoietic differentiation by the abnormal clone provides unique insights into the clinical phenotype and fitness advantage conferred by the co-existing driver mutations.

Background

IDH1 mutations are detected in 3-4% of MDS, nearly always with one or more co-mutations. Treatment with IDH1 inhibitor ivosidenib typically resulted in regression of the abnormal clone in 15 reported responders. However, in a few cases differentiation was restored from the abnormal clone. Here we report a durable MDS remission despite sustained proliferation of a clone with IDH1 and ZRSR2 mutations.

Case Presentation

A 49-year-old man developed severe neutropenia and macrocytic anemia in January 2019. Mild marrow dysplasia developed by March 2020 with IDH1 (31.1%) and splicing gene ZRSR2 (55.7%) mutations. In October 2022 biopsy showed MDS with 4% blasts, megakaryocytic/granulocytic hypoplasia, normal cytogenetics and 43% IDH1/89% ZRSR2. After azacytidine failure, ivosidenib was started in November 2023 following FDA approval. Within weeks ANCs increased from 170 to 1580 and hemoglobin from 7.9 to 11.6 with MCV 115, reticulocytes 1.72%. At 3 months a CBC was normal except for MCV 111. IDH1 and ZRSR2 were 36.4% and 71%. After 6 months, ANC was 2380, hemoglobin 14.7, MCV 108.6, reticulo-cytes 1.77%. IDH1 PCR showed a 33.1% allele frequency consistent with a clonal remission.

Discussion

IDH1 mutations in MDS/AML frequently co-occur with mutations in RNA splicing genes SRSF2 or ZRSR2. For ZRSR2, we previously reported that isolated mutations of this gene cause refractory macrocytic anemias without dysplasia, thus presenting as clonal cytopenias of undetermined significance (Fleischman et al., Leuk Res, 2017). In this MDS case, after ivosidenib treatment the ZRSR2 splicing defect sustained clonal dominance over polyclonal hematopoiesis while accounting for macrocytosis. Longitudinal data for two ivosidenib-treated IDH1/SRSF2 MDS cases are incomplete, but one case of IDH2/SRSF2 MDS treated with the inhibitor enasidenib similarly achieved complete remission without regression of the mutated clone for 12 months.

Conclusions

Following the FDA approval of ivosidenib, all cases of MDS should have DNA sequencing performed at diagnosis to identify IDH1 mutations. Treatment induces high rates of remission even when polyclonal hematopoiesis does not recover. Moreover, the restoration of hematopoietic differentiation by the abnormal clone provides unique insights into the clinical phenotype and fitness advantage conferred by the co-existing driver mutations.

Creating a Urology Prostate Cancer Note, a National Oncology and Surgery Office Collaboration for Prostate Cancer Clinical Pathway Utilization

Background

Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous malignancy diagnosis within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The Prostate Cancer Clinical Pathways (PCCP) were developed to enable providers to treat all Veterans with prostate cancer at subject matter expert level.

Discussion

The PCCP was launched in February 2021; however, provider documentation of PCCP is variable across the VA healthcare system and within the PCCP, specific flow maps have differential use. For example, the Very Low Risk flow map has seven unique Veterans entered, whereas the Molecular Testing flow map has over 3,900 unique Veterans entered. One clear reason for this disparity in pathway documentation use is that local prostate cancer is managed by urology and their documentation of the PCCP is not as widespread as the medical oncologists. The National Oncology Program developed clinical note templates to document PCCP that medical oncologist use which has increased utilization. To increase urology specific flow map use, a collaboration between the National Surgery Office and National Oncology Program was established to develop a Urology Prostate Cancer Note (UPCN). The UPCN was designed by urologists with assistance from a medical oncologist and a clinical applications coordinator. The UPCN will function as a working clinical note for urologists and has the PCCPs embedded into reminder dialog templates, which when completed generate health factors. The health factors that are generated from the UPCN are data mined to record PCCP use and to perform data analytics. The UPCN is in the testing phase at three pilot test sites and is scheduled to be deployed summer 2024. The collaborative effort is aligned with the VHA directives outlined in the Cleland Dole Act.

Background

Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous malignancy diagnosis within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The Prostate Cancer Clinical Pathways (PCCP) were developed to enable providers to treat all Veterans with prostate cancer at subject matter expert level.

Discussion

The PCCP was launched in February 2021; however, provider documentation of PCCP is variable across the VA healthcare system and within the PCCP, specific flow maps have differential use. For example, the Very Low Risk flow map has seven unique Veterans entered, whereas the Molecular Testing flow map has over 3,900 unique Veterans entered. One clear reason for this disparity in pathway documentation use is that local prostate cancer is managed by urology and their documentation of the PCCP is not as widespread as the medical oncologists. The National Oncology Program developed clinical note templates to document PCCP that medical oncologist use which has increased utilization. To increase urology specific flow map use, a collaboration between the National Surgery Office and National Oncology Program was established to develop a Urology Prostate Cancer Note (UPCN). The UPCN was designed by urologists with assistance from a medical oncologist and a clinical applications coordinator. The UPCN will function as a working clinical note for urologists and has the PCCPs embedded into reminder dialog templates, which when completed generate health factors. The health factors that are generated from the UPCN are data mined to record PCCP use and to perform data analytics. The UPCN is in the testing phase at three pilot test sites and is scheduled to be deployed summer 2024. The collaborative effort is aligned with the VHA directives outlined in the Cleland Dole Act.

Background

Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous malignancy diagnosis within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The Prostate Cancer Clinical Pathways (PCCP) were developed to enable providers to treat all Veterans with prostate cancer at subject matter expert level.

Discussion

The PCCP was launched in February 2021; however, provider documentation of PCCP is variable across the VA healthcare system and within the PCCP, specific flow maps have differential use. For example, the Very Low Risk flow map has seven unique Veterans entered, whereas the Molecular Testing flow map has over 3,900 unique Veterans entered. One clear reason for this disparity in pathway documentation use is that local prostate cancer is managed by urology and their documentation of the PCCP is not as widespread as the medical oncologists. The National Oncology Program developed clinical note templates to document PCCP that medical oncologist use which has increased utilization. To increase urology specific flow map use, a collaboration between the National Surgery Office and National Oncology Program was established to develop a Urology Prostate Cancer Note (UPCN). The UPCN was designed by urologists with assistance from a medical oncologist and a clinical applications coordinator. The UPCN will function as a working clinical note for urologists and has the PCCPs embedded into reminder dialog templates, which when completed generate health factors. The health factors that are generated from the UPCN are data mined to record PCCP use and to perform data analytics. The UPCN is in the testing phase at three pilot test sites and is scheduled to be deployed summer 2024. The collaborative effort is aligned with the VHA directives outlined in the Cleland Dole Act.

Migraine Treatment Outcomes

Outcomes of Acute and Preventive Migraine Therapy Based on Patient Sex

I previously have addressed myths about migraine as they pertain to men and women. When I found an interesting study recently published in Cephalalgia investigating the effectiveness of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor (CGRP-R) antagonists (gepants) for acute care and prevention of episodic migraine and CGRP monoclonal antibodies for preventive treatment of episodic and chronic migraine in men and women, I thought I would discuss it here.

The study’s aim was to discern if patient sex contributed to outcomes in each specific treatment arm. Female sex hormones have been recognized as factors in promoting migraine, and women show increased severity, persistence, and comorbidity in migraine profiles, and increased prevalence of migraine relative to men.

Gepants used for acute therapy (ubrogepant, rimegepant, zavegepant) and preventive therapy (atogepant, rimegepant) were studied in this trial. Erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab are monoclonal antibodies that either sit on the CGRP receptor (erenumab) or inactivate the CGRP ligand (fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab) and are used for migraine prevention. CGRP-based therapies are not effective in all patients and understanding which patient groups respond preferentially could reduce trial and error in treatment selection. The effectiveness of treatments targeting CGRP or the CGRP receptor may not be uniform in men and women, highlighting the need for further research and understanding of CGRP neurobiology in both sexes.

Key findings: