User login

Inpatient Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Delphi Consensus Study

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 0.1% of the US population.1,2 Severe disease or HS flares can lead patients to seek care through the emergency department (ED), with some requiring inpatient admission. 3 Inpatient hospitalization of patients with HS has increased over the last 2 decades, and patients with HS utilize emergency and inpatient care more frequently than those with other dermatologic conditions.4,5 Minority patients and those of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to present to the ED for HS management due to limited access to care and other existing comorbid conditions. 4 In a 2022 study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the authors looked at hospital readmission rates of patients with HS compared with those with heart failure—both patient populations with chronic debilitating conditions. Results indicated that the hospital readmission rates for patients with HS surpassed those of patients with heart failure for that year, highlighting the need for improved inpatient management of HS.6

Patients with HS present to the ED with severe pain, fever, wound care, or the need for surgical intervention. The ED and inpatient hospital setting are locations in which physicians may not be as familiar with the diagnosis or treatment of HS, specifically flares or severe disease. 7 The inpatient care setting provides access to certain resources that can be challenging to obtain in the outpatient clinical setting, such as social workers and pain specialists, but also can prove challenging in obtaining other resources for HS management, such as advanced medical therapies. Given the increase in hospital- based care for HS and lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial. In our study, we sought to generate a collection of expert consensus statements providers can refer to when managing patients with HS in the inpatient setting.

Methods

The study team at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(M.N., R.P., L.C.S.) developed an initial set of consensus statements based on current published HS treatment guidelines,8,9 publications on management of inpatient HS,3 published supportive care guidelines for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, 10 and personal clinical experience in managing inpatient HS, which resulted in 50 statements organized into the following categories: overall care, wound care, genital care, pain management, infection control, medical management, surgical management, nutrition, and transitional care guidelines. This study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (IRB00084257).

Participant Recruitment—Dermatologists were identified for participation in the study based on membership in the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation or authorship of publications relevant to HS or inpatient dermatology. Dermatologists from larger academic institutions with HS specialty clinics and inpatient dermatology services also were identified. Participants were invited via email and could suggest other experts for inclusion. A total of 31 dermatologists were invited to participate in the study, with 26 agreeing to participate. All participating dermatologists were practicing in the United States.

Delphi Study—In the first round of the Delphi study, the participants were sent an online survey via REDCap in which they were asked to rank the appropriateness of each of the proposed 50 guideline statements on a scale of 1 (very inappropriate) to 9 (very appropriate). Participants also were able to provide commentary and feedback on each of the statements. Survey results were analyzed using the RAND/ UCLA Appropriateness Method.11 For each statement, the median rating for appropriateness, interpercentile range (IPR), IPR adjusted for symmetry, and disagreement index (DI) were calculated (DI=IPR/IPR adjusted for symmetry). The 30th and 70th percentiles were used in the DI calculation as the upper and lower limits, respectively. A median rating for appropriateness of 1.0 to 3.9 was considered “inappropriate,” 4.0 to 6.9 was considered “uncertain appropriateness,” and 7.0 to 9.0 was “appropriate.” A DI value greater than or equal to 1 indicated a lack of consensus regarding the appropriateness of the statement. Following each round, participants received a copy of their responses along with the group median rank of each statement. Statements that did not reach consensus in the first Delphi round were revised based on feedback received by the participants, and a second survey with 14 statements was sent via REDCap 2 weeks later. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method also was applied to this second Delphi round. After the second survey, participants received a copy of anonymized comments regarding the consensus statements and were allowed to provide additional final commentary to be included in the discussion of these recommendations.

Results

Twenty-six dermatologists completed the first-round survey, and 24 participants completed the second-round survey. All participants self-identified as having expertise in either HS (n=22 [85%]) or inpatient dermatology (n=17 [65%]), and 13 (50%) participants self-identified as experts in both HS and inpatient dermatology. All participants, except 1, were affiliated with an academic health system with inpatient dermatology services. The average length of time in practice as a dermatologist was 10 years (median, 9 years [range, 3–27 years]).

Of the 50 initial proposed consensus statements, 26 (52%) achieved consensus after the first round; 21 statements revealed DI calculations that did not achieve consensus. Two statements achieved consensus but received median ratings for appropriateness, indicating uncertain appropriateness; because of this, 1 statement was removed and 1 was revised based on participant feedback, resulting in 13 revised statements (eTable 1). Controversial topics in the consensus process included obtaining wound cultures and meaningful culture data interpretation, use of specific biologic medications in the inpatient setting, and use of intravenous ertapenem. Participant responses to these topics are discussed in detail below. Of these secondround statements, all achieved consensus. The final set of consensus statements can be found in eTable 2.

Comment

Our Delphi consensus study combined the expertise of both dermatologists who care for patients with HS and those with inpatient dermatology experience to produce a set of recommendations for the management of HS in the hospital care setting. A strength of this study is inclusion of many national leaders in both HS and inpatient dermatology, with some participants having developed the previously published HS treatment guidelines and others having participated in inpatient dermatology Delphi studies.8-10 The expertise is further strengthened by the geographically diverse institutional representation within the United States.

The final consensus recommendations included 40 statements covering a range of patient care issues, including use of appropriate inpatient subspecialists (care team), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition back to outpatient management (transitional care). These recommendations are meant to serve as a resource for providers to consider when taking care of inpatient HS flares, recognizing that the complexity and individual circumstances of each patient are unique.

Delphi Consensus Recommendations Compared to Prior Guidelines—Several recommendations in the current study align with the previously published North American clinical management guidelines for HS.8,9 Our recommendations agree with prior guidelines on the importance of disease staging and pain assessment using validated assessment tools as well as screening for HS comorbidities. There also is agreement in the potential benefit of involving pain specialists in the development of a comprehensive pain management plan. The inpatient care setting provides a unique opportunity to engage multiple specialists and collaborate on patient care in a timely manner. Our recommendations regarding surgical care also align with established guidelines in recommending incision and drainage as an acute bedside procedure best utilized for symptom relief in inflamed abscesses and relegating most other surgical management to the outpatient setting. Wound care recommendations also are similar, with our expert participants agreeing on individualizing dressing choices based on wound characteristics. A benefit of inpatient wound care is access to skilled nursing for dressing changes and potentially improved access to more sophisticated dressing materials. Our recommendations differ from the prior guidelines in our focus on severe HS, HS flares, and HS complications, which constitute the majority of inpatient disease management. We provide additional guidance on management of secondary infections, perianal fistulous disease, and importantly transitional care to optimize discharge planning.

Differing Opinions in Our Analysis—Despite the success of our Delphi consensus process, there were some differing opinions regarding certain aspects of inpatient HS management, which is to be expected given the lack of strong evidence-based research to support some of the recommended practices. There were differing opinions on the utility of wound culture data, with some participants feeling culture data could help with antibiotic susceptibility and resistance patterns, while others felt wound cultures represent bacterial colonization or biofilm formation.

Initial consensus statements in the first Delphi round were created for individual biologic medications but did not achieve consensus, and feedback on the use of biologics in the inpatient environment was mixed, largely due to logistic and insurance issues. Many participants felt biologic medication cost, difficulty obtaining inpatient reimbursement, health care resource utilization, and availability of biologics in different hospital systems prevented recommending the use of specific biologics during hospitalization. The one exception was in the case of a hospitalized patient who was already receiving infliximab for HS: there was consensus on ensuring the patient dosing was maximized, if appropriate, to 10 mg/kg.12 Ertapenem use also was controversial, with some participants using it as a bridge therapy to either outpatient biologic use or surgery, while others felt it was onerous and difficult to establish reliable access to secure intravenous administration and regular dosing once the patient left the inpatient setting.13 Others said they have experienced objections from infectious disease colleagues on the use of intravenous antibiotics, citing antibiotic stewardship concerns.

Patient Care in the Inpatient Setting—Prior literature suggests patients admitted as inpatients for HS tend to be of lower socioeconomic status and are admitted to larger urban teaching hospitals.14,15 Patients with lower socioeconomic status have increased difficulty accessing health care resources; therefore, inpatient admission serves as an opportunity to provide a holistic HS assessment and coordinate resources for chronic outpatient management.

Study Limitations—This Delphi consensus study has some limitations. The existing literature on inpatient management of HS is limited, challenging our ability to assess the extent to which these published recommendations are already being implemented. Additionally, the study included HS and inpatient dermatology experts from the United States, which means the recommendations may not be generalizable to other countries. Most participants practiced dermatology at large tertiary care academic medical centers, which may limit the ability to implement recommendations in all US inpatient care settings such as small community-based hospitals; however, many of the supportive care guidelines such as pain control, wound care, nutritional support, and social work should be achievable in most inpatient care settings.

Conclusion

Given the increase in inpatient and ED health care utilization for HS, there is an urgent need for expert consensus recommendations on inpatient management of this unique patient population, which requires complex multidisciplinary care. Our recommendations are a resource for providers to utilize and potentially improve the standard of care we provide these patients.

Acknowledgment—We thank the Wake Forest University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston- Salem, North Carolina) for providing statistical help.

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:990-998. doi:10.1111/bjd.19435

- Charrow A, Savage KT, Flood K, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa for the dermatologic hospitalist. Cutis. 2019;104:276-280.

- Anzaldi L, Perkins JA, Byrd AS, et al. Characterizing inpatient hospitalizations for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:510-513. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.019

- Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:609-614. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053

- Edigin E, Kaul S, Eseaton PO, et al. At 180 days hidradenitis suppurativa readmission rate is comparable to heart failure: analysis of the nationwide readmissions database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:188-192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.894

- Kirby JS, Miller JJ, Adams DR, et al. Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:937-944. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.691

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2019.02.067

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2020.02.066

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Burnand B, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method: User’s Manual. Rand; 2001.

- Oskardmay AN, Miles JA, Sayed CJ. Determining the optimal dose of infliximab for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:702-708. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.022

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard-Biehler H, Jais JP, et al. Efficacy of ertapenem in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study in a cohort of 30 consecutive patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:513-520. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv361

- Khanna R, Whang KA, Huang AH, et al. Inpatient burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: analysis of the 2016 National Inpatient Sample. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1150-1152. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2020.1773380

- Patel A, Patel A, Solanki D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: insights from the national inpatient sample (2008-2017) on contemporary trends in demographics, hospitalization rates, chronic comorbid conditions, and mortality. Cureus. 2022;14:E24755. doi:10.7759/cureus.24755

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 0.1% of the US population.1,2 Severe disease or HS flares can lead patients to seek care through the emergency department (ED), with some requiring inpatient admission. 3 Inpatient hospitalization of patients with HS has increased over the last 2 decades, and patients with HS utilize emergency and inpatient care more frequently than those with other dermatologic conditions.4,5 Minority patients and those of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to present to the ED for HS management due to limited access to care and other existing comorbid conditions. 4 In a 2022 study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the authors looked at hospital readmission rates of patients with HS compared with those with heart failure—both patient populations with chronic debilitating conditions. Results indicated that the hospital readmission rates for patients with HS surpassed those of patients with heart failure for that year, highlighting the need for improved inpatient management of HS.6

Patients with HS present to the ED with severe pain, fever, wound care, or the need for surgical intervention. The ED and inpatient hospital setting are locations in which physicians may not be as familiar with the diagnosis or treatment of HS, specifically flares or severe disease. 7 The inpatient care setting provides access to certain resources that can be challenging to obtain in the outpatient clinical setting, such as social workers and pain specialists, but also can prove challenging in obtaining other resources for HS management, such as advanced medical therapies. Given the increase in hospital- based care for HS and lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial. In our study, we sought to generate a collection of expert consensus statements providers can refer to when managing patients with HS in the inpatient setting.

Methods

The study team at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(M.N., R.P., L.C.S.) developed an initial set of consensus statements based on current published HS treatment guidelines,8,9 publications on management of inpatient HS,3 published supportive care guidelines for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, 10 and personal clinical experience in managing inpatient HS, which resulted in 50 statements organized into the following categories: overall care, wound care, genital care, pain management, infection control, medical management, surgical management, nutrition, and transitional care guidelines. This study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (IRB00084257).

Participant Recruitment—Dermatologists were identified for participation in the study based on membership in the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation or authorship of publications relevant to HS or inpatient dermatology. Dermatologists from larger academic institutions with HS specialty clinics and inpatient dermatology services also were identified. Participants were invited via email and could suggest other experts for inclusion. A total of 31 dermatologists were invited to participate in the study, with 26 agreeing to participate. All participating dermatologists were practicing in the United States.

Delphi Study—In the first round of the Delphi study, the participants were sent an online survey via REDCap in which they were asked to rank the appropriateness of each of the proposed 50 guideline statements on a scale of 1 (very inappropriate) to 9 (very appropriate). Participants also were able to provide commentary and feedback on each of the statements. Survey results were analyzed using the RAND/ UCLA Appropriateness Method.11 For each statement, the median rating for appropriateness, interpercentile range (IPR), IPR adjusted for symmetry, and disagreement index (DI) were calculated (DI=IPR/IPR adjusted for symmetry). The 30th and 70th percentiles were used in the DI calculation as the upper and lower limits, respectively. A median rating for appropriateness of 1.0 to 3.9 was considered “inappropriate,” 4.0 to 6.9 was considered “uncertain appropriateness,” and 7.0 to 9.0 was “appropriate.” A DI value greater than or equal to 1 indicated a lack of consensus regarding the appropriateness of the statement. Following each round, participants received a copy of their responses along with the group median rank of each statement. Statements that did not reach consensus in the first Delphi round were revised based on feedback received by the participants, and a second survey with 14 statements was sent via REDCap 2 weeks later. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method also was applied to this second Delphi round. After the second survey, participants received a copy of anonymized comments regarding the consensus statements and were allowed to provide additional final commentary to be included in the discussion of these recommendations.

Results

Twenty-six dermatologists completed the first-round survey, and 24 participants completed the second-round survey. All participants self-identified as having expertise in either HS (n=22 [85%]) or inpatient dermatology (n=17 [65%]), and 13 (50%) participants self-identified as experts in both HS and inpatient dermatology. All participants, except 1, were affiliated with an academic health system with inpatient dermatology services. The average length of time in practice as a dermatologist was 10 years (median, 9 years [range, 3–27 years]).

Of the 50 initial proposed consensus statements, 26 (52%) achieved consensus after the first round; 21 statements revealed DI calculations that did not achieve consensus. Two statements achieved consensus but received median ratings for appropriateness, indicating uncertain appropriateness; because of this, 1 statement was removed and 1 was revised based on participant feedback, resulting in 13 revised statements (eTable 1). Controversial topics in the consensus process included obtaining wound cultures and meaningful culture data interpretation, use of specific biologic medications in the inpatient setting, and use of intravenous ertapenem. Participant responses to these topics are discussed in detail below. Of these secondround statements, all achieved consensus. The final set of consensus statements can be found in eTable 2.

Comment

Our Delphi consensus study combined the expertise of both dermatologists who care for patients with HS and those with inpatient dermatology experience to produce a set of recommendations for the management of HS in the hospital care setting. A strength of this study is inclusion of many national leaders in both HS and inpatient dermatology, with some participants having developed the previously published HS treatment guidelines and others having participated in inpatient dermatology Delphi studies.8-10 The expertise is further strengthened by the geographically diverse institutional representation within the United States.

The final consensus recommendations included 40 statements covering a range of patient care issues, including use of appropriate inpatient subspecialists (care team), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition back to outpatient management (transitional care). These recommendations are meant to serve as a resource for providers to consider when taking care of inpatient HS flares, recognizing that the complexity and individual circumstances of each patient are unique.

Delphi Consensus Recommendations Compared to Prior Guidelines—Several recommendations in the current study align with the previously published North American clinical management guidelines for HS.8,9 Our recommendations agree with prior guidelines on the importance of disease staging and pain assessment using validated assessment tools as well as screening for HS comorbidities. There also is agreement in the potential benefit of involving pain specialists in the development of a comprehensive pain management plan. The inpatient care setting provides a unique opportunity to engage multiple specialists and collaborate on patient care in a timely manner. Our recommendations regarding surgical care also align with established guidelines in recommending incision and drainage as an acute bedside procedure best utilized for symptom relief in inflamed abscesses and relegating most other surgical management to the outpatient setting. Wound care recommendations also are similar, with our expert participants agreeing on individualizing dressing choices based on wound characteristics. A benefit of inpatient wound care is access to skilled nursing for dressing changes and potentially improved access to more sophisticated dressing materials. Our recommendations differ from the prior guidelines in our focus on severe HS, HS flares, and HS complications, which constitute the majority of inpatient disease management. We provide additional guidance on management of secondary infections, perianal fistulous disease, and importantly transitional care to optimize discharge planning.

Differing Opinions in Our Analysis—Despite the success of our Delphi consensus process, there were some differing opinions regarding certain aspects of inpatient HS management, which is to be expected given the lack of strong evidence-based research to support some of the recommended practices. There were differing opinions on the utility of wound culture data, with some participants feeling culture data could help with antibiotic susceptibility and resistance patterns, while others felt wound cultures represent bacterial colonization or biofilm formation.

Initial consensus statements in the first Delphi round were created for individual biologic medications but did not achieve consensus, and feedback on the use of biologics in the inpatient environment was mixed, largely due to logistic and insurance issues. Many participants felt biologic medication cost, difficulty obtaining inpatient reimbursement, health care resource utilization, and availability of biologics in different hospital systems prevented recommending the use of specific biologics during hospitalization. The one exception was in the case of a hospitalized patient who was already receiving infliximab for HS: there was consensus on ensuring the patient dosing was maximized, if appropriate, to 10 mg/kg.12 Ertapenem use also was controversial, with some participants using it as a bridge therapy to either outpatient biologic use or surgery, while others felt it was onerous and difficult to establish reliable access to secure intravenous administration and regular dosing once the patient left the inpatient setting.13 Others said they have experienced objections from infectious disease colleagues on the use of intravenous antibiotics, citing antibiotic stewardship concerns.

Patient Care in the Inpatient Setting—Prior literature suggests patients admitted as inpatients for HS tend to be of lower socioeconomic status and are admitted to larger urban teaching hospitals.14,15 Patients with lower socioeconomic status have increased difficulty accessing health care resources; therefore, inpatient admission serves as an opportunity to provide a holistic HS assessment and coordinate resources for chronic outpatient management.

Study Limitations—This Delphi consensus study has some limitations. The existing literature on inpatient management of HS is limited, challenging our ability to assess the extent to which these published recommendations are already being implemented. Additionally, the study included HS and inpatient dermatology experts from the United States, which means the recommendations may not be generalizable to other countries. Most participants practiced dermatology at large tertiary care academic medical centers, which may limit the ability to implement recommendations in all US inpatient care settings such as small community-based hospitals; however, many of the supportive care guidelines such as pain control, wound care, nutritional support, and social work should be achievable in most inpatient care settings.

Conclusion

Given the increase in inpatient and ED health care utilization for HS, there is an urgent need for expert consensus recommendations on inpatient management of this unique patient population, which requires complex multidisciplinary care. Our recommendations are a resource for providers to utilize and potentially improve the standard of care we provide these patients.

Acknowledgment—We thank the Wake Forest University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston- Salem, North Carolina) for providing statistical help.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 0.1% of the US population.1,2 Severe disease or HS flares can lead patients to seek care through the emergency department (ED), with some requiring inpatient admission. 3 Inpatient hospitalization of patients with HS has increased over the last 2 decades, and patients with HS utilize emergency and inpatient care more frequently than those with other dermatologic conditions.4,5 Minority patients and those of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to present to the ED for HS management due to limited access to care and other existing comorbid conditions. 4 In a 2022 study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the authors looked at hospital readmission rates of patients with HS compared with those with heart failure—both patient populations with chronic debilitating conditions. Results indicated that the hospital readmission rates for patients with HS surpassed those of patients with heart failure for that year, highlighting the need for improved inpatient management of HS.6

Patients with HS present to the ED with severe pain, fever, wound care, or the need for surgical intervention. The ED and inpatient hospital setting are locations in which physicians may not be as familiar with the diagnosis or treatment of HS, specifically flares or severe disease. 7 The inpatient care setting provides access to certain resources that can be challenging to obtain in the outpatient clinical setting, such as social workers and pain specialists, but also can prove challenging in obtaining other resources for HS management, such as advanced medical therapies. Given the increase in hospital- based care for HS and lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial. In our study, we sought to generate a collection of expert consensus statements providers can refer to when managing patients with HS in the inpatient setting.

Methods

The study team at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(M.N., R.P., L.C.S.) developed an initial set of consensus statements based on current published HS treatment guidelines,8,9 publications on management of inpatient HS,3 published supportive care guidelines for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, 10 and personal clinical experience in managing inpatient HS, which resulted in 50 statements organized into the following categories: overall care, wound care, genital care, pain management, infection control, medical management, surgical management, nutrition, and transitional care guidelines. This study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (IRB00084257).

Participant Recruitment—Dermatologists were identified for participation in the study based on membership in the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation or authorship of publications relevant to HS or inpatient dermatology. Dermatologists from larger academic institutions with HS specialty clinics and inpatient dermatology services also were identified. Participants were invited via email and could suggest other experts for inclusion. A total of 31 dermatologists were invited to participate in the study, with 26 agreeing to participate. All participating dermatologists were practicing in the United States.

Delphi Study—In the first round of the Delphi study, the participants were sent an online survey via REDCap in which they were asked to rank the appropriateness of each of the proposed 50 guideline statements on a scale of 1 (very inappropriate) to 9 (very appropriate). Participants also were able to provide commentary and feedback on each of the statements. Survey results were analyzed using the RAND/ UCLA Appropriateness Method.11 For each statement, the median rating for appropriateness, interpercentile range (IPR), IPR adjusted for symmetry, and disagreement index (DI) were calculated (DI=IPR/IPR adjusted for symmetry). The 30th and 70th percentiles were used in the DI calculation as the upper and lower limits, respectively. A median rating for appropriateness of 1.0 to 3.9 was considered “inappropriate,” 4.0 to 6.9 was considered “uncertain appropriateness,” and 7.0 to 9.0 was “appropriate.” A DI value greater than or equal to 1 indicated a lack of consensus regarding the appropriateness of the statement. Following each round, participants received a copy of their responses along with the group median rank of each statement. Statements that did not reach consensus in the first Delphi round were revised based on feedback received by the participants, and a second survey with 14 statements was sent via REDCap 2 weeks later. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method also was applied to this second Delphi round. After the second survey, participants received a copy of anonymized comments regarding the consensus statements and were allowed to provide additional final commentary to be included in the discussion of these recommendations.

Results

Twenty-six dermatologists completed the first-round survey, and 24 participants completed the second-round survey. All participants self-identified as having expertise in either HS (n=22 [85%]) or inpatient dermatology (n=17 [65%]), and 13 (50%) participants self-identified as experts in both HS and inpatient dermatology. All participants, except 1, were affiliated with an academic health system with inpatient dermatology services. The average length of time in practice as a dermatologist was 10 years (median, 9 years [range, 3–27 years]).

Of the 50 initial proposed consensus statements, 26 (52%) achieved consensus after the first round; 21 statements revealed DI calculations that did not achieve consensus. Two statements achieved consensus but received median ratings for appropriateness, indicating uncertain appropriateness; because of this, 1 statement was removed and 1 was revised based on participant feedback, resulting in 13 revised statements (eTable 1). Controversial topics in the consensus process included obtaining wound cultures and meaningful culture data interpretation, use of specific biologic medications in the inpatient setting, and use of intravenous ertapenem. Participant responses to these topics are discussed in detail below. Of these secondround statements, all achieved consensus. The final set of consensus statements can be found in eTable 2.

Comment

Our Delphi consensus study combined the expertise of both dermatologists who care for patients with HS and those with inpatient dermatology experience to produce a set of recommendations for the management of HS in the hospital care setting. A strength of this study is inclusion of many national leaders in both HS and inpatient dermatology, with some participants having developed the previously published HS treatment guidelines and others having participated in inpatient dermatology Delphi studies.8-10 The expertise is further strengthened by the geographically diverse institutional representation within the United States.

The final consensus recommendations included 40 statements covering a range of patient care issues, including use of appropriate inpatient subspecialists (care team), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition back to outpatient management (transitional care). These recommendations are meant to serve as a resource for providers to consider when taking care of inpatient HS flares, recognizing that the complexity and individual circumstances of each patient are unique.

Delphi Consensus Recommendations Compared to Prior Guidelines—Several recommendations in the current study align with the previously published North American clinical management guidelines for HS.8,9 Our recommendations agree with prior guidelines on the importance of disease staging and pain assessment using validated assessment tools as well as screening for HS comorbidities. There also is agreement in the potential benefit of involving pain specialists in the development of a comprehensive pain management plan. The inpatient care setting provides a unique opportunity to engage multiple specialists and collaborate on patient care in a timely manner. Our recommendations regarding surgical care also align with established guidelines in recommending incision and drainage as an acute bedside procedure best utilized for symptom relief in inflamed abscesses and relegating most other surgical management to the outpatient setting. Wound care recommendations also are similar, with our expert participants agreeing on individualizing dressing choices based on wound characteristics. A benefit of inpatient wound care is access to skilled nursing for dressing changes and potentially improved access to more sophisticated dressing materials. Our recommendations differ from the prior guidelines in our focus on severe HS, HS flares, and HS complications, which constitute the majority of inpatient disease management. We provide additional guidance on management of secondary infections, perianal fistulous disease, and importantly transitional care to optimize discharge planning.

Differing Opinions in Our Analysis—Despite the success of our Delphi consensus process, there were some differing opinions regarding certain aspects of inpatient HS management, which is to be expected given the lack of strong evidence-based research to support some of the recommended practices. There were differing opinions on the utility of wound culture data, with some participants feeling culture data could help with antibiotic susceptibility and resistance patterns, while others felt wound cultures represent bacterial colonization or biofilm formation.

Initial consensus statements in the first Delphi round were created for individual biologic medications but did not achieve consensus, and feedback on the use of biologics in the inpatient environment was mixed, largely due to logistic and insurance issues. Many participants felt biologic medication cost, difficulty obtaining inpatient reimbursement, health care resource utilization, and availability of biologics in different hospital systems prevented recommending the use of specific biologics during hospitalization. The one exception was in the case of a hospitalized patient who was already receiving infliximab for HS: there was consensus on ensuring the patient dosing was maximized, if appropriate, to 10 mg/kg.12 Ertapenem use also was controversial, with some participants using it as a bridge therapy to either outpatient biologic use or surgery, while others felt it was onerous and difficult to establish reliable access to secure intravenous administration and regular dosing once the patient left the inpatient setting.13 Others said they have experienced objections from infectious disease colleagues on the use of intravenous antibiotics, citing antibiotic stewardship concerns.

Patient Care in the Inpatient Setting—Prior literature suggests patients admitted as inpatients for HS tend to be of lower socioeconomic status and are admitted to larger urban teaching hospitals.14,15 Patients with lower socioeconomic status have increased difficulty accessing health care resources; therefore, inpatient admission serves as an opportunity to provide a holistic HS assessment and coordinate resources for chronic outpatient management.

Study Limitations—This Delphi consensus study has some limitations. The existing literature on inpatient management of HS is limited, challenging our ability to assess the extent to which these published recommendations are already being implemented. Additionally, the study included HS and inpatient dermatology experts from the United States, which means the recommendations may not be generalizable to other countries. Most participants practiced dermatology at large tertiary care academic medical centers, which may limit the ability to implement recommendations in all US inpatient care settings such as small community-based hospitals; however, many of the supportive care guidelines such as pain control, wound care, nutritional support, and social work should be achievable in most inpatient care settings.

Conclusion

Given the increase in inpatient and ED health care utilization for HS, there is an urgent need for expert consensus recommendations on inpatient management of this unique patient population, which requires complex multidisciplinary care. Our recommendations are a resource for providers to utilize and potentially improve the standard of care we provide these patients.

Acknowledgment—We thank the Wake Forest University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston- Salem, North Carolina) for providing statistical help.

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:990-998. doi:10.1111/bjd.19435

- Charrow A, Savage KT, Flood K, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa for the dermatologic hospitalist. Cutis. 2019;104:276-280.

- Anzaldi L, Perkins JA, Byrd AS, et al. Characterizing inpatient hospitalizations for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:510-513. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.019

- Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:609-614. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053

- Edigin E, Kaul S, Eseaton PO, et al. At 180 days hidradenitis suppurativa readmission rate is comparable to heart failure: analysis of the nationwide readmissions database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:188-192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.894

- Kirby JS, Miller JJ, Adams DR, et al. Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:937-944. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.691

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2019.02.067

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2020.02.066

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Burnand B, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method: User’s Manual. Rand; 2001.

- Oskardmay AN, Miles JA, Sayed CJ. Determining the optimal dose of infliximab for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:702-708. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.022

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard-Biehler H, Jais JP, et al. Efficacy of ertapenem in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study in a cohort of 30 consecutive patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:513-520. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv361

- Khanna R, Whang KA, Huang AH, et al. Inpatient burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: analysis of the 2016 National Inpatient Sample. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1150-1152. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2020.1773380

- Patel A, Patel A, Solanki D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: insights from the national inpatient sample (2008-2017) on contemporary trends in demographics, hospitalization rates, chronic comorbid conditions, and mortality. Cureus. 2022;14:E24755. doi:10.7759/cureus.24755

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:990-998. doi:10.1111/bjd.19435

- Charrow A, Savage KT, Flood K, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa for the dermatologic hospitalist. Cutis. 2019;104:276-280.

- Anzaldi L, Perkins JA, Byrd AS, et al. Characterizing inpatient hospitalizations for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:510-513. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.019

- Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:609-614. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053

- Edigin E, Kaul S, Eseaton PO, et al. At 180 days hidradenitis suppurativa readmission rate is comparable to heart failure: analysis of the nationwide readmissions database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:188-192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.894

- Kirby JS, Miller JJ, Adams DR, et al. Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:937-944. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.691

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2019.02.067

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2020.02.066

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Burnand B, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method: User’s Manual. Rand; 2001.

- Oskardmay AN, Miles JA, Sayed CJ. Determining the optimal dose of infliximab for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:702-708. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.022

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard-Biehler H, Jais JP, et al. Efficacy of ertapenem in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study in a cohort of 30 consecutive patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:513-520. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv361

- Khanna R, Whang KA, Huang AH, et al. Inpatient burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: analysis of the 2016 National Inpatient Sample. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1150-1152. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2020.1773380

- Patel A, Patel A, Solanki D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: insights from the national inpatient sample (2008-2017) on contemporary trends in demographics, hospitalization rates, chronic comorbid conditions, and mortality. Cureus. 2022;14:E24755. doi:10.7759/cureus.24755

Practice Points

- Given the increase in hospital-based care for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and the lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial.

- Our Delphi study yielded 40 statements that reached consensus covering a range of patient care issues (eg, appropriate inpatient subspecialists [care team]), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition to outpatient management (transitional care).

- These recommendations serve as an important resource for providers caring for inpatients with HS and represent a successful collaboration between inpatient dermatology and HS experts.

E-Consults in Dermatology: A Retrospective Analysis

Dermatologic conditions affect approximately one-third of individuals in the United States.1,2 Nearly 1 in 4 physician office visits in the United States are for skin conditions, and less than one-third of these visits are with dermatologists. Although many of these patients may prefer to see a dermatologist for their concerns, they may not be able to access specialist care.3 The limited supply and urban-focused distribution of dermatologists along with reduced acceptance of state-funded insurance plans and long appointment wait times all pose considerable challenges to individuals seeking dermatologic care.2 Electronic consultations (e-consults) have emerged as a promising solution to overcoming these barriers while providing high-quality dermatologic care to a large diverse patient population.2,4 Although e-consults can be of service to all dermatology patients, this modality may be especially beneficial to underserved populations, such as the uninsured and Medicaid patients—groups that historically have experienced limited access to dermatology care due to the low reimbursement rates and high administrative burdens accompanying care delivery.4 This limited access leads to inequity in care, as timely access to dermatology is associated with improved diagnostic accuracy and disease outcomes.3 E-consult implementation can facilitate timely access for these underserved populations and bypass additional barriers to care such as lack of transportation or time off work. Prior e-consult studies have demonstrated relatively high numbers of Medicaid patients utilizing e-consult services.3,5

Although in-person visits remain the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, e-consults placed by primary care providers (PCPs) can improve access and help triage patients who require in-person dermatology visits.6 In this study, we conducted a retrospective chart review to characterize the e-consults requested of the dermatology department at a large tertiary care medical center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Methods

The electronic health record (EHR) of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) was screened for eligible patients from January 1, 2020, to May 31, 2021. Patients—both adult (aged ≥18 years) and pediatric (aged <18 years)—were included if they underwent a dermatology e-consult within this time frame. Provider notes in the medical records were reviewed to determine the nature of the lesion, how long the dermatologist took to complete the e-consult, whether an in-person appointment was recommended, and whether the patient was seen by dermatology within 90 days of the e-consult. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

For each e-consult, the PCP obtained clinical photographs of the lesion in question either through the EHR mobile application or by having patients upload their own photographs directly to their medical records. The referring PCP then completed a brief template regarding the patient’s clinical question and medical history and then sent the completed information to the consulting dermatologist’s EHR inbox. From there, the dermatologist could view the clinical question, documented photographs, and patient medical record to create a brief consult note with recommendations. The note was then sent back via EHR to the PCP to follow up with the patient. Patients were not charged for the e-consult.

Results

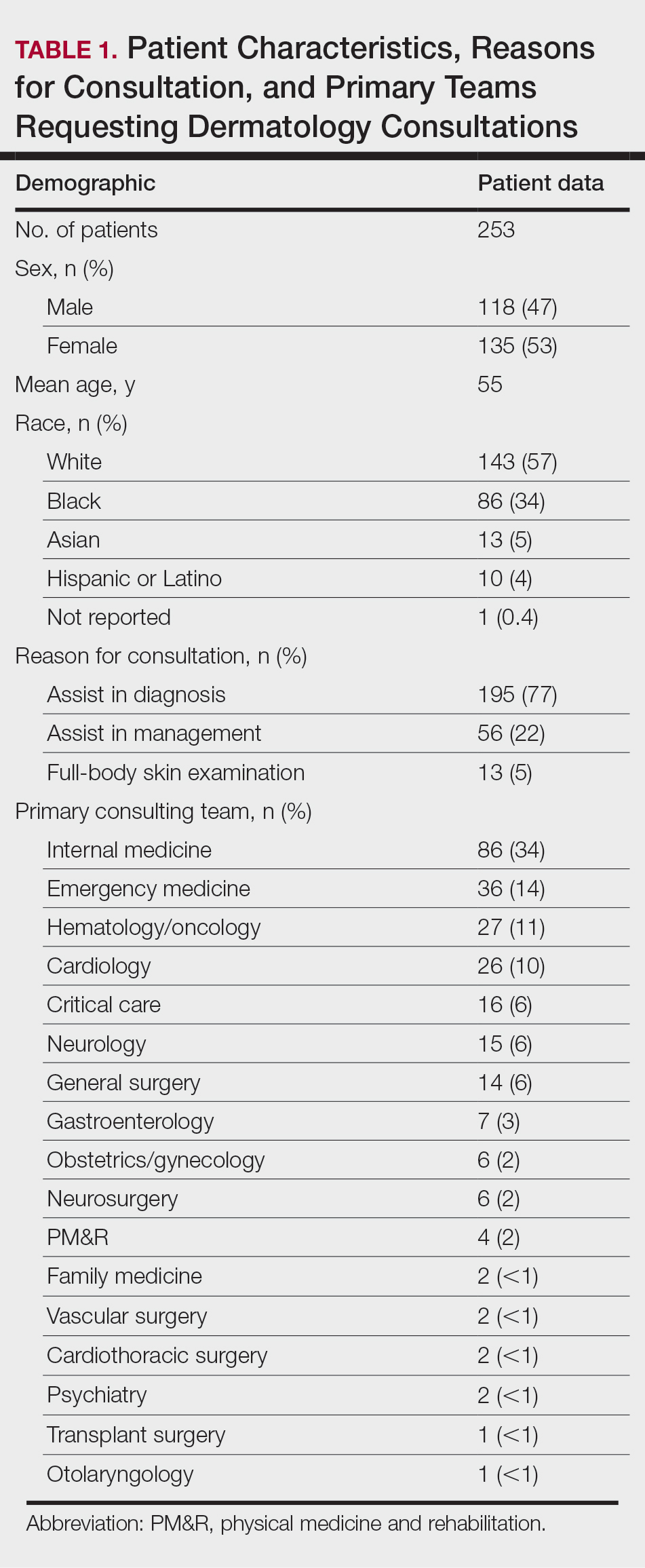

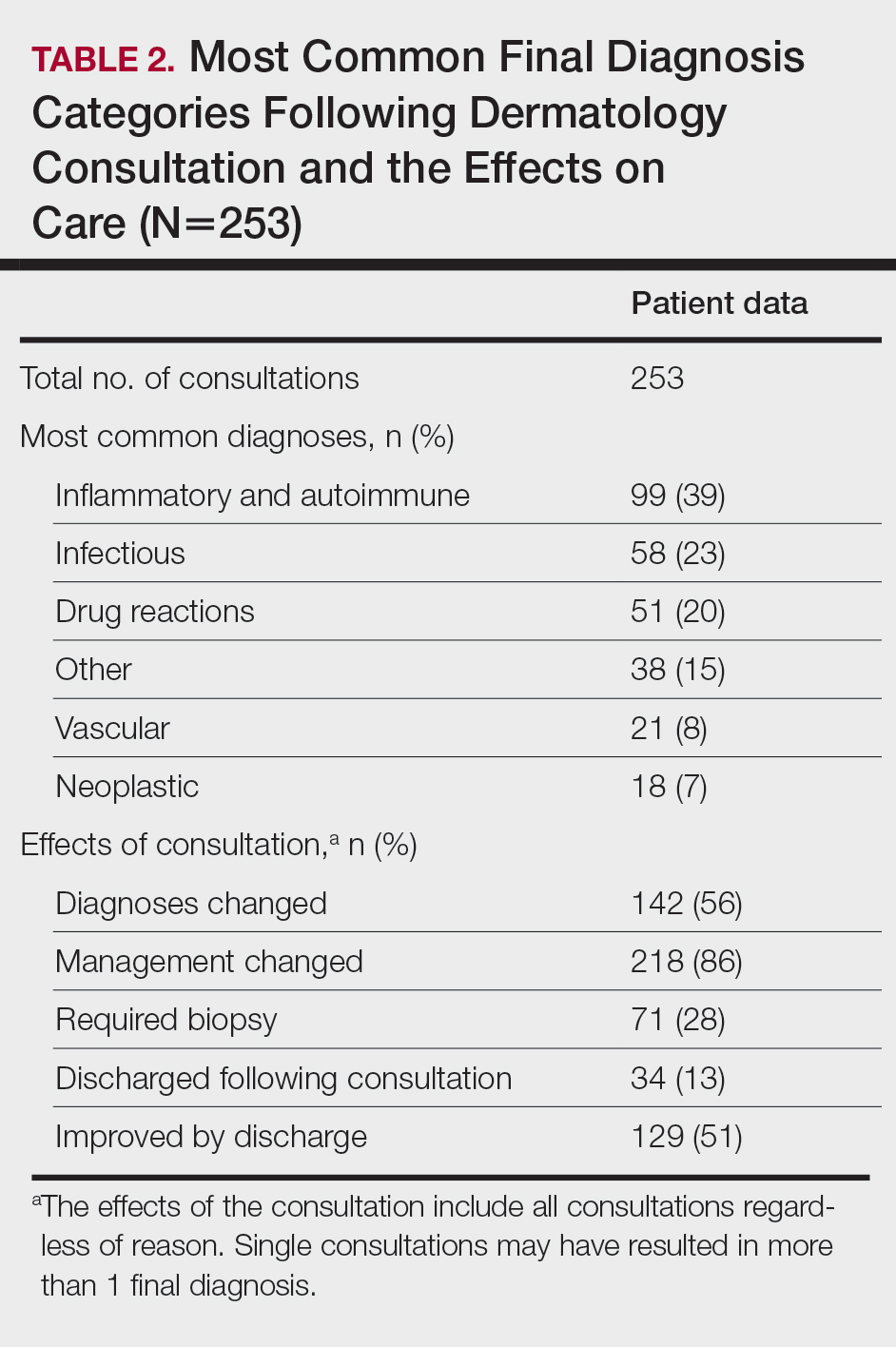

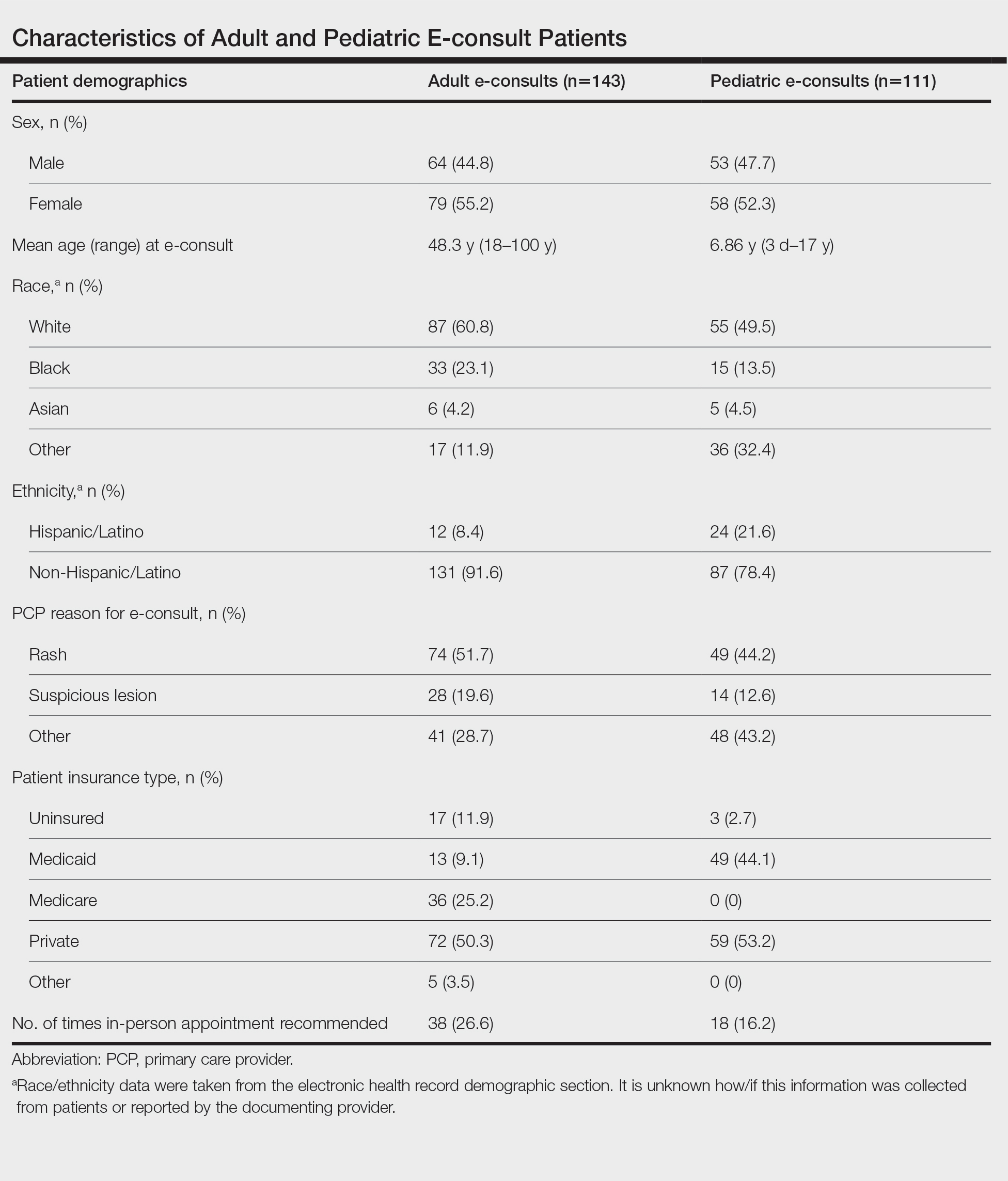

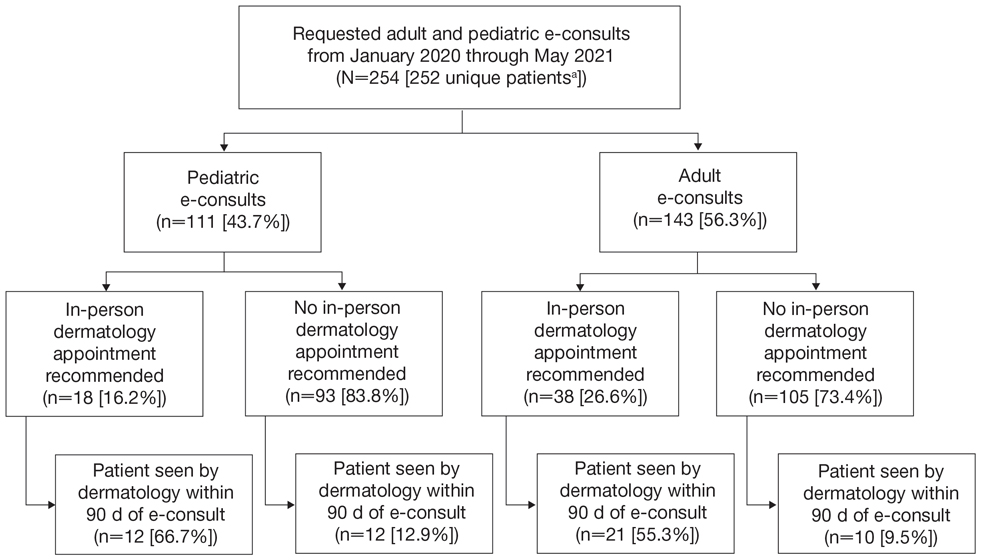

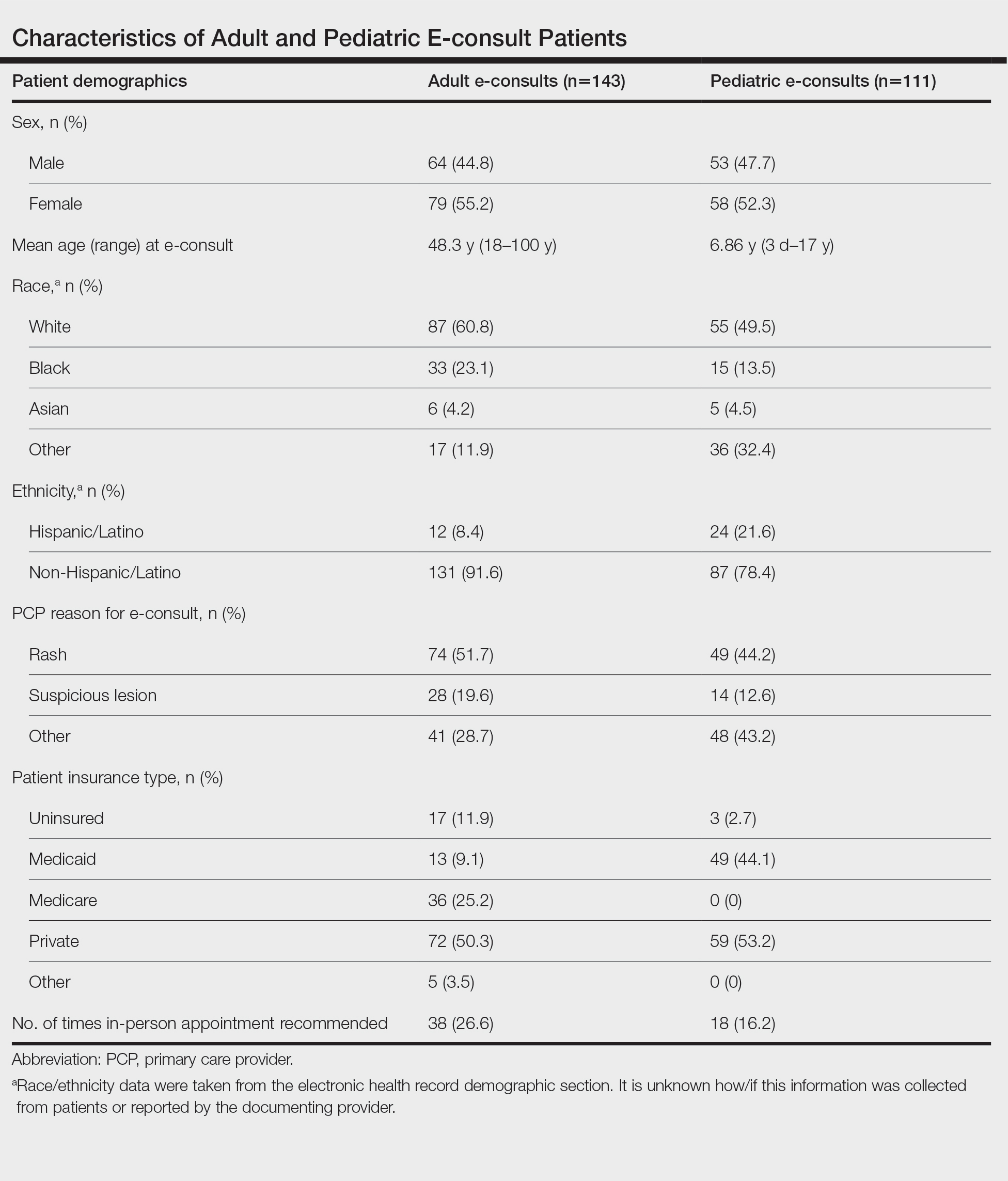

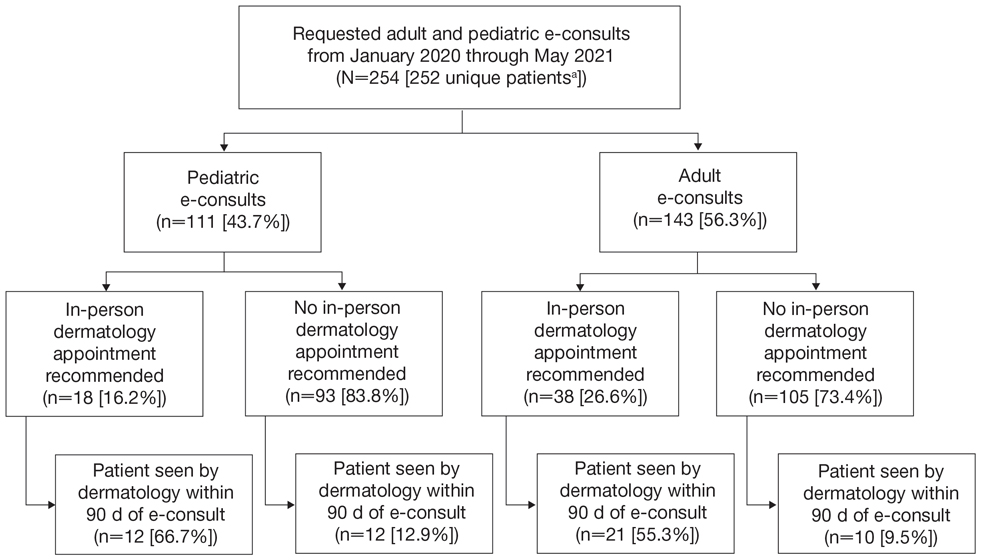

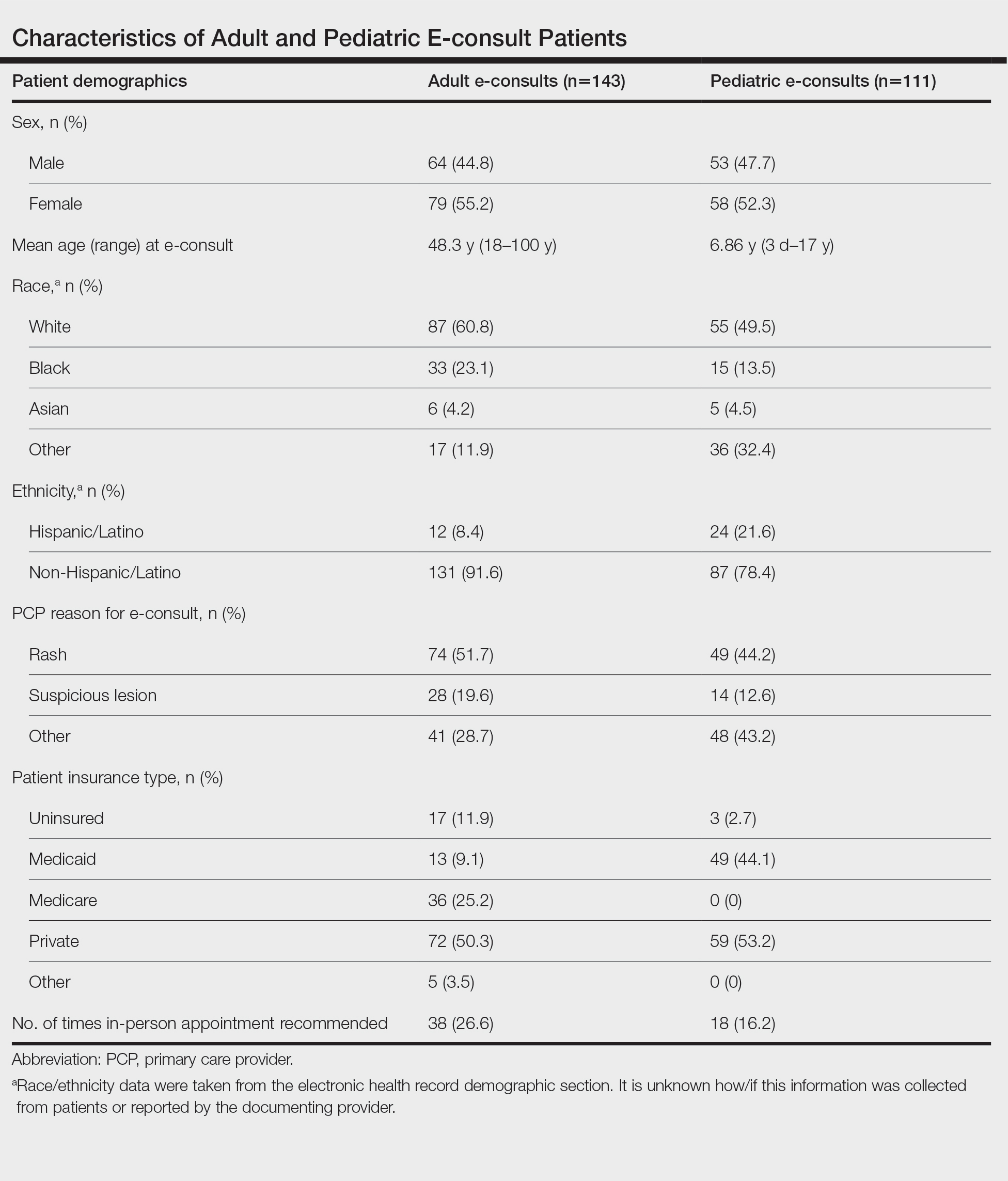

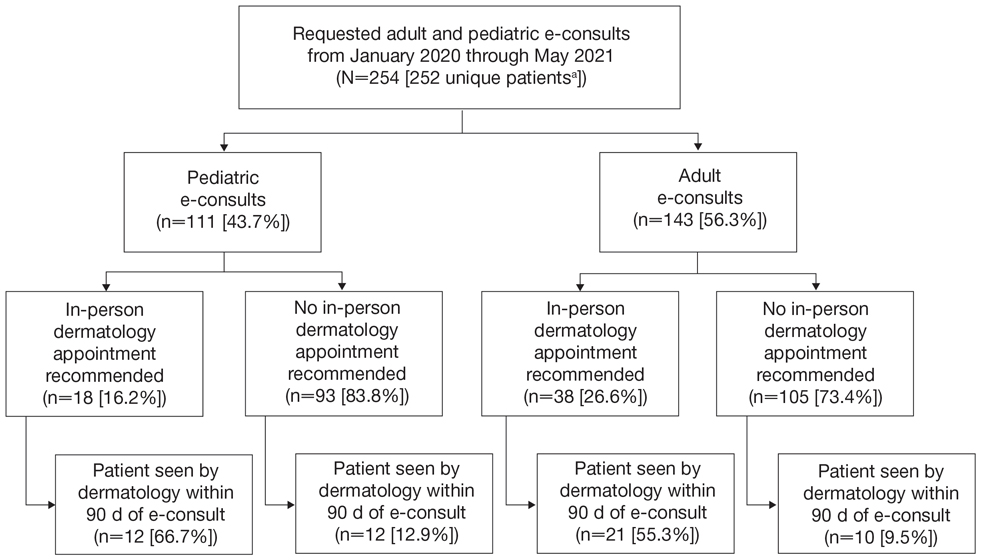

Two hundred fifty-four dermatology e-consults were requested by providers at the study center (eTable), which included 252 unique patients (2 patients had 2 separate e-consults regarding different clinical questions). The median time for completion of the e-consult—from submission of the PCP’s e-consult request to dermatologist completion—was 0.37 days. Fifty-six patients (22.0%) were recommended for an in-person appointment (Figure), 33 (58.9%) of whom ultimately scheduled the in-person appointment, and the median length of time between the completion of the e-consult and the in-person appointment was 16.5 days. The remaining 198 patients (78.0%) were not triaged to receive an in-person appointment following the e-consult,but 2 patients (8.7%) were ultimately seen in-person anyway via other referral pathways, with a median length of 33 days between e-consult completion and the in-person appointment. One hundred seventy-six patients (69.8%) avoided an in-person dermatology visit, although 38 (21.6%) of those patients were fewer than 90 days out from their e-consults at the time of data collection. The 254 e-consults included patients from 50 different zip codes, 49 (98.0%) of which were in North Carolina.

Comment

An e-consult is an asynchronous telehealth modality through which PCPs can request specialty evaluation to provide diagnostic and therapeutic guidance, facilitate PCP-specialist coordination of care, and increase access to specialty care with reduced wait times.7,8 Increased care access is especially important, as specialty referral can decrease overall health care expenditure; however, the demand for specialists often exceeds the availability.8 Our e-consult program drastically reduced the time from patients’ initial presentation at their PCP’s office to dermatologist recommendations for treatment or need for in-person dermatology follow-up.

In our analysis, patients were of different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and lived across a variety of zip codes, predominantly in central and western North Carolina. Almost three-quarters of the patients resided in zip codes where the average income was less than the North Carolina median household income ($66,196).9 Additionally, 82 patients (32.3%) were uninsured or on Medicaid (eTable). These economically disadvantaged patient populations historically have had limited access to dermatologic care.4 One study showed that privately insured individuals were accepted as new patients by dermatologists 91% of the time compared to a 29.8% acceptance rate for publicly insured individuals.10 Uninsured and Medicaid patients also have to wait 34% longer for an appointment compared to individuals with Medicare or private insurance.2 Considering these patients may already be at an economic disadvantage when it comes to seeing and paying for dermatologic services, e-consults may reduce patient travel and appointment expenses while increasing access to specialty care. Based on a 2020 study, each e-consult generates an estimated savings of $80 out-of-pocket per patient per avoided in-person visit.11

In our study, the most common condition for an e-consult in both adult and pediatric patients was rash, which is consistent with prior e-consult studies.5,11 We found that most e-consult patients were not recommended for an in-person dermatology visit, and for those who were recommended to have an in-person visit, the wait time was reduced (Figure). These results corroborate that e-consults may be used as an important triage tool for determining whether a specialist appointment is indicated as well as a public health tool, as timely evaluation is associated with better dermatologic health care outcomes.3 However, the number of patients who did not present for an in-person appointment in our study may be overestimated, as 38 patients’ (21.6%) e-consults were conducted fewer than 90 days before our data collection. Although none of these patients had been seen in person, it is possible they requested an in-person visit after their medical records were reviewed for this study. Additionally, it is possible patients sought care from outside providers not documented in the EHR.

With regard to the payment model for the e-consult program, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist initially piloted the e-consult system through a partnership with the American Academy of Medical Colleges’ Project CORE: Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/health-care/project-core). Grant funding through Project CORE allowed both the referring PCP and the specialist completing the e-consult to each receive approximately 0.5 relative value units in payment for each consult completed. Based on early adoption successes, the institution has created additional internal funding to support the continued expansion of the e-consult system and is incentivized to continue funding, as proper utilization of e-consults improves patient access to timely specialist care, avoids no-shows or last-minute cancellations for specialist appointments, and decreases back-door access to specialist care through the emergency department and urgent care facilities.5 Although 0.5 relative value units is not equivalent compensation to an in-person office visit, our study showed that e-consults can be completed much more quickly and efficiently and do not utilize nursing staff or other office resources.

Conclusion

E-consults are an effective telehealth modality that can increase patients’ access to dermatologic specialty care.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Department of Medical Education and Department of Dermatology (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their contributions to this research study as well as the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their help extracting EHR data.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Naka F, Lu J, Porto A, et al. Impact of dermatology econsults on access to care and skin cancer screening in underserved populations: a model for teledermatology services in community health centers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:293-302.

- Mulcahy A, Mehrotra A, Edison K, et al. Variation in dermatologist visits by sociodemographic characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:918-924.

- Yang X, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL. Cost analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology consult system in Philadelphia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:758-764.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an econsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1633-1638.

- Lee KJ, Finnane A, Soyer HP. Recent trends in teledermatology and teledermoscopy. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:214-223.

- Parikh PJ, Mowrey C, Gallimore J, et al. Evaluating e-consultation implementations based on use and time-line across various specialties. Int J Med Inform. 2017;108:42-48.

- Wasfy JH, Rao SK, Kalwani N, et al. Longer-term impact of cardiology e-consults. Am Heart J. 2016;173:86-93.

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: North Carolina; United States. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NC,US/PST045222

- Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander Horst A, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

- Seiger K, Hawryluk EB, Kroshinsky D, et al. Pediatric dermatology econsults: reduced wait times and dermatology office visits. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:804-810.

Dermatologic conditions affect approximately one-third of individuals in the United States.1,2 Nearly 1 in 4 physician office visits in the United States are for skin conditions, and less than one-third of these visits are with dermatologists. Although many of these patients may prefer to see a dermatologist for their concerns, they may not be able to access specialist care.3 The limited supply and urban-focused distribution of dermatologists along with reduced acceptance of state-funded insurance plans and long appointment wait times all pose considerable challenges to individuals seeking dermatologic care.2 Electronic consultations (e-consults) have emerged as a promising solution to overcoming these barriers while providing high-quality dermatologic care to a large diverse patient population.2,4 Although e-consults can be of service to all dermatology patients, this modality may be especially beneficial to underserved populations, such as the uninsured and Medicaid patients—groups that historically have experienced limited access to dermatology care due to the low reimbursement rates and high administrative burdens accompanying care delivery.4 This limited access leads to inequity in care, as timely access to dermatology is associated with improved diagnostic accuracy and disease outcomes.3 E-consult implementation can facilitate timely access for these underserved populations and bypass additional barriers to care such as lack of transportation or time off work. Prior e-consult studies have demonstrated relatively high numbers of Medicaid patients utilizing e-consult services.3,5

Although in-person visits remain the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, e-consults placed by primary care providers (PCPs) can improve access and help triage patients who require in-person dermatology visits.6 In this study, we conducted a retrospective chart review to characterize the e-consults requested of the dermatology department at a large tertiary care medical center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Methods

The electronic health record (EHR) of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) was screened for eligible patients from January 1, 2020, to May 31, 2021. Patients—both adult (aged ≥18 years) and pediatric (aged <18 years)—were included if they underwent a dermatology e-consult within this time frame. Provider notes in the medical records were reviewed to determine the nature of the lesion, how long the dermatologist took to complete the e-consult, whether an in-person appointment was recommended, and whether the patient was seen by dermatology within 90 days of the e-consult. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

For each e-consult, the PCP obtained clinical photographs of the lesion in question either through the EHR mobile application or by having patients upload their own photographs directly to their medical records. The referring PCP then completed a brief template regarding the patient’s clinical question and medical history and then sent the completed information to the consulting dermatologist’s EHR inbox. From there, the dermatologist could view the clinical question, documented photographs, and patient medical record to create a brief consult note with recommendations. The note was then sent back via EHR to the PCP to follow up with the patient. Patients were not charged for the e-consult.

Results

Two hundred fifty-four dermatology e-consults were requested by providers at the study center (eTable), which included 252 unique patients (2 patients had 2 separate e-consults regarding different clinical questions). The median time for completion of the e-consult—from submission of the PCP’s e-consult request to dermatologist completion—was 0.37 days. Fifty-six patients (22.0%) were recommended for an in-person appointment (Figure), 33 (58.9%) of whom ultimately scheduled the in-person appointment, and the median length of time between the completion of the e-consult and the in-person appointment was 16.5 days. The remaining 198 patients (78.0%) were not triaged to receive an in-person appointment following the e-consult,but 2 patients (8.7%) were ultimately seen in-person anyway via other referral pathways, with a median length of 33 days between e-consult completion and the in-person appointment. One hundred seventy-six patients (69.8%) avoided an in-person dermatology visit, although 38 (21.6%) of those patients were fewer than 90 days out from their e-consults at the time of data collection. The 254 e-consults included patients from 50 different zip codes, 49 (98.0%) of which were in North Carolina.

Comment

An e-consult is an asynchronous telehealth modality through which PCPs can request specialty evaluation to provide diagnostic and therapeutic guidance, facilitate PCP-specialist coordination of care, and increase access to specialty care with reduced wait times.7,8 Increased care access is especially important, as specialty referral can decrease overall health care expenditure; however, the demand for specialists often exceeds the availability.8 Our e-consult program drastically reduced the time from patients’ initial presentation at their PCP’s office to dermatologist recommendations for treatment or need for in-person dermatology follow-up.

In our analysis, patients were of different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and lived across a variety of zip codes, predominantly in central and western North Carolina. Almost three-quarters of the patients resided in zip codes where the average income was less than the North Carolina median household income ($66,196).9 Additionally, 82 patients (32.3%) were uninsured or on Medicaid (eTable). These economically disadvantaged patient populations historically have had limited access to dermatologic care.4 One study showed that privately insured individuals were accepted as new patients by dermatologists 91% of the time compared to a 29.8% acceptance rate for publicly insured individuals.10 Uninsured and Medicaid patients also have to wait 34% longer for an appointment compared to individuals with Medicare or private insurance.2 Considering these patients may already be at an economic disadvantage when it comes to seeing and paying for dermatologic services, e-consults may reduce patient travel and appointment expenses while increasing access to specialty care. Based on a 2020 study, each e-consult generates an estimated savings of $80 out-of-pocket per patient per avoided in-person visit.11

In our study, the most common condition for an e-consult in both adult and pediatric patients was rash, which is consistent with prior e-consult studies.5,11 We found that most e-consult patients were not recommended for an in-person dermatology visit, and for those who were recommended to have an in-person visit, the wait time was reduced (Figure). These results corroborate that e-consults may be used as an important triage tool for determining whether a specialist appointment is indicated as well as a public health tool, as timely evaluation is associated with better dermatologic health care outcomes.3 However, the number of patients who did not present for an in-person appointment in our study may be overestimated, as 38 patients’ (21.6%) e-consults were conducted fewer than 90 days before our data collection. Although none of these patients had been seen in person, it is possible they requested an in-person visit after their medical records were reviewed for this study. Additionally, it is possible patients sought care from outside providers not documented in the EHR.

With regard to the payment model for the e-consult program, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist initially piloted the e-consult system through a partnership with the American Academy of Medical Colleges’ Project CORE: Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/health-care/project-core). Grant funding through Project CORE allowed both the referring PCP and the specialist completing the e-consult to each receive approximately 0.5 relative value units in payment for each consult completed. Based on early adoption successes, the institution has created additional internal funding to support the continued expansion of the e-consult system and is incentivized to continue funding, as proper utilization of e-consults improves patient access to timely specialist care, avoids no-shows or last-minute cancellations for specialist appointments, and decreases back-door access to specialist care through the emergency department and urgent care facilities.5 Although 0.5 relative value units is not equivalent compensation to an in-person office visit, our study showed that e-consults can be completed much more quickly and efficiently and do not utilize nursing staff or other office resources.

Conclusion

E-consults are an effective telehealth modality that can increase patients’ access to dermatologic specialty care.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Department of Medical Education and Department of Dermatology (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their contributions to this research study as well as the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their help extracting EHR data.

Dermatologic conditions affect approximately one-third of individuals in the United States.1,2 Nearly 1 in 4 physician office visits in the United States are for skin conditions, and less than one-third of these visits are with dermatologists. Although many of these patients may prefer to see a dermatologist for their concerns, they may not be able to access specialist care.3 The limited supply and urban-focused distribution of dermatologists along with reduced acceptance of state-funded insurance plans and long appointment wait times all pose considerable challenges to individuals seeking dermatologic care.2 Electronic consultations (e-consults) have emerged as a promising solution to overcoming these barriers while providing high-quality dermatologic care to a large diverse patient population.2,4 Although e-consults can be of service to all dermatology patients, this modality may be especially beneficial to underserved populations, such as the uninsured and Medicaid patients—groups that historically have experienced limited access to dermatology care due to the low reimbursement rates and high administrative burdens accompanying care delivery.4 This limited access leads to inequity in care, as timely access to dermatology is associated with improved diagnostic accuracy and disease outcomes.3 E-consult implementation can facilitate timely access for these underserved populations and bypass additional barriers to care such as lack of transportation or time off work. Prior e-consult studies have demonstrated relatively high numbers of Medicaid patients utilizing e-consult services.3,5

Although in-person visits remain the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, e-consults placed by primary care providers (PCPs) can improve access and help triage patients who require in-person dermatology visits.6 In this study, we conducted a retrospective chart review to characterize the e-consults requested of the dermatology department at a large tertiary care medical center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Methods

The electronic health record (EHR) of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) was screened for eligible patients from January 1, 2020, to May 31, 2021. Patients—both adult (aged ≥18 years) and pediatric (aged <18 years)—were included if they underwent a dermatology e-consult within this time frame. Provider notes in the medical records were reviewed to determine the nature of the lesion, how long the dermatologist took to complete the e-consult, whether an in-person appointment was recommended, and whether the patient was seen by dermatology within 90 days of the e-consult. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

For each e-consult, the PCP obtained clinical photographs of the lesion in question either through the EHR mobile application or by having patients upload their own photographs directly to their medical records. The referring PCP then completed a brief template regarding the patient’s clinical question and medical history and then sent the completed information to the consulting dermatologist’s EHR inbox. From there, the dermatologist could view the clinical question, documented photographs, and patient medical record to create a brief consult note with recommendations. The note was then sent back via EHR to the PCP to follow up with the patient. Patients were not charged for the e-consult.

Results

Two hundred fifty-four dermatology e-consults were requested by providers at the study center (eTable), which included 252 unique patients (2 patients had 2 separate e-consults regarding different clinical questions). The median time for completion of the e-consult—from submission of the PCP’s e-consult request to dermatologist completion—was 0.37 days. Fifty-six patients (22.0%) were recommended for an in-person appointment (Figure), 33 (58.9%) of whom ultimately scheduled the in-person appointment, and the median length of time between the completion of the e-consult and the in-person appointment was 16.5 days. The remaining 198 patients (78.0%) were not triaged to receive an in-person appointment following the e-consult,but 2 patients (8.7%) were ultimately seen in-person anyway via other referral pathways, with a median length of 33 days between e-consult completion and the in-person appointment. One hundred seventy-six patients (69.8%) avoided an in-person dermatology visit, although 38 (21.6%) of those patients were fewer than 90 days out from their e-consults at the time of data collection. The 254 e-consults included patients from 50 different zip codes, 49 (98.0%) of which were in North Carolina.

Comment

An e-consult is an asynchronous telehealth modality through which PCPs can request specialty evaluation to provide diagnostic and therapeutic guidance, facilitate PCP-specialist coordination of care, and increase access to specialty care with reduced wait times.7,8 Increased care access is especially important, as specialty referral can decrease overall health care expenditure; however, the demand for specialists often exceeds the availability.8 Our e-consult program drastically reduced the time from patients’ initial presentation at their PCP’s office to dermatologist recommendations for treatment or need for in-person dermatology follow-up.

In our analysis, patients were of different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and lived across a variety of zip codes, predominantly in central and western North Carolina. Almost three-quarters of the patients resided in zip codes where the average income was less than the North Carolina median household income ($66,196).9 Additionally, 82 patients (32.3%) were uninsured or on Medicaid (eTable). These economically disadvantaged patient populations historically have had limited access to dermatologic care.4 One study showed that privately insured individuals were accepted as new patients by dermatologists 91% of the time compared to a 29.8% acceptance rate for publicly insured individuals.10 Uninsured and Medicaid patients also have to wait 34% longer for an appointment compared to individuals with Medicare or private insurance.2 Considering these patients may already be at an economic disadvantage when it comes to seeing and paying for dermatologic services, e-consults may reduce patient travel and appointment expenses while increasing access to specialty care. Based on a 2020 study, each e-consult generates an estimated savings of $80 out-of-pocket per patient per avoided in-person visit.11

In our study, the most common condition for an e-consult in both adult and pediatric patients was rash, which is consistent with prior e-consult studies.5,11 We found that most e-consult patients were not recommended for an in-person dermatology visit, and for those who were recommended to have an in-person visit, the wait time was reduced (Figure). These results corroborate that e-consults may be used as an important triage tool for determining whether a specialist appointment is indicated as well as a public health tool, as timely evaluation is associated with better dermatologic health care outcomes.3 However, the number of patients who did not present for an in-person appointment in our study may be overestimated, as 38 patients’ (21.6%) e-consults were conducted fewer than 90 days before our data collection. Although none of these patients had been seen in person, it is possible they requested an in-person visit after their medical records were reviewed for this study. Additionally, it is possible patients sought care from outside providers not documented in the EHR.

With regard to the payment model for the e-consult program, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist initially piloted the e-consult system through a partnership with the American Academy of Medical Colleges’ Project CORE: Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/health-care/project-core). Grant funding through Project CORE allowed both the referring PCP and the specialist completing the e-consult to each receive approximately 0.5 relative value units in payment for each consult completed. Based on early adoption successes, the institution has created additional internal funding to support the continued expansion of the e-consult system and is incentivized to continue funding, as proper utilization of e-consults improves patient access to timely specialist care, avoids no-shows or last-minute cancellations for specialist appointments, and decreases back-door access to specialist care through the emergency department and urgent care facilities.5 Although 0.5 relative value units is not equivalent compensation to an in-person office visit, our study showed that e-consults can be completed much more quickly and efficiently and do not utilize nursing staff or other office resources.