User login

Inpatient Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Delphi Consensus Study

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 0.1% of the US population.1,2 Severe disease or HS flares can lead patients to seek care through the emergency department (ED), with some requiring inpatient admission. 3 Inpatient hospitalization of patients with HS has increased over the last 2 decades, and patients with HS utilize emergency and inpatient care more frequently than those with other dermatologic conditions.4,5 Minority patients and those of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to present to the ED for HS management due to limited access to care and other existing comorbid conditions. 4 In a 2022 study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the authors looked at hospital readmission rates of patients with HS compared with those with heart failure—both patient populations with chronic debilitating conditions. Results indicated that the hospital readmission rates for patients with HS surpassed those of patients with heart failure for that year, highlighting the need for improved inpatient management of HS.6

Patients with HS present to the ED with severe pain, fever, wound care, or the need for surgical intervention. The ED and inpatient hospital setting are locations in which physicians may not be as familiar with the diagnosis or treatment of HS, specifically flares or severe disease. 7 The inpatient care setting provides access to certain resources that can be challenging to obtain in the outpatient clinical setting, such as social workers and pain specialists, but also can prove challenging in obtaining other resources for HS management, such as advanced medical therapies. Given the increase in hospital- based care for HS and lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial. In our study, we sought to generate a collection of expert consensus statements providers can refer to when managing patients with HS in the inpatient setting.

Methods

The study team at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(M.N., R.P., L.C.S.) developed an initial set of consensus statements based on current published HS treatment guidelines,8,9 publications on management of inpatient HS,3 published supportive care guidelines for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, 10 and personal clinical experience in managing inpatient HS, which resulted in 50 statements organized into the following categories: overall care, wound care, genital care, pain management, infection control, medical management, surgical management, nutrition, and transitional care guidelines. This study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (IRB00084257).

Participant Recruitment—Dermatologists were identified for participation in the study based on membership in the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation or authorship of publications relevant to HS or inpatient dermatology. Dermatologists from larger academic institutions with HS specialty clinics and inpatient dermatology services also were identified. Participants were invited via email and could suggest other experts for inclusion. A total of 31 dermatologists were invited to participate in the study, with 26 agreeing to participate. All participating dermatologists were practicing in the United States.

Delphi Study—In the first round of the Delphi study, the participants were sent an online survey via REDCap in which they were asked to rank the appropriateness of each of the proposed 50 guideline statements on a scale of 1 (very inappropriate) to 9 (very appropriate). Participants also were able to provide commentary and feedback on each of the statements. Survey results were analyzed using the RAND/ UCLA Appropriateness Method.11 For each statement, the median rating for appropriateness, interpercentile range (IPR), IPR adjusted for symmetry, and disagreement index (DI) were calculated (DI=IPR/IPR adjusted for symmetry). The 30th and 70th percentiles were used in the DI calculation as the upper and lower limits, respectively. A median rating for appropriateness of 1.0 to 3.9 was considered “inappropriate,” 4.0 to 6.9 was considered “uncertain appropriateness,” and 7.0 to 9.0 was “appropriate.” A DI value greater than or equal to 1 indicated a lack of consensus regarding the appropriateness of the statement. Following each round, participants received a copy of their responses along with the group median rank of each statement. Statements that did not reach consensus in the first Delphi round were revised based on feedback received by the participants, and a second survey with 14 statements was sent via REDCap 2 weeks later. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method also was applied to this second Delphi round. After the second survey, participants received a copy of anonymized comments regarding the consensus statements and were allowed to provide additional final commentary to be included in the discussion of these recommendations.

Results

Twenty-six dermatologists completed the first-round survey, and 24 participants completed the second-round survey. All participants self-identified as having expertise in either HS (n=22 [85%]) or inpatient dermatology (n=17 [65%]), and 13 (50%) participants self-identified as experts in both HS and inpatient dermatology. All participants, except 1, were affiliated with an academic health system with inpatient dermatology services. The average length of time in practice as a dermatologist was 10 years (median, 9 years [range, 3–27 years]).

Of the 50 initial proposed consensus statements, 26 (52%) achieved consensus after the first round; 21 statements revealed DI calculations that did not achieve consensus. Two statements achieved consensus but received median ratings for appropriateness, indicating uncertain appropriateness; because of this, 1 statement was removed and 1 was revised based on participant feedback, resulting in 13 revised statements (eTable 1). Controversial topics in the consensus process included obtaining wound cultures and meaningful culture data interpretation, use of specific biologic medications in the inpatient setting, and use of intravenous ertapenem. Participant responses to these topics are discussed in detail below. Of these secondround statements, all achieved consensus. The final set of consensus statements can be found in eTable 2.

Comment

Our Delphi consensus study combined the expertise of both dermatologists who care for patients with HS and those with inpatient dermatology experience to produce a set of recommendations for the management of HS in the hospital care setting. A strength of this study is inclusion of many national leaders in both HS and inpatient dermatology, with some participants having developed the previously published HS treatment guidelines and others having participated in inpatient dermatology Delphi studies.8-10 The expertise is further strengthened by the geographically diverse institutional representation within the United States.

The final consensus recommendations included 40 statements covering a range of patient care issues, including use of appropriate inpatient subspecialists (care team), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition back to outpatient management (transitional care). These recommendations are meant to serve as a resource for providers to consider when taking care of inpatient HS flares, recognizing that the complexity and individual circumstances of each patient are unique.

Delphi Consensus Recommendations Compared to Prior Guidelines—Several recommendations in the current study align with the previously published North American clinical management guidelines for HS.8,9 Our recommendations agree with prior guidelines on the importance of disease staging and pain assessment using validated assessment tools as well as screening for HS comorbidities. There also is agreement in the potential benefit of involving pain specialists in the development of a comprehensive pain management plan. The inpatient care setting provides a unique opportunity to engage multiple specialists and collaborate on patient care in a timely manner. Our recommendations regarding surgical care also align with established guidelines in recommending incision and drainage as an acute bedside procedure best utilized for symptom relief in inflamed abscesses and relegating most other surgical management to the outpatient setting. Wound care recommendations also are similar, with our expert participants agreeing on individualizing dressing choices based on wound characteristics. A benefit of inpatient wound care is access to skilled nursing for dressing changes and potentially improved access to more sophisticated dressing materials. Our recommendations differ from the prior guidelines in our focus on severe HS, HS flares, and HS complications, which constitute the majority of inpatient disease management. We provide additional guidance on management of secondary infections, perianal fistulous disease, and importantly transitional care to optimize discharge planning.

Differing Opinions in Our Analysis—Despite the success of our Delphi consensus process, there were some differing opinions regarding certain aspects of inpatient HS management, which is to be expected given the lack of strong evidence-based research to support some of the recommended practices. There were differing opinions on the utility of wound culture data, with some participants feeling culture data could help with antibiotic susceptibility and resistance patterns, while others felt wound cultures represent bacterial colonization or biofilm formation.

Initial consensus statements in the first Delphi round were created for individual biologic medications but did not achieve consensus, and feedback on the use of biologics in the inpatient environment was mixed, largely due to logistic and insurance issues. Many participants felt biologic medication cost, difficulty obtaining inpatient reimbursement, health care resource utilization, and availability of biologics in different hospital systems prevented recommending the use of specific biologics during hospitalization. The one exception was in the case of a hospitalized patient who was already receiving infliximab for HS: there was consensus on ensuring the patient dosing was maximized, if appropriate, to 10 mg/kg.12 Ertapenem use also was controversial, with some participants using it as a bridge therapy to either outpatient biologic use or surgery, while others felt it was onerous and difficult to establish reliable access to secure intravenous administration and regular dosing once the patient left the inpatient setting.13 Others said they have experienced objections from infectious disease colleagues on the use of intravenous antibiotics, citing antibiotic stewardship concerns.

Patient Care in the Inpatient Setting—Prior literature suggests patients admitted as inpatients for HS tend to be of lower socioeconomic status and are admitted to larger urban teaching hospitals.14,15 Patients with lower socioeconomic status have increased difficulty accessing health care resources; therefore, inpatient admission serves as an opportunity to provide a holistic HS assessment and coordinate resources for chronic outpatient management.

Study Limitations—This Delphi consensus study has some limitations. The existing literature on inpatient management of HS is limited, challenging our ability to assess the extent to which these published recommendations are already being implemented. Additionally, the study included HS and inpatient dermatology experts from the United States, which means the recommendations may not be generalizable to other countries. Most participants practiced dermatology at large tertiary care academic medical centers, which may limit the ability to implement recommendations in all US inpatient care settings such as small community-based hospitals; however, many of the supportive care guidelines such as pain control, wound care, nutritional support, and social work should be achievable in most inpatient care settings.

Conclusion

Given the increase in inpatient and ED health care utilization for HS, there is an urgent need for expert consensus recommendations on inpatient management of this unique patient population, which requires complex multidisciplinary care. Our recommendations are a resource for providers to utilize and potentially improve the standard of care we provide these patients.

Acknowledgment—We thank the Wake Forest University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston- Salem, North Carolina) for providing statistical help.

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:990-998. doi:10.1111/bjd.19435

- Charrow A, Savage KT, Flood K, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa for the dermatologic hospitalist. Cutis. 2019;104:276-280.

- Anzaldi L, Perkins JA, Byrd AS, et al. Characterizing inpatient hospitalizations for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:510-513. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.019

- Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:609-614. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053

- Edigin E, Kaul S, Eseaton PO, et al. At 180 days hidradenitis suppurativa readmission rate is comparable to heart failure: analysis of the nationwide readmissions database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:188-192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.894

- Kirby JS, Miller JJ, Adams DR, et al. Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:937-944. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.691

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2019.02.067

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2020.02.066

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Burnand B, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method: User’s Manual. Rand; 2001.

- Oskardmay AN, Miles JA, Sayed CJ. Determining the optimal dose of infliximab for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:702-708. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.022

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard-Biehler H, Jais JP, et al. Efficacy of ertapenem in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study in a cohort of 30 consecutive patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:513-520. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv361

- Khanna R, Whang KA, Huang AH, et al. Inpatient burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: analysis of the 2016 National Inpatient Sample. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1150-1152. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2020.1773380

- Patel A, Patel A, Solanki D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: insights from the national inpatient sample (2008-2017) on contemporary trends in demographics, hospitalization rates, chronic comorbid conditions, and mortality. Cureus. 2022;14:E24755. doi:10.7759/cureus.24755

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 0.1% of the US population.1,2 Severe disease or HS flares can lead patients to seek care through the emergency department (ED), with some requiring inpatient admission. 3 Inpatient hospitalization of patients with HS has increased over the last 2 decades, and patients with HS utilize emergency and inpatient care more frequently than those with other dermatologic conditions.4,5 Minority patients and those of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to present to the ED for HS management due to limited access to care and other existing comorbid conditions. 4 In a 2022 study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the authors looked at hospital readmission rates of patients with HS compared with those with heart failure—both patient populations with chronic debilitating conditions. Results indicated that the hospital readmission rates for patients with HS surpassed those of patients with heart failure for that year, highlighting the need for improved inpatient management of HS.6

Patients with HS present to the ED with severe pain, fever, wound care, or the need for surgical intervention. The ED and inpatient hospital setting are locations in which physicians may not be as familiar with the diagnosis or treatment of HS, specifically flares or severe disease. 7 The inpatient care setting provides access to certain resources that can be challenging to obtain in the outpatient clinical setting, such as social workers and pain specialists, but also can prove challenging in obtaining other resources for HS management, such as advanced medical therapies. Given the increase in hospital- based care for HS and lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial. In our study, we sought to generate a collection of expert consensus statements providers can refer to when managing patients with HS in the inpatient setting.

Methods

The study team at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(M.N., R.P., L.C.S.) developed an initial set of consensus statements based on current published HS treatment guidelines,8,9 publications on management of inpatient HS,3 published supportive care guidelines for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, 10 and personal clinical experience in managing inpatient HS, which resulted in 50 statements organized into the following categories: overall care, wound care, genital care, pain management, infection control, medical management, surgical management, nutrition, and transitional care guidelines. This study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (IRB00084257).

Participant Recruitment—Dermatologists were identified for participation in the study based on membership in the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation or authorship of publications relevant to HS or inpatient dermatology. Dermatologists from larger academic institutions with HS specialty clinics and inpatient dermatology services also were identified. Participants were invited via email and could suggest other experts for inclusion. A total of 31 dermatologists were invited to participate in the study, with 26 agreeing to participate. All participating dermatologists were practicing in the United States.

Delphi Study—In the first round of the Delphi study, the participants were sent an online survey via REDCap in which they were asked to rank the appropriateness of each of the proposed 50 guideline statements on a scale of 1 (very inappropriate) to 9 (very appropriate). Participants also were able to provide commentary and feedback on each of the statements. Survey results were analyzed using the RAND/ UCLA Appropriateness Method.11 For each statement, the median rating for appropriateness, interpercentile range (IPR), IPR adjusted for symmetry, and disagreement index (DI) were calculated (DI=IPR/IPR adjusted for symmetry). The 30th and 70th percentiles were used in the DI calculation as the upper and lower limits, respectively. A median rating for appropriateness of 1.0 to 3.9 was considered “inappropriate,” 4.0 to 6.9 was considered “uncertain appropriateness,” and 7.0 to 9.0 was “appropriate.” A DI value greater than or equal to 1 indicated a lack of consensus regarding the appropriateness of the statement. Following each round, participants received a copy of their responses along with the group median rank of each statement. Statements that did not reach consensus in the first Delphi round were revised based on feedback received by the participants, and a second survey with 14 statements was sent via REDCap 2 weeks later. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method also was applied to this second Delphi round. After the second survey, participants received a copy of anonymized comments regarding the consensus statements and were allowed to provide additional final commentary to be included in the discussion of these recommendations.

Results

Twenty-six dermatologists completed the first-round survey, and 24 participants completed the second-round survey. All participants self-identified as having expertise in either HS (n=22 [85%]) or inpatient dermatology (n=17 [65%]), and 13 (50%) participants self-identified as experts in both HS and inpatient dermatology. All participants, except 1, were affiliated with an academic health system with inpatient dermatology services. The average length of time in practice as a dermatologist was 10 years (median, 9 years [range, 3–27 years]).

Of the 50 initial proposed consensus statements, 26 (52%) achieved consensus after the first round; 21 statements revealed DI calculations that did not achieve consensus. Two statements achieved consensus but received median ratings for appropriateness, indicating uncertain appropriateness; because of this, 1 statement was removed and 1 was revised based on participant feedback, resulting in 13 revised statements (eTable 1). Controversial topics in the consensus process included obtaining wound cultures and meaningful culture data interpretation, use of specific biologic medications in the inpatient setting, and use of intravenous ertapenem. Participant responses to these topics are discussed in detail below. Of these secondround statements, all achieved consensus. The final set of consensus statements can be found in eTable 2.

Comment

Our Delphi consensus study combined the expertise of both dermatologists who care for patients with HS and those with inpatient dermatology experience to produce a set of recommendations for the management of HS in the hospital care setting. A strength of this study is inclusion of many national leaders in both HS and inpatient dermatology, with some participants having developed the previously published HS treatment guidelines and others having participated in inpatient dermatology Delphi studies.8-10 The expertise is further strengthened by the geographically diverse institutional representation within the United States.

The final consensus recommendations included 40 statements covering a range of patient care issues, including use of appropriate inpatient subspecialists (care team), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition back to outpatient management (transitional care). These recommendations are meant to serve as a resource for providers to consider when taking care of inpatient HS flares, recognizing that the complexity and individual circumstances of each patient are unique.

Delphi Consensus Recommendations Compared to Prior Guidelines—Several recommendations in the current study align with the previously published North American clinical management guidelines for HS.8,9 Our recommendations agree with prior guidelines on the importance of disease staging and pain assessment using validated assessment tools as well as screening for HS comorbidities. There also is agreement in the potential benefit of involving pain specialists in the development of a comprehensive pain management plan. The inpatient care setting provides a unique opportunity to engage multiple specialists and collaborate on patient care in a timely manner. Our recommendations regarding surgical care also align with established guidelines in recommending incision and drainage as an acute bedside procedure best utilized for symptom relief in inflamed abscesses and relegating most other surgical management to the outpatient setting. Wound care recommendations also are similar, with our expert participants agreeing on individualizing dressing choices based on wound characteristics. A benefit of inpatient wound care is access to skilled nursing for dressing changes and potentially improved access to more sophisticated dressing materials. Our recommendations differ from the prior guidelines in our focus on severe HS, HS flares, and HS complications, which constitute the majority of inpatient disease management. We provide additional guidance on management of secondary infections, perianal fistulous disease, and importantly transitional care to optimize discharge planning.

Differing Opinions in Our Analysis—Despite the success of our Delphi consensus process, there were some differing opinions regarding certain aspects of inpatient HS management, which is to be expected given the lack of strong evidence-based research to support some of the recommended practices. There were differing opinions on the utility of wound culture data, with some participants feeling culture data could help with antibiotic susceptibility and resistance patterns, while others felt wound cultures represent bacterial colonization or biofilm formation.

Initial consensus statements in the first Delphi round were created for individual biologic medications but did not achieve consensus, and feedback on the use of biologics in the inpatient environment was mixed, largely due to logistic and insurance issues. Many participants felt biologic medication cost, difficulty obtaining inpatient reimbursement, health care resource utilization, and availability of biologics in different hospital systems prevented recommending the use of specific biologics during hospitalization. The one exception was in the case of a hospitalized patient who was already receiving infliximab for HS: there was consensus on ensuring the patient dosing was maximized, if appropriate, to 10 mg/kg.12 Ertapenem use also was controversial, with some participants using it as a bridge therapy to either outpatient biologic use or surgery, while others felt it was onerous and difficult to establish reliable access to secure intravenous administration and regular dosing once the patient left the inpatient setting.13 Others said they have experienced objections from infectious disease colleagues on the use of intravenous antibiotics, citing antibiotic stewardship concerns.

Patient Care in the Inpatient Setting—Prior literature suggests patients admitted as inpatients for HS tend to be of lower socioeconomic status and are admitted to larger urban teaching hospitals.14,15 Patients with lower socioeconomic status have increased difficulty accessing health care resources; therefore, inpatient admission serves as an opportunity to provide a holistic HS assessment and coordinate resources for chronic outpatient management.

Study Limitations—This Delphi consensus study has some limitations. The existing literature on inpatient management of HS is limited, challenging our ability to assess the extent to which these published recommendations are already being implemented. Additionally, the study included HS and inpatient dermatology experts from the United States, which means the recommendations may not be generalizable to other countries. Most participants practiced dermatology at large tertiary care academic medical centers, which may limit the ability to implement recommendations in all US inpatient care settings such as small community-based hospitals; however, many of the supportive care guidelines such as pain control, wound care, nutritional support, and social work should be achievable in most inpatient care settings.

Conclusion

Given the increase in inpatient and ED health care utilization for HS, there is an urgent need for expert consensus recommendations on inpatient management of this unique patient population, which requires complex multidisciplinary care. Our recommendations are a resource for providers to utilize and potentially improve the standard of care we provide these patients.

Acknowledgment—We thank the Wake Forest University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston- Salem, North Carolina) for providing statistical help.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 0.1% of the US population.1,2 Severe disease or HS flares can lead patients to seek care through the emergency department (ED), with some requiring inpatient admission. 3 Inpatient hospitalization of patients with HS has increased over the last 2 decades, and patients with HS utilize emergency and inpatient care more frequently than those with other dermatologic conditions.4,5 Minority patients and those of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to present to the ED for HS management due to limited access to care and other existing comorbid conditions. 4 In a 2022 study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the authors looked at hospital readmission rates of patients with HS compared with those with heart failure—both patient populations with chronic debilitating conditions. Results indicated that the hospital readmission rates for patients with HS surpassed those of patients with heart failure for that year, highlighting the need for improved inpatient management of HS.6

Patients with HS present to the ED with severe pain, fever, wound care, or the need for surgical intervention. The ED and inpatient hospital setting are locations in which physicians may not be as familiar with the diagnosis or treatment of HS, specifically flares or severe disease. 7 The inpatient care setting provides access to certain resources that can be challenging to obtain in the outpatient clinical setting, such as social workers and pain specialists, but also can prove challenging in obtaining other resources for HS management, such as advanced medical therapies. Given the increase in hospital- based care for HS and lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial. In our study, we sought to generate a collection of expert consensus statements providers can refer to when managing patients with HS in the inpatient setting.

Methods

The study team at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(M.N., R.P., L.C.S.) developed an initial set of consensus statements based on current published HS treatment guidelines,8,9 publications on management of inpatient HS,3 published supportive care guidelines for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, 10 and personal clinical experience in managing inpatient HS, which resulted in 50 statements organized into the following categories: overall care, wound care, genital care, pain management, infection control, medical management, surgical management, nutrition, and transitional care guidelines. This study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (IRB00084257).

Participant Recruitment—Dermatologists were identified for participation in the study based on membership in the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation or authorship of publications relevant to HS or inpatient dermatology. Dermatologists from larger academic institutions with HS specialty clinics and inpatient dermatology services also were identified. Participants were invited via email and could suggest other experts for inclusion. A total of 31 dermatologists were invited to participate in the study, with 26 agreeing to participate. All participating dermatologists were practicing in the United States.

Delphi Study—In the first round of the Delphi study, the participants were sent an online survey via REDCap in which they were asked to rank the appropriateness of each of the proposed 50 guideline statements on a scale of 1 (very inappropriate) to 9 (very appropriate). Participants also were able to provide commentary and feedback on each of the statements. Survey results were analyzed using the RAND/ UCLA Appropriateness Method.11 For each statement, the median rating for appropriateness, interpercentile range (IPR), IPR adjusted for symmetry, and disagreement index (DI) were calculated (DI=IPR/IPR adjusted for symmetry). The 30th and 70th percentiles were used in the DI calculation as the upper and lower limits, respectively. A median rating for appropriateness of 1.0 to 3.9 was considered “inappropriate,” 4.0 to 6.9 was considered “uncertain appropriateness,” and 7.0 to 9.0 was “appropriate.” A DI value greater than or equal to 1 indicated a lack of consensus regarding the appropriateness of the statement. Following each round, participants received a copy of their responses along with the group median rank of each statement. Statements that did not reach consensus in the first Delphi round were revised based on feedback received by the participants, and a second survey with 14 statements was sent via REDCap 2 weeks later. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method also was applied to this second Delphi round. After the second survey, participants received a copy of anonymized comments regarding the consensus statements and were allowed to provide additional final commentary to be included in the discussion of these recommendations.

Results

Twenty-six dermatologists completed the first-round survey, and 24 participants completed the second-round survey. All participants self-identified as having expertise in either HS (n=22 [85%]) or inpatient dermatology (n=17 [65%]), and 13 (50%) participants self-identified as experts in both HS and inpatient dermatology. All participants, except 1, were affiliated with an academic health system with inpatient dermatology services. The average length of time in practice as a dermatologist was 10 years (median, 9 years [range, 3–27 years]).

Of the 50 initial proposed consensus statements, 26 (52%) achieved consensus after the first round; 21 statements revealed DI calculations that did not achieve consensus. Two statements achieved consensus but received median ratings for appropriateness, indicating uncertain appropriateness; because of this, 1 statement was removed and 1 was revised based on participant feedback, resulting in 13 revised statements (eTable 1). Controversial topics in the consensus process included obtaining wound cultures and meaningful culture data interpretation, use of specific biologic medications in the inpatient setting, and use of intravenous ertapenem. Participant responses to these topics are discussed in detail below. Of these secondround statements, all achieved consensus. The final set of consensus statements can be found in eTable 2.

Comment

Our Delphi consensus study combined the expertise of both dermatologists who care for patients with HS and those with inpatient dermatology experience to produce a set of recommendations for the management of HS in the hospital care setting. A strength of this study is inclusion of many national leaders in both HS and inpatient dermatology, with some participants having developed the previously published HS treatment guidelines and others having participated in inpatient dermatology Delphi studies.8-10 The expertise is further strengthened by the geographically diverse institutional representation within the United States.

The final consensus recommendations included 40 statements covering a range of patient care issues, including use of appropriate inpatient subspecialists (care team), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition back to outpatient management (transitional care). These recommendations are meant to serve as a resource for providers to consider when taking care of inpatient HS flares, recognizing that the complexity and individual circumstances of each patient are unique.

Delphi Consensus Recommendations Compared to Prior Guidelines—Several recommendations in the current study align with the previously published North American clinical management guidelines for HS.8,9 Our recommendations agree with prior guidelines on the importance of disease staging and pain assessment using validated assessment tools as well as screening for HS comorbidities. There also is agreement in the potential benefit of involving pain specialists in the development of a comprehensive pain management plan. The inpatient care setting provides a unique opportunity to engage multiple specialists and collaborate on patient care in a timely manner. Our recommendations regarding surgical care also align with established guidelines in recommending incision and drainage as an acute bedside procedure best utilized for symptom relief in inflamed abscesses and relegating most other surgical management to the outpatient setting. Wound care recommendations also are similar, with our expert participants agreeing on individualizing dressing choices based on wound characteristics. A benefit of inpatient wound care is access to skilled nursing for dressing changes and potentially improved access to more sophisticated dressing materials. Our recommendations differ from the prior guidelines in our focus on severe HS, HS flares, and HS complications, which constitute the majority of inpatient disease management. We provide additional guidance on management of secondary infections, perianal fistulous disease, and importantly transitional care to optimize discharge planning.

Differing Opinions in Our Analysis—Despite the success of our Delphi consensus process, there were some differing opinions regarding certain aspects of inpatient HS management, which is to be expected given the lack of strong evidence-based research to support some of the recommended practices. There were differing opinions on the utility of wound culture data, with some participants feeling culture data could help with antibiotic susceptibility and resistance patterns, while others felt wound cultures represent bacterial colonization or biofilm formation.

Initial consensus statements in the first Delphi round were created for individual biologic medications but did not achieve consensus, and feedback on the use of biologics in the inpatient environment was mixed, largely due to logistic and insurance issues. Many participants felt biologic medication cost, difficulty obtaining inpatient reimbursement, health care resource utilization, and availability of biologics in different hospital systems prevented recommending the use of specific biologics during hospitalization. The one exception was in the case of a hospitalized patient who was already receiving infliximab for HS: there was consensus on ensuring the patient dosing was maximized, if appropriate, to 10 mg/kg.12 Ertapenem use also was controversial, with some participants using it as a bridge therapy to either outpatient biologic use or surgery, while others felt it was onerous and difficult to establish reliable access to secure intravenous administration and regular dosing once the patient left the inpatient setting.13 Others said they have experienced objections from infectious disease colleagues on the use of intravenous antibiotics, citing antibiotic stewardship concerns.

Patient Care in the Inpatient Setting—Prior literature suggests patients admitted as inpatients for HS tend to be of lower socioeconomic status and are admitted to larger urban teaching hospitals.14,15 Patients with lower socioeconomic status have increased difficulty accessing health care resources; therefore, inpatient admission serves as an opportunity to provide a holistic HS assessment and coordinate resources for chronic outpatient management.

Study Limitations—This Delphi consensus study has some limitations. The existing literature on inpatient management of HS is limited, challenging our ability to assess the extent to which these published recommendations are already being implemented. Additionally, the study included HS and inpatient dermatology experts from the United States, which means the recommendations may not be generalizable to other countries. Most participants practiced dermatology at large tertiary care academic medical centers, which may limit the ability to implement recommendations in all US inpatient care settings such as small community-based hospitals; however, many of the supportive care guidelines such as pain control, wound care, nutritional support, and social work should be achievable in most inpatient care settings.

Conclusion

Given the increase in inpatient and ED health care utilization for HS, there is an urgent need for expert consensus recommendations on inpatient management of this unique patient population, which requires complex multidisciplinary care. Our recommendations are a resource for providers to utilize and potentially improve the standard of care we provide these patients.

Acknowledgment—We thank the Wake Forest University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston- Salem, North Carolina) for providing statistical help.

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:990-998. doi:10.1111/bjd.19435

- Charrow A, Savage KT, Flood K, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa for the dermatologic hospitalist. Cutis. 2019;104:276-280.

- Anzaldi L, Perkins JA, Byrd AS, et al. Characterizing inpatient hospitalizations for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:510-513. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.019

- Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:609-614. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053

- Edigin E, Kaul S, Eseaton PO, et al. At 180 days hidradenitis suppurativa readmission rate is comparable to heart failure: analysis of the nationwide readmissions database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:188-192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.894

- Kirby JS, Miller JJ, Adams DR, et al. Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:937-944. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.691

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2019.02.067

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2020.02.066

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Burnand B, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method: User’s Manual. Rand; 2001.

- Oskardmay AN, Miles JA, Sayed CJ. Determining the optimal dose of infliximab for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:702-708. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.022

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard-Biehler H, Jais JP, et al. Efficacy of ertapenem in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study in a cohort of 30 consecutive patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:513-520. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv361

- Khanna R, Whang KA, Huang AH, et al. Inpatient burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: analysis of the 2016 National Inpatient Sample. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1150-1152. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2020.1773380

- Patel A, Patel A, Solanki D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: insights from the national inpatient sample (2008-2017) on contemporary trends in demographics, hospitalization rates, chronic comorbid conditions, and mortality. Cureus. 2022;14:E24755. doi:10.7759/cureus.24755

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:990-998. doi:10.1111/bjd.19435

- Charrow A, Savage KT, Flood K, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa for the dermatologic hospitalist. Cutis. 2019;104:276-280.

- Anzaldi L, Perkins JA, Byrd AS, et al. Characterizing inpatient hospitalizations for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:510-513. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.019

- Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:609-614. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053

- Edigin E, Kaul S, Eseaton PO, et al. At 180 days hidradenitis suppurativa readmission rate is comparable to heart failure: analysis of the nationwide readmissions database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:188-192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.894

- Kirby JS, Miller JJ, Adams DR, et al. Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:937-944. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.691

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2019.02.067

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2020.02.066

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Burnand B, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method: User’s Manual. Rand; 2001.

- Oskardmay AN, Miles JA, Sayed CJ. Determining the optimal dose of infliximab for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:702-708. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.022

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard-Biehler H, Jais JP, et al. Efficacy of ertapenem in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study in a cohort of 30 consecutive patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:513-520. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv361

- Khanna R, Whang KA, Huang AH, et al. Inpatient burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: analysis of the 2016 National Inpatient Sample. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1150-1152. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2020.1773380

- Patel A, Patel A, Solanki D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: insights from the national inpatient sample (2008-2017) on contemporary trends in demographics, hospitalization rates, chronic comorbid conditions, and mortality. Cureus. 2022;14:E24755. doi:10.7759/cureus.24755

Practice Points

- Given the increase in hospital-based care for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and the lack of widespread inpatient access to dermatology and HS experts, consensus recommendations for management of HS in the acute hospital setting would be beneficial.

- Our Delphi study yielded 40 statements that reached consensus covering a range of patient care issues (eg, appropriate inpatient subspecialists [care team]), supportive care measures (wound care, pain control, genital care), disease-oriented treatment (medical management, surgical management), inpatient complications (infection control, nutrition), and successful transition to outpatient management (transitional care).

- These recommendations serve as an important resource for providers caring for inpatients with HS and represent a successful collaboration between inpatient dermatology and HS experts.

White Concretions on the Hair Shaft

The Diagnosis: White Piedra

A fungal culture demonstrated a filamentous fungus that was identified as Trichosporon inkin via DNA sequencing, which confirmed the diagnosis of white piedra (WP).

Piedra refers to a group of fungal infections presenting as gritty nodules adherent to the hair shaft.1 It is further categorized into black piedra, which occurs more commonly in tropical climates and is caused by Piedraia hortae, and WP, which occurs in tropical and temperate climates and is caused by the Trichosporon genus.1-3 Among the Trichosporon genus, clinical manifestations have varied based on species; for example, T inkin commonly causes genital WP, Trichosporon ovoides commonly causes scalp WP, and Trichosporon asahii and Trichosporon mucoides have been described to cause systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.1,4 Scalp WP most commonly occurs in children and young adults, and females are at greater risk than males.1,2,5,6

Clinically, WP presents with pale irregular nodules along the hair shaft that are not fluorescent on Wood lamp examination.1,6,7 Nodules are soft and easily detached from the hair shaft, unlike the hard, tightly adherent nodules seen in black piedra.1,7 White piedra affects hair in a variety of areas including the scalp, beard, eyebrows, eyelashes, axillae, and genitals.1,7 Affected hair may become brittle and break at points of invasion.1 Alternatively, WP may resemble tinea capitis with scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia, though tinea typically affects the base of the hair shaft.1 Immunocompromised patients can develop disseminated WP, and cases of progressive pneumonia, lung abscess, peritonitis, vascular access infection, and endocarditis have been reported.2

Diagnosis of WP is made through a combination of clinical findings and culture of infected hair. Potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrates sleevelike concretions formed of masses of septate hyphae with dense zones of arthrospores and blastospores.1,2 Culture on Sabouraud agar demonstrates creamy colonies that develop a dull, gray, wrinkled surface.1,2 Differential diagnosis includes pediculosis; however, the concretions of WP are circumferential around the hair shaft on microscopy.1 Notably, a case of concomitant WP and pediculosis has been reported.8 In cases of potential pediculosis resistant to therapy, consider hair casts, which are asymptomatic, white, cylindrical concretions that encircle the hair without adherence and can therefore be differentiated from pediculosis via dermoscopy.9 Because this phenomenon is more commonly observed in preadolescent girls, it is hypothesized that scalp inflammation due to traction from hairstyles or atopic dermatitis contributes to the development of hair casts.9,10 Thus, when a potassium hydroxide mount is equivocal for nits and dermoscopy demonstrates concretions that completely encircle the hair shaft, it is important to perform a microbiologic culture to rule out piedra of the hair or scalp. Other differential diagnoses include tinea capitis, black piedra, trichobacteriosis, and hair shaft abnormalities.

Transmission of WP is thought to result from a combination of poor hygiene; humidity due to climate; personal care practices such as habitually tying wet hair, applying hair oils and conditioners, or covering hair according to social customs; and close contact with an infected individual.1,3,6 Long scalp hair potentially correlates with increased risk.1,6 Finally, WP has been described in animals and has been isolated from soil, vegetable matter, and water.3,10

Treatment of WP generally involves removal of infected hair, antifungal agents, and improved hygienic habits to avoid relapses. The American Academy of Dermatology’s Guidelines/Outcomes Committee recommends complete removal of infected hair; however, patients may desire hair-preserving treatments.11 Kiken et al1 reported success with the combination of an oral azole antifungal agent for 3 weeks to 1 month and an antifungal shampoo for 2 to 3 months. The authors proposed that oral medication eliminates scalp carriage while antifungal shampoo eliminates hair shaft concretions.1

1. Kiken DA, Sekaran A, Antaya RJ, et al. White piedra in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:956-961.

2. Bonifaz A, Gómez-Daza F, Paredes V, et al. Tinea versicolor, tinea nigra, white piedra, and black piedra. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:140-145.

3. Shivaprakash MR, Singh G, Gupta P, et al. Extensive white piedra of the scalp caused by Trichosporon inkin: a case report and review of literature. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:481-486.

4. Goldberg LJ, Wise EM, Miller NS. White piedra caused by Trichosporon inkin: a report of two cases in a northern climate. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:866-868.

5. Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

6. Fischman O, Bezerra FC, Francisco EC, et al. Trichosporon inkin: an uncommon agent of scalp white piedra. report of four cases in Brazilian children. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:85-89.

7. Pontes ZB, Ramos AL, Lima Ede O, et al. Clinical and mycological study of scalp white piedra in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:747-750.

8. Marques SA, Richini-Pereira VB, Camargo RM. White piedra and pediculosis capitis in the same patient. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:786-787.

9. Gnarra M, Saraceni P, Rossi A, et al. Challenging diagnosis of peripillous sheaths. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:E112-E113.

10. França K, Villa RT, Silva IR, et al. Hair casts or pseudonits. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:121-122.

11. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: piedra. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:122-124.

The Diagnosis: White Piedra

A fungal culture demonstrated a filamentous fungus that was identified as Trichosporon inkin via DNA sequencing, which confirmed the diagnosis of white piedra (WP).

Piedra refers to a group of fungal infections presenting as gritty nodules adherent to the hair shaft.1 It is further categorized into black piedra, which occurs more commonly in tropical climates and is caused by Piedraia hortae, and WP, which occurs in tropical and temperate climates and is caused by the Trichosporon genus.1-3 Among the Trichosporon genus, clinical manifestations have varied based on species; for example, T inkin commonly causes genital WP, Trichosporon ovoides commonly causes scalp WP, and Trichosporon asahii and Trichosporon mucoides have been described to cause systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.1,4 Scalp WP most commonly occurs in children and young adults, and females are at greater risk than males.1,2,5,6

Clinically, WP presents with pale irregular nodules along the hair shaft that are not fluorescent on Wood lamp examination.1,6,7 Nodules are soft and easily detached from the hair shaft, unlike the hard, tightly adherent nodules seen in black piedra.1,7 White piedra affects hair in a variety of areas including the scalp, beard, eyebrows, eyelashes, axillae, and genitals.1,7 Affected hair may become brittle and break at points of invasion.1 Alternatively, WP may resemble tinea capitis with scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia, though tinea typically affects the base of the hair shaft.1 Immunocompromised patients can develop disseminated WP, and cases of progressive pneumonia, lung abscess, peritonitis, vascular access infection, and endocarditis have been reported.2

Diagnosis of WP is made through a combination of clinical findings and culture of infected hair. Potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrates sleevelike concretions formed of masses of septate hyphae with dense zones of arthrospores and blastospores.1,2 Culture on Sabouraud agar demonstrates creamy colonies that develop a dull, gray, wrinkled surface.1,2 Differential diagnosis includes pediculosis; however, the concretions of WP are circumferential around the hair shaft on microscopy.1 Notably, a case of concomitant WP and pediculosis has been reported.8 In cases of potential pediculosis resistant to therapy, consider hair casts, which are asymptomatic, white, cylindrical concretions that encircle the hair without adherence and can therefore be differentiated from pediculosis via dermoscopy.9 Because this phenomenon is more commonly observed in preadolescent girls, it is hypothesized that scalp inflammation due to traction from hairstyles or atopic dermatitis contributes to the development of hair casts.9,10 Thus, when a potassium hydroxide mount is equivocal for nits and dermoscopy demonstrates concretions that completely encircle the hair shaft, it is important to perform a microbiologic culture to rule out piedra of the hair or scalp. Other differential diagnoses include tinea capitis, black piedra, trichobacteriosis, and hair shaft abnormalities.

Transmission of WP is thought to result from a combination of poor hygiene; humidity due to climate; personal care practices such as habitually tying wet hair, applying hair oils and conditioners, or covering hair according to social customs; and close contact with an infected individual.1,3,6 Long scalp hair potentially correlates with increased risk.1,6 Finally, WP has been described in animals and has been isolated from soil, vegetable matter, and water.3,10

Treatment of WP generally involves removal of infected hair, antifungal agents, and improved hygienic habits to avoid relapses. The American Academy of Dermatology’s Guidelines/Outcomes Committee recommends complete removal of infected hair; however, patients may desire hair-preserving treatments.11 Kiken et al1 reported success with the combination of an oral azole antifungal agent for 3 weeks to 1 month and an antifungal shampoo for 2 to 3 months. The authors proposed that oral medication eliminates scalp carriage while antifungal shampoo eliminates hair shaft concretions.1

The Diagnosis: White Piedra

A fungal culture demonstrated a filamentous fungus that was identified as Trichosporon inkin via DNA sequencing, which confirmed the diagnosis of white piedra (WP).

Piedra refers to a group of fungal infections presenting as gritty nodules adherent to the hair shaft.1 It is further categorized into black piedra, which occurs more commonly in tropical climates and is caused by Piedraia hortae, and WP, which occurs in tropical and temperate climates and is caused by the Trichosporon genus.1-3 Among the Trichosporon genus, clinical manifestations have varied based on species; for example, T inkin commonly causes genital WP, Trichosporon ovoides commonly causes scalp WP, and Trichosporon asahii and Trichosporon mucoides have been described to cause systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.1,4 Scalp WP most commonly occurs in children and young adults, and females are at greater risk than males.1,2,5,6

Clinically, WP presents with pale irregular nodules along the hair shaft that are not fluorescent on Wood lamp examination.1,6,7 Nodules are soft and easily detached from the hair shaft, unlike the hard, tightly adherent nodules seen in black piedra.1,7 White piedra affects hair in a variety of areas including the scalp, beard, eyebrows, eyelashes, axillae, and genitals.1,7 Affected hair may become brittle and break at points of invasion.1 Alternatively, WP may resemble tinea capitis with scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia, though tinea typically affects the base of the hair shaft.1 Immunocompromised patients can develop disseminated WP, and cases of progressive pneumonia, lung abscess, peritonitis, vascular access infection, and endocarditis have been reported.2

Diagnosis of WP is made through a combination of clinical findings and culture of infected hair. Potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrates sleevelike concretions formed of masses of septate hyphae with dense zones of arthrospores and blastospores.1,2 Culture on Sabouraud agar demonstrates creamy colonies that develop a dull, gray, wrinkled surface.1,2 Differential diagnosis includes pediculosis; however, the concretions of WP are circumferential around the hair shaft on microscopy.1 Notably, a case of concomitant WP and pediculosis has been reported.8 In cases of potential pediculosis resistant to therapy, consider hair casts, which are asymptomatic, white, cylindrical concretions that encircle the hair without adherence and can therefore be differentiated from pediculosis via dermoscopy.9 Because this phenomenon is more commonly observed in preadolescent girls, it is hypothesized that scalp inflammation due to traction from hairstyles or atopic dermatitis contributes to the development of hair casts.9,10 Thus, when a potassium hydroxide mount is equivocal for nits and dermoscopy demonstrates concretions that completely encircle the hair shaft, it is important to perform a microbiologic culture to rule out piedra of the hair or scalp. Other differential diagnoses include tinea capitis, black piedra, trichobacteriosis, and hair shaft abnormalities.

Transmission of WP is thought to result from a combination of poor hygiene; humidity due to climate; personal care practices such as habitually tying wet hair, applying hair oils and conditioners, or covering hair according to social customs; and close contact with an infected individual.1,3,6 Long scalp hair potentially correlates with increased risk.1,6 Finally, WP has been described in animals and has been isolated from soil, vegetable matter, and water.3,10

Treatment of WP generally involves removal of infected hair, antifungal agents, and improved hygienic habits to avoid relapses. The American Academy of Dermatology’s Guidelines/Outcomes Committee recommends complete removal of infected hair; however, patients may desire hair-preserving treatments.11 Kiken et al1 reported success with the combination of an oral azole antifungal agent for 3 weeks to 1 month and an antifungal shampoo for 2 to 3 months. The authors proposed that oral medication eliminates scalp carriage while antifungal shampoo eliminates hair shaft concretions.1

1. Kiken DA, Sekaran A, Antaya RJ, et al. White piedra in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:956-961.

2. Bonifaz A, Gómez-Daza F, Paredes V, et al. Tinea versicolor, tinea nigra, white piedra, and black piedra. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:140-145.

3. Shivaprakash MR, Singh G, Gupta P, et al. Extensive white piedra of the scalp caused by Trichosporon inkin: a case report and review of literature. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:481-486.

4. Goldberg LJ, Wise EM, Miller NS. White piedra caused by Trichosporon inkin: a report of two cases in a northern climate. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:866-868.

5. Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

6. Fischman O, Bezerra FC, Francisco EC, et al. Trichosporon inkin: an uncommon agent of scalp white piedra. report of four cases in Brazilian children. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:85-89.

7. Pontes ZB, Ramos AL, Lima Ede O, et al. Clinical and mycological study of scalp white piedra in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:747-750.

8. Marques SA, Richini-Pereira VB, Camargo RM. White piedra and pediculosis capitis in the same patient. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:786-787.

9. Gnarra M, Saraceni P, Rossi A, et al. Challenging diagnosis of peripillous sheaths. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:E112-E113.

10. França K, Villa RT, Silva IR, et al. Hair casts or pseudonits. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:121-122.

11. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: piedra. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:122-124.

1. Kiken DA, Sekaran A, Antaya RJ, et al. White piedra in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:956-961.

2. Bonifaz A, Gómez-Daza F, Paredes V, et al. Tinea versicolor, tinea nigra, white piedra, and black piedra. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:140-145.

3. Shivaprakash MR, Singh G, Gupta P, et al. Extensive white piedra of the scalp caused by Trichosporon inkin: a case report and review of literature. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:481-486.

4. Goldberg LJ, Wise EM, Miller NS. White piedra caused by Trichosporon inkin: a report of two cases in a northern climate. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:866-868.

5. Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

6. Fischman O, Bezerra FC, Francisco EC, et al. Trichosporon inkin: an uncommon agent of scalp white piedra. report of four cases in Brazilian children. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:85-89.

7. Pontes ZB, Ramos AL, Lima Ede O, et al. Clinical and mycological study of scalp white piedra in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:747-750.

8. Marques SA, Richini-Pereira VB, Camargo RM. White piedra and pediculosis capitis in the same patient. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:786-787.

9. Gnarra M, Saraceni P, Rossi A, et al. Challenging diagnosis of peripillous sheaths. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:E112-E113.

10. França K, Villa RT, Silva IR, et al. Hair casts or pseudonits. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:121-122.

11. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: piedra. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:122-124.

A 35-year-old woman presented with possible nits on the hair of 1 year’s duration. She was previously evaluated by several outside medical providers and was unsuccessfully treated with topical and systemic medications for pediculosis. She reported sporadic scalp pruritus but denied hair loss, breakage, close contacts with similar symptoms, or recent travel outside the United States. She was otherwise healthy and was not taking any medications. Physical examination revealed small 1- to 2-mm, generalized, somewhat detachable, white concretions randomly distributed on the hair shafts. No broken hairs were observed. The eyebrows, eyelash hairs, and surrounding skin were normal. Potassium hydroxide mount was equivocal for nits.

Update on Calciphylaxis Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management

Calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a painful skin condition classically seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), particularly those on chronic dialysis.1,2 It also has increasingly been reported in patients with normal renal function and calcium and phosphate homeostasis.3,4 Effective diagnosis and management of calciphylaxis remains challenging for physicians.2,5 The condition is characterized by tissue ischemia caused by calcification of cutaneous arteriolar vessels. As a result, calciphylaxis is associated with high mortality rates, ranging from 60% to 80%.5,6 Excruciating pain and nonhealing ulcers often lead to recurrent hospitalizations and infectious complications,7 and poor nutritional status, chronic pain, depression, and insomnia can further complicate recovery and lead to poor quality of life.8

We provide an update on calciphylaxis etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. We also highlight some challenges faced in managing this potentially fatal condition.

Epidemiology

Calciphylaxis is considered a rare dermatosis with an estimated annual incidence of 1% to 4% in ESRD patients on dialysis. Recent data suggest that incidence of calciphylaxis is rising,5,7,9 which may stem from an increased use of calcium-based phosphate binders, an actual rise in disease incidence, and/or increased recognition of the disease.5 It is difficult to estimate the exact disease burden of calciphylaxis because the diagnostic criteria are not well defined, often leading to missed or delayed diagnosis.3,10 Furthermore, there is no centralized registry for calciphylaxis cases.3

Etiology and Pathogenesis

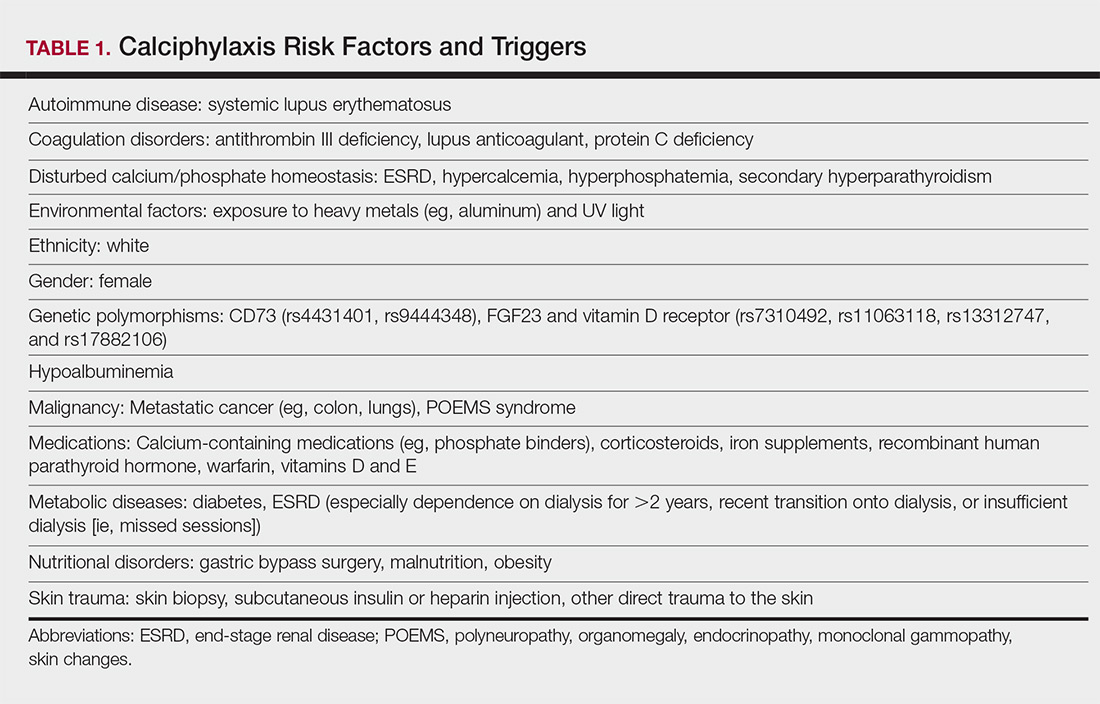

Calciphylaxis is thought to have a multifactorial etiology with the exact cause or trigger unknown.7 A long list of risk factors and triggers is associated with the condition (Table 1). Calciphylaxis primarily affects small arteries (40–600 μm in diameter) that become calcified due to an imbalance between inhibitors and promoters of calcification.2,11 Fetuin-A and matrix Gla protein inhibit vascular calcification and are downregulated in calciphylaxis.12,13 Dysfunctional calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone regulatory pathways provide an increased substrate for the process of calcification, which causes endothelial damage and microthrombosis, resulting in tissue ischemia and infarction.14,15 Notably, there is growing interest in the role of vitamin K in the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis. Vitamin K inhibits vascular calcification, possibly by increasing the circulating levels of carboxylated matrix Gla protein.16

Clinical Features

Calciphylaxis is most commonly seen on the legs, abdomen, and buttocks.2 Patients with ESRD commonly develop proximal lesions affecting adipose-rich sites and have a poor prognosis. Distal lesions are more common in patients with nonuremic calciphylaxis, and mortality rates are lower in this population.2

Early lesions present as painful skin nodules or indurated plaques that often are rock-hard or firm to palpation with overlying mottling or a livedoid pattern (Figure, A). Early lesions progress from livedo reticularis to livedo racemosa and then to retiform purpura (Figure, B). Purpuric lesions later evolve into black eschars (Figure, C), then to necrotic, ulcerated, malodorous plaques or nodules in later stages of the disease (Figure, D). Lesions also may develop a gangrenous sclerotic appearance.2,5

Although most patients with calciphylaxis have ESRD, nonuremic patients also can develop the disease. Those with calciphylaxis who do not have renal dysfunction frequently have other risk factors for the disease and often report another notable health problem in the weeks or months prior to presentation.4 More than half of patients with calciphylaxis become bedridden or require use of a wheelchair.17 Pain is characteristically severe throughout the course of the disease; it may even precede the appearance of the skin lesions.18 Because the pain is associated with ischemia, it tends to be relatively refractory to treatment with opioids. Rare extracutaneous vascular calcifications may lead to visual impairment, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, and myopathy.5,9,19,20

Diagnosis

Considering the high morbidity and mortality associated with calciphylaxis, it is important to provide accurate and timely diagnosis; however, there currently are no validated diagnostic criteria for calciphylaxis. Careful correlation of clinical and histologic findings is required. Calciphylaxis biopsies have demonstrated medial calcification and proliferation of the intima of small- to medium-sized arteries.21 Lobular and septal panniculitis and extravascular soft-tissue calcification, particularly stippled calcification of the eccrine sweat glands, also has been seen.2,22 Special calcium stains (eg, von Kossa, Alizarin red) increase the sensitivity of biopsy by highlighting subtle areas of intravascular and extravascular calcification.5,23 Sufficient sampling of subcutaneous tissue and specimen evaluation by an experienced dermatopathologist are necessary to ensure proper interpretation of the histologic findings.

Despite these measures, skin biopsies may be nondiagnostic or falsely negative; therefore, when there is high clinical suspicion, it may be appropriate to move forward with a presumptive diagnosis of calciphylaxis even if the histologic findings are nondiagnostic.1,9,24 It also is worth noting that localized progression and ulceration may occur following skin biopsy, such that biopsy may even be contraindicated in certain cases (eg, penile calciphylaxis).

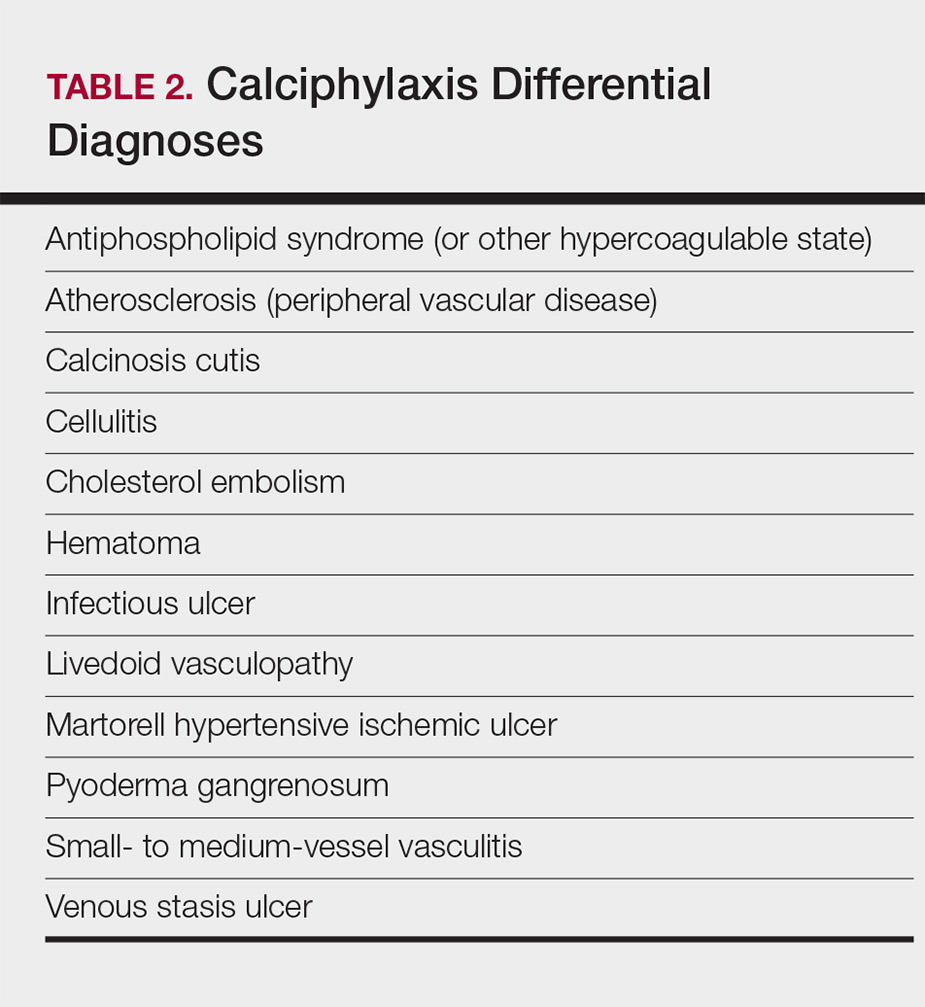

Standard laboratory workup for calciphylaxis includes evaluation for associated risk factors as well as exclusion of other conditions in the differential diagnosis (Table 2). Blood tests to evaluate for risk factors include liver and renal function tests, a complete metabolic panel, parathyroid hormone level, and serum albumin level.5 Elevated calcium and phosphate levels may signal disturbed calcium and phosphate homeostasis but are neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis.25 Complete blood cell count, blood cultures, thorough hypercoagulability workup (including but not limited to antiphospholipid antibodies, proteins C and S, factor V Leiden, antithrombin III, homocysteine, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation, and cryoglobulins), rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and antinuclear antibody testing may be relevant to help identify contributing factors or mimickers of calciphylaxis.5 Various imaging modalities also have been used to evaluate for the presence of soft-tissue calcification in areas of suspected calciphylaxis, including radiography, mammography, computed tomography, ultrasonography, nuclear bone scintigraphy, and spectroscopy.2,26,27 Unfortunately, there currently is no standardized reproducible imaging modality for reliable diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Ultimately, histologic and radiographic findings should always be interpreted in the context of relevant clinical findings.2,9

Prevention

Reduction of the net calcium phosphorus product may help reduce the risk of calciphylaxis in ESRD patients, which can be accomplished by using non–calcium-phosphate binders, adequate dialysis, and restricting use of vitamin D and vitamin K antagonists.2,5 There are limited data regarding the benefits of using bisphosphonates and cinacalcet in ESRD patients on dialysis to prevent calciphylaxis.28,29

Management

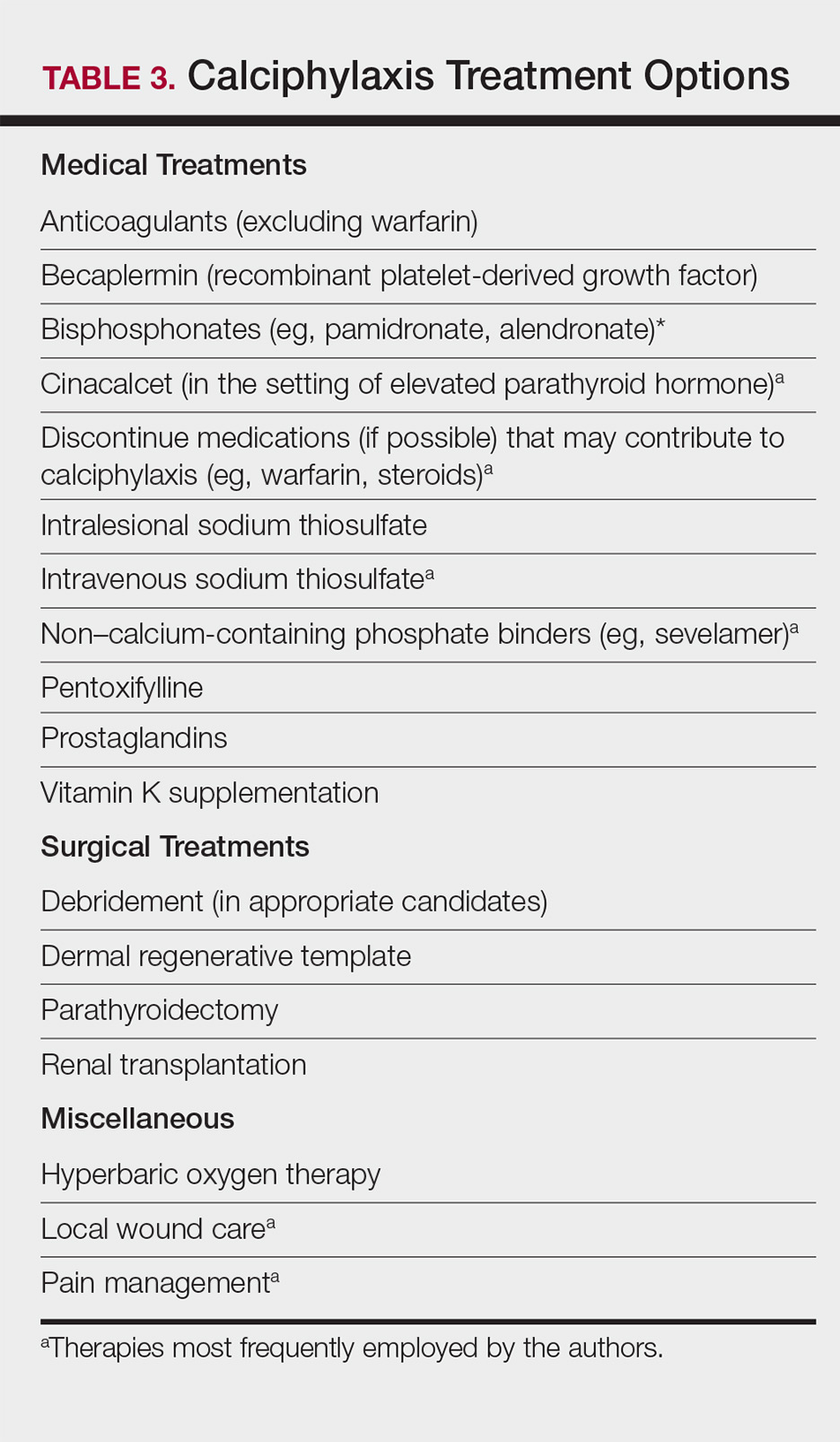

Management of calciphylaxis is multifactorial. Besides dermatology and nephrology, specialists in pain management, wound care, plastic surgery, and nutrition are critical partners in management.1,5,9,30 Nephrologists can help optimize calcium and phosphate balance and ensure adequate dialysis. Pain specialists can aid in creating aggressive multiagent pain regimens that target the neuropathic/ischemic and physical aspects of calciphylaxis pain. When appropriate, nutrition specialists can help establish high-protein, low-phosphorus diets, and wound specialists can provide access to advanced wound dressings and adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Plastic surgeons can provide conservative debridement procedures in a subset of patients, usually those with distal stable disease.

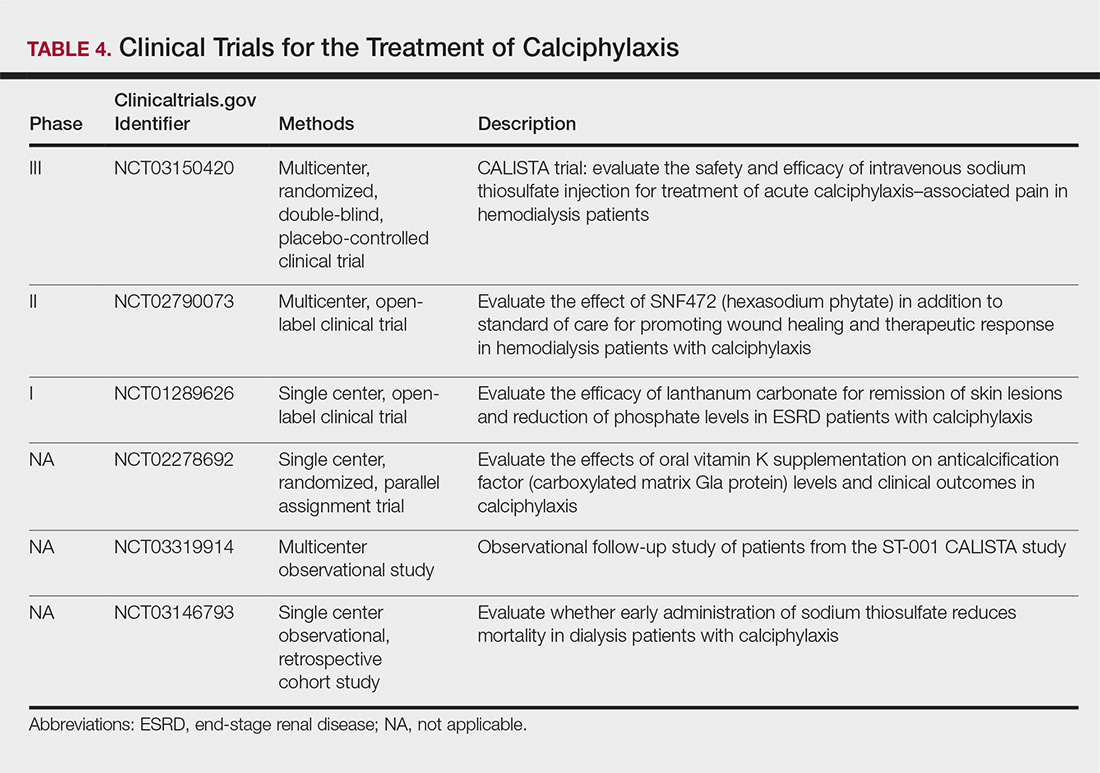

The limited understanding of the etiopathogenesis of calciphylaxis and the lack of data on its management are reflected in the limited treatment options for the disease (Table 3).2,5,9 There are no formal algorithms for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Therapeutic trials are scarce, and most of the current treatment recommendations are based on small retrospective reports or case series. Sodium thiosulfate has been the most widely used treatment option since 2004, when its use in calciphylaxis was first reported.31 Sodium thiosulfate chelates calcium and is thought to have antioxidant and vasodilatory properties.32 There are a few promising clinical trials and large-scale studies (Table 4) that aim to evaluate the efficacy of existing treatments (eg, sodium thiosulfate) as well as novel treatment options such as lanthanum carbonate, SNF472 (hexasodium phytate), and vitamin K.33-36

Prognosis

Calciphylaxis is a potentially fatal condition with a poor prognosis and a median survival rate of approximately 1 year following the appearance of skin lesions.37-39 Patients with proximal lesions and those on peritoneal dialysis (as opposed to hemodialysis) have a worse prognosis.40 Mortality rates are estimated to be 30% at 6 months, 50% at 12 months, and 80% at 2 years, with sepsis secondary to infection of cutaneous ulcers being the leading cause of death.37-39 The impact of calciphylaxis on patient quality of life and activities of daily living is severe.8,17

Future Directions

Multi-institution cohort studies and collaborative registries are needed to provide updated information related to the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, morbidity, and mortality associated with calciphylaxis and to help formulate evidence-based diagnostic criteria. Radiographic and histologic studies, as well as other tools for early and accurate diagnosis of calciphylaxis, should be studied for feasibility, accuracy, and reproducibility. The incidence of nonuremic calciphylaxis points toward pathogenic pathways besides those based on the bone-mineral axis. Basic science research directed at improving understanding of the pathophysiology of calciphylaxis would be helpful in devising new treatment strategies targeting these pathways. Establishment of a collaborative, multi-institutional calciphylaxis working group would enable experts to formulate therapeutic guidelines based on current evidence. Such a group could facilitate initiation of large prospective studies to establish the efficacy of existing and new treatment modalities for calciphylaxis. A working group within the Society for Dermatology Hospitalists has been tasked with addressing these issues and is currently establishing a multicenter calciphylaxis database.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146.

- Nigwekar SU, Thadhani RI, Brandenburg VM. Calciphylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1704-1714.