User login

Psychotherapy Telemental Health Center and Regional Pilot

Within VHA, telemental health (TMH) refers to behavioral health services that are provided remotely, using secure communication technologies, to veterans who are separated by distance from their mental health providers.1 Telemental health sometimes involves video teleconferencing (VTC) technology, where a veteran (or group of veterans) in one location and a provider in a different location are able to communicate in real time through a computer monitor or television screen.2 In the VHA, TMH visits are typically conducted from a central location (such as a medical center hospital) to a community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC), but pilot projects have also tested VTC in homes as well.1,3,4

In addition to providing timely access to behavioral health services in rural or underserved locations, TMH eliminates travel that may be disruptive or costly and allows mental health providers to consult with or provide supervision to one another. Telemental health can be used to make diagnoses, manage care, perform checkups, and provide long-term, follow-up care. Other uses for TMH include clinical assessment, individual and group psychotherapy, psycho-educational interventions, cognitive testing, and general psychiatric care.1,5,6 More recently, TMH has been used to provide evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) to individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health diagnoses.6,7 Such care may be particularly advantageous for veterans with PTSD, because traveling can be a burden for them or a trigger for PTSD symptoms.

Although interactive video technology is becoming widely available, its use is limited in health care systems due to lack of knowledge, education, logistical guidance, and technical training. The authors have conducted EBPs using VTC across VISN 22 in both office-to-office and office-to-home modalities and are providing EBPs using VTC to CBOCs in other VISNs across the western U.S. This article addresses these issues, outlining the necessary steps required to establish a TMH clinic and to share the successes of the EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot used at VISN 22.

Telemental Health

Telemental health is an effective alternative to in-person treatment and is well regarded by both mental health providers and veterans. Overall, mental health providers believe it can help reduce the stigma associated with traditional mental health care and ease transportation-related issues for veterans. Telemental health allows access to care for veterans living in rural or remote areas in addition to those who are incarcerated or are otherwise unable to attend visits at primary VA facilities.2,8-10 In an assessment of TMH services in 40 CBOCs across VISN 16, most CBOC mental health providers found it to be an acceptable alternative to face-to-face care, recognize the value of TMH, and endorse a willingness to use and expand TMH programs within their clinics.11

Veterans who participated in TMH via VTC have expressed satisfaction with the decreased travel time and expenses, fewer interactions with crowds, and fewer parking problems.12 Several studies suggested that veterans preferred TMH to in-person contact due to more rapid access to care and specialists who would otherwise be unavailable at remote locations.5,10 Similarly, veterans who avoid in-person mental health care were more open to remote therapy for many of the reasons listed earlier. Studies suggest that veterans from both rural and urban locations are generally receptive to receiving mental health services via TMH.5,10

Several studies have found that TMH services may have advantages over standard in-person care. These advantages include decreasing transportation costs, travel time, and time missed at work and increasing system coverage area.13 Overall, both veterans and providers reported similar satisfaction between VTC and in-person sessions and, in some cases, prefer VTC interactions due to a sense of “easing into” intense therapies or having a “therapeutic distance” as treatment begins.12

Utility

Previous studies have shown that TMH can be used successfully to provide psychopharmacologic treatment to veterans who have major depressive disorder or schizophrenia, among other psychiatric disorders.5,8,14 Recent studies have focused on the feasibility of providing EBPs via TMH, particularly for the treatment of PTSD.12,15 Studies have shown that TMH services via VTC can be used successfully to provide cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and prolonged exposure therapy (PE).16-21 In these studies, both PE and CPT delivered via TMH were found to be as efficacious as in-person formats. Furthermore, TMH services were successfully used in individual and group sessions.

Research has emphasized the benefits of TMH for veterans who are uncomfortable in crowds, waiting rooms, or hospital lobbies.7,12,18 For patients with PTSD who are initially limited by fears related to driving, TMH can facilitate access to care. Veterans with PTSD often avoid reminders of trauma (ie, uniforms, evidence of physical injury, artwork, photographs related to war), which can often be found at the larger VAMCs. These veterans may find mental health care services in their homes or at local CBOCs more appealing.7,12,18

Implementation

Prior to the implementation of telehealth services, many CBOC providers would refer veterans in need of specialty care to the nearest VAMC, which were sometimes many hours away.1 In response to travel and access concerns, the VA has implemented various telehealth modalities, including TMH.

In 2008, about 230,000 veterans received mental health services via real-time clinical VTC at 300 VA CBOCs, and about 40,000 veterans enrolled in the In-Home Telehealth program.22 By 2011, > 380,000 veterans used clinic-based telehealth services and about 100,000 veterans used the in-home program.1 Between 2006 and 2008, the 98,000 veterans who used TMH modalities had fewer hospital admissions compared with those who did not; overall, the need for hospital services decreased by about 25% for those using TMH services.23

Although research suggests that TMH is an effective treatment modality, it does have limitations. A recent study noted several visual and audio difficulties that can emerge, including pixilation, “tracer” images with movement, low resolution, “frozen” or “choppy” images, delays in sound, echoes, or “mechanical sounding” voices.12 In some cases, physical details, such as crying, sniffling, or fidgeting, could not be clearly observed.12 Overall, these unforeseen issues can impact the ability to give and receive care through TMH modalities. Proper procedures need to be developed and implemented for each site.

Getting Started

Using TMH to provide mental health care at other VHA facilities requires planning and preparation. Logistics, such as preparation of the room and equipment, should be considered. Similarly, veteran and provider convenience must be considered.2,11 Before starting TMH at any VA facility, professionals working with the audiovisual technology and providing TMH care must complete necessary VA Talent Management System courses and obtain copies of certificates to assure they have met the appropriate training criteria. Providers must be credentialed to provide TMH services, including the telehealth curriculum offered by VA Employee Educational Services.2,24 An appropriate memorandum of understanding (MOU) must be created, and credentialing and privileging must also be acquired.

In addition to provider training, an information technology representative who can administer technical support as needed must be selected for both the provider and remote locations. Technologic complications can make TMH implementation much more challenging.12 As such, it is important to assure that both the veteran and the provider have the necessary TMH equipment. The selected communication device must be compatible with the technology requirements at the provider and remote facilities.12

In addition to designated technical support, the VISN TMH coordinator needs to have point-of-contact information for those who can assist with each site’s telehealth services and address the demand for EBP for PTSD or other desired services. After this information has been obtained, relationships must be developed and maintained with local leadership at each site, associated telehealth coordinators, and evidence-based therapy coordinators.

After contact has been established with remote facilities and the demand for services has been determined, there are several agreements and procedures to put in place before starting TMH services. An initial step is to develop a MOU agreement between the VISN TMH center and remote

sites that allows providers’ credentials and privileges to be shared. Also, it is important to establish a service agreement that outlines the procedures for staff at the remote site. This agreement includes checking in veterans, setting up the TMH rooms, transferring homework to VISN TMH providers, and connecting with the VISN TMH provider. In addition to service agreements, emergency procedures must be in place to ensure the safety of the veterans and the staff.24

After these agreements have been completed, the VISN TMH providers will have to complete request forms to obtain access to the Computerized Patient Record System at the remote facilities, which then must be approved by the Information Security Officer at that site. This is separate from the request at the provider’s site.12 It is essential to have points of contact for questions regarding this process. In order to facilitate referrals for TMH, electronic interfacility consult requests must be developed. Local staff need to collaborate with VISN TMH staff to ensure that the consult addresses the referral facilities need to meet the appropriate requirements.

Before the initiation of TMH services, each TMH provider has to establish clinics for scheduling appointments and obtaining workload credit. Program support assistants at the provider and remote sites must work together to ensure clinics are established correctly. This collaboration is essential for coding of visits and clinic mapping. After the clinics are “built,” appointment times will be set up based on the availability of the provider, support staff, and rooms at the remote site for the TMH session.

Once a consult is initiated, the VISN TMH EBP coordinator will review the consult and the veteran’s chart to ensure initial inclusion/exclusion criteria are met before accepting or canceling the consult. If the consult is accepted, a VISN TMH provider is assigned to the case and contacts the veteran to discuss the referral and (if the veteran is appropriate and interested) initiate services at the closest CBOC or at home. The VISN TMH regional center staff enter the appointment time for the veteran at both facility sites. The VISN TMH provider also coordinates with the CBOC staff to ensure that the veteran is checked in to the appointment and is provided with any questionnaires and necessary homework.

During the first session, the provider obtains consent from the veteran to engage in TMH services, conducts an assessment, and establishes rapport. The provider works with the veteran to develop a treatment plan for PTSD or other mental health diagnosis that will include the type of EBP. At the end of the first session, the next appointment is scheduled, and treatment materials are either mailed to the veteran or given to him or her onsite. After completing EBP, the VISN TMH center works with the referring provider to find follow-up services for the veteran.

The various steps necessary to begin an interfacility TMH clinic are summarized in Table 1.

Provider Training

Despite strong evidence of success, many providers remained skeptical about the efficacy of TMH. One study indicated that several providers in VISN 16 rarely used the established TMH programs because they were not familiar with them and applied TMH only for medication checks and consults.11 This skepticism was present in providers preparing to offer TMH as well as in providers referring veterans for TMH services. However, once providers better understood the TMH programs and had more experience using them, they were significantly more likely to use TMH for initial evaluations and ongoing psychotherapy. For these reasons, proper training and educational opportunities for practicing providers are vital to TMH implementation.9,11

To be proficient, providers need to become familiar with various TMH applications.10 Health care networks implementing TMH must ensure that their providers are well trained and prepared to give and receive proper consultation and support. Providers must also acquire several skills and familiarize themselves with available tools.9 In educating providers on the process and use of TMH, the authors suggest the following steps for TMH application:

- Learn new ways to chart in multiple systems and know how to troubleshoot during connectivity issues.

- Have an established administrative support collaborator at outpatient clinics to fax and exchange veteran homework.12

- The TMH clinic culture must be embedded where the veteran is being served in order to allow for a more realistic therapeutic feel. This type of clinic setting will allow for referrals at the veteran site and the availability to coordinate emergency procedures in the remote clinic.

Clinical Issues

Ongoing clinical issues need to be addressed continuously. Initially, referrals may be plentiful but not always appropriate. It is important to have an understanding with referring providers and remote sites about what constitutes a “good referral” as well as alternate referral options. It is imperative to outline inclusion and exclusion criteria that are clear and concise for referring providers. It is often helpful to revisit these criteria with potential referral sources after initiating services.

With the ability to provide inhome services, it is important to identify specific inclusion/exclusion criteria. Recommendations are based on research and clinical applications for exclusions, which are available on the Office of Technology Services website. These include imminent suicidality or homicidality, serious personality disorder or problematic character traits, acute substance disorders, psychotic disorders, and bipolar disorder. It is important to use sound clinical judgment, because the usual safeguards present in a remote clinic are not available for inhome services. Emergency planning is one of the most important aspects of the in-home TMH health services that are provided. The information for the emergency plan is obtained prior to initiation of services.

Emergency Plans

Each remote clinic that provides services to veterans must have an emergency plan that details procedures, phone numbers, and resources in case of medical and psychological emergencies as well as natural disasters. The VISN TMH provider will need to have a copy of the emergency plan as well as a list of contacts in case of an emergency during a TMH session.

It is recommended that TMH providers have several ways to contact key staff who can assist during an emergency. Usually the clinical coordinator and telehealth technician are the first responders to be alerted by the TMH provider during an emergency. They will then institute the remote clinic’s emergency protocol. Discussing these procedures and reviewing them with staff regularly is advisable, as key contacts may change.

In a psychological emergency, the VISN TMH provider may assist in implementing emergency procedures until a clinical counterpart at the remote site can be alerted. In the authors’ experience, VISN TMH providers have successfully de-escalated and diffused potentially emergent situations by maintaining constant realtime communication with veterans and staff by using VTC as well as interoffice communication. By offering assistance to veterans and staff during challenging situations, the VISN TMH provider will not only decrease concerns of veterans, but oftentimes integrate themselves into the treatment team of the remote clinic. The role of a VISN TMH provider can be isolative, with minimal contact with remote clinic staff, so it is important to increase visibility among staff at a remote site by communication with them even when there is not an emergency.

Treatment protocols may be determined by either administrative or clinical factors. With certain TMH interventions, the rooms used for veterans may be available for only certain periods, which may or may not fit with treatment protocols. For example, if a room is available for only an hour but a treatment protocol session is for 90 minutes, then another time slot needs to be found or a different treatment considered and offered. Although it is not ideal to have treatment protocols determined by scheduling factors, the reality of shared space at remote sites requires flexibility.

Sharing Materials and Homework Another clinical issue that is often overlooked is how to implement specific treatment protocols that entail the exchange of materials between VISN TMH providers and veterans. If materials will need to be exchanged between provider and veteran, a plan will have to be in place to facilitate this. The service agreement addresses these details, but remote staff may not always be aware of the details.

If a TMH provider opts to use faxes to send materials between a veteran and a provider, a desktop faxing program is recommended so veteran privacy is not compromised. Often, providers will wait to begin sessions until after they have received materials, but this may result in a delayed

session. One solution TMH providers can implement is mailing the materials and questionnaires to veterans before the session with clear instructions to complete them beforehand. Once the veteran arrives for the TMH session, she or he will verbally respond to the questionnaire and treatment materials. This will add time to a session but minimizes potential delays. Many of the clinical VTC units have movable cameras, so veterans can tilt the camera to show providers the forms and questionnaires.

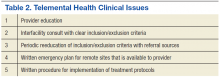

The various steps necessary to address TMH clinical issues are summarized in Table 2.

VISIN 22 Pilot Project

The VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot, based at the VA San Diego Healthcare System, was tasked with developing and providing TMH EBP services for PTSD across VISN 22 and adjacent West Coast VISNs. In addition to creating standardized procedures, troubleshooting guides were established to assist other programs with implementation. The primary focus was to increase access to EBPs for veterans with PTSD in areas where there was either no available trained providers or delays for specific services. The program established 16 clinics as well as in-home

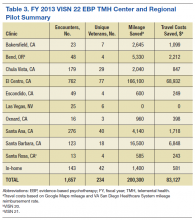

services in VISN 22, VISN 21, and VISN 20. In fiscal year (FY) 2013, the VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot provided 1,657 EBP encounters via TMH to 234 unique veterans with PTSD (Table 3).

The pilot project collected data to evaluate program effectiveness. The data were de-identified before being sent to the VA Central Office (VACO) TMH program manager. The following items were collected for the pilot: (1) clinical information; (2) consent to engage in treatment and telehealth; (3) release of information to share de-identified data to VACO for program monitoring; (4) demographic form; (5) Beck Depression Inventory-II (every other week); (6) PTSD Checklist (every other week); (7) World Health Organization Quality of Life (sessions 1, 7, final); (8) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (sessions 3, 7, final); (9) satisfaction survey (final); (10) mileage not driven by veterans who receive TMH services; (11) travel pay saved by VA; (12) no-show rates; and (13) veteran, TMH provider, and referral provider satisfaction.

The growth in number of encounters and number of unique veterans has increased steadily from the first quarter of FY14 through the second quarter of FY15 (Figure 1).

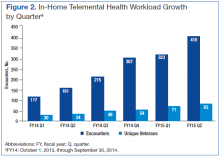

In January 2013, in-home TMH services were piloted. Although occasional technical difficulties occurred, 143 EBP encounters via TMH were provided to 42 unique veterans in 2013. The service has continued to expand, and in the first half of FY14, services were provided to 64 unique veterans for a total of 278 encounters, saving veterans 3,220 travel miles and saving the VA $1,336 in travel reimbursement. In-home TMH services will continue to expand as more providers in a variety of programs are being trained by the San Diego staff on how to provide these services to veterans in their homes. In addition to decreasing mileage and travel pay, the no-show rates are lower for TMH appointments in general (averaged 8%-10% vs facility no-show rate average of 13.5%) and with the use of inhome TMH, no-show rates were kept to 2%. The growth in the number of in-home encounters and the number of unique veterans has also increased steadily from the first quarter of FY14 thru the second quarter of FY15 (Figure 2).

In-Home TMH Services

The VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot often requests to have an in-person meeting with a veteran before starting TMH services in order to complete a waiver to download the software used by the VA for real-time video in-home services, a Release of Information for a Primary Support Person form, and an emergency plan.

It is also recommended that information about the veteran’s Internet connection, type of computer, type of software, presence of a camera and speakers, e-mail address, and access to secure messaging are obtained. During the initial contact with a veteran, the provider will discuss the rules and requirements to ensure HIPAA compliance. The veteran will need to have a private area for the call (not a restaurant, car, or other place where Wi-Fi is offered). Even with these discussions, some veterans will initiate services from a public place or a room in their home where family members will enter and exit frequently.

Although not required, it is recommended to have the veteran identify a primary support person and complete a release form to allow the TMH provider to contact that person in an emergency. The support person may be a person in the home (adult family member or caregiver) or someone nearby (neighbor, friend, or family member) who can contact emergency services if needed. After the necessary information is gathered and the veteran agrees to the conditions of participation, a test call will be completed. The TMH provider is often the person to conduct this call, but if available, a telehealth technician or facility telehealth coordinator may assist. The TMH provider may help the veteran download the appropriate software that is sent from the VA Scheduler software. The veteran initiates the call with the provider. Once the connection is made, the session may begin. Sites that are currently conducting in-home services have provided guides to veterans and newer TMH providers to outline the necessary steps for initiating services.

It is recommended that any provider interested in providing in-home TMH services use the Office of Technological Services help desk to assist in troubleshooting difficulties with connectivity. Challenges have included the software used for in-home TMH, periodic Internet outages, and compatibility issues.

Veteran Satisfaction

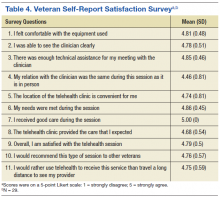

Veteran satisfaction was measured through a self-report satisfaction survey. The survey included 12 questions assessing overall experience in using TMH services. Eleven of the 12 questions included a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree); the last question was openended for additional comments.

A summary of the survey response of the initial 29 veterans who received TMH services suggested the following: (1) Veterans felt comfortable with using the TMH equipment and were able to see their clinician clearly; (2) Technical assistance was sufficient; (3) During the TMH session, they related to the provider as if it were a face-to-face meeting and that their needs were met; and (4) Veterans reported extremely high satisfaction with TMH and would refer TMH care to other veterans. Veterans found clinic locations very convenient and preferred the TMH modality of mental health services delivery to the alternative of travelling a long distance to see their provider (Table 4).

Written comments and recommendations from veterans supported the survey results. Most reported that they saved time and the convenience of the clinic allowed them to receive the treatment they need without interfering with their work schedule. However, some veterans still experienced trouble with travel to the remote clinic. Others felt their experience was different from the one they expected or they had a good experience via TMH but preferred face-to-face care.

Conclusion

The VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot have established the infrastructure of interfacility clinics to use EBPs for the treatment of PTSD. Also, the center has provided consultation and guidance to facilities interested in developing their own TMH programs. The TMH Center now plans to expand mental health services and include medication management and EBP services for non-PTSD psychiatric diagnoses. The established infrastructure will allow providers from one facility to cover the mental health service needs of other facilities when there are absences or gaps due to leave or delays/challenges in hiring in rural locations. Finally, TMH offers the potential to offer after-hours services to veterans in other time zones during providers’ regular tours of duty.

Several other TMH programs are now expanding services into veterans’ homes. There are several sites within the VHA that have piloted this TMH modality and developed guidelines and recommendations for further expansion. Currently VACO is encouraging all VHA facilities to increase in-home telehealth services, and the Office of Telehealth Services provides details on implementation. Interested parties are encouraged to routinely visit the VACO website for updated information.

Developing and implementing a new TMH program can be an arduous task, but the program has great potential to provide veteran-centered care. As TMH sessions progress, the provider and veteran become less aware of the camera and software and more aware of the therapeutic process. Challenges and delays in implementation are to be expected—these can occur frequently during the development and implementation stages of a TMH program. Maintaining consistent communication with staff at remote sites is essential for the success of any program.

As the VHA focuses on veterancentered care, TMH services will improve access to providers with specific, needed expertise. The authors hope these experiences can facilitate the continued growth of TMH and assuage any concerns a facility or provider may have about this modality of care. Delivery of TMH care can be challenging, but the ability to provide these services to veterans at times and locations convenient to them makes these challenges worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hauser wishes to thank Cathy, Anika, Jirina, Katia, and Max Hauser, and Alba Pillwein for their continued support. In memory of Beverly Ostroski.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. What is telehealth? U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.telehealth.va.gov. Update May 13, 2014. Accessed April 30, 2015.

2. Morland LA, Greene CJ, Rosen C, Mauldin PD, Frueh CB. Issues in the design of a randomized noninferiority clinical trial of telemental health psychotherapy for rural combat veterans with PTSD. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(6):513-522.

3. Strachan M, Gros DF, Ruggiero KJ, Lejuez CW, Acierno R. An integrated approach to delivering exposure-based treatment for symptoms of PTSD and depression in OIF/OEF veterans: preliminary findings. Behav Ther. 2012;43(3):560-569.

4. Yuen EK, Gros DF, Price M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of home-based telehealth versus in-person prolonged exposure for combat-related PTSD in veterans: preliminary results. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(6):500-512.

5. Ruskin PE, Reed S, Kumar R, et al. Reliability and acceptability of psychiatric diagnosis via telecommunication and audiovisual technology. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(8):1086-1088.

6. Gros DF, Morland LA, Greene CJ, et al. Delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy via video telehealth. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2013;35(4):506-521.

7. Backhaus A, Agha Z, Maglione ML, et al. Videoconferencing psychotherapy: a systematic review. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(2):111-131.

8. Egede LE, Frueh CB, Richardson LK, et al. Rationale and design: telepsychology service delivery for depressed elderly veterans. Trials. 2009;10:22.

9. Frueh BC, Deitsch SE, Santos AB, et al. Procedural and methodological issues in telepsychiatry research and program development. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(12):1522-1527.

10. Grubaugh AL, Cain GD, Elhai JD, Patrick SL, Frueh BC. Attitudes toward medical and mental health care delivered via telehealth applications among rural and urban primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(2):166-170.

11. Jameson JP, Farmer MS, Head KJ, Fortney J, Teal CR. VA community mental health service providers’ utilization of and attitudes towards telemental health care: the gatekeeper’s perspective. J Rural Health. 2011;27(4):425-432.

12. Thorp SR, Fidler J, Moreno L, Floto E, Agha Z. Lessons learned from studies of psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder via video teleconferencing. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(2):197-199.

13. Gros DF, Yoder M, Tuerk PW, Lozano BE, Acierno R. Exposure therapy for PTSD delivered to veterans via telehealth: predictors of treatment completion and outcome and comparison to treatment delivered in person. Behav Ther. 2011;42(2):276-283.

14. Zarate CA Jr, Weinstock L, Cukor P, et al. Applicability of telemedicine for assessing patients with schizophrenia: acceptance and reliability. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(1):22-25.

15. Jones AM, Shealy KM, Reid-Quiñones K, et al. Guidelines for establishing a telemental health program to provide evidence-based therapy for trauma-exposed children and families. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(4):398-409.

16. Frueh BC, Monnier J, Grubaugh AL, Elhai JD, Yim E, Knapp R. Therapist adherence and competence with manualized cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD delivered via videoconferencing technology. Behav Modif. 2007;31(6):856-866.

17. Morland LA, Hynes AK, Mackintosh MA, Resick PA, Chard KM. Group cognitive processing therapy delivered to veterans via telehealth: a pilot cohort. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(4):465-469.

18. Tuerk PW, Yoder M, Ruggiero KJ, Gros DF, Acierno R. A pilot study of prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder delivered via telehealth technology. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1):116-123.

19. Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Kimbrell TA, et al. Telemedicine- based collaborative care for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):58-67.

20. Germain V, Marchand A, Bouchard S, Drouin MS, Guay S. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy administered by videoconference for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(1):42-53.

21. Morland LA, Mackintosh M, Greene CJ, et al. Cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder delivered to rural veterans via telemental health: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(5):470-476.

22. Tuerk PW, Fortney J, Bosworth HB, et al. Toward the development of national telehealth services: the role of Veterans Health Administration and future directions for research. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(1):115-117.

23. Godleski L, Darkins A, Peters J. Outcomes of 98,609 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs patients enrolled in telemental health services, 2006-2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(4):383-385.

24. Strachan M, Gros DF, Yuen E, Ruggiero KJ, Foa EB, Acierno R. Home-based telehealth to deliver evidence-based psychotherapy in veterans with PTSD. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(2):402-409.

Within VHA, telemental health (TMH) refers to behavioral health services that are provided remotely, using secure communication technologies, to veterans who are separated by distance from their mental health providers.1 Telemental health sometimes involves video teleconferencing (VTC) technology, where a veteran (or group of veterans) in one location and a provider in a different location are able to communicate in real time through a computer monitor or television screen.2 In the VHA, TMH visits are typically conducted from a central location (such as a medical center hospital) to a community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC), but pilot projects have also tested VTC in homes as well.1,3,4

In addition to providing timely access to behavioral health services in rural or underserved locations, TMH eliminates travel that may be disruptive or costly and allows mental health providers to consult with or provide supervision to one another. Telemental health can be used to make diagnoses, manage care, perform checkups, and provide long-term, follow-up care. Other uses for TMH include clinical assessment, individual and group psychotherapy, psycho-educational interventions, cognitive testing, and general psychiatric care.1,5,6 More recently, TMH has been used to provide evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) to individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health diagnoses.6,7 Such care may be particularly advantageous for veterans with PTSD, because traveling can be a burden for them or a trigger for PTSD symptoms.

Although interactive video technology is becoming widely available, its use is limited in health care systems due to lack of knowledge, education, logistical guidance, and technical training. The authors have conducted EBPs using VTC across VISN 22 in both office-to-office and office-to-home modalities and are providing EBPs using VTC to CBOCs in other VISNs across the western U.S. This article addresses these issues, outlining the necessary steps required to establish a TMH clinic and to share the successes of the EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot used at VISN 22.

Telemental Health

Telemental health is an effective alternative to in-person treatment and is well regarded by both mental health providers and veterans. Overall, mental health providers believe it can help reduce the stigma associated with traditional mental health care and ease transportation-related issues for veterans. Telemental health allows access to care for veterans living in rural or remote areas in addition to those who are incarcerated or are otherwise unable to attend visits at primary VA facilities.2,8-10 In an assessment of TMH services in 40 CBOCs across VISN 16, most CBOC mental health providers found it to be an acceptable alternative to face-to-face care, recognize the value of TMH, and endorse a willingness to use and expand TMH programs within their clinics.11

Veterans who participated in TMH via VTC have expressed satisfaction with the decreased travel time and expenses, fewer interactions with crowds, and fewer parking problems.12 Several studies suggested that veterans preferred TMH to in-person contact due to more rapid access to care and specialists who would otherwise be unavailable at remote locations.5,10 Similarly, veterans who avoid in-person mental health care were more open to remote therapy for many of the reasons listed earlier. Studies suggest that veterans from both rural and urban locations are generally receptive to receiving mental health services via TMH.5,10

Several studies have found that TMH services may have advantages over standard in-person care. These advantages include decreasing transportation costs, travel time, and time missed at work and increasing system coverage area.13 Overall, both veterans and providers reported similar satisfaction between VTC and in-person sessions and, in some cases, prefer VTC interactions due to a sense of “easing into” intense therapies or having a “therapeutic distance” as treatment begins.12

Utility

Previous studies have shown that TMH can be used successfully to provide psychopharmacologic treatment to veterans who have major depressive disorder or schizophrenia, among other psychiatric disorders.5,8,14 Recent studies have focused on the feasibility of providing EBPs via TMH, particularly for the treatment of PTSD.12,15 Studies have shown that TMH services via VTC can be used successfully to provide cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and prolonged exposure therapy (PE).16-21 In these studies, both PE and CPT delivered via TMH were found to be as efficacious as in-person formats. Furthermore, TMH services were successfully used in individual and group sessions.

Research has emphasized the benefits of TMH for veterans who are uncomfortable in crowds, waiting rooms, or hospital lobbies.7,12,18 For patients with PTSD who are initially limited by fears related to driving, TMH can facilitate access to care. Veterans with PTSD often avoid reminders of trauma (ie, uniforms, evidence of physical injury, artwork, photographs related to war), which can often be found at the larger VAMCs. These veterans may find mental health care services in their homes or at local CBOCs more appealing.7,12,18

Implementation

Prior to the implementation of telehealth services, many CBOC providers would refer veterans in need of specialty care to the nearest VAMC, which were sometimes many hours away.1 In response to travel and access concerns, the VA has implemented various telehealth modalities, including TMH.

In 2008, about 230,000 veterans received mental health services via real-time clinical VTC at 300 VA CBOCs, and about 40,000 veterans enrolled in the In-Home Telehealth program.22 By 2011, > 380,000 veterans used clinic-based telehealth services and about 100,000 veterans used the in-home program.1 Between 2006 and 2008, the 98,000 veterans who used TMH modalities had fewer hospital admissions compared with those who did not; overall, the need for hospital services decreased by about 25% for those using TMH services.23

Although research suggests that TMH is an effective treatment modality, it does have limitations. A recent study noted several visual and audio difficulties that can emerge, including pixilation, “tracer” images with movement, low resolution, “frozen” or “choppy” images, delays in sound, echoes, or “mechanical sounding” voices.12 In some cases, physical details, such as crying, sniffling, or fidgeting, could not be clearly observed.12 Overall, these unforeseen issues can impact the ability to give and receive care through TMH modalities. Proper procedures need to be developed and implemented for each site.

Getting Started

Using TMH to provide mental health care at other VHA facilities requires planning and preparation. Logistics, such as preparation of the room and equipment, should be considered. Similarly, veteran and provider convenience must be considered.2,11 Before starting TMH at any VA facility, professionals working with the audiovisual technology and providing TMH care must complete necessary VA Talent Management System courses and obtain copies of certificates to assure they have met the appropriate training criteria. Providers must be credentialed to provide TMH services, including the telehealth curriculum offered by VA Employee Educational Services.2,24 An appropriate memorandum of understanding (MOU) must be created, and credentialing and privileging must also be acquired.

In addition to provider training, an information technology representative who can administer technical support as needed must be selected for both the provider and remote locations. Technologic complications can make TMH implementation much more challenging.12 As such, it is important to assure that both the veteran and the provider have the necessary TMH equipment. The selected communication device must be compatible with the technology requirements at the provider and remote facilities.12

In addition to designated technical support, the VISN TMH coordinator needs to have point-of-contact information for those who can assist with each site’s telehealth services and address the demand for EBP for PTSD or other desired services. After this information has been obtained, relationships must be developed and maintained with local leadership at each site, associated telehealth coordinators, and evidence-based therapy coordinators.

After contact has been established with remote facilities and the demand for services has been determined, there are several agreements and procedures to put in place before starting TMH services. An initial step is to develop a MOU agreement between the VISN TMH center and remote

sites that allows providers’ credentials and privileges to be shared. Also, it is important to establish a service agreement that outlines the procedures for staff at the remote site. This agreement includes checking in veterans, setting up the TMH rooms, transferring homework to VISN TMH providers, and connecting with the VISN TMH provider. In addition to service agreements, emergency procedures must be in place to ensure the safety of the veterans and the staff.24

After these agreements have been completed, the VISN TMH providers will have to complete request forms to obtain access to the Computerized Patient Record System at the remote facilities, which then must be approved by the Information Security Officer at that site. This is separate from the request at the provider’s site.12 It is essential to have points of contact for questions regarding this process. In order to facilitate referrals for TMH, electronic interfacility consult requests must be developed. Local staff need to collaborate with VISN TMH staff to ensure that the consult addresses the referral facilities need to meet the appropriate requirements.

Before the initiation of TMH services, each TMH provider has to establish clinics for scheduling appointments and obtaining workload credit. Program support assistants at the provider and remote sites must work together to ensure clinics are established correctly. This collaboration is essential for coding of visits and clinic mapping. After the clinics are “built,” appointment times will be set up based on the availability of the provider, support staff, and rooms at the remote site for the TMH session.

Once a consult is initiated, the VISN TMH EBP coordinator will review the consult and the veteran’s chart to ensure initial inclusion/exclusion criteria are met before accepting or canceling the consult. If the consult is accepted, a VISN TMH provider is assigned to the case and contacts the veteran to discuss the referral and (if the veteran is appropriate and interested) initiate services at the closest CBOC or at home. The VISN TMH regional center staff enter the appointment time for the veteran at both facility sites. The VISN TMH provider also coordinates with the CBOC staff to ensure that the veteran is checked in to the appointment and is provided with any questionnaires and necessary homework.

During the first session, the provider obtains consent from the veteran to engage in TMH services, conducts an assessment, and establishes rapport. The provider works with the veteran to develop a treatment plan for PTSD or other mental health diagnosis that will include the type of EBP. At the end of the first session, the next appointment is scheduled, and treatment materials are either mailed to the veteran or given to him or her onsite. After completing EBP, the VISN TMH center works with the referring provider to find follow-up services for the veteran.

The various steps necessary to begin an interfacility TMH clinic are summarized in Table 1.

Provider Training

Despite strong evidence of success, many providers remained skeptical about the efficacy of TMH. One study indicated that several providers in VISN 16 rarely used the established TMH programs because they were not familiar with them and applied TMH only for medication checks and consults.11 This skepticism was present in providers preparing to offer TMH as well as in providers referring veterans for TMH services. However, once providers better understood the TMH programs and had more experience using them, they were significantly more likely to use TMH for initial evaluations and ongoing psychotherapy. For these reasons, proper training and educational opportunities for practicing providers are vital to TMH implementation.9,11

To be proficient, providers need to become familiar with various TMH applications.10 Health care networks implementing TMH must ensure that their providers are well trained and prepared to give and receive proper consultation and support. Providers must also acquire several skills and familiarize themselves with available tools.9 In educating providers on the process and use of TMH, the authors suggest the following steps for TMH application:

- Learn new ways to chart in multiple systems and know how to troubleshoot during connectivity issues.

- Have an established administrative support collaborator at outpatient clinics to fax and exchange veteran homework.12

- The TMH clinic culture must be embedded where the veteran is being served in order to allow for a more realistic therapeutic feel. This type of clinic setting will allow for referrals at the veteran site and the availability to coordinate emergency procedures in the remote clinic.

Clinical Issues

Ongoing clinical issues need to be addressed continuously. Initially, referrals may be plentiful but not always appropriate. It is important to have an understanding with referring providers and remote sites about what constitutes a “good referral” as well as alternate referral options. It is imperative to outline inclusion and exclusion criteria that are clear and concise for referring providers. It is often helpful to revisit these criteria with potential referral sources after initiating services.

With the ability to provide inhome services, it is important to identify specific inclusion/exclusion criteria. Recommendations are based on research and clinical applications for exclusions, which are available on the Office of Technology Services website. These include imminent suicidality or homicidality, serious personality disorder or problematic character traits, acute substance disorders, psychotic disorders, and bipolar disorder. It is important to use sound clinical judgment, because the usual safeguards present in a remote clinic are not available for inhome services. Emergency planning is one of the most important aspects of the in-home TMH health services that are provided. The information for the emergency plan is obtained prior to initiation of services.

Emergency Plans

Each remote clinic that provides services to veterans must have an emergency plan that details procedures, phone numbers, and resources in case of medical and psychological emergencies as well as natural disasters. The VISN TMH provider will need to have a copy of the emergency plan as well as a list of contacts in case of an emergency during a TMH session.

It is recommended that TMH providers have several ways to contact key staff who can assist during an emergency. Usually the clinical coordinator and telehealth technician are the first responders to be alerted by the TMH provider during an emergency. They will then institute the remote clinic’s emergency protocol. Discussing these procedures and reviewing them with staff regularly is advisable, as key contacts may change.

In a psychological emergency, the VISN TMH provider may assist in implementing emergency procedures until a clinical counterpart at the remote site can be alerted. In the authors’ experience, VISN TMH providers have successfully de-escalated and diffused potentially emergent situations by maintaining constant realtime communication with veterans and staff by using VTC as well as interoffice communication. By offering assistance to veterans and staff during challenging situations, the VISN TMH provider will not only decrease concerns of veterans, but oftentimes integrate themselves into the treatment team of the remote clinic. The role of a VISN TMH provider can be isolative, with minimal contact with remote clinic staff, so it is important to increase visibility among staff at a remote site by communication with them even when there is not an emergency.

Treatment protocols may be determined by either administrative or clinical factors. With certain TMH interventions, the rooms used for veterans may be available for only certain periods, which may or may not fit with treatment protocols. For example, if a room is available for only an hour but a treatment protocol session is for 90 minutes, then another time slot needs to be found or a different treatment considered and offered. Although it is not ideal to have treatment protocols determined by scheduling factors, the reality of shared space at remote sites requires flexibility.

Sharing Materials and Homework Another clinical issue that is often overlooked is how to implement specific treatment protocols that entail the exchange of materials between VISN TMH providers and veterans. If materials will need to be exchanged between provider and veteran, a plan will have to be in place to facilitate this. The service agreement addresses these details, but remote staff may not always be aware of the details.

If a TMH provider opts to use faxes to send materials between a veteran and a provider, a desktop faxing program is recommended so veteran privacy is not compromised. Often, providers will wait to begin sessions until after they have received materials, but this may result in a delayed

session. One solution TMH providers can implement is mailing the materials and questionnaires to veterans before the session with clear instructions to complete them beforehand. Once the veteran arrives for the TMH session, she or he will verbally respond to the questionnaire and treatment materials. This will add time to a session but minimizes potential delays. Many of the clinical VTC units have movable cameras, so veterans can tilt the camera to show providers the forms and questionnaires.

The various steps necessary to address TMH clinical issues are summarized in Table 2.

VISIN 22 Pilot Project

The VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot, based at the VA San Diego Healthcare System, was tasked with developing and providing TMH EBP services for PTSD across VISN 22 and adjacent West Coast VISNs. In addition to creating standardized procedures, troubleshooting guides were established to assist other programs with implementation. The primary focus was to increase access to EBPs for veterans with PTSD in areas where there was either no available trained providers or delays for specific services. The program established 16 clinics as well as in-home

services in VISN 22, VISN 21, and VISN 20. In fiscal year (FY) 2013, the VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot provided 1,657 EBP encounters via TMH to 234 unique veterans with PTSD (Table 3).

The pilot project collected data to evaluate program effectiveness. The data were de-identified before being sent to the VA Central Office (VACO) TMH program manager. The following items were collected for the pilot: (1) clinical information; (2) consent to engage in treatment and telehealth; (3) release of information to share de-identified data to VACO for program monitoring; (4) demographic form; (5) Beck Depression Inventory-II (every other week); (6) PTSD Checklist (every other week); (7) World Health Organization Quality of Life (sessions 1, 7, final); (8) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (sessions 3, 7, final); (9) satisfaction survey (final); (10) mileage not driven by veterans who receive TMH services; (11) travel pay saved by VA; (12) no-show rates; and (13) veteran, TMH provider, and referral provider satisfaction.

The growth in number of encounters and number of unique veterans has increased steadily from the first quarter of FY14 through the second quarter of FY15 (Figure 1).

In January 2013, in-home TMH services were piloted. Although occasional technical difficulties occurred, 143 EBP encounters via TMH were provided to 42 unique veterans in 2013. The service has continued to expand, and in the first half of FY14, services were provided to 64 unique veterans for a total of 278 encounters, saving veterans 3,220 travel miles and saving the VA $1,336 in travel reimbursement. In-home TMH services will continue to expand as more providers in a variety of programs are being trained by the San Diego staff on how to provide these services to veterans in their homes. In addition to decreasing mileage and travel pay, the no-show rates are lower for TMH appointments in general (averaged 8%-10% vs facility no-show rate average of 13.5%) and with the use of inhome TMH, no-show rates were kept to 2%. The growth in the number of in-home encounters and the number of unique veterans has also increased steadily from the first quarter of FY14 thru the second quarter of FY15 (Figure 2).

In-Home TMH Services

The VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot often requests to have an in-person meeting with a veteran before starting TMH services in order to complete a waiver to download the software used by the VA for real-time video in-home services, a Release of Information for a Primary Support Person form, and an emergency plan.

It is also recommended that information about the veteran’s Internet connection, type of computer, type of software, presence of a camera and speakers, e-mail address, and access to secure messaging are obtained. During the initial contact with a veteran, the provider will discuss the rules and requirements to ensure HIPAA compliance. The veteran will need to have a private area for the call (not a restaurant, car, or other place where Wi-Fi is offered). Even with these discussions, some veterans will initiate services from a public place or a room in their home where family members will enter and exit frequently.

Although not required, it is recommended to have the veteran identify a primary support person and complete a release form to allow the TMH provider to contact that person in an emergency. The support person may be a person in the home (adult family member or caregiver) or someone nearby (neighbor, friend, or family member) who can contact emergency services if needed. After the necessary information is gathered and the veteran agrees to the conditions of participation, a test call will be completed. The TMH provider is often the person to conduct this call, but if available, a telehealth technician or facility telehealth coordinator may assist. The TMH provider may help the veteran download the appropriate software that is sent from the VA Scheduler software. The veteran initiates the call with the provider. Once the connection is made, the session may begin. Sites that are currently conducting in-home services have provided guides to veterans and newer TMH providers to outline the necessary steps for initiating services.

It is recommended that any provider interested in providing in-home TMH services use the Office of Technological Services help desk to assist in troubleshooting difficulties with connectivity. Challenges have included the software used for in-home TMH, periodic Internet outages, and compatibility issues.

Veteran Satisfaction

Veteran satisfaction was measured through a self-report satisfaction survey. The survey included 12 questions assessing overall experience in using TMH services. Eleven of the 12 questions included a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree); the last question was openended for additional comments.

A summary of the survey response of the initial 29 veterans who received TMH services suggested the following: (1) Veterans felt comfortable with using the TMH equipment and were able to see their clinician clearly; (2) Technical assistance was sufficient; (3) During the TMH session, they related to the provider as if it were a face-to-face meeting and that their needs were met; and (4) Veterans reported extremely high satisfaction with TMH and would refer TMH care to other veterans. Veterans found clinic locations very convenient and preferred the TMH modality of mental health services delivery to the alternative of travelling a long distance to see their provider (Table 4).

Written comments and recommendations from veterans supported the survey results. Most reported that they saved time and the convenience of the clinic allowed them to receive the treatment they need without interfering with their work schedule. However, some veterans still experienced trouble with travel to the remote clinic. Others felt their experience was different from the one they expected or they had a good experience via TMH but preferred face-to-face care.

Conclusion

The VISN 22 EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot have established the infrastructure of interfacility clinics to use EBPs for the treatment of PTSD. Also, the center has provided consultation and guidance to facilities interested in developing their own TMH programs. The TMH Center now plans to expand mental health services and include medication management and EBP services for non-PTSD psychiatric diagnoses. The established infrastructure will allow providers from one facility to cover the mental health service needs of other facilities when there are absences or gaps due to leave or delays/challenges in hiring in rural locations. Finally, TMH offers the potential to offer after-hours services to veterans in other time zones during providers’ regular tours of duty.

Several other TMH programs are now expanding services into veterans’ homes. There are several sites within the VHA that have piloted this TMH modality and developed guidelines and recommendations for further expansion. Currently VACO is encouraging all VHA facilities to increase in-home telehealth services, and the Office of Telehealth Services provides details on implementation. Interested parties are encouraged to routinely visit the VACO website for updated information.

Developing and implementing a new TMH program can be an arduous task, but the program has great potential to provide veteran-centered care. As TMH sessions progress, the provider and veteran become less aware of the camera and software and more aware of the therapeutic process. Challenges and delays in implementation are to be expected—these can occur frequently during the development and implementation stages of a TMH program. Maintaining consistent communication with staff at remote sites is essential for the success of any program.

As the VHA focuses on veterancentered care, TMH services will improve access to providers with specific, needed expertise. The authors hope these experiences can facilitate the continued growth of TMH and assuage any concerns a facility or provider may have about this modality of care. Delivery of TMH care can be challenging, but the ability to provide these services to veterans at times and locations convenient to them makes these challenges worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hauser wishes to thank Cathy, Anika, Jirina, Katia, and Max Hauser, and Alba Pillwein for their continued support. In memory of Beverly Ostroski.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Within VHA, telemental health (TMH) refers to behavioral health services that are provided remotely, using secure communication technologies, to veterans who are separated by distance from their mental health providers.1 Telemental health sometimes involves video teleconferencing (VTC) technology, where a veteran (or group of veterans) in one location and a provider in a different location are able to communicate in real time through a computer monitor or television screen.2 In the VHA, TMH visits are typically conducted from a central location (such as a medical center hospital) to a community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC), but pilot projects have also tested VTC in homes as well.1,3,4

In addition to providing timely access to behavioral health services in rural or underserved locations, TMH eliminates travel that may be disruptive or costly and allows mental health providers to consult with or provide supervision to one another. Telemental health can be used to make diagnoses, manage care, perform checkups, and provide long-term, follow-up care. Other uses for TMH include clinical assessment, individual and group psychotherapy, psycho-educational interventions, cognitive testing, and general psychiatric care.1,5,6 More recently, TMH has been used to provide evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) to individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health diagnoses.6,7 Such care may be particularly advantageous for veterans with PTSD, because traveling can be a burden for them or a trigger for PTSD symptoms.

Although interactive video technology is becoming widely available, its use is limited in health care systems due to lack of knowledge, education, logistical guidance, and technical training. The authors have conducted EBPs using VTC across VISN 22 in both office-to-office and office-to-home modalities and are providing EBPs using VTC to CBOCs in other VISNs across the western U.S. This article addresses these issues, outlining the necessary steps required to establish a TMH clinic and to share the successes of the EBP TMH Center and Regional Pilot used at VISN 22.

Telemental Health

Telemental health is an effective alternative to in-person treatment and is well regarded by both mental health providers and veterans. Overall, mental health providers believe it can help reduce the stigma associated with traditional mental health care and ease transportation-related issues for veterans. Telemental health allows access to care for veterans living in rural or remote areas in addition to those who are incarcerated or are otherwise unable to attend visits at primary VA facilities.2,8-10 In an assessment of TMH services in 40 CBOCs across VISN 16, most CBOC mental health providers found it to be an acceptable alternative to face-to-face care, recognize the value of TMH, and endorse a willingness to use and expand TMH programs within their clinics.11

Veterans who participated in TMH via VTC have expressed satisfaction with the decreased travel time and expenses, fewer interactions with crowds, and fewer parking problems.12 Several studies suggested that veterans preferred TMH to in-person contact due to more rapid access to care and specialists who would otherwise be unavailable at remote locations.5,10 Similarly, veterans who avoid in-person mental health care were more open to remote therapy for many of the reasons listed earlier. Studies suggest that veterans from both rural and urban locations are generally receptive to receiving mental health services via TMH.5,10

Several studies have found that TMH services may have advantages over standard in-person care. These advantages include decreasing transportation costs, travel time, and time missed at work and increasing system coverage area.13 Overall, both veterans and providers reported similar satisfaction between VTC and in-person sessions and, in some cases, prefer VTC interactions due to a sense of “easing into” intense therapies or having a “therapeutic distance” as treatment begins.12

Utility

Previous studies have shown that TMH can be used successfully to provide psychopharmacologic treatment to veterans who have major depressive disorder or schizophrenia, among other psychiatric disorders.5,8,14 Recent studies have focused on the feasibility of providing EBPs via TMH, particularly for the treatment of PTSD.12,15 Studies have shown that TMH services via VTC can be used successfully to provide cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and prolonged exposure therapy (PE).16-21 In these studies, both PE and CPT delivered via TMH were found to be as efficacious as in-person formats. Furthermore, TMH services were successfully used in individual and group sessions.

Research has emphasized the benefits of TMH for veterans who are uncomfortable in crowds, waiting rooms, or hospital lobbies.7,12,18 For patients with PTSD who are initially limited by fears related to driving, TMH can facilitate access to care. Veterans with PTSD often avoid reminders of trauma (ie, uniforms, evidence of physical injury, artwork, photographs related to war), which can often be found at the larger VAMCs. These veterans may find mental health care services in their homes or at local CBOCs more appealing.7,12,18

Implementation

Prior to the implementation of telehealth services, many CBOC providers would refer veterans in need of specialty care to the nearest VAMC, which were sometimes many hours away.1 In response to travel and access concerns, the VA has implemented various telehealth modalities, including TMH.

In 2008, about 230,000 veterans received mental health services via real-time clinical VTC at 300 VA CBOCs, and about 40,000 veterans enrolled in the In-Home Telehealth program.22 By 2011, > 380,000 veterans used clinic-based telehealth services and about 100,000 veterans used the in-home program.1 Between 2006 and 2008, the 98,000 veterans who used TMH modalities had fewer hospital admissions compared with those who did not; overall, the need for hospital services decreased by about 25% for those using TMH services.23

Although research suggests that TMH is an effective treatment modality, it does have limitations. A recent study noted several visual and audio difficulties that can emerge, including pixilation, “tracer” images with movement, low resolution, “frozen” or “choppy” images, delays in sound, echoes, or “mechanical sounding” voices.12 In some cases, physical details, such as crying, sniffling, or fidgeting, could not be clearly observed.12 Overall, these unforeseen issues can impact the ability to give and receive care through TMH modalities. Proper procedures need to be developed and implemented for each site.

Getting Started

Using TMH to provide mental health care at other VHA facilities requires planning and preparation. Logistics, such as preparation of the room and equipment, should be considered. Similarly, veteran and provider convenience must be considered.2,11 Before starting TMH at any VA facility, professionals working with the audiovisual technology and providing TMH care must complete necessary VA Talent Management System courses and obtain copies of certificates to assure they have met the appropriate training criteria. Providers must be credentialed to provide TMH services, including the telehealth curriculum offered by VA Employee Educational Services.2,24 An appropriate memorandum of understanding (MOU) must be created, and credentialing and privileging must also be acquired.

In addition to provider training, an information technology representative who can administer technical support as needed must be selected for both the provider and remote locations. Technologic complications can make TMH implementation much more challenging.12 As such, it is important to assure that both the veteran and the provider have the necessary TMH equipment. The selected communication device must be compatible with the technology requirements at the provider and remote facilities.12

In addition to designated technical support, the VISN TMH coordinator needs to have point-of-contact information for those who can assist with each site’s telehealth services and address the demand for EBP for PTSD or other desired services. After this information has been obtained, relationships must be developed and maintained with local leadership at each site, associated telehealth coordinators, and evidence-based therapy coordinators.

After contact has been established with remote facilities and the demand for services has been determined, there are several agreements and procedures to put in place before starting TMH services. An initial step is to develop a MOU agreement between the VISN TMH center and remote

sites that allows providers’ credentials and privileges to be shared. Also, it is important to establish a service agreement that outlines the procedures for staff at the remote site. This agreement includes checking in veterans, setting up the TMH rooms, transferring homework to VISN TMH providers, and connecting with the VISN TMH provider. In addition to service agreements, emergency procedures must be in place to ensure the safety of the veterans and the staff.24

After these agreements have been completed, the VISN TMH providers will have to complete request forms to obtain access to the Computerized Patient Record System at the remote facilities, which then must be approved by the Information Security Officer at that site. This is separate from the request at the provider’s site.12 It is essential to have points of contact for questions regarding this process. In order to facilitate referrals for TMH, electronic interfacility consult requests must be developed. Local staff need to collaborate with VISN TMH staff to ensure that the consult addresses the referral facilities need to meet the appropriate requirements.

Before the initiation of TMH services, each TMH provider has to establish clinics for scheduling appointments and obtaining workload credit. Program support assistants at the provider and remote sites must work together to ensure clinics are established correctly. This collaboration is essential for coding of visits and clinic mapping. After the clinics are “built,” appointment times will be set up based on the availability of the provider, support staff, and rooms at the remote site for the TMH session.

Once a consult is initiated, the VISN TMH EBP coordinator will review the consult and the veteran’s chart to ensure initial inclusion/exclusion criteria are met before accepting or canceling the consult. If the consult is accepted, a VISN TMH provider is assigned to the case and contacts the veteran to discuss the referral and (if the veteran is appropriate and interested) initiate services at the closest CBOC or at home. The VISN TMH regional center staff enter the appointment time for the veteran at both facility sites. The VISN TMH provider also coordinates with the CBOC staff to ensure that the veteran is checked in to the appointment and is provided with any questionnaires and necessary homework.

During the first session, the provider obtains consent from the veteran to engage in TMH services, conducts an assessment, and establishes rapport. The provider works with the veteran to develop a treatment plan for PTSD or other mental health diagnosis that will include the type of EBP. At the end of the first session, the next appointment is scheduled, and treatment materials are either mailed to the veteran or given to him or her onsite. After completing EBP, the VISN TMH center works with the referring provider to find follow-up services for the veteran.

The various steps necessary to begin an interfacility TMH clinic are summarized in Table 1.

Provider Training

Despite strong evidence of success, many providers remained skeptical about the efficacy of TMH. One study indicated that several providers in VISN 16 rarely used the established TMH programs because they were not familiar with them and applied TMH only for medication checks and consults.11 This skepticism was present in providers preparing to offer TMH as well as in providers referring veterans for TMH services. However, once providers better understood the TMH programs and had more experience using them, they were significantly more likely to use TMH for initial evaluations and ongoing psychotherapy. For these reasons, proper training and educational opportunities for practicing providers are vital to TMH implementation.9,11

To be proficient, providers need to become familiar with various TMH applications.10 Health care networks implementing TMH must ensure that their providers are well trained and prepared to give and receive proper consultation and support. Providers must also acquire several skills and familiarize themselves with available tools.9 In educating providers on the process and use of TMH, the authors suggest the following steps for TMH application:

- Learn new ways to chart in multiple systems and know how to troubleshoot during connectivity issues.

- Have an established administrative support collaborator at outpatient clinics to fax and exchange veteran homework.12

- The TMH clinic culture must be embedded where the veteran is being served in order to allow for a more realistic therapeutic feel. This type of clinic setting will allow for referrals at the veteran site and the availability to coordinate emergency procedures in the remote clinic.

Clinical Issues

Ongoing clinical issues need to be addressed continuously. Initially, referrals may be plentiful but not always appropriate. It is important to have an understanding with referring providers and remote sites about what constitutes a “good referral” as well as alternate referral options. It is imperative to outline inclusion and exclusion criteria that are clear and concise for referring providers. It is often helpful to revisit these criteria with potential referral sources after initiating services.

With the ability to provide inhome services, it is important to identify specific inclusion/exclusion criteria. Recommendations are based on research and clinical applications for exclusions, which are available on the Office of Technology Services website. These include imminent suicidality or homicidality, serious personality disorder or problematic character traits, acute substance disorders, psychotic disorders, and bipolar disorder. It is important to use sound clinical judgment, because the usual safeguards present in a remote clinic are not available for inhome services. Emergency planning is one of the most important aspects of the in-home TMH health services that are provided. The information for the emergency plan is obtained prior to initiation of services.

Emergency Plans

Each remote clinic that provides services to veterans must have an emergency plan that details procedures, phone numbers, and resources in case of medical and psychological emergencies as well as natural disasters. The VISN TMH provider will need to have a copy of the emergency plan as well as a list of contacts in case of an emergency during a TMH session.

It is recommended that TMH providers have several ways to contact key staff who can assist during an emergency. Usually the clinical coordinator and telehealth technician are the first responders to be alerted by the TMH provider during an emergency. They will then institute the remote clinic’s emergency protocol. Discussing these procedures and reviewing them with staff regularly is advisable, as key contacts may change.

In a psychological emergency, the VISN TMH provider may assist in implementing emergency procedures until a clinical counterpart at the remote site can be alerted. In the authors’ experience, VISN TMH providers have successfully de-escalated and diffused potentially emergent situations by maintaining constant realtime communication with veterans and staff by using VTC as well as interoffice communication. By offering assistance to veterans and staff during challenging situations, the VISN TMH provider will not only decrease concerns of veterans, but oftentimes integrate themselves into the treatment team of the remote clinic. The role of a VISN TMH provider can be isolative, with minimal contact with remote clinic staff, so it is important to increase visibility among staff at a remote site by communication with them even when there is not an emergency.

Treatment protocols may be determined by either administrative or clinical factors. With certain TMH interventions, the rooms used for veterans may be available for only certain periods, which may or may not fit with treatment protocols. For example, if a room is available for only an hour but a treatment protocol session is for 90 minutes, then another time slot needs to be found or a different treatment considered and offered. Although it is not ideal to have treatment protocols determined by scheduling factors, the reality of shared space at remote sites requires flexibility.

Sharing Materials and Homework Another clinical issue that is often overlooked is how to implement specific treatment protocols that entail the exchange of materials between VISN TMH providers and veterans. If materials will need to be exchanged between provider and veteran, a plan will have to be in place to facilitate this. The service agreement addresses these details, but remote staff may not always be aware of the details.

If a TMH provider opts to use faxes to send materials between a veteran and a provider, a desktop faxing program is recommended so veteran privacy is not compromised. Often, providers will wait to begin sessions until after they have received materials, but this may result in a delayed