User login

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) are health and wellness practices that are outside conventional allopathic medicine. In the U.S., the popularity of CAM has grown, and patients often use CAM to treat pain, insomnia, anxiety, and depression.1-5 Veterans also have been increasingly adding CAM to conventional medicine, although limited studies exist on veteran use and attitudes toward CAM.6-8

Recently, the VA has increased its CAM services, offering different treatments at various VA facilities where CAM is most commonly used to treat anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and back pain.9 Some veterans also seek CAM services outside the VA.6,8 Across studies of veterans and the broader population, having more years of education and higher income and being middle-aged, female, and white were associated with greater CAM use.1,3,6-8

Some CAM practices, such as acupuncture, require a practitioner’s regular and direct involvement. Other, independent CAM practices can be taught in classes, individual sessions, or through self-instructional multimedia. Once learned, these practices can be done independently, allowing for easier and less costly access. Independent CAM practices, such as yoga, meditation, breathing exercises, qigong, and tai chi promote general wellness or treat a particular ailment.

Although results have been mixed, several studies support independent CAM practices for treatment and symptom relief. For example, yoga improves symptoms in neurologic and psychiatric disorders, lessens pain, and helps decrease anxiety and depression and improve self-efficacy.10-13 Qigong can improve hypertensionand self-efficacy.14,15

This study examines veterans’ attitudes and beliefs about CAM, which can affect their interest and use of CAM services within and outside the VA. The focus is exclusively on independent CAM practices. At the time of the study, the availability of more direct CAM practices, such as acupuncture, was limited at many VA sites, and independently practiced techniques often require fewer resources and, therefore, could be adapted more easily. Subsequent references to CAM in this study refer only to independent CAM practices.

The current study surveyed veterans in New Jersey in multiple VA clinics and non-VA peer-counseling settings as part of an implementation study of a veteran-centric DVD called the STAR (Simple Tools to Aid and Restore) Well-Kit (SWK), which serves as a veteran introduction to CAM.16 Before watching the DVD, veterans were asked to fill out a baseline survey about their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with CAM as well as answer screening and demographic questions.

The authors describe the findings of the baseline survey to inform how to best implement CAM more broadly throughout VA. They expected that knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with CAM would vary by clinical setting and respondent characteristics and hypothesized that psychological factors would be related to interest in CAM. Finally, barriers and facilitators of use of CAM are reported to inform policies to promote veteran access to CAM.

Methods

This cross-sectional analysis of the baseline SWK surveys had no inclusion or exclusion criteria because participation was anonymous. Recipients received a packet that instructed them to complete a previewing survey, watch the DVD, and complete a postviewing survey about the DVD. Surveys were returned in person or by postage-paid envelopes. No follow-up reminders were provided. This study examines data from only the previewing survey, and all further references to the veteran presurvey refers to it as the survey.

Study sites were the outpatient services of the VA New Jersey Health Care System (VANJHCS) and a non-VHA New Jersey veteran peer-counseling office. VANJHCS, which enrolls patients from northern and central New Jersey, offers health care services at 2 campuses and 9 outpatient clinics. Waivers of informed consent were approved by the VANJHCS Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee given the anonymous and low-risk nature of the research.

Participant Recruitment

The survey was distributed at 4 settings selected with a focus on ambulatory services and a goal of ensuring participant diversity in age, deployment experience, and mental and physical health conditions. At 3 settings, surveys were distributed using 3 methods: by a researcher; left for pickup in waiting rooms; or by selected health care providers at their discretion in the context of routine clinical visits. The VANJHCS settings were outpatient mental-health clinics, outpatient primary-care settings, and outpatient transition-unit clinics for recent combat veterans. The fourth setting was a community veteran peer-support organization staffed by veterans and included events held at the organization’s offices, veteran informational and health fairs in the community, and outreach events at college campuses. In this setting, veteran peers distributed the SWK at their discretion; they were given suggested talking points for distribution.

Survey Data Collection

Veterans filled out baseline surveys before viewing the SWK DVD. The surveys were anonymous but coded with a number to allow for tracking by setting and dissemination method. The surveys asked for demographic and health information and experience with and interest in CAM techniques. To minimize respondent burden, the authors focused on the most critical domains as summarized in the background section (demographics; health status and symptoms, including pain; self-efficacy; mental health conditions; knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CAM).

Demographic Information

Age range was assessed to avoid collecting identifying information. The questionnaire also included gender, military era/deployment, employment status, and race and ethnicity.

- Self-Rated Health (SF1). Self-rated health was assessed with a widely used single-item question that correlates highly with actual overall health and with function and quality of life.17,18 Respondents were asked to rate their health as excellent (5), very good, good, fair, or poor (1).

- Pain Screen (PEG 3-item scale). This 3-item screen has shown reliability and validity and is comparable to longer pain questionnaires.19 Respondents were asked to rate 3 measures of their pain and its consequences on a scale of 0 (no pain or no interference from pain) to 10 (worst pain or interference). Responses were averaged to determine pain score.

- PTSD Screen. This 4-item PTSD screen was developed for primary care and is widely used in VA settings.20 For each item, respondents were asked to check off whether they have had specific PTSD symptoms within the past month. The screen was considered positive with 3 of 4 affirmative responses.

- Anxiety and Depression Screen (PHQ-4). This 4-item scale combines the brief 2-item scales for screening anxiety and depression in primary care.21 For each depression or anxiety symptom, respondents selected from “not at all,” (1) “several days ”(2), “more days than not,” (3) and “nearly every day.” (4) For each 2-item screen, a sum of 5 or more indicated a positive screen.

- Self-Efficacy for Health Management (modified). The original 6-item self-efficacy screen was developed to test self-efficacy in managing chronic disease.22 Since not all participants in the current study were expected to have a chronic disease, the questions were modified to address more general self-efficacy for health management. Although the scale had not been adapted in this way or validated with this change, other authors have similarly adapted it to address specific chronic diseases with satisfactory results.23,24 For each item, respondents were asked to rate their confidence in their ability to manage aspects of their health on a scale of 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (very confident). Participants could also check “not applicable” for items that did not apply to their health concerns, and these items were not counted in the average score.

- Familiarity With and Interest in CAM. The authors developed a checklist to assess whether participants had heard of, tried, or were practicing the 4 CAM techniques featured in the SWK and to gauge their interest in learning about them (ie, meditation/guided imagery, breathing exercises, yoga, tai chi or qigong). For each technique, respondents selected that they have “never heard of,” “heard of but never tried,” “have done this in the past,” or “are currently doing.” For some analyses, the first 2 and last 2 options were combined to determine whether respondents had done each practice. They were also asked to check off whether they would like to learn more about the practice and whether they would like to try it with an instructor and/or try it on their own. For some analyses, each technique was looked at separately, whereas for others, the 4 techniques were combined to determine whether they had tried or were currently doing any of them.

- Barriers to Practice. The authors developed a checklist of 10 barriers to practicing CAM techniques based on research but with adjustments to the specific practices and population under investigation.25 The checklist included an open-end response to allow respondents to add barriers. The barrier list was a checklist and not a validated scale.

- Perceived Benefits of CAM. The authors developed 2 questions to assess the perceived benefits of these techniques on functionality and overall wellness, rated on a Likert scale from 1 (no benefits) to 10 (very much).

Statistical Analysis

Survey instruments were scored according to generally accepted and published practices. Item-level analysis was performed to identify missing responses and describe the sample. Summary statistics were reported. Pearson product moment correlation was used to detect associations between continuous variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to detect associations between dichotomous and continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used to detect associations between categorical variables, specifically looking at clinically meaningful differences between veterans who had experience with or interest in trying independent CAM practices and those who did not. Linear regression analysis was used to determine significant associations between participant characteristics and the belief that independent CAM practices would be helpful with daily function.

Results

The response rate for returning surveys was low (n = 134; 18.2%). Surveys distributed by peers in the community setting had the highest response rate (38%), followed by surveys distributed in primary care (23%).

Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, information on nonresponder characteristics was not available. Respondents covered a range of ages, with 64% of respondents aged ≥ 50 years. Respondents were men (88%) and white (49%) or African American (40%). Fifty-five percent screened positive for at least 1 mental health condition (PTSD, depression, or anxiety). The average self-rated health was 2.9 on a scale of 1 (poor health) to 5 (excellent health). Gender, age range, race, and deployment status were comparable with New Jersey VA veteran demographics.26

Table 1 shows veteran experience and interest in CAM practices. More than half of veterans who returned the survey reported doing either a CAM practice or having done 1 (n = 82; 61%). Many also reported interest in trying at least 1 practice (n = 73; 55%) or learning more about at least 1 practice (n = 71; 53%) either on their own or with an instructor. More veterans indicated they would prefer to try the techniques with an instructor (n = 61; 46%) rather than on their own (n = 26; 19%). Chi-square testing showed that interest and experience with CAM were not significantly associated with specific demographic characteristics.

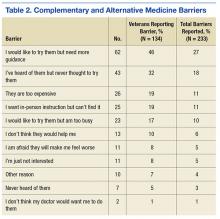

Several barriers to CAM practice were frequently cited (Table 2). The 2 most commonly endorsed barriers were veterans who wanted to try the techniques but needed more guidance (n = 62; 46%) and heard of CAM but never thought to try them (n = 43; 32%). Only a small percentage of veterans indicated that they did not think the practice would help (n = 13; 10%) or were concerned that it might hurt them (n = 11; 8%).

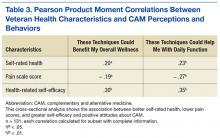

There were several significant bivariate associations (Table 3), although overall r2 values were low. More severe pain was associated with a weaker belief that the techniques could benefit overall wellness (r2 = – .19; P = .04) and help daily functioning (r2= – .27; P < .01). Higher health-related self-efficacy was associated with a stronger belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for overall wellness (r2= .30; P < .01) and daily function (r2 = .35; P < .01). Higher self-rated health was associated with stronger belief in effectiveness for overall wellness (r2 = .20; P = .02) and daily function (r2= .23; P < .01). One-way ANOVAs found no significant associations between belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for wellness or for daily activities (for which statistics are presented here) and positive screens for PTSD (F1,116 = 3.04; P = .08), depression (F1,116 = 2.06; P = .15), anxiety (F1,122 = 1.41; P = .23), or any of the 3 combined (F1,116 = 3.74; P = .06). None of the health factors was associated with veteran interest in trying a technique or with a history of trying at least 1 technique.

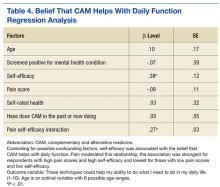

Of the multivariate linear regression models examining associations between veteran characteristics and responses to CAM, only 1 was significant (Table 4). Of all the factors in the model, only self-efficacy was significantly associated with the belief that CAM can improve daily function. Pain moderated this relationship; those with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with daily function only if they also had high self-efficacy (interaction term β = 0.27; SE = 0.03). For example, veterans with no pain (pain score 1 on a scale of 1-10) had a β = .07 (SE .13, P = .28), whereas those with the highest pain level (10) had a β = .92 (SE = .24, P = .001).

Discussion

The authors report 3 main findings from this study: Personal characteristics are not associated with experience, interest in, or belief in the efficacy of CAM; despite a large proportion reporting experience with CAM, veterans reported several barriers to using CAM; and the level of pain reported moderated the relationship between health-related self-efficacy and the belief that CAM will help with daily function.

Determining which personal characteristics are associated with CAM perceptions may indicate who is willing to try CAM techniques and who may require additional education or support. Although the authors hypothesized a difference in experience, interest, and belief of efficacy according to patient characteristics, these differences were not demonstrated. Some published research supports an association between white race, female sex, and middle or younger age and use of CAM, but this sample of veterans did not confirm these associations.1,3,6-8

The lack of associations may be related to selection bias, reflected in the relatively high report of baseline use of CAM. Nevertheless, this finding implies that clinicians should not make assumptions about an individual’s experience with CAM or interest in trying a modality. From a policy perspective, the VHA should consider a broad-based approach targeting a general audience or multiple segmented audiences to increase awareness and a trial of CAM for veterans.

Barriers should be considered when introducing CAM into routine clinical care. The current study revealed several important barriers to veterans accessing or trying CAM techniques, including need for guidance, the lack of awareness or access, and cost. The VHA services are often provided at low or no cost to eligible veterans, likely mitigating the cost barrier to a great extent. However, being able to easily access instruction in CAM modalities in a timely manner may be just as important. The authors detected a preference among respondents for classes to learn CAM (46%) vs independently (19%), supported by the commonly endorsed barrier to trying CAM of “I want in-person instruction but can’t find it.” Offering CAM modalities that can be taught in a group or individual setting and later practiced independently may be an appropriate approach to introduce CAM techniques to the largest number of people and encourage uptake. This approach can maximize access while satisfying many veterans’ preferences for in-person instruction. This leverage of skilled practitioner time could be extended for some modalities through remote telehealth participation or on-demand instruction, such as online videos or DVDs, including the SWK.

Chronic pain can be a challenge for patients and clinicians to manage, so the role of CAM in pain management is growing.2,27 The study’s findings suggest that motivating veterans with chronic pain to try CAM may take extra effort by the clinician. Multivariate linear regression modeling showed that respondents with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with their function only if they also had high health-related self-efficacy, whereas those with low pain scores reported this belief even with low self-efficacy. Thus, strong self-efficacy may overpower doubts about CAM that accompany having pain. Conversely, high reported pain levels may reduce self-efficacy and lead to doubts about the benefit of CAM.

In one study, the belief that lifestyle contributes to illness predicted CAM use, which is similar to this study’s finding that health-related self-efficacy predicted CAM use.8 Several other studies examined CAM use and self-efficacy, although usually not self-efficacy for general health management. To promote experimentation with CAM, patients with chronic pain may require interventions targeted to increase self-efficacy related to CAM.

Of the 733 surveys distributed to veterans, 134 (18%) responses were received. More than 60% of the respondents had tried a CAM technique, higher rates than reported by most other CAM utilization studies: U.S. prevalence studies range from 29% to 42% of respondents having tried some CAM technique, and studies of veterans or military personnel range from 37% to 50% having tried CAM.3,5-7 Because these studies asked about CAM generally or about specific practices that do not fully overlap with the independent CAM practices evaluated in the current study, it is difficult to assess how the experiences of the current sample compare with those populations.

Another study asked veterans with multiple sclerosis whether they were interested in trying CAM practices, and 40% responded “yes,” which is similar to 55% in the current study.6 It is possible the rate of experience with CAM is higher in the current study due to self-selection of respondents who were interested in the SWK. Another factor may be that some veterans were recruited from VA mental health clinics where independent CAM practices are more frequently offered.9 It is also possible that there are regional differences in CAM use; this study took place at a single facility in the northeast U.S., although subsequent phases of the SWK project involved more widespread national dissemination, to be reported in the future.

Limitations

Self-selection and low response rate are limitations in this study. Despite the low response rate, the demographic information of the sample generally resembles the population of veterans at VANJHCS for age, sex, era, health status, and presence of mental health problems.24 Of note, the authors received responses from a wide range of veterans in terms of age, military era, and care setting, including some veterans who do not use the VA. However, data are lacking for nonresponders, and the possibility remains that survey respondents self-selected and were more interested in or experienced with CAM than were nonrespondents. Regardless, many findings, including barriers to CAM and the interaction of pain and self-efficacy, are internally valid and are important to consider even if the sample is not representative of the veteran population.

Conclusion

No studies have focused on veteran use of independent CAM practices as defined for this study. These techniques (eg, meditation, qigong) may promote wellness and relieve common symptoms in veterans. The authors’ results suggest that a broad interest in independent CAM practices among veterans exists. The VA and other health care settings should consider implementing classes in these modalities, especially as their reach may be greater than other CAM modalities requiring one-on-one practitioner-patient interaction. Even with broader availability, patients with chronic pain may require extra attention and context to improve or overcome low health-related self-efficacy, maximizing their likelihood of engaging in CAM. This possibility needs to be explored.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the Veterans Affairs Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation, which was not involved in the study design or production of the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the work of Anna Rusiewicz, PhD, in developing the STAR Well-Kit that was disseminated during this study.

1. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, et al. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: results from a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):344-351.

2. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1-23.

3. Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, Müllner M, Kundi M, Kaye AD. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J. 2012;12(1):45-56.

4. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(4):246-252.

5. Smith TC, Ryan MA, Smith B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US Navy and Marine Corps personnel. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:16.

6. Campbell DG, Turner AP, Williams RM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in veterans with multiple sclerosis: prevalence and demographic associations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43(1):99-110.

7. Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and alternative medicine: implications for integrated care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1697-1704.

8. McEachrane-Gross FP, Liebschutz JM, Berlowitz D. Use of selected complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments in veterans with cancer or chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:34.

9. Ezeji-Okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ, Durfee JM. State of care: complementary and alternative medicine in Veterans Health Administration—2011 survey results. Fed Pract. 2013;30(11):14-19.

10. Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(4).

11. Büssing A, Ostermann T, Lüdtke R, Michalsen A. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain. 2012;13(1):1-9.

12. Lee SW, Mancuso CA, Charlson ME. Prospective study of new participants in a community-based mind-body training program. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):760-765.

13. Waelde LC, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. A pilot study of a yoga and meditation intervention for dementia caregiver stress. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(6):677-687.

14. Lee MS, Lee MS, Kim HJ, Choi ES. Effects of qigong on blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other lipid levels in essential hypertension patients. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114(7):777-786.

15. Lee MS, Lim HJ, Lee MS. Impact of qigong exercise on self-efficacy and other cognitive perceptual variables in patients with essential hypertension. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(4):675-680.

16. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, War Related Illness & Injury Study Center. STAR Well-Kit. http://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/WARRELATEDILLNESS/education/STAR/index.asp. Updated September 18, 2015. Accessed July 6, 2016.

17. Benyamini Y, Idler EL, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Positive affect and function as influences on self-assessments of health: expanding our view beyond illness and disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(2):P107-P116.

18. Idler EL, Kasl SV. Self-ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional ability? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(6):S344-S353.

19. Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733-738.

20. Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9(1):9-14.

21. Kroenke K. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621.

22. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256-262.

23. Kim MT, Han HR, Song HJ, et al. A community-based, culturally tailored behavioral intervention for Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(6):986-994.

24. Webel AR, Okonsky J. Psychometric properties of a Symptom Management Self-Efficacy Scale for women living with HIV/AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):549-557.

25. Jain N, Astin JA. Barriers to acceptance: an exploratory study of complementary/alternative medicine disuse. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7(6):689-696.

26. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. VA facilities by state. http://www.va.gov/vetdata. Updated June 3, 2016. Accessed July 6, 2016.

27. Hassett AL, Williams DA. Non-pharmacological treatment of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):299-309.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) are health and wellness practices that are outside conventional allopathic medicine. In the U.S., the popularity of CAM has grown, and patients often use CAM to treat pain, insomnia, anxiety, and depression.1-5 Veterans also have been increasingly adding CAM to conventional medicine, although limited studies exist on veteran use and attitudes toward CAM.6-8

Recently, the VA has increased its CAM services, offering different treatments at various VA facilities where CAM is most commonly used to treat anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and back pain.9 Some veterans also seek CAM services outside the VA.6,8 Across studies of veterans and the broader population, having more years of education and higher income and being middle-aged, female, and white were associated with greater CAM use.1,3,6-8

Some CAM practices, such as acupuncture, require a practitioner’s regular and direct involvement. Other, independent CAM practices can be taught in classes, individual sessions, or through self-instructional multimedia. Once learned, these practices can be done independently, allowing for easier and less costly access. Independent CAM practices, such as yoga, meditation, breathing exercises, qigong, and tai chi promote general wellness or treat a particular ailment.

Although results have been mixed, several studies support independent CAM practices for treatment and symptom relief. For example, yoga improves symptoms in neurologic and psychiatric disorders, lessens pain, and helps decrease anxiety and depression and improve self-efficacy.10-13 Qigong can improve hypertensionand self-efficacy.14,15

This study examines veterans’ attitudes and beliefs about CAM, which can affect their interest and use of CAM services within and outside the VA. The focus is exclusively on independent CAM practices. At the time of the study, the availability of more direct CAM practices, such as acupuncture, was limited at many VA sites, and independently practiced techniques often require fewer resources and, therefore, could be adapted more easily. Subsequent references to CAM in this study refer only to independent CAM practices.

The current study surveyed veterans in New Jersey in multiple VA clinics and non-VA peer-counseling settings as part of an implementation study of a veteran-centric DVD called the STAR (Simple Tools to Aid and Restore) Well-Kit (SWK), which serves as a veteran introduction to CAM.16 Before watching the DVD, veterans were asked to fill out a baseline survey about their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with CAM as well as answer screening and demographic questions.

The authors describe the findings of the baseline survey to inform how to best implement CAM more broadly throughout VA. They expected that knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with CAM would vary by clinical setting and respondent characteristics and hypothesized that psychological factors would be related to interest in CAM. Finally, barriers and facilitators of use of CAM are reported to inform policies to promote veteran access to CAM.

Methods

This cross-sectional analysis of the baseline SWK surveys had no inclusion or exclusion criteria because participation was anonymous. Recipients received a packet that instructed them to complete a previewing survey, watch the DVD, and complete a postviewing survey about the DVD. Surveys were returned in person or by postage-paid envelopes. No follow-up reminders were provided. This study examines data from only the previewing survey, and all further references to the veteran presurvey refers to it as the survey.

Study sites were the outpatient services of the VA New Jersey Health Care System (VANJHCS) and a non-VHA New Jersey veteran peer-counseling office. VANJHCS, which enrolls patients from northern and central New Jersey, offers health care services at 2 campuses and 9 outpatient clinics. Waivers of informed consent were approved by the VANJHCS Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee given the anonymous and low-risk nature of the research.

Participant Recruitment

The survey was distributed at 4 settings selected with a focus on ambulatory services and a goal of ensuring participant diversity in age, deployment experience, and mental and physical health conditions. At 3 settings, surveys were distributed using 3 methods: by a researcher; left for pickup in waiting rooms; or by selected health care providers at their discretion in the context of routine clinical visits. The VANJHCS settings were outpatient mental-health clinics, outpatient primary-care settings, and outpatient transition-unit clinics for recent combat veterans. The fourth setting was a community veteran peer-support organization staffed by veterans and included events held at the organization’s offices, veteran informational and health fairs in the community, and outreach events at college campuses. In this setting, veteran peers distributed the SWK at their discretion; they were given suggested talking points for distribution.

Survey Data Collection

Veterans filled out baseline surveys before viewing the SWK DVD. The surveys were anonymous but coded with a number to allow for tracking by setting and dissemination method. The surveys asked for demographic and health information and experience with and interest in CAM techniques. To minimize respondent burden, the authors focused on the most critical domains as summarized in the background section (demographics; health status and symptoms, including pain; self-efficacy; mental health conditions; knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CAM).

Demographic Information

Age range was assessed to avoid collecting identifying information. The questionnaire also included gender, military era/deployment, employment status, and race and ethnicity.

- Self-Rated Health (SF1). Self-rated health was assessed with a widely used single-item question that correlates highly with actual overall health and with function and quality of life.17,18 Respondents were asked to rate their health as excellent (5), very good, good, fair, or poor (1).

- Pain Screen (PEG 3-item scale). This 3-item screen has shown reliability and validity and is comparable to longer pain questionnaires.19 Respondents were asked to rate 3 measures of their pain and its consequences on a scale of 0 (no pain or no interference from pain) to 10 (worst pain or interference). Responses were averaged to determine pain score.

- PTSD Screen. This 4-item PTSD screen was developed for primary care and is widely used in VA settings.20 For each item, respondents were asked to check off whether they have had specific PTSD symptoms within the past month. The screen was considered positive with 3 of 4 affirmative responses.

- Anxiety and Depression Screen (PHQ-4). This 4-item scale combines the brief 2-item scales for screening anxiety and depression in primary care.21 For each depression or anxiety symptom, respondents selected from “not at all,” (1) “several days ”(2), “more days than not,” (3) and “nearly every day.” (4) For each 2-item screen, a sum of 5 or more indicated a positive screen.

- Self-Efficacy for Health Management (modified). The original 6-item self-efficacy screen was developed to test self-efficacy in managing chronic disease.22 Since not all participants in the current study were expected to have a chronic disease, the questions were modified to address more general self-efficacy for health management. Although the scale had not been adapted in this way or validated with this change, other authors have similarly adapted it to address specific chronic diseases with satisfactory results.23,24 For each item, respondents were asked to rate their confidence in their ability to manage aspects of their health on a scale of 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (very confident). Participants could also check “not applicable” for items that did not apply to their health concerns, and these items were not counted in the average score.

- Familiarity With and Interest in CAM. The authors developed a checklist to assess whether participants had heard of, tried, or were practicing the 4 CAM techniques featured in the SWK and to gauge their interest in learning about them (ie, meditation/guided imagery, breathing exercises, yoga, tai chi or qigong). For each technique, respondents selected that they have “never heard of,” “heard of but never tried,” “have done this in the past,” or “are currently doing.” For some analyses, the first 2 and last 2 options were combined to determine whether respondents had done each practice. They were also asked to check off whether they would like to learn more about the practice and whether they would like to try it with an instructor and/or try it on their own. For some analyses, each technique was looked at separately, whereas for others, the 4 techniques were combined to determine whether they had tried or were currently doing any of them.

- Barriers to Practice. The authors developed a checklist of 10 barriers to practicing CAM techniques based on research but with adjustments to the specific practices and population under investigation.25 The checklist included an open-end response to allow respondents to add barriers. The barrier list was a checklist and not a validated scale.

- Perceived Benefits of CAM. The authors developed 2 questions to assess the perceived benefits of these techniques on functionality and overall wellness, rated on a Likert scale from 1 (no benefits) to 10 (very much).

Statistical Analysis

Survey instruments were scored according to generally accepted and published practices. Item-level analysis was performed to identify missing responses and describe the sample. Summary statistics were reported. Pearson product moment correlation was used to detect associations between continuous variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to detect associations between dichotomous and continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used to detect associations between categorical variables, specifically looking at clinically meaningful differences between veterans who had experience with or interest in trying independent CAM practices and those who did not. Linear regression analysis was used to determine significant associations between participant characteristics and the belief that independent CAM practices would be helpful with daily function.

Results

The response rate for returning surveys was low (n = 134; 18.2%). Surveys distributed by peers in the community setting had the highest response rate (38%), followed by surveys distributed in primary care (23%).

Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, information on nonresponder characteristics was not available. Respondents covered a range of ages, with 64% of respondents aged ≥ 50 years. Respondents were men (88%) and white (49%) or African American (40%). Fifty-five percent screened positive for at least 1 mental health condition (PTSD, depression, or anxiety). The average self-rated health was 2.9 on a scale of 1 (poor health) to 5 (excellent health). Gender, age range, race, and deployment status were comparable with New Jersey VA veteran demographics.26

Table 1 shows veteran experience and interest in CAM practices. More than half of veterans who returned the survey reported doing either a CAM practice or having done 1 (n = 82; 61%). Many also reported interest in trying at least 1 practice (n = 73; 55%) or learning more about at least 1 practice (n = 71; 53%) either on their own or with an instructor. More veterans indicated they would prefer to try the techniques with an instructor (n = 61; 46%) rather than on their own (n = 26; 19%). Chi-square testing showed that interest and experience with CAM were not significantly associated with specific demographic characteristics.

Several barriers to CAM practice were frequently cited (Table 2). The 2 most commonly endorsed barriers were veterans who wanted to try the techniques but needed more guidance (n = 62; 46%) and heard of CAM but never thought to try them (n = 43; 32%). Only a small percentage of veterans indicated that they did not think the practice would help (n = 13; 10%) or were concerned that it might hurt them (n = 11; 8%).

There were several significant bivariate associations (Table 3), although overall r2 values were low. More severe pain was associated with a weaker belief that the techniques could benefit overall wellness (r2 = – .19; P = .04) and help daily functioning (r2= – .27; P < .01). Higher health-related self-efficacy was associated with a stronger belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for overall wellness (r2= .30; P < .01) and daily function (r2 = .35; P < .01). Higher self-rated health was associated with stronger belief in effectiveness for overall wellness (r2 = .20; P = .02) and daily function (r2= .23; P < .01). One-way ANOVAs found no significant associations between belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for wellness or for daily activities (for which statistics are presented here) and positive screens for PTSD (F1,116 = 3.04; P = .08), depression (F1,116 = 2.06; P = .15), anxiety (F1,122 = 1.41; P = .23), or any of the 3 combined (F1,116 = 3.74; P = .06). None of the health factors was associated with veteran interest in trying a technique or with a history of trying at least 1 technique.

Of the multivariate linear regression models examining associations between veteran characteristics and responses to CAM, only 1 was significant (Table 4). Of all the factors in the model, only self-efficacy was significantly associated with the belief that CAM can improve daily function. Pain moderated this relationship; those with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with daily function only if they also had high self-efficacy (interaction term β = 0.27; SE = 0.03). For example, veterans with no pain (pain score 1 on a scale of 1-10) had a β = .07 (SE .13, P = .28), whereas those with the highest pain level (10) had a β = .92 (SE = .24, P = .001).

Discussion

The authors report 3 main findings from this study: Personal characteristics are not associated with experience, interest in, or belief in the efficacy of CAM; despite a large proportion reporting experience with CAM, veterans reported several barriers to using CAM; and the level of pain reported moderated the relationship between health-related self-efficacy and the belief that CAM will help with daily function.

Determining which personal characteristics are associated with CAM perceptions may indicate who is willing to try CAM techniques and who may require additional education or support. Although the authors hypothesized a difference in experience, interest, and belief of efficacy according to patient characteristics, these differences were not demonstrated. Some published research supports an association between white race, female sex, and middle or younger age and use of CAM, but this sample of veterans did not confirm these associations.1,3,6-8

The lack of associations may be related to selection bias, reflected in the relatively high report of baseline use of CAM. Nevertheless, this finding implies that clinicians should not make assumptions about an individual’s experience with CAM or interest in trying a modality. From a policy perspective, the VHA should consider a broad-based approach targeting a general audience or multiple segmented audiences to increase awareness and a trial of CAM for veterans.

Barriers should be considered when introducing CAM into routine clinical care. The current study revealed several important barriers to veterans accessing or trying CAM techniques, including need for guidance, the lack of awareness or access, and cost. The VHA services are often provided at low or no cost to eligible veterans, likely mitigating the cost barrier to a great extent. However, being able to easily access instruction in CAM modalities in a timely manner may be just as important. The authors detected a preference among respondents for classes to learn CAM (46%) vs independently (19%), supported by the commonly endorsed barrier to trying CAM of “I want in-person instruction but can’t find it.” Offering CAM modalities that can be taught in a group or individual setting and later practiced independently may be an appropriate approach to introduce CAM techniques to the largest number of people and encourage uptake. This approach can maximize access while satisfying many veterans’ preferences for in-person instruction. This leverage of skilled practitioner time could be extended for some modalities through remote telehealth participation or on-demand instruction, such as online videos or DVDs, including the SWK.

Chronic pain can be a challenge for patients and clinicians to manage, so the role of CAM in pain management is growing.2,27 The study’s findings suggest that motivating veterans with chronic pain to try CAM may take extra effort by the clinician. Multivariate linear regression modeling showed that respondents with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with their function only if they also had high health-related self-efficacy, whereas those with low pain scores reported this belief even with low self-efficacy. Thus, strong self-efficacy may overpower doubts about CAM that accompany having pain. Conversely, high reported pain levels may reduce self-efficacy and lead to doubts about the benefit of CAM.

In one study, the belief that lifestyle contributes to illness predicted CAM use, which is similar to this study’s finding that health-related self-efficacy predicted CAM use.8 Several other studies examined CAM use and self-efficacy, although usually not self-efficacy for general health management. To promote experimentation with CAM, patients with chronic pain may require interventions targeted to increase self-efficacy related to CAM.

Of the 733 surveys distributed to veterans, 134 (18%) responses were received. More than 60% of the respondents had tried a CAM technique, higher rates than reported by most other CAM utilization studies: U.S. prevalence studies range from 29% to 42% of respondents having tried some CAM technique, and studies of veterans or military personnel range from 37% to 50% having tried CAM.3,5-7 Because these studies asked about CAM generally or about specific practices that do not fully overlap with the independent CAM practices evaluated in the current study, it is difficult to assess how the experiences of the current sample compare with those populations.

Another study asked veterans with multiple sclerosis whether they were interested in trying CAM practices, and 40% responded “yes,” which is similar to 55% in the current study.6 It is possible the rate of experience with CAM is higher in the current study due to self-selection of respondents who were interested in the SWK. Another factor may be that some veterans were recruited from VA mental health clinics where independent CAM practices are more frequently offered.9 It is also possible that there are regional differences in CAM use; this study took place at a single facility in the northeast U.S., although subsequent phases of the SWK project involved more widespread national dissemination, to be reported in the future.

Limitations

Self-selection and low response rate are limitations in this study. Despite the low response rate, the demographic information of the sample generally resembles the population of veterans at VANJHCS for age, sex, era, health status, and presence of mental health problems.24 Of note, the authors received responses from a wide range of veterans in terms of age, military era, and care setting, including some veterans who do not use the VA. However, data are lacking for nonresponders, and the possibility remains that survey respondents self-selected and were more interested in or experienced with CAM than were nonrespondents. Regardless, many findings, including barriers to CAM and the interaction of pain and self-efficacy, are internally valid and are important to consider even if the sample is not representative of the veteran population.

Conclusion

No studies have focused on veteran use of independent CAM practices as defined for this study. These techniques (eg, meditation, qigong) may promote wellness and relieve common symptoms in veterans. The authors’ results suggest that a broad interest in independent CAM practices among veterans exists. The VA and other health care settings should consider implementing classes in these modalities, especially as their reach may be greater than other CAM modalities requiring one-on-one practitioner-patient interaction. Even with broader availability, patients with chronic pain may require extra attention and context to improve or overcome low health-related self-efficacy, maximizing their likelihood of engaging in CAM. This possibility needs to be explored.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the Veterans Affairs Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation, which was not involved in the study design or production of the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the work of Anna Rusiewicz, PhD, in developing the STAR Well-Kit that was disseminated during this study.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) are health and wellness practices that are outside conventional allopathic medicine. In the U.S., the popularity of CAM has grown, and patients often use CAM to treat pain, insomnia, anxiety, and depression.1-5 Veterans also have been increasingly adding CAM to conventional medicine, although limited studies exist on veteran use and attitudes toward CAM.6-8

Recently, the VA has increased its CAM services, offering different treatments at various VA facilities where CAM is most commonly used to treat anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and back pain.9 Some veterans also seek CAM services outside the VA.6,8 Across studies of veterans and the broader population, having more years of education and higher income and being middle-aged, female, and white were associated with greater CAM use.1,3,6-8

Some CAM practices, such as acupuncture, require a practitioner’s regular and direct involvement. Other, independent CAM practices can be taught in classes, individual sessions, or through self-instructional multimedia. Once learned, these practices can be done independently, allowing for easier and less costly access. Independent CAM practices, such as yoga, meditation, breathing exercises, qigong, and tai chi promote general wellness or treat a particular ailment.

Although results have been mixed, several studies support independent CAM practices for treatment and symptom relief. For example, yoga improves symptoms in neurologic and psychiatric disorders, lessens pain, and helps decrease anxiety and depression and improve self-efficacy.10-13 Qigong can improve hypertensionand self-efficacy.14,15

This study examines veterans’ attitudes and beliefs about CAM, which can affect their interest and use of CAM services within and outside the VA. The focus is exclusively on independent CAM practices. At the time of the study, the availability of more direct CAM practices, such as acupuncture, was limited at many VA sites, and independently practiced techniques often require fewer resources and, therefore, could be adapted more easily. Subsequent references to CAM in this study refer only to independent CAM practices.

The current study surveyed veterans in New Jersey in multiple VA clinics and non-VA peer-counseling settings as part of an implementation study of a veteran-centric DVD called the STAR (Simple Tools to Aid and Restore) Well-Kit (SWK), which serves as a veteran introduction to CAM.16 Before watching the DVD, veterans were asked to fill out a baseline survey about their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with CAM as well as answer screening and demographic questions.

The authors describe the findings of the baseline survey to inform how to best implement CAM more broadly throughout VA. They expected that knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with CAM would vary by clinical setting and respondent characteristics and hypothesized that psychological factors would be related to interest in CAM. Finally, barriers and facilitators of use of CAM are reported to inform policies to promote veteran access to CAM.

Methods

This cross-sectional analysis of the baseline SWK surveys had no inclusion or exclusion criteria because participation was anonymous. Recipients received a packet that instructed them to complete a previewing survey, watch the DVD, and complete a postviewing survey about the DVD. Surveys were returned in person or by postage-paid envelopes. No follow-up reminders were provided. This study examines data from only the previewing survey, and all further references to the veteran presurvey refers to it as the survey.

Study sites were the outpatient services of the VA New Jersey Health Care System (VANJHCS) and a non-VHA New Jersey veteran peer-counseling office. VANJHCS, which enrolls patients from northern and central New Jersey, offers health care services at 2 campuses and 9 outpatient clinics. Waivers of informed consent were approved by the VANJHCS Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee given the anonymous and low-risk nature of the research.

Participant Recruitment

The survey was distributed at 4 settings selected with a focus on ambulatory services and a goal of ensuring participant diversity in age, deployment experience, and mental and physical health conditions. At 3 settings, surveys were distributed using 3 methods: by a researcher; left for pickup in waiting rooms; or by selected health care providers at their discretion in the context of routine clinical visits. The VANJHCS settings were outpatient mental-health clinics, outpatient primary-care settings, and outpatient transition-unit clinics for recent combat veterans. The fourth setting was a community veteran peer-support organization staffed by veterans and included events held at the organization’s offices, veteran informational and health fairs in the community, and outreach events at college campuses. In this setting, veteran peers distributed the SWK at their discretion; they were given suggested talking points for distribution.

Survey Data Collection

Veterans filled out baseline surveys before viewing the SWK DVD. The surveys were anonymous but coded with a number to allow for tracking by setting and dissemination method. The surveys asked for demographic and health information and experience with and interest in CAM techniques. To minimize respondent burden, the authors focused on the most critical domains as summarized in the background section (demographics; health status and symptoms, including pain; self-efficacy; mental health conditions; knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CAM).

Demographic Information

Age range was assessed to avoid collecting identifying information. The questionnaire also included gender, military era/deployment, employment status, and race and ethnicity.

- Self-Rated Health (SF1). Self-rated health was assessed with a widely used single-item question that correlates highly with actual overall health and with function and quality of life.17,18 Respondents were asked to rate their health as excellent (5), very good, good, fair, or poor (1).

- Pain Screen (PEG 3-item scale). This 3-item screen has shown reliability and validity and is comparable to longer pain questionnaires.19 Respondents were asked to rate 3 measures of their pain and its consequences on a scale of 0 (no pain or no interference from pain) to 10 (worst pain or interference). Responses were averaged to determine pain score.

- PTSD Screen. This 4-item PTSD screen was developed for primary care and is widely used in VA settings.20 For each item, respondents were asked to check off whether they have had specific PTSD symptoms within the past month. The screen was considered positive with 3 of 4 affirmative responses.

- Anxiety and Depression Screen (PHQ-4). This 4-item scale combines the brief 2-item scales for screening anxiety and depression in primary care.21 For each depression or anxiety symptom, respondents selected from “not at all,” (1) “several days ”(2), “more days than not,” (3) and “nearly every day.” (4) For each 2-item screen, a sum of 5 or more indicated a positive screen.

- Self-Efficacy for Health Management (modified). The original 6-item self-efficacy screen was developed to test self-efficacy in managing chronic disease.22 Since not all participants in the current study were expected to have a chronic disease, the questions were modified to address more general self-efficacy for health management. Although the scale had not been adapted in this way or validated with this change, other authors have similarly adapted it to address specific chronic diseases with satisfactory results.23,24 For each item, respondents were asked to rate their confidence in their ability to manage aspects of their health on a scale of 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (very confident). Participants could also check “not applicable” for items that did not apply to their health concerns, and these items were not counted in the average score.

- Familiarity With and Interest in CAM. The authors developed a checklist to assess whether participants had heard of, tried, or were practicing the 4 CAM techniques featured in the SWK and to gauge their interest in learning about them (ie, meditation/guided imagery, breathing exercises, yoga, tai chi or qigong). For each technique, respondents selected that they have “never heard of,” “heard of but never tried,” “have done this in the past,” or “are currently doing.” For some analyses, the first 2 and last 2 options were combined to determine whether respondents had done each practice. They were also asked to check off whether they would like to learn more about the practice and whether they would like to try it with an instructor and/or try it on their own. For some analyses, each technique was looked at separately, whereas for others, the 4 techniques were combined to determine whether they had tried or were currently doing any of them.

- Barriers to Practice. The authors developed a checklist of 10 barriers to practicing CAM techniques based on research but with adjustments to the specific practices and population under investigation.25 The checklist included an open-end response to allow respondents to add barriers. The barrier list was a checklist and not a validated scale.

- Perceived Benefits of CAM. The authors developed 2 questions to assess the perceived benefits of these techniques on functionality and overall wellness, rated on a Likert scale from 1 (no benefits) to 10 (very much).

Statistical Analysis

Survey instruments were scored according to generally accepted and published practices. Item-level analysis was performed to identify missing responses and describe the sample. Summary statistics were reported. Pearson product moment correlation was used to detect associations between continuous variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to detect associations between dichotomous and continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used to detect associations between categorical variables, specifically looking at clinically meaningful differences between veterans who had experience with or interest in trying independent CAM practices and those who did not. Linear regression analysis was used to determine significant associations between participant characteristics and the belief that independent CAM practices would be helpful with daily function.

Results

The response rate for returning surveys was low (n = 134; 18.2%). Surveys distributed by peers in the community setting had the highest response rate (38%), followed by surveys distributed in primary care (23%).

Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, information on nonresponder characteristics was not available. Respondents covered a range of ages, with 64% of respondents aged ≥ 50 years. Respondents were men (88%) and white (49%) or African American (40%). Fifty-five percent screened positive for at least 1 mental health condition (PTSD, depression, or anxiety). The average self-rated health was 2.9 on a scale of 1 (poor health) to 5 (excellent health). Gender, age range, race, and deployment status were comparable with New Jersey VA veteran demographics.26

Table 1 shows veteran experience and interest in CAM practices. More than half of veterans who returned the survey reported doing either a CAM practice or having done 1 (n = 82; 61%). Many also reported interest in trying at least 1 practice (n = 73; 55%) or learning more about at least 1 practice (n = 71; 53%) either on their own or with an instructor. More veterans indicated they would prefer to try the techniques with an instructor (n = 61; 46%) rather than on their own (n = 26; 19%). Chi-square testing showed that interest and experience with CAM were not significantly associated with specific demographic characteristics.

Several barriers to CAM practice were frequently cited (Table 2). The 2 most commonly endorsed barriers were veterans who wanted to try the techniques but needed more guidance (n = 62; 46%) and heard of CAM but never thought to try them (n = 43; 32%). Only a small percentage of veterans indicated that they did not think the practice would help (n = 13; 10%) or were concerned that it might hurt them (n = 11; 8%).

There were several significant bivariate associations (Table 3), although overall r2 values were low. More severe pain was associated with a weaker belief that the techniques could benefit overall wellness (r2 = – .19; P = .04) and help daily functioning (r2= – .27; P < .01). Higher health-related self-efficacy was associated with a stronger belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for overall wellness (r2= .30; P < .01) and daily function (r2 = .35; P < .01). Higher self-rated health was associated with stronger belief in effectiveness for overall wellness (r2 = .20; P = .02) and daily function (r2= .23; P < .01). One-way ANOVAs found no significant associations between belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for wellness or for daily activities (for which statistics are presented here) and positive screens for PTSD (F1,116 = 3.04; P = .08), depression (F1,116 = 2.06; P = .15), anxiety (F1,122 = 1.41; P = .23), or any of the 3 combined (F1,116 = 3.74; P = .06). None of the health factors was associated with veteran interest in trying a technique or with a history of trying at least 1 technique.

Of the multivariate linear regression models examining associations between veteran characteristics and responses to CAM, only 1 was significant (Table 4). Of all the factors in the model, only self-efficacy was significantly associated with the belief that CAM can improve daily function. Pain moderated this relationship; those with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with daily function only if they also had high self-efficacy (interaction term β = 0.27; SE = 0.03). For example, veterans with no pain (pain score 1 on a scale of 1-10) had a β = .07 (SE .13, P = .28), whereas those with the highest pain level (10) had a β = .92 (SE = .24, P = .001).

Discussion

The authors report 3 main findings from this study: Personal characteristics are not associated with experience, interest in, or belief in the efficacy of CAM; despite a large proportion reporting experience with CAM, veterans reported several barriers to using CAM; and the level of pain reported moderated the relationship between health-related self-efficacy and the belief that CAM will help with daily function.

Determining which personal characteristics are associated with CAM perceptions may indicate who is willing to try CAM techniques and who may require additional education or support. Although the authors hypothesized a difference in experience, interest, and belief of efficacy according to patient characteristics, these differences were not demonstrated. Some published research supports an association between white race, female sex, and middle or younger age and use of CAM, but this sample of veterans did not confirm these associations.1,3,6-8

The lack of associations may be related to selection bias, reflected in the relatively high report of baseline use of CAM. Nevertheless, this finding implies that clinicians should not make assumptions about an individual’s experience with CAM or interest in trying a modality. From a policy perspective, the VHA should consider a broad-based approach targeting a general audience or multiple segmented audiences to increase awareness and a trial of CAM for veterans.

Barriers should be considered when introducing CAM into routine clinical care. The current study revealed several important barriers to veterans accessing or trying CAM techniques, including need for guidance, the lack of awareness or access, and cost. The VHA services are often provided at low or no cost to eligible veterans, likely mitigating the cost barrier to a great extent. However, being able to easily access instruction in CAM modalities in a timely manner may be just as important. The authors detected a preference among respondents for classes to learn CAM (46%) vs independently (19%), supported by the commonly endorsed barrier to trying CAM of “I want in-person instruction but can’t find it.” Offering CAM modalities that can be taught in a group or individual setting and later practiced independently may be an appropriate approach to introduce CAM techniques to the largest number of people and encourage uptake. This approach can maximize access while satisfying many veterans’ preferences for in-person instruction. This leverage of skilled practitioner time could be extended for some modalities through remote telehealth participation or on-demand instruction, such as online videos or DVDs, including the SWK.

Chronic pain can be a challenge for patients and clinicians to manage, so the role of CAM in pain management is growing.2,27 The study’s findings suggest that motivating veterans with chronic pain to try CAM may take extra effort by the clinician. Multivariate linear regression modeling showed that respondents with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with their function only if they also had high health-related self-efficacy, whereas those with low pain scores reported this belief even with low self-efficacy. Thus, strong self-efficacy may overpower doubts about CAM that accompany having pain. Conversely, high reported pain levels may reduce self-efficacy and lead to doubts about the benefit of CAM.

In one study, the belief that lifestyle contributes to illness predicted CAM use, which is similar to this study’s finding that health-related self-efficacy predicted CAM use.8 Several other studies examined CAM use and self-efficacy, although usually not self-efficacy for general health management. To promote experimentation with CAM, patients with chronic pain may require interventions targeted to increase self-efficacy related to CAM.

Of the 733 surveys distributed to veterans, 134 (18%) responses were received. More than 60% of the respondents had tried a CAM technique, higher rates than reported by most other CAM utilization studies: U.S. prevalence studies range from 29% to 42% of respondents having tried some CAM technique, and studies of veterans or military personnel range from 37% to 50% having tried CAM.3,5-7 Because these studies asked about CAM generally or about specific practices that do not fully overlap with the independent CAM practices evaluated in the current study, it is difficult to assess how the experiences of the current sample compare with those populations.

Another study asked veterans with multiple sclerosis whether they were interested in trying CAM practices, and 40% responded “yes,” which is similar to 55% in the current study.6 It is possible the rate of experience with CAM is higher in the current study due to self-selection of respondents who were interested in the SWK. Another factor may be that some veterans were recruited from VA mental health clinics where independent CAM practices are more frequently offered.9 It is also possible that there are regional differences in CAM use; this study took place at a single facility in the northeast U.S., although subsequent phases of the SWK project involved more widespread national dissemination, to be reported in the future.

Limitations

Self-selection and low response rate are limitations in this study. Despite the low response rate, the demographic information of the sample generally resembles the population of veterans at VANJHCS for age, sex, era, health status, and presence of mental health problems.24 Of note, the authors received responses from a wide range of veterans in terms of age, military era, and care setting, including some veterans who do not use the VA. However, data are lacking for nonresponders, and the possibility remains that survey respondents self-selected and were more interested in or experienced with CAM than were nonrespondents. Regardless, many findings, including barriers to CAM and the interaction of pain and self-efficacy, are internally valid and are important to consider even if the sample is not representative of the veteran population.

Conclusion

No studies have focused on veteran use of independent CAM practices as defined for this study. These techniques (eg, meditation, qigong) may promote wellness and relieve common symptoms in veterans. The authors’ results suggest that a broad interest in independent CAM practices among veterans exists. The VA and other health care settings should consider implementing classes in these modalities, especially as their reach may be greater than other CAM modalities requiring one-on-one practitioner-patient interaction. Even with broader availability, patients with chronic pain may require extra attention and context to improve or overcome low health-related self-efficacy, maximizing their likelihood of engaging in CAM. This possibility needs to be explored.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the Veterans Affairs Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation, which was not involved in the study design or production of the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the work of Anna Rusiewicz, PhD, in developing the STAR Well-Kit that was disseminated during this study.

1. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, et al. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: results from a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):344-351.

2. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1-23.

3. Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, Müllner M, Kundi M, Kaye AD. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J. 2012;12(1):45-56.

4. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(4):246-252.

5. Smith TC, Ryan MA, Smith B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US Navy and Marine Corps personnel. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:16.

6. Campbell DG, Turner AP, Williams RM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in veterans with multiple sclerosis: prevalence and demographic associations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43(1):99-110.

7. Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and alternative medicine: implications for integrated care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1697-1704.

8. McEachrane-Gross FP, Liebschutz JM, Berlowitz D. Use of selected complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments in veterans with cancer or chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:34.

9. Ezeji-Okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ, Durfee JM. State of care: complementary and alternative medicine in Veterans Health Administration—2011 survey results. Fed Pract. 2013;30(11):14-19.

10. Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(4).

11. Büssing A, Ostermann T, Lüdtke R, Michalsen A. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain. 2012;13(1):1-9.

12. Lee SW, Mancuso CA, Charlson ME. Prospective study of new participants in a community-based mind-body training program. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):760-765.

13. Waelde LC, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. A pilot study of a yoga and meditation intervention for dementia caregiver stress. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(6):677-687.

14. Lee MS, Lee MS, Kim HJ, Choi ES. Effects of qigong on blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other lipid levels in essential hypertension patients. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114(7):777-786.

15. Lee MS, Lim HJ, Lee MS. Impact of qigong exercise on self-efficacy and other cognitive perceptual variables in patients with essential hypertension. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(4):675-680.

16. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, War Related Illness & Injury Study Center. STAR Well-Kit. http://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/WARRELATEDILLNESS/education/STAR/index.asp. Updated September 18, 2015. Accessed July 6, 2016.

17. Benyamini Y, Idler EL, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Positive affect and function as influences on self-assessments of health: expanding our view beyond illness and disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(2):P107-P116.

18. Idler EL, Kasl SV. Self-ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional ability? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(6):S344-S353.

19. Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733-738.

20. Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9(1):9-14.

21. Kroenke K. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621.

22. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256-262.

23. Kim MT, Han HR, Song HJ, et al. A community-based, culturally tailored behavioral intervention for Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(6):986-994.

24. Webel AR, Okonsky J. Psychometric properties of a Symptom Management Self-Efficacy Scale for women living with HIV/AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):549-557.

25. Jain N, Astin JA. Barriers to acceptance: an exploratory study of complementary/alternative medicine disuse. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7(6):689-696.

26. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. VA facilities by state. http://www.va.gov/vetdata. Updated June 3, 2016. Accessed July 6, 2016.

27. Hassett AL, Williams DA. Non-pharmacological treatment of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):299-309.

1. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, et al. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: results from a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):344-351.

2. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1-23.

3. Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, Müllner M, Kundi M, Kaye AD. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J. 2012;12(1):45-56.

4. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(4):246-252.

5. Smith TC, Ryan MA, Smith B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US Navy and Marine Corps personnel. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:16.

6. Campbell DG, Turner AP, Williams RM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in veterans with multiple sclerosis: prevalence and demographic associations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43(1):99-110.

7. Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and alternative medicine: implications for integrated care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1697-1704.

8. McEachrane-Gross FP, Liebschutz JM, Berlowitz D. Use of selected complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments in veterans with cancer or chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:34.

9. Ezeji-Okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ, Durfee JM. State of care: complementary and alternative medicine in Veterans Health Administration—2011 survey results. Fed Pract. 2013;30(11):14-19.

10. Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(4).

11. Büssing A, Ostermann T, Lüdtke R, Michalsen A. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain. 2012;13(1):1-9.

12. Lee SW, Mancuso CA, Charlson ME. Prospective study of new participants in a community-based mind-body training program. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):760-765.

13. Waelde LC, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. A pilot study of a yoga and meditation intervention for dementia caregiver stress. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(6):677-687.

14. Lee MS, Lee MS, Kim HJ, Choi ES. Effects of qigong on blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other lipid levels in essential hypertension patients. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114(7):777-786.

15. Lee MS, Lim HJ, Lee MS. Impact of qigong exercise on self-efficacy and other cognitive perceptual variables in patients with essential hypertension. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(4):675-680.

16. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, War Related Illness & Injury Study Center. STAR Well-Kit. http://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/WARRELATEDILLNESS/education/STAR/index.asp. Updated September 18, 2015. Accessed July 6, 2016.

17. Benyamini Y, Idler EL, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Positive affect and function as influences on self-assessments of health: expanding our view beyond illness and disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(2):P107-P116.

18. Idler EL, Kasl SV. Self-ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional ability? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(6):S344-S353.

19. Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733-738.

20. Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9(1):9-14.

21. Kroenke K. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621.

22. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256-262.

23. Kim MT, Han HR, Song HJ, et al. A community-based, culturally tailored behavioral intervention for Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(6):986-994.

24. Webel AR, Okonsky J. Psychometric properties of a Symptom Management Self-Efficacy Scale for women living with HIV/AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):549-557.

25. Jain N, Astin JA. Barriers to acceptance: an exploratory study of complementary/alternative medicine disuse. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7(6):689-696.