User login

Management of Patients With Treatment-Resistant Metastatic Prostate Cancer (FULL)

Sequencing Therapies

Mark Klein, MD. The last few years, there have been several new trials in prostate cancer for people in a metastatic setting or more advanced local setting, such as the STAMPEDE, LATITUDE, and CHAARTED trials.1-4 In addition, recently a few trials have examined apalutamide and enzalutamide for people who have had PSA (prostate-specific antigen) levels rapidly rising within about 10 months or so. One of the questions that arises is, how do we wrap our heads around sequencing these therapies. Is there a sequence that we should be doing and thinking about upfront and how do the different trials compare?

Julie Graff, MD. It just got more complicated. There was news today (December 20, 2018) that using enzalutamide early on in newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer may have positive results. It is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but for patients who present with metastatic prostate cancer, we may have 4 potential treatments. We could have androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) alone, ADT plus docetaxel, enzalutamide, or abiraterone.

When I see patients in this situation, I talk to them about their options, the pros and cons of each option, and try to cover all the trials that look at these combinations. It can be quite a long visit. I talk to the patient about who benefits most, whether it is patients with high-risk factors or high-volume cancers. Also, I talk with the patient about all the adverse effects (AEs), and I look at my patients’ comorbid conditions and come up with a plan.

I encourage any patient who has high-volume or high-risk disease to consider more than just ADT alone. For many patients, I have been using abiraterone plus ADT. I have a wonderful pharmacist. As a medical oncologist, I can’t do it on my own. I need someone to follow patients’ laboratory results and to be available for medication questions and complications.

Elizabeth Hansen, PharmD. With the increasing number of patients on oral antineoplastics, monitoring patients in the outpatient setting has become an increasing priority and one of my major roles as a pharmacist in the clinic at the Chalmers P. Wylie VA Ambulatory Care Center in Columbus, Ohio. This is especially important as some of these treatments require frequent laboratory monitoring, such as abiraterone with liver function tests every 2 weeks for the first 3 months of treatment and monthly thereafter. Without frequent-follow up it’s easy for these patients to get lost in the shuffle.

Abhishek Solanki, MD. You could argue that a fifth option is prostate-directed radiation for patients who have limited metastases based on the STAMPEDE trial, which we’ve started integrating into our practice at the Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.4

Mark Klein. Do you have a feel for the data and using radiation in oligometastatic (≤ 5 metastatic tumors) disease in prostate cancer and how well that might work?

Abhishek Solanki. The best data we have are from the multi-arm, multistage STAMPEDE trial systemic therapies and local therapy in the setting of high-risk localized disease and metastatic disease.6 The most recent publication looked specifically at the population with newly diagnosed metastatic disease and compared standard ADT (and docetaxel in about 18% of the patients) with or without prostate-directed radiation therapy. There was no survival benefit with radiation in the overall population, but in the subgroup of patients with low metastatic burden, there was an 8% survival benefit at 3 years.

It’s difficult to know what to make of that information because, as we’ve discussed already, there are other systemic therapy options that are being used more and more upfront such as abiraterone. Can you see the same benefit of radiation in that setting? The flip side is that in this study, radiation just targeted the prostate; could survival be improved even more by targeting all sites of disease in patients with oligometastatic disease? These are still open questions in prostate cancer and there are clinical trials attempting to define the clinical benefit of radiation in the metastatic setting for patients with limited metastases.

Mark Klein. How do you select patients for radiation in this particular situation; How do you approach stratification when radiation is started upfront?

Abhishek Solanki. In the STAMPEDE trial, low metastatic burden was defined based on the definition in the CHAARTED trial, which was those patients who did not have ≥ 4 bone metastases with ≥ 1 outside the vertebral bodies or pelvis, and did not have visceral metastases.7 That’s tough, because this definition could be a patient with a solitary bone metastasis but also could include some patients who have involved nodes extending all the way up to the retroperitoneal nodes—that is a fairly heterogeneous population. What we have done at our institution is select patients who have 3 to 5 metastases, administer prostate radiation therapy, and add stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for the other sites of disease, invoking the oligometastasis approach.

We have been doing this more frequently in the last few months. Typically, we’ll do 3 to 5 fractions of SBRT to metastases. For the primary, if the patient chooses SBRT, we’ll take that approach. If the patient chooses a more standard fractionation, we’ll do 20 treatments, but from a logistic perspective, most patients would rather come in for 5 treatments than 20. We also typically would start these patients on systemic hormonal therapy.

Mark Klein. At that point, are they referred back to medical oncology for surveillance?

Abhishek Solanki. Yes, they are followed by medical oncology and radiation oncology, and typically would continue hormonal therapy.

Mark Klein. Julie, how have you thought about presenting the therapeutic options for those patients who would be either eligible for docetaxel with high-bulk disease or abiraterone? Do you find patients prefer one or the other?

Julie Graff. I try to be very open about all the possibilities, and I present both. I don’t just decide for the patient chemotherapy vs abiraterone, but after we talk about it, most of my patients do opt for the abiraterone. I had a patient referred from the community—we are seeing more and more of this because abiraterone is so expensive—whose ejection fraction was about 38%. I said to that patient, “we could do chemotherapy, but we shouldn’t do abiraterone.” But usually it’s not that clear-cut.

Elizabeth Hansen. There was also an update from the STAMPEDE trial published recently comparing upfront abiraterone and prednisone to docetaxel (18 weeks) in advanced or metastatic prostate cancer. Results from this trial indicated a nearly identical overall survival (OS) (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.16; 95% CI, 0.82-1.65; P = .40). However, the failure-free survival (HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.39-0.67; P < .001) and progression-free survival (PFS) (HR= 0.65; 95% CI, 0.0.48-0.88; P = .005) favored abiraterone.8,9 The authors argue that while there was no change in OS, this trial demonstrates an important difference in the pattern of treatment failure.

Julie, do you think there will be any change in the treatment paradigm between docetaxel and abiraterone with this new update?

Julie Graff. I wasn’t that impressed by that study. I do not see it as practice changing, and it makes sense to me that the PFS is different in the 2 arms because we give chemotherapy and take a break vs giving abiraterone indefinitely. For me, there’s not really a shift.

Patients With Rising PSAs

Mark Klein. Let’s discuss the data from the recent studies on enzalutamide and apalutamide for the patients with fast-rising PSAs. In your discussions with other prostate researchers, will this become a standard part of practice or not?

Julie Graff. I was one of the authors on the SPARTAN apalutamide study.10 For a long time, we have had patients without metastatic disease but with a PSA relapse after surgery or radiation; and the PSA levels climb when the cancer becomes resistant to ADT. We haven’t had many options in that setting except to use bicalutamide and some older androgen receptor (AR) antagonists. We used to use estrogen and ketoconazole as well.

But now 2 studies have come out looking at a primary endpoint of metastases-free survival. Patients whose PSA was doubling every 10 months or shorter were randomized to either apalutamide (SPARTAN10) or enzalutamide (PROSPER11), both second-generation AR antagonists. There was a placebo control arm in each of the studies. Both studies found that adding the second-generation AR targeting agent delayed the time to metastatic disease by about 2 years. There is not any signal yet for statistically significant OS benefit, so it is not entirely clear if you could wait for the first metastasis to develop and then give 1 of these treatments and have the same OS benefit.

At the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPORHCS), it took a while to make these drugs available. My fellows were excited to give these drugs right away, but I often counsel patients that we don’t know if the second-generation AR targeting agents will improve survival. They almost certainly will bring down PSAs, which helps with peace of mind, but anything we add to the ADT can cause more AEs.

I have been cautious with second-generation AR antagonists because patients, when they take one of these drugs, are going to be on it for a long time. The FDA has approved those 2 drugs regardless of PSA doubling time, but I would not give it for a PSA doubling time > 10 months. In my practice about a quarter of patients who would qualify for apalutamide or enzalutamide are actually taking one, and the others are monitored closely with computed tomography (CT) and bone scans. When the disease becomes metastatic, then we start those drugs.

Mark Klein. Why 10 months, why not 6 months, a year, or 18 months? Is there reasoning behind that?

Julie Graff. There was a publication by Matthew Smith showing that the PSA doubling time was predictive of the development of metastatic disease and cancer death or prostate cancer death, and that 10 months seemed to be the cutoff between when the prostate cancer was going to become deadly vs not.12 If you actually look at the trial data, I think the PSA doubling time was between 3 and 4 months for the participants, so pretty short.

Adverse Effects

Mark Klein. What are the AEs people are seeing from using apalutamide, enzalutamide, and abiraterone? What are they seeing in their practice vs what is in the studies? When I have had to stop people on abiraterone or drop down the dose, almost always it has been for fatigue. We check liver function tests (LFTs) repeatedly, but I can’t remember ever having to drop down the dose or take it away even for that reason.

Elizabeth Hansen.

Mark Klein. At the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS) when apalutamide first came out, for the PSA rapid doubling, there had already been an abstract presenting the enzalutamide data. We have chosen to recommend enzalutamide as our choice for the people with PSA doubling based on the cost. It’s significantly cheaper for the VA. Between the 2 papers there is very little difference in the efficacy data. I’m wondering what other sites have done with regard to that specific point at their VAs?

Elizabeth Hansen. In Columbus, we prefer to use either abiraterone and enzalutamide because they’re essentially cost neutral. However, this may change with generic abiraterone coming to market. Apalutamide is really cost prohibitive currently.

Julie Graff. I agree.

Patient Education

Mark Klein. At MVAHCS, the navigators handle a lot of upfront education. We have 3 navigators, including Kathleen Nelson who is on this roundtable. She works with patients and provides much of the patient education. How have you handled education for patients?

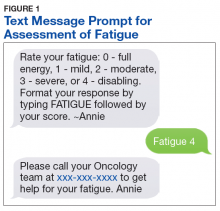

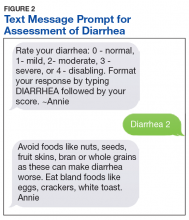

Kathleen Nelson. For the most part, our pharmacists do the drug-specific education for the oral agents, and the nurse navigators provide more generic education. We did a trial for patients on IV therapies. We learned that patients really don’t report in much detail, but if you call and ask them specific questions, then you can tease out some more detail.

Elizabeth Hansen. It is interesting that every site is different. One of my main roles is oral antineoplastic monitoring, which includes many patients on enzalutamide or abiraterone. At least initially with these patients, I try to follow them closely—abiraterone more so than enzalutamide. I typically call every 2 to 4 weeks, in between clinic visits, to follow up the laboratory tests and manage the AEs. I always try to ask direct and open-ended questions: How often are you checking your blood pressure? What is your current weight? How has your energy level changed since therapy initiation?

The VA telehealth system is amazing. For patients who need to monitor blood pressure regularly, it’s really nice for them to have those numbers come directly back to me in CPRS (Computerized Patient Record System). That has worked wonders for some of our patients to get them through therapy.

Mark Klein. What do you tend to use when the prostate cancer is progressing for a patient? And how do you determine that progression? Some studies will use PSA rise only as a marker for progression. Other studies have not used PSA rise as the only marker for progression and oftentimes require some sort of bone scan criteria or CT imaging criteria for progression.

Julie Graff. We have a limited number of treatment options. Providers typically use enzalutamide or abiraterone as there is a high degree of resistance between the 2. Then there is chemotherapy and then radium, which quite a few people don’t qualify for. We need to be very thoughtful when we change treatments. I look at the 3 factors of biochemical progression or response—PSA, radiographic progression, and clinical progression. If I don’t see 2 out of 3, I typically don’t change treatments. Then after enzalutamide or abiraterone, I wait until there are cancer-related symptoms before I consider chemotherapy and closely monitor my patients.

Imaging Modalities

Abhishek Solanki. Over the last few years the Hines VA Hospital has used fluciclovine positron emission tomography (PET), which is one of the novel imaging modalities for prostate cancer. Really the 2 novel imaging modalities that have gained the most excitement are prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET and fluciclovine PET. Fluciclovine PET is based on a synthetic amino acid that’s taken up in multiple tissues, including prostate cancer. It has changed our practice in the localized setting for patients who have developed recurrence after radiation or radical prostatectomy. We have incorporated the scan into our workup of patients with recurrent disease, which can give us some more information at lower PSAs than historically we could get with CT, bone scan, or magnetic resonance imaging.

Our medical oncologists have started using it more and more as well. We are getting a lot of patients who have a negative CT or bone scan but have a positive fluciclovine PET. There are a few different disease settings where that becomes relevant. In patients who develop biochemical recurrence after radiation or salvage radiation after radical, we are finding that a lot of these patients who have no CT or bone scan findings of disease ultimately are found to have a PET-positive lesion. Sometimes it’s difficult to know how best to help patients with PET-only disease. Should you target the disease with an oligometastasis approach or just pursue systemic therapy or surveillance? It is challenging but more and more we are moving toward metastasis-directed therapy. There are multiple randomized trials in progress testing whether metastasis-directed therapy to the PET areas of recurrence can improve outcomes or delay systemic ADT. The STOMP trial randomized surveillance vs SBRT or surgery for patients with oligometastatic disease that showed improvement in biochemical control and ADT-free survival.13 However this was a small trial that tried to identify a signal. More definitive trials are necessary.

The other setting where we have found novel PET imaging to be helpful is in patients who have become castration resistant but don’t have clear metastases on conventional imaging. We’re identifying more patients who have only a few sites of progression, and we’ll pursue metastasis-directed therapy to those areas to try to get more mileage out of the systemic therapy that the patient is currently on and to try to avoid having to switch to the next line with the idea that, potentially, the progression site is just a limited clone that is progressing despite the current systemic therapy.

Mark Klein. I find that to be a very attractive approach. I’m assuming you do that for any systemic therapy where people have maybe 1 or 2 sites and they do not have a big PSA jump. Do you have a number of sites that you’re willing to radiate? And then, when you do that, what radiation fractionation and dosing do you use? Is there any observational data behind that for efficacy?

Abhishek Solanki. It is a patient by patient decision. Some patients, if they have a very rapid pace of progression shortly after starting systemic therapy and metastases have grown in several areas, we think that perhaps this person may benefit less from aggressive local therapy. But if it’s somebody who has been on systemic therapy for a while and has up to 3 sites of disease growth, we consider SBRT for oligoprogressive disease. Typically, we’ll use SBRT, which delivers a high dose of radiation over 3 to 5 treatments. With SBRT you can give a higher biologic dose and use more sophisticated treatment machines and image guidance for treatments to focus the radiation on the tumor area and limit exposure to normal tissue structures.

In prostate cancer to the primary site, we will typically do around 35 to 40 Gy in 5 fractions. For metastases, it depends on the site. If it’s in the lung, typically we will do 3 to 5 treatments, giving approximately 50 to 60 Gy in that course. In the spine, we use lower doses near the spinal cord and the cauda equina, typically about 30 Gy in 3 fractions. In the liver, similar to the lung, we’ll typically do 50-54 Gy in 3-5 fractions. There aren’t a lot of high-level data guiding the optimal dose/fractionation to metastases, but these are the doses we’ll use for various malignancies.

Treatment Options for Patients With Adverse Events

Mark Klein. I was just reviewing the 2004 study that randomized patients to mitoxantrone or docetaxel for up to 10 cycles.14,15 Who are good candidates for docetaxel after they have exhausted abiraterone and enzalutamide? How long do you hold to the 10-cycle rule, or do you go beyond that if they’re doing well? And if they’re not a good candidate, what are some options?

Julie Graff. The best candidates are those who are having a cancer-related AE, particularly pain, because docetaxel only improves survival over mitoxantrone by about 2.5 months. I don’t talk to patients about it as though it is a life extender, but it seems to help control pain—about 70% of patients benefited in terms of pain or some other cancer-related symptom.14

I have a lot of patients who say, “Never will I do chemotherapy.” I refer those patients to hospice, or if they’re appropriate for radium-223, I consider that. I typically give about 6 cycles of chemotherapy and then see how they’re doing. In some patients, the cancer just doesn’t respond to it.

I do tell patients about the papers that you mentioned, the 2 studies of docetaxel vs mitoxantrone where they use about 10 cycles, and some of my patients go all 10.14,15 Sometimes we have to stop because of neuropathy or some other AE. I believe in taking breaks and that you can probably start it later.

Elizabeth Hansen. I agree, our practice is similar. A lot of our patients are not very interested in chemotherapy. You have to take into consideration their ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) status, their goals, and quality of life when talking to them about these medications. And a lot of them tend to choose more of a palliative route. Depending on their AEs and how things are going, we will dose reduce, hold treatment, or give treatment holidays.

Mark Klein. If patients are progressing on docetaxel, what are options that people would use? Radium-223 certainly is available for patients with nonvisceral metastases, as well as cabazitaxel, mitoxantrone, estramustine and other older drugs.

Julie Graff. We have some clinical trials for patients postdocetaxel. We have the TRITON2 and TRITON3 studies open at the VA. (NCT02952534 and NCT02975934, respectively) A lot of patients would get a biopsy, and we’d look for a BRCA 1 or 2 and ATM mutation. For those patients who don’t have those mutations—and maybe 80% of them don’t—we talk about radium-223 for the patients without visceral metastases and bone pain. I have had a fair number of patients go on cabazitaxel, but I have not used mitoxantrone since cabazitaxel came out. It’s not off the table, but it hasn’t shown improvement in survival.

Elizabeth Hansen. One of our challenges, because we’re an ambulatory care center, is that we are unable to give radium-223 in house, and these services have to be sent out to a non-VA facility. It is doable, but it takes more legwork and organization on our part.

Julie Graff. We have not had radium-223, although we’re working to get that online. And we are physically connected to Oregon Health Science University (OHSU), so we send our patients there for radium. It is a pain because the doctors at OHSU don’t have CPRS access. I’m often in the middle of making sure the complete blood counts (CBCs) are sent to OHSU and to get my patients their treatments.

Mark Klein. The Minneapolis VAMC has radium-223 on site, and we have used it for patients whose cancer has progressed while on docetaxel without visceral metastases. Katie, have you had an opportunity to coordinate that care for patients?

Kathleen Nelson. Radium is administered at our facility by one of our nuclear medicine physicians. A complete blood count is checked at least 3 days prior to the infusion date but no sooner than 6 days. Due to the cost of the material, ordering without knowing the patient’s counts are within a safe range to administer is prohibitive. This adds an additional burden of 2 visits (lab with return visit) to the patient. We have treated 12 patients. Four patients stopped treatment prior to completing the 6 planned treatments citing debilitating fatigue and/or nonresolution of symptoms as their reason to stop treatment. One patient died. The 7 remaining patients subjectively reported varying degrees of pain relief.

Elizabeth Hansen. Another thing to mention is the lack of a PSA response from radium-223 as well. Patients are generally very diligent about monitoring their PSA, so this can be a bit distressing.

Mark Klein. Julie, have you noticed a PSA flare with radium-223? I know it has been reported.

Julie Graff. I haven’t. But I put little stock in PSAs in these patients. I spend 20 minutes explaining to patients that the PSA is not helpful in determining whether or not the radium is working. I tell them that the bone marker alkaline phosphatase may decrease. And I think it’s important to note, too, that radium-223 is not a treatment we have on the shelf. We order it from Denver I believe. It is weight based, and it takes 5 days to get.

Clinical Trials

Mark Klein. That leads us into clinical trials. What is the role for precision oncology in prostate cancer right now, specifically looking at particular panels? One would be the DNA repair enzyme-based genes and/or also the AR variants and any other markers.

Elizabeth Hansen. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network came out with a statement recommending germ-line and somatic-mutation testing in all patients with metastatic prostate cancer. This highlights the need to offer patients the availability of clinical trials.

Julie Graff. I agree. We occasionally get to a place in the disease where patients are feeling fine, but we don’t have anything else to offer. The studies by Robinson16 and then Matteo17 showed that (a) these DNA repair defects are present in about a quarter of patients; and (b) that PARP inhibitors can help these patients. At least it has an anticancer effect.

What’s interesting is that we have TRITON2, and TRITON3, which are sponsored by Clovis,for patients with BRCA 1/2 and ATM mutations and using the PARP-inhibitor rucaparib. Based on the data we have available, we thought a quarter of patients would have the mutation in the tumor, but they’re finding that it is more like 10% to 15%. They are screening many patients but not finding it.

I agree that clinical trials are the way to go. I am hopeful that we’ll get more treatments based on molecular markers. The approval for pembrolizumab in any tumor type with microsatellite instability is interesting, but in prostate cancer, I believe that’s about 3%. I haven’t seen anyone qualify for pembrolizumab based on that. Another plug for clinical trials: Let’s learn more and offer our patients potentially beneficial treatments earlier.

Mark Klein. The first interim analysis from the TRITON2 study found about 12% of patients had alterations in BRCA 1/2. But in those that met the RECIST criteria, they were able to have evaluable disease via that standard with about a 44% response rate so far and a 51% PSA response rate. It is promising data, but it’s only 85 patients so far. We’ll know more because the TRITON2 study is of a more pretreated population than the TRITION3 study at this point. Are there any data on precision medicine and radiation in prostate cancer?

Abhishek Solanki. In the prostate cancer setting, there are not a lot of emerging data specifically looking at using precision oncology biomarkers to help guide decisions in radiation therapy. For example, genomic classifiers, like GenomeDx Decipher (Vancouver, BC) and Myriad Genetics Prolaris (Salt Lake City, UT) are increasingly being utilized in patients with localized disease. Decipher can help predict the risk of recurrence after radical prostatectomy. The difficulty is that there are limited data that show that by using these genomic classifiers, one can improve outcomes in patients over traditional clinical characteristics.

There are 2 trials currently ongoing through NRG Oncology that are using Decipher. The GU002 is a trial for patients who had a radical prostatectomy and had a postoperative PSA that never nadired below 0.2. These patients are randomized between salvage radiation with hormone therapy with or without docetaxel. This trial is collecting Decipher results for patients enrolled in the study. The GU006 is a trial for a slightly more favorable group of patients who do nadir but still have biochemical recurrence and relatively low PSAs. This trial randomizes between radiotherapy alone and radiotherapy and 6 months of apalutamide, stratifying patients based on Decipher results, specially differentiating between patients who have a luminal vs basal subtype of prostate cancer. There are data that suggest that patients who have a luminal subtype may benefit more from the combination of radiation and hormone therapy vs patients who have basal subtype.18 However this hasn’t been validated in a prospective setting, and that’s what this trial will hopefully do.

Immunotherapies

Mark Klein. Outside of prostate cancer, there has been a lot of research trying to determine how to improve PD-L1 expression. Where are immunotherapy trials moving? How radiation might play a role in conjunction with immunotherapy.

Julie Graff. Two phase 3 studies did not show statistically improved survival or statistically significant survival improvement on ipilimumab, an immunotherapy agent that targets CTLA4. Some early studies of the PD-1 drugs nivolumab and pembrolizumab did not show much response with monotherapy. Despite the negative phase 3 studies for ipilimumab, we periodically see exceptional responses.

In prostate cancer, enzalutamide is FDA approved. And there’s currently a phase 3 study of the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab plus enzalutamide in patients who have progressed on abiraterone. That trial is fully accrued, bu

I just received a Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award to open a VA-only study looking at fecal microbiota transplant from responders to nonresponders to see how manipulating host factors can increase potential responses to PD-1 inhibition.

Abhishek Solanki. The classic mechanism by which radiation therapy works is direct DNA damage and indirect DNA damage through hydroxyl radicals that leads to cytotoxicity. But preclinical and clinical data suggest that radiation therapy can augment the local and systemic immunotherapy response. The radiation oncologist’s dream is what is called the abscopal effect, which is the idea that when you treat one site of disease with radiation, it can induce a response at other sites that didn’t get radiation therapy through reactivation of the immune system. I like to think of the abscopal effect like bigfoot—it’s elusive. However, it seems that the setting it is most likely to happen in is in combination with immunotherapy.

One of the ways that radiation fails locally is that it can upregulate PD-1 expression, and as a result, you can have progression of the tumor because of local immune suppression. We know that T cells are important for the activity of radiation therapy. If you combine checkpoint inhibition with radiation therapy, you can not only have better local control in the area of the tumor, but perhaps you can release tumor antigens that will then induce a systemic response.

The other potential mechanism by which radiation may work synergistically with immunotherapy is as a debulking agent. There are some data that suggest that the ratio of T-cell reinvigoration to bulk of disease, or the volume of tumor burden, is important. That is, having T-cell reinvigoration may not be sufficient to have a response to immunotherapy in patients with a large burden of disease. By using radiation to debulk disease, perhaps you could help make checkpoint inhibition more effective. Ultimately, in the setting of prostate cancer, there are not a lot of data yet showing meaningful benefits with the combination of immunotherapy and radiotherapy, but there are trials that are ongoing that will educate on potential synergy.

Pharmacy

Julie Graff. Before we end I want to make sure that we applaud the amazing pharmacists and patient care navigation teams in the VA who do such a great job of getting veterans the appropriate treatment expeditiously and keeping them safe. It’s something that is truly unique to the VA. And I want to thank the people on this call who do this every day.

Elizabeth Hansen. Thank you Julie. Compared with working in the community, at the VA I’m honestly amazed by the ease of access to these medications for our patients. Being able to deliver medications sometimes the same day to the patient is just not something that happens in the community. It’s nice to see that our veterans are getting cared for in that manner.

Author disclosures

Dr. Solanki participated in advisory boards for Blue Earth Diagnostics’ fluciclovine PET and was previously paid as a consultant. Dr. Graff is a consultant for Sanofi (docetaxel) and Astellas (enzalutamide), and has received research funding (no personal funding)from Sanofi, Merck (pembrolizumab), Astellas, and Jannsen (abiraterone, apalutamide). The other authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):338-351.

2. James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;387(10024):1163-1177.

3. Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al; LATITUDE Investigators. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):352-360.

4. Kyriakopoulos CE, Chen YH, Carducci MA, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: long-term survival analysis of the randomized Phase III E3805 CHAARTED trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1080-1087.

5. Tosoian JJ, Gorin MA, Ross AE, Pienta KJ, Tran PT, Schaeffer EM. Oligometastatic prostate cancer: definitions, clinical outcomes, and treatment considerations. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14(1):15-25.

6. Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, et al; Systemic Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Prostate cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy (STAMPEDE) investigators. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10162):2353-2366.

7. Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):737-746.

8. Feyerabend S, Saad F, Li T, et al. Survival benefit, disease progression and quality-of-life outcomes of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus docetaxel in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:78-87.

9. Sydes MR, Spears MR, Mason MD, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Adding abiraterone or docetaxel to long-term hormone therapy for prostate cancer: directly randomised data from the STAMPEDE multi-arm, multi-stage platform protocol. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(5):1235-1248.

10. Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al; SPARTAN Investigators. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1408-1418.

11. Hussain M, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Enzalutamide in men with nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2465-2474.

12. Smith MR, Kabbinavar F, Saad F, et al. Natural history of rising serum prostate-specific antigen in men with castrate nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2918-2925.

13. Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, et al. Surveillance or metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer recurrence: a prospective, randomized, multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):446-453.

14. Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1513-1520.

15. Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al; TAX 327 Investigators. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1502-1512.

16. Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161(5):1215-1228.

17. Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1697-1708.

18. Zhao SG, Chang SL, Erho N, et al. Associations of luminal and basal subtyping of prostate cancer with prognosis and response to androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(12):1663-1672.

Sequencing Therapies

Mark Klein, MD. The last few years, there have been several new trials in prostate cancer for people in a metastatic setting or more advanced local setting, such as the STAMPEDE, LATITUDE, and CHAARTED trials.1-4 In addition, recently a few trials have examined apalutamide and enzalutamide for people who have had PSA (prostate-specific antigen) levels rapidly rising within about 10 months or so. One of the questions that arises is, how do we wrap our heads around sequencing these therapies. Is there a sequence that we should be doing and thinking about upfront and how do the different trials compare?

Julie Graff, MD. It just got more complicated. There was news today (December 20, 2018) that using enzalutamide early on in newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer may have positive results. It is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but for patients who present with metastatic prostate cancer, we may have 4 potential treatments. We could have androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) alone, ADT plus docetaxel, enzalutamide, or abiraterone.

When I see patients in this situation, I talk to them about their options, the pros and cons of each option, and try to cover all the trials that look at these combinations. It can be quite a long visit. I talk to the patient about who benefits most, whether it is patients with high-risk factors or high-volume cancers. Also, I talk with the patient about all the adverse effects (AEs), and I look at my patients’ comorbid conditions and come up with a plan.

I encourage any patient who has high-volume or high-risk disease to consider more than just ADT alone. For many patients, I have been using abiraterone plus ADT. I have a wonderful pharmacist. As a medical oncologist, I can’t do it on my own. I need someone to follow patients’ laboratory results and to be available for medication questions and complications.

Elizabeth Hansen, PharmD. With the increasing number of patients on oral antineoplastics, monitoring patients in the outpatient setting has become an increasing priority and one of my major roles as a pharmacist in the clinic at the Chalmers P. Wylie VA Ambulatory Care Center in Columbus, Ohio. This is especially important as some of these treatments require frequent laboratory monitoring, such as abiraterone with liver function tests every 2 weeks for the first 3 months of treatment and monthly thereafter. Without frequent-follow up it’s easy for these patients to get lost in the shuffle.

Abhishek Solanki, MD. You could argue that a fifth option is prostate-directed radiation for patients who have limited metastases based on the STAMPEDE trial, which we’ve started integrating into our practice at the Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.4

Mark Klein. Do you have a feel for the data and using radiation in oligometastatic (≤ 5 metastatic tumors) disease in prostate cancer and how well that might work?

Abhishek Solanki. The best data we have are from the multi-arm, multistage STAMPEDE trial systemic therapies and local therapy in the setting of high-risk localized disease and metastatic disease.6 The most recent publication looked specifically at the population with newly diagnosed metastatic disease and compared standard ADT (and docetaxel in about 18% of the patients) with or without prostate-directed radiation therapy. There was no survival benefit with radiation in the overall population, but in the subgroup of patients with low metastatic burden, there was an 8% survival benefit at 3 years.

It’s difficult to know what to make of that information because, as we’ve discussed already, there are other systemic therapy options that are being used more and more upfront such as abiraterone. Can you see the same benefit of radiation in that setting? The flip side is that in this study, radiation just targeted the prostate; could survival be improved even more by targeting all sites of disease in patients with oligometastatic disease? These are still open questions in prostate cancer and there are clinical trials attempting to define the clinical benefit of radiation in the metastatic setting for patients with limited metastases.

Mark Klein. How do you select patients for radiation in this particular situation; How do you approach stratification when radiation is started upfront?

Abhishek Solanki. In the STAMPEDE trial, low metastatic burden was defined based on the definition in the CHAARTED trial, which was those patients who did not have ≥ 4 bone metastases with ≥ 1 outside the vertebral bodies or pelvis, and did not have visceral metastases.7 That’s tough, because this definition could be a patient with a solitary bone metastasis but also could include some patients who have involved nodes extending all the way up to the retroperitoneal nodes—that is a fairly heterogeneous population. What we have done at our institution is select patients who have 3 to 5 metastases, administer prostate radiation therapy, and add stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for the other sites of disease, invoking the oligometastasis approach.

We have been doing this more frequently in the last few months. Typically, we’ll do 3 to 5 fractions of SBRT to metastases. For the primary, if the patient chooses SBRT, we’ll take that approach. If the patient chooses a more standard fractionation, we’ll do 20 treatments, but from a logistic perspective, most patients would rather come in for 5 treatments than 20. We also typically would start these patients on systemic hormonal therapy.

Mark Klein. At that point, are they referred back to medical oncology for surveillance?

Abhishek Solanki. Yes, they are followed by medical oncology and radiation oncology, and typically would continue hormonal therapy.

Mark Klein. Julie, how have you thought about presenting the therapeutic options for those patients who would be either eligible for docetaxel with high-bulk disease or abiraterone? Do you find patients prefer one or the other?

Julie Graff. I try to be very open about all the possibilities, and I present both. I don’t just decide for the patient chemotherapy vs abiraterone, but after we talk about it, most of my patients do opt for the abiraterone. I had a patient referred from the community—we are seeing more and more of this because abiraterone is so expensive—whose ejection fraction was about 38%. I said to that patient, “we could do chemotherapy, but we shouldn’t do abiraterone.” But usually it’s not that clear-cut.

Elizabeth Hansen. There was also an update from the STAMPEDE trial published recently comparing upfront abiraterone and prednisone to docetaxel (18 weeks) in advanced or metastatic prostate cancer. Results from this trial indicated a nearly identical overall survival (OS) (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.16; 95% CI, 0.82-1.65; P = .40). However, the failure-free survival (HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.39-0.67; P < .001) and progression-free survival (PFS) (HR= 0.65; 95% CI, 0.0.48-0.88; P = .005) favored abiraterone.8,9 The authors argue that while there was no change in OS, this trial demonstrates an important difference in the pattern of treatment failure.

Julie, do you think there will be any change in the treatment paradigm between docetaxel and abiraterone with this new update?

Julie Graff. I wasn’t that impressed by that study. I do not see it as practice changing, and it makes sense to me that the PFS is different in the 2 arms because we give chemotherapy and take a break vs giving abiraterone indefinitely. For me, there’s not really a shift.

Patients With Rising PSAs

Mark Klein. Let’s discuss the data from the recent studies on enzalutamide and apalutamide for the patients with fast-rising PSAs. In your discussions with other prostate researchers, will this become a standard part of practice or not?

Julie Graff. I was one of the authors on the SPARTAN apalutamide study.10 For a long time, we have had patients without metastatic disease but with a PSA relapse after surgery or radiation; and the PSA levels climb when the cancer becomes resistant to ADT. We haven’t had many options in that setting except to use bicalutamide and some older androgen receptor (AR) antagonists. We used to use estrogen and ketoconazole as well.

But now 2 studies have come out looking at a primary endpoint of metastases-free survival. Patients whose PSA was doubling every 10 months or shorter were randomized to either apalutamide (SPARTAN10) or enzalutamide (PROSPER11), both second-generation AR antagonists. There was a placebo control arm in each of the studies. Both studies found that adding the second-generation AR targeting agent delayed the time to metastatic disease by about 2 years. There is not any signal yet for statistically significant OS benefit, so it is not entirely clear if you could wait for the first metastasis to develop and then give 1 of these treatments and have the same OS benefit.

At the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPORHCS), it took a while to make these drugs available. My fellows were excited to give these drugs right away, but I often counsel patients that we don’t know if the second-generation AR targeting agents will improve survival. They almost certainly will bring down PSAs, which helps with peace of mind, but anything we add to the ADT can cause more AEs.

I have been cautious with second-generation AR antagonists because patients, when they take one of these drugs, are going to be on it for a long time. The FDA has approved those 2 drugs regardless of PSA doubling time, but I would not give it for a PSA doubling time > 10 months. In my practice about a quarter of patients who would qualify for apalutamide or enzalutamide are actually taking one, and the others are monitored closely with computed tomography (CT) and bone scans. When the disease becomes metastatic, then we start those drugs.

Mark Klein. Why 10 months, why not 6 months, a year, or 18 months? Is there reasoning behind that?

Julie Graff. There was a publication by Matthew Smith showing that the PSA doubling time was predictive of the development of metastatic disease and cancer death or prostate cancer death, and that 10 months seemed to be the cutoff between when the prostate cancer was going to become deadly vs not.12 If you actually look at the trial data, I think the PSA doubling time was between 3 and 4 months for the participants, so pretty short.

Adverse Effects

Mark Klein. What are the AEs people are seeing from using apalutamide, enzalutamide, and abiraterone? What are they seeing in their practice vs what is in the studies? When I have had to stop people on abiraterone or drop down the dose, almost always it has been for fatigue. We check liver function tests (LFTs) repeatedly, but I can’t remember ever having to drop down the dose or take it away even for that reason.

Elizabeth Hansen.

Mark Klein. At the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS) when apalutamide first came out, for the PSA rapid doubling, there had already been an abstract presenting the enzalutamide data. We have chosen to recommend enzalutamide as our choice for the people with PSA doubling based on the cost. It’s significantly cheaper for the VA. Between the 2 papers there is very little difference in the efficacy data. I’m wondering what other sites have done with regard to that specific point at their VAs?

Elizabeth Hansen. In Columbus, we prefer to use either abiraterone and enzalutamide because they’re essentially cost neutral. However, this may change with generic abiraterone coming to market. Apalutamide is really cost prohibitive currently.

Julie Graff. I agree.

Patient Education

Mark Klein. At MVAHCS, the navigators handle a lot of upfront education. We have 3 navigators, including Kathleen Nelson who is on this roundtable. She works with patients and provides much of the patient education. How have you handled education for patients?

Kathleen Nelson. For the most part, our pharmacists do the drug-specific education for the oral agents, and the nurse navigators provide more generic education. We did a trial for patients on IV therapies. We learned that patients really don’t report in much detail, but if you call and ask them specific questions, then you can tease out some more detail.

Elizabeth Hansen. It is interesting that every site is different. One of my main roles is oral antineoplastic monitoring, which includes many patients on enzalutamide or abiraterone. At least initially with these patients, I try to follow them closely—abiraterone more so than enzalutamide. I typically call every 2 to 4 weeks, in between clinic visits, to follow up the laboratory tests and manage the AEs. I always try to ask direct and open-ended questions: How often are you checking your blood pressure? What is your current weight? How has your energy level changed since therapy initiation?

The VA telehealth system is amazing. For patients who need to monitor blood pressure regularly, it’s really nice for them to have those numbers come directly back to me in CPRS (Computerized Patient Record System). That has worked wonders for some of our patients to get them through therapy.

Mark Klein. What do you tend to use when the prostate cancer is progressing for a patient? And how do you determine that progression? Some studies will use PSA rise only as a marker for progression. Other studies have not used PSA rise as the only marker for progression and oftentimes require some sort of bone scan criteria or CT imaging criteria for progression.

Julie Graff. We have a limited number of treatment options. Providers typically use enzalutamide or abiraterone as there is a high degree of resistance between the 2. Then there is chemotherapy and then radium, which quite a few people don’t qualify for. We need to be very thoughtful when we change treatments. I look at the 3 factors of biochemical progression or response—PSA, radiographic progression, and clinical progression. If I don’t see 2 out of 3, I typically don’t change treatments. Then after enzalutamide or abiraterone, I wait until there are cancer-related symptoms before I consider chemotherapy and closely monitor my patients.

Imaging Modalities

Abhishek Solanki. Over the last few years the Hines VA Hospital has used fluciclovine positron emission tomography (PET), which is one of the novel imaging modalities for prostate cancer. Really the 2 novel imaging modalities that have gained the most excitement are prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET and fluciclovine PET. Fluciclovine PET is based on a synthetic amino acid that’s taken up in multiple tissues, including prostate cancer. It has changed our practice in the localized setting for patients who have developed recurrence after radiation or radical prostatectomy. We have incorporated the scan into our workup of patients with recurrent disease, which can give us some more information at lower PSAs than historically we could get with CT, bone scan, or magnetic resonance imaging.

Our medical oncologists have started using it more and more as well. We are getting a lot of patients who have a negative CT or bone scan but have a positive fluciclovine PET. There are a few different disease settings where that becomes relevant. In patients who develop biochemical recurrence after radiation or salvage radiation after radical, we are finding that a lot of these patients who have no CT or bone scan findings of disease ultimately are found to have a PET-positive lesion. Sometimes it’s difficult to know how best to help patients with PET-only disease. Should you target the disease with an oligometastasis approach or just pursue systemic therapy or surveillance? It is challenging but more and more we are moving toward metastasis-directed therapy. There are multiple randomized trials in progress testing whether metastasis-directed therapy to the PET areas of recurrence can improve outcomes or delay systemic ADT. The STOMP trial randomized surveillance vs SBRT or surgery for patients with oligometastatic disease that showed improvement in biochemical control and ADT-free survival.13 However this was a small trial that tried to identify a signal. More definitive trials are necessary.

The other setting where we have found novel PET imaging to be helpful is in patients who have become castration resistant but don’t have clear metastases on conventional imaging. We’re identifying more patients who have only a few sites of progression, and we’ll pursue metastasis-directed therapy to those areas to try to get more mileage out of the systemic therapy that the patient is currently on and to try to avoid having to switch to the next line with the idea that, potentially, the progression site is just a limited clone that is progressing despite the current systemic therapy.

Mark Klein. I find that to be a very attractive approach. I’m assuming you do that for any systemic therapy where people have maybe 1 or 2 sites and they do not have a big PSA jump. Do you have a number of sites that you’re willing to radiate? And then, when you do that, what radiation fractionation and dosing do you use? Is there any observational data behind that for efficacy?

Abhishek Solanki. It is a patient by patient decision. Some patients, if they have a very rapid pace of progression shortly after starting systemic therapy and metastases have grown in several areas, we think that perhaps this person may benefit less from aggressive local therapy. But if it’s somebody who has been on systemic therapy for a while and has up to 3 sites of disease growth, we consider SBRT for oligoprogressive disease. Typically, we’ll use SBRT, which delivers a high dose of radiation over 3 to 5 treatments. With SBRT you can give a higher biologic dose and use more sophisticated treatment machines and image guidance for treatments to focus the radiation on the tumor area and limit exposure to normal tissue structures.

In prostate cancer to the primary site, we will typically do around 35 to 40 Gy in 5 fractions. For metastases, it depends on the site. If it’s in the lung, typically we will do 3 to 5 treatments, giving approximately 50 to 60 Gy in that course. In the spine, we use lower doses near the spinal cord and the cauda equina, typically about 30 Gy in 3 fractions. In the liver, similar to the lung, we’ll typically do 50-54 Gy in 3-5 fractions. There aren’t a lot of high-level data guiding the optimal dose/fractionation to metastases, but these are the doses we’ll use for various malignancies.

Treatment Options for Patients With Adverse Events

Mark Klein. I was just reviewing the 2004 study that randomized patients to mitoxantrone or docetaxel for up to 10 cycles.14,15 Who are good candidates for docetaxel after they have exhausted abiraterone and enzalutamide? How long do you hold to the 10-cycle rule, or do you go beyond that if they’re doing well? And if they’re not a good candidate, what are some options?

Julie Graff. The best candidates are those who are having a cancer-related AE, particularly pain, because docetaxel only improves survival over mitoxantrone by about 2.5 months. I don’t talk to patients about it as though it is a life extender, but it seems to help control pain—about 70% of patients benefited in terms of pain or some other cancer-related symptom.14

I have a lot of patients who say, “Never will I do chemotherapy.” I refer those patients to hospice, or if they’re appropriate for radium-223, I consider that. I typically give about 6 cycles of chemotherapy and then see how they’re doing. In some patients, the cancer just doesn’t respond to it.

I do tell patients about the papers that you mentioned, the 2 studies of docetaxel vs mitoxantrone where they use about 10 cycles, and some of my patients go all 10.14,15 Sometimes we have to stop because of neuropathy or some other AE. I believe in taking breaks and that you can probably start it later.

Elizabeth Hansen. I agree, our practice is similar. A lot of our patients are not very interested in chemotherapy. You have to take into consideration their ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) status, their goals, and quality of life when talking to them about these medications. And a lot of them tend to choose more of a palliative route. Depending on their AEs and how things are going, we will dose reduce, hold treatment, or give treatment holidays.

Mark Klein. If patients are progressing on docetaxel, what are options that people would use? Radium-223 certainly is available for patients with nonvisceral metastases, as well as cabazitaxel, mitoxantrone, estramustine and other older drugs.

Julie Graff. We have some clinical trials for patients postdocetaxel. We have the TRITON2 and TRITON3 studies open at the VA. (NCT02952534 and NCT02975934, respectively) A lot of patients would get a biopsy, and we’d look for a BRCA 1 or 2 and ATM mutation. For those patients who don’t have those mutations—and maybe 80% of them don’t—we talk about radium-223 for the patients without visceral metastases and bone pain. I have had a fair number of patients go on cabazitaxel, but I have not used mitoxantrone since cabazitaxel came out. It’s not off the table, but it hasn’t shown improvement in survival.

Elizabeth Hansen. One of our challenges, because we’re an ambulatory care center, is that we are unable to give radium-223 in house, and these services have to be sent out to a non-VA facility. It is doable, but it takes more legwork and organization on our part.

Julie Graff. We have not had radium-223, although we’re working to get that online. And we are physically connected to Oregon Health Science University (OHSU), so we send our patients there for radium. It is a pain because the doctors at OHSU don’t have CPRS access. I’m often in the middle of making sure the complete blood counts (CBCs) are sent to OHSU and to get my patients their treatments.

Mark Klein. The Minneapolis VAMC has radium-223 on site, and we have used it for patients whose cancer has progressed while on docetaxel without visceral metastases. Katie, have you had an opportunity to coordinate that care for patients?

Kathleen Nelson. Radium is administered at our facility by one of our nuclear medicine physicians. A complete blood count is checked at least 3 days prior to the infusion date but no sooner than 6 days. Due to the cost of the material, ordering without knowing the patient’s counts are within a safe range to administer is prohibitive. This adds an additional burden of 2 visits (lab with return visit) to the patient. We have treated 12 patients. Four patients stopped treatment prior to completing the 6 planned treatments citing debilitating fatigue and/or nonresolution of symptoms as their reason to stop treatment. One patient died. The 7 remaining patients subjectively reported varying degrees of pain relief.

Elizabeth Hansen. Another thing to mention is the lack of a PSA response from radium-223 as well. Patients are generally very diligent about monitoring their PSA, so this can be a bit distressing.

Mark Klein. Julie, have you noticed a PSA flare with radium-223? I know it has been reported.

Julie Graff. I haven’t. But I put little stock in PSAs in these patients. I spend 20 minutes explaining to patients that the PSA is not helpful in determining whether or not the radium is working. I tell them that the bone marker alkaline phosphatase may decrease. And I think it’s important to note, too, that radium-223 is not a treatment we have on the shelf. We order it from Denver I believe. It is weight based, and it takes 5 days to get.

Clinical Trials

Mark Klein. That leads us into clinical trials. What is the role for precision oncology in prostate cancer right now, specifically looking at particular panels? One would be the DNA repair enzyme-based genes and/or also the AR variants and any other markers.

Elizabeth Hansen. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network came out with a statement recommending germ-line and somatic-mutation testing in all patients with metastatic prostate cancer. This highlights the need to offer patients the availability of clinical trials.

Julie Graff. I agree. We occasionally get to a place in the disease where patients are feeling fine, but we don’t have anything else to offer. The studies by Robinson16 and then Matteo17 showed that (a) these DNA repair defects are present in about a quarter of patients; and (b) that PARP inhibitors can help these patients. At least it has an anticancer effect.

What’s interesting is that we have TRITON2, and TRITON3, which are sponsored by Clovis,for patients with BRCA 1/2 and ATM mutations and using the PARP-inhibitor rucaparib. Based on the data we have available, we thought a quarter of patients would have the mutation in the tumor, but they’re finding that it is more like 10% to 15%. They are screening many patients but not finding it.

I agree that clinical trials are the way to go. I am hopeful that we’ll get more treatments based on molecular markers. The approval for pembrolizumab in any tumor type with microsatellite instability is interesting, but in prostate cancer, I believe that’s about 3%. I haven’t seen anyone qualify for pembrolizumab based on that. Another plug for clinical trials: Let’s learn more and offer our patients potentially beneficial treatments earlier.

Mark Klein. The first interim analysis from the TRITON2 study found about 12% of patients had alterations in BRCA 1/2. But in those that met the RECIST criteria, they were able to have evaluable disease via that standard with about a 44% response rate so far and a 51% PSA response rate. It is promising data, but it’s only 85 patients so far. We’ll know more because the TRITON2 study is of a more pretreated population than the TRITION3 study at this point. Are there any data on precision medicine and radiation in prostate cancer?

Abhishek Solanki. In the prostate cancer setting, there are not a lot of emerging data specifically looking at using precision oncology biomarkers to help guide decisions in radiation therapy. For example, genomic classifiers, like GenomeDx Decipher (Vancouver, BC) and Myriad Genetics Prolaris (Salt Lake City, UT) are increasingly being utilized in patients with localized disease. Decipher can help predict the risk of recurrence after radical prostatectomy. The difficulty is that there are limited data that show that by using these genomic classifiers, one can improve outcomes in patients over traditional clinical characteristics.

There are 2 trials currently ongoing through NRG Oncology that are using Decipher. The GU002 is a trial for patients who had a radical prostatectomy and had a postoperative PSA that never nadired below 0.2. These patients are randomized between salvage radiation with hormone therapy with or without docetaxel. This trial is collecting Decipher results for patients enrolled in the study. The GU006 is a trial for a slightly more favorable group of patients who do nadir but still have biochemical recurrence and relatively low PSAs. This trial randomizes between radiotherapy alone and radiotherapy and 6 months of apalutamide, stratifying patients based on Decipher results, specially differentiating between patients who have a luminal vs basal subtype of prostate cancer. There are data that suggest that patients who have a luminal subtype may benefit more from the combination of radiation and hormone therapy vs patients who have basal subtype.18 However this hasn’t been validated in a prospective setting, and that’s what this trial will hopefully do.

Immunotherapies

Mark Klein. Outside of prostate cancer, there has been a lot of research trying to determine how to improve PD-L1 expression. Where are immunotherapy trials moving? How radiation might play a role in conjunction with immunotherapy.

Julie Graff. Two phase 3 studies did not show statistically improved survival or statistically significant survival improvement on ipilimumab, an immunotherapy agent that targets CTLA4. Some early studies of the PD-1 drugs nivolumab and pembrolizumab did not show much response with monotherapy. Despite the negative phase 3 studies for ipilimumab, we periodically see exceptional responses.

In prostate cancer, enzalutamide is FDA approved. And there’s currently a phase 3 study of the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab plus enzalutamide in patients who have progressed on abiraterone. That trial is fully accrued, bu

I just received a Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award to open a VA-only study looking at fecal microbiota transplant from responders to nonresponders to see how manipulating host factors can increase potential responses to PD-1 inhibition.

Abhishek Solanki. The classic mechanism by which radiation therapy works is direct DNA damage and indirect DNA damage through hydroxyl radicals that leads to cytotoxicity. But preclinical and clinical data suggest that radiation therapy can augment the local and systemic immunotherapy response. The radiation oncologist’s dream is what is called the abscopal effect, which is the idea that when you treat one site of disease with radiation, it can induce a response at other sites that didn’t get radiation therapy through reactivation of the immune system. I like to think of the abscopal effect like bigfoot—it’s elusive. However, it seems that the setting it is most likely to happen in is in combination with immunotherapy.

One of the ways that radiation fails locally is that it can upregulate PD-1 expression, and as a result, you can have progression of the tumor because of local immune suppression. We know that T cells are important for the activity of radiation therapy. If you combine checkpoint inhibition with radiation therapy, you can not only have better local control in the area of the tumor, but perhaps you can release tumor antigens that will then induce a systemic response.

The other potential mechanism by which radiation may work synergistically with immunotherapy is as a debulking agent. There are some data that suggest that the ratio of T-cell reinvigoration to bulk of disease, or the volume of tumor burden, is important. That is, having T-cell reinvigoration may not be sufficient to have a response to immunotherapy in patients with a large burden of disease. By using radiation to debulk disease, perhaps you could help make checkpoint inhibition more effective. Ultimately, in the setting of prostate cancer, there are not a lot of data yet showing meaningful benefits with the combination of immunotherapy and radiotherapy, but there are trials that are ongoing that will educate on potential synergy.

Pharmacy

Julie Graff. Before we end I want to make sure that we applaud the amazing pharmacists and patient care navigation teams in the VA who do such a great job of getting veterans the appropriate treatment expeditiously and keeping them safe. It’s something that is truly unique to the VA. And I want to thank the people on this call who do this every day.

Elizabeth Hansen. Thank you Julie. Compared with working in the community, at the VA I’m honestly amazed by the ease of access to these medications for our patients. Being able to deliver medications sometimes the same day to the patient is just not something that happens in the community. It’s nice to see that our veterans are getting cared for in that manner.

Author disclosures

Dr. Solanki participated in advisory boards for Blue Earth Diagnostics’ fluciclovine PET and was previously paid as a consultant. Dr. Graff is a consultant for Sanofi (docetaxel) and Astellas (enzalutamide), and has received research funding (no personal funding)from Sanofi, Merck (pembrolizumab), Astellas, and Jannsen (abiraterone, apalutamide). The other authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Sequencing Therapies

Mark Klein, MD. The last few years, there have been several new trials in prostate cancer for people in a metastatic setting or more advanced local setting, such as the STAMPEDE, LATITUDE, and CHAARTED trials.1-4 In addition, recently a few trials have examined apalutamide and enzalutamide for people who have had PSA (prostate-specific antigen) levels rapidly rising within about 10 months or so. One of the questions that arises is, how do we wrap our heads around sequencing these therapies. Is there a sequence that we should be doing and thinking about upfront and how do the different trials compare?

Julie Graff, MD. It just got more complicated. There was news today (December 20, 2018) that using enzalutamide early on in newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer may have positive results. It is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but for patients who present with metastatic prostate cancer, we may have 4 potential treatments. We could have androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) alone, ADT plus docetaxel, enzalutamide, or abiraterone.

When I see patients in this situation, I talk to them about their options, the pros and cons of each option, and try to cover all the trials that look at these combinations. It can be quite a long visit. I talk to the patient about who benefits most, whether it is patients with high-risk factors or high-volume cancers. Also, I talk with the patient about all the adverse effects (AEs), and I look at my patients’ comorbid conditions and come up with a plan.

I encourage any patient who has high-volume or high-risk disease to consider more than just ADT alone. For many patients, I have been using abiraterone plus ADT. I have a wonderful pharmacist. As a medical oncologist, I can’t do it on my own. I need someone to follow patients’ laboratory results and to be available for medication questions and complications.

Elizabeth Hansen, PharmD. With the increasing number of patients on oral antineoplastics, monitoring patients in the outpatient setting has become an increasing priority and one of my major roles as a pharmacist in the clinic at the Chalmers P. Wylie VA Ambulatory Care Center in Columbus, Ohio. This is especially important as some of these treatments require frequent laboratory monitoring, such as abiraterone with liver function tests every 2 weeks for the first 3 months of treatment and monthly thereafter. Without frequent-follow up it’s easy for these patients to get lost in the shuffle.

Abhishek Solanki, MD. You could argue that a fifth option is prostate-directed radiation for patients who have limited metastases based on the STAMPEDE trial, which we’ve started integrating into our practice at the Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.4

Mark Klein. Do you have a feel for the data and using radiation in oligometastatic (≤ 5 metastatic tumors) disease in prostate cancer and how well that might work?

Abhishek Solanki. The best data we have are from the multi-arm, multistage STAMPEDE trial systemic therapies and local therapy in the setting of high-risk localized disease and metastatic disease.6 The most recent publication looked specifically at the population with newly diagnosed metastatic disease and compared standard ADT (and docetaxel in about 18% of the patients) with or without prostate-directed radiation therapy. There was no survival benefit with radiation in the overall population, but in the subgroup of patients with low metastatic burden, there was an 8% survival benefit at 3 years.

It’s difficult to know what to make of that information because, as we’ve discussed already, there are other systemic therapy options that are being used more and more upfront such as abiraterone. Can you see the same benefit of radiation in that setting? The flip side is that in this study, radiation just targeted the prostate; could survival be improved even more by targeting all sites of disease in patients with oligometastatic disease? These are still open questions in prostate cancer and there are clinical trials attempting to define the clinical benefit of radiation in the metastatic setting for patients with limited metastases.

Mark Klein. How do you select patients for radiation in this particular situation; How do you approach stratification when radiation is started upfront?

Abhishek Solanki. In the STAMPEDE trial, low metastatic burden was defined based on the definition in the CHAARTED trial, which was those patients who did not have ≥ 4 bone metastases with ≥ 1 outside the vertebral bodies or pelvis, and did not have visceral metastases.7 That’s tough, because this definition could be a patient with a solitary bone metastasis but also could include some patients who have involved nodes extending all the way up to the retroperitoneal nodes—that is a fairly heterogeneous population. What we have done at our institution is select patients who have 3 to 5 metastases, administer prostate radiation therapy, and add stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for the other sites of disease, invoking the oligometastasis approach.

We have been doing this more frequently in the last few months. Typically, we’ll do 3 to 5 fractions of SBRT to metastases. For the primary, if the patient chooses SBRT, we’ll take that approach. If the patient chooses a more standard fractionation, we’ll do 20 treatments, but from a logistic perspective, most patients would rather come in for 5 treatments than 20. We also typically would start these patients on systemic hormonal therapy.

Mark Klein. At that point, are they referred back to medical oncology for surveillance?

Abhishek Solanki. Yes, they are followed by medical oncology and radiation oncology, and typically would continue hormonal therapy.

Mark Klein. Julie, how have you thought about presenting the therapeutic options for those patients who would be either eligible for docetaxel with high-bulk disease or abiraterone? Do you find patients prefer one or the other?

Julie Graff. I try to be very open about all the possibilities, and I present both. I don’t just decide for the patient chemotherapy vs abiraterone, but after we talk about it, most of my patients do opt for the abiraterone. I had a patient referred from the community—we are seeing more and more of this because abiraterone is so expensive—whose ejection fraction was about 38%. I said to that patient, “we could do chemotherapy, but we shouldn’t do abiraterone.” But usually it’s not that clear-cut.

Elizabeth Hansen. There was also an update from the STAMPEDE trial published recently comparing upfront abiraterone and prednisone to docetaxel (18 weeks) in advanced or metastatic prostate cancer. Results from this trial indicated a nearly identical overall survival (OS) (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.16; 95% CI, 0.82-1.65; P = .40). However, the failure-free survival (HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.39-0.67; P < .001) and progression-free survival (PFS) (HR= 0.65; 95% CI, 0.0.48-0.88; P = .005) favored abiraterone.8,9 The authors argue that while there was no change in OS, this trial demonstrates an important difference in the pattern of treatment failure.

Julie, do you think there will be any change in the treatment paradigm between docetaxel and abiraterone with this new update?

Julie Graff. I wasn’t that impressed by that study. I do not see it as practice changing, and it makes sense to me that the PFS is different in the 2 arms because we give chemotherapy and take a break vs giving abiraterone indefinitely. For me, there’s not really a shift.

Patients With Rising PSAs

Mark Klein. Let’s discuss the data from the recent studies on enzalutamide and apalutamide for the patients with fast-rising PSAs. In your discussions with other prostate researchers, will this become a standard part of practice or not?

Julie Graff. I was one of the authors on the SPARTAN apalutamide study.10 For a long time, we have had patients without metastatic disease but with a PSA relapse after surgery or radiation; and the PSA levels climb when the cancer becomes resistant to ADT. We haven’t had many options in that setting except to use bicalutamide and some older androgen receptor (AR) antagonists. We used to use estrogen and ketoconazole as well.

But now 2 studies have come out looking at a primary endpoint of metastases-free survival. Patients whose PSA was doubling every 10 months or shorter were randomized to either apalutamide (SPARTAN10) or enzalutamide (PROSPER11), both second-generation AR antagonists. There was a placebo control arm in each of the studies. Both studies found that adding the second-generation AR targeting agent delayed the time to metastatic disease by about 2 years. There is not any signal yet for statistically significant OS benefit, so it is not entirely clear if you could wait for the first metastasis to develop and then give 1 of these treatments and have the same OS benefit.

At the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPORHCS), it took a while to make these drugs available. My fellows were excited to give these drugs right away, but I often counsel patients that we don’t know if the second-generation AR targeting agents will improve survival. They almost certainly will bring down PSAs, which helps with peace of mind, but anything we add to the ADT can cause more AEs.

I have been cautious with second-generation AR antagonists because patients, when they take one of these drugs, are going to be on it for a long time. The FDA has approved those 2 drugs regardless of PSA doubling time, but I would not give it for a PSA doubling time > 10 months. In my practice about a quarter of patients who would qualify for apalutamide or enzalutamide are actually taking one, and the others are monitored closely with computed tomography (CT) and bone scans. When the disease becomes metastatic, then we start those drugs.

Mark Klein. Why 10 months, why not 6 months, a year, or 18 months? Is there reasoning behind that?