User login

Here is our problem: Family medicine has allowed itself, and its patients, to be picked apart by the forces of reductionism and a system that profits from the sick and suffering. We have lost sight of our purpose and our vision to care for the whole person. We have lost our way as healers.

The result is not only a decline in the specialty of family medicine as a leader in primary care but declining value and worsening outcomes in health care overall. We need to get our mojo back. We can do this by focusing less on trying to be all things to all people at all times, and more on creating better models for preventing, managing, and reversing chronic disease. This means providing health care that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

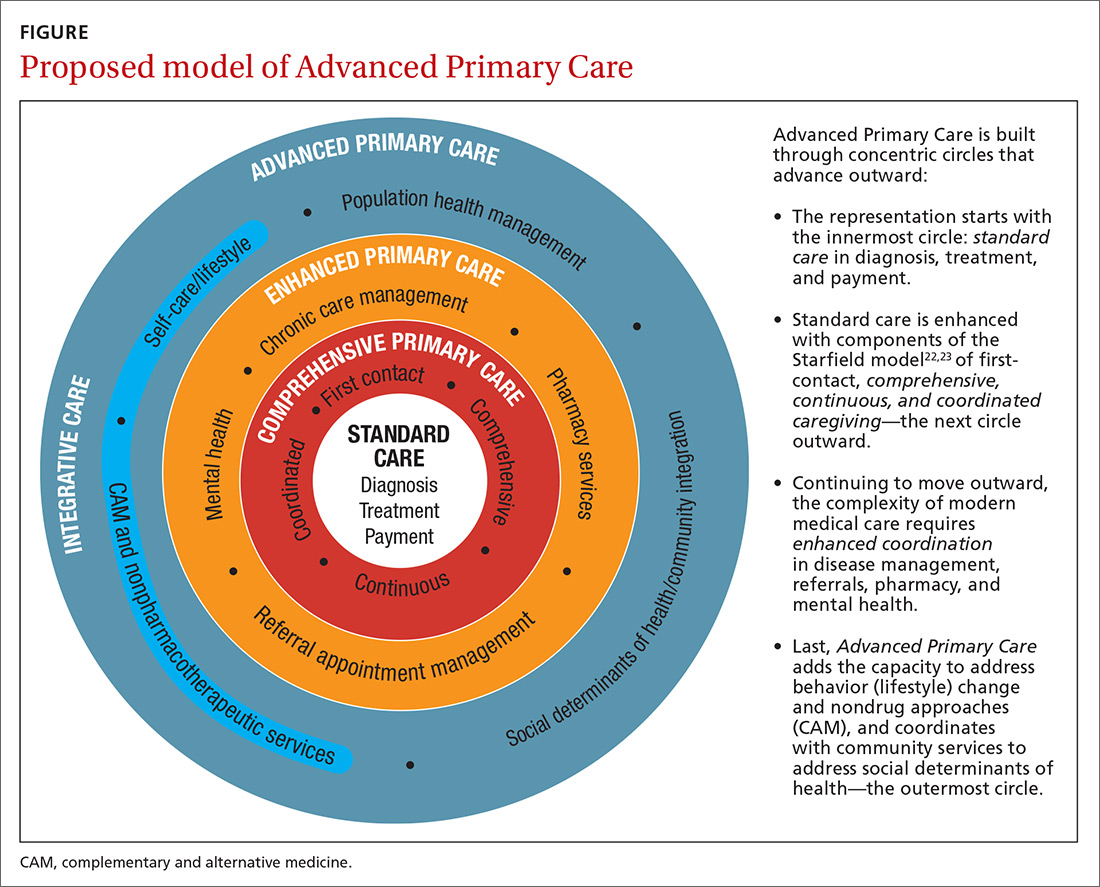

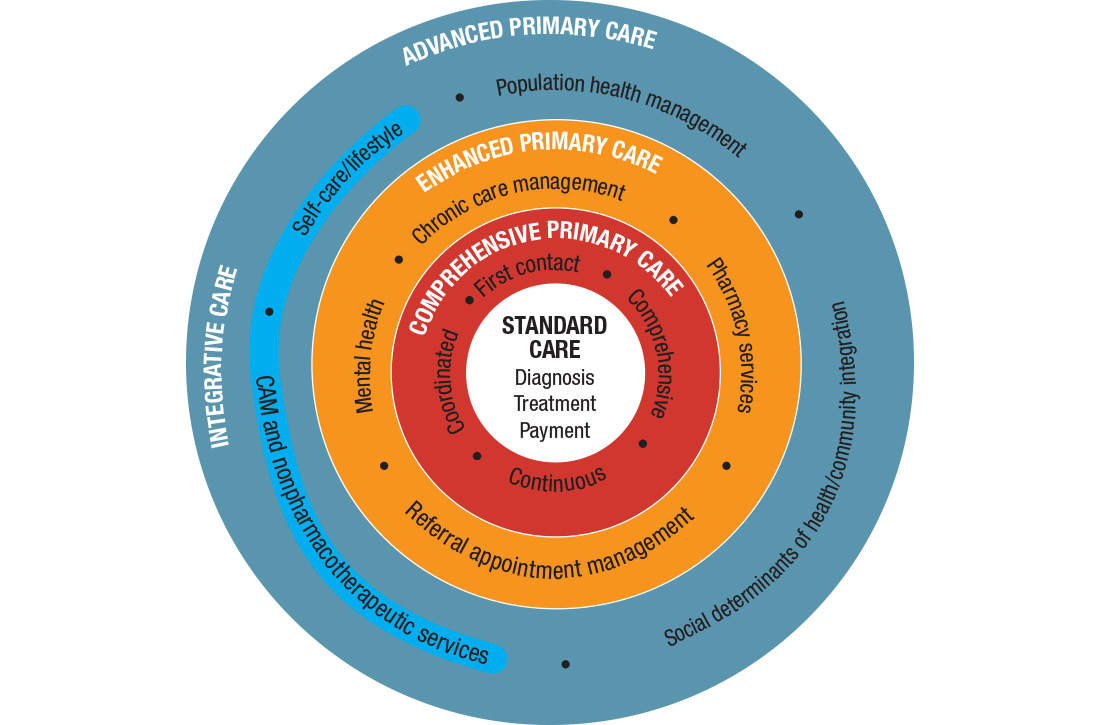

I call this model Advanced Primary Care, or APC (FIGURE). In this article, I describe exemplars of APC from across the United States. I also provide tools to help you recover its central feature, holism—care of the whole person in mind, body, community, and spirit—in your practice, thus returning us to the core purpose of family medicine.

Holism is central to family medicine

More than 40 years ago, psychiatrist George Engel, MD, published a seminal article in Science that inspired a radical vision of how health care should be practiced.1 Called the biopsychosocial model, it stated what, in some ways, is obvious: Human beings are complex organisms embedded in complex environments made up of distinct, yet interacting, dimensions. These dimensions included physical, psychological, and social components. Engel’s radical proposition was that these dimensions are definable and measurable and that good medicine cannot afford to ignore any of them.

Engel’s assertion that good medicine requires holism was a clarion call during a time of rapidly expanding knowledge and subspecialization. That call was the inspiration for a new medical specialty called family medicine, which dared to proclaim that the best way to heal was to care for the whole person within the context of that person’s emotional and social environment. Family medicine reinvigorated primary care and grew rapidly, becoming a preeminent primary care specialty in the United States.

Continue to : Reductionism is relentless

Reductionism is relentless

But the forces of medicine were—and still are—driving relentlessly the other way. The science of the small and particular (reductionism), with dazzling technology and exploding subspecialty knowledge, and backed by powerful economic drivers, rewards health care for pulling the patient and the medical profession apart. We pay more to those who treat small parts of a person over a short period than to those who attend to the whole person over the lifetime.

Today, family medicine—for all of its common sense, scientific soundness, connectedness to patients, and demonstrated value—struggles to survive.2-6 The holistic vision of Engel is declining. The struggle in primary care is that its holistic vision gets co-opted by specialized medical science—and then it desperately attempts to apply those small and specialized tools to the care of patients in their wholeness. Holism is largely dead in health care, and everyone pays the consequences.7

Health care is losing its value

The damage from this decline in holism is not just to primary care but to the value of health care in general. Most medical care being delivered today—comprising diagnosis, treatment, and payment (the innermost circle of the FIGURE)—is not producing good health.8 Only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care.9 The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life, including those related to food, movement, sleep, stress, and substance use.10 Increasingly, it is the economic and social determinants of health that influence this behavior and have a greater impact on health and lifespan than physiology or genes.11 The same social determinants of health also influence patients’ ability to obtain medical care and pursue a meaningful life.12

The result of this decline in holism and in the value of health care in general has been a relentless rise in the cost of medical care13-15 and the need for social services; declining life expectancy16,17 and quality of life18; growing patient dissatisfaction; and burnout in providers.19,20 Health care has become, as investor and business leader Warren Buffet remarked, the “tapeworm” of the economy and a major contributor to growing disparities in health and well-being between the haves and have-nots.21 Engel’s prediction that good medicine cannot afford to ignore holism has come to pass.

3-step solution:Return to whole-person care

Family medicine needs to return to whole-person care, but it can do so only if it attends to, and effectively delivers on, the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease and the enhancement of health and well-being. This can happen only if family medicine stops trying to be all things to all people at all times and, instead, focuses on what matters to the patient as a person.

Continue to: This means that the core...

This means that the core interaction in family medicine must be to assess the whole person—mind, body, social, spirit—and help that person make changes that improve his/her/their health and well-being based on his/her/their individualized needs and social context. In other words, family medicine needs to deliver a holistic model of APC that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

How does one get from “standard” primary care of today (the innermost circle of the FIGURE) to a framework that truly delivers on the promise of healing? I propose 3 steps to return holism to family medicine.

STEP 1: Start with comprehensive, coordinated primary care. We know that this works. Starfield and others demonstrated this 2 decades ago, defining and devising what we know as quality primary care—characterized by first-contact care, comprehensive primary care (CPC), continuous care, and coordinated care.22 This type of primary care improves outcomes, lowers costs, and is satisfying to patients and providers.23 The physician cares for the patient throughout that person’s entire life cycle and provides all evidence-based services needed to prevent and treat common conditions. Comprehensive primary care is positioned in the first circle outward from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

As medicine has become increasingly complex and subspecialized, however, the ability to coordinate care is often frayed, adding cost and reducing quality.24-26 Today, comprehensive primary care needs enhanced coordination. At a minimum, this means coordinating services for:

- chronic disease management (outpatient and inpatient transitions and emergency department use)

- referral (specialists and tests)

- pharmacy services (including delivery and patient education support).

An example of a primary care system that meets these requirements is the Catalyst Health Network in central Texas, which supplies coordination services to more than 1000 comprehensive primary care practices and 1.5 million patients.27 The Catalyst Network makes money for those practices, saves money in the system, enhances patient and provider satisfaction, and improves population health in the community.27 I call this enhanced primary care (EPC), shown in the second circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

STEP 2: Add integrative medicine and mental health. EPC improves fragmented care but does not necessarily address a patient’s underlying determinants of healing. We know that health behaviors such as smoking cessation, avoidance of alcohol and drug abuse, improved diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management contribute 40% to 60% of a person’s and a population’s health.10 In addition, evidence shows that behavioral health services, along with lifestyle change support, can even reverse many chronic diseases seen in primary care, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, depression, and substance abuse.28,29

Continue to: Therefore, we need to add...

Therefore, we need to add routine mental health services and nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches (eg, complementary and alternative medicine) to primary care.30 Doing so requires that behavioral change and self-care become a central feature of the doctor–patient dialogue and team skills31 and be added to primary care.30,31 I call this integrative primary care (IPC), shown on the left side in the third circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

An example of IPC is Whole Health, an initiative of the US Veteran’s Health Administration. Whole Health empowers and informs a person-centered approach and integrates it into the delivery of routine care.32 Evaluation of Whole Health implementation, which involved more than 130,000 veterans followed for 2 years, found a net overall reduction in the total cost of care of 20%—saving nearly $650 million or, on average, more than $4500 per veteran.33

STEP 3: Address social determinants of health. Primary care will not fully be part of the solution for producing health and well-being unless it becomes instrumental in addressing the social determinants of health (SDH), defined as “… conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”34 These determinants include not only basic needs, such as housing, food, safety, and transportation (ie, social needs), but also what are known as structural determinants, such as income, education, language, and racial and ethnic bias. Health care cannot solve all of these social ills,but it is increasingly being called on to be the nexus of coordination for services that address these needs when they affect health outcomes.35,36

Examples of health systems that provide for social needs include the free “food prescription” program of Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System, for patients with diabetes who do not have the resources to pay for food.37 This approach improves blood glucose control by patients and saves money on medications and other interventions. Similarly, Kaiser Permanente has experimented with housing vouchers for homeless patients,and most Federally Qualified Health Centers provide bus or other transportation tickets to patients for their appointments and free or discounted tests and specialty care.38

Implementing whole-person care for all

I propose that we make APC the central focus of family medicine. This model would comprise CPC, plus EPC, IPC, and community coordination to address SDH. This is expressed as:

CPC + EPC + IPC + SDH = APC

Continue to: APC would mean...

APC would mean health for the whole person and for all people. Again, the FIGURE shows how this model, encompassing the entire third circle out from the center circle, could be created from current models of care.

How do we pay for this? We already do—and way too much. The problem is not lack of money in the health care system but how it is organized and distributed. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are developing value-based payment models to help cover this type of care,39 but payers cannot pay for something if it is unavailable.

Can family physicians deliver APC? I believe they can, and have given a few examples here to show how this is already happening. To help primary care providers start to deliver APC in their system, my team and I have built the HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note Toolkit to use in daily practice.40 These and other tools are being used by a number of large hospital systems and health care networks around the country. (You can download the HOPE Note Toolkit, at no cost, at https://drwaynejonas.com/resources/hope-note/.)

Whatever we call this new type of primary care, it needs to care for the whole person and to be available to all. It finds expression in these assertions:

- We cannot ignore an essential part of what a human being is and expect them to heal or become whole.

- We cannot ignore essential people in our communities and expect our costs to go down or our compassion to go up.

- We need to stop allowing family medicine to be co-opted by reductionism and its profits.

In sum, we need a new vision of primary care—like Engel’s holistic vision in the 1970s—to motivate us, and we need to return to fundamental concepts of how healing works in medicine.41

CORRESPONDENCE

Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Samueli Integrative Health Programs, 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 617, Alexandria, VA 22314; wayne@drwaynejonas.com.

1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

2. Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, et al. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:744-749.

3. Bronchetti ET, Christensen GS, Hoynes HW. Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2018. www.nber.org/papers/w24762?mc_cid=8c7211d34b&mc_eid=fbbc7df813. Accessed November 24, 2020.

4. Federal Student Aid, US Department of Education. Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). 2018. https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/public-service. Accessed November 24, 2020.

5. Aten B, Figueroa E, Martin T. Notes on estimating the multi-year regional price parities by 16 expenditure categories: 2005-2009. WP2011-03. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; April 2011. www.bea.gov/system/files/papers/WP2011-3.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

6. Aten BH, Figueroa EB, Martin TM. Regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2006-2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; August 2012. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2012/08%20August/0812_regional_price_parities.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

7. Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:293-299.

8. Panel on Understanding Cross-national Health Differences Among High-income Countries, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. The National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, et al. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:129-135.

10. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93.

11. Roeder A. Zip code better predictor of health than genetic code. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Web site. News release. August 4, 2014. www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/zip-code-better-predictor-of-health-than-genetic-code/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

12. US health map. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; March 13, 2018. www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/us-health-map. Accessed November 24, 2020.

13. Highfill T. Comparing estimates of U.S. health care expenditures by medical condition, 2000-2012. Survey of Current Business. 2016;1-5. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/3%20March/0316_comparing_u.s._health_care_expenditures_by_medical_condition.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

14. Waters H, Graf M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US. Washington, DC: Milken Institute; August 2018. https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/ChronicDiseases-HighRes-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

15. Meyer H. Health care spending will hit 19.4% of GDP in the next decade, CMS projects. Modern Health care. February 20, 2019. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20190220/NEWS/190229989/healthcare-spending-will-hit-19-4-of-gdp-in-the-next-decade-cms-projects. Accessed November 24, 2020.

16. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

17. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, et al. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506-514.

18. Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Stroup DF, et al. Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:493-505.

19. Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer, MB, et al. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. Research letter. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:856-858.

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

21. Buffett: Health care is a tapeworm on the economic system. CNBC Squawk Box. February 26, 2018. www.cnbc.com/video/2018/02/26/buffett-health-care-is-a-tapeworm-on-the-economic-system.html. Accessed November 24, 2020.

22. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992.

23. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

24. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001.

25. Burton R. Health policy brief: improving care transitions. Health Affairs. September 13, 2012. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20120913.327236/full/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

26. Toulany A, Stukel TA, Kurdyak P, et al. Association of primary care continuity with outcomes following transition to adult care for adolescents with severe mental illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198415.

27. Helping communities thrive. Catalyst Health Network Web site. www.catalysthealthnetwork.com/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

28. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165-2171.

29. Scherger JE. Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness. 2nd ed. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing; 2016.

30. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al; . Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530.

31. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:207-214.

32. What is whole health? Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. October 13, 2020. www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/explore/about-whole-health.asp. Accessed November 25, 2020.

33. COVER Commission. Creating options for veterans’ expedited recovery. Final report. Washington, DC: US Veterans Administration. January 24, 2020. www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

34. Social determinants of health. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. HealthyPeople.gov Web site. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 24, 2020.

35. Breslin E, Lambertino A. Medicaid and social determinants of health: adjusting payment and measuring health outcomes. Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, State Health and Value Strategies Program Web site. July 2017. www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/SHVS_SocialDeterminants_HMA_July2017.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

36. James CV. Actively addressing social determinants of health will help us achieve health equity. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. April 26, 2019. www.cms.gov/blog/actively-addressing-social-determinants-health-will-help-us-achieve-health-equity. Accessed November 24, 2020.

37. Geisinger receives “Innovation in Advancing Health Equity” award. Geisinger Health Web site. April 24, 2018. www.geisinger.org/health-plan/news-releases/2018/04/23/19/28/geisinger-receives-innovation-in-advancing-health-equity-award. Accessed November 24, 2020.

38. Bresnick J. Kaiser Permanente launches full-network social determinants program. HealthITAnalytics Web site. May 6, 2019. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/kaiser-permanente-launches-full-network-social-determinants-program. Accessed November 25, 2020.

39. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC). Physician and other health Professional services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March 2016: 115-117. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-4-physician-and-other-health-professional-services-march-2016-report-.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

40. Jonas W. Helping patients with chronic diseases and conditions heal with the HOPE Note: integrative primary care case study. https://drwaynejonas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CS_HOPE-Note_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

41. Jonas W. How Healing Works. Berkley, CA: Lorena Jones Books; 2018.

Here is our problem: Family medicine has allowed itself, and its patients, to be picked apart by the forces of reductionism and a system that profits from the sick and suffering. We have lost sight of our purpose and our vision to care for the whole person. We have lost our way as healers.

The result is not only a decline in the specialty of family medicine as a leader in primary care but declining value and worsening outcomes in health care overall. We need to get our mojo back. We can do this by focusing less on trying to be all things to all people at all times, and more on creating better models for preventing, managing, and reversing chronic disease. This means providing health care that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

I call this model Advanced Primary Care, or APC (FIGURE). In this article, I describe exemplars of APC from across the United States. I also provide tools to help you recover its central feature, holism—care of the whole person in mind, body, community, and spirit—in your practice, thus returning us to the core purpose of family medicine.

Holism is central to family medicine

More than 40 years ago, psychiatrist George Engel, MD, published a seminal article in Science that inspired a radical vision of how health care should be practiced.1 Called the biopsychosocial model, it stated what, in some ways, is obvious: Human beings are complex organisms embedded in complex environments made up of distinct, yet interacting, dimensions. These dimensions included physical, psychological, and social components. Engel’s radical proposition was that these dimensions are definable and measurable and that good medicine cannot afford to ignore any of them.

Engel’s assertion that good medicine requires holism was a clarion call during a time of rapidly expanding knowledge and subspecialization. That call was the inspiration for a new medical specialty called family medicine, which dared to proclaim that the best way to heal was to care for the whole person within the context of that person’s emotional and social environment. Family medicine reinvigorated primary care and grew rapidly, becoming a preeminent primary care specialty in the United States.

Continue to : Reductionism is relentless

Reductionism is relentless

But the forces of medicine were—and still are—driving relentlessly the other way. The science of the small and particular (reductionism), with dazzling technology and exploding subspecialty knowledge, and backed by powerful economic drivers, rewards health care for pulling the patient and the medical profession apart. We pay more to those who treat small parts of a person over a short period than to those who attend to the whole person over the lifetime.

Today, family medicine—for all of its common sense, scientific soundness, connectedness to patients, and demonstrated value—struggles to survive.2-6 The holistic vision of Engel is declining. The struggle in primary care is that its holistic vision gets co-opted by specialized medical science—and then it desperately attempts to apply those small and specialized tools to the care of patients in their wholeness. Holism is largely dead in health care, and everyone pays the consequences.7

Health care is losing its value

The damage from this decline in holism is not just to primary care but to the value of health care in general. Most medical care being delivered today—comprising diagnosis, treatment, and payment (the innermost circle of the FIGURE)—is not producing good health.8 Only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care.9 The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life, including those related to food, movement, sleep, stress, and substance use.10 Increasingly, it is the economic and social determinants of health that influence this behavior and have a greater impact on health and lifespan than physiology or genes.11 The same social determinants of health also influence patients’ ability to obtain medical care and pursue a meaningful life.12

The result of this decline in holism and in the value of health care in general has been a relentless rise in the cost of medical care13-15 and the need for social services; declining life expectancy16,17 and quality of life18; growing patient dissatisfaction; and burnout in providers.19,20 Health care has become, as investor and business leader Warren Buffet remarked, the “tapeworm” of the economy and a major contributor to growing disparities in health and well-being between the haves and have-nots.21 Engel’s prediction that good medicine cannot afford to ignore holism has come to pass.

3-step solution:Return to whole-person care

Family medicine needs to return to whole-person care, but it can do so only if it attends to, and effectively delivers on, the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease and the enhancement of health and well-being. This can happen only if family medicine stops trying to be all things to all people at all times and, instead, focuses on what matters to the patient as a person.

Continue to: This means that the core...

This means that the core interaction in family medicine must be to assess the whole person—mind, body, social, spirit—and help that person make changes that improve his/her/their health and well-being based on his/her/their individualized needs and social context. In other words, family medicine needs to deliver a holistic model of APC that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

How does one get from “standard” primary care of today (the innermost circle of the FIGURE) to a framework that truly delivers on the promise of healing? I propose 3 steps to return holism to family medicine.

STEP 1: Start with comprehensive, coordinated primary care. We know that this works. Starfield and others demonstrated this 2 decades ago, defining and devising what we know as quality primary care—characterized by first-contact care, comprehensive primary care (CPC), continuous care, and coordinated care.22 This type of primary care improves outcomes, lowers costs, and is satisfying to patients and providers.23 The physician cares for the patient throughout that person’s entire life cycle and provides all evidence-based services needed to prevent and treat common conditions. Comprehensive primary care is positioned in the first circle outward from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

As medicine has become increasingly complex and subspecialized, however, the ability to coordinate care is often frayed, adding cost and reducing quality.24-26 Today, comprehensive primary care needs enhanced coordination. At a minimum, this means coordinating services for:

- chronic disease management (outpatient and inpatient transitions and emergency department use)

- referral (specialists and tests)

- pharmacy services (including delivery and patient education support).

An example of a primary care system that meets these requirements is the Catalyst Health Network in central Texas, which supplies coordination services to more than 1000 comprehensive primary care practices and 1.5 million patients.27 The Catalyst Network makes money for those practices, saves money in the system, enhances patient and provider satisfaction, and improves population health in the community.27 I call this enhanced primary care (EPC), shown in the second circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

STEP 2: Add integrative medicine and mental health. EPC improves fragmented care but does not necessarily address a patient’s underlying determinants of healing. We know that health behaviors such as smoking cessation, avoidance of alcohol and drug abuse, improved diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management contribute 40% to 60% of a person’s and a population’s health.10 In addition, evidence shows that behavioral health services, along with lifestyle change support, can even reverse many chronic diseases seen in primary care, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, depression, and substance abuse.28,29

Continue to: Therefore, we need to add...

Therefore, we need to add routine mental health services and nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches (eg, complementary and alternative medicine) to primary care.30 Doing so requires that behavioral change and self-care become a central feature of the doctor–patient dialogue and team skills31 and be added to primary care.30,31 I call this integrative primary care (IPC), shown on the left side in the third circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

An example of IPC is Whole Health, an initiative of the US Veteran’s Health Administration. Whole Health empowers and informs a person-centered approach and integrates it into the delivery of routine care.32 Evaluation of Whole Health implementation, which involved more than 130,000 veterans followed for 2 years, found a net overall reduction in the total cost of care of 20%—saving nearly $650 million or, on average, more than $4500 per veteran.33

STEP 3: Address social determinants of health. Primary care will not fully be part of the solution for producing health and well-being unless it becomes instrumental in addressing the social determinants of health (SDH), defined as “… conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”34 These determinants include not only basic needs, such as housing, food, safety, and transportation (ie, social needs), but also what are known as structural determinants, such as income, education, language, and racial and ethnic bias. Health care cannot solve all of these social ills,but it is increasingly being called on to be the nexus of coordination for services that address these needs when they affect health outcomes.35,36

Examples of health systems that provide for social needs include the free “food prescription” program of Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System, for patients with diabetes who do not have the resources to pay for food.37 This approach improves blood glucose control by patients and saves money on medications and other interventions. Similarly, Kaiser Permanente has experimented with housing vouchers for homeless patients,and most Federally Qualified Health Centers provide bus or other transportation tickets to patients for their appointments and free or discounted tests and specialty care.38

Implementing whole-person care for all

I propose that we make APC the central focus of family medicine. This model would comprise CPC, plus EPC, IPC, and community coordination to address SDH. This is expressed as:

CPC + EPC + IPC + SDH = APC

Continue to: APC would mean...

APC would mean health for the whole person and for all people. Again, the FIGURE shows how this model, encompassing the entire third circle out from the center circle, could be created from current models of care.

How do we pay for this? We already do—and way too much. The problem is not lack of money in the health care system but how it is organized and distributed. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are developing value-based payment models to help cover this type of care,39 but payers cannot pay for something if it is unavailable.

Can family physicians deliver APC? I believe they can, and have given a few examples here to show how this is already happening. To help primary care providers start to deliver APC in their system, my team and I have built the HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note Toolkit to use in daily practice.40 These and other tools are being used by a number of large hospital systems and health care networks around the country. (You can download the HOPE Note Toolkit, at no cost, at https://drwaynejonas.com/resources/hope-note/.)

Whatever we call this new type of primary care, it needs to care for the whole person and to be available to all. It finds expression in these assertions:

- We cannot ignore an essential part of what a human being is and expect them to heal or become whole.

- We cannot ignore essential people in our communities and expect our costs to go down or our compassion to go up.

- We need to stop allowing family medicine to be co-opted by reductionism and its profits.

In sum, we need a new vision of primary care—like Engel’s holistic vision in the 1970s—to motivate us, and we need to return to fundamental concepts of how healing works in medicine.41

CORRESPONDENCE

Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Samueli Integrative Health Programs, 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 617, Alexandria, VA 22314; wayne@drwaynejonas.com.

Here is our problem: Family medicine has allowed itself, and its patients, to be picked apart by the forces of reductionism and a system that profits from the sick and suffering. We have lost sight of our purpose and our vision to care for the whole person. We have lost our way as healers.

The result is not only a decline in the specialty of family medicine as a leader in primary care but declining value and worsening outcomes in health care overall. We need to get our mojo back. We can do this by focusing less on trying to be all things to all people at all times, and more on creating better models for preventing, managing, and reversing chronic disease. This means providing health care that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

I call this model Advanced Primary Care, or APC (FIGURE). In this article, I describe exemplars of APC from across the United States. I also provide tools to help you recover its central feature, holism—care of the whole person in mind, body, community, and spirit—in your practice, thus returning us to the core purpose of family medicine.

Holism is central to family medicine

More than 40 years ago, psychiatrist George Engel, MD, published a seminal article in Science that inspired a radical vision of how health care should be practiced.1 Called the biopsychosocial model, it stated what, in some ways, is obvious: Human beings are complex organisms embedded in complex environments made up of distinct, yet interacting, dimensions. These dimensions included physical, psychological, and social components. Engel’s radical proposition was that these dimensions are definable and measurable and that good medicine cannot afford to ignore any of them.

Engel’s assertion that good medicine requires holism was a clarion call during a time of rapidly expanding knowledge and subspecialization. That call was the inspiration for a new medical specialty called family medicine, which dared to proclaim that the best way to heal was to care for the whole person within the context of that person’s emotional and social environment. Family medicine reinvigorated primary care and grew rapidly, becoming a preeminent primary care specialty in the United States.

Continue to : Reductionism is relentless

Reductionism is relentless

But the forces of medicine were—and still are—driving relentlessly the other way. The science of the small and particular (reductionism), with dazzling technology and exploding subspecialty knowledge, and backed by powerful economic drivers, rewards health care for pulling the patient and the medical profession apart. We pay more to those who treat small parts of a person over a short period than to those who attend to the whole person over the lifetime.

Today, family medicine—for all of its common sense, scientific soundness, connectedness to patients, and demonstrated value—struggles to survive.2-6 The holistic vision of Engel is declining. The struggle in primary care is that its holistic vision gets co-opted by specialized medical science—and then it desperately attempts to apply those small and specialized tools to the care of patients in their wholeness. Holism is largely dead in health care, and everyone pays the consequences.7

Health care is losing its value

The damage from this decline in holism is not just to primary care but to the value of health care in general. Most medical care being delivered today—comprising diagnosis, treatment, and payment (the innermost circle of the FIGURE)—is not producing good health.8 Only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care.9 The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life, including those related to food, movement, sleep, stress, and substance use.10 Increasingly, it is the economic and social determinants of health that influence this behavior and have a greater impact on health and lifespan than physiology or genes.11 The same social determinants of health also influence patients’ ability to obtain medical care and pursue a meaningful life.12

The result of this decline in holism and in the value of health care in general has been a relentless rise in the cost of medical care13-15 and the need for social services; declining life expectancy16,17 and quality of life18; growing patient dissatisfaction; and burnout in providers.19,20 Health care has become, as investor and business leader Warren Buffet remarked, the “tapeworm” of the economy and a major contributor to growing disparities in health and well-being between the haves and have-nots.21 Engel’s prediction that good medicine cannot afford to ignore holism has come to pass.

3-step solution:Return to whole-person care

Family medicine needs to return to whole-person care, but it can do so only if it attends to, and effectively delivers on, the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease and the enhancement of health and well-being. This can happen only if family medicine stops trying to be all things to all people at all times and, instead, focuses on what matters to the patient as a person.

Continue to: This means that the core...

This means that the core interaction in family medicine must be to assess the whole person—mind, body, social, spirit—and help that person make changes that improve his/her/their health and well-being based on his/her/their individualized needs and social context. In other words, family medicine needs to deliver a holistic model of APC that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

How does one get from “standard” primary care of today (the innermost circle of the FIGURE) to a framework that truly delivers on the promise of healing? I propose 3 steps to return holism to family medicine.

STEP 1: Start with comprehensive, coordinated primary care. We know that this works. Starfield and others demonstrated this 2 decades ago, defining and devising what we know as quality primary care—characterized by first-contact care, comprehensive primary care (CPC), continuous care, and coordinated care.22 This type of primary care improves outcomes, lowers costs, and is satisfying to patients and providers.23 The physician cares for the patient throughout that person’s entire life cycle and provides all evidence-based services needed to prevent and treat common conditions. Comprehensive primary care is positioned in the first circle outward from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

As medicine has become increasingly complex and subspecialized, however, the ability to coordinate care is often frayed, adding cost and reducing quality.24-26 Today, comprehensive primary care needs enhanced coordination. At a minimum, this means coordinating services for:

- chronic disease management (outpatient and inpatient transitions and emergency department use)

- referral (specialists and tests)

- pharmacy services (including delivery and patient education support).

An example of a primary care system that meets these requirements is the Catalyst Health Network in central Texas, which supplies coordination services to more than 1000 comprehensive primary care practices and 1.5 million patients.27 The Catalyst Network makes money for those practices, saves money in the system, enhances patient and provider satisfaction, and improves population health in the community.27 I call this enhanced primary care (EPC), shown in the second circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

STEP 2: Add integrative medicine and mental health. EPC improves fragmented care but does not necessarily address a patient’s underlying determinants of healing. We know that health behaviors such as smoking cessation, avoidance of alcohol and drug abuse, improved diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management contribute 40% to 60% of a person’s and a population’s health.10 In addition, evidence shows that behavioral health services, along with lifestyle change support, can even reverse many chronic diseases seen in primary care, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, depression, and substance abuse.28,29

Continue to: Therefore, we need to add...

Therefore, we need to add routine mental health services and nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches (eg, complementary and alternative medicine) to primary care.30 Doing so requires that behavioral change and self-care become a central feature of the doctor–patient dialogue and team skills31 and be added to primary care.30,31 I call this integrative primary care (IPC), shown on the left side in the third circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

An example of IPC is Whole Health, an initiative of the US Veteran’s Health Administration. Whole Health empowers and informs a person-centered approach and integrates it into the delivery of routine care.32 Evaluation of Whole Health implementation, which involved more than 130,000 veterans followed for 2 years, found a net overall reduction in the total cost of care of 20%—saving nearly $650 million or, on average, more than $4500 per veteran.33

STEP 3: Address social determinants of health. Primary care will not fully be part of the solution for producing health and well-being unless it becomes instrumental in addressing the social determinants of health (SDH), defined as “… conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”34 These determinants include not only basic needs, such as housing, food, safety, and transportation (ie, social needs), but also what are known as structural determinants, such as income, education, language, and racial and ethnic bias. Health care cannot solve all of these social ills,but it is increasingly being called on to be the nexus of coordination for services that address these needs when they affect health outcomes.35,36

Examples of health systems that provide for social needs include the free “food prescription” program of Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System, for patients with diabetes who do not have the resources to pay for food.37 This approach improves blood glucose control by patients and saves money on medications and other interventions. Similarly, Kaiser Permanente has experimented with housing vouchers for homeless patients,and most Federally Qualified Health Centers provide bus or other transportation tickets to patients for their appointments and free or discounted tests and specialty care.38

Implementing whole-person care for all

I propose that we make APC the central focus of family medicine. This model would comprise CPC, plus EPC, IPC, and community coordination to address SDH. This is expressed as:

CPC + EPC + IPC + SDH = APC

Continue to: APC would mean...

APC would mean health for the whole person and for all people. Again, the FIGURE shows how this model, encompassing the entire third circle out from the center circle, could be created from current models of care.

How do we pay for this? We already do—and way too much. The problem is not lack of money in the health care system but how it is organized and distributed. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are developing value-based payment models to help cover this type of care,39 but payers cannot pay for something if it is unavailable.

Can family physicians deliver APC? I believe they can, and have given a few examples here to show how this is already happening. To help primary care providers start to deliver APC in their system, my team and I have built the HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note Toolkit to use in daily practice.40 These and other tools are being used by a number of large hospital systems and health care networks around the country. (You can download the HOPE Note Toolkit, at no cost, at https://drwaynejonas.com/resources/hope-note/.)

Whatever we call this new type of primary care, it needs to care for the whole person and to be available to all. It finds expression in these assertions:

- We cannot ignore an essential part of what a human being is and expect them to heal or become whole.

- We cannot ignore essential people in our communities and expect our costs to go down or our compassion to go up.

- We need to stop allowing family medicine to be co-opted by reductionism and its profits.

In sum, we need a new vision of primary care—like Engel’s holistic vision in the 1970s—to motivate us, and we need to return to fundamental concepts of how healing works in medicine.41

CORRESPONDENCE

Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Samueli Integrative Health Programs, 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 617, Alexandria, VA 22314; wayne@drwaynejonas.com.

1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

2. Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, et al. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:744-749.

3. Bronchetti ET, Christensen GS, Hoynes HW. Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2018. www.nber.org/papers/w24762?mc_cid=8c7211d34b&mc_eid=fbbc7df813. Accessed November 24, 2020.

4. Federal Student Aid, US Department of Education. Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). 2018. https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/public-service. Accessed November 24, 2020.

5. Aten B, Figueroa E, Martin T. Notes on estimating the multi-year regional price parities by 16 expenditure categories: 2005-2009. WP2011-03. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; April 2011. www.bea.gov/system/files/papers/WP2011-3.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

6. Aten BH, Figueroa EB, Martin TM. Regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2006-2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; August 2012. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2012/08%20August/0812_regional_price_parities.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

7. Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:293-299.

8. Panel on Understanding Cross-national Health Differences Among High-income Countries, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. The National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, et al. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:129-135.

10. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93.

11. Roeder A. Zip code better predictor of health than genetic code. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Web site. News release. August 4, 2014. www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/zip-code-better-predictor-of-health-than-genetic-code/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

12. US health map. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; March 13, 2018. www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/us-health-map. Accessed November 24, 2020.

13. Highfill T. Comparing estimates of U.S. health care expenditures by medical condition, 2000-2012. Survey of Current Business. 2016;1-5. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/3%20March/0316_comparing_u.s._health_care_expenditures_by_medical_condition.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

14. Waters H, Graf M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US. Washington, DC: Milken Institute; August 2018. https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/ChronicDiseases-HighRes-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

15. Meyer H. Health care spending will hit 19.4% of GDP in the next decade, CMS projects. Modern Health care. February 20, 2019. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20190220/NEWS/190229989/healthcare-spending-will-hit-19-4-of-gdp-in-the-next-decade-cms-projects. Accessed November 24, 2020.

16. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

17. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, et al. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506-514.

18. Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Stroup DF, et al. Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:493-505.

19. Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer, MB, et al. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. Research letter. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:856-858.

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

21. Buffett: Health care is a tapeworm on the economic system. CNBC Squawk Box. February 26, 2018. www.cnbc.com/video/2018/02/26/buffett-health-care-is-a-tapeworm-on-the-economic-system.html. Accessed November 24, 2020.

22. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992.

23. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

24. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001.

25. Burton R. Health policy brief: improving care transitions. Health Affairs. September 13, 2012. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20120913.327236/full/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

26. Toulany A, Stukel TA, Kurdyak P, et al. Association of primary care continuity with outcomes following transition to adult care for adolescents with severe mental illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198415.

27. Helping communities thrive. Catalyst Health Network Web site. www.catalysthealthnetwork.com/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

28. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165-2171.

29. Scherger JE. Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness. 2nd ed. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing; 2016.

30. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al; . Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530.

31. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:207-214.

32. What is whole health? Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. October 13, 2020. www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/explore/about-whole-health.asp. Accessed November 25, 2020.

33. COVER Commission. Creating options for veterans’ expedited recovery. Final report. Washington, DC: US Veterans Administration. January 24, 2020. www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

34. Social determinants of health. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. HealthyPeople.gov Web site. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 24, 2020.

35. Breslin E, Lambertino A. Medicaid and social determinants of health: adjusting payment and measuring health outcomes. Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, State Health and Value Strategies Program Web site. July 2017. www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/SHVS_SocialDeterminants_HMA_July2017.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

36. James CV. Actively addressing social determinants of health will help us achieve health equity. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. April 26, 2019. www.cms.gov/blog/actively-addressing-social-determinants-health-will-help-us-achieve-health-equity. Accessed November 24, 2020.

37. Geisinger receives “Innovation in Advancing Health Equity” award. Geisinger Health Web site. April 24, 2018. www.geisinger.org/health-plan/news-releases/2018/04/23/19/28/geisinger-receives-innovation-in-advancing-health-equity-award. Accessed November 24, 2020.

38. Bresnick J. Kaiser Permanente launches full-network social determinants program. HealthITAnalytics Web site. May 6, 2019. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/kaiser-permanente-launches-full-network-social-determinants-program. Accessed November 25, 2020.

39. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC). Physician and other health Professional services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March 2016: 115-117. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-4-physician-and-other-health-professional-services-march-2016-report-.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

40. Jonas W. Helping patients with chronic diseases and conditions heal with the HOPE Note: integrative primary care case study. https://drwaynejonas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CS_HOPE-Note_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

41. Jonas W. How Healing Works. Berkley, CA: Lorena Jones Books; 2018.

1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

2. Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, et al. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:744-749.

3. Bronchetti ET, Christensen GS, Hoynes HW. Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2018. www.nber.org/papers/w24762?mc_cid=8c7211d34b&mc_eid=fbbc7df813. Accessed November 24, 2020.

4. Federal Student Aid, US Department of Education. Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). 2018. https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/public-service. Accessed November 24, 2020.

5. Aten B, Figueroa E, Martin T. Notes on estimating the multi-year regional price parities by 16 expenditure categories: 2005-2009. WP2011-03. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; April 2011. www.bea.gov/system/files/papers/WP2011-3.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

6. Aten BH, Figueroa EB, Martin TM. Regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2006-2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; August 2012. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2012/08%20August/0812_regional_price_parities.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

7. Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:293-299.

8. Panel on Understanding Cross-national Health Differences Among High-income Countries, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. The National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, et al. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:129-135.

10. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93.

11. Roeder A. Zip code better predictor of health than genetic code. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Web site. News release. August 4, 2014. www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/zip-code-better-predictor-of-health-than-genetic-code/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

12. US health map. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; March 13, 2018. www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/us-health-map. Accessed November 24, 2020.

13. Highfill T. Comparing estimates of U.S. health care expenditures by medical condition, 2000-2012. Survey of Current Business. 2016;1-5. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/3%20March/0316_comparing_u.s._health_care_expenditures_by_medical_condition.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

14. Waters H, Graf M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US. Washington, DC: Milken Institute; August 2018. https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/ChronicDiseases-HighRes-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

15. Meyer H. Health care spending will hit 19.4% of GDP in the next decade, CMS projects. Modern Health care. February 20, 2019. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20190220/NEWS/190229989/healthcare-spending-will-hit-19-4-of-gdp-in-the-next-decade-cms-projects. Accessed November 24, 2020.

16. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

17. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, et al. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506-514.

18. Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Stroup DF, et al. Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:493-505.

19. Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer, MB, et al. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. Research letter. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:856-858.

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

21. Buffett: Health care is a tapeworm on the economic system. CNBC Squawk Box. February 26, 2018. www.cnbc.com/video/2018/02/26/buffett-health-care-is-a-tapeworm-on-the-economic-system.html. Accessed November 24, 2020.

22. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992.

23. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

24. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001.

25. Burton R. Health policy brief: improving care transitions. Health Affairs. September 13, 2012. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20120913.327236/full/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

26. Toulany A, Stukel TA, Kurdyak P, et al. Association of primary care continuity with outcomes following transition to adult care for adolescents with severe mental illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198415.

27. Helping communities thrive. Catalyst Health Network Web site. www.catalysthealthnetwork.com/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

28. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165-2171.

29. Scherger JE. Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness. 2nd ed. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing; 2016.

30. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al; . Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530.

31. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:207-214.

32. What is whole health? Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. October 13, 2020. www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/explore/about-whole-health.asp. Accessed November 25, 2020.

33. COVER Commission. Creating options for veterans’ expedited recovery. Final report. Washington, DC: US Veterans Administration. January 24, 2020. www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

34. Social determinants of health. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. HealthyPeople.gov Web site. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 24, 2020.

35. Breslin E, Lambertino A. Medicaid and social determinants of health: adjusting payment and measuring health outcomes. Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, State Health and Value Strategies Program Web site. July 2017. www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/SHVS_SocialDeterminants_HMA_July2017.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

36. James CV. Actively addressing social determinants of health will help us achieve health equity. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. April 26, 2019. www.cms.gov/blog/actively-addressing-social-determinants-health-will-help-us-achieve-health-equity. Accessed November 24, 2020.

37. Geisinger receives “Innovation in Advancing Health Equity” award. Geisinger Health Web site. April 24, 2018. www.geisinger.org/health-plan/news-releases/2018/04/23/19/28/geisinger-receives-innovation-in-advancing-health-equity-award. Accessed November 24, 2020.

38. Bresnick J. Kaiser Permanente launches full-network social determinants program. HealthITAnalytics Web site. May 6, 2019. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/kaiser-permanente-launches-full-network-social-determinants-program. Accessed November 25, 2020.

39. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC). Physician and other health Professional services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March 2016: 115-117. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-4-physician-and-other-health-professional-services-march-2016-report-.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

40. Jonas W. Helping patients with chronic diseases and conditions heal with the HOPE Note: integrative primary care case study. https://drwaynejonas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CS_HOPE-Note_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

41. Jonas W. How Healing Works. Berkley, CA: Lorena Jones Books; 2018.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

❯ Build care teams into your practice so that you integrate “what matters” into the center of the clinical encounter. C

❯ Add practice approaches that help patients engage in healthy lifestyles and that remove social and economic barriers for improving health and well-being. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series