User login

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are uncommon and can occur in the context of genetic conditions. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is an autosomal dominant disorder of the tumor suppressor gene of the same name—MEN1, which encodes for the protein menin. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 is characterized clinically by the presence of 2 or more of the following NETs: parathyroid, pituitary, and pancreaticoduodenal.1 Pancreaticoduodenal NETs occur in 30% to 80% of patients with MEN1 and have malignant potential. Although the majority of pancreaticoduodenal NETs are nonfunctioning, patients may present with symptoms secondary to mass effect.

Genetic testing exists for MEN1, but not all genetic mutations that cause MEN1 have been discovered. Therefore, because negative genetic testing does not rule out MEN1, a diagnosis is based on tumor type and location. Neuroendocrine tumors of the biliary tree are rare, and there

are no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage them.2-4 The following case demonstrates an unusual initial presentation of a NET in the context of MEN1.

Case Report

A 29-year-old, active-duty African-American man deployed in Kuwait presented with icterus, flank pain, and hematuria. His past medical history was significant for nephrolithiasis, and his family history was notable for hyperparathyroidism. Laboratory results showed primary hyperparathyroidism and evidence of biliary obstruction.

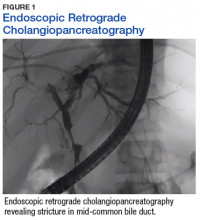

A sestamibi scan demonstrated uptake in a location corresponding with the right inferior parathyroid gland. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed nephrolithiasis and hepatic biliary ductal dilatation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed both intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation, focal narrowing of the proximal common bile duct, and possible adenopathy that was concerning for cholangiocarcinoma. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated a 1 cm to 2 cm focal stricture within the mid-common bile duct with intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation (Figure 1). An endoscopy showed no masses in the duodenum, and anendoscopic ultrasound showed no masses in the pancreas. Endoscopic brushings and endoscopic, ultrasound-guided, fine-needle aspiration

cytology were nondiagnostic. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a dilated hepatic bile duct, an inflamed porta hepatis, and a mass involving the distal hepatic bile duct.

The patient underwent cholecystectomy, radical extra hepatic bile duct resection to the level of the hepatic bifurcation, and hepaticojejunostomy. Gross examination of the specimen showed a nodule centered in the distal common hepatic duct with an adjacent, 2-cm lymph node. The histologic examination revealed a neoplastic proliferation consisting of epithelioid cells with round nuclei and granular chromatin with amphophilic cytoplasm in a trabecular and nested architecture.

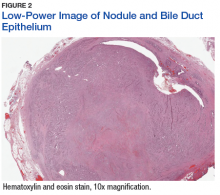

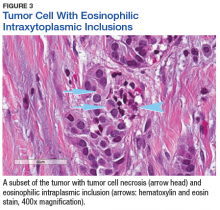

The tumor was centered in the submucosa, which is typical of gastrointestinal NETs (Figure 2). There was no evidence of direct tumor extension elsewhere. About 40% of the tumor cells contained eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusions (Figure 3). The tumor did not involve the margins or lymph node.

Positive staining with the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin and chromagranin A confirmed a well-differentiated NET. The intracytoplasmic inclusions stained strongly positive for cytokeratin CAM 5.2. The tumor had higher-grade features, including tumor cell necrosis, a Ki-67 labeling index of 3%, and perineural invasion. The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for NET of the digestive system classified this tumor as a grade 2, well-differentiated NET and as stage 1a (limited to the bile duct).4

Postoperatively, octreotide scan with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)-CT did not show additional masses or lesions. Serum pancreatic polypeptide was elevated, with the remaining serum and plasma NET markers—including gastrin, glucagon, insulin, chromogranin A, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)—being within reference ranges. Genetic testing (GeneDx, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) showed an E563X nonsense mutation in the MEN1 gene, confirming a MEN1 disorder. The patient then underwent a 4-gland parathyroidectomy with reimplantation; the parathyroid glands demonstrated hyperplasia in all 4 glands.

Biochemical follow-up at 14 months showed that the serum pancreatic polypeptide had normalized. There was no evidence of pituitary orpancreatic hypersecretion. The patient developed hypoparathyroidism, requiring calcium and calcitriol supplementation. Radiographic follow-up using abdominal magnetic resonance imaging at 16 months showed no evidence of disease.

Discussion

This case illustrates a genetic disease with an unusual initial presentation. Primary extrahepatic bile duct NETs are rare and have been reported previously in patients without MEN1.5-9 Neuroendocrine tumors in the hepatic bile duct in patients with MEN1 also have been reported but only after these tumors first appeared in the pancreas or duodenum.10 An extensive literature search revealed no prior reports extrahepatic bile duct NETs with MEN1 as the primary site or with biliary obstruction, which is why this patient’s presentation is particularly interesting.5,6,10-13 The table summarizes select reports of NETs.

Tumor location in this patient was atypical, and genetic testing guided the management. Serum MEN1 genetic testing is indicated in patients with ≥ 2 tumors that are atypical but possibly associated with MEN1 (such as adrenal tumors, gastrinomas, and carcinoids) and in patients aged < 45 years with primary hyperparathyroidism.14,15 The patient in this study was aged 29 years and had hyperparathyroidism and an NET of the hepatic bile duct. This condition was sufficient to warrant genetic testing, the results of which affected the patient’s subsequent parathyroid surgery.15 Despite the suggestion of unifocal localization on the sestamibi scan, the patient underwent the more appropriate subtotal parathyroidectomy.14 The patient’s tumor most likely originated from a germline mutation of the MEN1 gene.

As a result of the patient’s genetic test results, his daughter also was tested. She was found to have the same mutation as her father and will undergo proper tumor surveillance for MEN1. There was no personal or family history of hemangioblastomas, renal cell carcinomas, or cystadenomas, which would have prompted testing for von Hippel-Lindau disease. Likewise, there was no personal or family history of café-au-lait macules and neurofibromas, which would have prompted testing for neurofibromatosis type 1.

Due to the paucity of cases, there are currently no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage extrahepatic biliary NETs.3-5,16 The WHO recommends staging according to adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder and bile duct.3 As such, the pathologic stage of this tumor would be stage 1a.

The significance of the intracytoplasmic inclusion in this case is unknown. Pancreatic NETs and neuroendocrine carcinomas have demonstrated intracytoplasmic inclusions that stain positively for keratin and may indicate more aggressive tumor behavior.17-19 In 1 report, electron microscopic examination demonstrated intermediate filaments with entrapped neurosecretory granules.18 In a series of 84 cases of pancreatic endocrine tumors, 14 had intracytoplasmic inclusions; of these, 5 had MEN1.17 In the present case, the patient continues to show no evidence of tumor recurrence at 16 months after resection.

Conclusion

Extrahepatic biliary neuroendocrine tumors are rare. Further investigation into biliary tree NET staging and future studies to determine the significance of intracytoplasmic inclusions may be beneficial. This case highlights the appropriate use of genetic testing and supports expanding the clinical diagnosis of MEN1 to include NETs of the extrahepatic bile duct.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011.

2. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Neuroendocrine Tumors. In: Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010:227-236.

3. Komminoth P, Arnold R, Capella C, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:274-276.

4. Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:13.

5. Price TN, Thompson GB, Lewis JT, Lloyd RV, Young WF. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to primary gastrinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tree: three case reports and review of literature. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(7):737-749.

6. Bhandarwar AH, Shaikh TA, Borisa AD, et al. Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the left hepatic duct: a case report with review of the literature. Case Rep Surg. 2012:786432.

7. Bhalla P, Powle V, Shah RC, Jagannath P. Neuroendocrine tumor of common hepatic duct. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2012;31(3):144-146.

8. Khan FA, Stevens-Chase A, Chaudhry R, Hashmi A, Edelman D, Weaver D. Extrahepatic biliary obstrution secondary to neuroendocrine tumor of the common hepatic duct. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:46-49.

9. Hong N, Kim HJ, Byun JH, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the extrahepatic bile duct: radiologic and clinical characteristics. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(1):181-191.

10. Tonelli F, Giudici F, Nesi G, Batignani G, Brandi ML. Biliary tree gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(45):8312-8320.

11. Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(1):43-83.

12. Pieterman CRC, Conemans EB, Dreijerink KMA, et al. Thoracic and duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: natural history and function of menin in tumorigenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(3):R121-R142.

13. Pipeleers-Marichal M, Somers G, Willems G, et al. Gastrinomas in the duodenums of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(11):723-727.

14. Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al; Endocrine Society. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2990-3011.

15. Eastell R, Brandi ML, Costa AG, et al. Diagnosis of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3570-3579.

16. Michalopoulos N, Papavramidis TS, Karayannopoulou G, Pliakos I, Papavramidis ST, Kanellos I. Neuroendocrine tumors of extrahepatic biliary tract. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;20(4):765-775.

17. Serra S, Asa SL, Chetty R. Intracytoplasmic inclusions (including the so-called “rhabdoid” phenotype) in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2006;17(1):75-81.

18. Shia J, Erlandson RA, Klimstra DS. Whorls of intermediate filaments with entrapped neurosecretory granules correspond to the “rhabdoid” inclusions seen in pancreatic endocrine

neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(2):271-273.

19. Perez-Montiel MD, Frankel WL, Suster S. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas with ‘Rhabdoid’ features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(5):642-649.

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are uncommon and can occur in the context of genetic conditions. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is an autosomal dominant disorder of the tumor suppressor gene of the same name—MEN1, which encodes for the protein menin. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 is characterized clinically by the presence of 2 or more of the following NETs: parathyroid, pituitary, and pancreaticoduodenal.1 Pancreaticoduodenal NETs occur in 30% to 80% of patients with MEN1 and have malignant potential. Although the majority of pancreaticoduodenal NETs are nonfunctioning, patients may present with symptoms secondary to mass effect.

Genetic testing exists for MEN1, but not all genetic mutations that cause MEN1 have been discovered. Therefore, because negative genetic testing does not rule out MEN1, a diagnosis is based on tumor type and location. Neuroendocrine tumors of the biliary tree are rare, and there

are no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage them.2-4 The following case demonstrates an unusual initial presentation of a NET in the context of MEN1.

Case Report

A 29-year-old, active-duty African-American man deployed in Kuwait presented with icterus, flank pain, and hematuria. His past medical history was significant for nephrolithiasis, and his family history was notable for hyperparathyroidism. Laboratory results showed primary hyperparathyroidism and evidence of biliary obstruction.

A sestamibi scan demonstrated uptake in a location corresponding with the right inferior parathyroid gland. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed nephrolithiasis and hepatic biliary ductal dilatation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed both intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation, focal narrowing of the proximal common bile duct, and possible adenopathy that was concerning for cholangiocarcinoma. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated a 1 cm to 2 cm focal stricture within the mid-common bile duct with intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation (Figure 1). An endoscopy showed no masses in the duodenum, and anendoscopic ultrasound showed no masses in the pancreas. Endoscopic brushings and endoscopic, ultrasound-guided, fine-needle aspiration

cytology were nondiagnostic. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a dilated hepatic bile duct, an inflamed porta hepatis, and a mass involving the distal hepatic bile duct.

The patient underwent cholecystectomy, radical extra hepatic bile duct resection to the level of the hepatic bifurcation, and hepaticojejunostomy. Gross examination of the specimen showed a nodule centered in the distal common hepatic duct with an adjacent, 2-cm lymph node. The histologic examination revealed a neoplastic proliferation consisting of epithelioid cells with round nuclei and granular chromatin with amphophilic cytoplasm in a trabecular and nested architecture.

The tumor was centered in the submucosa, which is typical of gastrointestinal NETs (Figure 2). There was no evidence of direct tumor extension elsewhere. About 40% of the tumor cells contained eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusions (Figure 3). The tumor did not involve the margins or lymph node.

Positive staining with the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin and chromagranin A confirmed a well-differentiated NET. The intracytoplasmic inclusions stained strongly positive for cytokeratin CAM 5.2. The tumor had higher-grade features, including tumor cell necrosis, a Ki-67 labeling index of 3%, and perineural invasion. The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for NET of the digestive system classified this tumor as a grade 2, well-differentiated NET and as stage 1a (limited to the bile duct).4

Postoperatively, octreotide scan with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)-CT did not show additional masses or lesions. Serum pancreatic polypeptide was elevated, with the remaining serum and plasma NET markers—including gastrin, glucagon, insulin, chromogranin A, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)—being within reference ranges. Genetic testing (GeneDx, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) showed an E563X nonsense mutation in the MEN1 gene, confirming a MEN1 disorder. The patient then underwent a 4-gland parathyroidectomy with reimplantation; the parathyroid glands demonstrated hyperplasia in all 4 glands.

Biochemical follow-up at 14 months showed that the serum pancreatic polypeptide had normalized. There was no evidence of pituitary orpancreatic hypersecretion. The patient developed hypoparathyroidism, requiring calcium and calcitriol supplementation. Radiographic follow-up using abdominal magnetic resonance imaging at 16 months showed no evidence of disease.

Discussion

This case illustrates a genetic disease with an unusual initial presentation. Primary extrahepatic bile duct NETs are rare and have been reported previously in patients without MEN1.5-9 Neuroendocrine tumors in the hepatic bile duct in patients with MEN1 also have been reported but only after these tumors first appeared in the pancreas or duodenum.10 An extensive literature search revealed no prior reports extrahepatic bile duct NETs with MEN1 as the primary site or with biliary obstruction, which is why this patient’s presentation is particularly interesting.5,6,10-13 The table summarizes select reports of NETs.

Tumor location in this patient was atypical, and genetic testing guided the management. Serum MEN1 genetic testing is indicated in patients with ≥ 2 tumors that are atypical but possibly associated with MEN1 (such as adrenal tumors, gastrinomas, and carcinoids) and in patients aged < 45 years with primary hyperparathyroidism.14,15 The patient in this study was aged 29 years and had hyperparathyroidism and an NET of the hepatic bile duct. This condition was sufficient to warrant genetic testing, the results of which affected the patient’s subsequent parathyroid surgery.15 Despite the suggestion of unifocal localization on the sestamibi scan, the patient underwent the more appropriate subtotal parathyroidectomy.14 The patient’s tumor most likely originated from a germline mutation of the MEN1 gene.

As a result of the patient’s genetic test results, his daughter also was tested. She was found to have the same mutation as her father and will undergo proper tumor surveillance for MEN1. There was no personal or family history of hemangioblastomas, renal cell carcinomas, or cystadenomas, which would have prompted testing for von Hippel-Lindau disease. Likewise, there was no personal or family history of café-au-lait macules and neurofibromas, which would have prompted testing for neurofibromatosis type 1.

Due to the paucity of cases, there are currently no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage extrahepatic biliary NETs.3-5,16 The WHO recommends staging according to adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder and bile duct.3 As such, the pathologic stage of this tumor would be stage 1a.

The significance of the intracytoplasmic inclusion in this case is unknown. Pancreatic NETs and neuroendocrine carcinomas have demonstrated intracytoplasmic inclusions that stain positively for keratin and may indicate more aggressive tumor behavior.17-19 In 1 report, electron microscopic examination demonstrated intermediate filaments with entrapped neurosecretory granules.18 In a series of 84 cases of pancreatic endocrine tumors, 14 had intracytoplasmic inclusions; of these, 5 had MEN1.17 In the present case, the patient continues to show no evidence of tumor recurrence at 16 months after resection.

Conclusion

Extrahepatic biliary neuroendocrine tumors are rare. Further investigation into biliary tree NET staging and future studies to determine the significance of intracytoplasmic inclusions may be beneficial. This case highlights the appropriate use of genetic testing and supports expanding the clinical diagnosis of MEN1 to include NETs of the extrahepatic bile duct.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are uncommon and can occur in the context of genetic conditions. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is an autosomal dominant disorder of the tumor suppressor gene of the same name—MEN1, which encodes for the protein menin. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 is characterized clinically by the presence of 2 or more of the following NETs: parathyroid, pituitary, and pancreaticoduodenal.1 Pancreaticoduodenal NETs occur in 30% to 80% of patients with MEN1 and have malignant potential. Although the majority of pancreaticoduodenal NETs are nonfunctioning, patients may present with symptoms secondary to mass effect.

Genetic testing exists for MEN1, but not all genetic mutations that cause MEN1 have been discovered. Therefore, because negative genetic testing does not rule out MEN1, a diagnosis is based on tumor type and location. Neuroendocrine tumors of the biliary tree are rare, and there

are no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage them.2-4 The following case demonstrates an unusual initial presentation of a NET in the context of MEN1.

Case Report

A 29-year-old, active-duty African-American man deployed in Kuwait presented with icterus, flank pain, and hematuria. His past medical history was significant for nephrolithiasis, and his family history was notable for hyperparathyroidism. Laboratory results showed primary hyperparathyroidism and evidence of biliary obstruction.

A sestamibi scan demonstrated uptake in a location corresponding with the right inferior parathyroid gland. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed nephrolithiasis and hepatic biliary ductal dilatation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed both intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation, focal narrowing of the proximal common bile duct, and possible adenopathy that was concerning for cholangiocarcinoma. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated a 1 cm to 2 cm focal stricture within the mid-common bile duct with intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation (Figure 1). An endoscopy showed no masses in the duodenum, and anendoscopic ultrasound showed no masses in the pancreas. Endoscopic brushings and endoscopic, ultrasound-guided, fine-needle aspiration

cytology were nondiagnostic. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a dilated hepatic bile duct, an inflamed porta hepatis, and a mass involving the distal hepatic bile duct.

The patient underwent cholecystectomy, radical extra hepatic bile duct resection to the level of the hepatic bifurcation, and hepaticojejunostomy. Gross examination of the specimen showed a nodule centered in the distal common hepatic duct with an adjacent, 2-cm lymph node. The histologic examination revealed a neoplastic proliferation consisting of epithelioid cells with round nuclei and granular chromatin with amphophilic cytoplasm in a trabecular and nested architecture.

The tumor was centered in the submucosa, which is typical of gastrointestinal NETs (Figure 2). There was no evidence of direct tumor extension elsewhere. About 40% of the tumor cells contained eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusions (Figure 3). The tumor did not involve the margins or lymph node.

Positive staining with the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin and chromagranin A confirmed a well-differentiated NET. The intracytoplasmic inclusions stained strongly positive for cytokeratin CAM 5.2. The tumor had higher-grade features, including tumor cell necrosis, a Ki-67 labeling index of 3%, and perineural invasion. The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for NET of the digestive system classified this tumor as a grade 2, well-differentiated NET and as stage 1a (limited to the bile duct).4

Postoperatively, octreotide scan with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)-CT did not show additional masses or lesions. Serum pancreatic polypeptide was elevated, with the remaining serum and plasma NET markers—including gastrin, glucagon, insulin, chromogranin A, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)—being within reference ranges. Genetic testing (GeneDx, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) showed an E563X nonsense mutation in the MEN1 gene, confirming a MEN1 disorder. The patient then underwent a 4-gland parathyroidectomy with reimplantation; the parathyroid glands demonstrated hyperplasia in all 4 glands.

Biochemical follow-up at 14 months showed that the serum pancreatic polypeptide had normalized. There was no evidence of pituitary orpancreatic hypersecretion. The patient developed hypoparathyroidism, requiring calcium and calcitriol supplementation. Radiographic follow-up using abdominal magnetic resonance imaging at 16 months showed no evidence of disease.

Discussion

This case illustrates a genetic disease with an unusual initial presentation. Primary extrahepatic bile duct NETs are rare and have been reported previously in patients without MEN1.5-9 Neuroendocrine tumors in the hepatic bile duct in patients with MEN1 also have been reported but only after these tumors first appeared in the pancreas or duodenum.10 An extensive literature search revealed no prior reports extrahepatic bile duct NETs with MEN1 as the primary site or with biliary obstruction, which is why this patient’s presentation is particularly interesting.5,6,10-13 The table summarizes select reports of NETs.

Tumor location in this patient was atypical, and genetic testing guided the management. Serum MEN1 genetic testing is indicated in patients with ≥ 2 tumors that are atypical but possibly associated with MEN1 (such as adrenal tumors, gastrinomas, and carcinoids) and in patients aged < 45 years with primary hyperparathyroidism.14,15 The patient in this study was aged 29 years and had hyperparathyroidism and an NET of the hepatic bile duct. This condition was sufficient to warrant genetic testing, the results of which affected the patient’s subsequent parathyroid surgery.15 Despite the suggestion of unifocal localization on the sestamibi scan, the patient underwent the more appropriate subtotal parathyroidectomy.14 The patient’s tumor most likely originated from a germline mutation of the MEN1 gene.

As a result of the patient’s genetic test results, his daughter also was tested. She was found to have the same mutation as her father and will undergo proper tumor surveillance for MEN1. There was no personal or family history of hemangioblastomas, renal cell carcinomas, or cystadenomas, which would have prompted testing for von Hippel-Lindau disease. Likewise, there was no personal or family history of café-au-lait macules and neurofibromas, which would have prompted testing for neurofibromatosis type 1.

Due to the paucity of cases, there are currently no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage extrahepatic biliary NETs.3-5,16 The WHO recommends staging according to adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder and bile duct.3 As such, the pathologic stage of this tumor would be stage 1a.

The significance of the intracytoplasmic inclusion in this case is unknown. Pancreatic NETs and neuroendocrine carcinomas have demonstrated intracytoplasmic inclusions that stain positively for keratin and may indicate more aggressive tumor behavior.17-19 In 1 report, electron microscopic examination demonstrated intermediate filaments with entrapped neurosecretory granules.18 In a series of 84 cases of pancreatic endocrine tumors, 14 had intracytoplasmic inclusions; of these, 5 had MEN1.17 In the present case, the patient continues to show no evidence of tumor recurrence at 16 months after resection.

Conclusion

Extrahepatic biliary neuroendocrine tumors are rare. Further investigation into biliary tree NET staging and future studies to determine the significance of intracytoplasmic inclusions may be beneficial. This case highlights the appropriate use of genetic testing and supports expanding the clinical diagnosis of MEN1 to include NETs of the extrahepatic bile duct.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011.

2. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Neuroendocrine Tumors. In: Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010:227-236.

3. Komminoth P, Arnold R, Capella C, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:274-276.

4. Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:13.

5. Price TN, Thompson GB, Lewis JT, Lloyd RV, Young WF. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to primary gastrinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tree: three case reports and review of literature. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(7):737-749.

6. Bhandarwar AH, Shaikh TA, Borisa AD, et al. Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the left hepatic duct: a case report with review of the literature. Case Rep Surg. 2012:786432.

7. Bhalla P, Powle V, Shah RC, Jagannath P. Neuroendocrine tumor of common hepatic duct. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2012;31(3):144-146.

8. Khan FA, Stevens-Chase A, Chaudhry R, Hashmi A, Edelman D, Weaver D. Extrahepatic biliary obstrution secondary to neuroendocrine tumor of the common hepatic duct. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:46-49.

9. Hong N, Kim HJ, Byun JH, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the extrahepatic bile duct: radiologic and clinical characteristics. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(1):181-191.

10. Tonelli F, Giudici F, Nesi G, Batignani G, Brandi ML. Biliary tree gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(45):8312-8320.

11. Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(1):43-83.

12. Pieterman CRC, Conemans EB, Dreijerink KMA, et al. Thoracic and duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: natural history and function of menin in tumorigenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(3):R121-R142.

13. Pipeleers-Marichal M, Somers G, Willems G, et al. Gastrinomas in the duodenums of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(11):723-727.

14. Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al; Endocrine Society. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2990-3011.

15. Eastell R, Brandi ML, Costa AG, et al. Diagnosis of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3570-3579.

16. Michalopoulos N, Papavramidis TS, Karayannopoulou G, Pliakos I, Papavramidis ST, Kanellos I. Neuroendocrine tumors of extrahepatic biliary tract. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;20(4):765-775.

17. Serra S, Asa SL, Chetty R. Intracytoplasmic inclusions (including the so-called “rhabdoid” phenotype) in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2006;17(1):75-81.

18. Shia J, Erlandson RA, Klimstra DS. Whorls of intermediate filaments with entrapped neurosecretory granules correspond to the “rhabdoid” inclusions seen in pancreatic endocrine

neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(2):271-273.

19. Perez-Montiel MD, Frankel WL, Suster S. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas with ‘Rhabdoid’ features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(5):642-649.

1. Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011.

2. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Neuroendocrine Tumors. In: Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010:227-236.

3. Komminoth P, Arnold R, Capella C, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:274-276.

4. Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:13.

5. Price TN, Thompson GB, Lewis JT, Lloyd RV, Young WF. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to primary gastrinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tree: three case reports and review of literature. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(7):737-749.

6. Bhandarwar AH, Shaikh TA, Borisa AD, et al. Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the left hepatic duct: a case report with review of the literature. Case Rep Surg. 2012:786432.

7. Bhalla P, Powle V, Shah RC, Jagannath P. Neuroendocrine tumor of common hepatic duct. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2012;31(3):144-146.

8. Khan FA, Stevens-Chase A, Chaudhry R, Hashmi A, Edelman D, Weaver D. Extrahepatic biliary obstrution secondary to neuroendocrine tumor of the common hepatic duct. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:46-49.

9. Hong N, Kim HJ, Byun JH, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the extrahepatic bile duct: radiologic and clinical characteristics. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(1):181-191.

10. Tonelli F, Giudici F, Nesi G, Batignani G, Brandi ML. Biliary tree gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(45):8312-8320.

11. Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(1):43-83.

12. Pieterman CRC, Conemans EB, Dreijerink KMA, et al. Thoracic and duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: natural history and function of menin in tumorigenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(3):R121-R142.

13. Pipeleers-Marichal M, Somers G, Willems G, et al. Gastrinomas in the duodenums of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(11):723-727.

14. Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al; Endocrine Society. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2990-3011.

15. Eastell R, Brandi ML, Costa AG, et al. Diagnosis of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3570-3579.

16. Michalopoulos N, Papavramidis TS, Karayannopoulou G, Pliakos I, Papavramidis ST, Kanellos I. Neuroendocrine tumors of extrahepatic biliary tract. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;20(4):765-775.

17. Serra S, Asa SL, Chetty R. Intracytoplasmic inclusions (including the so-called “rhabdoid” phenotype) in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2006;17(1):75-81.

18. Shia J, Erlandson RA, Klimstra DS. Whorls of intermediate filaments with entrapped neurosecretory granules correspond to the “rhabdoid” inclusions seen in pancreatic endocrine

neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(2):271-273.

19. Perez-Montiel MD, Frankel WL, Suster S. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas with ‘Rhabdoid’ features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(5):642-649.