User login

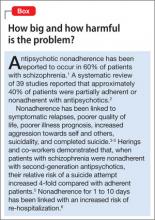

Medication nonadherence is a common problem when treating patients with schizophrenia that can worsen prognosis and lead to sub-optimal treatment outcomes. In this article, we discuss common reasons for nonadherence and describe evidence-based treatments intended to increase adherence and improve outcomes (Box).1-6

Common reasons for nonadherence

The primary predictor of future nonadherence is a history of nonadherence. It is important to understand patients’ reasons for nonadherence so that practical and evidence-based solutions can be implemented into the treatment plans of individual patients.

The 2009 Expert Consensus Guidelines on Adherence Problems in Patients with Serious and Persistent Mental Illness divided variables related to nonadherence into 3 categories:

- those that lie within the patient (intrinsic)

- those that are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, or caregivers (extrinsic)

- those that are related to the healthcare delivery system (extrinsic).7

Among intrinsic variables, studies have shown a correlation between nonadherence and education level, lower socioeconomic status, homelessness, and male sex.7 (The Expert Consensus Guidelines considered homelessness to be an intrinsic factor because it was used as a demographic variable in the studies.)

Cognitive and negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia are an intrinsic risk factor for nonadherence because patients might not remember when or how to take medication.7 In a study by Freudenreich and co-workers8 of 81 outpatients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the presence of negative symptoms predicted a negative attitude toward psychotropic medications. Poor insight might be the result of cognitive dysfunction associated with schizophrenia, and often is due to a lack of awareness of the importance of taking medications.

Limited insight into the need for treatment can be problematic early in the course of the illness when it may be directly related to positive symptoms. Perkins and colleagues9 demonstrated that patients recovering from a first psychotic episode who had limited insight into their illness and lacked desire to seek treatment were less adherent with medication. In another study, 5% of psychiatrists surveyed thought that many of their patients with schizophrenia were nonadherent because those patients did not believe that medications were effective or useful.10

Comorbid substance abuse disorders can contribute to medication nonadherence. In an analysis of 6,731 patients with schizophrenia, Novick and co-workers reported that alcohol dependence and substance abuse in the previous month predicted medication nonadherence.11 Hunt and colleagues demonstrated that, among 99 nonadherent patients with schizophrenia, time to first readmission was shorter for patients with comorbid substance abuse disorders compared with patients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia only. Over the 4-year study period, the 28 patients who had a dual diagnosis (schizophrenia and substance abuse) accounted for 57% of all hospital readmissions.12

Several variables that affect medication adherence are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, caregivers, and the service delivery system.7 These include:

- the perceived stigma of being given a diagnosis of a serious mental illness

- adverse effects related to medications

- poor social and family support

- difficulty gaining access to mental health services.7,10

Societal stigma associated with seeking treatment from a mental health professional may contribute to nonadherence in some patients. In 1 study,13 36% of people surveyed would not want to work closely with a person who has a serious mental illness.

Adverse effects contribute significantly to nonadherence

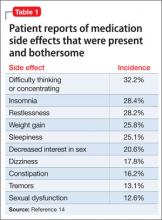

Limited treatment options (which may be expensive) can make it difficult to manage the adverse effects of antipsychotics. In a cross-sectional survey of 876 patients, investigators reported that: 1) <50% of patients were adherent with medication, and 2) 80% experienced ≥1 side effect that was reported to be “somewhat bothersome” in self-ratings (Table 1).14 Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and agitation were most strongly associated with nonadherence; weight gain, akathisia, and sexual dysfunction also were associated with nonadherence.14 This study did not distinguish adverse effects associated with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) from those associated with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), even though 71.7% of patients studied were taking an SGA.

A meta-analysis by Leucht and co-workers15 compared 15 antipsychotics (the FGAs haloperidol and chlorpromazine and 13 SGAs) for efficacy and tolerability in schizophrenia. Haloperidol had the highest rate of discontinuation for any

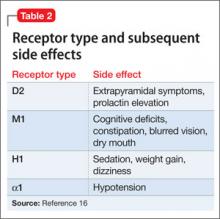

Antipsychotic binding affinities to dopamine 2 (D2), serotonin 2A (5-HT2A), histamine (H1), and other receptors have an impact on a medication’s side-effect profile. Because of individual patient characteristics, you might be faced with choosing a medication that has a lower risk of EPS but a higher risk of weight gain and metabolic complications—or the inverse. Understanding binding affinities, side-effect profiles, and how to minimize or utilize adverse effects (ie, giving a drug that is approved to treat schizophrenia and is associated with weight gain to a patient with schizophrenia who has lost weight) may lead to greater adherence (Table 216 and Table 317).

Adequate support is essential

The therapeutic alliance plays a key role in patients’ attitudes toward taking medication. Magura and colleagues18 found that one-third of psychiatric patients (13% of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia) reported that their psychiatrist did not spend enough time with them explaining side effects, and felt “rushed.”

Patients with schizophrenia often require access to social support systems provided by family members, friends, and community agencies that provide case management and attendant care services. Patients who are adherent to medication tend to have greater perceived family involvement in medication treatment, and tend to have been raised in a family that had more of a positive attitude toward medication.19

In our practice, we have observed that recent state and federal budget cuts have resulted in patients having greater difficulty gaining access to case management and attendant care services, which then leads to increased rates of medication nonadherence. Be aware that variables such as limited office hours, financial hardship, and cultural and language barriers can compromise a patient’s ability to seek and continue care.

In the following section, we lay out techniques for improving adherence in patients with schizophrenia.

Employ general and specific strategies to boost adherence

How can you raise medication adherence concerns with patients, keeping in mind that they often overestimate their adherence?

Ask. Some clinicians ask questions such as “Are you taking your medication?”, although a more effective approach might be to ask how the patient is taking his (her) medication. Asking questions such as “When do you take your medication?” and “In the past week, how many doses do you think you missed?” might be more effective ways to inquire about adherence.7

The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients about medication adherence monthly for those who are stable, doing well, and believed to be adherent. For those who are new to a practice or who are not doing well, inquire about medication adherence at least weekly.7

In our practice, patients who are unstable but do not require inpatient hospitalization typically are seen more often in the clinic, or are referred to intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization programs. If an unstable patient is unable to come in for more frequent appointments, we arrange phone conferences between her and her provider. If a patient is not doing well and has a case manager, we often ask that case manager to visit the patient, in person, more often than he (she) would otherwise.

Take a nonjudgmental approach when raising these issues with patients. Questions such as “We all forget to take our medication sometimes; do you?” help to normalize nonadherence, and improve the therapeutic alliance, and might result in the patient being more honest with the clinician.7 Because patients may be apprehensive about discussing adverse events, clinicians must be proactive about improving the therapeutic alliance and making patients feel comfortable when discussing sensitive topics. Clinicians should try to convey the idea that, although adherence is a concern, so is quality of life. A clinicians’ willingness to take a flexible approach that is nonpunitive nor authoritarian can aid the therapeutic alliance and improve overall adherence.

Be sensitive to financial, cultural, and language variables that can affect access to care. The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients if they can afford their medication. In our practice, we have seen patients with schizophrenia discharged from the hospital only to be readmitted 1 month later because they could not afford to fill their prescriptions.

It is important to have translation services available, in person or by phone, for patients who do not speak English. Furthermore, it is important to understand the limitations that your practice might place on access to care. Ask patients if they have ever had trouble making an appointment when they needed to be seen, or if they called the office with a question and did not receive an answer in a timely fashion; doing so allows you to assess the practice’s ability to meet patients’ needs and helps you build a therapeutic alliance.

Make objective assessments. It is important for practitioners to not base their assessment of medication adherence solely on subjective findings. Asking patients to bring in their medication bottles for pill counts and checking with the patients’ pharmacies for information about refill frequency can provide some objective data. Electronic monitoring systems use microprocessors inserted into bottle caps to record the occurrence and timing of each bottle opening. Studies show that these electronic monitoring systems are the gold standard for determining medication adherence and could be used in cases where it is unclear if the patient is taking his (her) medication.7,20 Such systems have successfully monitored medication adherence in clinical trials, but their use in clinical practice is complicated by ethical and legal considerations and cost issues.

Simplify the regimen. Using medications with once-daily dosing, for example, can help improve adherence. Pfeiffer and co-workers21 found that patients whose medication regimens were changed from once daily to more than once daily experienced a decrease in medication adherence. Conversely, a decrease in dosing frequency was significantly associated with improved adherence. More than once-daily dosing was only weakly associated with poorer adherence among patients already on a stable regimen.

Discussing positive and negative aspects of past medication trials with a patient and inquiring if she prefers a specific medication can be an effective way to build the therapeutic relationship and help with adherence.

Direct patients to psychosocial interventions. These can be broadly classified as:

- educational approaches

- group therapy approaches

- family interventions

- cognitive treatments

- combination approaches.

Psychoeducational approaches have limited effect on improving adherence when delivered to individual patients. However, 1 study showed that psychoeducation was effective at improving adherence when extended to include the patient’s family.22

Motivational interviewing techniques, behavioral approaches, and family interventions are effective at increasing medication adherence. One study looked at the value of training a patient-identified informant to supervise and administer medication. This person, usually a family member or close support, was responsible for obtaining medication from the pharmacy, administering the medication, and recording adherence. After 1 year, 67% of patients who used an informant were adherent, compared with only 45% in the group that did not have informant support.22 Case managers, attendant care workers, home health nurses, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams also can participate in this manner; it is important, therefore, for you to be aware of the resources available in your community and to understand your role as patient advocate.

Substance abuse is a strong risk factor for nonadherence among patients with schizophrenia,18 which makes it important to assess patients for substance use and encourage those who do abuse to seek treatment. Although 1 study showed no correlation between Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) attendance and medication adherence,12 many AA and Narcotics Anonymous groups do not discuss psychiatric medications during group meetings. Magura and colleagues encouraged the use of “dual focus” groups that involve mental health professionals and addiction treatment specialists discussing mental health and substance abuse issues at the same setting.18

Prescribe long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Typically, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are reserved for patients who have a history of nonadherence. In a small study (N = 97) comparing LAI risperidone and oral risperidone or oral haloperidol, patients treated with an LAI had significantly fewer all-cause discontinuations (26.0%, compared with 70.2%) at 24 months.23 The Adherence to Treatment and Therapeutic Strategies in Schizophrenic Patients study examined 1,848 patients with schizophrenia and reached similar findings regarding LAI antipsychotics.24 (Note: Aripiprazole, fluphenazine, haloperidol, olanzapine, and paliperidone also are available in an LAI formulation.)

Bottom Line

Antipsychotic nonadherence in schizophrenia is a major problem for patients, families, and society. Being able to identify patients at risk for nonadherence, understanding the reasons for their nonadherence, and seeking practical solutions to the problem are all the responsibility of the treating physician. Psychoeducation, addressing substance abuse, modifying dosing, and using long-acting injectable antipsychotics may help improve adherence.

Related Resources

- Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the Expert Consensus Guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. www.nami.org.

- Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) Organization. www.actassociation.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Clozapine • Clozaril Fluphenazine • Permitil Haloperidol • Haldol Iloperidone • Fanapt Olanzapine • Zyprexa Paliperidone • Invega Perphenazine • Trilafon Quetiapine • Seroquel Risperidone • Risperdal Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Macaluso has been the principal investigator for clinical trials for AbbVie, Eisai, Envivo, Janssen, Naurex, and Pfizer. All clinical trial and study contracts and payments were made through the Kansas University Medical Center Research Institute. Dr. McKnight reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sun SX, Liu GG, Christensen DB, et al. Review and analysis of hospitalization costs associated with antipsychotic nonadherence in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2305-2312.

2. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892-909.

3. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637-651.

4. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al. Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):216-222.

5. Herings RM, Erkens JA. Increased suicide attempt rate among patients interrupting use of atypical antipsychotics. Pharmacoepidemial Drug Saf. 2003;12(5):423-424.

6. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):886-891.

7. Velligan D, Weiden P, Sajatovic M, et al. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(1):34-45.

8. Freudenreich O, Cather C, Evins A, et al. Attitudes of schizophrenia outpatients toward psychiatric medications: relationship to clinical variables and insight. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1372-1376.

9. Perkins DO, Johnson JL, Hamer RM, et al. Predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence in patients recovering from a first psychotic episode. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):53-63.

10. Olivares JM, Alptekin K, Azorin JM, et al. Psychiatrists’ awareness of adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia: results from a survey conducted across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:121-132.

11. Novick D, Haro J, Suarez D, et al. Predictors and clinical consequences of nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(2-3):109-113.

12. Hunt GE, Bergen J, Bashir M, et al. Medication compliance and comorbid substance abuse in schizophrenia: impact on community survival four years after a relapse. Schizophr Res. 2002;54(3):253-264.

13. McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Effects of news media messages about mass shootings on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and public support for gun control policies. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(5):494-501.

14. DiBonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, et al. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:20.

15. Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;1382(9896): 951-962.

16. Robinson DS. Antipsychotics: pharmacology and clinical decision making. Primary Psychiatry. 2007;14(10):23-25.

17. Robinson D, Correll CU, Kane JM, et al. Practical dosing strategies in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2010;15:4(suppl 6):1-16.

18. Magura S, Rosenblum A, Fong C. Factors associated with medication adherence among psychiatric outpatients at substance abuse risk. Open Addict J. 2011;4:58-64.

19. Baloush-Kleinman V, Levine SZ, Roe D, et al. Adherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a six-month naturalistic follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):176-181.

20. Byerly M, Nakonezny P, Lescouflair E. Antipsychotic medication adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:437-452.

21. Pfeiffer PN, Ganoczy D, Valenstein M. Dosing frequency and adherence to antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1207-1210.

22. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Irfan M, et al. Schizophrenia medication adherence in a resource-poor setting: randomized controlled trial of supervised treatment in out-patients for schizophrenia (STOPS). Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):467-472.

23. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Oral vs injectable antipsychotic treatment in early psychosis: post hoc comparison of two studies. Clin Ther. 2008;30(12):2378-2386.

24. Gutierrez-Casares JR, Canãs F, Rodriguez-Morales A, et al. Adherence to treatment and therapeutic strategies in schizophrenic patients: the ADHERE study. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(5):327-337.

Medication nonadherence is a common problem when treating patients with schizophrenia that can worsen prognosis and lead to sub-optimal treatment outcomes. In this article, we discuss common reasons for nonadherence and describe evidence-based treatments intended to increase adherence and improve outcomes (Box).1-6

Common reasons for nonadherence

The primary predictor of future nonadherence is a history of nonadherence. It is important to understand patients’ reasons for nonadherence so that practical and evidence-based solutions can be implemented into the treatment plans of individual patients.

The 2009 Expert Consensus Guidelines on Adherence Problems in Patients with Serious and Persistent Mental Illness divided variables related to nonadherence into 3 categories:

- those that lie within the patient (intrinsic)

- those that are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, or caregivers (extrinsic)

- those that are related to the healthcare delivery system (extrinsic).7

Among intrinsic variables, studies have shown a correlation between nonadherence and education level, lower socioeconomic status, homelessness, and male sex.7 (The Expert Consensus Guidelines considered homelessness to be an intrinsic factor because it was used as a demographic variable in the studies.)

Cognitive and negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia are an intrinsic risk factor for nonadherence because patients might not remember when or how to take medication.7 In a study by Freudenreich and co-workers8 of 81 outpatients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the presence of negative symptoms predicted a negative attitude toward psychotropic medications. Poor insight might be the result of cognitive dysfunction associated with schizophrenia, and often is due to a lack of awareness of the importance of taking medications.

Limited insight into the need for treatment can be problematic early in the course of the illness when it may be directly related to positive symptoms. Perkins and colleagues9 demonstrated that patients recovering from a first psychotic episode who had limited insight into their illness and lacked desire to seek treatment were less adherent with medication. In another study, 5% of psychiatrists surveyed thought that many of their patients with schizophrenia were nonadherent because those patients did not believe that medications were effective or useful.10

Comorbid substance abuse disorders can contribute to medication nonadherence. In an analysis of 6,731 patients with schizophrenia, Novick and co-workers reported that alcohol dependence and substance abuse in the previous month predicted medication nonadherence.11 Hunt and colleagues demonstrated that, among 99 nonadherent patients with schizophrenia, time to first readmission was shorter for patients with comorbid substance abuse disorders compared with patients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia only. Over the 4-year study period, the 28 patients who had a dual diagnosis (schizophrenia and substance abuse) accounted for 57% of all hospital readmissions.12

Several variables that affect medication adherence are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, caregivers, and the service delivery system.7 These include:

- the perceived stigma of being given a diagnosis of a serious mental illness

- adverse effects related to medications

- poor social and family support

- difficulty gaining access to mental health services.7,10

Societal stigma associated with seeking treatment from a mental health professional may contribute to nonadherence in some patients. In 1 study,13 36% of people surveyed would not want to work closely with a person who has a serious mental illness.

Adverse effects contribute significantly to nonadherence

Limited treatment options (which may be expensive) can make it difficult to manage the adverse effects of antipsychotics. In a cross-sectional survey of 876 patients, investigators reported that: 1) <50% of patients were adherent with medication, and 2) 80% experienced ≥1 side effect that was reported to be “somewhat bothersome” in self-ratings (Table 1).14 Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and agitation were most strongly associated with nonadherence; weight gain, akathisia, and sexual dysfunction also were associated with nonadherence.14 This study did not distinguish adverse effects associated with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) from those associated with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), even though 71.7% of patients studied were taking an SGA.

A meta-analysis by Leucht and co-workers15 compared 15 antipsychotics (the FGAs haloperidol and chlorpromazine and 13 SGAs) for efficacy and tolerability in schizophrenia. Haloperidol had the highest rate of discontinuation for any

Antipsychotic binding affinities to dopamine 2 (D2), serotonin 2A (5-HT2A), histamine (H1), and other receptors have an impact on a medication’s side-effect profile. Because of individual patient characteristics, you might be faced with choosing a medication that has a lower risk of EPS but a higher risk of weight gain and metabolic complications—or the inverse. Understanding binding affinities, side-effect profiles, and how to minimize or utilize adverse effects (ie, giving a drug that is approved to treat schizophrenia and is associated with weight gain to a patient with schizophrenia who has lost weight) may lead to greater adherence (Table 216 and Table 317).

Adequate support is essential

The therapeutic alliance plays a key role in patients’ attitudes toward taking medication. Magura and colleagues18 found that one-third of psychiatric patients (13% of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia) reported that their psychiatrist did not spend enough time with them explaining side effects, and felt “rushed.”

Patients with schizophrenia often require access to social support systems provided by family members, friends, and community agencies that provide case management and attendant care services. Patients who are adherent to medication tend to have greater perceived family involvement in medication treatment, and tend to have been raised in a family that had more of a positive attitude toward medication.19

In our practice, we have observed that recent state and federal budget cuts have resulted in patients having greater difficulty gaining access to case management and attendant care services, which then leads to increased rates of medication nonadherence. Be aware that variables such as limited office hours, financial hardship, and cultural and language barriers can compromise a patient’s ability to seek and continue care.

In the following section, we lay out techniques for improving adherence in patients with schizophrenia.

Employ general and specific strategies to boost adherence

How can you raise medication adherence concerns with patients, keeping in mind that they often overestimate their adherence?

Ask. Some clinicians ask questions such as “Are you taking your medication?”, although a more effective approach might be to ask how the patient is taking his (her) medication. Asking questions such as “When do you take your medication?” and “In the past week, how many doses do you think you missed?” might be more effective ways to inquire about adherence.7

The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients about medication adherence monthly for those who are stable, doing well, and believed to be adherent. For those who are new to a practice or who are not doing well, inquire about medication adherence at least weekly.7

In our practice, patients who are unstable but do not require inpatient hospitalization typically are seen more often in the clinic, or are referred to intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization programs. If an unstable patient is unable to come in for more frequent appointments, we arrange phone conferences between her and her provider. If a patient is not doing well and has a case manager, we often ask that case manager to visit the patient, in person, more often than he (she) would otherwise.

Take a nonjudgmental approach when raising these issues with patients. Questions such as “We all forget to take our medication sometimes; do you?” help to normalize nonadherence, and improve the therapeutic alliance, and might result in the patient being more honest with the clinician.7 Because patients may be apprehensive about discussing adverse events, clinicians must be proactive about improving the therapeutic alliance and making patients feel comfortable when discussing sensitive topics. Clinicians should try to convey the idea that, although adherence is a concern, so is quality of life. A clinicians’ willingness to take a flexible approach that is nonpunitive nor authoritarian can aid the therapeutic alliance and improve overall adherence.

Be sensitive to financial, cultural, and language variables that can affect access to care. The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients if they can afford their medication. In our practice, we have seen patients with schizophrenia discharged from the hospital only to be readmitted 1 month later because they could not afford to fill their prescriptions.

It is important to have translation services available, in person or by phone, for patients who do not speak English. Furthermore, it is important to understand the limitations that your practice might place on access to care. Ask patients if they have ever had trouble making an appointment when they needed to be seen, or if they called the office with a question and did not receive an answer in a timely fashion; doing so allows you to assess the practice’s ability to meet patients’ needs and helps you build a therapeutic alliance.

Make objective assessments. It is important for practitioners to not base their assessment of medication adherence solely on subjective findings. Asking patients to bring in their medication bottles for pill counts and checking with the patients’ pharmacies for information about refill frequency can provide some objective data. Electronic monitoring systems use microprocessors inserted into bottle caps to record the occurrence and timing of each bottle opening. Studies show that these electronic monitoring systems are the gold standard for determining medication adherence and could be used in cases where it is unclear if the patient is taking his (her) medication.7,20 Such systems have successfully monitored medication adherence in clinical trials, but their use in clinical practice is complicated by ethical and legal considerations and cost issues.

Simplify the regimen. Using medications with once-daily dosing, for example, can help improve adherence. Pfeiffer and co-workers21 found that patients whose medication regimens were changed from once daily to more than once daily experienced a decrease in medication adherence. Conversely, a decrease in dosing frequency was significantly associated with improved adherence. More than once-daily dosing was only weakly associated with poorer adherence among patients already on a stable regimen.

Discussing positive and negative aspects of past medication trials with a patient and inquiring if she prefers a specific medication can be an effective way to build the therapeutic relationship and help with adherence.

Direct patients to psychosocial interventions. These can be broadly classified as:

- educational approaches

- group therapy approaches

- family interventions

- cognitive treatments

- combination approaches.

Psychoeducational approaches have limited effect on improving adherence when delivered to individual patients. However, 1 study showed that psychoeducation was effective at improving adherence when extended to include the patient’s family.22

Motivational interviewing techniques, behavioral approaches, and family interventions are effective at increasing medication adherence. One study looked at the value of training a patient-identified informant to supervise and administer medication. This person, usually a family member or close support, was responsible for obtaining medication from the pharmacy, administering the medication, and recording adherence. After 1 year, 67% of patients who used an informant were adherent, compared with only 45% in the group that did not have informant support.22 Case managers, attendant care workers, home health nurses, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams also can participate in this manner; it is important, therefore, for you to be aware of the resources available in your community and to understand your role as patient advocate.

Substance abuse is a strong risk factor for nonadherence among patients with schizophrenia,18 which makes it important to assess patients for substance use and encourage those who do abuse to seek treatment. Although 1 study showed no correlation between Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) attendance and medication adherence,12 many AA and Narcotics Anonymous groups do not discuss psychiatric medications during group meetings. Magura and colleagues encouraged the use of “dual focus” groups that involve mental health professionals and addiction treatment specialists discussing mental health and substance abuse issues at the same setting.18

Prescribe long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Typically, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are reserved for patients who have a history of nonadherence. In a small study (N = 97) comparing LAI risperidone and oral risperidone or oral haloperidol, patients treated with an LAI had significantly fewer all-cause discontinuations (26.0%, compared with 70.2%) at 24 months.23 The Adherence to Treatment and Therapeutic Strategies in Schizophrenic Patients study examined 1,848 patients with schizophrenia and reached similar findings regarding LAI antipsychotics.24 (Note: Aripiprazole, fluphenazine, haloperidol, olanzapine, and paliperidone also are available in an LAI formulation.)

Bottom Line

Antipsychotic nonadherence in schizophrenia is a major problem for patients, families, and society. Being able to identify patients at risk for nonadherence, understanding the reasons for their nonadherence, and seeking practical solutions to the problem are all the responsibility of the treating physician. Psychoeducation, addressing substance abuse, modifying dosing, and using long-acting injectable antipsychotics may help improve adherence.

Related Resources

- Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the Expert Consensus Guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. www.nami.org.

- Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) Organization. www.actassociation.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Clozapine • Clozaril Fluphenazine • Permitil Haloperidol • Haldol Iloperidone • Fanapt Olanzapine • Zyprexa Paliperidone • Invega Perphenazine • Trilafon Quetiapine • Seroquel Risperidone • Risperdal Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Macaluso has been the principal investigator for clinical trials for AbbVie, Eisai, Envivo, Janssen, Naurex, and Pfizer. All clinical trial and study contracts and payments were made through the Kansas University Medical Center Research Institute. Dr. McKnight reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Medication nonadherence is a common problem when treating patients with schizophrenia that can worsen prognosis and lead to sub-optimal treatment outcomes. In this article, we discuss common reasons for nonadherence and describe evidence-based treatments intended to increase adherence and improve outcomes (Box).1-6

Common reasons for nonadherence

The primary predictor of future nonadherence is a history of nonadherence. It is important to understand patients’ reasons for nonadherence so that practical and evidence-based solutions can be implemented into the treatment plans of individual patients.

The 2009 Expert Consensus Guidelines on Adherence Problems in Patients with Serious and Persistent Mental Illness divided variables related to nonadherence into 3 categories:

- those that lie within the patient (intrinsic)

- those that are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, or caregivers (extrinsic)

- those that are related to the healthcare delivery system (extrinsic).7

Among intrinsic variables, studies have shown a correlation between nonadherence and education level, lower socioeconomic status, homelessness, and male sex.7 (The Expert Consensus Guidelines considered homelessness to be an intrinsic factor because it was used as a demographic variable in the studies.)

Cognitive and negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia are an intrinsic risk factor for nonadherence because patients might not remember when or how to take medication.7 In a study by Freudenreich and co-workers8 of 81 outpatients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the presence of negative symptoms predicted a negative attitude toward psychotropic medications. Poor insight might be the result of cognitive dysfunction associated with schizophrenia, and often is due to a lack of awareness of the importance of taking medications.

Limited insight into the need for treatment can be problematic early in the course of the illness when it may be directly related to positive symptoms. Perkins and colleagues9 demonstrated that patients recovering from a first psychotic episode who had limited insight into their illness and lacked desire to seek treatment were less adherent with medication. In another study, 5% of psychiatrists surveyed thought that many of their patients with schizophrenia were nonadherent because those patients did not believe that medications were effective or useful.10

Comorbid substance abuse disorders can contribute to medication nonadherence. In an analysis of 6,731 patients with schizophrenia, Novick and co-workers reported that alcohol dependence and substance abuse in the previous month predicted medication nonadherence.11 Hunt and colleagues demonstrated that, among 99 nonadherent patients with schizophrenia, time to first readmission was shorter for patients with comorbid substance abuse disorders compared with patients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia only. Over the 4-year study period, the 28 patients who had a dual diagnosis (schizophrenia and substance abuse) accounted for 57% of all hospital readmissions.12

Several variables that affect medication adherence are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, caregivers, and the service delivery system.7 These include:

- the perceived stigma of being given a diagnosis of a serious mental illness

- adverse effects related to medications

- poor social and family support

- difficulty gaining access to mental health services.7,10

Societal stigma associated with seeking treatment from a mental health professional may contribute to nonadherence in some patients. In 1 study,13 36% of people surveyed would not want to work closely with a person who has a serious mental illness.

Adverse effects contribute significantly to nonadherence

Limited treatment options (which may be expensive) can make it difficult to manage the adverse effects of antipsychotics. In a cross-sectional survey of 876 patients, investigators reported that: 1) <50% of patients were adherent with medication, and 2) 80% experienced ≥1 side effect that was reported to be “somewhat bothersome” in self-ratings (Table 1).14 Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and agitation were most strongly associated with nonadherence; weight gain, akathisia, and sexual dysfunction also were associated with nonadherence.14 This study did not distinguish adverse effects associated with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) from those associated with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), even though 71.7% of patients studied were taking an SGA.

A meta-analysis by Leucht and co-workers15 compared 15 antipsychotics (the FGAs haloperidol and chlorpromazine and 13 SGAs) for efficacy and tolerability in schizophrenia. Haloperidol had the highest rate of discontinuation for any

Antipsychotic binding affinities to dopamine 2 (D2), serotonin 2A (5-HT2A), histamine (H1), and other receptors have an impact on a medication’s side-effect profile. Because of individual patient characteristics, you might be faced with choosing a medication that has a lower risk of EPS but a higher risk of weight gain and metabolic complications—or the inverse. Understanding binding affinities, side-effect profiles, and how to minimize or utilize adverse effects (ie, giving a drug that is approved to treat schizophrenia and is associated with weight gain to a patient with schizophrenia who has lost weight) may lead to greater adherence (Table 216 and Table 317).

Adequate support is essential

The therapeutic alliance plays a key role in patients’ attitudes toward taking medication. Magura and colleagues18 found that one-third of psychiatric patients (13% of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia) reported that their psychiatrist did not spend enough time with them explaining side effects, and felt “rushed.”

Patients with schizophrenia often require access to social support systems provided by family members, friends, and community agencies that provide case management and attendant care services. Patients who are adherent to medication tend to have greater perceived family involvement in medication treatment, and tend to have been raised in a family that had more of a positive attitude toward medication.19

In our practice, we have observed that recent state and federal budget cuts have resulted in patients having greater difficulty gaining access to case management and attendant care services, which then leads to increased rates of medication nonadherence. Be aware that variables such as limited office hours, financial hardship, and cultural and language barriers can compromise a patient’s ability to seek and continue care.

In the following section, we lay out techniques for improving adherence in patients with schizophrenia.

Employ general and specific strategies to boost adherence

How can you raise medication adherence concerns with patients, keeping in mind that they often overestimate their adherence?

Ask. Some clinicians ask questions such as “Are you taking your medication?”, although a more effective approach might be to ask how the patient is taking his (her) medication. Asking questions such as “When do you take your medication?” and “In the past week, how many doses do you think you missed?” might be more effective ways to inquire about adherence.7

The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients about medication adherence monthly for those who are stable, doing well, and believed to be adherent. For those who are new to a practice or who are not doing well, inquire about medication adherence at least weekly.7

In our practice, patients who are unstable but do not require inpatient hospitalization typically are seen more often in the clinic, or are referred to intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization programs. If an unstable patient is unable to come in for more frequent appointments, we arrange phone conferences between her and her provider. If a patient is not doing well and has a case manager, we often ask that case manager to visit the patient, in person, more often than he (she) would otherwise.

Take a nonjudgmental approach when raising these issues with patients. Questions such as “We all forget to take our medication sometimes; do you?” help to normalize nonadherence, and improve the therapeutic alliance, and might result in the patient being more honest with the clinician.7 Because patients may be apprehensive about discussing adverse events, clinicians must be proactive about improving the therapeutic alliance and making patients feel comfortable when discussing sensitive topics. Clinicians should try to convey the idea that, although adherence is a concern, so is quality of life. A clinicians’ willingness to take a flexible approach that is nonpunitive nor authoritarian can aid the therapeutic alliance and improve overall adherence.

Be sensitive to financial, cultural, and language variables that can affect access to care. The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients if they can afford their medication. In our practice, we have seen patients with schizophrenia discharged from the hospital only to be readmitted 1 month later because they could not afford to fill their prescriptions.

It is important to have translation services available, in person or by phone, for patients who do not speak English. Furthermore, it is important to understand the limitations that your practice might place on access to care. Ask patients if they have ever had trouble making an appointment when they needed to be seen, or if they called the office with a question and did not receive an answer in a timely fashion; doing so allows you to assess the practice’s ability to meet patients’ needs and helps you build a therapeutic alliance.

Make objective assessments. It is important for practitioners to not base their assessment of medication adherence solely on subjective findings. Asking patients to bring in their medication bottles for pill counts and checking with the patients’ pharmacies for information about refill frequency can provide some objective data. Electronic monitoring systems use microprocessors inserted into bottle caps to record the occurrence and timing of each bottle opening. Studies show that these electronic monitoring systems are the gold standard for determining medication adherence and could be used in cases where it is unclear if the patient is taking his (her) medication.7,20 Such systems have successfully monitored medication adherence in clinical trials, but their use in clinical practice is complicated by ethical and legal considerations and cost issues.

Simplify the regimen. Using medications with once-daily dosing, for example, can help improve adherence. Pfeiffer and co-workers21 found that patients whose medication regimens were changed from once daily to more than once daily experienced a decrease in medication adherence. Conversely, a decrease in dosing frequency was significantly associated with improved adherence. More than once-daily dosing was only weakly associated with poorer adherence among patients already on a stable regimen.

Discussing positive and negative aspects of past medication trials with a patient and inquiring if she prefers a specific medication can be an effective way to build the therapeutic relationship and help with adherence.

Direct patients to psychosocial interventions. These can be broadly classified as:

- educational approaches

- group therapy approaches

- family interventions

- cognitive treatments

- combination approaches.

Psychoeducational approaches have limited effect on improving adherence when delivered to individual patients. However, 1 study showed that psychoeducation was effective at improving adherence when extended to include the patient’s family.22

Motivational interviewing techniques, behavioral approaches, and family interventions are effective at increasing medication adherence. One study looked at the value of training a patient-identified informant to supervise and administer medication. This person, usually a family member or close support, was responsible for obtaining medication from the pharmacy, administering the medication, and recording adherence. After 1 year, 67% of patients who used an informant were adherent, compared with only 45% in the group that did not have informant support.22 Case managers, attendant care workers, home health nurses, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams also can participate in this manner; it is important, therefore, for you to be aware of the resources available in your community and to understand your role as patient advocate.

Substance abuse is a strong risk factor for nonadherence among patients with schizophrenia,18 which makes it important to assess patients for substance use and encourage those who do abuse to seek treatment. Although 1 study showed no correlation between Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) attendance and medication adherence,12 many AA and Narcotics Anonymous groups do not discuss psychiatric medications during group meetings. Magura and colleagues encouraged the use of “dual focus” groups that involve mental health professionals and addiction treatment specialists discussing mental health and substance abuse issues at the same setting.18

Prescribe long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Typically, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are reserved for patients who have a history of nonadherence. In a small study (N = 97) comparing LAI risperidone and oral risperidone or oral haloperidol, patients treated with an LAI had significantly fewer all-cause discontinuations (26.0%, compared with 70.2%) at 24 months.23 The Adherence to Treatment and Therapeutic Strategies in Schizophrenic Patients study examined 1,848 patients with schizophrenia and reached similar findings regarding LAI antipsychotics.24 (Note: Aripiprazole, fluphenazine, haloperidol, olanzapine, and paliperidone also are available in an LAI formulation.)

Bottom Line

Antipsychotic nonadherence in schizophrenia is a major problem for patients, families, and society. Being able to identify patients at risk for nonadherence, understanding the reasons for their nonadherence, and seeking practical solutions to the problem are all the responsibility of the treating physician. Psychoeducation, addressing substance abuse, modifying dosing, and using long-acting injectable antipsychotics may help improve adherence.

Related Resources

- Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the Expert Consensus Guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. www.nami.org.

- Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) Organization. www.actassociation.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Clozapine • Clozaril Fluphenazine • Permitil Haloperidol • Haldol Iloperidone • Fanapt Olanzapine • Zyprexa Paliperidone • Invega Perphenazine • Trilafon Quetiapine • Seroquel Risperidone • Risperdal Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Macaluso has been the principal investigator for clinical trials for AbbVie, Eisai, Envivo, Janssen, Naurex, and Pfizer. All clinical trial and study contracts and payments were made through the Kansas University Medical Center Research Institute. Dr. McKnight reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sun SX, Liu GG, Christensen DB, et al. Review and analysis of hospitalization costs associated with antipsychotic nonadherence in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2305-2312.

2. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892-909.

3. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637-651.

4. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al. Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):216-222.

5. Herings RM, Erkens JA. Increased suicide attempt rate among patients interrupting use of atypical antipsychotics. Pharmacoepidemial Drug Saf. 2003;12(5):423-424.

6. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):886-891.

7. Velligan D, Weiden P, Sajatovic M, et al. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(1):34-45.

8. Freudenreich O, Cather C, Evins A, et al. Attitudes of schizophrenia outpatients toward psychiatric medications: relationship to clinical variables and insight. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1372-1376.

9. Perkins DO, Johnson JL, Hamer RM, et al. Predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence in patients recovering from a first psychotic episode. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):53-63.

10. Olivares JM, Alptekin K, Azorin JM, et al. Psychiatrists’ awareness of adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia: results from a survey conducted across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:121-132.

11. Novick D, Haro J, Suarez D, et al. Predictors and clinical consequences of nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(2-3):109-113.

12. Hunt GE, Bergen J, Bashir M, et al. Medication compliance and comorbid substance abuse in schizophrenia: impact on community survival four years after a relapse. Schizophr Res. 2002;54(3):253-264.

13. McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Effects of news media messages about mass shootings on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and public support for gun control policies. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(5):494-501.

14. DiBonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, et al. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:20.

15. Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;1382(9896): 951-962.

16. Robinson DS. Antipsychotics: pharmacology and clinical decision making. Primary Psychiatry. 2007;14(10):23-25.

17. Robinson D, Correll CU, Kane JM, et al. Practical dosing strategies in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2010;15:4(suppl 6):1-16.

18. Magura S, Rosenblum A, Fong C. Factors associated with medication adherence among psychiatric outpatients at substance abuse risk. Open Addict J. 2011;4:58-64.

19. Baloush-Kleinman V, Levine SZ, Roe D, et al. Adherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a six-month naturalistic follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):176-181.

20. Byerly M, Nakonezny P, Lescouflair E. Antipsychotic medication adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:437-452.

21. Pfeiffer PN, Ganoczy D, Valenstein M. Dosing frequency and adherence to antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1207-1210.

22. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Irfan M, et al. Schizophrenia medication adherence in a resource-poor setting: randomized controlled trial of supervised treatment in out-patients for schizophrenia (STOPS). Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):467-472.

23. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Oral vs injectable antipsychotic treatment in early psychosis: post hoc comparison of two studies. Clin Ther. 2008;30(12):2378-2386.

24. Gutierrez-Casares JR, Canãs F, Rodriguez-Morales A, et al. Adherence to treatment and therapeutic strategies in schizophrenic patients: the ADHERE study. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(5):327-337.

1. Sun SX, Liu GG, Christensen DB, et al. Review and analysis of hospitalization costs associated with antipsychotic nonadherence in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2305-2312.

2. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892-909.

3. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637-651.

4. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al. Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):216-222.

5. Herings RM, Erkens JA. Increased suicide attempt rate among patients interrupting use of atypical antipsychotics. Pharmacoepidemial Drug Saf. 2003;12(5):423-424.

6. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):886-891.

7. Velligan D, Weiden P, Sajatovic M, et al. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(1):34-45.

8. Freudenreich O, Cather C, Evins A, et al. Attitudes of schizophrenia outpatients toward psychiatric medications: relationship to clinical variables and insight. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1372-1376.

9. Perkins DO, Johnson JL, Hamer RM, et al. Predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence in patients recovering from a first psychotic episode. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):53-63.

10. Olivares JM, Alptekin K, Azorin JM, et al. Psychiatrists’ awareness of adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia: results from a survey conducted across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:121-132.

11. Novick D, Haro J, Suarez D, et al. Predictors and clinical consequences of nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(2-3):109-113.

12. Hunt GE, Bergen J, Bashir M, et al. Medication compliance and comorbid substance abuse in schizophrenia: impact on community survival four years after a relapse. Schizophr Res. 2002;54(3):253-264.

13. McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Effects of news media messages about mass shootings on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and public support for gun control policies. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(5):494-501.

14. DiBonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, et al. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:20.

15. Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;1382(9896): 951-962.

16. Robinson DS. Antipsychotics: pharmacology and clinical decision making. Primary Psychiatry. 2007;14(10):23-25.

17. Robinson D, Correll CU, Kane JM, et al. Practical dosing strategies in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2010;15:4(suppl 6):1-16.

18. Magura S, Rosenblum A, Fong C. Factors associated with medication adherence among psychiatric outpatients at substance abuse risk. Open Addict J. 2011;4:58-64.

19. Baloush-Kleinman V, Levine SZ, Roe D, et al. Adherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a six-month naturalistic follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):176-181.

20. Byerly M, Nakonezny P, Lescouflair E. Antipsychotic medication adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:437-452.

21. Pfeiffer PN, Ganoczy D, Valenstein M. Dosing frequency and adherence to antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1207-1210.

22. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Irfan M, et al. Schizophrenia medication adherence in a resource-poor setting: randomized controlled trial of supervised treatment in out-patients for schizophrenia (STOPS). Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):467-472.

23. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Oral vs injectable antipsychotic treatment in early psychosis: post hoc comparison of two studies. Clin Ther. 2008;30(12):2378-2386.

24. Gutierrez-Casares JR, Canãs F, Rodriguez-Morales A, et al. Adherence to treatment and therapeutic strategies in schizophrenic patients: the ADHERE study. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(5):327-337.