User login

Lacey, 37, is seen by her primary care provider (PCP) as follow-up to a visit she made to the emergency department (ED). She has gone to the ED four times in the past year. Each time, she presents with tachycardia, dyspnea, nausea, numbness in her extremities, and a fear that she is having a heart attack. Despite negative workups at each visit (ECG, cardiac enzymes, complete blood count, toxicology screen, Holter monitoring), Lacey is terrified that the ED doctors are missing something. She is still “rattled” by the chest pain and shortness of breath she experiences. Mild symptoms are persisting, and she is worried that she will have a heart attack and die without the treatment she believes she needs. How do you proceed?

Panic disorder (PD) is characterized by the spontaneous and unexpected occurrence of panic attacks and by at least one month of persistent worry about having another attack or significant maladaptive behaviors related to the attack. Frequency of such attacks can vary from several a day to only a few per year. In a panic attack, an intense fear develops abruptly and peaks within 10 minutes of onset. At least four of the following 13 symptoms must accompany the attack, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5)

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feeling of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

- Fear of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling sensations)

- Chills or hot flushes.1

Lifetime incidence rates of PD are 1% to 3% for the general population.2 A closer look at patients presenting to the ED with chest pain reveals that 17% to 25% meet criteria for PD.3,4 And an estimated 6% of individuals experiencing a panic attack present to their primary care provider.5 Patients with PD tend to use health care resources at a disproportionately high rate.6

An international review of PD research suggests the average age of onset is 32 years.7 Triggers can vary widely, and no single stressor has been identified. The exact cause of PD is unknown, but a convergence of social and biological influences (including involvement of the amygdala) are implicated in its development.6 For individuals who have had a panic attack, 66.5% will have recurrent attacks.7 Lifetime prevalence of panic attacks is 13.2%.7

Differential goes far beyond myocardial infarction. Many medical conditions can mimic PD symptoms: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic diseases; endocrine diseases (eg, hyperthyroidism); drug intoxication (eg, stimulants [cocaine, amphetamines]); drug withdrawal (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, sedative-hypnotics); and ingestion of excessive quantities of caffeine. Common comorbid medical disorders include asthma, coronary artery disease, cancer, thyroid disease, hypertension, ulcer, and migraine headaches.8

When patients present with paniclike symptoms, suspect a possible medical condition when those symptoms include ataxia, altered mental status, or loss of bladder control, or when onset of panic symptoms occur later in life for a patient with no significant psychiatric history.

RULE OUT ORGANIC CAUSES

In addition to obtaining a complete history and doing a physical exam on patients with paniclike symptoms, you’ll also need to ensure that the following are done: a neurologic examination, standard laboratory testing (thyroid function, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel), and possible additional testing (eg, urine toxicology screen and

If organic causes are ruled out, focus on a psychiatric assessment, including

- History of the present illness (onset, symptoms, frequency, predisposing/precipitating factors)

- Psychiatric history

- History of substance use

- Family history of psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders)

- Social history (life events, including those preceding the onset of panic; history of child abuse)

- Medications

- Mental status examination

- Safety (PD is associated with higher risk for suicidal ideation).9

TREATMENT INCLUDES CBT AND MEDICATION

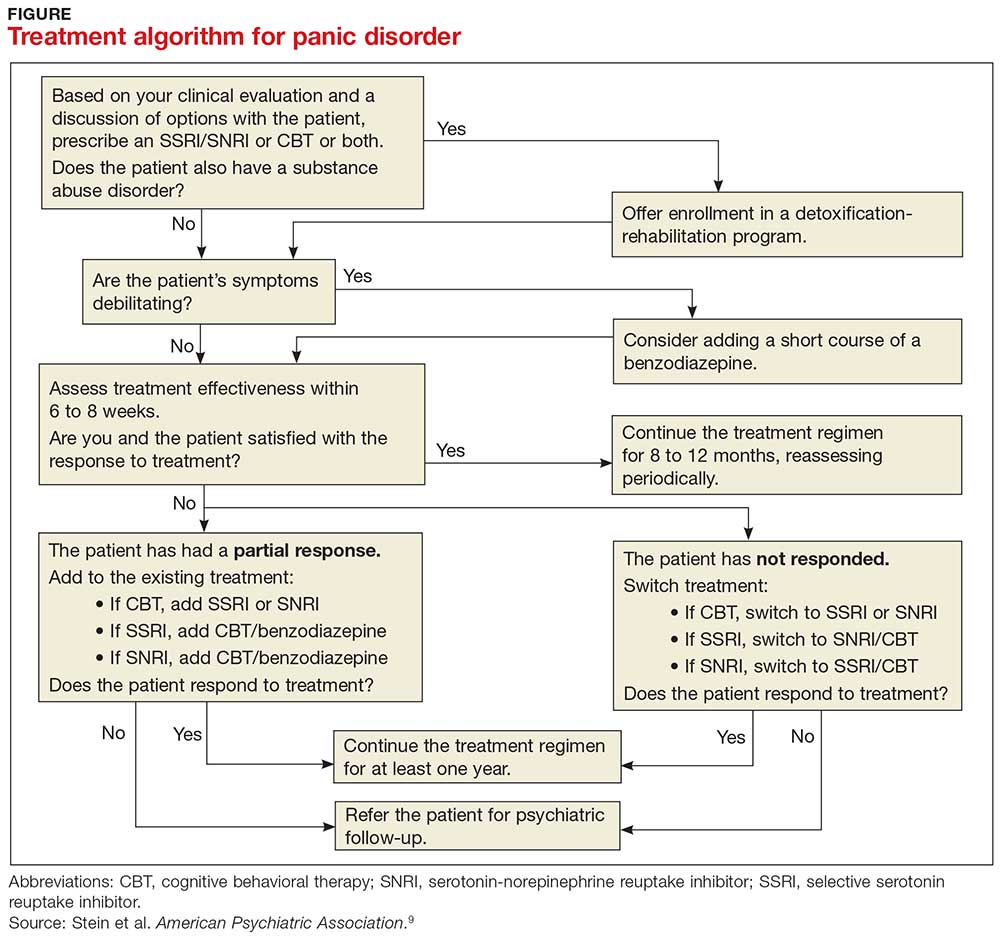

PD is a chronic disease with a variable course, but the long-term prognosis is good. PD is usually treated in an outpatient setting. Consider hospitalization if the patient is suicidal, if the potential for life-threatening withdrawal symptoms is high (as with alcohol or benzodiazepines), or if the symptoms are severely debilitating or attempted outpatient treatment is unsuccessful. Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions are used for PD (see Figure), although there is not enough evidence to recommend one versus the other or combination therapy versus monotherapy.9

All Lacey’s test results come back negative, and the psychiatric assessment reveals that she meets the DSM-5 criteria for PD. Counting on the strength of their relationship, her PCP talks to her about PD and discusses treatment options, which include counseling, medication, or both. Lacey agrees to a referral for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a psychologist embedded at her primary care clinic and to begin taking medication. Her PCP starts her on sertraline 25 mg/d.

In CBT, Lacey’s psychologist teaches her about “fight or flight” and explains that it is a normal physiologic response that can lead to panic. Lacey learns to approach her physical symptoms in a different way, and how to breathe in a way that slows her panic reaction.

Consider SSRIs and SNRIs

Firstline medication is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), due to the better tolerability and lower adverse effect profile of these classes compared with the tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). MAOIs are usually reserved for patients in whom multiple medication trials have failed.

Special considerations. American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise starting with a very low dose of an SSRI or SNRI, such as paroxetine 10 mg/d (although

Keep in mind that the onset of therapeutic effect is between two and four weeks, but that clinical response can take eight to 12 weeks. Continue pharmacotherapy for at least one year. When discontinuing the medication, taper it slowly, and monitor the patient for withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of PD.9

Consider adding a benzodiazepine if symptoms are debilitating.9 Keep in mind, though, that the potential for addiction with these medications is high and they are intended to be used for only four to 12 weeks.8 Onset of action is within the first week, and a scheduled dosing regimen is preferred to giving the medication as needed. The starting dose (eg, clonazepam 0.25 mg bid) may be increased three to five days following initiation.9

Evidence supports the use of CBT for PD

CBT is an evidenced-based treatment for PD.10-13 Up to 75% of patients treated with CBT are panic free within four months.10 Other techniques proven effective are progressive muscle relaxation training, breathing retraining, psychoeducation, exposure, and imagery.14

Treatment with medications and CBT, either combined or used individually, is effective in 80% to 90% of cases.15 CBT has been shown to decrease the likelihood of relapse in the year following treatment.15 Good premorbid functioning and a brief duration of symptoms increase the likelihood of a good prognosis.15

WHEN TO REFER TO A PSYCHIATRIST

Consider referral to a psychiatrist when patients have a comorbid psychiatric condition that complicates the clinical picture (eg, substance abuse disorder), if the diagnosis is uncertain, or if the patient does not respond to one or two adequate trials of medication and psychotherapy. Although psychiatric follow-up is sometimes difficult due to a lack of psychiatrist availability locally, it is a best-practice recommendation.

Ten days after Lacey starts the sertraline 25 mg/d, she calls the PCP to report daily diarrhea. She stopped the sertraline on her own and is asking for another medication. She also expresses her frustration with the severity of the symptoms. She is having three to five panic attacks daily and has been missing many days of work.

On the day of her follow-up PCP appointment, Lacey also sees the psychologist. She reports that she’s been practicing relaxation breathing, tracking her panic attacks, limiting her caffeine intake, and exercising regularly. But the attacks are still occurring.

The PCP switches her to paroxetine 10 mg/d and, due to the severity of the symptoms, prescribes clonazepam 0.5 mg bid. Two weeks later, Lacey reports that she is feeling a little better, has returned to work, and is hopeful that she will be her “normal self again.” The PCP plans to encourage continuation of CBT, titrate the paroxetine to 20 to 40 mg/d based on symptoms, and slowly taper the clonazepam toward discontinuation in the near future.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kumar S, Oakley-Browne M. Panic disorder. Clin Evid. 2006;15:1438-1452.

3. Yingling KW, Wulsin LR, Arnold LM, et al. Estimated prevalences of panic disorder and depression among consecutive patients seen in an emergency department with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:231-235.

4. Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al. Panic disorder in emergency department chest pain patients: prevalence, comorbidity, suicidal ideation, and physician recognition. Am J Med. 1996;101:371-380.

5. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749-1756.

6. Taylor CB. Panic disorder. BMJ. 2006;332:951-955.

7. de Jonge P, Roest AM, Lim CC, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder and panic attacks in the world mental health surveys. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33: 1155-1177.

8. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Panic disorder. In: Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015:392-397.

9. Stein MB, Goin MK, Pollack MH, et al. ractice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2018.

10. Westen D, Morrison K. A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:875-899.

11. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66380/. Accessed February 14, 2018.

12. Clum GA, Clum GA, Surls R. A meta-analysis of treatments for panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993; 61:317-326.

13. Shear MK, Houck P, Greeno C, et al. Emotion-focused psychotherapy for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1993-1998.

14. Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595-606.

15. Craske M. Psychotherapy for panic disorder in adults. Up to Date. 2017. www.uptodate.com/contents/psychotherapy-for-panic-disorder-with-or-without-agoraphobia-in-adults. Accessed February 14, 2018.

Lacey, 37, is seen by her primary care provider (PCP) as follow-up to a visit she made to the emergency department (ED). She has gone to the ED four times in the past year. Each time, she presents with tachycardia, dyspnea, nausea, numbness in her extremities, and a fear that she is having a heart attack. Despite negative workups at each visit (ECG, cardiac enzymes, complete blood count, toxicology screen, Holter monitoring), Lacey is terrified that the ED doctors are missing something. She is still “rattled” by the chest pain and shortness of breath she experiences. Mild symptoms are persisting, and she is worried that she will have a heart attack and die without the treatment she believes she needs. How do you proceed?

Panic disorder (PD) is characterized by the spontaneous and unexpected occurrence of panic attacks and by at least one month of persistent worry about having another attack or significant maladaptive behaviors related to the attack. Frequency of such attacks can vary from several a day to only a few per year. In a panic attack, an intense fear develops abruptly and peaks within 10 minutes of onset. At least four of the following 13 symptoms must accompany the attack, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5)

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feeling of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

- Fear of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling sensations)

- Chills or hot flushes.1

Lifetime incidence rates of PD are 1% to 3% for the general population.2 A closer look at patients presenting to the ED with chest pain reveals that 17% to 25% meet criteria for PD.3,4 And an estimated 6% of individuals experiencing a panic attack present to their primary care provider.5 Patients with PD tend to use health care resources at a disproportionately high rate.6

An international review of PD research suggests the average age of onset is 32 years.7 Triggers can vary widely, and no single stressor has been identified. The exact cause of PD is unknown, but a convergence of social and biological influences (including involvement of the amygdala) are implicated in its development.6 For individuals who have had a panic attack, 66.5% will have recurrent attacks.7 Lifetime prevalence of panic attacks is 13.2%.7

Differential goes far beyond myocardial infarction. Many medical conditions can mimic PD symptoms: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic diseases; endocrine diseases (eg, hyperthyroidism); drug intoxication (eg, stimulants [cocaine, amphetamines]); drug withdrawal (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, sedative-hypnotics); and ingestion of excessive quantities of caffeine. Common comorbid medical disorders include asthma, coronary artery disease, cancer, thyroid disease, hypertension, ulcer, and migraine headaches.8

When patients present with paniclike symptoms, suspect a possible medical condition when those symptoms include ataxia, altered mental status, or loss of bladder control, or when onset of panic symptoms occur later in life for a patient with no significant psychiatric history.

RULE OUT ORGANIC CAUSES

In addition to obtaining a complete history and doing a physical exam on patients with paniclike symptoms, you’ll also need to ensure that the following are done: a neurologic examination, standard laboratory testing (thyroid function, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel), and possible additional testing (eg, urine toxicology screen and

If organic causes are ruled out, focus on a psychiatric assessment, including

- History of the present illness (onset, symptoms, frequency, predisposing/precipitating factors)

- Psychiatric history

- History of substance use

- Family history of psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders)

- Social history (life events, including those preceding the onset of panic; history of child abuse)

- Medications

- Mental status examination

- Safety (PD is associated with higher risk for suicidal ideation).9

TREATMENT INCLUDES CBT AND MEDICATION

PD is a chronic disease with a variable course, but the long-term prognosis is good. PD is usually treated in an outpatient setting. Consider hospitalization if the patient is suicidal, if the potential for life-threatening withdrawal symptoms is high (as with alcohol or benzodiazepines), or if the symptoms are severely debilitating or attempted outpatient treatment is unsuccessful. Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions are used for PD (see Figure), although there is not enough evidence to recommend one versus the other or combination therapy versus monotherapy.9

All Lacey’s test results come back negative, and the psychiatric assessment reveals that she meets the DSM-5 criteria for PD. Counting on the strength of their relationship, her PCP talks to her about PD and discusses treatment options, which include counseling, medication, or both. Lacey agrees to a referral for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a psychologist embedded at her primary care clinic and to begin taking medication. Her PCP starts her on sertraline 25 mg/d.

In CBT, Lacey’s psychologist teaches her about “fight or flight” and explains that it is a normal physiologic response that can lead to panic. Lacey learns to approach her physical symptoms in a different way, and how to breathe in a way that slows her panic reaction.

Consider SSRIs and SNRIs

Firstline medication is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), due to the better tolerability and lower adverse effect profile of these classes compared with the tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). MAOIs are usually reserved for patients in whom multiple medication trials have failed.

Special considerations. American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise starting with a very low dose of an SSRI or SNRI, such as paroxetine 10 mg/d (although

Keep in mind that the onset of therapeutic effect is between two and four weeks, but that clinical response can take eight to 12 weeks. Continue pharmacotherapy for at least one year. When discontinuing the medication, taper it slowly, and monitor the patient for withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of PD.9

Consider adding a benzodiazepine if symptoms are debilitating.9 Keep in mind, though, that the potential for addiction with these medications is high and they are intended to be used for only four to 12 weeks.8 Onset of action is within the first week, and a scheduled dosing regimen is preferred to giving the medication as needed. The starting dose (eg, clonazepam 0.25 mg bid) may be increased three to five days following initiation.9

Evidence supports the use of CBT for PD

CBT is an evidenced-based treatment for PD.10-13 Up to 75% of patients treated with CBT are panic free within four months.10 Other techniques proven effective are progressive muscle relaxation training, breathing retraining, psychoeducation, exposure, and imagery.14

Treatment with medications and CBT, either combined or used individually, is effective in 80% to 90% of cases.15 CBT has been shown to decrease the likelihood of relapse in the year following treatment.15 Good premorbid functioning and a brief duration of symptoms increase the likelihood of a good prognosis.15

WHEN TO REFER TO A PSYCHIATRIST

Consider referral to a psychiatrist when patients have a comorbid psychiatric condition that complicates the clinical picture (eg, substance abuse disorder), if the diagnosis is uncertain, or if the patient does not respond to one or two adequate trials of medication and psychotherapy. Although psychiatric follow-up is sometimes difficult due to a lack of psychiatrist availability locally, it is a best-practice recommendation.

Ten days after Lacey starts the sertraline 25 mg/d, she calls the PCP to report daily diarrhea. She stopped the sertraline on her own and is asking for another medication. She also expresses her frustration with the severity of the symptoms. She is having three to five panic attacks daily and has been missing many days of work.

On the day of her follow-up PCP appointment, Lacey also sees the psychologist. She reports that she’s been practicing relaxation breathing, tracking her panic attacks, limiting her caffeine intake, and exercising regularly. But the attacks are still occurring.

The PCP switches her to paroxetine 10 mg/d and, due to the severity of the symptoms, prescribes clonazepam 0.5 mg bid. Two weeks later, Lacey reports that she is feeling a little better, has returned to work, and is hopeful that she will be her “normal self again.” The PCP plans to encourage continuation of CBT, titrate the paroxetine to 20 to 40 mg/d based on symptoms, and slowly taper the clonazepam toward discontinuation in the near future.

Lacey, 37, is seen by her primary care provider (PCP) as follow-up to a visit she made to the emergency department (ED). She has gone to the ED four times in the past year. Each time, she presents with tachycardia, dyspnea, nausea, numbness in her extremities, and a fear that she is having a heart attack. Despite negative workups at each visit (ECG, cardiac enzymes, complete blood count, toxicology screen, Holter monitoring), Lacey is terrified that the ED doctors are missing something. She is still “rattled” by the chest pain and shortness of breath she experiences. Mild symptoms are persisting, and she is worried that she will have a heart attack and die without the treatment she believes she needs. How do you proceed?

Panic disorder (PD) is characterized by the spontaneous and unexpected occurrence of panic attacks and by at least one month of persistent worry about having another attack or significant maladaptive behaviors related to the attack. Frequency of such attacks can vary from several a day to only a few per year. In a panic attack, an intense fear develops abruptly and peaks within 10 minutes of onset. At least four of the following 13 symptoms must accompany the attack, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5)

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feeling of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

- Fear of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling sensations)

- Chills or hot flushes.1

Lifetime incidence rates of PD are 1% to 3% for the general population.2 A closer look at patients presenting to the ED with chest pain reveals that 17% to 25% meet criteria for PD.3,4 And an estimated 6% of individuals experiencing a panic attack present to their primary care provider.5 Patients with PD tend to use health care resources at a disproportionately high rate.6

An international review of PD research suggests the average age of onset is 32 years.7 Triggers can vary widely, and no single stressor has been identified. The exact cause of PD is unknown, but a convergence of social and biological influences (including involvement of the amygdala) are implicated in its development.6 For individuals who have had a panic attack, 66.5% will have recurrent attacks.7 Lifetime prevalence of panic attacks is 13.2%.7

Differential goes far beyond myocardial infarction. Many medical conditions can mimic PD symptoms: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic diseases; endocrine diseases (eg, hyperthyroidism); drug intoxication (eg, stimulants [cocaine, amphetamines]); drug withdrawal (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, sedative-hypnotics); and ingestion of excessive quantities of caffeine. Common comorbid medical disorders include asthma, coronary artery disease, cancer, thyroid disease, hypertension, ulcer, and migraine headaches.8

When patients present with paniclike symptoms, suspect a possible medical condition when those symptoms include ataxia, altered mental status, or loss of bladder control, or when onset of panic symptoms occur later in life for a patient with no significant psychiatric history.

RULE OUT ORGANIC CAUSES

In addition to obtaining a complete history and doing a physical exam on patients with paniclike symptoms, you’ll also need to ensure that the following are done: a neurologic examination, standard laboratory testing (thyroid function, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel), and possible additional testing (eg, urine toxicology screen and

If organic causes are ruled out, focus on a psychiatric assessment, including

- History of the present illness (onset, symptoms, frequency, predisposing/precipitating factors)

- Psychiatric history

- History of substance use

- Family history of psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders)

- Social history (life events, including those preceding the onset of panic; history of child abuse)

- Medications

- Mental status examination

- Safety (PD is associated with higher risk for suicidal ideation).9

TREATMENT INCLUDES CBT AND MEDICATION

PD is a chronic disease with a variable course, but the long-term prognosis is good. PD is usually treated in an outpatient setting. Consider hospitalization if the patient is suicidal, if the potential for life-threatening withdrawal symptoms is high (as with alcohol or benzodiazepines), or if the symptoms are severely debilitating or attempted outpatient treatment is unsuccessful. Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions are used for PD (see Figure), although there is not enough evidence to recommend one versus the other or combination therapy versus monotherapy.9

All Lacey’s test results come back negative, and the psychiatric assessment reveals that she meets the DSM-5 criteria for PD. Counting on the strength of their relationship, her PCP talks to her about PD and discusses treatment options, which include counseling, medication, or both. Lacey agrees to a referral for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a psychologist embedded at her primary care clinic and to begin taking medication. Her PCP starts her on sertraline 25 mg/d.

In CBT, Lacey’s psychologist teaches her about “fight or flight” and explains that it is a normal physiologic response that can lead to panic. Lacey learns to approach her physical symptoms in a different way, and how to breathe in a way that slows her panic reaction.

Consider SSRIs and SNRIs

Firstline medication is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), due to the better tolerability and lower adverse effect profile of these classes compared with the tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). MAOIs are usually reserved for patients in whom multiple medication trials have failed.

Special considerations. American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise starting with a very low dose of an SSRI or SNRI, such as paroxetine 10 mg/d (although

Keep in mind that the onset of therapeutic effect is between two and four weeks, but that clinical response can take eight to 12 weeks. Continue pharmacotherapy for at least one year. When discontinuing the medication, taper it slowly, and monitor the patient for withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of PD.9

Consider adding a benzodiazepine if symptoms are debilitating.9 Keep in mind, though, that the potential for addiction with these medications is high and they are intended to be used for only four to 12 weeks.8 Onset of action is within the first week, and a scheduled dosing regimen is preferred to giving the medication as needed. The starting dose (eg, clonazepam 0.25 mg bid) may be increased three to five days following initiation.9

Evidence supports the use of CBT for PD

CBT is an evidenced-based treatment for PD.10-13 Up to 75% of patients treated with CBT are panic free within four months.10 Other techniques proven effective are progressive muscle relaxation training, breathing retraining, psychoeducation, exposure, and imagery.14

Treatment with medications and CBT, either combined or used individually, is effective in 80% to 90% of cases.15 CBT has been shown to decrease the likelihood of relapse in the year following treatment.15 Good premorbid functioning and a brief duration of symptoms increase the likelihood of a good prognosis.15

WHEN TO REFER TO A PSYCHIATRIST

Consider referral to a psychiatrist when patients have a comorbid psychiatric condition that complicates the clinical picture (eg, substance abuse disorder), if the diagnosis is uncertain, or if the patient does not respond to one or two adequate trials of medication and psychotherapy. Although psychiatric follow-up is sometimes difficult due to a lack of psychiatrist availability locally, it is a best-practice recommendation.

Ten days after Lacey starts the sertraline 25 mg/d, she calls the PCP to report daily diarrhea. She stopped the sertraline on her own and is asking for another medication. She also expresses her frustration with the severity of the symptoms. She is having three to five panic attacks daily and has been missing many days of work.

On the day of her follow-up PCP appointment, Lacey also sees the psychologist. She reports that she’s been practicing relaxation breathing, tracking her panic attacks, limiting her caffeine intake, and exercising regularly. But the attacks are still occurring.

The PCP switches her to paroxetine 10 mg/d and, due to the severity of the symptoms, prescribes clonazepam 0.5 mg bid. Two weeks later, Lacey reports that she is feeling a little better, has returned to work, and is hopeful that she will be her “normal self again.” The PCP plans to encourage continuation of CBT, titrate the paroxetine to 20 to 40 mg/d based on symptoms, and slowly taper the clonazepam toward discontinuation in the near future.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kumar S, Oakley-Browne M. Panic disorder. Clin Evid. 2006;15:1438-1452.

3. Yingling KW, Wulsin LR, Arnold LM, et al. Estimated prevalences of panic disorder and depression among consecutive patients seen in an emergency department with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:231-235.

4. Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al. Panic disorder in emergency department chest pain patients: prevalence, comorbidity, suicidal ideation, and physician recognition. Am J Med. 1996;101:371-380.

5. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749-1756.

6. Taylor CB. Panic disorder. BMJ. 2006;332:951-955.

7. de Jonge P, Roest AM, Lim CC, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder and panic attacks in the world mental health surveys. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33: 1155-1177.

8. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Panic disorder. In: Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015:392-397.

9. Stein MB, Goin MK, Pollack MH, et al. ractice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2018.

10. Westen D, Morrison K. A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:875-899.

11. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66380/. Accessed February 14, 2018.

12. Clum GA, Clum GA, Surls R. A meta-analysis of treatments for panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993; 61:317-326.

13. Shear MK, Houck P, Greeno C, et al. Emotion-focused psychotherapy for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1993-1998.

14. Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595-606.

15. Craske M. Psychotherapy for panic disorder in adults. Up to Date. 2017. www.uptodate.com/contents/psychotherapy-for-panic-disorder-with-or-without-agoraphobia-in-adults. Accessed February 14, 2018.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kumar S, Oakley-Browne M. Panic disorder. Clin Evid. 2006;15:1438-1452.

3. Yingling KW, Wulsin LR, Arnold LM, et al. Estimated prevalences of panic disorder and depression among consecutive patients seen in an emergency department with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:231-235.

4. Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al. Panic disorder in emergency department chest pain patients: prevalence, comorbidity, suicidal ideation, and physician recognition. Am J Med. 1996;101:371-380.

5. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749-1756.

6. Taylor CB. Panic disorder. BMJ. 2006;332:951-955.

7. de Jonge P, Roest AM, Lim CC, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder and panic attacks in the world mental health surveys. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33: 1155-1177.

8. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Panic disorder. In: Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015:392-397.

9. Stein MB, Goin MK, Pollack MH, et al. ractice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2018.

10. Westen D, Morrison K. A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:875-899.

11. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66380/. Accessed February 14, 2018.

12. Clum GA, Clum GA, Surls R. A meta-analysis of treatments for panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993; 61:317-326.

13. Shear MK, Houck P, Greeno C, et al. Emotion-focused psychotherapy for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1993-1998.

14. Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595-606.

15. Craske M. Psychotherapy for panic disorder in adults. Up to Date. 2017. www.uptodate.com/contents/psychotherapy-for-panic-disorder-with-or-without-agoraphobia-in-adults. Accessed February 14, 2018.