User login

Difficult patient, or something else? A review of personality disorders

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

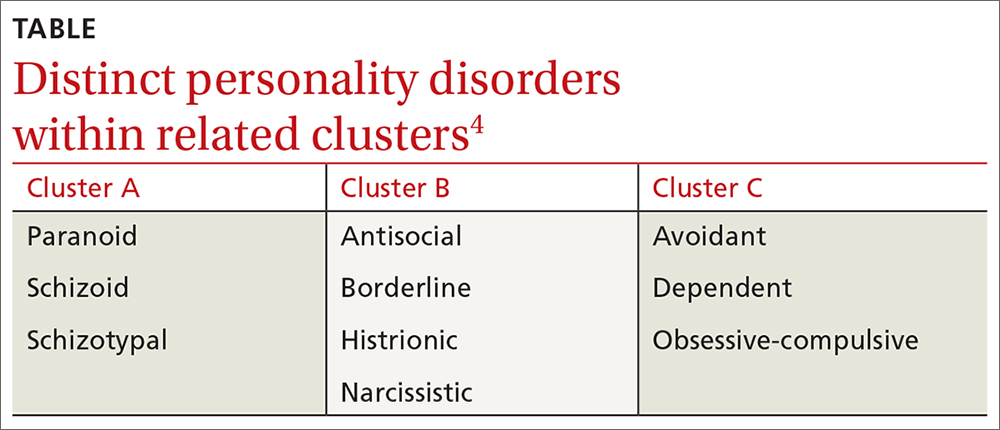

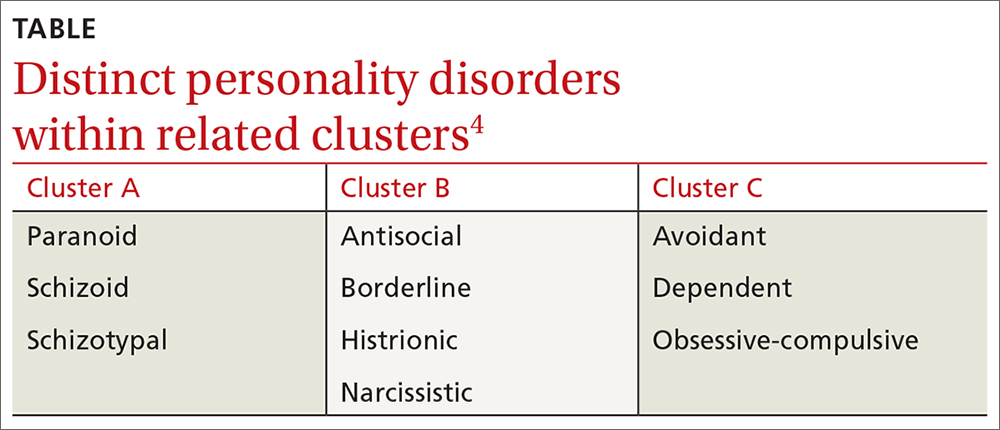

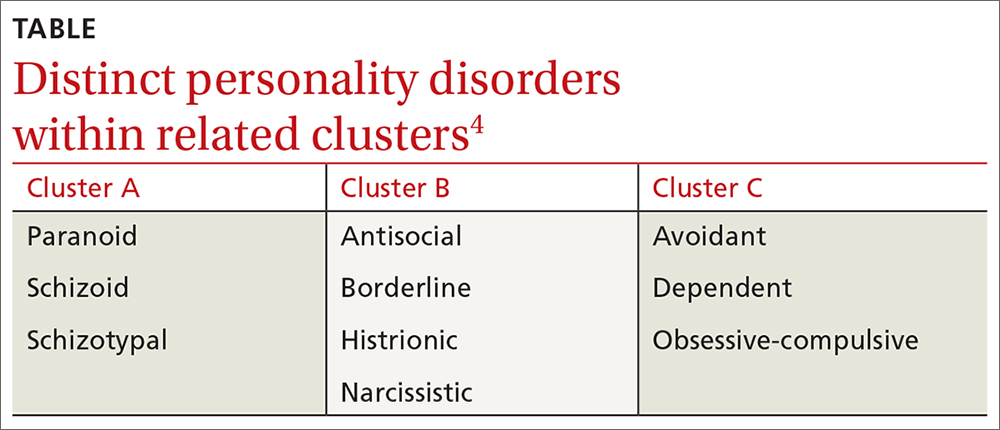

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...

A closer look at the clusters

Cluster A disorders

Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal disorders are part of this cluster. These patients exhibit odd or eccentric thinking and behavior. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder, for instance, usually lack relationships and lack the desire to acquire and maintain relationships.4 They often organize their lives to remain isolated and will choose occupations that require little social interaction. They sometimes view themselves as observers rather than participants in their own lives.6

Cluster B disorders

Dramatic, overly emotional, or unpredictable thinking and behavior are characteristic of individuals who have antisocial, borderline, histrionic, or narcissistic disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), for example, demonstrate a longstanding pattern of instability in affect, self-image, and relationships.4 Patients with BPD often display extreme interpersonal hypersensitivity and make frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and efforts to avoid abandonment have all been associated with increased suicide risk.7

In a primary care setting, such a patient may display extremely strong reactions to minor disappointments. When the physician is unavailable for a last-minute appointment or to authorize an unscheduled medication refill or to receive an after-hours phone call, the patient may become irate. The physician, who previously was idealized by the patient as “the only person who understands me,” is now devalued as “the worst doctor I’ve ever had.”8

Cluster C disorders

With these individuals, anxious or fearful thinking and behavior predominate. Avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are included in this cluster.

Dependent personality disorder (DPD) is characterized by a pervasive and extreme need to be taken care of. Submissive and clingy behavior and fear of separation are excessive. This patient may have difficulty making everyday decisions, being assertive, or expressing disagreement with others.4

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder falls in this cluster and is typified by a pervasive preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and control, at the price of flexibility and efficiency. This individual may be reluctant to get rid of sentimental objects, have rigid moral beliefs, and have significant difficulty working with others who do not follow their rules.4

Continue to: These clues may suggest...

These clues may suggest a personality disorder

If you find that encounters with a particular patient are growing increasingly difficult, consider whether the following behaviors, attitudes, and patterns of thinking are coming into play. If they are, you may want to consider using a screening tool, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

❚ Clues to cluster A disorders

- The patient has no peer relationships outside immediate family.

- The patient almost always chooses solitary activities for work and personal enjoyment.

❚ Cluster B clues

- Hypersensitivity to treatment disagreements or cancelled appointments are common (and likely experienced as rejection).

- Mood changes occur very quickly, even during a single visit.

- There is a history of many failed relationships with providers and others.

- The patient will describe an individual as both “wonderful” and “terrible” (ie, splitting) and may do so during the course of one visit.

- The patient may also split groups (eg, medical staff) by affective extremes (eg, adoration and hatred).

- The patient may hint at suicide or acts of self-harm.7

❚ Cluster C clues

- There is an excessive dependency on family, friends, or providers.

- Significant anxiety is experienced when the patient has to make an independent decision.

- There is a fear of relationship loss and resultant vulnerability to exploitation or abuse.

- Pervasive perfectionism makes treatment planning or course changes difficult.

- Anxiety and fear are unrelieved despite support and ample information.

Consider these screening tools

Several screening tools for personality disorders can be used to follow up on your initial clinical impressions. We also highly recommend you consider concurrent screening for substance abuse, as addiction is a common comorbidity with personality disorders.

❚

❚ A sampling of screening tools. The Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)9 is an 8-item measure that correlates well with disorders in clusters A and C.

BPD (cluster B) has many brief scale options, including the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).10 This 10-item questionnaire demonstrates sensitivity and specificity for BPD.

The International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) includes a 15-minute screening tool to help identify patients who may have any personality disorder, regardless of cluster.11

Improve patient encounters with these Tx pearls

In the family medicine clinic, a collaborative primary care and behavioral health team can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis and management of patients with personality disorders.12 First-line treatment of these disorders is psychotherapy, whereas medications are mainly used for symptom management. See Black and colleagues’ work for a thorough discussion on psychopharmacology considerations with personality disorders. 13

The following tips can help you to improve your interactions with patients who have personality disorders.

❚ Cluster A approaches

- Recommend treatment that respects the patient’s need for relative isolation.14

- Don’t be personally offended by your patient’s flat or disinterested affect or concrete thinking; don’t let it diminish the emotional support you provide.6

- Consult with a health psychologist (who has expertise in physical health conditions, brief treatments, and the medical system) to connect the patient with a long-term therapist. It is better to focus on fundamental changes, rather than employing brief behavioral techniques, for symptom relief. Patients with personality disorders tend to have better outcomes with long-term psychological care.15

❚ Cluster B approaches

- Set boundaries—eg, specific time limits for visits—and keep them.8

- Schedule brief, more frequent, appointments to reduce perceived feelings of abandonment.

- Coordinate plans with the entire clinic team to avoid splitting and blaming.16

- Avoid providing patients with personal information, as it may provide fodder for splitting behavior. 8

- Do not take things personally. Let patients “own” their own distress. These patients often take an emotional toll on the provider.16

- Engage the help of a health psychologist to reduce burnout and for more long-term continuity of care. A health psychologist who specializes in dialectical behavioral therapy to work on emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness would be ideal.17

Continue to: Cluster C approaches...

❚

❚ Cluster C approaches

- Engage the help of family and other trusted individuals in supporting treatment plans.18,19

- Try to provide just 2 treatment choices to the patient and reinforce his or her responsibility to help make the decision collaboratively. This step is important since it is difficult to enhance autonomy in these patients.20

- Engage the help of a cognitive behavioral therapist who can work on assertiveness and problem-solving skills.19

- Be empathetic with the patient and patiently build a trusting relationship, rather than “arguing” with the patient about each specific worry.20

- Make only one change at a time. Give small assignments to the patient, such as monitoring symptoms or reading up on their condition. These can help the patient feel more in control.21

- Present information in brief, clear terms. Avoid “grey areas” to reduce anxiety.21

- Engage a behavioral health provider to reduce rigid expectations and ideally increase feelings of self-esteem; this has been shown to predict better treatment outcomes.22

CASES

Mr. S displays cluster-A characteristics of schizoid personality disorder in addition to the depression he is being treated for. His physician was not put off by his flat affect and respected his limitations with social activities. Use of a stationary bike was recommended for exercise rather than walks outdoors. He also preferred phone calls to in-person encounters, so his follow-up visits were conducted by phone.

Ms. L exhibits cluster-B characteristics of BPD. You begin the tricky dance of setting limits, keeping communication clear, and not blaming yourself or others on your team for Ms. L’s feelings. You schedule regular visits with explicit time limits and discuss with your entire team how to avoid splitting. You involve a psychologist, familiar with treating BPD, who helps the patient learn positive interpersonal coping skills.

Ms. B displays cluster-C characteristics of dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. At her follow-up visit, you provide a great deal of empathy and try not to argue her out of each worry that she brings up. You make one change at a time and enlist the help of her daughter in giving her pills at home and offering reassurance. You collaborate with a cognitive behavioral therapist who works on exposing her to moderately anxiety-provoking situations/decisions.

1. Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:30-34.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med.1978;298: 883-887.

3. O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in primary care. BMJ. 1988;297:528-530.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

5. Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709-715.

6. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515-528.

7. Yen S, Peters JR, Nishar S, et al. Association of borderline personality disorder criteria with suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal study of personality disorders over 10 years of follow-up. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:187-194.

8. Dubovsky AN, Kiefer MM. Borderline personality disorder in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1049-1064.

9. Hesse M, Moran P. (2010). Screening for personality disorder with the Standardised Assessment of Personality: Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): further evidence of concurrent validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:10.

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17:568-573.

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:215-224.12. Nelson KJ, Skodol A, Friedman M. Pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. UpToDate. Accessed April 22, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-personality-disorders

13. Black D, Paris J, Schulz C. Evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M (ed). Cognitive Behavioral Psychopharmacology: the Clinical Practice of Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Integration. Wiley; 2017:137-166.

14. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; 2015.

15. Thylstrup B, Hesse M. “I am not complaining”–ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63:147-167.

16. Ricke AK, Lee MJ, Chambers JE. The difficult patient: borderline personality disorder in the obstetrical and gynecological patient. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:495-502.

17. Seow LLY, Page AC, Hooke GR. Severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms as a moderator of the association between the use of dialectical behaviour therapy skills and treatment outcomes. Psychother Res. 2020;30:920-933.

18. Nichols WC. Integrative marital and family treatment of dependent personality disorders. In: MacFarlane MM (Ed.) Family Treatment of Personality Disorders: Advances in Clinical Practice. Haworth Clinical Practice Press; 2004:173-204.

19. Disney KL. Dependent personality disorder: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1184-1196.

20. Bender DS. The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:73-87.

21. Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1505-1512.

22. Cummings JA, Hayes AM, Cardaciotto L, et al. The dynamics of self-esteem in cognitive therapy for avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: an adaptive role of self-esteem variability? Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:272-281.

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...

A closer look at the clusters

Cluster A disorders

Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal disorders are part of this cluster. These patients exhibit odd or eccentric thinking and behavior. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder, for instance, usually lack relationships and lack the desire to acquire and maintain relationships.4 They often organize their lives to remain isolated and will choose occupations that require little social interaction. They sometimes view themselves as observers rather than participants in their own lives.6

Cluster B disorders

Dramatic, overly emotional, or unpredictable thinking and behavior are characteristic of individuals who have antisocial, borderline, histrionic, or narcissistic disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), for example, demonstrate a longstanding pattern of instability in affect, self-image, and relationships.4 Patients with BPD often display extreme interpersonal hypersensitivity and make frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and efforts to avoid abandonment have all been associated with increased suicide risk.7

In a primary care setting, such a patient may display extremely strong reactions to minor disappointments. When the physician is unavailable for a last-minute appointment or to authorize an unscheduled medication refill or to receive an after-hours phone call, the patient may become irate. The physician, who previously was idealized by the patient as “the only person who understands me,” is now devalued as “the worst doctor I’ve ever had.”8

Cluster C disorders

With these individuals, anxious or fearful thinking and behavior predominate. Avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are included in this cluster.

Dependent personality disorder (DPD) is characterized by a pervasive and extreme need to be taken care of. Submissive and clingy behavior and fear of separation are excessive. This patient may have difficulty making everyday decisions, being assertive, or expressing disagreement with others.4

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder falls in this cluster and is typified by a pervasive preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and control, at the price of flexibility and efficiency. This individual may be reluctant to get rid of sentimental objects, have rigid moral beliefs, and have significant difficulty working with others who do not follow their rules.4

Continue to: These clues may suggest...

These clues may suggest a personality disorder

If you find that encounters with a particular patient are growing increasingly difficult, consider whether the following behaviors, attitudes, and patterns of thinking are coming into play. If they are, you may want to consider using a screening tool, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

❚ Clues to cluster A disorders

- The patient has no peer relationships outside immediate family.

- The patient almost always chooses solitary activities for work and personal enjoyment.

❚ Cluster B clues

- Hypersensitivity to treatment disagreements or cancelled appointments are common (and likely experienced as rejection).

- Mood changes occur very quickly, even during a single visit.

- There is a history of many failed relationships with providers and others.

- The patient will describe an individual as both “wonderful” and “terrible” (ie, splitting) and may do so during the course of one visit.

- The patient may also split groups (eg, medical staff) by affective extremes (eg, adoration and hatred).

- The patient may hint at suicide or acts of self-harm.7

❚ Cluster C clues

- There is an excessive dependency on family, friends, or providers.

- Significant anxiety is experienced when the patient has to make an independent decision.

- There is a fear of relationship loss and resultant vulnerability to exploitation or abuse.

- Pervasive perfectionism makes treatment planning or course changes difficult.

- Anxiety and fear are unrelieved despite support and ample information.

Consider these screening tools

Several screening tools for personality disorders can be used to follow up on your initial clinical impressions. We also highly recommend you consider concurrent screening for substance abuse, as addiction is a common comorbidity with personality disorders.

❚

❚ A sampling of screening tools. The Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)9 is an 8-item measure that correlates well with disorders in clusters A and C.

BPD (cluster B) has many brief scale options, including the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).10 This 10-item questionnaire demonstrates sensitivity and specificity for BPD.

The International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) includes a 15-minute screening tool to help identify patients who may have any personality disorder, regardless of cluster.11

Improve patient encounters with these Tx pearls

In the family medicine clinic, a collaborative primary care and behavioral health team can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis and management of patients with personality disorders.12 First-line treatment of these disorders is psychotherapy, whereas medications are mainly used for symptom management. See Black and colleagues’ work for a thorough discussion on psychopharmacology considerations with personality disorders. 13

The following tips can help you to improve your interactions with patients who have personality disorders.

❚ Cluster A approaches

- Recommend treatment that respects the patient’s need for relative isolation.14

- Don’t be personally offended by your patient’s flat or disinterested affect or concrete thinking; don’t let it diminish the emotional support you provide.6

- Consult with a health psychologist (who has expertise in physical health conditions, brief treatments, and the medical system) to connect the patient with a long-term therapist. It is better to focus on fundamental changes, rather than employing brief behavioral techniques, for symptom relief. Patients with personality disorders tend to have better outcomes with long-term psychological care.15

❚ Cluster B approaches

- Set boundaries—eg, specific time limits for visits—and keep them.8

- Schedule brief, more frequent, appointments to reduce perceived feelings of abandonment.

- Coordinate plans with the entire clinic team to avoid splitting and blaming.16

- Avoid providing patients with personal information, as it may provide fodder for splitting behavior. 8

- Do not take things personally. Let patients “own” their own distress. These patients often take an emotional toll on the provider.16

- Engage the help of a health psychologist to reduce burnout and for more long-term continuity of care. A health psychologist who specializes in dialectical behavioral therapy to work on emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness would be ideal.17

Continue to: Cluster C approaches...

❚

❚ Cluster C approaches

- Engage the help of family and other trusted individuals in supporting treatment plans.18,19

- Try to provide just 2 treatment choices to the patient and reinforce his or her responsibility to help make the decision collaboratively. This step is important since it is difficult to enhance autonomy in these patients.20

- Engage the help of a cognitive behavioral therapist who can work on assertiveness and problem-solving skills.19

- Be empathetic with the patient and patiently build a trusting relationship, rather than “arguing” with the patient about each specific worry.20

- Make only one change at a time. Give small assignments to the patient, such as monitoring symptoms or reading up on their condition. These can help the patient feel more in control.21

- Present information in brief, clear terms. Avoid “grey areas” to reduce anxiety.21

- Engage a behavioral health provider to reduce rigid expectations and ideally increase feelings of self-esteem; this has been shown to predict better treatment outcomes.22

CASES

Mr. S displays cluster-A characteristics of schizoid personality disorder in addition to the depression he is being treated for. His physician was not put off by his flat affect and respected his limitations with social activities. Use of a stationary bike was recommended for exercise rather than walks outdoors. He also preferred phone calls to in-person encounters, so his follow-up visits were conducted by phone.

Ms. L exhibits cluster-B characteristics of BPD. You begin the tricky dance of setting limits, keeping communication clear, and not blaming yourself or others on your team for Ms. L’s feelings. You schedule regular visits with explicit time limits and discuss with your entire team how to avoid splitting. You involve a psychologist, familiar with treating BPD, who helps the patient learn positive interpersonal coping skills.

Ms. B displays cluster-C characteristics of dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. At her follow-up visit, you provide a great deal of empathy and try not to argue her out of each worry that she brings up. You make one change at a time and enlist the help of her daughter in giving her pills at home and offering reassurance. You collaborate with a cognitive behavioral therapist who works on exposing her to moderately anxiety-provoking situations/decisions.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...

A closer look at the clusters

Cluster A disorders

Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal disorders are part of this cluster. These patients exhibit odd or eccentric thinking and behavior. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder, for instance, usually lack relationships and lack the desire to acquire and maintain relationships.4 They often organize their lives to remain isolated and will choose occupations that require little social interaction. They sometimes view themselves as observers rather than participants in their own lives.6

Cluster B disorders

Dramatic, overly emotional, or unpredictable thinking and behavior are characteristic of individuals who have antisocial, borderline, histrionic, or narcissistic disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), for example, demonstrate a longstanding pattern of instability in affect, self-image, and relationships.4 Patients with BPD often display extreme interpersonal hypersensitivity and make frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and efforts to avoid abandonment have all been associated with increased suicide risk.7

In a primary care setting, such a patient may display extremely strong reactions to minor disappointments. When the physician is unavailable for a last-minute appointment or to authorize an unscheduled medication refill or to receive an after-hours phone call, the patient may become irate. The physician, who previously was idealized by the patient as “the only person who understands me,” is now devalued as “the worst doctor I’ve ever had.”8

Cluster C disorders

With these individuals, anxious or fearful thinking and behavior predominate. Avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are included in this cluster.

Dependent personality disorder (DPD) is characterized by a pervasive and extreme need to be taken care of. Submissive and clingy behavior and fear of separation are excessive. This patient may have difficulty making everyday decisions, being assertive, or expressing disagreement with others.4

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder falls in this cluster and is typified by a pervasive preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and control, at the price of flexibility and efficiency. This individual may be reluctant to get rid of sentimental objects, have rigid moral beliefs, and have significant difficulty working with others who do not follow their rules.4

Continue to: These clues may suggest...

These clues may suggest a personality disorder

If you find that encounters with a particular patient are growing increasingly difficult, consider whether the following behaviors, attitudes, and patterns of thinking are coming into play. If they are, you may want to consider using a screening tool, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

❚ Clues to cluster A disorders

- The patient has no peer relationships outside immediate family.

- The patient almost always chooses solitary activities for work and personal enjoyment.

❚ Cluster B clues

- Hypersensitivity to treatment disagreements or cancelled appointments are common (and likely experienced as rejection).

- Mood changes occur very quickly, even during a single visit.

- There is a history of many failed relationships with providers and others.

- The patient will describe an individual as both “wonderful” and “terrible” (ie, splitting) and may do so during the course of one visit.

- The patient may also split groups (eg, medical staff) by affective extremes (eg, adoration and hatred).

- The patient may hint at suicide or acts of self-harm.7

❚ Cluster C clues

- There is an excessive dependency on family, friends, or providers.

- Significant anxiety is experienced when the patient has to make an independent decision.

- There is a fear of relationship loss and resultant vulnerability to exploitation or abuse.

- Pervasive perfectionism makes treatment planning or course changes difficult.

- Anxiety and fear are unrelieved despite support and ample information.

Consider these screening tools

Several screening tools for personality disorders can be used to follow up on your initial clinical impressions. We also highly recommend you consider concurrent screening for substance abuse, as addiction is a common comorbidity with personality disorders.

❚

❚ A sampling of screening tools. The Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)9 is an 8-item measure that correlates well with disorders in clusters A and C.

BPD (cluster B) has many brief scale options, including the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).10 This 10-item questionnaire demonstrates sensitivity and specificity for BPD.

The International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) includes a 15-minute screening tool to help identify patients who may have any personality disorder, regardless of cluster.11

Improve patient encounters with these Tx pearls

In the family medicine clinic, a collaborative primary care and behavioral health team can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis and management of patients with personality disorders.12 First-line treatment of these disorders is psychotherapy, whereas medications are mainly used for symptom management. See Black and colleagues’ work for a thorough discussion on psychopharmacology considerations with personality disorders. 13

The following tips can help you to improve your interactions with patients who have personality disorders.

❚ Cluster A approaches

- Recommend treatment that respects the patient’s need for relative isolation.14

- Don’t be personally offended by your patient’s flat or disinterested affect or concrete thinking; don’t let it diminish the emotional support you provide.6

- Consult with a health psychologist (who has expertise in physical health conditions, brief treatments, and the medical system) to connect the patient with a long-term therapist. It is better to focus on fundamental changes, rather than employing brief behavioral techniques, for symptom relief. Patients with personality disorders tend to have better outcomes with long-term psychological care.15

❚ Cluster B approaches

- Set boundaries—eg, specific time limits for visits—and keep them.8

- Schedule brief, more frequent, appointments to reduce perceived feelings of abandonment.

- Coordinate plans with the entire clinic team to avoid splitting and blaming.16

- Avoid providing patients with personal information, as it may provide fodder for splitting behavior. 8

- Do not take things personally. Let patients “own” their own distress. These patients often take an emotional toll on the provider.16

- Engage the help of a health psychologist to reduce burnout and for more long-term continuity of care. A health psychologist who specializes in dialectical behavioral therapy to work on emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness would be ideal.17

Continue to: Cluster C approaches...

❚

❚ Cluster C approaches

- Engage the help of family and other trusted individuals in supporting treatment plans.18,19

- Try to provide just 2 treatment choices to the patient and reinforce his or her responsibility to help make the decision collaboratively. This step is important since it is difficult to enhance autonomy in these patients.20

- Engage the help of a cognitive behavioral therapist who can work on assertiveness and problem-solving skills.19

- Be empathetic with the patient and patiently build a trusting relationship, rather than “arguing” with the patient about each specific worry.20

- Make only one change at a time. Give small assignments to the patient, such as monitoring symptoms or reading up on their condition. These can help the patient feel more in control.21

- Present information in brief, clear terms. Avoid “grey areas” to reduce anxiety.21

- Engage a behavioral health provider to reduce rigid expectations and ideally increase feelings of self-esteem; this has been shown to predict better treatment outcomes.22

CASES

Mr. S displays cluster-A characteristics of schizoid personality disorder in addition to the depression he is being treated for. His physician was not put off by his flat affect and respected his limitations with social activities. Use of a stationary bike was recommended for exercise rather than walks outdoors. He also preferred phone calls to in-person encounters, so his follow-up visits were conducted by phone.

Ms. L exhibits cluster-B characteristics of BPD. You begin the tricky dance of setting limits, keeping communication clear, and not blaming yourself or others on your team for Ms. L’s feelings. You schedule regular visits with explicit time limits and discuss with your entire team how to avoid splitting. You involve a psychologist, familiar with treating BPD, who helps the patient learn positive interpersonal coping skills.

Ms. B displays cluster-C characteristics of dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. At her follow-up visit, you provide a great deal of empathy and try not to argue her out of each worry that she brings up. You make one change at a time and enlist the help of her daughter in giving her pills at home and offering reassurance. You collaborate with a cognitive behavioral therapist who works on exposing her to moderately anxiety-provoking situations/decisions.

1. Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:30-34.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med.1978;298: 883-887.

3. O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in primary care. BMJ. 1988;297:528-530.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

5. Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709-715.

6. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515-528.

7. Yen S, Peters JR, Nishar S, et al. Association of borderline personality disorder criteria with suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal study of personality disorders over 10 years of follow-up. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:187-194.

8. Dubovsky AN, Kiefer MM. Borderline personality disorder in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1049-1064.

9. Hesse M, Moran P. (2010). Screening for personality disorder with the Standardised Assessment of Personality: Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): further evidence of concurrent validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:10.

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17:568-573.

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:215-224.12. Nelson KJ, Skodol A, Friedman M. Pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. UpToDate. Accessed April 22, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-personality-disorders

13. Black D, Paris J, Schulz C. Evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M (ed). Cognitive Behavioral Psychopharmacology: the Clinical Practice of Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Integration. Wiley; 2017:137-166.

14. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; 2015.

15. Thylstrup B, Hesse M. “I am not complaining”–ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63:147-167.

16. Ricke AK, Lee MJ, Chambers JE. The difficult patient: borderline personality disorder in the obstetrical and gynecological patient. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:495-502.

17. Seow LLY, Page AC, Hooke GR. Severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms as a moderator of the association between the use of dialectical behaviour therapy skills and treatment outcomes. Psychother Res. 2020;30:920-933.

18. Nichols WC. Integrative marital and family treatment of dependent personality disorders. In: MacFarlane MM (Ed.) Family Treatment of Personality Disorders: Advances in Clinical Practice. Haworth Clinical Practice Press; 2004:173-204.

19. Disney KL. Dependent personality disorder: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1184-1196.

20. Bender DS. The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:73-87.

21. Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1505-1512.

22. Cummings JA, Hayes AM, Cardaciotto L, et al. The dynamics of self-esteem in cognitive therapy for avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: an adaptive role of self-esteem variability? Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:272-281.

1. Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:30-34.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med.1978;298: 883-887.

3. O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in primary care. BMJ. 1988;297:528-530.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

5. Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709-715.

6. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515-528.

7. Yen S, Peters JR, Nishar S, et al. Association of borderline personality disorder criteria with suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal study of personality disorders over 10 years of follow-up. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:187-194.

8. Dubovsky AN, Kiefer MM. Borderline personality disorder in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1049-1064.

9. Hesse M, Moran P. (2010). Screening for personality disorder with the Standardised Assessment of Personality: Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): further evidence of concurrent validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:10.

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17:568-573.

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:215-224.12. Nelson KJ, Skodol A, Friedman M. Pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. UpToDate. Accessed April 22, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-personality-disorders

13. Black D, Paris J, Schulz C. Evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M (ed). Cognitive Behavioral Psychopharmacology: the Clinical Practice of Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Integration. Wiley; 2017:137-166.

14. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; 2015.

15. Thylstrup B, Hesse M. “I am not complaining”–ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63:147-167.

16. Ricke AK, Lee MJ, Chambers JE. The difficult patient: borderline personality disorder in the obstetrical and gynecological patient. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:495-502.

17. Seow LLY, Page AC, Hooke GR. Severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms as a moderator of the association between the use of dialectical behaviour therapy skills and treatment outcomes. Psychother Res. 2020;30:920-933.

18. Nichols WC. Integrative marital and family treatment of dependent personality disorders. In: MacFarlane MM (Ed.) Family Treatment of Personality Disorders: Advances in Clinical Practice. Haworth Clinical Practice Press; 2004:173-204.

19. Disney KL. Dependent personality disorder: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1184-1196.

20. Bender DS. The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:73-87.

21. Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1505-1512.

22. Cummings JA, Hayes AM, Cardaciotto L, et al. The dynamics of self-esteem in cognitive therapy for avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: an adaptive role of self-esteem variability? Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:272-281.

Panic Disorder: Ensuring Prompt Recognition and Treatment

Lacey, 37, is seen by her primary care provider (PCP) as follow-up to a visit she made to the emergency department (ED). She has gone to the ED four times in the past year. Each time, she presents with tachycardia, dyspnea, nausea, numbness in her extremities, and a fear that she is having a heart attack. Despite negative workups at each visit (ECG, cardiac enzymes, complete blood count, toxicology screen, Holter monitoring), Lacey is terrified that the ED doctors are missing something. She is still “rattled” by the chest pain and shortness of breath she experiences. Mild symptoms are persisting, and she is worried that she will have a heart attack and die without the treatment she believes she needs. How do you proceed?

Panic disorder (PD) is characterized by the spontaneous and unexpected occurrence of panic attacks and by at least one month of persistent worry about having another attack or significant maladaptive behaviors related to the attack. Frequency of such attacks can vary from several a day to only a few per year. In a panic attack, an intense fear develops abruptly and peaks within 10 minutes of onset. At least four of the following 13 symptoms must accompany the attack, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5)

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feeling of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

- Fear of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling sensations)

- Chills or hot flushes.1

Lifetime incidence rates of PD are 1% to 3% for the general population.2 A closer look at patients presenting to the ED with chest pain reveals that 17% to 25% meet criteria for PD.3,4 And an estimated 6% of individuals experiencing a panic attack present to their primary care provider.5 Patients with PD tend to use health care resources at a disproportionately high rate.6

An international review of PD research suggests the average age of onset is 32 years.7 Triggers can vary widely, and no single stressor has been identified. The exact cause of PD is unknown, but a convergence of social and biological influences (including involvement of the amygdala) are implicated in its development.6 For individuals who have had a panic attack, 66.5% will have recurrent attacks.7 Lifetime prevalence of panic attacks is 13.2%.7

Differential goes far beyond myocardial infarction. Many medical conditions can mimic PD symptoms: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic diseases; endocrine diseases (eg, hyperthyroidism); drug intoxication (eg, stimulants [cocaine, amphetamines]); drug withdrawal (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, sedative-hypnotics); and ingestion of excessive quantities of caffeine. Common comorbid medical disorders include asthma, coronary artery disease, cancer, thyroid disease, hypertension, ulcer, and migraine headaches.8

When patients present with paniclike symptoms, suspect a possible medical condition when those symptoms include ataxia, altered mental status, or loss of bladder control, or when onset of panic symptoms occur later in life for a patient with no significant psychiatric history.

RULE OUT ORGANIC CAUSES

In addition to obtaining a complete history and doing a physical exam on patients with paniclike symptoms, you’ll also need to ensure that the following are done: a neurologic examination, standard laboratory testing (thyroid function, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel), and possible additional testing (eg, urine toxicology screen and

If organic causes are ruled out, focus on a psychiatric assessment, including

- History of the present illness (onset, symptoms, frequency, predisposing/precipitating factors)

- Psychiatric history

- History of substance use

- Family history of psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders)

- Social history (life events, including those preceding the onset of panic; history of child abuse)

- Medications

- Mental status examination

- Safety (PD is associated with higher risk for suicidal ideation).9

TREATMENT INCLUDES CBT AND MEDICATION

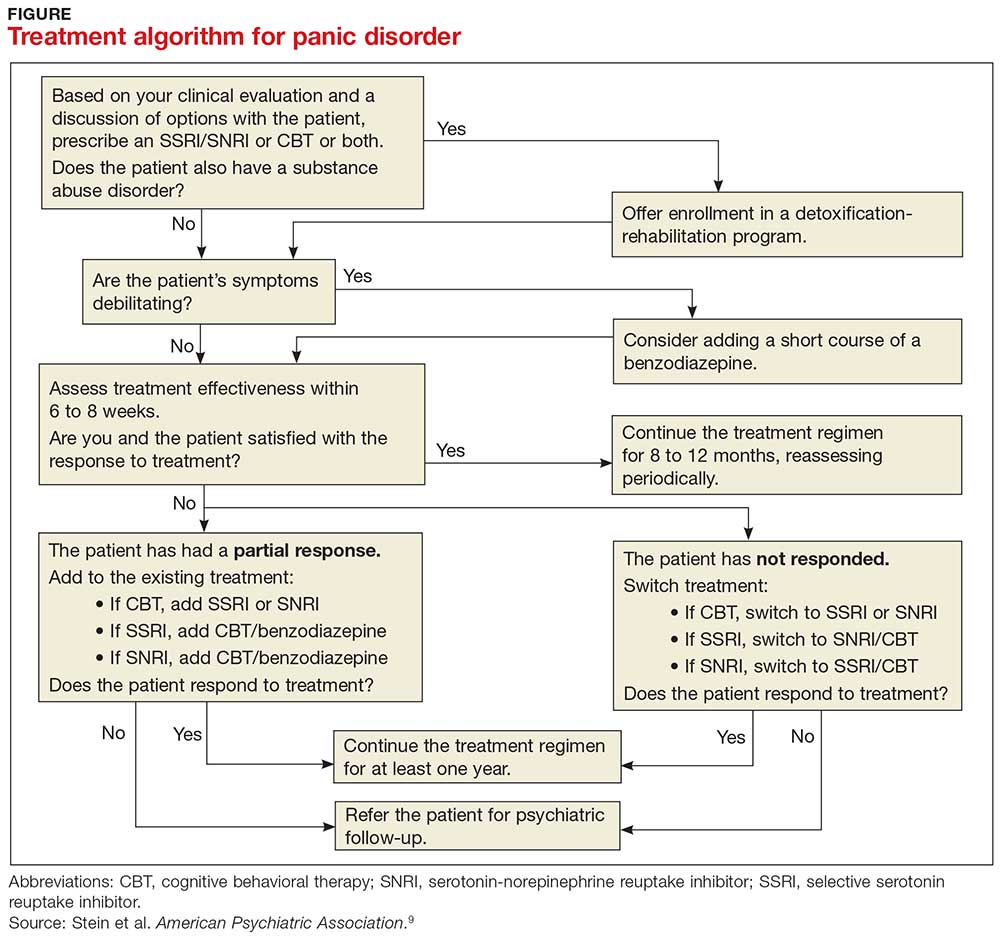

PD is a chronic disease with a variable course, but the long-term prognosis is good. PD is usually treated in an outpatient setting. Consider hospitalization if the patient is suicidal, if the potential for life-threatening withdrawal symptoms is high (as with alcohol or benzodiazepines), or if the symptoms are severely debilitating or attempted outpatient treatment is unsuccessful. Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions are used for PD (see Figure), although there is not enough evidence to recommend one versus the other or combination therapy versus monotherapy.9

All Lacey’s test results come back negative, and the psychiatric assessment reveals that she meets the DSM-5 criteria for PD. Counting on the strength of their relationship, her PCP talks to her about PD and discusses treatment options, which include counseling, medication, or both. Lacey agrees to a referral for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a psychologist embedded at her primary care clinic and to begin taking medication. Her PCP starts her on sertraline 25 mg/d.

In CBT, Lacey’s psychologist teaches her about “fight or flight” and explains that it is a normal physiologic response that can lead to panic. Lacey learns to approach her physical symptoms in a different way, and how to breathe in a way that slows her panic reaction.

Consider SSRIs and SNRIs

Firstline medication is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), due to the better tolerability and lower adverse effect profile of these classes compared with the tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). MAOIs are usually reserved for patients in whom multiple medication trials have failed.

Special considerations. American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise starting with a very low dose of an SSRI or SNRI, such as paroxetine 10 mg/d (although

Keep in mind that the onset of therapeutic effect is between two and four weeks, but that clinical response can take eight to 12 weeks. Continue pharmacotherapy for at least one year. When discontinuing the medication, taper it slowly, and monitor the patient for withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of PD.9

Consider adding a benzodiazepine if symptoms are debilitating.9 Keep in mind, though, that the potential for addiction with these medications is high and they are intended to be used for only four to 12 weeks.8 Onset of action is within the first week, and a scheduled dosing regimen is preferred to giving the medication as needed. The starting dose (eg, clonazepam 0.25 mg bid) may be increased three to five days following initiation.9

Evidence supports the use of CBT for PD

CBT is an evidenced-based treatment for PD.10-13 Up to 75% of patients treated with CBT are panic free within four months.10 Other techniques proven effective are progressive muscle relaxation training, breathing retraining, psychoeducation, exposure, and imagery.14

Treatment with medications and CBT, either combined or used individually, is effective in 80% to 90% of cases.15 CBT has been shown to decrease the likelihood of relapse in the year following treatment.15 Good premorbid functioning and a brief duration of symptoms increase the likelihood of a good prognosis.15

WHEN TO REFER TO A PSYCHIATRIST

Consider referral to a psychiatrist when patients have a comorbid psychiatric condition that complicates the clinical picture (eg, substance abuse disorder), if the diagnosis is uncertain, or if the patient does not respond to one or two adequate trials of medication and psychotherapy. Although psychiatric follow-up is sometimes difficult due to a lack of psychiatrist availability locally, it is a best-practice recommendation.

Ten days after Lacey starts the sertraline 25 mg/d, she calls the PCP to report daily diarrhea. She stopped the sertraline on her own and is asking for another medication. She also expresses her frustration with the severity of the symptoms. She is having three to five panic attacks daily and has been missing many days of work.

On the day of her follow-up PCP appointment, Lacey also sees the psychologist. She reports that she’s been practicing relaxation breathing, tracking her panic attacks, limiting her caffeine intake, and exercising regularly. But the attacks are still occurring.

The PCP switches her to paroxetine 10 mg/d and, due to the severity of the symptoms, prescribes clonazepam 0.5 mg bid. Two weeks later, Lacey reports that she is feeling a little better, has returned to work, and is hopeful that she will be her “normal self again.” The PCP plans to encourage continuation of CBT, titrate the paroxetine to 20 to 40 mg/d based on symptoms, and slowly taper the clonazepam toward discontinuation in the near future.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kumar S, Oakley-Browne M. Panic disorder. Clin Evid. 2006;15:1438-1452.

3. Yingling KW, Wulsin LR, Arnold LM, et al. Estimated prevalences of panic disorder and depression among consecutive patients seen in an emergency department with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:231-235.

4. Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al. Panic disorder in emergency department chest pain patients: prevalence, comorbidity, suicidal ideation, and physician recognition. Am J Med. 1996;101:371-380.

5. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749-1756.

6. Taylor CB. Panic disorder. BMJ. 2006;332:951-955.

7. de Jonge P, Roest AM, Lim CC, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder and panic attacks in the world mental health surveys. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33: 1155-1177.

8. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Panic disorder. In: Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015:392-397.

9. Stein MB, Goin MK, Pollack MH, et al. ractice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2018.

10. Westen D, Morrison K. A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:875-899.

11. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66380/. Accessed February 14, 2018.

12. Clum GA, Clum GA, Surls R. A meta-analysis of treatments for panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993; 61:317-326.

13. Shear MK, Houck P, Greeno C, et al. Emotion-focused psychotherapy for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1993-1998.

14. Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595-606.

15. Craske M. Psychotherapy for panic disorder in adults. Up to Date. 2017. www.uptodate.com/contents/psychotherapy-for-panic-disorder-with-or-without-agoraphobia-in-adults. Accessed February 14, 2018.

Lacey, 37, is seen by her primary care provider (PCP) as follow-up to a visit she made to the emergency department (ED). She has gone to the ED four times in the past year. Each time, she presents with tachycardia, dyspnea, nausea, numbness in her extremities, and a fear that she is having a heart attack. Despite negative workups at each visit (ECG, cardiac enzymes, complete blood count, toxicology screen, Holter monitoring), Lacey is terrified that the ED doctors are missing something. She is still “rattled” by the chest pain and shortness of breath she experiences. Mild symptoms are persisting, and she is worried that she will have a heart attack and die without the treatment she believes she needs. How do you proceed?

Panic disorder (PD) is characterized by the spontaneous and unexpected occurrence of panic attacks and by at least one month of persistent worry about having another attack or significant maladaptive behaviors related to the attack. Frequency of such attacks can vary from several a day to only a few per year. In a panic attack, an intense fear develops abruptly and peaks within 10 minutes of onset. At least four of the following 13 symptoms must accompany the attack, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5)

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feeling of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

- Fear of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling sensations)

- Chills or hot flushes.1

Lifetime incidence rates of PD are 1% to 3% for the general population.2 A closer look at patients presenting to the ED with chest pain reveals that 17% to 25% meet criteria for PD.3,4 And an estimated 6% of individuals experiencing a panic attack present to their primary care provider.5 Patients with PD tend to use health care resources at a disproportionately high rate.6

An international review of PD research suggests the average age of onset is 32 years.7 Triggers can vary widely, and no single stressor has been identified. The exact cause of PD is unknown, but a convergence of social and biological influences (including involvement of the amygdala) are implicated in its development.6 For individuals who have had a panic attack, 66.5% will have recurrent attacks.7 Lifetime prevalence of panic attacks is 13.2%.7

Differential goes far beyond myocardial infarction. Many medical conditions can mimic PD symptoms: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic diseases; endocrine diseases (eg, hyperthyroidism); drug intoxication (eg, stimulants [cocaine, amphetamines]); drug withdrawal (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, sedative-hypnotics); and ingestion of excessive quantities of caffeine. Common comorbid medical disorders include asthma, coronary artery disease, cancer, thyroid disease, hypertension, ulcer, and migraine headaches.8

When patients present with paniclike symptoms, suspect a possible medical condition when those symptoms include ataxia, altered mental status, or loss of bladder control, or when onset of panic symptoms occur later in life for a patient with no significant psychiatric history.

RULE OUT ORGANIC CAUSES

In addition to obtaining a complete history and doing a physical exam on patients with paniclike symptoms, you’ll also need to ensure that the following are done: a neurologic examination, standard laboratory testing (thyroid function, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel), and possible additional testing (eg, urine toxicology screen and

If organic causes are ruled out, focus on a psychiatric assessment, including

- History of the present illness (onset, symptoms, frequency, predisposing/precipitating factors)

- Psychiatric history

- History of substance use

- Family history of psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders)

- Social history (life events, including those preceding the onset of panic; history of child abuse)

- Medications

- Mental status examination

- Safety (PD is associated with higher risk for suicidal ideation).9

TREATMENT INCLUDES CBT AND MEDICATION

PD is a chronic disease with a variable course, but the long-term prognosis is good. PD is usually treated in an outpatient setting. Consider hospitalization if the patient is suicidal, if the potential for life-threatening withdrawal symptoms is high (as with alcohol or benzodiazepines), or if the symptoms are severely debilitating or attempted outpatient treatment is unsuccessful. Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions are used for PD (see Figure), although there is not enough evidence to recommend one versus the other or combination therapy versus monotherapy.9

All Lacey’s test results come back negative, and the psychiatric assessment reveals that she meets the DSM-5 criteria for PD. Counting on the strength of their relationship, her PCP talks to her about PD and discusses treatment options, which include counseling, medication, or both. Lacey agrees to a referral for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a psychologist embedded at her primary care clinic and to begin taking medication. Her PCP starts her on sertraline 25 mg/d.

In CBT, Lacey’s psychologist teaches her about “fight or flight” and explains that it is a normal physiologic response that can lead to panic. Lacey learns to approach her physical symptoms in a different way, and how to breathe in a way that slows her panic reaction.

Consider SSRIs and SNRIs

Firstline medication is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), due to the better tolerability and lower adverse effect profile of these classes compared with the tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). MAOIs are usually reserved for patients in whom multiple medication trials have failed.

Special considerations. American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise starting with a very low dose of an SSRI or SNRI, such as paroxetine 10 mg/d (although

Keep in mind that the onset of therapeutic effect is between two and four weeks, but that clinical response can take eight to 12 weeks. Continue pharmacotherapy for at least one year. When discontinuing the medication, taper it slowly, and monitor the patient for withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of PD.9

Consider adding a benzodiazepine if symptoms are debilitating.9 Keep in mind, though, that the potential for addiction with these medications is high and they are intended to be used for only four to 12 weeks.8 Onset of action is within the first week, and a scheduled dosing regimen is preferred to giving the medication as needed. The starting dose (eg, clonazepam 0.25 mg bid) may be increased three to five days following initiation.9

Evidence supports the use of CBT for PD

CBT is an evidenced-based treatment for PD.10-13 Up to 75% of patients treated with CBT are panic free within four months.10 Other techniques proven effective are progressive muscle relaxation training, breathing retraining, psychoeducation, exposure, and imagery.14

Treatment with medications and CBT, either combined or used individually, is effective in 80% to 90% of cases.15 CBT has been shown to decrease the likelihood of relapse in the year following treatment.15 Good premorbid functioning and a brief duration of symptoms increase the likelihood of a good prognosis.15

WHEN TO REFER TO A PSYCHIATRIST

Consider referral to a psychiatrist when patients have a comorbid psychiatric condition that complicates the clinical picture (eg, substance abuse disorder), if the diagnosis is uncertain, or if the patient does not respond to one or two adequate trials of medication and psychotherapy. Although psychiatric follow-up is sometimes difficult due to a lack of psychiatrist availability locally, it is a best-practice recommendation.

Ten days after Lacey starts the sertraline 25 mg/d, she calls the PCP to report daily diarrhea. She stopped the sertraline on her own and is asking for another medication. She also expresses her frustration with the severity of the symptoms. She is having three to five panic attacks daily and has been missing many days of work.

On the day of her follow-up PCP appointment, Lacey also sees the psychologist. She reports that she’s been practicing relaxation breathing, tracking her panic attacks, limiting her caffeine intake, and exercising regularly. But the attacks are still occurring.

The PCP switches her to paroxetine 10 mg/d and, due to the severity of the symptoms, prescribes clonazepam 0.5 mg bid. Two weeks later, Lacey reports that she is feeling a little better, has returned to work, and is hopeful that she will be her “normal self again.” The PCP plans to encourage continuation of CBT, titrate the paroxetine to 20 to 40 mg/d based on symptoms, and slowly taper the clonazepam toward discontinuation in the near future.

Lacey, 37, is seen by her primary care provider (PCP) as follow-up to a visit she made to the emergency department (ED). She has gone to the ED four times in the past year. Each time, she presents with tachycardia, dyspnea, nausea, numbness in her extremities, and a fear that she is having a heart attack. Despite negative workups at each visit (ECG, cardiac enzymes, complete blood count, toxicology screen, Holter monitoring), Lacey is terrified that the ED doctors are missing something. She is still “rattled” by the chest pain and shortness of breath she experiences. Mild symptoms are persisting, and she is worried that she will have a heart attack and die without the treatment she believes she needs. How do you proceed?

Panic disorder (PD) is characterized by the spontaneous and unexpected occurrence of panic attacks and by at least one month of persistent worry about having another attack or significant maladaptive behaviors related to the attack. Frequency of such attacks can vary from several a day to only a few per year. In a panic attack, an intense fear develops abruptly and peaks within 10 minutes of onset. At least four of the following 13 symptoms must accompany the attack, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5)

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feeling of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

- Fear of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

- Paresthesia (numbness or tingling sensations)

- Chills or hot flushes.1

Lifetime incidence rates of PD are 1% to 3% for the general population.2 A closer look at patients presenting to the ED with chest pain reveals that 17% to 25% meet criteria for PD.3,4 And an estimated 6% of individuals experiencing a panic attack present to their primary care provider.5 Patients with PD tend to use health care resources at a disproportionately high rate.6

An international review of PD research suggests the average age of onset is 32 years.7 Triggers can vary widely, and no single stressor has been identified. The exact cause of PD is unknown, but a convergence of social and biological influences (including involvement of the amygdala) are implicated in its development.6 For individuals who have had a panic attack, 66.5% will have recurrent attacks.7 Lifetime prevalence of panic attacks is 13.2%.7

Differential goes far beyond myocardial infarction. Many medical conditions can mimic PD symptoms: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic diseases; endocrine diseases (eg, hyperthyroidism); drug intoxication (eg, stimulants [cocaine, amphetamines]); drug withdrawal (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, sedative-hypnotics); and ingestion of excessive quantities of caffeine. Common comorbid medical disorders include asthma, coronary artery disease, cancer, thyroid disease, hypertension, ulcer, and migraine headaches.8

When patients present with paniclike symptoms, suspect a possible medical condition when those symptoms include ataxia, altered mental status, or loss of bladder control, or when onset of panic symptoms occur later in life for a patient with no significant psychiatric history.

RULE OUT ORGANIC CAUSES

In addition to obtaining a complete history and doing a physical exam on patients with paniclike symptoms, you’ll also need to ensure that the following are done: a neurologic examination, standard laboratory testing (thyroid function, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel), and possible additional testing (eg, urine toxicology screen and

If organic causes are ruled out, focus on a psychiatric assessment, including

- History of the present illness (onset, symptoms, frequency, predisposing/precipitating factors)

- Psychiatric history

- History of substance use

- Family history of psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders)

- Social history (life events, including those preceding the onset of panic; history of child abuse)

- Medications

- Mental status examination

- Safety (PD is associated with higher risk for suicidal ideation).9

TREATMENT INCLUDES CBT AND MEDICATION

PD is a chronic disease with a variable course, but the long-term prognosis is good. PD is usually treated in an outpatient setting. Consider hospitalization if the patient is suicidal, if the potential for life-threatening withdrawal symptoms is high (as with alcohol or benzodiazepines), or if the symptoms are severely debilitating or attempted outpatient treatment is unsuccessful. Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions are used for PD (see Figure), although there is not enough evidence to recommend one versus the other or combination therapy versus monotherapy.9

All Lacey’s test results come back negative, and the psychiatric assessment reveals that she meets the DSM-5 criteria for PD. Counting on the strength of their relationship, her PCP talks to her about PD and discusses treatment options, which include counseling, medication, or both. Lacey agrees to a referral for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a psychologist embedded at her primary care clinic and to begin taking medication. Her PCP starts her on sertraline 25 mg/d.

In CBT, Lacey’s psychologist teaches her about “fight or flight” and explains that it is a normal physiologic response that can lead to panic. Lacey learns to approach her physical symptoms in a different way, and how to breathe in a way that slows her panic reaction.

Consider SSRIs and SNRIs

Firstline medication is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), due to the better tolerability and lower adverse effect profile of these classes compared with the tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). MAOIs are usually reserved for patients in whom multiple medication trials have failed.

Special considerations. American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise starting with a very low dose of an SSRI or SNRI, such as paroxetine 10 mg/d (although