User login

School avoidance: How to help when a child refuses to go

THE CASE

Juana*, a 10-year-old who identifies as a cisgender, Hispanic female, was referred to our integrated behavioral health program by her primary care physician. Her mother was concerned because Juana had been refusing to attend school due to complaints of gastrointestinal upset. This concern began when Juana was in first grade but had increased in severity over the past few months.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that she initially did not want to attend school due to academic difficulties and bullying. However, since COVID-19, her fears of attending school had significantly worsened. Juana’s mother’s primary language was Spanish and she had limited English proficiency; she reported difficulty communicating with school personnel about Juana’s poor attendance.

Juana had recently had a complete medical work-up for her gastrointestinal concerns, with negative results. Since the negative work-up, Juana’s mother had told her daughter that she would be punished if she didn’t go to school.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

School avoidance, also referred to as school refusal, is a symptom of an emotional condition that manifests as a child refusing to go to school or having difficulty going to school or remaining in the classroom for the entire day. School avoidance is not a clinical diagnosis but often is related to an underlying disorder.1

School avoidance is common, affecting 5% to 28% of youth sometime in their school career.2 Available data are not specific to school avoidance but focus on chronic absenteeism (missing ≥ 15 days per school year). Rates of chronic absenteeism are high in elementary and middle school (about 14% each) and tend to increase in high school (about 21%).3 Students with disabilities are 1.5 times more likely to be chronically absent than students without disabilities.3 Compared to White students, American Indian and Pacific Islander students are > 50% more likely, Black students 40% more likely, and Hispanic students 17% more likely to miss ≥ 3 weeks of school.3 Rates of chronic absenteeism are similar (about 16%) for males and females.3

Absenteeism can have immediate and long-term negative effects.4 School attendance issues are correlated to negative life outcomes, such as delinquency, teen pregnancy, substance use, and poor academic achievement.5 According to the US Department of Education, individuals who chronically miss school are less likely to achieve educational milestones (particularly in younger years) and may be more likely to drop out of school.3

What school avoidance is (and what it isn’t)

It is important to distinguish school avoidance from truancy. Truancy often is associated with antisocial behavior such as lying and stealing, while school avoidance occurs in the absence of significant antisocial disorders.6 With truancy, the absence usually is hidden from the parent. In contrast, with school avoidance, the parents usually know where their child is; the child often spends the day secluded in their bedroom. Students who engage in truancy do not demonstrate excessive anxiety about attending school but may have decreased interest in schoolwork and academic performance.6 With school avoidance, the child exhibits severe emotional distress about attending school but is willing to complete schoolwork at home.

Why children may avoid school

School avoidance is a biopsychosocial condition with a multitude of underlying causes.4 It is associated most commonly with anxiety disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, including but not limited to learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.1 Depressive disorders also have been associated with school avoidance.7 Social concerns related to changes with school personnel or classes, academic challenges, bullying, health emergencies, and family stressors also can result in symptoms of school avoidance.1

Continue to: A child seeking to avoid...

A child seeking to avoid school may be motivated by potential negative and/or positive effects of doing so. Kearney and Silverman8 identified 4 primary functions of school refusal behaviors:

- avoiding stimuli at school that lend to negative affect (depression, anxiety)

- escaping the social interactions and/or situations for evaluation that occur at school

- gaining more attention from caregivers, and

- obtaining tangible rewards or benefits outside the school environment.

How school avoidance manifests

School avoidance has attributes of internalizing (depression, anxiety, somatic complaints) and externalizing (aggression, tantrums, running away, clinginess) behaviors. It can cause distress for the student, parents and caregivers, and school personnel.

The avoidance may manifest with behaviors such as crying, hiding, emotional outbursts, and refusing to move prior to the start of the school day. Additionally, the child may beg their parents not to make them go to school or, when at school, they may leave the classroom to go to a safe place such as the nurse’s or counselor’s office.

The avoidance may occur abruptly, such as after a break in the school schedule or a change of school. Or it may be the final result of the student’s gradual inability to cope with the underlying issue.

How to assess for school avoidance

Due to the multifactorial nature of this presenting concern, a comprehensive evaluation is recommended when school avoidance is reported.4 Often the child will present with physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, and palpitations. A thorough medical examination should be performed to rule out a physiological cause. The medical visit should include clinical interviews with the patient and family members or guardians.

Continue to: To identify school avoidance...

To identify school avoidance in pediatric and adolescent populations, medical history and physical examination—along with social history to better understand familial, social, and academic concerns—should be a regular part of the medical encounter. The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R) for both parents and their children was developed to assess for school avoidance and can be utilized within the primary care setting. Additional psychiatric history for both the family and patient may be beneficial, due to associations between parental mental health concerns and school avoidance in their children.9,10

Assessment for an underlying mental health condition, such as an anxiety or depressive disorder, should be completed when a patient presents with school avoidance.4 More than one-third of children with behavioral problems, such as school avoidance, have been diagnosed with anxiety.11 The 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 7.8% of children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 years had a current anxiety disorder, leading the US Preventive Services Task Force to recommend screening for anxiety in children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years.12,13 Furthermore, if academic achievement is of concern, then consideration of further assessment for neurodevelopmental disorders is warranted.1

Treatment is multimodal and multidisciplinary

Treatment for school avoidance is often multimodal and may involve interdisciplinary, team-based care including the medical provider, school system (eg, Child Study Team), family, and mental health care provider.1,4

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most-studied intervention for school avoidance, with behavioral, exposure-based interventions often central to therapeutic gains in treatment.1,14,15 The goals of treatment are to increase school attendance while decreasing emotional distress through various strategies, including exposure-based interventions, contingency management with parents and school staff, relaxation training, and/or social skills training.14,16 Collaborative involvement between the medical provider and the school system is key to successful treatment.

Medication may be considered alone or in combination with CBT when comorbid mental health conditions have been identified. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—including fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram—are considered first-line treatment for anxiety in children and adolescents.17 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, also have been shown to be effective. Duloxetine is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children ages 7 years and older.17

Continue to: SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning...

SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning from the FDA for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and adolescents. Although this risk is rare, it should be discussed with the patient and parent/guardian in order to obtain informed consent prior to treatment initiation.

Medication should be started at the lowest possible dose and increased gradually. Patients should remain on the medication for 6 to 12 months after symptom resolution and should be tapered during a nonstressful time, such as the summer break.

THE CASE

Based on the concerns of continued school refusal after negative gastrointestinal work-up, Juana’s physician screened her for anxiety and conducted a clinical interview to better understand any psychosocial concerns. Juana’s score of 10 on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale indicated moderate anxiety. She reported symptoms consistent with social anxiety disorder contributing to school avoidance.

The physician consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant (BHC) to confirm the multimodal treatment plan, which was then discussed with Juana and her mother. The physician discussed medication options (SSRIs) and provided documentation (in both English and Spanish) from the visit to Juana’s mother so she could initiate a school-based intervention with the Child Study Team at Juana’s school. A plan for CBT—including a collaborative contingency management plan between the patient and her parent (eg, a reward chart for attending school) and exposure interventions (eg, a graduated plan to participate in school-based activities with the end goal to resume full school attendance)—was developed with the BHC. Biweekly follow-up appointments were scheduled with the BHC and monthly appointments were scheduled with the physician to reinforce the interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L. C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 East 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77840; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu

1. School Avoidance Alliance. School avoidance facts. Published September 16, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://schoolavoidance.org/school-avoidance-facts/

2. Kearney CA. School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Functional Approach to Assessment and Treatment. American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. US Department of Education. Chronic absenteeism in the nation’s schools: a hidden educational crisis. Updated January 2019. Accessed August 3, 2023. www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html

4. Allen CW, Diamond-Myrsten S, Rollins LK. School absenteeism in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:738-744.

5. Gonzálvez C, Díaz-Herrero Á, Vicent M, et al. School refusal behavior: latent class analysis approach and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms. Curr Psychology. 2022;41:2078-2088. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00711-6

6. Fremont WP. School refusal in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1555-1560.

7. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:822-826. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x

8. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychology Sci Pract. 1996;3:339-354. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x

9. Kearney CA, Albano AM. School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised C. Oxford University Press; 2007.

10. Heyne D. School refusal. In: Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT (eds). Practitioner’s Guide to Evidence-based Psychotherapy. Springer Science + Business Media. 2006;600-619. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-28370-8_60

11. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatrics. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

12. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2023. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

13. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Final Recommendation Statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed August 4, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

14. Maynard BR, Brendel KE, Bulanda JJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Rev. 2015;11:1-76. doi: 10.4073/csr.2015.12

15. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: Parent Workbook. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2018. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780190604080.001.0001

16. Heyne DA, Sauter FM. School refusal. In: Essau CA, Ollendick TH. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety. Wiley Blackwell; 2013:471-517.

17. Kowalchuk A, Gonzalez SJ, Zoorob RJ. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106:657-664.

THE CASE

Juana*, a 10-year-old who identifies as a cisgender, Hispanic female, was referred to our integrated behavioral health program by her primary care physician. Her mother was concerned because Juana had been refusing to attend school due to complaints of gastrointestinal upset. This concern began when Juana was in first grade but had increased in severity over the past few months.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that she initially did not want to attend school due to academic difficulties and bullying. However, since COVID-19, her fears of attending school had significantly worsened. Juana’s mother’s primary language was Spanish and she had limited English proficiency; she reported difficulty communicating with school personnel about Juana’s poor attendance.

Juana had recently had a complete medical work-up for her gastrointestinal concerns, with negative results. Since the negative work-up, Juana’s mother had told her daughter that she would be punished if she didn’t go to school.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

School avoidance, also referred to as school refusal, is a symptom of an emotional condition that manifests as a child refusing to go to school or having difficulty going to school or remaining in the classroom for the entire day. School avoidance is not a clinical diagnosis but often is related to an underlying disorder.1

School avoidance is common, affecting 5% to 28% of youth sometime in their school career.2 Available data are not specific to school avoidance but focus on chronic absenteeism (missing ≥ 15 days per school year). Rates of chronic absenteeism are high in elementary and middle school (about 14% each) and tend to increase in high school (about 21%).3 Students with disabilities are 1.5 times more likely to be chronically absent than students without disabilities.3 Compared to White students, American Indian and Pacific Islander students are > 50% more likely, Black students 40% more likely, and Hispanic students 17% more likely to miss ≥ 3 weeks of school.3 Rates of chronic absenteeism are similar (about 16%) for males and females.3

Absenteeism can have immediate and long-term negative effects.4 School attendance issues are correlated to negative life outcomes, such as delinquency, teen pregnancy, substance use, and poor academic achievement.5 According to the US Department of Education, individuals who chronically miss school are less likely to achieve educational milestones (particularly in younger years) and may be more likely to drop out of school.3

What school avoidance is (and what it isn’t)

It is important to distinguish school avoidance from truancy. Truancy often is associated with antisocial behavior such as lying and stealing, while school avoidance occurs in the absence of significant antisocial disorders.6 With truancy, the absence usually is hidden from the parent. In contrast, with school avoidance, the parents usually know where their child is; the child often spends the day secluded in their bedroom. Students who engage in truancy do not demonstrate excessive anxiety about attending school but may have decreased interest in schoolwork and academic performance.6 With school avoidance, the child exhibits severe emotional distress about attending school but is willing to complete schoolwork at home.

Why children may avoid school

School avoidance is a biopsychosocial condition with a multitude of underlying causes.4 It is associated most commonly with anxiety disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, including but not limited to learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.1 Depressive disorders also have been associated with school avoidance.7 Social concerns related to changes with school personnel or classes, academic challenges, bullying, health emergencies, and family stressors also can result in symptoms of school avoidance.1

Continue to: A child seeking to avoid...

A child seeking to avoid school may be motivated by potential negative and/or positive effects of doing so. Kearney and Silverman8 identified 4 primary functions of school refusal behaviors:

- avoiding stimuli at school that lend to negative affect (depression, anxiety)

- escaping the social interactions and/or situations for evaluation that occur at school

- gaining more attention from caregivers, and

- obtaining tangible rewards or benefits outside the school environment.

How school avoidance manifests

School avoidance has attributes of internalizing (depression, anxiety, somatic complaints) and externalizing (aggression, tantrums, running away, clinginess) behaviors. It can cause distress for the student, parents and caregivers, and school personnel.

The avoidance may manifest with behaviors such as crying, hiding, emotional outbursts, and refusing to move prior to the start of the school day. Additionally, the child may beg their parents not to make them go to school or, when at school, they may leave the classroom to go to a safe place such as the nurse’s or counselor’s office.

The avoidance may occur abruptly, such as after a break in the school schedule or a change of school. Or it may be the final result of the student’s gradual inability to cope with the underlying issue.

How to assess for school avoidance

Due to the multifactorial nature of this presenting concern, a comprehensive evaluation is recommended when school avoidance is reported.4 Often the child will present with physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, and palpitations. A thorough medical examination should be performed to rule out a physiological cause. The medical visit should include clinical interviews with the patient and family members or guardians.

Continue to: To identify school avoidance...

To identify school avoidance in pediatric and adolescent populations, medical history and physical examination—along with social history to better understand familial, social, and academic concerns—should be a regular part of the medical encounter. The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R) for both parents and their children was developed to assess for school avoidance and can be utilized within the primary care setting. Additional psychiatric history for both the family and patient may be beneficial, due to associations between parental mental health concerns and school avoidance in their children.9,10

Assessment for an underlying mental health condition, such as an anxiety or depressive disorder, should be completed when a patient presents with school avoidance.4 More than one-third of children with behavioral problems, such as school avoidance, have been diagnosed with anxiety.11 The 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 7.8% of children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 years had a current anxiety disorder, leading the US Preventive Services Task Force to recommend screening for anxiety in children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years.12,13 Furthermore, if academic achievement is of concern, then consideration of further assessment for neurodevelopmental disorders is warranted.1

Treatment is multimodal and multidisciplinary

Treatment for school avoidance is often multimodal and may involve interdisciplinary, team-based care including the medical provider, school system (eg, Child Study Team), family, and mental health care provider.1,4

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most-studied intervention for school avoidance, with behavioral, exposure-based interventions often central to therapeutic gains in treatment.1,14,15 The goals of treatment are to increase school attendance while decreasing emotional distress through various strategies, including exposure-based interventions, contingency management with parents and school staff, relaxation training, and/or social skills training.14,16 Collaborative involvement between the medical provider and the school system is key to successful treatment.

Medication may be considered alone or in combination with CBT when comorbid mental health conditions have been identified. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—including fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram—are considered first-line treatment for anxiety in children and adolescents.17 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, also have been shown to be effective. Duloxetine is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children ages 7 years and older.17

Continue to: SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning...

SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning from the FDA for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and adolescents. Although this risk is rare, it should be discussed with the patient and parent/guardian in order to obtain informed consent prior to treatment initiation.

Medication should be started at the lowest possible dose and increased gradually. Patients should remain on the medication for 6 to 12 months after symptom resolution and should be tapered during a nonstressful time, such as the summer break.

THE CASE

Based on the concerns of continued school refusal after negative gastrointestinal work-up, Juana’s physician screened her for anxiety and conducted a clinical interview to better understand any psychosocial concerns. Juana’s score of 10 on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale indicated moderate anxiety. She reported symptoms consistent with social anxiety disorder contributing to school avoidance.

The physician consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant (BHC) to confirm the multimodal treatment plan, which was then discussed with Juana and her mother. The physician discussed medication options (SSRIs) and provided documentation (in both English and Spanish) from the visit to Juana’s mother so she could initiate a school-based intervention with the Child Study Team at Juana’s school. A plan for CBT—including a collaborative contingency management plan between the patient and her parent (eg, a reward chart for attending school) and exposure interventions (eg, a graduated plan to participate in school-based activities with the end goal to resume full school attendance)—was developed with the BHC. Biweekly follow-up appointments were scheduled with the BHC and monthly appointments were scheduled with the physician to reinforce the interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L. C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 East 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77840; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu

THE CASE

Juana*, a 10-year-old who identifies as a cisgender, Hispanic female, was referred to our integrated behavioral health program by her primary care physician. Her mother was concerned because Juana had been refusing to attend school due to complaints of gastrointestinal upset. This concern began when Juana was in first grade but had increased in severity over the past few months.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that she initially did not want to attend school due to academic difficulties and bullying. However, since COVID-19, her fears of attending school had significantly worsened. Juana’s mother’s primary language was Spanish and she had limited English proficiency; she reported difficulty communicating with school personnel about Juana’s poor attendance.

Juana had recently had a complete medical work-up for her gastrointestinal concerns, with negative results. Since the negative work-up, Juana’s mother had told her daughter that she would be punished if she didn’t go to school.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

School avoidance, also referred to as school refusal, is a symptom of an emotional condition that manifests as a child refusing to go to school or having difficulty going to school or remaining in the classroom for the entire day. School avoidance is not a clinical diagnosis but often is related to an underlying disorder.1

School avoidance is common, affecting 5% to 28% of youth sometime in their school career.2 Available data are not specific to school avoidance but focus on chronic absenteeism (missing ≥ 15 days per school year). Rates of chronic absenteeism are high in elementary and middle school (about 14% each) and tend to increase in high school (about 21%).3 Students with disabilities are 1.5 times more likely to be chronically absent than students without disabilities.3 Compared to White students, American Indian and Pacific Islander students are > 50% more likely, Black students 40% more likely, and Hispanic students 17% more likely to miss ≥ 3 weeks of school.3 Rates of chronic absenteeism are similar (about 16%) for males and females.3

Absenteeism can have immediate and long-term negative effects.4 School attendance issues are correlated to negative life outcomes, such as delinquency, teen pregnancy, substance use, and poor academic achievement.5 According to the US Department of Education, individuals who chronically miss school are less likely to achieve educational milestones (particularly in younger years) and may be more likely to drop out of school.3

What school avoidance is (and what it isn’t)

It is important to distinguish school avoidance from truancy. Truancy often is associated with antisocial behavior such as lying and stealing, while school avoidance occurs in the absence of significant antisocial disorders.6 With truancy, the absence usually is hidden from the parent. In contrast, with school avoidance, the parents usually know where their child is; the child often spends the day secluded in their bedroom. Students who engage in truancy do not demonstrate excessive anxiety about attending school but may have decreased interest in schoolwork and academic performance.6 With school avoidance, the child exhibits severe emotional distress about attending school but is willing to complete schoolwork at home.

Why children may avoid school

School avoidance is a biopsychosocial condition with a multitude of underlying causes.4 It is associated most commonly with anxiety disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, including but not limited to learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.1 Depressive disorders also have been associated with school avoidance.7 Social concerns related to changes with school personnel or classes, academic challenges, bullying, health emergencies, and family stressors also can result in symptoms of school avoidance.1

Continue to: A child seeking to avoid...

A child seeking to avoid school may be motivated by potential negative and/or positive effects of doing so. Kearney and Silverman8 identified 4 primary functions of school refusal behaviors:

- avoiding stimuli at school that lend to negative affect (depression, anxiety)

- escaping the social interactions and/or situations for evaluation that occur at school

- gaining more attention from caregivers, and

- obtaining tangible rewards or benefits outside the school environment.

How school avoidance manifests

School avoidance has attributes of internalizing (depression, anxiety, somatic complaints) and externalizing (aggression, tantrums, running away, clinginess) behaviors. It can cause distress for the student, parents and caregivers, and school personnel.

The avoidance may manifest with behaviors such as crying, hiding, emotional outbursts, and refusing to move prior to the start of the school day. Additionally, the child may beg their parents not to make them go to school or, when at school, they may leave the classroom to go to a safe place such as the nurse’s or counselor’s office.

The avoidance may occur abruptly, such as after a break in the school schedule or a change of school. Or it may be the final result of the student’s gradual inability to cope with the underlying issue.

How to assess for school avoidance

Due to the multifactorial nature of this presenting concern, a comprehensive evaluation is recommended when school avoidance is reported.4 Often the child will present with physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, and palpitations. A thorough medical examination should be performed to rule out a physiological cause. The medical visit should include clinical interviews with the patient and family members or guardians.

Continue to: To identify school avoidance...

To identify school avoidance in pediatric and adolescent populations, medical history and physical examination—along with social history to better understand familial, social, and academic concerns—should be a regular part of the medical encounter. The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R) for both parents and their children was developed to assess for school avoidance and can be utilized within the primary care setting. Additional psychiatric history for both the family and patient may be beneficial, due to associations between parental mental health concerns and school avoidance in their children.9,10

Assessment for an underlying mental health condition, such as an anxiety or depressive disorder, should be completed when a patient presents with school avoidance.4 More than one-third of children with behavioral problems, such as school avoidance, have been diagnosed with anxiety.11 The 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 7.8% of children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 years had a current anxiety disorder, leading the US Preventive Services Task Force to recommend screening for anxiety in children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years.12,13 Furthermore, if academic achievement is of concern, then consideration of further assessment for neurodevelopmental disorders is warranted.1

Treatment is multimodal and multidisciplinary

Treatment for school avoidance is often multimodal and may involve interdisciplinary, team-based care including the medical provider, school system (eg, Child Study Team), family, and mental health care provider.1,4

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most-studied intervention for school avoidance, with behavioral, exposure-based interventions often central to therapeutic gains in treatment.1,14,15 The goals of treatment are to increase school attendance while decreasing emotional distress through various strategies, including exposure-based interventions, contingency management with parents and school staff, relaxation training, and/or social skills training.14,16 Collaborative involvement between the medical provider and the school system is key to successful treatment.

Medication may be considered alone or in combination with CBT when comorbid mental health conditions have been identified. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—including fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram—are considered first-line treatment for anxiety in children and adolescents.17 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, also have been shown to be effective. Duloxetine is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children ages 7 years and older.17

Continue to: SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning...

SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning from the FDA for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and adolescents. Although this risk is rare, it should be discussed with the patient and parent/guardian in order to obtain informed consent prior to treatment initiation.

Medication should be started at the lowest possible dose and increased gradually. Patients should remain on the medication for 6 to 12 months after symptom resolution and should be tapered during a nonstressful time, such as the summer break.

THE CASE

Based on the concerns of continued school refusal after negative gastrointestinal work-up, Juana’s physician screened her for anxiety and conducted a clinical interview to better understand any psychosocial concerns. Juana’s score of 10 on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale indicated moderate anxiety. She reported symptoms consistent with social anxiety disorder contributing to school avoidance.

The physician consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant (BHC) to confirm the multimodal treatment plan, which was then discussed with Juana and her mother. The physician discussed medication options (SSRIs) and provided documentation (in both English and Spanish) from the visit to Juana’s mother so she could initiate a school-based intervention with the Child Study Team at Juana’s school. A plan for CBT—including a collaborative contingency management plan between the patient and her parent (eg, a reward chart for attending school) and exposure interventions (eg, a graduated plan to participate in school-based activities with the end goal to resume full school attendance)—was developed with the BHC. Biweekly follow-up appointments were scheduled with the BHC and monthly appointments were scheduled with the physician to reinforce the interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L. C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 East 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77840; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu

1. School Avoidance Alliance. School avoidance facts. Published September 16, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://schoolavoidance.org/school-avoidance-facts/

2. Kearney CA. School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Functional Approach to Assessment and Treatment. American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. US Department of Education. Chronic absenteeism in the nation’s schools: a hidden educational crisis. Updated January 2019. Accessed August 3, 2023. www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html

4. Allen CW, Diamond-Myrsten S, Rollins LK. School absenteeism in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:738-744.

5. Gonzálvez C, Díaz-Herrero Á, Vicent M, et al. School refusal behavior: latent class analysis approach and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms. Curr Psychology. 2022;41:2078-2088. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00711-6

6. Fremont WP. School refusal in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1555-1560.

7. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:822-826. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x

8. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychology Sci Pract. 1996;3:339-354. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x

9. Kearney CA, Albano AM. School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised C. Oxford University Press; 2007.

10. Heyne D. School refusal. In: Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT (eds). Practitioner’s Guide to Evidence-based Psychotherapy. Springer Science + Business Media. 2006;600-619. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-28370-8_60

11. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatrics. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

12. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2023. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

13. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Final Recommendation Statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed August 4, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

14. Maynard BR, Brendel KE, Bulanda JJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Rev. 2015;11:1-76. doi: 10.4073/csr.2015.12

15. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: Parent Workbook. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2018. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780190604080.001.0001

16. Heyne DA, Sauter FM. School refusal. In: Essau CA, Ollendick TH. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety. Wiley Blackwell; 2013:471-517.

17. Kowalchuk A, Gonzalez SJ, Zoorob RJ. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106:657-664.

1. School Avoidance Alliance. School avoidance facts. Published September 16, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://schoolavoidance.org/school-avoidance-facts/

2. Kearney CA. School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Functional Approach to Assessment and Treatment. American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. US Department of Education. Chronic absenteeism in the nation’s schools: a hidden educational crisis. Updated January 2019. Accessed August 3, 2023. www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html

4. Allen CW, Diamond-Myrsten S, Rollins LK. School absenteeism in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:738-744.

5. Gonzálvez C, Díaz-Herrero Á, Vicent M, et al. School refusal behavior: latent class analysis approach and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms. Curr Psychology. 2022;41:2078-2088. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00711-6

6. Fremont WP. School refusal in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1555-1560.

7. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:822-826. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x

8. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychology Sci Pract. 1996;3:339-354. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x

9. Kearney CA, Albano AM. School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised C. Oxford University Press; 2007.

10. Heyne D. School refusal. In: Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT (eds). Practitioner’s Guide to Evidence-based Psychotherapy. Springer Science + Business Media. 2006;600-619. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-28370-8_60

11. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatrics. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

12. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2023. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

13. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Final Recommendation Statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed August 4, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

14. Maynard BR, Brendel KE, Bulanda JJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Rev. 2015;11:1-76. doi: 10.4073/csr.2015.12

15. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: Parent Workbook. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2018. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780190604080.001.0001

16. Heyne DA, Sauter FM. School refusal. In: Essau CA, Ollendick TH. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety. Wiley Blackwell; 2013:471-517.

17. Kowalchuk A, Gonzalez SJ, Zoorob RJ. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106:657-664.

Caring for the caregiver in dementia

THE CASE

Sam C* is a 68-year-old man who presented to his family physician in a rural health clinic due to concerns about weight loss. Since his visit 8 months prior, Mr. C unintentionally had lost 20 pounds. Upon questioning, Mr. C also reported feeling irritable and having difficulty with sleep and concentration.

A review of systems did not indicate the presence of infection or other medical conditions. In the 6 years since becoming a patient to the practice, he had reported no chronic health concerns, was taking no medications, and had only been to the clinic for his annual check-up appointments. He completed a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and scored 18, indicating moderately severe depression.

Mr. C had established care with his physician when he moved to the area from out of state so that he could be closer to his parents, who were in their mid-80s at the time. Mr. C’s physician also had been the family physician for his parents for the previous 20 years. Three years prior to Mr. C’s presentation for weight loss, his mother had received a diagnosis of acute leukemia; she died a year later.

Over the past year, Mr. C had needed to take a more active role in the care of his father, who was now in his early 90s. Mr. C’s father, who was previously in excellent health, had begun to develop significant health problems, including degenerative arthritis and progressive vascular dementia. He also had ataxia, leading to poor mobility, and a neurogenic bladder requiring self-catheterization, which required Mr. C’s assistance. Mr. C lived next door to his father and provided frequent assistance with activities of daily living. However, his father, who always had been the dominant figure in the family, was determined to maintain his independence and not relinquish control to others.

The strain of caregiving activities, along with managing his father’s inflexibility, was causing increasing distress for Mr. C. As he told his family physician, “I just don’t know what to do.”

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

It is estimated that more than 11 million Americans provided more than 18 billion hours in unpaid support for individuals with dementia in 2022, averaging 30 hours of care per caregiver per week.1 As individuals with dementia progressively decline, they require increased assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs, such as bathing and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs, such as paying bills and using transportation). Most of this assistance comes from informal caregiving provided by family members and friends.

Caregiver burden can be defined as “the strain or load borne by a person who cares for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member.”2 Caregiver stress has been found to be higher for dementia caregiving than other types of caregiving.3 In particular, caring for someone with greater behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSDs) has been associated with higher caregiver burden.4-

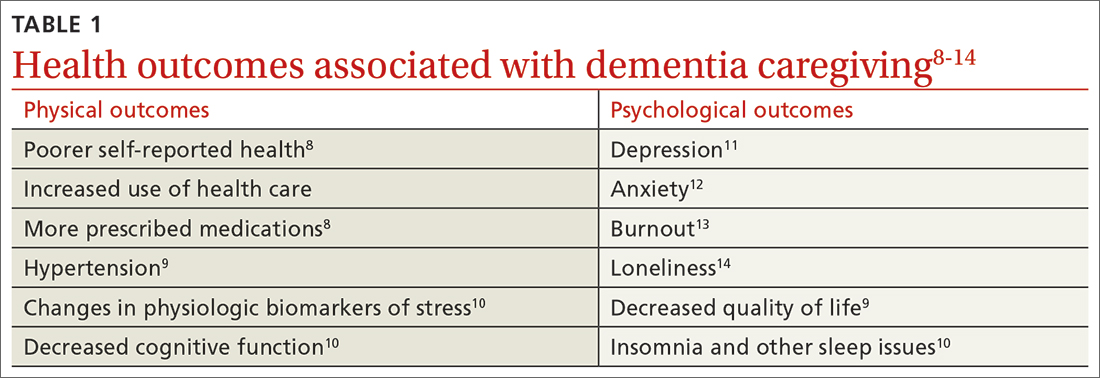

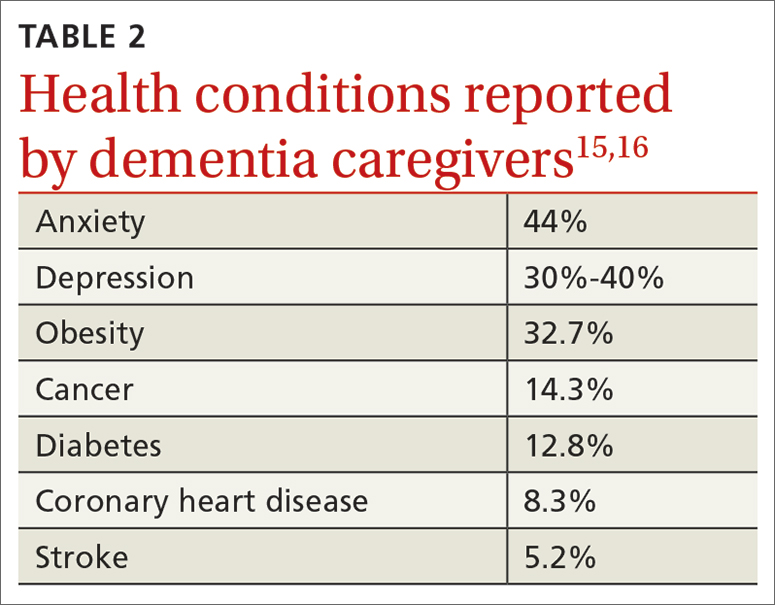

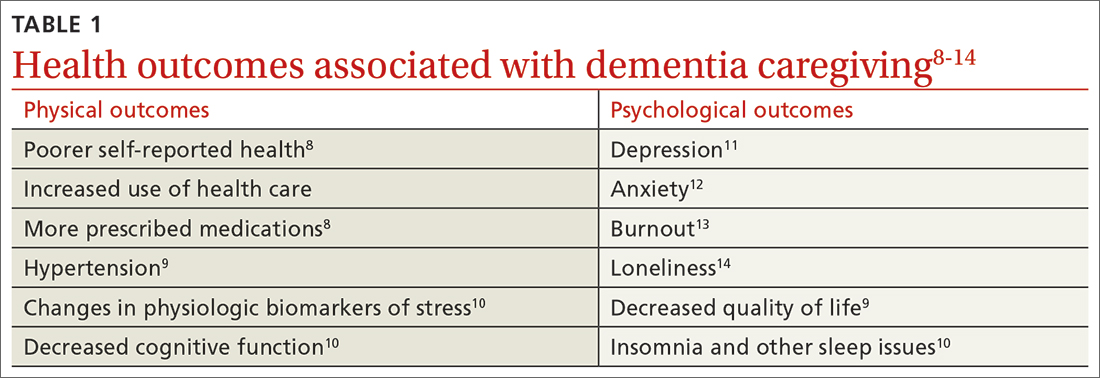

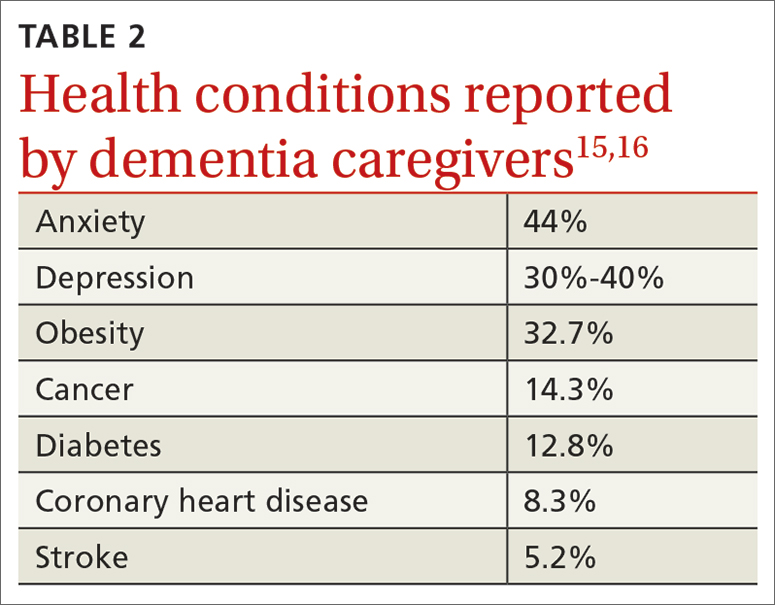

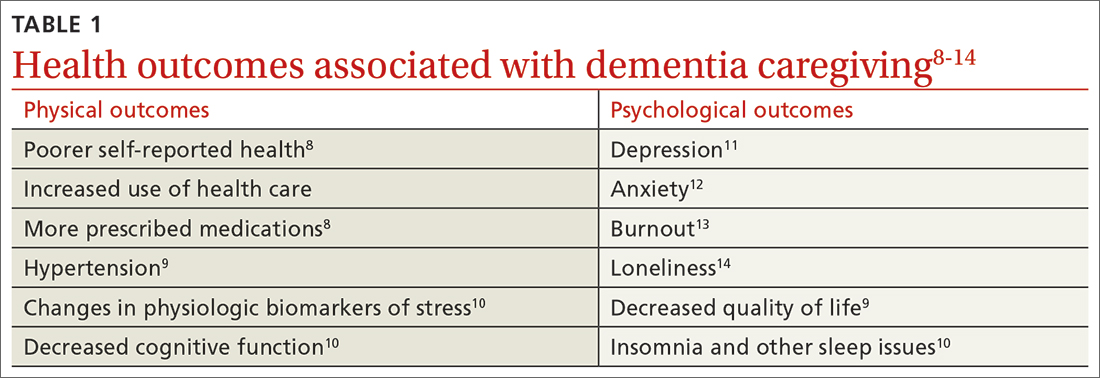

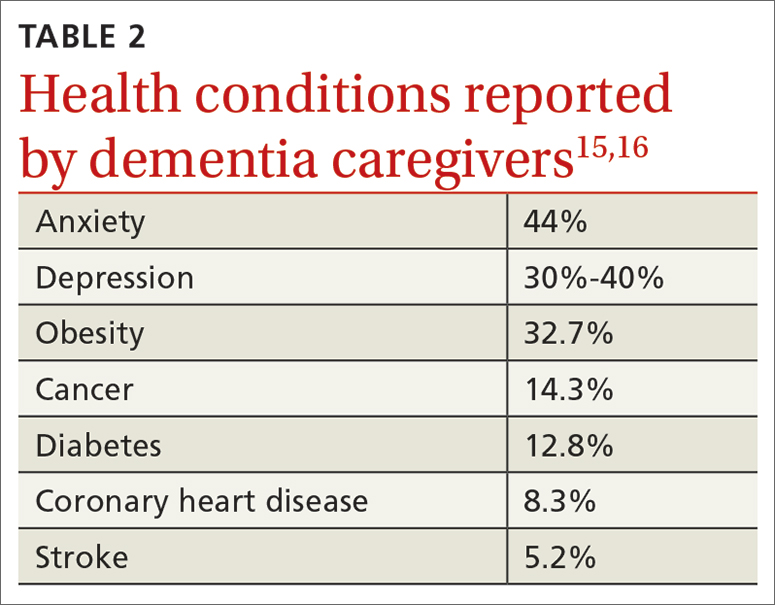

Beyond the subjective burden of caregiving, there are other potential negative consequences for dementia caregivers (see TABLE 18-14 and TABLE 215,16). In addition, caregiver distress is related to a number of care recipient outcomes, including earlier institutionalization, more hospitalizations, more BPSDs, poorer quality of life, and greater likelihood of experiencing elder abuse.17

Assessment, reassessment are key to meeting needs

Numerous factors can foster caregiver well-being, including feelings of accomplishment and contribution, a strengthening of the relationship with the care recipient, and feeling supported by friends, family, and formal care systems.18,19 Family physicians can play an important role by assessing and supporting patients with dementia and their caregivers. Ideally, the individual with dementia and the caregiver will be assessed both together and separately.

A thorough assessment includes gathering information about the context and quality of the caregiving relationship; caregiver perception of the care recipient’s health and functional status; caregiver values and preferences; caregiver well-being (including mental health assessment); caregiver skills, abilities, and knowledge about caregiving; and positive and negative consequences of caregiving.20 Caregiver needs—including informational, care support, emotional, physical, and social needs—also should be assessed.

Continue to: Tools are available...

Tools are available to facilitate caregiver assessment. For example, the Zarit Burden Interview is a 22-item self-report measure that can be given to the caregiver21; shorter versions (4 and 12 items) are also available.22 Another resource available for caregiver assessment guidance is a toolkit developed by the Family Caregiver Alliance.20

Continually assess for changing needs

As the condition of the individual with dementia progresses, it will be important to reassess the caregiver, as stressors and needs will change over the course of the caregiving relationship. Support should be adapted accordingly.

In the early stage of dementia, caregivers may need information on disease progression and dementia care planning, ways to navigate the health care system, financial planning, and useful resources. Caregivers also may need emotional support to help them adapt to the role of caregiver, deal with denial, and manage their stress.23,24

With dementia progression, caregivers may need support related to increased decision-making responsibility, managing challenging behaviors, assisting with ADLs and IADLs, and identifying opportunities to meet personal social and well-being needs. They also may need support to accept the changes they are seeing in the individual with dementia and the shifts they are experiencing in their relationship with him or her.23,25

In late-stage dementia, caregiver needs tend to shift to determining the need for long-term care placement vs staying at home, end-of-life planning, loneliness, and anticipatory grief.23,26 Support with managing changing and accumulating stress typically remains a primary need throughout the progression of dementia.27

Continue to: Specific populations have distinct needs

Specific populations have distinct needs. Some caregivers, including members of the LGBTQ+ community and different racial and ethnic groups, as well as caregivers of people with younger-onset dementia, may have additional support needs.28

For example, African American and Latino caregivers tend to have caregiving relationships of longer duration, requiring more time-intensive care, but use fewer formal support services than White caregivers.29 Caregivers from non-White racial and ethnic groups also are more likely to experience discrimination when interacting with health care services on behalf of care recipients.30

Having an awareness of potential specialized needs may help to prevent or address potential care disparities, and cultural humility may help to improve caregiver experiences with primary care physicians.

Resources to support caregivers

Family physicians are well situated to provide informational and emotional support for both patients with dementia and their informal care providers.31 Given the variability of caregiver concerns, multicomponent interventions addressing informational, self-care, social support, and financial needs often are needed.31 Supportive counseling and psychoeducation can help dementia caregivers with stress management, self-care, coping, and skills training—supporting the development of self-efficacy.32,33

Outside resources. Although significant caregiver support can be provided directly by the physician, caregivers should be connected with outside resources, including support groups, counselors, psychotherapists, financial and legal support, and formal care services

Continue to: Psychosocial and complementary interventions

Psychosocial and complementary interventions. Various psychosocial interventions (eg, psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, support groups) have been found to be beneficial in alleviating caregiver symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and improving well-being, perceived burden, and quality of life. However, systematic reviews have found variability in the degree of helpfulness of these interventions.35,36

Some caregivers and care recipients may benefit from complementary and integrative medicine referrals. Mind–body therapies such as mindfulness, yoga, and Tai Chi have shown some beneficial effects.37

Online resources. Caregivers also can be directed to online resources from organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org), the National Institutes of Health (www.alzheimers.gov), and the Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org).

In rural settings, such as the one in which this case took place, online resources may decrease some barriers to supporting caregivers.38 Internet-based interventions also have been found to have some benefit for dementia caregivers.31,39

However, some rural locations continue to have limited reliable Internet services.40 In affected areas, a strong relationship with a primary care physician may be even more important to the well-being of caregivers, since other support services may be less accessible.41

Continue to: Impacts of the pandemic

Impacts of the pandemic. Although our case took place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to acknowledge ways the pandemic has impacted informal dementia caregiving.

Caregiver stress, depression, and anxiety increased during the pandemic, and the need for greater home confinement and social distancing amplified the negative impact of social isolation, including loneliness, on caregivers.42,43 Caregivers often needed to increase their caregiving responsibilities and had more difficulty with care coordination due to limited access to in-person resources.43 The pandemic led to increased reliance on technology and telehealth in the support of dementia caregivers.43

THE CASE

The physician prescribed mirtazapine for Mr. C, titrating the dose as needed to address depressive symptoms and promote weight gain. The physician connected Mr. C’s father with home health services, including physical therapy for fall risk reduction. Mr. C also hired part-time support to provide additional assistance with ADLs and IADLs, allowing Mr. C to have time to attend to his own needs. Though provided with information about a local caregiver support group, Mr. C chose not to attend. The physician also assisted the family with advanced directives.

A particular challenge that occurred during care for the family was addressing Mr. C’s father’s driving capacity, considering his strong need for independence. To address this concern, a family meeting was held with Mr. C, his father, and his siblings from out of town. Although Mr. C’s father was not willing to relinquish his driver’s license during that meeting, he agreed to complete a functional driving assessment.

The physician continued to meet with Mr. C and his father together, as well as with Mr. C individually, to provide supportive counseling as needed. As the father’s dementia progressed and it became more difficult to complete office appointments, the physician transitioned to home visits to provide care until the father’s death.

After the death of Mr. C’s father, the physician continued to serve as Mr. C’s primary care provider.

Keeping the “family”in family medicine

Through longitudinal assessment, needs identification, and provision of relevant information, emotional support, and resources, family physicians can provide care that can improve the quality of life and well-being and help alleviate burden experienced by dementia caregivers. Family physicians also are positioned to provide treatments that can address the negative physical and psychological health outcomes associated with informal dementia caregiving. By building relationships with multiple family members across generations, family physicians can understand the context of caregiving dynamics and work together with individuals with dementia and their caregivers throughout disease progression, providing consistent support to the family unit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathleen M. Young, PhD, MPH, Novant Health Family Medicine Wilmington, 2523 Delaney Avenue, Wilmington, NC 28403; Kathleen.Young@novanthealth.org

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 202319:1598-1695. doi: 10.1002/alz.13016

2. Liu Z, Heffernan C, Tan J. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. Int J of Nurs Sci. 2020;7:448-435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.012

3. Ory MG, Hoffman RR III, Yee JL, et al. Prevalence and impacts of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist. 1999;39:177-185. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.177

4. Baharudin AD, Din NC, Subramaniam P, et al. The associations between behavioral-psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and coping strategy, burden of care and personality style among low-income caregivers of patients with dementia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(suppl 4):447. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6868-0

5. Cheng S-T. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2

6. Reed C, Belger M, Andrews JS, et al. Factors associated with long-term impact on informal caregivers during Alzheimer’s disease dementia progression: 36-month results from GERAS. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:267-277. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000425

7. Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly MLM, Sullivan MP, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:106. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8

8. Haley WE, Levine EG, Brown SL, et al. Psychological, social, and health consequences of caring for a relative with senile dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:405-411.

9. Bom J, Bakx P, Schut F, et al. The impact of informal caregiving for older adults on the health of various types of caregivers: a systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2019;59:e629-e642. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny137

10. Fonareva I, Oken BS. Physiological and functional consequences of caregiving for relatives with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:725-747. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000039

11. Del-Pino-Casado R, Rodriguez Cardosa M, Lopez-Martinez C, et al. The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217648

12. Del-Pino-Casado R, Priego-Cubero E, Lopez-Martinez C, et al. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;16:e0247143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247143

13. De Souza Alves LC, Quirino Montiero D, Ricarte Bento S, et al. Burnout syndrome in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: a systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2019;13:415-421. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642018dn13-040008

14. Victor CR, Rippon I, Quinn C, et al. The prevalence and predictors of loneliness in caregivers of people with dementia: findings from the IDEAL programme. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:1232-1238. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1753014

15. Sallim AB, Sayampanathan AA, Cuttilan A, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:1034-1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007

16. Unpublished data from the 2015, 2016 2017, 2020, and 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey, analyzed by and provided to the Alzheimer’s Association by the Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Program (AD+HP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

17. Stall NM, Kim SJ, Hardacre KA, et al. Association of informal caregiver distress with health outcomes of community-dwelling dementia care recipients: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;00:1-9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15690

18. Lindeza P, Rodrigues M, Costa J, et al. Impact of dementia on informal care: a systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;bmjspcare-2020-002242. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242

19. Lethin C, Guiteras AR, Zwakhalen S, et al. Psychological well-being over time among informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home. Aging and Ment Health. 2017; 21:1138-1146. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1211621

20. Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregivers Count Too! A Toolkit to Help Practitioners Assess the Needs of Family Caregivers. Family Caregiver Alliance; 2006. Accessed May 16, 2023. www.caregiver.org/uploads/legacy/pdfs/Assessment_Toolkit_20060802.pdf

21. Zarit SH, Zarit JM. Instructions for the Burden Interview. Pennsylvania State University; 1987.

22. University of Wisconsin. Zarit Burden Interview: assessing caregiver burden. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://wai.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1129/2021/11/Zarit-Caregiver-Burden-Assessment-Instruments.pdf

23. Gallagher-Thompson D, Bilbrey AC, Apesoa-Varano EC, et al. Conceptual framework to guide intervention research across the trajectory of dementia caregiving. Gerontologist. 2020;60:S29-S40. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz157

24. Queluz FNFR, Kervin E, Wozney L, et al. Understanding the needs of caregivers of persons with dementia: a scoping review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:35-52. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000243

25. McCabe M, You E, Tatangelo G. Hearing their voice: a systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. Gerontologist. 2016;56:e70-e88. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw07

26. Zwaanswijk M, Peeters JM, van Beek AP, et al. Informal caregivers of people with dementia: problems, needs and support in the initial stage and in subsequent stages of dementia: a questionnaire survey. Open Nurs J. 2013;7:6-13. doi: 10.2174/1874434601307010006

27. Jennings LA, Palimaru A, Corona MG, et al. Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:685-693. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1471-7

28. Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:217-228. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty

29. Rote SM, Angel JL, Moon H, et al. Caregiving across diverse populations: new evidence from the national study of caregiving and Hispanic EPESE. Innovation in Aging. 2019;3:1-11. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz033

30. Alzheimer’s Association. 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease facts and figures. Special report—race, ethnicity, and Alzheimer’s in America. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:70-104. doi: 10.1002/alz.12328

31. Swartz K, Collins LG. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:699-706.

32. Cheng ST, Au A, Losada A, et al. Psychological interventions for dementia caregivers: what we have achieved, what we have learned. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:59. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1045-9

33. Jennings LA, Reuben DB, Everston LC, et al. Unmet needs of caregivers of patients referred to a dementia care program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:282-289. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13251

34. Soong A, Au ST, Kyaw BM, et al. Information needs and information seeking behaviour of people with dementia and their non-professional caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20:61. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1454-y

35. Cheng S-T, Zhang F. A comprehensive meta-review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on nonpharmacological interventions for informal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20:137. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01547-2

36. Wiegelmann H, Speller S, Verhaert LM, et al. Psychosocial interventions to support the mental health of informal caregivers of persons living with dementia—a systematic literature review. BMC Geriatrics. 2021;21:94. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02020-4

37. Nguyen SA, Oughli HA, Lavretsky H. Complementary and integrative medicine for neurocognitive disorders and caregiver health. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2022;24:469-480. doi: 10.1007/s11920-022-01355-y

38. Gibson A, Holmes SD, Fields NL, et al. Providing care for persons with dementia in rural communities: informal caregivers’ perceptions of supports and services. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:630-648. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2019.1636332

39. Leng M, Zhao Y, Xiau H, et al. Internet-based supportive interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19468. doi: 10.2196/19468

40. Ruggiano N, Brown EL, Li J, et al. Rural dementia caregivers and technology. What is the evidence? Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11:216-224. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20180628-04

41. Shuffler J, Lee K, Fields, et al. Challenges experienced by rural informal caregivers of older adults in the United States: a scoping review. J Evid Based Soc Work. Published online 24 February 24, 2023. doi:10.1080/26408066.2023.2183102

42. Hughes MC, Liu Y, Baumbach A. Impact of COVID-19 on the health and well-being of informal caregivers of people with dementia: a rapid systematic review. Gerontol Geriatric Med. 2021;7:1-8. doi: 10.1177/2333721421102164

43. Paplickar A, Rajagopalan J, Alladi S. Care for dementia patients and caregivers amid COVID-19 pandemic. Cereb Circ Cogn Behav. 2022;3:100040. doi: 10.1016/j.cccb.2022.100040

THE CASE

Sam C* is a 68-year-old man who presented to his family physician in a rural health clinic due to concerns about weight loss. Since his visit 8 months prior, Mr. C unintentionally had lost 20 pounds. Upon questioning, Mr. C also reported feeling irritable and having difficulty with sleep and concentration.

A review of systems did not indicate the presence of infection or other medical conditions. In the 6 years since becoming a patient to the practice, he had reported no chronic health concerns, was taking no medications, and had only been to the clinic for his annual check-up appointments. He completed a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and scored 18, indicating moderately severe depression.

Mr. C had established care with his physician when he moved to the area from out of state so that he could be closer to his parents, who were in their mid-80s at the time. Mr. C’s physician also had been the family physician for his parents for the previous 20 years. Three years prior to Mr. C’s presentation for weight loss, his mother had received a diagnosis of acute leukemia; she died a year later.

Over the past year, Mr. C had needed to take a more active role in the care of his father, who was now in his early 90s. Mr. C’s father, who was previously in excellent health, had begun to develop significant health problems, including degenerative arthritis and progressive vascular dementia. He also had ataxia, leading to poor mobility, and a neurogenic bladder requiring self-catheterization, which required Mr. C’s assistance. Mr. C lived next door to his father and provided frequent assistance with activities of daily living. However, his father, who always had been the dominant figure in the family, was determined to maintain his independence and not relinquish control to others.

The strain of caregiving activities, along with managing his father’s inflexibility, was causing increasing distress for Mr. C. As he told his family physician, “I just don’t know what to do.”

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

It is estimated that more than 11 million Americans provided more than 18 billion hours in unpaid support for individuals with dementia in 2022, averaging 30 hours of care per caregiver per week.1 As individuals with dementia progressively decline, they require increased assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs, such as bathing and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs, such as paying bills and using transportation). Most of this assistance comes from informal caregiving provided by family members and friends.

Caregiver burden can be defined as “the strain or load borne by a person who cares for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member.”2 Caregiver stress has been found to be higher for dementia caregiving than other types of caregiving.3 In particular, caring for someone with greater behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSDs) has been associated with higher caregiver burden.4-

Beyond the subjective burden of caregiving, there are other potential negative consequences for dementia caregivers (see TABLE 18-14 and TABLE 215,16). In addition, caregiver distress is related to a number of care recipient outcomes, including earlier institutionalization, more hospitalizations, more BPSDs, poorer quality of life, and greater likelihood of experiencing elder abuse.17

Assessment, reassessment are key to meeting needs

Numerous factors can foster caregiver well-being, including feelings of accomplishment and contribution, a strengthening of the relationship with the care recipient, and feeling supported by friends, family, and formal care systems.18,19 Family physicians can play an important role by assessing and supporting patients with dementia and their caregivers. Ideally, the individual with dementia and the caregiver will be assessed both together and separately.

A thorough assessment includes gathering information about the context and quality of the caregiving relationship; caregiver perception of the care recipient’s health and functional status; caregiver values and preferences; caregiver well-being (including mental health assessment); caregiver skills, abilities, and knowledge about caregiving; and positive and negative consequences of caregiving.20 Caregiver needs—including informational, care support, emotional, physical, and social needs—also should be assessed.

Continue to: Tools are available...

Tools are available to facilitate caregiver assessment. For example, the Zarit Burden Interview is a 22-item self-report measure that can be given to the caregiver21; shorter versions (4 and 12 items) are also available.22 Another resource available for caregiver assessment guidance is a toolkit developed by the Family Caregiver Alliance.20

Continually assess for changing needs

As the condition of the individual with dementia progresses, it will be important to reassess the caregiver, as stressors and needs will change over the course of the caregiving relationship. Support should be adapted accordingly.

In the early stage of dementia, caregivers may need information on disease progression and dementia care planning, ways to navigate the health care system, financial planning, and useful resources. Caregivers also may need emotional support to help them adapt to the role of caregiver, deal with denial, and manage their stress.23,24

With dementia progression, caregivers may need support related to increased decision-making responsibility, managing challenging behaviors, assisting with ADLs and IADLs, and identifying opportunities to meet personal social and well-being needs. They also may need support to accept the changes they are seeing in the individual with dementia and the shifts they are experiencing in their relationship with him or her.23,25

In late-stage dementia, caregiver needs tend to shift to determining the need for long-term care placement vs staying at home, end-of-life planning, loneliness, and anticipatory grief.23,26 Support with managing changing and accumulating stress typically remains a primary need throughout the progression of dementia.27

Continue to: Specific populations have distinct needs

Specific populations have distinct needs. Some caregivers, including members of the LGBTQ+ community and different racial and ethnic groups, as well as caregivers of people with younger-onset dementia, may have additional support needs.28

For example, African American and Latino caregivers tend to have caregiving relationships of longer duration, requiring more time-intensive care, but use fewer formal support services than White caregivers.29 Caregivers from non-White racial and ethnic groups also are more likely to experience discrimination when interacting with health care services on behalf of care recipients.30

Having an awareness of potential specialized needs may help to prevent or address potential care disparities, and cultural humility may help to improve caregiver experiences with primary care physicians.

Resources to support caregivers

Family physicians are well situated to provide informational and emotional support for both patients with dementia and their informal care providers.31 Given the variability of caregiver concerns, multicomponent interventions addressing informational, self-care, social support, and financial needs often are needed.31 Supportive counseling and psychoeducation can help dementia caregivers with stress management, self-care, coping, and skills training—supporting the development of self-efficacy.32,33

Outside resources. Although significant caregiver support can be provided directly by the physician, caregivers should be connected with outside resources, including support groups, counselors, psychotherapists, financial and legal support, and formal care services

Continue to: Psychosocial and complementary interventions

Psychosocial and complementary interventions. Various psychosocial interventions (eg, psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, support groups) have been found to be beneficial in alleviating caregiver symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and improving well-being, perceived burden, and quality of life. However, systematic reviews have found variability in the degree of helpfulness of these interventions.35,36

Some caregivers and care recipients may benefit from complementary and integrative medicine referrals. Mind–body therapies such as mindfulness, yoga, and Tai Chi have shown some beneficial effects.37

Online resources. Caregivers also can be directed to online resources from organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org), the National Institutes of Health (www.alzheimers.gov), and the Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org).

In rural settings, such as the one in which this case took place, online resources may decrease some barriers to supporting caregivers.38 Internet-based interventions also have been found to have some benefit for dementia caregivers.31,39

However, some rural locations continue to have limited reliable Internet services.40 In affected areas, a strong relationship with a primary care physician may be even more important to the well-being of caregivers, since other support services may be less accessible.41

Continue to: Impacts of the pandemic

Impacts of the pandemic. Although our case took place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to acknowledge ways the pandemic has impacted informal dementia caregiving.

Caregiver stress, depression, and anxiety increased during the pandemic, and the need for greater home confinement and social distancing amplified the negative impact of social isolation, including loneliness, on caregivers.42,43 Caregivers often needed to increase their caregiving responsibilities and had more difficulty with care coordination due to limited access to in-person resources.43 The pandemic led to increased reliance on technology and telehealth in the support of dementia caregivers.43

THE CASE

The physician prescribed mirtazapine for Mr. C, titrating the dose as needed to address depressive symptoms and promote weight gain. The physician connected Mr. C’s father with home health services, including physical therapy for fall risk reduction. Mr. C also hired part-time support to provide additional assistance with ADLs and IADLs, allowing Mr. C to have time to attend to his own needs. Though provided with information about a local caregiver support group, Mr. C chose not to attend. The physician also assisted the family with advanced directives.

A particular challenge that occurred during care for the family was addressing Mr. C’s father’s driving capacity, considering his strong need for independence. To address this concern, a family meeting was held with Mr. C, his father, and his siblings from out of town. Although Mr. C’s father was not willing to relinquish his driver’s license during that meeting, he agreed to complete a functional driving assessment.

The physician continued to meet with Mr. C and his father together, as well as with Mr. C individually, to provide supportive counseling as needed. As the father’s dementia progressed and it became more difficult to complete office appointments, the physician transitioned to home visits to provide care until the father’s death.

After the death of Mr. C’s father, the physician continued to serve as Mr. C’s primary care provider.

Keeping the “family”in family medicine

Through longitudinal assessment, needs identification, and provision of relevant information, emotional support, and resources, family physicians can provide care that can improve the quality of life and well-being and help alleviate burden experienced by dementia caregivers. Family physicians also are positioned to provide treatments that can address the negative physical and psychological health outcomes associated with informal dementia caregiving. By building relationships with multiple family members across generations, family physicians can understand the context of caregiving dynamics and work together with individuals with dementia and their caregivers throughout disease progression, providing consistent support to the family unit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathleen M. Young, PhD, MPH, Novant Health Family Medicine Wilmington, 2523 Delaney Avenue, Wilmington, NC 28403; Kathleen.Young@novanthealth.org

THE CASE

Sam C* is a 68-year-old man who presented to his family physician in a rural health clinic due to concerns about weight loss. Since his visit 8 months prior, Mr. C unintentionally had lost 20 pounds. Upon questioning, Mr. C also reported feeling irritable and having difficulty with sleep and concentration.

A review of systems did not indicate the presence of infection or other medical conditions. In the 6 years since becoming a patient to the practice, he had reported no chronic health concerns, was taking no medications, and had only been to the clinic for his annual check-up appointments. He completed a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and scored 18, indicating moderately severe depression.

Mr. C had established care with his physician when he moved to the area from out of state so that he could be closer to his parents, who were in their mid-80s at the time. Mr. C’s physician also had been the family physician for his parents for the previous 20 years. Three years prior to Mr. C’s presentation for weight loss, his mother had received a diagnosis of acute leukemia; she died a year later.

Over the past year, Mr. C had needed to take a more active role in the care of his father, who was now in his early 90s. Mr. C’s father, who was previously in excellent health, had begun to develop significant health problems, including degenerative arthritis and progressive vascular dementia. He also had ataxia, leading to poor mobility, and a neurogenic bladder requiring self-catheterization, which required Mr. C’s assistance. Mr. C lived next door to his father and provided frequent assistance with activities of daily living. However, his father, who always had been the dominant figure in the family, was determined to maintain his independence and not relinquish control to others.

The strain of caregiving activities, along with managing his father’s inflexibility, was causing increasing distress for Mr. C. As he told his family physician, “I just don’t know what to do.”

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

It is estimated that more than 11 million Americans provided more than 18 billion hours in unpaid support for individuals with dementia in 2022, averaging 30 hours of care per caregiver per week.1 As individuals with dementia progressively decline, they require increased assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs, such as bathing and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs, such as paying bills and using transportation). Most of this assistance comes from informal caregiving provided by family members and friends.

Caregiver burden can be defined as “the strain or load borne by a person who cares for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member.”2 Caregiver stress has been found to be higher for dementia caregiving than other types of caregiving.3 In particular, caring for someone with greater behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSDs) has been associated with higher caregiver burden.4-

Beyond the subjective burden of caregiving, there are other potential negative consequences for dementia caregivers (see TABLE 18-14 and TABLE 215,16). In addition, caregiver distress is related to a number of care recipient outcomes, including earlier institutionalization, more hospitalizations, more BPSDs, poorer quality of life, and greater likelihood of experiencing elder abuse.17

Assessment, reassessment are key to meeting needs