User login

Tips and tools to help you manage ADHD in children, adolescents

THE CASE

James B* is a 7-year-old Black child who presented to his primary care physician (PCP) for a well-child visit. During preventive health screening, James’ mother expressed concerns about his behavior, characterizing him as immature, aggressive, destructive, and occasionally self-loathing. She described him as physically uncoordinated, struggling to keep up with his peers in sports, and tiring after 20 minutes of activity. James slept 10 hours nightly but was often restless and snored intermittently. As a second grader, his academic achievement was not progressing, and he had become increasingly inattentive at home and at school. James’ mother offered several examples of his fighting with his siblings, noncompliance with morning routines, and avoidance of learning activities. Additionally, his mother expressed concern that James, as a Black child, might eventually be unfairly labeled as a problem child by his teachers or held back a grade level in school.

Although James did not have a family history of developmental delays or learning disorders, he had not met any milestones on time for gross or fine motor, language, cognitive, and social-emotional skills. James had a history of chronic otitis media, for which pressure equalizer tubes were inserted at age 2 years. He had not had any major physical injuries, psychological trauma, recent life transitions, or adverse childhood events. When asked, James’ mother acknowledged symptoms of maternal depression but alluded to faith-based reasons for not seeking treatment for herself.

James’ physical examination was unremarkable. His height, weight, and vitals were all within normal limits. However, he had some difficulty with verbal articulation and expression and showed signs of a possible vocal tic. Based on James’ presentation, his PCP suspected attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as neurodevelopmental delays.

The PCP gave James’ mother the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire to complete and the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for her and James’ teacher to fill out independently and return to the clinic. The PCP also instructed James’ mother on how to use a sleep diary to maintain a 1-month log of his sleep patterns and habits. The PCP consulted the integrated behavioral health clinician (IBHC; a clinical social worker embedded in the primary care clinic) and made a warm handoff for the IBHC to further assess James’ maladaptive behaviors and interactions.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

James is one of more than 6 million children, ages 3 to 17 years, in the United States who live with ADHD.1,2 ADHD is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder among children, and it affects multiple cognitive and behavioral domains throughout the lifespan.3 Children with ADHD often initially present in primary care settings; thus, PCPs are well positioned to diagnose the disorder and provide longitudinal treatment. This Behavioral Health Consult reviews clinical assessment and practice guidelines, as well as treatment recommendations applicable across different areas of influence—individual, family, community, and systems—for PCPs and IBHCs to use in managing ADHD in children.

ADHD features can vary by age and sex

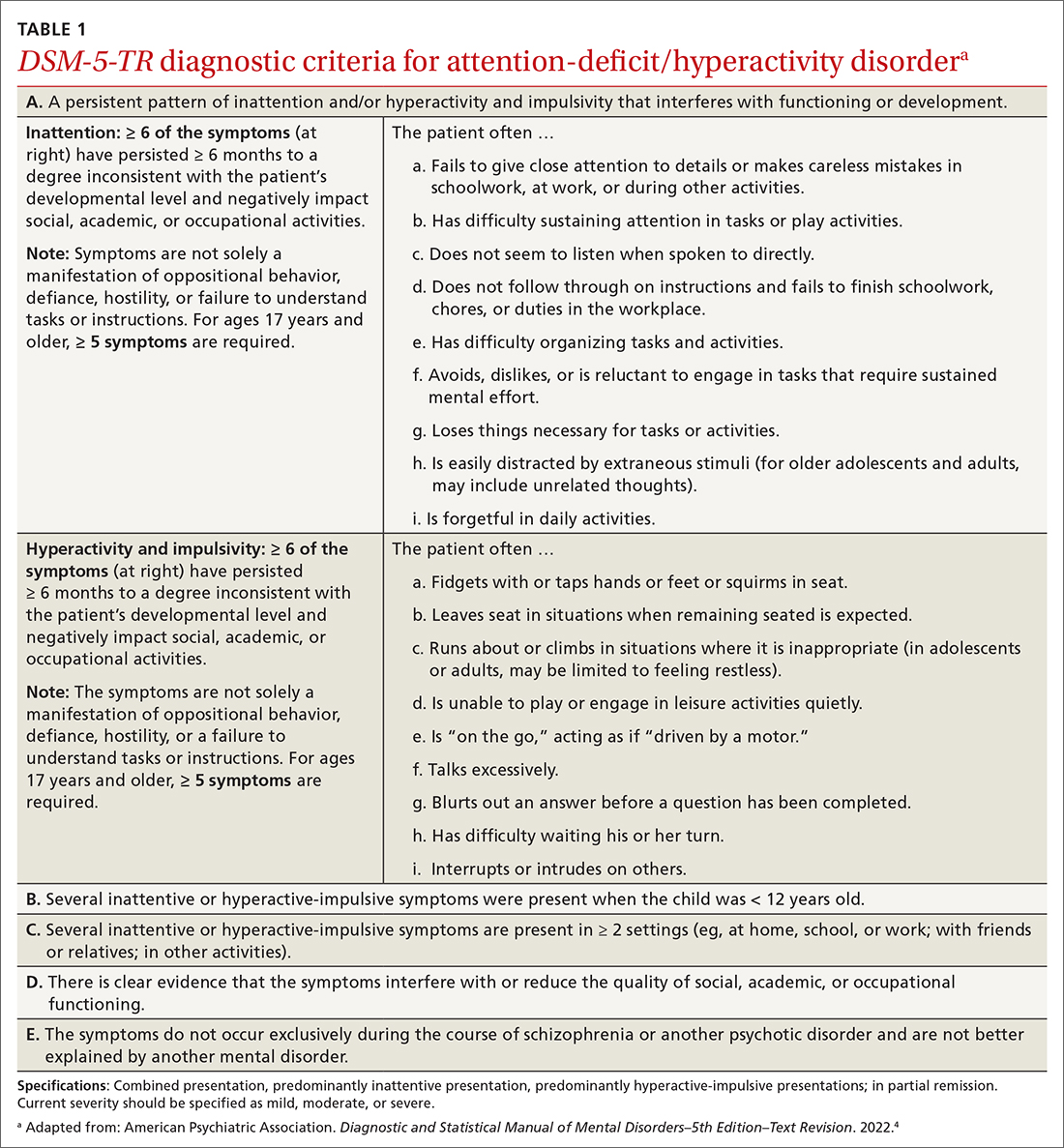

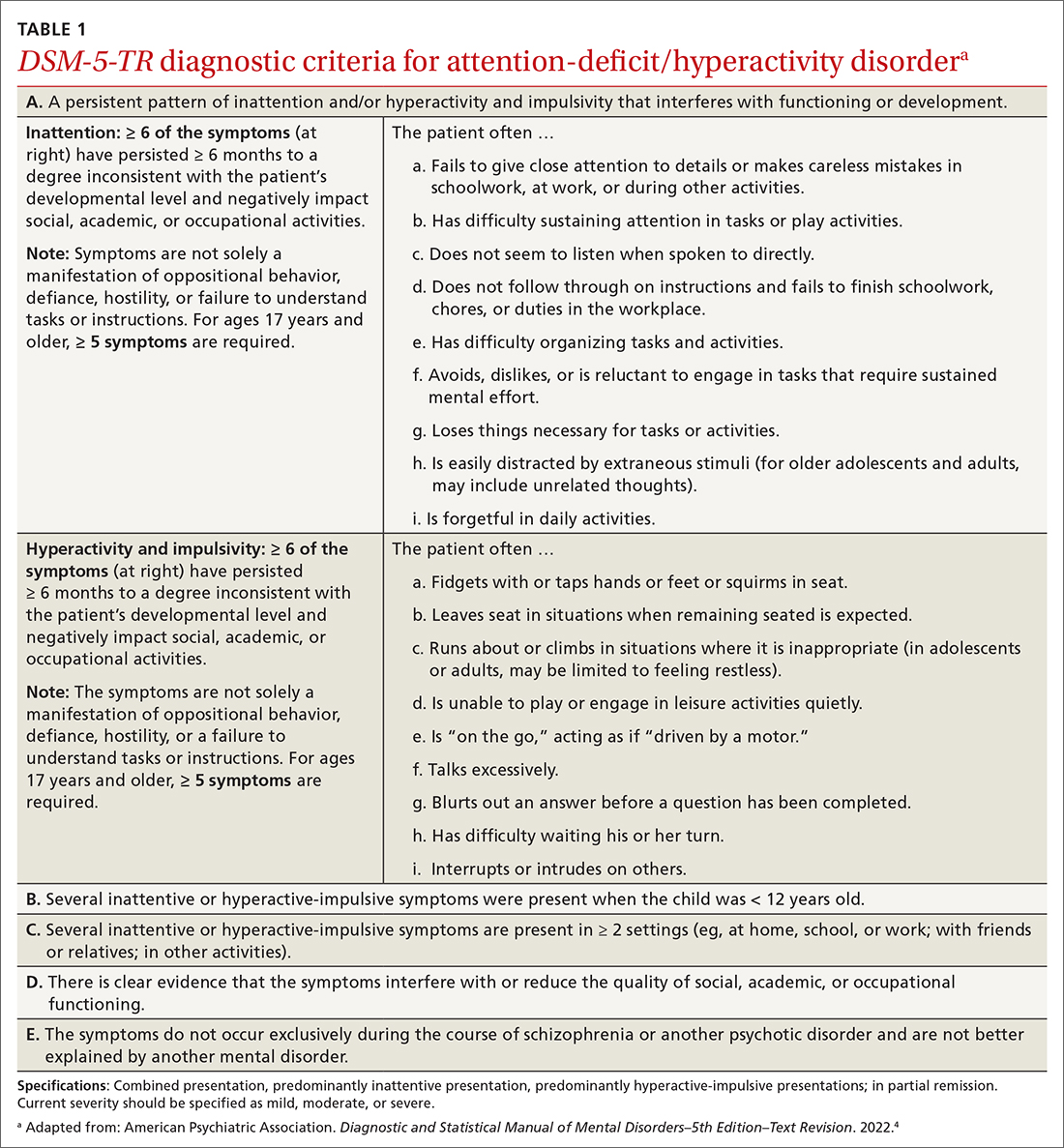

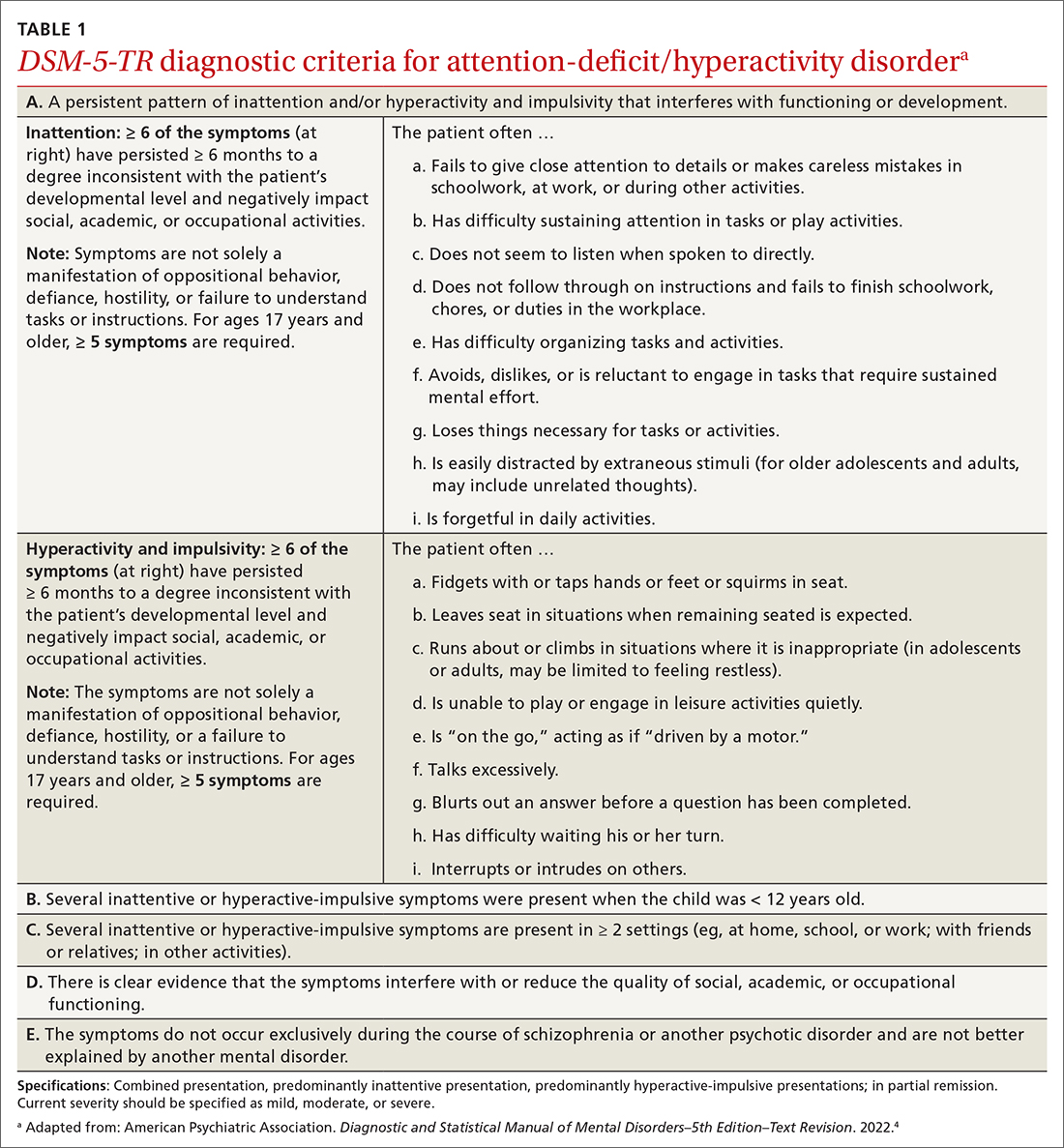

ADHD is a persistent pattern of inattention or hyperactivity and impulsivity interfering with functioning or development in childhood and functioning later in adulthood. ADHD symptoms manifest prior to age 12 years and must occur in 2 or more settings.4 Symptoms should not be better explained by another psychiatric disorder or occur exclusively during the course of another disorder (TABLE 1).4

The rate of heritability is high, with significant incidence among first-degree relatives.4 Children with ADHD show executive functioning deficits in 1 or more cognitive domains (eg, visuospatial, memory, inhibitions, decision making, and reward regulation).4,5 The prevalence of ADHD nationally is approximately 9.8% (2.2%, ages 3-5 years; 10%, ages 6-11 years; 13.2%, ages 12-17 years) in children and adolescents; worldwide prevalence is 7.2%.1,6 It persists among 2.6% to 6.8% of adults worldwide.7

Research has shown that boys ages 6 to 11 years are significantly more likely than girls to exhibit attention-getting, externalizing behaviors or conduct problems (eg, hyperactivity, impulsivity, disruption, aggression).1,6 On the other hand, girls ages 12 to 17 years tend to display internalized (eg, depressed mood, anxiety, low self-esteem) or inattentive behaviors, which clinicians and educators may assess as less severe and warranting fewer supportive measures.1

The prevalence of ADHD and its associated factors, which evolve through maturation, underscore the importance of persistent, patient-centered, and collaborative PCP and IBHC clinical management.

Continue to: Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

When caregivers express concerns about their child’s behavior, focus, mood, learning, and socialization, consider initiating a multimodal evaluation for ADHD.5,8 Embarking on an ADHD assessment can require extended or multiple visits to arrive at the diagnosis, followed by still more visits to confirm a course of care and adjust medications. The integrative care approach described in the patient case and elaborated on later in this article can help facilitate assessment and treatment of ADHD.9

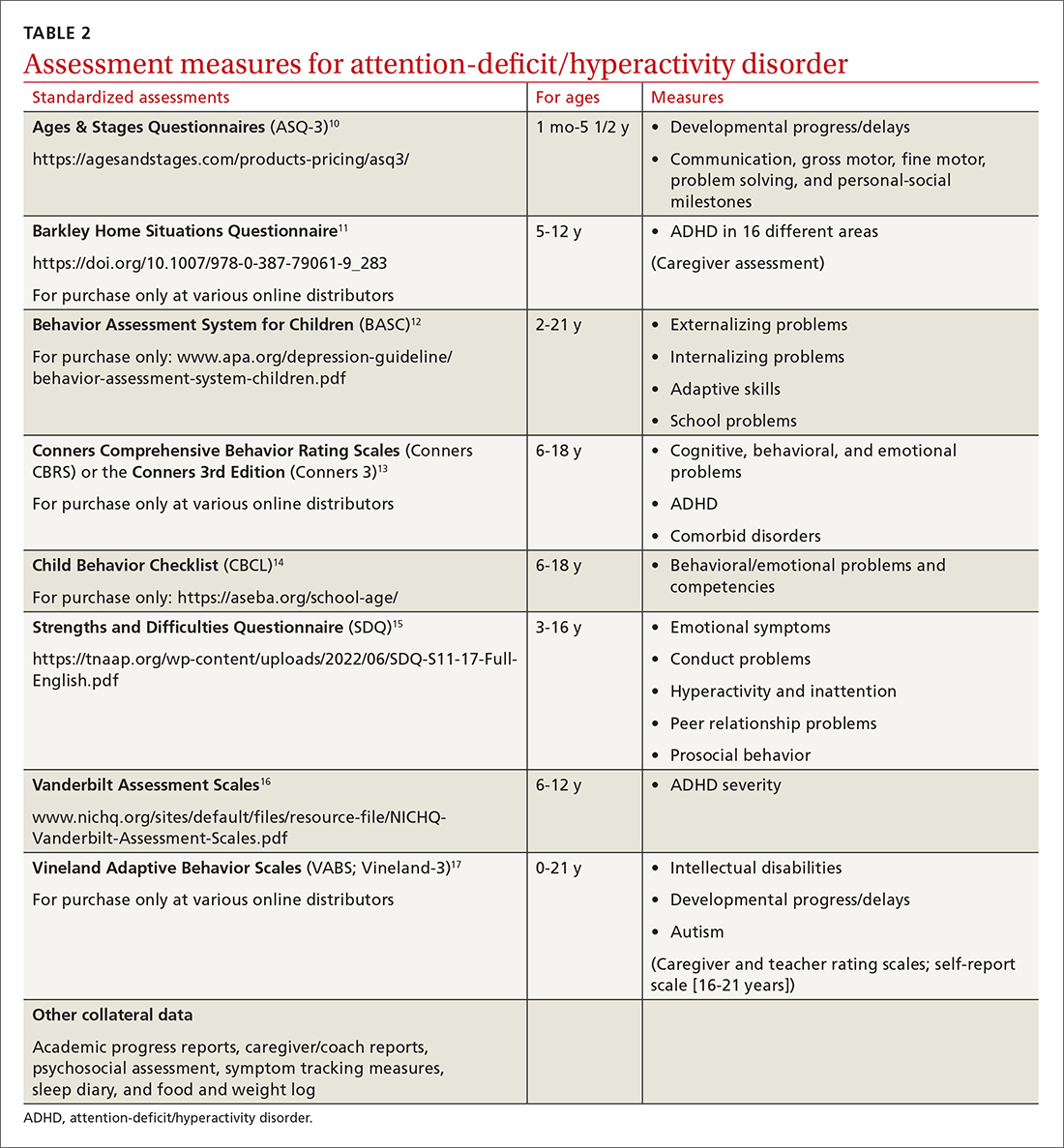

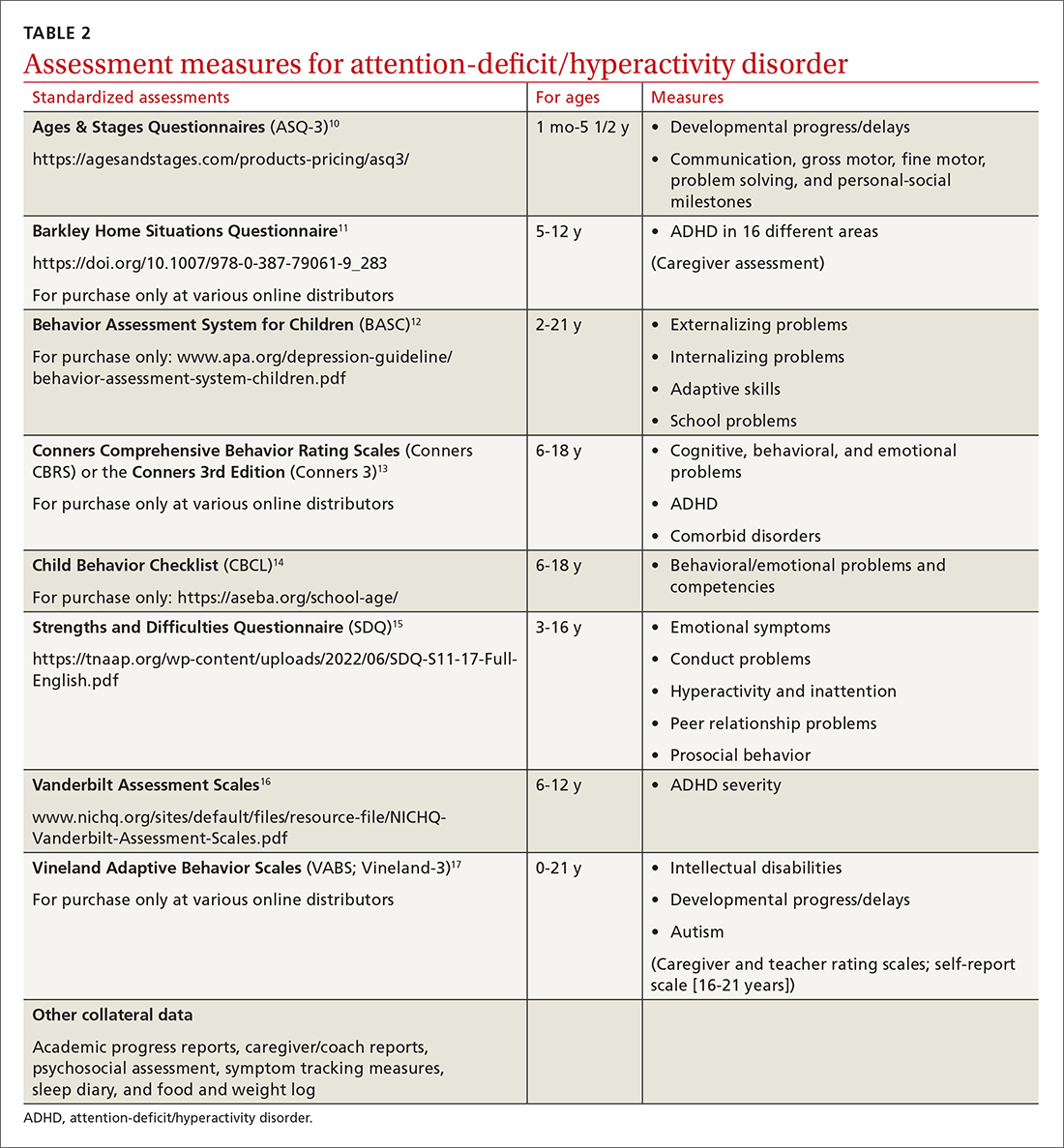

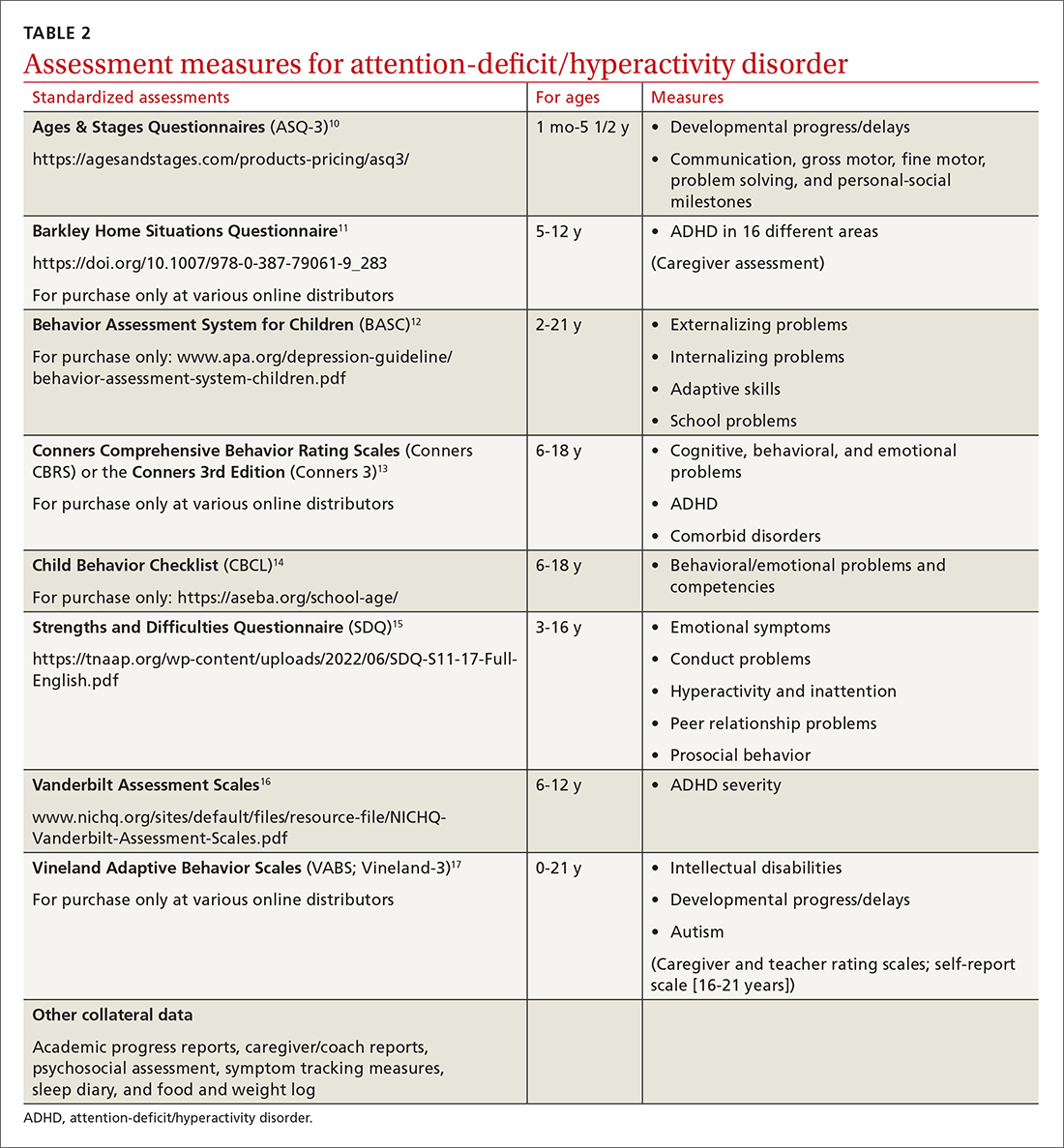

Signs of ADHD may be observed at initial screening using a tool such as the Ages & Stages Questionnaire (https://agesandstages.com/products-pricing/asq3/) to reveal indications of norm deviations or delays commensurate with ADHD.10 However, to substantiate the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision criteria for an accurate diagnosis,4 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines require a thorough clinical interview, administration of a standardized assessment tool, and review of objective reports in conjunction with a physical examination and psychosocial evaluation.6 Standardized measures of psychological, neurocognitive, and academic achievement reported by caregivers and collateral contacts (eg, teachers, counselors, coaches, care providers) are needed to maximize data objectivity and symptom accuracy across settings (TABLE 210-17). Additionally, periodic reassessment is recommended to validate changes in diagnostic subtype and treatment plans due to the chronic and dynamic nature of ADHD.

Consider comorbidities and alternate diagnoses

The diagnostic possibility of ADHD should also prompt consideration of other childhood disorders due to the high potential for comorbidities.4,6 In a 2016 study, approximately 64% of

Various medical disorders may manifest with similar signs or symptoms to ADHD, such as thyroid disorders, seizure disorders, adverse drug effects, anemia, genetic anomalies, and others.6,19

If there are behavioral concerns or developmental delays associated with tall stature for age or pubertal or testicular development anomalies, consult a geneticist and a developmental pediatrician for targeted testing and neurodevelopmental assessment, respectively. For example, ADHD is a common comorbidity among boys who also have XYY syndrome (Jacobs syndrome). However, due to the variability of symptoms and severity, XYY syndrome often goes undiagnosed, leaving a host of compounding pervasive and developmental problems untreated. Overall, more than two-thirds of patients with ADHD and a co-occurring condition are either inaccurately diagnosed or not referred for additional assessment and adjunct treatment.21

Continue to: Risks that arise over time

Risks that arise over time. As ADHD persists, adolescents are at greater risk for psychiatric comorbidities, suicidality, and functional impairments (eg, risky behaviors, occupational problems, truancy, delinquency, and poor self-esteem).4,8 Adolescents with internalized behaviors are more likely to experience comorbid depressive disorders with increased risk for self-harm.4,5,8 As adolescents age and their sense of autonomy increases, there is a tendency among those who have received a diagnosis of ADHD to minimize symptoms and decrease the frequency of routine clinic visits along with medication use and treatment compliance.3 Additionally, abuse, misuse, and misappropriation of stimulants among teens and young adults are commonplace.

Wide-scope, multidisciplinary evaluation and close clinical management reduce the potential for imprecise diagnoses, particularly at critical developmental junctures. AAP suggests that PCPs can treat mild and moderate cases of ADHD, but if the treating clinician does not have adequate training, experience, time, or clinical support to manage this condition, early referral is warranted.6

A guide to pharmacotherapy

Approximately 77% of children ages 2 to 17 years with a diagnosis of ADHD receive any form of treatment.2 Treatment for ADHD can include behavioral therapy and medication.2 AAP clinical practice guidelines caution against prescribing medications for children younger than 6 years, relying instead on caregiver-, teacher-, or clinician-administered behavioral strategies and parental training in behavioral modification. For children and adolescents between ages 6 and 18 years, first-line treatment includes pharmacotherapy balanced with behavioral therapy, academic modifications, and educational supports (eg, 504 Plan, individualized education plan [IEP]).6

Psychostimulants are preferred. These agents (eg, methylphenidate, amphetamine) remain the most efficacious class of medications to reduce hyperactivity and inattentiveness and to improve function. While long-acting psychostimulants are associated with better medication adherence and adverse-effect tolerance than are short-acting forms, the latter offer more flexibility in dosing. Start by titrating any stimulant to the lowest effective dose; reassess monthly until potential rebound effects stabilize.

Due to potential adverse effects of this class of medication, screen for any family history or personal risk for structural or electrical cardiac anomalies before starting pharmacotherapy. If any such risks exist, arrange for further cardiac evaluation before initiating medication.6 Adverse effects of stimulants include reduced appetite, gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, anxiousness, parasomnia, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Continue to: Once medication is stabilized...

Once medication is stabilized, monitor treatment 2 to 3 times per year thereafter; watch for longer-term adverse effects such as weight loss, decreased growth rate, and psychiatric comorbidities including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s black box warning of increased risk for suicidality.5,6,22

Other options. The optimal duration of psychostimulant use remains debatable, as existing evidence does not support its long-term use (10 years) over other interventions, such as nonstimulants and nonmedicinal therapies.22 Although backed by less evidence, additional medications indicated for the treatment of ADHD include: (1) atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and (2) the selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, extended-release guanfacine and extended-release clonidine (third-line agent).22

Adverse effects of these FDA-approved medications are similar to those observed in stimulant medications. Evaluation of cardiac risks is recommended before starting nonstimulant medications. The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists may also be used as adjunct therapies to stimulants. Before stopping an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, taper the dosage slowly to avoid the risk for rebound hypertension.6,23 Given the wide variety of medication options and variability of effects, it may be necessary to try different medications as children grow and their symptoms and capacity to manage them change. Additional guidance on FDA-approved medications is available at www.ADHDMedicationGuide.com.

How multilevel care coordination can work

As with other chronic or developmental conditions, the treatment of ADHD requires an interdisciplinary perspective. Continuous, comprehensive case management can help patients overcome obstacles to wellness by balancing the resolution of problems with the development of resilience. Well-documented collaboration of subspecialists, educators, and other stakeholders engaged in ADHD care at multiple levels (individual, family, community, and health care system) increases the likelihood of meaningful, sustainable gains. Using a patient-centered medical home framework, IBHCs or other allied health professionals embedded in, or co-located with, primary care settings can be key to accessing evidence-based treatments that include: psycho-education and mindfulness-based stress reduction training for caregivers24,25; occupational,26 cognitive behavioral,27 or family therapies28,29; neuro-feedback; computer-based attention training; group- or community-based interventions; and academic and social supports.5,8

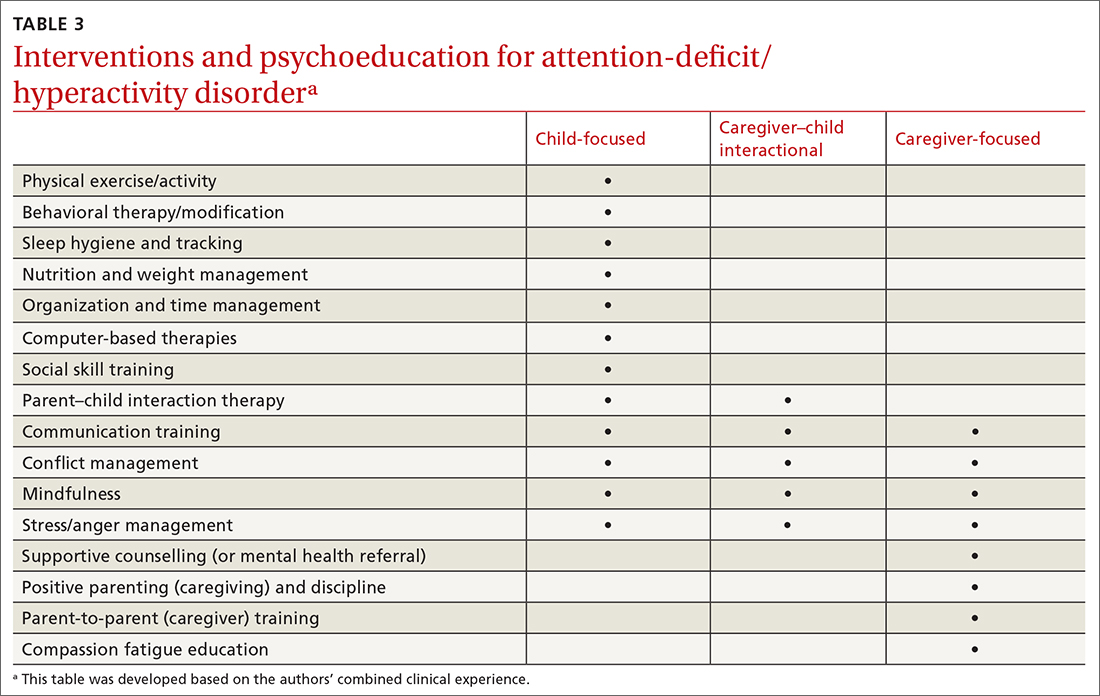

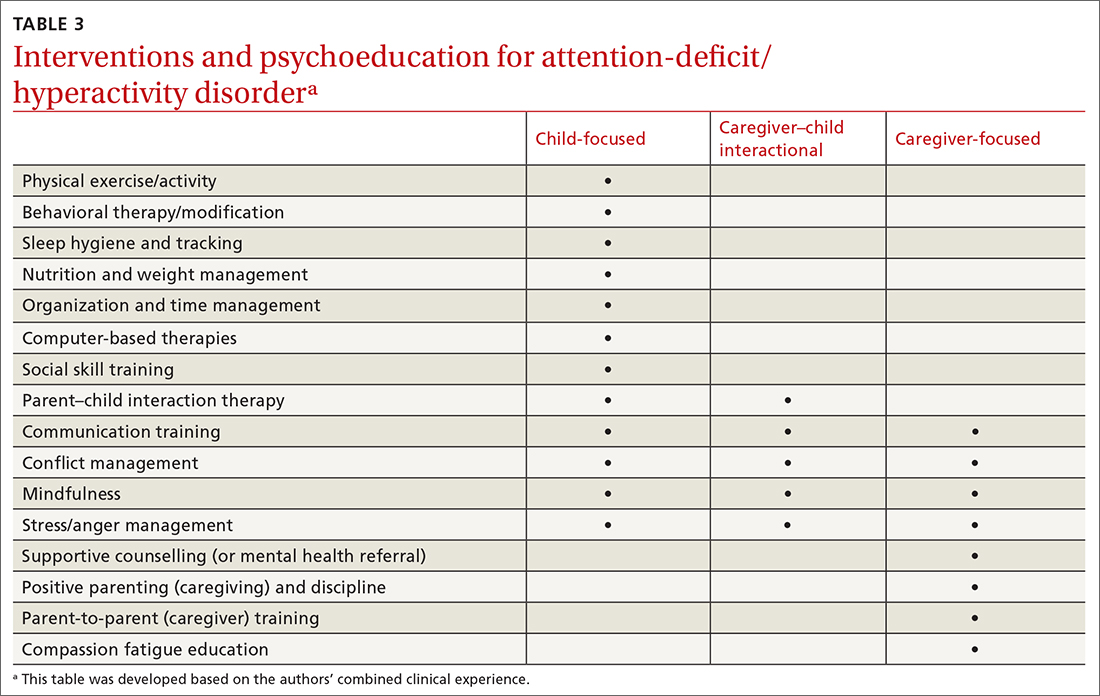

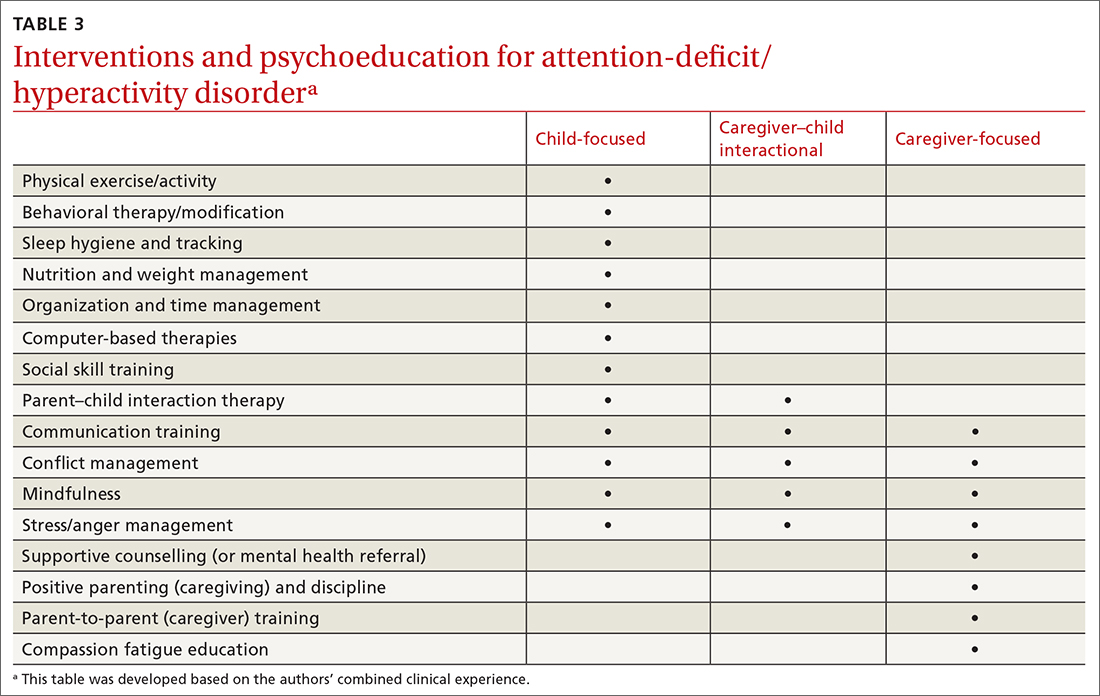

Treatment approaches that capitalize on children’s neurologic and psychological plasticity and fortify self-efficacy with developmentally appropriate tools empower them to surmount ADHD symptoms over time.23 Facilitating children’s resilience within a developmental framework and health system’s capacities with socio-culturally relevant approaches, consultation, and research can optimize outcomes and mitigate pervasiveness into adulthood. While the patient is at the center of treatment, it is important to consider the family, school, and communities in which the child lives, learns, and plays. PCPs and IBHCs together can consider a “try and track” method to follow progress, changes, and outcomes over time. With this method, the physician can employ approaches that focus on the patient, caregiver, or the caregiver–child interaction (TABLE 3).

Continue to: Assess patients' needs and the resources available

Assess patients’ needs and the resources available throughout the system of care beyond the primary care setting. Stay abreast of hospital policies, health care insurance coverage, and community- and school-based health programs, and any gaps in adequate and equitable assessment and treatment. For example, while clinical recommendations include psychiatric care, health insurance availability or limits in coverage may dissuade caregivers from seeking help or limit initial or long-term access to resources for help.30 Integrating or advocating for clinic support resources or staffing to assist patients in navigating and mitigating challenges may lessen the management burden and increase the likelihood and longevity of favorable health outcomes.

Steps to ensuring health care equity

Among children of historically marginalized and racial and ethnic minority groups or those of populations affected by health disparities, ADHD symptoms and needs are often masked by structural biases that lead to inequitable care and outcomes, as well as treatment misprioritization or delays.31 In particular, evidence has shown that recognition and diagnostic specificity of ADHD and comorbidities, not prevalence, vary more widely among minority than among nonminority populations,32 contributing to the 23% of children with ADHD who receive no treatment at all.2

Understand caregiver concerns. This diagnosis discrepancy is correlated with symptom rating sensitivities (eg, reliability, perception, accuracy) among informants and how caregivers observe, perceive, appreciate, understand, and report behaviors. This discrepancy is also related to cultural belief differences, physician–patient communication variants, and a litany of other socioeconomic determinants.2,4,31 Caregivers from some cultural, ethnic, or socioeconomic backgrounds may be doubtful of psychiatric assessment, diagnoses, treatment, or medication, and that can impact how children are engaged in clinical and educational settings from the outset.31 In the case we described, James’ mother was initially hesitant to explore psychotropic medications and was concerned about stigmatization within the school system. She also seemed to avoid psychiatric treatment for her own depressive symptoms due to cultural and religious beliefs.

Health care provider concerns. Some PCPs may hesitate to explore medications due to limited knowledge and skill in dosing and titrating based on a child’s age, stage, and symptoms, and a perceived lack of competence in managing ADHD. This, too, can indirectly perpetuate existing health disparities. Furthermore, ADHD symptoms may be deemed a secondary or tertiary concern if other complex or urgent medical or undifferentiated developmental problems manifest.

Compounding matters is the limited dissemination of empiric research articles (including randomized controlled trials with representative samples) and limited education on the effectiveness and safety of psychopharmacologic interventions across the lifespan and different cultural and ethnic groups.4 Consequently, patients who struggle with unmanaged ADHD symptoms are more likely to have chronic mental health disorders, maladaptive behaviors, and other co-occurring conditions contributing to the complexity of individual needs, health care burdens, or justice system involvement; this is particularly true for those of racial and ethnic minorities.33

Continue to: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients—particularly those in minority or health disparity populations—who under normal circumstances might have been hesitant to seek help may have felt even more reluctant to do so during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have not yet learned the degree to which limited availability of preventive health care services, decreased routine visits, and fluctuating insurance coverage has impacted the diagnosis, management, or severity of childhood disorders during the past 2 years. Reports of national findings indicate that prolonged periods out of school and reduced daily structure were associated with increased disruptions in mood, sleep, and appetite, particularly among children with pre-existing pathologies. Evidence suggests that school-aged children experienced more anxiety, regressive behaviors, and parasomnias than they did before the pandemic, while adolescents experienced more isolation and depressive symptoms.34,35

However, there remains a paucity of large-scale or representative studies that use an intersectional lens to examine the influence of COVID-19 on children with ADHD. Therefore, PCPs and IBHCs should refocus attention on possibly undiagnosed, stagnated, or regressed ADHD cases, as well as the adults who care for them. (See “5 ways to overcome Tx barriers and promote health equity.”)

SIDEBAR

5 ways to overcome Tx barriers and promote health equitya

1. Inquire about cultural or ethnic beliefs and behaviors and socioeconomic barriers.

2. Establish trust or assuage mistrust by exploring and dispelling misinformation.

3. Offer accessible, feasible, and sustainable evidence-based interventions.

4. Encourage autonomy and selfdetermination throughout the health care process.

5. Connect caregivers and children with clinical, community, and school-based resources and coordinators.

a These recommendations are based on the authors’ combined clinical experience.

THE CASE

During a follow-up visit 1 month later, the PCP confirmed the clinical impression of ADHD combined presentation with a clinical interview and review of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire completed by James’ mother and the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales completed by James’ mother and teacher. The sleep diary indicated potential problems and apneas worthy of consults for pulmonary function testing, a sleep study, and otolaryngology examination. The PCP informed James’ mother on sleep hygiene strategies and ADHD medication options. She indicated that she wanted to pursue the referrals and behavioral modifications before starting any medication trial.

The PCP referred James to a developmental pediatrician for in-depth assessment of his overall development, learning, and functioning. The developmental pediatrician ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of ADHD, as well as motor and speech delays warranting physical, occupational, and speech therapies. The developmental pediatrician also referred James for targeted genetic testing because she suspected a genetic disorder (eg, XYY syndrome).

The PCP reconnected James and his mother to the IBHC to facilitate subspecialty and school-based care coordination and to provide in-office and home-based interventions. The IBHC assessed James’ emotional dysregulation and impulsivity as adversely impacting his interpersonal relationships and planned to address these issues with behavioral and parent–child interaction therapies and skills training during the course of 6 to 12 visits. James’ mother was encouraged to engage his teacher on his academic performance and to initiate a 504 Plan or IEP for in-school accommodations and support. The IBHC aided in tracking his assessments, referrals, follow-ups, access barriers, and treatment goals.

After 6 months, James had made only modest progress, and his mother requested that he begin a trial of medication. Based on his weight, symptoms, behavior patterns, and sleep habits, the PCP prescribed extended-release dexmethylphenidate 10 mg each morning, then extended-release clonidine 0.1 mg nightly. With team-based clinical management of pharmacologic, behavioral, physical, speech, and occupational therapies, James’ behavior and sleep improved, and the signs of a vocal tic diminished.

By the next school year, James demonstrated a marked improvement in impulse control, attention, and academic functioning. He followed up with the PCP at least quarterly for reassessment of his symptoms, growth, and experience of adverse effects, and to titrate medications accordingly. James and his mother continued to work closely with the IBHC monthly to engage interventions and to monitor his progress at home and school.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sundania J. W. Wonnum, PhD, LCSW, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, 6707 Democracy Boulevard, Suite 800, Bethesda, MD 20892; sundania.wonnum@nih.gov

1. Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, et al. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Suppl. 2022;71:1-42. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

2. Danielson ML, Holbrook JR, Blumberg SJ, et al. State-level estimates of the prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016 to 2019. J Atten Disord. 2022;26:1685-1697. doi: 10.1177/10870547221099961

3. Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, et al. The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:789-818. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022

4. American Psychiatric Association

5. Brahmbhatt K, Hilty DM, Mina H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during adolescence in the primary care setting: a concise review. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:135-143. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.025

6. Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, et al. AAP Subcommittee on Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20192528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2528

7. Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04009. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.04009

8. Chang JG, Cimino FM, Gossa W. ADHD in children: common questions and answers. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:592-602.

9. Asarnow JR, Rozenman M, Wiblin J, et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:929-937. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1141

10. Squires J, Bricker D. Ages & Stages Questionnaires®. 3rd ed (ASQ®-3). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc; 2009.

11. DuPaul GJ, Barkley RA. Situational variability of attention problems: psychometric properties of the Revised Home and School Situations Questionnaires. J Clin Child Psychol. 1992;21:178-188. doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2102_10

12. Merenda PF. BASC: behavior assessment system for children. Meas Eval Counsel Develop. 1996;28:229-232.

13. Conners CK. Conners, 3rd ed manual. Multi-Health Systems. 2008.

14. Achenbach TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments. In: Maruish ME, ed. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999:429-466.

15. Goodman R. The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:791-799.

16. Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale in a referred population. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:559-567. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046

17. Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. In: Newmark CS, ed. Major Psychological Assessment Instruments. Vol 2. Allyn & Bacon; 2003:199-231.

18. Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47:199-212. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860

19. Ghriwati NA, Langberg JM, Gardner W, et al. Impact of mental health comorbidities on the community-based pediatric treatment and outcomes of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Ped. 2017;38:20-28. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000359

20. Niclasen J, Obel C, Homøe P, et al. Associations between otitis media and child behavioural and learning difficulties: results from a Danish Cohort. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;84:12-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.02.017

21. Ross JL Roeltgen DP Kushner H, et al. Behavioral and social phenotypes in boys with 47,XYY syndrome or 47,XXY Klinefelter syndrome. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0719

22. Mechler K, Banaschewski T, Hohmann S, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment options for ADHD in children and adolescents. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;230:107940. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107940

23. Mishra J, Merzenich MM, Sagar R. Accessible online neuroplasticity-targeted training for children with ADHD. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-38

24. Neece CL. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. J Applied Res Intellect Disabil. 2014;27:174-186. doi: 10.1111/jar.12064

25. Petcharat M, Liehr P. Mindfulness training for parents of children with special needs: guidance for nurses in mental health practice. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nursing. 2017;30:35-46. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12169

26. Hahn-Markowitz J, Burger I, Manor I, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-functional (Cog-Fun) occupational therapy intervention among children with ADHD: an RCT. J Atten Disord. 2020;24:655-666. doi: 10.1177/1087054716666955

27. Young Z, Moghaddam N, Tickle A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Atten Disord. 2020;24:875-888.

28. Carr AW, Bean RA, Nelson KF. Childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: family therapy from an attachment based perspective. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105666.

29. Robin AL. Family therapy for adolescents with ADHD. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23:747-756. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.06.001

30. Cattoi B, Alpern I, Katz JS, et al. The adverse health outcomes, economic burden, and public health implications of unmanaged attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a call to action resulting from CHADD summit, Washington, DC, October 17, 2019. J Atten Disord. 2022;26:807-808. doi: 10.1177/10870547211036754

31. Hinojosa MS, Hinojosa R, Nguyen J. Shared decision making and treatment for minority children with ADHD. J Transcult Nurs. 2020;31:135-143. doi: 10.1177/1043659619853021

32. Slobodin O, Masalha R. Challenges in ADHD care for ethnic minority children: a review of the current literature. Transcult Psychiatry. 2020;57:468-483. doi: 10.1177/1363461520902885

33. Retz W, Ginsberg Y, Turner D, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), antisociality and delinquent behavior over the lifespan. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;120:236-248. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.025

34. Del Sol Calderon P, Izquierdo A, Garcia Moreno M. Effects of the pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents. Review and current scientific evidence of the SARS-COV2 pandemic. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64:S223-S224. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.597

35. Insa I, Alda JA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) & COVID-19: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: consequences of the 1st wave. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64:S660. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.1752

THE CASE

James B* is a 7-year-old Black child who presented to his primary care physician (PCP) for a well-child visit. During preventive health screening, James’ mother expressed concerns about his behavior, characterizing him as immature, aggressive, destructive, and occasionally self-loathing. She described him as physically uncoordinated, struggling to keep up with his peers in sports, and tiring after 20 minutes of activity. James slept 10 hours nightly but was often restless and snored intermittently. As a second grader, his academic achievement was not progressing, and he had become increasingly inattentive at home and at school. James’ mother offered several examples of his fighting with his siblings, noncompliance with morning routines, and avoidance of learning activities. Additionally, his mother expressed concern that James, as a Black child, might eventually be unfairly labeled as a problem child by his teachers or held back a grade level in school.

Although James did not have a family history of developmental delays or learning disorders, he had not met any milestones on time for gross or fine motor, language, cognitive, and social-emotional skills. James had a history of chronic otitis media, for which pressure equalizer tubes were inserted at age 2 years. He had not had any major physical injuries, psychological trauma, recent life transitions, or adverse childhood events. When asked, James’ mother acknowledged symptoms of maternal depression but alluded to faith-based reasons for not seeking treatment for herself.

James’ physical examination was unremarkable. His height, weight, and vitals were all within normal limits. However, he had some difficulty with verbal articulation and expression and showed signs of a possible vocal tic. Based on James’ presentation, his PCP suspected attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as neurodevelopmental delays.

The PCP gave James’ mother the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire to complete and the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for her and James’ teacher to fill out independently and return to the clinic. The PCP also instructed James’ mother on how to use a sleep diary to maintain a 1-month log of his sleep patterns and habits. The PCP consulted the integrated behavioral health clinician (IBHC; a clinical social worker embedded in the primary care clinic) and made a warm handoff for the IBHC to further assess James’ maladaptive behaviors and interactions.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

James is one of more than 6 million children, ages 3 to 17 years, in the United States who live with ADHD.1,2 ADHD is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder among children, and it affects multiple cognitive and behavioral domains throughout the lifespan.3 Children with ADHD often initially present in primary care settings; thus, PCPs are well positioned to diagnose the disorder and provide longitudinal treatment. This Behavioral Health Consult reviews clinical assessment and practice guidelines, as well as treatment recommendations applicable across different areas of influence—individual, family, community, and systems—for PCPs and IBHCs to use in managing ADHD in children.

ADHD features can vary by age and sex

ADHD is a persistent pattern of inattention or hyperactivity and impulsivity interfering with functioning or development in childhood and functioning later in adulthood. ADHD symptoms manifest prior to age 12 years and must occur in 2 or more settings.4 Symptoms should not be better explained by another psychiatric disorder or occur exclusively during the course of another disorder (TABLE 1).4

The rate of heritability is high, with significant incidence among first-degree relatives.4 Children with ADHD show executive functioning deficits in 1 or more cognitive domains (eg, visuospatial, memory, inhibitions, decision making, and reward regulation).4,5 The prevalence of ADHD nationally is approximately 9.8% (2.2%, ages 3-5 years; 10%, ages 6-11 years; 13.2%, ages 12-17 years) in children and adolescents; worldwide prevalence is 7.2%.1,6 It persists among 2.6% to 6.8% of adults worldwide.7

Research has shown that boys ages 6 to 11 years are significantly more likely than girls to exhibit attention-getting, externalizing behaviors or conduct problems (eg, hyperactivity, impulsivity, disruption, aggression).1,6 On the other hand, girls ages 12 to 17 years tend to display internalized (eg, depressed mood, anxiety, low self-esteem) or inattentive behaviors, which clinicians and educators may assess as less severe and warranting fewer supportive measures.1

The prevalence of ADHD and its associated factors, which evolve through maturation, underscore the importance of persistent, patient-centered, and collaborative PCP and IBHC clinical management.

Continue to: Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

When caregivers express concerns about their child’s behavior, focus, mood, learning, and socialization, consider initiating a multimodal evaluation for ADHD.5,8 Embarking on an ADHD assessment can require extended or multiple visits to arrive at the diagnosis, followed by still more visits to confirm a course of care and adjust medications. The integrative care approach described in the patient case and elaborated on later in this article can help facilitate assessment and treatment of ADHD.9

Signs of ADHD may be observed at initial screening using a tool such as the Ages & Stages Questionnaire (https://agesandstages.com/products-pricing/asq3/) to reveal indications of norm deviations or delays commensurate with ADHD.10 However, to substantiate the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision criteria for an accurate diagnosis,4 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines require a thorough clinical interview, administration of a standardized assessment tool, and review of objective reports in conjunction with a physical examination and psychosocial evaluation.6 Standardized measures of psychological, neurocognitive, and academic achievement reported by caregivers and collateral contacts (eg, teachers, counselors, coaches, care providers) are needed to maximize data objectivity and symptom accuracy across settings (TABLE 210-17). Additionally, periodic reassessment is recommended to validate changes in diagnostic subtype and treatment plans due to the chronic and dynamic nature of ADHD.

Consider comorbidities and alternate diagnoses

The diagnostic possibility of ADHD should also prompt consideration of other childhood disorders due to the high potential for comorbidities.4,6 In a 2016 study, approximately 64% of

Various medical disorders may manifest with similar signs or symptoms to ADHD, such as thyroid disorders, seizure disorders, adverse drug effects, anemia, genetic anomalies, and others.6,19

If there are behavioral concerns or developmental delays associated with tall stature for age or pubertal or testicular development anomalies, consult a geneticist and a developmental pediatrician for targeted testing and neurodevelopmental assessment, respectively. For example, ADHD is a common comorbidity among boys who also have XYY syndrome (Jacobs syndrome). However, due to the variability of symptoms and severity, XYY syndrome often goes undiagnosed, leaving a host of compounding pervasive and developmental problems untreated. Overall, more than two-thirds of patients with ADHD and a co-occurring condition are either inaccurately diagnosed or not referred for additional assessment and adjunct treatment.21

Continue to: Risks that arise over time

Risks that arise over time. As ADHD persists, adolescents are at greater risk for psychiatric comorbidities, suicidality, and functional impairments (eg, risky behaviors, occupational problems, truancy, delinquency, and poor self-esteem).4,8 Adolescents with internalized behaviors are more likely to experience comorbid depressive disorders with increased risk for self-harm.4,5,8 As adolescents age and their sense of autonomy increases, there is a tendency among those who have received a diagnosis of ADHD to minimize symptoms and decrease the frequency of routine clinic visits along with medication use and treatment compliance.3 Additionally, abuse, misuse, and misappropriation of stimulants among teens and young adults are commonplace.

Wide-scope, multidisciplinary evaluation and close clinical management reduce the potential for imprecise diagnoses, particularly at critical developmental junctures. AAP suggests that PCPs can treat mild and moderate cases of ADHD, but if the treating clinician does not have adequate training, experience, time, or clinical support to manage this condition, early referral is warranted.6

A guide to pharmacotherapy

Approximately 77% of children ages 2 to 17 years with a diagnosis of ADHD receive any form of treatment.2 Treatment for ADHD can include behavioral therapy and medication.2 AAP clinical practice guidelines caution against prescribing medications for children younger than 6 years, relying instead on caregiver-, teacher-, or clinician-administered behavioral strategies and parental training in behavioral modification. For children and adolescents between ages 6 and 18 years, first-line treatment includes pharmacotherapy balanced with behavioral therapy, academic modifications, and educational supports (eg, 504 Plan, individualized education plan [IEP]).6

Psychostimulants are preferred. These agents (eg, methylphenidate, amphetamine) remain the most efficacious class of medications to reduce hyperactivity and inattentiveness and to improve function. While long-acting psychostimulants are associated with better medication adherence and adverse-effect tolerance than are short-acting forms, the latter offer more flexibility in dosing. Start by titrating any stimulant to the lowest effective dose; reassess monthly until potential rebound effects stabilize.

Due to potential adverse effects of this class of medication, screen for any family history or personal risk for structural or electrical cardiac anomalies before starting pharmacotherapy. If any such risks exist, arrange for further cardiac evaluation before initiating medication.6 Adverse effects of stimulants include reduced appetite, gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, anxiousness, parasomnia, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Continue to: Once medication is stabilized...

Once medication is stabilized, monitor treatment 2 to 3 times per year thereafter; watch for longer-term adverse effects such as weight loss, decreased growth rate, and psychiatric comorbidities including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s black box warning of increased risk for suicidality.5,6,22

Other options. The optimal duration of psychostimulant use remains debatable, as existing evidence does not support its long-term use (10 years) over other interventions, such as nonstimulants and nonmedicinal therapies.22 Although backed by less evidence, additional medications indicated for the treatment of ADHD include: (1) atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and (2) the selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, extended-release guanfacine and extended-release clonidine (third-line agent).22

Adverse effects of these FDA-approved medications are similar to those observed in stimulant medications. Evaluation of cardiac risks is recommended before starting nonstimulant medications. The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists may also be used as adjunct therapies to stimulants. Before stopping an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, taper the dosage slowly to avoid the risk for rebound hypertension.6,23 Given the wide variety of medication options and variability of effects, it may be necessary to try different medications as children grow and their symptoms and capacity to manage them change. Additional guidance on FDA-approved medications is available at www.ADHDMedicationGuide.com.

How multilevel care coordination can work

As with other chronic or developmental conditions, the treatment of ADHD requires an interdisciplinary perspective. Continuous, comprehensive case management can help patients overcome obstacles to wellness by balancing the resolution of problems with the development of resilience. Well-documented collaboration of subspecialists, educators, and other stakeholders engaged in ADHD care at multiple levels (individual, family, community, and health care system) increases the likelihood of meaningful, sustainable gains. Using a patient-centered medical home framework, IBHCs or other allied health professionals embedded in, or co-located with, primary care settings can be key to accessing evidence-based treatments that include: psycho-education and mindfulness-based stress reduction training for caregivers24,25; occupational,26 cognitive behavioral,27 or family therapies28,29; neuro-feedback; computer-based attention training; group- or community-based interventions; and academic and social supports.5,8

Treatment approaches that capitalize on children’s neurologic and psychological plasticity and fortify self-efficacy with developmentally appropriate tools empower them to surmount ADHD symptoms over time.23 Facilitating children’s resilience within a developmental framework and health system’s capacities with socio-culturally relevant approaches, consultation, and research can optimize outcomes and mitigate pervasiveness into adulthood. While the patient is at the center of treatment, it is important to consider the family, school, and communities in which the child lives, learns, and plays. PCPs and IBHCs together can consider a “try and track” method to follow progress, changes, and outcomes over time. With this method, the physician can employ approaches that focus on the patient, caregiver, or the caregiver–child interaction (TABLE 3).

Continue to: Assess patients' needs and the resources available

Assess patients’ needs and the resources available throughout the system of care beyond the primary care setting. Stay abreast of hospital policies, health care insurance coverage, and community- and school-based health programs, and any gaps in adequate and equitable assessment and treatment. For example, while clinical recommendations include psychiatric care, health insurance availability or limits in coverage may dissuade caregivers from seeking help or limit initial or long-term access to resources for help.30 Integrating or advocating for clinic support resources or staffing to assist patients in navigating and mitigating challenges may lessen the management burden and increase the likelihood and longevity of favorable health outcomes.

Steps to ensuring health care equity

Among children of historically marginalized and racial and ethnic minority groups or those of populations affected by health disparities, ADHD symptoms and needs are often masked by structural biases that lead to inequitable care and outcomes, as well as treatment misprioritization or delays.31 In particular, evidence has shown that recognition and diagnostic specificity of ADHD and comorbidities, not prevalence, vary more widely among minority than among nonminority populations,32 contributing to the 23% of children with ADHD who receive no treatment at all.2

Understand caregiver concerns. This diagnosis discrepancy is correlated with symptom rating sensitivities (eg, reliability, perception, accuracy) among informants and how caregivers observe, perceive, appreciate, understand, and report behaviors. This discrepancy is also related to cultural belief differences, physician–patient communication variants, and a litany of other socioeconomic determinants.2,4,31 Caregivers from some cultural, ethnic, or socioeconomic backgrounds may be doubtful of psychiatric assessment, diagnoses, treatment, or medication, and that can impact how children are engaged in clinical and educational settings from the outset.31 In the case we described, James’ mother was initially hesitant to explore psychotropic medications and was concerned about stigmatization within the school system. She also seemed to avoid psychiatric treatment for her own depressive symptoms due to cultural and religious beliefs.

Health care provider concerns. Some PCPs may hesitate to explore medications due to limited knowledge and skill in dosing and titrating based on a child’s age, stage, and symptoms, and a perceived lack of competence in managing ADHD. This, too, can indirectly perpetuate existing health disparities. Furthermore, ADHD symptoms may be deemed a secondary or tertiary concern if other complex or urgent medical or undifferentiated developmental problems manifest.

Compounding matters is the limited dissemination of empiric research articles (including randomized controlled trials with representative samples) and limited education on the effectiveness and safety of psychopharmacologic interventions across the lifespan and different cultural and ethnic groups.4 Consequently, patients who struggle with unmanaged ADHD symptoms are more likely to have chronic mental health disorders, maladaptive behaviors, and other co-occurring conditions contributing to the complexity of individual needs, health care burdens, or justice system involvement; this is particularly true for those of racial and ethnic minorities.33

Continue to: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients—particularly those in minority or health disparity populations—who under normal circumstances might have been hesitant to seek help may have felt even more reluctant to do so during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have not yet learned the degree to which limited availability of preventive health care services, decreased routine visits, and fluctuating insurance coverage has impacted the diagnosis, management, or severity of childhood disorders during the past 2 years. Reports of national findings indicate that prolonged periods out of school and reduced daily structure were associated with increased disruptions in mood, sleep, and appetite, particularly among children with pre-existing pathologies. Evidence suggests that school-aged children experienced more anxiety, regressive behaviors, and parasomnias than they did before the pandemic, while adolescents experienced more isolation and depressive symptoms.34,35

However, there remains a paucity of large-scale or representative studies that use an intersectional lens to examine the influence of COVID-19 on children with ADHD. Therefore, PCPs and IBHCs should refocus attention on possibly undiagnosed, stagnated, or regressed ADHD cases, as well as the adults who care for them. (See “5 ways to overcome Tx barriers and promote health equity.”)

SIDEBAR

5 ways to overcome Tx barriers and promote health equitya

1. Inquire about cultural or ethnic beliefs and behaviors and socioeconomic barriers.

2. Establish trust or assuage mistrust by exploring and dispelling misinformation.

3. Offer accessible, feasible, and sustainable evidence-based interventions.

4. Encourage autonomy and selfdetermination throughout the health care process.

5. Connect caregivers and children with clinical, community, and school-based resources and coordinators.

a These recommendations are based on the authors’ combined clinical experience.

THE CASE

During a follow-up visit 1 month later, the PCP confirmed the clinical impression of ADHD combined presentation with a clinical interview and review of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire completed by James’ mother and the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales completed by James’ mother and teacher. The sleep diary indicated potential problems and apneas worthy of consults for pulmonary function testing, a sleep study, and otolaryngology examination. The PCP informed James’ mother on sleep hygiene strategies and ADHD medication options. She indicated that she wanted to pursue the referrals and behavioral modifications before starting any medication trial.

The PCP referred James to a developmental pediatrician for in-depth assessment of his overall development, learning, and functioning. The developmental pediatrician ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of ADHD, as well as motor and speech delays warranting physical, occupational, and speech therapies. The developmental pediatrician also referred James for targeted genetic testing because she suspected a genetic disorder (eg, XYY syndrome).

The PCP reconnected James and his mother to the IBHC to facilitate subspecialty and school-based care coordination and to provide in-office and home-based interventions. The IBHC assessed James’ emotional dysregulation and impulsivity as adversely impacting his interpersonal relationships and planned to address these issues with behavioral and parent–child interaction therapies and skills training during the course of 6 to 12 visits. James’ mother was encouraged to engage his teacher on his academic performance and to initiate a 504 Plan or IEP for in-school accommodations and support. The IBHC aided in tracking his assessments, referrals, follow-ups, access barriers, and treatment goals.

After 6 months, James had made only modest progress, and his mother requested that he begin a trial of medication. Based on his weight, symptoms, behavior patterns, and sleep habits, the PCP prescribed extended-release dexmethylphenidate 10 mg each morning, then extended-release clonidine 0.1 mg nightly. With team-based clinical management of pharmacologic, behavioral, physical, speech, and occupational therapies, James’ behavior and sleep improved, and the signs of a vocal tic diminished.

By the next school year, James demonstrated a marked improvement in impulse control, attention, and academic functioning. He followed up with the PCP at least quarterly for reassessment of his symptoms, growth, and experience of adverse effects, and to titrate medications accordingly. James and his mother continued to work closely with the IBHC monthly to engage interventions and to monitor his progress at home and school.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sundania J. W. Wonnum, PhD, LCSW, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, 6707 Democracy Boulevard, Suite 800, Bethesda, MD 20892; sundania.wonnum@nih.gov

THE CASE

James B* is a 7-year-old Black child who presented to his primary care physician (PCP) for a well-child visit. During preventive health screening, James’ mother expressed concerns about his behavior, characterizing him as immature, aggressive, destructive, and occasionally self-loathing. She described him as physically uncoordinated, struggling to keep up with his peers in sports, and tiring after 20 minutes of activity. James slept 10 hours nightly but was often restless and snored intermittently. As a second grader, his academic achievement was not progressing, and he had become increasingly inattentive at home and at school. James’ mother offered several examples of his fighting with his siblings, noncompliance with morning routines, and avoidance of learning activities. Additionally, his mother expressed concern that James, as a Black child, might eventually be unfairly labeled as a problem child by his teachers or held back a grade level in school.

Although James did not have a family history of developmental delays or learning disorders, he had not met any milestones on time for gross or fine motor, language, cognitive, and social-emotional skills. James had a history of chronic otitis media, for which pressure equalizer tubes were inserted at age 2 years. He had not had any major physical injuries, psychological trauma, recent life transitions, or adverse childhood events. When asked, James’ mother acknowledged symptoms of maternal depression but alluded to faith-based reasons for not seeking treatment for herself.

James’ physical examination was unremarkable. His height, weight, and vitals were all within normal limits. However, he had some difficulty with verbal articulation and expression and showed signs of a possible vocal tic. Based on James’ presentation, his PCP suspected attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as neurodevelopmental delays.

The PCP gave James’ mother the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire to complete and the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for her and James’ teacher to fill out independently and return to the clinic. The PCP also instructed James’ mother on how to use a sleep diary to maintain a 1-month log of his sleep patterns and habits. The PCP consulted the integrated behavioral health clinician (IBHC; a clinical social worker embedded in the primary care clinic) and made a warm handoff for the IBHC to further assess James’ maladaptive behaviors and interactions.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

James is one of more than 6 million children, ages 3 to 17 years, in the United States who live with ADHD.1,2 ADHD is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder among children, and it affects multiple cognitive and behavioral domains throughout the lifespan.3 Children with ADHD often initially present in primary care settings; thus, PCPs are well positioned to diagnose the disorder and provide longitudinal treatment. This Behavioral Health Consult reviews clinical assessment and practice guidelines, as well as treatment recommendations applicable across different areas of influence—individual, family, community, and systems—for PCPs and IBHCs to use in managing ADHD in children.

ADHD features can vary by age and sex

ADHD is a persistent pattern of inattention or hyperactivity and impulsivity interfering with functioning or development in childhood and functioning later in adulthood. ADHD symptoms manifest prior to age 12 years and must occur in 2 or more settings.4 Symptoms should not be better explained by another psychiatric disorder or occur exclusively during the course of another disorder (TABLE 1).4

The rate of heritability is high, with significant incidence among first-degree relatives.4 Children with ADHD show executive functioning deficits in 1 or more cognitive domains (eg, visuospatial, memory, inhibitions, decision making, and reward regulation).4,5 The prevalence of ADHD nationally is approximately 9.8% (2.2%, ages 3-5 years; 10%, ages 6-11 years; 13.2%, ages 12-17 years) in children and adolescents; worldwide prevalence is 7.2%.1,6 It persists among 2.6% to 6.8% of adults worldwide.7

Research has shown that boys ages 6 to 11 years are significantly more likely than girls to exhibit attention-getting, externalizing behaviors or conduct problems (eg, hyperactivity, impulsivity, disruption, aggression).1,6 On the other hand, girls ages 12 to 17 years tend to display internalized (eg, depressed mood, anxiety, low self-esteem) or inattentive behaviors, which clinicians and educators may assess as less severe and warranting fewer supportive measures.1

The prevalence of ADHD and its associated factors, which evolve through maturation, underscore the importance of persistent, patient-centered, and collaborative PCP and IBHC clinical management.

Continue to: Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

When caregivers express concerns about their child’s behavior, focus, mood, learning, and socialization, consider initiating a multimodal evaluation for ADHD.5,8 Embarking on an ADHD assessment can require extended or multiple visits to arrive at the diagnosis, followed by still more visits to confirm a course of care and adjust medications. The integrative care approach described in the patient case and elaborated on later in this article can help facilitate assessment and treatment of ADHD.9

Signs of ADHD may be observed at initial screening using a tool such as the Ages & Stages Questionnaire (https://agesandstages.com/products-pricing/asq3/) to reveal indications of norm deviations or delays commensurate with ADHD.10 However, to substantiate the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision criteria for an accurate diagnosis,4 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines require a thorough clinical interview, administration of a standardized assessment tool, and review of objective reports in conjunction with a physical examination and psychosocial evaluation.6 Standardized measures of psychological, neurocognitive, and academic achievement reported by caregivers and collateral contacts (eg, teachers, counselors, coaches, care providers) are needed to maximize data objectivity and symptom accuracy across settings (TABLE 210-17). Additionally, periodic reassessment is recommended to validate changes in diagnostic subtype and treatment plans due to the chronic and dynamic nature of ADHD.

Consider comorbidities and alternate diagnoses

The diagnostic possibility of ADHD should also prompt consideration of other childhood disorders due to the high potential for comorbidities.4,6 In a 2016 study, approximately 64% of

Various medical disorders may manifest with similar signs or symptoms to ADHD, such as thyroid disorders, seizure disorders, adverse drug effects, anemia, genetic anomalies, and others.6,19

If there are behavioral concerns or developmental delays associated with tall stature for age or pubertal or testicular development anomalies, consult a geneticist and a developmental pediatrician for targeted testing and neurodevelopmental assessment, respectively. For example, ADHD is a common comorbidity among boys who also have XYY syndrome (Jacobs syndrome). However, due to the variability of symptoms and severity, XYY syndrome often goes undiagnosed, leaving a host of compounding pervasive and developmental problems untreated. Overall, more than two-thirds of patients with ADHD and a co-occurring condition are either inaccurately diagnosed or not referred for additional assessment and adjunct treatment.21

Continue to: Risks that arise over time

Risks that arise over time. As ADHD persists, adolescents are at greater risk for psychiatric comorbidities, suicidality, and functional impairments (eg, risky behaviors, occupational problems, truancy, delinquency, and poor self-esteem).4,8 Adolescents with internalized behaviors are more likely to experience comorbid depressive disorders with increased risk for self-harm.4,5,8 As adolescents age and their sense of autonomy increases, there is a tendency among those who have received a diagnosis of ADHD to minimize symptoms and decrease the frequency of routine clinic visits along with medication use and treatment compliance.3 Additionally, abuse, misuse, and misappropriation of stimulants among teens and young adults are commonplace.

Wide-scope, multidisciplinary evaluation and close clinical management reduce the potential for imprecise diagnoses, particularly at critical developmental junctures. AAP suggests that PCPs can treat mild and moderate cases of ADHD, but if the treating clinician does not have adequate training, experience, time, or clinical support to manage this condition, early referral is warranted.6

A guide to pharmacotherapy

Approximately 77% of children ages 2 to 17 years with a diagnosis of ADHD receive any form of treatment.2 Treatment for ADHD can include behavioral therapy and medication.2 AAP clinical practice guidelines caution against prescribing medications for children younger than 6 years, relying instead on caregiver-, teacher-, or clinician-administered behavioral strategies and parental training in behavioral modification. For children and adolescents between ages 6 and 18 years, first-line treatment includes pharmacotherapy balanced with behavioral therapy, academic modifications, and educational supports (eg, 504 Plan, individualized education plan [IEP]).6

Psychostimulants are preferred. These agents (eg, methylphenidate, amphetamine) remain the most efficacious class of medications to reduce hyperactivity and inattentiveness and to improve function. While long-acting psychostimulants are associated with better medication adherence and adverse-effect tolerance than are short-acting forms, the latter offer more flexibility in dosing. Start by titrating any stimulant to the lowest effective dose; reassess monthly until potential rebound effects stabilize.

Due to potential adverse effects of this class of medication, screen for any family history or personal risk for structural or electrical cardiac anomalies before starting pharmacotherapy. If any such risks exist, arrange for further cardiac evaluation before initiating medication.6 Adverse effects of stimulants include reduced appetite, gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, anxiousness, parasomnia, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Continue to: Once medication is stabilized...

Once medication is stabilized, monitor treatment 2 to 3 times per year thereafter; watch for longer-term adverse effects such as weight loss, decreased growth rate, and psychiatric comorbidities including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s black box warning of increased risk for suicidality.5,6,22

Other options. The optimal duration of psychostimulant use remains debatable, as existing evidence does not support its long-term use (10 years) over other interventions, such as nonstimulants and nonmedicinal therapies.22 Although backed by less evidence, additional medications indicated for the treatment of ADHD include: (1) atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and (2) the selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, extended-release guanfacine and extended-release clonidine (third-line agent).22

Adverse effects of these FDA-approved medications are similar to those observed in stimulant medications. Evaluation of cardiac risks is recommended before starting nonstimulant medications. The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists may also be used as adjunct therapies to stimulants. Before stopping an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, taper the dosage slowly to avoid the risk for rebound hypertension.6,23 Given the wide variety of medication options and variability of effects, it may be necessary to try different medications as children grow and their symptoms and capacity to manage them change. Additional guidance on FDA-approved medications is available at www.ADHDMedicationGuide.com.

How multilevel care coordination can work

As with other chronic or developmental conditions, the treatment of ADHD requires an interdisciplinary perspective. Continuous, comprehensive case management can help patients overcome obstacles to wellness by balancing the resolution of problems with the development of resilience. Well-documented collaboration of subspecialists, educators, and other stakeholders engaged in ADHD care at multiple levels (individual, family, community, and health care system) increases the likelihood of meaningful, sustainable gains. Using a patient-centered medical home framework, IBHCs or other allied health professionals embedded in, or co-located with, primary care settings can be key to accessing evidence-based treatments that include: psycho-education and mindfulness-based stress reduction training for caregivers24,25; occupational,26 cognitive behavioral,27 or family therapies28,29; neuro-feedback; computer-based attention training; group- or community-based interventions; and academic and social supports.5,8

Treatment approaches that capitalize on children’s neurologic and psychological plasticity and fortify self-efficacy with developmentally appropriate tools empower them to surmount ADHD symptoms over time.23 Facilitating children’s resilience within a developmental framework and health system’s capacities with socio-culturally relevant approaches, consultation, and research can optimize outcomes and mitigate pervasiveness into adulthood. While the patient is at the center of treatment, it is important to consider the family, school, and communities in which the child lives, learns, and plays. PCPs and IBHCs together can consider a “try and track” method to follow progress, changes, and outcomes over time. With this method, the physician can employ approaches that focus on the patient, caregiver, or the caregiver–child interaction (TABLE 3).

Continue to: Assess patients' needs and the resources available

Assess patients’ needs and the resources available throughout the system of care beyond the primary care setting. Stay abreast of hospital policies, health care insurance coverage, and community- and school-based health programs, and any gaps in adequate and equitable assessment and treatment. For example, while clinical recommendations include psychiatric care, health insurance availability or limits in coverage may dissuade caregivers from seeking help or limit initial or long-term access to resources for help.30 Integrating or advocating for clinic support resources or staffing to assist patients in navigating and mitigating challenges may lessen the management burden and increase the likelihood and longevity of favorable health outcomes.

Steps to ensuring health care equity

Among children of historically marginalized and racial and ethnic minority groups or those of populations affected by health disparities, ADHD symptoms and needs are often masked by structural biases that lead to inequitable care and outcomes, as well as treatment misprioritization or delays.31 In particular, evidence has shown that recognition and diagnostic specificity of ADHD and comorbidities, not prevalence, vary more widely among minority than among nonminority populations,32 contributing to the 23% of children with ADHD who receive no treatment at all.2

Understand caregiver concerns. This diagnosis discrepancy is correlated with symptom rating sensitivities (eg, reliability, perception, accuracy) among informants and how caregivers observe, perceive, appreciate, understand, and report behaviors. This discrepancy is also related to cultural belief differences, physician–patient communication variants, and a litany of other socioeconomic determinants.2,4,31 Caregivers from some cultural, ethnic, or socioeconomic backgrounds may be doubtful of psychiatric assessment, diagnoses, treatment, or medication, and that can impact how children are engaged in clinical and educational settings from the outset.31 In the case we described, James’ mother was initially hesitant to explore psychotropic medications and was concerned about stigmatization within the school system. She also seemed to avoid psychiatric treatment for her own depressive symptoms due to cultural and religious beliefs.

Health care provider concerns. Some PCPs may hesitate to explore medications due to limited knowledge and skill in dosing and titrating based on a child’s age, stage, and symptoms, and a perceived lack of competence in managing ADHD. This, too, can indirectly perpetuate existing health disparities. Furthermore, ADHD symptoms may be deemed a secondary or tertiary concern if other complex or urgent medical or undifferentiated developmental problems manifest.

Compounding matters is the limited dissemination of empiric research articles (including randomized controlled trials with representative samples) and limited education on the effectiveness and safety of psychopharmacologic interventions across the lifespan and different cultural and ethnic groups.4 Consequently, patients who struggle with unmanaged ADHD symptoms are more likely to have chronic mental health disorders, maladaptive behaviors, and other co-occurring conditions contributing to the complexity of individual needs, health care burdens, or justice system involvement; this is particularly true for those of racial and ethnic minorities.33

Continue to: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients—particularly those in minority or health disparity populations—who under normal circumstances might have been hesitant to seek help may have felt even more reluctant to do so during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have not yet learned the degree to which limited availability of preventive health care services, decreased routine visits, and fluctuating insurance coverage has impacted the diagnosis, management, or severity of childhood disorders during the past 2 years. Reports of national findings indicate that prolonged periods out of school and reduced daily structure were associated with increased disruptions in mood, sleep, and appetite, particularly among children with pre-existing pathologies. Evidence suggests that school-aged children experienced more anxiety, regressive behaviors, and parasomnias than they did before the pandemic, while adolescents experienced more isolation and depressive symptoms.34,35

However, there remains a paucity of large-scale or representative studies that use an intersectional lens to examine the influence of COVID-19 on children with ADHD. Therefore, PCPs and IBHCs should refocus attention on possibly undiagnosed, stagnated, or regressed ADHD cases, as well as the adults who care for them. (See “5 ways to overcome Tx barriers and promote health equity.”)

SIDEBAR

5 ways to overcome Tx barriers and promote health equitya

1. Inquire about cultural or ethnic beliefs and behaviors and socioeconomic barriers.

2. Establish trust or assuage mistrust by exploring and dispelling misinformation.

3. Offer accessible, feasible, and sustainable evidence-based interventions.

4. Encourage autonomy and selfdetermination throughout the health care process.

5. Connect caregivers and children with clinical, community, and school-based resources and coordinators.

a These recommendations are based on the authors’ combined clinical experience.

THE CASE

During a follow-up visit 1 month later, the PCP confirmed the clinical impression of ADHD combined presentation with a clinical interview and review of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire completed by James’ mother and the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales completed by James’ mother and teacher. The sleep diary indicated potential problems and apneas worthy of consults for pulmonary function testing, a sleep study, and otolaryngology examination. The PCP informed James’ mother on sleep hygiene strategies and ADHD medication options. She indicated that she wanted to pursue the referrals and behavioral modifications before starting any medication trial.

The PCP referred James to a developmental pediatrician for in-depth assessment of his overall development, learning, and functioning. The developmental pediatrician ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of ADHD, as well as motor and speech delays warranting physical, occupational, and speech therapies. The developmental pediatrician also referred James for targeted genetic testing because she suspected a genetic disorder (eg, XYY syndrome).

The PCP reconnected James and his mother to the IBHC to facilitate subspecialty and school-based care coordination and to provide in-office and home-based interventions. The IBHC assessed James’ emotional dysregulation and impulsivity as adversely impacting his interpersonal relationships and planned to address these issues with behavioral and parent–child interaction therapies and skills training during the course of 6 to 12 visits. James’ mother was encouraged to engage his teacher on his academic performance and to initiate a 504 Plan or IEP for in-school accommodations and support. The IBHC aided in tracking his assessments, referrals, follow-ups, access barriers, and treatment goals.

After 6 months, James had made only modest progress, and his mother requested that he begin a trial of medication. Based on his weight, symptoms, behavior patterns, and sleep habits, the PCP prescribed extended-release dexmethylphenidate 10 mg each morning, then extended-release clonidine 0.1 mg nightly. With team-based clinical management of pharmacologic, behavioral, physical, speech, and occupational therapies, James’ behavior and sleep improved, and the signs of a vocal tic diminished.

By the next school year, James demonstrated a marked improvement in impulse control, attention, and academic functioning. He followed up with the PCP at least quarterly for reassessment of his symptoms, growth, and experience of adverse effects, and to titrate medications accordingly. James and his mother continued to work closely with the IBHC monthly to engage interventions and to monitor his progress at home and school.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sundania J. W. Wonnum, PhD, LCSW, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, 6707 Democracy Boulevard, Suite 800, Bethesda, MD 20892; sundania.wonnum@nih.gov

1. Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, et al. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Suppl. 2022;71:1-42. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

2. Danielson ML, Holbrook JR, Blumberg SJ, et al. State-level estimates of the prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016 to 2019. J Atten Disord. 2022;26:1685-1697. doi: 10.1177/10870547221099961

3. Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, et al. The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:789-818. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022

4. American Psychiatric Association

5. Brahmbhatt K, Hilty DM, Mina H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during adolescence in the primary care setting: a concise review. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:135-143. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.025

6. Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, et al. AAP Subcommittee on Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20192528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2528

7. Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04009. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.04009

8. Chang JG, Cimino FM, Gossa W. ADHD in children: common questions and answers. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:592-602.

9. Asarnow JR, Rozenman M, Wiblin J, et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:929-937. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1141

10. Squires J, Bricker D. Ages & Stages Questionnaires®. 3rd ed (ASQ®-3). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc; 2009.

11. DuPaul GJ, Barkley RA. Situational variability of attention problems: psychometric properties of the Revised Home and School Situations Questionnaires. J Clin Child Psychol. 1992;21:178-188. doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2102_10

12. Merenda PF. BASC: behavior assessment system for children. Meas Eval Counsel Develop. 1996;28:229-232.

13. Conners CK. Conners, 3rd ed manual. Multi-Health Systems. 2008.

14. Achenbach TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments. In: Maruish ME, ed. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999:429-466.

15. Goodman R. The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:791-799.

16. Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale in a referred population. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:559-567. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046

17. Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. In: Newmark CS, ed. Major Psychological Assessment Instruments. Vol 2. Allyn & Bacon; 2003:199-231.

18. Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47:199-212. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860

19. Ghriwati NA, Langberg JM, Gardner W, et al. Impact of mental health comorbidities on the community-based pediatric treatment and outcomes of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Ped. 2017;38:20-28. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000359

20. Niclasen J, Obel C, Homøe P, et al. Associations between otitis media and child behavioural and learning difficulties: results from a Danish Cohort. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;84:12-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.02.017

21. Ross JL Roeltgen DP Kushner H, et al. Behavioral and social phenotypes in boys with 47,XYY syndrome or 47,XXY Klinefelter syndrome. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0719

22. Mechler K, Banaschewski T, Hohmann S, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment options for ADHD in children and adolescents. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;230:107940. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107940

23. Mishra J, Merzenich MM, Sagar R. Accessible online neuroplasticity-targeted training for children with ADHD. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-38