User login

Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be a tough diagnosis to navigate. Patients with this neurologic movement disorder can present with a highly variable constellation of symptoms,1 ranging from the well-known tremor and bradykinesia to difficulties with activities of daily living (particularly dressing and getting out of a car2) to nonspecific symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, hyposmia, and erectile dysfunction.3

Furthermore, medications more recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have left many health care providers confused about what constitutes appropriate first-, second-, and third-line therapies, as well as add-on therapy for symptoms secondary to dopaminergic agents. What follows is a stepwise approach to managing PD that incorporates these newer therapies so that you can confidently and effectively manage patients with PD with little or no consultation.

First, though, we review who’s at greatest risk—and what you’ll see.

Family history tops list of risk factors for PD

While PD occurs in less than 1% of the population ≥40 years of age, its prevalence increases with age, becoming significantly higher by age 60 years, with a slight predominance toward males.4

A variety of factors increase the risk of developing PD. A well-conducted meta-analysis showed that the strongest risk factor is having a family member, particularly a first-degree relative, with a history of PD or tremor.5 Repeated head injury, with or without loss of consciousness, is also a factor;5 risk increases with each occurrence.6 Other risk factors include exposure to pesticides, rural living, and exposure to well water.5

Researchers have conducted several studies regarding the effects of elevated cholesterol and hypertension on the risk of PD, but results are still without consensus.5 A study published in 2017 reported a significantly increased risk of PD associated with having hepatitis B or C, but the mechanism for the association—including whether it is a consequence of treatment—is unknown.7

Smoking and coffee drinking. Researchers have found that cigarette smoking, beer consumption, and high coffee intake are protective against PD,5 but the benefits are outweighed by the risks associated with these strategies.8 The most practical protective factors are a high dietary intake of vitamin E and increased nut consumption.9 Dietary vitamin E can be found in almonds, spinach, sweet potatoes, sunflower seeds, and avocados. Studies have not found the same benefit with vitamin E supplements.9

Dx seldom requires testing, but may take time to come into focus

Motor symptoms. The key diagnostic criterium for PD is bradykinesia with at least one of the following: muscular rigidity, resting tremor (particularly a pill-rolling tremor) that improves with purposeful function, or postural instability.2 Other physical findings may include masking of facies and speech changes, such as becoming quiet, stuttering, or speaking monotonously without inflection.1 Cogwheeling, stooped posture, and a shuffling gait or difficulty initiating gait (freezing) are all neurologic signs that point toward a PD diagnosis.2

A systematic review found that the clinical features most strongly associated with a diagnosis of PD were trouble turning in bed, a shuffling gait, tremor, difficulty opening jars, micrographia, and loss of balance.10 Typically these symptoms are asymmetric.1

Symptoms that point to other causes. Falling within the first year of symptoms is strongly associated with movement disorders other than PD—notably progressive supranuclear palsy.11 Other symptoms that point toward an alternate diagnosis include a poor response to levodopa, symmetry at the onset of symptoms, rapid progression of disease, and the absence of a tremor.11 It is important to ensure that the patient is not experiencing drug-induced symptoms as can occur with some antipsychotics and antiemetics.

Nonmotor symptoms. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in patients with PD. Up to 58% of patients experience depression, and 49% complain of anxiety.12 Hallucinations are present in many patients and are more commonly visual than auditory in nature.13 Patients experience fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and inner restlessness at higher rates than do age-matched controls.3 Research also shows that symptoms such as constipation, mood disorders, erectile dysfunction, and hyposmia may predate the onset of motor symptoms.5

Insomnia is a common symptom that is likely multifactorial in etiology. Causes to consider include motor disturbance, nocturia, reversal of sleep patterns, and reemergence of PD symptoms after a period of quiescence.14 Additionally, hypersalivation and PD dementia can develop as complications of PD.

A clinical diagnosis. Although PD can be difficult to diagnose in the early stages, the diagnosis seldom requires testing.2 A recent systematic review concluded that a clinical diagnosis of PD, when compared with pathology, was correct 74% of the time when the diagnosis was made by nonexperts and correct 84% of the time when the diagnosis was made by movement disorder experts.15

Imaging. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in ruling out other diagnoses in the differential, including vascular disease and normal pressure hydrocephalus,2 but will not reveal findings suggestive of PD.

Other diagnostic tests. A levodopa challenge can confirm PD if the diagnosis is unclear.11 In addition, an olfactory test (presenting various odors to the patient for identification) can differentiate PD from progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration; however, it will not distinguish PD from multiple system atrophy.11 If the diagnosis remains unclear, consider a consultation with a neurologist.

Treatment centers on alleviating motor symptoms

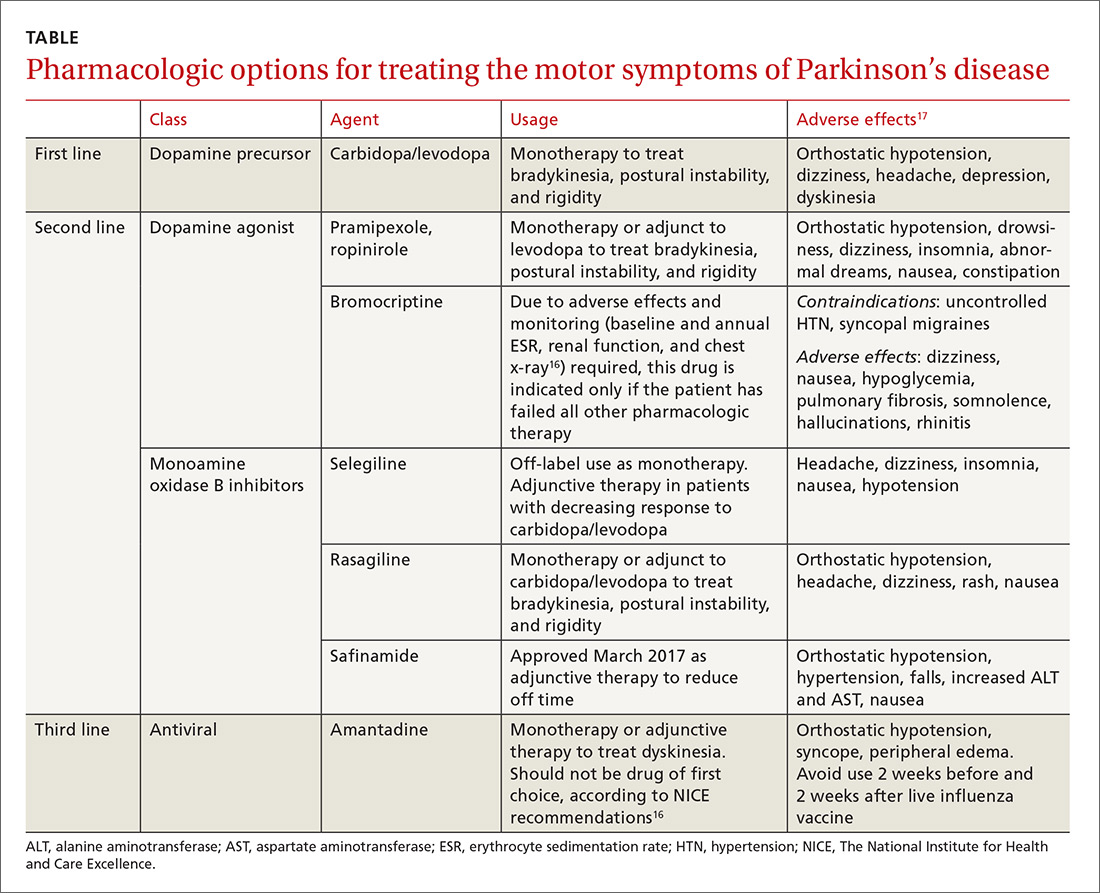

The general guiding principle of therapy (TABLE16,17) is to alleviate the motor symptoms (bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability) associated with the disease. Experts recommend that treatment commence when symptoms begin to have disabling effects or become a source of discomfort for the patient.1

Carbidopa/levodopa is still often the first choice

Multiple systematic reviews support the use of carbidopa/levodopa as first-line treatment, with the dose kept as low as possible to maintain function, while minimizing motor fluctuations (also referred to as “off” time symptoms) and dyskinesia.11,16 Initial dosing is carbidopa 25 mg/levodopa 100 mg tid. Each can be titrated up to address symptoms to a maximum daily dosing of carbidopa 200 mg/levodopa 2000 mg.17

“Off” time—the return of Parkinson symptoms when the medication’s effect wanes—can become more unpredictable and more difficult to manage as the disease advances.11 Of note: The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) says there is no improvement in the amount of off time a patient experiences by changing to a sustained-release form of carbidopa/levodopa compared with an immediate-release version.11 In addition to the on-off phenomenon, common adverse effects associated with carbidopa/levodopa include nausea, somnolence, dizziness, and headaches. Less common adverse effects include orthostatic hypotension, confusion, and hallucinations.17

Other medications for the treatment of motor symptoms

Second-line agents include dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole, and bromocriptine) and monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors (selegiline, rasagiline) (TABLE16,17). The dopamine agonists work by directly stimulating dopamine receptors, while the MAO-B inhibitors block dopamine metabolism, thus enhancing dopaminergic activity in the substantia nigra.

The pros/cons of these 2 classes. Research shows that both dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors are less effective than carbidopa/levodopa at quelling the motor symptoms associated with PD. They can, however, delay the onset of motor complications when compared with carbidopa/levodopa.16

One randomized trial found no long-term benefits to beginning treatment with a levodopa-sparing therapy; however, few patients with earlier disease onset (<60 years of age) were included in the study.18 Given the typically longer duration of their illness, there is potential for this group of patients to develop a higher rate of motor symptoms secondary to carbidopa/levodopa. Thus, considering dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors as initial therapy in patients ages <60 years may be helpful, since they typically will be taking medication longer.

Dopamine agonists. Pramipexole and ropinirole can be used as monotherapy or as an adjunct to levodopa to treat bradykinesia, postural instability, and rigidity. Bromocriptine, an ergot-derived dopamine agonist, is considered an agent of last resort because additional monitoring is required. Potential adverse effects mandate baseline testing and annual repeat testing, including measures of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and renal function and a chest x-ray.16 Consider this agent only if all second- and third-line therapies have provided inadequate control.16

Adverse effects. Dopamine agonists cause such adverse effects as orthostatic hypotension, drowsiness, dizziness, insomnia, abnormal dreams, nausea, constipation, and hallucinations. A Cochrane review notes that these adverse effects have led to higher drop-out rates than seen for carbidopa/levodopa in studies that compared the 2.19

Patients should be counseled about an additional adverse effect associated with dopamine agonists—the possible development of an impulse-control disorder, such as gambling, binge eating, or hypersexuality.1 If a patient develops any of these behaviors, promptly lower the dose of the dopamine agonist or stop the medication.16

The MAO-B inhibitors selegiline and rasagiline may also be considered for initial therapy but are more commonly used as adjunct therapy. Use of selegiline as monotherapy for PD is an off-label indication. Adverse effects for this class of agents include headache, dizziness, insomnia, nausea, and hypotension.

Add-on therapy to treat the adverse effects of primary therapy

Dopaminergic therapies come at the price of the development of off-time motor symptoms and dyskinesia.1,20 In general, these complications are managed by the addition of a dopamine agonist, MAO-B inhibitor, or a catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor (entacapone).1

Rasagiline and entacapone are a good place to start and should be offered to patients to reduce off-time symptoms, according to the AAN (a Level A recommendation based on multiple high-level studies; see here for an explanation of Strength of Recommendation).

The newest medication, safinamide, has been shown to increase “on” time by one hour per day when compared with placebo; however, it has not yet been tested against existing therapies.21 Other medications that can be considered to reduce drug-induced motor complications include pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, and tolcapone.20 Carbidopa/levodopa and bromocriptine are not recommended for the treatment of dopaminergic motor complications.20 Both sustained-release carbidopa/levodopa and bromocriptine are no longer recommended to decrease off time due to ineffectiveness.20

The only medication that has evidence for reducing dyskinesias in patients with PD is amantadine;20 however, it has no effect on other motor symptoms and should not be considered first line.16 Additionally, as an antiviral agent active against some strains of influenza, it should not be taken 2 weeks before or after receiving the influenza vaccine.

When tremor dominates …

For many patients with PD, tremor is more difficult to treat than is bradykinesia, rigidity, and gait disturbance.16 For patients with tremor-predominant PD (characterized by prominent tremor of one or more limbs and a relative lack of significant rigidity and bradykinesia), first-line treatment choices are dopamine agonists (ropinirole, pramipexole), carbidopa/levodopa, and anticholinergic medications, including benztropine and trihexyphenidyl.22 Second-line choices include clozapine, amantadine, clonazepam, and propranolol.22

Treating nonmotor symptoms

Treatment of hypersalivation should start with an evaluation by a speech pathologist. If it doesn’t improve, then adjuvant treatment with glycopyrrolate may be considered.16 Carbidopa/levodopa has the best evidence for treating periodic limb movements of sleep,14 although dopamine agonists may also be considered.16 More research is needed to find an effective therapy to improve insomnia in patients with PD, but for now consider a nighttime dose of carbidopa/levodopa or melatonin.14

Treating cognitive disorders associated with PD

Depression. Treatment of depression in patients with PD is difficult. Multiple systematic reviews have been unable to find a difference in those treated with antidepressants and those not.23 In practice, the use of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and a combination of an SSRI and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor are commonly used. Additionally, some evidence suggests that pramipexole improves depressive symptoms, but additional research is needed.1

Dementia. Dementia occurs in up to 83% of those who have had PD for more than 20 years.1 Treatment includes the use of rivastigmine (a cholinesterase inhibitor).1 Further research is needed to determine whether donepezil improves dementia symptoms in patients with PD.1

Psychotic symptoms. Query patients and their families periodically about hallucinations and delusions.16 If such symptoms are present and not well tolerated by the patient and/or family, treatment options include quetiapine and clozapine.1 While clozapine is more effective, it requires frequent hematologic monitoring due to the risk of agranulocytosis.1 And quetiapine carries a black box warning about early death. Exercise caution when prescribing these medications, particularly if a patient is cognitively impaired, and always start with low doses.1

A newer medication, pimavanserin (a second-generation antipsychotic), was recently approved by the FDA to treat hallucinations and delusions of PD psychosis, although any improvement this agent provides may not be clinically significant.24 Unlike clozapine, no additional monitoring is needed and there are no significant safety concerns with the use of pimavanserin, which makes it a reasonable first choice for hallucinations and delusions. Other neuroleptic medications should not be used as they tend to worsen Parkinson symptoms.1

Consider tai chi, physical therapy to reduce falls

One study showed that tai chi, performed for an hour twice weekly, was significantly more effective at reducing falls when compared to the same amount of resistance training and strength training, and that the benefits remained 3 months after the completion of the 24-week study.25 To date, tai chi is the only intervention that has been shown to affect fall risk.

Guidelines recommend that physical therapy be available to all patients.16 A Cochrane review performed in 2013 determined that physical therapy improves walking endurance and balance but does not affect quality of life in terms of fear of falling.26

When meds no longer help, consider deep brain stimulation as a last resort

Deep brain stimulation consists of surgical implantation of a device to deliver electrical current to a targeted area of the brain. It can be considered for patients with PD who are no longer responsive to carbidopa/levodopa, not experiencing neuropsychiatric symptoms, and are experiencing significant motor complications despite optimal medical management.14 Referral to a specialist is recommended for these patients to assess their candidacy for this procedure.

Prognosis: Largely unchanged

While medications can improve quality of life and function, PD remains a chronic and progressive disorder that is associated with significant morbidity. A study performed in 2013 showed that older age at onset, cognitive dysfunction, and motor symptoms nonresponsive to levodopa were associated with faster progression toward disability.27

Keep an eye on patients’ bone mineral density (BMD), as patients with PD tend to have lower BMD,28 a 2-fold increase in the risk of fracture for both men and women,29 and a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency.30

Also, watch for signs of infection because the most commonly cited cause of death in those with PD is pneumonia rather than a complication of the disease itself.11

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Mendoza, MD, MPH, MS, FAAFP, 777 South Clinton Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620; Michael_Mendoza@urmc.rochester.edu.

1. Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896-912.

2. Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055-2066.

3. Todorova A, Jenner P, Chaudhuri K. Non-motor Parkinson’s: integral to motor Parkinson’s, yet often neglected. Pract Neurol. 2014;14:310-322.

4. Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, et al. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1583-1590.

5. Noyce AJ, Bestwick JP, Silveira-Moriyama L, et al. Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:893-901.

6. Dick FD, De Palma G, Ahmadi A, et al. Environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism: the Geoparkinson study. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:666-672.

7. Pakpoor J, Noyce A, Goldacre R, et al. Viral hepatitis and Parkinson disease: a national record-linkage study. Neurology. 2017;88:1630-1633.

8. Hern T, Newton W. Does coffee protect against the development of Parkinson disease (PD)? J Fam Pract. 2000;49:685-686.

9. Zhang SM, Hernán MA, Chen H, et al. Intakes of vitamins E and C, carotenoids, vitamin supplements, and PD risk. Neurology. 2002;59:1161-1169.

10. Rao G, Fisch L, Srinivasan S, et al. Does this patient have Parkinson disease? JAMA. 2003;289:347-353.

11. Suchowersky O, Reich S, Perlmutter J, et al. Practice Parameter: diagnosis and prognosis of new onset Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:968-975.

12. Aarsland D, Brønnick K, Ehrt U, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia: frequency, profile and associated care giver stress. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:36-42.

13. Inzelberg R, Kipervasser S, Korczyn AD. Auditory hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:533-535.

14. Zesiewicz TA, Sullivan KL, Arnulf I, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010;74:924-931.

15. Rizzo G, Copetti M, Arcuti S, et al. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2016;86:566-576.

16. National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence. Parkinson’s disease in adults. NICE guideline NG 71. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71. Accessed March 27, 2018.

17. Lexicomp version 4.0.1. Wolters Kluwer; Copyright 2017. Available at: https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home. Accessed March 27, 2018.

18. Lang AE, Marras C. Initiating dopaminergic treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2014;384:1164-1166.

19. Stowe RL, Ives NJ, Clarke C, et al. Dopamine agonist therapy in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD006564.

20. Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of Parkinson disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:983-995.

21. Schapira AH, Fox SH, Hauser RA, et al. Assessment of safety and efficacy of safinamide as a levodopa adjunct in patients with Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:216-224.

22. Marjama-Lyons J, Koller W. Tremor-predominant Parkinson’s disease. Approaches to treatment. Drugs Aging. 2000;16:273-278.

23. Price A, Rayner L, Okon-Rocha E, et al. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in neurological disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:914-923.

24. Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:533-540.

25. Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:511-519.

26. Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD002817.

27. Velseboer DC, Broeders M, Post B, et al. Prognostic factors of motor impairment, disability, and quality of life in newly diagnosed PD. Neurology. 2013;80:627-633.

28. Cronin H, Casey MC, Inderhaugh J, et al. Osteoporosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1797-1798.

29. Tan L, Wang Y, Zhou L, et al. Parkinson’s disease and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94379.

30. Evatt ML, Delong MR, Khazai N, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in patients with Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1348-1352.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be a tough diagnosis to navigate. Patients with this neurologic movement disorder can present with a highly variable constellation of symptoms,1 ranging from the well-known tremor and bradykinesia to difficulties with activities of daily living (particularly dressing and getting out of a car2) to nonspecific symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, hyposmia, and erectile dysfunction.3

Furthermore, medications more recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have left many health care providers confused about what constitutes appropriate first-, second-, and third-line therapies, as well as add-on therapy for symptoms secondary to dopaminergic agents. What follows is a stepwise approach to managing PD that incorporates these newer therapies so that you can confidently and effectively manage patients with PD with little or no consultation.

First, though, we review who’s at greatest risk—and what you’ll see.

Family history tops list of risk factors for PD

While PD occurs in less than 1% of the population ≥40 years of age, its prevalence increases with age, becoming significantly higher by age 60 years, with a slight predominance toward males.4

A variety of factors increase the risk of developing PD. A well-conducted meta-analysis showed that the strongest risk factor is having a family member, particularly a first-degree relative, with a history of PD or tremor.5 Repeated head injury, with or without loss of consciousness, is also a factor;5 risk increases with each occurrence.6 Other risk factors include exposure to pesticides, rural living, and exposure to well water.5

Researchers have conducted several studies regarding the effects of elevated cholesterol and hypertension on the risk of PD, but results are still without consensus.5 A study published in 2017 reported a significantly increased risk of PD associated with having hepatitis B or C, but the mechanism for the association—including whether it is a consequence of treatment—is unknown.7

Smoking and coffee drinking. Researchers have found that cigarette smoking, beer consumption, and high coffee intake are protective against PD,5 but the benefits are outweighed by the risks associated with these strategies.8 The most practical protective factors are a high dietary intake of vitamin E and increased nut consumption.9 Dietary vitamin E can be found in almonds, spinach, sweet potatoes, sunflower seeds, and avocados. Studies have not found the same benefit with vitamin E supplements.9

Dx seldom requires testing, but may take time to come into focus

Motor symptoms. The key diagnostic criterium for PD is bradykinesia with at least one of the following: muscular rigidity, resting tremor (particularly a pill-rolling tremor) that improves with purposeful function, or postural instability.2 Other physical findings may include masking of facies and speech changes, such as becoming quiet, stuttering, or speaking monotonously without inflection.1 Cogwheeling, stooped posture, and a shuffling gait or difficulty initiating gait (freezing) are all neurologic signs that point toward a PD diagnosis.2

A systematic review found that the clinical features most strongly associated with a diagnosis of PD were trouble turning in bed, a shuffling gait, tremor, difficulty opening jars, micrographia, and loss of balance.10 Typically these symptoms are asymmetric.1

Symptoms that point to other causes. Falling within the first year of symptoms is strongly associated with movement disorders other than PD—notably progressive supranuclear palsy.11 Other symptoms that point toward an alternate diagnosis include a poor response to levodopa, symmetry at the onset of symptoms, rapid progression of disease, and the absence of a tremor.11 It is important to ensure that the patient is not experiencing drug-induced symptoms as can occur with some antipsychotics and antiemetics.

Nonmotor symptoms. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in patients with PD. Up to 58% of patients experience depression, and 49% complain of anxiety.12 Hallucinations are present in many patients and are more commonly visual than auditory in nature.13 Patients experience fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and inner restlessness at higher rates than do age-matched controls.3 Research also shows that symptoms such as constipation, mood disorders, erectile dysfunction, and hyposmia may predate the onset of motor symptoms.5

Insomnia is a common symptom that is likely multifactorial in etiology. Causes to consider include motor disturbance, nocturia, reversal of sleep patterns, and reemergence of PD symptoms after a period of quiescence.14 Additionally, hypersalivation and PD dementia can develop as complications of PD.

A clinical diagnosis. Although PD can be difficult to diagnose in the early stages, the diagnosis seldom requires testing.2 A recent systematic review concluded that a clinical diagnosis of PD, when compared with pathology, was correct 74% of the time when the diagnosis was made by nonexperts and correct 84% of the time when the diagnosis was made by movement disorder experts.15

Imaging. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in ruling out other diagnoses in the differential, including vascular disease and normal pressure hydrocephalus,2 but will not reveal findings suggestive of PD.

Other diagnostic tests. A levodopa challenge can confirm PD if the diagnosis is unclear.11 In addition, an olfactory test (presenting various odors to the patient for identification) can differentiate PD from progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration; however, it will not distinguish PD from multiple system atrophy.11 If the diagnosis remains unclear, consider a consultation with a neurologist.

Treatment centers on alleviating motor symptoms

The general guiding principle of therapy (TABLE16,17) is to alleviate the motor symptoms (bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability) associated with the disease. Experts recommend that treatment commence when symptoms begin to have disabling effects or become a source of discomfort for the patient.1

Carbidopa/levodopa is still often the first choice

Multiple systematic reviews support the use of carbidopa/levodopa as first-line treatment, with the dose kept as low as possible to maintain function, while minimizing motor fluctuations (also referred to as “off” time symptoms) and dyskinesia.11,16 Initial dosing is carbidopa 25 mg/levodopa 100 mg tid. Each can be titrated up to address symptoms to a maximum daily dosing of carbidopa 200 mg/levodopa 2000 mg.17

“Off” time—the return of Parkinson symptoms when the medication’s effect wanes—can become more unpredictable and more difficult to manage as the disease advances.11 Of note: The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) says there is no improvement in the amount of off time a patient experiences by changing to a sustained-release form of carbidopa/levodopa compared with an immediate-release version.11 In addition to the on-off phenomenon, common adverse effects associated with carbidopa/levodopa include nausea, somnolence, dizziness, and headaches. Less common adverse effects include orthostatic hypotension, confusion, and hallucinations.17

Other medications for the treatment of motor symptoms

Second-line agents include dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole, and bromocriptine) and monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors (selegiline, rasagiline) (TABLE16,17). The dopamine agonists work by directly stimulating dopamine receptors, while the MAO-B inhibitors block dopamine metabolism, thus enhancing dopaminergic activity in the substantia nigra.

The pros/cons of these 2 classes. Research shows that both dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors are less effective than carbidopa/levodopa at quelling the motor symptoms associated with PD. They can, however, delay the onset of motor complications when compared with carbidopa/levodopa.16

One randomized trial found no long-term benefits to beginning treatment with a levodopa-sparing therapy; however, few patients with earlier disease onset (<60 years of age) were included in the study.18 Given the typically longer duration of their illness, there is potential for this group of patients to develop a higher rate of motor symptoms secondary to carbidopa/levodopa. Thus, considering dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors as initial therapy in patients ages <60 years may be helpful, since they typically will be taking medication longer.

Dopamine agonists. Pramipexole and ropinirole can be used as monotherapy or as an adjunct to levodopa to treat bradykinesia, postural instability, and rigidity. Bromocriptine, an ergot-derived dopamine agonist, is considered an agent of last resort because additional monitoring is required. Potential adverse effects mandate baseline testing and annual repeat testing, including measures of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and renal function and a chest x-ray.16 Consider this agent only if all second- and third-line therapies have provided inadequate control.16

Adverse effects. Dopamine agonists cause such adverse effects as orthostatic hypotension, drowsiness, dizziness, insomnia, abnormal dreams, nausea, constipation, and hallucinations. A Cochrane review notes that these adverse effects have led to higher drop-out rates than seen for carbidopa/levodopa in studies that compared the 2.19

Patients should be counseled about an additional adverse effect associated with dopamine agonists—the possible development of an impulse-control disorder, such as gambling, binge eating, or hypersexuality.1 If a patient develops any of these behaviors, promptly lower the dose of the dopamine agonist or stop the medication.16

The MAO-B inhibitors selegiline and rasagiline may also be considered for initial therapy but are more commonly used as adjunct therapy. Use of selegiline as monotherapy for PD is an off-label indication. Adverse effects for this class of agents include headache, dizziness, insomnia, nausea, and hypotension.

Add-on therapy to treat the adverse effects of primary therapy

Dopaminergic therapies come at the price of the development of off-time motor symptoms and dyskinesia.1,20 In general, these complications are managed by the addition of a dopamine agonist, MAO-B inhibitor, or a catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor (entacapone).1

Rasagiline and entacapone are a good place to start and should be offered to patients to reduce off-time symptoms, according to the AAN (a Level A recommendation based on multiple high-level studies; see here for an explanation of Strength of Recommendation).

The newest medication, safinamide, has been shown to increase “on” time by one hour per day when compared with placebo; however, it has not yet been tested against existing therapies.21 Other medications that can be considered to reduce drug-induced motor complications include pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, and tolcapone.20 Carbidopa/levodopa and bromocriptine are not recommended for the treatment of dopaminergic motor complications.20 Both sustained-release carbidopa/levodopa and bromocriptine are no longer recommended to decrease off time due to ineffectiveness.20

The only medication that has evidence for reducing dyskinesias in patients with PD is amantadine;20 however, it has no effect on other motor symptoms and should not be considered first line.16 Additionally, as an antiviral agent active against some strains of influenza, it should not be taken 2 weeks before or after receiving the influenza vaccine.

When tremor dominates …

For many patients with PD, tremor is more difficult to treat than is bradykinesia, rigidity, and gait disturbance.16 For patients with tremor-predominant PD (characterized by prominent tremor of one or more limbs and a relative lack of significant rigidity and bradykinesia), first-line treatment choices are dopamine agonists (ropinirole, pramipexole), carbidopa/levodopa, and anticholinergic medications, including benztropine and trihexyphenidyl.22 Second-line choices include clozapine, amantadine, clonazepam, and propranolol.22

Treating nonmotor symptoms

Treatment of hypersalivation should start with an evaluation by a speech pathologist. If it doesn’t improve, then adjuvant treatment with glycopyrrolate may be considered.16 Carbidopa/levodopa has the best evidence for treating periodic limb movements of sleep,14 although dopamine agonists may also be considered.16 More research is needed to find an effective therapy to improve insomnia in patients with PD, but for now consider a nighttime dose of carbidopa/levodopa or melatonin.14

Treating cognitive disorders associated with PD

Depression. Treatment of depression in patients with PD is difficult. Multiple systematic reviews have been unable to find a difference in those treated with antidepressants and those not.23 In practice, the use of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and a combination of an SSRI and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor are commonly used. Additionally, some evidence suggests that pramipexole improves depressive symptoms, but additional research is needed.1

Dementia. Dementia occurs in up to 83% of those who have had PD for more than 20 years.1 Treatment includes the use of rivastigmine (a cholinesterase inhibitor).1 Further research is needed to determine whether donepezil improves dementia symptoms in patients with PD.1

Psychotic symptoms. Query patients and their families periodically about hallucinations and delusions.16 If such symptoms are present and not well tolerated by the patient and/or family, treatment options include quetiapine and clozapine.1 While clozapine is more effective, it requires frequent hematologic monitoring due to the risk of agranulocytosis.1 And quetiapine carries a black box warning about early death. Exercise caution when prescribing these medications, particularly if a patient is cognitively impaired, and always start with low doses.1

A newer medication, pimavanserin (a second-generation antipsychotic), was recently approved by the FDA to treat hallucinations and delusions of PD psychosis, although any improvement this agent provides may not be clinically significant.24 Unlike clozapine, no additional monitoring is needed and there are no significant safety concerns with the use of pimavanserin, which makes it a reasonable first choice for hallucinations and delusions. Other neuroleptic medications should not be used as they tend to worsen Parkinson symptoms.1

Consider tai chi, physical therapy to reduce falls

One study showed that tai chi, performed for an hour twice weekly, was significantly more effective at reducing falls when compared to the same amount of resistance training and strength training, and that the benefits remained 3 months after the completion of the 24-week study.25 To date, tai chi is the only intervention that has been shown to affect fall risk.

Guidelines recommend that physical therapy be available to all patients.16 A Cochrane review performed in 2013 determined that physical therapy improves walking endurance and balance but does not affect quality of life in terms of fear of falling.26

When meds no longer help, consider deep brain stimulation as a last resort

Deep brain stimulation consists of surgical implantation of a device to deliver electrical current to a targeted area of the brain. It can be considered for patients with PD who are no longer responsive to carbidopa/levodopa, not experiencing neuropsychiatric symptoms, and are experiencing significant motor complications despite optimal medical management.14 Referral to a specialist is recommended for these patients to assess their candidacy for this procedure.

Prognosis: Largely unchanged

While medications can improve quality of life and function, PD remains a chronic and progressive disorder that is associated with significant morbidity. A study performed in 2013 showed that older age at onset, cognitive dysfunction, and motor symptoms nonresponsive to levodopa were associated with faster progression toward disability.27

Keep an eye on patients’ bone mineral density (BMD), as patients with PD tend to have lower BMD,28 a 2-fold increase in the risk of fracture for both men and women,29 and a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency.30

Also, watch for signs of infection because the most commonly cited cause of death in those with PD is pneumonia rather than a complication of the disease itself.11

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Mendoza, MD, MPH, MS, FAAFP, 777 South Clinton Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620; Michael_Mendoza@urmc.rochester.edu.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be a tough diagnosis to navigate. Patients with this neurologic movement disorder can present with a highly variable constellation of symptoms,1 ranging from the well-known tremor and bradykinesia to difficulties with activities of daily living (particularly dressing and getting out of a car2) to nonspecific symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, hyposmia, and erectile dysfunction.3

Furthermore, medications more recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have left many health care providers confused about what constitutes appropriate first-, second-, and third-line therapies, as well as add-on therapy for symptoms secondary to dopaminergic agents. What follows is a stepwise approach to managing PD that incorporates these newer therapies so that you can confidently and effectively manage patients with PD with little or no consultation.

First, though, we review who’s at greatest risk—and what you’ll see.

Family history tops list of risk factors for PD

While PD occurs in less than 1% of the population ≥40 years of age, its prevalence increases with age, becoming significantly higher by age 60 years, with a slight predominance toward males.4

A variety of factors increase the risk of developing PD. A well-conducted meta-analysis showed that the strongest risk factor is having a family member, particularly a first-degree relative, with a history of PD or tremor.5 Repeated head injury, with or without loss of consciousness, is also a factor;5 risk increases with each occurrence.6 Other risk factors include exposure to pesticides, rural living, and exposure to well water.5

Researchers have conducted several studies regarding the effects of elevated cholesterol and hypertension on the risk of PD, but results are still without consensus.5 A study published in 2017 reported a significantly increased risk of PD associated with having hepatitis B or C, but the mechanism for the association—including whether it is a consequence of treatment—is unknown.7

Smoking and coffee drinking. Researchers have found that cigarette smoking, beer consumption, and high coffee intake are protective against PD,5 but the benefits are outweighed by the risks associated with these strategies.8 The most practical protective factors are a high dietary intake of vitamin E and increased nut consumption.9 Dietary vitamin E can be found in almonds, spinach, sweet potatoes, sunflower seeds, and avocados. Studies have not found the same benefit with vitamin E supplements.9

Dx seldom requires testing, but may take time to come into focus

Motor symptoms. The key diagnostic criterium for PD is bradykinesia with at least one of the following: muscular rigidity, resting tremor (particularly a pill-rolling tremor) that improves with purposeful function, or postural instability.2 Other physical findings may include masking of facies and speech changes, such as becoming quiet, stuttering, or speaking monotonously without inflection.1 Cogwheeling, stooped posture, and a shuffling gait or difficulty initiating gait (freezing) are all neurologic signs that point toward a PD diagnosis.2

A systematic review found that the clinical features most strongly associated with a diagnosis of PD were trouble turning in bed, a shuffling gait, tremor, difficulty opening jars, micrographia, and loss of balance.10 Typically these symptoms are asymmetric.1

Symptoms that point to other causes. Falling within the first year of symptoms is strongly associated with movement disorders other than PD—notably progressive supranuclear palsy.11 Other symptoms that point toward an alternate diagnosis include a poor response to levodopa, symmetry at the onset of symptoms, rapid progression of disease, and the absence of a tremor.11 It is important to ensure that the patient is not experiencing drug-induced symptoms as can occur with some antipsychotics and antiemetics.

Nonmotor symptoms. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in patients with PD. Up to 58% of patients experience depression, and 49% complain of anxiety.12 Hallucinations are present in many patients and are more commonly visual than auditory in nature.13 Patients experience fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and inner restlessness at higher rates than do age-matched controls.3 Research also shows that symptoms such as constipation, mood disorders, erectile dysfunction, and hyposmia may predate the onset of motor symptoms.5

Insomnia is a common symptom that is likely multifactorial in etiology. Causes to consider include motor disturbance, nocturia, reversal of sleep patterns, and reemergence of PD symptoms after a period of quiescence.14 Additionally, hypersalivation and PD dementia can develop as complications of PD.

A clinical diagnosis. Although PD can be difficult to diagnose in the early stages, the diagnosis seldom requires testing.2 A recent systematic review concluded that a clinical diagnosis of PD, when compared with pathology, was correct 74% of the time when the diagnosis was made by nonexperts and correct 84% of the time when the diagnosis was made by movement disorder experts.15

Imaging. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in ruling out other diagnoses in the differential, including vascular disease and normal pressure hydrocephalus,2 but will not reveal findings suggestive of PD.

Other diagnostic tests. A levodopa challenge can confirm PD if the diagnosis is unclear.11 In addition, an olfactory test (presenting various odors to the patient for identification) can differentiate PD from progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration; however, it will not distinguish PD from multiple system atrophy.11 If the diagnosis remains unclear, consider a consultation with a neurologist.

Treatment centers on alleviating motor symptoms

The general guiding principle of therapy (TABLE16,17) is to alleviate the motor symptoms (bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability) associated with the disease. Experts recommend that treatment commence when symptoms begin to have disabling effects or become a source of discomfort for the patient.1

Carbidopa/levodopa is still often the first choice

Multiple systematic reviews support the use of carbidopa/levodopa as first-line treatment, with the dose kept as low as possible to maintain function, while minimizing motor fluctuations (also referred to as “off” time symptoms) and dyskinesia.11,16 Initial dosing is carbidopa 25 mg/levodopa 100 mg tid. Each can be titrated up to address symptoms to a maximum daily dosing of carbidopa 200 mg/levodopa 2000 mg.17

“Off” time—the return of Parkinson symptoms when the medication’s effect wanes—can become more unpredictable and more difficult to manage as the disease advances.11 Of note: The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) says there is no improvement in the amount of off time a patient experiences by changing to a sustained-release form of carbidopa/levodopa compared with an immediate-release version.11 In addition to the on-off phenomenon, common adverse effects associated with carbidopa/levodopa include nausea, somnolence, dizziness, and headaches. Less common adverse effects include orthostatic hypotension, confusion, and hallucinations.17

Other medications for the treatment of motor symptoms

Second-line agents include dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole, and bromocriptine) and monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors (selegiline, rasagiline) (TABLE16,17). The dopamine agonists work by directly stimulating dopamine receptors, while the MAO-B inhibitors block dopamine metabolism, thus enhancing dopaminergic activity in the substantia nigra.

The pros/cons of these 2 classes. Research shows that both dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors are less effective than carbidopa/levodopa at quelling the motor symptoms associated with PD. They can, however, delay the onset of motor complications when compared with carbidopa/levodopa.16

One randomized trial found no long-term benefits to beginning treatment with a levodopa-sparing therapy; however, few patients with earlier disease onset (<60 years of age) were included in the study.18 Given the typically longer duration of their illness, there is potential for this group of patients to develop a higher rate of motor symptoms secondary to carbidopa/levodopa. Thus, considering dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors as initial therapy in patients ages <60 years may be helpful, since they typically will be taking medication longer.

Dopamine agonists. Pramipexole and ropinirole can be used as monotherapy or as an adjunct to levodopa to treat bradykinesia, postural instability, and rigidity. Bromocriptine, an ergot-derived dopamine agonist, is considered an agent of last resort because additional monitoring is required. Potential adverse effects mandate baseline testing and annual repeat testing, including measures of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and renal function and a chest x-ray.16 Consider this agent only if all second- and third-line therapies have provided inadequate control.16

Adverse effects. Dopamine agonists cause such adverse effects as orthostatic hypotension, drowsiness, dizziness, insomnia, abnormal dreams, nausea, constipation, and hallucinations. A Cochrane review notes that these adverse effects have led to higher drop-out rates than seen for carbidopa/levodopa in studies that compared the 2.19

Patients should be counseled about an additional adverse effect associated with dopamine agonists—the possible development of an impulse-control disorder, such as gambling, binge eating, or hypersexuality.1 If a patient develops any of these behaviors, promptly lower the dose of the dopamine agonist or stop the medication.16

The MAO-B inhibitors selegiline and rasagiline may also be considered for initial therapy but are more commonly used as adjunct therapy. Use of selegiline as monotherapy for PD is an off-label indication. Adverse effects for this class of agents include headache, dizziness, insomnia, nausea, and hypotension.

Add-on therapy to treat the adverse effects of primary therapy

Dopaminergic therapies come at the price of the development of off-time motor symptoms and dyskinesia.1,20 In general, these complications are managed by the addition of a dopamine agonist, MAO-B inhibitor, or a catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor (entacapone).1

Rasagiline and entacapone are a good place to start and should be offered to patients to reduce off-time symptoms, according to the AAN (a Level A recommendation based on multiple high-level studies; see here for an explanation of Strength of Recommendation).

The newest medication, safinamide, has been shown to increase “on” time by one hour per day when compared with placebo; however, it has not yet been tested against existing therapies.21 Other medications that can be considered to reduce drug-induced motor complications include pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, and tolcapone.20 Carbidopa/levodopa and bromocriptine are not recommended for the treatment of dopaminergic motor complications.20 Both sustained-release carbidopa/levodopa and bromocriptine are no longer recommended to decrease off time due to ineffectiveness.20

The only medication that has evidence for reducing dyskinesias in patients with PD is amantadine;20 however, it has no effect on other motor symptoms and should not be considered first line.16 Additionally, as an antiviral agent active against some strains of influenza, it should not be taken 2 weeks before or after receiving the influenza vaccine.

When tremor dominates …

For many patients with PD, tremor is more difficult to treat than is bradykinesia, rigidity, and gait disturbance.16 For patients with tremor-predominant PD (characterized by prominent tremor of one or more limbs and a relative lack of significant rigidity and bradykinesia), first-line treatment choices are dopamine agonists (ropinirole, pramipexole), carbidopa/levodopa, and anticholinergic medications, including benztropine and trihexyphenidyl.22 Second-line choices include clozapine, amantadine, clonazepam, and propranolol.22

Treating nonmotor symptoms

Treatment of hypersalivation should start with an evaluation by a speech pathologist. If it doesn’t improve, then adjuvant treatment with glycopyrrolate may be considered.16 Carbidopa/levodopa has the best evidence for treating periodic limb movements of sleep,14 although dopamine agonists may also be considered.16 More research is needed to find an effective therapy to improve insomnia in patients with PD, but for now consider a nighttime dose of carbidopa/levodopa or melatonin.14

Treating cognitive disorders associated with PD

Depression. Treatment of depression in patients with PD is difficult. Multiple systematic reviews have been unable to find a difference in those treated with antidepressants and those not.23 In practice, the use of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and a combination of an SSRI and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor are commonly used. Additionally, some evidence suggests that pramipexole improves depressive symptoms, but additional research is needed.1

Dementia. Dementia occurs in up to 83% of those who have had PD for more than 20 years.1 Treatment includes the use of rivastigmine (a cholinesterase inhibitor).1 Further research is needed to determine whether donepezil improves dementia symptoms in patients with PD.1

Psychotic symptoms. Query patients and their families periodically about hallucinations and delusions.16 If such symptoms are present and not well tolerated by the patient and/or family, treatment options include quetiapine and clozapine.1 While clozapine is more effective, it requires frequent hematologic monitoring due to the risk of agranulocytosis.1 And quetiapine carries a black box warning about early death. Exercise caution when prescribing these medications, particularly if a patient is cognitively impaired, and always start with low doses.1

A newer medication, pimavanserin (a second-generation antipsychotic), was recently approved by the FDA to treat hallucinations and delusions of PD psychosis, although any improvement this agent provides may not be clinically significant.24 Unlike clozapine, no additional monitoring is needed and there are no significant safety concerns with the use of pimavanserin, which makes it a reasonable first choice for hallucinations and delusions. Other neuroleptic medications should not be used as they tend to worsen Parkinson symptoms.1

Consider tai chi, physical therapy to reduce falls

One study showed that tai chi, performed for an hour twice weekly, was significantly more effective at reducing falls when compared to the same amount of resistance training and strength training, and that the benefits remained 3 months after the completion of the 24-week study.25 To date, tai chi is the only intervention that has been shown to affect fall risk.

Guidelines recommend that physical therapy be available to all patients.16 A Cochrane review performed in 2013 determined that physical therapy improves walking endurance and balance but does not affect quality of life in terms of fear of falling.26

When meds no longer help, consider deep brain stimulation as a last resort

Deep brain stimulation consists of surgical implantation of a device to deliver electrical current to a targeted area of the brain. It can be considered for patients with PD who are no longer responsive to carbidopa/levodopa, not experiencing neuropsychiatric symptoms, and are experiencing significant motor complications despite optimal medical management.14 Referral to a specialist is recommended for these patients to assess their candidacy for this procedure.

Prognosis: Largely unchanged

While medications can improve quality of life and function, PD remains a chronic and progressive disorder that is associated with significant morbidity. A study performed in 2013 showed that older age at onset, cognitive dysfunction, and motor symptoms nonresponsive to levodopa were associated with faster progression toward disability.27

Keep an eye on patients’ bone mineral density (BMD), as patients with PD tend to have lower BMD,28 a 2-fold increase in the risk of fracture for both men and women,29 and a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency.30

Also, watch for signs of infection because the most commonly cited cause of death in those with PD is pneumonia rather than a complication of the disease itself.11

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Mendoza, MD, MPH, MS, FAAFP, 777 South Clinton Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620; Michael_Mendoza@urmc.rochester.edu.

1. Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896-912.

2. Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055-2066.

3. Todorova A, Jenner P, Chaudhuri K. Non-motor Parkinson’s: integral to motor Parkinson’s, yet often neglected. Pract Neurol. 2014;14:310-322.

4. Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, et al. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1583-1590.

5. Noyce AJ, Bestwick JP, Silveira-Moriyama L, et al. Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:893-901.

6. Dick FD, De Palma G, Ahmadi A, et al. Environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism: the Geoparkinson study. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:666-672.

7. Pakpoor J, Noyce A, Goldacre R, et al. Viral hepatitis and Parkinson disease: a national record-linkage study. Neurology. 2017;88:1630-1633.

8. Hern T, Newton W. Does coffee protect against the development of Parkinson disease (PD)? J Fam Pract. 2000;49:685-686.

9. Zhang SM, Hernán MA, Chen H, et al. Intakes of vitamins E and C, carotenoids, vitamin supplements, and PD risk. Neurology. 2002;59:1161-1169.

10. Rao G, Fisch L, Srinivasan S, et al. Does this patient have Parkinson disease? JAMA. 2003;289:347-353.

11. Suchowersky O, Reich S, Perlmutter J, et al. Practice Parameter: diagnosis and prognosis of new onset Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:968-975.

12. Aarsland D, Brønnick K, Ehrt U, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia: frequency, profile and associated care giver stress. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:36-42.

13. Inzelberg R, Kipervasser S, Korczyn AD. Auditory hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:533-535.

14. Zesiewicz TA, Sullivan KL, Arnulf I, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010;74:924-931.

15. Rizzo G, Copetti M, Arcuti S, et al. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2016;86:566-576.

16. National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence. Parkinson’s disease in adults. NICE guideline NG 71. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71. Accessed March 27, 2018.

17. Lexicomp version 4.0.1. Wolters Kluwer; Copyright 2017. Available at: https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home. Accessed March 27, 2018.

18. Lang AE, Marras C. Initiating dopaminergic treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2014;384:1164-1166.

19. Stowe RL, Ives NJ, Clarke C, et al. Dopamine agonist therapy in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD006564.

20. Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of Parkinson disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:983-995.

21. Schapira AH, Fox SH, Hauser RA, et al. Assessment of safety and efficacy of safinamide as a levodopa adjunct in patients with Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:216-224.

22. Marjama-Lyons J, Koller W. Tremor-predominant Parkinson’s disease. Approaches to treatment. Drugs Aging. 2000;16:273-278.

23. Price A, Rayner L, Okon-Rocha E, et al. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in neurological disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:914-923.

24. Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:533-540.

25. Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:511-519.

26. Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD002817.

27. Velseboer DC, Broeders M, Post B, et al. Prognostic factors of motor impairment, disability, and quality of life in newly diagnosed PD. Neurology. 2013;80:627-633.

28. Cronin H, Casey MC, Inderhaugh J, et al. Osteoporosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1797-1798.

29. Tan L, Wang Y, Zhou L, et al. Parkinson’s disease and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94379.

30. Evatt ML, Delong MR, Khazai N, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in patients with Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1348-1352.

1. Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896-912.

2. Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055-2066.

3. Todorova A, Jenner P, Chaudhuri K. Non-motor Parkinson’s: integral to motor Parkinson’s, yet often neglected. Pract Neurol. 2014;14:310-322.

4. Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, et al. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1583-1590.

5. Noyce AJ, Bestwick JP, Silveira-Moriyama L, et al. Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:893-901.

6. Dick FD, De Palma G, Ahmadi A, et al. Environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism: the Geoparkinson study. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:666-672.

7. Pakpoor J, Noyce A, Goldacre R, et al. Viral hepatitis and Parkinson disease: a national record-linkage study. Neurology. 2017;88:1630-1633.

8. Hern T, Newton W. Does coffee protect against the development of Parkinson disease (PD)? J Fam Pract. 2000;49:685-686.

9. Zhang SM, Hernán MA, Chen H, et al. Intakes of vitamins E and C, carotenoids, vitamin supplements, and PD risk. Neurology. 2002;59:1161-1169.

10. Rao G, Fisch L, Srinivasan S, et al. Does this patient have Parkinson disease? JAMA. 2003;289:347-353.

11. Suchowersky O, Reich S, Perlmutter J, et al. Practice Parameter: diagnosis and prognosis of new onset Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:968-975.

12. Aarsland D, Brønnick K, Ehrt U, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia: frequency, profile and associated care giver stress. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:36-42.

13. Inzelberg R, Kipervasser S, Korczyn AD. Auditory hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:533-535.

14. Zesiewicz TA, Sullivan KL, Arnulf I, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010;74:924-931.

15. Rizzo G, Copetti M, Arcuti S, et al. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2016;86:566-576.

16. National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence. Parkinson’s disease in adults. NICE guideline NG 71. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71. Accessed March 27, 2018.

17. Lexicomp version 4.0.1. Wolters Kluwer; Copyright 2017. Available at: https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home. Accessed March 27, 2018.

18. Lang AE, Marras C. Initiating dopaminergic treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2014;384:1164-1166.

19. Stowe RL, Ives NJ, Clarke C, et al. Dopamine agonist therapy in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD006564.

20. Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of Parkinson disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:983-995.

21. Schapira AH, Fox SH, Hauser RA, et al. Assessment of safety and efficacy of safinamide as a levodopa adjunct in patients with Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:216-224.

22. Marjama-Lyons J, Koller W. Tremor-predominant Parkinson’s disease. Approaches to treatment. Drugs Aging. 2000;16:273-278.

23. Price A, Rayner L, Okon-Rocha E, et al. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in neurological disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:914-923.

24. Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:533-540.

25. Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:511-519.

26. Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD002817.

27. Velseboer DC, Broeders M, Post B, et al. Prognostic factors of motor impairment, disability, and quality of life in newly diagnosed PD. Neurology. 2013;80:627-633.

28. Cronin H, Casey MC, Inderhaugh J, et al. Osteoporosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1797-1798.

29. Tan L, Wang Y, Zhou L, et al. Parkinson’s disease and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94379.

30. Evatt ML, Delong MR, Khazai N, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in patients with Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1348-1352.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2018;67(5):276-279,284-286.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Use carbidopa/levodopa as first-line treatment for most patients with Parkinson's disease. A

› Prescribe rasagiline or entacapone for the treatment of motor fluctuations secondary to dopaminergic therapies. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series