User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

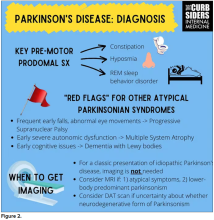

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

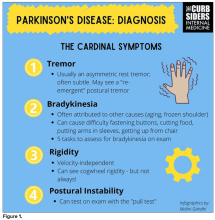

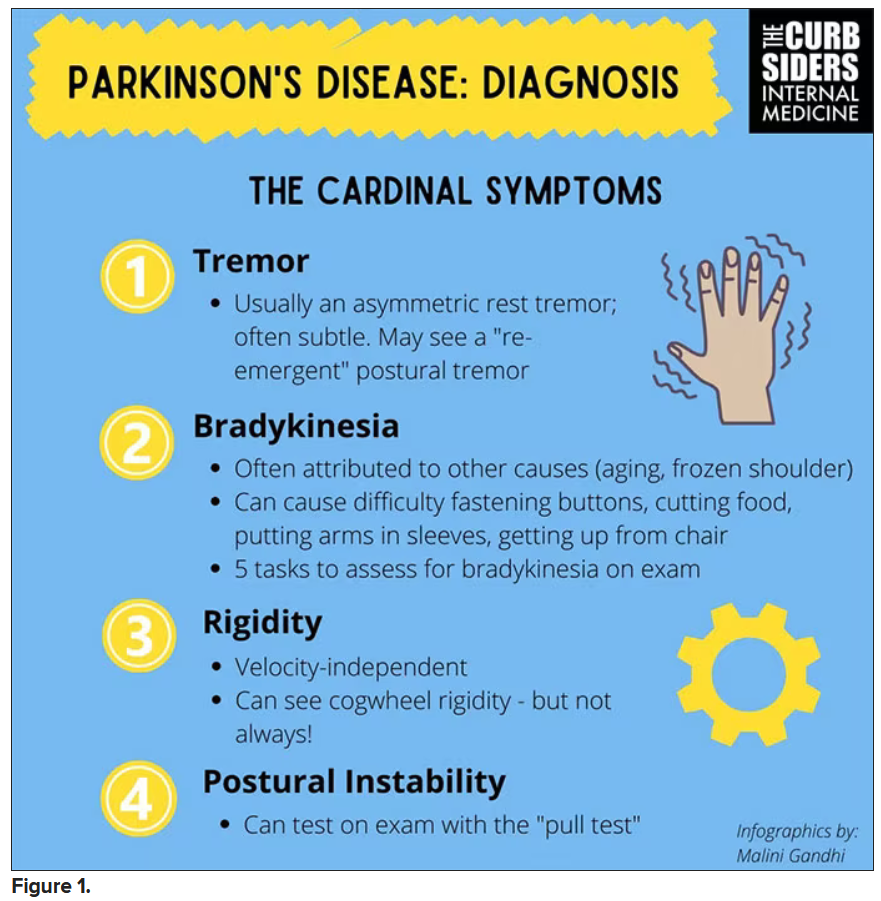

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

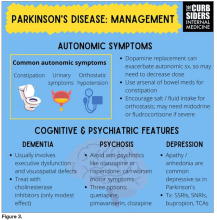

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.