User login

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

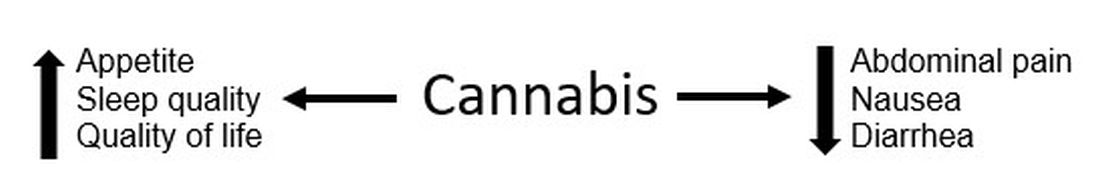

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion

These cases outline the challenges that providers face when managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when a patient would like to either substitute or incorporate cannabis into their treatment plan. Studies have shown a high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with IBD. With the restrictions surrounding the use of cannabis – either medically or recreationally – being liberalized in many states, these conversations are likely to become more frequent in your practice. However, one of the first challenges that providers face surrounding cannabis is that many patients who use cannabis do not disclose use to their health care team for fear of being judged negatively. In addition, many providers do not routinely ask about cannabis use during office visits. This might be directly related to being unprepared to have a knowledge-based discussion on the risks and benefits of cannabis use in IBD, with the same confidence present during discussion of biologic therapies.

For background, Cannabis sativa (cannabis) is composed of hundreds of phytocannabinoids, the two most common are THC and CBD. These cannabinoids act at the endocannabinoid receptors, which are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and immune cells/tissues, and help explain the clinical changes experienced by cannabis users. Both THC and CBD have been studied in varying doses and routes of administration in patients with IBD, making it challenging to translate into real-world recommendations for patients. Some of the most common reported benefits of cannabis use (particularly in an IBD population) are improvement in pain, diarrhea, nausea, and joint pain. Some studies have shown overall improvement in quality of life (Figure 1).

Some common questions that arise surrounding cannabis use in IBD patients include:

1. Is it possible to stop traditional medical therapy and replace it with cannabis therapy?

No studies have directly addressed this exact question. The small studies, both randomized controlled trials and retrospective ones, have studied the effects of cannabis as adjuvant therapy only. None of the data available to date suggest that cannabis has any anti-inflammatory properties with absence of improvement in biomarkers or endoscopic measures of inflammation. In effect, any attempt to discontinue standard therapy with substitution of cannabis-based therapy should be seen as no different than simply discontinuing standard therapy. There exists the argument that – among those with moderate to severe disease – cannabis might suppress the investigation of mild symptoms which may herald a flare of disease, thus lulling the patient into a state of false stability. We do not advocate the substitution of cannabis products in place of standard medical therapy.

2. Is there a role for cannabis as adjuvant therapy in patients with IBD?

Studies to date have included only symptomatic patients with objective evidence of inflammation and assessed clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic endpoints. In Crohn’s disease, two studies showed no improvement in clinical remission rates but showed improvement in clinical response; a third study showed both improvement in clinical remission/response as well as improved quality of life. No study showed a change in disease markers of activity including CRP, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopic scoring. In one study, all patients relapsed shortly after cannabis discontinuation suggesting that, while there was benefit in symptom control, there was no improvement of the underlying chronic inflammation.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, there were two studies. One study showed no improvement and high rates of intolerance in the treatment group, while the other study reported improved disease activity but no objective improvement. The variation in results between disease states and between studies might be because of cannabis formulations. In patients with persistent symptoms despite current medical therapy, there might be a role in those patients for adjuvant therapy for improvement symptom control but not disease control. Optimization of medical therapy would still be indicated.

3. What dose and formulation of cannabis should I recommend to a patient as adjuvant therapy?

This is an excellent question and one that unfortunately we do not have the answer to. As mentioned previously, the studies have looked at varying formulations (THC alone, CBD:THC with varying percentages of THC, CBD alone) and varying routes of administration (sublingual, oral, inhalation). The IBD studies looking at CBD-alone formulations lacked clinical efficacy. In states where cannabis products have been accessible to IBD patients, no data on the product type (THC:CBD), method of administration, or prescriber preferences have been published.

4. What risks should I advise my patients about with cannabis use?

The challenge is that we don’t have large population-based studies in IBD looking at long-term risks of cannabis use. However, in the small RCT studies there were minimal reported side effects and no major adverse events over 8-10 weeks. Larger IBD population-based studies have shown that cannabis users were more likely to discontinue traditional medical therapy, and there is an increased risk for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Larger studies in non-IBD patients have shown risk for addiction to other substances, diminished life achievement, increased motor vehicle accidents, chronic bronchitis, psychiatric disturbances and cannabis dependence, and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (with an uncanny presentation resembling Crohn’s disease flare with partial small bowel obstruction). Patients should also be advised about legal implications of use (given its continued classification as a federal schedule 1 drug), possible drug interactions, and special considerations in pediatric patients (increased risk of addiction), elderly patients (increased risk of neuropsychological effects), and during pregnancy (with national obstetric society guidelines warning against use because of fetal exposure and increased risk of stillbirth).

5. What are the legal implications for providers? Patients?

As of July 2020, cannabis is available for recreational use in 12 states, for medicinal use in 28 states, and illegal in 11 states. So the answer really depends on what state the patient lives in. As a provider who might certify patients (in some medicinal states) or recommend cannabis to patients, you should consider legal and licensing implications. Again, this might vary state to state, and you should also take into account federal status. Providers acting in compliance with state laws are unlikely to have federal consequences. However, remember that malpractice insurance only covers FDA-approved medical therapies. Patients should be advised to consider the potential (although highly unlikely) to face federal prosecution and implications of use for employment, school, camp, or travel, and driving restrictions.

Take home points

- Inquire about cannabis to start the conversation.

- Know your state’s legalization status surrounding cannabis.

- Patients with IBD report improvement in symptoms and quality of life with adjuvant cannabis use; however, there is no change in disease activity.

- Encourage your patients to continue and optimize their maintenance therapy.

- Educate your patients about the legal considerations and known risks.

In conclusion, the use of cannabis in IBD patients has increased in recent years. It is important to be able to discuss the risks and benefits of use with your IBD patients. Focus on the lack of data showing that cannabis improves disease activity, and has shown benefit only in improving IBD-associated symptoms. In some patients there might be a role for adjuvant cannabis therapy to improve overall symptom control and quality of life.

Dr. Kinnucan is an assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Swaminath is an associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Lenox Hill Hospital, Northwell Health, New York.

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

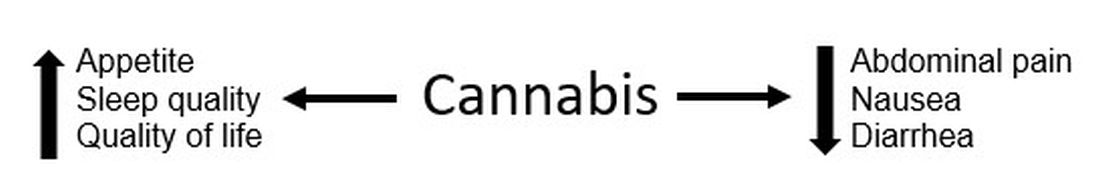

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion

These cases outline the challenges that providers face when managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when a patient would like to either substitute or incorporate cannabis into their treatment plan. Studies have shown a high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with IBD. With the restrictions surrounding the use of cannabis – either medically or recreationally – being liberalized in many states, these conversations are likely to become more frequent in your practice. However, one of the first challenges that providers face surrounding cannabis is that many patients who use cannabis do not disclose use to their health care team for fear of being judged negatively. In addition, many providers do not routinely ask about cannabis use during office visits. This might be directly related to being unprepared to have a knowledge-based discussion on the risks and benefits of cannabis use in IBD, with the same confidence present during discussion of biologic therapies.

For background, Cannabis sativa (cannabis) is composed of hundreds of phytocannabinoids, the two most common are THC and CBD. These cannabinoids act at the endocannabinoid receptors, which are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and immune cells/tissues, and help explain the clinical changes experienced by cannabis users. Both THC and CBD have been studied in varying doses and routes of administration in patients with IBD, making it challenging to translate into real-world recommendations for patients. Some of the most common reported benefits of cannabis use (particularly in an IBD population) are improvement in pain, diarrhea, nausea, and joint pain. Some studies have shown overall improvement in quality of life (Figure 1).

Some common questions that arise surrounding cannabis use in IBD patients include:

1. Is it possible to stop traditional medical therapy and replace it with cannabis therapy?

No studies have directly addressed this exact question. The small studies, both randomized controlled trials and retrospective ones, have studied the effects of cannabis as adjuvant therapy only. None of the data available to date suggest that cannabis has any anti-inflammatory properties with absence of improvement in biomarkers or endoscopic measures of inflammation. In effect, any attempt to discontinue standard therapy with substitution of cannabis-based therapy should be seen as no different than simply discontinuing standard therapy. There exists the argument that – among those with moderate to severe disease – cannabis might suppress the investigation of mild symptoms which may herald a flare of disease, thus lulling the patient into a state of false stability. We do not advocate the substitution of cannabis products in place of standard medical therapy.

2. Is there a role for cannabis as adjuvant therapy in patients with IBD?

Studies to date have included only symptomatic patients with objective evidence of inflammation and assessed clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic endpoints. In Crohn’s disease, two studies showed no improvement in clinical remission rates but showed improvement in clinical response; a third study showed both improvement in clinical remission/response as well as improved quality of life. No study showed a change in disease markers of activity including CRP, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopic scoring. In one study, all patients relapsed shortly after cannabis discontinuation suggesting that, while there was benefit in symptom control, there was no improvement of the underlying chronic inflammation.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, there were two studies. One study showed no improvement and high rates of intolerance in the treatment group, while the other study reported improved disease activity but no objective improvement. The variation in results between disease states and between studies might be because of cannabis formulations. In patients with persistent symptoms despite current medical therapy, there might be a role in those patients for adjuvant therapy for improvement symptom control but not disease control. Optimization of medical therapy would still be indicated.

3. What dose and formulation of cannabis should I recommend to a patient as adjuvant therapy?

This is an excellent question and one that unfortunately we do not have the answer to. As mentioned previously, the studies have looked at varying formulations (THC alone, CBD:THC with varying percentages of THC, CBD alone) and varying routes of administration (sublingual, oral, inhalation). The IBD studies looking at CBD-alone formulations lacked clinical efficacy. In states where cannabis products have been accessible to IBD patients, no data on the product type (THC:CBD), method of administration, or prescriber preferences have been published.

4. What risks should I advise my patients about with cannabis use?

The challenge is that we don’t have large population-based studies in IBD looking at long-term risks of cannabis use. However, in the small RCT studies there were minimal reported side effects and no major adverse events over 8-10 weeks. Larger IBD population-based studies have shown that cannabis users were more likely to discontinue traditional medical therapy, and there is an increased risk for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Larger studies in non-IBD patients have shown risk for addiction to other substances, diminished life achievement, increased motor vehicle accidents, chronic bronchitis, psychiatric disturbances and cannabis dependence, and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (with an uncanny presentation resembling Crohn’s disease flare with partial small bowel obstruction). Patients should also be advised about legal implications of use (given its continued classification as a federal schedule 1 drug), possible drug interactions, and special considerations in pediatric patients (increased risk of addiction), elderly patients (increased risk of neuropsychological effects), and during pregnancy (with national obstetric society guidelines warning against use because of fetal exposure and increased risk of stillbirth).

5. What are the legal implications for providers? Patients?

As of July 2020, cannabis is available for recreational use in 12 states, for medicinal use in 28 states, and illegal in 11 states. So the answer really depends on what state the patient lives in. As a provider who might certify patients (in some medicinal states) or recommend cannabis to patients, you should consider legal and licensing implications. Again, this might vary state to state, and you should also take into account federal status. Providers acting in compliance with state laws are unlikely to have federal consequences. However, remember that malpractice insurance only covers FDA-approved medical therapies. Patients should be advised to consider the potential (although highly unlikely) to face federal prosecution and implications of use for employment, school, camp, or travel, and driving restrictions.

Take home points

- Inquire about cannabis to start the conversation.

- Know your state’s legalization status surrounding cannabis.

- Patients with IBD report improvement in symptoms and quality of life with adjuvant cannabis use; however, there is no change in disease activity.

- Encourage your patients to continue and optimize their maintenance therapy.

- Educate your patients about the legal considerations and known risks.

In conclusion, the use of cannabis in IBD patients has increased in recent years. It is important to be able to discuss the risks and benefits of use with your IBD patients. Focus on the lack of data showing that cannabis improves disease activity, and has shown benefit only in improving IBD-associated symptoms. In some patients there might be a role for adjuvant cannabis therapy to improve overall symptom control and quality of life.

Dr. Kinnucan is an assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Swaminath is an associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Lenox Hill Hospital, Northwell Health, New York.

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

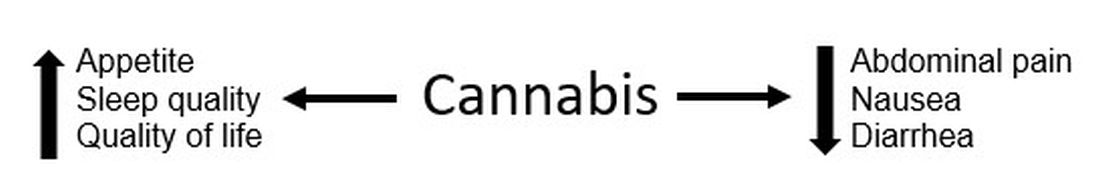

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion

These cases outline the challenges that providers face when managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when a patient would like to either substitute or incorporate cannabis into their treatment plan. Studies have shown a high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with IBD. With the restrictions surrounding the use of cannabis – either medically or recreationally – being liberalized in many states, these conversations are likely to become more frequent in your practice. However, one of the first challenges that providers face surrounding cannabis is that many patients who use cannabis do not disclose use to their health care team for fear of being judged negatively. In addition, many providers do not routinely ask about cannabis use during office visits. This might be directly related to being unprepared to have a knowledge-based discussion on the risks and benefits of cannabis use in IBD, with the same confidence present during discussion of biologic therapies.

For background, Cannabis sativa (cannabis) is composed of hundreds of phytocannabinoids, the two most common are THC and CBD. These cannabinoids act at the endocannabinoid receptors, which are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and immune cells/tissues, and help explain the clinical changes experienced by cannabis users. Both THC and CBD have been studied in varying doses and routes of administration in patients with IBD, making it challenging to translate into real-world recommendations for patients. Some of the most common reported benefits of cannabis use (particularly in an IBD population) are improvement in pain, diarrhea, nausea, and joint pain. Some studies have shown overall improvement in quality of life (Figure 1).

Some common questions that arise surrounding cannabis use in IBD patients include:

1. Is it possible to stop traditional medical therapy and replace it with cannabis therapy?

No studies have directly addressed this exact question. The small studies, both randomized controlled trials and retrospective ones, have studied the effects of cannabis as adjuvant therapy only. None of the data available to date suggest that cannabis has any anti-inflammatory properties with absence of improvement in biomarkers or endoscopic measures of inflammation. In effect, any attempt to discontinue standard therapy with substitution of cannabis-based therapy should be seen as no different than simply discontinuing standard therapy. There exists the argument that – among those with moderate to severe disease – cannabis might suppress the investigation of mild symptoms which may herald a flare of disease, thus lulling the patient into a state of false stability. We do not advocate the substitution of cannabis products in place of standard medical therapy.

2. Is there a role for cannabis as adjuvant therapy in patients with IBD?

Studies to date have included only symptomatic patients with objective evidence of inflammation and assessed clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic endpoints. In Crohn’s disease, two studies showed no improvement in clinical remission rates but showed improvement in clinical response; a third study showed both improvement in clinical remission/response as well as improved quality of life. No study showed a change in disease markers of activity including CRP, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopic scoring. In one study, all patients relapsed shortly after cannabis discontinuation suggesting that, while there was benefit in symptom control, there was no improvement of the underlying chronic inflammation.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, there were two studies. One study showed no improvement and high rates of intolerance in the treatment group, while the other study reported improved disease activity but no objective improvement. The variation in results between disease states and between studies might be because of cannabis formulations. In patients with persistent symptoms despite current medical therapy, there might be a role in those patients for adjuvant therapy for improvement symptom control but not disease control. Optimization of medical therapy would still be indicated.

3. What dose and formulation of cannabis should I recommend to a patient as adjuvant therapy?

This is an excellent question and one that unfortunately we do not have the answer to. As mentioned previously, the studies have looked at varying formulations (THC alone, CBD:THC with varying percentages of THC, CBD alone) and varying routes of administration (sublingual, oral, inhalation). The IBD studies looking at CBD-alone formulations lacked clinical efficacy. In states where cannabis products have been accessible to IBD patients, no data on the product type (THC:CBD), method of administration, or prescriber preferences have been published.

4. What risks should I advise my patients about with cannabis use?

The challenge is that we don’t have large population-based studies in IBD looking at long-term risks of cannabis use. However, in the small RCT studies there were minimal reported side effects and no major adverse events over 8-10 weeks. Larger IBD population-based studies have shown that cannabis users were more likely to discontinue traditional medical therapy, and there is an increased risk for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Larger studies in non-IBD patients have shown risk for addiction to other substances, diminished life achievement, increased motor vehicle accidents, chronic bronchitis, psychiatric disturbances and cannabis dependence, and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (with an uncanny presentation resembling Crohn’s disease flare with partial small bowel obstruction). Patients should also be advised about legal implications of use (given its continued classification as a federal schedule 1 drug), possible drug interactions, and special considerations in pediatric patients (increased risk of addiction), elderly patients (increased risk of neuropsychological effects), and during pregnancy (with national obstetric society guidelines warning against use because of fetal exposure and increased risk of stillbirth).

5. What are the legal implications for providers? Patients?

As of July 2020, cannabis is available for recreational use in 12 states, for medicinal use in 28 states, and illegal in 11 states. So the answer really depends on what state the patient lives in. As a provider who might certify patients (in some medicinal states) or recommend cannabis to patients, you should consider legal and licensing implications. Again, this might vary state to state, and you should also take into account federal status. Providers acting in compliance with state laws are unlikely to have federal consequences. However, remember that malpractice insurance only covers FDA-approved medical therapies. Patients should be advised to consider the potential (although highly unlikely) to face federal prosecution and implications of use for employment, school, camp, or travel, and driving restrictions.

Take home points

- Inquire about cannabis to start the conversation.

- Know your state’s legalization status surrounding cannabis.

- Patients with IBD report improvement in symptoms and quality of life with adjuvant cannabis use; however, there is no change in disease activity.

- Encourage your patients to continue and optimize their maintenance therapy.

- Educate your patients about the legal considerations and known risks.

In conclusion, the use of cannabis in IBD patients has increased in recent years. It is important to be able to discuss the risks and benefits of use with your IBD patients. Focus on the lack of data showing that cannabis improves disease activity, and has shown benefit only in improving IBD-associated symptoms. In some patients there might be a role for adjuvant cannabis therapy to improve overall symptom control and quality of life.

Dr. Kinnucan is an assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Swaminath is an associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Lenox Hill Hospital, Northwell Health, New York.