User login

Increase in message volume begs the question: ‘Should we be compensated for our time?’

The American Gastroenterological Association and other gastrointestinal-specific organizations have excellent resources available to members that focus on optimizing reimbursement in your clinical and endoscopic practice.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency (PHE), many previously noncovered services were now covered under rules of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. During the pandemic, patient portal messages increased by 157%, meaning more work for health care teams, negatively impacting physician satisfaction, and increasing burnout.1 Medical burnout has been associated with increased time spent on electronic health records, with some subspeciality gastroenterology (GI) groups having a high EHR burden, according to a recently published article in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.2

This topic is a timely discussion as several large health systems have implemented processes to bill for non–face-to-face services (termed “asynchronous care”), some of which have not been well received in the lay media. It is important to note that despite these implementations, studies have shown only 1% of all incoming portal messages would meet criteria to be submitted for reimbursement. This impact might be slightly higher in chronic care management practices.

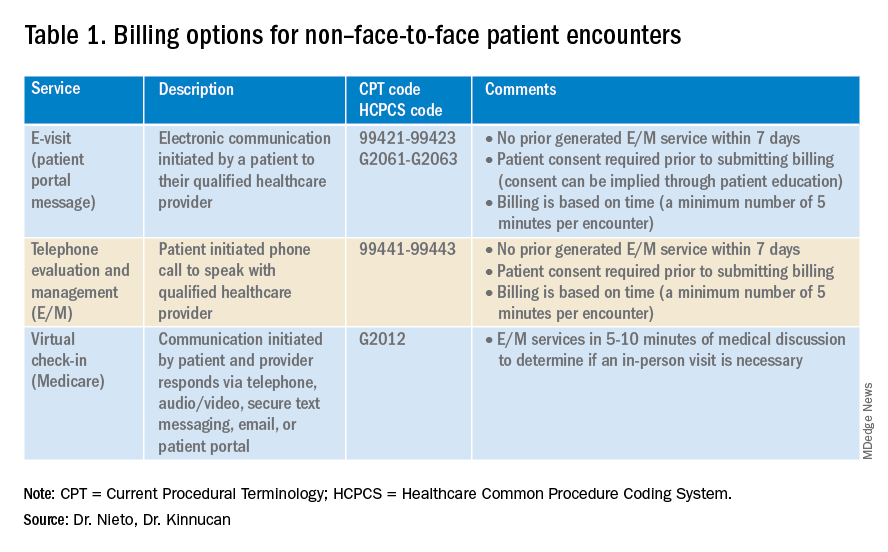

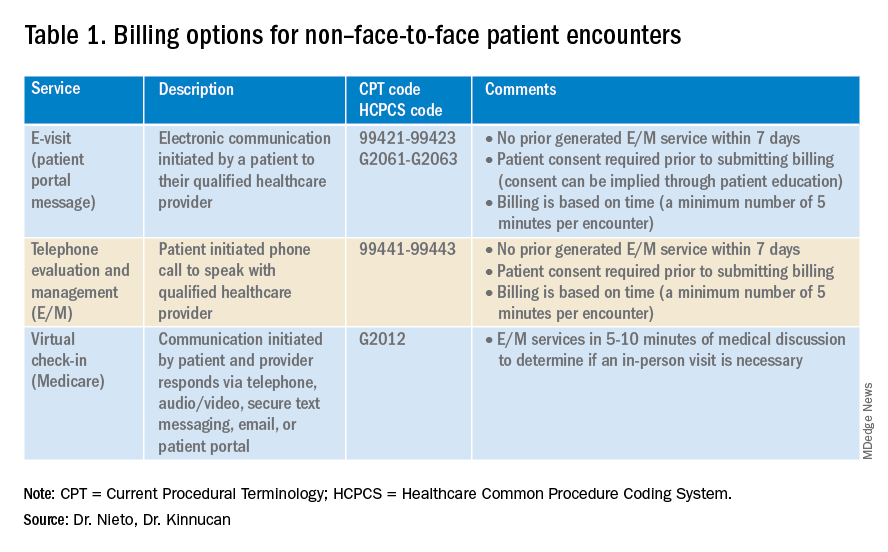

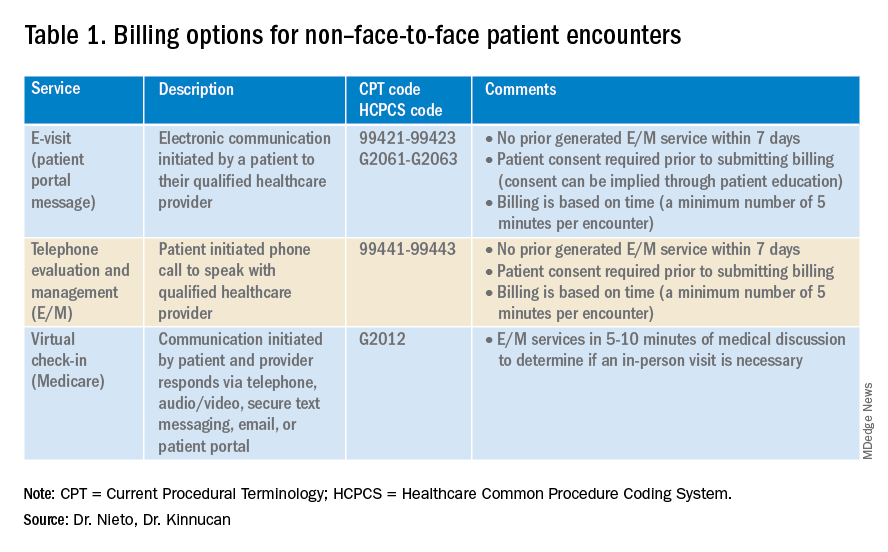

Providers and practices have several options when considering billing for non–face-to-face encounters, which we outline in Table 1.3

The focus of this article will be to review the more common non–face-to-face evaluation and management services, such as telephone E/M (patient phone call) and e-visits (patient portal messages) as these have recently generated the most interest and discussion amongst health care providers.

Telemedicine after COVID-19 pandemic

During the beginning of the pandemic, a web-based survey study found that almost all providers in GI practices implemented some form of telemedicine to continue to provide care for patients, compared to 32% prior to the pandemic.4,5 The high demand and essential requirement for telehealth evaluation facilitated its reimbursement, eliminating the primary barrier to previous use.6

One of the new covered benefits by CMS was asynchronous telehealth care.7 The PHE ended in May 2023, and since then a qualified health care provider (QHCP) does not have the full flexibility to deliver telemedicine services across state lines. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has considered some telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 PHE and many of those will be extended, at least through 2024.8 As during the pandemic, where the U.S. national payer network (CMS, state Medicaid, and private payers) and state health agencies assisted to ensure patients get the care they need by authorizing providers to be compensated for non–face-to-face services, we believe this service will continue to be part of our clinical practice.

We recommend you stay informed about local and federal laws, regulations, and alternatives for reimbursement as they may be modified at the beginning of a new calendar year. Remember, you can always talk with your revenue cycle team to clarify any query.

Telephone evaluation and management services

The patient requests to speak with you.

Telephone evaluation and management services became more widely used after the pandemic and were recognized by CMS as a covered medical service under PHE. As outlined in Table 1, there are associated codes with this service and it can only apply to an established patient in your practice. The cumulative time spent over a 7-day period without generating an immediate follow-up visit could qualify for this CPT code. However, for a patient with a high-complexity diagnosis and/or decisions being made about care, it might be better to consider a virtual office visit as this would value the complex care at a higher level than the time spent during the telephone E/M encounter.

A common question comes up: Can my nurse or support team bill for telephone care? No, only QHCP can, which means physicians and advanced practice providers can bill for this E/M service, and it does not include time spent by other members of clinical staff in patient care. However, there are CPT codes for chronic care management, which is not covered in this article.

Virtual evaluation and management services

You respond to a patient-initiated portal message.

Patient portal messages increased exponentially during the pandemic with 2.5 more minutes spent per message, resulting in more EHR work by practitioners, compared with prior to the pandemic. One study showed an immediate postpandemic increase in EHR patient-initiated messages with no return to prepandemic baseline.1

Although studies evaluating postpandemic telemedicine services are needed, we believe that this trend will continue, and for this reason, it is important to create sustainable workflows to continue to provide this patient driven avenue of care.9

E-visits are asynchronous patient or guardian portal messages that require a minimum of 5 minutes to provide medical decision-making without prior E/M services in the last 7 days. To obtain reimbursement for this service, it cannot be initiated by the provider, and patient consent must be obtained. Documentation should include this information and the time spent in the encounter. The associated CPT codes with this e-service are outlined in Table 1.

A common question is, “Are there additional codes I should use if a portal message E/M visit lasts more than 30 minutes?” No. If an e-visit lasts more than 30 minutes, the QHCP should bill the CPT code 99423. However, we would advise that, if this care requires more than 30 minutes, then either virtual or face-to-face E/M be considered for the optimal reimbursement for provider time spent. Another common question is around consent for services, and we advise providers to review this requirement with their compliance colleagues as each institution has different policies.

Virtual check-in

Medicare also covers brief communication technology–based services also known as virtual check-ins, where patients can communicate with their provider after having established care. During this brief conversation that can be via telephone, audio/video, secure text messaging, email, or patient portal, providers will determine if an in-person visit is necessary. CMS has designed G codes for these virtual check-ins that are from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Two codes are available for this E/M service: G2012, which is outlined in Table 1, and G2010, which covers the evaluation of images and/or recorded videos. In order to be reimbursed for a G2010 code, providers need at least a 5-minute response to make a clinical determination or give the patient a medical impression.

Patient satisfaction, physician well-being and quality of care outcomes

Large health care systems like Kaiser Permanente implemented secure message patient-physician communication (the patient portal) even before the pandemic, showing promising results in 2010 with reduction in office visits, improvement in measurable quality outcomes, and high level of patient satisfaction.10 Post pandemic, several large health care centers opted to announce the billing implementation for patient-initiated portal messages.11 A focus was placed on educating their patients about when a message will and will not be billed. Using this type of strategy can help to improve patient awareness about potential billing without affecting patient satisfaction and care outcomes. Studies have shown the EHR has contributed to physician burnout and some physicians reducing their clinical time or leaving medicine; a reduction in messaging might have a positive impact on physician well-being.

The challenge is that medical billing is not routinely included as a curriculum topic in many residency and fellowship programs; however, trainees are part of E/M services and have limited knowledge of billing processes. Unfortunately, at this time, trainees cannot submit for reimbursement for asynchronous care as described above. We hope that this brief article will help junior gastroenterologists optimize their outpatient billing practices.

Dr. Nieto is an internal medicine chief resident with WellStar Cobb Medical Center, Austell, Ga. Dr. Kinnucan is a gastroenterologist with Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose for this article. The authors certify that no financial and grant support has been received for this article.

References

1. Holmgren AJ et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021 Dec 9. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab268.

2. Bali AS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Apr 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002254.

3. AAFP. Family Physician. “Coding Scenario: Coding for Virtual-Digital Visits”

4. Keihanian T. et al. Telehealth Utilization in Gastroenterology Clinics Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Clinical Practice and Gastroenterology Training. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jun 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.040.

5. Lewin S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Oct 21. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa140.

6. Perisetti A and H Goyal. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Mar 3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-06874-x.

7. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Medicaid and Medicare billing for asynchronous telehealth. Updated: 2022 May 4.

8. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency. Last updated: 2023 Jan 23.

9. Fox B and Sizemore JO. Telehealth: Fad or the future. Epic Health Research Network. 2020 Aug 18.

10. Baer D. Patient-physician e-mail communication: the kaiser permanente experience. J Oncol Pract. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000323.

11. Myclevelandclinic.org. MyChart Messaging.

12. Sinsky CA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Aug 29. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07766-0.

The American Gastroenterological Association and other gastrointestinal-specific organizations have excellent resources available to members that focus on optimizing reimbursement in your clinical and endoscopic practice.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency (PHE), many previously noncovered services were now covered under rules of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. During the pandemic, patient portal messages increased by 157%, meaning more work for health care teams, negatively impacting physician satisfaction, and increasing burnout.1 Medical burnout has been associated with increased time spent on electronic health records, with some subspeciality gastroenterology (GI) groups having a high EHR burden, according to a recently published article in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.2

This topic is a timely discussion as several large health systems have implemented processes to bill for non–face-to-face services (termed “asynchronous care”), some of which have not been well received in the lay media. It is important to note that despite these implementations, studies have shown only 1% of all incoming portal messages would meet criteria to be submitted for reimbursement. This impact might be slightly higher in chronic care management practices.

Providers and practices have several options when considering billing for non–face-to-face encounters, which we outline in Table 1.3

The focus of this article will be to review the more common non–face-to-face evaluation and management services, such as telephone E/M (patient phone call) and e-visits (patient portal messages) as these have recently generated the most interest and discussion amongst health care providers.

Telemedicine after COVID-19 pandemic

During the beginning of the pandemic, a web-based survey study found that almost all providers in GI practices implemented some form of telemedicine to continue to provide care for patients, compared to 32% prior to the pandemic.4,5 The high demand and essential requirement for telehealth evaluation facilitated its reimbursement, eliminating the primary barrier to previous use.6

One of the new covered benefits by CMS was asynchronous telehealth care.7 The PHE ended in May 2023, and since then a qualified health care provider (QHCP) does not have the full flexibility to deliver telemedicine services across state lines. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has considered some telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 PHE and many of those will be extended, at least through 2024.8 As during the pandemic, where the U.S. national payer network (CMS, state Medicaid, and private payers) and state health agencies assisted to ensure patients get the care they need by authorizing providers to be compensated for non–face-to-face services, we believe this service will continue to be part of our clinical practice.

We recommend you stay informed about local and federal laws, regulations, and alternatives for reimbursement as they may be modified at the beginning of a new calendar year. Remember, you can always talk with your revenue cycle team to clarify any query.

Telephone evaluation and management services

The patient requests to speak with you.

Telephone evaluation and management services became more widely used after the pandemic and were recognized by CMS as a covered medical service under PHE. As outlined in Table 1, there are associated codes with this service and it can only apply to an established patient in your practice. The cumulative time spent over a 7-day period without generating an immediate follow-up visit could qualify for this CPT code. However, for a patient with a high-complexity diagnosis and/or decisions being made about care, it might be better to consider a virtual office visit as this would value the complex care at a higher level than the time spent during the telephone E/M encounter.

A common question comes up: Can my nurse or support team bill for telephone care? No, only QHCP can, which means physicians and advanced practice providers can bill for this E/M service, and it does not include time spent by other members of clinical staff in patient care. However, there are CPT codes for chronic care management, which is not covered in this article.

Virtual evaluation and management services

You respond to a patient-initiated portal message.

Patient portal messages increased exponentially during the pandemic with 2.5 more minutes spent per message, resulting in more EHR work by practitioners, compared with prior to the pandemic. One study showed an immediate postpandemic increase in EHR patient-initiated messages with no return to prepandemic baseline.1

Although studies evaluating postpandemic telemedicine services are needed, we believe that this trend will continue, and for this reason, it is important to create sustainable workflows to continue to provide this patient driven avenue of care.9

E-visits are asynchronous patient or guardian portal messages that require a minimum of 5 minutes to provide medical decision-making without prior E/M services in the last 7 days. To obtain reimbursement for this service, it cannot be initiated by the provider, and patient consent must be obtained. Documentation should include this information and the time spent in the encounter. The associated CPT codes with this e-service are outlined in Table 1.

A common question is, “Are there additional codes I should use if a portal message E/M visit lasts more than 30 minutes?” No. If an e-visit lasts more than 30 minutes, the QHCP should bill the CPT code 99423. However, we would advise that, if this care requires more than 30 minutes, then either virtual or face-to-face E/M be considered for the optimal reimbursement for provider time spent. Another common question is around consent for services, and we advise providers to review this requirement with their compliance colleagues as each institution has different policies.

Virtual check-in

Medicare also covers brief communication technology–based services also known as virtual check-ins, where patients can communicate with their provider after having established care. During this brief conversation that can be via telephone, audio/video, secure text messaging, email, or patient portal, providers will determine if an in-person visit is necessary. CMS has designed G codes for these virtual check-ins that are from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Two codes are available for this E/M service: G2012, which is outlined in Table 1, and G2010, which covers the evaluation of images and/or recorded videos. In order to be reimbursed for a G2010 code, providers need at least a 5-minute response to make a clinical determination or give the patient a medical impression.

Patient satisfaction, physician well-being and quality of care outcomes

Large health care systems like Kaiser Permanente implemented secure message patient-physician communication (the patient portal) even before the pandemic, showing promising results in 2010 with reduction in office visits, improvement in measurable quality outcomes, and high level of patient satisfaction.10 Post pandemic, several large health care centers opted to announce the billing implementation for patient-initiated portal messages.11 A focus was placed on educating their patients about when a message will and will not be billed. Using this type of strategy can help to improve patient awareness about potential billing without affecting patient satisfaction and care outcomes. Studies have shown the EHR has contributed to physician burnout and some physicians reducing their clinical time or leaving medicine; a reduction in messaging might have a positive impact on physician well-being.

The challenge is that medical billing is not routinely included as a curriculum topic in many residency and fellowship programs; however, trainees are part of E/M services and have limited knowledge of billing processes. Unfortunately, at this time, trainees cannot submit for reimbursement for asynchronous care as described above. We hope that this brief article will help junior gastroenterologists optimize their outpatient billing practices.

Dr. Nieto is an internal medicine chief resident with WellStar Cobb Medical Center, Austell, Ga. Dr. Kinnucan is a gastroenterologist with Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose for this article. The authors certify that no financial and grant support has been received for this article.

References

1. Holmgren AJ et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021 Dec 9. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab268.

2. Bali AS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Apr 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002254.

3. AAFP. Family Physician. “Coding Scenario: Coding for Virtual-Digital Visits”

4. Keihanian T. et al. Telehealth Utilization in Gastroenterology Clinics Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Clinical Practice and Gastroenterology Training. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jun 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.040.

5. Lewin S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Oct 21. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa140.

6. Perisetti A and H Goyal. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Mar 3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-06874-x.

7. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Medicaid and Medicare billing for asynchronous telehealth. Updated: 2022 May 4.

8. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency. Last updated: 2023 Jan 23.

9. Fox B and Sizemore JO. Telehealth: Fad or the future. Epic Health Research Network. 2020 Aug 18.

10. Baer D. Patient-physician e-mail communication: the kaiser permanente experience. J Oncol Pract. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000323.

11. Myclevelandclinic.org. MyChart Messaging.

12. Sinsky CA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Aug 29. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07766-0.

The American Gastroenterological Association and other gastrointestinal-specific organizations have excellent resources available to members that focus on optimizing reimbursement in your clinical and endoscopic practice.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency (PHE), many previously noncovered services were now covered under rules of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. During the pandemic, patient portal messages increased by 157%, meaning more work for health care teams, negatively impacting physician satisfaction, and increasing burnout.1 Medical burnout has been associated with increased time spent on electronic health records, with some subspeciality gastroenterology (GI) groups having a high EHR burden, according to a recently published article in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.2

This topic is a timely discussion as several large health systems have implemented processes to bill for non–face-to-face services (termed “asynchronous care”), some of which have not been well received in the lay media. It is important to note that despite these implementations, studies have shown only 1% of all incoming portal messages would meet criteria to be submitted for reimbursement. This impact might be slightly higher in chronic care management practices.

Providers and practices have several options when considering billing for non–face-to-face encounters, which we outline in Table 1.3

The focus of this article will be to review the more common non–face-to-face evaluation and management services, such as telephone E/M (patient phone call) and e-visits (patient portal messages) as these have recently generated the most interest and discussion amongst health care providers.

Telemedicine after COVID-19 pandemic

During the beginning of the pandemic, a web-based survey study found that almost all providers in GI practices implemented some form of telemedicine to continue to provide care for patients, compared to 32% prior to the pandemic.4,5 The high demand and essential requirement for telehealth evaluation facilitated its reimbursement, eliminating the primary barrier to previous use.6

One of the new covered benefits by CMS was asynchronous telehealth care.7 The PHE ended in May 2023, and since then a qualified health care provider (QHCP) does not have the full flexibility to deliver telemedicine services across state lines. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has considered some telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 PHE and many of those will be extended, at least through 2024.8 As during the pandemic, where the U.S. national payer network (CMS, state Medicaid, and private payers) and state health agencies assisted to ensure patients get the care they need by authorizing providers to be compensated for non–face-to-face services, we believe this service will continue to be part of our clinical practice.

We recommend you stay informed about local and federal laws, regulations, and alternatives for reimbursement as they may be modified at the beginning of a new calendar year. Remember, you can always talk with your revenue cycle team to clarify any query.

Telephone evaluation and management services

The patient requests to speak with you.

Telephone evaluation and management services became more widely used after the pandemic and were recognized by CMS as a covered medical service under PHE. As outlined in Table 1, there are associated codes with this service and it can only apply to an established patient in your practice. The cumulative time spent over a 7-day period without generating an immediate follow-up visit could qualify for this CPT code. However, for a patient with a high-complexity diagnosis and/or decisions being made about care, it might be better to consider a virtual office visit as this would value the complex care at a higher level than the time spent during the telephone E/M encounter.

A common question comes up: Can my nurse or support team bill for telephone care? No, only QHCP can, which means physicians and advanced practice providers can bill for this E/M service, and it does not include time spent by other members of clinical staff in patient care. However, there are CPT codes for chronic care management, which is not covered in this article.

Virtual evaluation and management services

You respond to a patient-initiated portal message.

Patient portal messages increased exponentially during the pandemic with 2.5 more minutes spent per message, resulting in more EHR work by practitioners, compared with prior to the pandemic. One study showed an immediate postpandemic increase in EHR patient-initiated messages with no return to prepandemic baseline.1

Although studies evaluating postpandemic telemedicine services are needed, we believe that this trend will continue, and for this reason, it is important to create sustainable workflows to continue to provide this patient driven avenue of care.9

E-visits are asynchronous patient or guardian portal messages that require a minimum of 5 minutes to provide medical decision-making without prior E/M services in the last 7 days. To obtain reimbursement for this service, it cannot be initiated by the provider, and patient consent must be obtained. Documentation should include this information and the time spent in the encounter. The associated CPT codes with this e-service are outlined in Table 1.

A common question is, “Are there additional codes I should use if a portal message E/M visit lasts more than 30 minutes?” No. If an e-visit lasts more than 30 minutes, the QHCP should bill the CPT code 99423. However, we would advise that, if this care requires more than 30 minutes, then either virtual or face-to-face E/M be considered for the optimal reimbursement for provider time spent. Another common question is around consent for services, and we advise providers to review this requirement with their compliance colleagues as each institution has different policies.

Virtual check-in

Medicare also covers brief communication technology–based services also known as virtual check-ins, where patients can communicate with their provider after having established care. During this brief conversation that can be via telephone, audio/video, secure text messaging, email, or patient portal, providers will determine if an in-person visit is necessary. CMS has designed G codes for these virtual check-ins that are from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Two codes are available for this E/M service: G2012, which is outlined in Table 1, and G2010, which covers the evaluation of images and/or recorded videos. In order to be reimbursed for a G2010 code, providers need at least a 5-minute response to make a clinical determination or give the patient a medical impression.

Patient satisfaction, physician well-being and quality of care outcomes

Large health care systems like Kaiser Permanente implemented secure message patient-physician communication (the patient portal) even before the pandemic, showing promising results in 2010 with reduction in office visits, improvement in measurable quality outcomes, and high level of patient satisfaction.10 Post pandemic, several large health care centers opted to announce the billing implementation for patient-initiated portal messages.11 A focus was placed on educating their patients about when a message will and will not be billed. Using this type of strategy can help to improve patient awareness about potential billing without affecting patient satisfaction and care outcomes. Studies have shown the EHR has contributed to physician burnout and some physicians reducing their clinical time or leaving medicine; a reduction in messaging might have a positive impact on physician well-being.

The challenge is that medical billing is not routinely included as a curriculum topic in many residency and fellowship programs; however, trainees are part of E/M services and have limited knowledge of billing processes. Unfortunately, at this time, trainees cannot submit for reimbursement for asynchronous care as described above. We hope that this brief article will help junior gastroenterologists optimize their outpatient billing practices.

Dr. Nieto is an internal medicine chief resident with WellStar Cobb Medical Center, Austell, Ga. Dr. Kinnucan is a gastroenterologist with Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose for this article. The authors certify that no financial and grant support has been received for this article.

References

1. Holmgren AJ et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021 Dec 9. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab268.

2. Bali AS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Apr 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002254.

3. AAFP. Family Physician. “Coding Scenario: Coding for Virtual-Digital Visits”

4. Keihanian T. et al. Telehealth Utilization in Gastroenterology Clinics Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Clinical Practice and Gastroenterology Training. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jun 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.040.

5. Lewin S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Oct 21. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa140.

6. Perisetti A and H Goyal. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Mar 3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-06874-x.

7. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Medicaid and Medicare billing for asynchronous telehealth. Updated: 2022 May 4.

8. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency. Last updated: 2023 Jan 23.

9. Fox B and Sizemore JO. Telehealth: Fad or the future. Epic Health Research Network. 2020 Aug 18.

10. Baer D. Patient-physician e-mail communication: the kaiser permanente experience. J Oncol Pract. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000323.

11. Myclevelandclinic.org. MyChart Messaging.

12. Sinsky CA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Aug 29. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07766-0.

Addressing an unmet need in IBD patients: Treatment of acute abdominal pain

In the acute care setting, providers of care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are often faced with the dilemma of providing effective abdominal pain management in a population that has worse outcomes with both opioid and NSAID therapy. There is increased mortality associated with opioid use and risk of disease relapse with NSAID use in IBD patients.1,2 Due to this, patients often feel that their pain is inadequately addressed.3,4 There are multiple sources of abdominal pain in IBD, and understanding the mechanisms and presentations can help identify effective treatments. We will review pharmacologic and supportive therapies to optimize pain management in IBD.

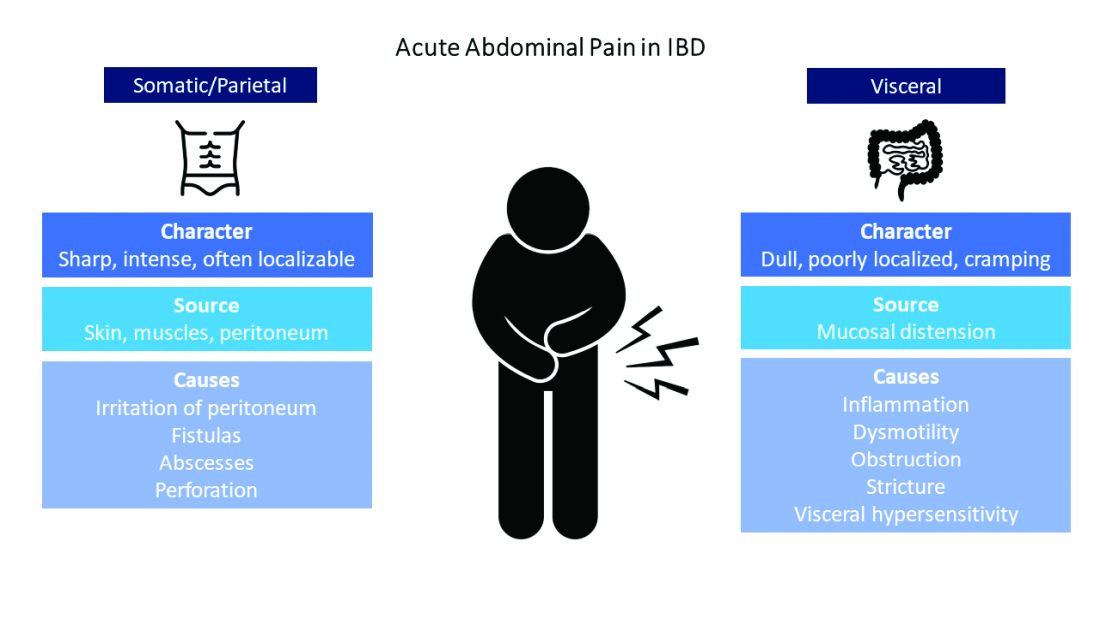

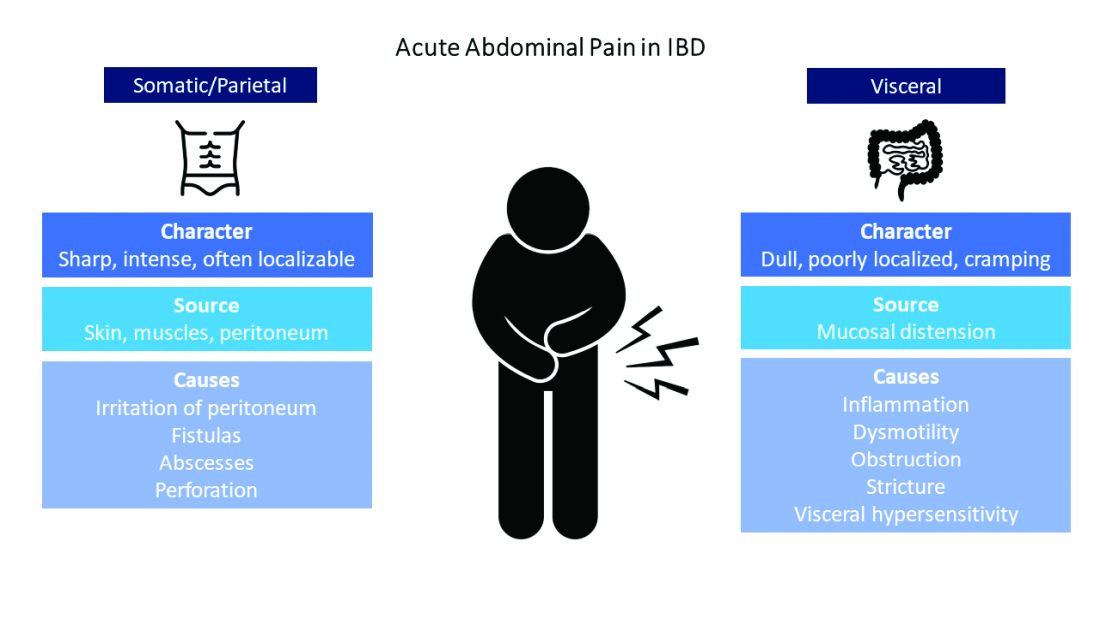

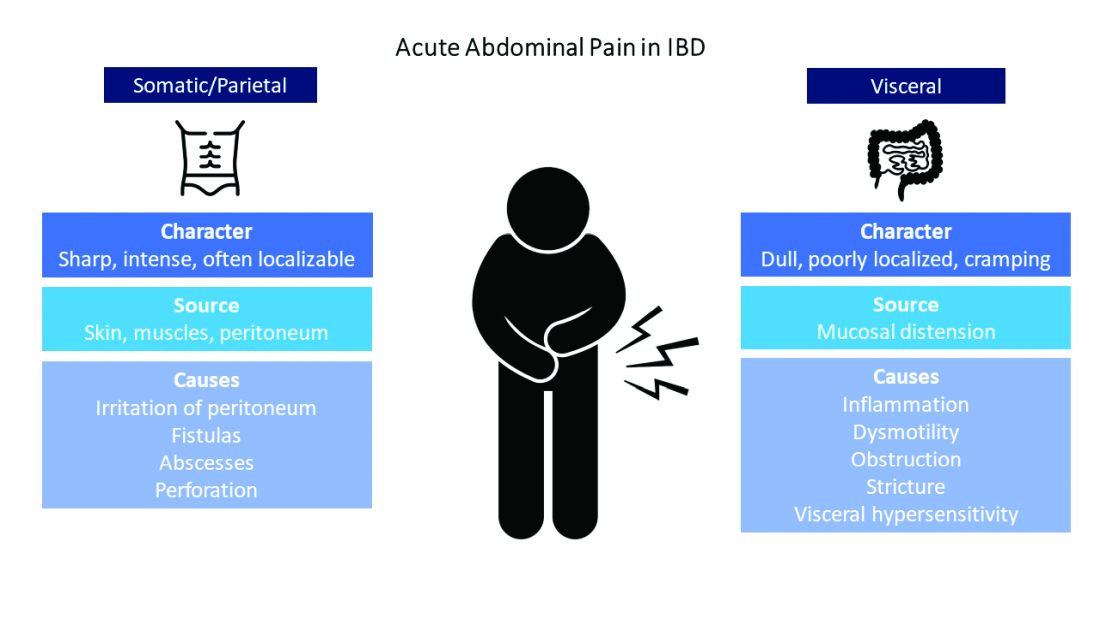

Common pain presentations in IBD

Visceral pain is a dull, poorly localized, cramping pain from intestinal distension. It is associated with inflammation, dysmotility, obstruction, and visceral hypersensitivity. Somatic and parietal pain is sharp, intense, and often localizable. Somatic pain originates from surrounding skin or muscles, and parietal pain arises from irritation of the peritoneum.5 We will review two common pain presentations in IBD.

Case 1: Mr. A is a 32-year-old male with stricturing small bowel Crohn’s disease s/p small bowel resection, who presents to the ED with 3 days of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. C-reactive protein is elevated to 6.8 mg/dL (normal 0.0 – 0.6 mg/dL), and CT is consistent with active small bowel inflammation, intraabdominal abscess at the anastomosis, and associated partial small bowel obstruction. He describes a sharp, intense abdominal pain with cramping. His exam is significant for diffuse abdominal tenderness and distension.

Case 2: Ms. B is a 28-year-old female with ulcerative colitis on mesalamine monotherapy who presents to the hospital for rectal bleeding and cramping abdominal pain. After 3 days of IV steroids her rectal bleeding has resolved, and CRP has normalized. However, she continues to have dull, cramping abdominal pain. Ibuprofen has improved this pain in the past.

Mr. A is having somatic pain from inflammation, abscess, and partial bowel obstruction. He also has visceral pain from luminal distension proximal to the obstruction. Ms. B is having visceral pain despite resolution of inflammation, which may be from postinflammatory visceral hypersensitivity.

Etiologies of pain

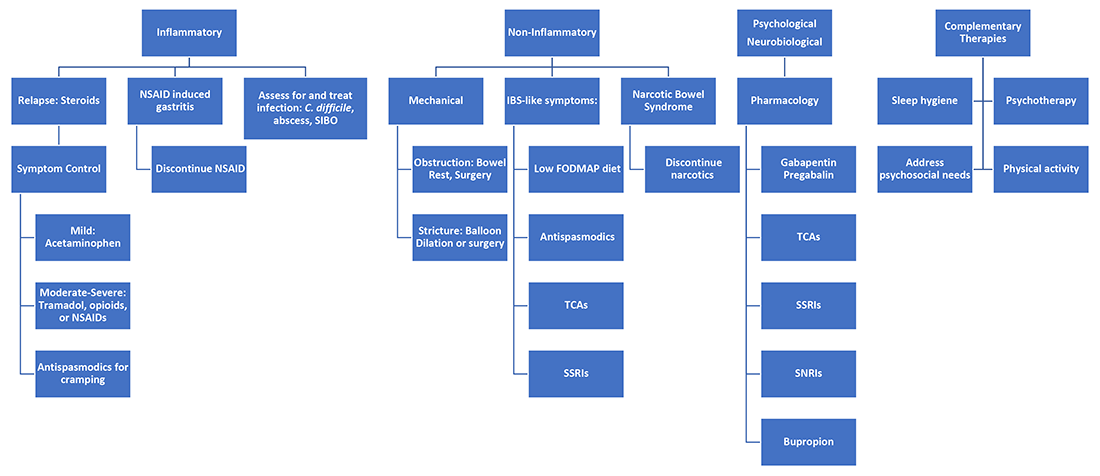

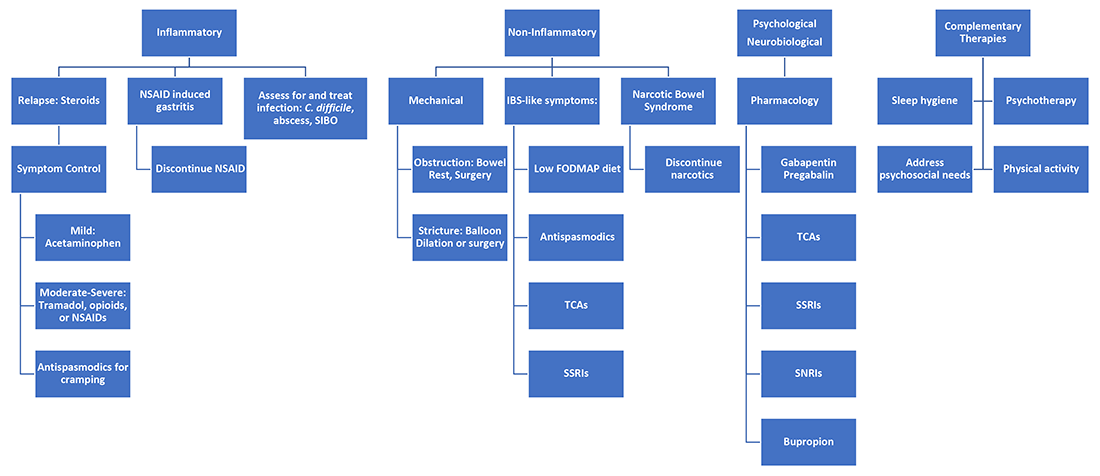

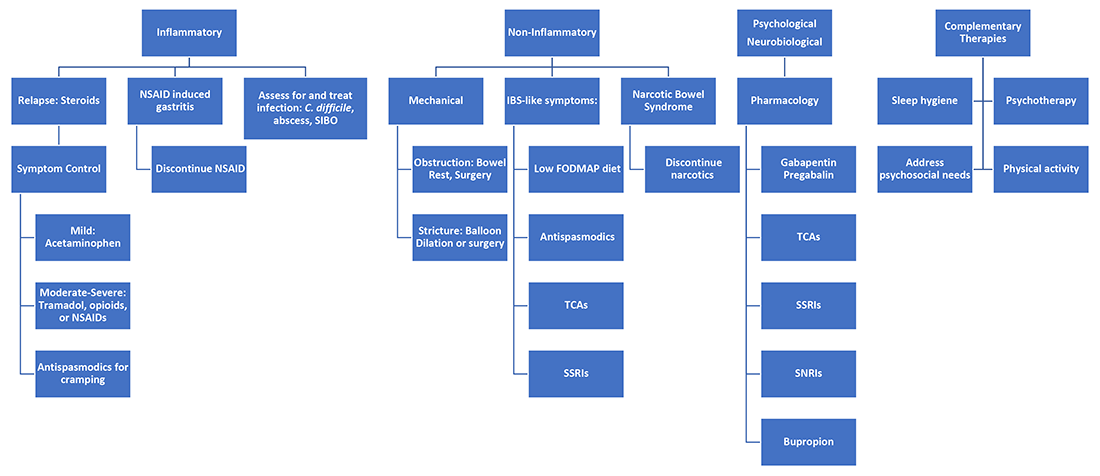

It’s best to group pain etiologies into inflammatory and noninflammatory causes. Inflammatory pain can be secondary to infection, such as abscess or enteric infection, active bowel inflammation, or disease complications (that is, enteric fistula). It is important to recognize that patients with active inflammation may also have noninflammatory pain. These include small bowel obstruction, strictures, adhesions, narcotic bowel syndrome, bacterial overgrowth, and visceral hypersensitivity. See figure 1.

The brain-gut connection matters

Abdominal pain in IBD patients starts from painful stimuli in the gut. In addition to direct pain pathways, multiple areas of the brain modulate perception of pain.6 Patients with psychiatric comorbidities have increased perception of abdominal pain.7 In fact, high perceived stress is associated with disease relapse.8 Treatment of psychiatric disorders improves these symptoms with lasting effects.9 Addressing psychological and psychosocial needs is essential to successful pain management with long-term effect on quality of life and pain perception in IBD patients.

What are my options?

When IBD patients present with acute abdominal pain, it is important to directly address their pain as one of your primary concerns and provide them with a management plan. While this seems obvious, it is not routinely done.3-4

Next, it is important to identify the cause, whether it be infection, obstruction, active inflammation, or functional abdominal pain. In the case of active disease, in addition to steroids and optimization of IBD therapies, acetaminophen and antispasmodics can be used for initial pain management. Supportive therapies include sleep hygiene, physical activity, and psychotherapy. If initial treatments are unsuccessful in the acute setting, and presentation is consistent with somatic pain, it may be necessary to escalate to tramadol, opioid, or NSAID therapy. For visceral pain, a neuromodulator, such as a tricyclic antidepressant or gabapentin, may have greater effect. Bupropion, SNRIs, and SSRIs are options; however, they may not be effective in the acute setting. More recent focus in the IBD community has questioned the role of cannabinoids on pain in IBD patients. Cannabis has been shown in a few small studies to provide pain relief in IBD patients with active inflammation.10-11 In patients with mechanical causes for pain, management of obstruction is an important part of the treatment plan.

Let’s talk about opioids in IBD patients

Chronic narcotic use in IBD is associated with worse outcomes. So when is it okay to use opioid therapies in IBD patients? Postoperative patients, patients with severe perianal disease, or those who fail alternative pain management strategies may require opioid medications. The association with mortality and opioids in IBD is with patients who require moderate to heavy use, which is defined as being prescribed opioids more than once a year. Opioid use in IBD patients is also associated with increased risk of readmissions and poor surgical outcomes.12-13 Tramadol does not have increased mortality risk.1 If selecting opioid therapy in managing pain in IBD, it is important to define the course of therapy, with a clear goal of discontinuation after the acute episode. Opioids should be used in tandem with alternative strategies. Patients should be counseled on the synergistic effect of acetaminophen with opioids, which may allow lower effective doses of opioids.

What about NSAID use in IBD patients?

NSAIDs have negative effects in the gastrointestinal tract due to inhibition of protective prostaglandins. They also alter the gut microbiome, although clinical implications of this are unknown.14 A small study showed that IBD patients who used NSAIDs had increased risk of disease relapse.2 Symptoms of relapse would present within 2-9 days of exposure; however, most had resolution of symptoms within 2-11 days of discontinuation.2 Follow-up studies have not reliably found that NSAIDs are associated with disease relapse.8 and thus NSAIDs may be used sparingly if needed in the acute setting.

Case Review: How do we approach Mr. A and Ms. B?

Mr. A presented with a partial small bowel obstruction and abscess. His pain presentation was consistent with both visceral and somatic pain etiologies. In addition to treating active inflammation and infection, bowel rest, acetaminophen, and antispasmodics can be initiated for pain control. Concomitantly, gabapentin, TCA, or SNRI can be initiated for neurobiological pain but may have limited benefit in the acute hospitalized setting. Social work may identify needs that affect pain perception and assist in addressing those needs. If abdominal pain persists, tramadol or hydrocodone-acetaminophen can be considered.

Ms. B presented with disease relapse, but despite improving inflammatory markers she had continued cramping abdominal pain, which can be consistent with visceral hypersensitivity. Antispasmodic and neuromodulating agents, such as a TCA, could be effective. We can recommend discontinuation of chronic ibuprofen due to risk of intestinal inflammation. Patients may inquire about adjuvant cannabis in pain management. While cannabis can be considered, further research is needed to recommend its regular use.

Conclusion

Acute abdominal pain management in IBD can be challenging for providers when typical options are limited in this population. Addressing inflammatory, mechanical, neurobiological, and psychological influences is vital to appropriately address pain. Having a structured plan for pain management in IBD can improve outcomes by decreasing recurrent hospitalizations and use of opioids.15 Figure 2 presents an overview.

Dr. Ahmed is a second-year internal medicine resident at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Kinnucan is with the department of internal medicine and the division of gastroenterology and hepatology and is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, both at the University of Michigan. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Burr NE et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr;16(4):534-41.e6.

2. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

3. Bernhofer EI et al. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017 May/Jun;40(3):200-7.

4. Zeitz J et al. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 22;11(6):e0156666.

5. Srinath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014 Dec;20(12):2433-49.

6. Docherty MJ et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011 Sep;7(9):592-601.

7. Elsenbruch S et al. Gut. 2010 Apr;59(4):489-95.

8. Bernstein CN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):1994-2002.

9. Palsson OS and Whitehead WE. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Mar;11(3):208-16; quiz e22-3.

10. Swaminath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar; 25(3):427-35.

11. Naftali T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;11(10):1276-80.e1.

12. Sultan K and Swaminath A. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Sep 16;14(9):1188-89.

13. Hirsch A et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Oct;19(10):1852-61.

14. Rogers MAM and Aronoff DM. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):178.e1-178.e9.

15. Kaimakliotis P et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Jun;36(6):1193-200.

In the acute care setting, providers of care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are often faced with the dilemma of providing effective abdominal pain management in a population that has worse outcomes with both opioid and NSAID therapy. There is increased mortality associated with opioid use and risk of disease relapse with NSAID use in IBD patients.1,2 Due to this, patients often feel that their pain is inadequately addressed.3,4 There are multiple sources of abdominal pain in IBD, and understanding the mechanisms and presentations can help identify effective treatments. We will review pharmacologic and supportive therapies to optimize pain management in IBD.

Common pain presentations in IBD

Visceral pain is a dull, poorly localized, cramping pain from intestinal distension. It is associated with inflammation, dysmotility, obstruction, and visceral hypersensitivity. Somatic and parietal pain is sharp, intense, and often localizable. Somatic pain originates from surrounding skin or muscles, and parietal pain arises from irritation of the peritoneum.5 We will review two common pain presentations in IBD.

Case 1: Mr. A is a 32-year-old male with stricturing small bowel Crohn’s disease s/p small bowel resection, who presents to the ED with 3 days of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. C-reactive protein is elevated to 6.8 mg/dL (normal 0.0 – 0.6 mg/dL), and CT is consistent with active small bowel inflammation, intraabdominal abscess at the anastomosis, and associated partial small bowel obstruction. He describes a sharp, intense abdominal pain with cramping. His exam is significant for diffuse abdominal tenderness and distension.

Case 2: Ms. B is a 28-year-old female with ulcerative colitis on mesalamine monotherapy who presents to the hospital for rectal bleeding and cramping abdominal pain. After 3 days of IV steroids her rectal bleeding has resolved, and CRP has normalized. However, she continues to have dull, cramping abdominal pain. Ibuprofen has improved this pain in the past.

Mr. A is having somatic pain from inflammation, abscess, and partial bowel obstruction. He also has visceral pain from luminal distension proximal to the obstruction. Ms. B is having visceral pain despite resolution of inflammation, which may be from postinflammatory visceral hypersensitivity.

Etiologies of pain

It’s best to group pain etiologies into inflammatory and noninflammatory causes. Inflammatory pain can be secondary to infection, such as abscess or enteric infection, active bowel inflammation, or disease complications (that is, enteric fistula). It is important to recognize that patients with active inflammation may also have noninflammatory pain. These include small bowel obstruction, strictures, adhesions, narcotic bowel syndrome, bacterial overgrowth, and visceral hypersensitivity. See figure 1.

The brain-gut connection matters

Abdominal pain in IBD patients starts from painful stimuli in the gut. In addition to direct pain pathways, multiple areas of the brain modulate perception of pain.6 Patients with psychiatric comorbidities have increased perception of abdominal pain.7 In fact, high perceived stress is associated with disease relapse.8 Treatment of psychiatric disorders improves these symptoms with lasting effects.9 Addressing psychological and psychosocial needs is essential to successful pain management with long-term effect on quality of life and pain perception in IBD patients.

What are my options?

When IBD patients present with acute abdominal pain, it is important to directly address their pain as one of your primary concerns and provide them with a management plan. While this seems obvious, it is not routinely done.3-4

Next, it is important to identify the cause, whether it be infection, obstruction, active inflammation, or functional abdominal pain. In the case of active disease, in addition to steroids and optimization of IBD therapies, acetaminophen and antispasmodics can be used for initial pain management. Supportive therapies include sleep hygiene, physical activity, and psychotherapy. If initial treatments are unsuccessful in the acute setting, and presentation is consistent with somatic pain, it may be necessary to escalate to tramadol, opioid, or NSAID therapy. For visceral pain, a neuromodulator, such as a tricyclic antidepressant or gabapentin, may have greater effect. Bupropion, SNRIs, and SSRIs are options; however, they may not be effective in the acute setting. More recent focus in the IBD community has questioned the role of cannabinoids on pain in IBD patients. Cannabis has been shown in a few small studies to provide pain relief in IBD patients with active inflammation.10-11 In patients with mechanical causes for pain, management of obstruction is an important part of the treatment plan.

Let’s talk about opioids in IBD patients

Chronic narcotic use in IBD is associated with worse outcomes. So when is it okay to use opioid therapies in IBD patients? Postoperative patients, patients with severe perianal disease, or those who fail alternative pain management strategies may require opioid medications. The association with mortality and opioids in IBD is with patients who require moderate to heavy use, which is defined as being prescribed opioids more than once a year. Opioid use in IBD patients is also associated with increased risk of readmissions and poor surgical outcomes.12-13 Tramadol does not have increased mortality risk.1 If selecting opioid therapy in managing pain in IBD, it is important to define the course of therapy, with a clear goal of discontinuation after the acute episode. Opioids should be used in tandem with alternative strategies. Patients should be counseled on the synergistic effect of acetaminophen with opioids, which may allow lower effective doses of opioids.

What about NSAID use in IBD patients?

NSAIDs have negative effects in the gastrointestinal tract due to inhibition of protective prostaglandins. They also alter the gut microbiome, although clinical implications of this are unknown.14 A small study showed that IBD patients who used NSAIDs had increased risk of disease relapse.2 Symptoms of relapse would present within 2-9 days of exposure; however, most had resolution of symptoms within 2-11 days of discontinuation.2 Follow-up studies have not reliably found that NSAIDs are associated with disease relapse.8 and thus NSAIDs may be used sparingly if needed in the acute setting.

Case Review: How do we approach Mr. A and Ms. B?

Mr. A presented with a partial small bowel obstruction and abscess. His pain presentation was consistent with both visceral and somatic pain etiologies. In addition to treating active inflammation and infection, bowel rest, acetaminophen, and antispasmodics can be initiated for pain control. Concomitantly, gabapentin, TCA, or SNRI can be initiated for neurobiological pain but may have limited benefit in the acute hospitalized setting. Social work may identify needs that affect pain perception and assist in addressing those needs. If abdominal pain persists, tramadol or hydrocodone-acetaminophen can be considered.

Ms. B presented with disease relapse, but despite improving inflammatory markers she had continued cramping abdominal pain, which can be consistent with visceral hypersensitivity. Antispasmodic and neuromodulating agents, such as a TCA, could be effective. We can recommend discontinuation of chronic ibuprofen due to risk of intestinal inflammation. Patients may inquire about adjuvant cannabis in pain management. While cannabis can be considered, further research is needed to recommend its regular use.

Conclusion

Acute abdominal pain management in IBD can be challenging for providers when typical options are limited in this population. Addressing inflammatory, mechanical, neurobiological, and psychological influences is vital to appropriately address pain. Having a structured plan for pain management in IBD can improve outcomes by decreasing recurrent hospitalizations and use of opioids.15 Figure 2 presents an overview.

Dr. Ahmed is a second-year internal medicine resident at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Kinnucan is with the department of internal medicine and the division of gastroenterology and hepatology and is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, both at the University of Michigan. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Burr NE et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr;16(4):534-41.e6.

2. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

3. Bernhofer EI et al. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017 May/Jun;40(3):200-7.

4. Zeitz J et al. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 22;11(6):e0156666.

5. Srinath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014 Dec;20(12):2433-49.

6. Docherty MJ et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011 Sep;7(9):592-601.

7. Elsenbruch S et al. Gut. 2010 Apr;59(4):489-95.

8. Bernstein CN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):1994-2002.

9. Palsson OS and Whitehead WE. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Mar;11(3):208-16; quiz e22-3.

10. Swaminath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar; 25(3):427-35.

11. Naftali T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;11(10):1276-80.e1.

12. Sultan K and Swaminath A. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Sep 16;14(9):1188-89.

13. Hirsch A et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Oct;19(10):1852-61.

14. Rogers MAM and Aronoff DM. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):178.e1-178.e9.

15. Kaimakliotis P et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Jun;36(6):1193-200.

In the acute care setting, providers of care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are often faced with the dilemma of providing effective abdominal pain management in a population that has worse outcomes with both opioid and NSAID therapy. There is increased mortality associated with opioid use and risk of disease relapse with NSAID use in IBD patients.1,2 Due to this, patients often feel that their pain is inadequately addressed.3,4 There are multiple sources of abdominal pain in IBD, and understanding the mechanisms and presentations can help identify effective treatments. We will review pharmacologic and supportive therapies to optimize pain management in IBD.

Common pain presentations in IBD

Visceral pain is a dull, poorly localized, cramping pain from intestinal distension. It is associated with inflammation, dysmotility, obstruction, and visceral hypersensitivity. Somatic and parietal pain is sharp, intense, and often localizable. Somatic pain originates from surrounding skin or muscles, and parietal pain arises from irritation of the peritoneum.5 We will review two common pain presentations in IBD.

Case 1: Mr. A is a 32-year-old male with stricturing small bowel Crohn’s disease s/p small bowel resection, who presents to the ED with 3 days of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. C-reactive protein is elevated to 6.8 mg/dL (normal 0.0 – 0.6 mg/dL), and CT is consistent with active small bowel inflammation, intraabdominal abscess at the anastomosis, and associated partial small bowel obstruction. He describes a sharp, intense abdominal pain with cramping. His exam is significant for diffuse abdominal tenderness and distension.

Case 2: Ms. B is a 28-year-old female with ulcerative colitis on mesalamine monotherapy who presents to the hospital for rectal bleeding and cramping abdominal pain. After 3 days of IV steroids her rectal bleeding has resolved, and CRP has normalized. However, she continues to have dull, cramping abdominal pain. Ibuprofen has improved this pain in the past.

Mr. A is having somatic pain from inflammation, abscess, and partial bowel obstruction. He also has visceral pain from luminal distension proximal to the obstruction. Ms. B is having visceral pain despite resolution of inflammation, which may be from postinflammatory visceral hypersensitivity.

Etiologies of pain

It’s best to group pain etiologies into inflammatory and noninflammatory causes. Inflammatory pain can be secondary to infection, such as abscess or enteric infection, active bowel inflammation, or disease complications (that is, enteric fistula). It is important to recognize that patients with active inflammation may also have noninflammatory pain. These include small bowel obstruction, strictures, adhesions, narcotic bowel syndrome, bacterial overgrowth, and visceral hypersensitivity. See figure 1.

The brain-gut connection matters

Abdominal pain in IBD patients starts from painful stimuli in the gut. In addition to direct pain pathways, multiple areas of the brain modulate perception of pain.6 Patients with psychiatric comorbidities have increased perception of abdominal pain.7 In fact, high perceived stress is associated with disease relapse.8 Treatment of psychiatric disorders improves these symptoms with lasting effects.9 Addressing psychological and psychosocial needs is essential to successful pain management with long-term effect on quality of life and pain perception in IBD patients.

What are my options?

When IBD patients present with acute abdominal pain, it is important to directly address their pain as one of your primary concerns and provide them with a management plan. While this seems obvious, it is not routinely done.3-4

Next, it is important to identify the cause, whether it be infection, obstruction, active inflammation, or functional abdominal pain. In the case of active disease, in addition to steroids and optimization of IBD therapies, acetaminophen and antispasmodics can be used for initial pain management. Supportive therapies include sleep hygiene, physical activity, and psychotherapy. If initial treatments are unsuccessful in the acute setting, and presentation is consistent with somatic pain, it may be necessary to escalate to tramadol, opioid, or NSAID therapy. For visceral pain, a neuromodulator, such as a tricyclic antidepressant or gabapentin, may have greater effect. Bupropion, SNRIs, and SSRIs are options; however, they may not be effective in the acute setting. More recent focus in the IBD community has questioned the role of cannabinoids on pain in IBD patients. Cannabis has been shown in a few small studies to provide pain relief in IBD patients with active inflammation.10-11 In patients with mechanical causes for pain, management of obstruction is an important part of the treatment plan.

Let’s talk about opioids in IBD patients

Chronic narcotic use in IBD is associated with worse outcomes. So when is it okay to use opioid therapies in IBD patients? Postoperative patients, patients with severe perianal disease, or those who fail alternative pain management strategies may require opioid medications. The association with mortality and opioids in IBD is with patients who require moderate to heavy use, which is defined as being prescribed opioids more than once a year. Opioid use in IBD patients is also associated with increased risk of readmissions and poor surgical outcomes.12-13 Tramadol does not have increased mortality risk.1 If selecting opioid therapy in managing pain in IBD, it is important to define the course of therapy, with a clear goal of discontinuation after the acute episode. Opioids should be used in tandem with alternative strategies. Patients should be counseled on the synergistic effect of acetaminophen with opioids, which may allow lower effective doses of opioids.

What about NSAID use in IBD patients?

NSAIDs have negative effects in the gastrointestinal tract due to inhibition of protective prostaglandins. They also alter the gut microbiome, although clinical implications of this are unknown.14 A small study showed that IBD patients who used NSAIDs had increased risk of disease relapse.2 Symptoms of relapse would present within 2-9 days of exposure; however, most had resolution of symptoms within 2-11 days of discontinuation.2 Follow-up studies have not reliably found that NSAIDs are associated with disease relapse.8 and thus NSAIDs may be used sparingly if needed in the acute setting.

Case Review: How do we approach Mr. A and Ms. B?

Mr. A presented with a partial small bowel obstruction and abscess. His pain presentation was consistent with both visceral and somatic pain etiologies. In addition to treating active inflammation and infection, bowel rest, acetaminophen, and antispasmodics can be initiated for pain control. Concomitantly, gabapentin, TCA, or SNRI can be initiated for neurobiological pain but may have limited benefit in the acute hospitalized setting. Social work may identify needs that affect pain perception and assist in addressing those needs. If abdominal pain persists, tramadol or hydrocodone-acetaminophen can be considered.

Ms. B presented with disease relapse, but despite improving inflammatory markers she had continued cramping abdominal pain, which can be consistent with visceral hypersensitivity. Antispasmodic and neuromodulating agents, such as a TCA, could be effective. We can recommend discontinuation of chronic ibuprofen due to risk of intestinal inflammation. Patients may inquire about adjuvant cannabis in pain management. While cannabis can be considered, further research is needed to recommend its regular use.

Conclusion

Acute abdominal pain management in IBD can be challenging for providers when typical options are limited in this population. Addressing inflammatory, mechanical, neurobiological, and psychological influences is vital to appropriately address pain. Having a structured plan for pain management in IBD can improve outcomes by decreasing recurrent hospitalizations and use of opioids.15 Figure 2 presents an overview.

Dr. Ahmed is a second-year internal medicine resident at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Kinnucan is with the department of internal medicine and the division of gastroenterology and hepatology and is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, both at the University of Michigan. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Burr NE et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr;16(4):534-41.e6.

2. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

3. Bernhofer EI et al. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017 May/Jun;40(3):200-7.

4. Zeitz J et al. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 22;11(6):e0156666.

5. Srinath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014 Dec;20(12):2433-49.

6. Docherty MJ et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011 Sep;7(9):592-601.

7. Elsenbruch S et al. Gut. 2010 Apr;59(4):489-95.

8. Bernstein CN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):1994-2002.

9. Palsson OS and Whitehead WE. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Mar;11(3):208-16; quiz e22-3.

10. Swaminath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar; 25(3):427-35.

11. Naftali T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;11(10):1276-80.e1.

12. Sultan K and Swaminath A. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Sep 16;14(9):1188-89.

13. Hirsch A et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Oct;19(10):1852-61.

14. Rogers MAM and Aronoff DM. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):178.e1-178.e9.

15. Kaimakliotis P et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Jun;36(6):1193-200.

A practical approach to utilizing cannabis as adjuvant therapy in inflammatory bowel disease

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

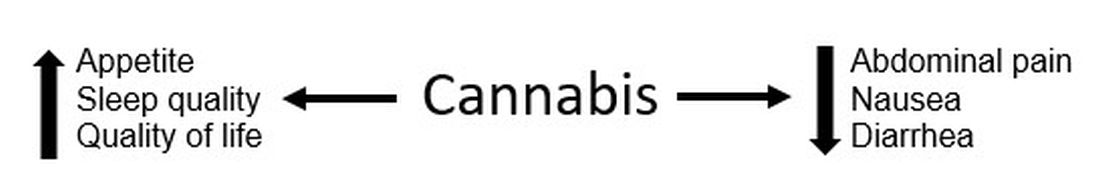

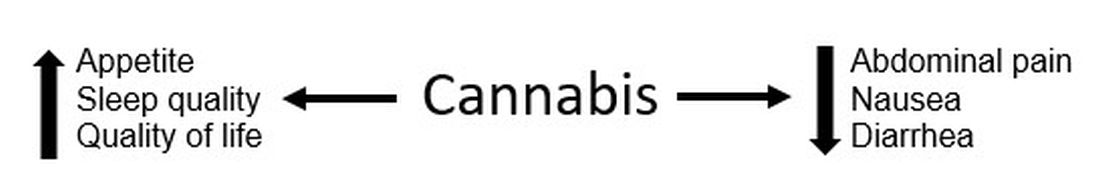

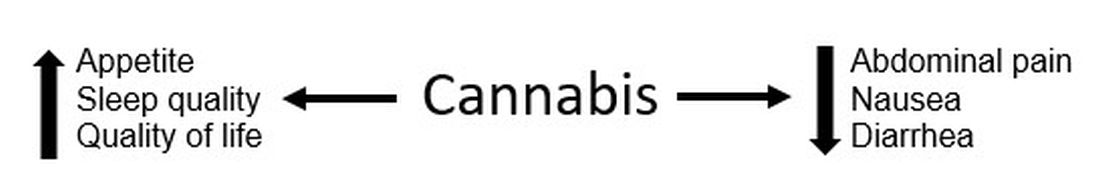

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion

These cases outline the challenges that providers face when managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when a patient would like to either substitute or incorporate cannabis into their treatment plan. Studies have shown a high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with IBD. With the restrictions surrounding the use of cannabis – either medically or recreationally – being liberalized in many states, these conversations are likely to become more frequent in your practice. However, one of the first challenges that providers face surrounding cannabis is that many patients who use cannabis do not disclose use to their health care team for fear of being judged negatively. In addition, many providers do not routinely ask about cannabis use during office visits. This might be directly related to being unprepared to have a knowledge-based discussion on the risks and benefits of cannabis use in IBD, with the same confidence present during discussion of biologic therapies.

For background, Cannabis sativa (cannabis) is composed of hundreds of phytocannabinoids, the two most common are THC and CBD. These cannabinoids act at the endocannabinoid receptors, which are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and immune cells/tissues, and help explain the clinical changes experienced by cannabis users. Both THC and CBD have been studied in varying doses and routes of administration in patients with IBD, making it challenging to translate into real-world recommendations for patients. Some of the most common reported benefits of cannabis use (particularly in an IBD population) are improvement in pain, diarrhea, nausea, and joint pain. Some studies have shown overall improvement in quality of life (Figure 1).

Some common questions that arise surrounding cannabis use in IBD patients include:

1. Is it possible to stop traditional medical therapy and replace it with cannabis therapy?

No studies have directly addressed this exact question. The small studies, both randomized controlled trials and retrospective ones, have studied the effects of cannabis as adjuvant therapy only. None of the data available to date suggest that cannabis has any anti-inflammatory properties with absence of improvement in biomarkers or endoscopic measures of inflammation. In effect, any attempt to discontinue standard therapy with substitution of cannabis-based therapy should be seen as no different than simply discontinuing standard therapy. There exists the argument that – among those with moderate to severe disease – cannabis might suppress the investigation of mild symptoms which may herald a flare of disease, thus lulling the patient into a state of false stability. We do not advocate the substitution of cannabis products in place of standard medical therapy.

2. Is there a role for cannabis as adjuvant therapy in patients with IBD?

Studies to date have included only symptomatic patients with objective evidence of inflammation and assessed clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic endpoints. In Crohn’s disease, two studies showed no improvement in clinical remission rates but showed improvement in clinical response; a third study showed both improvement in clinical remission/response as well as improved quality of life. No study showed a change in disease markers of activity including CRP, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopic scoring. In one study, all patients relapsed shortly after cannabis discontinuation suggesting that, while there was benefit in symptom control, there was no improvement of the underlying chronic inflammation.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, there were two studies. One study showed no improvement and high rates of intolerance in the treatment group, while the other study reported improved disease activity but no objective improvement. The variation in results between disease states and between studies might be because of cannabis formulations. In patients with persistent symptoms despite current medical therapy, there might be a role in those patients for adjuvant therapy for improvement symptom control but not disease control. Optimization of medical therapy would still be indicated.

3. What dose and formulation of cannabis should I recommend to a patient as adjuvant therapy?

This is an excellent question and one that unfortunately we do not have the answer to. As mentioned previously, the studies have looked at varying formulations (THC alone, CBD:THC with varying percentages of THC, CBD alone) and varying routes of administration (sublingual, oral, inhalation). The IBD studies looking at CBD-alone formulations lacked clinical efficacy. In states where cannabis products have been accessible to IBD patients, no data on the product type (THC:CBD), method of administration, or prescriber preferences have been published.

4. What risks should I advise my patients about with cannabis use?

The challenge is that we don’t have large population-based studies in IBD looking at long-term risks of cannabis use. However, in the small RCT studies there were minimal reported side effects and no major adverse events over 8-10 weeks. Larger IBD population-based studies have shown that cannabis users were more likely to discontinue traditional medical therapy, and there is an increased risk for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Larger studies in non-IBD patients have shown risk for addiction to other substances, diminished life achievement, increased motor vehicle accidents, chronic bronchitis, psychiatric disturbances and cannabis dependence, and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (with an uncanny presentation resembling Crohn’s disease flare with partial small bowel obstruction). Patients should also be advised about legal implications of use (given its continued classification as a federal schedule 1 drug), possible drug interactions, and special considerations in pediatric patients (increased risk of addiction), elderly patients (increased risk of neuropsychological effects), and during pregnancy (with national obstetric society guidelines warning against use because of fetal exposure and increased risk of stillbirth).

5. What are the legal implications for providers? Patients?

As of July 2020, cannabis is available for recreational use in 12 states, for medicinal use in 28 states, and illegal in 11 states. So the answer really depends on what state the patient lives in. As a provider who might certify patients (in some medicinal states) or recommend cannabis to patients, you should consider legal and licensing implications. Again, this might vary state to state, and you should also take into account federal status. Providers acting in compliance with state laws are unlikely to have federal consequences. However, remember that malpractice insurance only covers FDA-approved medical therapies. Patients should be advised to consider the potential (although highly unlikely) to face federal prosecution and implications of use for employment, school, camp, or travel, and driving restrictions.

Take home points

- Inquire about cannabis to start the conversation.

- Know your state’s legalization status surrounding cannabis.

- Patients with IBD report improvement in symptoms and quality of life with adjuvant cannabis use; however, there is no change in disease activity.

- Encourage your patients to continue and optimize their maintenance therapy.

- Educate your patients about the legal considerations and known risks.

In conclusion, the use of cannabis in IBD patients has increased in recent years. It is important to be able to discuss the risks and benefits of use with your IBD patients. Focus on the lack of data showing that cannabis improves disease activity, and has shown benefit only in improving IBD-associated symptoms. In some patients there might be a role for adjuvant cannabis therapy to improve overall symptom control and quality of life.

Dr. Kinnucan is an assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Swaminath is an associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Lenox Hill Hospital, Northwell Health, New York.

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion

These cases outline the challenges that providers face when managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when a patient would like to either substitute or incorporate cannabis into their treatment plan. Studies have shown a high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with IBD. With the restrictions surrounding the use of cannabis – either medically or recreationally – being liberalized in many states, these conversations are likely to become more frequent in your practice. However, one of the first challenges that providers face surrounding cannabis is that many patients who use cannabis do not disclose use to their health care team for fear of being judged negatively. In addition, many providers do not routinely ask about cannabis use during office visits. This might be directly related to being unprepared to have a knowledge-based discussion on the risks and benefits of cannabis use in IBD, with the same confidence present during discussion of biologic therapies.

For background, Cannabis sativa (cannabis) is composed of hundreds of phytocannabinoids, the two most common are THC and CBD. These cannabinoids act at the endocannabinoid receptors, which are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and immune cells/tissues, and help explain the clinical changes experienced by cannabis users. Both THC and CBD have been studied in varying doses and routes of administration in patients with IBD, making it challenging to translate into real-world recommendations for patients. Some of the most common reported benefits of cannabis use (particularly in an IBD population) are improvement in pain, diarrhea, nausea, and joint pain. Some studies have shown overall improvement in quality of life (Figure 1).

Some common questions that arise surrounding cannabis use in IBD patients include:

1. Is it possible to stop traditional medical therapy and replace it with cannabis therapy?

No studies have directly addressed this exact question. The small studies, both randomized controlled trials and retrospective ones, have studied the effects of cannabis as adjuvant therapy only. None of the data available to date suggest that cannabis has any anti-inflammatory properties with absence of improvement in biomarkers or endoscopic measures of inflammation. In effect, any attempt to discontinue standard therapy with substitution of cannabis-based therapy should be seen as no different than simply discontinuing standard therapy. There exists the argument that – among those with moderate to severe disease – cannabis might suppress the investigation of mild symptoms which may herald a flare of disease, thus lulling the patient into a state of false stability. We do not advocate the substitution of cannabis products in place of standard medical therapy.

2. Is there a role for cannabis as adjuvant therapy in patients with IBD?

Studies to date have included only symptomatic patients with objective evidence of inflammation and assessed clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic endpoints. In Crohn’s disease, two studies showed no improvement in clinical remission rates but showed improvement in clinical response; a third study showed both improvement in clinical remission/response as well as improved quality of life. No study showed a change in disease markers of activity including CRP, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopic scoring. In one study, all patients relapsed shortly after cannabis discontinuation suggesting that, while there was benefit in symptom control, there was no improvement of the underlying chronic inflammation.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, there were two studies. One study showed no improvement and high rates of intolerance in the treatment group, while the other study reported improved disease activity but no objective improvement. The variation in results between disease states and between studies might be because of cannabis formulations. In patients with persistent symptoms despite current medical therapy, there might be a role in those patients for adjuvant therapy for improvement symptom control but not disease control. Optimization of medical therapy would still be indicated.

3. What dose and formulation of cannabis should I recommend to a patient as adjuvant therapy?

This is an excellent question and one that unfortunately we do not have the answer to. As mentioned previously, the studies have looked at varying formulations (THC alone, CBD:THC with varying percentages of THC, CBD alone) and varying routes of administration (sublingual, oral, inhalation). The IBD studies looking at CBD-alone formulations lacked clinical efficacy. In states where cannabis products have been accessible to IBD patients, no data on the product type (THC:CBD), method of administration, or prescriber preferences have been published.

4. What risks should I advise my patients about with cannabis use?

The challenge is that we don’t have large population-based studies in IBD looking at long-term risks of cannabis use. However, in the small RCT studies there were minimal reported side effects and no major adverse events over 8-10 weeks. Larger IBD population-based studies have shown that cannabis users were more likely to discontinue traditional medical therapy, and there is an increased risk for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Larger studies in non-IBD patients have shown risk for addiction to other substances, diminished life achievement, increased motor vehicle accidents, chronic bronchitis, psychiatric disturbances and cannabis dependence, and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (with an uncanny presentation resembling Crohn’s disease flare with partial small bowel obstruction). Patients should also be advised about legal implications of use (given its continued classification as a federal schedule 1 drug), possible drug interactions, and special considerations in pediatric patients (increased risk of addiction), elderly patients (increased risk of neuropsychological effects), and during pregnancy (with national obstetric society guidelines warning against use because of fetal exposure and increased risk of stillbirth).

5. What are the legal implications for providers? Patients?

As of July 2020, cannabis is available for recreational use in 12 states, for medicinal use in 28 states, and illegal in 11 states. So the answer really depends on what state the patient lives in. As a provider who might certify patients (in some medicinal states) or recommend cannabis to patients, you should consider legal and licensing implications. Again, this might vary state to state, and you should also take into account federal status. Providers acting in compliance with state laws are unlikely to have federal consequences. However, remember that malpractice insurance only covers FDA-approved medical therapies. Patients should be advised to consider the potential (although highly unlikely) to face federal prosecution and implications of use for employment, school, camp, or travel, and driving restrictions.

Take home points

- Inquire about cannabis to start the conversation.

- Know your state’s legalization status surrounding cannabis.

- Patients with IBD report improvement in symptoms and quality of life with adjuvant cannabis use; however, there is no change in disease activity.

- Encourage your patients to continue and optimize their maintenance therapy.

- Educate your patients about the legal considerations and known risks.

In conclusion, the use of cannabis in IBD patients has increased in recent years. It is important to be able to discuss the risks and benefits of use with your IBD patients. Focus on the lack of data showing that cannabis improves disease activity, and has shown benefit only in improving IBD-associated symptoms. In some patients there might be a role for adjuvant cannabis therapy to improve overall symptom control and quality of life.

Dr. Kinnucan is an assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Swaminath is an associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Lenox Hill Hospital, Northwell Health, New York.

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

Figure 1.

Case 2