User login

Child of The New Gastroenterologist

Retirement Planning for Gastroenterologists

Retirement planning starts the day we start our careers. Whenever we start any project, it is always worthwhile to learn how the project works, what we want to pursue and achieve with the project, how to exit the project, and when is the right time to exit.

As physicians, gastroenterologists go through several years of vigorous training, years spent studying, researching, practicing, and juggling between work and life, trying to lead a well-balanced life. With all the years of medical training, we do not get the same level of education in financial planning in order to attain financial stability, financial empowerment, or resources that we need to put in place for a successful retirement.

Many physicians like to work and provide services as long as they can, provided the physical and mental capacity permits. Retirement planning should start as early as possible — at your first job, with the first paycheck. Having a strategic plan and understanding several personal factors can help one make this journey successful.

Financial Planning

Financial planning starts with investments in 401k, IRA, defined benefit, and defined contribution plans, as early as possible and to the maximum extent possible. It is beneficial to contribute at the first opportunity and contribute enough to the employer retirement plan to earn the full employer match. Also consider capital investment opportunities that match your risk appetite and returns, as these compound and grow over time. This can be done by adjusting personal expenses and lifestyle, giving priority to savings and future wealth management, and auto-escalation of permitted retirement contributions annually.

Assessing your financial situation periodically to determine retirement needs based on how long you intend to work and preferred lifestyle post retirement (travel, leisurely activities, etc.) is important. It is also pertinent to align revenue earned, expenses made, and wealth saved to support post-retirement life. Consider hiring a financial advisor who has the best interests in your personal wealth management. These are usually found with reputable institutions at a fixed percentage cost. Finding a trustworthy knowledgeable advisor is the key. Learning from your colleagues, networking, and learning from friends in and out of healthcare are good resources to find the right financial advisor.

Healthcare expenses should be planned as well as part of financial planning. Short-term and long-term disability and long-term care expenses should be investigated when planning for healthcare needs.

Transition Planning

Timing of retirement is based on factors such as age, financial status, personal health and preferences. The transition can be facilitated by better communication with colleagues, partners, employer, staff, and patients. Identifying a successor and planning for continuity of care of the patients, such as transitioning patients to another provider, is important as well. This may involve hiring a new associate, merging with another practice, or selling the practice.

Healthcare Coverage

One of the biggest expenses with retirement is healthcare coverage. Healthcare coverage options need to be analyzed which may include Medicare eligibility, enrollment, potential needs after retirement, including preventative care, treatment of chronic conditions, long term care services, and unexpected health outcomes and consequences.

Lifestyle and Travel Planning

Reflect on the retirement lifestyle, hobbies, and passions to be explored. Some activities like volunteer work, continuing educational opportunities, and advisory work, will help maintain physical and mental health. Consider downsizing living arrangements to align with retirement lifestyle goals which may include relocating to a different area as it fits your needs.

Legal and Estate Planning

Review and update legal documents including power of attorney, healthcare directives, will, trusts, and periodically ensure that these documents reflect your wishes.

Professional Development

Retirement may not mean quitting work completely. Some may look at this as an opportunity for professional development and pivoting to a different career that suits their lifestyle and needs. Gastroenterologists may contribute to the field and stay connected by being mentors, advisors, or, industry partners; being involved in national organizations; leading purposeful projects; or teaching part-time or on a volunteer basis.

Emotional and Social Support

Being a physician and a leader on treatment teams after so many years, some may feel lonely and unproductive with a lack of purpose in retirement; while others are excited about the free time they gained to pursue other activities and projects.

The process can be emotionally challenging even for well-prepared individuals. Finding friends, family, and professionals who can support you through this process will be helpful as you go through the uncertainties, anxiety, and fear during this phase of life. Think of developing hobbies and interests and nurturing networks outside of work environment that will keep you engaged and content during this transition.

Gastroenterologists can plan for a financially secure, emotionally fulfilling, and professionally satisfying transition tailored to their needs and preferences. Seeking help from financial advisors, legal experts, mentors, and other professionals who can provide valuable advice, support, and guidance is crucial during this process.

Do what you love and love what you do.

Dr. Appalaneni is a gastroenterologist at Dayton Gastroenterology in Beavercreek, Ohio, and a clinical assistant professor at Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. This article is not a financial planning document, nor legal advice; these are the author’s learnings, experiences, and opinions and are not considered financial advice.

Retirement planning starts the day we start our careers. Whenever we start any project, it is always worthwhile to learn how the project works, what we want to pursue and achieve with the project, how to exit the project, and when is the right time to exit.

As physicians, gastroenterologists go through several years of vigorous training, years spent studying, researching, practicing, and juggling between work and life, trying to lead a well-balanced life. With all the years of medical training, we do not get the same level of education in financial planning in order to attain financial stability, financial empowerment, or resources that we need to put in place for a successful retirement.

Many physicians like to work and provide services as long as they can, provided the physical and mental capacity permits. Retirement planning should start as early as possible — at your first job, with the first paycheck. Having a strategic plan and understanding several personal factors can help one make this journey successful.

Financial Planning

Financial planning starts with investments in 401k, IRA, defined benefit, and defined contribution plans, as early as possible and to the maximum extent possible. It is beneficial to contribute at the first opportunity and contribute enough to the employer retirement plan to earn the full employer match. Also consider capital investment opportunities that match your risk appetite and returns, as these compound and grow over time. This can be done by adjusting personal expenses and lifestyle, giving priority to savings and future wealth management, and auto-escalation of permitted retirement contributions annually.

Assessing your financial situation periodically to determine retirement needs based on how long you intend to work and preferred lifestyle post retirement (travel, leisurely activities, etc.) is important. It is also pertinent to align revenue earned, expenses made, and wealth saved to support post-retirement life. Consider hiring a financial advisor who has the best interests in your personal wealth management. These are usually found with reputable institutions at a fixed percentage cost. Finding a trustworthy knowledgeable advisor is the key. Learning from your colleagues, networking, and learning from friends in and out of healthcare are good resources to find the right financial advisor.

Healthcare expenses should be planned as well as part of financial planning. Short-term and long-term disability and long-term care expenses should be investigated when planning for healthcare needs.

Transition Planning

Timing of retirement is based on factors such as age, financial status, personal health and preferences. The transition can be facilitated by better communication with colleagues, partners, employer, staff, and patients. Identifying a successor and planning for continuity of care of the patients, such as transitioning patients to another provider, is important as well. This may involve hiring a new associate, merging with another practice, or selling the practice.

Healthcare Coverage

One of the biggest expenses with retirement is healthcare coverage. Healthcare coverage options need to be analyzed which may include Medicare eligibility, enrollment, potential needs after retirement, including preventative care, treatment of chronic conditions, long term care services, and unexpected health outcomes and consequences.

Lifestyle and Travel Planning

Reflect on the retirement lifestyle, hobbies, and passions to be explored. Some activities like volunteer work, continuing educational opportunities, and advisory work, will help maintain physical and mental health. Consider downsizing living arrangements to align with retirement lifestyle goals which may include relocating to a different area as it fits your needs.

Legal and Estate Planning

Review and update legal documents including power of attorney, healthcare directives, will, trusts, and periodically ensure that these documents reflect your wishes.

Professional Development

Retirement may not mean quitting work completely. Some may look at this as an opportunity for professional development and pivoting to a different career that suits their lifestyle and needs. Gastroenterologists may contribute to the field and stay connected by being mentors, advisors, or, industry partners; being involved in national organizations; leading purposeful projects; or teaching part-time or on a volunteer basis.

Emotional and Social Support

Being a physician and a leader on treatment teams after so many years, some may feel lonely and unproductive with a lack of purpose in retirement; while others are excited about the free time they gained to pursue other activities and projects.

The process can be emotionally challenging even for well-prepared individuals. Finding friends, family, and professionals who can support you through this process will be helpful as you go through the uncertainties, anxiety, and fear during this phase of life. Think of developing hobbies and interests and nurturing networks outside of work environment that will keep you engaged and content during this transition.

Gastroenterologists can plan for a financially secure, emotionally fulfilling, and professionally satisfying transition tailored to their needs and preferences. Seeking help from financial advisors, legal experts, mentors, and other professionals who can provide valuable advice, support, and guidance is crucial during this process.

Do what you love and love what you do.

Dr. Appalaneni is a gastroenterologist at Dayton Gastroenterology in Beavercreek, Ohio, and a clinical assistant professor at Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. This article is not a financial planning document, nor legal advice; these are the author’s learnings, experiences, and opinions and are not considered financial advice.

Retirement planning starts the day we start our careers. Whenever we start any project, it is always worthwhile to learn how the project works, what we want to pursue and achieve with the project, how to exit the project, and when is the right time to exit.

As physicians, gastroenterologists go through several years of vigorous training, years spent studying, researching, practicing, and juggling between work and life, trying to lead a well-balanced life. With all the years of medical training, we do not get the same level of education in financial planning in order to attain financial stability, financial empowerment, or resources that we need to put in place for a successful retirement.

Many physicians like to work and provide services as long as they can, provided the physical and mental capacity permits. Retirement planning should start as early as possible — at your first job, with the first paycheck. Having a strategic plan and understanding several personal factors can help one make this journey successful.

Financial Planning

Financial planning starts with investments in 401k, IRA, defined benefit, and defined contribution plans, as early as possible and to the maximum extent possible. It is beneficial to contribute at the first opportunity and contribute enough to the employer retirement plan to earn the full employer match. Also consider capital investment opportunities that match your risk appetite and returns, as these compound and grow over time. This can be done by adjusting personal expenses and lifestyle, giving priority to savings and future wealth management, and auto-escalation of permitted retirement contributions annually.

Assessing your financial situation periodically to determine retirement needs based on how long you intend to work and preferred lifestyle post retirement (travel, leisurely activities, etc.) is important. It is also pertinent to align revenue earned, expenses made, and wealth saved to support post-retirement life. Consider hiring a financial advisor who has the best interests in your personal wealth management. These are usually found with reputable institutions at a fixed percentage cost. Finding a trustworthy knowledgeable advisor is the key. Learning from your colleagues, networking, and learning from friends in and out of healthcare are good resources to find the right financial advisor.

Healthcare expenses should be planned as well as part of financial planning. Short-term and long-term disability and long-term care expenses should be investigated when planning for healthcare needs.

Transition Planning

Timing of retirement is based on factors such as age, financial status, personal health and preferences. The transition can be facilitated by better communication with colleagues, partners, employer, staff, and patients. Identifying a successor and planning for continuity of care of the patients, such as transitioning patients to another provider, is important as well. This may involve hiring a new associate, merging with another practice, or selling the practice.

Healthcare Coverage

One of the biggest expenses with retirement is healthcare coverage. Healthcare coverage options need to be analyzed which may include Medicare eligibility, enrollment, potential needs after retirement, including preventative care, treatment of chronic conditions, long term care services, and unexpected health outcomes and consequences.

Lifestyle and Travel Planning

Reflect on the retirement lifestyle, hobbies, and passions to be explored. Some activities like volunteer work, continuing educational opportunities, and advisory work, will help maintain physical and mental health. Consider downsizing living arrangements to align with retirement lifestyle goals which may include relocating to a different area as it fits your needs.

Legal and Estate Planning

Review and update legal documents including power of attorney, healthcare directives, will, trusts, and periodically ensure that these documents reflect your wishes.

Professional Development

Retirement may not mean quitting work completely. Some may look at this as an opportunity for professional development and pivoting to a different career that suits their lifestyle and needs. Gastroenterologists may contribute to the field and stay connected by being mentors, advisors, or, industry partners; being involved in national organizations; leading purposeful projects; or teaching part-time or on a volunteer basis.

Emotional and Social Support

Being a physician and a leader on treatment teams after so many years, some may feel lonely and unproductive with a lack of purpose in retirement; while others are excited about the free time they gained to pursue other activities and projects.

The process can be emotionally challenging even for well-prepared individuals. Finding friends, family, and professionals who can support you through this process will be helpful as you go through the uncertainties, anxiety, and fear during this phase of life. Think of developing hobbies and interests and nurturing networks outside of work environment that will keep you engaged and content during this transition.

Gastroenterologists can plan for a financially secure, emotionally fulfilling, and professionally satisfying transition tailored to their needs and preferences. Seeking help from financial advisors, legal experts, mentors, and other professionals who can provide valuable advice, support, and guidance is crucial during this process.

Do what you love and love what you do.

Dr. Appalaneni is a gastroenterologist at Dayton Gastroenterology in Beavercreek, Ohio, and a clinical assistant professor at Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. This article is not a financial planning document, nor legal advice; these are the author’s learnings, experiences, and opinions and are not considered financial advice.

Navigating the Search for a Financial Adviser

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

Tax Questions Frequently Asked by Physicians

Physicians spend years of their lives in education and training. There are countless hours devoted to studying, researching, and clinical training, not to mention residency and possible fellowships. Then literally overnight, they transition out of a resident salary into a full-time attending pay with little to no education around what to do with this significant increase in salary.

Every job position is unique in terms of benefits, how compensation is earned, job expectations, etc. But they all share one thing in common — taxes. Increased income comes with increased taxes.

FAQ 1. What is the difference between W2 income and 1099 income?

A: If you are a W2 employee, your employer is responsible for paying half of your Social Security and Medicare taxes. You, as the employee, are then responsible only for the remaining half of your Social Security and Medicare taxes. Additionally, your employer will withhold these taxes, along with federal income taxes, from your paycheck each pay period. You are not responsible for remitting any taxes to the IRS or state agencies, as your employer will do this for you. As a W2 employee, you are not able to deduct any employee expenses against your income.

As a 1099 contractor, you are considered self-employed and are responsible for the employer and employee portion of the Social Security and Medicare taxes. You are also responsible for remitting these taxes, as well as quarterly estimated federal withholding, to the IRS and state agencies. You can deduct work-related expenses against your 1099 income.

Both types of income have pros and cons. Either of these can be more beneficial to a specific situation.

FAQ 2. How do I know if I am withholding enough taxes?

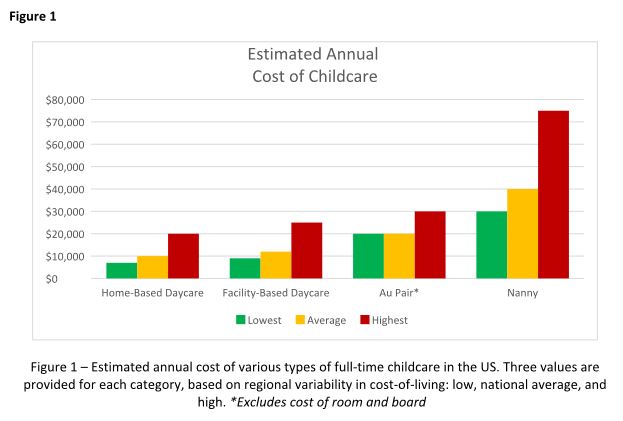

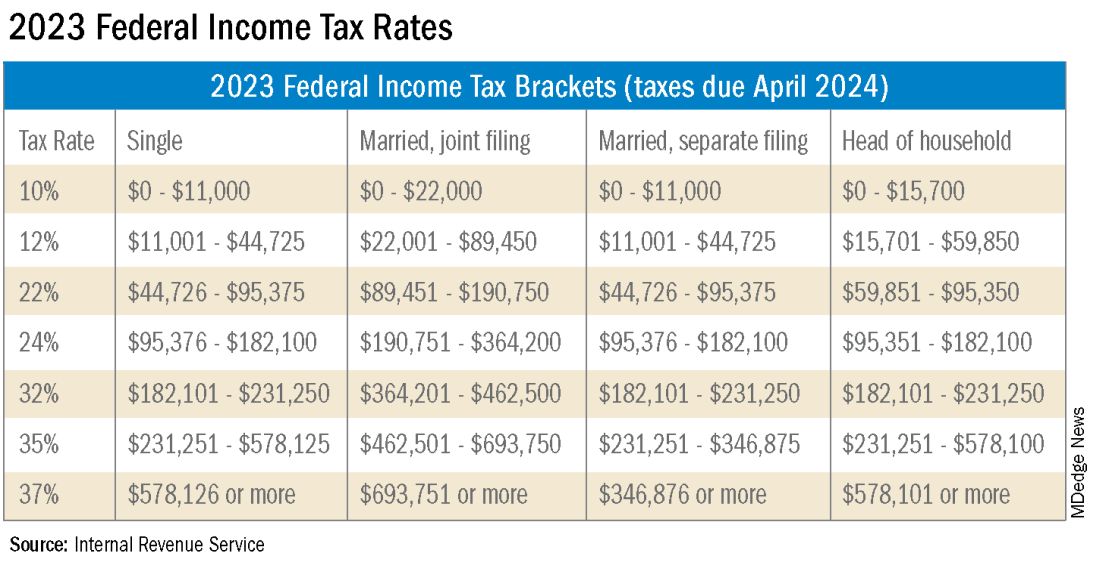

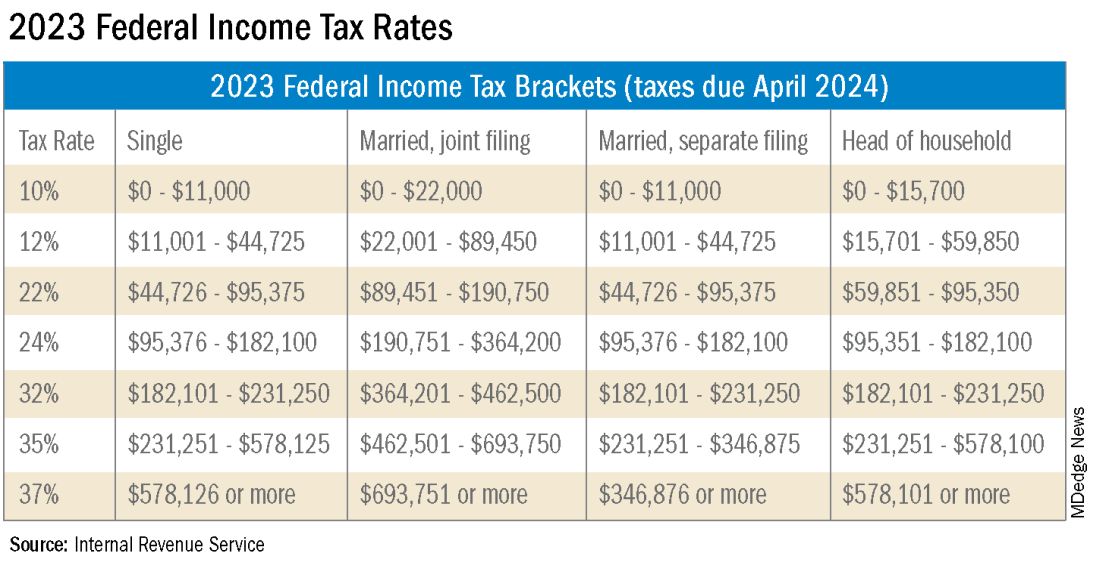

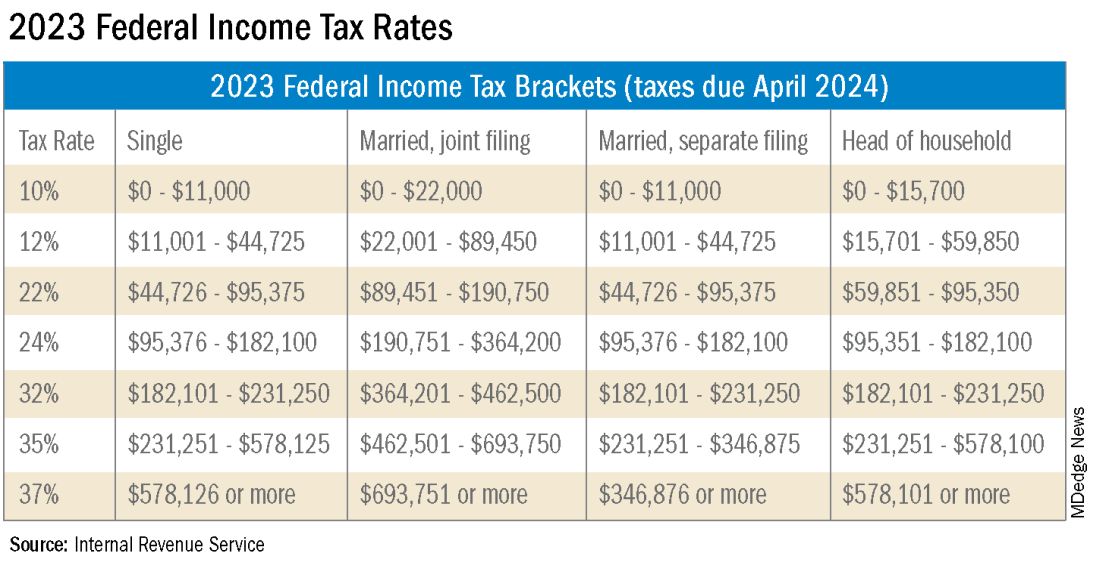

A: This is a very common issue I see, especially with physicians who are transitioning out of training into their full-time attending salary. Because this transition happens mid-year, often the first half of the year you are withholding at a rate much lower than what you will be earning as an attending and end up with a tax surprise at filing. One way to remedy this is to look at how much taxes are being withheld from your paycheck and compare this to what tax bracket you anticipate to be in, depending on filing status (Figure 1). If you do this and realize you are not withholding enough taxes, you can submit an amended form W4 to your employer to have additional withholding taken out each pay period.

FAQ 3. I am a 1099 contractor; do I need a PLLC, and should I file as an S-Corporation?

A: The term “S-Corp” gets mentioned often related to 1099 contractors and can be extremely beneficial from a tax savings perspective. Often physicians may moonlight — in addition to working in their W2 positions — and would receive this compensation as a 1099 contractor rather than an employee. This is an example of when a Professional Limited Liability Company (PLLC) might be advisable. A PLLC is created at a state level and helps shield owners from potential litigation. The owner of a PLLC pays Social Security and Medicare taxes on all income earned from the entity, and the PLLC is included in the owner’s individual income tax return.

A Small-Corporation (S-Corporation) is a tax classification that passes income through to the owners. The PLLC is now taxed as an S-Corporation, rather than a disregarded entity. The shareholders of the S-Corporation are required to pay a reasonable salary (W2 income). The remaining income passes through to the owner and is not subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes, only federal income tax. This taxation status requires an additional tax return and payroll service. Because there are additional expenses with being taxed as an S-Corporation, a cost-benefit analysis should be done before changing the tax classification to confirm that the tax savings are greater than the additional costs.

FAQ 4. What is the ‘backdoor Roth’ strategy? Should I implement it?

A: A Roth IRA is a specific type of Individual Retirement Account (IRA) that is funded with after-tax dollars. The contributions and growth in a Roth IRA can be withdrawn at retirement, tax free. As physicians who are typically high earners, you are not able to contribute directly to a Roth IRA because of income limitations. This is where the Roth conversion strategy — the backdoor Roth — comes into play. This strategy allows you to make a nondeductible traditional IRA contribution and then convert those dollars into a Roth IRA. In 2023, you can contribute up to $6,500 into this type of account. There are many additional considerations that must be made before implementing this strategy. Discussion with a financial advisor or CPA is recommended.

FAQ 5. I’ve always done my own taxes. Do I need to hire a CPA?

A: For many physicians, especially during training, your tax situation may not warrant the need for a Certified Public Accountant (CPA). However, as your income and tax complexity increase, working with a CPA not only decreases your risk for error, but also helps ensure you are not overpaying in taxes. There are many different types of services that a CPA can offer, the most basic being tax preparation. This is simply compiling your tax return based on the circumstances that occurred in the prior year. Tax planning is an additional level of service that may not be included in tax preparation cost. Tax planning is a proactive approach to taxes and helps maximize tax savings opportunities before return preparation. When interviewing a potential CPA, you can ask what level of services are included in the fees quoted.

These are just a few of the questions I regularly answer related to physicians’ taxation. The tax code is complex and ever changing. Recommendations that are made today might not be applicable or advisable in the future to any given situation. Working with a professional can ensure you have the most up-to-date and accurate information related to your taxes.

Ms. Anderson is with Physician’s Resource Services and is on Instagram @physiciansrs . Dr. Anderson is a CA-1 Resident in Anesthesia at Baylor Scott and White Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Physicians spend years of their lives in education and training. There are countless hours devoted to studying, researching, and clinical training, not to mention residency and possible fellowships. Then literally overnight, they transition out of a resident salary into a full-time attending pay with little to no education around what to do with this significant increase in salary.

Every job position is unique in terms of benefits, how compensation is earned, job expectations, etc. But they all share one thing in common — taxes. Increased income comes with increased taxes.

FAQ 1. What is the difference between W2 income and 1099 income?

A: If you are a W2 employee, your employer is responsible for paying half of your Social Security and Medicare taxes. You, as the employee, are then responsible only for the remaining half of your Social Security and Medicare taxes. Additionally, your employer will withhold these taxes, along with federal income taxes, from your paycheck each pay period. You are not responsible for remitting any taxes to the IRS or state agencies, as your employer will do this for you. As a W2 employee, you are not able to deduct any employee expenses against your income.

As a 1099 contractor, you are considered self-employed and are responsible for the employer and employee portion of the Social Security and Medicare taxes. You are also responsible for remitting these taxes, as well as quarterly estimated federal withholding, to the IRS and state agencies. You can deduct work-related expenses against your 1099 income.

Both types of income have pros and cons. Either of these can be more beneficial to a specific situation.

FAQ 2. How do I know if I am withholding enough taxes?

A: This is a very common issue I see, especially with physicians who are transitioning out of training into their full-time attending salary. Because this transition happens mid-year, often the first half of the year you are withholding at a rate much lower than what you will be earning as an attending and end up with a tax surprise at filing. One way to remedy this is to look at how much taxes are being withheld from your paycheck and compare this to what tax bracket you anticipate to be in, depending on filing status (Figure 1). If you do this and realize you are not withholding enough taxes, you can submit an amended form W4 to your employer to have additional withholding taken out each pay period.

FAQ 3. I am a 1099 contractor; do I need a PLLC, and should I file as an S-Corporation?

A: The term “S-Corp” gets mentioned often related to 1099 contractors and can be extremely beneficial from a tax savings perspective. Often physicians may moonlight — in addition to working in their W2 positions — and would receive this compensation as a 1099 contractor rather than an employee. This is an example of when a Professional Limited Liability Company (PLLC) might be advisable. A PLLC is created at a state level and helps shield owners from potential litigation. The owner of a PLLC pays Social Security and Medicare taxes on all income earned from the entity, and the PLLC is included in the owner’s individual income tax return.

A Small-Corporation (S-Corporation) is a tax classification that passes income through to the owners. The PLLC is now taxed as an S-Corporation, rather than a disregarded entity. The shareholders of the S-Corporation are required to pay a reasonable salary (W2 income). The remaining income passes through to the owner and is not subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes, only federal income tax. This taxation status requires an additional tax return and payroll service. Because there are additional expenses with being taxed as an S-Corporation, a cost-benefit analysis should be done before changing the tax classification to confirm that the tax savings are greater than the additional costs.

FAQ 4. What is the ‘backdoor Roth’ strategy? Should I implement it?

A: A Roth IRA is a specific type of Individual Retirement Account (IRA) that is funded with after-tax dollars. The contributions and growth in a Roth IRA can be withdrawn at retirement, tax free. As physicians who are typically high earners, you are not able to contribute directly to a Roth IRA because of income limitations. This is where the Roth conversion strategy — the backdoor Roth — comes into play. This strategy allows you to make a nondeductible traditional IRA contribution and then convert those dollars into a Roth IRA. In 2023, you can contribute up to $6,500 into this type of account. There are many additional considerations that must be made before implementing this strategy. Discussion with a financial advisor or CPA is recommended.

FAQ 5. I’ve always done my own taxes. Do I need to hire a CPA?

A: For many physicians, especially during training, your tax situation may not warrant the need for a Certified Public Accountant (CPA). However, as your income and tax complexity increase, working with a CPA not only decreases your risk for error, but also helps ensure you are not overpaying in taxes. There are many different types of services that a CPA can offer, the most basic being tax preparation. This is simply compiling your tax return based on the circumstances that occurred in the prior year. Tax planning is an additional level of service that may not be included in tax preparation cost. Tax planning is a proactive approach to taxes and helps maximize tax savings opportunities before return preparation. When interviewing a potential CPA, you can ask what level of services are included in the fees quoted.

These are just a few of the questions I regularly answer related to physicians’ taxation. The tax code is complex and ever changing. Recommendations that are made today might not be applicable or advisable in the future to any given situation. Working with a professional can ensure you have the most up-to-date and accurate information related to your taxes.

Ms. Anderson is with Physician’s Resource Services and is on Instagram @physiciansrs . Dr. Anderson is a CA-1 Resident in Anesthesia at Baylor Scott and White Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Physicians spend years of their lives in education and training. There are countless hours devoted to studying, researching, and clinical training, not to mention residency and possible fellowships. Then literally overnight, they transition out of a resident salary into a full-time attending pay with little to no education around what to do with this significant increase in salary.

Every job position is unique in terms of benefits, how compensation is earned, job expectations, etc. But they all share one thing in common — taxes. Increased income comes with increased taxes.

FAQ 1. What is the difference between W2 income and 1099 income?

A: If you are a W2 employee, your employer is responsible for paying half of your Social Security and Medicare taxes. You, as the employee, are then responsible only for the remaining half of your Social Security and Medicare taxes. Additionally, your employer will withhold these taxes, along with federal income taxes, from your paycheck each pay period. You are not responsible for remitting any taxes to the IRS or state agencies, as your employer will do this for you. As a W2 employee, you are not able to deduct any employee expenses against your income.

As a 1099 contractor, you are considered self-employed and are responsible for the employer and employee portion of the Social Security and Medicare taxes. You are also responsible for remitting these taxes, as well as quarterly estimated federal withholding, to the IRS and state agencies. You can deduct work-related expenses against your 1099 income.

Both types of income have pros and cons. Either of these can be more beneficial to a specific situation.

FAQ 2. How do I know if I am withholding enough taxes?

A: This is a very common issue I see, especially with physicians who are transitioning out of training into their full-time attending salary. Because this transition happens mid-year, often the first half of the year you are withholding at a rate much lower than what you will be earning as an attending and end up with a tax surprise at filing. One way to remedy this is to look at how much taxes are being withheld from your paycheck and compare this to what tax bracket you anticipate to be in, depending on filing status (Figure 1). If you do this and realize you are not withholding enough taxes, you can submit an amended form W4 to your employer to have additional withholding taken out each pay period.

FAQ 3. I am a 1099 contractor; do I need a PLLC, and should I file as an S-Corporation?

A: The term “S-Corp” gets mentioned often related to 1099 contractors and can be extremely beneficial from a tax savings perspective. Often physicians may moonlight — in addition to working in their W2 positions — and would receive this compensation as a 1099 contractor rather than an employee. This is an example of when a Professional Limited Liability Company (PLLC) might be advisable. A PLLC is created at a state level and helps shield owners from potential litigation. The owner of a PLLC pays Social Security and Medicare taxes on all income earned from the entity, and the PLLC is included in the owner’s individual income tax return.

A Small-Corporation (S-Corporation) is a tax classification that passes income through to the owners. The PLLC is now taxed as an S-Corporation, rather than a disregarded entity. The shareholders of the S-Corporation are required to pay a reasonable salary (W2 income). The remaining income passes through to the owner and is not subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes, only federal income tax. This taxation status requires an additional tax return and payroll service. Because there are additional expenses with being taxed as an S-Corporation, a cost-benefit analysis should be done before changing the tax classification to confirm that the tax savings are greater than the additional costs.

FAQ 4. What is the ‘backdoor Roth’ strategy? Should I implement it?

A: A Roth IRA is a specific type of Individual Retirement Account (IRA) that is funded with after-tax dollars. The contributions and growth in a Roth IRA can be withdrawn at retirement, tax free. As physicians who are typically high earners, you are not able to contribute directly to a Roth IRA because of income limitations. This is where the Roth conversion strategy — the backdoor Roth — comes into play. This strategy allows you to make a nondeductible traditional IRA contribution and then convert those dollars into a Roth IRA. In 2023, you can contribute up to $6,500 into this type of account. There are many additional considerations that must be made before implementing this strategy. Discussion with a financial advisor or CPA is recommended.

FAQ 5. I’ve always done my own taxes. Do I need to hire a CPA?

A: For many physicians, especially during training, your tax situation may not warrant the need for a Certified Public Accountant (CPA). However, as your income and tax complexity increase, working with a CPA not only decreases your risk for error, but also helps ensure you are not overpaying in taxes. There are many different types of services that a CPA can offer, the most basic being tax preparation. This is simply compiling your tax return based on the circumstances that occurred in the prior year. Tax planning is an additional level of service that may not be included in tax preparation cost. Tax planning is a proactive approach to taxes and helps maximize tax savings opportunities before return preparation. When interviewing a potential CPA, you can ask what level of services are included in the fees quoted.

These are just a few of the questions I regularly answer related to physicians’ taxation. The tax code is complex and ever changing. Recommendations that are made today might not be applicable or advisable in the future to any given situation. Working with a professional can ensure you have the most up-to-date and accurate information related to your taxes.

Ms. Anderson is with Physician’s Resource Services and is on Instagram @physiciansrs . Dr. Anderson is a CA-1 Resident in Anesthesia at Baylor Scott and White Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Five personal finance questions for the young GI

While this article will get you started, these are complex topics, and each could warrant several standalone articles. I strongly encourage you to develop some basic understanding of personal finance through books, websites, and podcasts. If you can manage Barrett’s esophagus, Crohn’s, and cirrhosis, you can understand the basics of personal finance.

1. What should I do about my student loans? Go for public service loan forgiveness or pay them off?

The first step is knowing your debt burden, knowing your options, and developing a plan to pay off student loans. Public service loan forgiveness (PSLF) can be a good option in many situations. For borrowers staying in academic or other 501(c)(3) positions, PSLF is often an obvious move. Importantly, a fall 2022 statement by the U.S. Department of Education clarified that physicians working as contractors for nonprofit hospitals in California and Texas may now qualify for PSLF.1,2

For trainees debating an academic/501(c)(3) position vs. private practice, I would generally not advise making a career choice based purely on PSLF eligibility. However, borrowers with very high federal student loan burdens (e.g., debt to income ratio of > 2:1), or who are very close to the PSLF 10-year requirement may want to consider choosing a qualifying position for a few years to receive PSLF student loan forgiveness. Please see TNG’s 2020 article3 for a deeper discussion. Consultation with a company specializing in student loan advice for physicians may be well worth the upfront cost.

2. Do I need disability insurance? What should I look for?

I would strongly advise getting disability insurance as soon as possible (including while in training). While disability insurance is not cheap, it is one of the first steps you should take and one of the most important ways to protect your financial future. It is essential to look for a specialty-specific own occupation policy. Such a policy will provide disability payments if you are no longer able to work as a gastroenterologist/hepatologist (including an injury which prevents you from doing endoscopies).

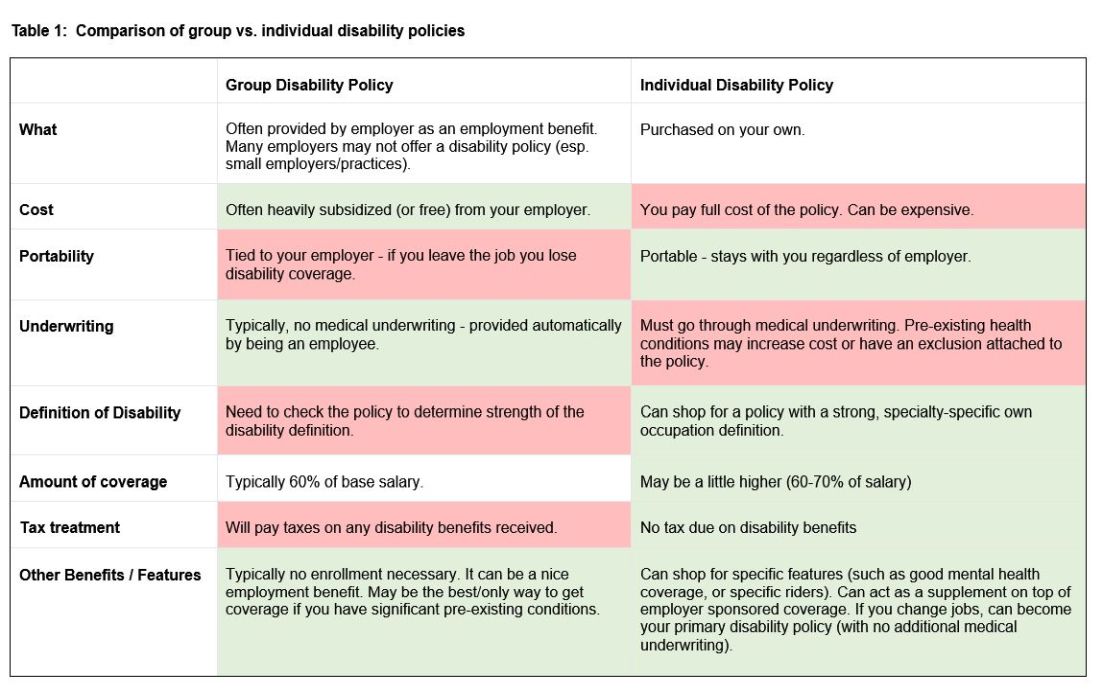

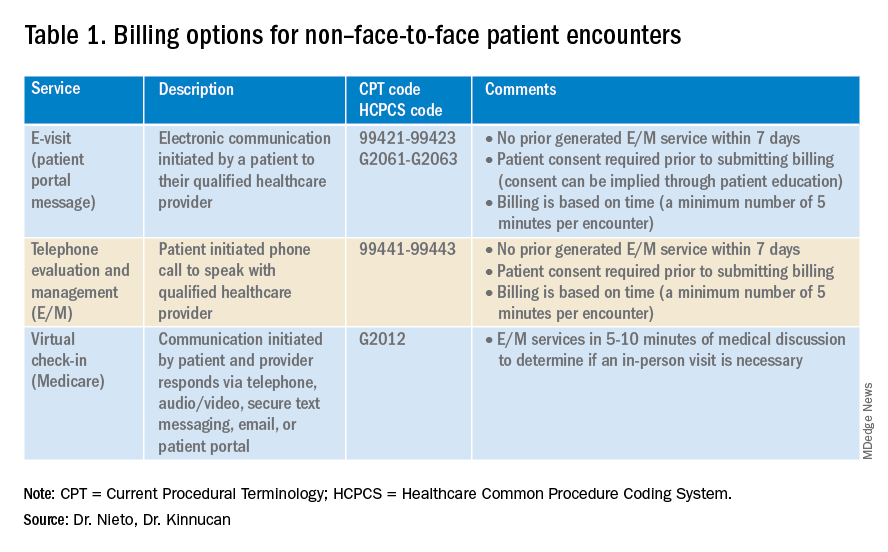

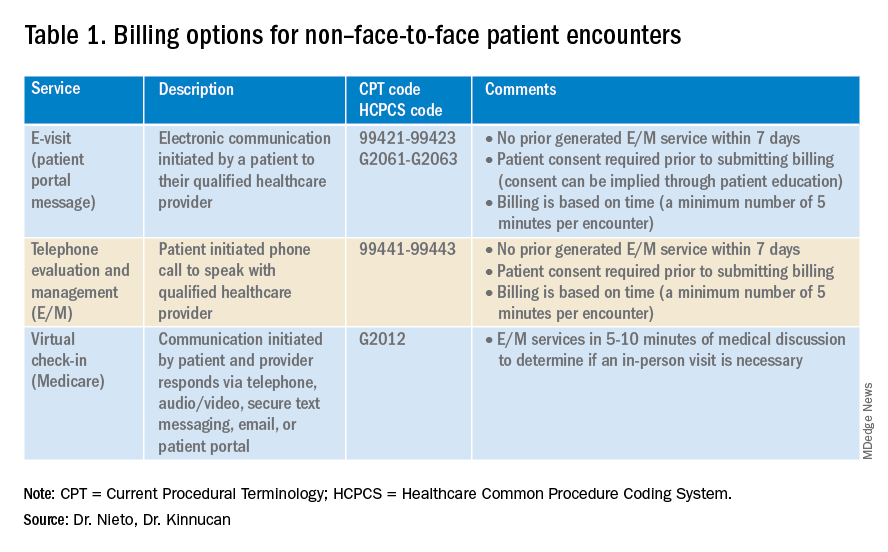

There are two major types of disability policies: group policies and individual policies. See table 1 for a detailed comparison.

Your hospital/employer may provide a group policy at a heavily subsidized rate. Alternatively, you can purchase an individual disability policy, which is independent of your employer and will stay with you even if you change jobs. Currently, the only companies providing high quality own-occupation policies for physicians are Mass Mutual, Principal, Guardian, The Standard, and Ameritas. Because disability insurance is complicated, it is highly advisable to work with an agent experienced in physician disability policies.

Importantly, even if you have a group disability policy, you can purchase an individual policy as a supplement to provide extra coverage. If you leave employers, the individual policy can then become your primary disability policy without any additional medical underwriting.

3. Do I need life insurance? What type should I get?

If anyone is dependent on your income (partner, child, etc.), you should have life insurance. Moreover, if you expect to have dependents in the near future (e.g., children), you could consider getting life insurance now while you are younger and healthier. For a young GI with multiple financial obligations, term life insurance is generally the right product. Term life insurance is a straightforward, affordable product that can be purchased from multiple high-quality insurance carriers. There are two major considerations: The amount of coverage ($2 million, $3 million, etc.) and the length of coverage (20 years, 30 years, etc.). To estimate the appropriate amount of coverage, start with your expected annual household living expenses, and multiply by 25-30. While this is a rule of thumb, it will get you in the ballpark. For many young physicians, a $2-$5 million policy with 20- to 30-year coverage is reasonable.

Many financial advisers may suggest whole life insurance policies. These are typically not the ideal policy for young GIs who are just starting their careers. While whole life insurance may be the right choice in select cases, term life insurance will be the best product for most of TNG’s audience. As an example, a $3 million, 25-year term policy for a healthy, nonsmoking 35-year-old male would cost approximately $175 per month. A similar $3 million whole life policy could cost $2,000 per month or more.

4. What do I need to know about retirement accounts and investing?

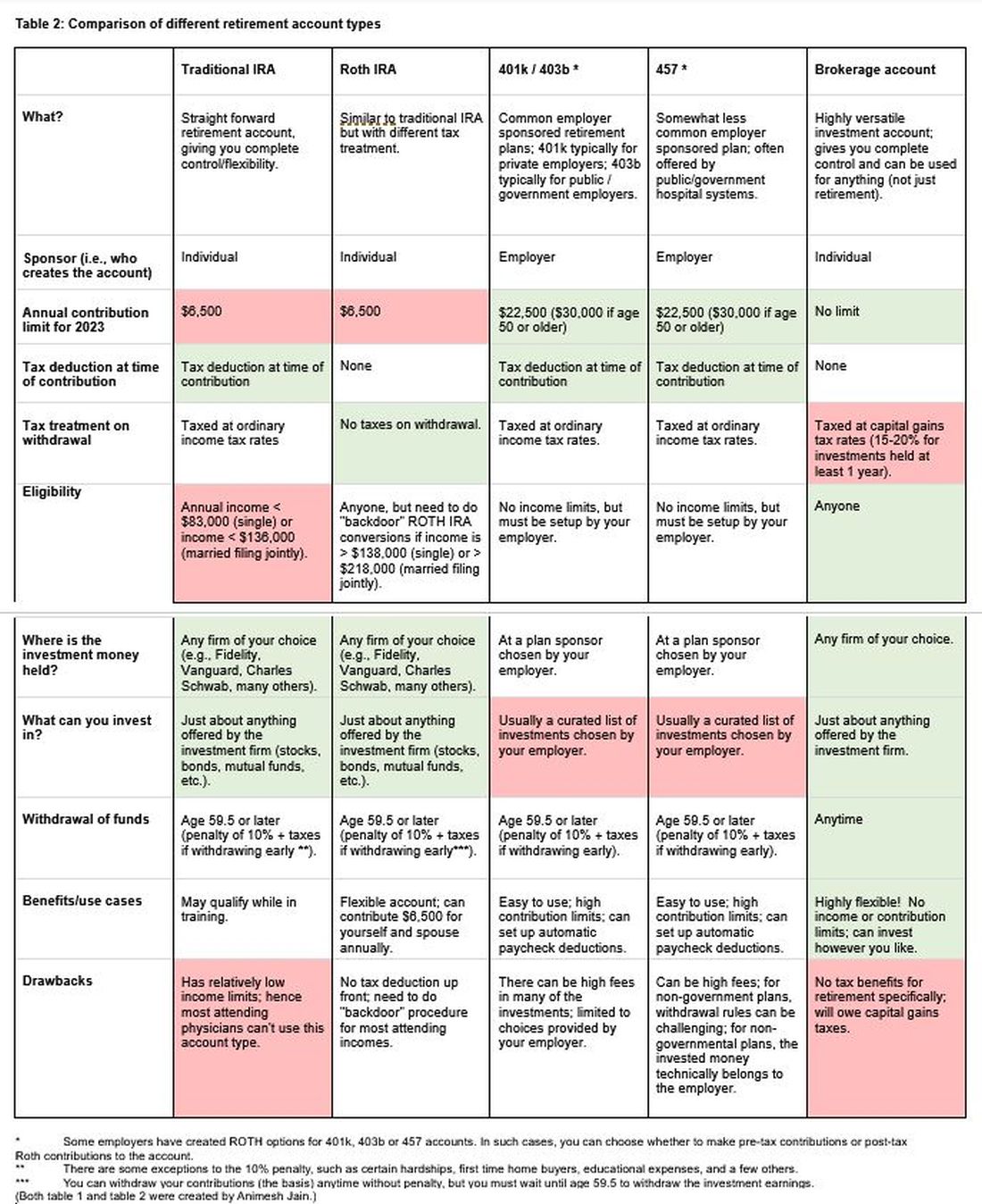

The alphabet soup of retirement accounts can be confusing – IRA, 401k, 457. Retirement accounts provide a tax break to incentivize saving for retirement. Traditional (“non-Roth”) accounts provide a tax break today, but you will pay taxes when withdrawing the money in retirement. Roth accounts provide no tax break now but provide tax-free growth for decades, and no taxes are due when withdrawing money. See table 2 for a detailed comparison of retirement accounts.

Once you place money into a retirement account, you will need to choose specific investments to grow your money. The two most common asset classes are stocks and bonds, though there are many other reasonable assets, such as real estate, commodities, and alternative currencies. It is generally recommended to have a higher proportion of stock-based investments early on (60%-90%) and then increase the ratio of bonds closer to retirement. Using low cost, passive index funds (or exchange traded funds) is a good way to get stock exposure. Target date retirement funds can be a nice tool for beginning investors since they will automatically adjust the stock/bond ratio for you.

Calculating the amount needed for retirement is beyond the scope of this article. However, saving at least 20% of your gross income specifically for retirement is a good starting point and should set you up for a reasonable retirement in about 30 years. For the average GI physician, this would mean saving $4,000 or more per month for retirement. If you aim to retire earlier, consider investing a higher percentage.

5. What do I need to know about buying a house?

The first question to ask is whether it makes sense to rent or buy a house. This is a personal and lifestyle decision, not just a financial decision. Today’s market is difficult with both high home prices and high rent costs. If there is a reasonable chance that you will be moving within 3-5 years, I would consider not buying until your long-term plans are more stable. Moreover, a high proportion of physicians change jobs.4,5,6 If you are just starting a new job, it is often wise to wait at least 6-12 months before buying a house to ensure the new job is a good fit. If you are in a stable long-term situation, it may be reasonable to buy a house. While it is commonly believed that buying a house is a “good financial move,” there are many hidden costs to home ownership, including big ticket repairs, property taxes, and real estate fees when selling a home.

First-time physician home buyers can often secure a physician mortgage with competitive interest rates and a low down payment of 0%-10% instead of the traditional 20% down payment. Moreover, a good physician mortgage should not have private mortgage insurance (PMI). Given the variation between mortgage companies, my most important piece of advice is to shop around for a good mortgage. An independent mortgage broker can be very valuable.

Dr. Jain is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He has no conflicts of interest. The information in this article is meant for general educational purposes only. For individualized personal finance advice, please seek your own financial advisor, tax accountant, insurance broker, attorney, or other financial professional. Follow Dr. Jain @AJainMD on X.

References

1. Future of PSLF Fact Sheet

2. The Loophole That Can Get Thousands of Doctors into PSLF

3. Student loan management: An introduction for the young gastroenterologist

4. Study Shows First Job after Medical Residency Often Doesn’t Last

5. More physicians want to leave their jobs as pay rates fall, survey finds

6. Physician turnover rates are climbing as they clamor for better work-life balance

While this article will get you started, these are complex topics, and each could warrant several standalone articles. I strongly encourage you to develop some basic understanding of personal finance through books, websites, and podcasts. If you can manage Barrett’s esophagus, Crohn’s, and cirrhosis, you can understand the basics of personal finance.

1. What should I do about my student loans? Go for public service loan forgiveness or pay them off?

The first step is knowing your debt burden, knowing your options, and developing a plan to pay off student loans. Public service loan forgiveness (PSLF) can be a good option in many situations. For borrowers staying in academic or other 501(c)(3) positions, PSLF is often an obvious move. Importantly, a fall 2022 statement by the U.S. Department of Education clarified that physicians working as contractors for nonprofit hospitals in California and Texas may now qualify for PSLF.1,2

For trainees debating an academic/501(c)(3) position vs. private practice, I would generally not advise making a career choice based purely on PSLF eligibility. However, borrowers with very high federal student loan burdens (e.g., debt to income ratio of > 2:1), or who are very close to the PSLF 10-year requirement may want to consider choosing a qualifying position for a few years to receive PSLF student loan forgiveness. Please see TNG’s 2020 article3 for a deeper discussion. Consultation with a company specializing in student loan advice for physicians may be well worth the upfront cost.

2. Do I need disability insurance? What should I look for?

I would strongly advise getting disability insurance as soon as possible (including while in training). While disability insurance is not cheap, it is one of the first steps you should take and one of the most important ways to protect your financial future. It is essential to look for a specialty-specific own occupation policy. Such a policy will provide disability payments if you are no longer able to work as a gastroenterologist/hepatologist (including an injury which prevents you from doing endoscopies).

There are two major types of disability policies: group policies and individual policies. See table 1 for a detailed comparison.

Your hospital/employer may provide a group policy at a heavily subsidized rate. Alternatively, you can purchase an individual disability policy, which is independent of your employer and will stay with you even if you change jobs. Currently, the only companies providing high quality own-occupation policies for physicians are Mass Mutual, Principal, Guardian, The Standard, and Ameritas. Because disability insurance is complicated, it is highly advisable to work with an agent experienced in physician disability policies.

Importantly, even if you have a group disability policy, you can purchase an individual policy as a supplement to provide extra coverage. If you leave employers, the individual policy can then become your primary disability policy without any additional medical underwriting.

3. Do I need life insurance? What type should I get?