User login

Addressing an unmet need in IBD patients: Treatment of acute abdominal pain

In the acute care setting, providers of care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are often faced with the dilemma of providing effective abdominal pain management in a population that has worse outcomes with both opioid and NSAID therapy. There is increased mortality associated with opioid use and risk of disease relapse with NSAID use in IBD patients.1,2 Due to this, patients often feel that their pain is inadequately addressed.3,4 There are multiple sources of abdominal pain in IBD, and understanding the mechanisms and presentations can help identify effective treatments. We will review pharmacologic and supportive therapies to optimize pain management in IBD.

Common pain presentations in IBD

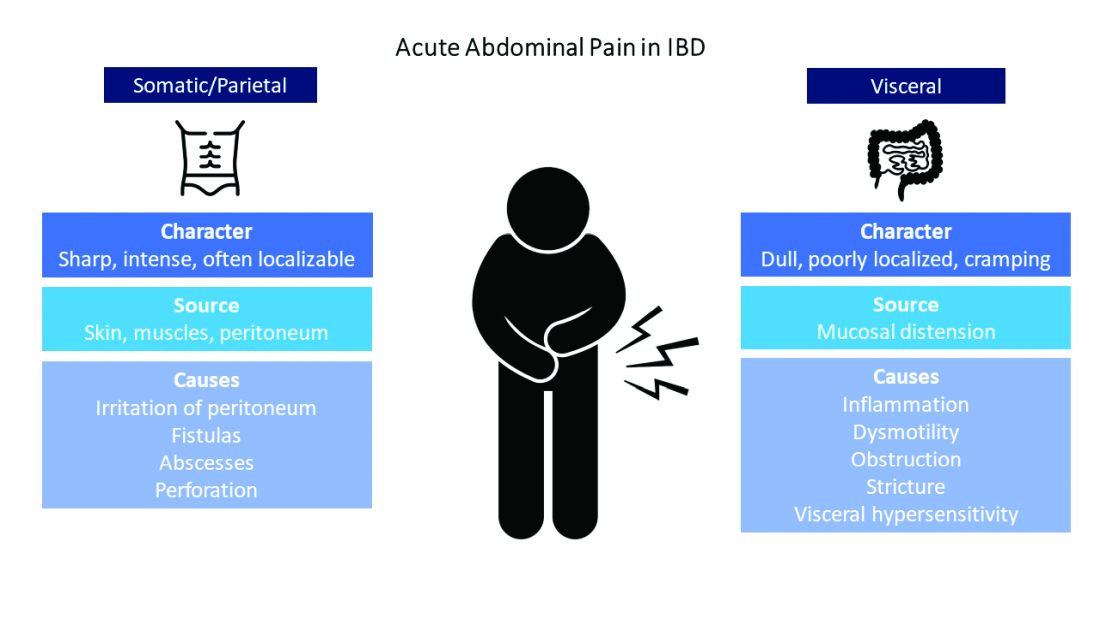

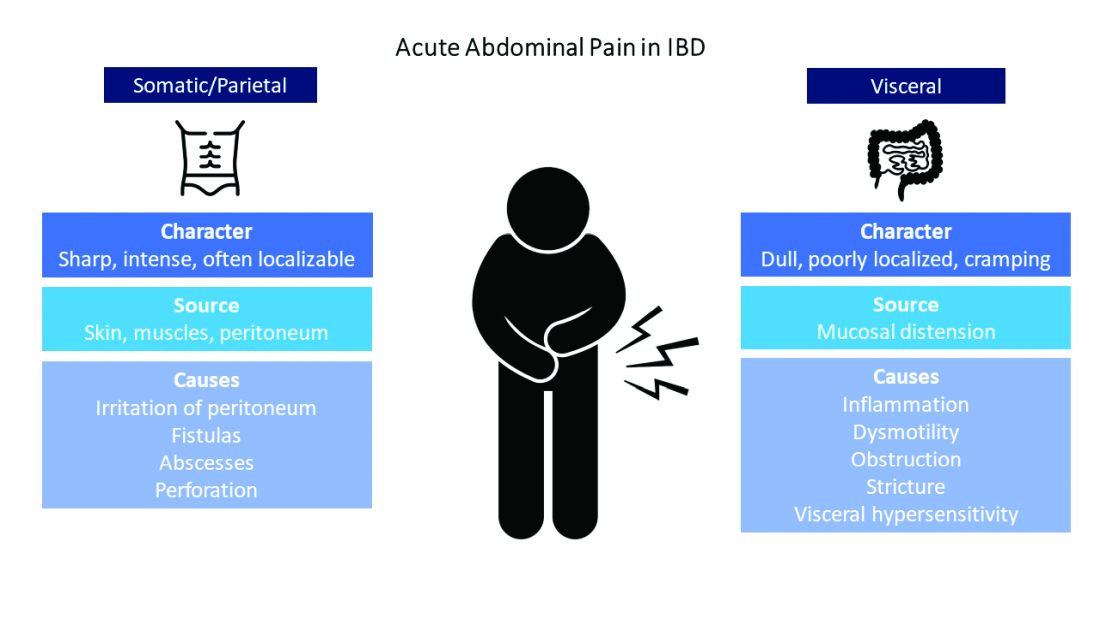

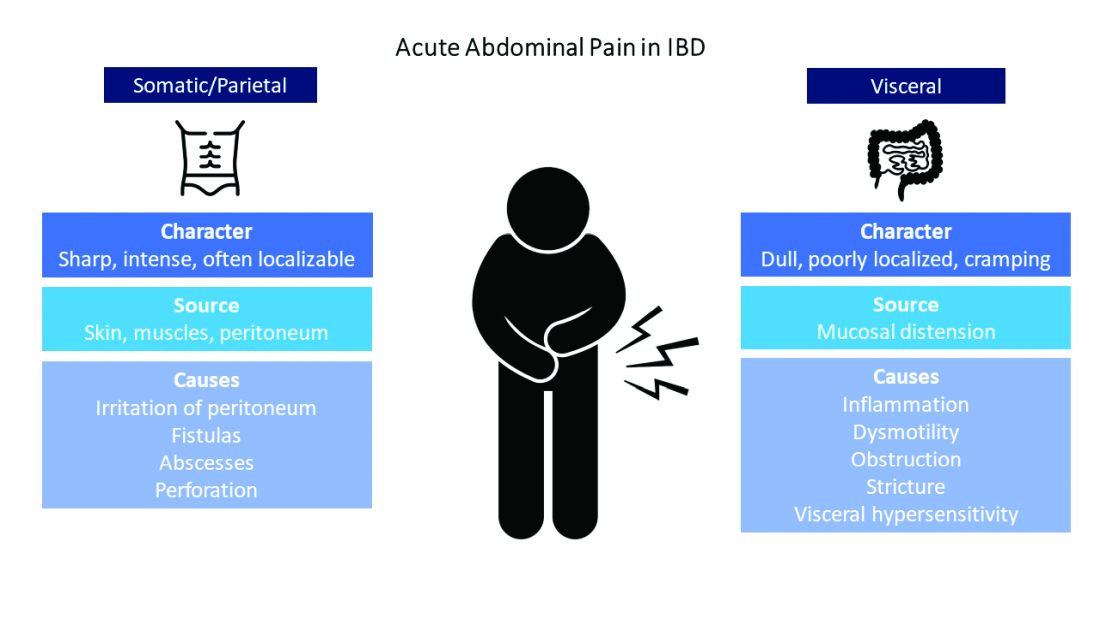

Visceral pain is a dull, poorly localized, cramping pain from intestinal distension. It is associated with inflammation, dysmotility, obstruction, and visceral hypersensitivity. Somatic and parietal pain is sharp, intense, and often localizable. Somatic pain originates from surrounding skin or muscles, and parietal pain arises from irritation of the peritoneum.5 We will review two common pain presentations in IBD.

Case 1: Mr. A is a 32-year-old male with stricturing small bowel Crohn’s disease s/p small bowel resection, who presents to the ED with 3 days of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. C-reactive protein is elevated to 6.8 mg/dL (normal 0.0 – 0.6 mg/dL), and CT is consistent with active small bowel inflammation, intraabdominal abscess at the anastomosis, and associated partial small bowel obstruction. He describes a sharp, intense abdominal pain with cramping. His exam is significant for diffuse abdominal tenderness and distension.

Case 2: Ms. B is a 28-year-old female with ulcerative colitis on mesalamine monotherapy who presents to the hospital for rectal bleeding and cramping abdominal pain. After 3 days of IV steroids her rectal bleeding has resolved, and CRP has normalized. However, she continues to have dull, cramping abdominal pain. Ibuprofen has improved this pain in the past.

Mr. A is having somatic pain from inflammation, abscess, and partial bowel obstruction. He also has visceral pain from luminal distension proximal to the obstruction. Ms. B is having visceral pain despite resolution of inflammation, which may be from postinflammatory visceral hypersensitivity.

Etiologies of pain

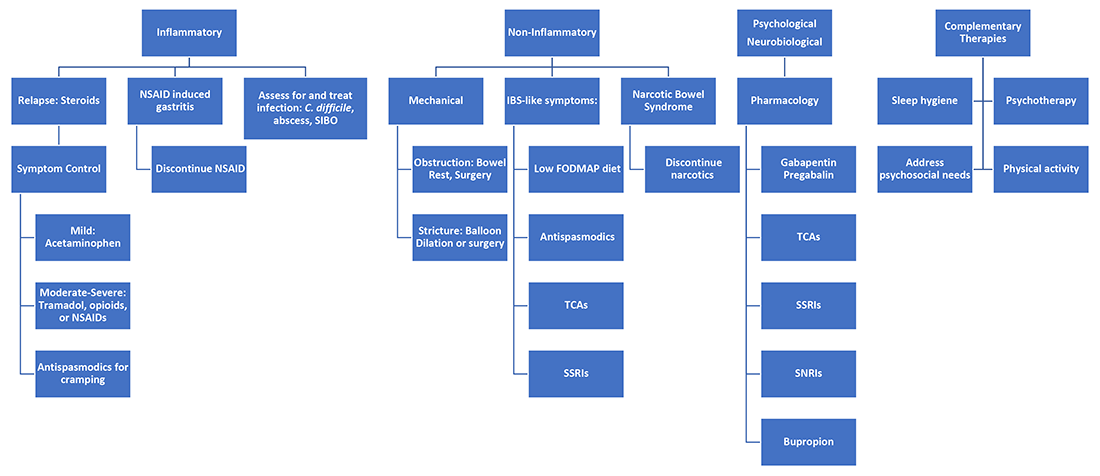

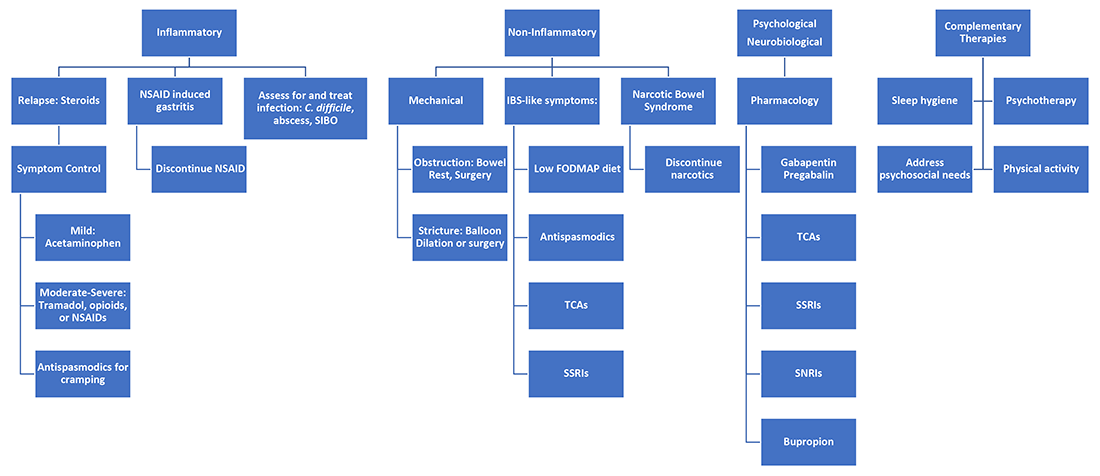

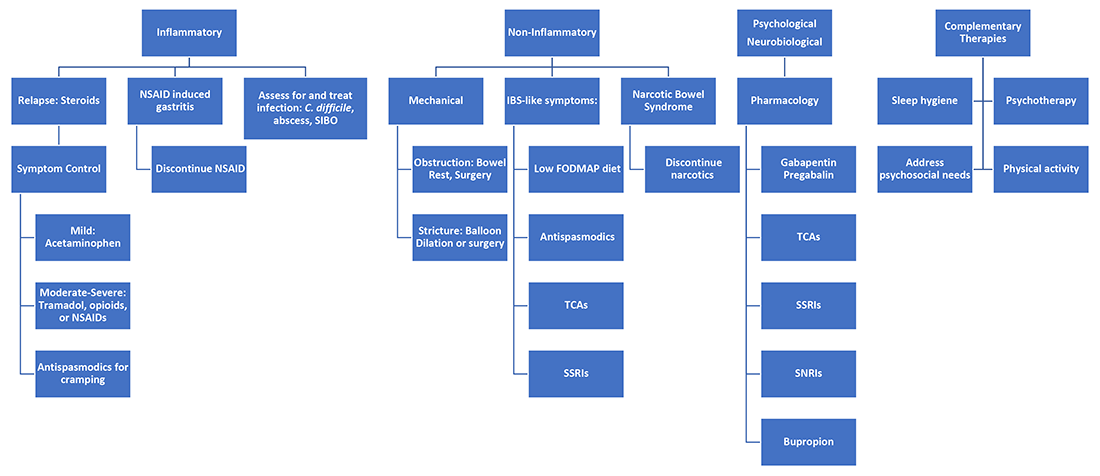

It’s best to group pain etiologies into inflammatory and noninflammatory causes. Inflammatory pain can be secondary to infection, such as abscess or enteric infection, active bowel inflammation, or disease complications (that is, enteric fistula). It is important to recognize that patients with active inflammation may also have noninflammatory pain. These include small bowel obstruction, strictures, adhesions, narcotic bowel syndrome, bacterial overgrowth, and visceral hypersensitivity. See figure 1.

The brain-gut connection matters

Abdominal pain in IBD patients starts from painful stimuli in the gut. In addition to direct pain pathways, multiple areas of the brain modulate perception of pain.6 Patients with psychiatric comorbidities have increased perception of abdominal pain.7 In fact, high perceived stress is associated with disease relapse.8 Treatment of psychiatric disorders improves these symptoms with lasting effects.9 Addressing psychological and psychosocial needs is essential to successful pain management with long-term effect on quality of life and pain perception in IBD patients.

What are my options?

When IBD patients present with acute abdominal pain, it is important to directly address their pain as one of your primary concerns and provide them with a management plan. While this seems obvious, it is not routinely done.3-4

Next, it is important to identify the cause, whether it be infection, obstruction, active inflammation, or functional abdominal pain. In the case of active disease, in addition to steroids and optimization of IBD therapies, acetaminophen and antispasmodics can be used for initial pain management. Supportive therapies include sleep hygiene, physical activity, and psychotherapy. If initial treatments are unsuccessful in the acute setting, and presentation is consistent with somatic pain, it may be necessary to escalate to tramadol, opioid, or NSAID therapy. For visceral pain, a neuromodulator, such as a tricyclic antidepressant or gabapentin, may have greater effect. Bupropion, SNRIs, and SSRIs are options; however, they may not be effective in the acute setting. More recent focus in the IBD community has questioned the role of cannabinoids on pain in IBD patients. Cannabis has been shown in a few small studies to provide pain relief in IBD patients with active inflammation.10-11 In patients with mechanical causes for pain, management of obstruction is an important part of the treatment plan.

Let’s talk about opioids in IBD patients

Chronic narcotic use in IBD is associated with worse outcomes. So when is it okay to use opioid therapies in IBD patients? Postoperative patients, patients with severe perianal disease, or those who fail alternative pain management strategies may require opioid medications. The association with mortality and opioids in IBD is with patients who require moderate to heavy use, which is defined as being prescribed opioids more than once a year. Opioid use in IBD patients is also associated with increased risk of readmissions and poor surgical outcomes.12-13 Tramadol does not have increased mortality risk.1 If selecting opioid therapy in managing pain in IBD, it is important to define the course of therapy, with a clear goal of discontinuation after the acute episode. Opioids should be used in tandem with alternative strategies. Patients should be counseled on the synergistic effect of acetaminophen with opioids, which may allow lower effective doses of opioids.

What about NSAID use in IBD patients?

NSAIDs have negative effects in the gastrointestinal tract due to inhibition of protective prostaglandins. They also alter the gut microbiome, although clinical implications of this are unknown.14 A small study showed that IBD patients who used NSAIDs had increased risk of disease relapse.2 Symptoms of relapse would present within 2-9 days of exposure; however, most had resolution of symptoms within 2-11 days of discontinuation.2 Follow-up studies have not reliably found that NSAIDs are associated with disease relapse.8 and thus NSAIDs may be used sparingly if needed in the acute setting.

Case Review: How do we approach Mr. A and Ms. B?

Mr. A presented with a partial small bowel obstruction and abscess. His pain presentation was consistent with both visceral and somatic pain etiologies. In addition to treating active inflammation and infection, bowel rest, acetaminophen, and antispasmodics can be initiated for pain control. Concomitantly, gabapentin, TCA, or SNRI can be initiated for neurobiological pain but may have limited benefit in the acute hospitalized setting. Social work may identify needs that affect pain perception and assist in addressing those needs. If abdominal pain persists, tramadol or hydrocodone-acetaminophen can be considered.

Ms. B presented with disease relapse, but despite improving inflammatory markers she had continued cramping abdominal pain, which can be consistent with visceral hypersensitivity. Antispasmodic and neuromodulating agents, such as a TCA, could be effective. We can recommend discontinuation of chronic ibuprofen due to risk of intestinal inflammation. Patients may inquire about adjuvant cannabis in pain management. While cannabis can be considered, further research is needed to recommend its regular use.

Conclusion

Acute abdominal pain management in IBD can be challenging for providers when typical options are limited in this population. Addressing inflammatory, mechanical, neurobiological, and psychological influences is vital to appropriately address pain. Having a structured plan for pain management in IBD can improve outcomes by decreasing recurrent hospitalizations and use of opioids.15 Figure 2 presents an overview.

Dr. Ahmed is a second-year internal medicine resident at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Kinnucan is with the department of internal medicine and the division of gastroenterology and hepatology and is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, both at the University of Michigan. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Burr NE et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr;16(4):534-41.e6.

2. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

3. Bernhofer EI et al. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017 May/Jun;40(3):200-7.

4. Zeitz J et al. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 22;11(6):e0156666.

5. Srinath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014 Dec;20(12):2433-49.

6. Docherty MJ et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011 Sep;7(9):592-601.

7. Elsenbruch S et al. Gut. 2010 Apr;59(4):489-95.

8. Bernstein CN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):1994-2002.

9. Palsson OS and Whitehead WE. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Mar;11(3):208-16; quiz e22-3.

10. Swaminath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar; 25(3):427-35.

11. Naftali T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;11(10):1276-80.e1.

12. Sultan K and Swaminath A. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Sep 16;14(9):1188-89.

13. Hirsch A et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Oct;19(10):1852-61.

14. Rogers MAM and Aronoff DM. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):178.e1-178.e9.

15. Kaimakliotis P et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Jun;36(6):1193-200.

In the acute care setting, providers of care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are often faced with the dilemma of providing effective abdominal pain management in a population that has worse outcomes with both opioid and NSAID therapy. There is increased mortality associated with opioid use and risk of disease relapse with NSAID use in IBD patients.1,2 Due to this, patients often feel that their pain is inadequately addressed.3,4 There are multiple sources of abdominal pain in IBD, and understanding the mechanisms and presentations can help identify effective treatments. We will review pharmacologic and supportive therapies to optimize pain management in IBD.

Common pain presentations in IBD

Visceral pain is a dull, poorly localized, cramping pain from intestinal distension. It is associated with inflammation, dysmotility, obstruction, and visceral hypersensitivity. Somatic and parietal pain is sharp, intense, and often localizable. Somatic pain originates from surrounding skin or muscles, and parietal pain arises from irritation of the peritoneum.5 We will review two common pain presentations in IBD.

Case 1: Mr. A is a 32-year-old male with stricturing small bowel Crohn’s disease s/p small bowel resection, who presents to the ED with 3 days of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. C-reactive protein is elevated to 6.8 mg/dL (normal 0.0 – 0.6 mg/dL), and CT is consistent with active small bowel inflammation, intraabdominal abscess at the anastomosis, and associated partial small bowel obstruction. He describes a sharp, intense abdominal pain with cramping. His exam is significant for diffuse abdominal tenderness and distension.

Case 2: Ms. B is a 28-year-old female with ulcerative colitis on mesalamine monotherapy who presents to the hospital for rectal bleeding and cramping abdominal pain. After 3 days of IV steroids her rectal bleeding has resolved, and CRP has normalized. However, she continues to have dull, cramping abdominal pain. Ibuprofen has improved this pain in the past.

Mr. A is having somatic pain from inflammation, abscess, and partial bowel obstruction. He also has visceral pain from luminal distension proximal to the obstruction. Ms. B is having visceral pain despite resolution of inflammation, which may be from postinflammatory visceral hypersensitivity.

Etiologies of pain

It’s best to group pain etiologies into inflammatory and noninflammatory causes. Inflammatory pain can be secondary to infection, such as abscess or enteric infection, active bowel inflammation, or disease complications (that is, enteric fistula). It is important to recognize that patients with active inflammation may also have noninflammatory pain. These include small bowel obstruction, strictures, adhesions, narcotic bowel syndrome, bacterial overgrowth, and visceral hypersensitivity. See figure 1.

The brain-gut connection matters

Abdominal pain in IBD patients starts from painful stimuli in the gut. In addition to direct pain pathways, multiple areas of the brain modulate perception of pain.6 Patients with psychiatric comorbidities have increased perception of abdominal pain.7 In fact, high perceived stress is associated with disease relapse.8 Treatment of psychiatric disorders improves these symptoms with lasting effects.9 Addressing psychological and psychosocial needs is essential to successful pain management with long-term effect on quality of life and pain perception in IBD patients.

What are my options?

When IBD patients present with acute abdominal pain, it is important to directly address their pain as one of your primary concerns and provide them with a management plan. While this seems obvious, it is not routinely done.3-4

Next, it is important to identify the cause, whether it be infection, obstruction, active inflammation, or functional abdominal pain. In the case of active disease, in addition to steroids and optimization of IBD therapies, acetaminophen and antispasmodics can be used for initial pain management. Supportive therapies include sleep hygiene, physical activity, and psychotherapy. If initial treatments are unsuccessful in the acute setting, and presentation is consistent with somatic pain, it may be necessary to escalate to tramadol, opioid, or NSAID therapy. For visceral pain, a neuromodulator, such as a tricyclic antidepressant or gabapentin, may have greater effect. Bupropion, SNRIs, and SSRIs are options; however, they may not be effective in the acute setting. More recent focus in the IBD community has questioned the role of cannabinoids on pain in IBD patients. Cannabis has been shown in a few small studies to provide pain relief in IBD patients with active inflammation.10-11 In patients with mechanical causes for pain, management of obstruction is an important part of the treatment plan.

Let’s talk about opioids in IBD patients

Chronic narcotic use in IBD is associated with worse outcomes. So when is it okay to use opioid therapies in IBD patients? Postoperative patients, patients with severe perianal disease, or those who fail alternative pain management strategies may require opioid medications. The association with mortality and opioids in IBD is with patients who require moderate to heavy use, which is defined as being prescribed opioids more than once a year. Opioid use in IBD patients is also associated with increased risk of readmissions and poor surgical outcomes.12-13 Tramadol does not have increased mortality risk.1 If selecting opioid therapy in managing pain in IBD, it is important to define the course of therapy, with a clear goal of discontinuation after the acute episode. Opioids should be used in tandem with alternative strategies. Patients should be counseled on the synergistic effect of acetaminophen with opioids, which may allow lower effective doses of opioids.

What about NSAID use in IBD patients?

NSAIDs have negative effects in the gastrointestinal tract due to inhibition of protective prostaglandins. They also alter the gut microbiome, although clinical implications of this are unknown.14 A small study showed that IBD patients who used NSAIDs had increased risk of disease relapse.2 Symptoms of relapse would present within 2-9 days of exposure; however, most had resolution of symptoms within 2-11 days of discontinuation.2 Follow-up studies have not reliably found that NSAIDs are associated with disease relapse.8 and thus NSAIDs may be used sparingly if needed in the acute setting.

Case Review: How do we approach Mr. A and Ms. B?

Mr. A presented with a partial small bowel obstruction and abscess. His pain presentation was consistent with both visceral and somatic pain etiologies. In addition to treating active inflammation and infection, bowel rest, acetaminophen, and antispasmodics can be initiated for pain control. Concomitantly, gabapentin, TCA, or SNRI can be initiated for neurobiological pain but may have limited benefit in the acute hospitalized setting. Social work may identify needs that affect pain perception and assist in addressing those needs. If abdominal pain persists, tramadol or hydrocodone-acetaminophen can be considered.

Ms. B presented with disease relapse, but despite improving inflammatory markers she had continued cramping abdominal pain, which can be consistent with visceral hypersensitivity. Antispasmodic and neuromodulating agents, such as a TCA, could be effective. We can recommend discontinuation of chronic ibuprofen due to risk of intestinal inflammation. Patients may inquire about adjuvant cannabis in pain management. While cannabis can be considered, further research is needed to recommend its regular use.

Conclusion

Acute abdominal pain management in IBD can be challenging for providers when typical options are limited in this population. Addressing inflammatory, mechanical, neurobiological, and psychological influences is vital to appropriately address pain. Having a structured plan for pain management in IBD can improve outcomes by decreasing recurrent hospitalizations and use of opioids.15 Figure 2 presents an overview.

Dr. Ahmed is a second-year internal medicine resident at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Kinnucan is with the department of internal medicine and the division of gastroenterology and hepatology and is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, both at the University of Michigan. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Burr NE et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr;16(4):534-41.e6.

2. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

3. Bernhofer EI et al. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017 May/Jun;40(3):200-7.

4. Zeitz J et al. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 22;11(6):e0156666.

5. Srinath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014 Dec;20(12):2433-49.

6. Docherty MJ et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011 Sep;7(9):592-601.

7. Elsenbruch S et al. Gut. 2010 Apr;59(4):489-95.

8. Bernstein CN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):1994-2002.

9. Palsson OS and Whitehead WE. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Mar;11(3):208-16; quiz e22-3.

10. Swaminath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar; 25(3):427-35.

11. Naftali T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;11(10):1276-80.e1.

12. Sultan K and Swaminath A. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Sep 16;14(9):1188-89.

13. Hirsch A et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Oct;19(10):1852-61.

14. Rogers MAM and Aronoff DM. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):178.e1-178.e9.

15. Kaimakliotis P et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Jun;36(6):1193-200.

In the acute care setting, providers of care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are often faced with the dilemma of providing effective abdominal pain management in a population that has worse outcomes with both opioid and NSAID therapy. There is increased mortality associated with opioid use and risk of disease relapse with NSAID use in IBD patients.1,2 Due to this, patients often feel that their pain is inadequately addressed.3,4 There are multiple sources of abdominal pain in IBD, and understanding the mechanisms and presentations can help identify effective treatments. We will review pharmacologic and supportive therapies to optimize pain management in IBD.

Common pain presentations in IBD

Visceral pain is a dull, poorly localized, cramping pain from intestinal distension. It is associated with inflammation, dysmotility, obstruction, and visceral hypersensitivity. Somatic and parietal pain is sharp, intense, and often localizable. Somatic pain originates from surrounding skin or muscles, and parietal pain arises from irritation of the peritoneum.5 We will review two common pain presentations in IBD.

Case 1: Mr. A is a 32-year-old male with stricturing small bowel Crohn’s disease s/p small bowel resection, who presents to the ED with 3 days of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. C-reactive protein is elevated to 6.8 mg/dL (normal 0.0 – 0.6 mg/dL), and CT is consistent with active small bowel inflammation, intraabdominal abscess at the anastomosis, and associated partial small bowel obstruction. He describes a sharp, intense abdominal pain with cramping. His exam is significant for diffuse abdominal tenderness and distension.

Case 2: Ms. B is a 28-year-old female with ulcerative colitis on mesalamine monotherapy who presents to the hospital for rectal bleeding and cramping abdominal pain. After 3 days of IV steroids her rectal bleeding has resolved, and CRP has normalized. However, she continues to have dull, cramping abdominal pain. Ibuprofen has improved this pain in the past.

Mr. A is having somatic pain from inflammation, abscess, and partial bowel obstruction. He also has visceral pain from luminal distension proximal to the obstruction. Ms. B is having visceral pain despite resolution of inflammation, which may be from postinflammatory visceral hypersensitivity.

Etiologies of pain

It’s best to group pain etiologies into inflammatory and noninflammatory causes. Inflammatory pain can be secondary to infection, such as abscess or enteric infection, active bowel inflammation, or disease complications (that is, enteric fistula). It is important to recognize that patients with active inflammation may also have noninflammatory pain. These include small bowel obstruction, strictures, adhesions, narcotic bowel syndrome, bacterial overgrowth, and visceral hypersensitivity. See figure 1.

The brain-gut connection matters

Abdominal pain in IBD patients starts from painful stimuli in the gut. In addition to direct pain pathways, multiple areas of the brain modulate perception of pain.6 Patients with psychiatric comorbidities have increased perception of abdominal pain.7 In fact, high perceived stress is associated with disease relapse.8 Treatment of psychiatric disorders improves these symptoms with lasting effects.9 Addressing psychological and psychosocial needs is essential to successful pain management with long-term effect on quality of life and pain perception in IBD patients.

What are my options?

When IBD patients present with acute abdominal pain, it is important to directly address their pain as one of your primary concerns and provide them with a management plan. While this seems obvious, it is not routinely done.3-4

Next, it is important to identify the cause, whether it be infection, obstruction, active inflammation, or functional abdominal pain. In the case of active disease, in addition to steroids and optimization of IBD therapies, acetaminophen and antispasmodics can be used for initial pain management. Supportive therapies include sleep hygiene, physical activity, and psychotherapy. If initial treatments are unsuccessful in the acute setting, and presentation is consistent with somatic pain, it may be necessary to escalate to tramadol, opioid, or NSAID therapy. For visceral pain, a neuromodulator, such as a tricyclic antidepressant or gabapentin, may have greater effect. Bupropion, SNRIs, and SSRIs are options; however, they may not be effective in the acute setting. More recent focus in the IBD community has questioned the role of cannabinoids on pain in IBD patients. Cannabis has been shown in a few small studies to provide pain relief in IBD patients with active inflammation.10-11 In patients with mechanical causes for pain, management of obstruction is an important part of the treatment plan.

Let’s talk about opioids in IBD patients

Chronic narcotic use in IBD is associated with worse outcomes. So when is it okay to use opioid therapies in IBD patients? Postoperative patients, patients with severe perianal disease, or those who fail alternative pain management strategies may require opioid medications. The association with mortality and opioids in IBD is with patients who require moderate to heavy use, which is defined as being prescribed opioids more than once a year. Opioid use in IBD patients is also associated with increased risk of readmissions and poor surgical outcomes.12-13 Tramadol does not have increased mortality risk.1 If selecting opioid therapy in managing pain in IBD, it is important to define the course of therapy, with a clear goal of discontinuation after the acute episode. Opioids should be used in tandem with alternative strategies. Patients should be counseled on the synergistic effect of acetaminophen with opioids, which may allow lower effective doses of opioids.

What about NSAID use in IBD patients?

NSAIDs have negative effects in the gastrointestinal tract due to inhibition of protective prostaglandins. They also alter the gut microbiome, although clinical implications of this are unknown.14 A small study showed that IBD patients who used NSAIDs had increased risk of disease relapse.2 Symptoms of relapse would present within 2-9 days of exposure; however, most had resolution of symptoms within 2-11 days of discontinuation.2 Follow-up studies have not reliably found that NSAIDs are associated with disease relapse.8 and thus NSAIDs may be used sparingly if needed in the acute setting.

Case Review: How do we approach Mr. A and Ms. B?

Mr. A presented with a partial small bowel obstruction and abscess. His pain presentation was consistent with both visceral and somatic pain etiologies. In addition to treating active inflammation and infection, bowel rest, acetaminophen, and antispasmodics can be initiated for pain control. Concomitantly, gabapentin, TCA, or SNRI can be initiated for neurobiological pain but may have limited benefit in the acute hospitalized setting. Social work may identify needs that affect pain perception and assist in addressing those needs. If abdominal pain persists, tramadol or hydrocodone-acetaminophen can be considered.

Ms. B presented with disease relapse, but despite improving inflammatory markers she had continued cramping abdominal pain, which can be consistent with visceral hypersensitivity. Antispasmodic and neuromodulating agents, such as a TCA, could be effective. We can recommend discontinuation of chronic ibuprofen due to risk of intestinal inflammation. Patients may inquire about adjuvant cannabis in pain management. While cannabis can be considered, further research is needed to recommend its regular use.

Conclusion

Acute abdominal pain management in IBD can be challenging for providers when typical options are limited in this population. Addressing inflammatory, mechanical, neurobiological, and psychological influences is vital to appropriately address pain. Having a structured plan for pain management in IBD can improve outcomes by decreasing recurrent hospitalizations and use of opioids.15 Figure 2 presents an overview.

Dr. Ahmed is a second-year internal medicine resident at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Kinnucan is with the department of internal medicine and the division of gastroenterology and hepatology and is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, both at the University of Michigan. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Burr NE et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr;16(4):534-41.e6.

2. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

3. Bernhofer EI et al. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017 May/Jun;40(3):200-7.

4. Zeitz J et al. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 22;11(6):e0156666.

5. Srinath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014 Dec;20(12):2433-49.

6. Docherty MJ et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011 Sep;7(9):592-601.

7. Elsenbruch S et al. Gut. 2010 Apr;59(4):489-95.

8. Bernstein CN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):1994-2002.

9. Palsson OS and Whitehead WE. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Mar;11(3):208-16; quiz e22-3.

10. Swaminath A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar; 25(3):427-35.

11. Naftali T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;11(10):1276-80.e1.

12. Sultan K and Swaminath A. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Sep 16;14(9):1188-89.

13. Hirsch A et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Oct;19(10):1852-61.

14. Rogers MAM and Aronoff DM. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):178.e1-178.e9.

15. Kaimakliotis P et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Jun;36(6):1193-200.

Serous and Hemorrhagic Bullae on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Fracture Blisters

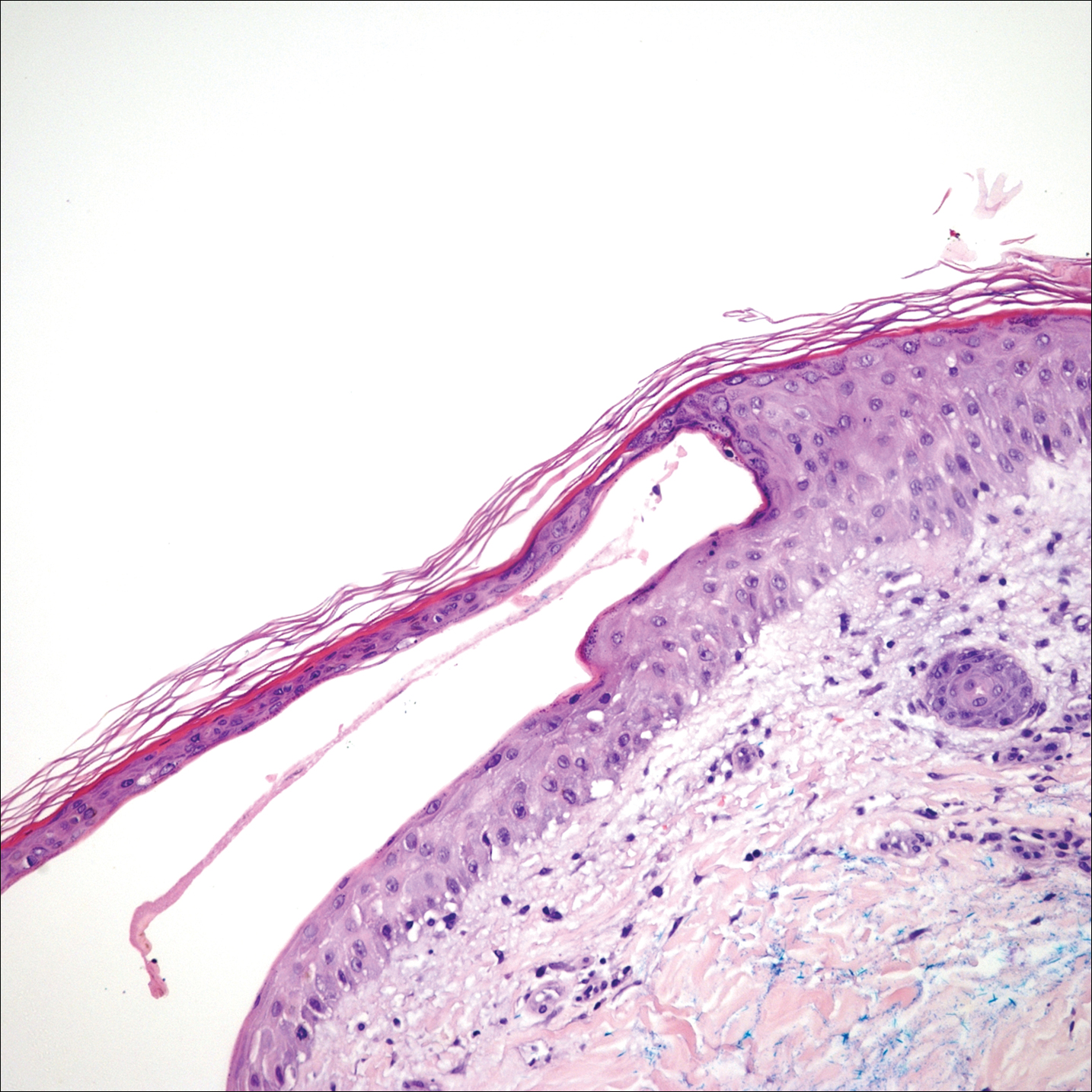

The shave biopsy pathology demonstrated a subepidermal bulla with re-epithelialization that was clinically consistent with fracture blisters (also known as fracture bullae)(Figure). Fracture blisters are a complication of bone fractures, usually occurring 24 to 48 hours after the trauma but possibly up to 3 weeks later. The skin usually is edematous with tense bullae overlying the fracture (in this case it was distal to the fracture); most blisters contain clear fluid, but older blisters tend to be more flaccid with hemorrhagic fluid.1 The cause is thought to be the result of skin strain during fracture formation.2 Edema and hypoxia from injured vessels and lymphatics contribute to the formation of bullae, which are seen as a dermoepidermal junction split on histology.1

The bullae are histologically indistinguishable from edema blisters. A clinical history can help to differentiate. Edema blisters occur in the setting of an acute exacerbation of chronic edema, usually on the lower extremities in the setting of fluid overload.3 Bullous cellulitis is associated with skin erythema, warmth, and systemic symptoms. Bullous pemphigoid can be localized to the lower legs at times; however, biopsy would show a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils along the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis can be drug induced from vancomycin; however, pathology would show a subepidermal blister with a neutrophil predominant infiltrate. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as naproxen are a common culprit for bullous drug eruptions, which can be localized or generalized and include diagnoses such as fixed drug eruption, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and drug-induced pseudoporphyria. Naproxen-induced pseudoporphyria more commonly presents with blisters, erosions, and scarring with a predilection for the dorsal hands. Histology also will demonstrate subepidermal bullae. Clues to differentiate pseudoporphyria from fracture blisters include festooning of the dermal papilla and caterpillar bodies consisting of basement membrane material and colloid bodies in the basal layer of the epidermis, though they are not always present.4

Fracture blisters can be localized to the injury site or extend beyond the fracture site. They usually are found where there is minimal subcutaneous tissue, such as the tibia, ankles, and elbows. Fractures treated within 24 hours are much less likely to have bullae formation.1 The bullae are sterile but may lead to wound healing complications, such as infections or delay in surgical management. However, there are no major adverse effects of postoperative fracture blisters.1 Fracture blisters are self-healing, though silver sulfadiazine has been shown to minimize soft-tissue complications by promoting re-epithelialization.5

- Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, et al. Fracture blisters: clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:417-427.

- Giordano CP, Scott D, Kummer F, et al. Fracture blister formation: a laboratory study. J Trauma. 1995;38:907-909.

- Mascaro JM. Other vesicobullous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schafer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:554-561.

- Patterson JW. The vesicobullous reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:135-187.

- Strauss EJ, Petrucelli G, Bong M, et al. Blisters associated with lower-extremity fracture: results of a prospective treatment protocol. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:618-622.

The Diagnosis: Fracture Blisters

The shave biopsy pathology demonstrated a subepidermal bulla with re-epithelialization that was clinically consistent with fracture blisters (also known as fracture bullae)(Figure). Fracture blisters are a complication of bone fractures, usually occurring 24 to 48 hours after the trauma but possibly up to 3 weeks later. The skin usually is edematous with tense bullae overlying the fracture (in this case it was distal to the fracture); most blisters contain clear fluid, but older blisters tend to be more flaccid with hemorrhagic fluid.1 The cause is thought to be the result of skin strain during fracture formation.2 Edema and hypoxia from injured vessels and lymphatics contribute to the formation of bullae, which are seen as a dermoepidermal junction split on histology.1

The bullae are histologically indistinguishable from edema blisters. A clinical history can help to differentiate. Edema blisters occur in the setting of an acute exacerbation of chronic edema, usually on the lower extremities in the setting of fluid overload.3 Bullous cellulitis is associated with skin erythema, warmth, and systemic symptoms. Bullous pemphigoid can be localized to the lower legs at times; however, biopsy would show a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils along the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis can be drug induced from vancomycin; however, pathology would show a subepidermal blister with a neutrophil predominant infiltrate. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as naproxen are a common culprit for bullous drug eruptions, which can be localized or generalized and include diagnoses such as fixed drug eruption, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and drug-induced pseudoporphyria. Naproxen-induced pseudoporphyria more commonly presents with blisters, erosions, and scarring with a predilection for the dorsal hands. Histology also will demonstrate subepidermal bullae. Clues to differentiate pseudoporphyria from fracture blisters include festooning of the dermal papilla and caterpillar bodies consisting of basement membrane material and colloid bodies in the basal layer of the epidermis, though they are not always present.4

Fracture blisters can be localized to the injury site or extend beyond the fracture site. They usually are found where there is minimal subcutaneous tissue, such as the tibia, ankles, and elbows. Fractures treated within 24 hours are much less likely to have bullae formation.1 The bullae are sterile but may lead to wound healing complications, such as infections or delay in surgical management. However, there are no major adverse effects of postoperative fracture blisters.1 Fracture blisters are self-healing, though silver sulfadiazine has been shown to minimize soft-tissue complications by promoting re-epithelialization.5

The Diagnosis: Fracture Blisters

The shave biopsy pathology demonstrated a subepidermal bulla with re-epithelialization that was clinically consistent with fracture blisters (also known as fracture bullae)(Figure). Fracture blisters are a complication of bone fractures, usually occurring 24 to 48 hours after the trauma but possibly up to 3 weeks later. The skin usually is edematous with tense bullae overlying the fracture (in this case it was distal to the fracture); most blisters contain clear fluid, but older blisters tend to be more flaccid with hemorrhagic fluid.1 The cause is thought to be the result of skin strain during fracture formation.2 Edema and hypoxia from injured vessels and lymphatics contribute to the formation of bullae, which are seen as a dermoepidermal junction split on histology.1

The bullae are histologically indistinguishable from edema blisters. A clinical history can help to differentiate. Edema blisters occur in the setting of an acute exacerbation of chronic edema, usually on the lower extremities in the setting of fluid overload.3 Bullous cellulitis is associated with skin erythema, warmth, and systemic symptoms. Bullous pemphigoid can be localized to the lower legs at times; however, biopsy would show a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils along the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis can be drug induced from vancomycin; however, pathology would show a subepidermal blister with a neutrophil predominant infiltrate. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as naproxen are a common culprit for bullous drug eruptions, which can be localized or generalized and include diagnoses such as fixed drug eruption, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and drug-induced pseudoporphyria. Naproxen-induced pseudoporphyria more commonly presents with blisters, erosions, and scarring with a predilection for the dorsal hands. Histology also will demonstrate subepidermal bullae. Clues to differentiate pseudoporphyria from fracture blisters include festooning of the dermal papilla and caterpillar bodies consisting of basement membrane material and colloid bodies in the basal layer of the epidermis, though they are not always present.4

Fracture blisters can be localized to the injury site or extend beyond the fracture site. They usually are found where there is minimal subcutaneous tissue, such as the tibia, ankles, and elbows. Fractures treated within 24 hours are much less likely to have bullae formation.1 The bullae are sterile but may lead to wound healing complications, such as infections or delay in surgical management. However, there are no major adverse effects of postoperative fracture blisters.1 Fracture blisters are self-healing, though silver sulfadiazine has been shown to minimize soft-tissue complications by promoting re-epithelialization.5

- Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, et al. Fracture blisters: clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:417-427.

- Giordano CP, Scott D, Kummer F, et al. Fracture blister formation: a laboratory study. J Trauma. 1995;38:907-909.

- Mascaro JM. Other vesicobullous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schafer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:554-561.

- Patterson JW. The vesicobullous reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:135-187.

- Strauss EJ, Petrucelli G, Bong M, et al. Blisters associated with lower-extremity fracture: results of a prospective treatment protocol. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:618-622.

- Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, et al. Fracture blisters: clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:417-427.

- Giordano CP, Scott D, Kummer F, et al. Fracture blister formation: a laboratory study. J Trauma. 1995;38:907-909.

- Mascaro JM. Other vesicobullous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schafer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:554-561.

- Patterson JW. The vesicobullous reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:135-187.

- Strauss EJ, Petrucelli G, Bong M, et al. Blisters associated with lower-extremity fracture: results of a prospective treatment protocol. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:618-622.

A 61-year-old wheelchair-bound man presented to the emergency department with increased swelling, bruising, and blister formation on the right lower leg over the last week. He had history of alcoholism and heavy smoking. Two weeks prior to presentation he had an open reduction and internal fixation of a right hip fracture. He recently started taking naproxen for pain and had taken a course of ciprofloxacin for a urinary tract infection. Physical examination showed a well-healed surgical wound along the right upper lateral thigh with no purulence or erythema. His right lower leg had extensive ecchymosis and pitting edema, and there was a cluster of well-defined, variably sized, serous and hemorrhagic bullae over the right lower ankle and dorsal aspect of the foot. He was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Due to initial concern of cellulitis, he was given a dose of vancomycin in the emergency department. Computed tomography of the right leg showed diffuse edematous changes consistent with the recent surgery, and duplex ultrasonography showed no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. A shave biopsy was performed.