User login

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

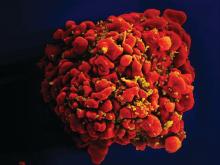

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.