User login

To the Editor:

A 14-year-old Black adolescent girl presented with episodic, painful, edematous plaques that occurred symmetrically on the arms and legs of 5 years’ duration. The plaques evolved into hyperpigmented patches within 24 to 48 hours before eventually resolving. Fatigue, headache, arthralgias of the arms and legs, chest pain, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting variably accompanied these episodes.

Prior to visiting our clinic, the patient had been seen by numerous specialists. A review of her medical records revealed an initial diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), then urticarial vasculitis. She had been treated with antihistamines, topical and systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, dapsone, azathioprine, and gabapentin. All treatments were ineffectual. She underwent extensive diagnostic testing and imaging, which were normal or noncontributory, including type I allergy testing; multiple exhaustive batteries of hematologic testing; and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvic region. Biopsies from symptomatic segments of the gastrointestinal tract were normal.

Chronic treatment with systemic steroids over 9 months resulted in gastritis and an episode of hematemesis requiring emergent hospitalization. A lengthy multidisciplinary evaluation was conducted at the patient’s local community hospital; the team concluded that she had an urticarial-type rash with accompanying symptoms that did not have an autoimmune, rheumatologic, or inflammatory basis.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for recent-onset panic attacks. Her family medical history was noncontributory. Physical examination revealed multiple violaceous hyperpigmented patches diffusely located on the proximal upper arms (Figure 1). There were no additional findings on physical examination.

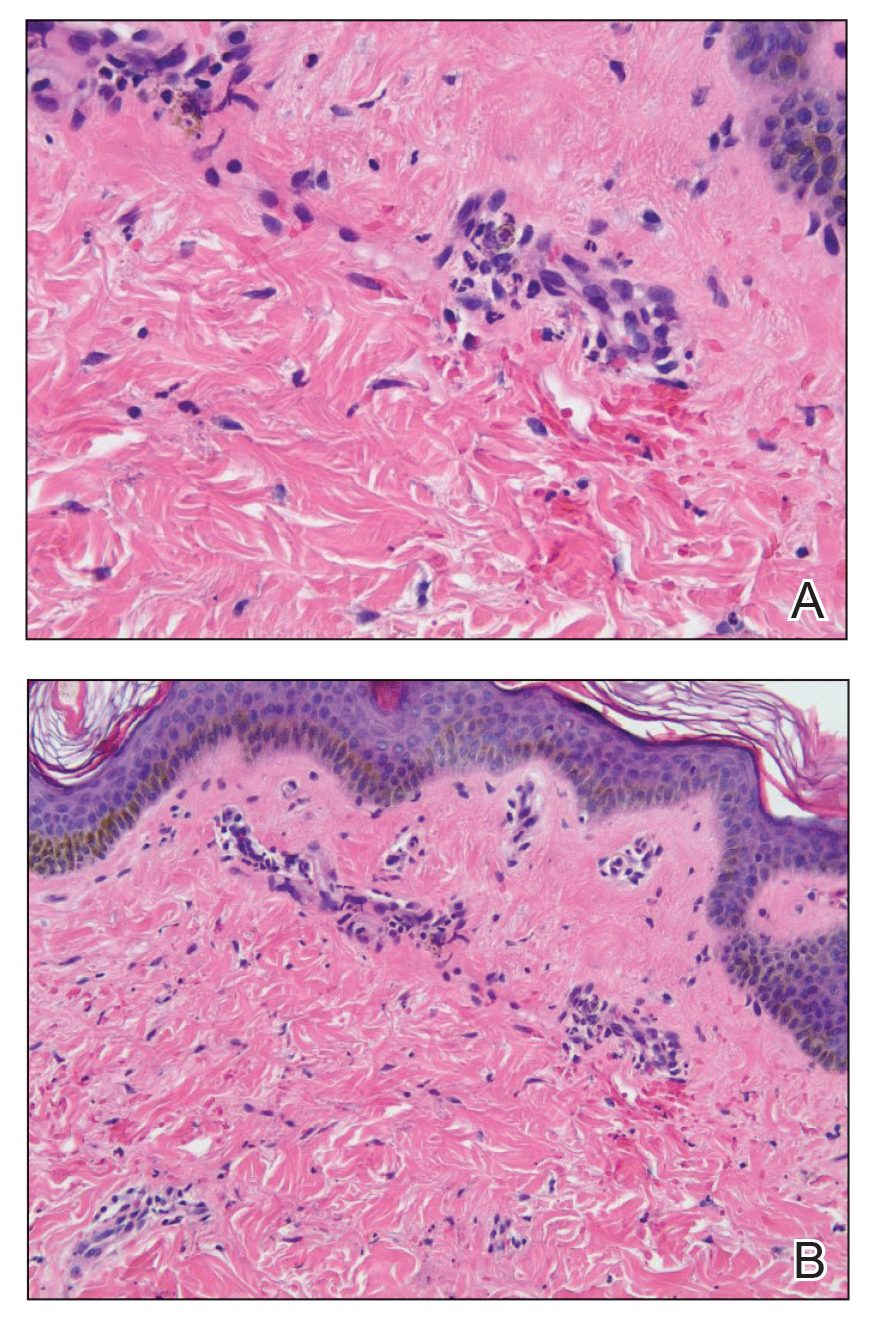

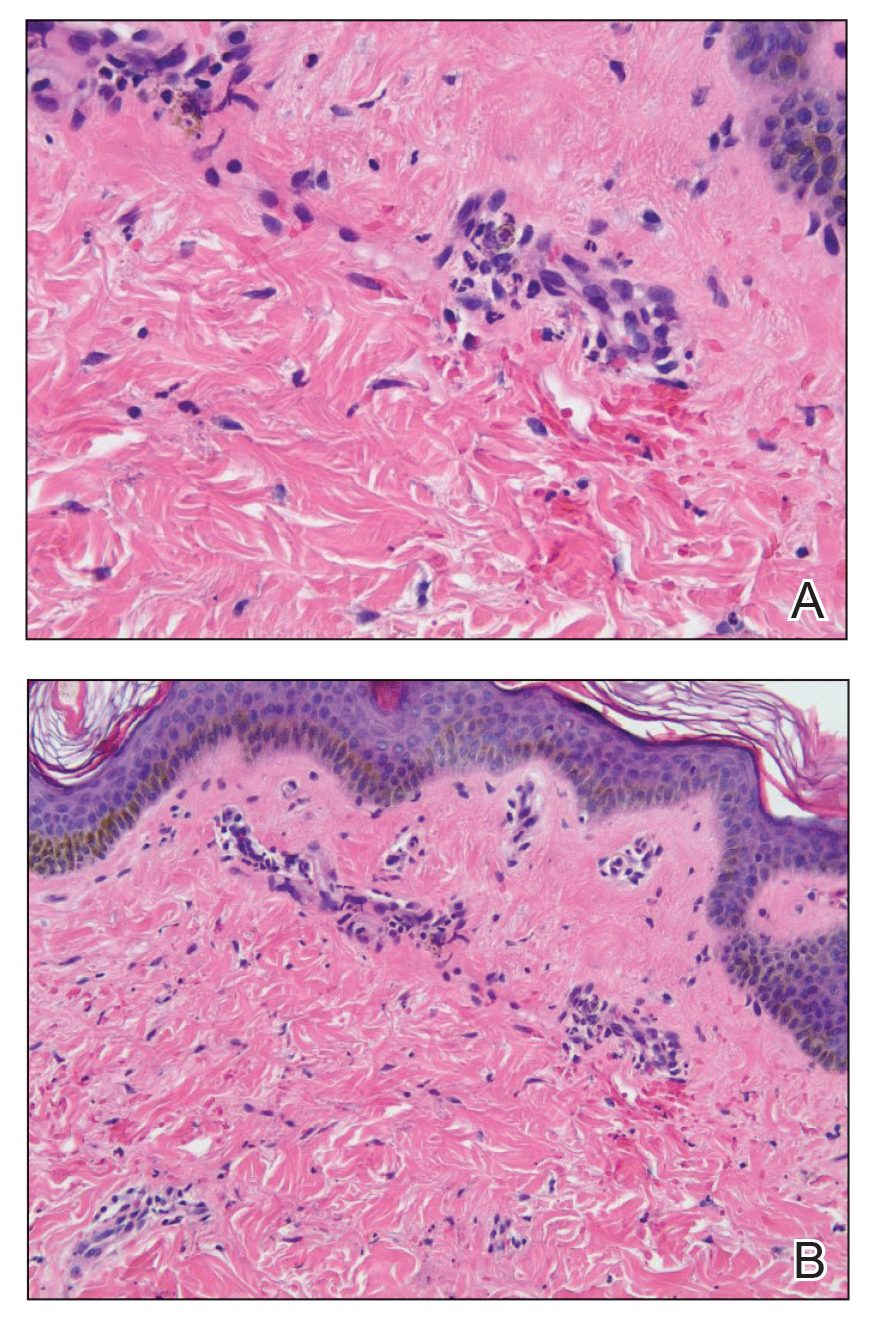

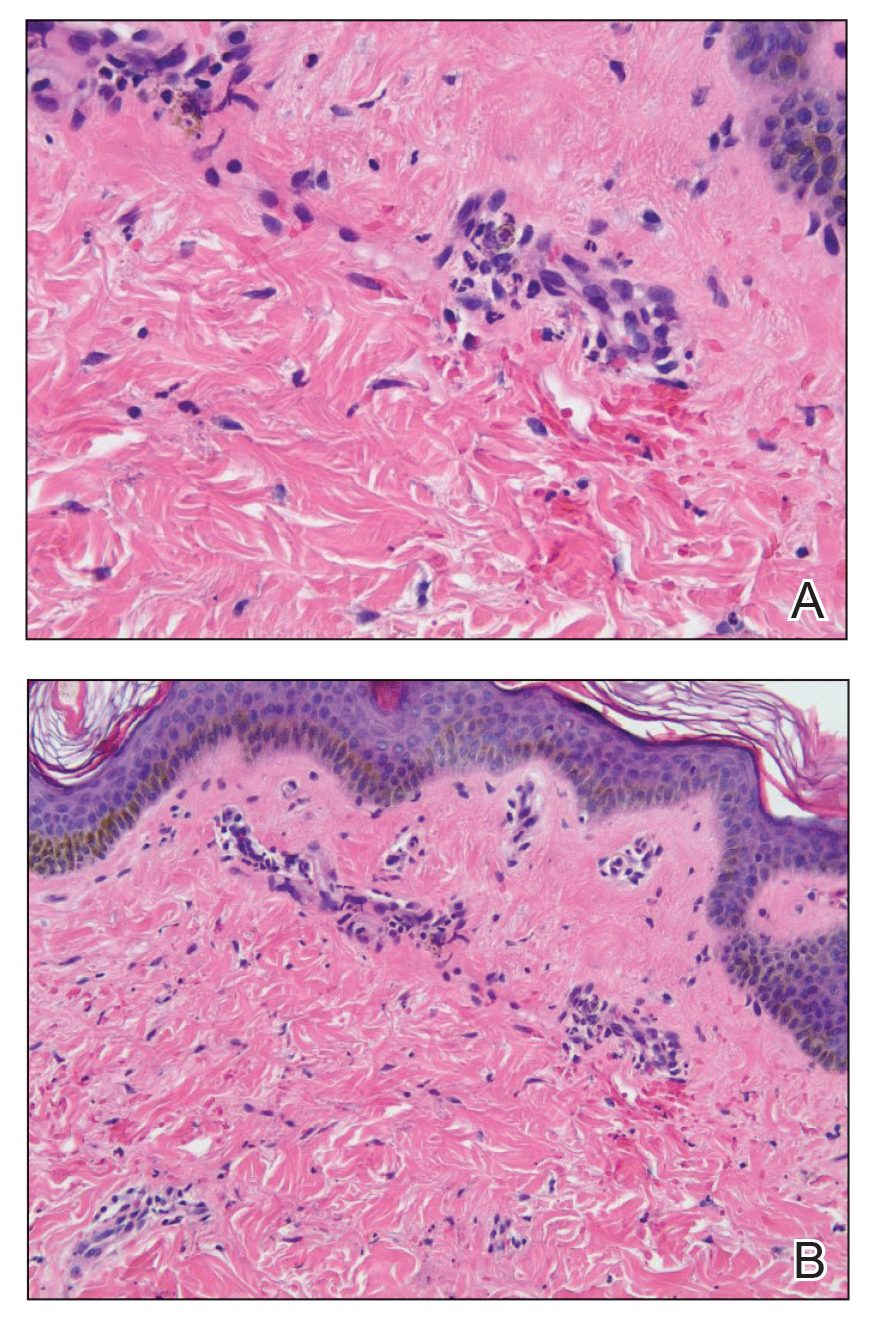

Punch biopsies were performed on lesional areas of the arm. Histopathology indicated a mild superficial perivascular dermal mixed infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing was negative for vasculitis. Immunohistochemical stains for CD117 and tryptase demonstrated a slight increase in the number of dermal mast cells; however, the increase was not sufficient to diagnose cutaneous mastocytosis, which was in the differential. We proposed a diagnosis of psychogenic purpura (PP)(also known as Gardner-Diamond syndrome). She was treated with gabapentin, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and cognitive therapy. Unfortunately, after starting therapy the patient was lost to follow-up.

Psychogenic purpura is a rare vasculopathy of unknown etiology that may be a special form of factitious disorder.1,2 In one study, PP occurred predominantly in females aged 15 to 66 years, with a median onset age of 33 years.3 A prodrome of localized itching, burning, and/or pain precedes the development of edematous plaques. The plaques evolve into painful ecchymoses within 1 to 2 days and resolve in 10 days or fewer without treatment. Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities but may occur anywhere on the body. The most common associated finding is an underlying depressive disorder. Episodes may be accompanied by headache, dizziness, fatigue, fever, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, menstrual irregularities, myalgia, and urologic conditions.

In 1955, Gardner and Diamond4 described the first cases of PP in 4 female patients at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. The investigators were able to replicate the painful ecchymoses with intradermal injection of the patient’s own erythrocytes into the skin. They proposed that the underlying pathogenesis involved autosensitization to erythrocyte stroma.4 Since then, others have suggested that the pathogenesis may include autosensitization to erythrocyte phosphatidylserine, tonus dysregulation of venous capillaries, abnormal endothelial fibrin synthesis, and capillary wall instability.5-7

Histopathology typically reveals superficial and deep perivascular inflammation with extravasated erythrocytes. Direct immunofluorescence is negative for vasculitis.8 Diagnostics and laboratory findings for underlying systemic illness are negative or noncontributory. Cutaneous injection of 1 mL of the patient’s own washed erythrocytes may result in the formation of the characteristic painful plaques within 24 hours; however, this test is limited by lack of standardization and low sensitivity.3

Psychogenic purpura may share clinical features with cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, such as HSP or urticarial vasculitis. Some of the findings that our patient was experiencing, including purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, are associated with HSP. However, HSP typically is self-limiting and classically features palpable purpura distributed across the lower extremities and buttocks. Histopathology demonstrates the classic findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; DIF typically is positive for perivascular IgA and C3 deposition. Increased serum IgA may be present.9 Urticarial vasculitis appears as erythematous indurated wheals that favor a proximal extremity and truncal distribution. They characteristically last longer than 24 hours, are frequently associated with nonprodromal pain or burning, and resolve with hyperpigmentation. Arthralgia and gastrointestinal, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic symptoms may be present, especially in patients with low complement levels.10 Skin biopsy demonstrates leukocytoclasia that must be accompanied by vessel wall necrosis. Fibrinoid deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, or perivascular inflammation may be present. In 70% of cases revealing perivascular immunoglobulin, C3, and fibrinogen deposition, DIF is positive. Serum C1q autoantibody may be associated with the hypocomplementemic form.10

The classic histopathologic findings in leukocytoclastic vasculitis include transmural neutrophilic infiltration of the walls of small vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, leukocytoclasia, extravasated erythrocytes, and signs of endothelial cell damage.9 A prior punch biopsy in this patient demonstrated rare neutrophilic nuclear debris within the vessel walls without fibrin deposition. Although the presence of nuclear debris and extravasated erythrocytes could be compatible with a manifestation of urticarial vasculitis, the lack of direct evidence of vessel wall necrosis combined with subsequent biopsies unequivocally ruled out cutaneous small vessel vasculitis in our patient.

Psychogenic purpura has been reported to occur frequently in the background of psycho-emotional distress. In 1989, Ratnoff11 noted that many of the patients he was treating at the University Hospitals of Cleveland, Ohio, had a depressive syndrome. A review of patients treated at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, illustrated concomitant psychiatric illnesses in 41 of 76 (54%) patients treated for PP, most commonly depressive, personality, and anxiety disorders.3

There is no consensus on therapy for PP. Treatment is based on providing symptomatic relief and relieving underlying psychiatric distress. Block et al12 found the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and psychotherapy to be successful in improving symptoms and reducing lesions at follow-up visits.

- Piette WW. Purpura: mechanisms and differential diagnosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:376-389.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Factitious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372.

- Sridharan M, Ali U, Hook CC, et al. The Mayo Clinic experience with psychogenic purpura (Gardner-Diamond syndrome). Am J Med Sci. 2019;357:411‐420.

- Gardner FH, Diamond LK. Autoerythrocyte sensitization; a form of purpura producing painful bruising following autosensitization to red blood cells in certain women. Blood. 1955;10:675-690.

- Groch GS, Finch SC, Rogoway W, et al. Studies in the pathogenesis of autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome. Blood. 1966;28:19-33.

- Strunecká A, Krpejsová L, Palecek J, et al. Transbilayer redistribution of phosphatidylserine in erythrocytes of a patient with autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (psychogenic purpura). Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch. 1990;117:829-841.

- Merlen JF. Ecchymotic patches of the fingers and Gardner-Diamond vascular purpura. Phlebologie. 1987;40:473-487.

- Ivanov OL, Lvov AN, Michenko AV, et al. Autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (Gardner-Diamond syndrome): review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:499-504.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Hamad A, Jithpratuck W, Krishnaswamy G. Urticarial vasculitis and associated disorders. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:394-398.

- Ratnoff OD. Psychogenic purpura (autoerythrocyte sensitization): an unsolved dilemma. Am J Med. 1989;87:16N-21N.

- Block ME, Sitenga JL, Lehrer M, et al. Gardner‐Diamond syndrome: a systematic review of treatment options for a rare psychodermatological disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:782-787.

To the Editor:

A 14-year-old Black adolescent girl presented with episodic, painful, edematous plaques that occurred symmetrically on the arms and legs of 5 years’ duration. The plaques evolved into hyperpigmented patches within 24 to 48 hours before eventually resolving. Fatigue, headache, arthralgias of the arms and legs, chest pain, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting variably accompanied these episodes.

Prior to visiting our clinic, the patient had been seen by numerous specialists. A review of her medical records revealed an initial diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), then urticarial vasculitis. She had been treated with antihistamines, topical and systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, dapsone, azathioprine, and gabapentin. All treatments were ineffectual. She underwent extensive diagnostic testing and imaging, which were normal or noncontributory, including type I allergy testing; multiple exhaustive batteries of hematologic testing; and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvic region. Biopsies from symptomatic segments of the gastrointestinal tract were normal.

Chronic treatment with systemic steroids over 9 months resulted in gastritis and an episode of hematemesis requiring emergent hospitalization. A lengthy multidisciplinary evaluation was conducted at the patient’s local community hospital; the team concluded that she had an urticarial-type rash with accompanying symptoms that did not have an autoimmune, rheumatologic, or inflammatory basis.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for recent-onset panic attacks. Her family medical history was noncontributory. Physical examination revealed multiple violaceous hyperpigmented patches diffusely located on the proximal upper arms (Figure 1). There were no additional findings on physical examination.

Punch biopsies were performed on lesional areas of the arm. Histopathology indicated a mild superficial perivascular dermal mixed infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing was negative for vasculitis. Immunohistochemical stains for CD117 and tryptase demonstrated a slight increase in the number of dermal mast cells; however, the increase was not sufficient to diagnose cutaneous mastocytosis, which was in the differential. We proposed a diagnosis of psychogenic purpura (PP)(also known as Gardner-Diamond syndrome). She was treated with gabapentin, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and cognitive therapy. Unfortunately, after starting therapy the patient was lost to follow-up.

Psychogenic purpura is a rare vasculopathy of unknown etiology that may be a special form of factitious disorder.1,2 In one study, PP occurred predominantly in females aged 15 to 66 years, with a median onset age of 33 years.3 A prodrome of localized itching, burning, and/or pain precedes the development of edematous plaques. The plaques evolve into painful ecchymoses within 1 to 2 days and resolve in 10 days or fewer without treatment. Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities but may occur anywhere on the body. The most common associated finding is an underlying depressive disorder. Episodes may be accompanied by headache, dizziness, fatigue, fever, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, menstrual irregularities, myalgia, and urologic conditions.

In 1955, Gardner and Diamond4 described the first cases of PP in 4 female patients at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. The investigators were able to replicate the painful ecchymoses with intradermal injection of the patient’s own erythrocytes into the skin. They proposed that the underlying pathogenesis involved autosensitization to erythrocyte stroma.4 Since then, others have suggested that the pathogenesis may include autosensitization to erythrocyte phosphatidylserine, tonus dysregulation of venous capillaries, abnormal endothelial fibrin synthesis, and capillary wall instability.5-7

Histopathology typically reveals superficial and deep perivascular inflammation with extravasated erythrocytes. Direct immunofluorescence is negative for vasculitis.8 Diagnostics and laboratory findings for underlying systemic illness are negative or noncontributory. Cutaneous injection of 1 mL of the patient’s own washed erythrocytes may result in the formation of the characteristic painful plaques within 24 hours; however, this test is limited by lack of standardization and low sensitivity.3

Psychogenic purpura may share clinical features with cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, such as HSP or urticarial vasculitis. Some of the findings that our patient was experiencing, including purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, are associated with HSP. However, HSP typically is self-limiting and classically features palpable purpura distributed across the lower extremities and buttocks. Histopathology demonstrates the classic findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; DIF typically is positive for perivascular IgA and C3 deposition. Increased serum IgA may be present.9 Urticarial vasculitis appears as erythematous indurated wheals that favor a proximal extremity and truncal distribution. They characteristically last longer than 24 hours, are frequently associated with nonprodromal pain or burning, and resolve with hyperpigmentation. Arthralgia and gastrointestinal, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic symptoms may be present, especially in patients with low complement levels.10 Skin biopsy demonstrates leukocytoclasia that must be accompanied by vessel wall necrosis. Fibrinoid deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, or perivascular inflammation may be present. In 70% of cases revealing perivascular immunoglobulin, C3, and fibrinogen deposition, DIF is positive. Serum C1q autoantibody may be associated with the hypocomplementemic form.10

The classic histopathologic findings in leukocytoclastic vasculitis include transmural neutrophilic infiltration of the walls of small vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, leukocytoclasia, extravasated erythrocytes, and signs of endothelial cell damage.9 A prior punch biopsy in this patient demonstrated rare neutrophilic nuclear debris within the vessel walls without fibrin deposition. Although the presence of nuclear debris and extravasated erythrocytes could be compatible with a manifestation of urticarial vasculitis, the lack of direct evidence of vessel wall necrosis combined with subsequent biopsies unequivocally ruled out cutaneous small vessel vasculitis in our patient.

Psychogenic purpura has been reported to occur frequently in the background of psycho-emotional distress. In 1989, Ratnoff11 noted that many of the patients he was treating at the University Hospitals of Cleveland, Ohio, had a depressive syndrome. A review of patients treated at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, illustrated concomitant psychiatric illnesses in 41 of 76 (54%) patients treated for PP, most commonly depressive, personality, and anxiety disorders.3

There is no consensus on therapy for PP. Treatment is based on providing symptomatic relief and relieving underlying psychiatric distress. Block et al12 found the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and psychotherapy to be successful in improving symptoms and reducing lesions at follow-up visits.

To the Editor:

A 14-year-old Black adolescent girl presented with episodic, painful, edematous plaques that occurred symmetrically on the arms and legs of 5 years’ duration. The plaques evolved into hyperpigmented patches within 24 to 48 hours before eventually resolving. Fatigue, headache, arthralgias of the arms and legs, chest pain, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting variably accompanied these episodes.

Prior to visiting our clinic, the patient had been seen by numerous specialists. A review of her medical records revealed an initial diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), then urticarial vasculitis. She had been treated with antihistamines, topical and systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, dapsone, azathioprine, and gabapentin. All treatments were ineffectual. She underwent extensive diagnostic testing and imaging, which were normal or noncontributory, including type I allergy testing; multiple exhaustive batteries of hematologic testing; and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvic region. Biopsies from symptomatic segments of the gastrointestinal tract were normal.

Chronic treatment with systemic steroids over 9 months resulted in gastritis and an episode of hematemesis requiring emergent hospitalization. A lengthy multidisciplinary evaluation was conducted at the patient’s local community hospital; the team concluded that she had an urticarial-type rash with accompanying symptoms that did not have an autoimmune, rheumatologic, or inflammatory basis.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for recent-onset panic attacks. Her family medical history was noncontributory. Physical examination revealed multiple violaceous hyperpigmented patches diffusely located on the proximal upper arms (Figure 1). There were no additional findings on physical examination.

Punch biopsies were performed on lesional areas of the arm. Histopathology indicated a mild superficial perivascular dermal mixed infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing was negative for vasculitis. Immunohistochemical stains for CD117 and tryptase demonstrated a slight increase in the number of dermal mast cells; however, the increase was not sufficient to diagnose cutaneous mastocytosis, which was in the differential. We proposed a diagnosis of psychogenic purpura (PP)(also known as Gardner-Diamond syndrome). She was treated with gabapentin, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and cognitive therapy. Unfortunately, after starting therapy the patient was lost to follow-up.

Psychogenic purpura is a rare vasculopathy of unknown etiology that may be a special form of factitious disorder.1,2 In one study, PP occurred predominantly in females aged 15 to 66 years, with a median onset age of 33 years.3 A prodrome of localized itching, burning, and/or pain precedes the development of edematous plaques. The plaques evolve into painful ecchymoses within 1 to 2 days and resolve in 10 days or fewer without treatment. Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities but may occur anywhere on the body. The most common associated finding is an underlying depressive disorder. Episodes may be accompanied by headache, dizziness, fatigue, fever, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, menstrual irregularities, myalgia, and urologic conditions.

In 1955, Gardner and Diamond4 described the first cases of PP in 4 female patients at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. The investigators were able to replicate the painful ecchymoses with intradermal injection of the patient’s own erythrocytes into the skin. They proposed that the underlying pathogenesis involved autosensitization to erythrocyte stroma.4 Since then, others have suggested that the pathogenesis may include autosensitization to erythrocyte phosphatidylserine, tonus dysregulation of venous capillaries, abnormal endothelial fibrin synthesis, and capillary wall instability.5-7

Histopathology typically reveals superficial and deep perivascular inflammation with extravasated erythrocytes. Direct immunofluorescence is negative for vasculitis.8 Diagnostics and laboratory findings for underlying systemic illness are negative or noncontributory. Cutaneous injection of 1 mL of the patient’s own washed erythrocytes may result in the formation of the characteristic painful plaques within 24 hours; however, this test is limited by lack of standardization and low sensitivity.3

Psychogenic purpura may share clinical features with cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, such as HSP or urticarial vasculitis. Some of the findings that our patient was experiencing, including purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, are associated with HSP. However, HSP typically is self-limiting and classically features palpable purpura distributed across the lower extremities and buttocks. Histopathology demonstrates the classic findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; DIF typically is positive for perivascular IgA and C3 deposition. Increased serum IgA may be present.9 Urticarial vasculitis appears as erythematous indurated wheals that favor a proximal extremity and truncal distribution. They characteristically last longer than 24 hours, are frequently associated with nonprodromal pain or burning, and resolve with hyperpigmentation. Arthralgia and gastrointestinal, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic symptoms may be present, especially in patients with low complement levels.10 Skin biopsy demonstrates leukocytoclasia that must be accompanied by vessel wall necrosis. Fibrinoid deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, or perivascular inflammation may be present. In 70% of cases revealing perivascular immunoglobulin, C3, and fibrinogen deposition, DIF is positive. Serum C1q autoantibody may be associated with the hypocomplementemic form.10

The classic histopathologic findings in leukocytoclastic vasculitis include transmural neutrophilic infiltration of the walls of small vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, leukocytoclasia, extravasated erythrocytes, and signs of endothelial cell damage.9 A prior punch biopsy in this patient demonstrated rare neutrophilic nuclear debris within the vessel walls without fibrin deposition. Although the presence of nuclear debris and extravasated erythrocytes could be compatible with a manifestation of urticarial vasculitis, the lack of direct evidence of vessel wall necrosis combined with subsequent biopsies unequivocally ruled out cutaneous small vessel vasculitis in our patient.

Psychogenic purpura has been reported to occur frequently in the background of psycho-emotional distress. In 1989, Ratnoff11 noted that many of the patients he was treating at the University Hospitals of Cleveland, Ohio, had a depressive syndrome. A review of patients treated at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, illustrated concomitant psychiatric illnesses in 41 of 76 (54%) patients treated for PP, most commonly depressive, personality, and anxiety disorders.3

There is no consensus on therapy for PP. Treatment is based on providing symptomatic relief and relieving underlying psychiatric distress. Block et al12 found the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and psychotherapy to be successful in improving symptoms and reducing lesions at follow-up visits.

- Piette WW. Purpura: mechanisms and differential diagnosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:376-389.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Factitious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372.

- Sridharan M, Ali U, Hook CC, et al. The Mayo Clinic experience with psychogenic purpura (Gardner-Diamond syndrome). Am J Med Sci. 2019;357:411‐420.

- Gardner FH, Diamond LK. Autoerythrocyte sensitization; a form of purpura producing painful bruising following autosensitization to red blood cells in certain women. Blood. 1955;10:675-690.

- Groch GS, Finch SC, Rogoway W, et al. Studies in the pathogenesis of autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome. Blood. 1966;28:19-33.

- Strunecká A, Krpejsová L, Palecek J, et al. Transbilayer redistribution of phosphatidylserine in erythrocytes of a patient with autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (psychogenic purpura). Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch. 1990;117:829-841.

- Merlen JF. Ecchymotic patches of the fingers and Gardner-Diamond vascular purpura. Phlebologie. 1987;40:473-487.

- Ivanov OL, Lvov AN, Michenko AV, et al. Autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (Gardner-Diamond syndrome): review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:499-504.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Hamad A, Jithpratuck W, Krishnaswamy G. Urticarial vasculitis and associated disorders. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:394-398.

- Ratnoff OD. Psychogenic purpura (autoerythrocyte sensitization): an unsolved dilemma. Am J Med. 1989;87:16N-21N.

- Block ME, Sitenga JL, Lehrer M, et al. Gardner‐Diamond syndrome: a systematic review of treatment options for a rare psychodermatological disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:782-787.

- Piette WW. Purpura: mechanisms and differential diagnosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:376-389.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Factitious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372.

- Sridharan M, Ali U, Hook CC, et al. The Mayo Clinic experience with psychogenic purpura (Gardner-Diamond syndrome). Am J Med Sci. 2019;357:411‐420.

- Gardner FH, Diamond LK. Autoerythrocyte sensitization; a form of purpura producing painful bruising following autosensitization to red blood cells in certain women. Blood. 1955;10:675-690.

- Groch GS, Finch SC, Rogoway W, et al. Studies in the pathogenesis of autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome. Blood. 1966;28:19-33.

- Strunecká A, Krpejsová L, Palecek J, et al. Transbilayer redistribution of phosphatidylserine in erythrocytes of a patient with autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (psychogenic purpura). Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch. 1990;117:829-841.

- Merlen JF. Ecchymotic patches of the fingers and Gardner-Diamond vascular purpura. Phlebologie. 1987;40:473-487.

- Ivanov OL, Lvov AN, Michenko AV, et al. Autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (Gardner-Diamond syndrome): review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:499-504.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Hamad A, Jithpratuck W, Krishnaswamy G. Urticarial vasculitis and associated disorders. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:394-398.

- Ratnoff OD. Psychogenic purpura (autoerythrocyte sensitization): an unsolved dilemma. Am J Med. 1989;87:16N-21N.

- Block ME, Sitenga JL, Lehrer M, et al. Gardner‐Diamond syndrome: a systematic review of treatment options for a rare psychodermatological disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:782-787.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Psychogenic purpura is a rare vasculopathy characterized by painful recurrent episodes of purpura. It is a diagnosis of exclusion that may manifest with signs similar to cutaneous small vessel vasculitis.

- Awareness of this condition could help prevent unnecessary diagnostics, medications, and adverse events.