User login

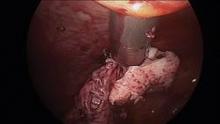

Intra-abdominal (intracorporeal) morcellation, especially electronically powered morcellation, has recently come under scrutiny. Generally performed at the time of conventional laparoscopic or robotic supracervical hysterectomy, total hysterectomy for the large uterus, or myomectomy, both power and cold-knife morcellation may splatter tissue fragments in the pelvis and abdomen, leading to potential parasitizing of the tissue and ectopic growth. Recent evidence indicates inadvertent morcellation of a leiomyosarcoma may negatively affect the patient’s subsequent disease-free survival and overall survival.

Concerns about morcellation heightened after Dr. Amy J. Reed, an anesthesiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and a mother of 6, underwent presumed fibroid surgery and was diagnosed, post morcellation, with leiomyosarcoma. Dr. Reed’s husband, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, where his wife’s surgery was performed, is calling for a moratorium on intra-abdominal morcellation, whether it involves the use of a power morcellator, or for that matter, the cold knife.

It is imperative and incumbent upon our specialty to have a detailed evaluation of the risks and benefits of morcellation. While morcellation of the rare leiomyosarcoma is a risk, banning intraabdominal/intrapelvic morcellation will certainly have a profound negative impact on patients who are able to undergo a minimally invasive gynecologic procedure. Banning morcellation would increase intraoperative risk and subsequent concern of postoperative pelvic adhesions and thus, potential impact on fertility (post myomectomy), dyspareunia, and pelvic pain. Further, a ban would incur higher costs and more loss of patient productivity (Hum. Reprod. 1998 13:2102-6). These concerns were the basis for the AAGL position statement touting a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

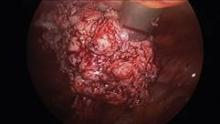

Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, electronically powered morcellators have been used to remove the uterus, fibroid(s), spleen, or kidney. Varying in size from 12-20 mm, electronic morcellators generally consist of a rotating circular blade at the end of a hollow tube. A tenaculum or multitoothed grasper is placed through the tube and blade to grasp the tissue to the revolving blade. The specimen is then removed in strips. Tissue splatter is inevitable, at least until the technique evolves to allow morcellation to be performed within the confines of a bag.

Benign uterine fibroids are the most common pelvic tumor in women. Literature reviews indicate the lifetime risk is 70% for white women and 80% in women of African ancestry. Uterine sarcomas occur in 3-7 women per 100,000 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-5). Further, Dr. Kimberly A. Kho of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Dr. Ceana H. Dr. Nezhat of Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, conducted a meta-analysis of 5,666 uterine procedures, and found 13 unsuspected uterine sarcomas, for a prevalence of 0.23% (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1093]).

This finding is consistent with that of a previous study by Dr. W.H. Parker who also noted a 0.23% risk, based on data from 1,332 women undergoing surgery secondary to uterine fibroids. Interestingly, in Dr. Parker’s study, the risk was 0.27% among women with rapidly growing leiomyoma, often thought to be a risk factor for sarcoma development (Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;83:414-8).

Because of the difficulty of making a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, it is doubtful that this risk will be decreased in the near future. Risk factors have not been well established, although a twofold higher incidence of leiomyosarcomas has been observed in black women (Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93:204-8). Increasing age would appear to increase uterine sarcoma risk, as the majority of cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen, when used for 5 or more years, appears to be associated with higher sarcoma rates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:2758-60) as is a history of pelvic irradiation or childhood retinoblastoma.

Unless metastatic disease is present, symptoms are similar for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. A rapidly growing mass, a finding associated with an increased risk of uterine sarcoma, was not seen in Parker’s study of 1,332 women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine leiomyoma. Similarly, size does not count; a large uterine mass or increased uterine size did not appear to be associated with a greater risk of sarcoma (Gynecol. Oncol. 2003;89:460-9).

Some contend that failed response with such therapies as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and uterine artery embolization are associated with increased incidence of leiomyosarcoma, but the data are not convincing (Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998;76:237-40).

Physical examination and imaging may be helpful in finding enlarged lymph nodes, but imaging methods have not been reliably shown to enable a preoperative diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma (Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188-98; AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:1369-74). Further, while some physicians point out that an ill-defined margin may increase leiomyosarcoma risk, this finding is certainly noted as well with benign adenomyomas.

Finally, data are scant in support of preoperative endometrial sampling to establish a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. In two studies comparing a total of 14 patients, 7 were correctly diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma prior to surgery (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;162:968-74; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;110:43-8).

With little differentiation in clinical presentation and the inability to distinguish leiomyoma from leiomyosarcoma based on imaging or sampling, it is not surprising that patients undergoing morcellation for an expected benign condition would subsequently be diagnosed with uterine leiomyosarcoma. With this in mind, it is important to review the current body of literature to further evaluate the risks and benefits of morcellation, and what place minimally invasive gynecologic surgery will have for the treatment of uterine masses.

Tumor morcellation of unrecognized leiomyosarcomas was significantly associated with poorer disease free survival (odds ratio, 2.59, P = 1.43), higher stage (I vs. II; [OR, 19.12, P = .037]) and poorer overall survival (OR, 3.07, P =.040) in a 2011 study. Park et al. assessed 56 consecutive patients, 25 with morcellation and 31 without tumor morcellation, who had stage I and stage II uterine leiomyosarcomas and were treated between 1989 and 2010. The percentage of patients with dissemination also was noted to be greater in patients with tumor morcellation (44% vs. 12.9%, P =.032). Interestingly, ovarian tissue was more frequently preserved in the morcellation group (38.7% vs. 72%, P =.013) (Gynecol. Oncol. 2011;122:255-9)

In response to a subsequent Letter to the Editor about these risks, the study’s author put the findings in perspective. "The frequency of incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma in patients who undergo surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma is extremely rare. At our medical center, only 49 of 22,825 patients (0.21%) who underwent surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma had incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma. Therefore, we believe that surgeons need not avoid non-laparotomic* surgical routes because of the rare possibility of an incidental diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, even when tumor morcellation is required" (Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;124:172-3).

Additionally, a retrospective study from Brigham & Women’s Hospital found that disease was often already disseminated before morcellation procedures. In 21 patients with a median age of 46 years and no documented evidence of extrauterine disease, 15 had uterine leiomyosarcomas and 6 had smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential that were inadvertently morcellated; data was incorporated from January 2005 to January 2012. While most patients underwent power morcellation with laparoscopy, two underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation, and one patient had a vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation.

Immediate surgical reexploration was performed for staging in 12 patients. Significant findings of disseminated intraperitoneal disease were detected in two of seven patients with presumed stage I uterine leiomyosarcoma and in one of four patients with presumed stage I smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential. Moreover, of the eight patients who did not have disseminated disease at the time of the staging procedure, one subsequently had a recurrence. The remaining patients had no recurrences and remain disease free.

One patient was already FIGO stage IV at the original surgery, two more patients were upstaged at the original surgery and underwent re-exploration at 18 and 20 months respectively (certainly, a long period prior to second look). Moreover, the authors note various reasons why a significant number of patients were upstaged; including incorrect staging after initial surgery, progression of disease during the time interval, or secondary to direct seeding of morcellated tumor fragments. Five of the 15 leiomyosarcoma patients were deceased at the time of the publication. The authors also point out that their study is limited by the fact that it is retrospective, and access to information regarding care received from non-affiliated institutions is limited (Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132:360-5).

In summary, morcellation of an unsuspected uterine sarcoma, whether using an electrically powered morcellator at the time of laparoscopy or cold knife at time of vaginal surgery, appears to have a negative impact; however, the studies to date are merely retrospective case studies. By no means do they provide the evidence required to place a moratorium on morcellation.

Further, if such a ban is imposed, would it then not be equally justifiable to pose similar regulations on use of oral contraceptives for symptom relief, endometrial ablation when fibroids are involved, or for that matter, uterine artery embolization? All these potential treatment regimens delay diagnosis and treatment and leave the potential uterine sarcoma in situ.

In the end, while the disease-free survival as well as overall survival appears to be hindered by dissemination of leiomyosarcoma at time of both electronic and cold-knife morcellation, the diagnosis is fortunately rare. A moratorium on the technique, however, would increase the number of concomitant laparotomies that would be required, and along with it, the increased inherent risk as well as prolonged recovery. At the present time, without better diagnostic tools or safer morcellation techniques, it is imperative to have an open dialogue of the risks and benefits of morcellation and minimally invasive surgery with patients presenting with anticipated fibroids. Additionally, our industry partners must be empowered to create safer morcellation techniques. This would appear to be morcellation within a bag.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller said he is a consultant for Ethicon, which manufactures a morcellator.

*Correction, 3/19/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the type of surgical route.

Intra-abdominal (intracorporeal) morcellation, especially electronically powered morcellation, has recently come under scrutiny. Generally performed at the time of conventional laparoscopic or robotic supracervical hysterectomy, total hysterectomy for the large uterus, or myomectomy, both power and cold-knife morcellation may splatter tissue fragments in the pelvis and abdomen, leading to potential parasitizing of the tissue and ectopic growth. Recent evidence indicates inadvertent morcellation of a leiomyosarcoma may negatively affect the patient’s subsequent disease-free survival and overall survival.

Concerns about morcellation heightened after Dr. Amy J. Reed, an anesthesiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and a mother of 6, underwent presumed fibroid surgery and was diagnosed, post morcellation, with leiomyosarcoma. Dr. Reed’s husband, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, where his wife’s surgery was performed, is calling for a moratorium on intra-abdominal morcellation, whether it involves the use of a power morcellator, or for that matter, the cold knife.

It is imperative and incumbent upon our specialty to have a detailed evaluation of the risks and benefits of morcellation. While morcellation of the rare leiomyosarcoma is a risk, banning intraabdominal/intrapelvic morcellation will certainly have a profound negative impact on patients who are able to undergo a minimally invasive gynecologic procedure. Banning morcellation would increase intraoperative risk and subsequent concern of postoperative pelvic adhesions and thus, potential impact on fertility (post myomectomy), dyspareunia, and pelvic pain. Further, a ban would incur higher costs and more loss of patient productivity (Hum. Reprod. 1998 13:2102-6). These concerns were the basis for the AAGL position statement touting a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, electronically powered morcellators have been used to remove the uterus, fibroid(s), spleen, or kidney. Varying in size from 12-20 mm, electronic morcellators generally consist of a rotating circular blade at the end of a hollow tube. A tenaculum or multitoothed grasper is placed through the tube and blade to grasp the tissue to the revolving blade. The specimen is then removed in strips. Tissue splatter is inevitable, at least until the technique evolves to allow morcellation to be performed within the confines of a bag.

Benign uterine fibroids are the most common pelvic tumor in women. Literature reviews indicate the lifetime risk is 70% for white women and 80% in women of African ancestry. Uterine sarcomas occur in 3-7 women per 100,000 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-5). Further, Dr. Kimberly A. Kho of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Dr. Ceana H. Dr. Nezhat of Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, conducted a meta-analysis of 5,666 uterine procedures, and found 13 unsuspected uterine sarcomas, for a prevalence of 0.23% (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1093]).

This finding is consistent with that of a previous study by Dr. W.H. Parker who also noted a 0.23% risk, based on data from 1,332 women undergoing surgery secondary to uterine fibroids. Interestingly, in Dr. Parker’s study, the risk was 0.27% among women with rapidly growing leiomyoma, often thought to be a risk factor for sarcoma development (Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;83:414-8).

Because of the difficulty of making a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, it is doubtful that this risk will be decreased in the near future. Risk factors have not been well established, although a twofold higher incidence of leiomyosarcomas has been observed in black women (Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93:204-8). Increasing age would appear to increase uterine sarcoma risk, as the majority of cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen, when used for 5 or more years, appears to be associated with higher sarcoma rates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:2758-60) as is a history of pelvic irradiation or childhood retinoblastoma.

Unless metastatic disease is present, symptoms are similar for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. A rapidly growing mass, a finding associated with an increased risk of uterine sarcoma, was not seen in Parker’s study of 1,332 women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine leiomyoma. Similarly, size does not count; a large uterine mass or increased uterine size did not appear to be associated with a greater risk of sarcoma (Gynecol. Oncol. 2003;89:460-9).

Some contend that failed response with such therapies as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and uterine artery embolization are associated with increased incidence of leiomyosarcoma, but the data are not convincing (Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998;76:237-40).

Physical examination and imaging may be helpful in finding enlarged lymph nodes, but imaging methods have not been reliably shown to enable a preoperative diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma (Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188-98; AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:1369-74). Further, while some physicians point out that an ill-defined margin may increase leiomyosarcoma risk, this finding is certainly noted as well with benign adenomyomas.

Finally, data are scant in support of preoperative endometrial sampling to establish a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. In two studies comparing a total of 14 patients, 7 were correctly diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma prior to surgery (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;162:968-74; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;110:43-8).

With little differentiation in clinical presentation and the inability to distinguish leiomyoma from leiomyosarcoma based on imaging or sampling, it is not surprising that patients undergoing morcellation for an expected benign condition would subsequently be diagnosed with uterine leiomyosarcoma. With this in mind, it is important to review the current body of literature to further evaluate the risks and benefits of morcellation, and what place minimally invasive gynecologic surgery will have for the treatment of uterine masses.

Tumor morcellation of unrecognized leiomyosarcomas was significantly associated with poorer disease free survival (odds ratio, 2.59, P = 1.43), higher stage (I vs. II; [OR, 19.12, P = .037]) and poorer overall survival (OR, 3.07, P =.040) in a 2011 study. Park et al. assessed 56 consecutive patients, 25 with morcellation and 31 without tumor morcellation, who had stage I and stage II uterine leiomyosarcomas and were treated between 1989 and 2010. The percentage of patients with dissemination also was noted to be greater in patients with tumor morcellation (44% vs. 12.9%, P =.032). Interestingly, ovarian tissue was more frequently preserved in the morcellation group (38.7% vs. 72%, P =.013) (Gynecol. Oncol. 2011;122:255-9)

In response to a subsequent Letter to the Editor about these risks, the study’s author put the findings in perspective. "The frequency of incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma in patients who undergo surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma is extremely rare. At our medical center, only 49 of 22,825 patients (0.21%) who underwent surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma had incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma. Therefore, we believe that surgeons need not avoid non-laparotomic* surgical routes because of the rare possibility of an incidental diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, even when tumor morcellation is required" (Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;124:172-3).

Additionally, a retrospective study from Brigham & Women’s Hospital found that disease was often already disseminated before morcellation procedures. In 21 patients with a median age of 46 years and no documented evidence of extrauterine disease, 15 had uterine leiomyosarcomas and 6 had smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential that were inadvertently morcellated; data was incorporated from January 2005 to January 2012. While most patients underwent power morcellation with laparoscopy, two underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation, and one patient had a vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation.

Immediate surgical reexploration was performed for staging in 12 patients. Significant findings of disseminated intraperitoneal disease were detected in two of seven patients with presumed stage I uterine leiomyosarcoma and in one of four patients with presumed stage I smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential. Moreover, of the eight patients who did not have disseminated disease at the time of the staging procedure, one subsequently had a recurrence. The remaining patients had no recurrences and remain disease free.

One patient was already FIGO stage IV at the original surgery, two more patients were upstaged at the original surgery and underwent re-exploration at 18 and 20 months respectively (certainly, a long period prior to second look). Moreover, the authors note various reasons why a significant number of patients were upstaged; including incorrect staging after initial surgery, progression of disease during the time interval, or secondary to direct seeding of morcellated tumor fragments. Five of the 15 leiomyosarcoma patients were deceased at the time of the publication. The authors also point out that their study is limited by the fact that it is retrospective, and access to information regarding care received from non-affiliated institutions is limited (Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132:360-5).

In summary, morcellation of an unsuspected uterine sarcoma, whether using an electrically powered morcellator at the time of laparoscopy or cold knife at time of vaginal surgery, appears to have a negative impact; however, the studies to date are merely retrospective case studies. By no means do they provide the evidence required to place a moratorium on morcellation.

Further, if such a ban is imposed, would it then not be equally justifiable to pose similar regulations on use of oral contraceptives for symptom relief, endometrial ablation when fibroids are involved, or for that matter, uterine artery embolization? All these potential treatment regimens delay diagnosis and treatment and leave the potential uterine sarcoma in situ.

In the end, while the disease-free survival as well as overall survival appears to be hindered by dissemination of leiomyosarcoma at time of both electronic and cold-knife morcellation, the diagnosis is fortunately rare. A moratorium on the technique, however, would increase the number of concomitant laparotomies that would be required, and along with it, the increased inherent risk as well as prolonged recovery. At the present time, without better diagnostic tools or safer morcellation techniques, it is imperative to have an open dialogue of the risks and benefits of morcellation and minimally invasive surgery with patients presenting with anticipated fibroids. Additionally, our industry partners must be empowered to create safer morcellation techniques. This would appear to be morcellation within a bag.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller said he is a consultant for Ethicon, which manufactures a morcellator.

*Correction, 3/19/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the type of surgical route.

Intra-abdominal (intracorporeal) morcellation, especially electronically powered morcellation, has recently come under scrutiny. Generally performed at the time of conventional laparoscopic or robotic supracervical hysterectomy, total hysterectomy for the large uterus, or myomectomy, both power and cold-knife morcellation may splatter tissue fragments in the pelvis and abdomen, leading to potential parasitizing of the tissue and ectopic growth. Recent evidence indicates inadvertent morcellation of a leiomyosarcoma may negatively affect the patient’s subsequent disease-free survival and overall survival.

Concerns about morcellation heightened after Dr. Amy J. Reed, an anesthesiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and a mother of 6, underwent presumed fibroid surgery and was diagnosed, post morcellation, with leiomyosarcoma. Dr. Reed’s husband, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, where his wife’s surgery was performed, is calling for a moratorium on intra-abdominal morcellation, whether it involves the use of a power morcellator, or for that matter, the cold knife.

It is imperative and incumbent upon our specialty to have a detailed evaluation of the risks and benefits of morcellation. While morcellation of the rare leiomyosarcoma is a risk, banning intraabdominal/intrapelvic morcellation will certainly have a profound negative impact on patients who are able to undergo a minimally invasive gynecologic procedure. Banning morcellation would increase intraoperative risk and subsequent concern of postoperative pelvic adhesions and thus, potential impact on fertility (post myomectomy), dyspareunia, and pelvic pain. Further, a ban would incur higher costs and more loss of patient productivity (Hum. Reprod. 1998 13:2102-6). These concerns were the basis for the AAGL position statement touting a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, electronically powered morcellators have been used to remove the uterus, fibroid(s), spleen, or kidney. Varying in size from 12-20 mm, electronic morcellators generally consist of a rotating circular blade at the end of a hollow tube. A tenaculum or multitoothed grasper is placed through the tube and blade to grasp the tissue to the revolving blade. The specimen is then removed in strips. Tissue splatter is inevitable, at least until the technique evolves to allow morcellation to be performed within the confines of a bag.

Benign uterine fibroids are the most common pelvic tumor in women. Literature reviews indicate the lifetime risk is 70% for white women and 80% in women of African ancestry. Uterine sarcomas occur in 3-7 women per 100,000 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-5). Further, Dr. Kimberly A. Kho of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Dr. Ceana H. Dr. Nezhat of Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, conducted a meta-analysis of 5,666 uterine procedures, and found 13 unsuspected uterine sarcomas, for a prevalence of 0.23% (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1093]).

This finding is consistent with that of a previous study by Dr. W.H. Parker who also noted a 0.23% risk, based on data from 1,332 women undergoing surgery secondary to uterine fibroids. Interestingly, in Dr. Parker’s study, the risk was 0.27% among women with rapidly growing leiomyoma, often thought to be a risk factor for sarcoma development (Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;83:414-8).

Because of the difficulty of making a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, it is doubtful that this risk will be decreased in the near future. Risk factors have not been well established, although a twofold higher incidence of leiomyosarcomas has been observed in black women (Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93:204-8). Increasing age would appear to increase uterine sarcoma risk, as the majority of cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen, when used for 5 or more years, appears to be associated with higher sarcoma rates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:2758-60) as is a history of pelvic irradiation or childhood retinoblastoma.

Unless metastatic disease is present, symptoms are similar for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. A rapidly growing mass, a finding associated with an increased risk of uterine sarcoma, was not seen in Parker’s study of 1,332 women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine leiomyoma. Similarly, size does not count; a large uterine mass or increased uterine size did not appear to be associated with a greater risk of sarcoma (Gynecol. Oncol. 2003;89:460-9).

Some contend that failed response with such therapies as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and uterine artery embolization are associated with increased incidence of leiomyosarcoma, but the data are not convincing (Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998;76:237-40).

Physical examination and imaging may be helpful in finding enlarged lymph nodes, but imaging methods have not been reliably shown to enable a preoperative diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma (Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188-98; AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:1369-74). Further, while some physicians point out that an ill-defined margin may increase leiomyosarcoma risk, this finding is certainly noted as well with benign adenomyomas.

Finally, data are scant in support of preoperative endometrial sampling to establish a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. In two studies comparing a total of 14 patients, 7 were correctly diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma prior to surgery (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;162:968-74; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;110:43-8).

With little differentiation in clinical presentation and the inability to distinguish leiomyoma from leiomyosarcoma based on imaging or sampling, it is not surprising that patients undergoing morcellation for an expected benign condition would subsequently be diagnosed with uterine leiomyosarcoma. With this in mind, it is important to review the current body of literature to further evaluate the risks and benefits of morcellation, and what place minimally invasive gynecologic surgery will have for the treatment of uterine masses.

Tumor morcellation of unrecognized leiomyosarcomas was significantly associated with poorer disease free survival (odds ratio, 2.59, P = 1.43), higher stage (I vs. II; [OR, 19.12, P = .037]) and poorer overall survival (OR, 3.07, P =.040) in a 2011 study. Park et al. assessed 56 consecutive patients, 25 with morcellation and 31 without tumor morcellation, who had stage I and stage II uterine leiomyosarcomas and were treated between 1989 and 2010. The percentage of patients with dissemination also was noted to be greater in patients with tumor morcellation (44% vs. 12.9%, P =.032). Interestingly, ovarian tissue was more frequently preserved in the morcellation group (38.7% vs. 72%, P =.013) (Gynecol. Oncol. 2011;122:255-9)

In response to a subsequent Letter to the Editor about these risks, the study’s author put the findings in perspective. "The frequency of incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma in patients who undergo surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma is extremely rare. At our medical center, only 49 of 22,825 patients (0.21%) who underwent surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma had incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma. Therefore, we believe that surgeons need not avoid non-laparotomic* surgical routes because of the rare possibility of an incidental diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, even when tumor morcellation is required" (Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;124:172-3).

Additionally, a retrospective study from Brigham & Women’s Hospital found that disease was often already disseminated before morcellation procedures. In 21 patients with a median age of 46 years and no documented evidence of extrauterine disease, 15 had uterine leiomyosarcomas and 6 had smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential that were inadvertently morcellated; data was incorporated from January 2005 to January 2012. While most patients underwent power morcellation with laparoscopy, two underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation, and one patient had a vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation.

Immediate surgical reexploration was performed for staging in 12 patients. Significant findings of disseminated intraperitoneal disease were detected in two of seven patients with presumed stage I uterine leiomyosarcoma and in one of four patients with presumed stage I smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential. Moreover, of the eight patients who did not have disseminated disease at the time of the staging procedure, one subsequently had a recurrence. The remaining patients had no recurrences and remain disease free.

One patient was already FIGO stage IV at the original surgery, two more patients were upstaged at the original surgery and underwent re-exploration at 18 and 20 months respectively (certainly, a long period prior to second look). Moreover, the authors note various reasons why a significant number of patients were upstaged; including incorrect staging after initial surgery, progression of disease during the time interval, or secondary to direct seeding of morcellated tumor fragments. Five of the 15 leiomyosarcoma patients were deceased at the time of the publication. The authors also point out that their study is limited by the fact that it is retrospective, and access to information regarding care received from non-affiliated institutions is limited (Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132:360-5).

In summary, morcellation of an unsuspected uterine sarcoma, whether using an electrically powered morcellator at the time of laparoscopy or cold knife at time of vaginal surgery, appears to have a negative impact; however, the studies to date are merely retrospective case studies. By no means do they provide the evidence required to place a moratorium on morcellation.

Further, if such a ban is imposed, would it then not be equally justifiable to pose similar regulations on use of oral contraceptives for symptom relief, endometrial ablation when fibroids are involved, or for that matter, uterine artery embolization? All these potential treatment regimens delay diagnosis and treatment and leave the potential uterine sarcoma in situ.

In the end, while the disease-free survival as well as overall survival appears to be hindered by dissemination of leiomyosarcoma at time of both electronic and cold-knife morcellation, the diagnosis is fortunately rare. A moratorium on the technique, however, would increase the number of concomitant laparotomies that would be required, and along with it, the increased inherent risk as well as prolonged recovery. At the present time, without better diagnostic tools or safer morcellation techniques, it is imperative to have an open dialogue of the risks and benefits of morcellation and minimally invasive surgery with patients presenting with anticipated fibroids. Additionally, our industry partners must be empowered to create safer morcellation techniques. This would appear to be morcellation within a bag.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller said he is a consultant for Ethicon, which manufactures a morcellator.

*Correction, 3/19/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the type of surgical route.