User login

Safe abdominal laparoscopic entry

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

Laparoscopic approach to abdominal cerclage

Preterm birth remains a significant cause of infant morbidity and mortality. A well-established cause of preterm birth is cervical insufficiency, which occurs in approximately 1% of pregnancies and up to 8% of recurrent miscarriages and midtrimester pregnancy loss. A cerclage, a purse-string suture around the cervix, is placed to treat cervical insufficiency and, thus, prevent second-trimester loss and preterm birth. While, traditionally, placement of the cerclage was performed via a vaginal route, over the past 50 years, abdominal cerclage has been utilized in cases in which a vaginal cerclage has failed or the cervix is extremely short. The advantage of the abdominal approach is the ability to place the suture at the level of the internal os. Moreover, there is no potential risk of ascending infection and resultant preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes secondary to a foreign body in the vagina, as in the case of vaginal cerclage. There has been a reluctance to perform abdominal cerclage as a first-time treatment secondary to the need for cesarean section, risk of hemorrhage at the uterine vessels, and in the past, the need for a laparotomy.

With the introduction of a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach to abdominal cerclage in preterm birth prevention, there has been an upsurge in the popularity of abdominal cerclage as the first-line surgical procedure, especially after a failed vaginal cerclage. In 2018, Moawad et al., in a systematic review of laparoscopic abdominal cerclage, noted slight improvement in neonatal outcomes with laparoscopy vs. laparotomy.

For this edition of the Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Jon I. Einarsson, MD, PhD, MPH, who is chief of the division of minimally invasive gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics/gynecology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Einarsson is a past president of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. He is a very well-known, published clinical researcher and surgical innovator. Dr. Einarsson is the founder of Freyja Healthcare, a privately held medical device company advancing women’s health through innovation.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome my friend and colleague, Dr. Jon I. Einarsson, to this edition of the Master Class in gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Preterm birth remains a significant cause of infant morbidity and mortality. A well-established cause of preterm birth is cervical insufficiency, which occurs in approximately 1% of pregnancies and up to 8% of recurrent miscarriages and midtrimester pregnancy loss. A cerclage, a purse-string suture around the cervix, is placed to treat cervical insufficiency and, thus, prevent second-trimester loss and preterm birth. While, traditionally, placement of the cerclage was performed via a vaginal route, over the past 50 years, abdominal cerclage has been utilized in cases in which a vaginal cerclage has failed or the cervix is extremely short. The advantage of the abdominal approach is the ability to place the suture at the level of the internal os. Moreover, there is no potential risk of ascending infection and resultant preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes secondary to a foreign body in the vagina, as in the case of vaginal cerclage. There has been a reluctance to perform abdominal cerclage as a first-time treatment secondary to the need for cesarean section, risk of hemorrhage at the uterine vessels, and in the past, the need for a laparotomy.

With the introduction of a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach to abdominal cerclage in preterm birth prevention, there has been an upsurge in the popularity of abdominal cerclage as the first-line surgical procedure, especially after a failed vaginal cerclage. In 2018, Moawad et al., in a systematic review of laparoscopic abdominal cerclage, noted slight improvement in neonatal outcomes with laparoscopy vs. laparotomy.

For this edition of the Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Jon I. Einarsson, MD, PhD, MPH, who is chief of the division of minimally invasive gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics/gynecology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Einarsson is a past president of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. He is a very well-known, published clinical researcher and surgical innovator. Dr. Einarsson is the founder of Freyja Healthcare, a privately held medical device company advancing women’s health through innovation.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome my friend and colleague, Dr. Jon I. Einarsson, to this edition of the Master Class in gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Preterm birth remains a significant cause of infant morbidity and mortality. A well-established cause of preterm birth is cervical insufficiency, which occurs in approximately 1% of pregnancies and up to 8% of recurrent miscarriages and midtrimester pregnancy loss. A cerclage, a purse-string suture around the cervix, is placed to treat cervical insufficiency and, thus, prevent second-trimester loss and preterm birth. While, traditionally, placement of the cerclage was performed via a vaginal route, over the past 50 years, abdominal cerclage has been utilized in cases in which a vaginal cerclage has failed or the cervix is extremely short. The advantage of the abdominal approach is the ability to place the suture at the level of the internal os. Moreover, there is no potential risk of ascending infection and resultant preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes secondary to a foreign body in the vagina, as in the case of vaginal cerclage. There has been a reluctance to perform abdominal cerclage as a first-time treatment secondary to the need for cesarean section, risk of hemorrhage at the uterine vessels, and in the past, the need for a laparotomy.

With the introduction of a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach to abdominal cerclage in preterm birth prevention, there has been an upsurge in the popularity of abdominal cerclage as the first-line surgical procedure, especially after a failed vaginal cerclage. In 2018, Moawad et al., in a systematic review of laparoscopic abdominal cerclage, noted slight improvement in neonatal outcomes with laparoscopy vs. laparotomy.

For this edition of the Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Jon I. Einarsson, MD, PhD, MPH, who is chief of the division of minimally invasive gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics/gynecology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Einarsson is a past president of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. He is a very well-known, published clinical researcher and surgical innovator. Dr. Einarsson is the founder of Freyja Healthcare, a privately held medical device company advancing women’s health through innovation.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome my friend and colleague, Dr. Jon I. Einarsson, to this edition of the Master Class in gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Uterus transplantation for absolute uterine factor infertility

Until the advent of uterus transplantation, there was no restorative procedure available to a woman presenting with an absent uterus or nonfunctioning uterus; that is, absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI). It is estimated that 1 in 500 women of childbearing age are affected by AUFI.1,2 An absent uterus may be secondary to uterine agenesis or Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH), which occurs in 1 in 4,500 women.3,4 (Because women with MRKH have a normal karyotype, their children can be normal, without urogenital malformations.5)

Given the fact that roughly 240,000 hysterectomies are performed in the United States each year for women aged under 44 years, hysterectomy is the most common cause of acquired AUFI.6AUFI may also be secondary to a uterus that will not support a viable pregnancy; that is, a nonfunctional uterus. In this case, medical or surgical treatment is impossible to enable normal physiological uterine function to produce a successful pregnancy. Causal factors include Müllerian anomalies, severe intrauterine adhesions/Asherman syndrome, uterine fibroids not amendable to surgical therapy, and radiation injury not responsive to medical therapy.

Prior to uterus transplantation, parenthood could only be achieved via adoption, foster parenting, or gestational carrier. While utilizing a gestational carrier is legal in most U.S. states, most countries of western Europe as well as Brazil and Japan, to name a few, do not allow the use of gestational carriers. For some women, moreover, the desire is not only to have a baby, but to carry a child as well.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Rebecca Flyckt, MD, division chief of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and associate professor at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and Elliott G. Richards, MD, director of reproductive endocrinology and infertility research at the Cleveland Clinic, to discuss the current and future state of uterus transplantation.

Dr. Flyckt and Dr. Richards have both contributed to the uterus transplantation team at the Cleveland Clinic and are founding members of the U.S. Uterus Transplant Consortium. They are well published in the field of minimally invasive gynecology and reproductive endocrinology and infertility. It is truly a pleasure to welcome them both to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

References

1. Fertil Steril. 2014 May;101(5):1228-36.

2. Acta Biomater. 2014 Dec;10(12):5034-42.

3. Hum Reprod Update. Mar-Apr 2001;7(2):161-74.

4. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000 Oct;55(10):644-9.

5. Fertil Steril. 1997 Feb;67(2):387-9

6. Am J Public Health. 2003 Feb;93(2):307-12.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Until the advent of uterus transplantation, there was no restorative procedure available to a woman presenting with an absent uterus or nonfunctioning uterus; that is, absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI). It is estimated that 1 in 500 women of childbearing age are affected by AUFI.1,2 An absent uterus may be secondary to uterine agenesis or Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH), which occurs in 1 in 4,500 women.3,4 (Because women with MRKH have a normal karyotype, their children can be normal, without urogenital malformations.5)

Given the fact that roughly 240,000 hysterectomies are performed in the United States each year for women aged under 44 years, hysterectomy is the most common cause of acquired AUFI.6AUFI may also be secondary to a uterus that will not support a viable pregnancy; that is, a nonfunctional uterus. In this case, medical or surgical treatment is impossible to enable normal physiological uterine function to produce a successful pregnancy. Causal factors include Müllerian anomalies, severe intrauterine adhesions/Asherman syndrome, uterine fibroids not amendable to surgical therapy, and radiation injury not responsive to medical therapy.

Prior to uterus transplantation, parenthood could only be achieved via adoption, foster parenting, or gestational carrier. While utilizing a gestational carrier is legal in most U.S. states, most countries of western Europe as well as Brazil and Japan, to name a few, do not allow the use of gestational carriers. For some women, moreover, the desire is not only to have a baby, but to carry a child as well.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Rebecca Flyckt, MD, division chief of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and associate professor at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and Elliott G. Richards, MD, director of reproductive endocrinology and infertility research at the Cleveland Clinic, to discuss the current and future state of uterus transplantation.

Dr. Flyckt and Dr. Richards have both contributed to the uterus transplantation team at the Cleveland Clinic and are founding members of the U.S. Uterus Transplant Consortium. They are well published in the field of minimally invasive gynecology and reproductive endocrinology and infertility. It is truly a pleasure to welcome them both to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

References

1. Fertil Steril. 2014 May;101(5):1228-36.

2. Acta Biomater. 2014 Dec;10(12):5034-42.

3. Hum Reprod Update. Mar-Apr 2001;7(2):161-74.

4. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000 Oct;55(10):644-9.

5. Fertil Steril. 1997 Feb;67(2):387-9

6. Am J Public Health. 2003 Feb;93(2):307-12.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Until the advent of uterus transplantation, there was no restorative procedure available to a woman presenting with an absent uterus or nonfunctioning uterus; that is, absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI). It is estimated that 1 in 500 women of childbearing age are affected by AUFI.1,2 An absent uterus may be secondary to uterine agenesis or Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH), which occurs in 1 in 4,500 women.3,4 (Because women with MRKH have a normal karyotype, their children can be normal, without urogenital malformations.5)

Given the fact that roughly 240,000 hysterectomies are performed in the United States each year for women aged under 44 years, hysterectomy is the most common cause of acquired AUFI.6AUFI may also be secondary to a uterus that will not support a viable pregnancy; that is, a nonfunctional uterus. In this case, medical or surgical treatment is impossible to enable normal physiological uterine function to produce a successful pregnancy. Causal factors include Müllerian anomalies, severe intrauterine adhesions/Asherman syndrome, uterine fibroids not amendable to surgical therapy, and radiation injury not responsive to medical therapy.

Prior to uterus transplantation, parenthood could only be achieved via adoption, foster parenting, or gestational carrier. While utilizing a gestational carrier is legal in most U.S. states, most countries of western Europe as well as Brazil and Japan, to name a few, do not allow the use of gestational carriers. For some women, moreover, the desire is not only to have a baby, but to carry a child as well.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Rebecca Flyckt, MD, division chief of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and associate professor at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and Elliott G. Richards, MD, director of reproductive endocrinology and infertility research at the Cleveland Clinic, to discuss the current and future state of uterus transplantation.

Dr. Flyckt and Dr. Richards have both contributed to the uterus transplantation team at the Cleveland Clinic and are founding members of the U.S. Uterus Transplant Consortium. They are well published in the field of minimally invasive gynecology and reproductive endocrinology and infertility. It is truly a pleasure to welcome them both to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

References

1. Fertil Steril. 2014 May;101(5):1228-36.

2. Acta Biomater. 2014 Dec;10(12):5034-42.

3. Hum Reprod Update. Mar-Apr 2001;7(2):161-74.

4. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000 Oct;55(10):644-9.

5. Fertil Steril. 1997 Feb;67(2):387-9

6. Am J Public Health. 2003 Feb;93(2):307-12.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Adenomyosis: An update on imaging, medical, and surgical treatment

Adenomyosis is a benign disorder, present in 20%-35% of women and characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. The ectopic endometrial tissue appears to cause hypertrophy in the myometrium, resulting in an enlarged globular uterus.

Adenomyosis may present as diffuse or focal involvement within the uterus. When the focal lesion appears to be well defined, it is referred to as an adenomyoma. It is not encapsulated like a fibroid. There may be involvement of the junctional zone of the myometrium – the area between the subendometrial myometrium and the outer myometrium. While the pathogenesis of adenomyosis is unknown, two rigorous theories exist: endomyometrial invagination of the endometrium and de novo from Müllerian rests.

For this installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted Keith B. Isaacson, MD, to discuss the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and medical and surgical treatment of adenomyosis.

Dr. Isaacson is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and infertility at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, Mass., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He is currently in practice specializing in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and infertility at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, where he is the director of the AAGL Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery. Dr. Isaacson is a past president of both the AAGL and the Society of Reproductive Surgeons, as well as a published clinical researcher and surgical innovator.

It is a true honor to welcome Dr. Isaacson to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the Department of Clinical Sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant disclosures. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Adenomyosis is a benign disorder, present in 20%-35% of women and characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. The ectopic endometrial tissue appears to cause hypertrophy in the myometrium, resulting in an enlarged globular uterus.

Adenomyosis may present as diffuse or focal involvement within the uterus. When the focal lesion appears to be well defined, it is referred to as an adenomyoma. It is not encapsulated like a fibroid. There may be involvement of the junctional zone of the myometrium – the area between the subendometrial myometrium and the outer myometrium. While the pathogenesis of adenomyosis is unknown, two rigorous theories exist: endomyometrial invagination of the endometrium and de novo from Müllerian rests.

For this installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted Keith B. Isaacson, MD, to discuss the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and medical and surgical treatment of adenomyosis.

Dr. Isaacson is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and infertility at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, Mass., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He is currently in practice specializing in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and infertility at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, where he is the director of the AAGL Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery. Dr. Isaacson is a past president of both the AAGL and the Society of Reproductive Surgeons, as well as a published clinical researcher and surgical innovator.

It is a true honor to welcome Dr. Isaacson to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the Department of Clinical Sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant disclosures. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Adenomyosis is a benign disorder, present in 20%-35% of women and characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. The ectopic endometrial tissue appears to cause hypertrophy in the myometrium, resulting in an enlarged globular uterus.

Adenomyosis may present as diffuse or focal involvement within the uterus. When the focal lesion appears to be well defined, it is referred to as an adenomyoma. It is not encapsulated like a fibroid. There may be involvement of the junctional zone of the myometrium – the area between the subendometrial myometrium and the outer myometrium. While the pathogenesis of adenomyosis is unknown, two rigorous theories exist: endomyometrial invagination of the endometrium and de novo from Müllerian rests.

For this installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted Keith B. Isaacson, MD, to discuss the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and medical and surgical treatment of adenomyosis.

Dr. Isaacson is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and infertility at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, Mass., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He is currently in practice specializing in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and infertility at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, where he is the director of the AAGL Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery. Dr. Isaacson is a past president of both the AAGL and the Society of Reproductive Surgeons, as well as a published clinical researcher and surgical innovator.

It is a true honor to welcome Dr. Isaacson to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the Department of Clinical Sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant disclosures. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Identifying ovarian malignancy is not so easy

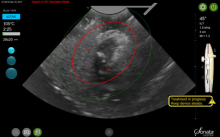

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

How to evaluate a suspicious ovarian mass

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Safely pushing the limits of MIGS surgery

In his excellent treatise on the history of hysterectomy, Chris Sutton, MBBch, noted that, while Themison of Athens in 50 bc and Soranus of Ephesus in 120 ad were reported to have performed vaginal hysterectomy, these cases essentially were emergency amputation of severely prolapsed uteri, which usually involved cutting both ureters and the bladder (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2010 Jul;17[4]:421–35). It was not until 1801 that the first planned elective vaginal hysterectomy was performed, and it was not until the mid 19th century, in 1853, that Walter Burnham, MD, in Lowell, Mass., performed the first abdominal hysterectomy resulting in patient survival.

Seemingly incredible, it was only 125 years later, in autumn of 1988 at William Nesbitt Memorial Hospital in Kingston, Pa., that Harry Reich, MD, performed the first total laparoscopically assisted hysterectomy.

Since Dr. Reich’s groundbreaking procedure, the performance of laparoscopic hysterectomy has advanced at a feverish pace. In my own practice, I have not performed an abdominal hysterectomy since 1998. My two partners, who are both fellowship-trained in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, MD, who joined my practice in 2007, and Kristen Sasaki, MD, who joined my practice in 2014, have never performed an open hysterectomy since starting practice. Despite these advances, One of the most difficult situations is the truly large uterus – greater than 2,500 grams.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Paya Pasic, MD, and Megan Cesta, MD, to discuss the next frontier: the removal of the multiple kilogram uterus.

Dr. Pasic is an internationally recognized leader in laparoscopic MIGS. He is professor of obstetrics, gynecology & women’s health; director, section of advanced gynecologic endoscopy, and codirector of the AAGL fellowship in MIGS at the University of Louisville (Ky.). Dr. Pasic is the current president of the International Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is also a past president of the AAGL (2009). Dr. Pasic is published in the field of MIGS, having authored many publications, book chapters, monographs, and textbooks.

Dr. Cesta is Dr. Pasic’s current fellow in MIGS and an instructor in obstetrics and gynecology at the university.

It is truly a pleasure to welcome Dr. Pasic and Dr. Cesta to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

In his excellent treatise on the history of hysterectomy, Chris Sutton, MBBch, noted that, while Themison of Athens in 50 bc and Soranus of Ephesus in 120 ad were reported to have performed vaginal hysterectomy, these cases essentially were emergency amputation of severely prolapsed uteri, which usually involved cutting both ureters and the bladder (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2010 Jul;17[4]:421–35). It was not until 1801 that the first planned elective vaginal hysterectomy was performed, and it was not until the mid 19th century, in 1853, that Walter Burnham, MD, in Lowell, Mass., performed the first abdominal hysterectomy resulting in patient survival.

Seemingly incredible, it was only 125 years later, in autumn of 1988 at William Nesbitt Memorial Hospital in Kingston, Pa., that Harry Reich, MD, performed the first total laparoscopically assisted hysterectomy.

Since Dr. Reich’s groundbreaking procedure, the performance of laparoscopic hysterectomy has advanced at a feverish pace. In my own practice, I have not performed an abdominal hysterectomy since 1998. My two partners, who are both fellowship-trained in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, MD, who joined my practice in 2007, and Kristen Sasaki, MD, who joined my practice in 2014, have never performed an open hysterectomy since starting practice. Despite these advances, One of the most difficult situations is the truly large uterus – greater than 2,500 grams.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Paya Pasic, MD, and Megan Cesta, MD, to discuss the next frontier: the removal of the multiple kilogram uterus.