User login

MD-IQ only

Does the Road to Treating Endometriosis Start in the Gut?

Researchers may be on track to develop a much-needed tool for studying endometriosis: A noninvasive stool test that could replace the current gold standard of laparoscopy.

Their approach, which focuses on the link between the gut microbiome and endometriosis, also identified a bacterial metabolite they said might be developed as an oral medication for the condition, which affects at least 11% of women.

In previous research, Rama Kommagani, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Pathology & Immunology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, worked with a mouse model in which endometrial tissue from donor rodents was injected into the peritoneal space of healthy rodents to induce the disorder.

Transfer of fecal microbiota from mice with endometriosis to those without the condition induced the trademark lesions, suggesting the microbiome influences the development of endometriosis. Treating the animals with the antibiotic metronidazole inhibited the progression of endometrial lesions.

Kommagani speculated the microbes release metabolites that stimulate the growth of the endometrial lesions. “Bad bacteria release metabolites, you know, which actually promote the disease,” Kommagani said. “But the good bacteria might release some protective metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids.”

In a new study, Kommagani and his colleagues sought to identify a unique profile of bacteria-derived metabolites that could reliably diagnose endometriosis. Using stool specimens from 18 women with the condition and 31 without the disease, his team conducted whole metabolic profiling of the gut microbiota.

After identifying hundreds of metabolites in the samples, further analysis revealed a subset of 12 metabolites that consistently differentiated women with and without endometriosis.

These findings led to more questions. “If a metabolite is lower in women with endometriosis, does it have any functional relevance?” Kommagani said.

One candidate was 4-hydroxyindole (4HI), which was found in lower levels in the stool of patients. This substance is a little-understood derivative of its parent compound, indole, which occurs naturally in plants and has a wide range of therapeutic uses.

Using a mouse model, Kommagani’s lab demonstrated that feeding mice 4HI before receiving an endometrial transplant prevented the development of lesions typical of endometriosis. Mice given 4HI after they had developed endometriosis showed regression of lesions and decreased response to painful stimuli.

“In a nutshell, we found a specific set of bacterial metabolites in stool, which could be used towards a noninvasive diagnostic test,” Kommagani said. “But we also found this distinct, specific metabolite that could be used as a therapeutic molecule.”

Tatnai Burnett, MD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who is not associated with the study, said a noninvasive test would have several advantages over the current methods of diagnosing endometriosis. Clinicians could detect and treat women earlier in the course of their disease. Secondly, a test with sufficient negative predictive value would be helpful in deciding whether to initiate treatment with hormones or other oral medications or go straight to surgery. “I would choose not to do a surgery if I knew with enough certainty that I wasn’t going to find anything,” said Burnett.

Lastly, a test that was quantitative and showed a response to treatment could be used as a disease activity marker to monitor the course of someone’s treatment.

But Burnett said more data on the approach are necessary. “This is a fairly small study, as it goes, for developing a screening test,” he said. “We need to see what its positive predictive value, negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity are in a bigger group.”

The road to a cure is even longer than the path to developing a screening test. Kommagani’s lab is now conducting more studies in mice to elucidate the pharmacokinetics and toxicology of 4HI before human trials can be attempted.

And as Burnett pointed out, although mouse models are great for experimentation and generating hypotheses, “We’ve seen way too many times in the past where something’s really exciting in a mouse model or a rat model or a monkey model, and it just doesn’t pan out in humans.”

Kommagani received funding from National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants (R01HD102680, R01HD104813) and a Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society. Burnett reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers may be on track to develop a much-needed tool for studying endometriosis: A noninvasive stool test that could replace the current gold standard of laparoscopy.

Their approach, which focuses on the link between the gut microbiome and endometriosis, also identified a bacterial metabolite they said might be developed as an oral medication for the condition, which affects at least 11% of women.

In previous research, Rama Kommagani, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Pathology & Immunology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, worked with a mouse model in which endometrial tissue from donor rodents was injected into the peritoneal space of healthy rodents to induce the disorder.

Transfer of fecal microbiota from mice with endometriosis to those without the condition induced the trademark lesions, suggesting the microbiome influences the development of endometriosis. Treating the animals with the antibiotic metronidazole inhibited the progression of endometrial lesions.

Kommagani speculated the microbes release metabolites that stimulate the growth of the endometrial lesions. “Bad bacteria release metabolites, you know, which actually promote the disease,” Kommagani said. “But the good bacteria might release some protective metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids.”

In a new study, Kommagani and his colleagues sought to identify a unique profile of bacteria-derived metabolites that could reliably diagnose endometriosis. Using stool specimens from 18 women with the condition and 31 without the disease, his team conducted whole metabolic profiling of the gut microbiota.

After identifying hundreds of metabolites in the samples, further analysis revealed a subset of 12 metabolites that consistently differentiated women with and without endometriosis.

These findings led to more questions. “If a metabolite is lower in women with endometriosis, does it have any functional relevance?” Kommagani said.

One candidate was 4-hydroxyindole (4HI), which was found in lower levels in the stool of patients. This substance is a little-understood derivative of its parent compound, indole, which occurs naturally in plants and has a wide range of therapeutic uses.

Using a mouse model, Kommagani’s lab demonstrated that feeding mice 4HI before receiving an endometrial transplant prevented the development of lesions typical of endometriosis. Mice given 4HI after they had developed endometriosis showed regression of lesions and decreased response to painful stimuli.

“In a nutshell, we found a specific set of bacterial metabolites in stool, which could be used towards a noninvasive diagnostic test,” Kommagani said. “But we also found this distinct, specific metabolite that could be used as a therapeutic molecule.”

Tatnai Burnett, MD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who is not associated with the study, said a noninvasive test would have several advantages over the current methods of diagnosing endometriosis. Clinicians could detect and treat women earlier in the course of their disease. Secondly, a test with sufficient negative predictive value would be helpful in deciding whether to initiate treatment with hormones or other oral medications or go straight to surgery. “I would choose not to do a surgery if I knew with enough certainty that I wasn’t going to find anything,” said Burnett.

Lastly, a test that was quantitative and showed a response to treatment could be used as a disease activity marker to monitor the course of someone’s treatment.

But Burnett said more data on the approach are necessary. “This is a fairly small study, as it goes, for developing a screening test,” he said. “We need to see what its positive predictive value, negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity are in a bigger group.”

The road to a cure is even longer than the path to developing a screening test. Kommagani’s lab is now conducting more studies in mice to elucidate the pharmacokinetics and toxicology of 4HI before human trials can be attempted.

And as Burnett pointed out, although mouse models are great for experimentation and generating hypotheses, “We’ve seen way too many times in the past where something’s really exciting in a mouse model or a rat model or a monkey model, and it just doesn’t pan out in humans.”

Kommagani received funding from National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants (R01HD102680, R01HD104813) and a Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society. Burnett reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers may be on track to develop a much-needed tool for studying endometriosis: A noninvasive stool test that could replace the current gold standard of laparoscopy.

Their approach, which focuses on the link between the gut microbiome and endometriosis, also identified a bacterial metabolite they said might be developed as an oral medication for the condition, which affects at least 11% of women.

In previous research, Rama Kommagani, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Pathology & Immunology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, worked with a mouse model in which endometrial tissue from donor rodents was injected into the peritoneal space of healthy rodents to induce the disorder.

Transfer of fecal microbiota from mice with endometriosis to those without the condition induced the trademark lesions, suggesting the microbiome influences the development of endometriosis. Treating the animals with the antibiotic metronidazole inhibited the progression of endometrial lesions.

Kommagani speculated the microbes release metabolites that stimulate the growth of the endometrial lesions. “Bad bacteria release metabolites, you know, which actually promote the disease,” Kommagani said. “But the good bacteria might release some protective metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids.”

In a new study, Kommagani and his colleagues sought to identify a unique profile of bacteria-derived metabolites that could reliably diagnose endometriosis. Using stool specimens from 18 women with the condition and 31 without the disease, his team conducted whole metabolic profiling of the gut microbiota.

After identifying hundreds of metabolites in the samples, further analysis revealed a subset of 12 metabolites that consistently differentiated women with and without endometriosis.

These findings led to more questions. “If a metabolite is lower in women with endometriosis, does it have any functional relevance?” Kommagani said.

One candidate was 4-hydroxyindole (4HI), which was found in lower levels in the stool of patients. This substance is a little-understood derivative of its parent compound, indole, which occurs naturally in plants and has a wide range of therapeutic uses.

Using a mouse model, Kommagani’s lab demonstrated that feeding mice 4HI before receiving an endometrial transplant prevented the development of lesions typical of endometriosis. Mice given 4HI after they had developed endometriosis showed regression of lesions and decreased response to painful stimuli.

“In a nutshell, we found a specific set of bacterial metabolites in stool, which could be used towards a noninvasive diagnostic test,” Kommagani said. “But we also found this distinct, specific metabolite that could be used as a therapeutic molecule.”

Tatnai Burnett, MD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who is not associated with the study, said a noninvasive test would have several advantages over the current methods of diagnosing endometriosis. Clinicians could detect and treat women earlier in the course of their disease. Secondly, a test with sufficient negative predictive value would be helpful in deciding whether to initiate treatment with hormones or other oral medications or go straight to surgery. “I would choose not to do a surgery if I knew with enough certainty that I wasn’t going to find anything,” said Burnett.

Lastly, a test that was quantitative and showed a response to treatment could be used as a disease activity marker to monitor the course of someone’s treatment.

But Burnett said more data on the approach are necessary. “This is a fairly small study, as it goes, for developing a screening test,” he said. “We need to see what its positive predictive value, negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity are in a bigger group.”

The road to a cure is even longer than the path to developing a screening test. Kommagani’s lab is now conducting more studies in mice to elucidate the pharmacokinetics and toxicology of 4HI before human trials can be attempted.

And as Burnett pointed out, although mouse models are great for experimentation and generating hypotheses, “We’ve seen way too many times in the past where something’s really exciting in a mouse model or a rat model or a monkey model, and it just doesn’t pan out in humans.”

Kommagani received funding from National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants (R01HD102680, R01HD104813) and a Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society. Burnett reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Endometriosis, Especially Severe Types, Boosts Ovarian Cancer Risk

Ovarian cancer risk was higher in women with endometriosis overall and markedly increased in those with severe forms, a large population-based cohort study found.

The findings, published in JAMA, suggest these women may benefit from counseling on ovarian cancer risk and prevention and potentially from targeted screening, according to a group led by Mollie E. Barnard, ScD, of the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

While the absolute increase in number of cases was small, endometriosis patients overall had a more than fourfold higher risk for any type of ovarian cancer. Those with more severe forms, such as ovarian endometriomas or deep infiltrating endometriosis, had a nearly 10-fold higher risk of any type of ovarian cancer. In addition, those with more severe endometriosis had a 19-fold higher risk of type 1 (slow-growing) ovarian cancer and almost three times the risk of the more aggressive type 2.

“Given the rarity of ovarian cancer, the excess risk was relatively small, with 10-20 additional cases per 10,000 women. Nevertheless, women with endometriosis, notably the more severe subtypes, may be an important population for targeted cancer screening and prevention studies,” said corresponding author Karen C. Schliep, PhD, MSPH, associate professor in the university’s Division of Public Health.

Prior studies have shown modest associations between endometriosis and ovarian cancer, Dr. Schliep said in an interview. A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis found endometriosis conferred nearly double the risk of ovarian cancer, although associations varied by ovarian cancer histotype. Few studies have been large enough to assess associations between endometriosis types — including superficial or peritoneal endometriosis vs ovarian endometriomas or deep infiltrating endometriosis and ovarian cancer histotypes such as low-grade serous, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous carcinomas (type 1), and the most aggressive and lethal form, high-grade serous type 2, she said in an interview. “Our large health administrative database of over 11 million individuals with linked electronic health and cancer registry data allowed us to answer this as yet poorly studied research question.”

Study Details

Drawing on Utah electronic health records from 1992 to 2019, the investigators matched 78,893 women with endometriosis in a 1:5 ratio to unaffected women. Cases were categorized as superficial endometriosis, ovarian endometriomas, deep infiltrating endometriosis, or other, and the types of endometriosis were matched to ovarian cancer histotypes.

The mean age of patients at first endometriosis diagnosis was 36 and the mean follow-up was 12 years. Compared with controls, endometriosis patients were more likely to be nulliparous (31% vs 24%) and to have had a hysterectomy (39% vs 6%) during follow-up.

There were 596 reported cases of ovarian cancer in the cohort. Those with incident endometriosis were 4.2 times more likely to develop ovarian cancer (95% CI, 3.59-4.91), 7.48 times more likely to develop type 1 ovarian cancer (95% CI, 5.80-9.65), and 2.70 times more likely to develop type 2 ovarian cancer (95% CI, 2.09-3.49) compared with those without endometriosis.

The magnitudes of these associations varied by endometriosis subtype. Individuals diagnosed with deep infiltrating endometriosis and/or ovarian endometriomas had 9.66 times the risk of ovarian cancer vs individuals without endometriosis (95% CI, 7.77-12.00). “Women with, compared to without, more severe endometriosis had a 19-fold higher risk of type 1 ovarian cancer, including endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous, and low-grade serous,” Dr. Schliep said, with associated risk highest for malignant subtypes such as clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma (adjusted hazard ratios, 11.15 and 7.96, respectively.

According to Dr. Schliep, physicians should encourage endometriosis patients to be aware of but not worry about ovarian cancer risk because the likelihood of developing it remains low. For their part, patients can reduce their risk of cancer through a balanced diet with low intake of alcohol, regular exercise, a healthy weight, and abstention from smoking.

Her message for researchers is as follows: “We need more studies that explore how different types of endometriosis impact different types of ovarian cancer risk. These studies will guide improved ovarian cancer screening and prevention strategies among women with severe endometriosis, with or without other important ovarian cancer risk factors such as BRCA 1/2 variations.”

An accompanying editorial called the Utah study “eloquent” and noted its distinguishing contribution of observing associations between subtypes of endometriosis with overall risk for ovarian cancer as well as histologic subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer.

Nevertheless, Michael T. McHale, MD, of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at Moores Cancer Center, UC San Diego Health, University of California, expressed some methodological concerns. Although the authors attempted to control for key confounders, he noted, the dataset could not provide details on the medical management of endometriosis, such as oral contraceptives or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. “Additionally, there is a possibility that women in the control cohort could have had undiagnosed endometriosis,” he wrote.

Furthermore, making clinical recommendations from these reported observations, particularly with respect to deep infiltrating endometriosis, would require a clear and consistent definition of this type in the dataset over the entire study interval from 1992 to 2019 and for the state of Utah, which the authors did not provide.

“Despite this potential challenge, the increased risk associated with deep infiltrating and/or ovarian endometriosis was clearly significant,” Dr. McHale wrote.

And although the absolute number of ovarian cancers is limited, in his view, the increased risk is sufficiently significant to advise women who have completed childbearing or have alternative fertility options to consider “more definitive surgery.”

This study was supported by multiple not-for-profit agencies, including the National Cancer Institute, the University of Utah, the National Center for Research Resources, the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, the Utah Cancer Registry, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Huntsman Cancer Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Doris Duke Foundation. Dr. Barnard reported grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Epi Excellence LLC outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported similar funding from nonprofit agencies or private research organizations. Dr Schliep disclosed no competing interests. Dr McHale reported educational consulting for Eisai Training outside the submitted work.

Ovarian cancer risk was higher in women with endometriosis overall and markedly increased in those with severe forms, a large population-based cohort study found.

The findings, published in JAMA, suggest these women may benefit from counseling on ovarian cancer risk and prevention and potentially from targeted screening, according to a group led by Mollie E. Barnard, ScD, of the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

While the absolute increase in number of cases was small, endometriosis patients overall had a more than fourfold higher risk for any type of ovarian cancer. Those with more severe forms, such as ovarian endometriomas or deep infiltrating endometriosis, had a nearly 10-fold higher risk of any type of ovarian cancer. In addition, those with more severe endometriosis had a 19-fold higher risk of type 1 (slow-growing) ovarian cancer and almost three times the risk of the more aggressive type 2.

“Given the rarity of ovarian cancer, the excess risk was relatively small, with 10-20 additional cases per 10,000 women. Nevertheless, women with endometriosis, notably the more severe subtypes, may be an important population for targeted cancer screening and prevention studies,” said corresponding author Karen C. Schliep, PhD, MSPH, associate professor in the university’s Division of Public Health.

Prior studies have shown modest associations between endometriosis and ovarian cancer, Dr. Schliep said in an interview. A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis found endometriosis conferred nearly double the risk of ovarian cancer, although associations varied by ovarian cancer histotype. Few studies have been large enough to assess associations between endometriosis types — including superficial or peritoneal endometriosis vs ovarian endometriomas or deep infiltrating endometriosis and ovarian cancer histotypes such as low-grade serous, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous carcinomas (type 1), and the most aggressive and lethal form, high-grade serous type 2, she said in an interview. “Our large health administrative database of over 11 million individuals with linked electronic health and cancer registry data allowed us to answer this as yet poorly studied research question.”

Study Details

Drawing on Utah electronic health records from 1992 to 2019, the investigators matched 78,893 women with endometriosis in a 1:5 ratio to unaffected women. Cases were categorized as superficial endometriosis, ovarian endometriomas, deep infiltrating endometriosis, or other, and the types of endometriosis were matched to ovarian cancer histotypes.

The mean age of patients at first endometriosis diagnosis was 36 and the mean follow-up was 12 years. Compared with controls, endometriosis patients were more likely to be nulliparous (31% vs 24%) and to have had a hysterectomy (39% vs 6%) during follow-up.

There were 596 reported cases of ovarian cancer in the cohort. Those with incident endometriosis were 4.2 times more likely to develop ovarian cancer (95% CI, 3.59-4.91), 7.48 times more likely to develop type 1 ovarian cancer (95% CI, 5.80-9.65), and 2.70 times more likely to develop type 2 ovarian cancer (95% CI, 2.09-3.49) compared with those without endometriosis.

The magnitudes of these associations varied by endometriosis subtype. Individuals diagnosed with deep infiltrating endometriosis and/or ovarian endometriomas had 9.66 times the risk of ovarian cancer vs individuals without endometriosis (95% CI, 7.77-12.00). “Women with, compared to without, more severe endometriosis had a 19-fold higher risk of type 1 ovarian cancer, including endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous, and low-grade serous,” Dr. Schliep said, with associated risk highest for malignant subtypes such as clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma (adjusted hazard ratios, 11.15 and 7.96, respectively.

According to Dr. Schliep, physicians should encourage endometriosis patients to be aware of but not worry about ovarian cancer risk because the likelihood of developing it remains low. For their part, patients can reduce their risk of cancer through a balanced diet with low intake of alcohol, regular exercise, a healthy weight, and abstention from smoking.

Her message for researchers is as follows: “We need more studies that explore how different types of endometriosis impact different types of ovarian cancer risk. These studies will guide improved ovarian cancer screening and prevention strategies among women with severe endometriosis, with or without other important ovarian cancer risk factors such as BRCA 1/2 variations.”

An accompanying editorial called the Utah study “eloquent” and noted its distinguishing contribution of observing associations between subtypes of endometriosis with overall risk for ovarian cancer as well as histologic subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer.

Nevertheless, Michael T. McHale, MD, of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at Moores Cancer Center, UC San Diego Health, University of California, expressed some methodological concerns. Although the authors attempted to control for key confounders, he noted, the dataset could not provide details on the medical management of endometriosis, such as oral contraceptives or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. “Additionally, there is a possibility that women in the control cohort could have had undiagnosed endometriosis,” he wrote.

Furthermore, making clinical recommendations from these reported observations, particularly with respect to deep infiltrating endometriosis, would require a clear and consistent definition of this type in the dataset over the entire study interval from 1992 to 2019 and for the state of Utah, which the authors did not provide.

“Despite this potential challenge, the increased risk associated with deep infiltrating and/or ovarian endometriosis was clearly significant,” Dr. McHale wrote.

And although the absolute number of ovarian cancers is limited, in his view, the increased risk is sufficiently significant to advise women who have completed childbearing or have alternative fertility options to consider “more definitive surgery.”

This study was supported by multiple not-for-profit agencies, including the National Cancer Institute, the University of Utah, the National Center for Research Resources, the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, the Utah Cancer Registry, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Huntsman Cancer Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Doris Duke Foundation. Dr. Barnard reported grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Epi Excellence LLC outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported similar funding from nonprofit agencies or private research organizations. Dr Schliep disclosed no competing interests. Dr McHale reported educational consulting for Eisai Training outside the submitted work.

Ovarian cancer risk was higher in women with endometriosis overall and markedly increased in those with severe forms, a large population-based cohort study found.

The findings, published in JAMA, suggest these women may benefit from counseling on ovarian cancer risk and prevention and potentially from targeted screening, according to a group led by Mollie E. Barnard, ScD, of the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

While the absolute increase in number of cases was small, endometriosis patients overall had a more than fourfold higher risk for any type of ovarian cancer. Those with more severe forms, such as ovarian endometriomas or deep infiltrating endometriosis, had a nearly 10-fold higher risk of any type of ovarian cancer. In addition, those with more severe endometriosis had a 19-fold higher risk of type 1 (slow-growing) ovarian cancer and almost three times the risk of the more aggressive type 2.

“Given the rarity of ovarian cancer, the excess risk was relatively small, with 10-20 additional cases per 10,000 women. Nevertheless, women with endometriosis, notably the more severe subtypes, may be an important population for targeted cancer screening and prevention studies,” said corresponding author Karen C. Schliep, PhD, MSPH, associate professor in the university’s Division of Public Health.

Prior studies have shown modest associations between endometriosis and ovarian cancer, Dr. Schliep said in an interview. A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis found endometriosis conferred nearly double the risk of ovarian cancer, although associations varied by ovarian cancer histotype. Few studies have been large enough to assess associations between endometriosis types — including superficial or peritoneal endometriosis vs ovarian endometriomas or deep infiltrating endometriosis and ovarian cancer histotypes such as low-grade serous, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous carcinomas (type 1), and the most aggressive and lethal form, high-grade serous type 2, she said in an interview. “Our large health administrative database of over 11 million individuals with linked electronic health and cancer registry data allowed us to answer this as yet poorly studied research question.”

Study Details

Drawing on Utah electronic health records from 1992 to 2019, the investigators matched 78,893 women with endometriosis in a 1:5 ratio to unaffected women. Cases were categorized as superficial endometriosis, ovarian endometriomas, deep infiltrating endometriosis, or other, and the types of endometriosis were matched to ovarian cancer histotypes.

The mean age of patients at first endometriosis diagnosis was 36 and the mean follow-up was 12 years. Compared with controls, endometriosis patients were more likely to be nulliparous (31% vs 24%) and to have had a hysterectomy (39% vs 6%) during follow-up.

There were 596 reported cases of ovarian cancer in the cohort. Those with incident endometriosis were 4.2 times more likely to develop ovarian cancer (95% CI, 3.59-4.91), 7.48 times more likely to develop type 1 ovarian cancer (95% CI, 5.80-9.65), and 2.70 times more likely to develop type 2 ovarian cancer (95% CI, 2.09-3.49) compared with those without endometriosis.

The magnitudes of these associations varied by endometriosis subtype. Individuals diagnosed with deep infiltrating endometriosis and/or ovarian endometriomas had 9.66 times the risk of ovarian cancer vs individuals without endometriosis (95% CI, 7.77-12.00). “Women with, compared to without, more severe endometriosis had a 19-fold higher risk of type 1 ovarian cancer, including endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous, and low-grade serous,” Dr. Schliep said, with associated risk highest for malignant subtypes such as clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma (adjusted hazard ratios, 11.15 and 7.96, respectively.

According to Dr. Schliep, physicians should encourage endometriosis patients to be aware of but not worry about ovarian cancer risk because the likelihood of developing it remains low. For their part, patients can reduce their risk of cancer through a balanced diet with low intake of alcohol, regular exercise, a healthy weight, and abstention from smoking.

Her message for researchers is as follows: “We need more studies that explore how different types of endometriosis impact different types of ovarian cancer risk. These studies will guide improved ovarian cancer screening and prevention strategies among women with severe endometriosis, with or without other important ovarian cancer risk factors such as BRCA 1/2 variations.”

An accompanying editorial called the Utah study “eloquent” and noted its distinguishing contribution of observing associations between subtypes of endometriosis with overall risk for ovarian cancer as well as histologic subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer.

Nevertheless, Michael T. McHale, MD, of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at Moores Cancer Center, UC San Diego Health, University of California, expressed some methodological concerns. Although the authors attempted to control for key confounders, he noted, the dataset could not provide details on the medical management of endometriosis, such as oral contraceptives or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. “Additionally, there is a possibility that women in the control cohort could have had undiagnosed endometriosis,” he wrote.

Furthermore, making clinical recommendations from these reported observations, particularly with respect to deep infiltrating endometriosis, would require a clear and consistent definition of this type in the dataset over the entire study interval from 1992 to 2019 and for the state of Utah, which the authors did not provide.

“Despite this potential challenge, the increased risk associated with deep infiltrating and/or ovarian endometriosis was clearly significant,” Dr. McHale wrote.

And although the absolute number of ovarian cancers is limited, in his view, the increased risk is sufficiently significant to advise women who have completed childbearing or have alternative fertility options to consider “more definitive surgery.”

This study was supported by multiple not-for-profit agencies, including the National Cancer Institute, the University of Utah, the National Center for Research Resources, the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, the Utah Cancer Registry, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Huntsman Cancer Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Doris Duke Foundation. Dr. Barnard reported grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Epi Excellence LLC outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported similar funding from nonprofit agencies or private research organizations. Dr Schliep disclosed no competing interests. Dr McHale reported educational consulting for Eisai Training outside the submitted work.

FROM JAMA

Benefit of Massage Therapy for Pain Unclear

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Ultrasound and Its Role In Diagnosing and Managing Endometriosis

Introduction: Imaging for Endometriosis — A Necessary Prerequisite

While the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis remains laparoscopy, it is now recognized that thorough evaluation via ultrasound offers an acceptable, less expensive, and less invasive alternative. It is especially useful for the diagnosis of deep infiltrative disease, which penetrates more than 5 mm into the peritoneum, ovarian endometrioma, and when anatomic distortion occurs, such as to the path of the ureter.

Besides establishing the diagnosis, ultrasound imaging has become, along with MRI, the most important aid for proper preoperative planning. Not only does imaging provide the surgeon and patient with knowledge regarding the extent of the upcoming procedure, but it also allows the minimally invasive gynecologic (MIG) surgeon to involve colleagues, such as colorectal surgeons or urologists. For example, deep infiltrative endometriosis penetrating into the bowel mucosa will require a discoid or segmental bowel resection.

While many endometriosis experts rely on MRI, many MIG surgeons are dependent on ultrasound. I would not consider taking a patient with signs and symptoms suggestive of endometriosis to surgery without 2D/3D transvaginal ultrasound. If the patient possesses a uterus, a saline-infused sonogram is performed to potentially diagnose adenomyosis.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Professor Caterina Exacoustos MD, PhD, associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata,” to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to discuss “Ultrasound and Its Role in the Diagnosis of and Management of Endometriosis, Including DIE.”

Prof. Exacoustos’ main areas of interest are endometriosis and benign diseases including uterine pathology and infertility. Her extensive body of work comprises over 120 scientific publications and numerous book chapters both in English and in Italian.

Prof. Exacoustos continues to be one of the most well respected lecturers speaking about ultrasound throughout the world.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest to report.

Ultrasound and Its Role In Diagnosing and Managing Endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately 10%-20% of premenopausal women worldwide. It is the leading cause of chronic pelvic pain, is often associated with infertility, and has a significant impact on quality of life. Although the natural history of endometriosis remains unknown, emerging evidence suggests that the pathophysiological steps of initiation and development of endometriosis must occur earlier in the lifespan. Most notably, the onset of endometriosis-associated pain symptoms is often reported during adolescence and young adulthood.1

While many patients with endometriosis are referred with dysmenorrhea at a young age, at age ≤ 25 years,2 symptoms are often highly underestimated and considered to be normal and transient.3,4 Clinical and pelvic exams are often negative in young women, and delays in endometriosis diagnosis are well known.

The presentation of primary dysmenorrhea with no anatomical cause embodies the paradigm that dysmenorrhea in adolescents is most often an insignificant disorder. This perspective is probably a root cause of delayed endometriosis diagnosis in young patients. However, another issue behind delayed diagnosis is the reluctance of the physician to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy — historically the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis — for seemingly common symptoms such as dysmenorrhea in young patients.

Today we know that there are typical aspects of ultrasound imaging that identify endometriosis in the pelvis, and notably, the 2022 European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) endometriosis guideline5 recognizes imaging (ultrasound or MRI) as the standard for endometriosis diagnosis without requiring laparoscopic or histological confirmation.

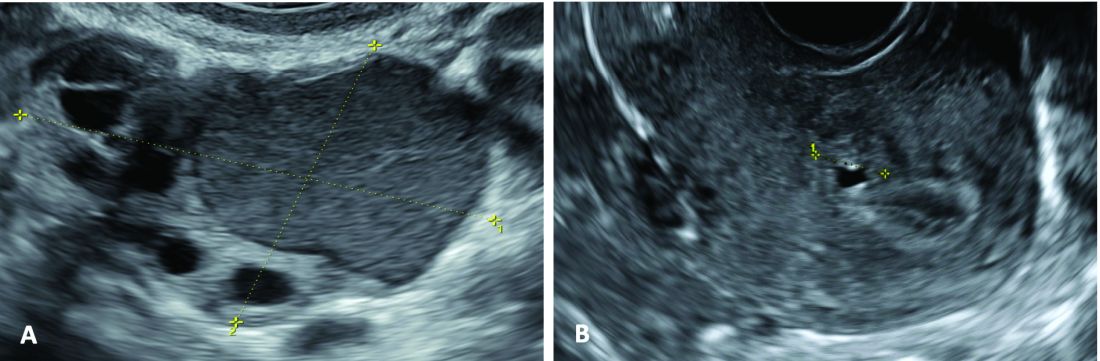

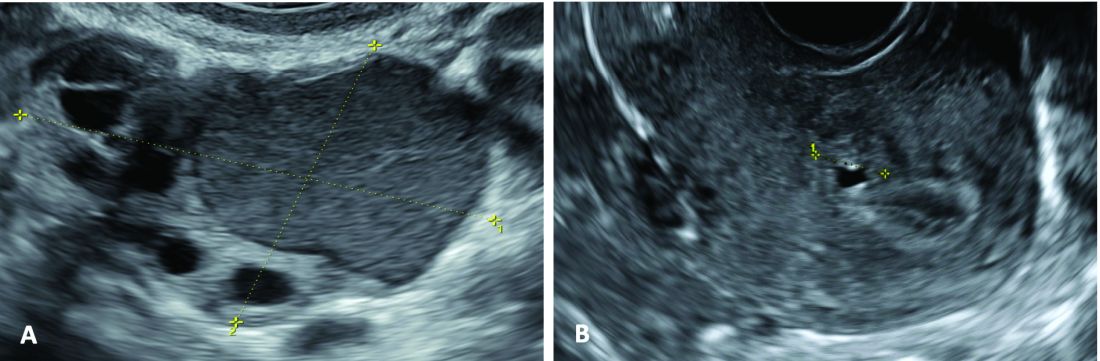

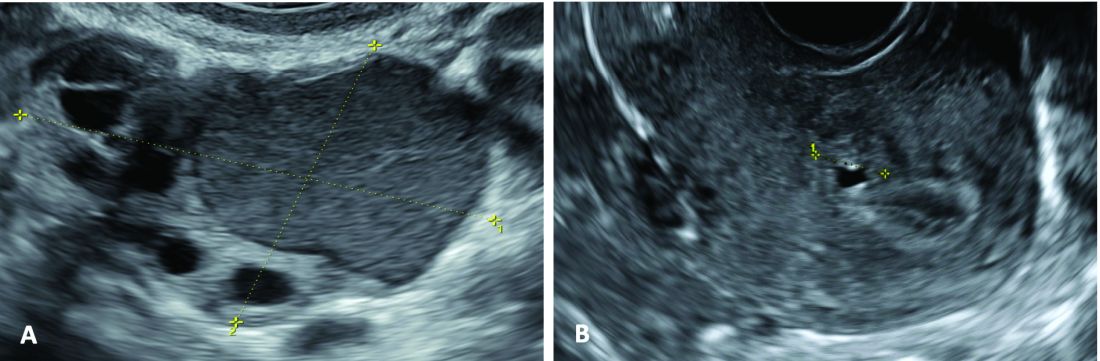

An early and noninvasive method of diagnosis aids in timely diagnosis and provides for the timely initiation of medical management to improve quality of life and prevent progression of disease (Figure 1).

(A. Transvaginal ultrasound appearance of a small ovarian endometrioma in a 16-year-old girl. Note the unilocular cyst with ground glass echogenicity surrounded by multifollicular ovarian tissue. B. Ultrasound image of a retroverted uterus of an 18-year-old girl with focal adenomyosis of the posterior wall. Note the round cystic anechoic areas in the inner myometrium or junctional zone. The small intra-myometrial cyst is surrounded by a hyperechoic ring).

Indeed, the typical appearance of endometriotic pelvic lesions on transvaginal sonography, such as endometriomas and rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) — as well as adenomyosis – can be medically treated without histologic confirmation .

When surgery is advisable, ultrasound findings also play a valuable role in presurgical staging, planning, and counseling for patients of all ages. Determining the extent and location of DIE preoperatively, for instance, facilitates the engagement of the appropriate surgical specialists so that multiple surgeries can be avoided. It also enables patients to be optimally informed before surgery of possible outcomes and complications.

Moreover, in the context of infertility, ultrasound can be a valuable tool for understanding uterine pathology and assessing for adenomyosis so that affected patients may be treated surgically or medically before turning to assisted reproductive technology.

Uniformity, Standardization in the Sonographic Assessment

In Europe, as in the United States, transvaginal sonography (TVS) is the first-line imaging tool for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. In Europe, many ob.gyns. perform ultrasound themselves, as do treating surgeons. When diagnostic findings are negative but clinical suspicion is high, MRI is often utilized. Laparoscopy may then be considered in patients with negative imaging results.

Efforts to standardize terms, definitions, measurements, and sonographic features of different types of endometriosis have been made to make it easier for physicians to share data and communicate with each other. A lack of uniformity has contributed to variability in the reported diagnostic accuracy of TVS.

About 10 years ago, in one such effort, we assessed the accuracy of TVS for DIE by comparing TVS results with laparoscopic/histologic findings, and developed an ultrasound mapping system to accurately record the location, size and depth of lesions visualized by TVS. The accuracy of TVS ranged from 76% for the diagnosis of vaginal endometriosis to 97% for the diagnosis of bladder lesions and posterior cul-de-sac obliteration. Accuracy was 93% and 91% for detecting ureteral involvement (right and left); 87% for uterosacral ligament endometriotic lesions; and 87% for parametrial involvement.6

Shortly after, with a focus on DIE, expert sonographers and physician-sonographers from across Europe — as well as some experts from Australia, Japan, Brazil, Chile, and the United States (Y. Osuga from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School) — came together to agree on a uniform approach to the sonographic evaluation for suspected endometriosis and a standardization of terminology.

The consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group details four steps for examining women with suspected DIE: 1) Evaluation of the uterus and adnexa, 2) evaluation of transvaginal sonographic “soft markers” (ie. site-specific tenderness and ovarian mobility), 3) assessment of the status of the posterior cul-de-sac using real-time ultrasound-based “sliding sign,” and 4) assessment for DIE nodules in the anterior and posterior compartments.7

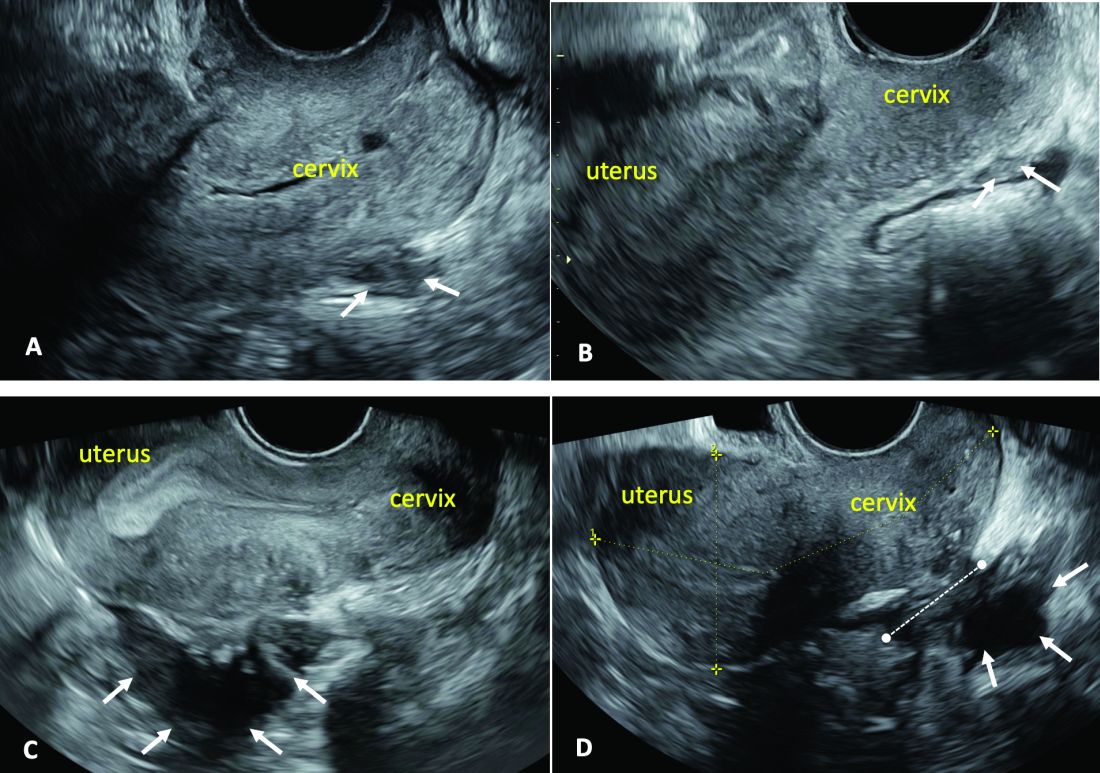

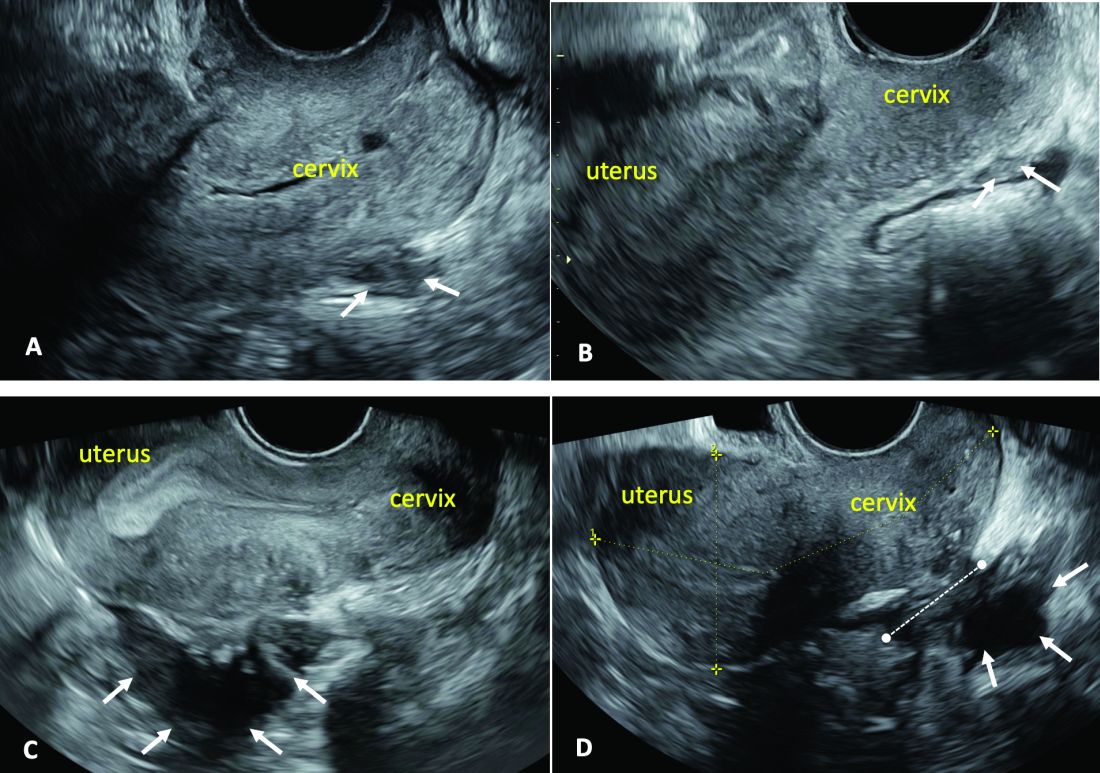

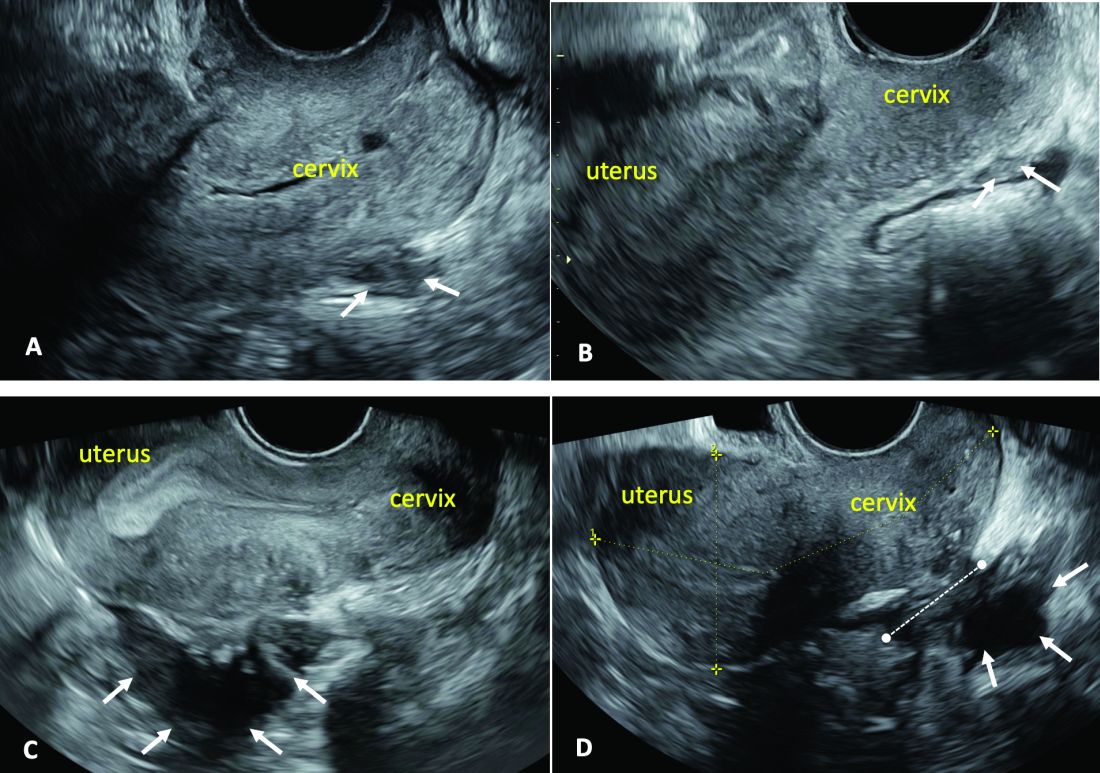

Our paper describing a mapping system and the IDEA paper describe how to detect deep endometriosis in the pelvis by utilizing an ultrasound view of normal anatomy and pelvic organ structure to provide landmarks for accurately defining the site of DIE lesions (Figure 2).

(A. Ultrasound appearance of a small DIE lesion of the retrocervical area [white arrows], which involved the torus uterinum and the right uterosacral ligament [USL]. The lesion appears as hypoechoic tissue with irregular margins caused by the fibrosis induced by the DIE. B. TVS appearance of small nodules of DIE of the left USL. Note the small retrocervical DIE lesion [white arrows], which appears hypoechoic due to the infiltration of the hyperechoic USL. C) Ultrasound appearance of a DIE nodule of the recto-sigmoid wall. Note the hypoechoic thickening of the muscular layers of the bowel wall attached to the corpus of the uterus and the adenomyosis of the posterior wall. The retrocervical area is free. D. TVS appearance of nodules of DIE of the lower rectal wall. Note the hypoechoic lesion [white arrows] of the rectum is attached to a retrocervical DIE fibrosis of the torus and USL [white dotted line]).

So-called rectovaginal endometriosis can be well assessed, for instance, since the involvement of the rectum, sigmoid colon, vaginal wall, rectovaginal septum, and posterior cul-de-sac uterosacral ligament can be seen by ultrasound as a single structure, making the location, size, and depth of any lesions discernible.

Again, this evaluation of the extent of disease is important for presurgical assessment so the surgeon can organize the right team and time of surgery and so the patient can be counseled on the advantages and possible complications of the treatment.

Notably, an accurate ultrasound description of pelvic endometriosis is helpful for accurate classification of disease. Endometriosis classification systems such as that of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL)8 and the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM),9 as well as the #Enzian surgical description system,10 have been adapted to cover findings from ultrasound as well as MRI imaging.

A Systematic Evaluation

In keeping with the IDEA consensus opinion and based on our years of experience at the University of Rome, I advise that patients with typical pain symptoms of endometriosis or infertility undergo an accurate sonographic assessment of the pelvis with particular evaluation not only of the uterus and ovaries but of all pelvic retroperitoneal spaces.

The TVS examination should start with a slightly filled bladder, which permits a better evaluation of the bladder walls and the presence of endometriotic nodules. These nodules appear as hyperechoic linear or spherical lesions bulging toward the lumen and involving the serosa, muscularis, or (sub)mucosa of the bladder.

Then, an accurate evaluation of the uterus in 2D and 3D permits the diagnosis of adenomyosis. 3D sonographic evaluation of the myometrium and of the junctional zone are important; alteration and infiltration of the junctional zone and the presence of small adenomyotic cysts in the inner or outer myometrium are direct, specific signs of adenomyosis and should be ruled out in patients with dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, and pregnancy complications.

Endometriomas of the ovaries can be easily detected as having the typical appearance of a cyst with ground glass content. Adhesions of the ovaries and the uterus also should be evaluated with a dynamic ultrasound approach that utilizes the sliding sign and mobilization by palpation of the organs during the TVS scan.

Finally, the posterior and lateral retroperitoneal compartments should be carefully evaluated, with symptoms guiding the TVS examination whenever possible. Deep endometriotic nodules of the rectum appear as hypoechoic lesions or linear or nodular retroperitoneal thickening with irregular borders, penetrating into the intestinal wall and distorting its normal structure. In young patients, it seems very important to assess for small lesions below the peritoneum between the vagina and rectum, and in the parametria and around the ureter and nerves — lesions that, notably, would not be seen by diagnostic laparoscopy.

The Evaluation of Young Patients

In adolescent and young patients, endometriosis and adenomyosis are often present with small lesions and shallow tissue invasion, making a very careful and experienced approach to ultrasound essential for detection. Endometriomas are often of small diameter, and DIE is not always easily diagnosed because retroperitoneal lesions are similarly very small.

In a series of 270 adolescents (ages 12-20) who were referred to our outpatient gynecologic ultrasound unit over a 5-year period for various indications, at least one ultrasound feature of endometriosis was observed in 13.3%. In those with dysmenorrhea, the detection of endometriosis increased to 21%. Endometrioma was the most common type of endometriosis we found in the study, but DIE and adenomyosis were found in 4%-11%.

Although endometriotic lesions typically are small in young patients, they are often associated with severe pain symptoms, including chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, and dyschezia, all of which can have a serious effect on the quality of life of these young women. These symptoms keep them away from school during menstruation, away from sports, and cause painful intercourse and infertility. In young patients, an accurate TVS can provide a lot of information, and the ability to detect retroperitoneal endometriotic lesions and adenomyosis is probably better than with purely diagnostic laparoscopy, which would evaluate only superficial lesions.

TVS or, when needed, transrectal ultrasound, can enable adequate treatment and follow-up of the disease and its symptoms. There are no guidelines recommending adequate follow-up times to evaluate the effectiveness of medical therapy in patients with ultrasound signs of endometriosis. (Likewise, there are no indications for follow-up in patients with severe dysmenorrhea without ultrasound signs of endometriosis.) Certainly, our studies suggest careful evaluation over time of young patients with severe dysmenorrhea by serial ultrasound scans. With such follow-up, disease progress can be monitored and the medical or surgical treatment approach modified if needed.

The diagnosis of endometriosis at a young age has significant benefits not only in avoiding or reducing progression of the disease, but also in improving quality of life and aiding women in their desire for pregnancy.

Dr. Exacoustos is associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata.” She has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Zondervan KT et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-56.

2. Greene R et al. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9.

3. Chapron C et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:S7-12.

4. Randhawa AE et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34:643-8.

5. Becker CM et al. Hum Reprod Open. 2022(2):hoac009.

6. Exacoustos C et al. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:143-9. 7. Guerriero S et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):318-32.

8. Abrao MS et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1941-50.9. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817-21. 10. Keckstein J et al. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1165-75.

11. Martire FG et al. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(5):1049-57.

Introduction: Imaging for Endometriosis — A Necessary Prerequisite

While the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis remains laparoscopy, it is now recognized that thorough evaluation via ultrasound offers an acceptable, less expensive, and less invasive alternative. It is especially useful for the diagnosis of deep infiltrative disease, which penetrates more than 5 mm into the peritoneum, ovarian endometrioma, and when anatomic distortion occurs, such as to the path of the ureter.

Besides establishing the diagnosis, ultrasound imaging has become, along with MRI, the most important aid for proper preoperative planning. Not only does imaging provide the surgeon and patient with knowledge regarding the extent of the upcoming procedure, but it also allows the minimally invasive gynecologic (MIG) surgeon to involve colleagues, such as colorectal surgeons or urologists. For example, deep infiltrative endometriosis penetrating into the bowel mucosa will require a discoid or segmental bowel resection.

While many endometriosis experts rely on MRI, many MIG surgeons are dependent on ultrasound. I would not consider taking a patient with signs and symptoms suggestive of endometriosis to surgery without 2D/3D transvaginal ultrasound. If the patient possesses a uterus, a saline-infused sonogram is performed to potentially diagnose adenomyosis.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Professor Caterina Exacoustos MD, PhD, associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata,” to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to discuss “Ultrasound and Its Role in the Diagnosis of and Management of Endometriosis, Including DIE.”

Prof. Exacoustos’ main areas of interest are endometriosis and benign diseases including uterine pathology and infertility. Her extensive body of work comprises over 120 scientific publications and numerous book chapters both in English and in Italian.

Prof. Exacoustos continues to be one of the most well respected lecturers speaking about ultrasound throughout the world.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest to report.

Ultrasound and Its Role In Diagnosing and Managing Endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately 10%-20% of premenopausal women worldwide. It is the leading cause of chronic pelvic pain, is often associated with infertility, and has a significant impact on quality of life. Although the natural history of endometriosis remains unknown, emerging evidence suggests that the pathophysiological steps of initiation and development of endometriosis must occur earlier in the lifespan. Most notably, the onset of endometriosis-associated pain symptoms is often reported during adolescence and young adulthood.1

While many patients with endometriosis are referred with dysmenorrhea at a young age, at age ≤ 25 years,2 symptoms are often highly underestimated and considered to be normal and transient.3,4 Clinical and pelvic exams are often negative in young women, and delays in endometriosis diagnosis are well known.

The presentation of primary dysmenorrhea with no anatomical cause embodies the paradigm that dysmenorrhea in adolescents is most often an insignificant disorder. This perspective is probably a root cause of delayed endometriosis diagnosis in young patients. However, another issue behind delayed diagnosis is the reluctance of the physician to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy — historically the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis — for seemingly common symptoms such as dysmenorrhea in young patients.

Today we know that there are typical aspects of ultrasound imaging that identify endometriosis in the pelvis, and notably, the 2022 European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) endometriosis guideline5 recognizes imaging (ultrasound or MRI) as the standard for endometriosis diagnosis without requiring laparoscopic or histological confirmation.

An early and noninvasive method of diagnosis aids in timely diagnosis and provides for the timely initiation of medical management to improve quality of life and prevent progression of disease (Figure 1).

(A. Transvaginal ultrasound appearance of a small ovarian endometrioma in a 16-year-old girl. Note the unilocular cyst with ground glass echogenicity surrounded by multifollicular ovarian tissue. B. Ultrasound image of a retroverted uterus of an 18-year-old girl with focal adenomyosis of the posterior wall. Note the round cystic anechoic areas in the inner myometrium or junctional zone. The small intra-myometrial cyst is surrounded by a hyperechoic ring).

Indeed, the typical appearance of endometriotic pelvic lesions on transvaginal sonography, such as endometriomas and rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) — as well as adenomyosis – can be medically treated without histologic confirmation .

When surgery is advisable, ultrasound findings also play a valuable role in presurgical staging, planning, and counseling for patients of all ages. Determining the extent and location of DIE preoperatively, for instance, facilitates the engagement of the appropriate surgical specialists so that multiple surgeries can be avoided. It also enables patients to be optimally informed before surgery of possible outcomes and complications.

Moreover, in the context of infertility, ultrasound can be a valuable tool for understanding uterine pathology and assessing for adenomyosis so that affected patients may be treated surgically or medically before turning to assisted reproductive technology.

Uniformity, Standardization in the Sonographic Assessment

In Europe, as in the United States, transvaginal sonography (TVS) is the first-line imaging tool for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. In Europe, many ob.gyns. perform ultrasound themselves, as do treating surgeons. When diagnostic findings are negative but clinical suspicion is high, MRI is often utilized. Laparoscopy may then be considered in patients with negative imaging results.

Efforts to standardize terms, definitions, measurements, and sonographic features of different types of endometriosis have been made to make it easier for physicians to share data and communicate with each other. A lack of uniformity has contributed to variability in the reported diagnostic accuracy of TVS.

About 10 years ago, in one such effort, we assessed the accuracy of TVS for DIE by comparing TVS results with laparoscopic/histologic findings, and developed an ultrasound mapping system to accurately record the location, size and depth of lesions visualized by TVS. The accuracy of TVS ranged from 76% for the diagnosis of vaginal endometriosis to 97% for the diagnosis of bladder lesions and posterior cul-de-sac obliteration. Accuracy was 93% and 91% for detecting ureteral involvement (right and left); 87% for uterosacral ligament endometriotic lesions; and 87% for parametrial involvement.6

Shortly after, with a focus on DIE, expert sonographers and physician-sonographers from across Europe — as well as some experts from Australia, Japan, Brazil, Chile, and the United States (Y. Osuga from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School) — came together to agree on a uniform approach to the sonographic evaluation for suspected endometriosis and a standardization of terminology.

The consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group details four steps for examining women with suspected DIE: 1) Evaluation of the uterus and adnexa, 2) evaluation of transvaginal sonographic “soft markers” (ie. site-specific tenderness and ovarian mobility), 3) assessment of the status of the posterior cul-de-sac using real-time ultrasound-based “sliding sign,” and 4) assessment for DIE nodules in the anterior and posterior compartments.7

Our paper describing a mapping system and the IDEA paper describe how to detect deep endometriosis in the pelvis by utilizing an ultrasound view of normal anatomy and pelvic organ structure to provide landmarks for accurately defining the site of DIE lesions (Figure 2).

(A. Ultrasound appearance of a small DIE lesion of the retrocervical area [white arrows], which involved the torus uterinum and the right uterosacral ligament [USL]. The lesion appears as hypoechoic tissue with irregular margins caused by the fibrosis induced by the DIE. B. TVS appearance of small nodules of DIE of the left USL. Note the small retrocervical DIE lesion [white arrows], which appears hypoechoic due to the infiltration of the hyperechoic USL. C) Ultrasound appearance of a DIE nodule of the recto-sigmoid wall. Note the hypoechoic thickening of the muscular layers of the bowel wall attached to the corpus of the uterus and the adenomyosis of the posterior wall. The retrocervical area is free. D. TVS appearance of nodules of DIE of the lower rectal wall. Note the hypoechoic lesion [white arrows] of the rectum is attached to a retrocervical DIE fibrosis of the torus and USL [white dotted line]).

So-called rectovaginal endometriosis can be well assessed, for instance, since the involvement of the rectum, sigmoid colon, vaginal wall, rectovaginal septum, and posterior cul-de-sac uterosacral ligament can be seen by ultrasound as a single structure, making the location, size, and depth of any lesions discernible.

Again, this evaluation of the extent of disease is important for presurgical assessment so the surgeon can organize the right team and time of surgery and so the patient can be counseled on the advantages and possible complications of the treatment.

Notably, an accurate ultrasound description of pelvic endometriosis is helpful for accurate classification of disease. Endometriosis classification systems such as that of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL)8 and the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM),9 as well as the #Enzian surgical description system,10 have been adapted to cover findings from ultrasound as well as MRI imaging.

A Systematic Evaluation

In keeping with the IDEA consensus opinion and based on our years of experience at the University of Rome, I advise that patients with typical pain symptoms of endometriosis or infertility undergo an accurate sonographic assessment of the pelvis with particular evaluation not only of the uterus and ovaries but of all pelvic retroperitoneal spaces.

The TVS examination should start with a slightly filled bladder, which permits a better evaluation of the bladder walls and the presence of endometriotic nodules. These nodules appear as hyperechoic linear or spherical lesions bulging toward the lumen and involving the serosa, muscularis, or (sub)mucosa of the bladder.

Then, an accurate evaluation of the uterus in 2D and 3D permits the diagnosis of adenomyosis. 3D sonographic evaluation of the myometrium and of the junctional zone are important; alteration and infiltration of the junctional zone and the presence of small adenomyotic cysts in the inner or outer myometrium are direct, specific signs of adenomyosis and should be ruled out in patients with dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, and pregnancy complications.

Endometriomas of the ovaries can be easily detected as having the typical appearance of a cyst with ground glass content. Adhesions of the ovaries and the uterus also should be evaluated with a dynamic ultrasound approach that utilizes the sliding sign and mobilization by palpation of the organs during the TVS scan.

Finally, the posterior and lateral retroperitoneal compartments should be carefully evaluated, with symptoms guiding the TVS examination whenever possible. Deep endometriotic nodules of the rectum appear as hypoechoic lesions or linear or nodular retroperitoneal thickening with irregular borders, penetrating into the intestinal wall and distorting its normal structure. In young patients, it seems very important to assess for small lesions below the peritoneum between the vagina and rectum, and in the parametria and around the ureter and nerves — lesions that, notably, would not be seen by diagnostic laparoscopy.

The Evaluation of Young Patients

In adolescent and young patients, endometriosis and adenomyosis are often present with small lesions and shallow tissue invasion, making a very careful and experienced approach to ultrasound essential for detection. Endometriomas are often of small diameter, and DIE is not always easily diagnosed because retroperitoneal lesions are similarly very small.

In a series of 270 adolescents (ages 12-20) who were referred to our outpatient gynecologic ultrasound unit over a 5-year period for various indications, at least one ultrasound feature of endometriosis was observed in 13.3%. In those with dysmenorrhea, the detection of endometriosis increased to 21%. Endometrioma was the most common type of endometriosis we found in the study, but DIE and adenomyosis were found in 4%-11%.

Although endometriotic lesions typically are small in young patients, they are often associated with severe pain symptoms, including chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, and dyschezia, all of which can have a serious effect on the quality of life of these young women. These symptoms keep them away from school during menstruation, away from sports, and cause painful intercourse and infertility. In young patients, an accurate TVS can provide a lot of information, and the ability to detect retroperitoneal endometriotic lesions and adenomyosis is probably better than with purely diagnostic laparoscopy, which would evaluate only superficial lesions.

TVS or, when needed, transrectal ultrasound, can enable adequate treatment and follow-up of the disease and its symptoms. There are no guidelines recommending adequate follow-up times to evaluate the effectiveness of medical therapy in patients with ultrasound signs of endometriosis. (Likewise, there are no indications for follow-up in patients with severe dysmenorrhea without ultrasound signs of endometriosis.) Certainly, our studies suggest careful evaluation over time of young patients with severe dysmenorrhea by serial ultrasound scans. With such follow-up, disease progress can be monitored and the medical or surgical treatment approach modified if needed.

The diagnosis of endometriosis at a young age has significant benefits not only in avoiding or reducing progression of the disease, but also in improving quality of life and aiding women in their desire for pregnancy.

Dr. Exacoustos is associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata.” She has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Zondervan KT et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-56.

2. Greene R et al. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9.

3. Chapron C et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:S7-12.

4. Randhawa AE et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34:643-8.

5. Becker CM et al. Hum Reprod Open. 2022(2):hoac009.

6. Exacoustos C et al. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:143-9. 7. Guerriero S et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):318-32.

8. Abrao MS et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1941-50.9. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817-21. 10. Keckstein J et al. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1165-75.

11. Martire FG et al. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(5):1049-57.

Introduction: Imaging for Endometriosis — A Necessary Prerequisite

While the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis remains laparoscopy, it is now recognized that thorough evaluation via ultrasound offers an acceptable, less expensive, and less invasive alternative. It is especially useful for the diagnosis of deep infiltrative disease, which penetrates more than 5 mm into the peritoneum, ovarian endometrioma, and when anatomic distortion occurs, such as to the path of the ureter.

Besides establishing the diagnosis, ultrasound imaging has become, along with MRI, the most important aid for proper preoperative planning. Not only does imaging provide the surgeon and patient with knowledge regarding the extent of the upcoming procedure, but it also allows the minimally invasive gynecologic (MIG) surgeon to involve colleagues, such as colorectal surgeons or urologists. For example, deep infiltrative endometriosis penetrating into the bowel mucosa will require a discoid or segmental bowel resection.

While many endometriosis experts rely on MRI, many MIG surgeons are dependent on ultrasound. I would not consider taking a patient with signs and symptoms suggestive of endometriosis to surgery without 2D/3D transvaginal ultrasound. If the patient possesses a uterus, a saline-infused sonogram is performed to potentially diagnose adenomyosis.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Professor Caterina Exacoustos MD, PhD, associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata,” to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to discuss “Ultrasound and Its Role in the Diagnosis of and Management of Endometriosis, Including DIE.”

Prof. Exacoustos’ main areas of interest are endometriosis and benign diseases including uterine pathology and infertility. Her extensive body of work comprises over 120 scientific publications and numerous book chapters both in English and in Italian.

Prof. Exacoustos continues to be one of the most well respected lecturers speaking about ultrasound throughout the world.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest to report.

Ultrasound and Its Role In Diagnosing and Managing Endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately 10%-20% of premenopausal women worldwide. It is the leading cause of chronic pelvic pain, is often associated with infertility, and has a significant impact on quality of life. Although the natural history of endometriosis remains unknown, emerging evidence suggests that the pathophysiological steps of initiation and development of endometriosis must occur earlier in the lifespan. Most notably, the onset of endometriosis-associated pain symptoms is often reported during adolescence and young adulthood.1

While many patients with endometriosis are referred with dysmenorrhea at a young age, at age ≤ 25 years,2 symptoms are often highly underestimated and considered to be normal and transient.3,4 Clinical and pelvic exams are often negative in young women, and delays in endometriosis diagnosis are well known.

The presentation of primary dysmenorrhea with no anatomical cause embodies the paradigm that dysmenorrhea in adolescents is most often an insignificant disorder. This perspective is probably a root cause of delayed endometriosis diagnosis in young patients. However, another issue behind delayed diagnosis is the reluctance of the physician to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy — historically the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis — for seemingly common symptoms such as dysmenorrhea in young patients.

Today we know that there are typical aspects of ultrasound imaging that identify endometriosis in the pelvis, and notably, the 2022 European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) endometriosis guideline5 recognizes imaging (ultrasound or MRI) as the standard for endometriosis diagnosis without requiring laparoscopic or histological confirmation.