User login

Partial meniscectomy of tears in the avascular zone remains one of the most common orthopedic procedures. While results of partial meniscectomy in younger patients have excellent short- to medium-term results, the long-term clinical outcomes are often less favorable.1-3 Repair in the avascular “white-white” zone has resulted in lower patient satisfaction scores and higher revision surgery rates.4-7 Consequently, most tears in this region have been treated with partial meniscectomy.

The inability to repair rather than resect menisci with avascular tears has led to extensive research. Techniques such as trephination and rasping to initiate an angiogenic response have had inconsistent and unreliable results when applied to the white-white zone.8-13 In contrast, Tasto and colleagues14 have shown that radiofrequency (RF) applied to hypovascular tissue can not only stimulate tissue vascularity, but also increase organization of fibroblastic cells. In addition, Tasto and colleagues15,16 have shown that RF application can significantly improve histologic healing and clinical outcomes in refractory cases of Achilles tendinopathy and lateral epicondylitis. In Japanese white rabbit menisci, Higuchi and coauthors17 applied monopolar RF at 60°C and 40W to avascular zone tears to fuse the tissue. They found a significant increase in fibroblast proliferation and fusion of collagen fibers at 2, 4, and 12 weeks after surgery. They also found significant acellular zones of meniscus tissue and attributed these findings to fibrochondrocyte death because of thermal treatment.

This body of research led to the present study, which evaluates the effect of low-temperature, bipolar RF stimulation, in conjunction with suture repair, on the healing of tears in the avascular white-white zone of the meniscus both in vivo and ex vivo. We performed gross and histologic analyses of the treatment groups for the in vivo aspect of the study and biochemical analyses to study the ex vivo effects of RF treatment. 3H-thymidine incorporation has been shown to be a reliable indicator of cellular proliferation in several studies, and this was measured in our treatment groups.18-21 In addition, the response of mitogenic growth factors (IGF-1, bFGF) and angiogenic markers (VEGF, αV) to RF treatment was studied.22 We hypothesized that bipolar RF application would show increased gross, histologic, and biochemical healing when combined with suture repair of longitudinal avascular zone meniscus tears.

Materials and Methods

Creation of Meniscal Tears

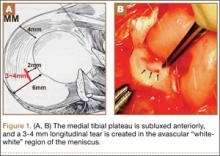

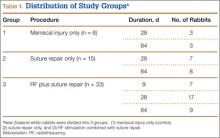

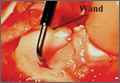

Fifty-four healthy, skeletally mature male and female adult New Zealand white rabbits aged 7 to 18 months were used for the study. All procedures conformed to the guidelines of our university’s institutional animal care and use committee and the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All rabbits underwent a surgical procedure in which a longitudinal tear was created in the avascular white-white zone of the medial meniscus. Using sterile technique and instrumentation, a medial parapatellar incision was made on the left knee of each rabbit. The patella was retracted laterally, exposing the medial meniscus. The tibia was then externally rotated to sublux the anterior horn of the medial meniscus anteriorly. A longitudinal full-thickness meniscal tear (3-4 mm in length) was created in the avascular zone (inner third) of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus using an 11-blade scalpel (Figures 1A, 1B). The location of the tear was grossly performed in the same location in each meniscus. The rabbits were randomly divided into 3 treatment groups: 1, 2, and 3 (Table 1). Group 1 (n = 6) served as a control with no repair or RF treatment applied. Group 2 (n = 15) underwent suture repair only of the meniscal tear using 5-0 nylon suture in a horizontal mattress pattern (Figure 2A). Group 3 (n = 33) underwent suture repair after RF stimulation was applied to both sides of the meniscus tear (Figures 2B, 2C). RF was applied using a 0.8-mm TOPAZ MicroDebrider (ArthroCare, Sunnyvale, California) set at level 4 (175 V-RMS) for 500 milliseconds. Lactated ringer’s solution was continuously infused through the probe via sterile tubing to prevent overheating.

After meniscal treatment, hemostasis of the surrounding surgical dissection was achieved to prevent hematoma formation, and the wounds were irrigated. The patellae were relocated and the arthrotomies were closed with a running 2-0 vicryl suture. Fascial and subcutaneous layers were closed with a running 3-0 vicryl suture, and skin was closed with subcuticular 4‑0 vicryl sutures. The rabbit limbs were allowed weight-bearing with unrestricted range of motion within 2x2x2-ft cages.

For all groups, menisci were explanted at 28 and 84 days for gross and histologic analysis. For biochemical assessments, menisci were explanted at 9, 28, and 84 days (Table 1).

Gross Analysis

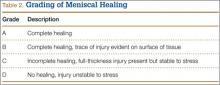

Immediately after specimen removal, all medial menisci were evaluated for gross morphology. A grading system was used for organization and classification of data (Table 2). Three blinded orthopedic surgeon-observers performed all grading. Grade A was considered complete healing of the meniscus. Grade B involved complete healing with a trace of injury remaining on the surface of the meniscus. Grade C represented incomplete healing with a full-thickness injury that was stable to stress of the repair site with an arthroscopic probe. Grade D had no healing with the injured region unstable to stress of the repair site with an arthroscopic probe.

Histologic Analysis and Microscopic Grading of Meniscal Healing

After gross evaluation by the 3 blinded observers, each meniscus was fixed for 24 hours in 10% buffered formalin. Each specimen was then embedded in paraffin and cut into 6-µm slices along the radial plane. The tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and microscopic grading was assigned. The grading system was the same as that used for gross morphologic analysis.

Biochemical Analysis

To determine whether RF treatment stimulated a healing response in the avascular zone of the meniscus, measurements of specific biochemical markers were analyzed at 9, 28, and 84 days after treatment. As a control, unrepaired meniscal tissue from the contralateral knee was also analyzed. 3H-thymidine incorporation into the meniscus was measured to assess cell proliferation.23 At sacrifice, control and treated menisci were dissected and immediately placed into sterile culture media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, antibiotic, and fungicide). 3H-thymidine was added at a concentration of 5µCi/mL of media to each tube. After incubation for 48 hours at 37°C under 5% CO2, the menisci were removed and dialyzed against water for 24 hours to remove unincorporated thymidine. After washing, the menisci were lyophilized, aliquots weighed, and radioactivity determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Results are expressed as counts per minute per mg dry tissue weight.

Semiquantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to determine mRNA expression of mitogenic growth factors, IGF-1 and bFGF, and angiogenic markers, αV and VEFG.24 National Institutes of Health (NIH) image-analysis software (version 1.61; NIH, Bethesda, Maryland) was used to quantitatively scan RT-PCR profiles after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide visualization. Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene, GAPDH.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean (SD) and evaluated using an unpaired Student t test between groups. Statistical significance was established at P < .05.

Results

Gross Morphology

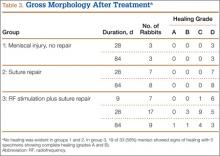

Analysis of gross morphology showed signs of healing only in the group treated with suture repair combined with RF treatment (Table 3). In group 1 (meniscal injury only) and group 2 (suture repair only), no healing occurred at 28 and 84 days (Figure 3A). A meniscal grading system was developed to better describe the varying levels of healing shown in the suture-plus-RF-treatment group (Table 2). Of the specimens that showed healing in group 3, 1 had complete healing (grade A) within the avascular zone of the meniscus at 84 days (Figure 3B). In addition, 4 specimens subjected to suture repair and RF treatment had complete healing with only a trace of injured tissue remaining (grade B). Fourteen specimens in group 3 had incomplete healing with lesions stable to stress suggesting early signs of healing (grade C). In total, 58% of menisci treated with RF showed signs of healing while the remaining 14 specimens in group 3 showed none (grade D).

Histologic Examination

The histology correlated well with gross analysis. No microscopic evidence of healing was seen in groups 1 and 2 (Figure 3C). Of the specimens treated with suture repair combined with RF, 19 (58%) showed varying degrees of histologic healing. While gross morphologic examination showed that only 1 specimen had complete healing, microscopic analysis showed that 1 specimen from group 3 had grade B healing on gross analysis but grade A healing on histologic analysis. Thus, upon histologic examination, 2 specimens showed complete healing of injuries in the avascular zone of the meniscus when treated with suture repair combined with RF treatment rather than the 1 specimen seen on gross morphology (Figure 3D).

Biochemical Analysis

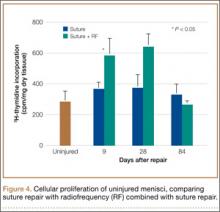

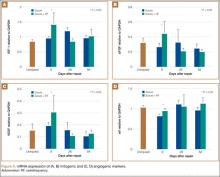

Biochemical assessments were performed at 9, 28, and 84 days after surgery. 3H-thymidine incorporation was studied as a marker for cellular proliferation, and its levels were significantly higher in meniscus explants treated with RF (Figure 4). The mean (SD) rate of incorporation for meniscal tears treated with suture repair plus RF was 590 (80) cpm/mg dry tissue at 9 days. This value was approximately 40% greater than the menisci treated with suture repair only, which had a mean (SD) value of 380 (30) cpm/mg (P < .05). Normal, unrepaired meniscal tissue had a mean (SD) 3H-thymidine incorporation rate of 250 (35) cpm/mg. By 84 days, thymidine levels returned to uninjured levels in both suture-only and RF-treated menisci. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that, 9 days after repair, the RF-treated menisci had increased mRNA expression of IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF, and αV relative to untreated repairs (Figure 5). There was a statistically significant acute phase response in IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF and αV in groups treated with RF at 9 days (P > .05).

Adverse Outcomes

There were no surgical complications. During the histologic evaluation, there were no incidences of fibrochondrocyte cell death or damage from the application of RF treatment.

Discussion

RF treatments have been used for many years in various medical and surgical applications. Presently, the most common implementation of RF is for cutting and coagulating tissue during surgery. More recently, however, several publications have shown that when used properly and safely, RF can be an effective surgical adjunct for tendinosis recalcitrant to conservative therapy.15-17,25-32

Many have suggested that RF coblation is successful in these clinical scenarios because of its ability to promote an increased angiogenic and fibroblastic response in hypovascular tissue.29,33,34

This body of literature led to the evaluation of RF coblation in treating meniscal tears in the avascular zone. Studies have shown poor success of meniscus repairs done in the avascular zone; however, our data demonstrate that supplementing suture repair with RF treatment may improve the acute-phase healing response. Although the control and suture-repair groups showed no signs of healing, the suture-repair-combined-with-RF-treatment group had 2 specimens in which complete gross and histologic healing occurred. In addition, 19 (58%) specimens in the RF group showed gross or histologic signs of healing.

Biochemically, 3H-thymidine incorporation was examined to assess cellular proliferation. Mitogenic (IGF, bFGF) and angiogenic (VEGF, αV) growth factors were measured as markers of an increased healing response. Compared with noninjured meniscal tissue, 3H-thymidine incorporation was significantly increased in both the suture and suture-combined-with-RF-treatment groups at 9 and 28 days after surgery. Between the suture and suture-RF groups, RF treatment led to a 40% greater increase in 3H-thymidine incorporation suggesting greater cellular proliferation in the immediate postoperative period. With respect to mitogenic and angiogenic factors, IGF, bFGF, VEGF, and αV were only significantly increased when RF was combined with suture repair. All 4 factors are important regulators of vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, wound healing, bone remodeling, and neurogenesis. The suture repair–only group showed no upregulation of these factors compared with uninjured controls.

Our study has several strengths. Using an animal model with menisci grossly similar to that of humans, we performed a controlled study comparing 2 treatment options, suture repair only and suture repair combined with RF treatment.35,36 The animal model also enabled second-look examinations at designated intervals. We analyzed the effect of RF treatment on concrete measures, such as gross, histologic, and biochemical healing. In particular, the biochemical analysis may indicate that RF treatment can increase the proliferative, mitogenic, and angiogenic capabilities of surrounding progenitor cells. This was evidenced by the statistically significant increase we saw in IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF, and αV at 9 and 28 days compared with controls.

Meniscal tears in the avascular zone represent a significant treatment dilemma for the physiologically young patient population. While partial meniscectomy provides excellent short-term relief, the long-term outcome of this intervention is degenerative joint disease. Meniscal repair in the central two-thirds of the meniscus has shown poor results. Our study presents data that show supplementing suture repair of avascular meniscal tears with RF can lead to increased gross, histologic, and biochemical healing in the New Zealand white rabbit. While these results are encouraging, studies with longer follow-up and specimens that represent the human menisci are necessary to determine whether these preliminary results would translate to human meniscal tears in the avascular zone.

Weaknesses of our study include the use of an animal model and the location of the tear created in the menisci. While using an animal model had many strengths, the results of our study are probably not strong enough to immediately extrapolate the use of RF in human meniscal repairs. However, the data we obtained are very encouraging and perhaps suggest that RF warrants human trials. Our open surgical technique made it difficult to create and repair a tear on the posterior horn of the medical meniscus without completely dislocating the knee anteriorly. As a result, the knees were subluxed anteriorly, and the meniscal tears and repairs were performed more anteriorly. The more anterior aspects of the menisci do not undergo the same rotational and axial loads as the posterior horn, and it is unclear whether this difference would contribute to the results we obtained from RF treatment. In addition, the tears were surgically created and the repair was done during the same procedure. Patients do not present in this manner, and this further underscores the need for a clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of this treatment option in humans.

Conclusion

RF-based supplementation of meniscal repairs in the avascular zone showed acute signs of biochemical healing in 58% of New Zealand white rabbit specimens. In addition, gross and histologic evaluations showed an increase in healing compared with controls. Two specimens treated with RF in combination with suture repair had complete healing. These results illustrate the effectiveness of RF in stimulating a healing response in hypovascular tissue. Clinical trials are necessary to determine the effectiveness of this treatment in humans.

1. Fauno P, Nielsen AB. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a long-term follow-up. Arthroscopy. 1992;8(3):345-349.

2. Lynch MA, Henning CE, Glick KR, Jr. Knee joint surface changes. Long-term follow-up meniscus tear treatment in stable anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Clin Orthop. 1983;172:148-153.

3. Roos H, Lauren M, Adalberth T, Roos EM, Jonsson K, Lohmander LS. Knee osteoarthritis after meniscectomy: prevalence of radiographic changes after twenty-one years, compared with matched controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(4):687-693.

4. Hennerbichler A, Moutos FT, Hennerbichler D, Weinberg JB, Guilak F. Repair response of the inner and outer regions of the porcine meniscus in vitro. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(5):754‑762.

5. Gershuni DH, Hargens AR, Danzig LA. Regional nutrition and cellularity of the meniscus. Implications for tear and repair. Sports Med. 1988;5(5):322-327.

6. Gershuni DH, Skyhar MJ, Danzig LA, Camp J, Hargens AR, Akeson WH. Experimental models to promote healing of tears in the avascular segment of canine knee menisci. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(9):1363-1370.

7. Papachristou G, Efstathopoulos N, Plessas S, Levidiotis C, Chronopoulos E, Sourlas J. Isolated meniscal repair in the avascular area. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69(4):341-345.

8. Fox JM, Rintz KG, Ferkel RD. Trephination of incomplete meniscal tears. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(4):451-455.

9. Zhang Z, Arnold JA, Williams T, McCann B. Repairs by trephination and suturing of longitudinal injuries in the avascular area of the meniscus in goats. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):35-41.

10. Zhang ZN, Tu KY, Xu YK, Zhang WM, Liu ZT, Ou SH. Treatment of longitudinal injuries in avascular area of meniscus in dogs by trephination. Arthroscopy. 1988;4(3):151-159.

11. Ochi M, Uchio Y, Okuda K, Shu N, Yamaguchi H, Sakai Y. Expression of cytokines after meniscal rasping to promote meniscal healing. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(7):724-731.

12. Okuda K, Ochi M, Shu N, Uchio Y. Meniscal rasping for repair of meniscal tear in the avascular zone. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(3):281-286.

13. Uchio Y, Ochi M, Adachi N, Kawasaki K, Iwasa J. Results of rasping of meniscal tears with and without anterior cruciate ligament injury as evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):463-469.

14. Tasto JP, Cummings J, Medlock V, Harwood F, Hardesty R, Amiel D. The tendon treatment center: new horizons in the treatment of tendinosis. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(suppl 1):213-223.

15. Tasto JP. The role of radiofrequency-based devices in shaping the future of orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2006;29(10):874-875.

16. Tasto JP, Cummings J, Medlock V, Hardesty R, Amiel D. Microtenotomy using a radiofrequency probe to treat lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):851-860.

17. Higuchi H, Kimura M, Kobayashi A, Hatayama K, Takagishi K. A novel treatment of hypermobile lateral meniscus with monopolar radiofrequency energy. Arthroscopy 2004;20 (suppl 2):1-5.

18. Tonna EA, Cronkite EP. The periosteum. Autoradiographic studies on cellular proliferation and transformation utilizing tritiated thymidine. Clin Orthop. 1963;30:218-233.

19. Madewell BR. Serum thymidine kinase activity: an alternative to histologic markers of cellular proliferation in canine lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18(5):595-596.

20. Mujoomdar M, Bennett A, Hoskin D, Blay J. Adenosine stimulation of proliferation of breast carcinoma cell lines: evaluation of the [3H]thymidine assay system and modulatory effects of the cellular microenvironment in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201(3):429-438.

21. Vander Borght T, Labar D, Pauwels S, Lambotte L. Production of [2-11C]thymidine for quantification of cellular proliferation with PET. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1991;42(1):103-104.

22. Spindler KP, Mayes CE, Miller RR, Imro AK, Davidson JM. Regional mitogenic response of the meniscus to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-AB). J Orthop Res. 1995;13(2):201-207.

23. Thomopoulos S, Zaegel M, Das R, et al. PDGF-BB released in tendon repair using a novel delivery system promotes cell proliferation and collagen remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(10):1358-1368.

24. Pennock AT, Robertson CM, Emmerson BC, Harwood FL, Amiel D. Role of apoptotic and matrix-degrading genes in articular cartilage and meniscus of mature and aged rabbits during development of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1529-1536.

25. Allen RT, Tasto JP, Cummings J, Robertson CM, Amiel D. Meniscal debridement with an arthroscopic radiofrequency wand versus an arthroscopic shaver: comparative effects on menisci and underlying articular cartilage. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(4):385-393.

26. Figueroa D, Calvo R, Vaisman A, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency in the human meniscus. Comparative study between patients younger and older than 40 years of age. Knee. 2007;14(5):357-360.

27. Friedman M, LoSavio P, Ibrahim H, Ramakrishnan V. Radiofrequency tonsil reduction: safety, morbidity, and efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(5):882-887.

28. Hall DJ, Littlefield PD, Birkmire-Peters DP, Holtel MR. Radiofrequency ablation versus electrocautery in tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):300-305.

29. Kaplan H, Gat A. Clinical and histopathological results following TriPollar radiofrequency skin treatments. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11(2):78-84.

30. Mancini PF. Coblation: a new technology and technique for skin resurfacing and other aesthetic surgical procedures. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;2595):372-377.

31. Penka I, Kaplan Z, Sefr R, Sirotek L, Eber Z, Ondrák M. Use of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of malignant liver lesions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55(82-83):562-567.

32. Tasto JP, Ash SA. Current uses of radiofrequency in arthroscopic knee surgery. Am J Knee Surg. 1999;12(3):186-191.

33. Amiel D, Ball ST, Tasto JP. Chondrocyte viability and metabolic activity after treatment of bovine articular cartilage with bipolar radiofrequency: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):503-510.

34. Barry KJ, Kaplan J, Connolly RJ, et al. The effect of radiofrequency-generated thermal energy on the mechanical and histologic characteristics of the arterial wall in vivo: implications for radiofrequency angioplasty. Am Heart J. 1989;117(2):332-341.

35. Hoch DH, Grodzinsky AJ, Koob TJ, Albert ML, Eyre DR. Early changes in material properties of rabbit articular cartilage after meniscectomy. J Orthop Res. 1983;1(1):4-12.

36. Thompson AM, Stockwell RA. An ultrastructural study of the marginal transitional zone in the rabbit knee joint. J Anat. 1983;136(Pt 4):701-713.

Partial meniscectomy of tears in the avascular zone remains one of the most common orthopedic procedures. While results of partial meniscectomy in younger patients have excellent short- to medium-term results, the long-term clinical outcomes are often less favorable.1-3 Repair in the avascular “white-white” zone has resulted in lower patient satisfaction scores and higher revision surgery rates.4-7 Consequently, most tears in this region have been treated with partial meniscectomy.

The inability to repair rather than resect menisci with avascular tears has led to extensive research. Techniques such as trephination and rasping to initiate an angiogenic response have had inconsistent and unreliable results when applied to the white-white zone.8-13 In contrast, Tasto and colleagues14 have shown that radiofrequency (RF) applied to hypovascular tissue can not only stimulate tissue vascularity, but also increase organization of fibroblastic cells. In addition, Tasto and colleagues15,16 have shown that RF application can significantly improve histologic healing and clinical outcomes in refractory cases of Achilles tendinopathy and lateral epicondylitis. In Japanese white rabbit menisci, Higuchi and coauthors17 applied monopolar RF at 60°C and 40W to avascular zone tears to fuse the tissue. They found a significant increase in fibroblast proliferation and fusion of collagen fibers at 2, 4, and 12 weeks after surgery. They also found significant acellular zones of meniscus tissue and attributed these findings to fibrochondrocyte death because of thermal treatment.

This body of research led to the present study, which evaluates the effect of low-temperature, bipolar RF stimulation, in conjunction with suture repair, on the healing of tears in the avascular white-white zone of the meniscus both in vivo and ex vivo. We performed gross and histologic analyses of the treatment groups for the in vivo aspect of the study and biochemical analyses to study the ex vivo effects of RF treatment. 3H-thymidine incorporation has been shown to be a reliable indicator of cellular proliferation in several studies, and this was measured in our treatment groups.18-21 In addition, the response of mitogenic growth factors (IGF-1, bFGF) and angiogenic markers (VEGF, αV) to RF treatment was studied.22 We hypothesized that bipolar RF application would show increased gross, histologic, and biochemical healing when combined with suture repair of longitudinal avascular zone meniscus tears.

Materials and Methods

Creation of Meniscal Tears

Fifty-four healthy, skeletally mature male and female adult New Zealand white rabbits aged 7 to 18 months were used for the study. All procedures conformed to the guidelines of our university’s institutional animal care and use committee and the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All rabbits underwent a surgical procedure in which a longitudinal tear was created in the avascular white-white zone of the medial meniscus. Using sterile technique and instrumentation, a medial parapatellar incision was made on the left knee of each rabbit. The patella was retracted laterally, exposing the medial meniscus. The tibia was then externally rotated to sublux the anterior horn of the medial meniscus anteriorly. A longitudinal full-thickness meniscal tear (3-4 mm in length) was created in the avascular zone (inner third) of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus using an 11-blade scalpel (Figures 1A, 1B). The location of the tear was grossly performed in the same location in each meniscus. The rabbits were randomly divided into 3 treatment groups: 1, 2, and 3 (Table 1). Group 1 (n = 6) served as a control with no repair or RF treatment applied. Group 2 (n = 15) underwent suture repair only of the meniscal tear using 5-0 nylon suture in a horizontal mattress pattern (Figure 2A). Group 3 (n = 33) underwent suture repair after RF stimulation was applied to both sides of the meniscus tear (Figures 2B, 2C). RF was applied using a 0.8-mm TOPAZ MicroDebrider (ArthroCare, Sunnyvale, California) set at level 4 (175 V-RMS) for 500 milliseconds. Lactated ringer’s solution was continuously infused through the probe via sterile tubing to prevent overheating.

After meniscal treatment, hemostasis of the surrounding surgical dissection was achieved to prevent hematoma formation, and the wounds were irrigated. The patellae were relocated and the arthrotomies were closed with a running 2-0 vicryl suture. Fascial and subcutaneous layers were closed with a running 3-0 vicryl suture, and skin was closed with subcuticular 4‑0 vicryl sutures. The rabbit limbs were allowed weight-bearing with unrestricted range of motion within 2x2x2-ft cages.

For all groups, menisci were explanted at 28 and 84 days for gross and histologic analysis. For biochemical assessments, menisci were explanted at 9, 28, and 84 days (Table 1).

Gross Analysis

Immediately after specimen removal, all medial menisci were evaluated for gross morphology. A grading system was used for organization and classification of data (Table 2). Three blinded orthopedic surgeon-observers performed all grading. Grade A was considered complete healing of the meniscus. Grade B involved complete healing with a trace of injury remaining on the surface of the meniscus. Grade C represented incomplete healing with a full-thickness injury that was stable to stress of the repair site with an arthroscopic probe. Grade D had no healing with the injured region unstable to stress of the repair site with an arthroscopic probe.

Histologic Analysis and Microscopic Grading of Meniscal Healing

After gross evaluation by the 3 blinded observers, each meniscus was fixed for 24 hours in 10% buffered formalin. Each specimen was then embedded in paraffin and cut into 6-µm slices along the radial plane. The tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and microscopic grading was assigned. The grading system was the same as that used for gross morphologic analysis.

Biochemical Analysis

To determine whether RF treatment stimulated a healing response in the avascular zone of the meniscus, measurements of specific biochemical markers were analyzed at 9, 28, and 84 days after treatment. As a control, unrepaired meniscal tissue from the contralateral knee was also analyzed. 3H-thymidine incorporation into the meniscus was measured to assess cell proliferation.23 At sacrifice, control and treated menisci were dissected and immediately placed into sterile culture media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, antibiotic, and fungicide). 3H-thymidine was added at a concentration of 5µCi/mL of media to each tube. After incubation for 48 hours at 37°C under 5% CO2, the menisci were removed and dialyzed against water for 24 hours to remove unincorporated thymidine. After washing, the menisci were lyophilized, aliquots weighed, and radioactivity determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Results are expressed as counts per minute per mg dry tissue weight.

Semiquantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to determine mRNA expression of mitogenic growth factors, IGF-1 and bFGF, and angiogenic markers, αV and VEFG.24 National Institutes of Health (NIH) image-analysis software (version 1.61; NIH, Bethesda, Maryland) was used to quantitatively scan RT-PCR profiles after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide visualization. Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene, GAPDH.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean (SD) and evaluated using an unpaired Student t test between groups. Statistical significance was established at P < .05.

Results

Gross Morphology

Analysis of gross morphology showed signs of healing only in the group treated with suture repair combined with RF treatment (Table 3). In group 1 (meniscal injury only) and group 2 (suture repair only), no healing occurred at 28 and 84 days (Figure 3A). A meniscal grading system was developed to better describe the varying levels of healing shown in the suture-plus-RF-treatment group (Table 2). Of the specimens that showed healing in group 3, 1 had complete healing (grade A) within the avascular zone of the meniscus at 84 days (Figure 3B). In addition, 4 specimens subjected to suture repair and RF treatment had complete healing with only a trace of injured tissue remaining (grade B). Fourteen specimens in group 3 had incomplete healing with lesions stable to stress suggesting early signs of healing (grade C). In total, 58% of menisci treated with RF showed signs of healing while the remaining 14 specimens in group 3 showed none (grade D).

Histologic Examination

The histology correlated well with gross analysis. No microscopic evidence of healing was seen in groups 1 and 2 (Figure 3C). Of the specimens treated with suture repair combined with RF, 19 (58%) showed varying degrees of histologic healing. While gross morphologic examination showed that only 1 specimen had complete healing, microscopic analysis showed that 1 specimen from group 3 had grade B healing on gross analysis but grade A healing on histologic analysis. Thus, upon histologic examination, 2 specimens showed complete healing of injuries in the avascular zone of the meniscus when treated with suture repair combined with RF treatment rather than the 1 specimen seen on gross morphology (Figure 3D).

Biochemical Analysis

Biochemical assessments were performed at 9, 28, and 84 days after surgery. 3H-thymidine incorporation was studied as a marker for cellular proliferation, and its levels were significantly higher in meniscus explants treated with RF (Figure 4). The mean (SD) rate of incorporation for meniscal tears treated with suture repair plus RF was 590 (80) cpm/mg dry tissue at 9 days. This value was approximately 40% greater than the menisci treated with suture repair only, which had a mean (SD) value of 380 (30) cpm/mg (P < .05). Normal, unrepaired meniscal tissue had a mean (SD) 3H-thymidine incorporation rate of 250 (35) cpm/mg. By 84 days, thymidine levels returned to uninjured levels in both suture-only and RF-treated menisci. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that, 9 days after repair, the RF-treated menisci had increased mRNA expression of IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF, and αV relative to untreated repairs (Figure 5). There was a statistically significant acute phase response in IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF and αV in groups treated with RF at 9 days (P > .05).

Adverse Outcomes

There were no surgical complications. During the histologic evaluation, there were no incidences of fibrochondrocyte cell death or damage from the application of RF treatment.

Discussion

RF treatments have been used for many years in various medical and surgical applications. Presently, the most common implementation of RF is for cutting and coagulating tissue during surgery. More recently, however, several publications have shown that when used properly and safely, RF can be an effective surgical adjunct for tendinosis recalcitrant to conservative therapy.15-17,25-32

Many have suggested that RF coblation is successful in these clinical scenarios because of its ability to promote an increased angiogenic and fibroblastic response in hypovascular tissue.29,33,34

This body of literature led to the evaluation of RF coblation in treating meniscal tears in the avascular zone. Studies have shown poor success of meniscus repairs done in the avascular zone; however, our data demonstrate that supplementing suture repair with RF treatment may improve the acute-phase healing response. Although the control and suture-repair groups showed no signs of healing, the suture-repair-combined-with-RF-treatment group had 2 specimens in which complete gross and histologic healing occurred. In addition, 19 (58%) specimens in the RF group showed gross or histologic signs of healing.

Biochemically, 3H-thymidine incorporation was examined to assess cellular proliferation. Mitogenic (IGF, bFGF) and angiogenic (VEGF, αV) growth factors were measured as markers of an increased healing response. Compared with noninjured meniscal tissue, 3H-thymidine incorporation was significantly increased in both the suture and suture-combined-with-RF-treatment groups at 9 and 28 days after surgery. Between the suture and suture-RF groups, RF treatment led to a 40% greater increase in 3H-thymidine incorporation suggesting greater cellular proliferation in the immediate postoperative period. With respect to mitogenic and angiogenic factors, IGF, bFGF, VEGF, and αV were only significantly increased when RF was combined with suture repair. All 4 factors are important regulators of vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, wound healing, bone remodeling, and neurogenesis. The suture repair–only group showed no upregulation of these factors compared with uninjured controls.

Our study has several strengths. Using an animal model with menisci grossly similar to that of humans, we performed a controlled study comparing 2 treatment options, suture repair only and suture repair combined with RF treatment.35,36 The animal model also enabled second-look examinations at designated intervals. We analyzed the effect of RF treatment on concrete measures, such as gross, histologic, and biochemical healing. In particular, the biochemical analysis may indicate that RF treatment can increase the proliferative, mitogenic, and angiogenic capabilities of surrounding progenitor cells. This was evidenced by the statistically significant increase we saw in IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF, and αV at 9 and 28 days compared with controls.

Meniscal tears in the avascular zone represent a significant treatment dilemma for the physiologically young patient population. While partial meniscectomy provides excellent short-term relief, the long-term outcome of this intervention is degenerative joint disease. Meniscal repair in the central two-thirds of the meniscus has shown poor results. Our study presents data that show supplementing suture repair of avascular meniscal tears with RF can lead to increased gross, histologic, and biochemical healing in the New Zealand white rabbit. While these results are encouraging, studies with longer follow-up and specimens that represent the human menisci are necessary to determine whether these preliminary results would translate to human meniscal tears in the avascular zone.

Weaknesses of our study include the use of an animal model and the location of the tear created in the menisci. While using an animal model had many strengths, the results of our study are probably not strong enough to immediately extrapolate the use of RF in human meniscal repairs. However, the data we obtained are very encouraging and perhaps suggest that RF warrants human trials. Our open surgical technique made it difficult to create and repair a tear on the posterior horn of the medical meniscus without completely dislocating the knee anteriorly. As a result, the knees were subluxed anteriorly, and the meniscal tears and repairs were performed more anteriorly. The more anterior aspects of the menisci do not undergo the same rotational and axial loads as the posterior horn, and it is unclear whether this difference would contribute to the results we obtained from RF treatment. In addition, the tears were surgically created and the repair was done during the same procedure. Patients do not present in this manner, and this further underscores the need for a clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of this treatment option in humans.

Conclusion

RF-based supplementation of meniscal repairs in the avascular zone showed acute signs of biochemical healing in 58% of New Zealand white rabbit specimens. In addition, gross and histologic evaluations showed an increase in healing compared with controls. Two specimens treated with RF in combination with suture repair had complete healing. These results illustrate the effectiveness of RF in stimulating a healing response in hypovascular tissue. Clinical trials are necessary to determine the effectiveness of this treatment in humans.

Partial meniscectomy of tears in the avascular zone remains one of the most common orthopedic procedures. While results of partial meniscectomy in younger patients have excellent short- to medium-term results, the long-term clinical outcomes are often less favorable.1-3 Repair in the avascular “white-white” zone has resulted in lower patient satisfaction scores and higher revision surgery rates.4-7 Consequently, most tears in this region have been treated with partial meniscectomy.

The inability to repair rather than resect menisci with avascular tears has led to extensive research. Techniques such as trephination and rasping to initiate an angiogenic response have had inconsistent and unreliable results when applied to the white-white zone.8-13 In contrast, Tasto and colleagues14 have shown that radiofrequency (RF) applied to hypovascular tissue can not only stimulate tissue vascularity, but also increase organization of fibroblastic cells. In addition, Tasto and colleagues15,16 have shown that RF application can significantly improve histologic healing and clinical outcomes in refractory cases of Achilles tendinopathy and lateral epicondylitis. In Japanese white rabbit menisci, Higuchi and coauthors17 applied monopolar RF at 60°C and 40W to avascular zone tears to fuse the tissue. They found a significant increase in fibroblast proliferation and fusion of collagen fibers at 2, 4, and 12 weeks after surgery. They also found significant acellular zones of meniscus tissue and attributed these findings to fibrochondrocyte death because of thermal treatment.

This body of research led to the present study, which evaluates the effect of low-temperature, bipolar RF stimulation, in conjunction with suture repair, on the healing of tears in the avascular white-white zone of the meniscus both in vivo and ex vivo. We performed gross and histologic analyses of the treatment groups for the in vivo aspect of the study and biochemical analyses to study the ex vivo effects of RF treatment. 3H-thymidine incorporation has been shown to be a reliable indicator of cellular proliferation in several studies, and this was measured in our treatment groups.18-21 In addition, the response of mitogenic growth factors (IGF-1, bFGF) and angiogenic markers (VEGF, αV) to RF treatment was studied.22 We hypothesized that bipolar RF application would show increased gross, histologic, and biochemical healing when combined with suture repair of longitudinal avascular zone meniscus tears.

Materials and Methods

Creation of Meniscal Tears

Fifty-four healthy, skeletally mature male and female adult New Zealand white rabbits aged 7 to 18 months were used for the study. All procedures conformed to the guidelines of our university’s institutional animal care and use committee and the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All rabbits underwent a surgical procedure in which a longitudinal tear was created in the avascular white-white zone of the medial meniscus. Using sterile technique and instrumentation, a medial parapatellar incision was made on the left knee of each rabbit. The patella was retracted laterally, exposing the medial meniscus. The tibia was then externally rotated to sublux the anterior horn of the medial meniscus anteriorly. A longitudinal full-thickness meniscal tear (3-4 mm in length) was created in the avascular zone (inner third) of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus using an 11-blade scalpel (Figures 1A, 1B). The location of the tear was grossly performed in the same location in each meniscus. The rabbits were randomly divided into 3 treatment groups: 1, 2, and 3 (Table 1). Group 1 (n = 6) served as a control with no repair or RF treatment applied. Group 2 (n = 15) underwent suture repair only of the meniscal tear using 5-0 nylon suture in a horizontal mattress pattern (Figure 2A). Group 3 (n = 33) underwent suture repair after RF stimulation was applied to both sides of the meniscus tear (Figures 2B, 2C). RF was applied using a 0.8-mm TOPAZ MicroDebrider (ArthroCare, Sunnyvale, California) set at level 4 (175 V-RMS) for 500 milliseconds. Lactated ringer’s solution was continuously infused through the probe via sterile tubing to prevent overheating.

After meniscal treatment, hemostasis of the surrounding surgical dissection was achieved to prevent hematoma formation, and the wounds were irrigated. The patellae were relocated and the arthrotomies were closed with a running 2-0 vicryl suture. Fascial and subcutaneous layers were closed with a running 3-0 vicryl suture, and skin was closed with subcuticular 4‑0 vicryl sutures. The rabbit limbs were allowed weight-bearing with unrestricted range of motion within 2x2x2-ft cages.

For all groups, menisci were explanted at 28 and 84 days for gross and histologic analysis. For biochemical assessments, menisci were explanted at 9, 28, and 84 days (Table 1).

Gross Analysis

Immediately after specimen removal, all medial menisci were evaluated for gross morphology. A grading system was used for organization and classification of data (Table 2). Three blinded orthopedic surgeon-observers performed all grading. Grade A was considered complete healing of the meniscus. Grade B involved complete healing with a trace of injury remaining on the surface of the meniscus. Grade C represented incomplete healing with a full-thickness injury that was stable to stress of the repair site with an arthroscopic probe. Grade D had no healing with the injured region unstable to stress of the repair site with an arthroscopic probe.

Histologic Analysis and Microscopic Grading of Meniscal Healing

After gross evaluation by the 3 blinded observers, each meniscus was fixed for 24 hours in 10% buffered formalin. Each specimen was then embedded in paraffin and cut into 6-µm slices along the radial plane. The tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and microscopic grading was assigned. The grading system was the same as that used for gross morphologic analysis.

Biochemical Analysis

To determine whether RF treatment stimulated a healing response in the avascular zone of the meniscus, measurements of specific biochemical markers were analyzed at 9, 28, and 84 days after treatment. As a control, unrepaired meniscal tissue from the contralateral knee was also analyzed. 3H-thymidine incorporation into the meniscus was measured to assess cell proliferation.23 At sacrifice, control and treated menisci were dissected and immediately placed into sterile culture media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, antibiotic, and fungicide). 3H-thymidine was added at a concentration of 5µCi/mL of media to each tube. After incubation for 48 hours at 37°C under 5% CO2, the menisci were removed and dialyzed against water for 24 hours to remove unincorporated thymidine. After washing, the menisci were lyophilized, aliquots weighed, and radioactivity determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Results are expressed as counts per minute per mg dry tissue weight.

Semiquantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to determine mRNA expression of mitogenic growth factors, IGF-1 and bFGF, and angiogenic markers, αV and VEFG.24 National Institutes of Health (NIH) image-analysis software (version 1.61; NIH, Bethesda, Maryland) was used to quantitatively scan RT-PCR profiles after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide visualization. Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene, GAPDH.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean (SD) and evaluated using an unpaired Student t test between groups. Statistical significance was established at P < .05.

Results

Gross Morphology

Analysis of gross morphology showed signs of healing only in the group treated with suture repair combined with RF treatment (Table 3). In group 1 (meniscal injury only) and group 2 (suture repair only), no healing occurred at 28 and 84 days (Figure 3A). A meniscal grading system was developed to better describe the varying levels of healing shown in the suture-plus-RF-treatment group (Table 2). Of the specimens that showed healing in group 3, 1 had complete healing (grade A) within the avascular zone of the meniscus at 84 days (Figure 3B). In addition, 4 specimens subjected to suture repair and RF treatment had complete healing with only a trace of injured tissue remaining (grade B). Fourteen specimens in group 3 had incomplete healing with lesions stable to stress suggesting early signs of healing (grade C). In total, 58% of menisci treated with RF showed signs of healing while the remaining 14 specimens in group 3 showed none (grade D).

Histologic Examination

The histology correlated well with gross analysis. No microscopic evidence of healing was seen in groups 1 and 2 (Figure 3C). Of the specimens treated with suture repair combined with RF, 19 (58%) showed varying degrees of histologic healing. While gross morphologic examination showed that only 1 specimen had complete healing, microscopic analysis showed that 1 specimen from group 3 had grade B healing on gross analysis but grade A healing on histologic analysis. Thus, upon histologic examination, 2 specimens showed complete healing of injuries in the avascular zone of the meniscus when treated with suture repair combined with RF treatment rather than the 1 specimen seen on gross morphology (Figure 3D).

Biochemical Analysis

Biochemical assessments were performed at 9, 28, and 84 days after surgery. 3H-thymidine incorporation was studied as a marker for cellular proliferation, and its levels were significantly higher in meniscus explants treated with RF (Figure 4). The mean (SD) rate of incorporation for meniscal tears treated with suture repair plus RF was 590 (80) cpm/mg dry tissue at 9 days. This value was approximately 40% greater than the menisci treated with suture repair only, which had a mean (SD) value of 380 (30) cpm/mg (P < .05). Normal, unrepaired meniscal tissue had a mean (SD) 3H-thymidine incorporation rate of 250 (35) cpm/mg. By 84 days, thymidine levels returned to uninjured levels in both suture-only and RF-treated menisci. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that, 9 days after repair, the RF-treated menisci had increased mRNA expression of IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF, and αV relative to untreated repairs (Figure 5). There was a statistically significant acute phase response in IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF and αV in groups treated with RF at 9 days (P > .05).

Adverse Outcomes

There were no surgical complications. During the histologic evaluation, there were no incidences of fibrochondrocyte cell death or damage from the application of RF treatment.

Discussion

RF treatments have been used for many years in various medical and surgical applications. Presently, the most common implementation of RF is for cutting and coagulating tissue during surgery. More recently, however, several publications have shown that when used properly and safely, RF can be an effective surgical adjunct for tendinosis recalcitrant to conservative therapy.15-17,25-32

Many have suggested that RF coblation is successful in these clinical scenarios because of its ability to promote an increased angiogenic and fibroblastic response in hypovascular tissue.29,33,34

This body of literature led to the evaluation of RF coblation in treating meniscal tears in the avascular zone. Studies have shown poor success of meniscus repairs done in the avascular zone; however, our data demonstrate that supplementing suture repair with RF treatment may improve the acute-phase healing response. Although the control and suture-repair groups showed no signs of healing, the suture-repair-combined-with-RF-treatment group had 2 specimens in which complete gross and histologic healing occurred. In addition, 19 (58%) specimens in the RF group showed gross or histologic signs of healing.

Biochemically, 3H-thymidine incorporation was examined to assess cellular proliferation. Mitogenic (IGF, bFGF) and angiogenic (VEGF, αV) growth factors were measured as markers of an increased healing response. Compared with noninjured meniscal tissue, 3H-thymidine incorporation was significantly increased in both the suture and suture-combined-with-RF-treatment groups at 9 and 28 days after surgery. Between the suture and suture-RF groups, RF treatment led to a 40% greater increase in 3H-thymidine incorporation suggesting greater cellular proliferation in the immediate postoperative period. With respect to mitogenic and angiogenic factors, IGF, bFGF, VEGF, and αV were only significantly increased when RF was combined with suture repair. All 4 factors are important regulators of vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, wound healing, bone remodeling, and neurogenesis. The suture repair–only group showed no upregulation of these factors compared with uninjured controls.

Our study has several strengths. Using an animal model with menisci grossly similar to that of humans, we performed a controlled study comparing 2 treatment options, suture repair only and suture repair combined with RF treatment.35,36 The animal model also enabled second-look examinations at designated intervals. We analyzed the effect of RF treatment on concrete measures, such as gross, histologic, and biochemical healing. In particular, the biochemical analysis may indicate that RF treatment can increase the proliferative, mitogenic, and angiogenic capabilities of surrounding progenitor cells. This was evidenced by the statistically significant increase we saw in IGF-1, bFGF, VEGF, and αV at 9 and 28 days compared with controls.

Meniscal tears in the avascular zone represent a significant treatment dilemma for the physiologically young patient population. While partial meniscectomy provides excellent short-term relief, the long-term outcome of this intervention is degenerative joint disease. Meniscal repair in the central two-thirds of the meniscus has shown poor results. Our study presents data that show supplementing suture repair of avascular meniscal tears with RF can lead to increased gross, histologic, and biochemical healing in the New Zealand white rabbit. While these results are encouraging, studies with longer follow-up and specimens that represent the human menisci are necessary to determine whether these preliminary results would translate to human meniscal tears in the avascular zone.

Weaknesses of our study include the use of an animal model and the location of the tear created in the menisci. While using an animal model had many strengths, the results of our study are probably not strong enough to immediately extrapolate the use of RF in human meniscal repairs. However, the data we obtained are very encouraging and perhaps suggest that RF warrants human trials. Our open surgical technique made it difficult to create and repair a tear on the posterior horn of the medical meniscus without completely dislocating the knee anteriorly. As a result, the knees were subluxed anteriorly, and the meniscal tears and repairs were performed more anteriorly. The more anterior aspects of the menisci do not undergo the same rotational and axial loads as the posterior horn, and it is unclear whether this difference would contribute to the results we obtained from RF treatment. In addition, the tears were surgically created and the repair was done during the same procedure. Patients do not present in this manner, and this further underscores the need for a clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of this treatment option in humans.

Conclusion

RF-based supplementation of meniscal repairs in the avascular zone showed acute signs of biochemical healing in 58% of New Zealand white rabbit specimens. In addition, gross and histologic evaluations showed an increase in healing compared with controls. Two specimens treated with RF in combination with suture repair had complete healing. These results illustrate the effectiveness of RF in stimulating a healing response in hypovascular tissue. Clinical trials are necessary to determine the effectiveness of this treatment in humans.

1. Fauno P, Nielsen AB. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a long-term follow-up. Arthroscopy. 1992;8(3):345-349.

2. Lynch MA, Henning CE, Glick KR, Jr. Knee joint surface changes. Long-term follow-up meniscus tear treatment in stable anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Clin Orthop. 1983;172:148-153.

3. Roos H, Lauren M, Adalberth T, Roos EM, Jonsson K, Lohmander LS. Knee osteoarthritis after meniscectomy: prevalence of radiographic changes after twenty-one years, compared with matched controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(4):687-693.

4. Hennerbichler A, Moutos FT, Hennerbichler D, Weinberg JB, Guilak F. Repair response of the inner and outer regions of the porcine meniscus in vitro. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(5):754‑762.

5. Gershuni DH, Hargens AR, Danzig LA. Regional nutrition and cellularity of the meniscus. Implications for tear and repair. Sports Med. 1988;5(5):322-327.

6. Gershuni DH, Skyhar MJ, Danzig LA, Camp J, Hargens AR, Akeson WH. Experimental models to promote healing of tears in the avascular segment of canine knee menisci. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(9):1363-1370.

7. Papachristou G, Efstathopoulos N, Plessas S, Levidiotis C, Chronopoulos E, Sourlas J. Isolated meniscal repair in the avascular area. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69(4):341-345.

8. Fox JM, Rintz KG, Ferkel RD. Trephination of incomplete meniscal tears. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(4):451-455.

9. Zhang Z, Arnold JA, Williams T, McCann B. Repairs by trephination and suturing of longitudinal injuries in the avascular area of the meniscus in goats. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):35-41.

10. Zhang ZN, Tu KY, Xu YK, Zhang WM, Liu ZT, Ou SH. Treatment of longitudinal injuries in avascular area of meniscus in dogs by trephination. Arthroscopy. 1988;4(3):151-159.

11. Ochi M, Uchio Y, Okuda K, Shu N, Yamaguchi H, Sakai Y. Expression of cytokines after meniscal rasping to promote meniscal healing. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(7):724-731.

12. Okuda K, Ochi M, Shu N, Uchio Y. Meniscal rasping for repair of meniscal tear in the avascular zone. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(3):281-286.

13. Uchio Y, Ochi M, Adachi N, Kawasaki K, Iwasa J. Results of rasping of meniscal tears with and without anterior cruciate ligament injury as evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):463-469.

14. Tasto JP, Cummings J, Medlock V, Harwood F, Hardesty R, Amiel D. The tendon treatment center: new horizons in the treatment of tendinosis. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(suppl 1):213-223.

15. Tasto JP. The role of radiofrequency-based devices in shaping the future of orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2006;29(10):874-875.

16. Tasto JP, Cummings J, Medlock V, Hardesty R, Amiel D. Microtenotomy using a radiofrequency probe to treat lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):851-860.

17. Higuchi H, Kimura M, Kobayashi A, Hatayama K, Takagishi K. A novel treatment of hypermobile lateral meniscus with monopolar radiofrequency energy. Arthroscopy 2004;20 (suppl 2):1-5.

18. Tonna EA, Cronkite EP. The periosteum. Autoradiographic studies on cellular proliferation and transformation utilizing tritiated thymidine. Clin Orthop. 1963;30:218-233.

19. Madewell BR. Serum thymidine kinase activity: an alternative to histologic markers of cellular proliferation in canine lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18(5):595-596.

20. Mujoomdar M, Bennett A, Hoskin D, Blay J. Adenosine stimulation of proliferation of breast carcinoma cell lines: evaluation of the [3H]thymidine assay system and modulatory effects of the cellular microenvironment in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201(3):429-438.

21. Vander Borght T, Labar D, Pauwels S, Lambotte L. Production of [2-11C]thymidine for quantification of cellular proliferation with PET. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1991;42(1):103-104.

22. Spindler KP, Mayes CE, Miller RR, Imro AK, Davidson JM. Regional mitogenic response of the meniscus to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-AB). J Orthop Res. 1995;13(2):201-207.

23. Thomopoulos S, Zaegel M, Das R, et al. PDGF-BB released in tendon repair using a novel delivery system promotes cell proliferation and collagen remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(10):1358-1368.

24. Pennock AT, Robertson CM, Emmerson BC, Harwood FL, Amiel D. Role of apoptotic and matrix-degrading genes in articular cartilage and meniscus of mature and aged rabbits during development of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1529-1536.

25. Allen RT, Tasto JP, Cummings J, Robertson CM, Amiel D. Meniscal debridement with an arthroscopic radiofrequency wand versus an arthroscopic shaver: comparative effects on menisci and underlying articular cartilage. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(4):385-393.

26. Figueroa D, Calvo R, Vaisman A, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency in the human meniscus. Comparative study between patients younger and older than 40 years of age. Knee. 2007;14(5):357-360.

27. Friedman M, LoSavio P, Ibrahim H, Ramakrishnan V. Radiofrequency tonsil reduction: safety, morbidity, and efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(5):882-887.

28. Hall DJ, Littlefield PD, Birkmire-Peters DP, Holtel MR. Radiofrequency ablation versus electrocautery in tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):300-305.

29. Kaplan H, Gat A. Clinical and histopathological results following TriPollar radiofrequency skin treatments. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11(2):78-84.

30. Mancini PF. Coblation: a new technology and technique for skin resurfacing and other aesthetic surgical procedures. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;2595):372-377.

31. Penka I, Kaplan Z, Sefr R, Sirotek L, Eber Z, Ondrák M. Use of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of malignant liver lesions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55(82-83):562-567.

32. Tasto JP, Ash SA. Current uses of radiofrequency in arthroscopic knee surgery. Am J Knee Surg. 1999;12(3):186-191.

33. Amiel D, Ball ST, Tasto JP. Chondrocyte viability and metabolic activity after treatment of bovine articular cartilage with bipolar radiofrequency: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):503-510.

34. Barry KJ, Kaplan J, Connolly RJ, et al. The effect of radiofrequency-generated thermal energy on the mechanical and histologic characteristics of the arterial wall in vivo: implications for radiofrequency angioplasty. Am Heart J. 1989;117(2):332-341.

35. Hoch DH, Grodzinsky AJ, Koob TJ, Albert ML, Eyre DR. Early changes in material properties of rabbit articular cartilage after meniscectomy. J Orthop Res. 1983;1(1):4-12.

36. Thompson AM, Stockwell RA. An ultrastructural study of the marginal transitional zone in the rabbit knee joint. J Anat. 1983;136(Pt 4):701-713.

1. Fauno P, Nielsen AB. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a long-term follow-up. Arthroscopy. 1992;8(3):345-349.

2. Lynch MA, Henning CE, Glick KR, Jr. Knee joint surface changes. Long-term follow-up meniscus tear treatment in stable anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Clin Orthop. 1983;172:148-153.

3. Roos H, Lauren M, Adalberth T, Roos EM, Jonsson K, Lohmander LS. Knee osteoarthritis after meniscectomy: prevalence of radiographic changes after twenty-one years, compared with matched controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(4):687-693.

4. Hennerbichler A, Moutos FT, Hennerbichler D, Weinberg JB, Guilak F. Repair response of the inner and outer regions of the porcine meniscus in vitro. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(5):754‑762.

5. Gershuni DH, Hargens AR, Danzig LA. Regional nutrition and cellularity of the meniscus. Implications for tear and repair. Sports Med. 1988;5(5):322-327.

6. Gershuni DH, Skyhar MJ, Danzig LA, Camp J, Hargens AR, Akeson WH. Experimental models to promote healing of tears in the avascular segment of canine knee menisci. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(9):1363-1370.

7. Papachristou G, Efstathopoulos N, Plessas S, Levidiotis C, Chronopoulos E, Sourlas J. Isolated meniscal repair in the avascular area. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69(4):341-345.

8. Fox JM, Rintz KG, Ferkel RD. Trephination of incomplete meniscal tears. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(4):451-455.

9. Zhang Z, Arnold JA, Williams T, McCann B. Repairs by trephination and suturing of longitudinal injuries in the avascular area of the meniscus in goats. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):35-41.

10. Zhang ZN, Tu KY, Xu YK, Zhang WM, Liu ZT, Ou SH. Treatment of longitudinal injuries in avascular area of meniscus in dogs by trephination. Arthroscopy. 1988;4(3):151-159.

11. Ochi M, Uchio Y, Okuda K, Shu N, Yamaguchi H, Sakai Y. Expression of cytokines after meniscal rasping to promote meniscal healing. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(7):724-731.

12. Okuda K, Ochi M, Shu N, Uchio Y. Meniscal rasping for repair of meniscal tear in the avascular zone. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(3):281-286.

13. Uchio Y, Ochi M, Adachi N, Kawasaki K, Iwasa J. Results of rasping of meniscal tears with and without anterior cruciate ligament injury as evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):463-469.

14. Tasto JP, Cummings J, Medlock V, Harwood F, Hardesty R, Amiel D. The tendon treatment center: new horizons in the treatment of tendinosis. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(suppl 1):213-223.

15. Tasto JP. The role of radiofrequency-based devices in shaping the future of orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2006;29(10):874-875.

16. Tasto JP, Cummings J, Medlock V, Hardesty R, Amiel D. Microtenotomy using a radiofrequency probe to treat lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):851-860.

17. Higuchi H, Kimura M, Kobayashi A, Hatayama K, Takagishi K. A novel treatment of hypermobile lateral meniscus with monopolar radiofrequency energy. Arthroscopy 2004;20 (suppl 2):1-5.

18. Tonna EA, Cronkite EP. The periosteum. Autoradiographic studies on cellular proliferation and transformation utilizing tritiated thymidine. Clin Orthop. 1963;30:218-233.

19. Madewell BR. Serum thymidine kinase activity: an alternative to histologic markers of cellular proliferation in canine lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18(5):595-596.

20. Mujoomdar M, Bennett A, Hoskin D, Blay J. Adenosine stimulation of proliferation of breast carcinoma cell lines: evaluation of the [3H]thymidine assay system and modulatory effects of the cellular microenvironment in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201(3):429-438.

21. Vander Borght T, Labar D, Pauwels S, Lambotte L. Production of [2-11C]thymidine for quantification of cellular proliferation with PET. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1991;42(1):103-104.

22. Spindler KP, Mayes CE, Miller RR, Imro AK, Davidson JM. Regional mitogenic response of the meniscus to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-AB). J Orthop Res. 1995;13(2):201-207.

23. Thomopoulos S, Zaegel M, Das R, et al. PDGF-BB released in tendon repair using a novel delivery system promotes cell proliferation and collagen remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(10):1358-1368.

24. Pennock AT, Robertson CM, Emmerson BC, Harwood FL, Amiel D. Role of apoptotic and matrix-degrading genes in articular cartilage and meniscus of mature and aged rabbits during development of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1529-1536.

25. Allen RT, Tasto JP, Cummings J, Robertson CM, Amiel D. Meniscal debridement with an arthroscopic radiofrequency wand versus an arthroscopic shaver: comparative effects on menisci and underlying articular cartilage. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(4):385-393.

26. Figueroa D, Calvo R, Vaisman A, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency in the human meniscus. Comparative study between patients younger and older than 40 years of age. Knee. 2007;14(5):357-360.

27. Friedman M, LoSavio P, Ibrahim H, Ramakrishnan V. Radiofrequency tonsil reduction: safety, morbidity, and efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(5):882-887.

28. Hall DJ, Littlefield PD, Birkmire-Peters DP, Holtel MR. Radiofrequency ablation versus electrocautery in tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):300-305.

29. Kaplan H, Gat A. Clinical and histopathological results following TriPollar radiofrequency skin treatments. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11(2):78-84.

30. Mancini PF. Coblation: a new technology and technique for skin resurfacing and other aesthetic surgical procedures. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;2595):372-377.

31. Penka I, Kaplan Z, Sefr R, Sirotek L, Eber Z, Ondrák M. Use of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of malignant liver lesions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55(82-83):562-567.

32. Tasto JP, Ash SA. Current uses of radiofrequency in arthroscopic knee surgery. Am J Knee Surg. 1999;12(3):186-191.

33. Amiel D, Ball ST, Tasto JP. Chondrocyte viability and metabolic activity after treatment of bovine articular cartilage with bipolar radiofrequency: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):503-510.

34. Barry KJ, Kaplan J, Connolly RJ, et al. The effect of radiofrequency-generated thermal energy on the mechanical and histologic characteristics of the arterial wall in vivo: implications for radiofrequency angioplasty. Am Heart J. 1989;117(2):332-341.

35. Hoch DH, Grodzinsky AJ, Koob TJ, Albert ML, Eyre DR. Early changes in material properties of rabbit articular cartilage after meniscectomy. J Orthop Res. 1983;1(1):4-12.

36. Thompson AM, Stockwell RA. An ultrastructural study of the marginal transitional zone in the rabbit knee joint. J Anat. 1983;136(Pt 4):701-713.