User login

People with serious mental illness (SMI) have a life expectancy that is 25 years less than the general population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 This disparity is partially a consequence of the lack of primary and preventive medical care for those with psychiatric illness. Decades of research have shown that people with SMI experience higher medical morbidity and mortality in addition to facing the stigma of mental illness.

This article aims to advance the idea that longitudinal “cross education” between primary care providers (PCPs) and behavioral health providers (BHPs) is essential in addressing this problem. BHPs include psychiatry clinics, which often are part of a university or large health systems; county-based community mental health programs; and independent mental health clinics that contract with public and private health plans to provide mental health services.

Although suicide and injury account for 40% of the excess mortality in schizophrenia, 60% can be attributed to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and infection.2 Patients with SMI have 2 to 3 times the risk of diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.3,4 Furthermore, those with SMI consume more than one-third of tobacco products,5 and 50% to 80% of people with SMI smoke tobacco, an important reversible risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

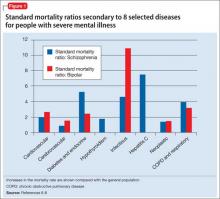

Figure 1 shows that people with SMI are at higher risk of dying from a chronic medical condition, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hepatitis C6-8—many of which can be managed by primary and preventive medical interventions. These and other conditions often are not diagnosed or effectively managed in patients with SMI.

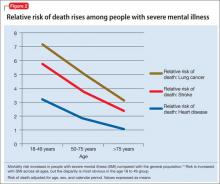

The high prevalence of metabolic syndrome and tobacco dependence among people with SMI accelerates development of cardiovascular disease, as shown by several studies. Bobes et al9 found that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk among patients with SMI is similar to what is found in the general population at 10 to 15 years of greater age. Osborn et al10 demonstrated that people with SMI age 18 to 49 had a higher relative risk of death from coronary heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer than age-matched controls (Figure 2).

It can be said, therefore, that patients with SMI seem to “age” and die prematurely. To reduce this disparity, primary and preventive medical care—especially for cardiovascular disease—must be delivered earlier in life for those with SMI.

Iatrogenic causes of morbidity

Many psychiatric medications, especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), could exacerbate cardiovascular and metabolic conditions by increasing the risk of weight gain, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia. Antipsychotics that generally are considered to be more effective for refractory psychotic illness (eg, clozapine and olanzapine) are associated with the highest risk of metabolic syndrome. Simon et al11 found a dose-response relationship between olanzapine and clozapine serum concentrations and worsening metabolic outcomes. Valproic acid also can cause significant weight gain and could require monitoring similar to what is done with to SGAs, although there has been less clinical and research attention to this mood stabilizer.

The American Diabetes Association et al12 have published guidelines on monitoring antipsychotic-induced obesity and diabetes, but adoption of these guidelines has been slow. Mackin et al13 found that providers are slow to recognize the elevated rate of obesity and dyslipidemia among psychiatric patients, possibly because of “an alarmingly poor rate of monitoring of metabolic parameters.”

Treating adverse metabolic outcomes also seems to lag behind. The same study13 found that physical health parameters among psychiatric patients continue to become worse even when appropriate health care professionals were notified. Rates of nontreatment for diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were 30%, 60%, and 88% respectively, according to Nasrallah et al.14

Randomized controlled studies have shown that obesity and metabolic syndrome can be effectively managed using lifestyle and pharmacotherapeutic approaches,15,16 but more research is needed to test long-term outcomes and how to best incorporate these interventions. Newcomer et al17 found that gradually switching an antipsychotic with high risk of metabolic adverse effects to one with lower risk could reduce adverse metabolic outcomes; however, some patients returned to their prior antipsychotic because other medications did not effectively treat their schizophrenia symptoms. Therefore, physicians must pay careful attention to the trade-off between benefits and risks of antipsychotics and make treatment decisions on an individual basis.

Barriers to medical care

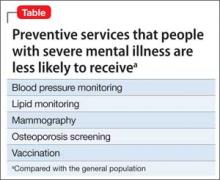

Research has demonstrated that patients with SMI receive less screening and fewer preventive medical services, especially blood pressure monitoring, vaccinations, mammography, lipid monitoring, and osteoporosis screening, compared with the general population (Table).18 Some barriers to preventive services could exist because of demographic factors and medical insurance coverage19 or medical providers’ discomfort with symptoms of SMI,20 although Mitchell et al21 found that disparities in mammography screening could not be explained by the presence of emotional distress in women with SMI.

DiMatteo et al22 reported that patients with SMI are 3 times more likely to be noncompliant with medical treatment. These patients also are less likely to receive sec ondary preventive medical care and invasive medical procedures. Those with SMI who experience acute myocardial infarction are less likely to receive drug therapy, such as a thrombolytic, aspirin, beta blocker, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.23 They also are less likely to receive invasive cardiovascular procedures, including cardiac catheterization, angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass grafting.24

Therefore, not only are patients with SMI less likely to receive preventive care, they are also less likely to receive potentially lifesaving treatments for SMI. Because those with SMI might not be able to advocate for themselves in these matters, psychiatric clinicians can improve their patients’ lives by advocating for appropriate medical care despite multiple barriers.

Bridging the gap: Managing mental health in primary care

Research from the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated that most persons who sought help for depression or anxiety received treatment from their PCP, many of whom felt limited by their lack of behavioral health training. Moreover, many patients failed to receive a psychiatric diagnosis or adequate treatment, despite efforts to educate primary care physicians on appropriate diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.

Katon et al25 at the University of Washington developed the collaborative care model in the early 1990s to help improve treatment of depression in primary care settings. This model involved:

• case load review by psychiatrists

• use of nurses and other support staff to help monitor patients’ adherence and treatment response

• use of standardized tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire to monitor symptoms

• enhancement of patient education with pamphlets or classes.

Studies evaluating the success of collaborative care models found overall improved outcomes, making it the only evidence-based model for integration of behavioral health and primary care.26 As a result, the collaborative care model has been implemented across the United States in primary care clinics and specialty care settings, such as obstetrics and gynecology.27

Regrettably, access to primary care has been hampered by:

• population growth

• a shortage of PCPs

• enrollment of a flood of new patients into the health care marketplace as a result of mandates of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

In many settings, a psychiatrist might be the patient’s only consistent care provider, and could be thought of as a “primary care psychiatrist.”

To resolve this predicament, mental health professionals need to recognize the unique medical conditions faced by people with SMI, and also might need to provide treatment of common medical conditions, either directly or through collaborative arrangements. Psychiatrists who are capable of managing core medical issues likely will witness improved psychiatric and overall health outcomes in their patients. Consequently, psychiatrists and mental health professionals are increasingly called on to be advocates to improve access to medical services in patients with SMI and to participate in health systems reform.

Managing medical conditions in mental health settings

Although traditional collaborative care involves mental health providers working at primary care sites, other models have emerged that manage chronic disease in behavioral health settings. Federally funded grants for primary behavioral health care integration have allowed community mental health centers to partner with federally qualified health centers to provide on-site primary care services.28

In these models, care managers in mental health clinics:

• link patients to primary care services

• encourage lifestyle changes to improve their overall health

• identify and overcome barriers to receiving care

• track clinical outcomes in a registry format.

Currently, 126 mental health sites in the United States have received these grants and are working toward greater integration of primary care.

In addition, the ACA provided funding for “health homes” in non-primary care settings, which includes SMI. These health homes cannot provide direct primary care, but can deliver comprehensive care management, care coordination, health promotion, comprehensive transitional care services between facilities, individual and family support, and referral to community social support services. In these health homes, a PCP can act as a consultant to help establish priorities for disease management and improving health status.29 The PCP consultant also can support psychiatric staff and collaborate with providers who want to provide some direct care of medical conditions.30

Last, some behavioral health sites are choosing to apply for Federally Qualified Health Clinic status or add primary care services to their clinics, with the hope that sustainable funding will become available. Without additional funding to cover the limited reimbursement provided by public payers, such as Medicaid and Medicare, these models might be unsustainable. Current innovations in health care funding reform hopefully will offer solutions for sites to provide medical care in the natural “medical home” of the SMI population.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric providers are in a favorable position to develop and oversee a partnership with primary care physicians with the goal of addressing significant and often lethal health disparities among those with mental illness. Psychiatric providers must use evidence-based practices that include assessment and prevention of cardiopulmonary, metabolic, infectious, and oncologic disorders. True primary care–behavioral health integration must include longitudinal “cross education” and changes in health care policy, with an emphasis on decreasing morbidity and mortality in psychiatric patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al, eds. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council; 2006.

3. Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1794-1796.

4. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trails of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):19-32.

5. Compton MT, Daumit GL, Druss BG. Cigarette smoking and overweight/obesity among individuals with serious mental illnesses: a preventive perspective. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):212-222.

6. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123-1131.

7. Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon W. Premature mortality from general medical illnesses among persons with bipolar disorder: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):147-156.

8. Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: a population-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(11):1133-1137.

9. Bobes J, Arango C, Aranda P, et al; CLAMORS Study Collaborative Group. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk in outpatients with schizoaffective disorder treated with antipsychotics; results from the CLAMORS study. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(4):267-274.

10. Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, et al. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database [Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(6):736]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):242-249.

11. Simon V, van Winkel R, De Hert M. Are weight gain and metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics dose dependent? A literature review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(7):1041-1050.

12. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

13. Mackin P, Bishop DR, Watkinson HM. A prospective study of monitoring practices for metabolic disease in antipsychotic-treated community psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:28.

14. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

15. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Hetrick SE, González-Blanch C, et al. Non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2008; 193(2):101-107.

16. Maayan L, Vakhrusheva J, Correll CU. Effectiveness of medication used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(7):1520-1530.

17. Newcomer JW, Weiden PJ, Buchanan RW. Switching antipsychotic medications to reduce adverse event burden in schizophrenia: establishing evidence-based practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):1108-1120.

18. Lord O, Malone D, Mitchell AJ. Receipt of preventive medical care and medical screening for patients with mental illness: a comparative analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):519-543.

19. Xiong GL, Iosif AM, Bermudes RA, et al. Preventive medical services use among community mental health patients with severe mental illness: the influence of gender and insurance coverage. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(5). doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00927gre.

20. Daub S. Turning toward treating the seriously mentally ill in primary care. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(1):12-13.

21. Mitchell A, Pereira IE, Yadegarfar M, et al. Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness: comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):428-435.

22. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107.

23. Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):565-572.

24. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283(4):506-511.

25. Katon W, Unützer J, Wells K, et al. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):456-464.

26. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

27. Katon W, Russo J, Reed SD, et al. A randomized trial of collaborative depression care in obstetrics and gynecology clinics: socioeconomic disadvantage and treatment response. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):32-40.

28. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Request for Applications (RFA) No. SM- 09-011. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009.

29. Parks J. Behavioral health homes. In: Integrated care: working at the interface of primary care and behavioral health. Raney LE, ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:195.

30. Raney L. Integrated care: the evolving role of psychiatry in the era of health care reform. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(11):1076-1078.

People with serious mental illness (SMI) have a life expectancy that is 25 years less than the general population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 This disparity is partially a consequence of the lack of primary and preventive medical care for those with psychiatric illness. Decades of research have shown that people with SMI experience higher medical morbidity and mortality in addition to facing the stigma of mental illness.

This article aims to advance the idea that longitudinal “cross education” between primary care providers (PCPs) and behavioral health providers (BHPs) is essential in addressing this problem. BHPs include psychiatry clinics, which often are part of a university or large health systems; county-based community mental health programs; and independent mental health clinics that contract with public and private health plans to provide mental health services.

Although suicide and injury account for 40% of the excess mortality in schizophrenia, 60% can be attributed to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and infection.2 Patients with SMI have 2 to 3 times the risk of diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.3,4 Furthermore, those with SMI consume more than one-third of tobacco products,5 and 50% to 80% of people with SMI smoke tobacco, an important reversible risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1 shows that people with SMI are at higher risk of dying from a chronic medical condition, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hepatitis C6-8—many of which can be managed by primary and preventive medical interventions. These and other conditions often are not diagnosed or effectively managed in patients with SMI.

The high prevalence of metabolic syndrome and tobacco dependence among people with SMI accelerates development of cardiovascular disease, as shown by several studies. Bobes et al9 found that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk among patients with SMI is similar to what is found in the general population at 10 to 15 years of greater age. Osborn et al10 demonstrated that people with SMI age 18 to 49 had a higher relative risk of death from coronary heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer than age-matched controls (Figure 2).

It can be said, therefore, that patients with SMI seem to “age” and die prematurely. To reduce this disparity, primary and preventive medical care—especially for cardiovascular disease—must be delivered earlier in life for those with SMI.

Iatrogenic causes of morbidity

Many psychiatric medications, especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), could exacerbate cardiovascular and metabolic conditions by increasing the risk of weight gain, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia. Antipsychotics that generally are considered to be more effective for refractory psychotic illness (eg, clozapine and olanzapine) are associated with the highest risk of metabolic syndrome. Simon et al11 found a dose-response relationship between olanzapine and clozapine serum concentrations and worsening metabolic outcomes. Valproic acid also can cause significant weight gain and could require monitoring similar to what is done with to SGAs, although there has been less clinical and research attention to this mood stabilizer.

The American Diabetes Association et al12 have published guidelines on monitoring antipsychotic-induced obesity and diabetes, but adoption of these guidelines has been slow. Mackin et al13 found that providers are slow to recognize the elevated rate of obesity and dyslipidemia among psychiatric patients, possibly because of “an alarmingly poor rate of monitoring of metabolic parameters.”

Treating adverse metabolic outcomes also seems to lag behind. The same study13 found that physical health parameters among psychiatric patients continue to become worse even when appropriate health care professionals were notified. Rates of nontreatment for diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were 30%, 60%, and 88% respectively, according to Nasrallah et al.14

Randomized controlled studies have shown that obesity and metabolic syndrome can be effectively managed using lifestyle and pharmacotherapeutic approaches,15,16 but more research is needed to test long-term outcomes and how to best incorporate these interventions. Newcomer et al17 found that gradually switching an antipsychotic with high risk of metabolic adverse effects to one with lower risk could reduce adverse metabolic outcomes; however, some patients returned to their prior antipsychotic because other medications did not effectively treat their schizophrenia symptoms. Therefore, physicians must pay careful attention to the trade-off between benefits and risks of antipsychotics and make treatment decisions on an individual basis.

Barriers to medical care

Research has demonstrated that patients with SMI receive less screening and fewer preventive medical services, especially blood pressure monitoring, vaccinations, mammography, lipid monitoring, and osteoporosis screening, compared with the general population (Table).18 Some barriers to preventive services could exist because of demographic factors and medical insurance coverage19 or medical providers’ discomfort with symptoms of SMI,20 although Mitchell et al21 found that disparities in mammography screening could not be explained by the presence of emotional distress in women with SMI.

DiMatteo et al22 reported that patients with SMI are 3 times more likely to be noncompliant with medical treatment. These patients also are less likely to receive sec ondary preventive medical care and invasive medical procedures. Those with SMI who experience acute myocardial infarction are less likely to receive drug therapy, such as a thrombolytic, aspirin, beta blocker, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.23 They also are less likely to receive invasive cardiovascular procedures, including cardiac catheterization, angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass grafting.24

Therefore, not only are patients with SMI less likely to receive preventive care, they are also less likely to receive potentially lifesaving treatments for SMI. Because those with SMI might not be able to advocate for themselves in these matters, psychiatric clinicians can improve their patients’ lives by advocating for appropriate medical care despite multiple barriers.

Bridging the gap: Managing mental health in primary care

Research from the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated that most persons who sought help for depression or anxiety received treatment from their PCP, many of whom felt limited by their lack of behavioral health training. Moreover, many patients failed to receive a psychiatric diagnosis or adequate treatment, despite efforts to educate primary care physicians on appropriate diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.

Katon et al25 at the University of Washington developed the collaborative care model in the early 1990s to help improve treatment of depression in primary care settings. This model involved:

• case load review by psychiatrists

• use of nurses and other support staff to help monitor patients’ adherence and treatment response

• use of standardized tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire to monitor symptoms

• enhancement of patient education with pamphlets or classes.

Studies evaluating the success of collaborative care models found overall improved outcomes, making it the only evidence-based model for integration of behavioral health and primary care.26 As a result, the collaborative care model has been implemented across the United States in primary care clinics and specialty care settings, such as obstetrics and gynecology.27

Regrettably, access to primary care has been hampered by:

• population growth

• a shortage of PCPs

• enrollment of a flood of new patients into the health care marketplace as a result of mandates of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

In many settings, a psychiatrist might be the patient’s only consistent care provider, and could be thought of as a “primary care psychiatrist.”

To resolve this predicament, mental health professionals need to recognize the unique medical conditions faced by people with SMI, and also might need to provide treatment of common medical conditions, either directly or through collaborative arrangements. Psychiatrists who are capable of managing core medical issues likely will witness improved psychiatric and overall health outcomes in their patients. Consequently, psychiatrists and mental health professionals are increasingly called on to be advocates to improve access to medical services in patients with SMI and to participate in health systems reform.

Managing medical conditions in mental health settings

Although traditional collaborative care involves mental health providers working at primary care sites, other models have emerged that manage chronic disease in behavioral health settings. Federally funded grants for primary behavioral health care integration have allowed community mental health centers to partner with federally qualified health centers to provide on-site primary care services.28

In these models, care managers in mental health clinics:

• link patients to primary care services

• encourage lifestyle changes to improve their overall health

• identify and overcome barriers to receiving care

• track clinical outcomes in a registry format.

Currently, 126 mental health sites in the United States have received these grants and are working toward greater integration of primary care.

In addition, the ACA provided funding for “health homes” in non-primary care settings, which includes SMI. These health homes cannot provide direct primary care, but can deliver comprehensive care management, care coordination, health promotion, comprehensive transitional care services between facilities, individual and family support, and referral to community social support services. In these health homes, a PCP can act as a consultant to help establish priorities for disease management and improving health status.29 The PCP consultant also can support psychiatric staff and collaborate with providers who want to provide some direct care of medical conditions.30

Last, some behavioral health sites are choosing to apply for Federally Qualified Health Clinic status or add primary care services to their clinics, with the hope that sustainable funding will become available. Without additional funding to cover the limited reimbursement provided by public payers, such as Medicaid and Medicare, these models might be unsustainable. Current innovations in health care funding reform hopefully will offer solutions for sites to provide medical care in the natural “medical home” of the SMI population.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric providers are in a favorable position to develop and oversee a partnership with primary care physicians with the goal of addressing significant and often lethal health disparities among those with mental illness. Psychiatric providers must use evidence-based practices that include assessment and prevention of cardiopulmonary, metabolic, infectious, and oncologic disorders. True primary care–behavioral health integration must include longitudinal “cross education” and changes in health care policy, with an emphasis on decreasing morbidity and mortality in psychiatric patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

People with serious mental illness (SMI) have a life expectancy that is 25 years less than the general population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 This disparity is partially a consequence of the lack of primary and preventive medical care for those with psychiatric illness. Decades of research have shown that people with SMI experience higher medical morbidity and mortality in addition to facing the stigma of mental illness.

This article aims to advance the idea that longitudinal “cross education” between primary care providers (PCPs) and behavioral health providers (BHPs) is essential in addressing this problem. BHPs include psychiatry clinics, which often are part of a university or large health systems; county-based community mental health programs; and independent mental health clinics that contract with public and private health plans to provide mental health services.

Although suicide and injury account for 40% of the excess mortality in schizophrenia, 60% can be attributed to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and infection.2 Patients with SMI have 2 to 3 times the risk of diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.3,4 Furthermore, those with SMI consume more than one-third of tobacco products,5 and 50% to 80% of people with SMI smoke tobacco, an important reversible risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1 shows that people with SMI are at higher risk of dying from a chronic medical condition, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hepatitis C6-8—many of which can be managed by primary and preventive medical interventions. These and other conditions often are not diagnosed or effectively managed in patients with SMI.

The high prevalence of metabolic syndrome and tobacco dependence among people with SMI accelerates development of cardiovascular disease, as shown by several studies. Bobes et al9 found that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk among patients with SMI is similar to what is found in the general population at 10 to 15 years of greater age. Osborn et al10 demonstrated that people with SMI age 18 to 49 had a higher relative risk of death from coronary heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer than age-matched controls (Figure 2).

It can be said, therefore, that patients with SMI seem to “age” and die prematurely. To reduce this disparity, primary and preventive medical care—especially for cardiovascular disease—must be delivered earlier in life for those with SMI.

Iatrogenic causes of morbidity

Many psychiatric medications, especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), could exacerbate cardiovascular and metabolic conditions by increasing the risk of weight gain, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia. Antipsychotics that generally are considered to be more effective for refractory psychotic illness (eg, clozapine and olanzapine) are associated with the highest risk of metabolic syndrome. Simon et al11 found a dose-response relationship between olanzapine and clozapine serum concentrations and worsening metabolic outcomes. Valproic acid also can cause significant weight gain and could require monitoring similar to what is done with to SGAs, although there has been less clinical and research attention to this mood stabilizer.

The American Diabetes Association et al12 have published guidelines on monitoring antipsychotic-induced obesity and diabetes, but adoption of these guidelines has been slow. Mackin et al13 found that providers are slow to recognize the elevated rate of obesity and dyslipidemia among psychiatric patients, possibly because of “an alarmingly poor rate of monitoring of metabolic parameters.”

Treating adverse metabolic outcomes also seems to lag behind. The same study13 found that physical health parameters among psychiatric patients continue to become worse even when appropriate health care professionals were notified. Rates of nontreatment for diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were 30%, 60%, and 88% respectively, according to Nasrallah et al.14

Randomized controlled studies have shown that obesity and metabolic syndrome can be effectively managed using lifestyle and pharmacotherapeutic approaches,15,16 but more research is needed to test long-term outcomes and how to best incorporate these interventions. Newcomer et al17 found that gradually switching an antipsychotic with high risk of metabolic adverse effects to one with lower risk could reduce adverse metabolic outcomes; however, some patients returned to their prior antipsychotic because other medications did not effectively treat their schizophrenia symptoms. Therefore, physicians must pay careful attention to the trade-off between benefits and risks of antipsychotics and make treatment decisions on an individual basis.

Barriers to medical care

Research has demonstrated that patients with SMI receive less screening and fewer preventive medical services, especially blood pressure monitoring, vaccinations, mammography, lipid monitoring, and osteoporosis screening, compared with the general population (Table).18 Some barriers to preventive services could exist because of demographic factors and medical insurance coverage19 or medical providers’ discomfort with symptoms of SMI,20 although Mitchell et al21 found that disparities in mammography screening could not be explained by the presence of emotional distress in women with SMI.

DiMatteo et al22 reported that patients with SMI are 3 times more likely to be noncompliant with medical treatment. These patients also are less likely to receive sec ondary preventive medical care and invasive medical procedures. Those with SMI who experience acute myocardial infarction are less likely to receive drug therapy, such as a thrombolytic, aspirin, beta blocker, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.23 They also are less likely to receive invasive cardiovascular procedures, including cardiac catheterization, angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass grafting.24

Therefore, not only are patients with SMI less likely to receive preventive care, they are also less likely to receive potentially lifesaving treatments for SMI. Because those with SMI might not be able to advocate for themselves in these matters, psychiatric clinicians can improve their patients’ lives by advocating for appropriate medical care despite multiple barriers.

Bridging the gap: Managing mental health in primary care

Research from the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated that most persons who sought help for depression or anxiety received treatment from their PCP, many of whom felt limited by their lack of behavioral health training. Moreover, many patients failed to receive a psychiatric diagnosis or adequate treatment, despite efforts to educate primary care physicians on appropriate diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.

Katon et al25 at the University of Washington developed the collaborative care model in the early 1990s to help improve treatment of depression in primary care settings. This model involved:

• case load review by psychiatrists

• use of nurses and other support staff to help monitor patients’ adherence and treatment response

• use of standardized tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire to monitor symptoms

• enhancement of patient education with pamphlets or classes.

Studies evaluating the success of collaborative care models found overall improved outcomes, making it the only evidence-based model for integration of behavioral health and primary care.26 As a result, the collaborative care model has been implemented across the United States in primary care clinics and specialty care settings, such as obstetrics and gynecology.27

Regrettably, access to primary care has been hampered by:

• population growth

• a shortage of PCPs

• enrollment of a flood of new patients into the health care marketplace as a result of mandates of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

In many settings, a psychiatrist might be the patient’s only consistent care provider, and could be thought of as a “primary care psychiatrist.”

To resolve this predicament, mental health professionals need to recognize the unique medical conditions faced by people with SMI, and also might need to provide treatment of common medical conditions, either directly or through collaborative arrangements. Psychiatrists who are capable of managing core medical issues likely will witness improved psychiatric and overall health outcomes in their patients. Consequently, psychiatrists and mental health professionals are increasingly called on to be advocates to improve access to medical services in patients with SMI and to participate in health systems reform.

Managing medical conditions in mental health settings

Although traditional collaborative care involves mental health providers working at primary care sites, other models have emerged that manage chronic disease in behavioral health settings. Federally funded grants for primary behavioral health care integration have allowed community mental health centers to partner with federally qualified health centers to provide on-site primary care services.28

In these models, care managers in mental health clinics:

• link patients to primary care services

• encourage lifestyle changes to improve their overall health

• identify and overcome barriers to receiving care

• track clinical outcomes in a registry format.

Currently, 126 mental health sites in the United States have received these grants and are working toward greater integration of primary care.

In addition, the ACA provided funding for “health homes” in non-primary care settings, which includes SMI. These health homes cannot provide direct primary care, but can deliver comprehensive care management, care coordination, health promotion, comprehensive transitional care services between facilities, individual and family support, and referral to community social support services. In these health homes, a PCP can act as a consultant to help establish priorities for disease management and improving health status.29 The PCP consultant also can support psychiatric staff and collaborate with providers who want to provide some direct care of medical conditions.30

Last, some behavioral health sites are choosing to apply for Federally Qualified Health Clinic status or add primary care services to their clinics, with the hope that sustainable funding will become available. Without additional funding to cover the limited reimbursement provided by public payers, such as Medicaid and Medicare, these models might be unsustainable. Current innovations in health care funding reform hopefully will offer solutions for sites to provide medical care in the natural “medical home” of the SMI population.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric providers are in a favorable position to develop and oversee a partnership with primary care physicians with the goal of addressing significant and often lethal health disparities among those with mental illness. Psychiatric providers must use evidence-based practices that include assessment and prevention of cardiopulmonary, metabolic, infectious, and oncologic disorders. True primary care–behavioral health integration must include longitudinal “cross education” and changes in health care policy, with an emphasis on decreasing morbidity and mortality in psychiatric patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al, eds. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council; 2006.

3. Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1794-1796.

4. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trails of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):19-32.

5. Compton MT, Daumit GL, Druss BG. Cigarette smoking and overweight/obesity among individuals with serious mental illnesses: a preventive perspective. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):212-222.

6. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123-1131.

7. Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon W. Premature mortality from general medical illnesses among persons with bipolar disorder: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):147-156.

8. Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: a population-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(11):1133-1137.

9. Bobes J, Arango C, Aranda P, et al; CLAMORS Study Collaborative Group. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk in outpatients with schizoaffective disorder treated with antipsychotics; results from the CLAMORS study. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(4):267-274.

10. Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, et al. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database [Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(6):736]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):242-249.

11. Simon V, van Winkel R, De Hert M. Are weight gain and metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics dose dependent? A literature review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(7):1041-1050.

12. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

13. Mackin P, Bishop DR, Watkinson HM. A prospective study of monitoring practices for metabolic disease in antipsychotic-treated community psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:28.

14. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

15. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Hetrick SE, González-Blanch C, et al. Non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2008; 193(2):101-107.

16. Maayan L, Vakhrusheva J, Correll CU. Effectiveness of medication used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(7):1520-1530.

17. Newcomer JW, Weiden PJ, Buchanan RW. Switching antipsychotic medications to reduce adverse event burden in schizophrenia: establishing evidence-based practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):1108-1120.

18. Lord O, Malone D, Mitchell AJ. Receipt of preventive medical care and medical screening for patients with mental illness: a comparative analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):519-543.

19. Xiong GL, Iosif AM, Bermudes RA, et al. Preventive medical services use among community mental health patients with severe mental illness: the influence of gender and insurance coverage. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(5). doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00927gre.

20. Daub S. Turning toward treating the seriously mentally ill in primary care. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(1):12-13.

21. Mitchell A, Pereira IE, Yadegarfar M, et al. Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness: comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):428-435.

22. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107.

23. Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):565-572.

24. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283(4):506-511.

25. Katon W, Unützer J, Wells K, et al. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):456-464.

26. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

27. Katon W, Russo J, Reed SD, et al. A randomized trial of collaborative depression care in obstetrics and gynecology clinics: socioeconomic disadvantage and treatment response. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):32-40.

28. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Request for Applications (RFA) No. SM- 09-011. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009.

29. Parks J. Behavioral health homes. In: Integrated care: working at the interface of primary care and behavioral health. Raney LE, ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:195.

30. Raney L. Integrated care: the evolving role of psychiatry in the era of health care reform. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(11):1076-1078.

1. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al, eds. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council; 2006.

3. Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1794-1796.

4. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trails of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):19-32.

5. Compton MT, Daumit GL, Druss BG. Cigarette smoking and overweight/obesity among individuals with serious mental illnesses: a preventive perspective. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):212-222.

6. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123-1131.

7. Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon W. Premature mortality from general medical illnesses among persons with bipolar disorder: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):147-156.

8. Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: a population-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(11):1133-1137.

9. Bobes J, Arango C, Aranda P, et al; CLAMORS Study Collaborative Group. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk in outpatients with schizoaffective disorder treated with antipsychotics; results from the CLAMORS study. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(4):267-274.

10. Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, et al. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database [Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(6):736]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):242-249.

11. Simon V, van Winkel R, De Hert M. Are weight gain and metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics dose dependent? A literature review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(7):1041-1050.

12. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

13. Mackin P, Bishop DR, Watkinson HM. A prospective study of monitoring practices for metabolic disease in antipsychotic-treated community psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:28.

14. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

15. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Hetrick SE, González-Blanch C, et al. Non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2008; 193(2):101-107.

16. Maayan L, Vakhrusheva J, Correll CU. Effectiveness of medication used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(7):1520-1530.

17. Newcomer JW, Weiden PJ, Buchanan RW. Switching antipsychotic medications to reduce adverse event burden in schizophrenia: establishing evidence-based practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):1108-1120.

18. Lord O, Malone D, Mitchell AJ. Receipt of preventive medical care and medical screening for patients with mental illness: a comparative analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):519-543.

19. Xiong GL, Iosif AM, Bermudes RA, et al. Preventive medical services use among community mental health patients with severe mental illness: the influence of gender and insurance coverage. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(5). doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00927gre.

20. Daub S. Turning toward treating the seriously mentally ill in primary care. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(1):12-13.

21. Mitchell A, Pereira IE, Yadegarfar M, et al. Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness: comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):428-435.

22. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107.

23. Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):565-572.

24. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283(4):506-511.

25. Katon W, Unützer J, Wells K, et al. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):456-464.

26. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

27. Katon W, Russo J, Reed SD, et al. A randomized trial of collaborative depression care in obstetrics and gynecology clinics: socioeconomic disadvantage and treatment response. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):32-40.

28. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Request for Applications (RFA) No. SM- 09-011. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009.

29. Parks J. Behavioral health homes. In: Integrated care: working at the interface of primary care and behavioral health. Raney LE, ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:195.

30. Raney L. Integrated care: the evolving role of psychiatry in the era of health care reform. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(11):1076-1078.