User login

When Rajeev Alexander, MD, lead hospitalist at Oregon Medical Group with PeaceHealth of Eugene, Ore., sought out an ophthalmologist, he didn’t go to provider Web sites or directory pages. He did what most healthcare patients do: He asked around.

Some of the nurses at work gave him suggestions. “‘This guy does a lot of LASIK and might push it.’ Or, ‘This guy has good relationships with patients.’ Or, ‘This is the guy I’d send my husband to,’” Dr. Alexander explains. “That helped.”

Were he to recommend a hospital, Dr. Alexander says he would base his selection on one major criterion: the collegiality of the facility’s doctors, pharmacists, and nurses. “If all the specialists in the hospital are talking to each other, and if they feel they can trust each other,” he says, “then I think you’re going to get good care.”

Dr. Alexander never mentions checking the performance of the physician or hospital he may use. It seems he’s not alone. In recent years, some famous cases have brought attention to how infrequently patients actually consult the available quality data when selecting a provider.

It’s unlikely, for example, that Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) researched provider collegiality as a quality measure when he chose a neurosurgeon at Duke University Medical Center to remove his malignant glioma. In 2004, when President Clinton needed his quadruple coronary bypass operation, he used an average-rated New York cardiologist. Why? Because, according to Dr. Jha, he didn’t compare quality reports.

Physicians are just as guilty of ignoring the information. Audience feedback at a hospital medicine continuing medical education course demonstrated to Robert M. Wachter, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine and chief of the medical service at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, that even members of UCSF’s Epidemiology and Biostatistics Department do not consult quality data before making medical decisions for themselves or a loved one. “Patients won’t start using quality data until we do it ourselves,” Dr. Wachter writes in his blog, Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com). “Best guess: three to five years.”

So how much progress have we really made in using publicly reported data to pick individual providers and hospitals? What should be measured in the future as it affects hospitalist practice? How can hospitalists influence the types of data collected?

Along the Continuum

The problem isn’t because people don’t know about the data. More than one-quarter (26%) of consumers who participated in a 2002 Harris poll said they are aware of hospital report cards, Dr. Wachter writes in his book Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America’s Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. However, only 3% considered changing their care based on those ratings, and only 1% actually made a change.1

Those who do consult the data seem to benefit—at least that is the case for users of New York state’s public reporting system for coronary artery bypass surgery. Dr. Jha and Arnold Epstein, MD, professor and chair of the department of Health Policy and Management at Harvard’s School of Public Health, found users who picked a top-performing hospital or surgeon had approximately half the mortality risk as did those who selected from the bottom quartile.2

But it is unusual for patients to choose a hospital based on publicly reported information alone, and Dr. Jha believes it’s largely due to mindset. “People are not used to approaching healthcare the way they would walk into a car dealership, for instance, ready to do battle,” he says.

Even if physicians and patients don’t consistently use the data, publishing it still has value. It helps physicians gauge their professional status, for example. “If someone is not looking good,” Dr. Jha says, “it is a huge impetus to improve, as long as you believe that what you are measuring is really associated with quality.”

Those who don’t believe it may have trouble, and sooner than they think. With 70 million beneficiaries, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sets the tone for healthcare quality in the U.S. In fact, Medicare beneficiaries comprise about one-third of those in a typical hospitalist’s practice. Since March 2008, the CMS Web site www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/ has reported hospital service data and soon will post cost comparisons.

“CMS is a payer we have to pay attention to (them),” says Patrick Torcson, MD, chair of SHM’s Performance and Standards Committee. “The CMS performance and quality agenda is specified at the statutory level as part of the Congressional record, and is very political. Therefore, that agenda right now is part scientific, part policy, and part methodology. There is a little something in it for everybody.”

Increasingly, quality measures are gradually, and insidiously, changing healthcare. For instance, Dr. Jha’s study found outcomes data did not greatly influence hospital market share, however, the surgeons with the highest publicly reported mortality rates were much more likely to retire after the release of each report card.2

Obstacles to Utilization

If these data can help us make educated healthcare decisions, why aren’t more people consulting them? To start, current measures aren’t sufficient, says Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, FACP, a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

“The number of measures and the strength of the evidence that current process measures are based on are still quite limited,” Dr. Lindenauer says. “Moreover, it is unclear how much the structural and process measures that have remained the focus of most public reporting contribute to patient outcomes.” It’s difficult to make statistically meaningful comparisons across hospitals or providers. Those efforts are “hampered by inadequate risk adjustment and tend to be underpowered to detect statistically significant differences.”

Another problem facing public reporting comparison initiatives is differences in healthcare utilization and spending across U.S. regions with similar levels of patient illness, says Stephanie Jackson, MD, a hospitalist with PeaceHealth and a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.3 The public cannot look at data it doesn’t have. For example, when Dr. Jackson asked researchers for data on coronary stroke rates, she was informed some physicians asked the data be held back because they didn’t like what it showed. “Why aren’t we demanding [that data]?” Dr. Jackson asks.

Essentially, then, quality data utilization is an evolving story. ”An ongoing debate exists between proponents of public reporting who believe that the best way to improve measures is to start using them,” Dr. Lindenauer says, “and those who advocate a more cautious approach and argue we should not rush to publicize data until we are clear about what the numbers signify and what to measure.”

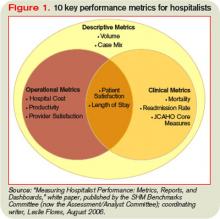

Some hospitals use more than 10 criteria as the benchmark for core measures, and 10 additional dimensions hospitalists use to assess their own internal performance (see Figure 1, pg. 41). Beyond that, metrics vary from hospital to hospital.

What Hospitalists Can Do

“It is very challenging to find doctors who are well-versed in public reporting of quality data,” says Latha Sivaprasad, MD, medical director, quality management and patient safety at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Jackson believes the more hospitalists know about quality data, the more they will want to use it. “Even though some hospitalists may be afraid to find out how they are doing,” she says, “in general, the better we get at measuring individual performance, the more hospitalists can examine their performance and how they can improve as individuals, as a group, and as an institution.”

Additionally, the era of value-based purchasing (pay for performance) is here—in the form of CMS’ Physician Quality Reporting Initiative. For the past year, physicians have reported on specific performance measures tied to a 1.5% bonus payout. Of the program’s 74 measures in 2007 and 119 measures in 2008, 11 have reporting specifications applicable to hospitalists.

“Three to 5% of the DRG [diagnosis-related group] reimbursement could be at stake for hospitals to achieve certain benchmarks,” Dr. Torcson says. “This will be a great opportunity for hospitalists to partner with their hospitals to develop synergy in achieving performance goals that are going to help maximize hospital quality initiatives and reimbursement.”

Hospitalists can get more involved with quality measures by:

- Joining the hospital quality improvement or patient safety teams;

- Creating toolkits to educate physicians in using quality data;

- Setting up unit-sponsored interdisciplinary teams on the floors to marry all lines of care; and

- Educating the public.

“The conventional wisdom is that the more procedures that an institution does, the better their performance,” Dr. Alexander says, giving as an example a specialized cardiac hospital. “But you really want your surgery in a hospital where they manage at least a moderately high number of procedures and have a very high” success rate treating complications.

Dr. Sivaprasad believes the public wants guidance on medical care quality, legal ramifications of care, physician-specific volume, and the significance of physician hospital privileges. “Maybe we should be more public about system outcomes changes that resulted from root-cause analyses performed,” she adds.

Whatever the level, hospitalists should get involved, Dr. Vidyarthi says. “Quality improvement is an area where you as hospitalists may be asked to engage—and you’re needed.” TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina and a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

1. Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America's Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. New York. Rugged Land. 2004.

2. Jha AK, Epstein AM. The predictive accuracy of the New York state coronary artery bypass surgery report-card system. Health Aff. 2006;25(3):844-855.

3. Sirovich BE, Gottlieb DJ, Welch HG, Fisher ES. Regional variations in healthcare intensity and physician perceptions of quality of care. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(9):641-649.

When Rajeev Alexander, MD, lead hospitalist at Oregon Medical Group with PeaceHealth of Eugene, Ore., sought out an ophthalmologist, he didn’t go to provider Web sites or directory pages. He did what most healthcare patients do: He asked around.

Some of the nurses at work gave him suggestions. “‘This guy does a lot of LASIK and might push it.’ Or, ‘This guy has good relationships with patients.’ Or, ‘This is the guy I’d send my husband to,’” Dr. Alexander explains. “That helped.”

Were he to recommend a hospital, Dr. Alexander says he would base his selection on one major criterion: the collegiality of the facility’s doctors, pharmacists, and nurses. “If all the specialists in the hospital are talking to each other, and if they feel they can trust each other,” he says, “then I think you’re going to get good care.”

Dr. Alexander never mentions checking the performance of the physician or hospital he may use. It seems he’s not alone. In recent years, some famous cases have brought attention to how infrequently patients actually consult the available quality data when selecting a provider.

It’s unlikely, for example, that Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) researched provider collegiality as a quality measure when he chose a neurosurgeon at Duke University Medical Center to remove his malignant glioma. In 2004, when President Clinton needed his quadruple coronary bypass operation, he used an average-rated New York cardiologist. Why? Because, according to Dr. Jha, he didn’t compare quality reports.

Physicians are just as guilty of ignoring the information. Audience feedback at a hospital medicine continuing medical education course demonstrated to Robert M. Wachter, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine and chief of the medical service at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, that even members of UCSF’s Epidemiology and Biostatistics Department do not consult quality data before making medical decisions for themselves or a loved one. “Patients won’t start using quality data until we do it ourselves,” Dr. Wachter writes in his blog, Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com). “Best guess: three to five years.”

So how much progress have we really made in using publicly reported data to pick individual providers and hospitals? What should be measured in the future as it affects hospitalist practice? How can hospitalists influence the types of data collected?

Along the Continuum

The problem isn’t because people don’t know about the data. More than one-quarter (26%) of consumers who participated in a 2002 Harris poll said they are aware of hospital report cards, Dr. Wachter writes in his book Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America’s Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. However, only 3% considered changing their care based on those ratings, and only 1% actually made a change.1

Those who do consult the data seem to benefit—at least that is the case for users of New York state’s public reporting system for coronary artery bypass surgery. Dr. Jha and Arnold Epstein, MD, professor and chair of the department of Health Policy and Management at Harvard’s School of Public Health, found users who picked a top-performing hospital or surgeon had approximately half the mortality risk as did those who selected from the bottom quartile.2

But it is unusual for patients to choose a hospital based on publicly reported information alone, and Dr. Jha believes it’s largely due to mindset. “People are not used to approaching healthcare the way they would walk into a car dealership, for instance, ready to do battle,” he says.

Even if physicians and patients don’t consistently use the data, publishing it still has value. It helps physicians gauge their professional status, for example. “If someone is not looking good,” Dr. Jha says, “it is a huge impetus to improve, as long as you believe that what you are measuring is really associated with quality.”

Those who don’t believe it may have trouble, and sooner than they think. With 70 million beneficiaries, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sets the tone for healthcare quality in the U.S. In fact, Medicare beneficiaries comprise about one-third of those in a typical hospitalist’s practice. Since March 2008, the CMS Web site www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/ has reported hospital service data and soon will post cost comparisons.

“CMS is a payer we have to pay attention to (them),” says Patrick Torcson, MD, chair of SHM’s Performance and Standards Committee. “The CMS performance and quality agenda is specified at the statutory level as part of the Congressional record, and is very political. Therefore, that agenda right now is part scientific, part policy, and part methodology. There is a little something in it for everybody.”

Increasingly, quality measures are gradually, and insidiously, changing healthcare. For instance, Dr. Jha’s study found outcomes data did not greatly influence hospital market share, however, the surgeons with the highest publicly reported mortality rates were much more likely to retire after the release of each report card.2

Obstacles to Utilization

If these data can help us make educated healthcare decisions, why aren’t more people consulting them? To start, current measures aren’t sufficient, says Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, FACP, a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

“The number of measures and the strength of the evidence that current process measures are based on are still quite limited,” Dr. Lindenauer says. “Moreover, it is unclear how much the structural and process measures that have remained the focus of most public reporting contribute to patient outcomes.” It’s difficult to make statistically meaningful comparisons across hospitals or providers. Those efforts are “hampered by inadequate risk adjustment and tend to be underpowered to detect statistically significant differences.”

Another problem facing public reporting comparison initiatives is differences in healthcare utilization and spending across U.S. regions with similar levels of patient illness, says Stephanie Jackson, MD, a hospitalist with PeaceHealth and a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.3 The public cannot look at data it doesn’t have. For example, when Dr. Jackson asked researchers for data on coronary stroke rates, she was informed some physicians asked the data be held back because they didn’t like what it showed. “Why aren’t we demanding [that data]?” Dr. Jackson asks.

Essentially, then, quality data utilization is an evolving story. ”An ongoing debate exists between proponents of public reporting who believe that the best way to improve measures is to start using them,” Dr. Lindenauer says, “and those who advocate a more cautious approach and argue we should not rush to publicize data until we are clear about what the numbers signify and what to measure.”

Some hospitals use more than 10 criteria as the benchmark for core measures, and 10 additional dimensions hospitalists use to assess their own internal performance (see Figure 1, pg. 41). Beyond that, metrics vary from hospital to hospital.

What Hospitalists Can Do

“It is very challenging to find doctors who are well-versed in public reporting of quality data,” says Latha Sivaprasad, MD, medical director, quality management and patient safety at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Jackson believes the more hospitalists know about quality data, the more they will want to use it. “Even though some hospitalists may be afraid to find out how they are doing,” she says, “in general, the better we get at measuring individual performance, the more hospitalists can examine their performance and how they can improve as individuals, as a group, and as an institution.”

Additionally, the era of value-based purchasing (pay for performance) is here—in the form of CMS’ Physician Quality Reporting Initiative. For the past year, physicians have reported on specific performance measures tied to a 1.5% bonus payout. Of the program’s 74 measures in 2007 and 119 measures in 2008, 11 have reporting specifications applicable to hospitalists.

“Three to 5% of the DRG [diagnosis-related group] reimbursement could be at stake for hospitals to achieve certain benchmarks,” Dr. Torcson says. “This will be a great opportunity for hospitalists to partner with their hospitals to develop synergy in achieving performance goals that are going to help maximize hospital quality initiatives and reimbursement.”

Hospitalists can get more involved with quality measures by:

- Joining the hospital quality improvement or patient safety teams;

- Creating toolkits to educate physicians in using quality data;

- Setting up unit-sponsored interdisciplinary teams on the floors to marry all lines of care; and

- Educating the public.

“The conventional wisdom is that the more procedures that an institution does, the better their performance,” Dr. Alexander says, giving as an example a specialized cardiac hospital. “But you really want your surgery in a hospital where they manage at least a moderately high number of procedures and have a very high” success rate treating complications.

Dr. Sivaprasad believes the public wants guidance on medical care quality, legal ramifications of care, physician-specific volume, and the significance of physician hospital privileges. “Maybe we should be more public about system outcomes changes that resulted from root-cause analyses performed,” she adds.

Whatever the level, hospitalists should get involved, Dr. Vidyarthi says. “Quality improvement is an area where you as hospitalists may be asked to engage—and you’re needed.” TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina and a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

1. Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America's Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. New York. Rugged Land. 2004.

2. Jha AK, Epstein AM. The predictive accuracy of the New York state coronary artery bypass surgery report-card system. Health Aff. 2006;25(3):844-855.

3. Sirovich BE, Gottlieb DJ, Welch HG, Fisher ES. Regional variations in healthcare intensity and physician perceptions of quality of care. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(9):641-649.

When Rajeev Alexander, MD, lead hospitalist at Oregon Medical Group with PeaceHealth of Eugene, Ore., sought out an ophthalmologist, he didn’t go to provider Web sites or directory pages. He did what most healthcare patients do: He asked around.

Some of the nurses at work gave him suggestions. “‘This guy does a lot of LASIK and might push it.’ Or, ‘This guy has good relationships with patients.’ Or, ‘This is the guy I’d send my husband to,’” Dr. Alexander explains. “That helped.”

Were he to recommend a hospital, Dr. Alexander says he would base his selection on one major criterion: the collegiality of the facility’s doctors, pharmacists, and nurses. “If all the specialists in the hospital are talking to each other, and if they feel they can trust each other,” he says, “then I think you’re going to get good care.”

Dr. Alexander never mentions checking the performance of the physician or hospital he may use. It seems he’s not alone. In recent years, some famous cases have brought attention to how infrequently patients actually consult the available quality data when selecting a provider.

It’s unlikely, for example, that Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) researched provider collegiality as a quality measure when he chose a neurosurgeon at Duke University Medical Center to remove his malignant glioma. In 2004, when President Clinton needed his quadruple coronary bypass operation, he used an average-rated New York cardiologist. Why? Because, according to Dr. Jha, he didn’t compare quality reports.

Physicians are just as guilty of ignoring the information. Audience feedback at a hospital medicine continuing medical education course demonstrated to Robert M. Wachter, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine and chief of the medical service at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, that even members of UCSF’s Epidemiology and Biostatistics Department do not consult quality data before making medical decisions for themselves or a loved one. “Patients won’t start using quality data until we do it ourselves,” Dr. Wachter writes in his blog, Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com). “Best guess: three to five years.”

So how much progress have we really made in using publicly reported data to pick individual providers and hospitals? What should be measured in the future as it affects hospitalist practice? How can hospitalists influence the types of data collected?

Along the Continuum

The problem isn’t because people don’t know about the data. More than one-quarter (26%) of consumers who participated in a 2002 Harris poll said they are aware of hospital report cards, Dr. Wachter writes in his book Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America’s Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. However, only 3% considered changing their care based on those ratings, and only 1% actually made a change.1

Those who do consult the data seem to benefit—at least that is the case for users of New York state’s public reporting system for coronary artery bypass surgery. Dr. Jha and Arnold Epstein, MD, professor and chair of the department of Health Policy and Management at Harvard’s School of Public Health, found users who picked a top-performing hospital or surgeon had approximately half the mortality risk as did those who selected from the bottom quartile.2

But it is unusual for patients to choose a hospital based on publicly reported information alone, and Dr. Jha believes it’s largely due to mindset. “People are not used to approaching healthcare the way they would walk into a car dealership, for instance, ready to do battle,” he says.

Even if physicians and patients don’t consistently use the data, publishing it still has value. It helps physicians gauge their professional status, for example. “If someone is not looking good,” Dr. Jha says, “it is a huge impetus to improve, as long as you believe that what you are measuring is really associated with quality.”

Those who don’t believe it may have trouble, and sooner than they think. With 70 million beneficiaries, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sets the tone for healthcare quality in the U.S. In fact, Medicare beneficiaries comprise about one-third of those in a typical hospitalist’s practice. Since March 2008, the CMS Web site www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/ has reported hospital service data and soon will post cost comparisons.

“CMS is a payer we have to pay attention to (them),” says Patrick Torcson, MD, chair of SHM’s Performance and Standards Committee. “The CMS performance and quality agenda is specified at the statutory level as part of the Congressional record, and is very political. Therefore, that agenda right now is part scientific, part policy, and part methodology. There is a little something in it for everybody.”

Increasingly, quality measures are gradually, and insidiously, changing healthcare. For instance, Dr. Jha’s study found outcomes data did not greatly influence hospital market share, however, the surgeons with the highest publicly reported mortality rates were much more likely to retire after the release of each report card.2

Obstacles to Utilization

If these data can help us make educated healthcare decisions, why aren’t more people consulting them? To start, current measures aren’t sufficient, says Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, FACP, a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

“The number of measures and the strength of the evidence that current process measures are based on are still quite limited,” Dr. Lindenauer says. “Moreover, it is unclear how much the structural and process measures that have remained the focus of most public reporting contribute to patient outcomes.” It’s difficult to make statistically meaningful comparisons across hospitals or providers. Those efforts are “hampered by inadequate risk adjustment and tend to be underpowered to detect statistically significant differences.”

Another problem facing public reporting comparison initiatives is differences in healthcare utilization and spending across U.S. regions with similar levels of patient illness, says Stephanie Jackson, MD, a hospitalist with PeaceHealth and a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.3 The public cannot look at data it doesn’t have. For example, when Dr. Jackson asked researchers for data on coronary stroke rates, she was informed some physicians asked the data be held back because they didn’t like what it showed. “Why aren’t we demanding [that data]?” Dr. Jackson asks.

Essentially, then, quality data utilization is an evolving story. ”An ongoing debate exists between proponents of public reporting who believe that the best way to improve measures is to start using them,” Dr. Lindenauer says, “and those who advocate a more cautious approach and argue we should not rush to publicize data until we are clear about what the numbers signify and what to measure.”

Some hospitals use more than 10 criteria as the benchmark for core measures, and 10 additional dimensions hospitalists use to assess their own internal performance (see Figure 1, pg. 41). Beyond that, metrics vary from hospital to hospital.

What Hospitalists Can Do

“It is very challenging to find doctors who are well-versed in public reporting of quality data,” says Latha Sivaprasad, MD, medical director, quality management and patient safety at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Jackson believes the more hospitalists know about quality data, the more they will want to use it. “Even though some hospitalists may be afraid to find out how they are doing,” she says, “in general, the better we get at measuring individual performance, the more hospitalists can examine their performance and how they can improve as individuals, as a group, and as an institution.”

Additionally, the era of value-based purchasing (pay for performance) is here—in the form of CMS’ Physician Quality Reporting Initiative. For the past year, physicians have reported on specific performance measures tied to a 1.5% bonus payout. Of the program’s 74 measures in 2007 and 119 measures in 2008, 11 have reporting specifications applicable to hospitalists.

“Three to 5% of the DRG [diagnosis-related group] reimbursement could be at stake for hospitals to achieve certain benchmarks,” Dr. Torcson says. “This will be a great opportunity for hospitalists to partner with their hospitals to develop synergy in achieving performance goals that are going to help maximize hospital quality initiatives and reimbursement.”

Hospitalists can get more involved with quality measures by:

- Joining the hospital quality improvement or patient safety teams;

- Creating toolkits to educate physicians in using quality data;

- Setting up unit-sponsored interdisciplinary teams on the floors to marry all lines of care; and

- Educating the public.

“The conventional wisdom is that the more procedures that an institution does, the better their performance,” Dr. Alexander says, giving as an example a specialized cardiac hospital. “But you really want your surgery in a hospital where they manage at least a moderately high number of procedures and have a very high” success rate treating complications.

Dr. Sivaprasad believes the public wants guidance on medical care quality, legal ramifications of care, physician-specific volume, and the significance of physician hospital privileges. “Maybe we should be more public about system outcomes changes that resulted from root-cause analyses performed,” she adds.

Whatever the level, hospitalists should get involved, Dr. Vidyarthi says. “Quality improvement is an area where you as hospitalists may be asked to engage—and you’re needed.” TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina and a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

1. Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America's Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. New York. Rugged Land. 2004.

2. Jha AK, Epstein AM. The predictive accuracy of the New York state coronary artery bypass surgery report-card system. Health Aff. 2006;25(3):844-855.

3. Sirovich BE, Gottlieb DJ, Welch HG, Fisher ES. Regional variations in healthcare intensity and physician perceptions of quality of care. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(9):641-649.